Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Governance of Climate Change Commitments

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- In 2022, the Australian Government increased Australia’s commitments to reduce emissions and limit the impact of climate change under the Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- Meeting Australia’s climate change commitments requires a well planned, coordinated approach to action across government, industry, and community.

- The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) is responsible for leading the national effort on climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, policies, and activities.

Key facts

- Australia’s legislated commitments are to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 43 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030.

What did we find?

- DCCEEW has partly effective arrangements supporting the implementation of the Australian Government’s climate change commitments.

- Key components including national plans, strategies, and frameworks are yet to be delivered for use.

- DCCEEW reports annually on progress towards targets, however are unable to demonstrate the extent to which specific Australian Government policies and programs have contributed or are expected to contribute towards overall emissions reduction.

What did we recommend?

- There were five recommendations to DCCEEW aimed at developing a strategic approach to enable measurement of activities to the achievement of Australia’s climate change commitments; and effectively managing risk, communication, and records.

- DCCEEW agreed to all five recommendations.

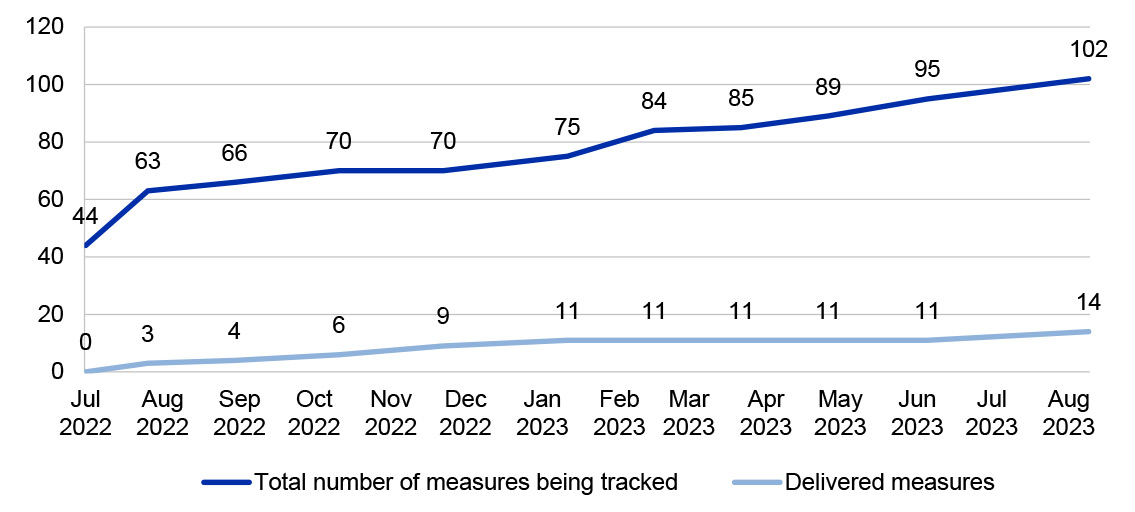

102

measures

measures currently being tracked by DCCEEW as part of its key climate change and energy program of work.

42%

reduction

reduction on 2005 greenhouse gas emission levels by 2030 projected under the ‘additional measures’ scenario of DCCEEW’s 2023 emissions projections.

$2.68bn

allocated in the October 2022–23 Budget to measures that were originally identified in the Powering Australia Plan.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The United Nations defines climate change as long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns that can be natural but are increasingly driven by human activities.1

2. Actions to address climate change risk fall into two broad categories: mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation involves limiting changes to the climate by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Adaptation involves adjusting systems to anticipate and respond to climate and its effects, both to moderate harm and to exploit beneficial opportunities. The latest synthesis report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states that climate resilient development involves both adaptation and mitigation.2

3. The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) was formed on 1 July 2022. DCCEEW is the entity leading and delivering the Australian Government’s agenda across climate change, energy, the environment, heritage, and water.

4. DCCEEW’s purpose as it relates to climate change is to ‘drive Australian climate action [and] transform Australia’s energy system to support net zero emissions while maintaining its affordability, security and reliability’. DCCEEW is responsible for matters relating to the development and coordination of domestic and international climate action, policy, strategy, and reporting.

5. In September 2022, the Australian Parliament passed two pieces of legislation that formalised Australia’s updated commitments to reduce emissions under the Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).3 The updated commitments were to:

- achieve net zero emissions by 2050 (net zero by 2050); and

- reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 43 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030 (2030 target).4

Rationale for undertaking the audit

6. Since May 2022, the Australian Government has made organisational and structural changes reflecting its investment in climate change policy matters. There are many stakeholders across government, industry, and the community that have interests in DCCEEW’s effective management and delivery of this body of work.

7. This audit provides assurance to Parliament on the effectiveness of DCCEEW’s governance arrangements supporting the implementation of the Australian Government’s climate change commitments, including its arrangements to assess and measure implementation, coordination, risk management, and performance.

Audit objective and criteria

8. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water’s governance arrangements supporting the implementation of the Australian Government’s climate change commitments.

9. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted.

- Are there appropriate risk-based oversight arrangements and management strategies?

- Have effective coordination arrangements been established?

10. The audit focused on DCCEEW’s arrangements for effective strategic oversight and coordination of climate policies to meet Australia’s overarching commitments, including DCCEEW’s consideration of available emissions data and risk in the planning and delivery of climate change policy and programs.

11. The audit did not assess Australia’s accounting and reporting of past and future emissions.5 The audit also did not assess the design of all climate policies and mechanisms, including offsetting, related compliance and regulatory activities, and underlying scientific research.

Conclusion

12. DCCEEW’s governance arrangements to support the implementation of the Australian Government’s climate change commitments are partly effective with some components including national plans, strategies, and frameworks yet to be delivered. DCCEEW reports annually on progress towards targets, however is unable to demonstrate the extent to which specific Australian Government policies and programs have contributed or are expected to contribute towards overall emissions reduction.

13. DCCEEW has partly appropriate oversight arrangements and risk management strategies to support the Australian Government’s climate change commitments. DCCEEW established governance arrangements for oversight of its Powering Australia program of work and provides support for other cross-portfolio arrangements in climate- and energy-related work intended to achieve Australia’s climate change commitments. DCCEEW’s internal governance arrangements include a project board that examines implementation risk for high priority measures in the Powering Australia program of work. DCCEEW has not delivered planned climate risk strategies and frameworks for use by Australian Government entities, including by DCCEEW in its own business.

14. DCCEEW has established partly effective coordination and reporting arrangements. Cross-entity coordination arrangements and activities provide information on measures within the Powering Australia program of work, however DCCEEW cannot demonstrate that arrangements are fulfilling their intended role. Arrangements for managing stakeholder coordination and communication for the Powering Australia program of work have not yet been finalised. DCCEEW utilises existing arrangements for reporting national progress on climate change, which occurs on an annual basis. This reporting occurs at a high, aggregate level. There is no consolidated policy- and program-level reporting on progress, evaluation, and decision-making across the Powering Australia program of work.

