Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Implementation and Management of the Housing Affordability Fund

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of FaHCSIA’s administration of the HAF. To address this objective, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) assessed FaHCSIA’s administration against a range of audit criteria, including the extent to which:

- assessment and approval processes were soundly planned and implemented, and were consistent with the requirements of the overarching financial management framework;

- appropriately structured funding agreements were established and managed for each approved grant; and

- the performance of the HAF, including each of the funded projects, was actively monitored and reported.

Summary

Introduction

1. Housing quality is an important determinant of individual and family wellbeing. Good housing provides protection; access to essential services such as water, heating and sanitation; privacy; a place to keep possessions secure; a place to spend time with friends and family; and a means of expressing one’s identity.1 However, access to good housing can place significant demands on individual and family incomes if housing affordability is low. Housing affordability is a complex issue that is affected by a wide range of economic and social factors, including house prices, interest rates, levels of household income, inflation, housing availability and consumer tastes2 and preferences. When people struggle to pay for their housing, they are said to experience ‘housing affordability stress’.

2. Housing affordability stress can have serious consequences for individuals and families, and if this stress is sufficiently prevalent, consequences can also be observed at local, regional and even national levels. At the household level, housing affordability stress has an adverse effect on household budgets, possibly resulting in an overall reduction in quality of life. More broadly, housing affordability can affect decisions about where to live and work, where (or whether) to invest in property, and overall patterns of consumer spending and saving.

3. A range of indicators reflect lower levels of housing affordability3 and higher levels of housing affordability stress in Australia over the past decade. The National Housing and Supply Council reported that rapidly rising house prices between 1996 and 2008 contributed to a significant decline in housing affordability in Australia. The ABS reports that the proportion of homes sold that were affordable to low and moderate income households declined from 51 per cent in 2003–04 to 34 per cent in 2007–08.4 The Housing Industry Association (HIA) reported that the HIA Commonwealth Bank Housing Affordability Index in December 2010 was nearly 25 per cent lower than it was in March 2009, and was about 10 per cent below its December 2005 level.5

The Housing Affordability Fund

4. Given the range and seriousness of the consequences of housing affordability stress for citizens and for the economy, the Australian Government has put in place several initiatives and programs designed to help households to pay for housing and to increase the supply of affordable housing. One of these initiatives, the Housing Affordability Fund (HAF), was launched on 15 September 2008 with the objectives of increasing the supply of new homes while also reducing their cost by:

- reducing the cost of infrastructure works associated with housing developments, including connection of essential services (such as water, sewerage, and roads), construction of community facilities and open spaces (such as playgrounds), and undertaking site remediation works—referred to as infrastructure projects; and

- encouraging best practice in state and local government housing development assessment and planning processes, including speeding up development assessment and approval processes to help reduce ‘holding’ costs to developers—referred to as reform projects.

5. A key element in the design of the HAF was that the reductions in housing development costs associated with infrastructure projects were to be passed on to home buyers in the form of a rebate (or savings) against the market price of a certain number of new houses. To give practical effect to this policy intent, proposals for infrastructure funding were required to quantify the number of new houses that were expected to be constructed, the number of newly constructed houses to be sold at a reduced price (that is, those houses attracting savings), as well as the amount of savings that were to be passed on to buyers. In turn, funding agreements for infrastructure projects were designed to include mechanisms to measure the construction and sale of the new houses and the delivery of savings to home buyers.6

6. Funding from the HAF was to be made available through competitive application and assessment funding rounds. These funding rounds were open to local governments (or local government associations), and to state and territory government agencies. Private companies, including property developers, were encouraged to participate in the HAF by entering into partnership arrangements with government.

7. The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) was responsible for the administration of the HAF until the Administrative Arrangements Order of 14 September 2010 transferred responsibility for the program to the newly created Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPaC). The transfer of responsibility between the two departments was given practical effect through the transfer of staff and resources on 28 October 2010.

