Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Indigenous Home Ownership Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Indigenous Business Australia’s management and implementation of the Indigenous Home Ownership Program.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Indigenous Home Ownership Program (IHOP) has provided housing loans to Indigenous Australians to increase the level of home ownership since 1975.1 The objective of the program is to facilitate Indigenous Australians into home ownership by addressing barriers such as lower incomes and savings, credit impairment and limited experience with loan repayments. The program is focused on first home buyers who have difficulty obtaining home loan finance from other financial institutions.2 In remote areas, where there is appropriate tenure for home ownership3, the program also seeks to help Indigenous Australians overcome additional barriers to home ownership.4 The overall success of the program is assessed in terms of increasing the percentage of Indigenous Australians who are home owners.5

2. Indigenous Business Australia (IBA) has been responsible for administering the program since 2005. IBA offers basic home loans for purchasing, constructing, renovating and refinancing. The main differences between the loans offered by IBA and mainstream finance loans are a lower deposit requirement, a longer standard loan term and a standard introductory interest rate of 4.5 per cent.6 IBA also offers an interest rate of 3 per cent and a lower deposit threshold for eligible low income earners.7 IBA assess loan applications against a set of loan eligibility criteria through a two-stage application process. The value of loans in the IBA portfolio as at June 2015 was $928.3 million.

Audit objectives and criteria

3. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of IBA’s management and implementation of the IHOP. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- IBA has management arrangements that support equitable access to IHOP and the achievement of the long-term outcomes of IHOP, including whether clear objectives have been established for the program, program activities are consistent with program objectives and directed towards target customers;

- service delivery is responsive to the needs of target customers and loan assessments are undertaken in line with IHOP policy and procedure, supporting the achievement of program outcomes; and

- performance measurement and reporting mechanisms support accurate assessments of progress towards program outcomes, and achieved performance is in line with the Australian Government’s expectations.

Overall conclusion

4. Under IBA’s management, from June 2005 to June 2015, IHOP has delivered 4937 loans to Indigenous Australians at an average annual program cost of $37.8 million.8 The home loans approved through the program have resulted in a maximum contribution of 11.6 per cent to the increase in the national home ownership participation rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from 2006 to 2011.9 However, it is not possible to assess how many of these participants would otherwise have been able to access mainstream finance.

5. The ANAO identified that IBA’s management of the program has been inefficient and lending does not fully align with the program objective for which IBA is funded. IBA has met its target for first home buyers, which is a particular focus of the program. However, IBA lending is not directed at low income earners who form an important segment of the program’s target customers. Also, there is not a strong focus on targeting areas where there is high need for home ownership assistance. Instead, IBA has increasingly approved loans to medium and higher income earners and lower risk customers. As market conditions have changed, the loan products offered by IBA have provided comparatively less benefit to Indigenous customers than products offered by mainstream lenders. IBA also needs to improve its business practices to be more efficient in delivering the program. This includes making the application process more accessible and streamlining how IBA assesses loan applications to avoid duplication and reduce unnecessary burden for applicants.

6. The home loan program was established and designed to meet the barriers to home ownership experienced by Indigenous Australians in 1975. Since this time, the loan product and delivery mechanisms of the program have remained largely unchanged. After 40 years of operation, it is timely for the Australian Government to assess whether a government-funded end-to-end loan program remains the most effective mechanism for supporting Indigenous Australians into home ownership.

Key findings

7. IBA has management arrangements in place to support equitable access to the program, however IBA does not generally verify that its customers cannot access mainstream finance which is a key loan eligibility criteria and threshold for entry to the program. The current lending activity of the program is not aligned with one of the program’s target groups, low income earners. There has also been an increase in the proportion of higher income households receiving loans from IBA. In 2011–12, 52 per cent of loans were to customers earning over 100 per cent of the IBA Income Amount.10 This percentage increased to 59 per cent in 2012–13 and 57 per cent in 2013–14. However, IBA loans are primarily directed towards first home owners which are also a clear target group for the program.

8. Service delivery through the program is not responsive to customer needs as the expression of interest and loan application process is largely paper-based, time consuming and duplicative. The majority of customers interviewed by ANAO reported difficulties with the process and in particular with aspects of the paperwork required. IBA customers are not able to apply for a loan or access their account information online and after-loan care is generally limited unless a customer falls into arrears. IBA has identified key actions for improving service delivery, by developing and implementing online services, but has not progressed these actions. In addition to the impact on customers, IBA has missed the potential cost savings of streamlining administrative processes and moving to online service delivery.

9. IBA mostly undertakes loan assessments in line with program policy and there is flexibility within assessments to provide for the different circumstances of applicants. In a sample of 100 IBA customer files, where an applicant had submitted an expression of interest between July 2011 and June 2014, the ANAO identified some inconsistent considerations in lending decisions and documentation to support decisions. IBA has put some processes in place to provide greater assurance that lending decisions are accurate and consistent. However, these assurance processes are relatively new.

10. In 2014–15, IBA met two out of three key performance indicators for the program but did not meet either of the program’s key deliverables. Further, the number of loans approved by IBA has declined over the last three years. Prior to this, the program mostly met the program’s targets for lending levels over the last five years in line with government expectations. IBA reporting overstates the number of loans that have led to new home ownership outcomes against the program’s main key deliverable and the income figures reported do not reflect total customer income. For the financial years 2009–10 to 2013–14, out of the 2552 home loans reported by IBA the ANAO identified 80 instances or 3.1 per cent of expended funds that did not directly relate to a new home outcome. Also, when total customer income is considered, over 50 per cent of IBA loans are to households earning over the IBA Income Amount.

11. IBA does not monitor the quality of service delivery or collect information to assess whether the program is meeting the needs of customers. The ANAO also identified some data quality issues and limitations in IBA’s performance measurement and reporting mechanisms which are likely to be reflected in both internal and external reporting.

12. From 2012–13 to 2013–14, IBA received 116 loan applications from Indigenous Australians living in remote communities designated by IBA as Emerging Markets.11 Of the applications received, IBA approved 14 loans and 68 grants to support home ownership, with a total value of $1.37 million. No specific targets were set for home ownership outcomes in Emerging Markets and accordingly it is difficult to determine if this progress is in line with expectations.

13. In recent years, the lending environment has changed, affecting IBA’s customer base. These changes include the withdrawal of first home owner support initiatives, increased property prices in some areas and lower mainstream interest rates. IBA considers that these changes have affected the ability of lower income earners in particular to access IBA loans however IBA has not provided evidence of analysis to support this position. In light of these conditions, IBA should evaluate whether it is able to continue to demonstrate to government value for money through the homes program in its current format and whether its current product suite is suited to its target customers and the barriers faced in achieving home ownership.

14. The ANAO has made three recommendations directed at IBA, aimed at aligning program activities with program outcomes, making service delivery more responsive to the needs of IBA customers and increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of IBA’s business practices, and improving program performance measurement and reporting. The ANAO has also recommended that the Australian Government assess the delivery mechanism for achieving Indigenous home ownership outcomes.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.15 |

In order to align program activities with the program outcomes, the ANAO recommends that IBA either:

Indigenous Business Australia’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 2.37 |

In order to support continued progress in closing the gap in home ownership outcomes, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Government assess whether a government-run loan program is the most efficient mechanism to support Indigenous home ownership outcomes. Indigenous Business Australia’s response: Noted. |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 3.31 |

In order to make service delivery more responsive to the needs of target customers and increase the efficiency and effectiveness of business practices, ANAO recommends that IBA:

Indigenous Business Australia’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 4 Paragraph 4.28 |

In order to improve performance reporting, the ANAO recommends that IBA:

Indigenous Business Australia’s response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity response

15. Indigenous Business Australia’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while its full response is at Appendix 1.

IBA welcomes the ANAO’s audit report recommendations, which are strategically aligned with IBA’s future plans for the Indigenous Home Ownership Program. To date the program has made a significant contribution to addressing Indigenous economic disadvantage. Over the course of 40 years IBA has assisted over 16,000 households to enter home ownership, enabling customers to accumulate more than $2 billion in personal wealth, while successfully growing its home loan portfolio by an average of 6% per annum to its current level of $943 million.

The ANAO’s recommendations support IBA’s view that changes are required to meet the multiple challenges the program faces of constrained capital, rising house prices and growing demand. These changes will enable IBA to make greater inroads into closing the gap between Indigenous and non‐Indigenous home ownership rates. Through its current work with the Government, IBA is well‐placed to develop and implement changes that will improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the program, which will deliver stronger outcomes for Indigenous Australians.

1. Background

1.1 The Indigenous Home Ownership Program (IHOP) has provided housing loans to Indigenous Australians to increase the level of home ownership since 1975.12 The objective of the program is to facilitate Indigenous Australians into home ownership by addressing barriers such as lower incomes and savings, credit impairment and limited experience with loan repayments. The program is focused on first home buyers who have difficulty obtaining home loan finance from other financial institutions.13 In remote areas, where there is appropriate tenure for home ownership14, the program also seeks to help Indigenous Australians overcome additional barriers to home ownership.15 The overall success of the program is assessed in terms of increasing the percentage of Indigenous Australians who are home owners.16

1.2 Indigenous Business Australia (IBA) has been responsible for administering the program since 2005. IBA offers basic home loans for purchasing, constructing, renovating and refinancing. The main differences between the loans offered by IBA and mainstream finance loans are a lower deposit requirement, a longer standard loan term and a standard introductory interest rate of 4.5 per cent.17 IBA also offers an interest rate of 3 per cent and a lower deposit threshold for eligible low income earners.18

1.3 The total amount of funds allocated for lending through IHOP in 2014–15 was $149 million. This amount is a combination of the revenue IBA receives from existing loans, new appropriations and an increase in funding resulting from the consolidation of the Home Ownership on Indigenous Land program into IHOP. As at June 2015, IBA had approved 4937 loans under IHOP with average annual program expenses of $37.8 million.19 In addition to the administrative costs of running the program, a large component of the program expenses each year is the valuation decrement which represents a loss on IBA investments.20 The value of loans in the IBA portfolio was $928.3 million. After accounting for recognising assets at their fair value this was $636.4 million.

