Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Governance of the Special Broadcasting Service Corporation

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to examine the effectiveness of the governance arrangements for the Special Broadcasting Service Corporation (SBS).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The governing board of a corporate Commonwealth entity is the accountable authority for the entity under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act)1, with responsibility for ‘leading, governing and setting the strategic direction’ for the entity.2

2. Around 60 corporate Commonwealth entities subject to the PGPA Act have governing boards, comprising a total of approximately 510 board positions.3 Corporate Commonwealth entities with governance boards vary significantly by function, and governance boards may also vary in their composition, operating arrangements, independence and subject-matter focus, depending on the specific requirements of their enabling legislation and other applicable laws.

Duties

3. Sections 15 to 19 of the PGPA Act impose duties on accountable authorities in relation to governing the corporate Commonwealth entity for which they are responsible.4 As the accountable authority, members of Commonwealth governing boards are also officials under the PGPA Act and subject to the general duties of officials in sections 25 to 29 of the Act.5 Guidance issued to accountable authorities by the Department of Finance (Finance) observes that ‘each of these duties is as important as the others’.6

Boards and corporate governance

4. Boards play a key role in the effective governance of an entity. Corporate governance is generally considered to involve two dimensions, which are the responsibility of the governing board. These are:

Performance — monitoring the performance of the organisation and CEO …

Conformance — compliance with legal requirements and corporate governance and industry standards, and accountability to relevant stakeholders.

… it is important to understand that governing is not the same as managing. Broadly, governance involves the systems and processes in place that shape, enable and oversee management of an organisation. Management is concerned with doing — with co-ordinating and managing the day-to-day operations of the business.7

Special Broadcasting Service Corporation

5. The Special Broadcasting Service Corporation (SBS) is a corporate Commonwealth entity established under the Special Broadcasting Service Act 1991 (SBS Act) ‘to provide multilingual and multicultural radio, television and digital media services that inform, educate and entertain all Australians, and, in doing so, reflect Australia’s multicultural society’.8

Rationale for undertaking the audit

6. This topic was selected for audit as part of the ANAO’s ongoing audit program that examines aspects of the implementation of the PGPA Act. This audit provides an opportunity for the ANAO to review whether the SBS Board (SBS Board/the Board) has established effective arrangements to comply with selected legislative and policy requirements and adopted practices that support effective governance. The audit also identifies practices that support effective governance that could be applied in other entities. This audit is one of a series of governance audits that apply a standard methodology to the governance of individual boards.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of the governance arrangements for the SBS.

8. The high level criteria for this audit are to examine whether:

- the Board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative and policy requirements;

- the Board has structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance; and

- the Board has implemented fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance/alignment with key legislative and policy requirements.

9. Guidance to boards issued by Finance was reviewed by the ANAO having regard to the report of the 2019 Hayne Royal Commission9, which was released in the course of this audit, and other key reviews of board governance.10

Audit methodology

10. In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- reviewed board and committee papers and minutes from July 2017 to December 2018;

- reviewed a broad range of relevant documentation including corporate plans, strategy documents, board and/or audit committee charters, risk registers and conflict of interest declarations;

- interviewed all current board members; and

- interviewed current members of the management team.

Conclusion

11. The governance and oversight arrangements adopted by the Special Broadcasting Service Corporation (SBS) are effective.

12. The SBS Board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative and policy requirements, and the Board has structured its operations in a manner that supports effective governance.

13. The Board has implemented fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance and alignment with key legislative and policy requirements.

Supporting findings

Design of governance arrangements

14. The design of the SBS Board and committee structure is consistent with legislative and policy requirements.

15. The SBS Board does not have a charter document to articulate governance roles and responsibilities, however the risk associated with this is partially mitigated by the presence of stipulations on the roles and responsibilities of the SBS Board and management contained in the SBS Act and SBS Editorial Guidelines. There is an opportunity to formalise the functions, powers and procedures of the SBS Board through the development and implementation of a Board charter.

16. Review of documentation and interviews with SBS Board members found no indication that the SBS does not meet the legislative requirements for board composition. The composition and experience of the SBS Board is consistent with the SBS’s governance needs. The duration of membership of the SBS Board is legislatively capped to not exceed 10 years. Four of the current members will reach their legislative maximum time in office at the end of their existing appointment.

17. The design of the SBS Board and committee governance arrangements provides for sufficient oversight and challenge over SBS operations. The SBS has implemented a sound approach to promoting the entity’s purpose as set out in the SBS Charter, and to integrating this purpose into the SBS’s operating culture.

Implementation of governance arrangements

18. The flow of information and reporting between the SBS Board and management supports the SBS Board in effectively discharging its governance responsibilities. There are opportunities to improve the level of structure applied to the tracking of Board action items.

19. The SBS Board effectively manages enterprise risk, however the application of the SBS risk management framework could be improved to better support the Board in its identification and treatment of priority risks. The structure of the SBS’s risk management framework addresses all nine elements of the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy. Elements such as risk categories, inherent risk assessment and risk treatment plans are not consistently implemented. Whilst the SBS are generally compliant with Australian Government fraud policy requirements, improvements are required in the linkage of fraud risks to the SBS Fraud Control Plan.

20. An internal audit program has been established to provide assurance over SBS operations. The coverage of the internal audit plan is explicitly targeted at the SBS’s most important risks. Improvements are required in the delivery timeliness of internal audit reports, the clarity of management agreement/disagreement with internal audit recommendations, and in the monitoring of internal audit recommendation implementation.

21. The SBS Ombudsman confirms the adequacy of the SBS’s governance arrangements in relation to Codes of Practice complaints.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.19

The Special Broadcasting Service Corporation establish a Board charter to formalise: the functions, powers, and membership of the board; the roles, responsibilities and expectations of members and of management; the role and responsibilities of the chairperson; procedures for the conduct of meetings; and policies on the ongoing review of board performance.

Special Broadcasting Service Corporation: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.32

The Special Broadcasting Service Corporation review and update its risk framework to better support the Board in the identification and treatment of priority risks.

Special Broadcasting Service Corporation: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

22. The proposed report was provided to SBS which provided a summary response that is set out below. The full response from SBS is reproduced at Appendix 1.

SBS notes the ANAO’s very positive findings that:

- SBS governance and oversight arrangements are effective;

- SBS governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative and policy requirements, and Board operations are structured to support effective governance; and

- the SBS Board has fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance and alignment with key legislative and policy requirements.

SBS is pleased that the ANAO finds, among other things, that the Board has implemented a sound approach to promoting the purpose of SBS as set out in the SBS Charter, and to integrating this purpose into SBS’s operating culture.

SBS notes that the ANAO has made only two recommendations. These relate to the establishment of a Charter for the Board of SBS and the review of SBS’s risk framework in relation to the identification and treatment of priority risks. SBS is taking steps to enhance its governance framework in response to both recommendations.

The Board Charter will provide useful operational guidance to complement the clearly defined set of Board powers and duties prescribed in the Special Broadcasting Service Act 1991.

To date the SBS risk management framework has operated very effectively to mitigate risks of key importance to SBS and its audiences. SBS is, however, always open to making improvements and it will therefore review each element of its risk framework with reference to the ANAO’s observations and findings.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

23. This audit is one of a series of governance audits that apply a standard methodology to the governance of individual boards. The four entities included in the ANAO’s 2018–19 board governance audit series are:

- Old Parliament House;

- the Special Broadcasting Service;

- the Australian Institute of Marine Science; and

- the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust.

24. The first report in this series, Auditor-General Report No. 34 of 2018–19 Effectiveness of Board Governance at Old Parliament House, includes a recommendation directed to the Department of Finance (Finance) to update its guidance to accountable authorities having regard to the key insights and messages for accountable authorities, including governance boards, identified in the recent inquiries and reviews referenced in paragraph 9. Finance agreed with the recommendation.

25. Key messages from the ANAO’s series of governance audits will be outlined in an upcoming ANAO Insights product available on the ANAO website.

1. Background

Introduction

Governance boards

1.1 The governing board of a corporate Commonwealth entity is the accountable authority for the entity under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), with responsibility for ‘leading, governing and setting the strategic direction’ for the entity.

1.2 Around 60 corporate Commonwealth entities subject to the PGPA Act have governing boards, comprising a total of approximately 510 board positions.11 Corporate Commonwealth entities and companies with governance boards vary significantly by function, and governance boards may also vary in their composition, operating arrangements, independence and subject-matter focus, depending on the specific requirements of their enabling legislation and other applicable laws.

Boards and corporate governance

Duties and roles

1.3 As the accountable authority, members of corporate Commonwealth entity governing boards are officials under the PGPA Act and subject to the general duties of officials in sections 25 to 29 of the Act (see Box 1). Sections 15 to 19 of the PGPA Act impose additional duties on accountable authorities in relation to governing the Commonwealth entity for which they are responsible (Box 1).12 Guidance issued to accountable authorities by the Department of Finance (Finance) observes that ‘each of these duties is as important as the others’.13

|

Box 1: Department of Finance, Guide to the PGPA Act for Secretaries, Chief Executives or governing boards (accountable authorities) — RMG 200, December 2016 |

|

General duties as an official You must exercise your powers, perform your functions and discharge your duties:

You must not improperly use your position, or information you obtain in that position, to:

Like all officials, you must disclose material personal interests that relate to the affairs of your entity (section 29) and you must meet the requirements of the finance law. Accountable authorities who do not comply with these general duties can be subject to sanctions, including termination of employment or appointment. General duties as an accountable authority The additional duties imposed on you as an accountable authority are to:

|

1.4 Boards play a key role in the effective governance of an entity. Corporate governance is generally considered to involve two dimensions, which are the responsibility of the governing board:

Performance — monitoring the performance of the organisation and CEO. This also includes strategy — setting organisational goals and developing strategies for achieving them, and being responsive to changing environmental demands, including the prediction and management of risk. The objective is to enhance organisational performance;

Conformance — compliance with legal requirements and corporate governance and industry standards, and accountability to relevant stakeholders.

