Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Indigenous Early Childhood Development. New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services

The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of the Department of Health and Ageing’s administration of New Directions. In this respect the ANAO considered whether:

- planning processes were developed to support the program’s objectives and rationale;

- implementation arrangements were clearly defined and aligned to the objectives of the program; and

- robust performance management arrangements had been established and were in use by the department.

Summary

Introduction

1. In December 2007, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) committed to a national effort to close the gap in life expectancy and opportunity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. COAG identified six targets that, if achieved over the long term, would increase the life expectancy, health, education and employment opportunities of Indigenous Australians. While all Australian Governments had previously committed to raising the standard of Indigenous Australians’ health to that of other Australians, COAG’s commitment was the first time Australian governments had agreed to be accountable for reaching this goal by placing its targets within a timeframe.1 One of the targets agreed by COAG is to halve the mortality rate of Indigenous children within 10 years (by 2018).

2. Currently, Indigenous children do not enjoy an equal start in life. Indigenous children are more likely to be born with certain congenital anomalies, and to live with some chronic health conditions, than non-Indigenous children.2 Many Indigenous families are also not using the maternal and early childhood services that would help give their children a healthy start in life.

3. Poor maternal health, growing up in households with multiple disadvantages, or having poor access to effective services can affect children’s development, health, social and cultural participation, educational attainment and employment prospects.3 Evidence for investing in the early years in all aspects of a child’s development, health, education, family and community support is strong, and is particularly compelling for children from disadvantaged backgrounds.4 Research shows that a greater focus on interventions in the critical years from conception to age eight, can accrue substantial benefits for Indigenous children and can also contribute significantly to the achievement of the COAG targets relating to later life outcomes.5

Infant and child mortality

4. Infant mortality, defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics as deaths of children aged under one year6, has been traditionally viewed as an indicator of the general level of mortality, health and wellbeing of a population and as such has received special attention in public health policy. Most childhood deaths occur in the first year of life and the mortality rate of infants is generally different to that of children aged one year and over.

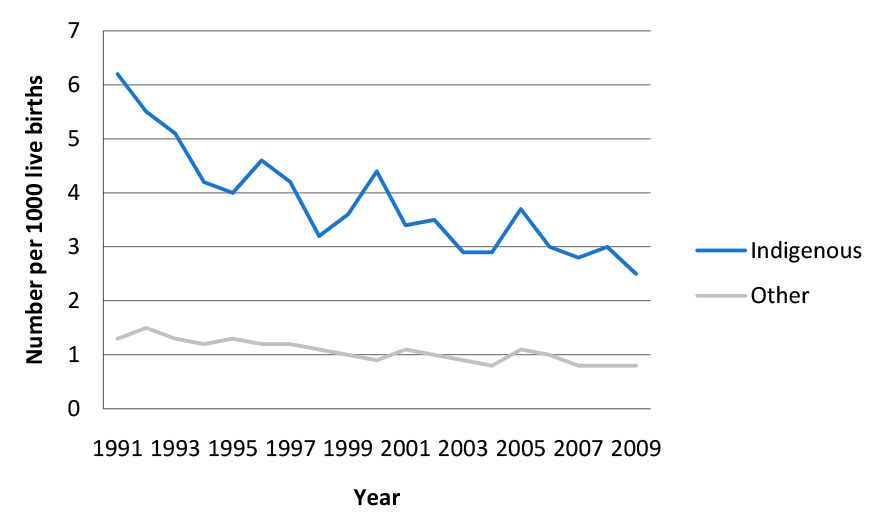

5. Long-term mortality data over the period 1991 to 2009 shows that the Indigenous child mortality rate is declining and the gap between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous rate is also narrowing. However, the mortality rate is still considerably higher for Indigenous children and Indigenous children still experience significantly worse health outcomes compared to non-Indigenous children.7 Figure 1 shows that the gap between mortality rates for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children aged 0 to 4 years narrowed from a rate of 4.9 to 1.7 per 1000 between 1991 and 2009.8 Figure 1 also shows, that despite the narrowing gap, mortality rates for Indigenous children remain higher than those of non-Indigenous children.

