Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Implementation of the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing in the NT

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the implementation of the NPARIH in the Northern Territory from the perspective of the Australian Government.

Summary

Introduction

1. The need to improve the social and economic outcomes of Indigenous Australians was widely recognised in 2007, when the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to a partnership between all levels of government to work with Indigenous communities to close the gap on Indigenous disadvantage. The resultant National Indigenous Reform Agreement committed the Australian, state and territory governments to significantly increased activity in seven key areas to reduce Indigenous disadvantage. The seven areas, referred to as building blocks, are: early childhood; schooling; health; economic participation; healthy homes; safe communities; and governance and leadership.

2. In developing the National Indigenous Reform Agreement, COAG has emphasised that action in one of the building blocks can influence progress in another. In this respect, improved housing has been identified by COAG as being able to make positive contributions to life expectancy, education and employment outcomes and reduced infant mortality. Housing need in remote Indigenous communities was considered to be at critical levels, with many houses overcrowded and in very poor condition. In response, COAG endorsed the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing (NPARIH) in November 2008.

3. The objectives of the NPARIH over the ten-year period 2008-09 to 2017-18, are to:

- significantly reduce severe overcrowding in remote Indigenous communities;

- increase the supply of new houses;

- improve the condition of existing houses in remote Indigenous communities; and

- ensure that rental houses are well-maintained and managed in remote Indigenous communities.

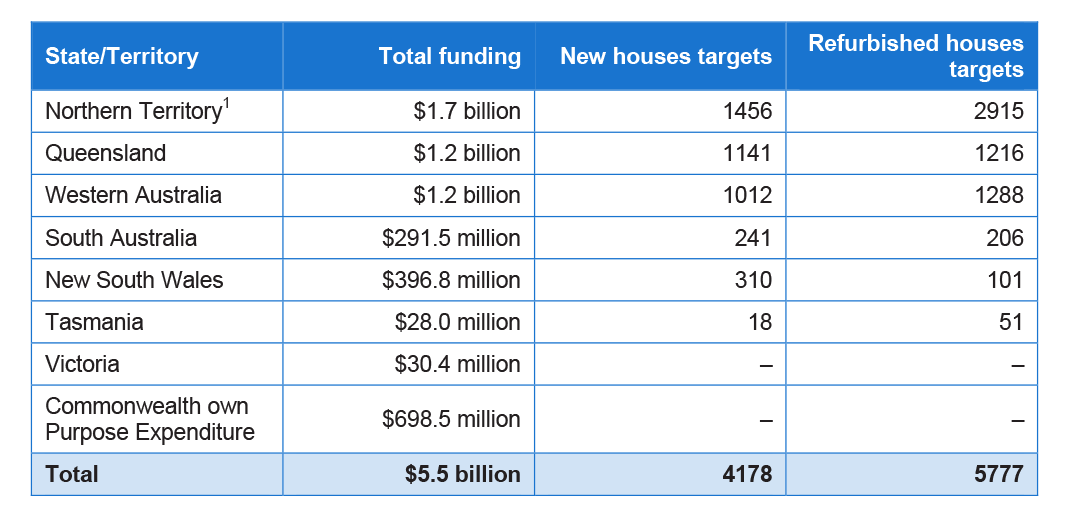

4. The NPARIH is being delivered in all state and territory jurisdictions in Australia apart from the Australian Capital Territory. Each state government and the Northern Territory Government is separately responsible for program delivery in its own jurisdiction, and specific targets and funding levels have been agreed between the Australian Government and each jurisdiction, as shown in Table 1. Underlying these targets is a series of reform activities specific to each jurisdiction in the areas of public housing and tenancy management in remote Indigenous communities.

Table S.1: Australian Government NPARIH funding and targets by jurisdiction (2008–09 to 2017–18)

Source: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

Note 1: The original NPARIH target was 2052 refurbished houses; the target was increased to 2915 following the intergovernmental review of the program in 2009, and consideration of community needs and previous notional allocations. In the Northern Territory two categories of refurbishments have been introduced: rebuilt houses, where between $100 000 and $300 000 is invested, and refurbished houses, where an investment of more than $20 000 but less than $100 000 is made.

Implementing the NPARIH in the Northern Territory

5. Overall funding of $2 billion over ten years is available to implement the NPARIH in the Northern Territory. This includes $1.7 billion to be provided by the Australian Government and a $240 million contribution by the Northern Territory Government. An additional $77 million is also being provided by the Australian Government from other funding sources. In line with the implementation arrangements agreed in all jurisdictions for the NPARIH, the Australian Government provides funding for housing and infrastructure works, and for property and tenancy management reform. The Northern Territory Government is responsible for the delivery of a program of capital works, including new, rebuilt and refurbished houses, and the associated infrastructure. The Northern Territory Government also delivers property and tenancy management services to remote Indigenous communities. Both governments have a shared responsibility for delivery of the overall outcomes sought through the NPARIH.