Supporting findings

Oversight and risk

15. There is no overarching strategy supporting the management of the Powering Australia program of work. DCCEEW is continuing to develop and refine its approach to supporting the achievement of Australia’s climate change commitments. DCCEEW’s climate and energy work is intended to underpin the achievement of the Australian Government’s commitment to reduce emissions. National plans and frameworks are intended to be developed to support DCCEEW’s strategic approach to defining and delivering results and objectives in the context of Australia’s climate change commitments. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.28)

16. DCCEEW established departmental oversight arrangements for the Powering Australia program of work. Interdepartmental oversight arrangements and roles continue to evolve while an increasing number of measures are added to the program of work for DCCEEW to monitor. DCCEEW has adjusted some of its arrangements in response to changes to the broader governance structure across the climate and energy agenda. An assessment of the effectiveness of the arrangements is limited by the availability of records across governance bodies and oversight mechanisms. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.40)

17. DCCEEW established its enterprise risk management frameworks and procedures in March 2023, nine months after the entity was formed. There has been no reassessment of the Powering Australia program of work against the new framework. In May 2023, DCCEEW established a project board to assess and consider implementation risk to projects within the Powering Australia program of work. This board has considered 12 high priority projects in the delivery stage as of October 2023. (See paragraphs 2.43 to 2.61)

18. Whole-of-government initiatives led by DCCEEW to produce information to support climate risk-based decision-making have commenced. The Climate Impact Statements program to assess climate risk in new policy proposals is being piloted, with further decisions about its implementation across all Australian Government entities to be determined. The National Climate Risk Assessment methodology has been delivered, with a first pass assessment due in December 2023. The Climate Risk and Opportunity Management Program has yet to deliver planned items for use by Australian Government entities. (See paragraphs 2.64 to 2.78)

Coordination and reporting

19. Cross-entity arrangements for coordination and reporting are focused on information sharing at a measure level for the Powering Australia program of work. DCCEEW does not use its cross-entity coordination arrangements to identify conflicts and duplication of effort across the Powering Australia program of work. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.17)

20. A stakeholder engagement plan has been in draft since January 2023 and an interdepartmental working group to streamline external stakeholder communication has been established. DCCEEW coordinates with state and territory governments through the Energy and Climate Change Ministerial Council, which is a continuation of a long-standing intergovernmental arrangement. (See paragraphs 3.18 to 3.47)

21. Reporting across the broader climate and energy portfolio includes technical information, project implementation, and progress towards climate change targets and commitments. DCCEEW continues to meet its climate commitment reporting requirements under international frameworks. This reporting does not demonstrate the contribution of DCCEEW’s management of the Powering Australia program of work to Australia’s climate change commitments. (See paragraphs 3.48 to 3.111)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.29

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water develop a strategic framework for the delivery of the Powering Australia program of work that enables measurement of activities to the achievement of Australia’s climate change commitments.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.41

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water develop and implement an information assets management policy consistent with the Archives Act 1983 and supporting policies to ensure that records are complete and accurate.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.62

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water manage and coordinate risk assessment and treatment across the Powering Australia program of work to ensure risk is understood and addressed at both program and enterprise levels.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.34

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water finalise the Powering Australia communication and stakeholder engagement plan and clarify roles, responsibilities, and outcomes for stakeholder coordination and communication to inform effective consultation processes.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.112

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water use its reporting to demonstrate that its management of climate and energy work clearly contributes to achieving Australia’s climate change commitments including the contribution to emissions reduction.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the department) agrees with the ANAO audit’s five recommendations. Implementation of the recommendations has commenced. This work will form part of the department’s efforts to further improve and mature the existing governance arrangements established in relation to risk, information management, reporting, and the coordination of stakeholder engagement and communication. Implementation will be overseen by the department’s Audit Committee.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy/program implementation

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The United Nations defines climate change as long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns that can be natural but are increasingly driven by human activities.6

1.2 Actions to address climate change risk fall into two broad categories: mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation involves limiting changes to the climate by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Adaptation involves adjusting systems to anticipate and respond to climate and its effects, both to moderate harm and to exploit beneficial opportunities. The latest synthesis report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states that climate resilient development involves both adaptation and mitigation.7

1.3 In September 2022, the Australian Parliament passed two pieces of legislation that formalised Australia’s updated commitments to reduce emissions under the Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).8 The updated commitments were to:

- achieve net zero emissions by 2050 (net zero by 2050); and

- reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 43 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030 (2030 target).9

1.4 The updated commitments relate to mitigation as they are focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Role of the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

1.5 The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) is the entity leading ‘the integrated delivery of the Government’s agenda across climate change, energy, the environment, heritage, and water.’10 DCCEEW’s purpose as it relates to climate change is to ‘drive Australian climate action [and] transform Australia’s energy system to support net zero emissions while maintaining its affordability, security and reliability’.11

1.6 DCCEEW is responsible for managing climate change and energy matters relating to:

- development and coordination of domestic, community and household climate action;

- climate change adaptation strategy and coordination;

- coordination of climate change science activities;

- development and coordination of international climate change policy;

- international climate change negotiations;

- greenhouse emissions and energy consumption reporting;

- greenhouse gas abatement programmes;

- energy policy, including the national energy market, energy-specific international obligations and activities, and energy efficiency including industrial energy; and

- renewable energy, including policy, regulation, coordination, and technology development.12

1.7 DCCEEW’s 2023–24 Corporate Plan states that DCCEEW ‘lead[s] the implementation of the Government’s Powering Australia Plan’.13 The Powering Australia Plan ‘focused on creating jobs, cutting power bills and reducing emissions by boosting renewable energy’ and included commitments to increase renewable energy supply, support new, clean energy options such as electric vehicles and solar batteries, and make changes to Australia’s domestic and international approaches to climate issues.14

1.8 Measures described in the Powering Australia Plan form the basis of DCCEEW’s ongoing Powering Australia program of work. The Powering Australia program of work includes other climate- and energy-related measures relating to climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience. There were 15 measures that were originally described in the Powering Australia Plan that were allocated funding in the October 2022–23 Budget, with a total value of $2.68 billion across several portfolio entities.

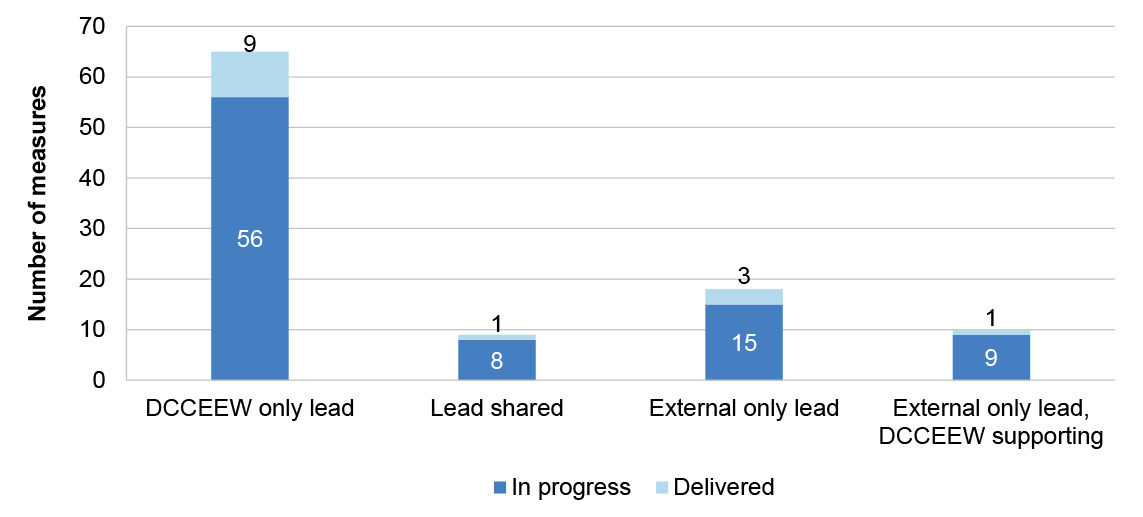

1.9 As of September 2023, DCCEEW is monitoring more than 100 measures as part of the Powering Australia program of work, 14 of which DCCEEW has reported as delivered (see Appendix 3). Measures being tracked are those being delivered solely by DCCEEW; by DCCEEW in connection with another Australian Government entity or entities; and by another Australian Government entity or entities without DCCEEW.

1.10 There are several intra- and inter-governmental, and whole-of-government arrangements in place to manage and deliver the Powering Australia and other climate- and energy-related priorities and work set by the Australian Government.15

1.11 DCCEEW is responsible for capturing the effort of all Australian Government portfolios and jurisdictions in implementing climate-related priorities and work, including as part of the Powering Australia program of work.

International reporting framework and requirements

1.12 In 2015, the Australian Government signed the Paris Agreement under the UNFCCC.16 The Paris Agreement was the first universal, legally binding climate change agreement, which would attempt to limit global warming to well below two degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels.

