Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Expansion of Telehealth Services

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- In 2020 medical services delivered by phone and video (telehealth) were significantly expanded as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The expansion was described as ’10 years of reform in only 10 days’ and the ‘most significant structural reform to Medicare since it began’.

- The audit provides assurance over the rapid implementation of policy changes and transition from emergency to permanent settings

Key facts

- Telehealth expansion involved amending items listed on the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS).

- In March–May 2020, 281 temporary telehealth MBS items were created. The items were extended as the pandemic continued.

- In January 2022, 211 telehealth items were retained permanently.

What did we find?

- The Department of Health and Aged Care (Health) expanded telehealth to meet objectives, however there were shortfalls in governance, risk management and evaluation.

- The expansion of telehealth was informed by largely robust policy advice and planning.

- The expansion was partly supported by sound implementation arrangements.

- Health did not adequately monitor or evaluate the expansion.

What did we recommend?

- There were four recommendations relating to the governance of MBS changes, risk management and evaluation of the temporary and permanent telehealth expansion.

- Health agreed to three recommendations and agreed in-principle to one recommendation.

28

Days between activation of COVID-19 emergency plans and a decision to extend telehealth to the entire population.

16.5%

Proportion of MBS services provided via telehealth April–June 2020 (vs. 0.06% in April–June 2019)

31.0%

Proportion of general practice MBS services provided via telehealth April–June 2020 (vs. 0.04% in April–June 2019)

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Medicare is Australia’s national health insurance scheme. Medicare rebates are payable for health services that are specified as items on the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, between March 2020 and May 2020 the Australian Government introduced 281 new telehealth items on the MBS to enable the entire Medicare-eligible population to access a broad range of health services via videoconferencing and phone rather than face-to-face with a provider. Although the temporary telehealth items introduced in response to COVID-19 were initially scheduled to expire on 30 September 2020, the Australian Government postponed their expiry on three occasions in 2020 and 2021.

2. On 13 December 2021 the Minister for Health and Aged Care announced that telehealth would become a permanent feature of Medicare, noting that since March 2020 over 86.3 million telehealth items introduced in response to COVID-19 had been billed for services delivered to 16.1 million patients by over 89,000 providers, totalling $4.4 billion in Medicare benefits. The 2022–23 Budget described the introduction of permanent telehealth as the ‘most significant structural reform to Medicare since it began.’

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. The COVID-19 pandemic and the pace and scale of the Australian Government’s response impacts on the risk environment faced by the Australian public sector. This performance audit was conducted under phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. The expansion of telehealth services in 2020 to provide whole of population access to health services during the COVID-19 pandemic has been described by the Department of Health and Aged Care (Health) as ‘10 years of reform in only 10 days’. Rapid implementation of policy changes can increase risks to effective and efficient delivery of public services. The audit was conducted to provide assurance to Parliament over the rapid implementation of health policy changes during a pandemic and the transition from emergency to permanent arrangements.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess whether the Department of Health and Aged Care has effectively managed the expansion of telehealth services during and post the COVID-19 pandemic.

6. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria.

- Was the expansion informed by robust planning and policy advice?

- Was the expansion supported by sound implementation arrangements?

- Has monitoring and evaluation of the expansion led to improvements?

7. The audit scope did not include Services Australia’s administration of telehealth benefit payments, or telehealth services outside of those listed on the MBS (such as those managed by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs). The audit examined the incorporation of telehealth integrity risks into Health’s provider compliance arrangements but did not evaluate the effectiveness of compliance activities.

Conclusion

8. The Department of Health and Aged Care expanded telehealth services during and post the COVID-19 pandemic to meet the Australian Government’s objectives of continued access to essential health services and flexible health care, however there were shortfalls in the governance, risk management and evaluation of the expansion.

9. The temporary and permanent expansion of MBS telehealth items was informed by largely robust policy advice and planning. Policy advice to government on temporary telehealth services introduced in response to COVID-19 considered stakeholder views, although it did not present a structured assessment of risks or options for decision. Policy advice on permanent telehealth maintained focus on objectives, largely considered stakeholder opinions, and assessed the costs and benefits of different options. The implementation of temporary and permanent telehealth was based on business as usual processes for changes to MBS items, and there was no implementation plan for temporary telehealth. There was a high-level implementation plan for the permanent expansion of telehealth, although this did not adequately address evaluation.

10. Health implemented significant changes to the MBS and in doing so provided largely appropriate support to delivery partners. However, the telehealth expansion was only partly supported by sound implementation arrangements. Although Health conducted risk-based post-payment compliance activities, the governance arrangements for the implementation of temporary telehealth involved inadequate assessment of the implementation and integrity risks.

11. Health did not plan for performance monitoring or evaluation of temporary or permanent telehealth. Performance monitoring of the temporary telehealth expansion was limited and lacked measures and targets that could inform judgements about performance, and there was no evaluation that could assist with the design and implementation of potential expansions to telehealth during future emergency conditions. Evaluation of permanent telehealth is developing.

Supporting findings

Planning and policy advice

12. Health provided policy advice that was consistent with the Australian Government’s evolving policy objectives for temporary and permanent telehealth. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.7)

13. In the urgent timeframe of the initial pandemic response, Health advised the Minister for Health on the costs but only some of the benefits and risks of temporary telehealth policy settings. Health presented one option for decision by the Australian Government concurrently with proposals for several other pandemic response measures. The assessment of temporary COVID-19 telehealth policy option risks between March 2020 and May 2021 was partly compliant with Australian Government budget policy. Health presented five policy options for permanent telehealth that articulated risks, benefits and costs. Assessment of permanent telehealth policy option risks was compliant with budget policy. (See paragraphs 2.8 to 2.26)

14. Health consulted with and incorporated the opinions of peak bodies into policy advice for temporary and permanent telehealth. Consultation on temporary telehealth occurred within short timeframes. For general practice and allied health permanent telehealth, consultation practices were largely aligned with a stakeholder engagement plan. For specialist permanent telehealth, there was no finalised stakeholder engagement plan, however consultations occurred, and views were reflected in policy advice. State and territory governments were involved in high level discussions but were largely not consulted on the details of changes to MBS items. A key Indigenous peak body was not involved in stakeholder meetings where the specifics of telehealth policy settings were discussed. Health used pre-pandemic experience with telehealth, and experience arising from the pandemic, to inform policy proposals. (See paragraphs 2.27 to 2.45)

15. In introducing temporary telehealth in response to COVID-19, Health followed existing processes associated with section 3C determinations under the Health Insurance Act 1973 without a documented implementation plan. Implementation stages and milestones for both temporary and permanent telehealth were described at a high level in advice to government. The high-level advice to government did not set out how the changes would be evaluated. Health aligned planning for permanent telehealth with other plans for primary health care reform. The implementation plan for permanent telehealth has been subject to multiple changes, including in response to the ongoing pandemic. (See paragraphs 2.46 to 2.58)