1.4 As the demand for its home loans has historically been in excess of available funding, IBA has implemented a two-stage application process. The first stage of the application process involves an applicant registering an interest in a loan and meeting a minimum set of the loan eligibility criteria. These criteria include: having at least one applicant of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander descent; not being able to source the required home loan amount or part thereof from a mainstream lender; being able to meet minimum deposit requirements; and having the capacity to meet housing loan repayments. If eligible, the applicant is placed on an expression of interest register.

1.5 The second stage involves IBA inviting the applicant to apply for a loan once funding becomes available. Once invited, applicants submit a formal loan application to be assessed against the loan eligibility criteria. The amount that IBA will lend an applicant will depend on a number of factors such as the applicant’s income and capacity to meet loan repayments. However, the specific terms and conditions of each loan are not determined until IBA undertakes a full assessment of an applicant’s formal loan application against all loan eligibility criteria.

1.6 Applicants who earn a higher income may be required to obtain a split loan by IBA. Split loan arrangements are where customers obtain part of their funds from another lender. If an applicant’s combined gross annual income21 is between 115 and 225 per cent of the IBA Income Amount, IBA requires the applicant to obtain 40 to 80 per cent of loan funds from a mainstream commercial lender.22 IBA considers it is able to support more applicants by providing split loans, and in some cases reduce the waiting time for an IBA loan. In 2014–15, 105 loans (20 per cent of the total number of loans approved) were funded under a split loan arrangement. In March 2015, IBA introduced temporary changes to lending parameters so that customers earning up to 165 per cent of the IBA Income Amount (equivalent to $131 452) were to be assessed for a fully funded IBA loan rather than the usual split loan.

1.7 IBA lending officers are located in 12 locations across Australia as well as IBA’s national office in Canberra. The role of these officers is to develop and maintain relationships with customers, and provide ongoing loan management and home ownership support. As at August 2015, there were 71 staff allocated directly to the program.

1.8 In 2013–14, 11 per cent of new loans were to customers in remote and very remote areas, with most loans (45 per cent) being made in inner regional areas (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Indigenous Business Australia loans by geographical classification, 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of IBA data.

Operational and performance targets

1.9 IBA reports publicly on a range of aspects of IHOP. The key targets and performance indicators measure the success of the program in targeting lending and assistance to customers as appropriate to their circumstances and need, and the facilitation of home ownership in remote Indigenous communities (see Table 1.1 for 2014–15 deliverables and indicators). As noted in Portfolio Budget Statements 2014–15: Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio (Indigenous Business Australia), the program’s overall success is assessed in terms of increasing the percentage of Indigenous Australians who are home owners, although no target or performance data is included in the Portfolio Budget Statements or Annual Reports in this respect.

Table 1.1: Program deliverables and key performance indicators for 2014–15

|

|

Target |

|

Key deliverables |

|

|

Number of new home loans |

560 |

|

Aggregate loans in the portfolio |

4505 |

|

Key performance indicators |

|

|

Percentage of loans to applicants who have an adjusted combined gross annual income of not more than 125% of IBA’s income amount |

80% |

|

Percentage of loans to applicants who are first home buyers |

90% |

|

Number of remote Indigenous communities in which IBA is actively facilitating home ownership opportunities |

12 |

Source: IBA Portfolio Budget Statement 2014–15.

1.10 To support the achievement of the program’s key targets and performance indicators, IBA has identified internal operational targets at monthly intervals across the loan administration cycle. These operational targets support measuring progress towards the outcomes of the program, critical success factors to achieving lending targets (for example, applications on hand and number of invitations issued to applicants), the program’s budget and administration.

Previous reviews and evaluations

1.11 A number of reviews have been undertaken of IHOP and/or selected aspects of IHOP and the IBA. These are provided at Appendix 3. Issues and areas for improvement identified in these reviews include:

- encouraging borrowing or the transfer of applicants to mainstream lenders;

- standardising procedures for calculating income and determining satisfactory credit checks;

- improving ongoing loan management and customer contact activities (excluding arrears related issues);

- improving online access to more detailed information about IBA’s programs and products and the development of an online application process;

- improving data quality to avoid duplicate customer records in IBA’s systems;

- better measuring of social and commercial outcomes from IHOP;

- reducing the length of the loan application process and increasing the time available to find a home once loan approval has been granted;

- strengthening the security and protection of customer information; and

- developing greater consistency of processes and decision-making practices in relation to loans.

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

1.12 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of IBA’s management and implementation of the IHOP.

1.13 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- IBA has management arrangements that support equitable access to IHOP and the achievement of the long-term outcomes of IHOP, including whether clear objectives have been established for the program, program activities are consistent with program objectives and directed towards target customers;

- service delivery is responsive to the needs of target customers and loan assessments are undertaken in line with IHOP policy and procedure, supporting the achievement of program outcomes; and

- performance measurement and reporting mechanisms support accurate assessments of progress towards program outcomes, and achieved performance is in line with the Australian Government’s expectations.

1.14 The audit examined the program activities since the integration of the Home Ownership on Indigenous Land program into IHOP in July 2012. Where available, data was considered over a longer period.

1.15 The audit methodology included:

- examination of relevant entity documentation, reports, reviews and Cabinet submissions, including program plans, risk management plans, loan guidelines, and data entry and monitoring protocols;

- examination of IBA’s correspondence and briefings with the responsible Minister;

- assessment of processes supporting loan assessment and examination of a sample of assessments to determine their consistency against established criteria and processes;

- examination of activities to support outcomes in remote communities;

- analysis of home loan data from IBA;

- interviews with IBA staff and a sample of IBA customers; and

- review of communication received through the citizens’ input facility.

1.16 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost of $591 446.

2. Program management

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether IBA has management arrangements that support equitable access to the IHOP and the achievement of the long-term outcomes of IHOP. This chapter assesses whether:

- clear objectives have been established for the program, and program activities are consistent with these objectives;

- access to the program is based on clear eligibility criteria and target customers are prioritised for loans in line with program objectives; and

- risks to the achievement of program objectives are identified and managed, including the risk of fraud and conflict of interest.

Findings

- The program objective is defined differently in different documents. The difference is whether the program assists people who do ‘not qualify for mainstream finance’ or people who have ‘difficulty accessing mainstream finance’. This affects who is approved for a home loan through the program.

- IBA has established eligibility criteria for entry into the program. However, a key threshold of whether a customer is able to access mainstream finance is not tested in most cases at the expression of interest stage when initial eligibility is assessed. However an assessment does occur at the application stage.

- The current lending activity of the program is not aligned with one of the target groups of low income earners. Further, IBA lending activity is moving towards higher income households. This is reflected by data and policy changes to increase income thresholds for loan products.

- The number of ineligible applicants is increasing. Some of the reasons applicants are denied, such as unsatisfactory credit history, tenancy records and insufficient deposits, also reflect the barriers to home ownership the program tries to overcome.

- IBA has a process for prioritising applications; however the criteria used for prioritising customers do not align with the target customer group.

- At the program level, IBA has identified risks but controls are not always implemented. IBA has processes in place for managing the risks of both fraud and conflict of interest. However, IBA does not investigate all allegations of fraud which is inconsistent with IBA and government policy.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made two recommendations. The first is directed to IBA and is aimed at aligning program activities with the program’s objectives. The second is directed to the Australian Government and supports a review of IHOP and whether a government‐run loan program is the most efficient mechanism to support Indigenous home ownership outcomes.

Program objectives and activities

2.1 The program was established in 1975 to provide housing loans to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who would find securing mainstream finance difficult. In 2015, the aim of the program remains to facilitate increased levels of home ownership through affordable housing loans to Indigenous Australians who would generally not qualify for housing finance elsewhere.

2.2 The objective the program is defined differently in different publications. In the 2013–14 Annual Report IBA states that the objective of IHOP is to provide affordable loans to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, particularly those on lower incomes, and first home buyers who have difficulty obtaining home loan finance from mainstream commercial lenders. The Portfolio Budget Statement refers to both ‘Indigenous Australians who would generally not qualify for housing finance elsewhere’ and people ‘who have difficulty accessing’ mainstream finance. Although both groups can be difficult to define, this difference in language indicates some inconsistency in who might be considered eligible for a home loan through IBA.

2.3 Funds for the administration of IHOP and for loan capital are provided through a mix of government appropriations, interest and loan repayments received. The departmental program expenses are the administrative costs for delivering the program, including activities involved in facilitating home ownership opportunities in remote and Indigenous communities, and the legal, administrative and operating costs associated with undertaking lending and managing IBA’s loan portfolio. A large component of the program expenses each year is the result of a decrease in the recorded asset valuations, which represents a loss on IBA investments.23 Table 2.1 shows that program expenses have been increasing as have the numbers of loans in the portfolio.

Table 2.1: Total departmental program expenses against number of approved loans and portfolio over five years

|

|

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|

Total departmental program expenses |

$35.0m |

$57.6m |

$31.9m |

$34.3m |

$37.5m |

$29.1m |

|

Number of approved loans |

363 |

606 |

404 |

664 |

556 |

517 |

|

Number of loans in the portfolio |

– |

3685 |

3841 |

4110 |

4335 |

4471 |

Note: The increase in program expenses in 2010–11 was due to the temporary transfer of $56 million in unused funds from the Home Ownership on Indigenous Land (HOIL) Program and resulted in additional loan approvals during the year.

