Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Implementation of Audit Recommendations

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s monitoring and implementation of both ANAO performance audit and internal audit recommendations.

Summary

Introduction

1. Performance audits conducted by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO)—often referred to as ‘external’ audits—involve the independent and objective assessment of the administration of Australian Government entities’ programs, policies, projects and activities, and highlight opportunities for improvement. Audits initiated by entities using resources under their control—known as ‘internal’ audits—fulfil a complementary role, providing assurance to entity management on the effectiveness of the internal control environment and identifying opportunities for enhancing entity administration.

2. Performance audits play an important role in stimulating improvements in the administration and management of public sector entities as well as providing independent assurance to Parliament on the administration of programs. Recommendations in audit reports highlight actions that are expected to improve entity performance when implemented and generally address risks to the successful delivery of outcomes. The appropriate and timely implementation of recommendations that have been agreed by entity management is an important part of realising the full benefit of an audit.1

3. Primary responsibility for implementing agreed audit recommendations generally lies with senior managers in the program or business area of the entity that was subject to the audit. Successful implementation of audit recommendations requires strong senior management oversight and implementation planning to set clear responsibilities and timeframes for addressing the required action.2 Implementation planning should involve key stakeholders, including the internal audit function.

4. Audit committees, through their position in an entity’s governance framework, also have a role in monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations. While audit committees do not undertake management responsibilities and are not a substitute for management controls, they have an important role in assisting the accountable authority3 in ensuring that the anticipated benefits of audit reports are realised, through the effective and timely implementation of audit recommendations. The audit committee’s role in maintaining oversight of implementation is supported by the entity’s internal audit function. One of the key roles of internal audit is to support the audit committee by monitoring and providing advice on management’s progress in implementing recommendations.

5. In recent years, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) and other parliamentary committees have expressed interest in the performance of Australian Government agencies in relation to implementing audit recommendations. In addition, responses provided as part of the ANAO’s 2011 Survey of Parliamentarians indicated that periodic audits of the implementation of performance audit recommendations would be of benefit.4 In response to this feedback, the ANAO has conducted a program of performance audits on the implementation of audit recommendations, of which this report is one.5

Audit objective, scope and criteria

6. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s monitoring and implementation of both ANAO performance audit and internal audit recommendations. The ANAO examined a sample of 220 ANAO performance audit and internal audit recommendations to assess the timeliness of Health’s implementation of the recommendations. A subset of seven closed ANAO performance audit recommendations and seven closed internal audit recommendations was also analysed in detail to assess the adequacy of the implementation of the recommendations.

7. To conclude against the audit objective, the ANAO examined whether the Department of Health’s arrangements for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations:

- provided adequate visibility and assurance to departmental management regarding the status of audit recommendations, with appropriate involvement by the Audit Committee and internal audit function; and

- facilitated appropriate implementation of ANAO, and internal audit, recommendations by agency management in a timely manner.

8. The ANAO also compared the department’s overall performance in implementing recommendations against seven other departments that have been the subject of recent ANAO audits on the implementation of audit recommendations.6

Overall conclusion

9. It is an entity’s responsibility to manage the implementation of audit recommendations to which it has agreed, including determining an appropriate strategy to help achieve timely and effective implementation. The successful implementation of audit recommendations requires senior management oversight, implementation approaches that set clear actions and timeframes, and effective monitoring.

10. Of the 14 audit recommendations examined in detail as part of this audit, nine were assessed by the ANAO as being adequately implemented by the Department of Health. The other five audit recommendations were assessed as being partially implemented despite being closed on the department’s audit recommendation monitoring system. Audit recommendations assessed as partially implemented generally showed that the implementation either: fell short of the intent of the recommendation; only addressed some of the risks to which the recommendation was directed; or was ongoing at the time of this audit. As these recommendations had been formally closed on the department’s monitoring system, the Audit Committee no longer had visibility over them. The internal audit function7 and the department’s Audit Committee generally relied on advice from responsible Division Heads that recommendations had been implemented and therefore no longer needed to be monitored by the Audit Committee. This highlights a limitation with the department’s current process, which can permit the closure of audit recommendations as complete without sufficient assurance of implementation. While it is impractical to undertake detailed assessments of the implementation of all recommendations, the internal audit function should seek appropriate assurance from responsible Divisions to support requests for the closure of audit recommendations, and consider the benefit of sign-off at a more senior level for significant recommendations. The ANAO has observed from previous audits that, where there was sign-off by the responsible departmental Deputy Secretary, a higher proportion of recommendations had been adequately implemented.8

11. The ANAO’s recent examination of the implementation of audit recommendations in seven other Australian Government departments9 indicated that across these departments, 65 per cent of recommendations were assessed by the ANAO as adequately implemented, while the remainder were assessed as having being implemented to varying degrees. The Department of Health’s result of 64 per cent for adequate implementation is comparable to the combined average of the seven departments.

12. The ANAO examined the timeliness of Health’s implementation of a sample of audit recommendations from 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2012, which involved a review of 220 recommendations (comprising 35 ANAO audit recommendations and 185 internal audit recommendations). The results show that, on average, the ANAO and internal audit recommendations took 379 days to close, with the ANAO recommendations taking 160 days longer to close than internal audit recommendations. Ninety-one per cent of audit recommendations were closed within two years, most after their original estimated implementation date. For many recommendations, if implementation is not progressed promptly, and the identified risks remain untreated, the full value of agreed recommendations is not being achieved.

13. Under Health’s current monitoring and reporting process, responsible Divisions are not required to formally seek an extension to the implementation dates for audit recommendations. The Audit Committee only becomes aware of any change to implementation dates when Divisions report on progress twice a year, with an attendant risk of ‘drift’ in the timeliness of implementation. To address this risk of drift, the department should strengthen its monitoring and reporting system by requiring Divisions to formally apply for any change to an agreed implementation date.

14. A better practice approach to the implementation of significant audit recommendations features the development of implementation plans in consultation with the department’s internal audit function and audit committee, if appropriate, that set clear responsibilities and timeframes for addressing the required action.10 While the department’s internal audit function (the Audit and Fraud Control Branch) consults closely with responsible Divisions in the development of implementation plans for internal audit recommendations, there is no consultation with Divisions in the development of implementation plans for ANAO recommendations. The lack of engagement by the internal audit function in the development of implementation plans for ANAO recommendations may, in part, explain why 86 per cent of internal audit recommendations sampled were adequately implemented compared to only 43 per cent of ANAO recommendations. Moreover, it takes five months longer on average to implement an ANAO recommendation than internal audit recommendations. Improved consultation with Divisions by the Audit and Fraud Control Branch would help improve the quality and consistency of implementation plans for ANAO audit recommendations, and may contribute to improved implementation of ANAO recommendations.11

15. Health’s system and procedures for monitoring and reporting on the implementation of recommendations provides the Audit Committee with sufficient visibility over reported action and significant implementation delays. Recently, the Audit Committee has been provided with more detailed information on the audit recommendations that have been classified as ‘significant’, allowing members to focus on implementation progress of the audit recommendations that are intended to address significant risk and exposure to the department. The ANAO’s examination of Audit Committee meeting minutes indicated that the Committee now actively monitors implementation of significant audit recommendations. The Committee has also requested the attendance of representatives from responsible Divisions to explain difficulties in implementation, on a number of occasions.

16. ANAO and internal performance audits play an important role in identifying risks to the successful achievement of entity outcomes, and highlighting actions to address those risks, through audit recommendations. The effective and timely implementation of audit recommendations is an important part of realising the full benefit of an audit. While the Department of Health’s system and procedures for monitoring and reporting on the implementation of recommendations provides the internal audit function and Audit Committee with reasonable visibility of progress, there are elements that could be more aligned with better practice, by introducing more structured processes for extending implementation deadlines and closing recommendations. The key issue highlighted by this audit, that requires further attention by the department, concerns the need to obtain an appropriate level of assurance in respect to the completion of actions taken to implement agreed recommendations. To avoid the risk of closing recommendations prematurely, the department should seek appropriate assurance and sign-off from responsible Divisions, and in the case of significant recommendations, consider the benefit of sign-off at the Deputy Secretary level.

17. The ANAO has made one recommendation focusing on the introduction of measures to improve Health’s internal processes for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations, including: the recording of expected deliverables and timeframes; requiring formal requests for extensions to implementation dates; seeking appropriate assurance of implementation before closing recommendations; and recording the basis of decisions to close audit recommendations as implemented.

Key findings by chapter

Governance Arrangements (Chapter 2)

18. It is an entity’s responsibility to manage the implementation of audit recommendations to which it has agreed. Primary responsibility for implementing audit recommendations within Health lies with senior managers in the program area or business units subject to the audit. While the implementation of audit recommendations is a management responsibility, the internal audit function is well placed to monitor the progress of implementation. Effective monitoring requires a system that accurately tracks progress and records the actions of program managers responsible for progressing action against timeframes.