Implementation arrangements

16. Standard procedures used by Health to implement telehealth changes to the MBS did not require key implementation decisions and plans to be documented, implementation and integrity risks to be managed, or performance monitoring and evaluation plans to be considered. As a result, Health’s governance arrangements for the expansion of telehealth were not fit-for-purpose. Health’s project management framework provides suitable governance arrangements, but it was not used. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.20)

17. Health did not manage implementation risks associated with temporary or permanent telehealth changes in accordance with its risk management policy. (See paragraphs 3.21 to 3.33)

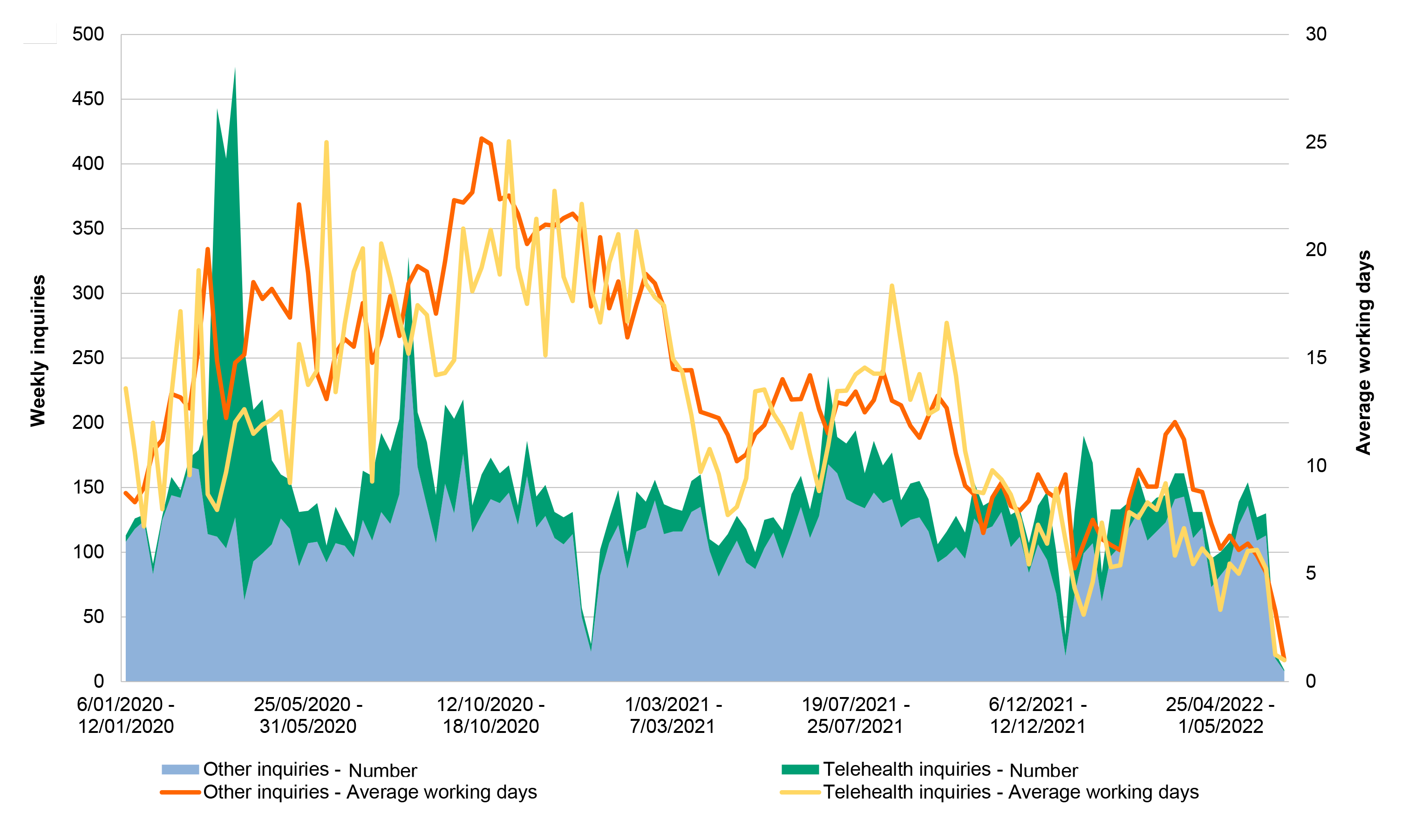

18. Although Health did not consistently adhere to the agreed process to govern the implementation of changes to the MBS by Services Australia, Health supported Services Australia to make rapid changes to MBS telehealth items during the initial expansion of temporary telehealth. While there was no communications plan, Health published a substantial amount of guidance material for health providers and maintained a facility for provider enquiries. Between 30 March 2020 and 12 June 2022, service standards for responding to telehealth-related inquiries were not consistently met. (See paragraphs 3.34 to 3.48)

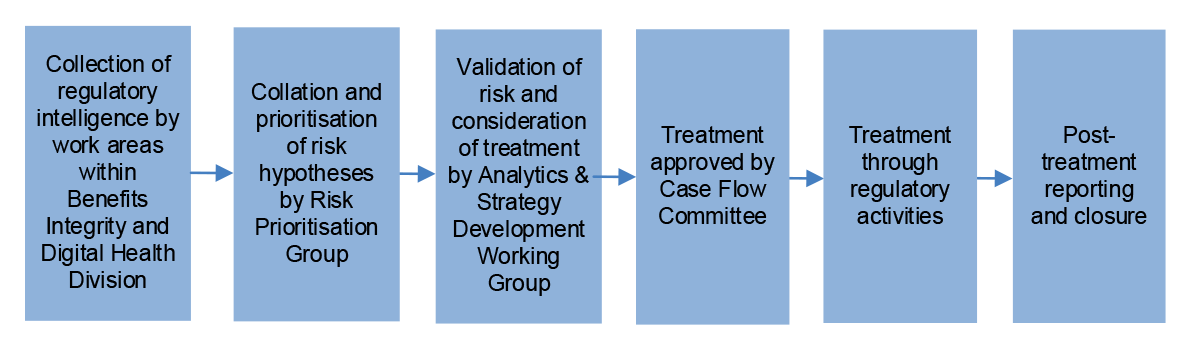

19. Health did not conduct a risk assessment of integrity risks, such as provider fraud and non-compliance, prior to implementing the temporary and permanent MBS telehealth items. Treatments to prevent provider non-compliance with telehealth items were limited. There is a risk-based model for detecting and treating provider fraud and non-compliance. Corrective non-compliance treatments were applied to a subset of non-compliant providers in accordance with this model and focused on the most egregious non-compliance behaviours. (See paragraphs 3.49 to 3.59)

Monitoring and review

20. Health did not establish performance measures for the telehealth expansion. Health used MBS billing data to monitor telehealth usage patterns, on the assumption that telehealth usage and billing behaviours were sufficient indicators of successful telehealth implementation. There were no performance targets. (See paragraphs 4.4 to 4.17)