8. Through the HAF, the Australian Government planned to make available $500 million over the five year period from 2008–09 to 2012–13, with a further $12 million allocated to administer the fund. By September 2010, a total of $447.4 million had been committed from the HAF for 75 projects across Australia. Nine of these projects (worth $29.6 million), which related to the development and implementation of integrated electronic development application systems in each state of Australia, were not included within the scope of this audit. Funding for 62 of the 66 projects included in the scope of this audit (worth $234 million) was approved from the HAF through one of two competitive funding rounds, while funding for the remaining four projects (worth $183.8 million) was provided through direct offers made by the Australian Government for public housing redevelopment projects. By the end of September 2010, FaHCSIA had signed funding agreements in place for 49 of these 66 projects:

- 41 projects (worth $301.8 million) involving infrastructure works; and

- eight reform projects (worth $23.2 million).

9. All of the 41 infrastructure projects and one of the eight reform projects were required to pass savings to home buyers.

How the two funding rounds worked

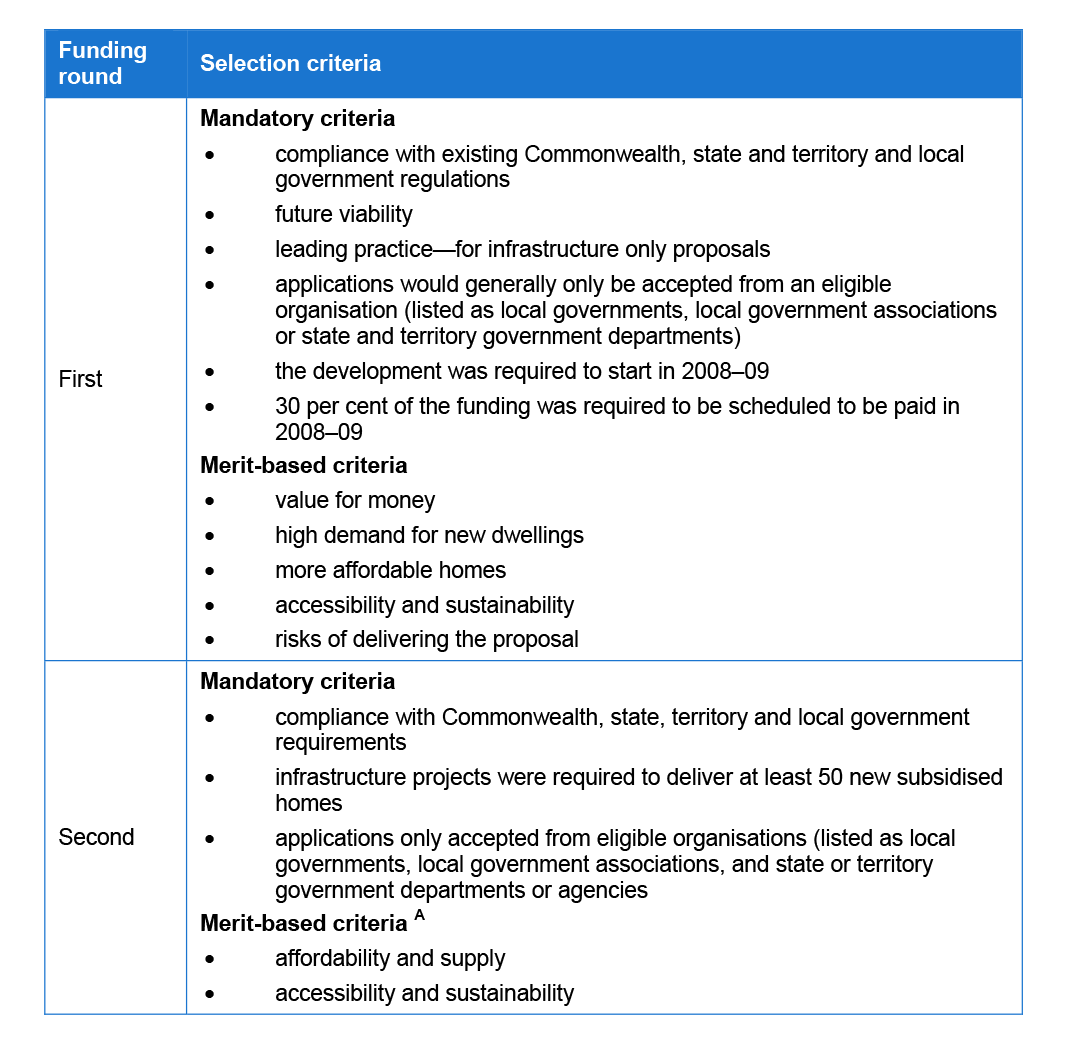

10. The guidelines published for each of the HAF’s funding rounds indicate that the HAF was designed to be a competitive, merit-based discretionary grant program. In this regard, the guidelines for both funding rounds stated that the relative merits of applications for funding were to be assessed against the selection criteria contained in the guidelines. Table S.1 outlines the selection criteria contained in the guidelines for each funding round.