19. The department’s Audit and Fraud Control Branch discharges the internal audit function. The Branch has a well-established process for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations. The Branch liaises with relevant Divisions for updates on the implementation of audit recommendations, which provide a basis for reporting to the Audit Committee twice a year. A system of iterative spreadsheets and emailed documents is used to prepare key information for the Audit Committee on progress made by program areas in implementing audit recommendations. While the information is relevant and well-targeted, the use of this system has an inherent risk in terms of potential data loss from the manual transfer of information from one spreadsheet to another.12 Moreover, the department’s current system is not well suited to readily tracking progress in implementation over the life of a recommendation. To track the course of implementation of a recommendation often requires accessing multiple spreadsheets, written documents and hard copy files.

20. The ANAO also noted that limited supporting information was provided by program areas to support the closure of recommendations as implemented. The Audit and Fraud Control Branch and Audit Committee generally rely on advice provided by the First Assistant Secretaries (Division Heads) from the program areas responsible for implementation that recommendations have been implemented. The ANAO identified a number of audit recommendations that have not been adequately implemented despite being closed in the audit recommendation monitoring system. There are benefits in requiring formal sign-off by senior management prior to the closure of recommendations. As highlighted in ANAO Audit Report No.53 2012–13 Agencies’ Implementation of Performance Audit Recommendations, for those entities that required senior management sign-off at the Deputy Secretary level, the ANAO observed a higher proportion of recommendations had been adequately implemented.13

21. There is no formal process through which Divisions seek extensions to the implementation timeframes for recommendations, and the six monthly update to the Audit Committee schedules is when a possible delay to implementation is first identified. In many cases, Divisions revised their estimated implementation dates numerous times before recommendations were completed. A review of Audit Committee minutes by the ANAO (for the period 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2012) indicates that the Audit Committee has expressed concerns on a number of occasions regarding overdue recommendations and inadequate implementation schedules, particularly where the corrective action outlined by the responsible Division did not justify the estimated implementation date.14 The Audit Committee requested follow-up action on specific recommendations on at least eight occasions over the three year period examined by the ANAO and expressed concern over estimated timeframes on at least six occasions. To avoid the risk of drift in the timeliness of implementation, responsible Divisions should formally request extensions to agreed implementation timeframes for audit recommendations.

Implementation of Audit Recommendations (Chapter 3)

22. In order to derive the intended benefit, audit recommendations should be effectively implemented in a timely manner. The ANAO assessed a sample of seven ANAO audit recommendations and seven internal audit recommendations that had been closed in the department’s monitoring system to determine whether they had been adequately implemented. The ANAO’s review found the department’s implementation of agreed ANAO and internal audit recommendations was variable, indicating shortcomings in implementation approaches.

23. The ANAO identified five audit recommendations out of 14 (or 36 per cent) that had not been adequately implemented despite being recorded as closed on the department’s monitoring system. As these recommendations had been formally closed on the department’s monitoring system, the Audit Committee no longer had visibility over them. The Audit Committee generally relied on advice from Division Heads that recommendations had been implemented and therefore no longer needed to be monitored by the Audit Committee. To avoid the premature closure of audit recommendations as implemented, the internal audit function should obtain an appropriate level of assurance from responsible Divisions for all requests to close recommendations, and should record the basis for all decisions to close audit recommendations as implemented.

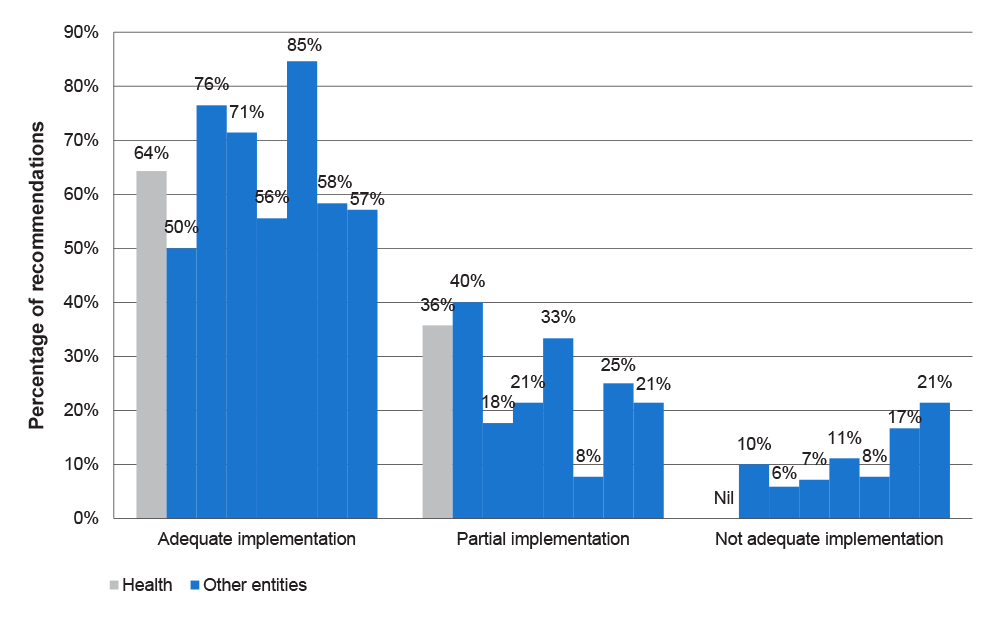

24. Over the past two years, the ANAO has conducted a program of audits on the implementation of audit recommendations by seven Australian Government departments. A comparison of the rate of implementation of audit recommendations by the Department of Health against the seven other selected departments indicated that:

- an average of 65 per cent of recommendations were assessed as adequately implemented across the seven departments, as compared to 64 per cent in Health;

- an average of 22 per cent of recommendations were assessed as partially implemented across the seven departments, as compared to 36 per cent in Health; and

- an average of 13 per cent of recommendations were assessed as not adequately implemented across the seven departments, as compared to Health which had no recommendations in this category.

25. The ANAO also considered the timeliness of Health’s implementation of audit recommendations, through the analysis of a sample of 220 recommendations (comprising 35 ANAO and 185 internal audit recommendations). The ANAO’s analysis identified issues with the timeliness of the department’s implementation of recommendations, particularly ANAO recommendations. The ANAO found that, on average, the ANAO recommendations sampled took 514 days to close, while the internal audit recommendations took, on average, 354 days. These implementation timeframes, on average, exceeded the department’s estimated timeframes by 188 days.

Summary of entity response

26. The Department of Health provided the following summary comments to the audit report.

The findings of the audit have been of value in the further enhancement of Departmental processes to improve performance in the delivery of Health outcomes. The Department of Health agrees with the audit recommendation.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.38 |

To improve the quality and accuracy of internal processes for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations and information provided to the department’s executive and Audit Committee, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health:

Department of Health’s Response: Agreed. |

1. Introduction

This chapter outlines the Department of Health’s framework for managing audit recommendations and sets out the audit objective, scope and criteria.

Overview

1.1 Performance audits play an important role towards stimulating improvements in the administration and management practices of public sector organisations. Recommendations made in Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) performance audits and in internal audit reports highlight actions that are expected to improve entity performance when implemented and generally address risks to the successful delivery of outcomes. The appropriate and timely implementation of recommendations that have been agreed by management is an important part of realising the full benefit of an audit.15

1.2 This audit examines the Department of Health’s (Health) system for monitoring the implementation of recommendations arising from ANAO performance audits—often referred to as ‘external’ audits—and the department’s internal audits.16

Governance, performance and accountability

1.3 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) sets out the Australian Government’s framework for the governance, performance and accountability of Commonwealth entities, and the use and management of public resources. Under section 15 of the PGPA Act, the accountable authority of an entity has specific responsibilities to govern the entity in a way that promotes ‘proper use’17 and management of public resources, the achievement of its purposes and financial sustainability. The Secretary of Health is the accountable authority for the Department of Health.18

1.4 Section 45 of the PGPA Act requires the establishment of an audit committee by the accountable authority. Audit committees are intended to provide independent advice and assurance to the accountable authority on the appropriateness of the entity’s accountability and control environment, including: financial and performance reporting, systems of risk oversight and control, and systems of internal control.19

1.5 While audit committees do not undertake management responsibilities and are not a substitute for management controls and accountabilities, they have an important role in helping to ensure that the entity derives the anticipated benefits from its internal audit activity, and responds appropriately to the findings and recommendations of external audits.