21. Health did not develop an evaluation plan for temporary telehealth or for permanent telehealth. Telehealth policy proposals did not address evaluation in detail. Health has not coherently evaluated the effectiveness of telehealth as a pandemic response, although some analysis of billing data and independent research has been undertaken. Health used some reviews and data analysis to inform decision making on permanent telehealth. Health’s plans to evaluate permanent telehealth were not settled as at September 2022. (See paragraphs 4.18 to 4.32)

Recommendations

22. This report makes four recommendations to Health.

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.18

The Department of Health and Aged Care strengthen its systems of control for the implementation of material changes to the Medicare Benefits Schedule, to embed elements of governance that are currently unaddressed including documentation of key implementation issues and decisions, and planning for performance monitoring and evaluation.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.32

The Department of Health and Aged Care develop procedures that ensure proposed material changes to the Medicare Benefits Schedule are subject to a structured and documented risk assessment that covers implementation, integrity and other risks.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.20

As a component of a broader review into the COVID-19 pandemic response required under the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus, the Department of Health and Aged Care considers the lessons learned for future pandemic preparedness from the inclusion of temporary telehealth items as one of several COVID-19 pandemic response measures.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed in-principle.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 4.31

The Department of Health and Aged Care finalise its plans to evaluate permanent telehealth.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

The Department of Health and Aged Care acknowledges the ANAO findings while also recognising the unique scenario of the COVID19 emergency health response. The Department delivered on its objectives to maintain patients’ access to essential health services throughout lockdowns as well as reducing risk of transmission for patients and providers. To date, over 132 million services have been provided via telehealth, with the Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS) items replicating the requirements of face-to-face items for clinical appropriateness and integrity. This was informed by regular consultation with stakeholders, expert advice, and available research forming the basis of advice to Government as part of the initial health crisis and beyond.

The rapid deployment of MBS telehealth measures, ensuring access to essential health care services and protecting the capacity of the health system, was in alignment with the ‘Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus’. The key messages for all Australian Government entities are also noted, emphasising the requirements despite urgent implementation deadlines.

The MBS, and the telehealth services within it, are demand driven services that respond to patient need and any assertion in relation to targets would run counterproductive to this. The suitability of telehealth, noting it mirrors face to face items to provide access to care, at any given time for a patient consultation is a clinical judgement by a practitioner with respect to their patient’s care, and outside the remit of the Department.

The alignment of MBS telehealth items with contemporary clinical practice is subject to ongoing refinement and evaluation through a post-implementation review. The Minister for Health and Aged Care, the Hon Mark Butler MP, has formally requested the MBS Review Advisory Committee undertake this work, with a report back to Government in late 2023.

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Policy design

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Medicare is Australia’s national health insurance scheme. Under the scheme, patients may claim a rebate (referred to as a benefit) for specified health or medical services. Services covered by Medicare benefits are detailed in legislation and are collectively known as the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS). Each service listed in the MBS has an item number, a descriptor which outlines the type and scope of the service, the Medicare schedule fee1 and the Medicare benefit (rebate).2

1.2 As the administering department for the Health Insurance Act 1973, the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (Health) is responsible for advising the Australian Government on proposals to add, amend or remove health services listed on the MBS, implementing changes to the MBS as directed by the Australian Government, and ensuring that health providers3 are claiming rebates in accordance with the MBS. Medicare claims and payments are administered by Services Australia, which is directly accountable to the Australian Government for service delivery of programs such as Medicare. Health and Services Australia maintain a program agreement for administration of the Medicare program, which forms part of a joint Statement of Intent between the two entities.

1.3 The MBS has featured a limited range of telehealth service items since 2002. In this report ‘telehealth’ refers to real time clinical consultations conducted via videoconferencing or phone rather than face-to-face. The MBS defines a service via videoconference as ‘telehealth attendance’ and a service via telephone as ‘phone attendance’.

1.4 In late 2019 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged as a global pandemic and was declared to be a ‘public health emergency of international concern’ by the World Health Organization on 30 January 2020. From January 2020 the Australian Government commenced the introduction of a range of policies and measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Australian Government’s health and economic response has included:

- travel restrictions, international border controls and quarantine arrangements;

- delivery of substantial economic stimulus, including financial support for affected individuals, businesses and communities; and

- support for essential services and procurement and deployment of critical medical supplies (including the national vaccine rollout).

1.5 In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, between March and May 2020 the Australian Government introduced 281 new telehealth items on the MBS to enable the entire Medicare-eligible population to access a broad range of health services via videoconferencing and phone. Although the temporary telehealth items introduced in response to COVID-19 were initially scheduled to expire on 30 September 2020, the Australian Government postponed their expiry on three occasions in 2020 and 2021.

1.6 On 13 December 2021 the Minister for Health and Aged Care4 (the Minister) announced that telehealth would become a permanent feature of Medicare, noting that since March 2020 over 86.3 million telehealth items introduced in response to COVID-19 had been billed for services delivered to 16.1 million patients by over 89,000 providers, totalling $4.4 billion in Medicare benefits. The 2022–23 Budget described the introduction of permanent telehealth as:

the most significant structural reform to Medicare since it began, and has revolutionised the patient-doctor relationship. It is one of the most significant, long term benefits of the Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, providing all Australians with improved access to health services.

Telehealth prior to February 2020

1.7 In 2002 the Australian Government added telehealth psychiatry items to the MBS. In the 2011–12 Budget telehealth services were expanded to a broader range of specialists. The telehealth items were primarily directed at patients in remote and regional areas, residents of aged care facilities in remote and regional locations, and patients of Aboriginal medical services5 regardless of location. The telehealth items were provided over videoconference, including ‘patient-end’ support services provided in general practice.6 Some of the telehealth items required the provider to have an existing clinical relationship with the patient (defined as three face-to-face consultations with that provider in the preceding 12 months).

1.8 Between 1 November 2018 and 30 June 2020 the MBS contained mental health services provided to patients in drought affected areas7 by videoconference. In January 2020 the Australian Government expanded these MBS telehealth services to patients who experienced an adverse change in mental health as a result of bushfires occurring in 2019–20.

1.9 None of the telehealth services listed in paragraphs 1.7 to 1.8 could be provided by phone, or were subject to a requirement that the service be bulk billed.

Telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic response

1.10 On 17 February 2020 the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee8 endorsed the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) (COVID-19 Plan). The COVID-19 Plan provided that the Australian Government and state and territory governments would work together to develop new models of care to manage patients during the COVID-19 pandemic and ensure that the provision of primary health care would be adapted to any changes in the needs of vulnerable groups during the outbreak. On 27 February 2020 the Prime Minister announced the activation of the ‘Targeted Action’ stage of the COVID-19 Plan. Health immediately commenced development of a National Primary Care Targeted Action Plan, which proposed six measures to be adopted as part of an overarching strategy for providing primary care during the pandemic. One of the six measures was the creation of temporary MBS items for medical, nursing and mental health attendances delivered via telehealth.

