Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Implementation of the National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs’ administration of the National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness (NPAH), including monitoring and reporting of progress against the objective and outcomes of the agreement.

Summary

Introduction

1. In Australia it is currently estimated that around 105 000 people are homeless on any given night. Of these people, around 6800 will be sleeping rough on the streets, in parks or other public spaces. The remainder will have varying living arrangements, including living in supported accommodation, with family and friends, in extremely overcrowded accommodation, or in boarding houses.1 To address issues of homelessness, the Australian Government released a White Paper in 2008: The Road Home—A National Approach to Reducing Homelessness (White Paper). This outlined the Australian Government’s commitment to halve homelessness by 2020 and to offer accommodation to all homeless people sleeping rough who need it by 2020.2

2. The complex nature of homelessness was discussed in the White Paper which noted that ‘homelessness is not just the result of too few houses—its causes are many and varied’ including domestic violence, a shortage of affordable housing, unemployment, mental illness, family breakdown, and drug and alcohol abuse.3 The White Paper was developed as a national approach to facilitating the improvement of existing programs and services in addressing and preventing homelessness.

National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness

3. To facilitate a national approach to homelessness, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed in November 2008 to allocate funding of $800 million over four years, 2009–10 to 2012–13, to the National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness (NPAH). Of the $800 million, the Australian Government’s contribution was $400 million. An existing initiative, A Place to Call Home, was also incorporated into the NPAH, increasing the funding available through the agreement to $1.1 billion and bringing the Australian Government’s specific contribution to $550 million.4

4. In entering into the NPAH, COAG emphasised that reducing homelessness ‘…will require all governments to pursue improvements to a wide range of policies, programs and services.’5 Key reforms identified in both the White Paper and the NPAH are directed to increasing the focus on preventing homelessness, improving and expanding services and preventing the recurrence of homelessness. Overall, COAG identified that a better connected service delivery system was necessary for achieving long term sustainable reductions in the number of people who are homeless.6 Recognising the long term challenge of addressing homelessness, the Australian Government noted that the additional funding for homelessness being provided through the NPAH ‘is a down payment on the 12 year reform agenda’.7

5. The NPAH commenced in January 2009 with the primary aim of reducing, preventing and breaking the cycle of homelessness, and increasing the social inclusion of people experiencing homelessness. The four key outcomes set out in the NPAH are that:

- fewer people will become homeless and fewer of these will sleep rough;

- fewer people will become homeless more than once;

- people at risk of experiencing homelessness will maintain or improve connections with their families and communities, and maintain or improve their education, training or employment participation; and

- people at risk of experiencing homelessness will be supported by quality services, with improved access to sustainable housing.8

6. The NPAH seeks to reduce the number of homeless people overall by 7 per cent, Indigenous homelessness by 33 per cent and the number of homeless people sleeping rough by 25 per cent, each by 2013. These performance targets were based on data drawn from the study, Counting the Homeless 2006,9that estimated that 104 676 people were homeless in Australia, of whom 9525 were Indigenous. Of the homeless population it was also estimated that 16 375 people were sleeping rough. Accordingly, a 7 per cent reduction in the number of homeless people in Australia would result in a homeless population of 97 350 people by 2013. Based on this data, to reach the targets set for Indigenous homelessness would require a reduction in their numbers to fewer than 6300 people. Similarly, to reach the target for homeless people sleeping rough would require a reduction in their numbers to fewer than 12 300 people.

7. The role of the Australian Government in the NPAH is principally to provide funding to the state and territory governments for homelessness measures. The Australian Government, through the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA), also supports the state and territory governments in delivering the funded measures, and monitors and reports on progress.10 The state and territory governments, in addition to having the main responsibility for service delivery, are required to make matching funding contributions, and to meet the financial and performance reporting requirements of the NPAH.