Table S.1: Published selection criteria

Note A: Although value for money is not specifically identified as one of the selection criteria in the second funding round, the guidelines stated that the overriding principle guiding the selection process was value for money.

Source: ANAO analysis.

11. The first funding round involved a two-stage application and assessment process. The first stage involved the assessment of expressions of interest, and the second stage entailed the assessment of more detailed business cases submitted by applicants shortlisted from the first stage. Following an independent review designed to help inform the conduct of future funding rounds, FaHCSIA decided that the second funding round would be a single stage application and assessment process.

12. In each funding round, FaHCSIA used an automated tool in the assessment of the relative merits of applications against the published selection criteria. Following its assessment of applications, FaHCSIA provided a series of funding recommendations to the then Minister for Housing, including details of the projects that the department recommended be funded. The then Minister had responsibility for the funding decisions made under the HAF.

The public housing redevelopment projects

13. Three of the four public housing redevelopment projects funded from the HAF (worth $24.4 million) were approved for funding in June 2009 in order to utilise unspent program funds. The remaining project (worth $159.4 million) was approved for funding in August 2009.

Funding three projects at the end of the first funding round

14. In mid-April 2009, FaHCSIA advised the then Minister of a likely underspend of approximately $12 million in the HAF program for the 2008–09 financial year.7 The department’s advice outlined the following five options to address the spending shortfall:

- rephase the underspent funding to the 2009–10 financial year;

- return the underspent funds;

- support a proposal for an affordable housing trial in Adelaide and Sydney;

- support the development of more social housing dwellings; or

- support the implementation of local government reforms aimed at delivering more affordable housing.

15. The department recommended allocating funding to each of the latter two options to offset the likely underspend. Departmental records indicate that the then Minister asked to discuss the department’s recommendations. However, the department did not have any record of the outcome of these discussions. FaHCSIA advised the ANAO that the department approached a number of state and territory housing departments seeking advice on possible projects that would be ready to be advanced quickly and that were consistent with HAF objectives. As a result, FaHCSIA began exploring options to provide funds for five public housing redevelopment projects. The general purpose of funding these projects closely aligned with the fourth option to address the spending shortfall initially recommended by FaHCSIA. On 23 June 2009, the department recommended, and the then Minister approved, funding for three of these projects totalling $24.4 million, which equated to the actual amount of the expenditure shortfall.8 None of the projects considered by the department had previously sought funding through the first funding round.

Funding the remaining project prior to launch of the second funding round

16. In August 2009, prior to the launch of the second funding round, the Australian Government agreed that the then Minister for Housing would provide $175.3 million from the HAF to the Victorian Government to support three public housing redevelopment projects. The Australian Government’s decision to fund these projects from the HAF was made in the context that the then Minister for Housing would also reduce Victoria’s allocation of funding from the Australian Government’s Social Housing Initiative9 by an equivalent amount. These projects had previously been proposed under stage two of the Social Housing Initiative, but had not been approved at the time. In March 2010, following negotiations with the Victorian Government, and with the then Minister’s agreement, FaHSCIA finalised the agreement to provide funding of $159.4 million (GST exclusive) for these three projects.10

Audit objective and approach

17. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of FaHCSIA’s administration of the HAF. To address this objective, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) assessed FaHCSIA’s administration against a range of audit criteria, including the extent to which:

- assessment and approval processes were soundly planned and implemented, and were consistent with the requirements of the overarching financial management framework;

- appropriately structured funding agreements were established and managed for each approved grant; and

- the performance of the HAF, including each of the funded projects, was actively monitored and reported.

18. The audit findings discussed in this report are based on the ANAO’s review of the systems and processes in place at FaHCSIA, and the decisions made by FaHCSIA. The audit did not examine the transfer of resources from FaHCSIA to SEWPaC following the Administrative Arrangements Order of 14 September 2010, nor did it assess the systems and processes used by SEWPaC. However, some fieldwork was undertaken at SEWPaC in order to:

- gain an understanding of initiatives put in place by SEWPaC to administer the HAF since the transfer of responsibility; and

- obtain more up-to-date information on the progress of the examined projects and on key financial data about the HAF.