6. While the most visible objective of the NPARIH is the improvement of the physical housing stock, this is one of four key elements which are to be implemented as a package. In addition to the capital works element, the other three elements are: land tenure reform; reformed property and tenancy management arrangements; and increased local Indigenous employment.

7. The capital works component of the NPARIH includes the delivery of works in 73 remote Indigenous communities and a number of town camps1 in the Northern Territory. Within this component, major works are being undertaken to construct 1456 new houses and develop housing related infrastructure in 16 of the 73 communities and the Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Borroloola Town Camps. Across all 73 communities and town camps, a total of 2915 houses will also be either rebuilt or refurbished.

8. Reforms to land tenure, in particular the development of long-term leases over Indigenous land, are designed to support government investment in housing and infrastructure and to provide a right of access to undertake property maintenance activities. The Northern Territory NPARIH implementation plan states that the ‘government[s] must have access to and control of the land on which construction will proceed for a minimum period of 40 years’.2 The Australian Government’s preferred position is to negotiate whole-of-township leases, covering 40 to 99 years.

9. To help improve the sustainability of the investment in housing, the Northern Territory Government is progressively implementing standardised property and tenancy management arrangements for public housing in remote Indigenous communities. These arrangements are expected to assist with the maintenance of houses and to extend the useful life of houses in remote Indigenous communities to 30 years. Standardised arrangements did not previously exist, as public housing stock in remote communities was managed by individual Indigenous community housing organisations.

10. Lastly, increasing Indigenous economic participation is a key cross-cutting objective of the National Indigenous Reform Agreement. The NPARIH, accordingly, includes measures to build economic development opportunities in communities by way of increased local training and employment in construction and housing management. The Australian and Northern Territory Governments have agreed that local Indigenous people should make up a minimum of 20 per cent of the labour force involved in the program.