Source: IBA annual reports.

Loans offered by Indigenous Business Australia under the program

2.4 IBA offers basic home loans for purchasing, constructing, renovating and refinancing. The main differences in the loans offered by IBA and mainstream finance loans are the lower deposit requirements and slightly longer standard loan terms of up to 32 years. These terms have not changed substantially in approximately 30 years. IBA does not offer additional products that may be available through a mainstream lender such as savings accounts, credit cards and offset accounts.

2.5 In 1982, the introductory interest rate for an IBA loan was 5 per cent gradually increasing until the IBA Home Loan Rate was reached. At the time, the standard variable home loan rate offered by banks was 13.5 per cent.24 In 2015, the IBA standard introductory interest rate as advertised on IBA’s website was 4.5 per cent (which can be reduced to 3 per cent for some low income earners) and the IBA Home Loan Rate was 5.25 per cent.25 IBA’s standard introductory interest rate is set at an initial commencing rate for a minimum period of one year and then escalates by 0.5 per cent (or 0.25 per cent for loans in Emerging Markets26) each year until it reaches the IBA Home Loan Rate.27 The IBA Home Loan Rate is benchmarked against the average of the standard variable interest rates of a basket of competitive home loan lenders for owner-occupied properties (Market Rate) rounded (up or down) by up to 0.25 per cent. The rate is to be reviewed when there is a significant independent movement by three of the major banks represented in the basket.28 In comparison, the average interest rate on variable loans offered by mainstream lenders was 4.5 per cent in 2015. This indicates that the value of an IBA home loan to a customer is less beneficial than when the program began and in some cases may not be concessional.

2.6 IBA does offer a lower deposit threshold and longer loan term than mainstream lenders. In 2015, the standard minimum deposit was $3000 or 5 per cent of the purchase price. For some low income earners the minimum deposit can be reduced to $1500.29 In 1982, the minimum deposit requirements were set at 5 per cent of the purchase price. The standard loan term is 32 years for an IBA loan compared to 30 years with a mainstream lender.30 This can be increased to 45 years to assist in reducing the amount of monthly repayments.

2.7 In March 2015, in response to the withdrawal of first home owner support initiatives, IBA introduced a new Fee Finance loan product. This allows customers who do not have sufficient savings to borrow the money they need to pay for other costs associated with the purchase of a home (for example, stamp duty, legal fees and registration costs). The interest rate for this product is the IBA Home Loan Rate with a maximum loan term of 10 years.31

Indigenous Home Ownership Program customers

2.8 IBA’s target customers, as noted in the program objective, are Indigenous first home buyers who have difficulty obtaining home loan finance from other financial institutions. The program is also designed to target Indigenous Australians on lower income levels, with limited savings and credit impairments, limited experience with loan repayments and people in designated emerging market communities where IBA is active. IBA has not taken steps to further define or analyse the size or characteristics of its target customers in any detail. The program also seeks to help Indigenous Australians overcome additional barriers to home ownership.

Eligibility for access to the program

2.9 A key threshold for entry into the program is whether a customer can access mainstream finance. IBA’s policy states that an applicant must not be able to source the required housing loan amount from a mainstream lender and that confirmation of this must be provided.32 IBA’s home ownership fact sheet states that applicants should, in the first instance, check if they qualify for a housing loan from another lender.

2.10 In 82 out of 100 files examined by the ANAO, at the expression of interest stage, there was no assessment of whether applicants would be able to obtain the required home loan amount from a mainstream lender. Of the remaining 18 files examined, some had comments about the likelihood of an applicant not being able to access mainstream finance, some applicants from remote areas did not need to meet this criterion and some assessments of this criterion were not located. There was no documentation from a mainstream lender in these files.

2.11 At the application stage, only five out of 64 files examined had comments against this criterion that reflected that the applicants had tried to source the required home loan from a mainstream lender. In a further four of the 64 files, comments indicated that an applicant would be able to access funds through a mainstream lender. In the majority of the remaining 55 files there was evidence that IBA considered whether applicants would be able to access mainstream finance. In the sample, the main factors considered by IBA when assessing this criterion included low income, bad credit history, lack of savings and/or deposit, loan affordability and employment status. However, IBA lending officers are not given any guidance on what factors to consider when making these assessments, or what threshold applicants must satisfy to meet this criterion.

2.12 By not enforcing the requirement for confirmation to be provided that an applicant cannot source required finance from a mainstream lender, IBA increases the risk that it is lending to applicants that may be able to access housing loans from the mainstream market, which is outside of the program’s design.

Lending to lower income Indigenous Australians

2.13 IBA approved 2552 loans from 2009–10 to 2013–14. Of these 2552 loans, 93 per cent were to first home buyers which are a clear target group for the program. In contrast, Table 2.2 shows that the home loans approved by IBA over this period do not reflect IBA target customers in relation to lower income Indigenous Australians. While there is significant lending activity at the medium income level, the proportion of loans to low income households is only 2.3 per cent. Also, the proportion of loans to higher income households is increasing over time. In 2011–12, 52 per cent of loans were to customers earning over 100 per cent of the IBA Income Amount.33 This percentage increased to 59 per cent in 2012–13 and 57 per cent in 2013–14.

Table 2.2: Distribution of IBA loans from 2009–10 to 2013–14 according to income level and bands

|

Income level |

Weekly income range |

Percentage of IBA loans |

|

Very Low |

Negative/ Nil income |

0.0% |

|

Low |

$1–$599 |

2.3% |

|

Medium |

$600–$1499 |

51.8% |

|

High |

$1500–$2999 |

44.0% |

|

Very High |

$3000 or more |

1.9% |

Source: ANAO analysis of ABS population data and IBA data.

Note 1: Income includes all non-adjusted income for applicants.

Note 2: The income levels are derived from taking the average low, middle and high average weekly household income, reported by the ABS in 2011–12 Household Income and Income Distribution, Australia (cat. no. 6523.0), and situating income ranges around these averages. The income ranges relate to those used by the ABS to report the household income of Indigenous Australians and have been aggregated to correspond with the relevant income levels.

2.14 IBA advised that it would be desirable to have a greater percentage of its home lending to customers with lower incomes. However, for some lower income customers the maximum amount IBA can lend will not be sufficient to enable them to purchase a home. If IBA is no longer able to lend to lower income customers, IBA should consider adjusting its product suite or providing advice to government to confirm this change in program direction (see program risks IBA has identified in paragraph 2.25).

Recommendation No.1

2.15 In order to align program activities with the program outcomes, the ANAO recommends that IBA either:

- identify the current barriers to home ownership; increase lending to lower income earners; change the loan products to better suit lower income earners; or

- provide advice to government to confirm a change in the program’s target customers.

Indigenous Business Australia’s response: Agreed.

2.16 IBA notes that ANAO has identified the impact that significant shifts in home loan affordability—particularly due to rising house prices and reduced state government assistance— has had on the targeting of IBA home loan assistance. IBA is currently working with Government, through the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, on proposals to refine assistance targeting policies, and is open to further refinement as necessary to ensure that this critical issue is appropriately addressed. IBA’s intention is to strengthen income tests, add an asset test, and strenuously implement requirements for customers to show that they have been unable to obtain funding from commercial lenders. Mechanisms to enhance affordable borrowing capacity of customers are also under exploration, particularly the relative effectiveness of the application of concessional interest rates versus provision of upfront grants. IBA will continue efforts to target communities where mainstream lenders are absent (e.g. community‐titled land), which will further skew overall targeting toward the lower income bands. IBA has committed to provide Government, through its Minister, with regular reports on the outcomes of its targeting policies, which will improve transparency of the application of assistance and provide opportunity for ongoing refinement of underlying targeting policies. In the event that these measures are not fully successful in re‐orienting targeting to lower income segments, IBA will engage with the Government to re‐set the program’s targeting policy framework that is reflective of structural changes in its customer profile.