1.13 As a Party to the Paris Agreement, Australia is required to submit to the UNFCCC:

- a nationally determined contribution (NDC) every five years to communicate actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and build resilience to adapt to climate change17;

- a National Communication every four years and a biennial report every two years18, which must include emissions projections; and

- an annual national greenhouse gas emissions inventory.19

1.14 Australia has submitted inventories and estimates of its past emissions to the UNFCCC since 1994.20 Australia’s latest National Inventory Report for 2021, submitted in April 2023, was the first developed and submitted under Paris Agreement rules for emissions inventory reporting.21 The emissions projections report for 2022 was published in December 2022. The emissions projections report for 2023 was published in December 2023.22

Australia’s updated climate change commitments

1.15 In June 2022, the Australian Government submitted an updated NDC to the UNFCCC with the net zero by 2050 and 2030 targets.23 The 2030 target of 43 per cent below 2005 levels is an increase on the 26–28 per cent emissions reduction target included in Australia’s 2021 update to the original NDC.

1.16 In September 2022, the Australian Parliament passed two pieces of legislation that formalised Australia’s updated commitments to reduce emissions under the Paris Agreement of the UNFCCC.24 The Climate Change Act 2022 (Climate Change Act) and Climate Change (Consequential Amendments) Act 2022 formalise the two overarching emissions reduction targets in legislation.

1.17 The Climate Change Act establishes that the 2030 target is to be implemented as both a ‘point target’ (by 2030) and an ‘emissions budget’ (total quantity emitted). The emissions budget covers the period 2021 to 2030.

1.18 The Climate Change Act requires the Minister for Climate Change to prepare and table an Annual Climate Change Statement in Parliament. The Annual Climate Change Statement includes information on progress towards emissions reduction targets. The first Annual Climate Change Statement was tabled in Parliament in December 2022.

1.19 The Climate Change Act requires the Climate Change Authority (CCA) to provide advice relating to the Annual Climate Change Statement to the Minister for Climate Change, including advice on greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets to be included in a new or adjusted NDC. The CCA’s advice must be tabled in Parliament. The CCA’s advice in the form of the Annual Progress Report was tabled at the same time as the first Annual Climate Change Statement in December 2022.

1.20 In early December 2023, the Minister for Climate Change tabled the second Annual Climate Change Statement and the CCA’s Annual Progress Report.25 These documents coincided with the release of the emissions projections report for 2023 (see paragraph 1.14).

Status of climate change targets and commitments

1.21 Australia’s emissions projections for 2022 indicated that Australia is projected to achieve a 32 per cent reduction on 2005 levels by 2030.26 The 2022 projections note that there is a ‘with additional measures’ scenario under which Australia is projected to achieve a 40 per cent reduction on 2005 levels by 2030.27

1.22 In its first Annual Progress Report published in November 2022, the CCA noted that ‘Achieving net zero emissions by 2050 will require a plan that carefully sequences a combination of actions to mitigate and sequester carbon emissions across the whole economy.’28 In the same report, the CCA also noted that ‘To meet its ambitious new targets, Australia will need to decarbonise at an average annual rate of 17 Mt CO2-e per year, more than 40 per cent faster than it has since 2009.’29

1.23 Australia’s emissions projections for 2023 indicate that Australia is projected to achieve a 37 per cent reduction in emissions on 2005 levels by 2030.30 The 2023 projections note that there is a ‘with additional measures’ scenario under which Australia is projected to achieve a 42 per cent reduction on 2005 levels by 2030.31

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.24 Since May 2022, the Australian Government has made organisational and structural changes reflecting its investment in climate change policy matters. DCCEEW leads the development, coordination, and implementation of domestic and international climate action, policy, and strategy, including reporting that demonstrates Australia’s progress on the achievement of climate change commitments. There are many stakeholders across government, industry, and the community that have interests in DCCEEW’s effective management and delivery of this body of work.

1.25 This audit provides assurance to Parliament on the effectiveness of DCCEEW’s governance arrangements supporting the implementation of the Australian Government’s climate change commitments, including its arrangements to assess and measure implementation, coordination, risk management, and performance.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.26 The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water’s governance arrangements supporting the implementation of the Australian Government’s climate change commitments.

1.27 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted.

- Are there appropriate risk-based oversight arrangements and management strategies?

- Have effective coordination arrangements been established?

1.28 The audit focused on DCCEEW’s arrangements for effective strategic oversight and coordination of climate policies to meet Australia’s overarching commitments, including DCCEEW’s consideration of available emissions data and risk in the planning and delivery of climate change policy and programs.

1.29 The audit did not assess Australia’s accounting and reporting of past and future emissions.32 The audit also did not assess the design of all climate policies and mechanisms, including offsetting, related compliance and regulatory activities, and underlying scientific research.

Audit methodology

1.30 The audit methodology included:

- examination of documentation relating to governance arrangements, communication and coordination of efforts, and reporting that establishes or supports Australia’s progress on meeting its climate change commitments;

- examination of publicly available information relating to international reporting frameworks; and

- meetings with relevant departmental staff.

1.31 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $377,212.

1.32 The team members for this audit were Sam Khaw, Jemimah Hamilton, Hayley Pang, Jacqueline Hedditch, and Corinne Horton.

2. Oversight and risk

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) has appropriate risk-based oversight arrangements and management strategies.

Conclusion

DCCEEW has partly appropriate oversight arrangements and risk management strategies to support the Australian Government’s climate change commitments. DCCEEW established governance arrangements for oversight of its Powering Australia program of work and provides support for other cross-portfolio arrangements in climate- and energy-related work intended to achieve Australia’s climate change commitments. DCCEEW’s internal governance arrangements include a project board that examines implementation risk for high priority measures in the Powering Australia program of work. DCCEEW has not delivered planned climate risk strategies and frameworks for use by Australian Government entities, including by DCCEEW in its own business.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations for DCCEEW to develop a strategic framework for the delivery of the Powering Australia program of work that enables measurement of activities to the achievement of Australia’s climate change commitments; develop and implement an information assets management policy to ensure that records are complete and accurate; and manage and coordinate risk assessment and treatment across the Powering Australia program of work to ensure risk is understood and addressed at both program and enterprise levels.

2.1 Fit-for-purpose arrangements to support the delivery of strategies, policies and programs include:

- identification and clear delineation of roles and responsibilities;

- a strategic approach to support the immediate and ongoing achievement of objectives and delivery of results;

- processes to keep senior management and ministers informed of challenges and changes; and

- ongoing assessment and consideration of risk.

Does DCCEEW have a fit-for-purpose strategy supporting the management of its program of work?

There is no overarching strategy supporting the management of the Powering Australia program of work. DCCEEW is continuing to develop and refine its approach to supporting the achievement of Australia’s climate change commitments. DCCEEW’s climate and energy work is intended to underpin the achievement of the Australian Government’s commitment to reduce emissions. National plans and frameworks are intended to be developed to support DCCEEW’s strategic approach to defining and delivering results and objectives in the context of Australia’s climate change commitments.

Plans to achieve Australia’s climate change commitments

2.2 The United Nations notes that ‘building climate resilience requires combining mitigation and adaptation actions to tackle the current and future impacts of climate change’.33 There are multiple national plans and strategies for mitigation and adaptation in place, dating back to 2018. There are also plans and strategies currently in development.

2.3 DCCEEW is responsible for developing national climate plans and strategies. These collectively support Australia’s achievement of its climate change commitments by setting out the policies, programs, and actions required to mitigate and adapt to the changing climate.

