Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Fraud Control Arrangements in the Australian Skills Quality Authority

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Fraud and corruption undermine the integrity of and public trust in government, including by reducing funds available for government program delivery and causing financial and reputational damage to defrauded entities.

- The Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) is the Australian Government agency responsible for the regulation of around 90 per cent of vocational education and training (VET) providers operating in Australia.

- The effectiveness of ASQA’s fraud control arrangements in conducting its regulatory functions is important to maintaining the integrity of the VET sector.

Key facts

- ASQA regulates: training providers that deliver VET qualifications and courses to students in Australia or offer Australian qualifications overseas; providers that deliver VET courses to people who are living in Australia on student visas; and certain providers that deliver English Language Intensive Courses for Overseas Students (ELICOS).

What did we find?

- ASQA has established partly effective fraud control arrangements.

- ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 does not consider its regulatory fraud control environment, and there is no process to test regulatory fraud controls systematically and regularly.

- ASQA has established channels to promote fraud awareness.

- ASQA has taken steps to align with the revised Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Policy through the development of an updated Fraud and Corruption Control Policy and Plan

2024–26.

What did we recommend?

- There were three recommendations to ASQA aimed at clarifying the roles of ASQA officials involved in fraud control, updating its Fraud Control Plan and Policy, and testing the effectiveness of fraud controls.

- ASQA agreed to two recommendations and agreed in-part to one recommendation.

3842

VET providers under regulation by ASQA.

223

compliance actions undertaken by ASQA during 2022–23.

7070

applications received by ASQA for registration and accreditation by VET providers during 2022–23.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Fraud against Australian Government entities and corrupt conduct by Australian Government officials are serious matters that can constitute criminal offences. Fraud and corruption undermine the integrity of and public trust in government, including by reducing funds available for government program delivery and causing financial and reputational damage to defrauded entities.1

2. The Australian Government defines fraud as:

Dishonestly obtaining (including attempting to obtain) a gain or benefit, or causing a loss or risk of loss, by deception or other means.2

3. Fraud against the Australian Government can be committed by government officials or contractors (internal fraud) or by parties such as clients of government services, service providers, grant recipients, other members of the public or organised criminal groups (external fraud).3 The Australian Government’s requirements for fraud control apply to both internal and external fraud risks. The 2024 Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework states that:

Fraud and corruption are risks that can undermine the objectives of every Australian Government entity in all areas of their business, including delivery of services and programs, policy-making, regulation, taxation, procurement, grants and internal procedures.4

Australian Skills Quality Authority

4. The Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) is the Australian Government agency responsible for the regulation of around 90 per cent of vocational education and training (VET) providers operating in Australia. ASQA’s purpose is ‘to ensure quality VET, so that students, industry, governments and the community can have confidence in the integrity of national qualifications issued by training providers’.5

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. Fraud against Australian Government entities reduces available funds for public goods and services and causes financial and reputational damage to the Australian Government.6 All Commonwealth entities are required to have fraud control arrangements in place to prevent, detect and respond to fraud. From 1 July 2024, this requirement also extends to corruption.7 This audit is intended to provide assurance to the Parliament regarding the fraud control arrangements in ASQA.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of ASQA’s fraud control arrangements as the national regulator of the vocational education and training sector.

7. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Have appropriate arrangements been established to oversee and manage fraud risks?

- Have appropriate mechanisms been established to prevent fraud and promote a culture of integrity?

- Have appropriate mechanisms been established to detect and respond to fraud?

- Has the Australian Skills Quality Authority appropriately prepared for the commencement of the revised Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control policy in July 2024?

Conclusion

8. ASQA has established partly effective fraud control arrangements. ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 and Fraud Control Policy focus on internal fraud risks and do not consider the entity’s regulatory fraud environment. ASQA has undertaken minimal steps to align with the Commonwealth’s revised Fraud and Corruption Control Framework which came into effect on 1 July 2024.

9. ASQA has not established appropriate arrangements to manage fraud risk. Fraud control arrangements are based on a fraud control policy that was developed in 2013 and does not reflect current Commonwealth legislative and policy requirements. ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 does not consider its regulatory fraud control environment, and there is no process to test regulatory fraud controls systematically and regularly. The Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 contains an overlap of roles and responsibilities of key officials.

10. ASQA has established largely appropriate mechanisms to prevent fraud and promote integrity across its internal and regulatory environments. This includes channels to promote fraud awareness and integrity internally through training, fraud qualifications and professional development, and engagement including social media and sector alerts. Within its regulatory environment, ASQA has established outreach mechanisms to the VET sector that address fraud awareness. ASQA has not appropriately assessed the effectiveness of these mechanisms.

11. ASQA has recently established detection controls, including a tip-off line and information-sharing relationships with external agencies. ASQA has not assessed the effectiveness of these detection controls. ASQA has established an investigatory process for regulatory fraud but does not measure its outcomes or effectiveness.

12. ASQA has taken minimal steps to align with the revised Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Policy through the development of an updated draft Fraud and Corruption Control Policy and Plan for 2024–2026. ASQA has not prepared an implementation plan and there is no evaluation plan for the new or revised controls. ASQA’s new Fraud and Corruption Control Policy and Plan 2024–2026 has minimal updates from the Fraud Control Policy and Plan 2022–2024 and does not include regulatory fraud or corruption controls.

Supporting findings

Oversight and management of fraud risks

13. ASQA’s fraud control framework is based on a fraud control policy that was developed in 2013 and does not reflect current Commonwealth legislative and policy requirements, or the changes the entity has undergone in the 10 years since the policy was developed. ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 does not consider the entity’s regulatory fraud control environment, and associated fraud control activities. ASQA has developed a regulatory model which details ASQA’s regulatory and compliance approach. The regulatory model does not specifically address fraud. ASQA’s fraud control plan includes an overlap of responsibilities between key officials. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.23)

14. ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 identified one external fraud risk. The Plan identified seven internal fraud risks, six of which were reviewed during the period covered by the plan. ASQA undertook risk assessments in 2023 and 2024 within its regulatory environment using its environmental scan tool which identified fraud risk relating to visa fraud. The outcomes of risk assessments were not provided to ASQA’s internal audit function. (See paragraphs 2.24 to 2.39)

15. ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 addresses internal fraud risks and controls and one external fraud risk relating to false or misleading information. The Plan does not address ASQA’s role as the national regulator for the VET sector and its associated regulatory fraud control environment. The Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 contains controls commensurate with the identified internal fraud risks. Limited testing of controls occurred once in 2023, and mechanisms to test the internal fraud controls on a regular basis have not been established. (See paragraphs 2.40 to 2.48)

Fraud prevention and integrity culture

16. Internal preventative controls align with the risks identified in the entity’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024. Regulatory preventative measures include sector alerts and participation in the Fraud Fusion Taskforce. ASQA has not tested the effectiveness of its internal or regulatory fraud prevention controls (including its controls for managing identity fraud), or its documented procedures for preventing, detecting and responding to fraud. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.20)

17. ASQA promotes a fraud awareness culture within the entity through annual mandatory fraud awareness training and utilising internal communication channels, including CEO messages emailed to all staff. As at April 2024, the reported completion rate for ASQA’s mandatory fraud awareness training was 84 per cent. ASQA also undertakes outreach programs through mechanisms such as sector alerts and social media alerts to promote fraud awareness. (See paragraphs 3.21 to 3.27)

18. Officials with fraud control responsibilities at ASQA have opportunities for ongoing professional development through training, such as that provided by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions. ASQA officials engaged in fraud control activities hold relevant qualifications, including the Certificate IV in Government (Investigation) and Diploma in Government (Investigation). (See paragraphs 3.28 to 3.35)

Fraud detection and response

19. ASQA’s detection controls include mechanisms such as a tip-off line and information sharing arrangements with external agencies which provide an appropriate detection framework. There is no documented or consistent process for monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of these detective controls. (See paragraphs 4.2 to 4.25)

20. ASQA has established mechanisms to investigate and respond to fraud but does not measure its performance, including the effectiveness and efficiency of its fraud response. There were no consistent documented processes and procedures for the operation of ASQA’s investigation capability. ASQA has referred matters to external agencies as part of their information sharing mechanisms. In early August 2024 there were two instances where ASQA referred fraud matters to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions. One fraud matter was discussed with the Australian Federal Police in 2023–24. (See paragraphs 4.26 to 4.37)

21. ASQA’s Annual Report 2022–23 includes its Accountable Authority’s certification on fraud control confirming that the CEO was satisfied that ASQA has appropriate prevention, detection, investigation, reporting and data collection procedures and processes in place. This certification in the annual report was not supported by evidence. ASQA has established reporting channels with other Commonwealth entities to report fraud and has provided information to the Australian Institute of Criminology as required, and has not kept records of the information provided. (See paragraphs 4.38 to 4.46)

Preparation for the revised Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework

22. ASQA does not have an implementation plan for the revised Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Policy. ASQA has an updated Fraud and Corruption Control Policy and Plan 2024–2026. As at July 2024, this document is still in draft and does not address ASQA’s regulatory fraud control environment. (See paragraphs 5.2 to 5.8)

23. ASQA has not established a plan to evaluate the implementation of new or revised fraud and corruption controls. (See paragraphs 5.9 to 5.10)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.15

The Australian Skills Quality Authority ensures roles and responsibilities covered in its fraud control arrangements are current and commensurate with existing governance arrangements.