… it is important to understand that governing is not the same as managing. Broadly, governance involves the systems and processes in place that shape, enable and oversee management of an organisation. Management is concerned with doing — with co-ordinating and managing the day-to-day operations of the business.14

1.5 The relationship between effective corporate governance and organisational performance is summarised in Box 2.

|

Box 2: The relationship between corporate governance and organisational performance |

|

Narrowly conceived, corporate governance involves ensuring compliance with legal obligations, and protection for shareholders against fraud or organisational failure. Without governance mechanisms in place — in particular, a board to direct and control — managers might ‘run away with the profits’. Understood in this way, good governance minimises the possibility of poor organisational performance … more recent definitions of good governance emphasise the contribution good governance can make to improved organisational performance by highlighting the strategic role of the board. Legal compliance, ongoing financial scrutiny and control, and fulfilling accountability requirements are fundamental features of good corporate governance. However, a high-performing board will also play a strategic role. It will plan for the future, keep pace with changes in the external environment, nurture and build key external relationships (for example, business contacts) and be alert to opportunities to further the business. The focus is on performance as well as conformance. The board is not there to simply monitor and protect but also to enable and enhance.15 In summary, research conducted by those working closely with boards suggests that:

|

Culture and governance

1.6 The interplay of the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ attributes of governance — and the criticality of board and organisational culture to an entity’s performance, values and conduct — have been central themes in notable Australian inquiries into organisational misconduct. These have included the 2003 Royal Commission into the failure of HIH Insurance17, the 2018 APRA Prudential Inquiry into the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA)18 and the 2019 Royal Commission into the financial services industry.19 While the specific focus of these inquiries was on financial institutions, their key insights on culture and governance have wider applicability and provide lessons for all accountable authorities, including governance boards. Many Auditor-General Reports have made findings consistent with those appearing in these inquiries.20

2003 HIH Royal Commission

1.7 The HIH Royal Commissioner defined corporate governance as the framework of rules, relationships, systems and processes within and by which authority is exercised and controlled in corporations — embracing not only the models or systems themselves but also the practices by which that exercise and control of authority is in fact effected. Justice Owen observed by way of introduction that:

A cause for serious concern arises from the [HIH] group’s corporate culture. By ‘corporate culture’ I mean the charism[a] or personality — sometimes overt but often unstated — that guides the decision-making process at all levels of an organisation …

The problematic aspects of the corporate culture of HIH — which led directly to the poor decision making — can be summarised succinctly. There was blind faith in a leadership that was ill-equipped for the task. There was insufficient ability and independence of mind in and associated with the organisation to see what had to be done and what had to be stopped or avoided. Risks were not properly identified and managed. Unpleasant information was hidden, filtered or sanitised. And there was a lack of sceptical questioning and analysis when and where it mattered.

At board level, there was little, if any, analysis of the future strategy of the company. Indeed, the company’s strategy was not documented and it is quite apparent to me that a member of the board would have had difficulty identifying any grand design …

… A board that does not understand the strategy may not appreciate the risks. And if it does not appreciate the risks it will probably not ask the right questions to ensure that the strategy is properly executed. This occurred in the governance of HIH. Sometimes questions simply were not posed; on other occasions the right questions were asked but the assessment of the responses was flawed.

1.8 More specifically, Justice Owen reported in chapter 6 of the report — which was dedicated to corporate governance — on key aspects of board operations and the importance of:

- clearly defined and recorded policies or guidelines;

- clearly defined limits on the authority of management, including in relation to staff emoluments;

- independent critical analysis by the board;

- recognition and resolution of conflicts of interest;

- dealing with governance concerns;

- maintaining control of the board agenda; and

- providing relevant information to the board.

2018 APRA Prudential Inquiry

1.9 The APRA Prudential Inquiry also dedicated substantial sections of its report to culture and governance. The review panel observed that:

Culture can be thought of as a system of shared values and norms that shape behaviours and mindsets within an institution. Once established, the culture can be difficult to shift. Desired cultural norms require constant reinforcement, both in words and in deeds. Statements of values are important in setting expectations but their impact is sotto voce. How an institution encourages and rewards its staff, for instance, can speak more loudly in reflecting the attitudes and behaviours that it truly values.21

1.10 The APRA Prudential Inquiry associated weaknesses in board oversight and organisational culture with:

- insufficient rigour and urgency by the Board and its Committees around holding management to account in ensuring that risks were mitigated and issues closed in a timely manner;

- gaps in reporting and metrics hampered the effectiveness of the Board and its Committees; and

- a heavy reliance on the authority of key individuals that weakened the Committee construct and the benefits that it provides.22

2019 Hayne Royal Commission

1.11 The Hayne Royal Commission similarly incorporated a substantial chapter on culture, governance and remuneration in the final report. Commissioner Hayne reported that the evidence before the Commission showed that:

… too often, boards did not get the right information about emerging non-financial risks; did not do enough to seek further or better information where what they had was clearly deficient; and did not do enough with the information they had to oversee and challenge management’s approach to these risks.

Boards cannot operate properly without having the right information. And boards do not operate effectively if they do not challenge management.23

1.12 The Commissioner challenged governance boards to actively discharge their core functions, including the strategic oversight of non-financial risks such as compliance risk, conduct risk and regulatory risk:

Every entity must ask the questions provoked by the Prudential Inquiry into CBA:

- Is there adequate oversight and challenge by the board and its gatekeeper committees of emerging non-financial risks?

- Is it clear who is accountable for risks and how they are to be held accountable?

- Are issues, incidents and risks identified quickly, referred up the management chain, and then managed and resolved urgently? Or is bureaucracy getting in the way?

- Is enough attention being given to compliance? Is it working in practice? Or is it just ‘box-ticking’?

- Do compensation, incentive or remuneration practices recognise and penalise poor conduct? How does the remuneration framework apply when there are poor risk outcomes or there are poor customer outcomes? Do senior managers and above feel the sting?24

1.13 Key observations made in the Hayne Royal Commission on governance boards’ use of information, and the link between culture, governance and remuneration, are summarised in Box 3.

|

Box 3: 2019 Hayne Royal Commission |

|

Information going to boards and its effective use The Royal Commission observed that ‘it is the role of the board to be aware of significant matters arising within the business, and to set the strategic direction of the business in relation to those matters,’25 and identified ‘the importance of a board getting the right information and using it effectively’.26

Culture, governance and remuneration The Royal Commission highlighted the importance of governance boards focusing on entity remuneration policy, because ‘the remuneration arrangements of an entity show what the entity values’.28 The Commission concluded that ‘Culture, governance and remuneration march together.’29

|

Assessment of culture and governance by boards

1.14 Recommendation 5.6 of the Hayne Royal Commission — titled ‘changing culture and governance’ — was that entities should, as often as reasonably possible, take proper steps to: assess the entity’s culture and its governance; identify any problems with that culture and governance; deal with those problems; and determine whether the changes it has made have been effective.

1.15 Underlining the criticality of organisational culture to entity performance, values and conduct, the Royal Commissioner emphasised that this recommendation, ‘although it is expressed generally, can and should be seen as both reflecting and building upon all the other recommendations that I make.’31

1.16 In a similar vein, the HIH Royal Commission had warned in 2003 of the dangers of a ‘tick the box’ mentality towards corporate governance, and the benefits of periodic review by boards of corporate governance practices to ensure their suitability.

The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act)

1.17 The objects of the PGPA Act include: to establish a coherent system of governance and accountability across Commonwealth entities; and to require the Commonwealth and Commonwealth entities to meet high standards of governance, performance and accountability.32

1.18 As discussed in paragraph 1.3 of this audit report, the PGPA Act includes both general duties of accountable authorities and general duties of officials. It also establishes obligations relating to the proper use of public resources (that is, the efficient, effective, ethical and economical use of resources).33 In so doing, the PGPA Act establishes clear cultural expectations for all Commonwealth accountable authorities and officials in respect to resource management. Finance, which supports the Finance Minister in the administration of the PGPA Act framework, has also issued a range of guidance documents on the technical aspects of resource management under the framework.

1.19 Finance issued a Resource Management Guide (RMG 200) in December 2016 to assist accountable authorities34, which is principally a factual and procedural guide with a focus on legal compliance. There is no equivalent in the Commonwealth public sector of resources built up over time — such as the ASX Corporate Governance Council’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations35 and Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) resources — to support public sector governance boards. In consequence, public sector accountable authorities would need to rely on a combination of personal experience and other resources to supplement the guidance released by Finance. As discussed, the recent APRA Prudential Inquiry and Hayne Royal Commission have again highlighted the criticality of effective board governance, corporate culture and the interplay of the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ attributes of governance, and there would be merit in Finance issuing guidance which has regard to the key insights and messages of those inquiries directed to accountable authorities.

Recommendation

1.20 The first report in this series of board governance audits, Auditor-General Report No. 34 of 2018–19 Effectiveness of Board Governance at Old Parliament House, includes a recommendation directed to the Department of Finance to update its guidance to accountable authorities having regard to the key insights and messages for accountable authorities identified in the recent inquiries and reviews referenced above. Finance agreed to the recommendation.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.21 This topic was selected for audit as part of the ANAO’s ongoing audit program that examines aspects of the implementation of the PGPA Act. This audit provides an opportunity for the ANAO to review whether the Special Broadcasting Service Corporation (SBS) Board has established effective arrangements to comply with selected legislative and policy requirements and adopted practices that support effective governance. The audit also identifies practices that support effective governance that could be applied in other entities. This audit is one of a series of governance audits that apply a standard methodology to the governance of individual boards.