National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy 2021–2025

2.4 The National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy 2021–2025 (NCRAS) was released in 2021. The NCRAS has three objectives relating to climate adaptation in Australia, to:

- drive investment and action through collaboration;

- improve climate information and services; and

- assess progress and improve over time.34

2.5 The NCRAS states that the Australian Government will:

- provide enhanced national leadership and coordination;

- partner with governments, businesses and communities to act and invest;

- deliver coordinated climate information and services to more users;

- continuing [sic] to deliver world class climate science that informs successful adaptation;

- deliver national assessments of climate impacts and adaptation progress; and

- independently assess progress over time.35

2.6 The DCCEEW webpage notes that the NCRAS ‘outlines how the Australian Government will fulfil its 2012 COAG Roles and Responsibilities’. The NCRAS states that the Climate Change Authority (CCA) will be tasked with assessing implementation of the NCRAS as part of ‘[monitoring] and independently [evaluating] progress over time’.36 The NCRAS was released prior to the introduction of the Climate Change Act 2022 (Climate Change Act). The CCA’s role under the Climate Change Act does not include monitoring or evaluating the progress of the NCRAS.37

2.7 DCCEEW advised the ANAO that actions proposed in the NCRAS are not being monitored as many are now being tracked as key commitments of the Australian Government in the Powering Australia Tracker (see Chapter 3, paragraphs 3.71 to 3.93). The NCRAS is intended to be superseded by a new National Adaptation Plan.

National adaptation planning

2.8 Under the Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Parties to the agreement shall ‘as appropriate, engage in adaptation planning processes…’. Adaptation planning processes may include developing and implementing a national adaptation plan, and each Party should submit communications about adaptation activities to the UNFCCC.38 Australia has not previously submitted a national adaptation plan to the UNFCCC.39

2.9 DCCEEW is commencing the development of a National Adaptation Plan (NAP). The DCCEEW website states that the NAP ‘will be the first truly national plan in Australia and will provide a basis for fulfilling the Australian Government’s role of providing national strategic leadership on climate adaptation.’40

2.10 DCCEEW advised the ANAO that the NAP is due to be published by the end of 2024. The DCCEEW website states that the NAP will use the National Climate Risk Assessment (see paragraph 2.76) ‘to build an agreed, nationally consistent pathway that prioritises Australia’s adaptation actions and opportunities. It will provide guidance on the national response, including how we adapt to the risks, scale up our adaptation efforts and build our national resilience to climate impacts.’

Australia’s Long-term Emissions Reduction Plan

2.11 Australia’s Long-term Emissions Reduction Plan was published in October 2021. This plan was to support Australia’s achievement of net zero emissions by 2050 through a ‘technology based approach’.41

2.12 In its first Annual Progress Report finalised in November 202242, the CCA noted that it was important that the Australian Government commence planning for ‘net zero by 2050’.43 The Australian Government accepted this advice in the first Annual Climate Change Statement tabled in December 2022.44

Sectoral plans

2.13 Australia’s emissions inventory reporting categorises emissions by sector according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change guidelines.45 These are Energy; Industrial processes; Agriculture; Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry; and Waste. Australia’s National Inventory Report for 2021 noted that Energy sector emissions were the largest proportion of Australia’s emissions in 2020–21, with Agriculture sector emissions the second largest.46

2.14 In July 2023, the Minister for Climate Change and Energy announced that sectoral decarbonisation plans would be developed to support the development of an updated net zero by 2050 plan. The six plans announced are to cover the Electricity and Energy; Industry, including waste; the Built Environment; Agriculture and Land; Transport; and Resources sectors.

2.15 Governance arrangements for the net zero sectoral plans were developed in August 2023. The arrangements are intended to progress the practical development of the sectoral plans, with strategic oversight, project tracking, and decision-making provided by senior officials. Each plan is intended to be co-authored by DCCEEW and the responsible portfolio entity or entities and sponsored by the relevant minister, with the lead drafter to be agreed between the co-authoring entities.

2.16 High-level oversight of plan development is intended to be provided by the Net Zero Senior Officials Committee and the Net Zero Secretaries Committee, with the plans to be put to the Net Zero Economy Committee of Cabinet for consideration (see Table 2.1). The CCA has been asked to provide advice on the pathways to net zero to support development of the plans, and on the 2035 target.47

2.17 The Minister for Climate Change and Energy stated that the sectoral plans will ‘feed in’ to the new net zero by 2050 plan and Australia’s 2035 target.48 The 2035 target will be set in Australia’s next submitted NDC in 2025 (see paragraph 1.13). The sectoral plans and the updated net zero by 2050 plan are to be delivered by the end of 2024.

Powering Australia

2.18 The Powering Australia Plan ‘focused on creating jobs, cutting power bills and reducing emissions by boosting renewable energy’49 and included commitments to increase renewable energy supply, support new, clean energy options such as electric vehicles and solar batteries, and make changes to Australia’s domestic and international approaches to climate issues. The DCCEEW website refers to ‘The Australian Government’s Powering Australia plan’ as one of Australia’s energy strategies and frameworks.50

2.19 DCCEEW advised the Australian Government on the implementation of measures identified in the Powering Australia Plan and provided advice on Australia’s emissions profiles and trends. However, advice to the Australian Government did not include specific emissions reduction modelling of the projected impact of the Powering Australia Plan, with DCCEEW noting that ‘we will work with you to better understand the projected impact of the Powering Australia plan.’

2.20 Measures in the Powering Australia Plan are in four categories.

- Electricity — including installation of community batteries, funding for solar banks and upgrades to Australia’s electricity grid.

- Industry, carbon farming and agriculture — including funding of and from the Powering the Regions Fund and National Reconstruction Fund, reform of the Safeguard Mechanism, review of the integrity of Australian Carbon Credit Units, and upskilling the workforce.

- Transport — including introduction of an Electric Car Discount, consultation on the National Electric Vehicle Strategy, and funding to establish a real-world vehicle testing program.

- National leadership — including restoring the role of the Climate Change Authority, building an Australian National Prevention and Resilience Framework, and commissioning an urgent climate risk assessment.

2.21 DCCEEW advised the ANAO that ‘Powering Australia’ is ‘a brand used by the Government to communicate its program of work’. DCCEEW advised the ANAO that categories from the Powering Australia Plan align with the areas of focus set out in the Ministerial Charter Letter sent to the Minister for Climate Change and Energy by the Prime Minister in July 2022.

2.22 The Climate Change Act requires the Minister for Climate Change to prepare and table an Annual Climate Change Statement to Parliament. The statement is informed by independent advice from the CCA and is to include information on progress towards emissions reduction targets. In the first Annual Climate Change Statement tabled in December 2022, the Australian Government stated that ‘with full implementation of Powering Australia, we are confident we will achieve 43% emissions reduction by 2030.’51

2.23 In the October 2022–23 Budget, the Australian Government announced that the ‘The Powering Australia Plan will establish a modern energy grid, driving innovation and opening up new energy industries and delivering cleaner, cheaper energy for families, households and businesses. It will also reduce emissions across the economy’.52 DCCEEW advised the ANAO that it does not use the Powering Australia Plan as an organising concept for its work.

2.24 In its first annual progress report, the CCA reported that ‘since 2009, Australia has decarbonised its economy at an average annual rate of 12 Mt CO2-e per year’53 and the ‘rate of change needs to accelerate to reach our 2030 and 2050 targets’.54 Further, ‘The Government will need to deliver on its Powering Australia plan and more if Australia’s targets and commitments are to be met’.55

2.25 ANAO analysis found that 16 measures that were originally described in the Powering Australia Plan were measures that were allocated funding in the October 2022–23 Budget with a total value of $2.68 billion.

- Eight measures had ‘Powering Australia’ in the title, five of which were in the Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water portfolio.56

- The other eight measures do not have ‘Powering Australia’ in the title although the ANAO consider that these measures were originally described in or are broadly consistent with measures described in the Powering Australia Plan.

2.26 In DCCEEW’s monitoring of progress of climate- and energy-related work, DCCEEW identifies which measures being monitored are election commitments (see Appendix 3). This monitoring does not include an indication of what contribution measures will make towards emissions reduction targets.

2.27 ‘Powering Australia’ is used by the Australian Government and DCCEEW to refer variously to election commitments, measures funded in the Budget, and other climate- and energy-related measures and actions across portfolios. Powering Australia is not a single structured ‘plan’ or strategy that links the activities being undertaken to the achievement of emissions reduction targets.

2.28 In the absence of a single plan or strategy, DCCEEW is not well placed to assess the impact of the list of Powering Australia measures or its efforts within the climate change and energy portfolio of work towards Australia’s climate change targets and commitments.