Health’s framework for managing audit recommendations

1.6 The Secretary of Health has established an Audit Committee which, according to its Charter, is to provide independent assurance and assistance on the department’s risk, control and compliance framework, and its external accountability responsibilities including its financial statement responsibilities.20

1.7 The department’s internal audit function, the Audit and Fraud Control Branch, supports the Audit Committee by undertaking internal audits; coordinating the department’s engagement with the ANAO on financial and performance audits; and monitoring progress on the implementation of audit recommendations.

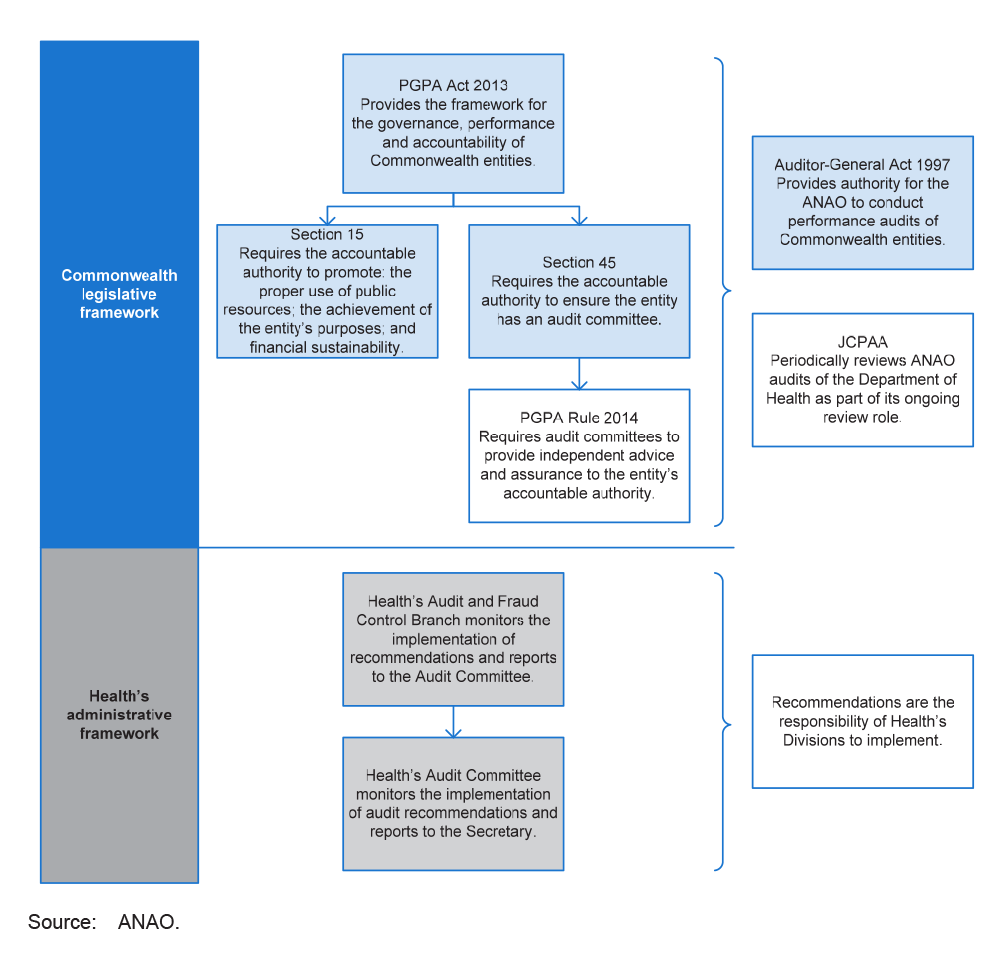

1.8 To monitor the implementation of audit recommendations, the Audit and Fraud Control Branch has established a system of regular reporting by responsible Divisions within the department. An illustration of the Department of Health’s framework for managing audit recommendations is at Figure 1.1. Chapter 2 examines the administrative framework in more detail.

Figure 1.1: The Department of Health’s framework for managing audit recommendations

Source: ANAO.

Parliamentary interest and previous audits

1.9 In recent years, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) and other parliamentary committees have expressed interest in the performance of Australian Government entities in relation to implementing audit recommendations. In addition, responses provided in the ANAO’s 2011 Survey of Parliamentarians indicated that periodic audits of the implementation of performance audit recommendations would be of benefit.21

1.10 In response to this feedback, the ANAO has conducted a program of performance audits on the implementation of audit recommendations. In the previous two financial years, the ANAO has completed the following audits:

- ANAO Audit Report No.25 2012–13 Defence’s Implementation of Audit Recommendations which examined the Department of Defence’s implementation of ANAO performance audit and internal audit recommendations;

- ANAO Audit Report No.53 2012–13 Agencies’ Implementation of Performance Audit Recommendations which was a cross-agency audit that examined the implementation of ANAO performance audit recommendations by four entities: the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations; the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs; the Department of Finance and Deregulation; and the Department of Infrastructure and Transport; and

- ANAO Audit Report No.34 2013–14 Implementation of ANAO Performance Audit Recommendations which was a cross-agency audit that examined the implementation of ANAO performance audit recommendations by two entities: the Department of Human Services; and the Department of Agriculture.

1.11 The JCPAA subsequently reviewed ANAO Audit Report No.25 2012–13 and ANAO Audit Report No.53 2012–13, indicating that it continues to support the strategic use of follow-up audits as part of the ongoing process of improving agency performance.22 The JCPAA also highlighted that:

The purpose of internal and external auditing is to identify weaknesses and better enable an organisation to address risk. The benefits of this work are undermined if agencies do not institutionalise robust monitoring, implementation, reporting and oversight mechanisms.23

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.12 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s monitoring and implementation of both ANAO performance audit and internal audit recommendations. The ANAO examined a sample of 220 ANAO performance audit and internal audit recommendations to assess the timeliness of Health’s implementation of the recommendations. A subset of seven closed ANAO performance audit recommendations and seven closed internal audit recommendations was also analysed in detail to assess the adequacy of the implementation of the recommendations.

1.13 To conclude against the audit objective, the audit examined whether the Department of Health’s arrangements for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations:

- provided adequate visibility and assurance to departmental management regarding the status of audit recommendations, with appropriate involvement by the Audit Committee and internal audit function; and

- facilitated appropriate implementation of ANAO, and internal audit, recommendations by agency management in a timely manner.

1.14 The ANAO also compared the department’s overall performance in implementing recommendations against seven other departments that have been the subject of recent ANAO audits on the implementation of audit recommendations.24 As discussed, these audit reports are part of a program of performance audits conducted in response to ongoing parliamentary interest in entities’ implementation of audit recommendations.

1.15 The audit methodology for the current audit broadly included:

- an analysis of the department’s systems and processes for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations;

- an examination of hard copy and electronic documentation in relation to the implementation of a sample of audit recommendations; and

- interviews with audit staff, the Audit Committee members and representatives from the Divisions responsible for the implementation of recommendations.

1.16 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $325 800.

Report structure

1.17 The structure of the report is outlined below:

- Chapter 2: Governance Arrangements examines the governance arrangements that the Department of Health has in place to monitor the implementation of audit recommendations; and

- Chapter 3: Implementation of Audit Recommendations reports on the extent to which the Department of Health has implemented audit recommendations from both ANAO performance audits and internal audits.

2. Governance Arrangements

This chapter examines the governance arrangements that the Department of Health has in place to monitor the implementation of audit recommendations.

Introduction

2.1 Governance refers to the arrangements and practices which enable an organisation to set direction and manage its operations to achieve expected outcomes and discharge its accountability obligations.25 The Department of Health’s (Health) governance arrangements for managing audit recommendations are largely supported by the department’s internal audit function, the Audit and Fraud Control Branch, which coordinates and reviews information provided by program managers. The department’s Audit Committee has oversight of the progress made by the department in implementing recommendations.

2.2 This chapter examines the department’s governance arrangements and processes for monitoring the implementation of ANAO performance audit and internal audit recommendations.

Audit committees and internal audit

2.3 The role that audit committees play in the governance framework of public sector entities flows from the legislative base established by government. Audit committees do not displace or change the management accountability arrangements within entities, but enhance the existing governance framework, risk management practices, and control environment by providing independent assurance and advice on key elements of an entity’s operations.26 The precise role an audit committee undertakes should be determined by the accountable authority27 of the public sector entity in consultation with the audit committee, within the context of each entity’s governance framework and other assurance mechanisms. Each entity is required to establish an audit committee and determine the functions of the committee through a written charter.28

2.4 Figure 2.1 identifies the roles and responsibilities of the Department of Health’s Audit Committee in relation to internal and external audits including monitoring the implementation of both internal and external audit recommendations. These responsibilities were included in the Charter for the Audit Committee approved by the Secretary of Health in November 2013.

Figure 2.1: Audit Committee responsibilities

Source: Department of Health, Audit Committee Charter, November 2013.

Note: Emphasis added.