Australian Skills Quality Authority response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.47

The Australian Skills Quality Authority updates its Fraud Control Policy and Plan to cover the full extent of its functions including its regulatory activities, supported by risk assessments that clearly address fraud risk and contain robust mitigation strategies.

Australian Skills Quality Authority response: Agreed in-part.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.24

The Australian Skills Quality Authority documents its processes for monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of its fraud controls across prevention and detection.

Australian Skills Quality Authority response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

24. The proposed audit report was provided to ASQA. ASQA’s summary response is provided below, and its full response is included at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

ASQA places a high value on review and improvement and welcomes the role that ANAO plays in providing independent insights supporting performance improvement. ASQA is already taking action to improve clarity of roles and responsibilities, and document our processes for monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of fraud controls across prevention and detection to ensure that our internal controls are fit for purpose to protect the entity from these risks. Giving consideration to the audit findings, ASQA will now finalise our Fraud and Corruption Policy and Plan 2024-2026 under the revised Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework, which came into effect during this audit in July 2024.

We note that the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework provides a system of governance and accountability across entities for protecting public resources from fraud and corruption. In its role as the National Regulator of VET ASQA is focused on protecting vulnerable students and taking action against non-genuine providers, and to scrutinise those who are in the business of managing or operating RTOs. This has a broader public purpose to prevent harms including those that might arise from external fraud that are not directed at or directly detrimental to the Commonwealth, but to students, employers or industry. This fact has implications for ASQA’s consideration of Recommendation 2 of this report.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

25. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Program design

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Fraud against Australian Government entities and corrupt conduct by Australian Government officials are serious matters that can constitute criminal offences. Fraud and corruption undermine the integrity of and public trust in government, including by reducing funds available for government program delivery and causing financial and reputational damage to defrauded entities.8

1.2 The Australian Government defines fraud as:

Dishonestly obtaining (including attempting to obtain) a gain or benefit, or causing a loss or risk of loss, by deception or other means.9

1.3 Fraud against the Australian Government can be committed by government officials or contractors (internal fraud) or by parties such as clients of government services, service providers, grant recipients, other members of the public or organised criminal groups (external fraud).10 In its annual report on fraud against the Commonwealth11, the Australian Institute of Criminology reported that, for 2022–23:

- 378,033 fraud allegations were received, including 366,196 of external fraud12;

- 5,483 fraud investigations were commenced13, primarily in large (1,001–10,000 employees) and extra-large (greater than 10,000 employees) entities;

- 6,915 fraud investigations were finalised14, with 3,192 fraud allegations substantiated in full or in part15; and

- the quantified reported internal fraud losses were $2.9 million and the quantified reported external fraud losses were estimated at $158.1 million.16

1.4 The Australian Institute of Criminology notes that these reported fraud losses only include those which entities were able to quantify, and that losses and recoveries may be difficult to quantify due to system limitations, conduct of investigations by external agencies or confidential settlements.17

1.5 The Commonwealth Fraud Risk Profile identifies eight fraud risk areas across corporate and program and policy functions (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Fraud risk areas in the Commonwealth

|

Function |

Fraud risk area |

Types of fraud |

|

Corporate |

Assets |

Theft, damage, misuse of facilities, vehicles, equipment, and other physical assets |

|

Corporate information |

Theft, misuse, disclosure of employee information, intellectual property and other official information |

|

|

Human resources |

Fraudulent recruitment and contracting practices and decisions |

|

|

Corporate funds |

Theft, misuse, misdirection of payroll, entitlements, cash, credit cards, travel vouchers, invoicing and procurement |

|

|

Program and policy |

Program payments |

Fraudulent claims, theft, misdirection, misuse of payments and services |

|

Program revenue |

Theft, misuse, misdirection of revenue, royalties and fees |

|

|

Program information |

Theft, misuse, disclosure of citizen and other official program information |

|

|

Program and policy outcome |

Misuse of power or position to unethically influence decisions, policies and outcomes |

|

Source: Attorney-General’s Department, Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre, The New Commonwealth Fraud Risk Profile, AGD, 2022.

The Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework

1.6 The Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework 2017 provided the Australian Government’s fraud control requirements through to 30 June 2024. It had three components (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2: 2017 Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework components

|

Component name |

Purpose |

Binding effect |

|

Fraud Rule — Section 10 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) |

Establishes key fraud control requirements |

|

|

Fraud Policy — Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy |

Establishes procedural requirements for areas of fraud control, including investigations and reporting |

|

|

Fraud Guidance — Resource Management Guide 201 — Preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud |

Establishes better practice guidance for fraud control arrangements |

|

Source: ANAO summary of 2017 Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework components.

1.7 On 1 July 2024, the new Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework 2024 came into effect. From 1 July 2024, non-corporate Commonwealth entities are required to adhere to the revised Fraud and Corruption Policy (see Table 1.3).18 The Fraud and Corruption Policy is considered better practice for corporate Commonwealth entities and Commonwealth companies. The revised framework includes provisions to mitigate corruption risk and complement the function of the National Anti-Corruption Commission.19 It introduces new requirements for fraud governance, oversight arrangements and controls testing.

Table 1.3: Comparison of the key elements of the 2024 Fraud and Corruption Rule to the 2017 Fraud Rule

|

2024 Fraud and Corruption Rule (effective from 1 July 2024) |

2017 Fraud Rule (effective to 30 June 2024) |

|

Entities must conduct fraud and corruption risk assessments regularly and when there is a substantial change in the structure, functions or activities of the entity. |

The Fraud Rule applied these requirements to fraud but not to corruption. |

|

Entities must develop and implement fraud and corruption control plans as soon as practicable after conducting a risk assessment. |

The Fraud Rule applied these requirements to fraud but not to corruption. |

|

Entities must periodically review the effectiveness of their fraud and corruption controls. |

There was no equivalent requirement in the Fraud Rule. The 2023 Commonwealth Risk Management Policy required entities to periodically review the effectiveness of controls. |

|

Entities must have governance structures, processes and officials in place to oversee and manage fraud and corruption risks. Entities must keep records of those structures, processes and officials. |

There was no equivalent requirement in the Fraud Rule. The 2023 Commonwealth Risk Management Policy specified governance requirements. |

|

Entities must have appropriate mechanisms for preventing fraud and corruption by ensuring that:

|

The Fraud Rule applied these requirements to fraud but not to corruption. |

|

Entities must have appropriate mechanisms for:

|

The Fraud Rule applied these requirements to fraud but not to corruption. |

Source: Adapted from Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre, Learn about the Fraud and Corruption Control Framework [Internet], Attorney-General’s Department, 2024, available from https://www.counterfraud.gov.au/learn-about-fraud-and-corruption-control-framework [accessed 25 June 2024].

1.8 The 2017 Fraud Rule and the 2024 Fraud and Corruption Rule apply to both the internal and external fraud risks identified in Table 1.1. The 2024 Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework states that:

Fraud and corruption are risks that can undermine the objectives of every Australian Government entity in all areas of their business, including delivery of services and programs, policy-making, regulation, taxation, procurement, grants and internal procedures.20

Responsibilities of accountable authorities

1.9 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and the PGPA Rule contain specific duties and requirements for the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity pertaining to internal control arrangements, including for fraud control and reporting (see Table 1.4).

Table 1.4: Fraud-related responsibilities of accountable authorities

|

Reference |

Duty or requirement |

|

PGPA Act section 15 |

Duty to govern the Commonwealth entity

|

|

PGPA Act section 16 |

Duty to establish and maintain systems relating to risk and control The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must establish and maintain:

including by implementing measures directed at ensuring officials of the entity comply with the finance law. |

|

PGPA Rule section 10 (the Fraud Rule) |

Preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and deal with fraud relating to the entity, including by:

|

|

PGPA Rule subsection 17AG(2) |

Information on management and accountability The annual report must include the following:

|

Note a: In respect to ‘proper use’, section 8 of the PGPA Act provides that ‘proper, when used in relation to the use or management of public resources, means efficient, effective, economical and ethical’.

Source: PGPA Act and PGPA Rule.

