Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Fraud Control Arrangements

The audit objective was to examine the selected entities’ effectiveness in implementing entity-wide fraud control arrangements, including compliance with the requirements of the 2011 Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (2011 Guidelines), and the overall administration of the fraud control framework by the Attorney-General’s Department.

Summary

Introduction

1. Fraud against the Commonwealth is defined as ‘dishonestly obtaining a benefit, or causing a loss, by deception or other means.’1 Fraud against the Commonwealth can be broadly categorised as being either external (fraud committed by clients or customers, service providers and members of the public) or internal (fraud committed by employees and contractors). In some cases, fraud against the Commonwealth may involve collusion between external and internal parties, which may not only result in loss for the Commonwealth, but may also involve corrupt conduct such as bribery and secret commissions.

2. The consequences of fraud against the Commonwealth include financial and material loss which can impact on the Australian Government’s ability to deliver services and achieve its policy objectives. More broadly, fraud can result in reputational damage to government and responsible entities, and potential loss of confidence in Australian Government administration.

3. Fraud threats are ongoing and can affect any Australian Government entity. In 2010–11, external and internal fraud losses against the Commonwealth were estimated at $119 million.2 Approximately $116 million of these estimated losses related to external fraud, while some $3 million related to internal fraud.

The Australian Government’s fraud control framework

4. Australian Government entities have long been required to establish arrangements to manage the risks of fraud. The Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act), which operated during the course of fieldwork for this audit3, placed a number of ‘special responsibilities’ on the Chief Executives of FMA Act agencies. For example, section 44 of the FMA Act required Chief Executives to promote the proper use of Commonwealth resources, while section 45 required the implementation of a fraud control plan. In addition, section 64 and FMA Regulation 16A made provision for the responsible minister4 to issue Fraud Control Guidelines.5,6

The Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines

5. At the time of the audit fieldwork, the Australian Government’s framework for fraud control was set out in the 2011 Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (the Guidelines). The Guidelines established the fraud control policy framework within which entities were expected to determine their own specific practices, plans and procedures to manage the prevention and detection of fraudulent activities.

6. The Guidelines contained a mix of mandatory fraud control requirements and other recommended practices as a basis for sound fraud control. Specifically, the Guidelines contained requirements (and other practices) dealing with:

- obligations of chief executives7;

- assessment of the risks of fraud;

- development of fraud control policies, plans and procedures;

- implementation of a program of general fraud awareness training for employees and contractors, and more specialised training for those people engaged in fraud control activities;

- approaches to detecting and responding to fraud events, including the conduct of investigations; and

- gathering, monitoring and reporting information about fraud.

7. A key feature of the 2011 Guidelines was the promotion of an approach focused on embedding fraud control and prevention as part of an entity’s culture and governance arrangements8; a senior leadership responsibility. The ANAO’s 2011 Better Practice Guide on Fraud Control in Australian Government Entities (the Fraud Control BPG) described this as a ‘contemporary’ management approach to fraud control9, in contrast to the more traditional approach focusing primarily on compliance with requirements, detection and investigation.10 The Fraud Control BPG observed that sound and effective fraud control requires commitment at all organisational levels within an entity. Just as governance and project management arrangements have evolved to become common practice in government entities, fraud control strategies need to mature and become an accepted part of the day-to-day running of entities.11

8. All FMA Act agencies were subject to the requirements of the 2011 Guidelines. In addition, a number of Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997 (CAC Act) entities, including Comcare12, chose to apply the Guidelines as a matter of good practice.13,14

9. The fraud control policy framework and 2011 Guidelines were administered by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), which provided advice to agencies on the Guidelines and had responsibility for advising and reporting to ministers on whole-of-government fraud control arrangements.

Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013

10. The basis of the fraud control framework altered from 1 July 2014, when the FMA Act and Regulations were replaced by a new Fraud Rule made pursuant to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).15 The 2011 Guidelines were also replaced on 1 July 2014 by a Guide16 issued by the Minister for Justice under the Fraud Rule, and a Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy.17 AGD continues to administer the fraud control framework.

Selected entities in this audit

11. The entities selected for this audit were: the Australian Trade Commission (Austrade); Comcare; and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA). The overall administration of the fraud control framework by the Attorney-General’s Department was also examined as part of the audit.

12. Further contextual information on the selected entities is provided in Table S.1.

Table S.1 Contextual information about the selected entities

|

|

Austrade |

Comcare |

Department of Veterans’ Affairs |

|

Role |

To advance Australia’s trade, investment, tourism and education promotion interests through information, advice and services to business, the education sector and governments in developing international markets. To provide consular and passport services in specific locations overseas. |

To partner with workers, their employers and unions to keep workers healthy and safe, and reduce the incidence and cost of workplace injury and disease. To manage Commonwealth common law liabilities for asbestos compensation. |

To develop and implement programs that provide services and support to the veteran and defence force communities. To provide programs of care, compensation and commemoration for eligible customers. |

|

Entity type during the course of the audit |

FMA Act |

CAC Act |

FMA Act |

|

Key fraud risks |

|

|

|

|

Number of staff (as at June 2013) |

1003 |

712 |

2058 |

|

Number of staff dedicated to Fraud Control Areas (as at June 2013) |

8 |

6 |

16 |

|

Appropriation in millions (for 2013–14) |

$318.9m |

$897.5mA |

$12 429m |

|

Geographic location |

Worldwide locations, major offices in Sydney and Canberra. |

Offices in most states and territories. |

Offices in every state, major offices in Canberra and Queensland. |

Source: ANAO summary from agencies’ Portfolio Budget Statements, Submissions to the AIC and Annual Reports.

Notes: A: Comcare was not directly appropriated due to its status as a CAC Act entity. Appropriations were made to the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, and subsequently paid to Comcare.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

13. The audit objective was to examine the selected entities’ effectiveness in implementing entity-wide fraud control arrangements, including compliance with the requirements of the 2011 Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (2011 Guidelines), and the overall administration of the fraud control framework by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD).

14. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the selected entity implemented the applicable mandatory requirements of the 2011 Guidelines;

- the selected entity implemented, on a risk basis, appropriate:

- strategies to prevent fraud, train staff and raise internal awareness; and

- processes to monitor, evaluate and report on fraud control arrangements; and

- AGD effectively administered the fraud control framework and supported entities, as required by the Guidelines, following release of the 2011 Guidelines.

15. In addition to examining AGD’s overall administration of the fraud control framework, the ANAO examined the department’s implementation of the ANAO’s most recent performance audit on fraud control.18 Further, the ANAO examined the relationship between AGD and the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC)19, relating to the production of two annual reports to government: Fraud Against the Commonwealth (Fraud Report); and Compliance with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (Compliance Report).

16. The audit did not examine the selected entities’ actions following a decision to investigate possible fraudulent activities. Nor did the audit examine the role of the Australian Federal Police (AFP) or the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions in investigating allegations of fraud and conducting prosecutions.20

17. Separately, the ANAO is conducting a performance audit of Austrade’s Export Management Development Grants (EMDG) program, including its specific fraud control arrangements. The current audit is focussed on Austrade’s entity-wide arrangements, and did not examine the administration of the EMDG except to the extent of its alignment with Austrade’s overarching governance framework for fraud control.

18. In conducting this audit, the ANAO: interviewed relevant officers in each of the selected entities, AGD and the AIC; examined relevant documentation, controls and systems; and examined whether entities had regard to better practice as discussed in the ANAO’s 2011 Fraud Control BPG.

Overall conclusion

19. Fraud control is an ongoing responsibility for Australian Government entities, providing a safeguard against: financial and material losses which can impact on the Government’s ability to deliver services and achieve its policy objectives; reputational damage to government and responsible entities; and loss of confidence in Australian Government administration. Government expectations relating to fraud control have been promulgated over many years in successive Fraud Control Guidelines (the Guidelines) administered by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD). Since 2011, the Guidelines have focused on embedding fraud control as part of an entity’s culture and governance arrangements; an approach which has highlighted the importance of risk management, fraud prevention, awareness-raising and shared responsibility by entity staff and management. This contemporary approach to fraud control contrasts with the more traditional approach focusing on compliance with requirements and the detection and investigation of fraud after it has occurred.

20. Overall, the selected entities—Comcare, the Australian Trade Commission (Austrade) and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA)—were generally compliant with the applicable mandatory requirements of the 2011 Fraud Control Guidelines (2011 Guidelines) in effect during the course of the audit, and had implemented a range of strategies and fraud control measures relevant to their specific circumstances. The strategies and measures implemented by the selected entities had regard to the key focus areas identified in the 2011 Guidelines: risk assessment; the preparation of fraud control plans; fraud awareness and training, including for third party service providers; and detection, investigation and response. However, the selected entities’ progress in transitioning to the more contemporary and preventive approach has varied, with Comcare establishing an internal framework generally aligned with the 2011 Guidelines, while DVA and Austrade were at different stages of transition.