Recommendation no.1

2.29 The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water develop a strategic framework for the delivery of the Powering Australia program of work that enables measurement of activities to the achievement of Australia’s climate change commitments.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

2.30 The Government has a clear strategy to: decarbonise the electricity sector (82 percent renewables by 2030); enable the electrification of other sectors (such as the National Electric Vehicle Strategy); reduce the emissions from major industrial facilities (such as the Safeguard Mechanism); and provide flexibility and incentives for further action through high integrity carbon credits. Reporting of progress towards the clear, time bound target of 43% below 2005 levels of emissions by 2030 occurs through the Annual Climate Change Statement to Parliament, the Climate Change Authority’s Annual Progress Report, Australia’s annual Emissions Projections Report and the annual and quarterly updates to the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory. The department agrees developing a framework to map specific measures to the strategy will aid transparency of progress.

Has DCCEEW established effective oversight arrangements for its program of work?

DCCEEW established departmental oversight arrangements for the Powering Australia program of work. Interdepartmental oversight arrangements and roles continue to evolve while an increasing number of measures are added to the program of work for DCCEEW to monitor. DCCEEW has adjusted some of its arrangements in response to changes to the broader governance structure across the climate and energy agenda. An assessment of the effectiveness of the arrangements is limited by the availability of records across governance bodies and oversight mechanisms.

2.31 In October 2022, the Australian Government determined that a whole-of-government approach was necessary to achieve Australia’s legislated climate change targets. Each minister is responsible for reducing emissions within their respective portfolios.

Whole-of-government structure and oversight

2.32 The Powering Australia governance structure was established in October 2022, following establishment of the Net Zero Economy Ministerial Steering Committee (the Steering Committee).57 The Steering Committee was to direct the work of the Net Zero Economy Taskforce58 on the Taskforce’s work in ‘[building] regional communities’ capacity to adapt to structural change from decarbonisation’. The Steering Committee would also undertake broader strategic discussions on climate action.

2.33 Governance bodies at the Australian Government and interdepartmental levels are presented in Table 2.1. DCCEEW provides the secretariat function for the Deputy Secretary Powering Australia interdepartmental committee (see Chapter 3, paragraph 3.4). The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) provides the secretariat function for all other governance bodies in Table 2.1. Each governance body has an established terms of reference and meets regularly. The structure is designed to allow specific program-level issues to flow upwards from DCCEEW senior executives to ministers, and to allow ministers oversight of broader strategic concerns.

Table 2.1: Australian Government and interdepartmental governance bodies

|

Body |

Level |

Chair |

Date in operation |

Remit/responsibility |

Note |

|

Net Zero Economy Ministerial Steering Committee |

Australian Government |

Prime Minister |

October 2022 to May 2023 |

Direct the work of the Net Zero Economy Taskforce. |

Superseded by NZEC. |

|

Net Zero Economy Committee of Cabinet (NZEC) |

Australian Government |

Prime Minister |

June 2023 to present |

Net zero transformation, including cross-cutting economic, climate, regional and industry policy issues. |

Ongoing.a |

|

Secretaries Group on Climate Action (SGOCA) |

Entity Secretary |

Secretary of DCCEEW |

October 2022 to May 2023 |

Overarching climate change remit. |

Superseded by NZSC. |

|

Net Zero Secretaries Committee (NZSC) |

Entity Secretary |

Co-chaired: Secretary of DCCEEW, Secretary of PM&C |

July 2023 to present |

Net zero transformation, supporting NZEC. |

Ongoing.a |

|

Net Zero Senior Officials’ Committee (NZSOC) |

Entity Deputy Secretary |

Co-chaired: Deputy Secretary of DCCEEW, Deputy Secretary of PM&C |

July 2023 to present |

Net zero transformation, supporting NZEC. |

Ongoing.a |

|

Deputy Secretary Powering Australia Interdepartmental Committee |

Entity Deputy Secretary / Senior Executive Service Band 3 |

Deputy Secretary of DCCEEW |

July 2022 to present |

Specific remit over the Powering Australia program of work. |

Meeting cadence to change following establishment of NZSOC. |

Note a: These bodies were ongoing as of the end of audit fieldwork in October 2023.

Source: ANAO summary of DCCEEW documentation.

Departmental structure and oversight

2.34 DCCEEW was established on 1 July 2022. DCCEEW made changes to its organisational structure in May 2023 and July 2023. DCCEEW’s Climate and Energy functions are structured in separate Groups, each led by a Deputy Secretary.

- Climate Group is responsible for climate change mitigation and adaptation policy and programs, and Australia’s engagement in international climate and energy actions, including the Government’s net zero emissions by 2050 agenda.

- Energy Group is responsible for energy policy and programs. This includes providing policy support to transition Australia’s economy to net zero emissions by 2050 while maintaining energy security, reliability, and affordability.

2.35 The two Groups contained six divisions, each led by a First Assistant Secretary (FAS). In July 2023, a division was added to Energy Group, and in August 2023, a division was added to Climate Group. As of September 2023, the two Groups each have four divisions and comprise 994 staff in total.59

2.36 Weekly senior executive meetings are held with representatives from DCCEEW’s Climate and Energy groups. These meetings involve the Deputy Secretary of the Climate Group, the Deputy Secretary of the Energy Group, and all FAS from both Groups to discuss progress of Powering Australia initiatives.

2.37 Fifty-nine of these weekly senior executive meetings were held from between June 2022 to August 2023. There are records for 41 of 59 (69 per cent) meetings, including 23 of 24 meetings from March 2023 to August 2023. DCCEEW advised the ANAO that records are missing in part due to changes to Information and Communications Technology (ICT) systems that occurred in March 2023. Decisions made and actions arising were not recorded for every instance of these weekly senior executive meetings.

2.38 These weekly senior executive meetings inform subsequent weekly meetings with the Minister for Climate Change and Energy and the Assistant Minister for Climate Change and Energy to ‘make decisions and ensure the government’s climate change and energy agenda is delivered’. DCCEEW do not keep minutes or a record of attendance of these meetings with the Ministers.

2.39 The Archives Act 1983 and policies issued under the Act set obligations for the management of information assets for Australian Government entities, including that entities create and manage information in a manner that supports accountability and transparency, and enables informed decision-making. The Building trust in the public record: managing information and data for government and community policy issued in 2021 notes that ‘good information governance ensures that all obligations are known and met’.60

2.40 The ANAO identified instances of meeting records not being held or not being held consistently in single locations. For example, one board’s meeting papers and records are held in three separate locations across two networks with different security classifications. See Appendix 4.

Recommendation no.2

2.41 The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water develop and implement an information assets management policy consistent with the Archives Act 1983 and supporting policies to ensure that records are complete and accurate.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

2.42 The department is committed to improving its management of information assets. Subject to available resourcing, the department will develop and implement an information assets management policy to improve the quality of record keeping practices across the department.

Does DCCEEW assess and consider risk in ongoing planning and implementation arrangements?

DCCEEW established its enterprise risk management frameworks and procedures in March 2023, nine months after the entity was formed. There has been no reassessment of measures in the Powering Australia program of work against the new framework. In May 2023, DCCEEW established a project board to assess and consider implementation risk to projects within the Powering Australia program of work. This board has considered 12 high priority projects in the delivery stage as of October 2023.

Enterprise risk management

2.43 DCCEEW published its Enterprise Risk Management Framework (ERMF) and associated guidance documents in March 2023.61 The ERMF states that DCCEEW has a ‘low tolerance for policies, programs and activities that contribute to climate and environment harm (e.g. increasing greenhouse gas emissions)’.62

2.44 Risk management in the Powering Australia program of work is at the project level. Business areas delivering a Powering Australia measure or measures are responsible for their own risk assessment and management. Prior to March 2023, DCCEEW relied upon the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE) and the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) risk management frameworks and supporting materials.63 DCCEEW does not have a central record of which Powering Australia measures are operating under a DAWE or DISER framework.