2.5 During this audit, the department was revising the Audit Committee Charter in light of the revised resource management framework that took effect from 1 July 2014 under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and section 17 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014.29

2.6 The Audit Committee comprises three independent external members30, one of whom is the Chair, and six departmental members. There are four ‘participating observers’ which includes a representative from the ANAO, the Chief Operating Officer of the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA)31, the Chief Finance Officer and the Assistant Secretary of the Audit and Fraud Control Branch.32

2.7 The Audit Committee met seven times during 2013–14 to consider issues in relation to the department’s risk, control and compliance framework as a basis for providing assurance and advice to the Secretary on these matters. The Audit Committee considers the implementation of audit recommendations at least on a bi-annual basis. It reviewed the progress of the implementation of audit recommendations twice in 2013–14.

2.8 The Audit and Fraud Control Branch supports the Audit Committee’s review process by providing the Committee with information which outlines the implementation status of audit recommendations that have not been formally closed.33 More broadly, the role of the Audit and Fraud Control Branch as set out in the department’s Audit Manual, is to promote and improve the department’s corporate governance arrangements, through the conduct of audits and investigations and the provision of high quality advice and assistance.34 In 2013–14, the Branch completed 24 audits, close to its target of 25 reports for 2013–14. An external review of Branch activities in 2010 noted that the Audit and Fraud Control Branch had, over time, consistently achieved the total annual audits it had committed to deliver, in the context of an increasing workload. Moreover, feedback from a range of stakeholders indicated that the quality and consistency of internal audit products had improved markedly since 2007–08.35

2.9 The Audit Committee reviews the quality of the support provided by the Audit and Fraud Control Branch through an annual survey. The results of these annual surveys are held by the Chair of the Audit Committee and are not made available to the Branch for analysis and reporting. However, the ANAO’s assessment of minutes from the meetings at which the results of the surveys were discussed found that the Audit Committee’s views on the performance of the Audit and Fraud Control Branch were generally positive. Further, Audit Committee members advised the ANAO that they were satisfied with the quality and timeliness of information provided by the Audit and Fraud Control Branch on the implementation of audit recommendations.

Program management responsibilities

2.10 The successful implementation of audit recommendations requires strong senior management oversight with implementation planning that sets clear responsibilities and timeframes for addressing the required action.36 A better practice approach to the implementation of significant audit recommendations features the development of implementation plans in consultation with the department’s internal audit function and audit committee, if appropriate, that set clear responsibilities and timeframes for addressing the required action.37

2.11 Within Health, primary responsibility for the implementation of audit recommendations rests with Divisions. The department’s Audit and Fraud Control Branch consults closely with responsible Divisions in the development of implementation plans for internal audit recommendations, however, there is no consultation with Divisions in the development of implementation plans for ANAO recommendations. The lack of engagement by the internal audit function in the development of implementation plans for ANAO recommendations may, in part, explain why 86 per cent of internal audit recommendations sampled were adequately implementedN compared to only 43 per cent of ANAO recommendations. Moreover, it takes five months longer on average to implement an ANAO recommendation than internal audit recommendations. Improved consultation with Divisions by the Audit and Fraud Control Branch would help improve the quality and consistency of implementation plans for ANAO audit recommendations, and may contribute to improved implementation of ANAO recommendations.38 Differences in the implementation of ANAO and internal audit recommendations are outlined in more detail in Chapter 3.

Systems for monitoring recommendations

2.12 While the implementation of audit recommendations is a management responsibility, internal audit is well placed to monitor progress of implementation.39 Effective monitoring requires a system that accurately tracks progress and records the actions of program managers responsible for progressing action against timeframes.

2.13 In previous audits, the ANAO has examined the systems that some entities have developed to capture audit recommendations and monitor their implementation. The monitoring systems differ amongst entities. Some entities have developed an electronic database that tracks progress. One department has developed an intranet based database application to monitor internal and external audit recommendations. The implementation status of recommendations can be updated at any time by nominated officers in Divisions throughout the department. Any changes made in the system are automatically logged and the department’s internal audit function performs quality control checks and monitors these changes. The information entered in the database allows internal audit to generate a ‘traffic light report’ which is used to provide an update to the Audit Committee every four months.40 Other entities, such as the Department of Health, employ a basic system relying on spreadsheets and tables which are emailed to the relevant program areas for them to update and return to the Audit and Fraud Control Branch.

Information systems

2.14 To assist the Audit Committee in assessing the appropriateness and timeliness of action taken in response to recommendations, reporting by Divisions to the Audit and Fraud Control Branch should include all of the necessary information and be an accurate representation of the implementation status of the recommendation.

2.15 The Department of Health’s system of iterative spreadsheets and emailed documents provides the basis for preparing key information to the Audit Committee on progress made by program areas in implementing audit recommendations. However, the use of this system has an inherent risk in terms of potential data loss which may result from the manual transfer of information from one spreadsheet to another. The ANAO’s analysis identified an instance where information was omitted through the manual manipulation of aggregate figures.41 While this information was still available from earlier versions of the spreadsheets, this example highlights the risks inherent in systems based on the manual handling of data.

2.16 Further, the department’s current system is not well suited to tracking progress in implementation. To track the implementation of a recommendation often requires accessing multiple spreadsheets, written documents and hard copy files.

2.17 There is scope to improve the efficiency and accuracy the department’s audit recommendation implementation data through the use of a consolidated database. The Audit and Fraud Control Branch is in the process of developing a Microsoft Access database to record audit recommendations and track progress.42 The database holds the same information available in the Audit Committee papers including the recommendation, its priority rating, implementation action and timeframes and the responsible Division. It also has additional information including:

- the auditor responsible for making the recommendation;

- the Audit Committee meeting date when the monitoring process for the recommendation commenced; and

- who authorised the closure of the recommendation.

2.18 The Audit and Fraud Control Branch advised the ANAO that the new database will be used to run reports that will form the basis of reports to the Audit Committee on audit implementation, thereby automating a large proportion of the follow-up process. The department also expects the database to provide a more accurate and flexible reporting capability. The Audit and Fraud Control Branch anticipates that it will have the capability to provide more detailed and targeted reports, including trend data (for example on the length of time to implement recommendations by priority rating), by Division and by audit type.

Health’s monitoring system

2.19 Health’s Audit Committee reviews the status of recommendations on at least a bi-annual basis. In preparation for these bi-annual reviews, the Audit and Fraud Control Branch emails a list of audit recommendations to the relevant Divisions for review and updating. Figure 2.2 outlines the process that the Audit and Fraud Control Branch uses to monitor and report the status of audit recommendations.

Figure 2.2: Process for reporting to Audit Committee

Source: ANAO.

2.20 The Audit and Fraud Control Branch updates the spreadsheet based on the responsible Division’s response, which may include a revised timeframe or advice that a recommendation has been implemented and should therefore be closed. The Audit and Fraud Control Branch applies a ‘reasonableness check’ to the updated information provided by Divisions.43 Further information or clarification is sought by the Audit and Fraud Control Branch as required, which the ANAO observed had been done on several occasions. The ANAO’s analysis of the department’s handling of audit recommendations over a three year period showed that two ANAO reports with three relevant recommendations and one internal audit report with one recommendation were not captured in the spreadsheet.

2.21 The department’s program areas tended to revise their estimated implementation dates a number of times before recommendations were completed.44 In one case, the estimated implementation date for an internal audit recommendation was revised five times, and was completed three years after the original estimated implementation date and more than eight months after the final revised implementation date. The current process does not require Divisions to formally request extensions to implementation timeframes for recommendations; a shortcoming which should be addressed in the context of process improvements discussed in the next section.

Closure of recommendations

2.22 In previous audits of entities’ implementation of audit recommendations, the ANAO has identified instances where limited supporting information was provided to the internal audit function or audit committee to support the closure of recommendations. Audit committees generally rely on advice from program management areas that audit recommendations have been implemented and therefore no longer need to be monitored by the audit committee. There are benefits in entities requiring sign-off by senior management prior to the closure of recommendations. In two entities, the ANAO observed that it was a standard procedure for sign-off to occur at the Deputy Secretary level and in these entities a higher proportion of recommendations had been adequately implemented.45

2.23 Health’s process for closing recommendations does not require the responsible program area to provide evidence of implementation of the recommendation. The Audit and Fraud Control Branch and Audit Committee rely on the advice provided by Division Heads that recommendations have been implemented. The ANAO found that while 36 per cent of a sample of audit recommendations had not been adequately implementedO they had nonetheless been closed in the department’s monitoring system.46 The rate of early closure in the ANAO’s sample highlights the risk of closing recommendations without appropriate assurance. The department should obtain an appropriate level of assurance from responsible Divisions to support requests to close audit recommendations and in the case of significant recommendations, consider the benefit of sign-off at the Deputy Secretary level.