Recent Indigenous housing programs in the Northern Territory

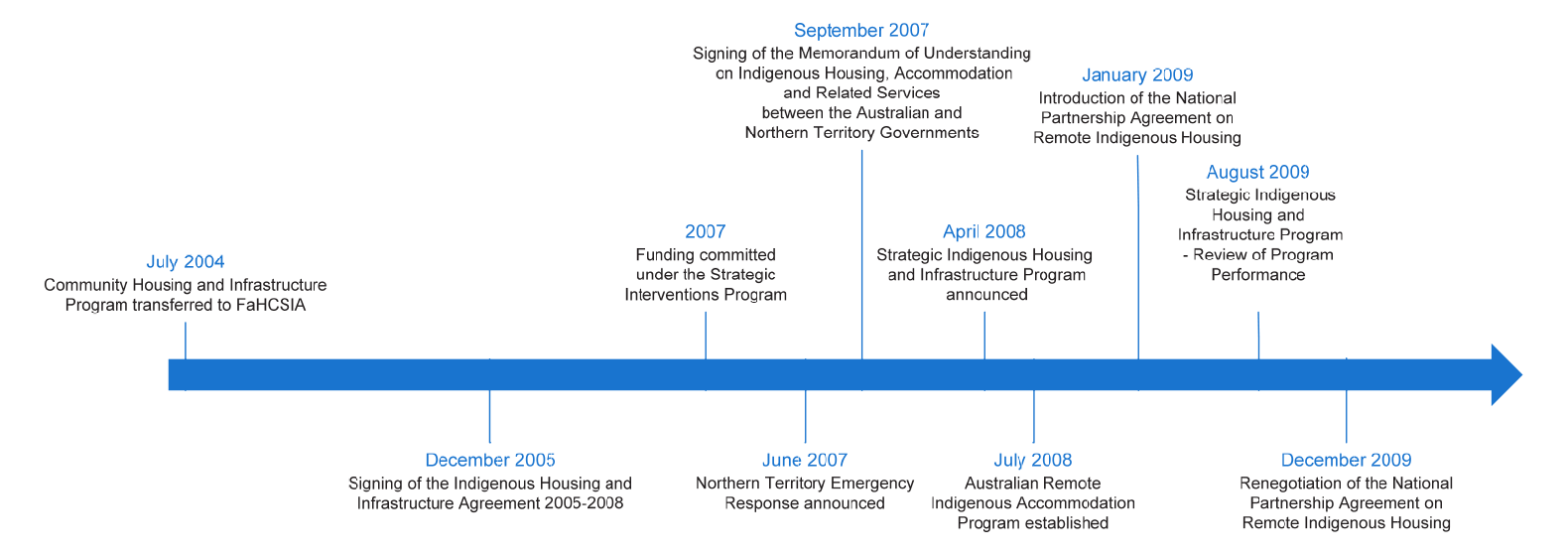

11. Improving Indigenous housing in the Northern Territory has been a policy priority for successive Australian and Northern Territory Governments, although the actual delivery arrangements of these programs since 2008 has been subject to several changes. Figure 1 provides a timeline of recent Indigenous housing programs and events in the Northern Territory, commencing with the Community Housing and Infrastructure Program (CHIP) which was funded by the Australian Government between 1998–99 and 2007. Responsibility for CHIP, a national program, was transferred to the now Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) in July 2004 following the abolition of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. In administering CHIP, the Australian Government provided funding to state and territory governments as well as funding to Indigenous community housing organisations. This funding was used for housing construction, the provision of municipal services and environmental health infrastructure, and property and tenancy management.

Figure S.1: Evolution of Indigenous housing programs in the Northern Territory

Source: Australian National Audit Office analysis of FaHCSIA information.

12. Under CHIP, the Australian and Northern Territory Governments entered into a series of bilateral agreements for the provision of housing and infrastructure in remote Indigenous communities, which, in later periods, evolved into the Northern Territory component of the NPARIH. A number of the features of the current NPARIH delivery arrangements originated in these earlier agreements. For example, in 2007 the Australian and Northern Territory Governments reached agreement to commit over $193 million in funding under the Strategic Interventions Program with the aim of improving housing in remote Indigenous communities. The program made provision for the construction of new houses, the refurbishment of houses, and the development of land servicing and supporting infrastructure.

13. Prior to the development of the Strategic Interventions Program, housing programs in the Northern Territory had been small and were considered by the two governments to be unable to achieve efficiencies or economies of scale, while traditional contracting methods were considered not to be delivering quality outcomes. Program delivery was also considered to be achieving little in the way of employment or training opportunities for local Indigenous people. Accordingly, the Northern Territory and Australian Governments commissioned an external review to advise on an alternative approach to delivering housing construction in the Northern Territory. The review recommended the use of strategic alliance contracting using a panel of alliances; this advice was subsequently accepted by both governments.

14. Shortly after the introduction of the Northern Territory Emergency Response in July 2007,3 the Australian and Northern Territory Governments signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on Indigenous Housing, Accommodation and Related Services which sought to reshape the provision of Indigenous housing in the Northern Territory over the period 2007–08 to 2010–11. Under the MoU, the Australian Government committed $793 million of existing funding from former housing programs, of which $527 million was specifically allocated to improve the quality of existing housing and infrastructure, and to increase the housing stock in remote Indigenous communities. Key reforms introduced in the MoU included: public ownership of houses in remote Indigenous communities, and the introduction of property and tenancy management arrangements that were similar to those in place for public housing in the Northern Territory.

15. Subsequently, in April 2008, the Australian and Northern Territory Governments announced the creation of a 'landmark housing project', which reallocated the funding for housing and infrastructure agreed under the MoU to a new program, the Strategic Indigenous Housing and Infrastructure Program (SIHIP). Funding for housing and infrastructure was then increased from $527 million to $672 million, and the Northern Territory Government agreed to construct 750 new houses, rebuild 230 houses and refurbish 2500 houses by December 2013. All 64 communities and town camps covered by the Northern Territory Emergency Response were to receive funding under the program.

16. Shortly after announcing the development of SIHIP, CHIP was replaced by the Australian Remote Indigenous Accommodation Program (ARIA).4 Like CHIP, ARIA was a national program and was designed to reform Indigenous housing and infrastructure delivery arrangements through bilateral agreements with state and territory governments. As a result, ARIA then became the funding source for SIHIP.

17. SIHIP continued the use of alliance contracting that had earlier been developed under the Strategic Interventions Program and, following the announcement of SIHIP, the Northern Territory Government commenced an open tender process to establish a panel of alliance consortia that would deliver the work. Three alliance consortia were chosen,5 although prior to the release of the first packages of works to be delivered under SIHIP, COAG reached agreement to enter into the NPARIH.

18. The development of the NPARIH, in November 2008, led to further change in the delivery of housing programs in the Northern Territory. Of the $5.5 billion committed nationally to the NPARIH, approximately $3.5 billion was sourced by incorporating existing ARIA funding. This had the effect of subsuming into the NPARIH most pre-existing Indigenous housing programs, including SIHIP. The original SIHIP housing targets, as discussed in paragraph 15, were incorporated into the Northern Territory NPARIH interim targets. These targets were later revised to 934 new, 415 rebuilt and 2500 refurbished houses, to be delivered by the end of 2012–13.