1.10 The Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs) — in place up until 30 September 2024 — note that probity and transparency in grants administration are achieved by ensuring that decisions are impartial, documented, and lawful; there is compliance with public reporting requirements; and there are appropriate safeguards against fraud. The CGRGs state that accountable authorities must ensure that the entity’s fraud procedures and practices comply with the Fraud Rule, including as they apply to grants administration. The CGRGs further note that officials undertaking grants administration should be aware of the procedures to follow if fraud is suspected.21

1.11 The APS Integrity Taskforce’s 2023 report Louder than Words: An APS Integrity Action Plan22 noted the need for entities to gain ‘reassurance that their integrity frameworks are effective and that their fraud and corruption risks are mitigated.’ The report contains a recommendation to ‘upscale institutional integrity (cultural and compliance) within agencies’.23 One of the actions identified by the APS Integrity Taskforce to support implementation of this recommendation is for accountable authorities to complete a self-assessment against the Commonwealth Integrity Maturity Framework and report the results to the Secretaries Board by September 2024.

1.12 ‘Prevent, detect and manage fraud and corruption’ is one of the eight integrity principles identified by the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) in the Commonwealth Integrity Maturity Framework.24 The NACC identified in its Integrity Outlook 2023–24 that:

Minimising the incidence of internal fraud through the identification and management of fraud risks should continue to be an ongoing focus of agencies. This can be achieved through the development, implementation and regular review of fraud prevention and detection strategies.25

Previous audits

1.13 The fraud control arrangements of Australian Government entities have been the subject of previous Auditor-General reports. The most recent was tabled in 2023–24 and examined the Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO’s) management and oversight of fraud control arrangements for the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The audit found that the ATO’s management and oversight of fraud control arrangements for the GST was partly effective.26

1.14 A series of three Auditor-General reports on the fraud control arrangements of Australian Government entities was published in June 2020.27 The reports concluded that:

- fraud control arrangements in the Department of Home Affairs were effective;

- fraud control arrangements in the Department of Social Services and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade were largely effective; and

- each of the audited entities met the mandatory requirements of the 2017 Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework.28

Australian Skills Quality Authority

1.15 The Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) is the Australian Government agency responsible for the regulation of around 90 per cent of vocational education and training (VET) providers operating in Australia. As a non-corporate Commonwealth entity and an independent statutory authority, ASQA regulates:

- providers that deliver VET qualifications and courses;

- providers that deliver VET courses to overseas students;

- accredited VET courses; and

- certain providers that deliver English language intensive courses to overseas students.

1.16 ASQA’s purpose is ‘to ensure quality VET, so that students, industry, governments and the community can have confidence in the integrity of national qualifications issued by training providers’.29

1.17 ASQA’s budget and number of staff in 2023–24 are set out in Table 1.5.

Table 1.5: ASQA’s budget and average staffing levels 2024–25

|

Entity |

Average staffing levela |

Total resourcing |

|

Australian Skills Quality Authority |

225 |

$65,986,000 |

Note a: Average staffing level is a method of counting that adjusts for casual and part-time staff to show the average number of full-time equivalent employees.

Source: Australian Government, Portfolio Budget Statements 2024–25, Employment and Workplace Relations Portfolio, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2024, p. 94.

1.18 ASQA is responsible for the regulation of 3,842 VET providers across the states and territories except for Western Australia and Victoria. As the national regulator for VET, ASQA has the responsibility to manage fraud and corruption internally as well as externally within its regulatory environment. The effectiveness of ASQA’s fraud control arrangements in conducting its regulatory functions is important to maintaining the integrity of the VET sector and Australia’s reputation as a provider of quality education and training. In 2022–23 ASQA received 52,273 enquiries from the sector relating to regulatory obligations. Table 1.6 sets out the number of ASQA’s key regulatory activities undertaken in 2022–23.

Table 1.6: ASQA’s regulatory activity data 2022–23

|

Regulatory activitya |

Number |

|

Applications for registration and course accreditation |

7,070 |

|

Compliance actions |

239 |

Note a: Registration and course accreditation consist of new provider registrations, provider registration renewals, changes of scope registration, course accreditations, course re-accreditations and amended course accreditations. Compliance actions include warning letters, providers entering an agreement to rectify (ATR), written directions, conditions on registration, sanctions which includes cancelling or not renewing registrations.

Source: ASQA Annual Report 2022–23.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.19 Fraud against Australian Government entities reduces available funds for public goods and services and causes financial and reputational damage to the Australian Government.30 All Commonwealth entities are required to have fraud control arrangements in place to prevent, detect and respond to fraud. From 1 July 2024, this requirement also extends to corruption. This audit is intended to provide assurance to the Parliament regarding the fraud control arrangements in ASQA.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.20 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of ASQA’s fraud control arrangements as the national regulator of the vocational education and training sector.

1.21 To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Have appropriate arrangements been established to oversee and manage fraud risks?

- Have appropriate mechanisms been established to prevent fraud and promote a culture of integrity?

- Have appropriate mechanisms been established to detect and respond to fraud?

- Has the Australian Skills Quality Authority appropriately prepared for the commencement of the revised Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control policy in July 2024?

Audit methodology

1.22 The audit methodology included:

- examination of ASQA’s strategies, frameworks, policies, procedures, guidelines and training;

- analysis of ASQA’s information relating to fraud and corruption prevention, detection, investigation and response (including risk assessments, control plans, confidential reporting mechanisms, and investigation, recording and reporting mechanisms);

- review of governance committee papers and minutes;

- review of internal and external reporting on fraud and corruption control activities;

- examination of management-initiated reviews, internal audits and assurance reports; and

- meetings with ASQA staff.

1.23 The ANAO examined ASQA’s fraud control framework from an internal fraud control and regulatory fraud control perspective, including ASQA’s review of controls. The audit did not test the effectiveness of those controls.

1.24 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $397,800.

1.25 The team members for this audit were Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, Lauren Dell and Renina Boyd.

2. Oversight and management of fraud risks

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) has established appropriate arrangements to oversee and manage fraud risks.

Conclusion

ASQA has not established appropriate arrangements to manage fraud risk. Fraud control arrangements are based on a fraud control policy that was developed in 2013 and does not reflect current Commonwealth legislative and policy requirements. ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 does not consider its regulatory fraud control environment, and there is no process to test regulatory fraud controls systematically and regularly. The Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 contains an overlap of roles and responsibilities of key officials.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving the clarity of roles within ASQA’s governance and oversight arrangements for fraud control and update its fraud control plan to address its regulatory fraud control environment.

2.1 Section 16 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) states that the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity has a duty to establish and maintain systems relating to risk and control. The 2017 Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework, which was replaced by the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework 2024 from 1 July 2024, requires accountable authorities to conduct regular fraud risk assessments and, as soon as practicable, develop and implement fraud control plans to deal with the identified risks. The requirement was restated in the 2024 Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework which requires fraud and corruption risk assessments to be undertaken at least every two years.31

Are there appropriate governance and oversight arrangements for fraud control?

ASQA’s fraud control framework is based on a fraud control policy that was developed in 2013 and does not reflect current Commonwealth legislative and policy requirements, or the changes the entity has undergone in the 10 years since the policy was developed. ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 does not consider the entity’s regulatory fraud control environment, and associated fraud control activities. ASQA has developed a regulatory model which details ASQA’s regulatory and compliance approach. The regulatory model does not specifically address fraud. ASQA’s fraud control plan includes an overlap of responsibilities between key officials.

ASQA’s fraud control framework

2.2 As the Commonwealth’s regulator for the Vocational Education and Training (VET) sector, ASQA considers fraud control from both an internal and regulatory perspective. ASQA’s fraud control framework consists of:

- ASQA’s Fraud Control Policy and Fraud Control Plan 2022–24 which addresses its internal environment; and

- ASQA’s regulatory model which addresses its regulatory environment and incorporates fraud control in exercising its functions.

Fraud Control Policy

2.3 ASQA’s current Fraud Control Policy was developed in April 2013 and was scheduled to be reviewed in April 2014. This review did not take place. The key elements of the policy are set out below.

- The policy includes a definition of fraud and its consequences, and references superseded legislation and guidelines including the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 and the Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines 2011.

- The policy applies a definition of corruption based on the outdated Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines 2011 and the former Australian Standard AS 8001–2008: Fraud and Corruption Control.32

- The policy identifies responsibilities for fraud control within ASQA. The policy references former senior management roles within ASQA which no longer exist. The roles are not reflected in the Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 and the policy does not include current roles set out in the Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024.

2.4 Since its Fraud Control Policy was developed in 2013, ASQA has undergone changes to its operations.

- In March 2020, the Australian Government released a rapid review into ASQA’s regulatory practices, presenting 24 agreed recommendations to reform ASQA’s operations in line with best practice, governance, regulation and engagement.