2.24 When a Division advises the Audit and Fraud Control Branch that an audit recommendation has been implemented, the Assistant Secretary of the Audit and Fraud Control Branch will make a determination about ‘closure’ of the outstanding recommendation, in consultation with the Chair of the Audit Committee.47 The outcomes from these discussions are not always documented in a clear and consistent manner.48 The department should record the basis for all decisions to close audit recommendations as implemented.

Information for Audit Committee

2.25 It is important that the information provided to the Audit Committee is accurate, relevant and timely so the Committee can readily assess issues and risks associated with implementation of audit recommendations. The Audit and Fraud Control Branch provides to the Audit Committee a listing of all outstanding audit recommendations classified by delay in implementation (that is, three to six months, six to twelve months and more than twelve months). The Audit Committee is also provided with more detailed information on the most significant recommendations, including proposed action and associated timeframes.49

2.26 Health classifies both ANAO and internal audit recommendations according to the degree of risk and exposure faced by the department, should recommendations not be implemented. The Audit and Fraud Control Branch assigns ratings to all recommendations according to a three-tiered ‘priority rating scale’. The highest rating for recommendations is ‘significant’ and is applied to recommendations that present ‘major issues or exposure for the Department’. The next highest rating is ‘moderate’ and is applied to recommendations that could ‘benefit the efficiency/effectiveness of business and should be addressed to reduce risk to an acceptable level’. The lowest priority rating is ‘procedural’ and is applied to recommendations relating to ‘issues of a routine nature that should be directed at ongoing administrative improvement’.

2.27 The Audit Committee further refined the priority rating scale in December 2010 by allocating timeframes to recommendations classified as significant, moderate and procedural.50 This approach reflects better practice as discussed in the ANAO Better Practice Guide Public Sector Internal Audit:

As a general rule, recommendations designed to address the highest category of risk exposure would be acted on immediately and implemented within one to three months; medium risk exposures would be implemented within three to six months and low level risk exposures within six to 12 months. Where recommendations involve a long lead time to address fully, for example where changes to policy, purchases of new equipment or services are involved, better practice suggests the action plan and timeframe is broken up into stages.51

2.28 The application of a risk based approach to assessing audit recommendations and implementation timeframes can contribute to the Audit Committee’s oversight of implementation, discussed in the following paragraphs.

Audit Committee oversight

2.29 A distinguishing feature of an audit committee within an entity’s governance framework is its potential for objectivity, as audit committees do not undertake management responsibilities. An effective agency system for implementing audit recommendations will be supported by an audit committee that monitors management’s implementation of audit recommendations, prioritising recommendations that are overdue or that pose significant risk or exposure to the department.52

2.30 The department’s Audit Committee actively monitors overdue and significant audit recommendations and, at times, has taken direct follow-up action. For instance, the Audit Committee has requested the attendance of Division Heads responsible for the implementation of recommendations to discuss progress and the approach adopted. In one case, a Division Head appeared before the Audit Committee to provide an explanation as to the reason the Division disagreed with a recommendation made in an internal audit report. In another case, a Division Head from the responsible area appeared at the Audit Committee to provide an update on the implementation of recommendations that were of particular concern to the Committee.

2.31 A review of Audit Committee minutes by the ANAO (for the period 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2012) indicates that the Audit Committee has expressed concerns on a number of occasions regarding overdue recommendations and inadequate implementation schedules, particularly where the corrective action outlined by the responsible Division did not justify the estimated implementation date.53 The Audit Committee requested follow-up action on specific recommendations on at least eight occasions over the three year period examined by the ANAO and expressed concern over estimated timeframes on at least six occasions.

2.32 Previous ANAO reports on the implementation of audit recommendations have observed the importance of the audit committee keeping the departmental Secretary informed of progress in implementing recommendations, on an as needs basis.54 The Chair of Health’s Audit Committee advised the ANAO that he meets with the Secretary after every Audit Committee meeting to discuss any significant issues or risks to the department identified in Audit Committee meetings. The Secretary is also provided with a copy of the Audit Committee minutes from every meeting. In addition to this, the Audit Committee will write to the Secretary as necessary, providing advice on matters such as the department’s financial statements and Certificate of Compliance.55

2.33 The Audit Committee’s Charter requires the Committee to provide a report to the Secretary, on at least an annual basis, detailing its operations and activities. The Audit Committee has provided annual reports to the Secretary which have identified a range of issues including changes to Audit Committee membership, the scale of the internal audit work program, updates on risk management and fraud control activities and updates on issues of non-compliance within the department. The ANAO reviewed these annual reports over three years from 2009–10 and found that they also included an update on the implementation of outstanding audit recommendations. The information is provided in the form of high level statements regarding the closure of recommendations and possible improvements.

Conclusion

2.34 It is an entity’s responsibility to manage the implementation of audit recommendations to which it has agreed. Primary responsibility for implementing audit recommendations within Health lies with senior managers in the program area or business units subject to the audit. While the implementation of audit recommendations is a management responsibility, the internal audit function is well placed to monitor the progress of implementation. Effective monitoring requires a system that accurately tracks progress and records the actions of program managers responsible for progressing action against timeframes.

2.35 The department’s Audit and Fraud Control Branch discharges the internal audit function. The Branch has a well-established process for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations. The Branch liaises with relevant Divisions for updates on the implementation of audit recommendations, which provide a basis for reporting to the Audit Committee twice a year. A system of iterative spreadsheets and emailed documents is used to prepare key information for the Audit Committee on progress made by program areas in implementing audit recommendations. While the information is relevant and well-targeted, the use of this system has an inherent risk in terms of potential data loss from the manual transfer of information from one spreadsheet to another.56 Moreover, the department’s current system is not well suited to readily tracking progress in implementation over the life of a recommendation. To track the course of implementation of a recommendation often requires accessing multiple spreadsheets, written documents and hard copy files.

2.36 The ANAO also noted that limited supporting information was provided by program areas to support the closure of recommendations as implemented. The Audit and Fraud Control Branch and Audit Committee generally rely on advice provided by the First Assistant Secretaries (Division Heads) from the program areas responsible for implementation that recommendations have been implemented. The ANAO identified a number of audit recommendations that have not been adequately implemented despite being closed in the audit recommendation monitoring system. There are benefits in requiring formal sign-off by senior management prior to the closure of recommendations. As highlighted in ANAO Audit Report No.53 2012–13 Agencies’ Implementation of Performance Audit Recommendations, for those entities that required senior management sign-off at the Deputy Secretary level, the ANAO observed a higher proportion of recommendations had been adequately implemented.57

2.37 There is no formal process through which Divisions seek extensions to the implementation timeframes for recommendations, and the six monthly update to the Audit Committee schedules is when a possible delay to implementation is first identified. In many cases, Divisions revised their estimated implementation dates numerous times before recommendations were completed. A review of Audit Committee minutes by the ANAO (for the period 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2012) indicates that the Audit Committee has expressed concerns on a number of occasions regarding overdue recommendations and inadequate implementation schedules, particularly where the corrective action outlined by the responsible Division did not justify the estimated implementation date.58 The Audit Committee requested follow-up action on specific recommendations on at least eight occasions over the three year period examined by the ANAO and expressed concern over estimated timeframes on at least six occasions. To avoid the risk of drift in the timeliness of implementation, responsible Divisions should formally request extensions to agreed implementation timeframes for audit recommendations.

Recommendation No.1

2.38 To improve the quality and accuracy of internal processes for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations and information provided to the department’s executive and Audit Committee, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health:

- record clear deliverables and timeframes for the implementation of all audit recommendations;

- require responsible Divisions to formally request extensions to agreed implementation timeframes;

- seek appropriate assurance from responsible Divisions supporting requests for the closure of audit recommendations as implemented; and

- record the basis for all decisions to close audit recommendations as implemented.

Department of Health’s Response: Agreed.

3. Implementation of Audit Recommendations

This chapter reports on the extent to which the Department of Health has implemented audit recommendations from both ANAO performance audits and internal audits.

Introduction

3.1 Audit recommendations identify risks to the successful delivery of outcomes consistent with policy and legislative requirements, and highlight actions aimed at addressing those risks, and opportunities for improving entity administration. Entities are responsible for the implementation of audit recommendations to which they have agreed, and the timely implementation of recommendations allows entities to realise the full benefit of audit activity.59

3.2 This chapter examines the Department of Health’s (Health) performance in implementing ANAO performance audit and internal audit recommendations.

Audit approach

3.3 The ANAO assessed Health’s performance in implementing seven recommendations from three ANAO audit reports tabled in Parliament between 1 July 2009 and 30 June 2012.60 The ANAO also examined the implementation of seven recommendations from six internal audit reports finalised during the same three year period.61 All audit recommendations selected for assessment had been recorded as fully implemented (that is, closed) by the Audit and Fraud Control Branch.