Telehealth for those vulnerable to COVID-19

1.11 On 11 March 2020 the Prime Minister announced that the Australian Government had allocated $100 million in funding for new Medicare telehealth services. The announcement noted that the new Medicare telehealth services would be available via phone or video; bulk billed; and available to people in home isolation or quarantine as a result of coronavirus, as well as specified vulnerable patient groups9 regardless of their home isolation or quarantine status.

1.12 Between 12 and 24 March 2020 the Minister and Health made nine determinations under section 3C of the Health Insurance Act 1973 (3C determinations) to implement this package.10 The 3C determinations specified that services should be provided by videoconference, or by phone where suitable videoconference capabilities were not available. The items could be claimed only if the service was bulk billed, the patient was not admitted to hospital; and there was an existing clinical relationship (defined as one face-to-face consultation in the preceding 12 months). Initially the telehealth items also could be used for any patient if the provider had been infected by COVID-19 or was required to self-isolate, to prevent the provider from transmitting COVID-19 to a patient. On 23 March 2020 Health expanded the eligibility for providers to align it with the definition for vulnerable patients.11

Whole of population telehealth in response to COVID-19

1.13 On 18 March 2020 the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia declared that a human biosecurity emergency exists.12 Between 18 and 22 March 2020 the Australian Government announced restrictions on commercial and social gatherings, the closure of Australia’s international borders to non-residents and non-citizens, new measures aimed at preventing panic-buying of medicines, and economic stimulus and industry support packages.13

1.14 The Minister announced on 23 March 2020 that the Australian Government was examining the expansion of temporary telehealth to the whole population, and on 30 March 2020 that temporary telehealth services would be extended to all persons eligible for Medicare services. A new 3C determination expanded the range of medical services that could be provided by videoconference or phone; removed requirements for providers to have an existing clinical relationship with the patient; and inserted a restriction to prevent items being billed for services with multiple patients simultaneously.14

1.15 The requirement to bulk bill the new temporary telehealth services was retained for a further week before being limited to concessional and vulnerable patients from 6 April 2020 onwards. The bulk billing requirement was removed completely for specialists, allied health and other specified providers from 20 April 2020.

1.16 Between 3 April and 19 May 2020 the Minister and Health made seven further 3C determinations that expanded the range of services available and corrected errors with previous instruments. By 22 May 2020, 281 telehealth items had been created in response to COVID-19.

Maintenance of COVID-19 telehealth

1.17 As the new telehealth items were originally conceived as a six-month temporary measure, in May 2020 Health commenced planning for the expiry of these items by September 2020. However, due to the ongoing pandemic, the expiry date of the temporary telehealth items was extended in September 2020 (to 31 March 2021), March 2021 (to 30 June 2021) and June 2021 (to 31 December 2021).

1.18 During this period, Health made adjustments to temporary telehealth services, including:

- reintroduction of the requirement for providers of non-referred services to have a pre-existing clinical relationship with the patient15;

- removal of the requirement for providers in general practice to bulk bill telehealth services for concessional and vulnerable patients;

- curtailment of the range of services that could be delivered by phone (as opposed to videoconference);

- introduction of general practice phone items for patients located in a COVID-19 hotspot declared by the Australian Government Chief Medical Officer; and

- introduction of 40 new temporary MBS telehealth services for specialists providing services to private patients admitted to hospital, where the specialist was located in a COVID-19 hotspot or was in mandatory isolation due to COVID-19.

Permanent telehealth

1.19 In June 2020 the Prime Minister wrote to the Minister to advise:

Due to our success in suppressing the spread of the coronavirus and our commitment to transitioning to a COVID-safe economy and society…I consider there is a diminishing need for further [temporary COVID-19] telehealth items. I ask that you seek my agreement to any further changes ahead of a strategic discussion on the future of telehealth and post-COVID-19 primary health care reform…

1.20 Health planned for the incorporation of telehealth as a core initiative in the Australian Government’s primary health care reform package that had been announced in May 2019. The package included the finalisation of a Primary Health Care 10 Year Plan, which would provide a national roadmap for primary health care policy and planning.

1.21 In October 2021 Health released a consultation draft of the Primary Health Care 10 Year Plan, which proposed the continuation of whole of population telehealth on a permanent basis. The consultation draft expressed an intent to increase the uptake of video for telehealth service delivery, and proposed that the requirement for a general practice provider to have an existing clinical relationship with a telehealth patient would be replaced by voluntary patient registration.16

1.22 On 13 December 2021 the Minister announced that whole of population telehealth would become a permanent feature of Medicare. On 16 December 2021 Health made a 3C determination to permanently retain 211 telehealth items used during 2021.

1.23 Sixteen days after the permanent arrangements commenced, the Australian Government announced it would temporarily reinstate 75 temporary videoconference and phone services that had been permitted to expire on 31 December 2021, in response to a spike in Omicron-variant COVID-19 cases.

1.24 Figure 1.1 depicts the developments in telehealth between January 2020 and June 2022.

Figure 1.1: The expansion of telehealth, January 2020 to June 2022

Note: Stages refer to telehealth expansion implementation stages outlined in a Health fact sheet and other Health documentation (see paragraphs 2.50 to 2.51).

Source: ANAO analysis.

Usage of telehealth items

1.25 Figure 1.2 depicts the dollar value of benefits paid for telehealth services introduced in response to COVID-19.

Figure 1.2: Value of benefits paid for telehealth items introduced in response to COVID-19, January 2020 to June 2022

Source: ANAO analysis of Services Australia data.