21. AGD’s overall administration of the fraud control framework has been generally effective. The department administers a well-developed framework comprising: documented policy and guidance; clear assignment of roles and responsibilities between AGD and entities; identified points of co-ordination; and the provision of support to entities through networking, communication and training arrangements. However there remains scope for improvement in the preparation of annual whole-of-government Fraud and Compliance Reports to government21, which have only been submitted on time to ministers on three occasions in the past 10 years. Entities have continued to face compliance costs in providing annual information updates for inclusion in the reports, while the Australian Government and its entities have not had the benefit of annual reporting on key trends and developments. AGD should establish a formal arrangement with the AIC to facilitate the timely preparation and submission of the reports, to inform ministers of the extent of fraud against the Commonwealth and entities’ compliance with government requirements.

22. The networking, communication and training activities sponsored by AGD and discussed above, were intended to support entities in transitioning to a more contemporary risk-based approach to fraud control. AGD established dedicated Govdex and Govspace websites to assist the whole-of-government Fraud Control Network and individual entities, and hosted workshops and seminars during 2011–13 to provide training for key entity personnel and support the introduction of the 2011 Guidelines.

23. Among the selected agencies, those which most actively engaged with the ‘community of practice’ sponsored by AGD had also moved further along the road towards adopting a more contemporary approach to fraud control. Comcare participated actively in AGD networks and events, including hosting and chairing some events, while DVA had only occasional involvement. At least since 2010, Austrade and DVA did not participate in AGD-sponsored forums and the Fraud Control Network. Austrade advised that it started to access the Govdex website during the course of the audit. Given the change in approach sought by the Australian Government with the release of the 2011 Guidelines, limited entity engagement with the wider community of practice was a lost opportunity to keep abreast of better practice and key developments in fraud control.

24. The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at supporting the timely preparation of whole-of-government fraud control reports to government by AGD and the AIC. This audit has also highlighted scope for some entities to focus more strongly on transitioning to the more contemporary approach to fraud control.22 Entities in transition can derive particular benefit from ongoing engagement with wider Commonwealth networks, promoting shared responsibility amongst staff and management, and continued senior management attention to drive implementation.

Key findings by chapter

Whole-of-government arrangements for fraud control (Chapter 2)

25. AGD’s overall administration of the Australian Government’s fraud control framework has been generally effective. The department administers a well-developed whole-of-government framework for fraud control which includes: documented policy and guidance which has been regularly updated; clear assignment of the respective roles and responsibilities of AGD and entities; and identified points of co-ordination. The framework is supported by whole-of-government advisory arrangements intended to inform government and entities of key developments, and formal mechanisms to support and maintain communication with entities on policy and other developments.

26. Key communication and advisory mechanisms include the Commonwealth Fraud Control Network and Fraud Liaison Forum, as well as online channels such as dedicated fraud control Govdex and Govspace websites. During 2011-13, AGD conducted training workshops for key personnel and seminars to assist entities with establishing and maintaining appropriate fraud control arrangements; an approach intended to support entities in transitioning to the more contemporary, risk-based and preventive approach to fraud control promoted in the 2011 Guidelines.

27. The 2011 Guidelines required AGD, in cooperation with the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), to produce two key reports annually—Fraud Against the Commonwealth and Compliance with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines.23 These whole-of-government reports are intended to inform government and relevant entities24 of: the level of fraud detected within the Commonwealth; entities’ compliance with the 2011 Guidelines; and the effectiveness of fraud control policies and measures. While the reports are meant to be submitted annually, AGD has only done so three times in the past ten years25; and the remaining reports were submitted between two and 26 months late. Further, the Fraud Against the Commonwealth report due in 2010-11 has not yet been submitted—some three years after the due date—and at the time of this audit there was no indication when it (and the reports for 2011-12 and 2012-13) would be made available to government. A consolidated Compliance with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines report for 2010-13 was submitted in March 2014, during the course of this audit. Nonetheless, entities have continued to face compliance costs involved in providing annual information updates for inclusion in the reports, while the Australian Government and its entities have not had the benefit of annual reporting on key trends and developments.

28. AGD and AIC should establish a formal arrangement to facilitate the timely preparation and submission of the Fraud and Compliance Reports to government.

Preventing fraud (Chapter 3)

29. Fraud control within the Commonwealth public sector has evolved in recent years, with a move away from the more traditional approach focused on compliance, detection and investigation towards a more contemporary approach which treats fraud control and prevention as core elements of corporate governance. The shift in orientation was strongly promoted through the 2011 Guidelines and was also reflected in the Fraud Control BPG. A key feature of the contemporary approach is prevention, with well-designed and implemented strategies to prevent fraud considered the most cost-effective approach to managing fraud risks.

30. Comcare approached fraud control as a key governance function. This approach was reflected in its adoption of an internal fraud prevention framework which included a fit-for-purpose and integrated fraud risk assessment process, and the development of a fraud control plan with a strategic focus on Comcare’s key fraud risks. As part of its prevention strategy, Comcare also implemented a compulsory and well-developed fraud awareness training program, which met the requirements of the Guidelines and provided staff and contractors with regular training to ensure skills and knowledge were up-to-date.

31. DVA’s and Austrade’s approach to fraud control was in transition during the course of the audit. DVA had historically focused largely on compliance, with a heavy emphasis on investigating fraud after it had occurred rather than prevention. The department commenced a significant restructure of its fraud control operations and governance in August 2013, rebalancing its approach to include more prevention and deterrence strategies alongside its existing detection strategies, in line with the more contemporary approach. However, DVA’s approach to date in communicating its revised expectations and raising fraud awareness among staff, has not been fully effective. The relevant education online module was out of date and had not been promoted to staff; however, at the time of the audit, DVA had already commenced developing a new training framework to address this.

32. Austrade has made more limited changes to its entity-wide fraud control arrangements since the introduction of the 2011 Guidelines, and aspects of Austrade’s internal management arrangements relating to fraud control have created a risk of fragmentation. In addition to a whole-of-entity fraud unit located in its Corporate Services Group, Austrade has established a dedicated fraud team within its Export Market Development Grants (EMDG) program, where significant fraud risk has been assessed. The establishment of a dedicated fraud team in a high risk program area is a legitimate risk mitigation strategy; however, there was limited communication or coordination between the two units. Austrade advised the ANAO that the fraud control function and the reporting of fraud is centralised to the role of a senior executive. Nonetheless, Austrade continues to report separately, to the Audit Committee and CEO, on the EMDG program and other entity activities, and there would be benefit in considering an approach involving more structured cross-communication between fraud units to strengthen coordination arrangements. In the course of the audit, Austrade advised the ANAO that an internal review of fraud control arrangements will examine consistency with the Guidelines and ANAO Better Practice Guide, and the risk of fragmentation between fraud management arrangements for EMDG and other parts of Austrade.

33. Austrade’s biennial risk assessment process was conducted on a two-yearly basis consistent with the 2011 Guidelines. As part of that process, Austrade required its 12 business units to identify fraud risks and possible treatments; however, only two business units contributed. Austrade has advised that while the initial processes to develop the draft plan were not ideal, senior management intervention led to broader consultation and improvements in the process. It is by creating a shared responsibility for fraud control amongst staff and management at all levels that an entity is better placed to embed fraud control as part of its governance arrangements and culture.

34. Limitations were also identified in Austrade’s approach to fraud awareness training, with only one question on fraud appearing in the context of an on-line security training module. Staff responses to a 2013 internal survey indicated that less than one in four staff could correctly identify all the potentially fraudulent or corrupt behaviours canvassed.

Detecting and responding to fraud (Chapter 4)

35. Fraud prevention strategies can help reduce, but not entirely eliminate, an entity’s fraud risk. Effective fraud detection and response measures are necessary to provide assurance that perpetrators of fraudulent acts are identified, and appropriate action is taken.

36. Broadly speaking, fraud detection methods can be passive or active. The ANAO examined the selected entities’ implementation of the passive detection measures discussed in the Fraud Control BPG and found that all selected entities had introduced fraud reporting mechanisms for staff and the public. Comcare and DVA adopted a centralised and coordinated approach to the processing of fraud allegations, whereas tip-offs received by Austrade were processed by individual business units. Reflecting Austrade’s administrative arrangements discussed above, Austrade’s central fraud control unit did not always have visibility of the review processes adopted by business units or responses to fraud across the entity. This approach further fragmented internal fraud control arrangements; introducing a risk of inconsistent handling and processing of tip-offs, and a situation where fraud risks were not necessarily monitored or communicated within Austrade.

37. Each of the selected entities employed a range of active detection methods; with the specific measures adopted by entities reflecting their differing business operations. The two payment entities, Comcare and DVA, regularly undertook a wide variety of statistical analysis aimed at detecting anomalies in payment patterns to service providers and beneficiaries that might indicate potential non-compliance or fraudulent practice. Austrade also undertook statistical analysis from time-to-time, to inform its fraud prevention activities, and fraud control was a key focus of its internal audit work program.