Overall conclusion

19. Over the last decade, an increasing number of Australians have experienced ‘housing affordability stress’, a difficulty to pay for appropriate housing within their means. This stress has a range of negative consequences for householders and their families, and for the Australian economy overall. In order to improve this situation, the Australian Government has introduced a range of initiatives intended to increase the supply of affordable housing. One such measure is the Housing Affordability Fund (HAF), launched in September 2008 with the objectives of increasing the supply of new homes, and reducing their costs to home buyers. Through the HAF, the Australian Government planned to make available $500 million over five years to support projects that would encourage best practice in housing development assessment and planning processes, and reduce the cost of infrastructure works associated with housing developments. The savings arising from these projects were to be passed on to home buyers.

20. The signed funding agreements for the 41 HAF projects (worth $301.8 million) that involve infrastructure works require that savings of $133 million be passed on to home buyers.11 Further savings of $5.4 million are required to be passed on to home buyers by one of the eight reform projects (worth $5.7 million) with a signed funding agreement in place. In addition to these savings to home buyers, the funding agreements for the 41 infrastructure projects also require the delivery of a range of capital works and facilities that will be able to be accessed by the broader community. Departmental reports indicated that, by May 2011, the projects funded from the HAF had delivered a range of infrastructure works and a total of $11.9 million in savings to 749 home buyers. With respect to increasing the supply of housing, projects funded from the HAF are expected to bring forward the construction of over 35 000 new homes.

21. Despite these positive early signs of assistance to home buyers and their associated communities, there were serious shortcomings in FaHCSIA’s administration of the program. In particular, the assessment and selection arrangements were not applied consistently. This meant that some proposals that were approved were not selected on a merit basis in accordance with the Government’s policy and the program’s guidelines; conversely, a number of meritorious proposals missed out on being funded. Moreover, the department did not advise the then Minister for Housing about a range of considerations to properly inform her decision-making in relation to funding projects under the program. These shortcomings have detracted from the performance of the program by not treating all applicants equitably, and by providing the responsible Minister with advice that, at times, was incomplete.

22. In administering the program, FaHCSIA conducted two grant funding rounds for the HAF. For the first funding round, FaHCSIA used an automated tool developed by an external firm to help assess the relative merits of the 76 compliant applications against the program’s published selection criteria. However, there was a lack of effective control over the implementation and use of the tool; as a result, several formulaic errors in the tool affected the accuracy of the calculated scores. In turn, these errors affected the accuracy and completeness of the shortlist of proposals recommended to the then Minister. As a consequence, two applications, worth $1.8 million, were incorrectly recommended for advancement to the second stage of the first funding round, and a further seven applications,12 worth $13.6 million, would have been shortlisted had the tool been functioning correctly. Each of the two applications incorrectly recommended for advancement to the second stage were ultimately approved for funding in the first funding round.13

23. In both funding rounds FaHCSIA provided advice to the then Minister that was inconsistent with the stated intention of the HAF as a competitive, merit-based grant program. Specifically, FaHCSIA decided to seek the then Minister’s approval to fund three public housing redevelopment projects, worth $24.4 million, outside of the arrangements established for the HAF’s first funding round. In addition, FaHCSIA decided to moderate the ranking of applications in the second funding round to reflect parity between states, the quantum of funding in particular states, and the mix between reform and infrastructure projects. These decisions were incongruent with the guidelines published for both funding rounds, which stated all applications would be assessed against the selection criteria; that funding would be awarded based on the merits of individual applications; and that there was no specific funding levels for individual states or local government areas. In each case, FaHCSIA’s funding recommendations did not inform the then Minister that the department’s actions were a departure from the program’s approved assessment and selection processes. Further, neither of the two funding recommendations provided to the then Minister in the second funding round contained references to the requirements of the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs) to which the Minister was required to have regard.14