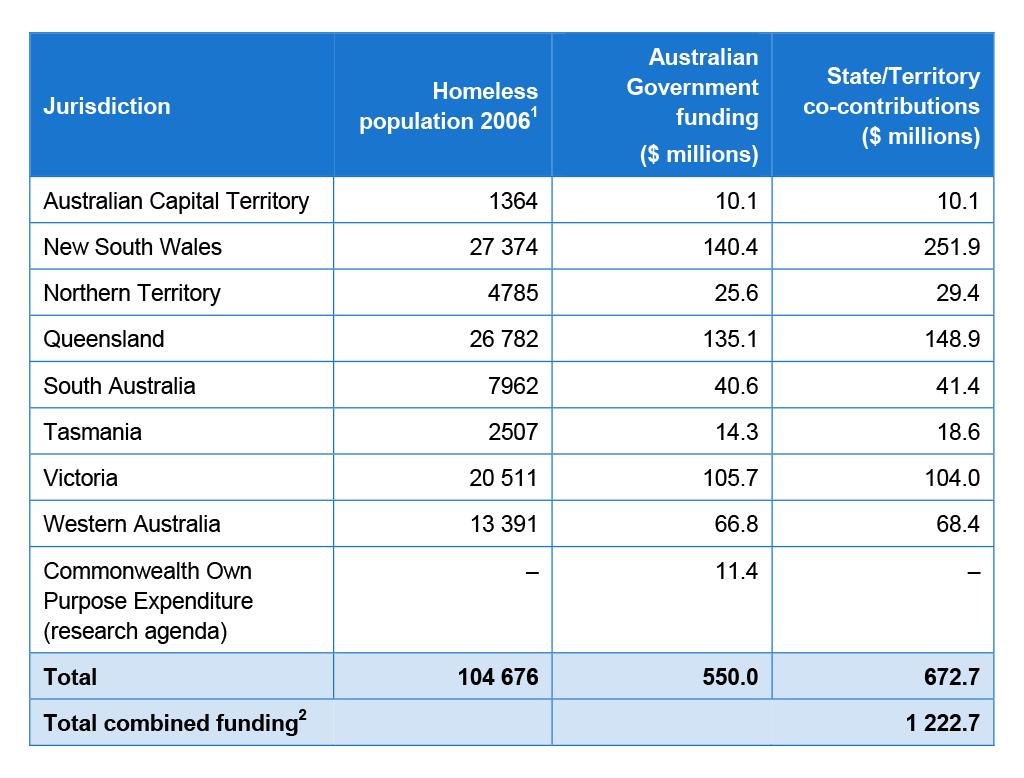

8. Australian Government funding was allocated to the state and territory governments based on an estimate of their respective share of the homeless population in 2006. Table S1 shows the estimated homeless population in each state and territory, the current level of Australian Government funding and the level of funding being contributed by the state and territory governments. The NPAH was initially due to expire on 30 June 2013, but the Australian and state and territory governments agreed in March 2013 to enter into a one-year transitional partnership agreement for 2013–14, while negotiations continue on a new longer-term agreement.

Table S1 Funding arrangements under the NPAH

Source: Australian National Audit Office analysis of COAG data and Counting the Homeless 2006.

Note 1: Based on estimates from Counting the Homeless 2006, which was the definitive source of homelessness data in Australia at that time. The Australian Bureau of Statistics has since estimated that on census night 2006, 89 728 people were homeless, rather than the 104 676 estimated in Counting the Homeless 2006.

Note 2: Total funding available exceeds the $1.1 billion stated in the NPAH as several of the state and territory governments are providing additional funding for a range of homelessness initiatives above those agreed in the NPAH.

Audit objective, scope and methodology

9. The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs’ administration of the NPAH, including monitoring and reporting of progress against the objective and outcomes of the agreement.

10. Three high level criteria were used to conclude against the audit objective. These were whether:

- FaHCSIA’s administrative arrangements supported the effective implementation of the NPAH across all jurisdictions;

- program implementation arrangements are supporting the effective delivery of homelessness services, specifically initiatives directly funded by the Australian Government; and

- progress against the NPAH targets and state and territory implementation plans is being regularly monitored and assessed, and is meeting expectations in relation to improving homelessness.