Ineligible applicants

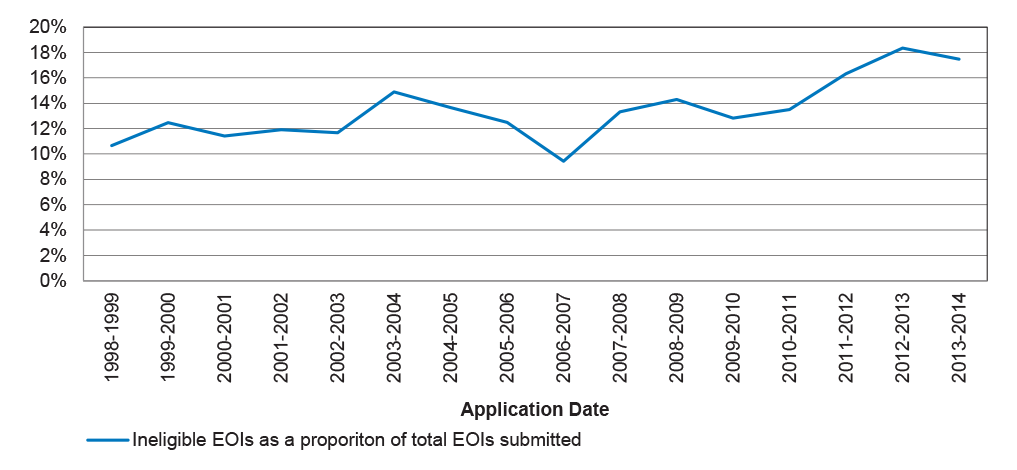

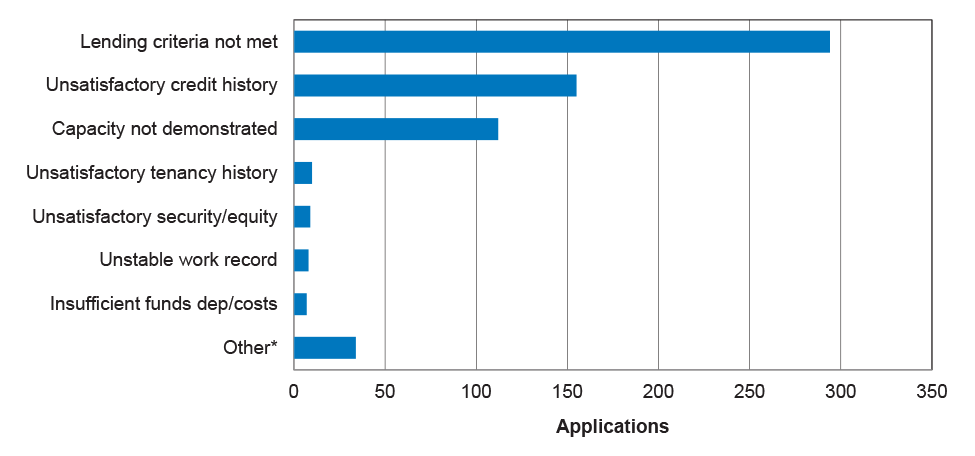

2.17 From 1998–99 to 2013–14 IBA assessed 3431 expressions of interest as ineligible out of a total of 25 110 expressions of interest received. Further, the number of ineligible assessments per year increased from 113 in 1998–99 to 347 in 2013–14. Figure 2.1 shows ineligible assessments as a proportion of expressions of interest received. Fifty-five per cent of the 3431 expressions of interest deemed as ineligible had no reason recorded in IBA’s systems, and a further 32 per cent had ‘lending criteria not met’ recorded as a reason for being assessed as ineligible. Without recording or analysing the reasons that applicants are being made ineligible IBA is unable to use this information to tailor its program to its target customers.

Figure 2.1: Expressions of interest assessed as ineligible as a proportion of total expressions of interest received by IBA from 1998–99 to 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis of IBA data.

IBA lending activity by location

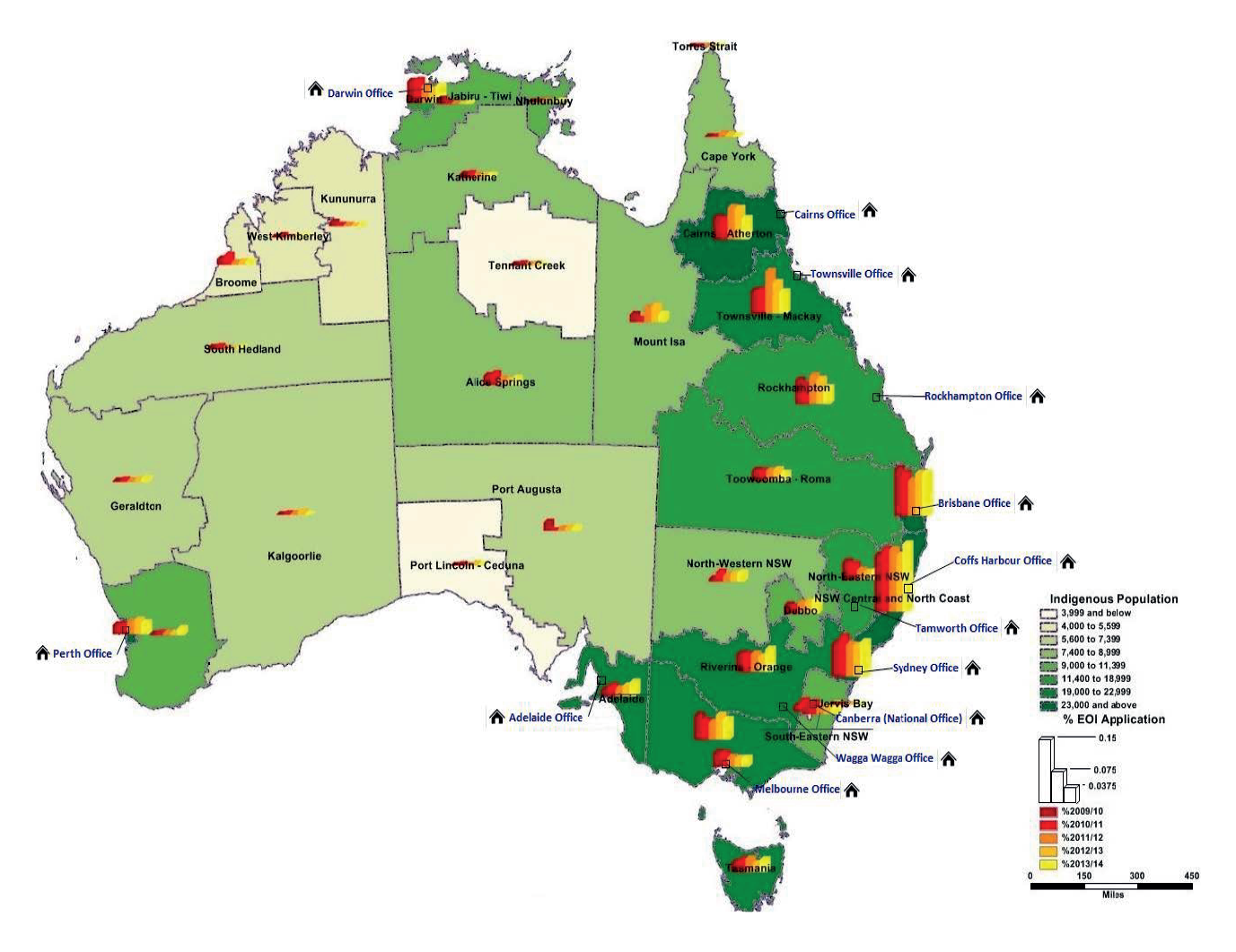

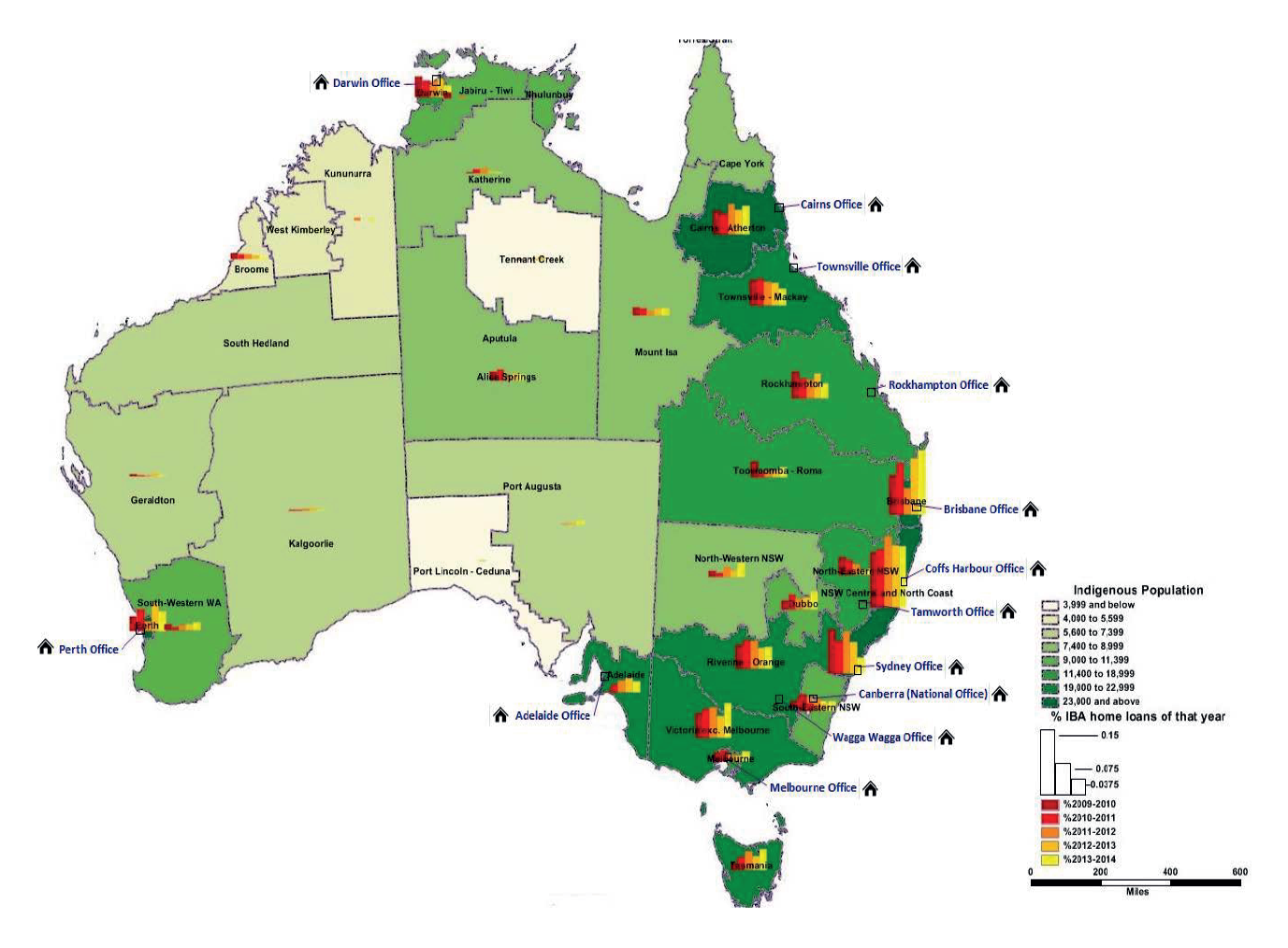

2.18 IBA identifies in its Corporate Plan and program policy that service delivery should be aligned with locations of greatest need and realistic opportunity for home ownership. As at the 2011 census, there were 531 039 Indigenous people across Australia located predominantly in Brisbane, NSW Central and North Coast, and Sydney and Wollongong regions.34 Figure 2.2 and Figure 2.3 show that in general, as expected, there is more program activity in areas of higher Indigenous population. However, the level of activity in some areas does not reflect the density of population.