24. Once the then Minister had approved the distribution of funds, FaHCSIA commenced negotiations on the form and content of the funding agreements with the approved projects’ proponents. For the most part, the funding agreements put in place by FaHCSIA contained terms and conditions that were commensurate with the value and scope of the funded projects and that aligned with the objectives of the HAF. However, the funding agreements did not always record the level of savings required to be delivered and the number of affected dwellings. In particular, the funding agreements for some projects do not make clear the level of savings to be passed on to home buyers that will result from the grant provided. This inconsistency potentially increases the risk that the Australian Government will be unable to assess the contribution of the approved projects towards the achievement of the HAF’s objectives. An example of particular note is the funding agreement for the Victorian public housing redevelopment project, which does not quantify the amount of savings to be delivered to home buyers. FaHCSIA estimates that savings from the project will be in the order of $10 million, which represents only 6 per cent of the value of the grant ($159.4 million). In terms of the HAF’s objective of reducing the cost of new homes, this level of savings is very low, particularly when compared with most other HAF infrastructure projects that are required to pass on the full value of their funding to home buyers.

25. FaHCSIA’s arrangements for monitoring the progress of the approved HAF projects against the performance reporting requirements contained in funding agreements were generally sound. In particular, FaHCSIA collected and analysed a range of information on the financial performance and position of the program, including information measuring implementation progress and project outputs. Since taking over administration of the HAF from FaHCSIA, SEWPaC has acknowledged the importance of positioning its monitoring arrangements for the program so that it can assess the full extent of the program’s outcomes when these are realised.

26. The audit findings highlight the importance of agencies assessing the quality of work done on their behalf by third parties (in the case of the HAF, the assessment tool used in the first funding round), and providing comprehensive advice to a grant program’s decision-maker on assessment and selection processes, including making clear whether there have been any departures from approved arrangements. Further, such advice should make appropriate reference to decision maker’s obligations under the Australian Government’s legislative and policy framework for grants administration. The audit also indicates that greater consistency in the content of the HAF’s funding agreements is necessary to support assessments of the contribution of the approved projects towards the HAF’s objectives. The audit has made one recommendation designed to improve the quality of FAHCSIA’s advice to Ministers and other decision-makers on the allocation of grant funding. Two further recommendations are aimed at improving arrangements for managing the performance of the approved projects, now the responsibility of SEWPaC.

Key findings by chapter

The first HAF funding round (Chapter 2)

27. FaHCSIA’s planning and design work leading up to the launch of the first funding round of the HAF was generally sound. In particular, FaHCSIA:

- identified and assessed potential risk factors;

- undertook a series of targeted promotional activities; and

- developed and published guidelines to assist potential applicants.

28. The guidelines, however, had two notable shortcomings. Firstly, the guidelines did not contain information on whether FaHCSIA or the Minister had discretion to waive or amend the published selection criteria, or outline the circumstances in which this may occur.15 Further, the guidelines did not contain information about the funding terms and conditions proposed for the successful projects.

29. FaHCSIA used a spreadsheet-based tool developed by an external firm to determine a score for each of the 76 compliant proposals received in the first funding round. The scores were based on the proposals’ relative merits against the selection criteria contained in the guidelines. Overall, the broad design of the assessment tool was sound, with the key assessment measures in the tool aligning with the selection criteria published in the guidelines. However, there was a lack of effective control over the implementation and use of the tool, and there was no evidence that FaHCSIA properly tested the tool prior to its use, or subjected the results reported by the tool to any quality control measures. As a result, the tool was implemented despite containing several formulaic errors. These errors meant that each of the 76 merit scores calculated by FaHCSIA was incorrect. Based on the corrected merit scores, two projects, worth $1.8 million, were incorrectly included in the shortlist of applications that were recommended to the then Minister for advancement to stage two of the first funding round. A further seven projects, worth $13.6 million, were incorrectly excluded from that shortlist. Each of the two projects incorrectly recommended for advancement to the second stage were ultimately approved for funding in the first funding round.

30. In mid-April 2009, towards the end of the first funding round, FaHCSIA identified a potential shortfall in total expenditure from the HAF for 2008–09. The potential underspend was primarily due to the fact that, at that stage:

- two of the 33 projects shortlisted in the first stage of the assessment process were not approved for funding; and

- FaHCSIA had not completed its assessment of a further four proposals.