1.22 The four entities included in the ANAO’s 2018–19 governance audit series are the:

- Old Parliament House;

- Special Broadcasting Service;

- Australian Institute of Marine Science; and

- the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust.

About the SBS

Legislative environment

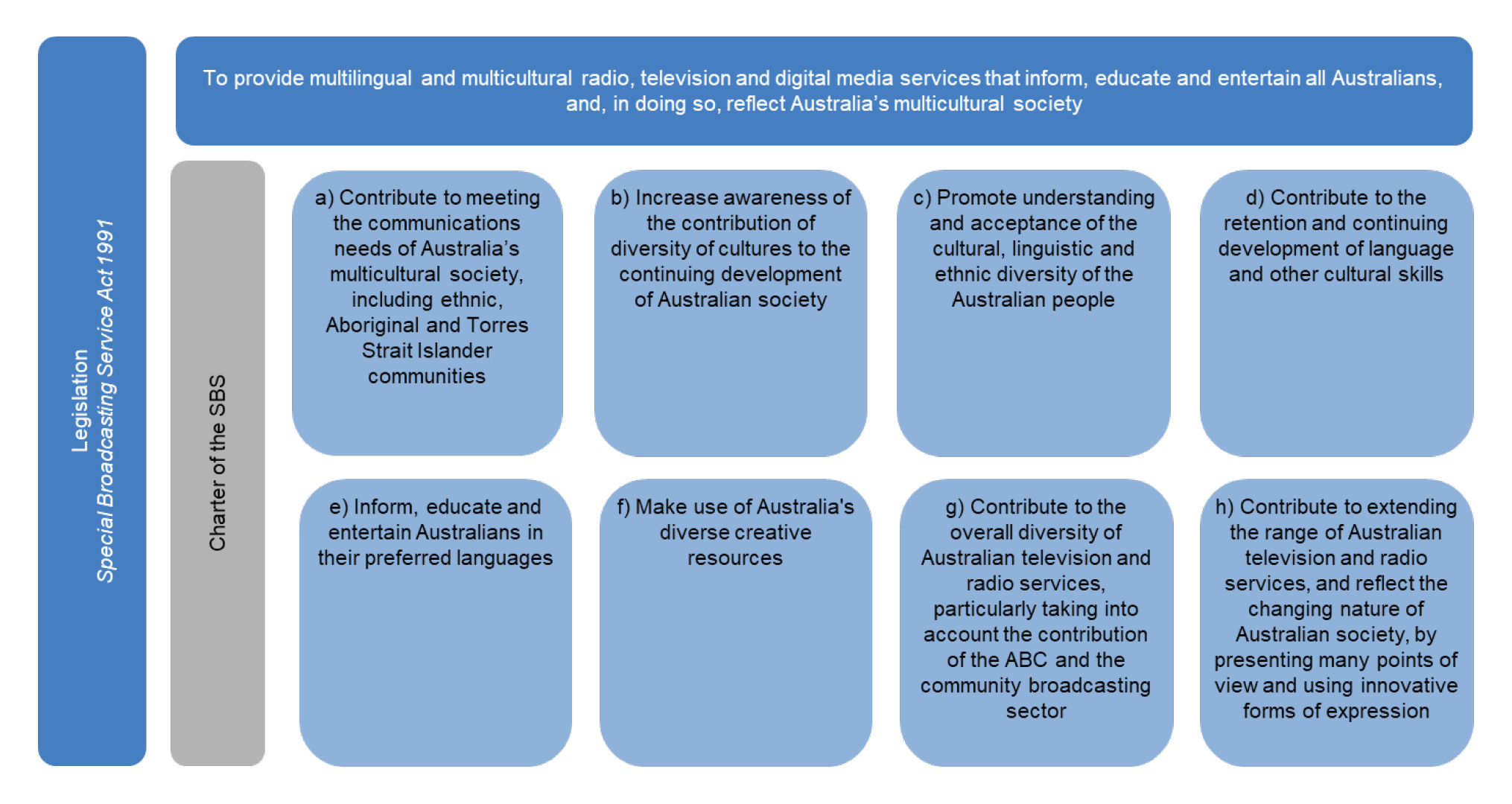

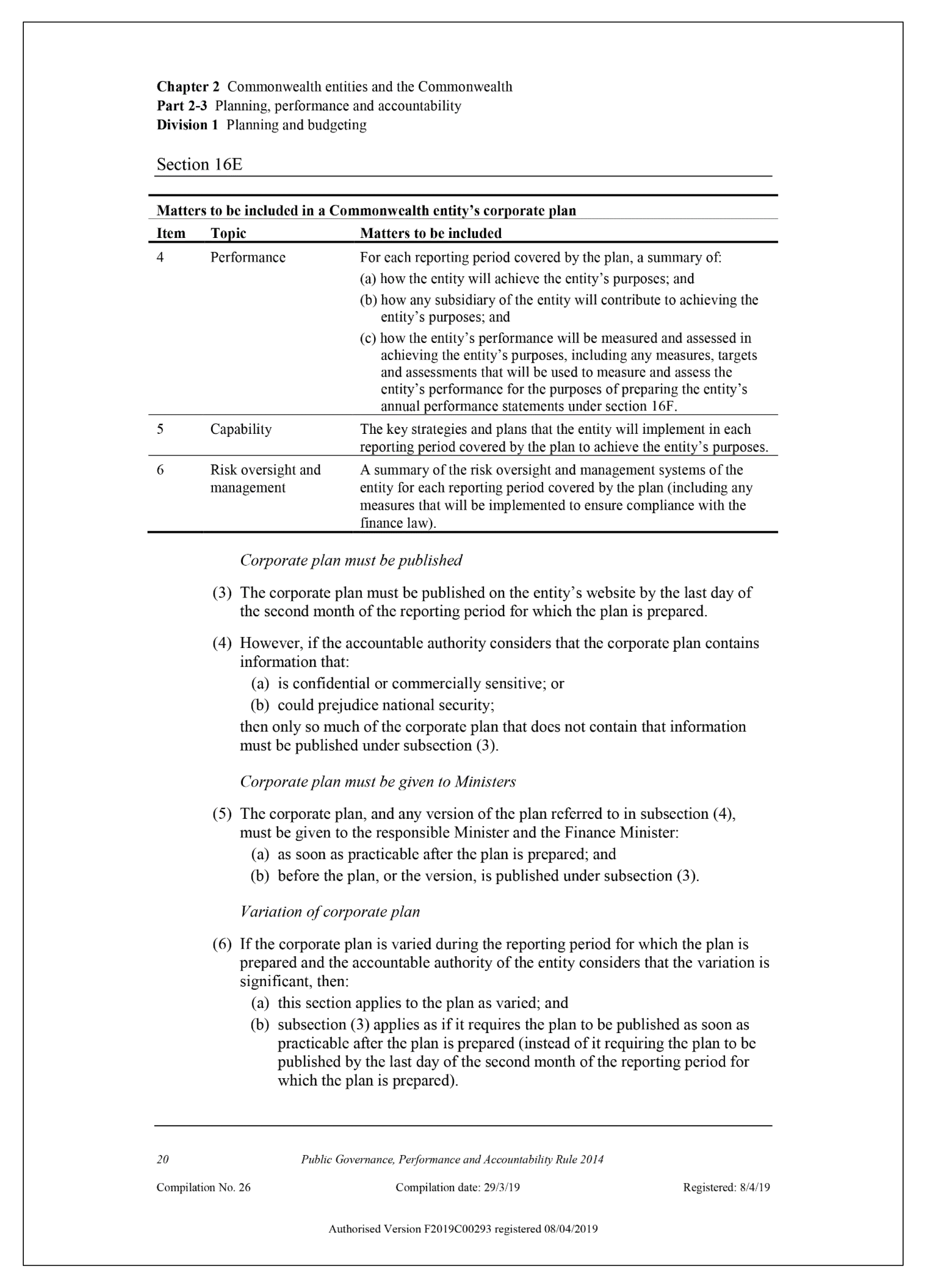

1.23 The responsibilities and obligations of the SBS are articulated in the SBS Charter as set out in section 6 of the Special Broadcasting Service Act 1991 (SBS Act). The SBS Charter states that ‘the principal function of the SBS is to provide multilingual and multicultural radio, television and digital media services that inform, educate and entertain all Australians, and, in doing so, reflect Australia’s multicultural society’.36 The SBS Charter also identifies eight activities that must be performed in discharging its primary function. These are illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Charter of the SBS

Source: ANAO analysis of the SBS Act. The SBS is accountable to the Parliament through a range of obligations including Senate Estimates hearings, Senate Orders and financial and performance reporting requirements.

1.24 The SBS is a Commonwealth corporate entity within the Communications and the Arts Portfolio and is directly accountable to the Minister for Communications and the Arts (the Minister). The Minister may give directions to the SBS Board in relation to the performance of the SBS’s functions. However, the Minister may not give a direction to the SBS in relation to the content or scheduling of programs to be broadcast, or to the content published on a digital media service unless it is in the national interest. In instances where the Minister is of the opinion that the broadcasting of a particular matter by the SBS would be in the national interest, the Minister may direct the SBS to broadcast that matter. In the event that the Minister issues such a direction, the Minister must provide a statement with the particulars of, and the reasons for, the direction to be presented to each House of Parliament.