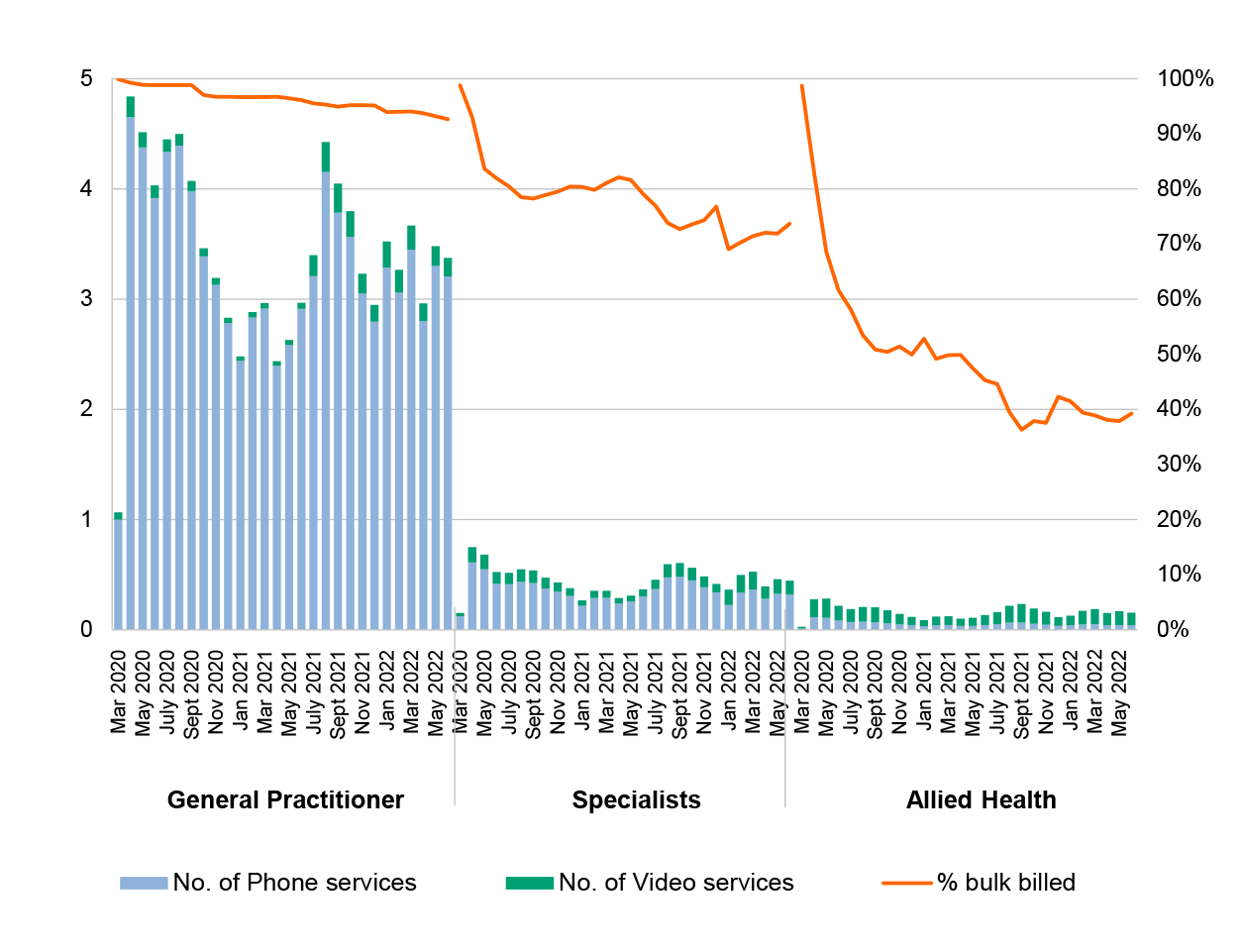

1.26 Figure 1.3 depicts the billing of telehealth items introduced in response to COVID-19 by general practitioners, specialists, and allied health professionals between 1 March 2020 and 30 June 2022. The majority of GP and specialist telehealth services were delivered by phone during this period.

Figure 1.3: Medicare Benefits Schedule COVID-19 telehealth item billing, March 2020 to June 2022

Source: ANAO analysis of Services Australia data.

1.27 As a proportion of all MBS services delivered by general practitioners between March 2020 and June 2022, telehealth represented approximately 20 to 30 per cent, depending on the quarter (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4: Mode of MBS service delivery, July 2019 to June 2022

Note: Telehealth services preceding 1 January 2020 are not visible in the chart as they comprised less than 0.1 per cent of total services for GPs and all practitioners.

Source: ANAO analysis of Services Australia data.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.28 The COVID-19 pandemic and the pace and scale of the Australian Government’s response impacts on the risk environment faced by the Australian public sector. This performance audit was conducted under phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.17

1.29 The expansion of telehealth services in 2020 to provide whole of population access to health services during the COVID-19 pandemic has been described by Health as ‘10 years of reform in only 10 days’. Rapid implementation of policy changes can increase risks to effective and efficient delivery of public services. The audit was conducted to provide assurance to Parliament over the rapid implementation of health policy changes during a pandemic and the transition from emergency to permanent arrangements.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.30 The audit objective was to assess whether the Department of Health and Aged Care has effectively managed the expansion of telehealth services during and post the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.31 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Was the expansion informed by robust planning and policy advice?

- Was the expansion supported by sound implementation arrangements?

- Has monitoring and evaluation of the expansion led to improvements?

1.32 The audit examined whether appropriate treatments were applied to telehealth-specific integrity risks, however did not examine the effectiveness of these treatments or the treatment of broader integrity risks that are generic to all MBS items. The audit did not examine Services Australia’s administration of benefit payments, or telehealth services or subsidies not listed on the MBS.

Audit methodology

1.33 The audit involved:

- reviewing submissions and briefings to government;

- reviewing other entity documentation, including meeting papers and minutes, policies and procedures, and correspondence;

- analysing administrative data held in entity systems, including Health’s case management system for provider integrity activities;

- meetings with officers from relevant business areas within Health and Services Australia;

- analysing de-identified MBS transactional data provided by Services Australia;

- meetings with representatives of state and territory health departments with responsibilities relating to telehealth; and

- reviewing 31 submissions received by the ANAO from organisations and individuals.

1.34 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $637,000.

1.35 The team members for this audit were Michael McGillion, Kai Swoboda, Sam Jones, Dr Jennifer Canfield, Bezza Wolba, Alicia Vaughan, Daniel Whyte and Christine Chalmers.

2. Policy advice and planning

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the temporary and permanent expansion of Medicare Benefits Schedule telehealth services was informed by robust policy advice and planning.

Conclusion

The temporary and permanent expansion of Medicare Benefits Schedule telehealth items was informed by largely robust policy advice and planning. Policy advice to government on temporary telehealth services introduced in response to COVID-19 considered stakeholder views, although it did not present a structured assessment of risks or options for decision. Policy advice on permanent telehealth maintained focus on objectives, largely considered stakeholder opinions, and assessed the costs and benefits of different options. The implementation of temporary and permanent telehealth was based on business as usual processes for changes to Medicare Benefits Schedule items, and there was no implementation plan for temporary telehealth. There was a high-level implementation plan for the permanent expansion of telehealth, although this did not adequately address evaluation.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two suggestions to the Department of Health and Aged Care regarding compliance with Australian Government budget policy requirements to assess the risk of new policy proposals, and stakeholder consultation for co-designed initiatives.

2.1 The Australian Government’s Delivering Great Policy model18 specifies that when providing policy advice, agencies should clearly define the objectives of a proposed policy; provide options that identify the key risks and benefits; collaborate with people affected by the policy; incorporate lessons from past experience; and provide a practical plan for implementation. Implementation plans should identify deliverables and milestones and embed evaluation at the outset.

2.2 A 2015 independent review of Australian Government processes for the development and implementation of large public programmes and projects noted that ‘informed decision making requires assessment of the specific risks being accepted and the broader context’.19

Was policy advice consistent with the Australian Government’s objectives?

The Department of Health and Aged Care provided policy advice that was consistent with the Australian Government’s evolving policy objectives for temporary and permanent telehealth.