31. FaHCSIA outlined five potential options to address the shortfall (see paragraph 14), two of which were recommended as the preferred course of action, to the then Minister. Departmental records indicate that the Minister asked to discuss the department’s recommendations. However, the department did not have any record of the outcome of these discussions. FaHCSIA advised the ANAO that the department approached a number of state and territory housing departments seeking advice on projects that would be ready to be advanced quickly and that were consistent with HAF objectives. As a result, in June 2009, to increase program expenditure prior to the end of 2008–09, FaHCSIA proposed directly funding five public housing redevelopment projects through the HAF along the lines of one of the options previously recommended to the then Minister. On 23 June 2009, the department recommended, and the then Minister approved, funding for three of these projects totalling $24.4 million.

32. Funding these projects was inconsistent with the stated intention of the HAF as a competitive, merit-based grant program. Significantly, FaHCSIA did not assess the relative merits of the projects against the HAF’s published selection criteria, including whether the proposals represented value for money, and did not assess the risks of funding these projects. FaHCSIA’s submissions to the then Minister seeking approval to fund these projects outlined the basis for recommending that the projects be funded, including describing the intended outcomes of each project. However, not all of these benefits aligned with the stated purposes of the HAF. Further, FaHCSIA’s submissions to the then Minister did not make it clear that funding these projects was not consistent with the assessment and selection process set out in the program’s guidelines and communicated to potential applicants and other stakeholders.

33. It was open to FaHCSIA to examine other options to fund these public housing redevelopment projects, such as seeking the then Minister’s approval to vary the program’s published guidelines or to transfer the underspend in the HAF to another, more suitable, program. However, the department did not pursue either of these approaches; rather, it recommended funding projects which did not sit comfortably with the HAF’s stated objectives.

The second HAF funding round (Chapter 3)

34. In August 2009, prior to the commencement of the second funding round, the Australian Government agreed that the then Minister for Housing would provide $175.3 million from the HAF to the Victorian Government to support three public housing redevelopment projects. The decision to fund these three projects from the HAF was made in the context that the Australian Government had announced an equivalent reduction in Victoria’s allocation of funding from the Social Housing Initiative. In the context of the HAF, the Australian Government’ decision was significant as the funds provided to the Victorian Government represent approximately 35 per cent of the total expenditure from the HAF.

35. FaHCSIA advised the then Minister that the department considered the projects were broadly consistent with the HAF’s aims and that the projects aligned with the HAF’s key selection criteria. The signed funding agreement does not stipulate the amount of savings required to be passed on to home buyers from these projects. FaHCSIA estimated that savings to be passed on to home buyers would be in the order of $10 million. In terms of the HAF’s objective of reducing the cost of new homes, the amount of savings is very low compared with the level of funds provided, particularly as most other infrastructure projects funded from the HAF are required to pass on the full value of their funding to home buyers.

36. FaHCSIA redesigned several key elements of the HAF in response to the lessons of the first funding round, including updating the program’s risk register, revising the selection criteria and adopting a single-stage application and assessment process. As was the case in the first funding round, the guidelines for the second funding round did not include information on whether FaHCSIA or the Minister had the discretion to waive or amend the selection criteria, or outline the circumstances in which this might occur. This omission was inconsistent with the requirements of the CGGs, which were promulgated before the round two guidelines were published.16

37. The second HAF funding round was also subject to inconsistent application of the published assessment criteria that had been provided to potential applicants. In determining the list of 49 applications that were recommended for funding in the second funding round, FaHCSIA moderated the ranking of applications to reflect a level of parity between states, the quantum of funding of particular states, and the mix of reform and infrastructure projects. Taking these factors into consideration during the assessment process was not consistent with the program guidelines, which stated that funding would not be allocated to specific states or local government areas; that all applications would be assessed against the selection criteria; and that funding would be awarded based on the merits of individual applications. As a result of the moderation, 14 projects, worth $111 million, initially ranked better than 49th were excluded from the list of recommended projects. While there was some rationale documented for excluding ten of these projects, primarily concerning risk, there was no such rationale for the remaining four projects. Further, although FaHCSIA had informed the then Minister that the initial application rankings had been moderated, the department’s funding advice did not state that this course of action was inconsistent with the program’s guidelines.

38. Neither of the two funding recommendations provided to the then Minister in the second funding round contained references to the requirements of the CGGs to which the Minister was required to have regard. It is expected that departments will include such information in funding recommendations. In particular, paragraph 3.23 of the CGGs requires that Ministers are advised about the requirements of the CGGs in cases where they exercise the role of financial approver.