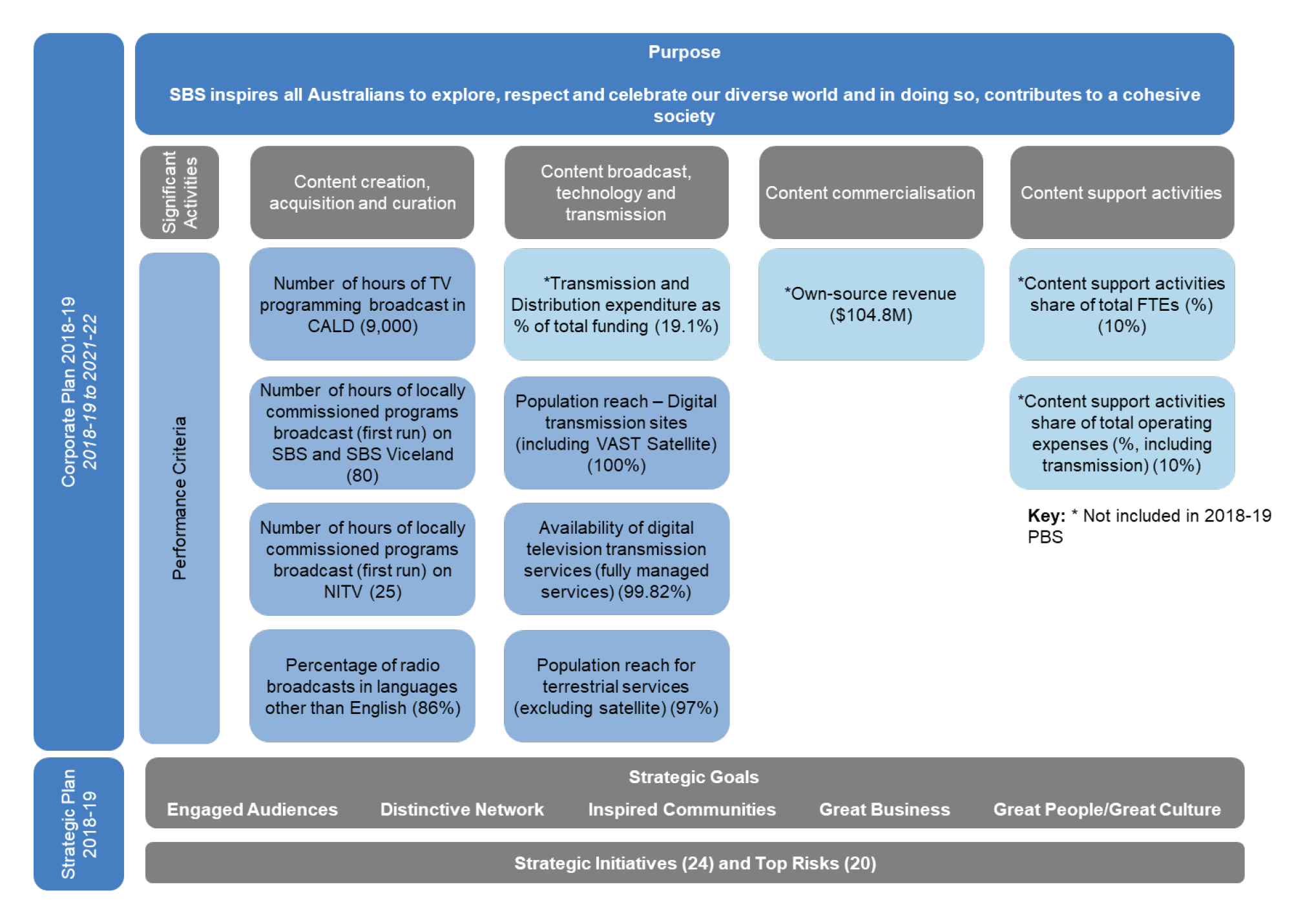

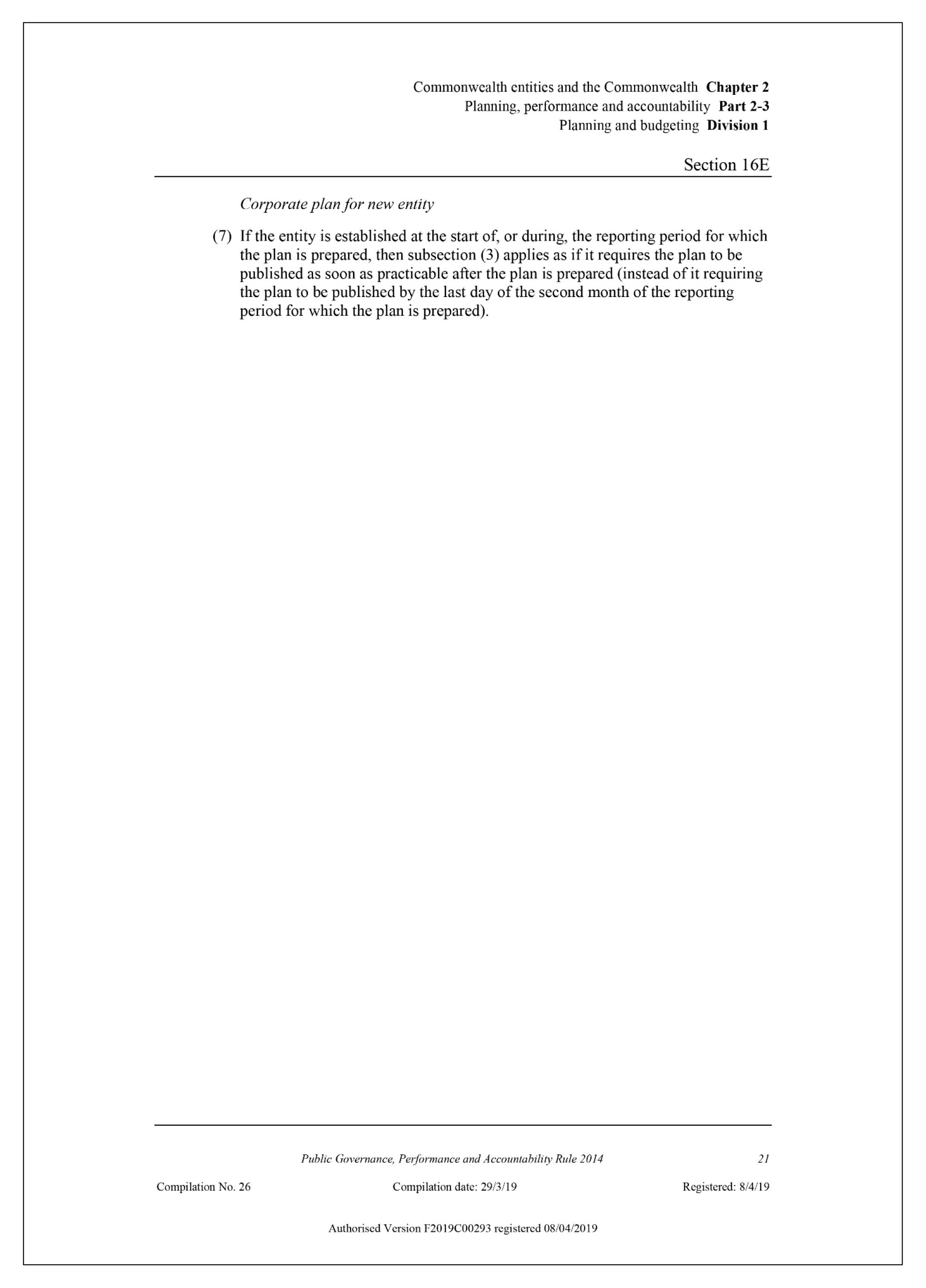

1.25 The 2018–19 Communications and the Arts Portfolio Budget Statements outlines one outcome and two programs to be achieved by the SBS. The stated purpose of the SBS Outcome is that ‘SBS inspires all Australians to explore, appreciate and celebrate our diverse world and in doing so, contributes to a cohesive society’37. This is illustrated below in Figure 1.2, with the associated programs and performance criteria established by the SBS for implementing this outcome.

Figure 1.2: 2018–19 SBS Corporation Budget Statements

Note: The following acronyms were used in the above diagram: CALD — Culturally And Linguistically Diverse; NITV — National Indigenous Television; and VAST — Viewer Access Satellite Television.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2018–19 Portfolio Budget Statements.

1.26 The SBS has a funding model in which approximately 70% of its revenue is received from appropriations within the Communications and the Arts Portfolio. The remaining 30% is generated from own-source revenue, largely from the sale of goods and services, the main component being advertising revenue.

Media industry

1.27 In recent years the SBS has seen changes unfold within the environment in which it operates. The changes and trends observed are consistent with those seen in overseas markets, and the SBS anticipates that current trends will continue.

1.28 The 2018 Department of Communications and the Arts Inquiry into the Competitive Neutrality of the National Broadcasters (the Inquiry) stated that ‘audience fragmentation and the decline in advertising revenue for traditional media have now reached a critical point, and the rapid speed at which these changes are occurring has been overwhelming’.38

1.29 Examples of shifts in the media industry and consumer behaviours identified in the Inquiry that are relevant to the SBS include:

- changing consumer preferences such as for on-demand online services for news, video, podcasts and music;

- shifting preferences of advertisers and media buyers to online advertising channels as opposed to traditional radio and television advertising;

- content providers commissioning original content; and

- increased competition from digital platforms, including international participants.

1.30 Further, the 2018 Digital Platforms Inquiry Preliminary Report conducted by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) stated that there is ‘regulatory disparity between some digital platforms and some more heavily-regulated media businesses that perform comparable functions’.39 The ACCC report identified concerns regarding the advantage digital platforms, such as Facebook and Google, have in attracting advertising revenue due to fewer regulatory restraints. As the SBS sources 30% of its operating revenue from advertising, this increased competition has the potential to impact on the available sources of revenue for the SBS.

Operating environment

1.31 Under section 16E of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule), the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must publish a corporate plan. The corporate plan is the primary planning document of an entity. It sets out the purposes and activities that the entity will pursue and the results it expects to achieve, including explaining the environment and context in which it operates, and its planned performance measures, risk profile and capabilities.40

1.32 The SBS has prepared a 2018–19 SBS Corporate Plan which is a rolling four-year plan supported by an internal strategic planning document outlining five strategic goals for which there are 24 strategic initiatives be to undertaken. This is illustrated in the Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: 2018–19 SBS Corporate Plan and planned performance

Source: 2018–19 SBS Corporate Plan and the SBS Strategic Plan 2018–19.