2.45 DCCEEW advised the ANAO that DCCEEW is satisfied that DAWE and DISER frameworks remain appropriate to support work initiated prior to March 2023. DCCEEW’s intranet states that ‘Any previous risk assessments on DISER or DAWE risk registers will need to be transitioned over to the new [DCCEEW] risk register by 31 December 2023’.

Specialist Risk

2.46 DCCEEW’s Corporate Plan 2023–24 notes that ‘failure to address climate-related risk poses a serious threat to delivering DCCEEW’s objectives’, and that:

Climate change is recognised as a specialist risk. This means all staff are responsible for considering climate risks in the context of their risk management activities. This includes both the physical impacts of climate change and the impacts of the transition to global net zero emissions.

In addition to delivering the whole-of-government Climate Risk and Opportunity Management Program to embed climate-related risk considerations across the public sector, we will continue to lead by example in the assessment, management and disclosure of our climate risks and opportunities.

2.47 Specialist risks are defined in the ERMF as risks with a defined management approach driven by government policy or legislation. DCCEEW includes workplace health and safety, climate change, fraud, regulation, and security as specialist risk categories.64 The ERMF recognises that specific risk management frameworks and guidance materials may be developed for specialist risks. Specialist risks are managed and supported by specialist areas within DCCEEW.

2.48 There is no specific risk management framework or guidance material for climate change risk as a specialist risk. Updated specialist risk management documentation for climate change risk in DCCEEW is intended to be available when the Climate Risk and Opportunity Management Program work is delivered (see paragraphs 2.66 to 2.72). In the interim, DCCEEW relies on existing frameworks and guidance materials such as the Climate Compass.65

Project- and program-level risk management

Powering Australia Climate and Energy Project Board

2.49 Risk management across the Powering Australia program of work is led by the individual teams responsible for the delivery of each measure. This aligns with DCCEEW’s overall expectation that business areas are responsible for documenting and treating identified risks (see paragraph 2.44).

2.50 In March 2023, DCCEEW commenced a process for managing priority risks in the Powering Australia program of work. The scoping document proposed focusing on ‘high priority risks impacting the overall success’ of the Powering Australia program of work. These risks were:

- high priority known risks — including implementation risks and strategic risks; and

- highly uncertain risks — including shared risks and emerging risks.

2.51 In May 2023, DCCEEW established the Powering Australia Climate and Energy Project Board (the board) to ‘provide oversight of project management across the Climate and Energy portfolios, with a focus of managing implementation risk for high priority projects currently in the delivery stage.’ The scope of the strategic project board ‘includes but is not limited to Powering Australia initiatives’.66

2.52 Membership of the board includes two DCCEEW Deputy Secretaries and three Division Heads from DCCEEW, and an external advisor.67 The board’s terms of reference note that it ‘shall discuss one to three projects per meeting’. The board met six times from May to October 2023.68

2.53 In August 2023, there were 37 projects from the Powering Australia program of work that DCCEEW considered in scope for discussion by the board, with ten projects already considered. The forward work plan for the board discussed in the October 2023 meeting sets out projects that will be considered each month, with four already considered in August and September 2023; six to be considered in October to December 2023; and four more ‘parked’ for future consideration.

2.54 Project owners are provided with guidance materials and templates intended to support discussion at board meetings. Guidance materials and templates are based on DCCEEW’s enterprise-level risk framework.

2.55 In July 2023, a Board Discussion Model was established which set out the format and role of the board in the discussion of initiatives, including risk. The Model notes that the board ‘will complete the discussion by summarising any actions agreed’ for project owners, for escalation to other governance arrangements, or for the secretariat to organise.

2.56 In August 2023, an ‘action register’ was developed to manage items arising from Board meetings. As of October 2023, there are 29 actions being tracked in the action register, comprising:

- eight with ‘open’ or ‘in progress’ status;

- eight with ‘actioned’ status;

- five with ‘overdue’ status; and

- eight with ‘closed’ status.

2.57 The action register includes details of which team is responsible for delivery of the action; any further information required or action to be taken; and recommendations for closure by the secretariat for the board in subsequent meetings.

2.58 The board is intended to review risk across the Powering Australia program of work. There is no central reporting function for all risks identified across the Powering Australia program of work. The board only considers high priority known risks.

Other governance bodies

2.59 The terms of reference for the Powering Australia interdepartmental committee (the Powering Australia IDC) specifies that its role is to ‘identify emerging risks, interdependencies and cross-cutting issues relevant to the Powering Australia agenda’. The terms of reference also state that the Powering Australia IDC ‘may recommend escalation of identified issues and risks through existing reporting lines of the responsible entity/s [sic]’. The Powering Australia IDC does not utilise or consider a risk register as part of its program of work.

2.60 Available meeting records for weekly DCCEEW senior executive meetings (see paragraph 2.37) do not include discussion of risk. The weekly senior executive meeting does not utilise or consider a risk register as part of its program of work. DCCEEW advised the ANAO in September 2023 that consideration of risks to measures is discussed in context of the agenda for meetings with Ministers (see paragraph 2.36). There is no evidence of this discussion or consideration (see paragraph 2.38).

2.61 Governance bodies at the intergovernmental level include the Energy and Climate Ministerial Council (ECMC), Energy and Climate Senior Officials Group (ECSOG) and working groups associated with the ECMC (see Chapter 3, paragraphs 3.38 to 3.47). The ECMC Working Group Handbook notes that ‘effective risk management is an important element of good governance.’ The Handbook identifies that Working Groups, Work Stream Leads, and Project Leads need to identify, assess and control risks relating to their programs of work, and report on risks to ECSOG. There is no evidence that ECMC Working Groups have commenced reporting risks to ECSOG (see paragraph 3.44).

Recommendation no. 3

2.62 The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water manage and coordinate risk assessment and treatment across the Powering Australia program of work to ensure risk is understood and addressed at both program and enterprise levels.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water response: Agreed.

2.63 The department’s Enterprise Risk Management framework recognises the value of a positive risk culture and articulates an approach that integrates risk management into planning and decision making at all levels. The department will leverage our Enterprise Risk Management Framework to strengthen the management and coordination of risk assessment and treatment across the climate change and energy program of work.

Does DCCEEW produce and provide appropriate information to support climate risk-based decision-making?

Whole-of-government initiatives led by DCCEEW to produce information to support climate risk-based decision-making have commenced. The Climate Impact Statements program to assess climate risk in new policy proposals is being piloted, with further decisions about its implementation across all Australian Government entities to be determined. The National Climate Risk Assessment methodology has been delivered, with a first pass assessment due in December 2023. The Climate Risk and Opportunity Management Program has yet to deliver planned items for use by Australian Government entities.

2.64 DCCEEW is responsible for leading the implementation of policy measures intended to address climate mitigation, adaptation and resilience, as well as to establish standards to assist the Australian Government, jurisdictions, and community to make informed decisions about actions to address climate-related risk.

Whole-of-government climate risk management frameworks

2.65 DCCEEW is responsible for developing the capabilities and systems for the Australian Public Service (APS) to identify, manage and disclose the physical and transitional climate risks and opportunities across entities, policies, programs, operations, assets, and services.69 The Department of Finance is responsible for driving emissions reduction in government operations (‘APS net zero’).70 The Department of the Treasury is responsible for elements of climate-related financial disclosure and reporting, and modelling the economic impact of climate change.71

Climate Risk and Opportunity Management Program

2.66 In the October 2022–23 Budget, the Australian Government provided $9.3 million over four years from 2022–23 for the Commonwealth Climate Risk and Opportunity Management Program (CROMP). The CROMP is the whole-of-government initiative intended to support Australian Government entities to identify, manage, and disclose climate risks and opportunities.

2.67 As part of developing the CROMP, DCCEEW noted that gaps in APS climate risk management included ‘absent or immature[:] governance structures and authorisation; processes, systems and frameworks; skills and capacity, tools and guidance; allocated on-going resourcing and responsibilities; and understanding of climate risk management imperatives’.