Audit methodology

11. The Australian Council of Auditors-General agreed in 2010 to increase collaboration, where appropriate, in the conduct of performance audits on topics that have a national dimension. The NPAH was chosen as the topic for the first concurrent audit, and six state and territory Auditors-General have completed or are undertaking similar audits.11

12. A common audit objective and criteria were developed to support the concurrent audit approach. The objective of the state and territory jurisdiction audits was to examine whether or not the relevant government agencies were meeting their obligations under the NPAH, and whether or not the NPAH was making a difference for homeless people. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), in preparing this report, has considered the findings of the reports completed by the state and territory Auditors-General.12

Overall conclusion

13. In agreeing the NPAH in 2008 the Australian, state and territory governments made a substantial financial commitment to preventing, reducing and breaking the cycle of homelessness. The governments have committed over $1.1 billion to new and expanded initiatives, but progress is not leading to the achievement of the expected 7 per cent reduction in homelessness by 1 July 2013. Between 2006 and 2011 the number of homeless people, rather than declining, increased by 17 per cent from 89 728 to 105 237 people.13 While the NPAH target was to be reached by 1 July 2013, on the basis of this trend, reaching the target will be extremely challenging and is unlikely to be achieved.14

14. Through the implementation of the NPAH, over 180 new or expanded homelessness initiatives have been funded to provide a range of different services. Demand for services is high and during 2011–12, 229 247 people, or the equivalent of around 1 in 100 Australians, made contact with specialist homelessness services.15 Specialist homelessness services also provided over 7 million nights of accommodation during 2011–12.16 However, there is limited information prepared by FaHCSIA, as the department with Australian Government policy responsibility, to assess the extent to which the approach of funding a large set of separate initiatives supports the achievement of the NPAH outcomes and service delivery reforms envisaged by COAG. The available reports of the state and territory Auditors-General have noted that there was evidence of better consultation and engagement across the homelessness sector, but that it was not clear how changes in the service delivery system were assisting the state and territory governments in reducing homelessness by the levels agreed in the NPAH. It was also noted in the reports that without a strong focus on evaluating the effectiveness of individual initiatives, it was not clear whether some of the funded initiatives had been more effective than others in reducing and breaking the cycle of homelessness.

15. At an administrative level, FaHCSIA has generally fulfilled its responsibilities under the NPAH in line with the expectations established through the Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations. The department’s management arrangements also provided a sound basis to support the initial implementation phase of the NPAH across jurisdictions. This included engaging with and supporting the responsible Australian Government Minister17 and working within the roles and responsibilities established by the NPAH to negotiate the state and territory implementation plans.

16. FaHCSIA assessed the state and territory implementation plans and negotiated with the state and territory governments over the initiatives funded. However, this process could have been better supported by the department focusing on whether the proposed initiatives, mix of services, and reforms of the homelessness service delivery system would most effectively contribute to the achievement of the outcomes of the NPAH. The implementation plans give attention to the implementation of funded initiatives, but generally lack a clear focus on the achievement and measurement of outcomes, sustainability of outcomes and the quality of homelessness services.

17. In respect of monitoring and reporting on progress, FaHCSIA has largely fulfilled its ongoing role, although there are some significant limitations deriving from the administrative arrangements of the NPAH, which constrain the value of this reporting in informing the department about the effectiveness of measures being implemented to reduce homelessness. To monitor progress in the implementation of the NPAH and the funded initiatives, FaHCSIA put in place a structured performance framework under which each state and territory government was required to provide information on performance as agreed in their implementation plans. Annual reporting requirements have focused on measuring activity at an individual initiative level, rather than progress towards the outcomes of preventing, reducing and breaking the cycle of homelessness. The absence of outcomes-based reporting limits FaHCSIA’s ability to make meaningful assessments of overall progress within each jurisdiction, or on a national basis. In addition, FaHCSIA receives only limited information on the extent to which the reforms sought through the NPAH are proving effective. Further, the state and territory governments are not required to report financial information to FaHCSIA, limiting the department’s ability to obtain assurance that the jurisdictions are meeting their financial commitments under the NPAH.