Figure 2.2: Percentage of expressions of interest received from 2009–10 to 2013–14 and the number of Indigenous Australians in each region

Source: ANAO analysis of ABS population data and IBA data.

Figure 2.3: Percentage of IBA loans approved from 2009–10 to 2013–14 and the number of Indigenous Australians in each region

Source: ANAO analysis of ABS population data and IBA data.

2.19 Figure 2.4 shows that there are some areas where IBA lending exceeds the proportion of the Indigenous population, and other areas where lending is significantly lower than the proportion of the Indigenous population. This indicates a pattern of potential underservicing in some locations and overservicing in other locations. For example, while the proportion of loans made in Brisbane closely reflects the proportion of the Indigenous population, in Darwin there is a much higher distribution of loans relative to population share. Conversely, in the Sydney-Wollongong region, there is a much lower proportion of loans relative to population share.

2.20 IBA advised that loan approvals are a result of applications received from eligible applicants and that a range of factors influence the distribution of loans. Such factors could include property prices, an applicant’s affordability, consumer debt and differences in government initiatives across jurisdictions. No evidence was provided by IBA of any detailed analysis of results in particular areas to determine the influence of these factors. While the program has traditionally been demand driven, given the changes in the lending environment and customer income levels, there is scope for IBA to take a more proactive approach to analysing the Indigenous population and identifying areas of greatest need and realistic opportunity for home ownership in line with program strategies. At the request of the IBA Board in April 2015, IBA has initiated work to investigate the future demand for the program. This includes engaging a consultant to develop a tool to forecast the immediate, five year, ten year and 20 year trends in demand for the program. This will inform the development of a growth strategy for the program.

Figure 2.4: Comparison of Australia’s Indigenous population to IBA home loans since 1998–99 by percentage

Source: ANAO analysis of ABS population data and IBA data.

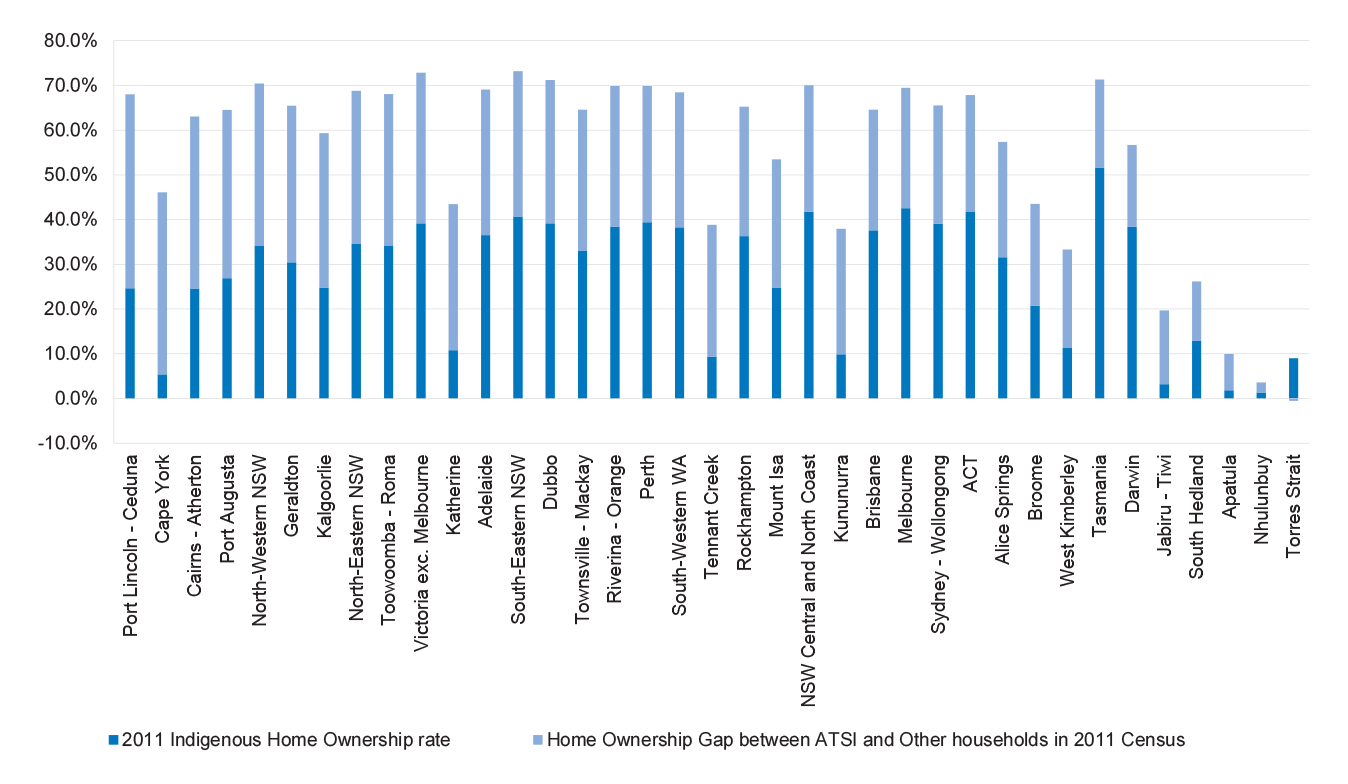

2.21 Figure 2.5 sets out a comparison of the Indigenous home ownership participation rate against the non-Indigenous home ownership participation rate to identify areas where the gap in home ownership was highest. The results show that areas with the highest proportion of IBA lending, Brisbane, Sydney and the NSW North Coast, have comparatively smaller gaps in the home ownership rate between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population. There is scope for IBA to investigate demand in areas where the home ownership gap is highest and potentially look to increase lending activity in these areas.

Figure 2.5: Gap between the Indigenous and the non-Indigenous home ownership participation rate in 2011

Note: Locations are sorted from the largest to smallest gap in the home ownership participation rate. In the Torres Strait, the home ownership rate for Indigenous people is higher than for non-Indigenous people so the value of the gap in this location is negative.

Source: ANAO analysis of ABS Census data 2011.

Demand for IBA home loans

2.22 IBA uses the expression of interest register as a key indicator of demand for housing loans. In recent years, IBA has seen a decline in demand for its home loans by eligible customers as indicated by zero applicants waiting on the expression of interest register since 30 June 2013. Other indicators of demand include the number of expressions of interest and applications received which have remained relatively stable over recent years (see Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: Indicators of demand for IHOP

|

|

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

Number of expressions of interest received |

1948 |

1907 |

1986 |

|

Number of invitations issued |

1064 |

1128 |

1097 |

|

Number of applications received |

858 |

965 |

943 |

|

Withdrawn applications |

260 |

348 |

306 |

Source: ANAO analysis of IBA data.

2.23 In order to meet end of year performance targets, IBA sets periodical targets for key points in the loan process such as enquiries, expressions of interest and applications received. In January 2015, IBA was tracking behind its operational targets for the 2014–15 financial year in relation to the number of applications received and applications on hand indicating a decline in demand. In February 2015, the IBA Board approved temporary changes to lending parameters to increase lending activity. The temporary changes were that customers earning up to 165 per cent of the IBA Income Amount35 (equivalent to $131 452) were to be assessed for a fully funded IBA loan rather than the usual split loan and that the standard introductory interest rate was to be reduced to 4 per cent for most customers. The temporary changes were introduced by IBA in response to the economic and housing affordability climate and the reduction in interest rates but evidence was not provided of analysis to support this position. The increase in the income thresholds for IBA applicants indicates a move away from IBA target customers on low to middle incomes. IBA advised that as a result of the temporary measures it was able to meet the budgeted lending amount target for 2014–15 but it did not meet lending key deliverables.

Prioritisation of eligible applicants

2.24 IBA has a policy of prioritising eligible applicants for loans based on a points system and maintaining a register of applicants who meet a minimum set of the loan eligibility criteria. IBA then allocates each applicant a point score based on the criteria outlined in Table 2.4. The points system has been in place since 1989. ANAO analysis shows that customers with higher point scores had shorter wait times on average than those with low point scores, indicating that the prioritisation system is working as intended. The system of prioritisation used by IBA does not however reflect or weight whether the applicant is a first home buyer, on a low to medium income and/or could not access mainstream finance, in line with the objectives of the program.

Table 2.4: Criteria for prioritising the expression of interest register

|

Criteria for allocating points |

Points |

|

For each Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person in the applicant’s family. |

1 |

|

Applicants renting a house from an Indigenous community housing organisation or a state / territory government body. |

2 |

|

Families paying more than 35 per cent of their total gross income in rent payments. |

1 |

|

Applicants who meet the minimum deposit / equity requirements excluding first home owners grant. |

1 |

|

Applicants who meet the minimum deposit / equity requirement plus have an additional deposit amount of $3000 or more excluding first home owners grant. |

1 |

Source: IBA Indigenous Home Ownership Program Policy, March 2015, p. 16.