38. DVA is required, by the Data-matching Program Act 1990, to perform data matching analysis. Comcare has also added data matching to its range of active detection measures, although it is not mandated. The use of data matching by DVA and Comcare has identified potential cases of fraud.

39. Consistent with the 2011 Guidelines, Comcare and DVA maintained fraud incident registers which were used to inform their CEO of the level of fraud within the entity and to prepare external reporting to AGD. Austrade maintained two separate registers, reflecting the administrative arrangements discussed in paragraph 32 above.

40. The ANAO examined the availability and content of guidance and tools available to fraud investigators in the selected entities. Comcare had a detailed investigation manual, standardised assessment templates and a case prioritisation model to assess and prioritise fraud allegations. DVA had an out-of-date investigation manual and the department advised it was in the process of updating the manual. DVA had implemented a case prioritisation model, which will include assessment templates. Austrade did not have an entity-wide investigation manual, but advised the ANAO that it was drafting such a document.

Monitoring and reviewing fraud arrangements (Chapter 5)

41. In the context of an evolving business and operating environment, entities can help manage their risks by employing a flexible rolling program of reviews, audits and evaluations, and by actively looking for opportunities to improve fraud control arrangements.

42. The selected entities reviewed their risk assessments every two years, and their Fraud Control Plans were updated following those exercises. Comcare and DVA also had established processes to review poorly performing controls, and liaised with their relevant business areas to identify scope for improvement in the control framework.

43. Effective internal reporting can inform an entity’s management of fraud control arrangements by identifying trends, weaknesses and opportunities for improvement. The selected entities’ internal reporting to their respective audit committees (and through the audit committee to the CEO) were generally aligned, in terms of process and content, to the 2011 Guidelines and better practice discussed in the ANAO’s Fraud Control BPG. However, Austrade did not adopt a centralised recording system, and its individual fraud units reported separately to its audit committee and executive, albeit through a nominated senior officer. Further, Austrade’s audit committee received limited information on the outcome of investigations, prosecutions and civil actions.

44. External reporting promotes accountability, informs government and stakeholders of developments, and facilitates whole-of-government monitoring and responses to fraud risks. The selected entities generally complied with the external reporting requirements in the 2011 Guidelines, reported internally and externally on fraud risk and fraud control measures, and certified compliance with the Guidelines in their Annual Reports. However none of the selected entities provided an evaluation, in their external reporting, of the effectiveness of fraud initiatives undertaken by the entity, as required by the Guidelines, to inform stakeholders of the effectiveness of their control arrangements.

Summary of entities’ responses

45. The audited entities’ summary responses are provided below. Appendix 1 contains the entities’ full response to the audit report.

Attorney-General’s Department

The Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) welcomes the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) audit of Fraud Control Arrangements. AGD accepts the ANAO’s recommendation to formalise its business arrangements with the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC).

The Government remains committed to protecting Commonwealth resources from fraud. Fraud control and risk management should be integrated into each entity’s culture and practices, and reflect the individual circumstances of each entity.

AGD is pleased to note the ANAO’s acknowledgement of the effectiveness of AGD’s networking, communication and training activities, and its well-developed Commonwealth fraud control framework. In particular, AGD notes the link between engagement with the AGD-run Fraud Control Network and entities keeping abreast of best practice and key fraud control developments.

AGD believes that the findings of the audit will assist Commonwealth entities in strengthening their fraud control arrangements and minimising fraud. The performance audit will make a valuable contribution to the future development of Commonwealth fraud control arrangements.

Australian Trade Commission

The ANAO’s observations provide helpful guidance to enable Austrade to further improve its fraud control and management arrangements, develop greater consistency with the ANAO Better Practice Guide for Fraud Control, and further strengthen fraud reporting within Austrade.

As recognised in the ANAO’s report, the Export Market Development Grant (EMDG) scheme represents Austrade’s highest fraud risk. While the ANAO’s performance audit of the EMDG scheme will cover specific fraud control arrangements within that scheme, given that audit is still being conducted, it is worth noting here that on balance, a considerable proportion of Austrade’s fraud control effort is directed toward that scheme.

I also can advise that since the audit Austrade has:

established a centralised fraud management database to capture data and facilitate reporting of fraud related matters;

implemented a comprehensive fraud investigation procedures manual;

established a fraud whistle-blower hotline, with reporting information now published on the agency website and the intranet; and

reviewed the annual fraud awareness training module which all staff are required to undertake.

Comcare

The findings and recommendations of the report are noted and accepted by Comcare.

Following a recent internal restructure, Comcare’s Claims and Liability Management and Scheme Management and Regulation divisions are working closely together and with Comcare’s Chief Finance Officer, to further refine Comcare’s approach to managing risk, fraud control and investigation. The approach will be in accordance with the provisions of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and the associated best practice guidance.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs

It is pleasing that the report concludes that agencies involved in the audit are generally compliant with the mandatory requirements under the 2011 Fraud Control Guidelines.

DVA agrees with the audit findings and acknowledges the recommendation.

The report acknowledges that DVA is in a transition phase with the implementation of its fraud and non-compliance reform programme.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.33 |

To facilitate the timely preparation of the annual Fraud Against the Commonwealth Report and the annual Compliance Report to Government, the ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department formalises its business arrangements with the Australian Institute of Criminology. Attorney-General’s Department response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter contains background information about fraud control in the Australian Government public sector, as well as details about the audit objective, criteria and approach.

What is fraud?

1.1 Fraud against the Commonwealth is defined as ‘dishonestly obtaining a benefit, or causing a loss, by deception or other means’.26 Fraud against the Commonwealth can be broadly categorised as being either external (fraud committed by clients or customers, service providers and members of the public) or internal (fraud committed by employees and contractors). In some cases, fraud against the Commonwealth may involve collusion between external and internal parties, which may not only result in loss for the Commonwealth, but may also involve corrupt conduct such as bribery and secret commissions.

1.2 The consequences of fraud against the Commonwealth include financial and material loss which can impact on the Australian Government’s ability to deliver services and achieve its policy objectives. More broadly, fraud can result in reputational damage to government and responsible entities, and potential loss of confidence in Australian Government administration.

1.3 Fraud threats are ongoing and can affect any Australian Government entity. In 2010–11, external and internal fraud losses against the Commonwealth were estimated at $119 million. 27 Approximately $116 million of these estimated losses related to external fraud, while some $3 million related to internal fraud.

1.4 Effective fraud control involves a continuum of mutually reinforcing activities, including:

- identifying (and assessing) the risks of fraud occurring;

- developing and implementing measures to prevent, detect and respond to instances of fraud;

- establishing (and maintaining) a sufficient level of awareness and understanding among staff and contractors, and as appropriate, external stakeholders, about the entity’s approach to fraud control;

- providing (or acquiring) specialised fraud training for key staff;

- appropriately responding to fraud events, including taking corrective action; and

- monitoring, reporting and evaluating fraud control strategies.

The Australian Government’s fraud control framework

1.5 Australian Government agencies have long been required to establish arrangements to deal with the risks of fraud. The Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act), which operated during the course of fieldwork for this audit, placed a number of ‘special responsibilities’ on the Chief Executives of FMA Act agencies. For example, section 44 of the FMA Act required Chief Executives to promote the proper use of Commonwealth resources, while section 45 required the implementation of a fraud control plan. In addition, section 64 and FMA Regulation 16A made provision for the responsible minister (the Minister for Justice) to issue Fraud Control Guidelines.

The Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines

1.6 At the time of the audit fieldwork, the Australian Government’s framework for fraud control was set out in the 2011 Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (2011 Guidelines). The 2011 Guidelines established the fraud control policy framework within which entities were expected to determine their own specific practices, plans and procedures to manage the prevention and detection of fraudulent activities.

1.7 The 2011 Guidelines contained a mix of mandatory fraud control requirements and other recommended practices as a basis for sound fraud control. Specifically, the 2011 Guidelines contained requirements (and other practices) dealing with:

- obligations of chief executives;

- assessment of the risks of fraud;

- development of fraud control policies, plans and procedures;

- implementation of a program of general fraud awareness training for employees and contractors, and more specialised training for those people engaged in fraud control activities;

- approaches to detecting and responding to fraud events, including the conduct of investigations; and

- gathering, monitoring and reporting information about fraud.

1.8 A key feature of the 2011 Guidelines was the promotion of an approach focused on embedding fraud control and prevention as part of an entity’s culture and governance arrangements; a senior leadership responsibility. The ANAO’s 2011 Better Practice Guide on Fraud Control in Australian Government Entities (the Fraud Control BPG) described this as a ‘contemporary’ management approach to fraud control, in contrast to the more traditional approach focusing primarily on compliance with requirements, detection and investigation. The Fraud Control BPG observed that sound and effective fraud control requires commitment at all organisational levels within an entity. Just as governance and project management arrangements have evolved to become common practice in government entities, fraud control strategies need to mature and become an accepted part of the day-to-day running of entities.