- In October 2023, the Australian Government announced a ‘$37.8 million investment to ensure [ASQA] is adequately equipped and has the technology and data matching capability to identify and respond proactively to unethical and potentially illegal activity’.33

- In March 2024, amendments were made to the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011. The amendments provide ASQA with the regulatory tools to address integrity risks, ensure greater scrutiny of new Registered Training Organisations (RTOs) and promote a quality VET sector.

2.5 ASQA’s Fraud Control Policy 2013 has not been reviewed or updated to reflect these changes.

Fraud Control Plan

2.6 ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 was approved in 2022. The Plan addresses ASQA’s internal fraud arrangements and does not incorporate its regulatory fraud control environment or associated activities. ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 is discussed further below at paragraph 2.42.

2.7 Activities relating to regulatory fraud control are undertaken as part of ASQA’s regulatory operations. ASQA’s approach to addressing regulatory non-compliance is detailed in its regulatory risk framework. The framework identifies that ASQA’s response to regulatory non-compliance is proportionate to the level of risk. ASQA utilises:

a range of regulatory tools to encourage, assist, deter or enforce compliance with the legislation, including the standards is represented in the regulatory pyramid. [ASQA] use[s] education, methods to direct compliance, sanctions and court actions. These tools and measures may be used individually or in combination, to respond in a way that is risk-based and proportionate.34

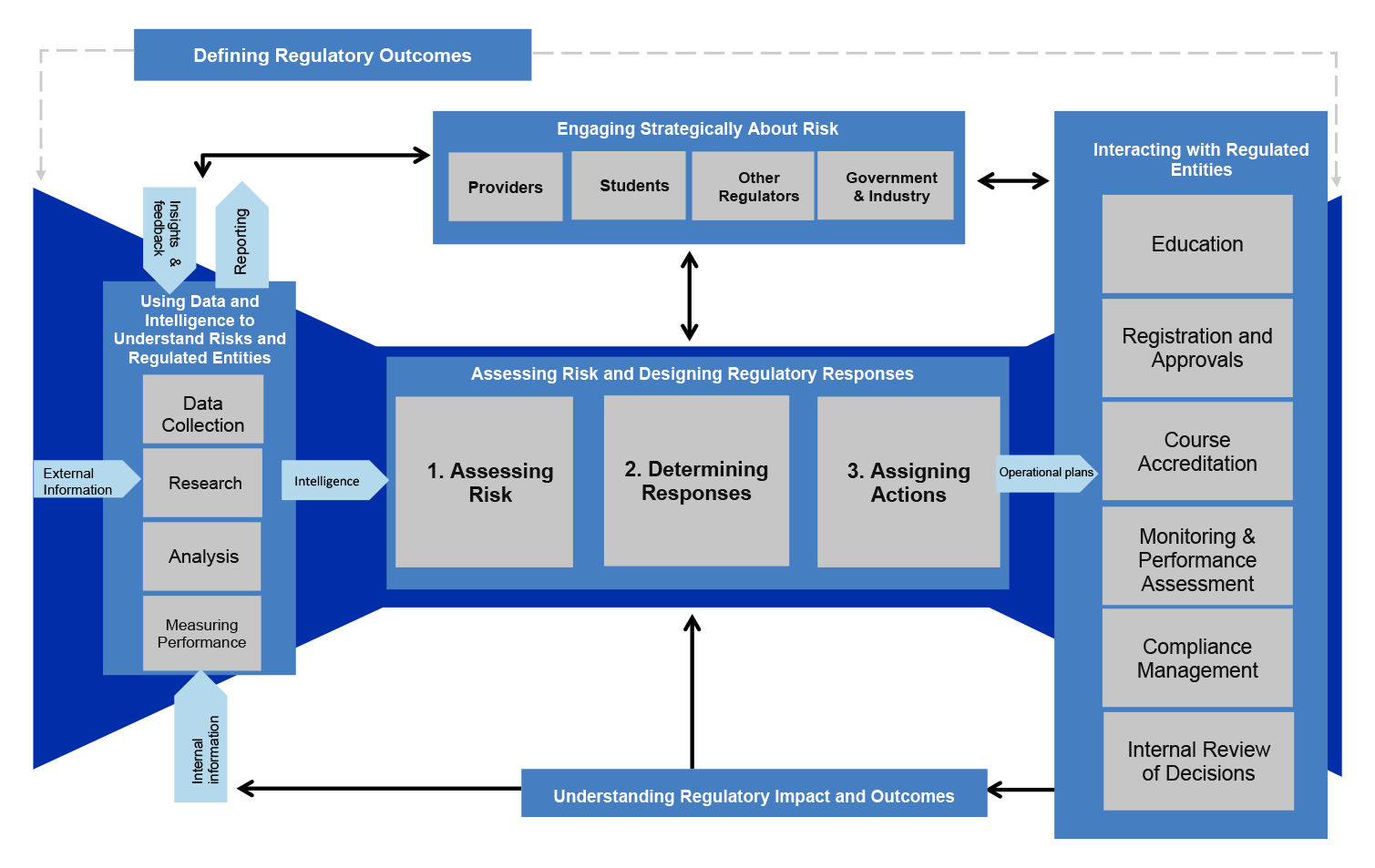

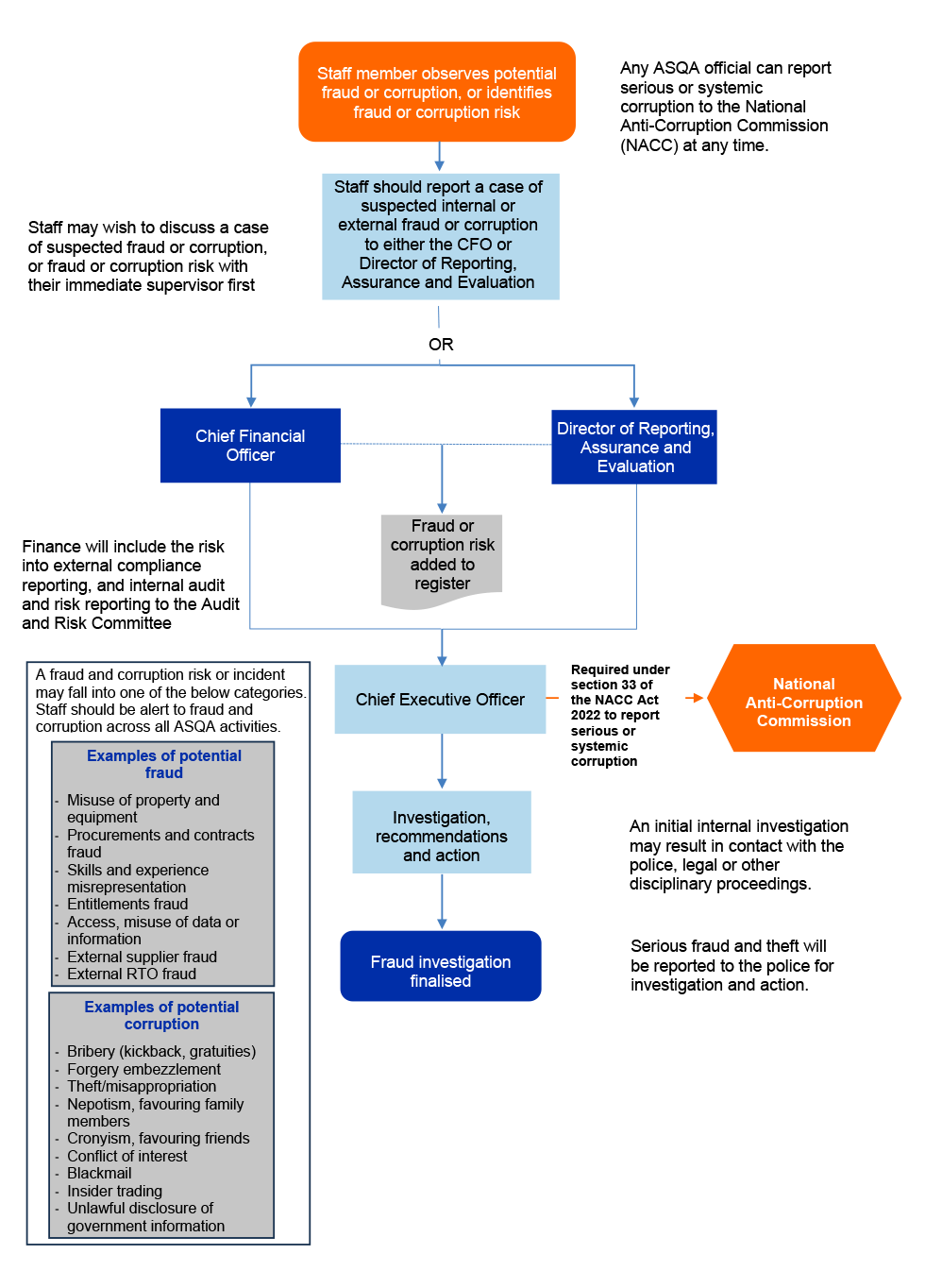

2.8 ASQA’s regulatory model, illustrated in Figure 2.1 below, is contained within its regulatory risk framework. The model includes conducting risk assessments, which then inform the determination of responses and assignment of actions. There is no specific regulatory fraud control process within the model as ASQA considers fraud as part of its day-to-day regulatory activities.