1.33 The SBS operates four free-to-air TV channels and seven radio stations.. The SBS employs over 1,400 employees under the SBS Act, who are located in Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth. The SBS headquarters is based in Artarmon, Sydney with the other locations providing additional broadcasting facilities and office space. The SBS undertakes filming and production activities all around Australia.

1.34 The net cost of services delivered by the SBS in 2017–18 amounted to $404 million. The SBS received 69.2% of its operating revenue from appropriations, 30.0% from the sale of goods and rendering of services and 0.8% from interest and other sources.

1.35 In 2017–18, SBS provided 284 hours of commissioned first run hours of programming across SBS, SBS VICELAND and NITV. The SBS Network coverage reached 13 million Australians monthly and delivered content in 68 unique languages. The SBS has more languages offered than that of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) combined.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.36 The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of the governance arrangements for the SBS.

1.37 The high level criteria for this audit are to examine whether:

- the Board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative and policy requirements;

- the Board has structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance; and

- the Board has implemented fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance/alignment with key legislative and policy requirements.

1.38 The scope of the audit focussed on whether the SBS is operating in a manner that supports effective governance. This included matters such as:

- SBS Board selection, composition and membership;

- SBS Board operations (quorum etc.) and the operation of sub committees;

- clarity of roles between the Board and management of SBS;

- transparency and accountability in decision making (including arrangements for dealing with conflicts of interest);

- arrangements for assessing Board performance;

- whether the Board has established effective arrangements for monitoring of risk, entity performance, and implementation of audit recommendations; and

- how effectively the SBS Board communicates with the organisation as a whole.

1.39 Guidance to boards issued by Finance was reviewed by the ANAO having regard to the report of the 2019 Hayne Royal Commission41, which was released in the course of this audit, and other key reviews of board governance.42

Audit methodology

1.40 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- reviewed board and committee papers and minutes from July 2017 to December 2018;

- reviewed a broad range of relevant documentation including corporate plans, strategy documents, board and/or audit committee charters, risk registers and conflict of interest declarations;

- interviewed all current board members; and

- interviewed current members of the management team.

1.41 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Audit Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $338,866.

1.42 The team members for this audit were Peter Bell, Susan Ryan, Christian Coelho, Emily Urquhart and Paul Bryant.

2. Design of governance arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the SBS Board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative and policy requirements and whether the Board has structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance.

Conclusion

The SBS Board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative and policy requirements, and the Board has structured its operations in a manner that supports effective governance.

Recommendations

The ANAO has made one recommendation that the SBS implements a formal board charter to improve governance arrangements.

Areas for improvement have been identified in relation to: the implementation of an annual review cycle for relevant committee charters and terms of reference; and the development of a product to enable the Board to formally share its views of any future new board appointments.

Is the design of the SBS Board and committee structure consistent with legislative and policy requirements?

The design of the SBS Board and committee structure is consistent with legislative and policy requirements.

2.1 The SBS Act requires the establishment of a Board of Directors and for the Board to consist of:

- the Managing Director;

- the Chairperson; and

- not fewer than three nor more than seven other non-executive Directors.43

2.2 In addition, section 17 of the SBS Act requires that at least one of the Directors is an Indigenous person.

2.3 The Board membership of the SBS is consistent with these requirements. The SBS Board of Directors comprises the Chairperson, seven other non-executive Directors and the Managing Director. One of the non-executive Directors is an Indigenous person. The SBS Board of Directors is supported by:

- a Community Advisory Committee (as required under subsection 50(1) of the SBS Act);

- three committees — the Audit and Risk Committee (ARC); the Codes Review Committee; and the Remuneration Committee; and

- the Managing Director has established the Executive Committee, which also provides governance support.

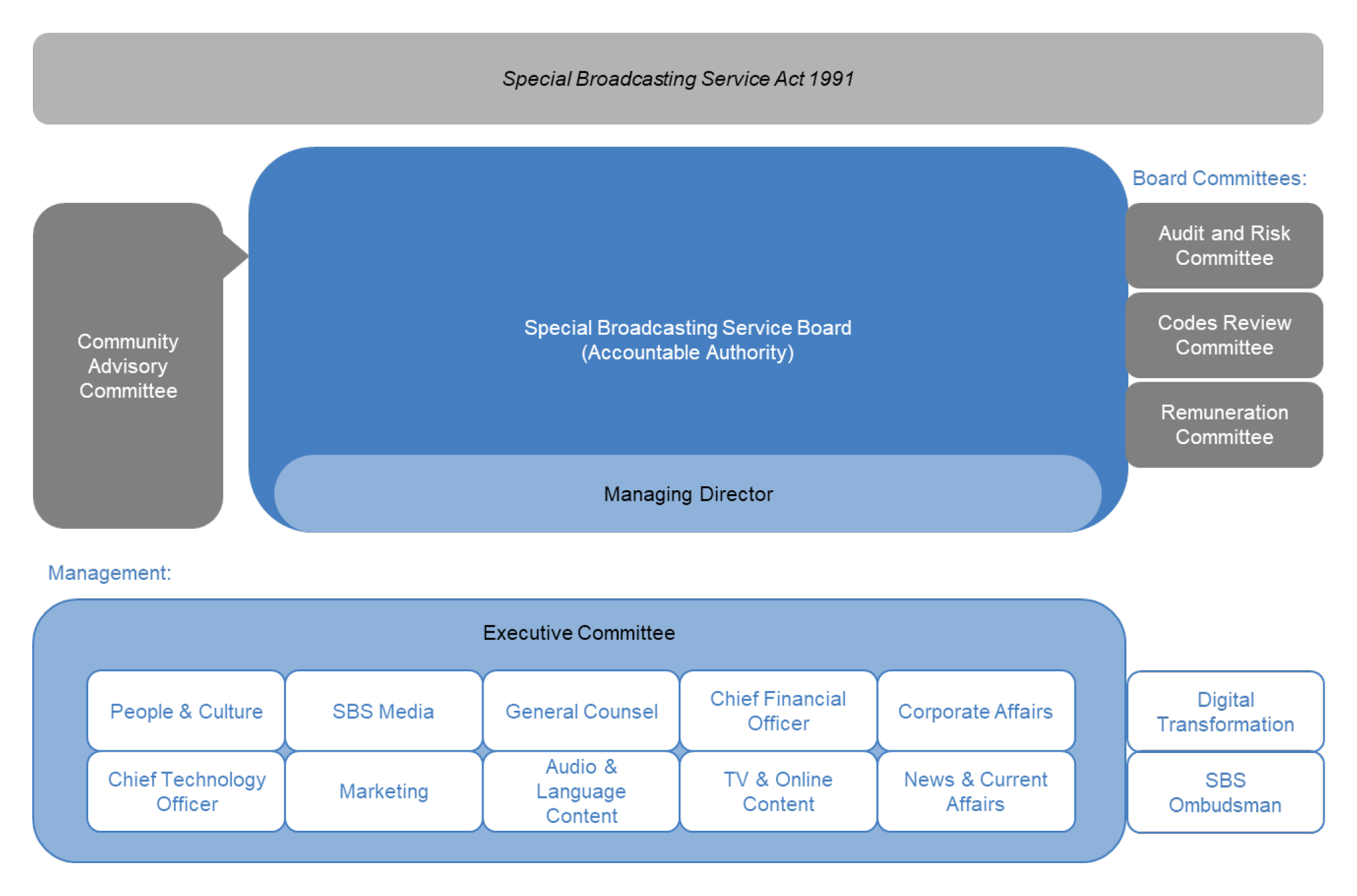

2.4 Figure 2.1 depicts the governance structure of the SBS Board, committees and management.

Figure 2.1: SBS governance structure

Source: ANAO analysis of the SBS governance structure.

2.5 The function of the Community Advisory Committee is ‘to assist the Board to fulfil its duty under paragraph 10(1)(g) of the SBS Act to advise the Board on community needs and opinions, including the needs and opinions of small or newly arrived ethnic groups, on matters relevant to the Charter’.44 The Community Advisory Committee comprises two members of the SBS Board and the remaining eight are community members.

2.6 The Audit and Risk Committee’s objective is to assist the SBS Board in discharging its responsibilities to ensure management has adopted sound, robust and accurate policies and processes in respect of risk oversight, internal control systems, financial and performance reporting, internal audit, external audit and other obligations required under … legislation and better practice guidelines’.45 The membership of Audit and Risk Committee comprises three members of the SBS Board.

2.7 The objective of the Codes Review Committee is to ‘assist the Board in discharging its responsibilities to ensure SBS has developed codes of practice and editorial guidelines relating to programming matters … these responsibilities cover the development of Codes of Practice and Editorial Guidelines’.46 The current SBS Editorial Guidelines have been approved by the Managing Director. The Codes Review Committee comprises three members of the SBS Board.

2.8 The objective of the Remuneration Committee is to assist the Board to:

- discharge its responsibilities to exercise due care, diligence and skill in relation to the Remuneration Policy;

- make recommendations to the Managing Director regarding the remuneration for groups of employees who may impact performance; and

- provide a formal forum for communication between Board and management on talent and succession frameworks, and leadership development activity.

2.9 The Remuneration Committee comprises three members of the SBS Board.

2.10 Seven of the eight non-executive Directors are members of at least one committee. The newest Board member is yet to take on any committee memberships.

2.11 The Board, along with its three standing committees and the Community Advisory Committee, form the key governance structure of the SBS. The governance structure is further supported by management-level committees and governance mechanisms such as the: Executive Committee; SBS Ombudsman; and Head of Digital Transformation. This is illustrated in Figure 2.1 on page 24.