Figure S.1: Child (0 to 4 years) mortality rates 1991–2009

Source: ABS, Deaths, Australia, 2010, cat no. 3302.0

6. International and Australian research shows that improving access to quality antenatal healthcare and maternal health services combined with other factors, such as better nutrition, the reduction in risk behaviours during pregnancy (such as alcohol and tobacco use), and annual health checks for children, can reduce the risk of poor health outcomes among Indigenous children.9 While 97 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers access antenatal services at least once during their pregnancy,10 the challenge has been to facilitate more frequent and earlier access as Indigenous mothers are accessing these services later in their pregnancy and less frequently than other mothers.11

7. There are a range of factors and policy interventions that influence child mortality rates. The Australian Government has also invested in measures aimed at directly addressing Indigenous maternal and child health as part of the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (NIRA) in support of COAG targets. Under the Indigenous Early Childhood Development National Partnership, specific attention is being given to improving access to, and use of, maternal and child health services. Governments in all Australian jurisdictions have jointly committed to expenditure of $165.3 million over the 5 year period 2007–08 to 2011–12.12 The Australian Government’s contribution of $90.3 million13 is provided through the New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services (New Directions) program administered by the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA).

New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services

8. The New Directions program was established by the Australian Government as a separate program on 1 January 2008. It was subsequently subsumed into the Indigenous Early Childhood Development National Partnership, (IECD NP) from 1 July 2009 following the development of the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (NIRA) in November 2008. A range of national partnerships were developed to give effect to the NIRA. Among these, the IECD NP commits to improving child health and education through integrated service provision, linking and building on existing services and helping to ensure that services are tailored to specific needs of rural, regional and urban communities. The IECD NP has three elements:

- Element One: integration of early childhood services through Children and Family Centres;

- Element Two: increased access to antenatal care, pre-pregnancy and teenage sexual and reproductive health; and

- Element Three: increased access to, and use of, maternal and child health services by Indigenous families (New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services.

9. Elements One and Two are implemented by state and territory governments using Australian Government funding. Parallel arrangements have been put in place for the delivery of Element Three by the Australian Government through DoHA.

10. The Australian Government’s commitment to Element Three of $90.3 million over five years represents the Australian Government’s own purpose contribution. Of this amount, $86.1 million has been allocated for provision to service providers. As maternal and child health is seen to be a shared responsibility between the Australian and state and territory governments, under Element Three the states and territories have also made direct investments of $75 million to deliver antenatal, postnatal and maternal and child health services to Indigenous families14 alongside the services funded by the Australian Government.