19. The introduction of the NPARIH increased the available funding for remote Indigenous housing in the Northern Territory. As noted in paragraph 5, overall funding of $2 billion is available over ten years to implement the NPARIH in the Northern Territory. This includes $1.7 billion of funding to be provided by the Australian Government through the NPARIH, a $240 million contribution from the Northern Territory Government, and an additional $77 million of Australian Government funding from other sources. Importantly, the alliance contracting arrangements that had been established for SIHIP and its predecessor programs were continued for the delivery of housing construction and housing-related infrastructure.

20. Initial progress against the program’s housing targets was slow and resulted in media coverage during July 2009 suggesting that no homes had been constructed in almost two years of SIHIP’s operation. In response, the then Australian Government Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs announced a review of SIHIP.6 The review involved officers from both the Australian and Northern Territory Governments and was completed in August 2009.7 Overall, the review found that the program had been slow to deliver housing, that there were unresolved leadership and capacity issues, and that substantially greater involvement by the Australian and Northern Territory Governments was required, with strong oversight at the day-to-day operational level.8

21. In response to the review, joint management arrangements were implemented to drive program performance. FaHCSIA formed a new branch based in Darwin with 15 officers, who were assigned to positions within the Northern Territory Government’s program management structure, and both governments became ‘jointly responsible, accountable and in direct control of program management and direction’.9 The joint management arrangements were operational from August 2009.

Request from the Australian Senate

22. On 13 May 2010, the Australian Senate requested the Auditor-General to undertake an ‘investigation of waste and mismanagement of the Strategic Indigenous Housing and Infrastructure Program (SIHIP)’.10 At the time of this request, six new houses had been constructed, 146 houses had been rebuilt or refurbished and the joint management arrangements had been in place for nine months. The thrust of the request was for the Auditor-General to assess whether the:

- Northern Territory Government was managing the contracts for construction and refurbishments in a way that achieved value-for-money;

- Northern Territory Government had appropriate arrangements in place for tenancy management; and

- Australian Government was exercising sufficient supervision over the Northern Territory Government in implementing SIHIP.

23. In response to the Senate request, the ANAO undertook preliminary research to better understand the allocation of responsibilities for the program and to inform the objective, scope and timing of an audit. The Auditor-General Act 1997 currently provides for examination of the operations of Australian Government bodies.11 Accordingly, the ANAO has primarily focused on the program management arrangements, the role of the Australian Government in these arrangements, and the overall progress of the NPARIH in the Northern Territory. Capital works and property and tenancy management implementation arrangements have also been included in the audit, as their effective implementation supports the overall progress of the program.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

24. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the implementation of the NPARIH in the Northern Territory from the perspective of the Australian Government.

25. The audit focused on the administration of the program following the August 2009 review, Strategic Indigenous Housing and Infrastructure Program Review of Program Performance, which increased the Australian Government’s presence and role in the overall management of the program. In some areas, the ANAO covered events which occurred prior to this period to provide context for the discussion or support the audit findings. In order to reach a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO assessed whether:

- program management arrangements put in place following the August 2009 review were effectively supporting the implementation of the NPARIH in the Northern Territory;

- program implementation arrangements were operating effectively; and

- progress against the Northern Territory NPARIH implementation plan targets was being regularly monitored and assessed, and was meeting expectations.

Overall conclusion

26. Increasing the supply and quality of housing in remote Indigenous communities underpins most of the overall targets established under the National Indigenous Reform Agreement to help close the gap on Indigenous disadvantage. The National Indigenous Reform Agreement specifically identifies better housing as having a direct link to: improved life expectancy, better education, improved employment outcomes, and reduced infant mortality. Housing need is high in the Northern Territory and the existing stock of housing and related infrastructure had deteriorated significantly prior to the commencement of the NPARIH. As a result, the scale of construction works under NPARIH exceeds that of previous remote Indigenous housing programs in the Northern Territory. In addition, implementation of the NPARIH is accompanied by activities designed to: reform land tenure arrangements; standardise property and tenancy management arrangements; and increase local Indigenous employment in the construction and maintenance of houses.

