Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Indigenous Housing Initiatives the Fixing Houses for Better Health program

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of FaHCSIA's management of the Fixing Houses for Better Health program since 2005.

The audit reviewed the two elements of the program for which FaHCSIA is responsible: management of the service delivery arrangements and overall performance monitoring and reporting. Following the development of the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing, which introduced new approaches to the delivery of Indigenous programs, FaHCSIA made changes to FHBH for the 2009–11 phase. The audit has focused on both the 2005–09 and the 2009–11 phases. This provided coverage of the program's normal operations as well enabling the audit to consider the modifications made to the program for the

2009–11 phase.

Against this background, the audit considered whether:

- program management arrangements had been established that were suitable for the size, nature and objectives of the FHBH program;

- service delivery arrangements were designed to support the achievement of the program's objectives and FaHCSIA's management of the program; and

- FaHCSIA used robust systems to monitor achievement of the program objectives.

The ANAO also considered whether there was any experience from the department's management of FHBH that could be broadly applied to FaHCSIA's management of the National Partnership Agreement.

Summary

Indigenous housing and health

1. The Fixing Houses for Better Health (FHBH) program aims to contribute to improved health in Indigenous communities. It is a small program that is targeted at the individual household level in selected Indigenous communities (or groups of communities). To promote a healthier living environment, the program assesses and makes repairs to houses following a standardised methodology that gives priority to making a house safe to live in, and then to improving water supplies, sanitation equipment, and food preparation areas. By making these improvements to houses in a community, the program is expected to contribute to improved health outcomes for that community.

2. Providing adequate housing for Indigenous Australians in remote communities has been a major challenge for successive governments at both the federal and state levels. Remote Indigenous communities continue to be affected by high levels of overcrowding, homelessness, poor housing conditions and severe housing shortages.[1] These factors combine to create a living environment that can adversely affect health.

3. The importance of environmental health to public health outcomes is well established.[2] The World Health Organisation notes that an environmental health approach involves assessing and controlling the “environmental factors that can potentially affect health. It is targeted towards preventing disease and creating healthy supportive environments.”[3] With regard to applying such an approach to Indigenous health, a key development was the preparation in 1987 of a report for the South Australian Government on environmental and public health. This report developed the concept of the Healthy Living Practices which went on to become a feature of policy approaches to Indigenous housing.

4. Since the late 1990s, Indigenous housing policy has generally been consistent in recognising the linkages between a healthy living environment and a person's health, with flow-on effects into educational achievement, community safety and economic participation. In 1997, Commonwealth, State and Territory Housing Ministers jointly agreed a new policy direction for Indigenous housing. This policy emphasised the need for housing to be safe, healthy and sustainable, and to ultimately result in improved environmental health outcomes for Indigenous people. The National Framework for the Design, Construction and Maintenance of Indigenous Housing (the national framework) was also developed as a result of this policy.

5. The four key principles of the national framework were that:

- houses will be designed, constructed and maintained for safety;

- houses will be designed, constructed and maintained to support Healthy Living Practices;

- quality control measures will be adopted in the design and construction of houses; and

- houses will be designed and constructed for long term function and ease and economy of maintenance.

6. Improving Indigenous housing continues to be a major policy and implementation priority for governments. Housing programs have been given a central role in the current efforts to reduce Indigenous disadvantage through the `Closing the Gap' strategy. Significant financial commitments to improving the supply and quality of housing stock in Indigenous communities have been made by Commonwealth and state/territory governments under the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing (the National Partnership Agreement). The National Partnership Agreement, which commenced in January 2009, subsumes previous Commonwealth and jurisdictional arrangements related to the delivery of Indigenous housing programs. Over 10 years, $5.5 billion will be invested in housing to:

- significantly reduce severe overcrowding in remote Indigenous communities;

- increase the supply of new houses and improve the condition of existing houses in remote Indigenous communities; and

- ensure that rental houses are well maintained and managed in remote Indigenous communities.

7. In continuing the policy focus on the development of healthier living conditions, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) has identified that the maintenance and repair of existing housing under the National Partnership Agreement should ‘contribute to improving environmental health'.[4] In this respect, key elements of the National Partnership Agreement have adopted the use of the Healthy Living Practices, which were also used by the FHBH program.

The Fixing Houses for Better Health program

8. FHBH commenced in 1999. It was initially administered by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) until the program was transferred in 2001 to the then Department of Family and Community Services (FaCS). It is currently administered by the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) where it forms part of Program 7.2: Indigenous Housing and Infrastructure.