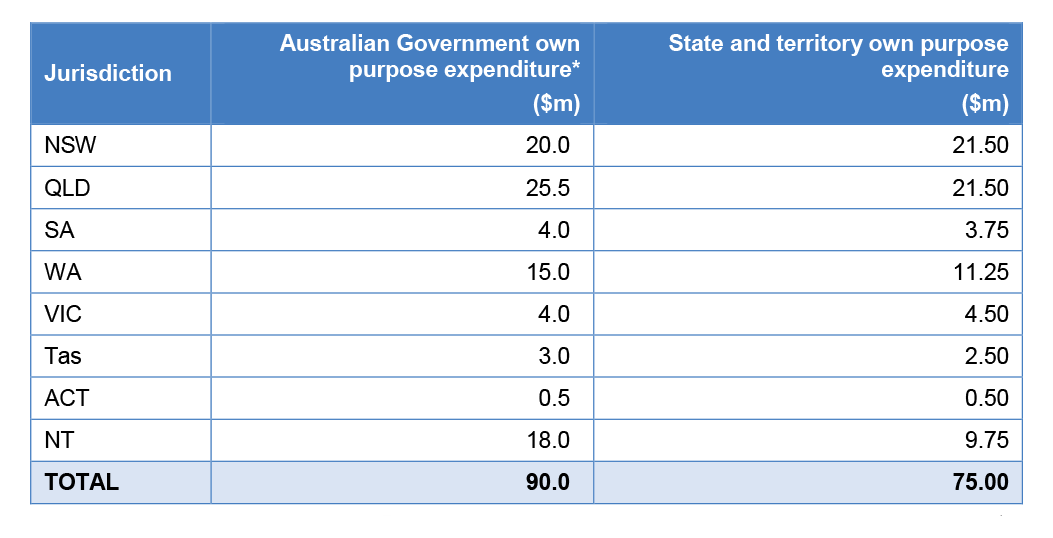

11. Australian Government funds are apportioned across jurisdictions taking into account the Indigenous population in each state and territory and applying a loading for remote service delivery. Unlike other National Partnership Agreements, where Australian Government funds are provided to state and territory governments for implementation, these funds are paid by DoHA directly to the selected service providers in each state and territory under grant agreements. Table 1 shows the indicative proportion of New Directions Australian Government funds across the jurisdictions to 2011–12 and the separate funding contributions of each state and territory.

Table S.1: New Directions, indicative proportion of Australian Government and state and territory funding 2007–08 to 2011–12

Source: Closing the Gap: National Partnership Agreement of Indigenous Early Childhood Development. The IECD identified total funding of $90.3m. The sum of the components does not add to the total because of rounding.

* Australian Government funds are paid directly to service providers in each state and territory.

12. The Australian Government announced in the 2011–12 Budget that the program would receive additional funding of $133.8 million over the four year period from 2011–12.

13. The IECD NP identifies that the New Directions program is designed to provide increased access to, and use of, Indigenous maternal and child health care in regions of high need with an emphasis on early presentation and regular visits throughout pregnancy. This is to be facilitated through the Australian Government funding the expansion of child and maternal health services and by increasing the number of health professionals working in the identified priority regions so that more Indigenous children can be seen and treated–directly resulting in better health.

14. The objective of the program is to deliver services in five priority areas:

- antenatal and postnatal care;

- standard information about baby care;

- practical advice and assistance with breastfeeding, nutrition and parenting;

- monitoring of developmental milestones, immunisation status and infections; and

- health checks and referrals to treatment for Indigenous children before starting school.

Audit objectives and criteria

15. The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of the Department of Health and Ageing’s administration of New Directions. In this respect the ANAO considered whether:

- planning processes were developed to support the program’s objectives and rationale;

- implementation arrangements were clearly defined and aligned to the objectives of the program; and

- robust performance management arrangements had been established and were in use by the department.

16. Fieldwork was conducted in DoHA’s National Office and in its New South Wales, Queensland and Victorian state offices. The ANAO visited 12 health service providers funded under the program located in the same states.

Overall conclusion

17. Good maternal health is an important factor in achieving good health outcomes for children, and a low infant mortality rate is a major contributor to improving overall life expectancy. Through the National Indigenous Reform Agreement, Australian governments have committed to a set of development targets, including halving the gap in mortality rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children under the age of five years by 2018. Improving access to, and use of, maternal health care services is a key objective of the Indigenous Early Childhood Development National Partnership (IECD NP). To this end the Australian Government committed an initial $90.3 million between 2007–08 to 2011–12 to expand access for Indigenous women to maternal and child health services. A further $133.8 million has been committed to maintain these services over a further four years from 2011–12.

18. Overall, the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) has been effective in establishing and implementing the New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services (New Directions) program, consistent with the objectives set by government. To meet the Government’s required implementation timeline within the first six months of the program, the department undertook a truncated process to identify priority sites and engage the initial five service providers. In subsequent annual funding rounds, however, DoHA made effective use of its existing local level coordination and consultative mechanisms to support the planning and implementation of the program by inviting applications from providers which were then assessed against agreed criteria. Against an original target of engaging 50 service providers by 2011–12, as at November 2011 DoHA was funding 80 providers to deliver a combination of agreed services in all states and territories. Total program expenditure had reached $65 million of the $86.1 million allocated for provision to service providers. By the end of 2011–12 the department anticipates that it will be funding 82 service providers with no further providers to be funded.

19. The responsibilities for local program implementation have been devolved to DoHA’s state and territory offices and the department has put in place approaches to promote a general level of consistency across the states and territories in the selection of sites, providers and the services to be offered. Risk management approaches have been less well developed and the department would benefit from an improved ability to aggregate information at the national level about the delivery of the program in each state and territory.