27. The initial implementation of the NPARIH in the Northern Territory was slow in terms of delivering the expected housing outputs; at the time of the Senate request in May 2010, just six new houses had been completed and 146 houses had been rebuilt or refurbished. The establishment of the joint management arrangements served to increase the program’s implementation capacity and, as at 30 June 2011, 324 new houses had been constructed and 1592 houses had been rebuilt or refurbished. This exceeds the cumulative annual targets that both governments set following the August 2009 review. Nevertheless, these targets are lower than had been originally planned and agreed in the 2009 Northern Territory NPARIH implementation plan, which contained a target of 383 new houses to be constructed by 30 June 2011.

28. Progress has also been made in other areas. Land tenure arrangements had been agreed in 14 of the 16 communities scheduled to receive major capital works under the program. Standardised tenancy management arrangements have been developed and are being progressively implemented, and Indigenous employment has averaged 34 per cent, with 1137 Indigenous persons employed over the life of the program to 30 June 2011. Between 2007–08 and 2010–11, $810.9 million was spent on remote Indigenous housing in the Northern Territory under the NPARIH and the previous housing program, SIHIP. Of this expenditure, $758.1 million relates to the capital works component of the program, including housing, housing-related infrastructure and program management.

29. The revised program management arrangements developed in August 2009, which involved embedding Australian Government officers into the Northern Territory Government’s program management structure, and establishing a joint management approach, have been effective in improving the implementation of the NPARIH in the Northern Territory. However, in implementing this joint management approach, which is atypical in management arrangements across jurisdictions, less attention has been given to the articulation of the operational role of the Australian Government, and to the development of robust program management systems and processes in the areas of master planning, risk management, budget control and financial reporting. Accordingly, further work is required to clarify the responsibilities and accountabilities of the Australian Government in this arrangement, and to fully develop key financial management and reporting processes to support the effective implementation of the program. Some work has commenced in these areas.

30. The provision of infrastructure such as roads, electricity, water and sewerage is an essential part of providing sustainable public housing and creating healthy and functional homes. Infrastructure funding under the NPARIH was originally planned for new subdivisions and was not intended to address major upgrades of the existing essential services needed to accommodate higher demand from the increased number of houses, or connections from the new subdivisions. As a result, infrastructure requirements are significantly higher than forecast. As a short-term measure to address this shortfall, the governments agreed that housing costs and essential service infrastructure costs would be sourced initially from the NPARIH out-year funding and other Northern Territory Government programs. However, drawing down funds from the NPARIH to pay for infrastructure in the early packages will reduce the funding available in the later years for other packages, unless additional funding for infrastructure is available in future periods. A National Partnership for Remote Indigenous Infrastructure, as envisaged in the National Indigenous Reform Agreement, is still to be considered by government. At the time of the audit it was not clear when this issue will be resolved and/or the level of funding that may be available, leaving questions about whether funding for the full program will be sufficient.

31. Improving the supply and quality of housing is likely to contribute to the achievement of the program’s overall objective of improving living conditions in remote Indigenous communities. However, the combination of a relatively young population, high fertility rates and movement of people to larger communities with better access to government services and economic development opportunities, will influence the extent to which living conditions are improved. It is likely that to achieve the NPARIH average occupancy target for the Northern Territory of 9.3 persons per dwelling, the remote Indigenous housing stock in the Northern Territory will need to be further increased, above the level anticipated in the NPARIH.

32. The ANAO has made three recommendations to support the effective implementation of the NPARIH in the Northern Territory. The first recommendation relates to FaHCSIA clarifying and reflecting in program documentation its ongoing operational role in the management and delivery of the program. The second and third recommendations relate to strengthening the public reporting on progress towards the objectives of the NPARIH and on the financial performance of the program.

Key findings

Program management arrangements

33. The delivery of Indigenous programs generally requires the Australian Government to work with state and territory governments. Improving collaboration and integration between the different levels of government, and their services, has been highlighted as a priority by COAG in the National Indigenous Reform Agreement. National partnership agreements, as the key delivery mechanisms of the National Indigenous Reform Agreement and other reform agreements, were designed to promote collaboration and encourage a shared accountability for outcomes between the different governments involved. At the same time, the design of the agreements has largely maintained the Australian Government’s position as a funder of programs and services that are to be delivered by the state and territory governments. These roles are clearly articulated at a high-level in the NPARIH for all jurisdictions, and applied during the initial stages of implementation in the Northern Territory. However, the subsequent development of joint management arrangements led to responsibility for program delivery, and the overall accountability for results, being shared between FaHCSIA and the Northern Territory Department of Housing, Local Government and Regional Services (DHLGRS).