1.9 All FMA Act entities were subject to the requirements of the 2011 Guidelines. In addition, a number of Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997 (CAC Act) entities, including Comcare, chose to apply the Guidelines as a matter of good practice.

1.10 The fraud control policy framework and 2011 Guidelines were administered by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), which provided advice to agencies on the Guidelines and had responsibility for advising and reporting to ministers on whole-of-government fraud control arrangements.

Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013

1.11 The basis of the fraud control framework altered from 1 July 2014, when the FMA Act and Regulations were replaced by a new Fraud Rule made pursuant to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). The 2011 Guidelines were also replaced on 1 July 2014 by a Guide issued by the Minister for Justice under the Fraud Rule, and a Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy. AGD continues to administer the fraud control framework.

Previous ANAO audits and the Better Practice Guide

1.12 This audit continues the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) examination of Commonwealth entities’ fraud control arrangements. The ANAO has conducted several audits in recent years on fraud control28, with the most recent audit tabled in 2009–10.29 In 2011, the ANAO also released its updated Better Practice Guide on Fraud Control in Australian Government Entities (the Fraud Control BPG).

Audit objective and approach

1.13 The audit objective was to examine the selected entities’ effectiveness in implementing entity-wide fraud control arrangements, including compliance with the requirements of the 2011 Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (2011 Guidelines), and the overall administration of the fraud control framework by the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD).

1.14 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the selected entity implemented the applicable mandatory requirements of the 2011 Guidelines;

- the selected entity implemented, on a risk basis, appropriate:

- strategies to prevent fraud, train staff and raise internal awareness; and

- processes to monitor, evaluate and report on fraud control arrangements; and

- AGD effectively administered the fraud control framework and supported entities, as required by the Guidelines, following release of the 2011 Guidelines.

1.15 In addition to examining AGD’s overall administration of the fraud control framework, the ANAO examined the department’s implementation of the ANAO’s most recent performance audit on fraud control (Table 1.1).30 Further, the ANAO examined the relationship between AGD and the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC)31, relating to the production of two annual reports to government: Fraud Against the Commonwealth (Fraud Report); and Compliance with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (Compliance Report).

Table 1.1 Recommendations from ANAO Audit Report No.42 2009–10

|

Recommendations |

|

|

Recommendation No. 1 |

The ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department, in its review of the Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (the Guidelines), takes the opportunity to:

|

|

Recommendation No. 2 |

The ANAO recommends that agencies reassess their fraud risks and, where appropriate, the effectiveness of existing fraud control strategies, when undergoing a significant change in role, structure or function, or when implementing a substantially new program or service delivery arrangement. |

Source: ANAO Audit Report No.42 2009–10 Fraud Control in Australian Government Agencies.

1.16 The audit did not examine the selected entities’ actions following a decision to investigate possible fraudulent activities. Nor did the audit examine the role of the Australian Federal Police (AFP) or the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions in investigating allegations of fraud and conducting prosecutions.

1.17 Separately, the ANAO is conducting a performance audit of Austrade’s Export Management Development Grants (EMDG) program, including its fraud control arrangements. The current audit is focussed on Austrade’s entity-wide arrangements, and did not examine the administration of the EMDG except to the extent of its alignment with Austrade’s overarching governance framework for fraud control.

1.18 In conducting this audit, the ANAO: interviewed relevant officers in each of the selected entities, AGD and the AIC; examined relevant documentation, controls and systems; and examined whether entities had regard to better practice as discussed in the ANAO’s 2011 Fraud Control BPG.

1.19 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at an approximate cost to the ANAO of $491 296.

The selected entities

1.20 The audit was conducted in four Australian Government entities:

- Austrade;

- Comcare;

- DVA; and

- AGD.

1.21 Table 1.2 summarises the roles and activities of the selected entities.

Table 1.2 Role of selected entities

|

Audited entity |

Role |

|

AGD |

The Attorney-General’s portfolio provides expert advice and services on a range of law and justice, national security and emergency management issues. AGD is responsible for coordinating fraud control policy, including:

|

|

Austrade |

Austrade advances Australia’s trade, investment, tourism and education promotion interests through information, advice and services to business, the education sector and governments in developing international markets. Austrade also provides consular and passport services in specific locations overseas. |

|

Comcare |

Comcare partners with workers, their employers and unions to keep workers healthy and safe, and reduce the incidence and cost of workplace injury and disease. It is also responsible for managing Commonwealth common law liabilities for asbestos compensation. |

|

DVA |

DVA is the entity with primary responsibility for developing and implementing programs that provide services and support to the veteran and defence force communities. DVA provides programs of care, compensation and commemoration for eligible customers. |

Source: ANAO summary from entities’ Portfolio Budget Statements and Annual Reports.

1.22 Table 1.3 provides further information about Austrade, Comcare and DVA, to establish the context in which their fraud control arrangements operate.

Table 1.3 Contextual information about the selected entities

|

|

Austrade |

Comcare |

Department of Veterans’ Affairs |

|

Entity type during course of the audit |

FMA Act |

CAC Act |

FMA Act |

|

Key fraud risks |

|

|

|

|

Number of staff (as at June 2013) |

1003 |

712 |

2058 |

|

Number of staff dedicated to Fraud Control Areas (as at June 2013) |

8 |

6 |

16 |

|

Appropriation in millions (for 2013–14) |

$318.9m |

$897.5mA |

$12 429m |

|

Geographic location |

Worldwide locations, major offices in Sydney and Canberra. |

Offices in most states and territories. |

Offices in every state, major offices in Canberra and Queensland. |

Source: ANAO summary from agencies’ Portfolio Budget Statements, Submissions to the AIC and Annual Reports.

Notes: A: Comcare was not directly appropriated due to its status as a CAC Act entity. Appropriations were made to the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, and subsequently paid to Comcare.

Structure of the report

1.23 The discussion of the audit findings in this report are presented in the four chapters as outlined in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4 Structure of the report

|

Chapter |

Issues examined |

|

2. Whole-of-Government Arrangements for Fraud Control |

This chapter examines whole-of-government arrangements for the administration of fraud control, including reporting by AGD on compliance with the Fraud Control Guidelines. |

|

3. Preventing Fraud |

This chapter examines the selected entities’ fraud prevention strategies, including governance, risk assessment, communication, training and key internal controls. |

|

4. Detecting and Responding to Fraud |

This chapter examines whether the selected entities have effective systems and processes in place designed to detect and respond to instances of fraud. |

|

5. Monitoring and Reviewing Fraud Control Arrangements |

This chapter examines whether the selected entities have effective processes for monitoring and reviewing their fraud control arrangements. |

Source: ANAO.

2. Whole-of-Government Arrangements for Fraud Control

This chapter examines whole-of-government arrangements for the administration of fraud control, including reporting by the Attorney-General’s Department on compliance with the Fraud Control Guidelines.

Introduction

2.1 The Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (the Guidelines) were issued by the then Minister for Justice in 2011. The Guidelines set out the following whole-of-government roles32:

- the Australian Federal Police are responsible for investigating serious or complex crime against the Commonwealth, which can include both internal and external fraud;

- the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions is responsible for conducting the prosecution of offences relating to breaches of Commonwealth law; and

- the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) is responsible for developing high-level policy advice to government in relation to the Commonwealth’s fraud control arrangements, and for the whole-of-government administration of the Guidelines. These responsibilities include producing an Annual Compliance Report and in conjunction with the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), producing the Annual Report to Government: Fraud Against the Commonwealth—both reports are mandated by the Guidelines and are to be provided to the Minister for Home Affairs.33,34

The Attorney-General’s Department

2.2 As discussed, AGD is responsible for administering the Guidelines and whole-of-government fraud control policy, including:

- providing policy advice to government on fraud control issues;

- advising entities on fraud control; and

- reporting to government on fraud control.

Advice to government

2.3 The whole-of-government framework for fraud control is documented in policy and guidance which has been regularly updated. The responsible Minister issued fraud control Guidelines under the FMA Act and Regulations in 2002 and again in 2011, and as discussed below, revised guidance was released in 2014 to coincide with the operation of the new fraud control framework under the PGPA Act and rules.

2.4 The department has also sought to address specific issues relating to the operation of the framework. For example, the ANAO’s 2009–10 performance audit of Fraud Control in Australian Government Agencies recommended that AGD continue to work with the Department of Finance to clarify which Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997 (CAC Act) bodies were subject to the Guidelines.35 AGD agreed to the recommendation and initiated a review in 2011 relating to the application of the Guidelines to CAC Act entities. In the course of this audit, AGD advised the ANAO that it commenced work to develop a Government Policy Order aimed at enabling the mandatory application of the Guidelines to CAC Act entities; an initiative with the potential to close a gap in the Commonwealth’s fraud control framework, as CAC Act entities were not subject to the Guidelines.