20. Between 1991 and 2009 the gap between the mortality rates for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children has narrowed. The Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council considered that if current trends continue, it is likely that Indigenous child mortality rates will fall within the COAG target by 2018.15 A range of factors influence mortality rates and improving access to, and use of, maternal and child health services is likely to be an important contributor to this trend, although its actual contribution will vary depending upon the relative importance of other influencing factors such as housing, education, employment and other social determinants.

21. A consequence of there being a range of influencing factors is that identifying the specific contribution of any one factor is challenging. Nonetheless, in terms of the specific objectives contained in the IECD NP of increasing the access to, and use of, maternal and child health services, DoHA’s performance management approach could be improved as it currently only captures the numbers of service providers being funded as a proxy indicator for improved access. Collecting and reporting data that provides an indication on whether New Directions has been effective in improving the use of these services would significantly strengthen the understanding of the specific changes resulting from the program’s funding in this respect.

22. The ANAO has made one recommendation to support the effective administration on New Directions. The recommendation relates to DoHA’s approach to service provider and program performance management and the need for impoved access to, and capture of, performance data to more effectively manage and support the program.

Key findings

Program development and planning for effective service delivery

23. The New Directions program went through two separate implementation periods; the first from January 2008 as a Labor Government election commitment, and the second from July 2009 following its integration into the IECD NP. In the initial stages of implementation, DoHA gave appropriate consideration to most of the key aspects of program development, including how the program would be governed, as well as providing clarity about the policy objectives and rationale, program components, delivery model, and implementation strategy. However, the audit found that less attention was given in the planning stage to the program performance and monitoring arrangements and to risk identification.

24. In adapting the program to become part of the IECD NP, DoHA engaged with relevant government stakeholders at both the federal and state/territory levels through the COAG supported Working Group on Indigenous Reform. In the process of incorporating the program into the IECD NP, the program’s objective was refined by adding a focus on the use of maternal and child services to the original access objective. However, this change has not been reflected in the Australian Government’s IECD NP Implementation Plan, annual report and associated documents.

Program implementation

25. The first round of funding was implemented in a tight timeframe because of the Government’s desire to quickly implement election commitments, and funding was provided to a small number of providers through a select tender process. Subsequent funding rounds have been more tightly managed through DoHA’s annual coordination and planning processes. Coordination of program effort has taken into account other Australian and state/territory government initiatives directed at child and maternal health. DoHA recognised that the continued successful delivery of services through New Directions required a significant level of planning and coordination across DoHA’s state and territory offices (STOs).

26. Implementation responsibilities have been devolved to DoHA’s STOs. DoHA has put in place mechanisms to promote coordination and procedural consistency in regards to regional planning and site selection, service provider selection and management. DoHA has also used the pre-existing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Forums to develop relationships with state and territory stakeholders, such as health departments and Indigenous medical services. The forums have proven to be an effective way for the department to consult jurisdictions on priority regions, on the identification of service gaps and to coordinate delivery of maternal and child health services.

27. The implementation of the program is dependent on the effective operation of service provider organisations and DoHA has developed regular processes for assessing risk at this level. Until December 2011, DoHA STOs undertook risk assessments using a standard Risk Assessment Profile Tool (RAPT) to assess corporate governance and financial management. Since December 2011 risk assessments have been outsourced but continue to use the standard RAPT. Program implementation would be strengthened by a stronger approach to risk management at the program level to complement the operational risk assessments of providers. The 2009 Implementation Plan, covering the Australian Government’s contribution, indicated that a risk management plan was to be completed and reviewed each year. However, this has not occurred. DoHA is aware of this issue and has indicated that efforts are underway to complete the plan.

Performance monitoring and reporting

28. There is presently little performance data available to support an assessment of the extent to which New Directions has contributed to improvements in maternal and child health and the quality and effectiveness of the services provided. The performance indicators in use relate to the number of service providers and the timeliness of enlisting new service providers. The indicators, while helpful to measure activity under the program, do not provide sufficient insight into the program’s achievements with regard to improving access to, and use of, maternal and child health services as intended by the IECD NP.