2.3 To assess whether the Department of Health and Aged Care’s (Health’s) policy advice was consistent with policy objectives, the ANAO reviewed how Health described the purpose of proposed changes to telehealth in advice given to the Australian Government in policy briefings and ministerial submissions, as well as in government announcements, approval minutes, portfolio budget statements and explanatory statements for determinations made under section 3C of the Health Insurance Act 1973 (3C determinations).20

Temporary telehealth

2.4 Between March 2020 and February 2022 the government had several policy objectives for temporary telehealth.

- Late February to early March 2020 — the objective was to enable continued access to essential health services for vulnerable populations, while mitigating the risks of vulnerable patients being exposed to COVID-19 and patients who are required to self-isolate or quarantine exposing others to COVID-19.

- Late March to May 2020 — the objective was to enable continued access to essential health services for the whole population, while controlling the spread of COVID-19.

- June 2020 to December 2021 — the objective was to continue to control the spread of COVID-19. This would involve making limited changes to temporary telehealth settings including extensions to temporary telehealth, as informed by advice from the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee. Any telehealth proposals that were not necessary to suppress COVID-19 were to be incorporated into future policy advice on permanent telehealth as part of long-term health reform plans.

2.5 Health’s policy advice and communications between 9 March 2020 and 14 September 2021 contained statements of purpose that aligned with these objectives and followed the Australian Government’s evolving priorities for temporary telehealth.

Permanent telehealth

2.6 Between late 2021 and February 2022 the Australian Government’s policy objective for permanent telehealth was to improve flexible access to health services for all Australians.

2.7 Health’s policy advice and communications between November 2021 and February 2022 contained statements of purpose that aligned with this objective. Advice and communications after 18 December 2021 noted that this objective remained in place despite the Australian Government’s decision to reinstitute certain temporary telehealth items in response to the Omicron outbreak and delay the introduction of some permanent telehealth measures (such as the introduction of new compliance measures).

Were the costs, benefits and risks of different policy options considered?

In the urgent timeframe of the initial pandemic response, the Department of Health and Aged Care advised the Minister for Health on the costs but only some of the benefits and risks of temporary telehealth policy settings. Health presented one option for decision by the Australian Government concurrently with proposals for several other pandemic response measures. The assessment of temporary COVID-19 telehealth policy option risks between March 2020 and May 2021 was partly compliant with Australian Government budget policy. Health presented five policy options for permanent telehealth that articulated risks, benefits and costs. Assessment of permanent telehealth policy option risks was compliant with budget policy.

Telehealth as part of the COVID-19 pandemic response

2.8 Health considered several options before developing a proposal to expand telehealth services as a pandemic response measure. On 28 February 2020 the Chief Medical Officer for the Australian Government asked Health officials to consider how telehealth services could be used as a response for the pandemic. Health identified an initial four options involving the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) (two introducing new telehealth MBS items to substitute for face-to-face services and two introducing new items for home visits for isolating patients), and two options that did not involve the MBS. Initial briefs to Health senior executives contained a short, high-level analysis of issues associated with these options, covering eligible populations, compliance risks, implementation considerations and cost impacts.

2.9 On 3 March 2020 the Minister through his office instructed Health to include ‘time-limited MBS items for telehealth in pandemic response planning’. Within seven days Health developed a policy proposal for expanded telehealth services alongside 17 other response measures. Advice on the proposed policy was presented to the Australian Government on 9–10 March 2020.

- Issues discussed included the requirement for patients to have a pre-existing face-to-face relationship with the provider and mandatory bulk billing.

- The advice covered the one option of telehealth delivered via videoconferencing. Health expressed a preference for videoconferencing over phone telehealth due to clinical risks associated with the latter.

- The advice did not explain the benefits of the proposed policy settings.

- The advice highlighted one risk specific to telehealth (that providers and patients may lack experience with videoconferencing) and noted that services could be delivered through widely-available video calling applications.

- The advice made a generic statement that compliance risks of the proposal would be adequately addressed by existing Medicare compliance procedures and audit protocols.

2.10 The Department of Finance agreed with Health’s view that the proposed policy would be cost-neutral on the basis that telehealth services would substitute for existing face-to-face services. Health advised the Australian Government that, as there was an element of uncertainty about how telehealth services would be taken up, a provision of $100 million should be set aside for a potential increase in MBS costs.

2.11 Health received approval to implement telehealth services in line with its policy advice on 10 March 2020.

2.12 On 11 March 2020 the Prime Minister announced that telehealth services would include both videoconferencing and phone services. The requirement to include phone services was unanticipated by Health. In response to the Prime Minister’s announcement, Health rapidly introduced phone telehealth items to the MBS with a requirement that these services could only be billed where providers and patients did not have the capability to undertake the service via videoconference. Health officials advised the ANAO that this requirement was largely unenforceable.

2.13 Following discussions with the Australian Medical Association and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, on 23 March 2020 the Minister announced that eligibility for telehealth was expected to be expanded to the whole Medicare-eligible population. Working with the Minister’s office, Health prepared formal advice for the Australian Government in line with the Minister’s announced approach.

- Similar to the previous advice, the advice examined one policy option and stated that integrity risks would be adequately addressed through existing compliance arrangements.

- Compared to previous advice, the advice contained greater detail on the benefits and risks of certain proposed policy settings such as removing the requirement for the provider and patient to have an existing clinical relationship.

- The advice identified as a risk that progressive implementation of telehealth MBS items might be required due to capacity constraints within Services Australia.

- The advice indicated that whole of population telehealth would be cost-neutral.

- The advice noted that further policy advice regarding additional specialist items would be provided at a later date.

2.14 Health provided advice to the Minister regarding additional specialist items in April and May 2020, in three tranches. The Minister approved the addition of specialist items as advised.

- The first tranche identified 11 priority face-to-face specialist services that would be offered also as telehealth services. It contained little discussion of the risks and benefits of the dual offering of the services via face-to-face and telehealth methods.

- The second tranche advised that an internal triaging process including clinical advice had been followed to evaluate all suggestions obtained through stakeholder consultation for mirroring existing face-to-face services as telehealth services. The advice proposed 28 face-to-face specialist services to be offered also as telehealth services. Again, it did not discuss risks or benefits of offering these dual services.

- The third tranche provided advice on the benefits and drawbacks of each of the remaining suggestions from stakeholders, including those not supported by Health, and from these suggestions proposed five additional face-to-face services that could be offered also via telehealth.

Maintenance of temporary telehealth

2.15 In July 2020 Health adopted an approach to modelling telehealth costs that did not assume cost-neutrality and was based on observed trends during the early pandemic. The costs of subsequent material changes to telehealth policy were advised to government based on Health modelling.