2.5 Work on the draft General Policy Order was suspended in 2012 due to the development of a revised Commonwealth resource management framework, later introduced by the PGPA Act, and related work on the fraud control framework in that context. In December 2013, AGD advised the ANAO that:

AGD has been an active participant in the development of a draft framework to address fraud control under the PGPA Act. This has involved consultation across a wide range of agencies including through the governance framework of committees established by [the Department of Finance] to oversee the development of the Commonwealth’s new financial management framework. Finance has also publically consulted on the draft fraud rule which will underpin fraud control under the PGPA framework. The rule sets out the key principles of fraud control from the Guidelines to ensure continued appropriate fraud control measures. The rule is supported by guidance material drawn from the detail of the Guidelines. The rule and guidance material have gone to the Joint Committee on Public Accounts and Audit as part of its enquiry into the PGPA Act.36

Work on the new fraud framework is continuing. AGD is reviewing the content of the Guidelines in developing guidance material to support the new fraud rule. AGD is consulting with PGPA Act and fraud stakeholders in the development of this guidance. Consideration may also be given to elements of the guidance which would benefit from elevation to a policy.

2.6 The basis of the fraud control framework altered from 1 July 2014, when the FMA Act and Regulations were replaced by a new Fraud Rule made pursuant to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).37 The 2011 Guidelines were also replaced on 1 July 2014 by a Guide38 issued by the Minister for Justice under the Fraud Rule, and a Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy.39 AGD continues to administer the fraud control framework.

2.7 In the context of the new resource management framework operating from 1 July 2014, and related changes to government policies such as the Fraud Control Guidelines, a key responsibility for AGD will be to support entities’ transition to the revised fraud control framework.

Advising entities

2.8 To date, providing advice on fraud control to entities and collaborating across Commonwealth and law enforcement agencies has been a means for AGD to share information and resources and inform its whole-of-government policy advising and reporting roles.

2.9 In its 2009–10 audit on Fraud Control in Australian Government Agencies, the ANAO recommended that AGD consider establishing an approach for the provision of fraud control advice and information to entities, particularly to smaller sized entities, that facilitates the provision and exchange of practical fraud control advice.40 AGD agreed to the recommendation and subsequently developed two websites to support and advise entities: Govspace and Govdex. AGD also maintains a specific fraud enquiry email address which facilitates entity requests for advice on fraud control matters.

2.10 Govspace is a publicly available website which aims to: provide advice on how to report fraud against the Commonwealth; promote awareness among public sector employees and the public on fraud issues; and provide links to fraud related publications.

2.11 The Govdex website is password protected, and can only be accessed by Australian Government staff involved in fraud control. The website aims to: provide a platform for entities to share information not suitable for the public domain such as fraud risk assessments and fraud control plans; to identify key fraud control contacts across entities; and allow fraud control staff to access classified advice on fraud control.

2.12 AGD advised the ANAO that that Govdex will be updated to reflect the revised fraud control framework, including the Fraud Rule, Fraud Policy and Fraud Guidance and an explanation of how elements of the framework interact and apply to entities. AGD also advised that it would be using Govdex to release an electronic whole-of-Government e-learning fraud awareness package for all Commonwealth entities.

2.13 The fraud managers at Comcare and DVA advised the ANAO that they had found the Govdex and Govspace websites useful, and had used the websites to: obtain contact details for other entities; review fraud control plans; and review other entities’ fraud control arrangements. While Austrade had not previously utilised the Govdex or Govspace websites, it established access to Govdex on 19 June 2014.

2.14 AGD has also established several useful channels to enable collaboration across government on fraud control issues, including:

- the Commonwealth Fraud Control Network—a cross-entity network of fraud control officers. The Network aims to assist with communication between entities on fraud control matters and communication on fraud matters; and

- the Fraud Liaison Forum—an annual forum open to all fraud control officers, co-hosted by AGD and the Australian Federal Police. The forum aims to provide a vehicle for discussing key fraud control issues, and networking between fraud control officers.

2.15 Effective use of the communication and networking channels will help support entities in their transition to the revised fraud control framework under the PGPA Act.

2.16 AGD has provided further support and training to entities through workshops and seminars on fraud control matters, as well as participating in fraud control groups formed by other entities. These initiatives have included:

- CAC Act entity awareness raising (December 2011)—as part of the development of the Government Policy Order to apply the Guidelines to CAC Act entities (see paragraph 2.4);

- a fraud control plan workshop (March 2012)—targeting smaller entities with limited resources to develop fraud control plans;

- a risk assessment workshop (May 2012)—targeting small to medium size entities with existing but limited fraud control capacity. The aim of the workshop was to identify best practice and facilitate sharing of information and practices within similar entities;

- multiple workshops to review investigator training under the Certificate IV in Government investigations in 2012–13;

- information sessions and workshops on the new Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework;

- assistance to the Australian Federal Police to run Commonwealth Agency Investigator Workshops; and

- a whole-of-Government e-learning fraud awareness training package to assist entities to understand the new fraud framework and meet their obligations under the PGPA Act.

2.17 Of the selected entities, Comcare advised the ANAO that its personnel had attended some of the workshops and sessions provided by AGD and stated that these sessions had been

… useful to understand the approaches that other agencies adopted to develop risk assessments. [The workshop] enabled us to build ongoing relationships with other agencies and share information on common risks and controls.

2.18 DVA and Austrade advised that they had not attended any of the workshops or sessions provided by AGD.

Reporting to government

2.19 AGD’s whole-of-government role includes administering the collection, analysis and reporting of key information to government on the level of fraud within entities; and the effectiveness of fraud control policy and measures. The engagement activities discussed in the previous section provide a basis for AGD to keep abreast of developments within entities and in the broader environment, so as to advise entities and government. In addition, the Guidelines provide for the preparation of annual fraud and compliance reports41 which are the main channel through which the Government is informed of the current status of fraud control arrangements, including entities’ compliance with the Guidelines and the level of fraud detected within entities.

2.20 Preparation of the reports is partly a shared responsibility between AGD and AIC. The Guidelines state that:

The AIC, in consultation with the AGD and AFP, will provide an annual report on fraud against the Commonwealth and fraud control arrangements in Australian Government agencies to the Minister for Home Affairs.42 This report will also be provided to Ministers, Presiding Officers and Chief Executives…

The AGD will also provide an annual compliance report to Government, through the Minister for Home Affairs, on whole-of-Government compliance with the requirements of the Guidelines.43

2.21 Preparation of the annual fraud and compliance reports is discussed in the following section.

Annual fraud and compliance reports

Fraud against the Commonwealth Report

2.22 To support AGD and AIC in producing the Fraud Against the Commonwealth Report, the Guidelines require entities to:

... collect information on fraud and provide it to the AIC by 30 September each year to facilitate the process of annual reporting to Government…This includes incidents of suspected fraud, incidents under investigation, and completed incidents, whether the fraud was proved or not, and whether the incident was dealt with by a criminal, civil or administrative remedy.44

2.23 The Guidelines also require AGD and AIC to work in consultation with each other, and other entities, to develop the survey material sent to the entities to collect data for the Report.45 However, there is no formal agreement between AGD and AIC to support the preparation of the annual report, and there would be benefit in the entities entering into such an arrangement to support the timely preparation of the report—which has been problematic in recent years.

2.24 The ANAO examined the release date of the Fraud Against the Commonwealth Report since its inception, and found that there was not a consistent annual cycle for the publication of the report (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Release dates of previous ‘Fraud Against the Commonwealth Reports’

|

Financial year of report data |

Agency responsible for the reportA |

Report publicly released? |

Date report was sent to the Minister or published |

Time elapsed since previous report |

|

2002–03 |

AGD |

No |

February 2004 |

— |

|

2003–04 |

AGD |

No |

December 2004 |

10 months |

|

2004–05 |

AGD |

No |

July 2006 |

19 months |

|

2005–06 |

AGD |

No |

March 2007 |

9 months |

|

2006–07 |

AIC |

No |

September 2008 |

16 months |

|

2007–08 |

AIC |

No |

November 2009 |

14 months |

|

2008–09 |

AIC |

Yes |

April 2011 |

17 months |

|

2009–10 |

AIC |

Yes |

March 2012 |

11 months |

|

2010–11 2011–12B |

AIC |

Proposed |

Not yet released |

At October 2014, 31 months |

Source: ANAO summary of data from AGD.

Notes:

A: In 2007, responsibility for preparing the annual Fraud Against the Commonwealth Report was transferred from the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) to the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC).

B: AGD advised the ANAO that it would be releasing the findings for these two financial years in one report.

2.25 Further, AIC has not produced the report since the introduction of the 2011 Guidelines, and subsequently the Government has not had the benefit of a consolidated report—including information on the number of suspected fraud incidents, the response to these incidents by reporting entities, and if any legal remedies had been sought in response to these incidents—for three consecutive years. AGD advised the ANAO on 7 December 2013, that the report had not been produced due to ‘new reporting requirements and changes to the survey in 2011 [which] led to delays in the AIC collecting and collating data on the survey.’