29. In the initial development phase of the program, DoHA deliberately sought to limit the amount of information it would require from service providers. This decision was influenced by concerns at the time from the sector about administrative burden and a desire to streamline data collection. While it is important to ensure the costs involved in collecting data for performance indicators are appropriate to the benefits gained from the resulting information in this case the emphasis on minimising performance reporting requirements has had a significant impact on the quality of performance data available to assist managers and external stakeholders. As a consequence, very few performance indicators and targets were developed and there was no agreement to any baseline information against which to measure change. This has limited DoHA’s ability to understand the program’s effectiveness and, in particular, the impact and contribution it is making to the outcomes of the IECD NP. This will also constrain the ability of the department to conduct an evaluation of the program, the results of which are planned for release in 2014, some seven years after the commencement of New Directions.

30. Proportionality is a key consideration in determining the comprehensiveness of a performance measurement framework. As the Government has committed a further $133.8 million to continue the program, it would be timely for DoHA to develop a stronger approach to collecting performance information so as to better assess whether the specific objectives of the program are being achieved.

Summary of agency response

31. A summary of the Department of Health and Ageing’s (DoHA) response to the report, dated 9 May 2012, is as follows.

The Department of Health and Ageing welcomes the ANAO report and notes that work is underway to enhance the performance monitoring of the New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services program. The Department is also implementing strategies to apply a stronger approach to risk management of the program.

The Department agrees with the report’s recommendation.

Footnotes

[1] Australian Human Rights Commission, Closing the Gap: National Indigenous Health Equality Targets (2008), viewed online <www.hreoc.gov.au/social_justice/health/targets/index.html> [accessed 2 September 2011].

[2] K Rudd, N Roxon, J Macklin & S Smith, New directions: An equal start in life for Indigenous children, May 2007, Canberra, Australian Labour Party, May 2007, p. 6.

[3] Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2011, Productivity Commission, Canberra.

[4] Australian Medical Association, Lifting the Weight - Low Weight Babies: An Indigenous health burden that must be lifted, AMA, 2005. [Internet] available from <http://ama.com.au/node/3185>

[accessed 9 June 2011].

[5] Council of Australian Governments, National Partnership Agreement on Indigenous Early Childhood Development, 2009, p.3. [Internet] available from <http://www.coag.gov.au/coag_meeting_outcomes/2009-07-02/docs/NP_indigenous_early_childhood_development.pdf> [accessed 6 June 2011].

[6] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Deaths, Australia, cat. no. 3302.0, Canberra, ABS, 2009, p. 13.

[7] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, A Picture of Australia’s Children, cat. no. PHE112, Canberra, AIHW, 2009.

[8] Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2011, Productivity Commission, Canberra, p. 4.24.

[9] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, A Picture of Australia’s Children, cat. no. PHE112, Canberra, AIHW, 2009. Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework Report 2010, AHMAC, Canberra, p. 8.

[10] ibid., p. 130.

[11] Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework Report 2010, AHMAC, Canberra, p. iv.

[12] Council of Australian Governments, National Partnership Agreement on Indigenous Early Childhood Development, July 2009, paragraph 34. [Internet]. COAG, available from <http://www.coag.gov.au/coag_meeting_outcomes/2009-07-02/docs/NP_indigenous_early_childhood_development.pdf> [accessed 12 October 2011].

[13] This funding includes both administered and departmental funds and a small amount for scholarships. The Puggy Hunter Memorial Scholarship Scheme aims to help address the under-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in health professions. The scholarship provides financial assistance to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who are undertaking study or are intending to undertake study in a health related discipline. The scholarships are outside the scope of this audit.

[14] Council of Australian Governments, National Partnership Agreement on Indigenous Early Childhood Development, July 2009, paragraph 35. [Internet]. COAG, available from <http://www.coag.gov.au/coag_meeting_outcomes/2009-07-02/docs/NP_indigenous_early_childhood_development.pdf> [accessed 12 October 2011].

[15] Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework Report 2010, AHMAC, Canberra, p. i.