Are the roles and responsibilities of the SBS Board and management appropriately articulated to provide effective governance arrangements?

The SBS Board does not have a charter document to articulate governance roles and responsibilities, however the risk associated with this is partially mitigated by the presence of stipulations on the roles and responsibilities of the SBS Board and management contained in the SBS Act and SBS Editorial Guidelines. There is an opportunity to formalise the functions, powers and procedures of the SBS Board through the development and implementation of a Board charter.

2.12 A board charter is a written document that typically sets out:

- the functions, powers, and membership of the board;

- role, responsibilities and expectations of members, both individually and collectively, and of management47;

- role and responsibilities of the chairperson48;

- procedures for the conduct of meetings49; and

- policies on board performance review.

2.13 The SBS Board does not have a charter. However, the absence of a charter is partially mitigated through the articulation of defined roles and duties under the SBS Act; and in the SBS Editorial Guidelines.

2.14 The SBS Act establishes that the role of the Board is to decide the objectives, strategies and policies to be followed by the SBS in performing its functions, and to ensure that the SBS performs its functions in a proper, efficient and economical manner and with the maximum benefit to the people of Australia.50 Further, the SBS Act sets out the duties of the Board as set out in Box 4.

|

Box 4: Duties of the Board — Section 10, SBS Act |

|

General duties as an official

|

2.15 The SBS Act also states that ‘the affairs of the SBS are to be managed by the Managing Director. In managing any of the affairs of the SBS and in exercising any powers conferred on him or her by this Act, the Managing Director must act in accordance with any policies determined, and any directions given, by the Board’. 51

2.16 In the context of content production and broadcasting responsibilities, the SBS’s Editorial Guidelines, as approved by the Managing Director, state that:

The SBS Board is responsible for the SBS, but is not involved in day-to-day operations. The Managing Director, who is a Board member and the Editor-in-Chief, is responsible to the Board for managing SBS and for all SBS output. The Managing Director delegates various levels of responsibility to employees.

Management is responsible for ensuring that:

- delegations are appropriate;

- there are procedures to deal quickly and efficiently with editorial matters;

- employees are made aware of the SBS Codes of Practice, the SBS Editorial Guidelines, the SBS Accounting Manual and other editorial procedures that apply to them;

- editorial procedures are publicised within the workplace; and

- any changes to procedures and delegations are quickly and clearly communicated to employees.52

2.17 While the delineation of responsibilities between the SBS Board and SBS management for content production is defined within the SBS Editorial Guidelines, it is not set out in any documents with broader application to governance requirements and would be better placed in the context of a board charter.

2.18 Further, SBS guidance does not clearly specify meeting procedures, expectations of secretariat functions, or policies on board performance review — all of which are typically included in a board charter. Better practice guidance recommends that a board charter should be reviewed annually to ‘ensure that the charter is current and raises the directors’ awareness of the organisation’s overall policy framework’.53 Table 2.1 summarises the status of SBS committees’ charters as at November 2018.

Table 2.1: Status of SBS committee charters

|

|

SBS Board |

Community Advisory Committee |

Audit and Risk Committee |

Codes Review Committee |

Remuneration Committee |

Executive Committee |

|

Charter/Terms of Reference (ToR) exists? |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Charter/ToR requires annual review? |

N/A |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

N/A |

|

Charter reviewed within last 12 months? |

N/A |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

N/A |

Source: ANAO analysis of SBS committee charters.

Recommendation no.1

2.19 The Special Broadcasting Service Corporation establish a Board charter to formalise: the functions, powers, and membership of the board; the roles, responsibilities and expectations of members and of management; the role and responsibilities of the chairperson; procedures for the conduct of meetings; and policies on the ongoing review of board performance.

Special Broadcasting Service Corporation response: Agreed.

2.20 SBS agrees with this recommendation and is in the process of developing a Board Charter.

2.21 As at December 2018, the SBS Board has decided to implement a process of annual review for each Board committee to ensure that all committees report consistently. The SBS Board agreed to conduct annual activity reports and perform a charter review for each Board committee in April of each year.

Is the selection, composition and experience of the SBS Board consistent with the governance needs of the SBS?

Review of documentation and interviews with SBS Board members found no indication that the SBS does not meet the legislative requirements for board composition. The composition and experience of the SBS Board is consistent with the SBS’s governance needs. The duration of membership of the SBS Board is legislatively capped to not exceed 10 years. Four of the current members will reach their legislative maximum time in office at the end of their existing appointment.

2.22 The SBS Board is responsible for the selection and appointment of the Managing Director as set out in section 28 of the SBS Act. The Managing Director is a member of the Board and is the only executive member. The Managing Director was appointed by the SBS Board, effective 22 October 2018, pursuant to section 28 of the SBS Act.

2.23 The SBS Act does not place any selection or appointment responsibilities on the SBS Board for the selection of non-executive Directors (including the Chairperson). The Governor-General must appoint the non-executive Directors on the advice of the Minister. The process for the selection and appointment of non-executive Directors is through a Nomination Panel (the Panel) established under the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983.

2.24 The Panel is required to advertise vacancies for the SBS Board and assess applications against merit-based selection criteria as set out in the Special Broadcasting Service Corporation (Selection criteria for the appointment of non-executive Directors) Determination 2013. After the assessment of applications, the Panel is to provide a written report to the Minister on the outcome of the selection process that contains a list of at least three candidates who are nominated for the appointment, and a comparative assessment of those candidates.54

2.25 Following the receipt of the Panel’s report, the Minister may make an appointment recommendation to the Governor-General based on the Panel’s report. Alternatively, the Minister may consider that a person not nominated by the Panel should be appointed. In this situation the Minister is required to give the Prime Minister a written notice specifying the name of that person and the reasons for preferring that person. If that person is so appointed, ‘the Minister must table the reasons for that appointment in each House of the Parliament within 15 sitting days of that House’ after the appointment is made including an assessment of that person against the selection criteria.55

2.26 The Minister can recommend to the Governor-General that an existing board member be re-appointed without the requirement for the Nomination Panel to perform the assessment process.56

2.27 The process for the selection and appointment of a new board member is depicted at Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: SBS Board selection process

Source: ANAO diagrammatic representation of Part 3A, SBS Act.

2.28 Of the non-executive Directors serving on the SBS Board seven of the eight were assessed and shortlisted by the Nomination Panel. One Board member was appointed following the Minister giving written notice to the Prime Minister and tabling the reasons for the appointment in Parliament.

2.29 The composition and experience of the SBS Board is required to meet legislative obligations relating to:

- constitution of the Board;

- requisite skills and experience of non-executive Directors including understanding Australia’s multicultural society, needs and interests of the SBS’s culturally diverse audience, a diversity of cultural perspectives and understanding of the interests of employees; and

- at least one non-executive Director is an Indigenous person.

2.30 Review of documentation and interviews with SBS Board members found no indication that the SBS does not meet the legislative requirements for board composition.

2.31 The duration of term for membership of the SBS Board is legislatively capped to not exceed 10 years. Four non-executive Directors of the SBS Board will reach the maximum period in office within their existing appointment. This is illustrated in the Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: Current SBS Board non-executive Directors term expiry

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.32 The Board’s experience and coverage of legislative requirements is included below as a forward projection of term expiry. Figure 2.4 illustrates that whilst there is appropriate existing coverage of relevant skills and sectors, this coverage should be monitored on an ongoing basis to ensure it remains sufficient.

Figure 2.4: Map of current SBS Board skills coverage

Note: For simplicity, this figure assumes that SBS Board members are not re-appointed at the end of their current term.

Source: ANAO analysis of Board member skills with application to section 17 of the Special Broadcasting Services Corporation Act 1991 and section 4 of the Special Broadcasting Service Corporation (Selection criteria for the appointment of non-executive Directors) Determination 2013.

2.33 Whilst the SBS has no formal role under the legislation in the selection and appointment process for new non-executive Directors to the Board, the views of the current serving Board could provide valuable insight into the desirable skills for any future potential Board members. The 2016 Blackhall & Pearl review of the SBS Board included a skills matrix which the Board provided to the Department of Communication and the Arts to assist in developing its selection criteria for future Board appointments.

2.34 Other corporate Commonwealth entities have developed a skills matrix approach to identify required coverage and any gaps in the skills and experience of their governing bodies. In these instances, the skills matrix was developed with input from the relevant Department with policy responsibility for the entity, the executive and the current serving Board. The development of a skills matrix supports these entities in writing to their relevant Minister with recommendations as to the desired skills and qualifications of new appointments.

2.35 The SBS Board should establish a formal process for the development and provision of a board skills matrix in order to share its views of future requirements for new appointments with the Minister.

Do governance arrangements provide for sufficient oversight and challenge over SBS operations?

The design of the SBS Board and committee governance arrangements provides for sufficient oversight and challenge over SBS operations. The SBS has implemented a sound approach to promoting the entity’s purpose as set out in the SBS Charter, and to integrating this purpose into the SBS’s operating culture.

2.36 The PGPA Act sets out requirements for the governance, reporting and accountability of Commonwealth entities that are imposed on the accountable authority. This includes the general duty to properly govern the Commonwealth entity (section 15).

2.37 Under the PGPA Act, the accountable authority has the flexibility to establish the systems and processes that are appropriate for the entity. Finance guidance provides entities with information on how to meet the various requirements of the PGPA Act and the PGPA Rule including providing examples of how entities may demonstrate compliance.

2.38 Finance’s Resource Management Guide No. 200: Guide to the PGPA Act for Secretaries, Chief Executives and governing boards (RMG 200), provides that to address requirements relating to promoting the proper use and management of public resources57 the accountable authority should establish:

- robust decision-making and control processes for the expenditure of public money; and

- appropriate oversight and reporting to address inappropriate use of resources by officials.