18. The NPAH was one of the early national partnerships to be agreed, and its implementation has highlighted a number of policy and implementation issues for further consideration by the Australian Government. In support of the negotiation of future funding arrangements for homelessness, there would be benefit in FaHCSIA providing advice to the Australian Government which addresses the availability of timely data sources to support assessment of the agreement’s outcomes; the design of the performance framework, including measures relating to reform of the homelessness service delivery system; and the strengthening of financial management and reporting requirements, as explained hereunder.

- Measuring the overall impact of the NPAH relies upon census data prepared by the ABS. Although the NPAH benchmark targets were to be met by 2013, the next census will not take place until 2016 and, as a consequence, the key headline measures relating to the number of Australians who are homeless cannot be effectively measured over the life of the current agreement. When census data is to be used to set performance baselines and benchmark targets, the design of the underlying funding arrangement, should, to the extent feasible, be either aligned to the census cycle, or reliable proxy measures.

- The NPAH was aiming to build ‘more connected, integrated and responsive services which achieve sustainable housing and economic and social participation of those at risk of homelessness’.18 Where significant reforms to service delivery arrangements are being sought, the performance measurement and reporting framework should be designed to measure the implementation of the reforms as well as the delivery of funded activities and their impact.

- Payments made through the NPAH are not currently linked to the achievement of agreed milestones, as is the case in some other agreements. Creating a payment structure that is more closely related to performance would enhance public accountability in respect of progress being made towards the outcomes sought by governments, and would be worthy of further consideration in any future agreement.

- The NPAH is based on a shared funding model, but the state and territory governments are not required to report financial information to FaHCSIA. Where a co-contribution approach forms part of any future funding arrangement for homelessness, it is not unreasonable to expect financial information to be reported to FaHCSIA by the state and territory governments, to enable the department to provide assurance to the Minister over the level of contributions made.

19. Consideration should also be given to the issues raised in the available audit reports from the state and territory Auditors-General on the implementation of the NPAH.

20. The issues raised above in paragraph 18 are matters which may require broader consideration by the Australian Government in respect of other future funding arrangements that operate at a national level. In this context, there is scope to place more emphasis on performance reporting arrangements which assist in identifying those measures or initiatives employed by the state and territory governments that make a significant difference to the achievement of better outcomes, consistent with the objectives agreed by governments.

21. The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at strengthening the administrative arrangements for potential future funding arrangements involving the delivery of services by the state and territory governments.

Key findings by chapter

Implementation

22. FaHCSIA is the lead Australian Government agency responsible for overall implementation of the NPAH in collaboration with the state and territory governments. At the commencement of the NPAH, FaHCSIA gave consideration to key aspects of program implementation and administration. It developed processes for the negotiation and approval of the state and territory implementation plans in line with the requirements and expectations of the NPAH. This included FaHCSIA providing feedback to the respective state or territory departments for their consideration. However, to effectively influence reform of the homelessness sector and achievement of the NPAH outcomes, FaHCSIA could have given greater attention to assessing how the more than 180 proposed initiatives would collectively contribute to preventing, reducing and breaking the cycle of homelessness in order to achieve the 7 per cent reduction in homelessness envisaged by COAG. The implementation plans give attention to the implementation of funded initiatives, but generally lacked a clear focus on the achievement, measurement and sustainability of outcomes, and the quality of homelessness services.