2.16 Australian Government budget policy requires entities to complete a Risk Potential Assessment Tool for new policy proposals with an estimated financial implication of $30 million or more.21 Between September 2020 and April 2021 Health presented three new policy proposals to extend temporary telehealth settings. Each proposal had an estimated financial implication exceeding $30 million. Health did not prepare Risk Potential Assessment Tools for these three proposals.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.17 Health should ensure that a Risk Potential Assessment Tool is completed for all new policy proposals with a financial impact of $30 million, in accordance with Australian Government budget policy, and could promote the use of the Risk Potential Assessment Tool as a better practice for new policy proposals of less than $30 million. |

2.18 New policy proposals to change the MBS may require the completion of a Regulation Impact Statement (RIS) in accordance with the Australian Government Regulatory Impact Analysis Framework.22 RISs must include the policy options being considered, the likely net benefit of each option, an implementation plan for the recommended option and an evaluation plan. The Office of Best Practice Regulation, which administers the framework, describes regulatory impact analysis as helping policymakers develop the evidence base for well-informed decision-making.23

2.19 Health was not required to prepare a RIS for the introduction of temporary telehealth services and extensions of these services in September 2020 and February 2021 due to an exemption granted by the Prime Minister on 31 March 2020 for urgent and unforeseen Australian Government measures made in response to COVID-19.24

2.20 For the third extension of temporary telehealth in May 2021, Health prepared a draft RIS that also included analysis of voluntary patient registration proposals.25 The RIS proposed two policy options. The first option considered a reversion to pre-COVID-19 MBS settings by permitting the temporary telehealth items to lapse and abandoning work on voluntary patient registration. The second option, nominated as the preferred option, proposed a further extension to temporary telehealth, the introduction of new temporary telehealth services, a redesign of telephone telehealth services for general practitioners (GPs), the introduction of new compliance arrangements, and continued development of voluntary patient registration. Under the heading of a third option, Health advised ‘at this stage, there is no other viable option’.

2.21 The draft RIS was informally reviewed by the Office of Best Practice Regulation, which provided feedback that the analysis of policy options ‘pre-empted’ the preferred solution because the definition of the problem and the description of the options alerted the reader to which of the options was preferred before the analysis of the impacts was stated. The Office of Best Practice Regulation review indicated that the draft RIS ‘would need significant further development’ to be able to support a final decision by the Australian Government regarding permanent telehealth and voluntary patient registration (see paragraph 2.24). The draft RIS was the form of regulatory impact analysis that supported a final decision on the third extension of temporary telehealth in May 2021.

Permanent telehealth

2.22 Between 2 June 2020 and 6 August 2021 Health officials provided seven ‘deep dive’ briefs to the Minister to discuss the benefits, risks and costs of permanent telehealth policy options. The briefs covered pre-pandemic utilisation of telehealth; lessons from temporary telehealth; potential policy options for GP and specialist post-pandemic telehealth including compliance arrangements; extensions of temporary telehealth arrangements; and the potential timing of new measures.

2.23 Advice on permanent telehealth was provided to the Australian Government in December 2021. The advice identified that permanent telehealth offered economic and productivity benefits, improved patient access, and was able to provide sufficient quality of care when offered in conjunction with face-to-face services. The advice discussed the evidence base that supported Health’s preference for videoconferencing rather than phone telehealth and noted that some stakeholders had raised concerns that this preference could affect equality of access for patients.

2.24 The advice included a RIS which evaluated five policy options (Table 2.1). The RIS recommended option five.

Table 2.1: Policy options for permanent telehealth presented in a December 2021 Regulation Impact Statement

|

Options |

Summary of the proposed policy |

|

|

1 |

Status quo — do nothing |

Reversion to pre-pandemic settings after temporary telehealth items lapse on 31 December 2021 |

|

2 |

Extend current COVID telehealth items to allow for a transition to living with COVID, without MyGPa |

Extend temporary settings to a nominated date in the future |

|

3 |

Retain telehealth services, without MyGP |

Telehealth items would be placed on the MBS in the same manner as other ongoing items |

|

4 |

MyGP, no telehealth |

Implement MyGP separately to telehealth — telehealth items would revert to pre-COVID-19 settings after temporary items lapse on 31 December 2021 |

|

5 |

MyGP and telehealth |

Telehealth items would be placed on the MBS in the same manner as other ongoing items, and subsequently restricted to patients registered under MyGP |

Note a: MyGP is the brand name for voluntary patient registration. Voluntary patient registration is a system whereby patients register with their usual general practice and nominate their usual doctor.

Source: Health records.

2.25 The recommended option was costed using a detailed methodology that compared a hypothetical scenario in which COVID-19 had not happened with actual telehealth data for the same period, to estimate the extent to which telehealth services substituted for face-to-face services during the pandemic. This approach aimed to control for other factors potentially influencing MBS costs. The analysis supporting the RIS was assessed as ‘adequate’ by the Office of Best Practice Regulation, the second lowest rating on a four-tier rating scale.26

2.26 Although the RIS examined the proposal for MyGP and permanent telehealth collectively, two separate Risk Potential Assessment Tools (RPATs) were prepared. The first RPAT examined the risks associated with MyGP, which included consideration of the impact of restricting GP telehealth to patients registered under MyGP. A second RPAT examined the risks of permanent telehealth for GPs, specialists, nursing, midwifery and allied health providers. The RPATs assigned a low risk rating to both MyGP and permanent telehealth.

Did policy advice consider stakeholder opinion and previous experience?

Health consulted with and incorporated the opinions of peak bodies into policy advice for temporary and permanent telehealth. Consultation on temporary telehealth occurred within short timeframes. For general practice and allied health permanent telehealth, consultation practices were largely aligned with a stakeholder engagement plan. For specialist permanent telehealth, there was no finalised stakeholder engagement plan, however consultations occurred, and views were reflected in policy advice. State and territory governments were involved in high level discussions but were largely not consulted on the details of changes to MBS items. A key Indigenous peak body was not involved in stakeholder meetings where the specifics of telehealth policy settings were discussed. Health used pre-pandemic experience with telehealth, and experience arising from the pandemic, to inform policy proposals.

Consultation on temporary telehealth

2.27 The introduction of temporary telehealth services in response to COVID-19 during March 2020 was not subject to a formal or structured consultation process, reflecting the short period in which rapid changes were required. However, during the 28-day period in which the fundamental policy options for temporary telehealth were developed and implemented, Health discussed telehealth proposals with primary health care stakeholders at ad hoc and standing meetings used to share broader information on the COVID-19 pandemic response.

- On 6 March 2020 Health hosted a pandemic preparedness forum (at which it discussed telehealth as a possible response measure) with representatives from peak bodies in general practice, allied health, practice management, nursing, rural and Indigenous health, pharmacy and pathology; primary health networks; state and territory governments; and National Disability Insurance Scheme representatives.

- Between 18 March and 16 December 2020 Health hosted 44 meetings of the GP Peak Body COVID-19 Response Teleconference. Participants included the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACRRM), Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP), Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP), Rural Doctors Association of Australia (RDAA), Australian Medical Association (AMA), National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), Council of Presidents of Medical Colleges, and Medical Indemnity Industry Association of Australia. Telehealth was discussed at 24 of these meetings.

- Between 25 March and 16 December 2020 Health hosted 35 meetings of a broader ‘Primary Health Care COVID-19 Response Teleconference’. Participants included organisations representing allied health and specialist professions, nursing, practice managers, universities, and rural and regional health services. Telehealth was discussed at 21 of these meetings.