9. The development in 1999 of the national framework emphasised the importance of the Healthy Living Practices. These are nine environmental health elements that are relevant to improving health in Indigenous communities. In order of priority these are:

- the ability to wash people, particularly children;

- the ability to wash clothes and bedding;

- removing waste safely from the house and immediate living environment;

- improving nutrition and the ability to store, prepare and cook food;

- reducing the negative effects of crowding;

- reducing the negative contact between people and animals, insects and vermin;

- reducing dust;

- controlling the temperature of the living environment; and

- reducing trauma, or minor injury, by removing hazards.

10. To improve the ability of a house to support the Healthy Living Practices, attention needs to be given to improving the physical equipment necessary for healthy, hygienic living. Known as health hardware, this equipment generally relates to the water supply, sanitation and food preparation areas of a house. The FHBH program was established as one of the key mechanisms to contribute to safe and healthy housing in Indigenous communities by implementing a housing repair and maintenance system based on the application of the Healthy Living Practices. FHBH was supported by the publication of the National Indigenous Housing Guide (the housing guide), a resource to assist in the design, construction and maintenance of Indigenous housing. The housing guide, like FHBH, emphasises the importance of health hardware and the Healthy Living Practices.

11. There have been four phases of FHBH since 1999, with the current phase scheduled to end in June 2011. The program has been delivered across Australia except in Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory. Since the inception of FHBH, the Australian Government has directly invested $40 million in the FHBH program, as well as other indirect contributions through the use of labour from the Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP) program. Financial contributions are also made by state and Northern Territory governments. No decision has been made in relation to funding FHBH beyond 2011.

12. The FHBH program is delivered through a contract between FaHCSIA and a national service provider (the Service Provider). Until 2009, the contract arrangement was supported by funding agreements between FaHCSIA and relevant state and Northern Territory government agencies to deliver FHBH projects in communities. In some cases, FaHCSIA also entered into funding agreements with Indigenous Community Housing Organisations for project delivery services. Since 2009, all project delivery has been managed through a single contract with the national Service Provider, with state and territory governments being supported to integrate the principles of the FHBH approach into their own jurisdictions.

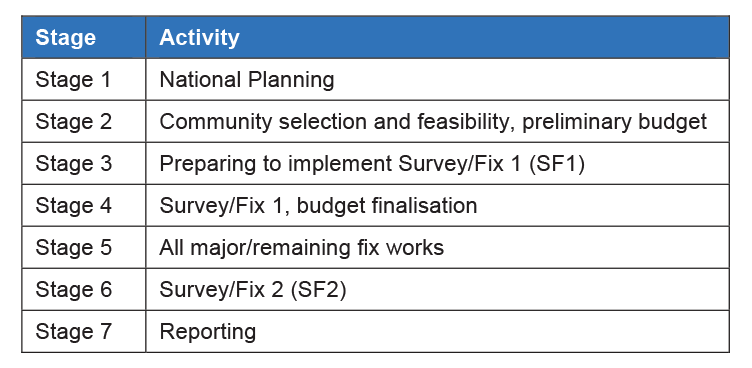

13. The delivery of an FHBH project in a community involves seven stages, outlined in Table 1 below.

Table 1 Delivery stages

14. The National Planning stage involves consultation between FaHCSIA and the Service Provider to establish resourcing and focus areas for the year and to discuss emerging priorities. This stage is important as it ensures consistent project processes are established across jurisdictions. Communities are selected by FaHCSIA in consultation with the relevant government agency in the jurisdiction.

15. After communities are selected to receive an FHBH project, a planning process is undertaken to survey and make necessary repairs to all houses, where possible, within a community. Project teams, which include tradespeople and community members who have been trained in the process, first survey each house and make minor repairs as they go. This process is called survey/fix 1 or SF1. In the following six months, major repairs identified in the survey are completed. Once this work has been done, a second ‘survey and fix' (SF2) is conducted to complete any outstanding minor maintenance issues. The second survey also measures the level of improvement in health hardware achieved between the first and second surveys. This provides a ‘before and after' approach to measuring the effects of the program's activities in relation to individual houses. The reporting stage involves the Service Provider reviewing and analysing the data from all stages, before providing individual community reports and an amalgamated final report.

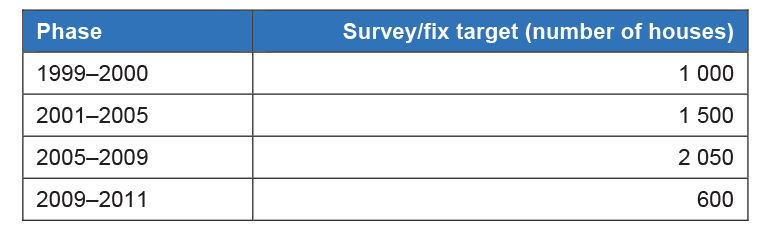

16. In agreeing to provide funding for FHBH, successive governments have set targets for the numbers of houses to be surveyed and fixed. These are presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Housing targets per phase

In the 2005–09 phase of the program, some 2 089 houses across 34 communities had repairs undertaken by FHBH, exceeding the target of 2 050 houses. Appendix 2 provides a list of these communities.