2.26 Notwithstanding the continued delays in releasing the report, entities were required to annually submit information to AGD for inclusion in the report. The three entities examined in this audit advised the ANAO that the annual compilation of this information was a significant administrative task, particularly in a resource constrained environment.

2.27 The annual consolidation of current and reliable information on fraud was intended to enable the Government and entities to monitor and respond to emerging risks, threats and other developments in a timely manner. The failure to provide the Minister for Home Affairs and Parliament with the Fraud Against the Commonwealth Report for some three years, is a shortcoming in the overall administration of the fraud control framework. Delays have come at a cost to all entities which are required to provide annual input to the report, and have meant that the government has not had the benefit of annual reporting on key trends and developments.

2.28 In its 2009–10 audit report, the ANAO recommended that AGD consult with the AIC and consider approaches that will allow the AIC to collect, analyse and disseminate fraud trend data on a more consistent basis. In the context of the current audit, AGD advised the ANAO that:

… it had consulted with AIC which has led to improvements in the fraud control survey and the analysis of fraud data.46

Annual Compliance Report

2.29 The Guidelines also require AGD to provide the Government, through the responsible Minister47, with an ‘annual compliance report…on whole-of-government compliance with the requirements of the Guidelines’.48 As with the Fraud Against the Commonwealth Report, the compliance report has not been prepared annually as required by the Guidelines. In the absence of a current publicly available report, on 28 February 2014 AGD provided the ANAO with a draft Annual Compliance Report, which contained a summary of some findings taken from the 2010–11 and 2011–12 AIC survey response (see Appendix 4).

2.30 A significant finding reported in the draft Annual Compliance Report (2010–11 and 2011–12) is that, in 2011–12, most entities which were non-compliant with the risk assessments or fraud control plan requirements were either new entities or entities that were previously CAC Act entities. The draft Annual Compliance Report also identifies that between 2010–11 and 2011–12, the percentage of FMA Act entities responding to the AIC survey had dropped from 94.2 per cent to 87.4 per cent, but does not specify any reason for the decrease in the response rate by entities.

2.31 On 8 July 2014, AGD advised the ANAO that:

… the Compliance Report was delayed and not prepared annually for the years from 2011–13 as [AGD] did not received the necessary data from the AIC in order to produce the report on time. When [AGD] received the relevant data in 2013 for the 2010–11 and 2011–12 financial years, [AGD] combined it to produce a report for those years. [AGD] are yet to receive data for the 2012–13 financial year.

2.32 As discussed, no formal business arrangements exist between AGD and AIC relating to the preparation of the two reports. To strengthen their relationship, AGD should consider negotiating formal arrangements with AIC focussing on the timely preparation of the reports on an annual basis.

Recommendation No.1

2.33 To facilitate the timely preparation of the annual Fraud Against the Commonwealth Report and the annual Compliance Report to Government, the ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department formalises its business arrangements with the Australian Institute of Criminology.

AGD response:

2.34 Agreed. AGD recognises the importance of the trend data in the Annual Fraud Against the Commonwealth Report and the Report on Compliance with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines for informing policy and program approaches to fraud at an entity and whole of government level. AGD is working with the AIC to formalise arrangements for the production of these reports and provision of relevant data from the AIC to AGD.

Conclusion

2.35 AGD’s overall administration of the Australian Government’s fraud control framework has been generally effective. The department administers a well-developed whole-of-government framework for fraud control which includes: documented policy and guidance which has been regularly updated; clear assignment of the respective roles and responsibilities of AGD and entities; and identified points of co-ordination. The framework is supported by whole-of-government advisory arrangements intended to inform government and entities of key developments, and formal mechanisms to support and maintain communication with entities on policy and other developments.

2.36 Key communication and advisory mechanisms include the Commonwealth Fraud Control Network and Fraud Liaison Forum, as well as online channels such as dedicated fraud control Govdex and Govspace websites. During 2011-13, AGD conducted training workshops for key personnel and seminars to assist entities with establishing and maintaining appropriate fraud control arrangements; an approach intended to support entities in transitioning to the more contemporary, risk-based and preventative approach to fraud control promoted in the 2011 Guidelines.

2.37 The 2011 Guidelines required AGD, in cooperation with the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), to produce two key reports annually—Fraud Against the Commonwealth (the Fraud Report) and Compliance with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (the Compliance Report).49 These whole-of-government reports are intended to inform government and relevant entities of: the level of fraud detected within the Commonwealth; entities’ compliance with the Guidelines; and the effectiveness of fraud control policies and measures. While the reports are meant to be submitted annually, AGD has only done so three times in the past ten years; and the remaining reports were submitted between two and 26 months late. Further, the Fraud Report due in 2010-11 has not yet been submitted—some three years after the due date—and at the time of this audit there was no indication when it (and the reports for 2011–12 and 2012–13) would be made available to government. Nonetheless, entities have continued to face compliance costs involved in providing annual information updates for inclusion in the reports, while the Australian Government and its entities have not had the benefit of annual reporting on key trends and developments.

2.38 AGD and AIC should establish a formal arrangement to facilitate the timely preparation and submission of the Fraud and Compliance Reports to government.

3. Preventing Fraud

This chapter examines the selected entities’ fraud prevention strategies, including governance, risk assessment, communication, training and key internal controls.

Introduction

3.1 Well designed and implemented strategies to prevent fraud are the first line of defence and provide the most cost-effective method of fraud control in an organisation.50 A number of elements are necessary for effective fraud prevention, including: senior leadership which promotes an ethical internal culture; an appropriate level of awareness about fraud-related issues among staff and contractors; a risk-based approach to identifying, assessing and treating risks; and well-designed and implemented internal control measures.

3.2 Fraud control within the Commonwealth public sector has evolved in recent years from having a largely compliance focus to now being considered a core element of corporate governance. The Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines (the Guidelines), for example, highlight the role of entity Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) in developing a ‘strong fraud prevention culture within their agencies.’51 Similarly, the ANAO’s Better Practice Guide on Fraud Control in Australian Government Entities (the Fraud Control BPG) highlights the importance of leadership and organisational culture to the success of fraud control, and identifies the benefits of moving from the more traditional compliance-based approach to fraud control, to a contemporary approach.52

3.3 The traditional approach views fraud control as a compliance function, where a series of mandatory processes are undertaken by the entity in isolation of one another. The more contemporary approach recognises that an entity’s fraud control framework is most effective if fraud control strategies are integrated, supported by an entity’s culture, and effectively overseen. Table 3.1 contrasts the traditional and contemporary approaches.

Table 3.1 Traditional vs. contemporary fraud control approaches

|

Traditional fraud control |

Contemporary fraud control |

|

Fraud risk assessment is a static document only updated every two years. |

Fraud risk assessment is a living document which is updated through regular, targeted risk assessments. |

|

Fraud control plan is updated and ‘filed’ until the next biennial review. |

Ongoing fraud control where the fraud control plan is a living document, which is updated in lieu of fraud risk assessments. |

|

Fraud control plan is owned and managed by the Fraud Manager. |

Fraud control plan is ‘owned’ by the Executive. An entity’s Audit Committee provides independent assurance and advice to the CEO/Board on the operation of key controls and the fraud control plan to the extent that it is within its charter. The fraud control plan is managed by the Fraud Manager and referenced by all levels of management. |

|

Program development and delivery is not referenced by the fraud control plan, and programs do not consider fraud control at key stages in the program life cycle. |

Fraud control plan informs fraud risk assessment and fraud control strategies for key stages in the program life cycle, particularly in program design. |

|

Fraud awareness training is delivered to new staff at induction. |

Fraud awareness training is sponsored by the Senior Executive and conducted regularly under a risk-based approach. |

Source: ANAO Better Practice Guide—Fraud Control in Australian Government Entities, March 2011, Canberra.