Figure 2.1: ASQA’s regulatory model

Source: ASQA Regulatory Risk Framework, p. 7, available from https://www.asqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-07/regulatory-risk-framework.pdf.

Roles and responsibilities

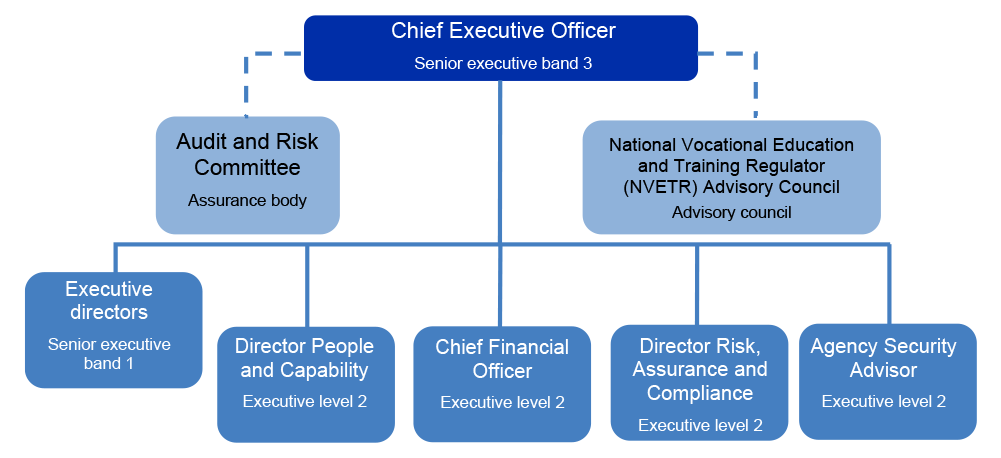

2.9 ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 outlines the key ASQA staff and their respective responsibilities for the management of fraud within the entity.35 ASQA’s roles and responsibilities for fraud control are set out in Figure 2.2 below.

Figure 2.2: ASQA’s roles and responsibilities for oversight of fraud control

Source: ANAO Analysis of ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 and advice from ASQA.

2.10 A description of the roles responsible for fraud control, as set out in ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024, is provided below.

- Chief Executive Officer — ensuring effective management of ASQA’s risk and fraud control and responsible for responding to reports of breaches of the Code of Conduct (including suspected fraudulent activities).

- Executive directors — ensuring operational fraud control activities are implemented such as risk treatments, controls, monitoring and management of fraud risks, determining ASQA’s fraud risk tolerance levels and setting a tone for fraud control within the entity.

- Audit and Risk Committee (ARC) — reviewing and examining successive updates of ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan, and overseeing the risk management strategy and development of the Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. The Committee is also responsible for assuring that processes are in place to prevent, detect and respond to fraud related incidents and monitoring compliance with laws and regulations (including the Fraud Policy and Guidance and the Fraud Rule).

- Director People and Capability — coordinating training across the entity in relation to fraud and managing workforce aspects relating to suspected fraud.

- Chief Financial Officer (CFO) — reports directly to the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) on fraud control and is the central point of contact for fraud control within the entity. The CFO is also responsible for oversight of fraud controls and the maintenance of key documentation.

- Director of Risk Assurance and Compliance — the central point of contact for fraud control within the entity. Manages key fraud risks, including responding to fraud risks at the strategic and operational levels. The director is also responsible for assessing fraud and corruption risk annually.

- Agency Security Advisor — reporting on fraud and corruption within ASQA and investigating alleged fraudulent activities.

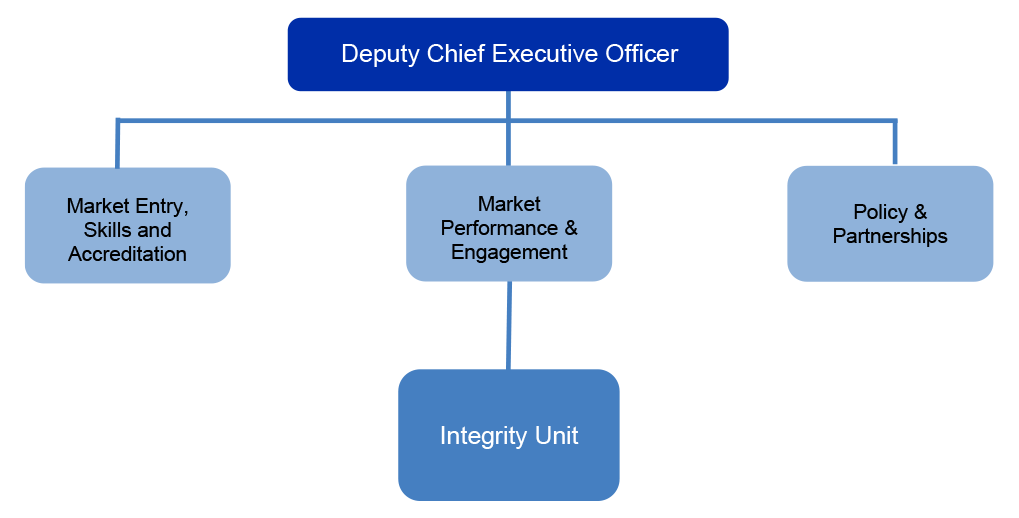

2.11 In addition to these officials, ASQA advised the ANAO on 30 April 2024 that its Resources and Regulatory Committee supports the CEO and delegates to address their fraud control responsibilities. The Committee includes the Deputy CEO, the four regulatory Executive Directors, the CFO and the directors of: Governance, Support and Parliamentary; People and Capability; Risk Assurance and Evaluation; and General Counsel.

2.12 The Committee meets on a monthly basis. The Terms of Reference do not include fraud or fraud control as an objective, and fraud control is not a standing agenda item. In March 2024, the Committee discussed ASQA’s draft Fraud and Corruption Control Policy and Plan 2024–2026.

2.13 ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 contains an overlap of responsibilities. In particular, the CFO and the Director of Risk, Assurance and Compliance hold similar responsibilities in terms of being the ‘central point of contact’. This is also reflected in ASQA’s fraud and corruption reporting flowchart (see Figure 4.2). The Agency Security Advisor role also contains reporting functions that are shared by the CFO and the Director of Risk, Assurance and Compliance.

2.14 In practice, the operation of ASQA’s governance and oversight framework does not reflect the documented responsibilities in its Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024. Fraud control within the regulatory environment was directed by the Deputy CEO, in particular for functions that would align more with the role of the CFO in relation to oversight.

Recommendation no.1

2.15 The Australian Skills Quality Authority updates the roles and responsibilities included in its fraud control arrangements to align with existing governance arrangements.

Australian Skills Quality Authority response: Agreed.

2.16 Giving consideration to the audit findings, ASQA is already taking action to clarify roles and responsibilities in revising our Fraud and Corruption Policy and Plan 2024-2026.

Assurance

Audit and Risk Committee

2.17 ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–24 sets out the role of its ARC in terms of fraud control within the entity.

- Review and examine successive updates of ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan.

- The oversight of the risk management strategy and development of the Fraud and Corruption Control Plan to maintain currency and a focus on areas of medium/high risk.

- Assuring that processes are in place to prevent, detect and respond to fraud related incidents.

- Monitoring compliance with laws and regulations (including the Fraud Policy and Guidance and the ‘Fraud Rule’).

2.18 The ARC minutes of 12 September 2022 identified that in quarter two of 2022–23, the committee discussed ASQA’s strategic and operational risks. The committee reviewed ASQA’s risk register, risk management framework and the strategic risk report. The ARC minutes of 13 May 2024 stated that ASQA provided an update to the ARC on ASQA’s Fraud and Corruption Control Policy and Plan, in preparation for the changes to the Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption from 1 July 2024.

2.19 The ARC meeting minutes of 13 May 2024 also state that the ARC provided feedback on changes to be made to the new Fraud and Corruption Control Policy and Plan 2024–26, such as providing further clarity for employees who report fraud to be assured the matter has been appropriately actioned. The accountable authority did not provide evidence to the ANAO that the Fraud and Corruption Policy and Plan had been approved.