2.68 The CROMP Program Plan notes that outcomes sought include:

For the APS to move towards best practice climate risk management it will be necessary to fill these gap[s], which will position the APS to fulfil:

- Legal obligations with respect to climate change defined under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and the Public Service Act 1999 (as per risk management standards)

- Moral obligations (including APS Statement, international agreements, intergenerational equity, leadership by example)

- Political and community expectations (e.g., Powering Australia commitments, National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy, increased transparency, accountability and consistency)

- The need for effective decision-making, including addressing sovereign risk

- International standards and best practice approaches (e.g., TCFD72, international community of practice actions).

2.69 Key deliverables for the CROMP include an APS Climate Risk and Opportunity Strategy; a new Climate Risk Management Framework; a climate risk Learning and Development package; access to a support and capability building service; and an interactive climate risk digital tool.

2.70 In December 2022, the timeline for delivery of the CROMP proposed that the Strategy, Framework, and Learning and Development package would be delivered, and the Support Service would be available no later than 30 June 2023.73 The interactive tool and toolkit were to be released at the end of February 2024.

2.71 As of September 2023, no items from the CROMP have been delivered for use by Australian Government entities. DCCEEW advised the ANAO that the Strategy and Framework have been agreed by the Australian Government, and release of these is subject to government decision.

2.72 DCCEEW advised the ANAO that while the CROMP is being developed, Australian Government entities are encouraged to continue using the Climate Compass framework released in 2018. There is no evidence that DCCEEW is actively applying climate risk management processes in its own work, including in the Powering Australia program of work.

Climate Impact Statements program

2.73 In October 2022, the Australian Government agreed that emissions impacts and climate risks should be integrated into the government decision-making process. The Climate Impact Statements (CIS) program is intended to establish a methodology and toolkit to assist Australian Government entities in undertaking emissions impact and climate risk assessment at the program and policy levels.

2.74 The CIS program comprises two elements: climate risk assessment, and emissions impact assessment. DCCEEW is responsible for undertaking both elements. The CIS program is being piloted for the 2023–24 Mid-Year Economic Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) process in a limited number of entities. DCCEEW is also a participant in the pilot.

2.75 The application of the CIS program to all Australian Government entities for future Budget or MYEFO processes, including any necessary adjustments to the program, will be decided after the pilot is completed.

National Climate Risk Assessment

2.76 In the March 2023–24 Budget, the Australian Government provided $28.0 million over two years from 2023–24 to develop a National Climate Risk Assessment (NCRA) and a National Adaptation Plan (NAP; see paragraph 2.9).74 This funding was described as building on the CROMP. The NCRA and the NAP are being developed by two separate teams within DCCEEW.

2.77 The DCCEEW website states that the NCRA will:

- identify and prioritise things that Australians value the most that are of national significance and are at risk of climate change;

- deliver a shared national framework to inform climate adaptation priorities and resilience actions; and

- enable consistent monitoring of climate risk across all jurisdictions by delivering a baseline of current climate risks and considering new and emerging risks.75

2.78 The DCCEEW website states that the NCRA will be delivered in three stages.

- Scoping stage — stakeholder engagement on climate change impact priorities and development of a methodology to deliver a national climate risk assessment, to be finalised in June 2023.

- Stage one — a qualitative first pass assessment, to be finalised and a list of priority risks for Australia to be delivered in November 2023.

- Stage two — an in-depth quantitative and semi-qualitative analysis of the highest priority risks, to be completed in November 2024.76

2.79 In July 2023, DCCEEW announced that the scoping stage of NCRA was complete and that stage one had commenced.77 The methodology for the NCRA has been published on DCCEEW’s website.

3. Coordination and reporting

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) has established effective coordination and reporting arrangements.

Conclusion

DCCEEW has established partly effective coordination and reporting arrangements. Cross-entity coordination arrangements and activities provide information on measures within the Powering Australia program of work, however DCCEEW cannot demonstrate that arrangements are fulfilling their intended role. Arrangements for managing stakeholder coordination and communication for the Powering Australia program of work have not yet been finalised. DCCEEW utilises existing arrangements for reporting national progress on climate change, which occurs on an annual basis. This reporting occurs at a high, aggregate level. There is no consolidated policy- and program-level reporting on progress, evaluation, and decision-making across the Powering Australia program of work.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations for DCCEEW to finalise the Powering Australia communication and stakeholder engagement plan and clarify roles, responsibilities and outcomes for stakeholder coordination and communication as soon as possible to support timely action and inform effective consultation processes; and to use its reporting to demonstrate that its management of climate and energy work clearly contributes to achieving Australia’s climate change commitments including the contribution to emissions reduction.

The ANAO also identified three opportunities for improvement for DCCEEW to improve documentation of its meetings; develop and utilise guidance material to ensure a consistent understanding and definition of risk across business areas and entities; and establish system controls over documents used to track and report progress of measures.

3.1 In addition to the work undertaken by DCCEEW, achievement of Australia’s climate change commitments will impact and be impacted by those outside of DCCEEW. Decision-making should consider entities undertaking their own actions, those with relevant knowledge, and those affected by the pursuit of Australia’s climate change goals and commitments.78 Effective coordination arrangements would support DCCEEW in understanding whether efforts of all stakeholders are contributing to progress against Australia’s climate change goals and commitments.

3.2 Australia’s Nationally Determined Contribution from June 2022 notes that the national targets and federal emissions reductions policies of the Australian Government are ‘complemented by targets and measures implemented at the State and Territory level, which make a leading contribution to the decarbonisation of Australia’s economy’.79

Does DCCEEW have appropriate arrangements for cross-entity coordination to reduce conflicts and duplication of effort?

Cross-entity arrangements for coordination and reporting are focused on information sharing at a measure level for the Powering Australia program of work. DCCEEW does not use its cross-entity coordination arrangements to identify conflicts and duplication of effort across the Powering Australia program of work.

3.3 The Australian Government’s programs and projects addressing climate change issues are being delivered by multiple agencies and entities.80 DCCEEW’s governance system for oversight of the Powering Australia program of work includes cross-portfolio groups at several levels, including ministers and accountable authorities.

Powering Australia interdepartmental committee

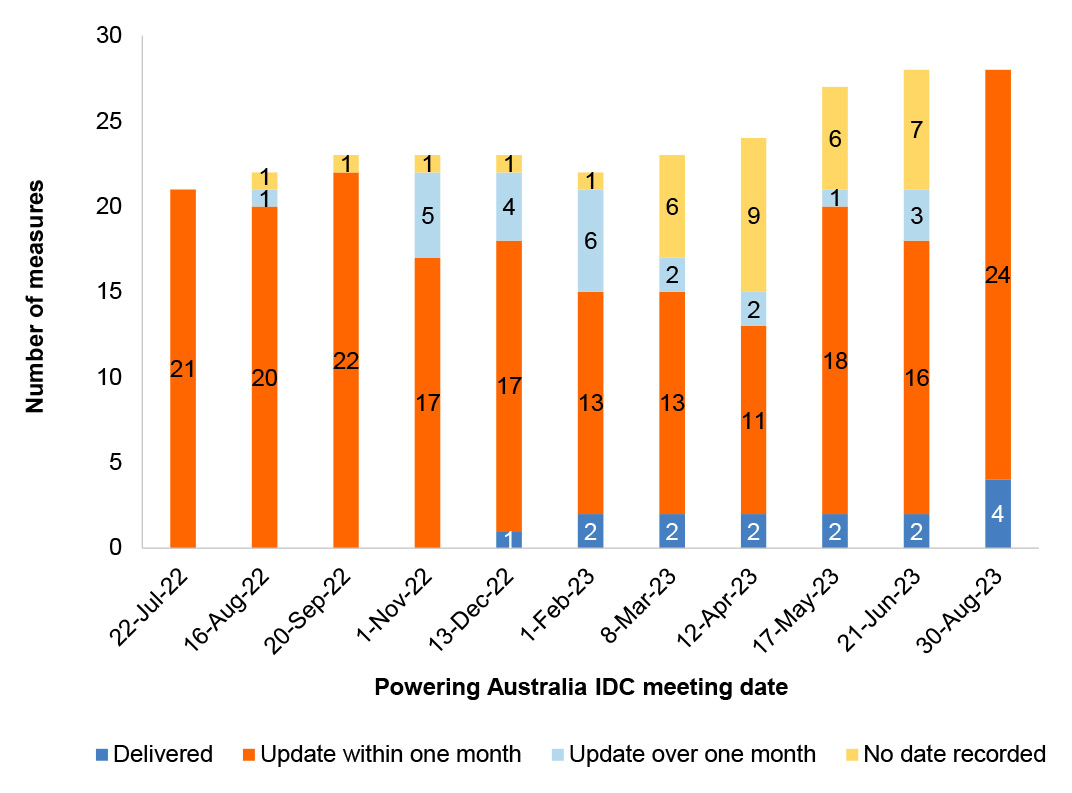

3.4 The Powering Australia interdepartmental committee (Powering Australia IDC) was responsible for coordination of the Australian Government’s Powering Australia program of work from July 2022 to June 2023. Australian Government entities were represented on this committee at the deputy secretary level.81 The committee first endorsed terms of reference in April 2023.