23. NPAH payments are made by the Australian Government to the state and territory governments on a monthly basis in accordance with the agreed payment schedule. These payments are not linked to the achievement of specific milestone or performance benchmarks. However, an annual review of overall progress by the state and territories is undertaken by FaHCSIA to enable the Minister to make a determination to continue the monthly payments in accordance with the requirements of the Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations and related federal finances circulars. Due to the timing of the annual reporting process, there is a limited relationship between actual progress and the determination by the Minister, as payments have already been made for the period to which the annual reports on progress relate, and in most years five months of payments will generally be made before the review and determination process is completed. This is in line with the agreement reached by COAG for the NPAH, however, it does not support early feedback on program progress.

Performance monitoring and reporting

24. The NPAH includes a performance framework comprising an objective, outcomes, performance indicators, baselines and benchmark targets. This framework has been replicated in the state and territory implementation plans. However, there is limited alignment between the NPAH outcomes and performance indicators, and the state and territory governments’ reports focus on the delivery of individual initiatives rather than overall progress. This inhibits FaHCSIA’s ability to effectively assess and report nationally on the outcomes of the NPAH. A better alignment is critical to ascertain whether the reforms being sought by the Australian Government and the underlying approaches to preventing, reducing and breaking the cycle of homelessness are effective strategies.

25. The NPAH’s performance reporting framework has been examined in several Australian Government or cross-jurisdictional reviews. The reviews have identified a range of limitations including the inability to clearly link the NPAH outputs and outcomes, and the inability to measure changes in homelessness over the life of the agreement.19 In addition, the COAG Reform Council noted in its reports about the National Affordable Housing Agreement and supporting national partnerships, that it has been unable to report on the NPAH due to limitations in the available performance information, and the inability to link activity reported by the state and territory governments to the outcomes and objectives of the national agreement. Changes were made to the performance framework in 2012 following the mid-term review of the agreement, but the changes were not sufficiently significant to address the original design limitations of the framework, or to better position FaHCSIA to measure overall progress and the impact of the NPAH.

26. The NPAH does not make provision for state and territory financial information to be provided to FaHCSIA. Consequently, FaHCSIA is not able to substantiate whether the state and territory governments are meeting their co‑contribution commitments as agreed through the NPAH. This information is reported to the Australian Government Treasury for provision to the Standing Council on Federal Financial Relations, but the Treasury has not been authorised to release this information to administering departments, even where the departments have overall policy responsibility for the agreement. This limits the view that the departments with policy responsibility would normally be expected to have over the performance of the program. There would be benefit, from the Australian Government perspective, in reviewing this approach.

27. Recent trends, as evidenced through changes between the 2006 and 2011 Censuses of Population and Housing, indicate that homelessness has increased. The NPAH’s performance target of a 7 per cent reduction in homelessness by 2013 was set against a baseline of 104 676 people, which was an estimate of homelessness in Australia at the time the NPAH was agreed.20 The 2011 census estimated that the homeless population had reached 105 237 people, which is a slight increase over the 2006 estimates used in developing the NPAH. However, the ABS has also estimated that in 2006 the homeless population was in fact much lower than previously estimated, at 89 728 people. As a result, there has been an increase of 17 per cent in the number of homeless people since 2006, on the basis of the census data that is now available. During this period the rate of homelessness (the number of homeless people per 10 000 of the population) also increased but at a proportionally lower rate of 8 per cent.21

28. Based on ABS estimates, the number of Indigenous people who were homeless rose by around 3 per cent between 2006 and 2011 against the NPAH benchmark target of a reduction of 33 per cent.22 Census data also shows that Indigenous people are significantly overrepresented in the homeless population at a rate of around 1 in 20 Indigenous people compared to around 1 in 200 people for the population as a whole.