Internal audit

2.20 ASQA conducted an internal audit in May 2023 relating to internal fraud control, specifically addressing its delegations framework. The internal audit report was provided to the ARC on 23 May 2023, and found that ASQA had an appropriate authorisation and delegation process.

2.21 No internal audits have been conducted on regulatory fraud related risks, such as those detected by ASQA’s environmental scans.36 ASQA advised the ANAO on 11 July 2024 that ‘regulatory fraud is an ongoing program of work and fraud may be identified through the course of an audit with particular areas of focus as determined by the regulatory risk priorities’.

Advisory mechanisms

2.22 In April 2022, ASQA established the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Advisory Council as an advisory board on the regulation of the VET sector. The council is an advisory function established under section 174 of the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Act 2011. The key function of the council is ‘to provide advice to the national VET regulator on the regulator’s functions’.37

2.23 The NVETR Advisory Council statement of outcomes states that it considers strategic threat assessments to the integrity of the VET sector but did not specifically address fraud.

Has ASQA appropriately addressed its fraud risks?

ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 identified one external fraud risk. The Plan identified seven internal fraud risks, six of which were reviewed during the period covered by the plan. ASQA undertook risk assessments in 2023 and 2024 within its regulatory environment using its environmental scan tool which identified fraud risk relating to visa fraud. The outcomes of risk assessments were not provided to ASQA’s internal audit function.

2.24 Table 2.1 provides an assessment of ASQA’s approach to applying the Commonwealth’s Fraud Rule, Guidance and Policy in relation to conducting its fraud risk assessments.

Table 2.1: Assessment against the Fraud Framework — Fraud risk assessment

|

Standard |

Assessment |

Paragraphs |

|

Fraud risk assessment conducted regularly and when there is a substantial change in the structures, functions or activities of the entity Fraud Rule, paragraph 10(a) |

◆ |

See paragraphs 2.26 to 2.31 |

|

Risk assessments consider significant entity-specific risk factors Fraud Guidance, paragraph 28; Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines, paragraphs 7.5 to 7.12 |

◆ |

See paragraphs 2.32 to 2.34 |

|

Risk assessment considered relevant risk management and fraud and corruption control standards Fraud Guidance, paragraph 32 |

▲ |

See paragraphs 2.35 to 2.37 |

|

Fraud control arrangements developed in the context of the entity’s overarching risk management framework Fraud Policy, paragraph v |

▲ |

See paragraph 2.38 |

|

Outcomes of risk assessments provided to internal audit for consideration in annual audit work program Fraud Guidance, paragraph 29 |

■ |

See paragraph 2.39 |

Key: ◆ Fully compliant ▲ Partly compliant ■ Not compliant.

Note: The Fraud Rule and Fraud Policy is mandatory for all non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCCEs), and the Fraud Guidance is better practice for NCCEs (see Table 1.2). NCCEs undertake grants administration based on the mandatory requirements and key principles of grants administration in the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (CGRGs). Paragraphs 7.5 to 7.12 of the CGRGs represent better practice for NCCEs.

Source: ANAO analysis of ASQA documentation.

Fraud risk assessments

2.25 The Fraud and Corruption Rule 2017 requires accountable authorities to take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and respond to fraud and corruption relating to the entity, including through conducting assessments of fraud and corruption risks regularly, and when there is a substantial change in the structure, functions or activities.38

2.26 The Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Guidance identifies that:

For many entities, it may be appropriate to integrate enterprise-level fraud and corruption risk assessments into broader enterprise-level risk assessments. Entities with higher exposure to fraud and corruption risks should consider developing a standalone enterprise-level fraud and corruption risk assessment.39

2.27 Risk assessments across ASQA’s internal and regulatory fraud environments are not integrated into enterprise-level risk assessments. ASQA’s approach to fraud risk assessments is based on separate internal and regulatory assessments that are not incorporated into ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024.

2.28 ASQA conducted a review of its internal fraud risks in December 2023 and January 2024. ASQA identified seven internal fraud risks, and one external fraud risk relating to false and misleading information in ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024.

2.29 ASQA’s risk register indicates that six of the eight risks identified in its fraud control plan were reviewed. The six risks were:

- ASQA employees engage in corrupt of fraudulent behaviour;

- inappropriate or unauthorised employee payments are made;

- inappropriate or unauthorised payments or procurements are made;

- misuse/theft of cash, cash equivalents or corporate credit cards;

- payment of employee salaries and entitlements is incorrect; and

- theft, inappropriate disposal, or unauthorised use of ASQA assets for personal gain.

2.30 The two risks not reviewed were:

- an external entity provides false or misleading information to ASQA in order to obtain a favourable regulatory outcome; and

- an external entity attempts to induce a favourable regulatory outcome through bribery, coercion or other corrupt means.

2.31 ASQA’s primary risk assessment tool for regulatory fraud control is its annual environmental scan.40 The scans were conducted in 2023 and 2024.

Entity-specific risk factors

2.32 ASQA’s approach to fraud risk did not include consideration of its regulatory risk assessments as part of the entity’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024. Internal fraud and regulatory fraud risk assessments were conducted as separate fraud control exercises.

2.33 ASQA’s review of its internal fraud risks focussed on risks associated with the misappropriation of money and property. For a smaller entity like ASQA, these risks reflect the entity’s primary internal fraud risks.

2.34 The environmental scans conducted in 2023 and 2024 considered visa fraud as a significant entity risk factor in relation to ASQA’s regulatory environment. ASQA also conducted a risk assessment after the establishment of its tip-off line in October 2023.

Risk, fraud and corruption control standards

2.35 Paragraph 32 of the 2017 Fraud Guidance encourages entities to consider the relevant recognised standards, including the Australian/New Zealand Standard AS/NZ ISO 31000-2009 Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines and Australian Standard AS 8001-2008 Fraud and Corruption Control.

2.36 ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 identifies that it applies the Australian Standard AS 8001–2008: Fraud and Corruption Control. The plan also identifies the Commonwealth’s Fraud Corruption Framework 2017, Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy, the PGPA Act 2013 and associated guidance.

2.37 The Regulatory Risk Management Framework considers relevant standards but does not specify how ASQA meets these standards. Specific fraud and corruption control standards are not mentioned in the environmental scan or tip-off assessments.

Fraud control as part of the risk management framework

2.38 Fraud control arrangements have been developed in the context of the entity’s respective regulatory risk frameworks. The Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 aligns with the entity’s enterprise risk framework. Regulatory fraud risk is addressed through ASQA’s regulatory operating model, which forms part of ASQA’s regulatory risk framework.

Informing internal audit of fraud risk

2.39 ASQA did not provide the findings of the environmental scans to its internal auditor.

Has ASQA developed an appropriate fraud control plan and mechanisms to test the effectiveness of controls?

ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 addresses internal fraud risks and controls and one external fraud risk relating to false and misleading information. The plan does not address ASQA’s role as the national regulator for the VET sector and its associated regulatory fraud control environment. The Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 contains controls commensurate with the identified internal fraud risks. Limited testing of controls occurred once in 2023, and mechanisms to test the internal fraud controls on a regular basis have not been established.

2.40 The Fraud Rule requires accountable authorities to develop and implement control plans to deal with fraud and corruption risks. Controls and strategies in fraud control plans should align with assessed fraud risks.

2.41 Table 2.2 provides an assessment of ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–24 against the Fraud Rule and Guidance.

Table 2.2: Compliance assessment — ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024

|

Standard |

Assessment |

Paragraphs |

|

Fraud control plan developed and implemented that deals with identified risks Fraud Rule, paragraph 10(b) |

▲ |

See paragraph 2.42 |

|

Controls and strategies outlined in the plan are commensurate with assessed fraud risks Fraud Guidance, paragraph 39 |

▲ |

See paragraph 2.43 |

|

Mechanisms established to review and test controls effectiveness on a regular basis Fraud Guidance, paragraphs 39 and 41 |

■ |

See paragraphs 2.44 to 2.46 |

Key: ◆ Fully compliant ▲ Partly compliant ■ Not compliant.

Note: The Fraud Rule is mandatory for all NCCEs.

Source: ANAO analysis of ASQA documentation.

ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan

2.42 ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 documents its approach to managing internal fraud within the entity. It does not include ASQA’s regulatory fraud control arrangements. The Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 states that the plan is a key document in ASQA’s fraud control guidance and should be read in conjunction with ASQA’s Fraud Control Policy. The plan includes a summary of ASQA’s key fraud risks with associated controls and treatment strategies. For each fraud risk, ASQA has identified the senior responsible officer.

Controls and strategies to align with assessed fraud risks

2.43 ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–24 includes seven internal fraud risks and associated controls and one external fraud risk relating to false and misleading information but does not address ASQA’s regulatory role in relation to fraud. Fraud risks identified in the Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 align with ASQA’s enterprise risk register. Internal controls and proposed strategies outlined in fraud control plan are commensurate with assessed fraud risks. A summary of the fraud risks and key controls is provided in Appendix 3.