Objective and scope

17. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of FaHCSIA's management of the Fixing Houses for Better Health program since 2005.

18. The audit reviewed the two elements of the program for which FaHCSIA is responsible: management of the service delivery arrangements and overall performance monitoring and reporting. Following the development of the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing, which introduced new approaches to the delivery of Indigenous programs, FaHCSIA made changes to FHBH for the 2009–11 phase. The audit has focused on both the 2005–09 and the 2009–11 phases. This provided coverage of the program's normal operations as well enabling the audit to consider the modifications made to the program for the 2009–11 phase.

19. Against this background, the audit considered whether:

- program management arrangements had been established that were suitable for the size, nature and objectives of the FHBH program;

- service delivery arrangements were designed to support the achievement of the program's objectives and FaHCSIA's management of the program; and

- FaHCSIA used robust systems to monitor achievement of the program objectives.

20. The ANAO also considered whether there was any experience from the department's management of FHBH that could be broadly applied to FaHCSIA's management of the National Partnership Agreement.

Overall conclusion

21. Delivery of Indigenous housing programs is challenging. Housing needs tend to vary from community to community and also between houses within communities. Solutions must often be tailored to specific communities to be effective. In remote areas, construction and maintenance services face additional hurdles created by distance and limitations in local resources and capacity. The FHBH program sought to address these challenges by deliberately involving community members in repair and maintenance projects, and by focusing efforts at a household level. At the same time, the program was designed to allow a level of consistency to be achieved across communities through the use of a standardised assessment and work prioritisation model.

22. On a modest resource base, the FHBH program was able to make key health related improvements, as planned, to over 2 000 houses in 34 communities between July 2005 and June 2009. These communities were geographically dispersed in mainly remote areas of five states and the Northern Territory. Through its targeted activities, the program has been able to improve the extent to which health hardware in houses has functioned.

23. The program sought to improve health hardware in as many community houses as possible. This level of coverage is important as the underlying public health rationale is that ‘... to achieve health outcomes, most houses in a community must have health hardware that functions most of the time.' Performance information indicated that, while the extent of improvement in individual houses was subject to some variation, as was the extent of improvement in individual Healthy Living Practices, there was an overall improvement across the program in the way houses performed in their ability to support the Healthy Living Practices.

24. FaHCSIA's program management arrangements did not cater for the collection of data that provided a means of linking the improvements made to houses in communities under this program with changes in health indicators in those same communities. Because of this gap, it is not possible to draw relationships between the implementation of the FHBH program's activities and its overall purpose of improving Indigenous health.

25. While the overall linkage between environmental health and public health is well established, it cannot necessarily be assumed that all approaches and programs are equally efficient and effective in making contributions to improved health. Some specific assessment of FHBH's relative effectiveness would have been useful for FaHCSIA to increase its knowledge of how different programs and interventions can contribute to the desired outcomes. This will be an increasingly important matter for FaHCSIA given the significantly increased funding being provided for Indigenous housing under the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing and the contribution that it is expected by COAG to make to improve environmental health in communities.

26. The ANAO has identified several areas of improvement that could be made in the current phase of the program that would benefit the future management of the program. Primarily, these focus on improving the approach to monitoring the program and evaluating its contribution to environmental health. Building the department's capacity to assess improvements to Indigenous health arising from its housing activities will also support its management of the National Partnership Agreement.

Key findings by chapter

Program management arrangements (Chapter 2)

27. There are inherent tensions in developing an appropriate management framework, commensurate with the size of a program, that can assist agencies to target resources to have maximum impact and to complement other programs. The FHBH program has a strongly defined methodology and approach, which is provided by the Service Provider. FaHCSIA has developed relatively elementary program management arrangements for FHBH. These have focused on the development and management of a contract with the Service Provider and funding agreements with, mainly, state and territory government agencies. As the Service Provider's methodology has provided a detailed approach to the program's strategy and implementation, there has been little incentive for FaHCSIA to develop detailed strategies to guide implementation.