Program risks

2.25 IBA considers that it adopts a conservative approach to risk in relation to its financial affairs, compliance and governance issues and in relation to reputational and operational matters. However, in order to achieve its objectives, IBA identifies that a level of risk must be accepted in delivering its programs. For 2014–15, IBA identified two risks at the program level and associated controls to mitigate these risks. These are outlined in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5: Key risks and controls for the program in 2014–15

|

Key risks |

Controls |

|

Home lending products do not address customer affordability and other housing needs. |

|

|

Inability to attract sufficient customers to pursue home ownership under current service delivery model constraints. |

|

Source: IBA Indigenous Home Ownership Program Business Plan, 2014–15.

2.26 IBA has made changes to its lending practices, products and procedures as a result of tracking behind lending targets for the 2014–15 financial year, as discussed in paragraph 2.23. However, there was limited evidence of analysis and formal monitoring to investigate potential areas of under or overservicing, despite a decrease in demand and an increase in the number of loans to high income households. IBA is currently investigating options to grow the program’s lending capacity.

Credit risk

2.27 Credit risk has been identified by IBA as a major type of risk impacting the program (although this is not specified in the business plan). IBA has identified that it accepts a moderate to high risk appetite for its lending programs. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority identifies that some of the risk limits that a residential mortgage lender should consider include limits relating to:

- serviceability criteria, such as, net income surplus and other debt servicing measures;

- frequency and types of overrides to lending policies; and

- maximum expected or tolerable portfolio default, arrears and write-off rates. 36

2.28 The credit management risks that IBA accepts can include: loans approved with minimum deposit and savings; loan terms over 32 years; and loans approved with a monthly surplus of less than $500 after loan repayments. Further, IBA has a higher loan to value ratio than a mainstream lender. IBA attempts to manage this credit risk through the loan approval process where decision-making is delegated to staff at different levels depending on how far outside of the standard IBA lending policy parameters the terms of the loan sit. However, IBA does not track the frequency or factors that cause loans to sit outside policy parameters or flag loans that are approved outside policy for future monitoring. This is discussed further in Chapter 3 as part of loan approvals and arrears management.

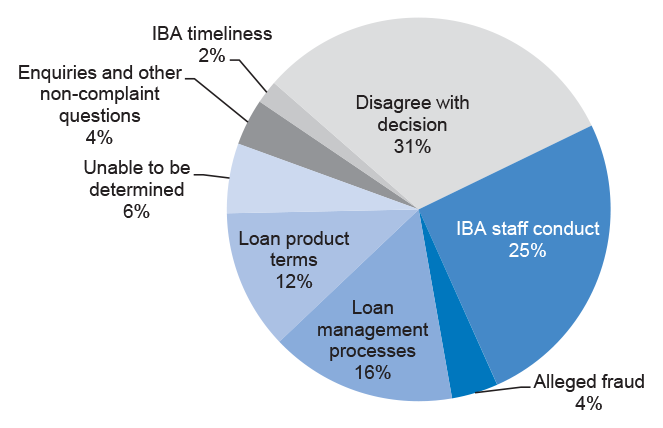

2.29 The key factors recorded by IBA for declining loan applications are set out in Figure 2.6. Some of these reasons, such as unsatisfactory credit history, tenancy records and insufficient deposits also reflect some of the risks IBA tries to mitigate and some of the barriers the program tries to overcome.

Figure 2.6: IBA reasons for declining loan applications

* Includes categories: able to obtain external loan; combined repayments exceeds limit; not going to reside in property; and own investment property.

Source: ANAO analysis of decline reasons.

2.30 In delivering IHOP IBA must balance credit risks associated with an applicant not being able to service a loan, against achieving the program’s objective of providing loans to applicants who would normally be able to obtain finance through a mainstream lender. However, it is not evident that IBA has undertaken analysis of ineligibility and decline reasons and used this information to inform the Board’s development of program policy. While it is reasonable that some customers may not meet IBA requirements, IBA also needs to remain mindful of the barriers the program is attempting to overcome.

Fraud control

2.31 IBA states in its Risk Management Plan and Fraud Control Plan that it has zero appetite for fraud risk and instances of fraud. From 1 July 2011 to 30 March 2014, eight cases of suspected fraud were reported to the IBA Fraud Control Officer (FCO) in relation to IHOP. Three out of four cases examined by the ANAO related to the alleged receipt of a home loan when the person was allegedly not of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent. In these cases the FCO determined that there was insufficient evidence to conduct an investigation.

2.32 IBA advised the ANAO that IBA has no powers of investigation and cannot compel the production of documents or require responses to questions. This appears to be inconsistent with IBA’s Fraud Control Plan and the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework, which requires entities to investigate and appropriately act upon allegations of fraud, even if considered minor.37

2.33 IBA also advised the ANAO that information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent, and other personal information is sensitive information under the Privacy Act 1988 and IBA is required to obtain this information from the customer with their consent. IBA considers that there is a risk that IBA may inadvertently contravene the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 if it makes additional inquiries about customers. However, IBA already requires customers to consent to IBA collecting and using information about Aboriginality or Torres Strait Islander descent to assess an application for the product or service requested from IBA.

2.34 IBA has changed its processes for confirming Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent in accordance with an IBA Board decision in 2014. The new policy requires that applicants alone will make a legally-binding statutory declaration to demonstrate their Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent rather than also seeking confirmation from an acceptable organisation. This change was considered to be in line with community expectations and reduce red-tape for applicants. IBA also considered that in the event a false declaration was made, IBA actions would likely be limited to removing any interest rate subsidy on the home loan and IBA would not be able to apply an immediate repayment obligation.

Managing conflicts of interest

2.35 Prior to assessing loan applications IBA staff are required to consider whether a conflict of interest may exist. If a conflict of interest exists, IBA’s procedural instructions state that these transactions must be assessed by another staff member and approved or declined by a delegate who has no conflict of interest. The procedural instructions also require that a declaration of a conflict of interest and subsequent management of the transaction must be recorded by making a note in IBA’s systems and placing a copy of the note in an applicant’s physical file.

2.36 IBA advised the ANAO that there is no central register for conflict of interest declarations and any conflict is recorded on an applicant’s physical file. As such, IBA was not able to readily identify the extent of declared conflicts of interest from 1 July 2011–24 December 2014. Without a central register of conflicts of interest, IBA management has limited visibility over the occurrence and management of declared conflicts of interest.

Recommendation No.2

2.37 In order to support continued progress in closing the gap in home ownership outcomes, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Government assess whether a government-run loan program is the most efficient mechanism to support Indigenous home ownership outcomes.

Indigenous Business Australia’s response: Noted.

2.38 IBA notes the ANAO observation and conclusion that it is timely to review IBA’s underlying home lending business model. IBA accepts that its small scale—relative to bank lenders—results in relative operational inefficiencies, higher costs, and restricted product and service range. Further, IBA agrees with the ANAO’s view that the current business model may not be sufficient to close the gap in home ownership outcomes, and that a change in business model—that better utilises its capital—is required. IBA is keen to explore alternative business models that allow more efficient use of its capital base through public‐private sector arrangements with commercial banks, which could deliver larger numbers of home loans, expanded product range, and improved cost efficiency. IBA is currently working with the Government to explore a new business model with these principles.

3. Service delivery

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether service delivery is responsive to the needs of target customers and loan assessments are undertaken in line with IHOP policy and procedures, supporting the achievement of program outcomes. This chapter assess whether:

- the loan application process is accessible to target customers;

- IBA has undertaken loan assessments consistently, in line with IBA policy and procedures, and decisions are appropriately recorded; and

- loan aftercare services are effective and are based on identified risks and customer needs to minimise loan default.

Findings

- The current design of the application process is duplicative and time consuming.

- IBA has not progressed in moving any aspects of IHOP online despite identifying these as key actions for improving service delivery.

- IBA loan assessments were mostly undertaken in line with IBA policies and procedures, and decisions were recorded appropriately. However, the ANAO identified a number of inconsistent considerations in loan assessments and documentation to support decisions. In some cases, these inconsistencies led to different outcomes for applicants. In other cases, the process was extended as applicants were required to resubmit paperwork.

- The manual processing of paper-based applications requires review to mitigate the risks of error. IBA has implemented some quality assurance measures to mitigate these risks however these are still relatively new.

- IBA does not have a system to identify and track high risk customers to minimise loan default prior to them falling into arrears.

- The current process is time consuming and administratively burdensome. IBA could reduce the cost of the program by reducing the level of administration and introducing online service delivery mechanisms.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at making service delivery more responsive to the needs of IBA customers and increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of IBA’s business practices.

Accessibility of the loan application process

3.1 IBA’s two-stage application process involves an applicant registering an interest in a housing loan (expression of interest stage) and then applying for a housing loan (loan application stage). This two-stage process is designed to make an assessment of an applicant’s initial eligibility, filtering out applicants that may not be ready for home ownership, and for managing IBA’s resources due to limited funding allocations.

3.2 The expression of interest form is eight pages long and requires applicants to fill out information against approximately 68 questions (depending on individual circumstances).38 Applicants who meet a minimum set of the loan eligibility criteria are put onto the expression of interest register. Applicants will be invited to apply for a housing loan as funds become available. Once invited, applicants submit a formal loan application. The loan application form requires applicants to fill out similar information to the expression of interest form, plus approximately 60 additional questions. Four of the documents required to be submitted at the expression of interest stage are required to be resubmitted at the loan application stage.