Review and testing of control effectiveness

2.44 ASQA’s internal audit conducted one controls testing exercise in May 2023, focused on its delegations and authorisations. The testing found that ASQA has an appropriate authorisation and delegation process. There is no strategy or framework for the regular testing of the controls identified in the Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024.

2.45 As mentioned in paragraph 2.42, ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 does not include its regulatory fraud control arrangements. In relation to regulatory fraud control, ASQA advised the ANAO on 11 July 2024 that:

Regulatory fraud is an ongoing program of work and fraud may be identified through the course of an audit, with areas of focus as determined by the regulatory risk priorities. The regulatory risk priorities are:

- non genuine providers and bad faith operators

- inadequate or fraudulent recognition of prior learning

- shortened course duration

- academic cheating

- student work placement

- online delivery.

2.46 On 1 July 2024, ASQA advised the ANAO that environmental scans contribute to testing the effectiveness of controls in ASQA’s regulatory environment, but ASQA was unable to provide evidence of how this occurs.

Recommendation no.2

2.47 The Australian Skills Quality Authority updates its Fraud Control Policy and Plan to cover the full extent of its functions including its regulatory activities, supported by risk assessments that clearly address fraud risk and contain robust mitigation strategies.

Australian Skills Quality Authority response: Agreed in-part.

2.48 ASQA will further consider this recommendation given ASQA’s broader public purpose to prevent harms including those that might arise from external fraud that are not directed at or directly detrimental to the Commonwealth, but to students, employers or industry and the implications and impacts on our regulatory operations if this approach were to be fully adopted.

3. Fraud prevention and promoting a culture of integrity

Areas examined

The chapter examines whether the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) has appropriate mechanisms to prevent fraud and promote a culture of integrity.

Conclusion

ASQA has established largely appropriate mechanisms to prevent fraud and promote integrity across its internal and regulatory environments. This includes channels to promote fraud awareness and integrity internally through training, fraud qualifications and professional development, and engagement including social media and sector alerts. Within its regulatory environment, ASQA has established outreach mechanisms to the Vocational Education and Training (VET) sector that address fraud awareness. ASQA has not appropriately assessed the effectiveness of these mechanisms.

3.1 The Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework 2017 requires accountable authorities to establish appropriate mechanisms for preventing fraud, including by ensuring that entity officials are made aware of what constitutes fraud41, and that officials engaged in fraud control activities receive appropriate training or attain necessary qualifications.42 The Fraud Guidance states that ‘Fraud prevention involves putting into place effective accounting and operational controls, and fostering an ethical culture that encourages all officials to play their part in protecting public resources’.43

Have appropriate mechanisms been established to prevent fraud?

Internal preventative controls align with the risks identified in the entity’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024. Regulatory preventative measures include sector alerts and participation in the Fraud Fusion Taskforce. ASQA has not tested the effectiveness of its internal or regulatory fraud prevention controls (including its controls for managing identity fraud), or its documented procedures for preventing, detecting and responding to fraud.

3.2 Table 3.1 presents an assessment of ASQA’s approach to applying the Commonwealth’s 2017 Fraud Rule, Fraud Guidance and Fraud Policy in relation to fraud prevention.

Table 3.1: Assessment against the Fraud Framework — Fraud prevention in ASQA

|

Standard |

Assessment |

Paragraphs |

|

Entity’s preventative controls are appropriate and effective Fraud Rule, paragraph 10(c) |

▲ |

See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.12 |

|

Entity has developed mechanisms to ensure fraud risk is considered in planning and conducting entity activities Fraud Rule, paragraph 10(c)(ii) |

◆ |

See paragraph 3.13 |

|

Entity maintains appropriately documented instructions and procedures to assist officials to prevent, detect and deal with fraud Fraud Policy, paragraph 1 |

▲ |

See paragraphs 3.14 to 3.16 |

|

Entity has considered strategies to mitigate the risk of identity fraud Fraud Guidance, paragraph 42 |

◆ |

See paragraphs 3.18 to 3.20 |

Key: ◆ Fully compliant ▲ Partly compliant ■ Not compliant.

Note: The Fraud Rule and the Fraud Policy is mandatory for all non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCCEs) and the Fraud Guidance is better practice for NCCEs (see Table 1.2).

Source: ANAO analysis of ASQA documentation.

Appropriateness and effectiveness of preventative controls

Internal fraud

3.3 ASQA’s primary internal fraud preventative control is mandatory fraud awareness training for staff. ASQA requires existing staff and new starters to complete mandatory fraud awareness training: APS Essential — Fraud Awareness. The training provides education on what constitutes fraud, how fraud can occur, and responsibilities when dealing with fraud as a public official. New starters are required to complete the training when onboarding to ASQA and existing staff are required to complete the training annually as a refresher.

3.4 From July 2023 to April 2024, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) shared updates with staff through a total of 14 communications via CEO weekly wraps, videos or messages. Several of these communications include case studies aimed at assisting staff in understanding what constitutes fraudulent behaviour and keeping the staff informed about legislative changes. For example, the CEO provided updates to staff on amendments to the National Vocational Education and Training Regulator Bill, explaining how the new powers will address quality and integrity issues in the VET sector. These updates also cover the Nixon review and government responses.44

3.5 ASQA held an all-staff forum on 21 May 2024 to inform staff about the revised Commonwealth Fraud and Corruption Control Framework. The presentation highlighted new obligations for Commonwealth entities, such as adding corruption to all elements, implementing new regular review requirements, and embedding governance structures. The forum also covered the definitions of fraud and corruption, the role of the National Anti-Corruption Commission, and ASQA’s reporting process for fraud and corruption. The session concluded with a ‘Q&A’ segment to address staff questions.

3.6 ASQA has established internal preventative controls aligned to the risks identified in its Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024. ASQA does not classify its controls into preventative, detective or response controls. Table 3.2 below sets out the controls the ANAO identified as preventative and the list of all controls is at Appendix 3.

Table 3.2: ANAO analysis of ASQA’s fraud preventative controls

|

Fraud risks identified in ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 |

Examples of preventative controls |

|

Corrupt practices by ASQA employees processing Registered Training Operators (RTOs) applications or conducting audits |

|

|

Inappropriate or unauthorised payments or procurements are made |

|

|

Inadequately qualified or unsuitable candidates are inappropriately employed or retained |

|

|

Misuse/theft of cash, cash equivalents or corporate credit cards |

|

|

Inappropriate or unauthorised employee payments are made |

|

|

Theft, inappropriate disposal, or unauthorised use of ASQA assets for personal gain |

|

|

An external entity provides false or misleading information to ASQA in order to obtain a favourable regulatory outcome |

|

|

An external entity attempts to induce a favourable regulatory outcome through bribery, coercion or other corrupt means |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024.

Regulatory fraud

3.7 Within ASQA’s regulatory environment, preventative controls include sector alerts and participation in the Fraud Fusion Taskforce led by the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA). ASQA advised the ANAO on 14 June 2024 that it had implemented preventative regulatory controls through the program of work undertaken by its Integrity Unit, which involves raising awareness through ‘sector alerts’ to the education sector and/or directly communicated to Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students (CRICOS) providers.

Sector alerts

3.8 From May 2023 to April 2024 ASQA issued the following sector alerts.

- Unethical practices of third-party education agents and direct communication to CRICOS providers (11 May 2023) — ASQA emphasised ethical practices in delivering Australian VET qualifications to internal students, promoting the importance of compliance with ESOS Act and National Code Obligations. Subsequently, ASQA communicated directly with all CRICOS providers to restate its expectations and the actions taken to address concerns around provider practice, further reminding providers of their obligations under the Education Services for Overseas Students Act 2000 (ESOS Act) and National code.

- Bogus VET qualifications (9 June 2023) — ASQA highlighted the issue of fraudulent qualification documents, emphasising the legal ramifications under the NVETR Act and urging employers to verify qualifications before acceptance.

- Scam Warning (22 August 2023) — ASQA announced that the Australian Federal Police and Department of Home Affairs have raised awareness about a ‘virtual kidnapping’ scam affecting Chinese students.

- Concerning practices in the real estate sector (13 October 2023) — Issued to providers with specific real estate qualifications in its scope of registration. ASQA identified concerns over inadequate training and assessment practices in real estate qualifications, highlighting the need for RTOs to meet legal and licensing requirements.

- English Language Intensive Courses to Overseas Students (ELICOS): Multiple Confirmations of Enrolment (CoEs) and direct communication to ELICOS providers (17 October 2023) — ASQA alerted ELICOS providers about issuing multiple short CoEs for the same course, stressing compliance with the National Code of Practice for Providers of Education and Training to Overseas Students 201845 and English Language Intensive Courses for Overseas Students (ELICOS) Standards 201846 to ensure proper enrolment practices and student protection.