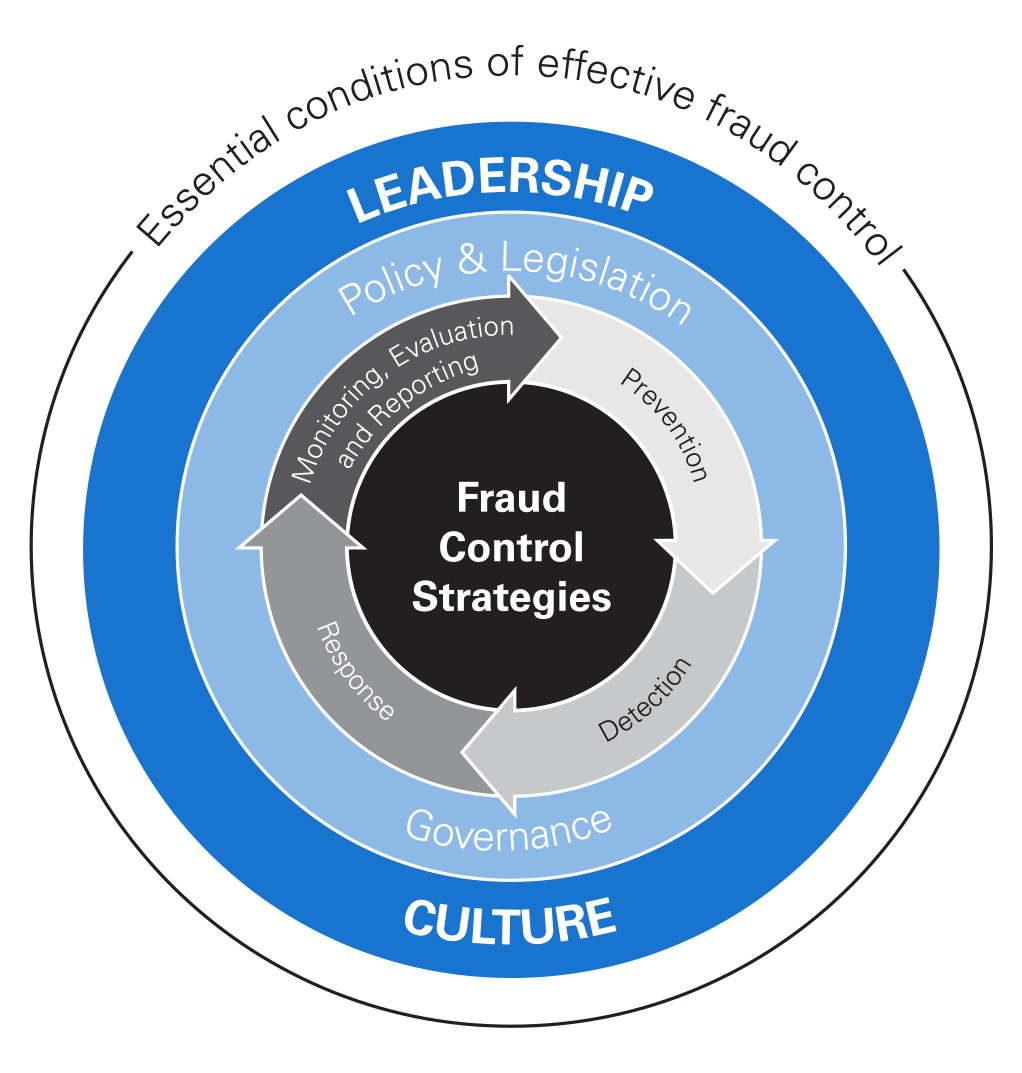

3.4 Central to the contemporary approach are four key fraud control strategies: prevention; detection; response; and monitoring, evaluation and reporting. These strategies are interdependent and should be subject to a cyclic process of review and enhancement (see Figure 3.1).53

Figure 3.1 Commonwealth fraud control framework

Source: ANAO Better Practice Guide, Fraud Control in Australian Government Entities, March 2011, Canberra.

3.5 The ANAO examined whether the selected entities had:

- an effective governance structure in place for the administration of the organisation’s fraud control arrangements, including that roles and responsibilities for fraud issues were clearly articulated;

- regularly assessed and monitored fraud risks;

- developed and implemented a comprehensive and contemporary Fraud Control Plan;

- developed and widely communicated, an informative fraud policy statement;

- promoted fraud awareness and provided relevant training to key personnel; and

- implemented key internal controls designed to prevent fraud or reduce the risks of fraud, and assessed whether the controls were operating as intended.

Governance

3.6 A contemporary approach to fraud control places effective governance at the centre of an entity’s fraud control arrangements. The 2011 Guidelines emphasised the role of the CEO in building a strong fraud prevention culture and making fraud control strategies an integrated part of their entity’s processes and practices.54 The Guidelines also highlighted the need for CEOs to satisfy themselves that their entity complied with the mandatory requirements of the Guidelines; a process generally relying on effective governance, administrative and oversight arrangements.

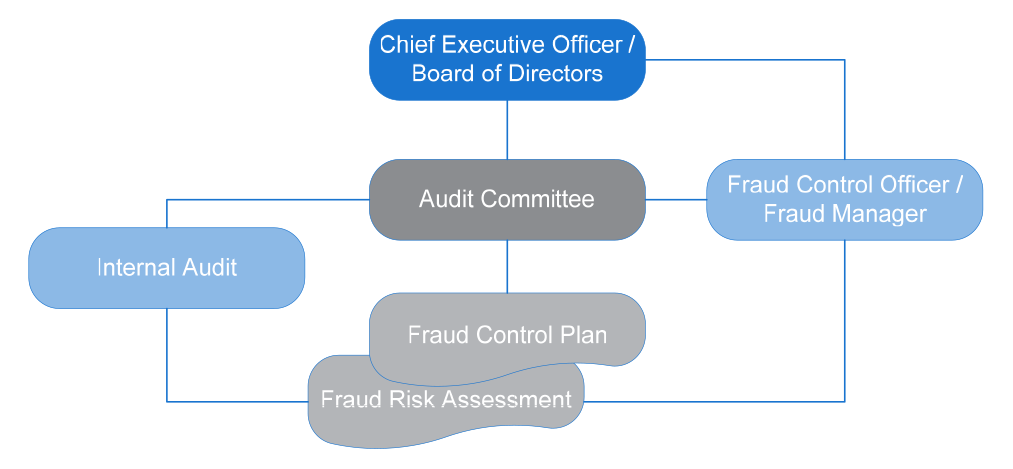

3.7 The importance of appropriate governance arrangements and leadership oversight are also key themes of the Fraud Control BPG. An entity’s executive leadership should ensure business processes, internal and external controls are established which reflect the entity’s risk exposure. These should be complemented by frameworks which allow for the effective monitoring and reporting of fraudulent activities, and the entity’s response.55 Figure 3.2 illustrates an example of an effective fraud governance structure.56

Figure 3.2 Fraud control governance structure

Source: ANAO Better Practice Guide—Fraud Control in Australian Government Entities, March 2011, Canberra.

Governance and administrative arrangements

3.8 The selected entities’ governance and administrative arrangements are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Austrade

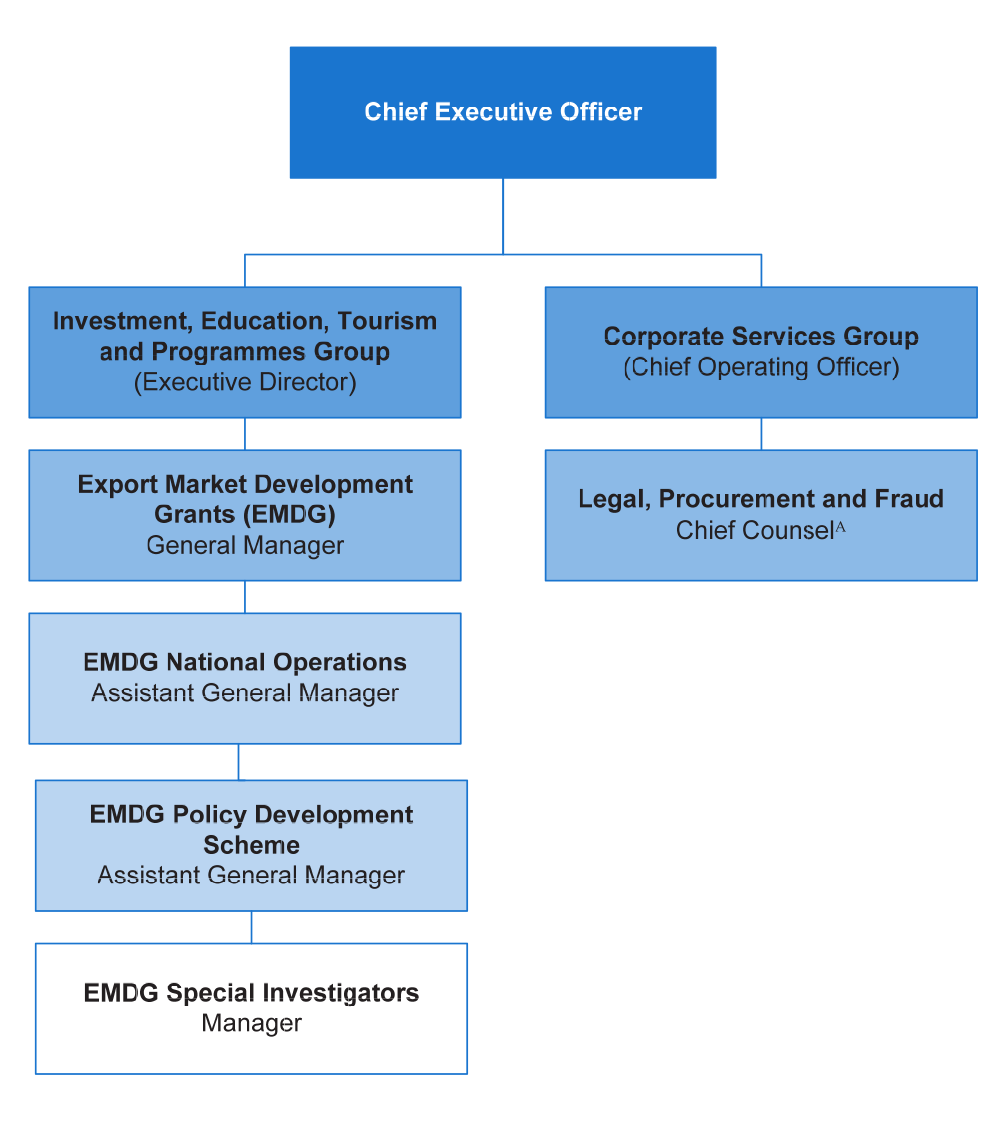

3.9 Austrade has implemented governance and internal administrative arrangements intended to address specific risks within the entity. At a whole-of-entity level, the fraud control function is administered by the Fraud Control Section located in the Legal, Procurement and Fraud Branch. In addition, the Export Management Development Grant (EMDG)57 branch had its own specific fraud control unit. Austrade advised the ANAO that EDMG had its own fraud control function due to the high fraud risk associated with this program (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3 Austrade’s fraud control governance and administrative arrangements

Source: ANAO summary of Austrade Organisation Chart.