3.3 The two-stage application process can be a lengthy and difficult process for Indigenous customers. Thirty-seven of the 51 customers interviewed by the ANAO said that they found the application process medium to hard, with 24 out of 51 requiring some kind of assistance from IBA. The main difficulty customers interviewed by the ANAO encountered was with aspects of the paperwork, including the volume of paperwork.

3.4 IBA’s application process is paper-based and applicants are unable to complete any aspect of the process online. IBA stated in its 2012–13 Annual Report that it was reviewing how it could improve customer service delivery through the introduction of online services. However, as at June 2015 IBA had not moved any aspects of service delivery online. The ANAO considers that IBA should prioritise the implementation of contemporary delivery mechanisms and improve service delivery. This is in line with IBA’s Corporate Plan and its 2013–15 Information and Communication Strategic Framework.

Promotional activities of IHOP to support access by target customers

3.5 IBA’s key promotional activities include the IBA website, advertising, brochures, use of social media, information sessions and media releases. Prior to 2015, IBA has not prioritised undertaking additional marketing and promotion activities. Out of the 51 customers interviewed by the ANAO, 38 (75 per cent) had heard about IHOP through word of mouth, where a family member or friend had previously had a loan through IBA. In addition, more marketing and promotion was the most common change customers interviewed wanted to see to the program. Customers interviewed also reported that they knew many people that were interested in a housing loan but did not know about IBA. IBA has acknowledged that a wider audience of Indigenous Australians may not be aware of the assistance on offer by IBA.

3.6 In March 2015, the IBA Executive approved a Communications Plan for IHOP. This plan includes strategies to attract more customers to IHOP, improve the customer experience and celebrate the 40 year anniversary of IHOP but there are limited new measures to connect with potential customers. As such, there is scope for IBA to increase its promotional activities to make the program more accessible.

Expression of interest and loan application assessments

3.7 IBA takes a staged approach to assessing loan applications in line with the application process outlined above. This involves IBA: manually entering applicants’ information into IBA’s systems; and assessing applicants’ expressions of interest against minimum loan eligibility criteria and loan applications against a full set of loan eligibility criteria. The loan application assessment process is set out in Figure 3.1. The loan eligibility criteria IBA uses to assess expressions of interest and loan applications are set out in Table 3.1

Figure 3.1: Loan application assessment process

Note: From August 2015, IBA assess applicants’ eligibility against loan eligibility criteria (a) to (g).

Source: ANAO analysis of IBA’s Indigenous Home Ownership Program Policy and procedural instructions.

Table 3.1: Loan eligibility criteria

|

Loan eligibility criteria |

Criteria to be applied at each stage |

||

|

|

Expression of interest |

Home loan application |

|

|

(a) |

Be of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent supported by documentation that is acceptable to IBA. |

Y |

Y |

|

(b) |

Not be able to source the required home loan amount or part thereof from a mainstream lender. |

Y |

Y |

|

(c) |

Be able to produce satisfactory evidence that their combined gross annual income (CGAI) is within the income range detailed in the relevant tiers.A |

Y |

Y |

|

(d) |

Have a stable work record. |

N |

Y |

|

(e) |

Be able to contribute a minimum deposit / equity of $3,000 or 5 per cent of the cost of the home, whichever is the lesser. |

Y |

Y |

|

(f) |

Be able to meet all legal and incidental costs associated with the purchase or construction of the home. |

Y |

Y |

|

(g) |

Have the capacity to meet required housing loan repayments. |

Y |

Y |

|

(h) |

Demonstrate reasonable likelihood of having capacity to meet the loan repayments over the whole term of the loan. |

N |

Y |

|

(i) |

Not have repayments (proposed housing loan repayments) which exceed 30 per cent of total gross income or combined housing loan and consumer debt repayments which exceed 35 per cent of total gross income. |

N |

Y |

|

(j) |

Have a demonstrated satisfactory tenancy record, if currently renting a home. |

N |

Y |

|

(k) |

Have a credit history that is satisfactory to IBA. |

N |

Y |

|

(l) |

Not already own, or be paying off, a rental or investment property. |

N |

Y |

|

(m) |

Reside in the property that is the security for the loan upon loan settlement or final loan advance. |

N |

Y |

Note A: CGAI Tiers are used to calculate the maximum loan amount that IBA will provide and accordingly, the amount that is required to be sourced from another lender.

Note: From August 2015 IBA assess applicants’ eligibility against standard loan eligibility criteria (a) to (g).

Source: IBA, Indigenous Home Ownership Program Policy, March 2015, pp. 10–11.

3.8 To assess whether IBA has undertaken loan assessments in line with IBA’s policies and procedures, including loan eligibility criteria, the ANAO undertook a review of a sample of 100 IBA customer files. The sample consisted of files where an applicant had submitted an expression of interest between July 2011 and June 2014. Each file was paper-based and had progressed to a different stage of the application process but not all progressed to an IBA loan.

Expression of interest assessments

3.9 IBA lending officers make an assessment of a potential customer’s eligibility based on the information that an applicant includes on the expression of interest form. The information on the expression of interest form covers details of income and financial commitments such as personal loans, tenancy arrangements, savings, credit cards and debt arrangements. IBA also requires applicants to provide supporting documentation at this stage including:

- confirmation of Aboriginal descent and signed privacy consent;

- proof of income (for example, two recent payslips); and

- evidence of ability to provide the deposit or equity and pay legal and stamp duty costs (for example, a copy of recent bank, building society, and/or credit union statements).

3.10 In the ANAO’s sample of IBA customer files, the ANAO found that IBA did not regularly demonstrate that it considered whether applicants could obtain finance from a mainstream lender (see 2.10). The ANAO also found some inconsistencies in how lending officers had applied the procedural instructions in making an initial assessment of potential customers’ eligibility. These included:

- discrepancies in what was considered a complete and acceptable Confirmation of Aboriginal Descent form39;

- different calculation methods for income, affecting split loan determinations; and

- discrepancies in whether applicants were required to submit verification of income and other supporting documentation.

3.11 In some cases, these inconsistencies led to different outcomes for applicants. In other cases, the process was extended as applicants were required to resubmit information or supporting documentation.

3.12 The ANAO also found that some applicants did not complete sections of the expression of interest form or provide the required supporting documentation and IBA lending officers did not always verify all the information provided by applicants. IBA advised that as the expression of interest assessment is an initial assessment of applicant’s eligibility, and not a credit decision, not all information is required to be verified. If IBA is not going to verify the supporting documentation that applicants submit at the expression of interest stage, IBA could consider reducing the burden on applicants by removing the requirement for applicants to provide supporting documentation at the expression of interest stage.

Loan application assessments

3.13 Loan application assessments were more comprehensive and supported by verified documentation than expression of interest assessments. However, as with the expression of interest assessments, the ANAO identified a number of inconsistencies in the considerations for different criteria. The main areas of concern included:

- no evidence was provided in the majority of files that IBA had sought any form of confirmation that an applicant was unable to access mainstream funding. While IBA advised that this may be assessed by virtue of the applicant’s circumstances, IBA lending officers are not given any guidance on what factors to consider when making these assessments, or what threshold applicants must satisfy to meet this criterion (see paragraph 2.11);

- limited guidance on which factors should be considered when assessing capacity to service a loan, leading to different factors being taken into account by IBA when assessing capacity. Further, there was not always sufficient detail to understand the reasons supporting the assessment of capacity;

- some variation in the amount of living costs considered by IBA. For example, the average living cost for one person is $469 per month and varies, on average, by $195 above and below this. This affects affordability determinations as to whether an applicant can afford a loan; and

- no clear benchmark or guidance for what is considered a satisfactory credit history leaving scope for inconsistency in decision-making in these criteria. The ANAO identified 17 out of 64 files where IBA did not obtain all of the information required to assess credit history.

Decision-making

3.14 At the loan application stage, IBA takes a risk-based approach to determining the appropriate decision-maker. Decisions are delegated to staff at different levels depending on how far an application sits outside of the standard IBA lending policy, including loan eligibility criteria. Delegations are underpinned by IBA Instrument of Delegations and supported by IBA’s loan approval system, which alerts a lending officer when a loan term is outside of the standard IBA lending policy (for example, where an applicant’s combined housing loan and consumer debt repayments exceed 35 per cent of total gross income). The lending system also has some controls to separate the recommending officer and the approving delegate.

3.15 In the majority of the files assessed by the ANAO: there was some evidence to support decisions made; the reasons for decisions were recorded on files; and 37 out of 43 housing loan submissions were signed by the correct delegate. However, in four cases some minor discrepancies were identified and in two cases the assessor and decision-maker was the same person.

3.16 Where an application for a loan is declined, IBA policy is that the applicant is to be notified of the reasons for declining the application. In the ANAO’s sample, eight out of 43 loan applications had been declined. In four of the eight letters sent to applicants IBA identified the reasons for declining the loan. In two of the remaining four files copies of the letters declining the applications were not located. In the remaining two files the letters sent by IBA did not adequately explain all of the reasons for the decision made. Consequently, the applicants affected by the decision may not fully understand the decision, be given an opportunity to have the decision properly explained and decide whether to exercise their rights of review or appeal.

Quality assurance of decisions and lending practices

3.17 IBA advised that it seeks to mitigate the risk of administrative error through quality assurance measures such as the Network Assurance Review. The Network Assurance Review was introduced in September 2014 and replaced a program of self-audits conducted by individual lending officers. Some issues underlying the introduction of the new process included concerns over risks in the consistency in treatment of applicants and the application process, not following procedures resulting in detriment to customers and improving efficiencies.