34. The joint arrangements have given the Australian Government greater visibility over key implementation issues and progress being achieved in all elements of the NPARIH in the Northern Territory. FaHCSIA officers have been embedded within the program management structure of the responsible Northern Territory Government department and, as a result, the Australian Government has ready access to detailed program and package information. This has assisted with managing program progress and risks, influencing outcomes, and strengthening collaboration between the responsible government departments at operational and senior management levels. The joint management arrangements also help to promote a shared understanding and agreement of program objectives and expected outputs. As a result, the arrangements in the Northern Territory, while atypical, can be considered to be a positive approach to integration as they provide a sound base for practical collaboration between jurisdictions, and assist in overcoming many of the boundary issues which can arise in interjurisdictional partnerships.

35. Nevertheless, such joint arrangements can lead to a blurring of responsibilities and accountabilities for program management particularly when, as is the case for NPARIH, the respective roles and responsibilities of the administering departments have not been formally specified at the operational level. Given that the joint management arrangements are a significant change from the high-level allocation of roles and responsibilities under the NPARIH and those generally applying to Australian, state and territory government arrangements, it would be appropriate for the revised program management arrangements to be formally articulated, so that there is concurrence with respect to the management responsibilities and accountabilities of both parties.

36. The Northern Territory NPARIH implementation plan, which is agreed by both governments and is to be reviewed annually, is required to outline the governance arrangements in place for the program. The most current agreed version of this plan dates from March 2009 and pre-dates the implementation of the joint management arrangements. The annual review of the plan, while commenced, is overdue for finalisation. FaCHSIA informed the ANAO in October 2011 that the revised implementation plan had been agreed at officer level and is expected to be finalised during October 2011. The drafts of the annual review and subsequent implementation plans provided to the ANAO did not reflect the changed role of the Australian Government or operation of the joint management arrangements.

37. An important aspect of collaborative implementation is the need to avoid adding to administrative burdens by developing duplicate management systems. Instead, attention should be paid to the early development of joint systems or the modification of existing systems so that they meet the management needs of both administering departments. Implementation of the NPARIH in the Northern Territory formally commenced in March 2009.12 The development of key management processes and information systems to effectively support program management has been slow; at the time of audit fieldwork during late 2010, an up-to-date master plan or schedule, a documented approach to managing risks for the program, and an overarching financial management control framework did not exist.

38. Development of a more systematic approach to the monitoring, reporting and management of the program’s budget and financial information was needed for the longer-term sustainability of the program and to enable the Australian Government, as the main funder, to assure itself that the desired progress was being achieved within the agreed costs. Greater attention began to be paid to improving the planning and management systems from late 2010 and improved program management systems and processes are now being progressively developed and implemented. By early 2011, frameworks for risk management, budget and delivery control had been implemented, and work was underway to develop a master plan and schedule for the program. These initiatives, while delayed, will serve to strengthen the joint management of the program.

Program implementation arrangements

39. The construction, rebuilding and refurbishment of Indigenous housing in remote communities are the key program outputs of the Northern Territory component of the NPARIH and these are being delivered though alliance contracting. Construction works are undertaken as packages, which are generally made up of a combination of new, rebuilt and refurbished houses, serviced land development and civil works. Packages approved to 30 June 2011 are comprised of between two and 110 new houses and 74 to 306 rebuilt or refurbished houses, with the exception of the Southern Region Refurbishments Package. This was a refurbishment-only package covering 27 communities surrounding Alice Springs, and included in excess of 700 refurbishments.

40. The allocation, scoping, negotiation and approval of packages is a major element of the program and can be a lengthy process, taking over 12 months in some cases. To progress housing delivery while packages are being developed and to deliver an immediate benefit to communities, the governments have made use of an approach referred to as early works. These are agreed works which can commence prior to the approval of the package, and were designed to enable the commencement of minor works, such as the set up of construction camps and site works. While early works maintain program momentum, scoping and implementation takes place outside of the agreed package development process and is later integrated into the overall package cost. This can make it more difficult for the departments in negotiating the total package cost, as works are already underway.

41. By 31 December 2010, $130 million in early works had been approved. This has included the construction of workers’ camps, purchase of material, development of new sub-divisions, construction of new houses, and the refurbishment and rebuilding of houses. This was approximately 14 per cent of the value of the approved packages, including housing and infrastructure. The relatively high value of early works highlights the need for the package development process, in particular the timeliness of the process, to be further improved.

42. Maintaining controls over program costs is an essential element of program management. FaHCSIA has sought to benchmark construction costs being incurred in the Northern Territory against other jurisdictions. The resultant benchmarking study concluded that construction costs for new houses in the Northern Territory are higher than the estimated cost of construction in other jurisdictions which face similar climatic and remoteness conditions. However, the study noted that there are significant additional costs being incurred in the Northern Territory due to the large scale and pace of construction. For example, to achieve the program’s interim targets, the alliances are operating concurrently in several remote communities, constructing, in some cases, between 80 and 100 or more houses in each.