Notes: A: Until 1 July 2014, Group Manager, Legal, Security and Procurement.

3.10 Austrade considers EMDG to be its major fraud risk, an assessment arising from the nature of the scheme, which involves the payment of grants to Australian businesses to develop export markets for their products. 58 Austrade further advised that EMDG has a dedicated Special Investigation Unit which is used on occasion to investigate suspected fraud in other areas of Austrade.59

3.11 While the split of fraud control functions between the EMDG Branch and the entity’s Fraud Control Section is deliberate, and is intended to help manage specific risks relating to the EMDG scheme, such an arrangement can present challenges in developing and implementing an integrated fraud control strategy across the entity. Austrade advised the ANAO that the fraud control function and the reporting of fraud is centralised to the role of Chief Counsel, Legal, Procurement and Fraud. Nonetheless, Austrade continues to report separately, to the Audit Committee and CEO, on the EMDG program and other entity fraud activities. Further, the ANAO’s interviews with Austrade’s fraud control staff, indicated that the central Fraud Control Section—which is responsible for Austrade’s overall fraud control strategy—was often not aware of fraud issues within the EMDG, contributing further to the risk of fragmentation in fraud control arrangements. There would be benefit in considering an approach involving more structured cross-communication between fraud units, to strengthen coordination arrangements.

3.12 Austrade’s CEO set out the entity’s approach to fraud control through the Chief Executive’s Instructions (CEIs)60, and the Fraud Control Plan is endorsed by the Audit and Risk Committee, prior to final approval by the CEO. At present, Austrade’s Executive is informed of the entity’s fraud issues through the Audit and Risk Committee which, as discussed, obtains separate reports on fraud from both the EMDG branch and the Fraud Control Section.61

3.13 In the course of the audit, Austrade advised the ANAO that an internal review of fraud control arrangements will examine consistency with the Guidelines and ANAO Better Practice Guide, and addressing the risk of fragmentation between fraud management arrangements for EMDG and other parts of Austrade.

Comcare

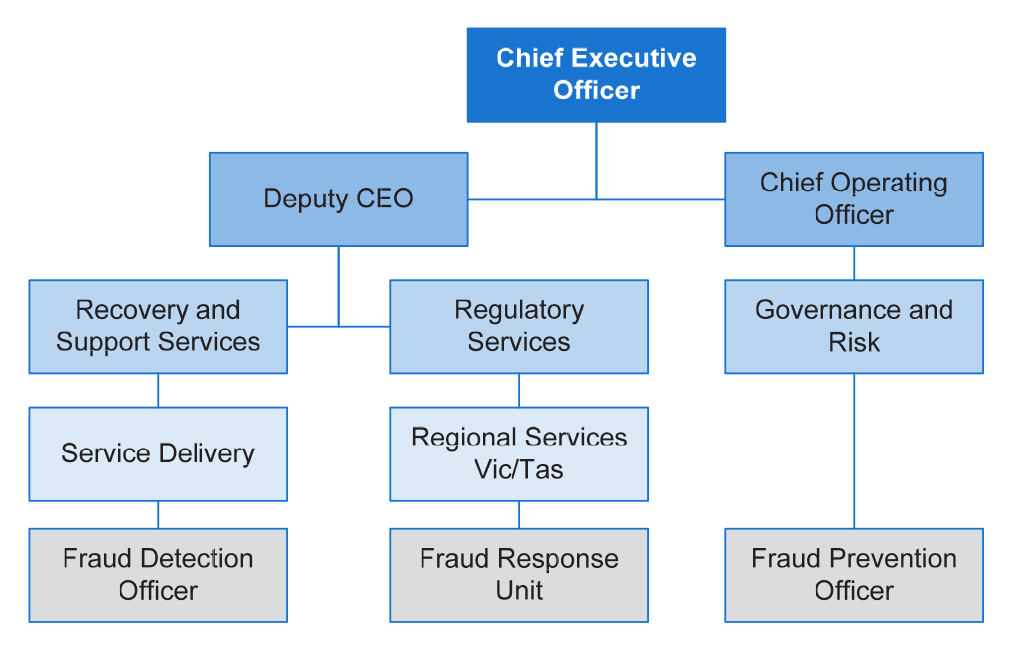

3.14 In 2012, Comcare commenced a restructure of its fraud control governance and operations to better reflect the more contemporary approach to fraud management. At the time of the ANAO’s fieldwork for this audit, Comcare was in the final stages of this restructure (Figure 3.4).

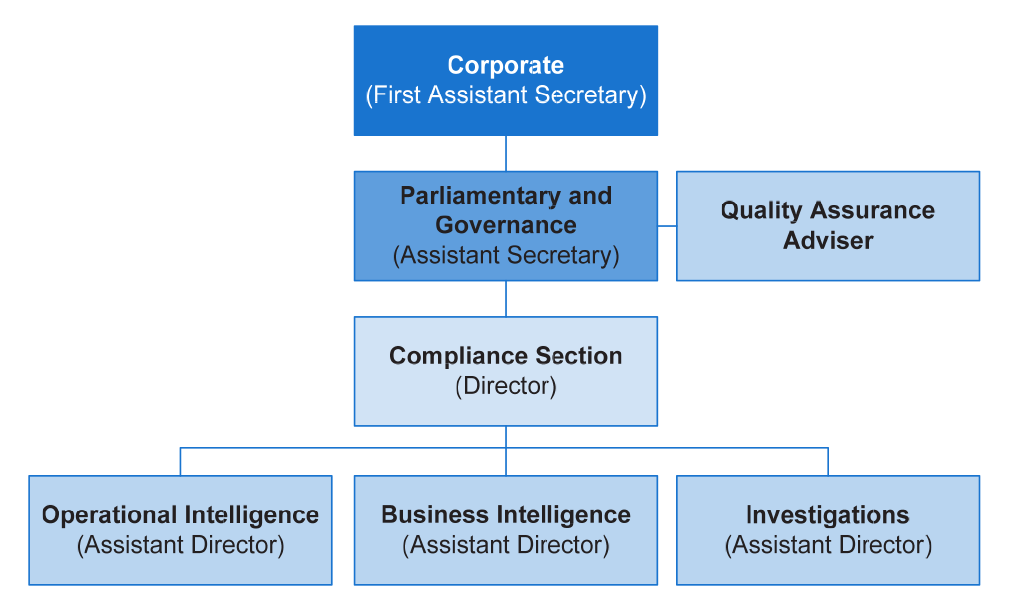

Figure 3.4 Comcare’s fraud control governance and administrative arrangements

Source: Comcare Fraud Control Plan 2013–15.

3.15 Comcare advised the ANAO that its restructure was driven by the entity’s CEO and senior executives, and aimed to establish a culture of fraud awareness at all levels of the entity, with fraud control forming a key component of Comcare’s governance structure.

3.16 Under the revised arrangements, overall coordination of fraud control within Comcare is the responsibility of the Director of Governance, Audit and Risk, and the entity’s Fraud Prevention Officer reports to the Director. Fraud Operations Teams are located in all of Comcare’s Divisions and are responsible for fraud prevention; detection; investigation and monitoring activities. The Fraud Prevention Officer has the role of coordinating and assisting Fraud Operations Teams in identifying fraud risks and implementing controls. Overall, the new structure facilitates a coordinated and entity-wide approach to fraud control.

3.17 While day-to-day responsibility for fraud control within Comcare is delegated to the Director of Governance, Audit and Risk, the CEO and Executive continue to play a key role. Comcare’s Executive Committee is responsible for endorsing the entity’s Fraud Control Plan, prior to presenting it to the CEO for final approval. Fraud Operations Teams are also required to report directly to the CEO and Deputy CEO on sensitive fraud related issues as they arise.

DVA