39. In late March 2010, the then Minister approved eight of the 49 projects initially recommended by FaHCSIA.17 The eight projects selected, worth $50 million, were not the highest ranked projects. Rather, the Minister approved the top ranked project in each state and territory (except Tasmania), as well as the third-ranked project in New South Wales. In this case, there was no evidence that FaHCSIA advised the then Minister of the importance of recording the basis of her decision18 to approve only eight of the 49 projects that the department had recommended. In cases where decision-makers agree with the funding recommendation prepared by a department, they are able, as long as they are satisfied that the department’s assessment was conducted properly, to rely on the assessment as documenting the basis for their decisions. However, when decision-makers do not approve grants that have been recommended by a department it is good practice, particularly in a competitive, merit-based program, to invite decision-makers (including Ministers) to record the basis of their decision to promote transparency and accountability.19

Executing and managing funding agreements (Chapter 4)

40. For the most part, the funding agreements examined contained terms and conditions that were commensurate with the size and nature of the funded projects and that aligned with the objectives of the HAF. In particular, each funding agreement described the HAF’s objectives; the funded project’s goals; measures to assess the performance of the grantee; the payment structures adopted, including the amount and timing of each payment for the grant; and performance and financial acquittal reporting requirements. In most of the examined projects, the funding payment structures adopted, specifically the use of incremental payments to deliver funds rather than large, up-front payments, were appropriate given the risks of the projects and their extended delivery timeframes.

41. Some funding agreements did not clearly set out details of project outcomes in terms of the HAF’s objectives. Specifically, the amount of savings required to be delivered is not quantified in two funding agreements relating to infrastructure projects. Rather, the funding agreements only describe the nature of the savings required to be delivered. Only one of the reform projects’ funding agreements contains information on the number of dwellings expected to benefit, and only four of these funding agreements contain details of the savings required to be delivered. In addition, the frequency of reporting for some projects is low, with an average reporting period of greater than 12 months for some infrastructure projects. There was also considerable variation in the reporting requirements established for reform projects, in particular, the extent to which reform projects are required to report on deliverables. Taken together, these issues mean that the level of savings to be passed on to home buyers is not clear for some projects. This increases the risk that the department will not be able to accurately assess the contribution individual projects make towards the achievement of the HAF’s objectives.

42. FaHCSIA had processes in place for monitoring the progress of the approved projects, including delivery of performance reports against the reporting requirements contained in the funding agreements. For the most part, the performance reports for the examined projects were received in accordance with these reporting requirements. In addition, milestone information relating to the HAF was accurately maintained in FaHCSIA’s online funding management system, although monitoring activity was not always timely.

43. Many of the examined projects were at a relatively early stage in terms of delivering on their expected outcomes. Only one of the infrastructure projects examined has fully met its contracted deliverables. By June 2011, a further four of the infrastructure projects examined were well advanced in terms of delivering the required infrastructure and savings. At the same time, none of the four reforms projects examined had been completed. Submitted performance reports indicate that three of these projects are proceeding in accordance with contracted targets. However, the remaining reform project has yet to deliver the level of savings expected.

Performance reporting (Chapter 5)

44. FaHCSIA developed and reported against a performance measure that was consistent with only one of the HAF’s two objectives, delivering savings to home buyers. At the time that responsibility for the program was transferred to SEWPaC, FaHCSIA had not developed a measure of performance for the other objective, increasing the supply of new houses. SEWPaC’s 2010–11 Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements and its 2011–12 Portfolio Budget Statements include performance indicators designed to address both of the HAF’s objectives.

45. Prior to responsibility for administering the HAF passing to SEWPaC, FaHCSIA was collecting and analysing useful information about the implementation of the HAF, and distributing this information through management reports. These reports included a range of information on the financial performance and position of the program, such as data relating to the budget, expenditure and commitment levels, as well as information relating to the program’s deliverables. These management reports indicate that by May 2011:

- 749 home buyers have received a total of $11.9 million in savings; and

- the construction of over 35 000 new homes was expected to be brought forward.