2.39 RMG 200 provides further guidance that in order to promote the achievement of the purposes of the entity58, an accountable authority must:

- set out in the corporate plan the purposes of the entity and the activities the entity will engage in to achieve those purposes (section 35 of the PGPA Act); and

- establish appropriate oversight and reporting arrangements for programs and activities.

2.40 The SBS Board has implemented a sound approach to promoting the purpose of the SBS as set out in the SBS Charter59 and to integrating this purpose into the SBS’s operating culture. The 2018–19 SBS Corporate Plan sets out the purpose that the ‘SBS inspires all Australians to explore, respect and celebrate our diverse world and in doing so, contributes to a cohesive society’, as well as providing the principal function of SBS as set out in the Charter. Internal documents and reports have a clear focus on how individual activities conducted by the SBS will achieve this purpose. The majority of stakeholders interviewed as part of the audit conveyed their role description in terms of how it related to the delivery of the SBS Charter.

2.41 The SBS Board and its committees are the primary mechanisms for oversight of the SBS’s operations. Each committee meets throughout the year to deal with matters relating to their respective charters. Information from the Board committees, including annual performance reports and verbal updates by the relevant Chair of each committee, are provided during Board meetings. Figure 2.5 illustrates the timing of meetings held between July 2017 and October 2018.

Figure 2.5: Timeline of meetings between July 2017 and October 2018

Source: ANAO analysis of the SBS Board and committee meeting minutes.

2.42 Table 2.2 summarises the meeting frequency required of the committees as stipulated by their Charters/Terms of Reference (ToR) and indicates the number of meetings held in the 2017–18 year as published in the SBS 2017–18 Annual Report.

Table 2.2: Committee meeting frequency in 2017–18

|

|

SBS Board |

Community Advisory Committee |

Audit and Risk Committee |

Codes Review Committee |

Remuneration Committee |

Executive Committee |

|

Minimum number of meetings to be held according to Charter/ToR |

N/A |

Not mandated |

4 |

Not mandated |

2 |

N/A |

|

Number of meetings in 2017–18 |

6 |

6 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

19 |

Source: ANAO analysis of SBS committee meetings.

2.43 As depicted in Table 2.2, the Remuneration Committee met once in 2017–18 despite the Remuneration Committee Charter requiring that the committee meet twice annually.

2.44 The SBS Act requires that for a meeting of the Board, a quorum is constituted by five Directors. Review of the minutes for Board meetings held between 30 August 2017 and 25 October 2018 confirmed that there was a quorum constituted for each meeting during this period. The SBS Chairperson was present and presided at all but one meeting. On the one occasion that the SBS Chairperson was not present, the Deputy Chairperson presided over the meeting in line with section 24 of the SBS Act.

2.45 The minutes of the SBS Board meetings indicate that members of the SBS Board make regular enquiries of management on matters relating to operations and strategic initiatives. In the five Board meetings from January 2018 to October 2018, the ANAO noted 25 instances where the Board requested management to provide additional information, presentations or clarification.

2.46 The SBS Board also receives a Managing Director’s report and management reports from each operating division (cleared by the relevant Executive Director). These reports may include presentations by Executive Directors and senior management on key projects, initiatives, programming content and other matters.

2.47 The SBS Ombudsman is an internally appointed position to manage and investigate any complaints which allege that the SBS has breached its Codes of Practice. The SBS Ombudsman reports to the SBS Board each quarter, and annually, on the nature and range of complaints received, and outcomes of investigations conducted. The reports also detail the remedial actions that operating divisions have undertaken in response to identified breaches. The functions of the SBS Ombudsman are addressed in more detail at paragraphs 3.50 to 3.56.

2.48 The oversight of the internal audit program is delegated to the ARC, and minutes of the ARC are presented for noting to the SBS Board. The minutes of the SBS Board meetings noted instances where the Board has requested follow-up information such as internal audit reports and management representations on remedial actions undertaken to address risks. The SBS’s internal audit arrangements are addressed in more detail at paragraphs 3.40 to 3.49.

2.49 The SBS Board has previously engaged consultants and directed management to conduct reviews and evaluations aimed at improving the SBS’s efficiency and effectiveness. These reviews and evaluations have related to process improvement, physical security and Board effectiveness. For example, in 2016 the SBS Board engaged Blackhall & Pearl to assess the effectiveness of the SBS Board (see paragraph 2.32). The implementation of recommendations from the Blackhall and Pearl report is reassessed by the Board periodically.

3. Implementation of governance arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the SBS Board has implemented fit-for-purpose arrangements for oversight of compliance and alignment with key legislative and policy requirements.

Conclusion

The SBS Board has implemented fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance and alignment with key legislative and policy requirements.

Recommendations

The ANAO has made one recommendation to improve the SBS’s risk framework to better support the SBS Board in the identification and treatment of priority risks.

Areas for improvement have been identified in relation to the: tracking of Board action items; linkage between the SBS Fraud Control Plan and the organisational risk register; timeliness of the delivery of internal audit reports; delivery timeliness of internal audit reports, and monitoring of internal audit recommendation implementation.

Does the flow of information and reporting between the SBS Board and management support the SBS Board in effectively discharging its governance responsibilities?

The flow of information and reporting between the SBS Board and management supports the SBS Board in effectively discharging its governance responsibilities. There are opportunities to improve the level of structure applied to the tracking of Board action items.

Sources of information

3.1 The SBS Board has three primary sources of information; reports provided directly by management, reports from its own committees and information provided by the Community Advisory Committee60. Each of the committees has a charter or terms of reference. Review of the agendas and minutes for the committees between February 2017 and October 2018 confirmed that:

- the committees received information from management that addressed the scope of their roles and responsibilities; and

- the committees reported to the Board on how they discharged their roles and responsibilities.

3.2 The charters, terms of reference, agendas and minutes confirm the differences between the committees. The Remuneration Committee and the Codes Review Committee have narrow roles and focussed responsibilities. This is reflected in their charters, meeting frequency and reporting. The Audit and Risk Committee (ARC) has a significant function encompassing ‘risk oversight, internal control systems, financial and performance reporting, internal audit and external audit and performance.’ The span of responsibility and the technical nature of some of its functions is reflected in the structure and management of its meetings and reporting to the SBS Board. The Community Advisory Committee has a more indistinct role and it has adopted a more consultative approach to its work, meeting structure and reporting.

Board papers

3.3 The SBS Board meets every second month. Board papers are prepared by management and circulated electronically in advance of the meeting.

3.4 Over the eight Board meetings between 30 August 2017 and 25 October 2018, the SBS Board papers averaged 469 pages in length, and ranged between 292 pages and 754 pages. The breakdown of the contents of the Board papers is illustrated in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: SBS Board paper length

Note: The SBS Annual Report, including financial statements and performance statements, is presented to the Board in the August 2018 meeting for approval and sign-off in line with requirements under the PGPA Act.

Source: ANAO analysis of SBS Board Papers.

3.5 The 2016 Blackhall & Pearl review of the SBS Board’s effectiveness recommended that reducing the detail in Board papers could improve the ‘clarity of insights, comparability between meetings and reduce the overall volume of papers’. The review also noted that analytical commentary should be insightful and on point. An ANAO review of Board minutes and interviews with each Board member identified concerns over the efficacy of Board papers. These concerns have previously been raised in Board meetings and are being progressively addressed.

3.6 A Board paper summarising the actions arising from previous meetings is created for inclusion and noting at each Board meeting, however this reporting did not reflect the completion status or implementation timeframe for actions arising from Board meetings. For Board meetings between August 2017 and October 2018, all action items were recorded as ‘noted’. There was one instance where a Board member raised a concern that an action item had been incorrectly marked as ‘complete’.

3.7 Where the completion of an action was marked with a date within the action paper, it was found that the average time to complete an action was 55 days. Most completed actions were completed two weeks prior to the Board meeting in which they fell due.

3.8 Analysis of minutes and action papers indicates that there were six actions noted within the Board meeting minutes that did not appear within the corresponding actions paper, and of the 52 action items that were included within the actions paper across five Board meetings, three actions were not formally marked as ‘complete’ and did not appear again in future action papers. It is unclear if these actions were ever completed. The SBS Board should monitor all items on the actions list until it is advised by management that they are completed.

3.9 Review of committee meeting documentation identified instances of errors in dating, version control and finalisation/authorisation of documents.

3.10 The SBS was unable to locate final/approved versions of the following key documents and reports:

- Operations Excellence 2016 Business Area Review: Audio and Language Content Workflow Efficiency Review;

- Operations Excellence February 2017 Business Area Review: NITV Operations Review;

- Operations Excellence October 2017 Business Area Review: World News: Digital Workflow Review; and

- Operations Excellence December 2017 Business Area Review: Marketing Evolution Review: Workflow Review.

3.11 As at December 2018, the SBS management advised that it had specified page limits for Board papers and templates and management of action items were being refined to improve consistency. The SBS Board also approved a forward calendar of Board papers to align divisional reports with operational timelines and to ensure that each division reports to the Board at least annually.

Compliance Reporting

3.12 The SBS has established a legislative compliance reporting process wherein compliance with statutory obligations is monitored and reported to the ARC on a quarterly cycle. The SBS has listed the key legislative instruments which govern its operations within a document titled ‘Compliance Universe’. A review of the Compliance Universe against mandatory requirements of the SBS Act identified the following requirements which do not appear to be monitored or reported on:

- under section 36 of the SBS Act, ‘the Managing Director must give written notice to the Chairperson of all direct and indirect pecuniary interests that the Managing Director has or acquires in any business or in any body corporate carrying on any business’. On 14 December 2018, the SBS provided evidence of the disclosure made by the current Managing Director on 12 December 2018. The current Managing Director was acting in this position from 2 October 2018 and was formally appointed by the Board to commence the position effective 22 October 2018. No declarations of interests for previous managing directors were provided.