43. The ANAO also considered the cost of construction including base construction costs and indirect costs, which include the alliance partners’ profit or fee, contribution to corporate overheads, insurances and contingency. The base construction costs are broadly comparable to general construction industry parameters.13 The alliance partners’ fees and corporate overheads, the main component of management related indirect costs, are agreed during the package development process and are based on the usual fees and corporate overheads that have been charged by the alliance partners for previous comparable projects. Under the pain-share model, the payment of indirect costs is at risk subject to the performance of the alliance partners against pre-agreed targets and key result areas.

Program progress

44. By 30 June 2011, progress had been made in all major areas of program implementation with total program expenditure of $810.9 million, including expenditure under SIHIP, which preceded the NPARIH. The revised housing targets for the program developed in late 2009 have been met or exceeded, with the construction of 324 new houses and the rebuilding or refurbishment of 1592 existing houses by 30 June 2011. This is a positive achievement. However, under the original NPARIH implementation plan, prior to the development of the joint management arrangements, a total of 383 new houses were to have been built by 30 June 2011. Therefore, while implementation has been made more effective, the governments had not made up the progress lost in the initial stages of the program.

45. The number of new houses being constructed in 2011–12 and 2012–13 is expected to increase, which will be necessary if the accelerated interim target of 934 new houses by 30 June 2013 is to be achieved. Packages have been allocated that will allow for the delivery of a total of 677 new houses by 2012–13, but further packages covering an additional 257 new houses will need to be scoped and approved during 2011–12, to allow sufficient time for the additional houses to be constructed. In the remaining years of the program to 30 June 2018, in total, 1132 new houses will need to be constructed and 1323 houses will need to be rebuilt or refurbished, if the Northern Territory Government is to achieve its NPARIH targets of 1456 new houses and 2915 rebuilt or refurbished houses.

46. At this stage of program implementation, FaHCSIA and DHLGRS have focused on publicly reporting the number of new, rebuilt and refurbished houses completed. However, noting the shared responsibility of both governments for the achievement of the NPARIH objectives and outcomes, there would be benefit in publicly reporting on the number of houses that have been handed-over and tenanted, and the time between completion and occupancy, as this would provide a reflection of how well the construction element of the program has been integrated with the tenancy element to assist in achieving the objective of reducing overcrowding. There would also be benefit in reporting on the proportion of houses meeting applicable housing standards, and the level of improvement in housing amenity. This data is available from property and tenancy management information systems, maintained by DHLGRS.

47. Local Indigenous employment is also an area where progress could be better measured and reported. Currently, FaHCSIA and DHLGRS measure and report on total Indigenous employment. To align the measurement and reporting of outcomes in this area with the NPARIH performance indicators and benchmarks, and to support greater public understanding of achievements, a clearer distinction should be drawn between local and total Indigenous employment.

Summary of agency responses

48. A summary of FaHCSIA’s response to the report is reproduced below.

I am pleased that the report acknowledges the progress that has been made by the Australian and Northern Territory Governments in implementing the NPARIH in the Northern Territory. In particular, I would agree that the joint management arrangements have had a positive impact on the delivery of outcomes under the Program since the review of the Strategic Indigenous Housing and Infrastructure Program in August 2009.

FaHCSIA accepts the three recommendations made in the Report and will work in partnership with the Northern Territory Government to implement these recommendations in a timely way.

In responding to the Report, it is appropriate to acknowledge that through the NPARIH the Australian Government is providing $5.5 billion nationally over ten years to help address overcrowding, homelessness and poor housing condition for remote Indigenous communities. Since the commencement of the NPARIH, more than 840 new houses have been completed and a further 3,300 houses have been rebuilt of refurbished nationally.

In the Northern Territory the NPARIH will provide $1.7 billion over 10 years. This is the largest investment ever made in Indigenous housing in the Northern Territory. The program remains on target to build 934 new houses and to complete 2915 rebuilds and refurbishments by the end of June 2013. Already, more than 340 new houses and 1,780 rebuilds and refurbishments have been completed. These works are improving the quality of life for Indigenous families in more than 80 communities and town camps across the Northern Territory.

These works have delivered better housing for thousands of Indigenous Australians in remote locations across Australia. In addition to housing investment, the Australian, State and Northern Territory Governments have also put in place secure land tenure arrangements as a pre-condition for this investment, so that responsibilities are clear. In addition, standard tenancy management arrangements are also being put in place so that rents can be collected and repairs and maintenance carried out.