3.18 The Network Assurance Review involves assessing 24 newly approved loan files per month against a number of financial and compliance risks identified by IBA. Some of these risks include whether the correct primary and secondary applicant has been used to determine combined gross annual income and whether credit history has been adequately investigated. The results are collated and reported to the General Manager. The goal is to identify trends and potential improvements for IBA business processes. IBA reported that the process is relatively new and there has not been the opportunity to acquire robust amounts of data. IBA anticipates leveraging this report to undertake deeper analysis into areas of potential risk that have been identified and prepare separately an in-depth report on the potential area of risk. Results from the first seven months of the review process show that IBA lending officers’ compliance with IBA lending policy and procedures when undertaking loan assessments increased from 85.5 to 91.5 per cent.

Timeframes

3.19 The two-stage application process can be time consuming for both applicants and IBA. Between 2010–11 and 2012–13 the average time taken by IBA to assess an eligible applicant’s expression of interest was 16 days. Similarly, the average time taken by IBA to assess an approved applicant’s home loan application was 10 days. These timeframes do not take into account the time taken to provide any missing or incomplete information such as the privacy consent form or other documentation and therefore do not reflect the length of the process. They also do not take into account those applicants that may have been made eligible pending the applicant satisfying the necessary requirements for initial eligibility within a specified time period.

3.20 Figure 3.2 sets out the average number of days from 2008–09 to 2012–1340 for all the required documentation to be collected from applicants and for IBA to assess: initial eligibility at the expression of interest stage; and whether to approve or decline a loan application at the loan application stage. For the same period, the average number of days eligible applicants spent on the expression of interest register before being invited to apply or withdrawing their application decreased from 399 days in 2008–09 to 42 days in 2012–13.41

Figure 3.2: Expression of interest and loan application assessment timeframes

Note: Timeframes include requesting additional information from customers and submissions to National Office.

Source: ANAO analysis of IBA data.

3.21 From 2010–11 to 2012–13, the average number of days between applicants submitting an expression of interest and a decision being made about their initial eligibility increased from 38 to 60 days. The average number of days from applicants submitting a housing loan application to a decision being made to approve or decline a loan increased from 48 to 52 days. Streamlining the application process would save both IBA and customers time. Further, there are cost benefits to IBA from reducing the amount of processing time associated with expressions of interest and applications.

Loan aftercare and arrears management

3.22 IBA considers that its personalised ongoing support for customers operates beyond the normal mandate of a bank or other financial institutions. IBA’s procedural instructions set out that once a loan has been settled, borrowers should be provided with ongoing support to assist them:

- manage their housing loan and other responsibilities associated with home ownership; and

- continue the positive relationship established with IBA.

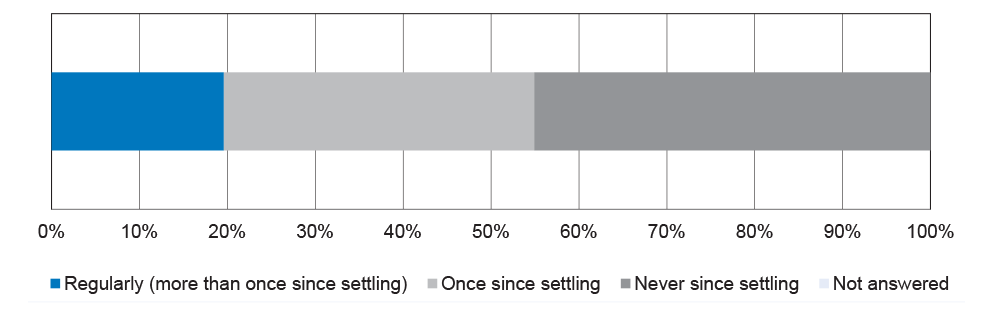

3.23 A part of IBA’s loan aftercare support is, where practical, arranging to visit a new borrower within the 12 months following loan settlement. Of the 51 customers interviewed by the ANAO, 18 stated that they had heard from IBA once since settling on their loan. Of the customers not contacted by IBA since settling, 12 had contacted IBA with regards to an issue with their loan or repayments. The results are shown in Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3: IBA contact with customers after loan settlement

Source: ANAO analysis of customer interviews.

3.24 IBA does not have a system or mechanism for monitoring after-loan care on an ongoing basis. As a consequence, IBA cannot track whether customers are receiving adequate after-loan services. This includes monitoring whether customers’ circumstances have changed, putting them at higher risk of dropping into arrears or defaulting on their loan.

3.25 IBA customers are unable to access any of their loan accounts online. This means that if a customer wants account information outside the routine statement period, they would need to contact IBA and request an account statement which is then mailed to the customer. Customers are therefore unable to monitor and manage their account or access account information on a regular basis.

IBA’s management of arrears

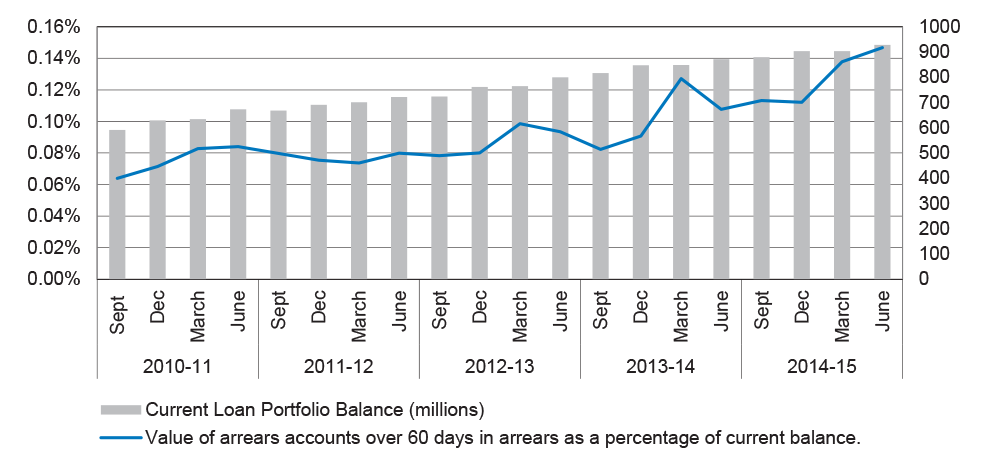

3.26 IBA sets itself an internal target to maintain the total value of arrears from accounts over 60 days in arrears below 0.20 per cent of the total of IBA’s loan portfolio balance. At June 2015 IBA was meeting this target (see Figure 3.4). However, the total value of arrears from accounts over 60 days in arrears has doubled between December 2011 and June 2015.

Figure 3.4: Total value of arrears from accounts over 60 days in arrears as a percentage of IBA’s loan portfolio balance, from September 2010 to June 2015

Source: ANAO analysis of IBA’s internal reports from September 2010–June 2015.

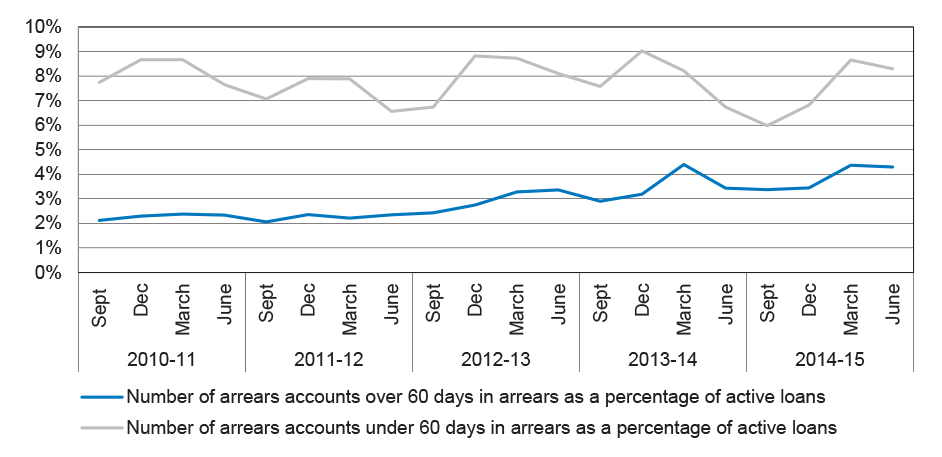

3.27 IBA also sets internal targets for the number of accounts over and under 60 days in arrears as a percentage of all active loans in IBA’s portfolio. In 2013–14, IBA’s target for the number of accounts over 60 days in arrears was 3.5 per cent. In 2014–15 IBA increased this target to 3.75 per cent to reflect changes in the market, such as increased pressure in regional economies. For the same period, the target for the number of accounts under 60 days in arrears was 8.5 per cent. On average, for 2014–15, the number of loan accounts over 60 days in arrears was 3.9 per cent of active loans and the number of loan accounts under 60 days in arrears was 7.4 per cent of active loans (see Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5: Number of accounts over and under 60 days in arrears as a percentage of active loans, from September 2010 to June 2015

Source: ANAO analysis of IBA’s internal reports from September 2010–June 2015.

3.28 In 2014–15 IBA met two out of three of its internal targets for arrears. Despite this there has been an overall increase in the number and value of accounts over 60 days in arrears since 2010. Additionally, IBA changed its target for the number of accounts over 60 days in arrears to accommodate for an increase in arrears rates in 2013–14.

3.29 There are likely to be a number of drivers behind the increase in IBA’s arrears, including economic factors. However, IBA does not have a way of systematically recording and analysing why customers drop into arrears or processes in place for identifying and tracking customers at higher risk of dropping into arrears. This includes tracking customers that are a higher credit risk, in particular those with loans approved with minimum deposit and low savings, split loans, and loans to low income earners.