28. This has not necessarily impaired the performance of the program in meeting the specific output targets set by government for house repairs. There were, however, inconsistencies in the way program objectives have been publicly reported and described in different funding agreements, and weaknesses in the ability of FaHCSIA to consistently monitor and report on program performance. Overall, these point to a situation where the program has not been tightly linked to broader policy goals; further, there are opportunities for FaHCSIA to consider ways of consolidating the management of small programs to provide a more strategic outlook.

Service delivery mechanisms (Chapter 3)

29. Well designed and effectively managed contracts are central to effective program management and the delivery of expected outcomes. The design of the 2005–09 and 2009–11 contracts with the Service Provider is based upon, and closely aligns with, the Service Provider's methodology. While this has the advantage of providing clarity about the targets, outputs and activities the Service Provider is obliged to deliver, it has served to limit FaHCSIA's active management of the contract. Payments under the contracts generally were not clearly linked to the achievement of specific deliverables, and the structure of the contract worked against the timely provision of relevant analytical information. To better position itself to make informed programming decisions, FaHCSIA could improve the management and monitoring of the contracts and agreements developed for the FHBH program.

Program performance measurement (Chapter 4)

30. Performance measurement arrangements for the program have mainly been designed to report on changes in the condition and functioning of houses. The inclusion in the program's design of the “before and after” approach of assessing houses at two separate stages enabled information to be collected in relation to the improvements achieved. This data was also useful in providing a broader understanding of the condition of housing stock in the communities where FHBH had operated. The performance data collected at this level was effectively used in the preparation and revision of the housing guide.

31. The design of the program's performance framework, however, did not allow for ongoing assessment of performance in the area of integrating the FHBH approach into state and territory systems, as limited data was collected. The performance framework also did not include the capacity to collect and assess performance information in relation to the overall purpose of the program, which was to contribute to better health in Indigenous communities.

32. Without this performance information, it is difficult for FaHCSIA to advise government on the effectiveness and efficiency of the approach taken through FHBH and to compare this to possible alternatives. For small programs, there are constraints on the level of comprehensiveness that can be included in the performance framework. Nevertheless, there are opportunities for FaHCSIA to undertake more work in this area, with a view to strengthening its understanding of the linkages between specific ways of supporting the Healthy Living Practices and improved health.

Considerations for the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing (Chapter 5)

33. The National Partnership Agreement is designed to ultimately lead to improvements in Indigenous health by providing healthier living environments. While it operates with a significantly larger budget than FHBH, and is a separate program with a different methodology, the National Partnership Agreement shares with FHBH an approach based on seeking improvements through a focus on supporting the Healthy Living Practices.

34. There is value in FaHCSIA considering its experience of managing the FHBH program, in particular, the challenges of assessing linkages between program activities and improved health, to inform the development of effective monitoring and evaluation arrangements for the National Partnership Agreement.

Summary of agency response

35. Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the ANAO's Section 19 Report: Indigenous Housing Initiatives: the Fixing Houses for Better Health (FHBH) program. A summary of the Department's response is outlined below.

36. FaHCSIA agrees with the overall findings and recommendations of the ANAO's Section 19 report but notes that observations relating to the National Partnership on Remote Indigenous Housing require further consideration.

37. The other area FaHCSIA wishes to remark on is the ANAO's commentary relating to the lack of health indicators within the program which forms the basis for ANAO's Recommendation 2. FaHCSIA wishes to highlight the fact that FHBH is a relatively small scale repair and maintenance program that does not have the scope to develop health indicators and measure improvements to community health over the long term. FHBH does, however, improve and measure the functionality of the critical house hardware, thereby increasing a community's ability to adhere to the nine healthy living practices.

ANAO comments on agency response

38. The ANAO appreciates FaHCSIA's agreement with the overall findings and recommendations of the report and the department's comments concerning the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing. The ANAO also acknowledges that there may be constraints in developing cost-effective ways of measuring the impact of small programs. Nevertheless, given the explicit aim of the program to contribute to better health, and the length of time that the program has operated, it is reasonable to expect that consideration would have been given to developing ways to provide the Australian Government, the Parliament and other stakeholders some assessment of the FHBH program's contributions to improved health in Indigenous communities.

39. This recommendation has also been made with a view to FaHCSIA taking the opportunity of the remaining FHBH program activities to help position the department to be able to make informed assessments of the contribution to improved environmental health by the housing investments made under the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing.

Footnotes

[1] Australian Government 2009, Closing the Gap on Indigenous Disadvantage: The Challenge for Australia, p. 21.

[2] National Indigenous Housing Guide, third edition 2007, p. 11.

[3] <http://www.who.int/topics/environmental_health/en/> [accessed 10 August 2010].

[4] National Indigenous Reform Agreement p. A 37.