The recommendations made in the Report will assist the Department to further improve our delivery of this important government initiative. As you are aware, improved housing is central to broader government efforts to help close the gap in outcomes for Indigenous people. I look forward to advising you of our progress against the recommendations in due course.

49. A summary of DHLGRS’ response to the report is reproduced below.

Thank you for the opportunity to respond to your audit report and recommendations relating to the Implementation of the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing (NPARIH) in the Northern Territory dated 16 September 2011.

The Northern Territory Government is committed to improving housing and employment outcomes for Indigenous people in remote communities and is now making significant inroads in the delivery of housing construction and remote public housing reforms supported under NPARIH. Territory Housing manages approximately 4500 remote public houses across 73 remote communities, town camps and community living areas. Construction works are now complete in over 40 communities and continuing in a number of communities and town camps, to date 600 new houses and 1816 rebuilds and refurbishments have been completed or are underway. A target of 20% has been set for Indigenous employment across the Program, with over 30% of the workforce the current Indigenous participation since commencement.

I would like to highlight that since the audit was conducted and report prepared, several of the areas for improvement identified in the audit report have been progressed, including review and implementation of revised governance frameworks and tools, the recruitment of a Quality Manager and development of a formalised handover documentation process.

Structure of management arrangements and governance frameworks demand ongoing consideration for a complex program of the scale and complexity as that now being delivered under NPARIH.

As your audit has found, the joint program management arrangement in place since the August 2009 Review of the Program with my Department and FaHCSIA staff, has led to a sound base for practical collaboration and has assisted in overcoming many of the issues that can arise in inter-jurisdictional partnerships. The post review arrangements have strengthened the role of the Joint Steering Committee with greater direct involvement in the actual program delivery by the Australian Government.

The construction program is delivering on an unprecedented scale and the roll out of remote housing management reforms are now well underway. This progress provides the opportunity to again consider optimum governance structures for the delivery of NPARIH in the Northern Territory, including the option to reduce the operational support in the program currently being provided by FaHCSIA.

Footnotes

[1] Town camps include land leased primarily for residential, community or cultural purposes for Aboriginal people under: the Special Purposes Leases Act of the Northern Territory; or the Crown Lands Act of the Northern Territory.

[2] Implementation Plan for the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing, Between the Commonwealth of Australia and the Northern Territory, 2009, p. 5.

[3] The Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) was announced on 21 June 2007 by the Australian Government. The immediate aims of the NTER measures were to protect children and make communities safe. In the longer term the measures were designed to create a better future for Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory. The NTER contained a wide range of specific measures, including the compulsory acquisition by the Australian Government of five-year leases over 64 Northern Territory communities. While this was not directly an initiative to improve housing, the acquisition was undertaken to enable prompt access for delivery of services, repairs of buildings and the upgrading of infrastructure.

[4] A review of CHIP, completed in 2007, concluded that the housing needs of Indigenous people in remote areas had not been well served by CHIP. The review led to the program’s replacement and the introduction of the ARIA from July 2008.

[5] Both governments and one of the alliance consortia mutually agreed in March 2010 to cease operations.

[6] Although SIHIP was subsumed into the NPARIH, the media and government refer to the program as SIHIP.

[7] SIHIP was also reviewed by the Auditor-General for the Northern Territory. The report titled Strategic Indigenous Housing and Infrastructure Program—June 2010 Report to the Legislative Assembly, was tabled in the Northern Territory Parliament on 8 June 2010.

[8] Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and the Northern Territory Government, Strategic Indigenous Housing and Infrastructure Program—Review of Program Performance, 28 August 2009, Canberra.

[9] ibid., p.32.

[10] Commonwealth of Australia, Parliamentary Debates, Senate Official Hansard, No. 5, 2010, Thursday, 13 May 2010, Canberra, p. 2842.

[11] The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit in Report 419 recommended, among other things, that the Auditor-General’s mandate be extended to allow the Auditor-General, in certain circumstances to audit the performance of recipients of Commonwealth funding. A Private Member’s Bill in support of this recommendation, Auditor-General Amendment Bill 2011, was introduced into the Parliament in early 2011.

[12] The NPARIH was agreed by COAG in December 2008 and the Northern Territory implementation plan was signed by both governments in March 2009.

[13] ANAO compared base construction costs to the Rawlinson’s Construction Guide 2011, using building costs per square metre for a full brick dwelling and a prefabricated dwelling. These dwelling types are not available under the program, but provide an indicative cost for comparison purposes. The approach adopted provides a broad comparison of the base construction cost, but does not include the full range of costs incurred by the program due to location and program-specific parameters, which cannot be easily quantified. For a more accurate comparison a full costing of comparable building components would be required.