- under subsections 45(5) and 45A(3) of the SBS Act, the Board must ensure that advertising and sponsorship guidelines are included in the corporate plan61 prepared by the Board. The 2018–19 SBS Corporate Plan refers to the advertising and sponsorship guidelines as contained in Code 5 of the SBS Codes of Practice and Guideline 5.5 of the SBS Editorial Guidelines, however the guidelines were not directly included within the 2018–19 SBS Corporate Plan. As at 20 December 2018, the corporate plan was updated to contain hyperlinks to the SBS Codes of Practice and SBS Editorial Guidelines.

Audit and Risk Committee Papers

3.13 The ARC paper length averages 238 pages with an average meeting duration of 73 minutes. This is illustrated in Figure 3.2. The SBS’s internal audit arrangements are detailed in paragraphs 3.40 to 3.49.

Figure 3.2: ARC papers and meeting duration

Source: ANAO analysis of Agenda Sheets contained within the ARC papers.

Does the SBS Board effectively manage enterprise risk?

The SBS Board effectively manages enterprise risk, however the application of the SBS risk management framework could be improved to better support the Board in its identification and treatment of priority risks. The structure of the SBS’s risk management framework addresses all nine elements of the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy. Elements such as risk categories, inherent risk assessment and risk treatment plans are not consistently implemented. Whilst the SBS are generally compliant with Australian Government fraud policy requirements, improvements are required in the linkage of fraud risks to the SBS Fraud Control Plan.

3.14 Section 16 of the PGPA Act details the accountable authority’s duty to establish and maintain systems relating to risk and control. The ANAO’s assessment of the SBS Board’s requirement to establish appropriate systems of risk management and internal control is set out in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Duty to establish and maintain appropriate systems relating to risk management and oversight and internal controls (PGPA Act, section 16)

|

Requirements or suggested practices |

ANAO observations |

|

To address requirements relating to risk management and oversight entities can:

|

The SBS established a risk management framework, last approved by the Board in August 2018. The framework states that the SBS Board is responsible for defining risk appetite, and that risk appetite and tolerance levels will be reviewed annually as part of the SBS Strategic Risk review. Board meetings include risk management as a standing agenda item within the Director’s Report and information on risk is included throughout Board papers. The SBS Board meetings include a report on the activities of the ARC. The SBS has established financial delegations, last approved by the Managing Director in November 2018. They relate to banking, borrowing, indemnities, spending approval, entering into contracts, and other items. The SBS Board established the ARC with a Charter that is required to be reviewed and approved by the Board annually. The ARC Charter was most recently reviewed and approved by the Board in April 2018. The ARC reviews the appropriateness of the SBS’s systems of risk oversight and management and internal controls and provides assurance to the Board. The ARC receives reporting on the SBS’s compliance mechanisms through reporting on the SBS’s Compliance Universe which, inter alia, documents compliance against the PGPA Act and other legislative requirements. The SBS has a Fraud Control Policy and framework dated June 2017. At the time of audit fieldwork, the policy was current and reflected that the primary responsibility for fraud rested with the Chairperson of the SBS Board as the accountable authority. The ARC Charter includes reference to fraud within the context of risk and the review and approval cycles are the same as for all categories of risk. |

Source: ANAO analysis of the Department of Finance, Resource Management Guide No. 200 Guide to the PGPA Act for Secretaries, Chief Executives or governing boards (accountable authorities), engaging with risk and establishing controls section, https://www.finance.gov.au/resource-management/accountability/accountable-authorities/ [accessed 22 February 2019].

3.15 The SBS governance arrangements for risk management are set out in its SBS Risk Management Plan. At a summary level, the governance responsibilities are set out in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: Primary governance responsibilities for risk management

|

Governance level |

Governance responsibilities |

|

The SBS Board |

The Board has primary responsibility for the Risk Management Framework, including risk strategy and risk policy. The Board determines the SBS risk appetite and tolerance. |

|

The Audit and Risk Committee (ARC) |

The ARC has responsibility for monitoring the effectiveness of the SBS Risk Management Framework and oversight of the management of key risks. |

|

The Managing Director |

The Managing Director is responsible for ensuring that the risk management systems operate effectively and that risks are managed, and weaknesses identified and remediated. The Managing Director has responsibility for applying the SBS Risk Appetite Statements and in building a risk aware culture in the SBS. |

Source: ANAO analysis of SBS Risk Management Plan

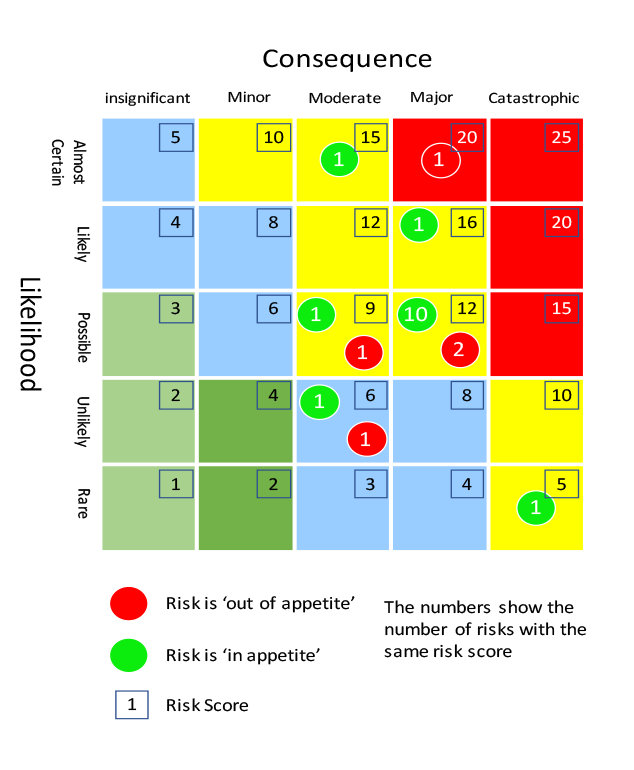

3.16 The SBS has implemented a risk management framework which encompasses inherent and residual risks, a risk profile, a risk matrix and risk appetite statements. The assessment of risk is semi-quantitative, relying on the multiplication of likelihood and consequence scores to obtain an overall risk score.

3.17 The SBS Organisational Risk Register has a total of 201 risks. The largest number of risks are in the Technology (23), Finance (27) and News and Current Affairs (21) risk categories.

3.18 Of the 201 risks identified in the Organisational Risk Register, 86 are rated as ‘High’ and three rated as ‘Very high’. To assist with prioritising risk treatments for residual risks, the SBS has developed Risk Appetite Statements for the various categories of risks in its risk register. The Risk Appetite Statements express the SBS’s level of tolerance for risks within each of its defined risk categories. The combination of the risk score and SBS’s appetite for the category of the risk determine whether it should be treated and, to some extent, the resources that should be devoted to the treatment of the risk.

3.19 Finance has issued policy and guidance for risk management frameworks. This has two major elements, the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy 62 and guidance for risk management frameworks63. The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy has nine elements:

- establishing a risk management policy;

- establishing a risk management framework;

- defining responsibility for managing risk;

- embedding systematic risk management into business processes;

- developing a positive risk culture;

- communicating and consulting about risk;

- understanding and managing shared risk;

- maintaining risk management capability; and

- reviewing and continuously improving the management of risk.

3.20 The structure of the SBS’s risk management framework addresses all nine elements of the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy. Notwithstanding, three issues were identified in relation to information in the SBS’ risk management framework:

- framework documentation indicates that the SBS will use inherent risk as one of its assessments, however there was no record of any inherent risk assessments;

- the definitions of risk categories were applied inconsistently between the SBS Risk Management Plan and Organisational Risk Register. The combination of the risk category and the assessed risk level determines whether the risk is within or out of risk appetite; and

- the SBS Risk Management Plan and the risk matrix are contradictory in that the SBS Risk Management Plan identifies risks as ‘Very high’ if their risk score is greater than 16. The risk matrix does not follow this approach and identifies some risks as ‘Very high’ with scores less than 16.

Strategic risk management

3.21 Each year the SBS develops its ‘Top risks’ to focus its strategic risk treatment and planning. In 2018 the SBS identified 19 ‘Top risks’ and subsequently added an additional risk to the list. In line with the SBS Risk Management Plan requirements all ‘Top risks’ have treatment plans.

3.22 The SBS has adopted a consultative approach to the identification of strategic risks and the alignment of its strategic priorities to these risks. At this strategic level, the approach adopted by the SBS provides for a transparent and coordinated approach to strategic risk management.

3.23 The 20 ‘Top risks’ comprise: one ‘Very high’ risk; 17 ‘High’ risks; and two ‘Medium’ risks.

3.24 Further, the 20 ‘Top risks’ comprise 15 risks recorded in the Organisational Risk Register as being ‘in appetite’ and five as ‘out of appetite’.

3.25 The characteristics of the ‘Top risks’ are illustrated in Figure 3.3, which highlights the risk position on the SBS risk matrix, whether the risk is ‘in appetite’ or ‘out of appetite’ and the number of risks with the same characteristics.

Figure 3.3: Assessed levels of the ‘Top risks’

Source: SBS data.

3.26 Effective risk management involves a combination of the outputs of the mechanical aspects of the risk framework with the considerations of the Board and senior management to identify those risks that are the most important to the organisation. The mechanical outputs of the risk framework in the SBS require substantial moderation by the Board and senior management. For example, SBS’s 20 ‘Top risks’ as determined by the Board:

- includes 15 risks assessed as ‘in appetite’;

- includes 2 medium risks;

- excludes 2 very high risks; and

- excludes 1 high risk assessed as ‘out of appetite’.

3.27 The Board and senior management are required to make decisions about the risks facing the SBS, however, the existing risk framework could be improved to better support that decision-making.