3.4 Table 3.1 summarises the number of audit recommendations assessed by the ANAO for progress in implementation and the timeliness of implementation.

Table 3.1: Number of recommendations assessed, July 2009–June 2012

|

Recommendations assessed |

ANAO |

Internal audit |

Total |

|

|

Assessed for implementation |

No. of audit recommendations |

7 |

7 |

14 |

|

No. of audit reports |

3 |

6 |

9 |

|

|

Assessed for timeliness |

No. of audit recommendations |

35 |

185 |

220 |

|

No. of audit reports |

14 |

58 |

72 |

|

Source: ANAO.

3.5 The ANAO reviewed entity documentation, interviewed key staff, and extracted data from the department’s monitoring system to assess the implementation of 14 recommendations, appearing in nine audit reports. The extent to which implementation had been achieved was considered in the context of the relevant Division’s progress towards the intended outcome of the audit recommendation. The definitions used to assess the extent to which recommendations had been implemented are provided in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: ANAO’s categorisation of implementation

|

Category |

Explanation |

|

Adequate implementation |

The action taken met the intent of the recommendation, and sufficient evidence was provided to demonstrate action taken. |

|

Partial implementation |

This category encompasses three considerations:

|

|

Not adequate implementation |

This category encompasses two considerations:

|

Source: ANAO.

3.6 The ANAO also assessed the timeliness of Health’s implementation of audit recommendations. This analysis was done by reviewing and collating the information held by the Audit and Fraud Control Branch regarding the implementation of ANAO and internal audit recommendations made from 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2012. This analysis, which involved a review of 220 recommendations (comprising 35 ANAO recommendations and 185 internal audit recommendations appearing in 72 audit reports), also excluded recommendations relating to programs and services in ageing and sport, and recommendations from the department’s internal audits of its state and territory offices.

ANAO assessment of the implementation of audit recommendations

3.7 The ANAO has indicated in previous audits that a structured and planned approach to the implementation of audit recommendations assists entities to manage timeliness, completeness and adequacy of implementation, by allowing progress to be clearly targeted and monitored within the program management area.62

3.8 Table 3.3 provides a summary of the ANAO’s assessment of Health’s implementation of a sample of seven ANAO audit recommendations and seven internal audit recommendations. The audit recommendations have been provided in full at Appendix 2 including the ANAO’s assessment of them. In summary, nine of the 14 recommendations in the ANAO’s sample had been adequately implemented. Five recommendations had only been partially implemented, despite having been closed (as fully implemented) in the department’s monitoring system for audit recommendations.

Table 3.3: Overview of the ANAO’s assessment

|

Implementation category |

ANAO recommendations |

Internal audit recommendations |

Total |

|

Adequate implementation |

3 (43%) |

6 (86%) |

9 (64%) |

|

Partial implementation |

4 (57%) |

1 (14%) |

5 (36%) |

|

Not adequate implementation |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

7 |

7 |

14 |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note: The implementation categories used to assess the recommendations are outlined in Table 3.2.

3.9 Overall, the department performed better in implementing the recommendations from internal audits than ANAO recommendations. Of the seven ANAO recommendations that were analysed, only three of the recommendations were adequately implemented, compared to six internal audit recommendations. This difference could in part be attributed to the higher level of engagement between the Audit and Fraud Control Branch and responsible Divisions when developing implementation plans for internal audit recommendations. As discussed in Chapter 2, the ANAO was advised by the department that once the Audit and Fraud Control Branch had drafted an internal audit report, it continued to work with the responsible program manager to develop an implementation plan for the audit recommendations and associated implementation dates. These discussions occurred before an internal audit report had been finalised. This level of engagement in the development of an implementation plan does not occur with ANAO recommendations. Instead, program areas advise the Audit and Fraud Control Branch of proposed actions and timeframes for implementing ANAO recommendations when they provide their twice-yearly status update to the Audit Committee.

3.10 The difference observed in progressing the implementation of ANAO recommendations and internal audit recommendations could also be related to the style of the recommendations themselves. ANAO recommendations tend to be less prescriptive than internal audit recommendations, which generally outline the specific action to be taken by the responsible Division. The focus of ANAO recommendations tends to be on the desired outcome—how this is achieved is generally left to the department. The ANAO’s approach allows the department to tailor the implementation of recommendations to its current operating environment.

3.11 A typical example of an internal audit recommendation is that ‘staff are to be reminded of the Department’s recordkeeping policy, particularly in relation to documenting key decisions and retention of external correspondence’. This action is specific when compared with the following example of an ANAO recommendation:

To improve compliance with the regulatory framework, the ANAO recommends that the TGA [Therapeutic Goods Administration]: (a) use its random sampling review of listed medicines to develop risk profiles of sponsors and the most significant characteristics of medicines and (b) use the profiles to inform its program of post market reviews.

3.12 While the outcomes for this recommendation are clear, the ANAO has avoided detailing the process required to address the recommendation, leaving scope for the department to develop the most appropriate course of action to address the recommendation.

3.13 The ANAO’s assessment of the implementation of this ANAO recommendation found that it had only been partially implemented. While improvements had been made to the relevant IT system to capture the information necessary to develop risk profiles, sufficient information had not been collected to develop sufficiently reliable profiles on which the program of post market reviews could be based. By comparison, the ANAO found that the internal audit recommendation discussed above had been adequately implemented within six months.

Cross-entity comparison

3.14 In recent years the ANAO has conducted a program of performance audits that have assessed the implementation of audit recommendations by seven departments, using the same assessment criteria outlined in Table 3.2. While recognising that individual audit recommendations may vary in their scope and complexity, the ANAO’s published findings provide a basis for the comparative assessment of departmental performance.

3.15 Figure 3.1 presents the results from the three ANAO audit reports tabled to date63, alongside the results of the ANAO’s assessment of the Department of Health in the current audit. The figure indicates the proportion of recommendations that were assessed by the ANAO as adequately, partially or not adequately implemented by the audited departments, including Health. In summary, Figure 3.1 indicates that:

- an average of 65 per cent of recommendations were assessed as adequately implemented across the seven departments, as compared to 64 per cent in Health;

- an average of 22 per cent of recommendations were assessed as partially implemented across the seven departments, as compared to 36 per cent in Health; and

- an average of 13 per cent of recommendations were assessed as not adequately implemented across the seven departments, as compared to Health which had no recommendations in this category.

Figure 3.1: Implementation of audit recommendations by Australian Government entities

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note: Overall, the combined average for all eight audited departments has been: 65 per cent of audit recommendations adequately implemented; 24 per cent partially implemented; and 11 per cent not adequately implemented.

The closure of recommendations

3.16 The ANAO’s analysis of the implementation of 14 ANAO and internal audit recommendations indicates that Health’s processes for monitoring the implementation and closure of audit recommendations could be improved. The ANAO’s analysis identified that five of the recommendations were closed in the department’s system prior to being fully implemented, based on commitments by the responsible Divisions that appropriate action would be taken to address the recommendations, or that further action would be taken that would adequately address the recommendations. Subsequent analysis by the ANAO indicated that four of these recommendations did not go on to be adequately implemented.

3.17 Table 3.4 provides a listing of the recommendations examined by the ANAO, including the recommendations closed prior to implementation, based on commitments made by the responsible Divisions (blue shading). The table also indicates the priority ratings assigned to the recommendations and the ANAO’s assessment of the level of implementation.

Table 3.4: The closure of recommendations prior to implementation

|

Recommendations |

Priority rating |

Closed on a commitment? (Y/N) |

ANAO’s assessment |

|

ANAO recommendations |

|||

|

Rec 3, Report No.3 2011–12 |

Moderate |

Y |

Partial implementation |

|

Rec 4, Report No.3 2011–12 |

Moderate |

Y |

Partial implementation |

|

Rec 5, Report No.3 2011–12 |

Moderate |

Y |

Partial implementation |

|

Rec 2, Report No.44 2011–12 |

Moderate |

Y |

Partial implementation |

|

Rec 1, Report No.51 2010–11 |

Moderate |

N |

Adequate implementation |

|

Rec 3, Report No.51 2010–11 |

Procedural |

N |

Adequate implementation |

|

Rec 5, Report No.51 2010–11 |

Moderate |

N |

Adequate implementation |

|

Internal audit recommendations |

|||

|

Rec 1, Report No.30 2010–11 |

Significant |

Y |

Adequate implementation |

|

Rec 1, Report No.4 2009–10 |

Procedural |

N |

Adequate implementation |

|

Rec 2, Report No.15 2010–11 |

Significant |

N |

Adequate implementation |

|

Rec 1, Report No.6 2011–12 |

Moderate |

N |

Adequate implementation |

|

Rec 9, Report No.20 2011–12 |

Significant |

N |

Adequate implementation |

|

Rec 11, Report No.20 2011–12 |

Significant |

N |

Partial implementation |

|

Rec 3, Report No.22 2011-12 |

Significant |

N |

Adequate implementation |

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.18 Five of the 14 recommendations (36 per cent) examined by the ANAO were closed prematurely. The ANAO also observed that limited supporting information was generally provided to the Audit and Fraud Control Branch and the Audit Committee to support the closure of recommendations. The Audit and Fraud Control Branch and the Audit Committee generally relied on assurances from the responsible First Assistant Secretary (Division Head) that the recommendation had been implemented and, therefore, no longer needed to be monitored.