Summary of agencies’ responses

46. FaHCSIA noted the findings of the report and accepted the recommendation that was directed to it.

47. SEWPaC provided the following summary response to the audit report:

The Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (the department) accepts the key findings and recommendations of the ANAO report and considers that the report provides a constructive basis to strengthen the delivery and performance management of the Housing Affordability Fund.

It is noted that whilst the audit is confined to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs’ administration of the program, the findings are consistent with the actions taken by the department to strengthen delivery and performance management and reporting arrangements since assuming responsibility for the program in October 2010.

48. SEWPaC agreed with the two recommendations in this report that were directed to it.

Footnotes

[1] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Topics @ a Glance – Housing. Sourced from <http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/c311215.nsf/20564c23f3183fdaca25672100813ef1/e14c6280be91d6b2ca257259000b25f0!OpenDocument> [Date accessed: 29 March 2011].

[2] National Housing Supply Council, Second State of Supply Report, April 2010, p.5.

[3] Ibid., pp. 94–100.

[4] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Measuring Australia’s Progress 2010 – Housing, September 2010. Sourced from <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/1370.0~2010~Chapter~Housing%20affordability%20for%20home%20buyers%20(5.4.4)> [Date accessed: 24 March 2011].

[5] Housing Industry Association, Rate Hikes Hit Housing Affordability, February 2011. Sourced from <http://hia.com.au/Latest%20News/Article.aspx> [Date accessed: 24 March 2011].

[6] These mechanisms included listing the number of dwellings to be constructed and the number required to be sold at a reduced price; listing the amount of the reduction (or savings) required to be passed onto home buyers; requiring the gross selling price of each home (that is, before the required reduction) to be determined by independent registered valuers; and defining the categories of eligible purchasers (home buyers).

[7] FaHCSIA anticipated the underspend as it had recommended, and the then Minister had agreed, not to fund two of the 33 proposals advanced to the second stage of the first funding round and, at that stage, it had not completed assessments of a further four proposals.

[8] The actual expenditure shortfall ($24.4 million) was higher then the estimated shortfall ($12 million) advised to the then Minister in mid-April 2009. The difference was principally due to delays in starting several projects as a result of the length of time taken to finalise funding agreements. This issue is discussed in Chapter 4.

[9] The Social Housing Initiative was announced in February 2009 as part of the Nation Building Economic Stimulus Plan. The initiative is designed to assist low-income Australians who are homeless or struggling in the private rental market by providing funding of $5.6 billion (in two stages) for the construction of new social housing and a further $400 million for repairs and maintenance to existing social housing dwellings.

[10] The three projects were bundled together and funded as one HAF project.

[11] The primary reason for the difference between the total funding for the 41 infrastructure projects and the value of the savings to be delivered by those projects is that the amount of savings required to be passed on to home buyers is not quantified in two of those projects’ funding agreements, including the agreement for the Victorian public housing redevelopment project (see paragraph 24).

[12] Three of these applications related to projects located in South Australia, while the other applications related to projects in Tasmania, New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland respectively.

[13] These projects are located in Tasmania and Western Australia.

[14] The CGGs, which were promulgated on 1 July 2009, require that Ministers are advised about these requirements in cases where they exercise the role of financial approver. Department of Finance and Deregulation, Commonwealth Grant Guidelines—Policies and Principles for Grants Administration, Financial Management Guidance No. 23, July 2009, p.11.

[15] In the interests of transparency, accountability and equity, the CGGs, which were not promulgated until after the HAF’s round one guidelines were published, require (on page 29) that a grant program’s guidelines include information about the circumstances in which selection criteria may be waived or amended.

[16] Department of Finance and Deregulation, op. cit., p.29.

[17] FaHCSIA subsequently recommended that the then Minister approve the 30 highest-ranked projects (from the initial list of 49) that the Minister had not approved on 29 March 2010. That funding recommendation outlined to the Minister that 11 of the 49 projects that the department had initially recommended were now unable to be funded as the Australian Government had decided to quarantine $51.9 million from the HAF to support the Council of Australian Governments’ Housing Supply and Affordability Reform agenda.

[18] An enhancement to the Australian Government’s financial management framework on 1 July 2009 means that, as well as recording the terms of their approval (under Financial Management and Accountability Regulation 12), approvers of spending proposal relating to grants must record the basis of their decision.

[19] Australian National Audit Office, Implementing Better Practice Grants Administration, Better Practice Guide, June 2010, pp.81-82.