3.5 In July 2023, the Net Zero Secretaries Committee and Net Zero Senior Officials Committee were established to support the Australian Government’s Net Zero Economy Committee in cross-portfolio oversight of the net zero transformation (see Table 2.1). From July 2023 onwards, this includes interdepartmental coordination on the Powering Australia program of work.

Meeting purpose

3.6 Preparation for Powering Australia IDC meetings is the primary opportunity for DCCEEW to collate updates on the activities of other entities as they relate to the Powering Australia program of work. In August 2023, the Powering Australia IDC amended its terms of reference and reduced its own meeting cadence to quarterly in response to the new structure referred to in paragraph 3.5. Twelve Powering Australia IDC meetings were held between 1 July 2022 and 1 September 2023.

3.7 The terms of reference endorsed in April 2023 identified five roles for the Powering Australia IDC.

1. Support cross-portfolio co-ordination and strategic alignment on Powering Australia plan measures, and the commitment to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

2. Review progress updates on the implementation of individual Powering Australia measures, and on emissions projections, to evaluate the progress of Powering Australia, and on achievement of net zero emissions by 2050.

3. Identify emerging risks, interdependencies and cross-cutting issues relevant to the Powering Australia agenda.

4. Discuss and agree mitigation and contingency options for cross-cutting and emerging risks for Powering Australia initiatives.

5. Identify any issues that need to be escalated to the Secretaries Group on Climate Action.

3.8 The updated terms of reference introduced in August 2023 includes four roles, largely covering the same responsibilities. The primary differences between the two sets of roles are that:

- issues are to be escalated through the Net Zero Senior Officials Committee, as the Secretaries Group on Climate Action has been dissolved; and

- roles one and two are altered so that the Powering Australia IDC does not have responsibility over coordination or review of progress towards the achievement of net zero emissions by 2050.

3.9 The ANAO reviewed the available records for 11 Powering Australia IDC meetings prior to August 2023 to identify records of the committee fulfilling each role specified in the April 2023 terms of reference. Assessment of whether the Powering Australia IDC fulfilled its roles was limited by the quality of the records held by DCCEEW. Minutes were not available for all Powering Australia IDC meetings, and where they were available, they did not record conclusions or arising actions for all discussions.

3.10 For Powering Australia IDC meetings where records of discussion were available, the ANAO identified discussion of new measures, measures with changed risk ratings, and measures involved in Budget processes. Agenda items that included further detail on specific measures apart from whether the measure was new, had changed risk rating, or was involved in the Budget process were discussed in 10 of 11 meetings for which records are available.

3.11 All action items recorded at Powering Australia IDC meetings related to the meeting structure or provision of information. No action items were recorded relating to risk mitigation, contingency options, or escalation of issues to the Secretaries Group on Climate Action before the group was superseded by the Net Zero Senior Officials Committee in July 2023.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

3.12 There is an opportunity for DCCEEW to improve documentation of its meetings, especially to support DCCEEW’s ability to demonstrate that governance arrangements are fulfilling the expected purpose. |

3.13 When preparing for Powering Australia IDC meetings, DCCEEW requests updates on measures from other Australian Government entities but does not provide these entities with details of progress on measures for which DCCEEW is responsible until meeting papers have been finalised and distributed. There is no record that duplicated effort or conflicting goals were considered in Powering Australia IDC meetings, outside of potentially duplicative stakeholder engagement (see paragraph 3.23). Discussion of measures at Powering Australia IDC meetings is directed to those identified to be at delivery risk.82

Attendance

3.14 Powering Australia IDC membership consists of Deputy Secretaries or Senior Executive Service (SES) Band 3s from 16 entities. These entities are the Attorney-General’s Department; Austrade; the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry; DCCEEW; the Department of Defence; the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade; the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations; the Department of Finance; the Department of Health and Aged Care; the Department of Home Affairs; the Department of Industry, Science and Resources; Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts; the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; the Department of the Treasury; the National Indigenous Australians Agency; and the Office of National Intelligence.83

3.15 Attendance records were available for eight of nine Powering Australia IDC meetings since 1 November 2022. Records of attendance were not available for meetings prior to November 2022. For the Powering Australia IDC meetings with attendance records, representatives from each entity attended at least one meeting and representatives from 12 entities attended seven or more meetings.84

3.16 Both the April 2023 and August 2023 versions of the terms of reference permit attendance at the Powering Australia IDC meetings to be delegated. Although the Powering Australia IDC is nominally a committee for Deputy Secretaries or equivalent SES Band 3 officials, entities were represented 24 per cent of the time by an SES Band 3; and 51 per cent of the time by an SES Band 2 at the meetings for which records were available. This reliance on delegation was identified as a concern by DCCEEW’s Climate and Energy Deputy Secretaries at an internal DCCEEW meeting in April 2023. There is no evidence that this issue was raised in a Powering Australia IDC meeting. Patterns of delegation have not reduced since April 2023.

3.17 DCCEEW advised the ANAO that ‘members of the [Powering Australia] IDC, and their proxies, are accountable for, and should have visibility of, their entities reporting to the [Powering Australia] IDC.’ Persistent and ongoing delegation of attendance creates risk that representatives do not have the expected level of authority.

Does DCCEEW have an appropriate approach to managing stakeholder coordination and communication?

A stakeholder engagement plan has been in draft since January 2023 and an interdepartmental working group to streamline external stakeholder communication has been established. DCCEEW coordinates with state and territory governments through the Energy and Climate Change Ministerial Council, which is a continuation of a long-standing intergovernmental arrangement.

3.18 DCCEEW’s 2023–24 Corporate Plan states that ‘To deliver on our purposes… it is more important than ever to build and maintain strong and productive partnerships with a diverse range of stakeholders’, including the Australian community, First Nations Peoples, and government agencies at the federal, state, territory, and local levels.

3.19 Implementation of the Powering Australia program of work will impact, and be impacted by, a range of non-government stakeholders, including industry and community groups, as well as the actions of state and territory governments. DCCEEW’s approach to engagement differs between government and non-government stakeholders.

Approach to managing non-government stakeholders

3.20 The Australian Public Service Framework for Engagement and Participation provides best practice guidance for Australian Government entities on engagement, consultation, and collaboration with non-government stakeholders.85 The framework states that ‘it asks public servants to reflect on what expertise they require for the problem at hand, and what engagement will best obtain it, in their circumstances.’

3.21 There is no overarching strategy or framework specifying an approach to stakeholder engagement for the Powering Australia program of work. DCCEEW advised the ANAO that program and policy areas ‘are best placed to determine the approach’ to undertaking stakeholder engagement and that therefore engagement by DCCEEW with non-government stakeholders is undertaken by relevant teams soliciting input and providing information on their program. This audit has not assessed the stakeholder engagement of individual programs in DCCEEW.

3.22 There is a risk that teams delivering measures across the Powering Australia program of work target the same stakeholders, especially when considering the broad implications of climate change and energy policies. An example of this is seen in Case study 1.

|

Case study 1. DCCEEW structures for engagement with First Nations people |

|