29. The other key benchmark target of the NPAH relates to reducing the number of homeless people sleeping rough by 25 per cent. Although still short of expectations, progress against this target has been more positive with around a 6 per cent reduction in the number of homeless people sleeping rough, according to ABS estimates.23

30. To achieve its overall goal of halving homelessness by 2020, the Australian Government recognised that a long term commitment would be required and that the funding provided through the NPAH was a ‘down payment’. In support of developing effective approaches to addressing homelessness over this long timeframe, there would be benefit during 2013–14 in FaHCSIA evaluating the outcomes achieved under the NPAH to provide insight into how well the agreement is assisting the Australian, state and territory government in meeting the homelessness targets set by COAG. This information could be used to inform the negotiation of any longer-term funding arrangement for homelessness.

31. The NPAH was one of the early national partnerships to be agreed and its implementation has highlighted a number of policy and implementation issues. In support of the negotiation of future funding arrangements for homelessness, there would be benefit in FaHCSIA providing advice to the Australian Government, for its consideration, on key aspects of the design of potential funding arrangements, including: aligning the funding arrangements to the availability of the key data through which performance will be assessed; designing the performance framework in such a way that it supports assessment of service delivery reform and program outcomes; creating payment structures that are more closely related to performance; and finally, requiring the state and territory governments to provide financial information to the responsible policy department, particularly where a co-contribution requirement is included. These issues are also matters which may require broader consideration by the Australian Government in respect of other future funding arrangements that operate at a national level.

Overview of the concurrent audit reports

32. The reports prepared by the Western Australian, Victorian, Queensland, Tasmanian and Northern Territory Auditors-General on implementation of the NPAH in their jurisdictions have identified a number of thematic issues. One of the common issues was that despite the implementation of a range of homelessness initiatives, the expected reduction in homelessness will not be achieved in any of these state and territory jurisdictions. This is coupled with a reported lack of focus on measuring the outcomes being achieved or evaluation of the effectiveness of the funded initiatives. Measuring and reporting on activity or outputs, provides information about the services that are being delivered, but this approach to reporting does not provide an insight into the quality, timeliness or longer–term impact of the services.

33. At an administrative level, the Auditors-General identified that the respective governments were generally meeting their performance and financial reporting commitments under the NPAH, but the validity of the reported information could not be established in all instances. While it was not a requirement of the NPAH, reporting to state Parliaments was identified as being inadequate, limiting the level of accountability being provided to the community. There were also variances in the effectiveness of the management arrangements established in each jurisdiction to coordinate and drive activities.

34. The NPAH was designed to promote reform of the homelessness service delivery system with the aim of developing better connected and more integrated services. The Auditors-General have observed that in some cases the additional funding under the NPAH has been used to fund business as usual activities, while in others a greater focus was given to reform of the homelessness service delivery system, which improved the level of interaction between services. To sustain changes in the service delivery system and future service delivery, the need for greater certainty of future funding was also a matter raised in some of the reports by the Auditors-General.

Summary of agency response

35. FaHCSIA welcomes the ANAO report as an informative and constructive appraisal of the implementation of the National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness. FaHCSIA notes the findings of the report and accepts the Recommendation.

36. FaHCSIA particularly notes that changes to the payment structure and performance framework of any longer term homelessness Agreement would allow for improved transparency and accountability of how the Agreement contributes to meeting the ambitious Homelessness White Paper targets. FaHCSIA is considering ways of applying the recommendations of this report and lessons learned to any longer term homelessness Agreement, while also following the guidelines stipulated as part of the Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations.

Recommendations

The ANAO has made one recommendation to strengthen the design of future funding arrangements involving the delivery of services by the state and territory governments, in particular homelessness services.

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 3.47 |

To better support the administration of any future funding arrangements for homelessness which involve the delivery of services by the state and territory governments, the ANAO recommends that FaHCSIA explore relevant options and provide advice to the Australian Government in respect of:

|

| FaHCSIA’s response: Agreed. |

Footnotes

[1] Based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimates of homelessness in Australia—2049.0–Census of Population and Housing: Estimating homelessness, 2011, p. 2, released 12 November 2012.

[2] Australian Government, The Road Home—A National Approach to Reducing Homelessness, Canberra, 2008, p. viii.