3.19 It is the responsibility of entity management to implement agreed audit recommendations, assess progress and report accurately on the state of implementation. That said, it is the responsibility of the department’s internal audit function to ensure that internal monitoring and reporting processes provide adequate assurance as a basis for advising the Audit Committee and the Secretary on progress with implementation. The internal audit function and the Audit Committee lose oversight of the progress of implementation where recommendations are closed prematurely. The early closure of recommendations means that the Audit and Fraud Control Branch and the Audit Committee are not able to adequately identify and monitor departmental risks, on behalf of the Secretary, or identify the need for remedial action where a Division is not making adequate or timely progress in its implementation of a recommendation. The department should obtain an appropriate level of assurance from responsible Divisions for all requests relating to the closure of audit recommendations as implemented, and consider the benefit of sign-off at a more senior level for significant recommendations.

The timeliness of the department’s implementation of audit recommendations

3.20 Audit recommendations can vary in scope and complexity, and as a consequence the implementation task may require coordination across a range of program delivery and support functions within an entity. The risks involved and the time taken to implement recommendations within entities can vary. Notwithstanding these considerations, if implementation is not progressed promptly, and individual risks remain untreated, the full value of the audit is not being achieved. In this context it is important that the internal audit function and the audit committee keep the entity’s accountable authority informed on progress with implementing recommendations that are complex, difficult or overdue.

3.21 Table 3.5 provides an overview of the timeliness of the department’s implementation of audit recommendations.64 As discussed, the ANAO examined the timeliness of Health’s implementation of a sample of performance audit recommendations from 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2012, which involved the review of 220 recommendations (comprising 35 ANAO recommendations and 185 internal audit recommendations).65 The results show that, on average, the ANAO and internal audit recommendations took 379 days to close, with ANAO recommendations taking 160 days longer to close than the internal audit recommendations. Additionally, a majority of all recommendations (75 per cent) were closed after the original estimated implementation date.

Table 3.5: Timeliness of implementation of audit recommendations, July 2009–June 2012

|

Recommendations |

ANAO |

Internal audit |

Total/average |

|

Average no. of days estimated to implement recommendations |

424 days |

155 days |

191 days |

|

Average no. of days to close recommendations |

514 days |

354 days |

379 days |

|

No. and percentage of recommendations closed on or before the original estimated implementation date |

2 (6%) |

19 (10%) |

21 (10%) |

|

No. and percentage of recommendations closed after the original estimated implementation date |

23 (66%) |

141 (76%) |

164 (75%) |

|

Average no. of extra days that it took for overdue recommendations to be closed |

244 days |

232 days |

234 days |

|

Total no. of recommendations |

35 |

185 |

220 |

Source: ANAO.

Note: The percentages provided in the table do not equal 100 as 10 (or 29 per cent) of the ANAO recommendations and 25 (or 14 per cent) of the internal audit recommendations did not have clear estimated implementation dates.

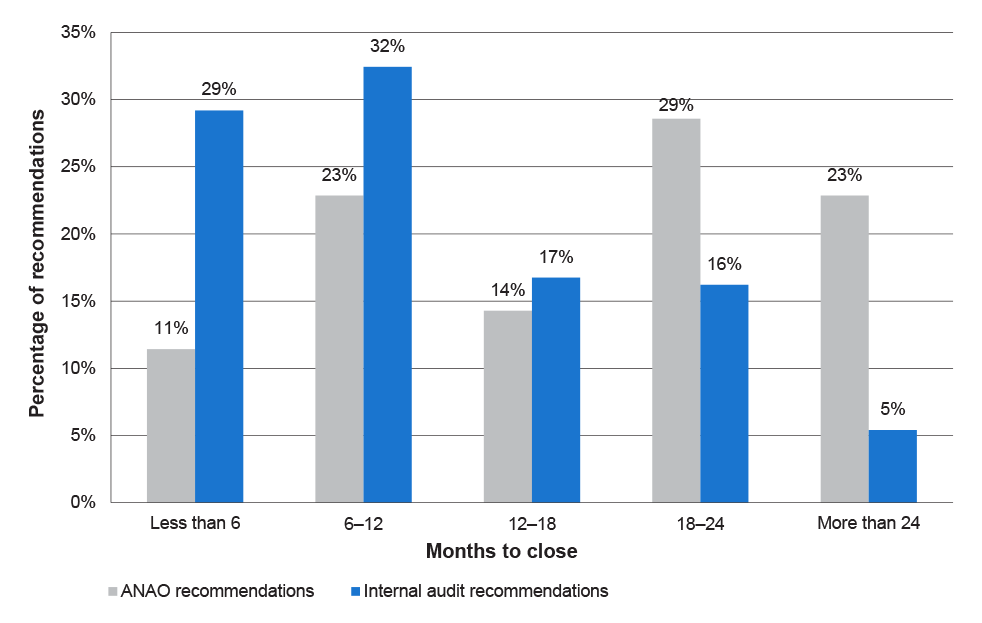

3.22 Figure 3.2 shows that 95 per cent of the internal audit recommendations examined were closed within two years, in comparison with 77 per cent of the ANAO recommendations examined. On average, internal audit recommendations took 12 months to close while ANAO recommendations took an average of 17 months to close.

Figure 3.2: Time taken to implement audit recommendations

Source: ANAO.

Note: This analysis involved 35 ANAO audit recommendations and 185 internal audit recommendations.

3.23 The closure of internal audit recommendations some five months earlier, on average, than ANAO recommendations may reflect the level of engagement between the responsible Divisions and the Audit and Fraud Control Branch in developing an agreed plan for implementing internal audit recommendations. As discussed at paragraph 3.9, implementation plans for internal audit recommendations are developed in consultation with the Audit and Fraud Control Branch prior to the audit reports being published, in contrast to the approach adopted for ANAO audits, which does not involve such consultation. Further, as discussed at paragraphs 3.10–3.12, the specificity of internal audit recommendations may also be a factor in their speedier implementation.

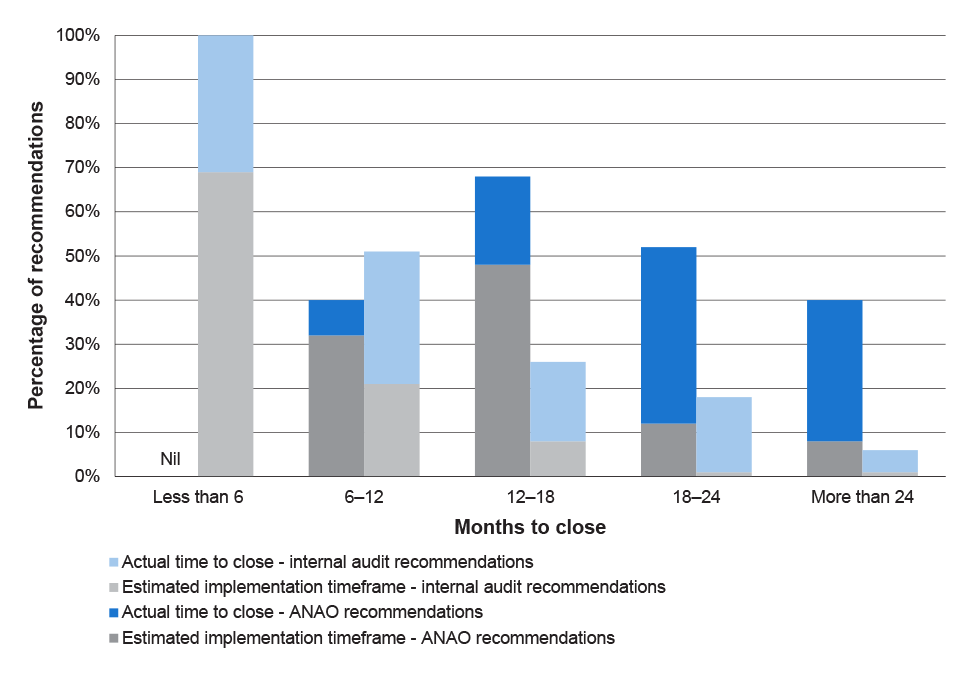

3.24 Figure 3.3 compares estimated and actual implementation times for the closed ANAO and internal audit recommendations.