- Guilty verdict reinforces importance of transparency for third-party RTO agreements (2 April 2024) — ASQA responded to a conviction of Qualify Me! Pty Ltd for misleading practices in VET course advertising, emphasising the need for accurate representation in third-party agreements to protect student interests.

Social media alerts

3.9 ASQA issued the following social media posts in 2023:

- 24 May 2023 (Linkedin and X47) — ASQA identified fraudulent First Aid statements and Early Childhood Education and Care qualifications allegedly issued by Au Skills Training after March 2020, these documents are considered invalid, and individuals possessing them are encouraged to contact ASQA.

- 30 May 2023 (Facebook and Linkedin) — The Australian Government made a post to inform the public about counterfeit First Aid statements of attainment and Early Childhood Education and Care qualifications allegedly issued by Au Skills training after March 2020, requesting anyone in possession of such documents to contact ASQA. ASQA advised the ANAO on 11 July 2024 that it collaborated with the Australian Government social media team through the GovSocial network to share this alert, aiming to reach an audience beyond ASQA’s standard platforms.

- 9 June 2023 (LinkedIn and X) — ASQA issued an alert about bogus qualifications from Au Skills Training. The post emphasised the legal consequences of issuing fraudulent qualifications.

- 15 August 2023 (LinkedIn and X) — ASQA shared a scam alert from the Australian Federal Police and the Department of Home Affairs about a ‘virtual kidnapping’ scam targeting Chinese students, detailing how the scam operates and advising on protective measures.

3.10 Since its establishment in October 2023, ASQA has highlighted the VET tip-off line in its monthly edition of ‘ASQA IQ article’ which is published on its website.48 The ASQA IQ article aims to encourage readers to report any practices or behaviours that compromise the integrity of the VET sector. An ‘ASQA Update’, issued in January 2024, elaborated on ASQA’s mechanisms in safeguarding student welfare and VET quality, which included references to the VET tip-off line and Operation Inglenook, further discussed in paragraphs 4.6 to 4.9.

Fraud Fusion Taskforce

3.11 ASQA includes its participation in the Fraud Fusion Taskforce49 as a preventative measure. In April 2024, ASQA commenced participation in the Fraud Fusion Taskforce which is a partnership between the National Disability Insurance Agency and Services Australia, and other government agencies. The taskforce aims to improve how government agencies work together to detect and prevent fraud and serious organised crime.

Controls testing

3.12 ASQA does not categorise controls into preventative and detective controls within its Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024. ASQA has undertaken limited testing for two internal fraud controls contained within its Fraud Control Plan. There has been no testing to establish the effectiveness of regulatory fraud controls.

Fraud risk considered within ASQA’s activities

3.13 In planning and conducting its regulatory activities, ASQA primarily considers fraud risk as part of overall regulatory risk. Risk assessments inform its outreach mechanisms to the sector about regulatory issues including fraud. Outreach mechanisms are delivered through sector alerts, mentioned in paragraph 3.8, which are part of ASQA’s education and awareness initiatives aimed at promoting a culture of integrity.

Documented instructions to prevent, detect and deal with fraud

3.14 ASQA’s Fraud Control Policy 2013 outlines ASQA’s approach to fraud prevention, detection and response. As discussed in paragraphs 2.9 to 2.10 and 2.43, ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 has outlined the roles and responsibilities of officials involved in internal fraud-related activities and includes documentation of identified risks with corresponding treatments and controls. While the controls are not categorised within the plan, it includes preventative measures for key risks, such as segregation of duties. Additionally, the plan features detective measures including a flowchart procedure for reporting suspected fraud.

3.15 As mentioned in paragraph 2.42, ASQA’s approach to regulatory fraud control is not contained within its fraud control plan. ASQA does not have a regulatory fraud control plan, and there is no documented plan to test the effectiveness of controls within its regulatory functions.

3.16 ASQA advised the ANAO on 17 July 2024 that ASQA’s market entry, registration management and internal review instructions ‘are all relevant to the methodology utilised to assist ASQA staff to prevent, detect and deal with fraud’. These documents provide details on identification of fraud. They do not refer to ASQA’s regulatory risk framework or regulatory model.

Mitigating the risk of identity fraud

Internal identity fraud

3.17 ASQA has policies that detail how it manages the risk of internal identity fraud. These policies cover security of personnel, information technology systems and security governance. Fraud mitigation actions include:

- requiring staff to wear an identity card and swipe the card to enter the office;

- pre-employment checks of potential employees;

- requiring staff members to have a security clearance commensurate to their role;

- requiring staff to take part in annual security awareness training; and

- cyber safety information for staff including awareness of phishing and password safety.

Regulatory identity fraud

3.18 ASQA has a published guide for registered training organisations that details the evidence required for ASQA to establish the identity of an applicant (potential VET provider). ASQA’s mechanisms to verify the identity of the RTOs and individuals include:

- validity checks of details on the initial registration application including the Australian Business Number and Australian Company Number, or for sole traders’ proof of identity documents; and

- ‘Fit and Proper Person’ declarations for CEOs and higher managerial agents which act as a legally binding documents similar to a statutory document.

3.19 A primary mechanism ASQA uses to manage identity fraud within its regulatory environment is a Fit and Proper Person declaration. This declaration is a mandatory requirement for some managerial positions including CEOs or directors of RTOs, and ASQA can also request other positions within entities to complete the declaration. These declarations provide ASQA with information to cross check a person’s identity against:

- compliance with the law including criminal history;

- management history;

- financial records; and

- previous conduct and involvements in registered training organisations.

3.20 These checks are also used by the intelligence team within ASQA, which can identify and share concerns regarding market entry applicants, allowing ASQA’s market entry team to confirm the identity and eligibility of applicants to enter into the sector.

Are appropriate mechanisms in place to promote fraud awareness and a culture of integrity?

ASQA promotes a fraud awareness culture within the entity through annual mandatory fraud awareness training and utilising internal communication channels, including CEO messages emailed to all staff. As at April 2024, the reported completion rate for ASQA’s mandatory fraud awareness training was 84 per cent. ASQA also undertakes outreach programs through mechanisms such as sector alerts and social media alerts to promote fraud awareness.

3.21 Table 3.2 presents an assessment against ASQA’s approach to applying the Commonwealth’s 2017 Fraud Rule and Fraud Guidance in relation to fraud awareness and developing a culture of integrity.

Table 3.3: Assessment against the Fraud Framework — Fraud awareness in ASQA

|

Standard |

Assessment |

Paragraphs |

|

Entity has developed appropriate mechanisms to ensure staff are aware of what constitutes fraud, such as a strategy statement or control plan accessible to staff Fraud Rule, paragraph 10(c)(i), Fraud Guidance, paragraphs 36 and 44 |

◆ |

See paragraph 3.22 |

|

Entity has developed suitable fraud and integrity training for staff Fraud Guidance, paragraph 46 |

◆ |

See paragraphs 3.23 to 3.24 |

|

Entity has undertaken monitoring and evaluation of the effectiveness of fraud and integrity awareness initiatives Fraud Guidance, paragraph 47 |

◆ |

See paragraphs 3.25 to 3.26 |

|

Entity has established outreach programs to inform clients, providers and the public about its fraud control arrangements Fraud Guidance, paragraphs 49, 59 and 60 |

◆ |

See paragraph 3.27 |

Key: ◆ Fully compliant ▲ Partly compliant ■ Not compliant.

Note: The Fraud Rule is mandatory for all NCCEs and the Fraud Guidance is better practice for NCCEs (see Table 1.2).

Source: ANAO analysis of ASQA documentation.

Fraud awareness

3.22 The Fraud Rule requires the accountable authority to ensure that officials in the entity are made aware of what constitutes fraud. ASQA’s Fraud Control Plan 2022–2024 includes a definition of fraud that aligns with Section 4.2 of the Department of Finance’s Resource Management Guide 201, on preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud.50

Fraud and integrity training

3.23 ASQA staff are provided with training resources, including e-learning modules and participation opportunities, aimed at improving capability to detect and identify corruption within the agency. All ASQA internal staff are required to complete the APS Essential — Fraud Awareness unit as part of its induction process, and a refresher unit is required to be completed on an annual basis. As at April 2024, ASQA recorded a completion rate of its fraud awareness training of 84 per cent.

3.24 ASQA’s six senior executives attended an integrity masterclass session in April 2024 conducted by Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR). The integrity masterclass sessions included two self-paced modules undertaken prior to the face-to-face sessions, and materials were provided to participants online.

Monitoring and evaluation of fraud awareness initiatives