The definition of homelessness used by the Australian Government prior to the development of a statistical definition of homelessness in 2012, categorises sleeping rough as those people who have no conventional accommodation and consequently live on the streets, in deserted buildings, parks or other public spaces.

[3] Ibid., p. iii.

[4] COAG also entered into the National Partnership Agreement on Social Housing. This was a two year agreement aimed at increasing the supply of social housing, providing approximately 1600 to 2100 additional dwellings by 2009-10, and providing opportunities to grow the not-for-profit housing sector.

[5] Council of Australian Governments, National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness, Canberra, 2009, p. 3.

[6] The service delivery system includes the wide range of services provided by government agencies to address aspects of homelessness and to support homeless people. These services are often delivered by third party service providers under funding arrangements with government. Such services can include crisis accommodation, domestic violence prevention, mental health, and family and financial counselling.

[7] Australian Government, The Road Home—A National Approach to Reducing Homelessness, Canberra, 2008, p. iii.

[8] Council of Australian Governments, National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness, Canberra, 2009, p. 5.

[9] Counting the Homeless 2006 was a cooperative effort between two universities and several Australia Government agencies and was the definitive source of homelessness data in Australia at the time the NPAH was agreed. The ABS has since released estimates of homeless based on the 2006 and 2011 Censuses of Population and Housing.

[10] The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs is the lead Australian Government agency responsible for homelessness policy and overall implementation of the NPAH.

[11] Audits of the NPAH have been or are being undertaken in the Australian Capital Territory, the Northern Territory, Queensland, Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia. Reports of the audits have been or will be tabled in the relevant state and territory Parliaments.

[12] As of 16 April 2013, the Auditors-General of Western Australia, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania and the Northern Territory had tabled their reports.

[13] Based on the ABS estimates of homelessness in Australia—2049.0–Census of Population and Housing: Estimating homelessness, 2011, p. 2, released 12 November 2012.

[14] In considering this trend it is important to note that the NPAH commenced more than halfway through the census cycle and that more time may be required for the funded initiatives to begin to reduce the numbers of homeless people.

[15] For further information see Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Specialist Homelessness Services 2011-12, 2012, Canberra, p. 7.

[16] ibid. p. 7.

[17] Since 2007, the Ministerial role of housing and homelessness has been referred to variously as the Minister for Housing, the Minister for Social Housing and Homelessness, and the Minister for Housing and Homelessness. Any subsequent references to the Minister for Housing and Homelessness (the Minister) refer collectively to these roles.

[18] Council of Australian Governments, National Partnership Agreement on Homelessness, Canberra, 2009, p. 6.

[19] The reviews include an early assessment of progress undertaken by the COAG Reform Council, reported to government in 2010; the Heads of Treasuries’ Review of National Agreements, National Partnerships and Implementation Plans under the Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations completed in 2010; and a mid-term review of the NPAH completed by the cross-jurisdictional Homelessness Working Group, undertaken in 2011-12.

[20] The NPAH was based on estimates of homelessness in Australia reflected in the publication Counting the Homeless 2006. Counting the Homeless 2006 while released by the ABS and based on the 2006 Census of Population and Housing and other data sources was not an official count of homelessness in Australia. The ABS released official estimates of homelessness in Australia based on the 2001, 2006 and 2011 censuses during 2012.

[21] ABS estimates indicate that the rate of homeless increased from 45.2 people per 10 000 of the population in 2006 to 48.9 people per 10 000 of the population in 2011.

[22] The ABS has estimated that the number of Indigenous homeless people increased from 25 950 people in 2006 to 26 744 people in 2011. This data is not comparable with data drawn from the Counting the Homeless 2006, as at that time the Indigenous homeless population was estimated to be around 9500 people.

[23] The ABS has estimated that 7200 homeless people were sleeping rough in 2006, which decreased to around 6800 homeless people in 2011. In Counting the Homeless 2006, it was estimated that around 16 300 homeless people were sleeping rough.