Figure 3.3: Comparison of estimated and actual implementation times of audit recommendations

Source: ANAO.

Note: For the purposes of this analysis, recommendations that were not assigned a specific implementation date have not been included. This analysis involved 25 ANAO audit recommendations and 160 internal audit recommendations.

3.25 The ANAO’s analysis shows that, although 32 per cent of the ANAO recommendations and 90 per cent of the internal audit recommendations were estimated to be implemented in the first year, only eight per cent of the ANAO recommendations and 61 per cent of the internal audit recommendations were closed within this timeframe. Additionally, while eight per cent of the ANAO recommendations were estimated to take more than two years to implement, 32 per cent of the recommendations were closed in this timeframe. This contrasts with the internal audit recommendations, only five per cent of which took more than two years to close. The significant variance between estimated and actual implementation dates, for both ANAO and internal audit recommendations, indicates possible shortcomings in the department’s approach to assessing implementation risks, and the processes employed to monitor progress. Measures to address shortcomings in the monitoring and closure process have been identified in the recommendation for this audit. The related issues of accurately assessing implementation risks and timeframes require ongoing management attention within all Divisions responsible for planning the implementation of audit recommendations.

Priority rating scale

3.26 As discussed in Chapter 2, consistent with better practice the department applies a priority rating scale to all recommendations, based on the degree of risk and exposure to the department.66 The scale includes three categories—significant, moderate and procedural. The implementation timeframes are: three months for recommendations rated as significant; six months for recommendations rated as moderate; and 12 months for recommendations rated as procedural.

3.27 Table 3.6 shows that two thirds of the ANAO recommendations and over half of the internal audit recommendations from the sample period (1 July 2009 to 30 June 2012) were rated as a moderate risk by the department. Only 21 per cent of the recommendations were rated as significant and, of these, only 12 per cent of the ANAO recommendations were rated as significant. As discussed in Chapter 2, the schedules for significant recommendations are presented to the Audit Committee for review while the audit recommendations that are not classified as significant are incorporated into broader statistics.

Table 3.6: Priority rating scale and assessment of the sample recommendations

|

Priority ratings |

Implementation timeframes |

ANAO |

Internal audit |

Total |

|

Significant |

3 months |

7 (12%) |

54 (23%) |

61 (21%) |

|

Moderate |

6 months |

40 (67%) |

125 (54%) |

165 (56%) |

|

Procedural |

12 months |

9 (15%) |

54 (23%) |

63 (22%) |

|

Not rated |

|

4 (7%) |

Nil |

4 (1%) |

|

Total no. of recommendations |

|

60 |

233 |

293 |

Source: Department of Health records.

Note: The percentages provided in the table do not equal 100 due to rounding.

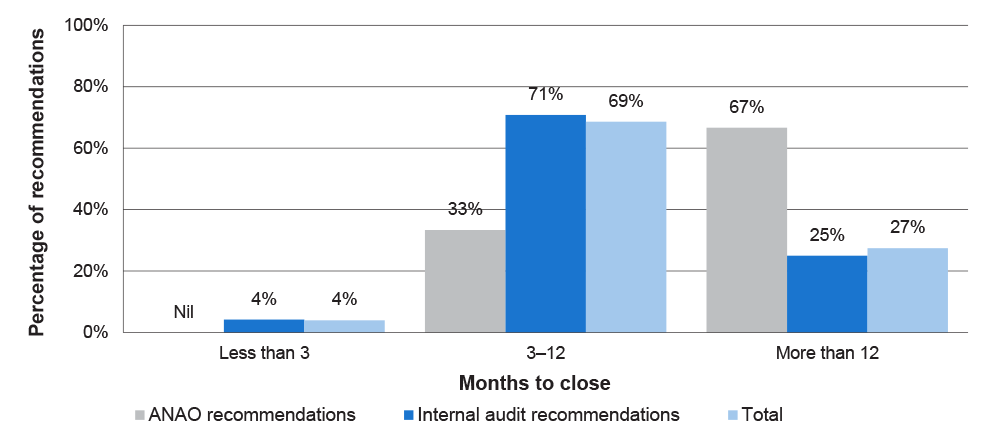

3.28 Figure 3.4 shows the length of time taken to close the significant recommendations in the sample examined by the ANAO. According to the department’s priority rating scale, significant recommendations should be implemented within three months. The results show that the majority of the significant recommendations (96 per cent) were not closed within the three month timeframe. Twentyseven per cent of the recommendations were closed more than twelve months after they were made and four of these recommendations took more than two years to close.

Figure 3.4: Time taken to close significant recommendations

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note: For the purposes of this analysis, only recommendations made after 14 December 2010 have been included, as that was when the revised implementation timeframes were introduced. This analysis involved three ANAO audit recommendations and 48 internal audit recommendations.

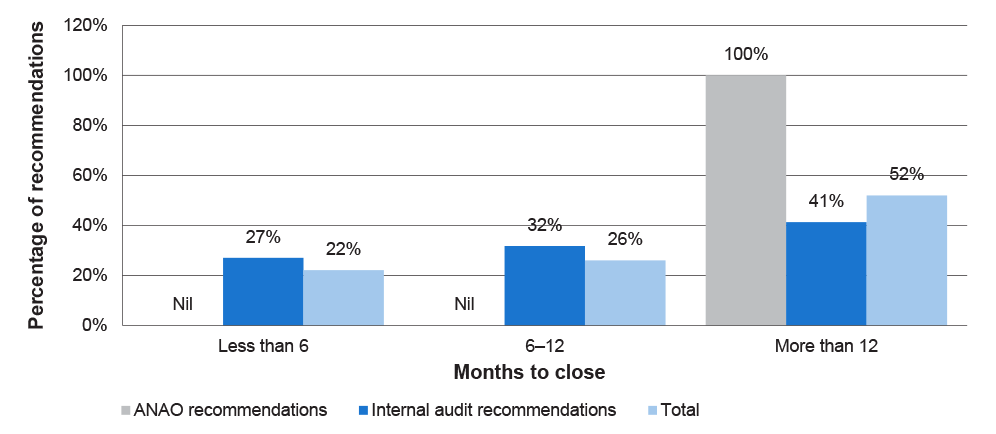

3.29 Figure 3.5 shows the length of time taken to close the moderate recommendations in the sample examined by the ANAO. According to the department’s priority rating scale, moderate recommendations should be implemented within six months. The results show that only 27 per cent of the moderate internal audit recommendations were closed within the six month timeframe. No moderate ANAO recommendations were closed within six months.

Figure 3.5: Time taken to close moderate recommendations

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note: For the purposes of this analysis, only recommendations made after 14 December 2010 have been included, as that was when the revised implementation timeframes were introduced. This analysis involved 14 ANAO audit recommendations and 63 internal audit recommendations.

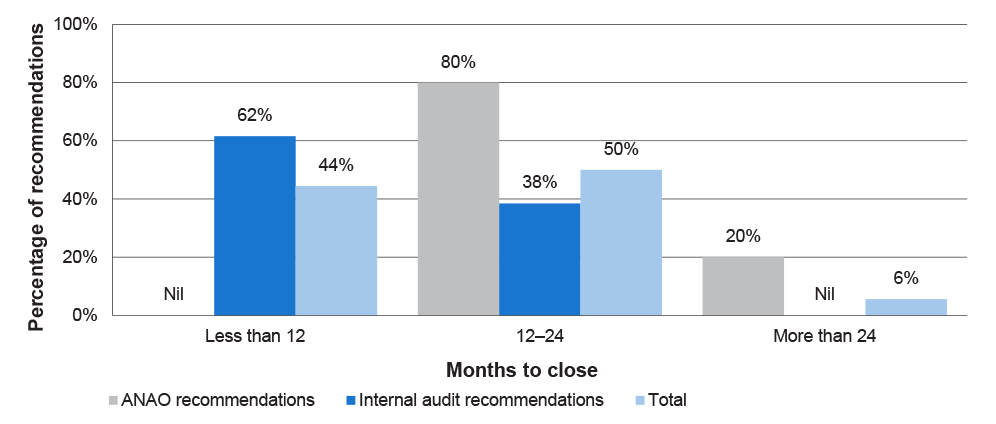

3.30 Figure 3.6 shows the length of time taken to close the procedural recommendations in the sample. According to the department’s priority rating scale, procedural recommendations should be implemented within 12 months. The results show that none of the procedural ANAO audit recommendations were closed within the 12 month timeframe, compared to 62 per cent of the procedural internal audit recommendations which were closed within 12 months.

Figure 3.6: Time taken to close procedural recommendations

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note: For the purposes of this analysis, only recommendations made after 14 December 2010 have been included, as that was when the revised implementation timeframes were introduced. This analysis involved five ANAO audit recommendations and 13 internal audit recommendations.