- Between 31 March and 9 April 2020 Health approached 148 specialist and allied health peak bodies and interest groups, requesting that respondents complete a feedback form to suggest existing face-to-face specialist services that would be suitable to also be offered as telehealth services. The ANAO observed that Health provided tailored feedback to at least six respondents on whether their suggestions were progressed or not supported.27

2.28 Between 2020 and 2022 Health provided policy advice regarding further adjustments to temporary settings that originated from peak body feedback and opinion received by the department or Minister.

2.29 In accordance with a direction from the Australian Government, Health sought advice from the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) on 10 August 2020 about extending temporary telehealth past September 2020 and briefed the Australian Government on this advice. The Australian Government directed that consideration of further extensions of telehealth and other pandemic response measures should also be informed by AHPPC advice. In December 2020 Health asked AHPPC to endorse advice that, while not specifically referencing telehealth, indicated that emergency response measures would be required until 31 December 2021. The AHPPC endorsed the advice on 23 December 2020. Advice on subsequent extensions of temporary telehealth settings in 2021 noted that the extensions were in accordance with AHPPC advice.

Consultation on permanent telehealth

2.30 From June 2020 onwards, responsibility for stakeholder consultation in relation to telehealth was divided between two divisions within Health. One division examined GP and allied health provider telehealth, and the second division examined telehealth for specialists.

Consultation on GP and allied health provider telehealth

2.31 Health consulted on GP and allied health provider telehealth under a stakeholder engagement strategy developed for the Primary Health Care 10 Year Plan (the 10 Year Plan).28 The strategy listed six mechanisms for consultation, of which four materially contributed to the formulation of policy for permanent telehealth: the Primary Health Reform Steering Group29, a series of roundtable discussions on specific issues in the primary health care system, and two rounds of formal public consultation on the draft 10 Year Plan.

- Primary Health Reform Steering Group — Meeting records show that telehealth was discussed substantively at six out of 20 meetings between 20 March and 11 December 2020.

- Roundtable discussions — Between 16 July and 11 December 2020 Health convened 12 roundtable discussions that included discussion on telehealth.

- Public consultation — Health published a Primary Health Reform Steering Group discussion paper and draft recommendations for the 10 Year Plan on its Consultation Hub30 between 15 June and 27 July 2021. A report that summarised the 201 submissions (including six relating to telehealth) was considered by the Steering Group on 13 August 2021. Health published the draft 10 Year Plan on its Consultation Hub between 13 October to 9 November 2021. Health received 185 submissions (including 142 referring to telehealth) from peak bodies, health service delivery organisations, businesses, not-for-profit organisations, primary health networks, individuals, state and territory governments, universities and research institutes and other respondents.

2.32 The remaining two mechanisms listed in the stakeholder engagement strategy were: convening meetings of a Primary Health Reform Consultation Group (which had a broader membership than the Steering Group), and targeted consultation meetings with states and territories. Neither of these mechanisms was used after June 2020 and they did not inform permanent telehealth policy.

2.33 In July 2020 Health commenced negotiations with four peak bodies (RACGP, AMA, ACRRM and RDAA) to request suggestions for policy settings and seek the support of these bodies for the Australian Government’s primary health care reform package. Between November 2020 and March 2021 Health and the four peak bodies met six times to discuss GP telehealth. At a meeting on 3 March 2021, Health presented a brief that summarised a proposal for permanent GP telehealth based on input from the peak bodies and the Primary Health Reform Steering Group Co-Chairs. Health shared preliminary costings of the proposed option with the four peak bodies. Policy advice to the Australian Government for the 2021–22 Budget noted the policy parameters were subject to ongoing discussion with RACGP, ACRRM, RDAA and AMA.

Consultation on specialist telehealth

2.34 In July 2020 Health prepared a brief for the Minister summarising unsolicited feedback from Australian Association of Consultant Physicians (AACP), Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP), and RACP on extending specialist telehealth.

2.35 In anticipation that temporary specialist telehealth would continue past 30 September 2020, Health commenced drafting a stakeholder engagement and communication strategy to inform the development of policy options for permanent specialist telehealth before the 2021–22 Budget. The draft strategy was not finalised.

2.36 The draft strategy identified four peak bodies (AMA, RACP, RANZCP and the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS)) as priority stakeholders. Between October 2020 and September 2021 Health held meetings with and sought feedback from the four peak bodies identified in the strategy and three other peak bodies, including the AACP (which had requested to be involved). Policy advice provided to the Australian Government for the 2021–22 Budget and in November 2021 conveyed the views of the AMA, RACP, RANZCP and RACS on the proposed policy options.

Reported difficulties with consultation

2.37 The ANAO received 31 submissions to the audit. Eight submissions from peak bodies representing providers and one state government provided positive feedback on the ability to discuss telehealth policy matters with Health between 2020 and 2022. Three submissions from organisations other than peak bodies (a state government, a patient advocacy group, and a private company) stated that it was difficult to contribute to the formulation of telehealth policy.

2.38 In a meeting with the ANAO, representatives from three states and territories advised that in their view, while the Australian Government consults with providers on changes to the MBS it largely does not consult with states and territories. The representatives noted the following.

- While state and territory health departments are represented at a high level in fora such as AHPPC and its sub-committees, these committees do not generally discuss the details of proposed changes to the MBS.

- The details of MBS telehealth items affect state and territory health departments. Where state and territory health providers offer virtual care services (health services that are equivalent or analogous to MBS telehealth) to a hospital outpatient, the practicalities of dealing with or choosing between two differently designed systems may impact on overall patient experience and the course of clinical treatment chosen.

- Some state and territory health departments are progressing virtual care strategies that are trying to promote cultural change in Medicare-eligible populations regarding how health services are accessed. States and territories have relevant experience to share with the Australian Government including the evaluation of virtual care initiatives.

2.39 The ANAO asked senior Health officials whether state and territories are a stakeholder for changes to the MBS. Health officials advised the following.

- Consultation and coordination via AHPPC and National Cabinet was substantial throughout the pandemic and involved senior decision-makers from each jurisdiction.

- State and territory authorities were not worried about the Australian Government’s regulatory approach to telehealth during the pandemic, other than requiring assurance that continuity of service would be maintained.

- Health would not normally consult with states and territories on the detail of MBS changes as the bulk of MBS funding is directed towards private providers and the amount of MBS funding provided under an intergovernmental agreement that permits state and territory health workers in remote locations to submit MBS claims is considered negligible. Peak bodies are the experts on the detail of MBS changes.

- Two states (New South Wales and Tasmania) were represented on the Primary Health Reform Steering Group (discussed in paragraph 2.31).

- The nature of consultation with state and territory health departments regarding changes to the MBS should be considered in the context of the consultation that is meant to occur under the National Health Reform Agreement.31

2.40 A submission to the audit from the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO)32 stated that the 1 July 2021 removal of telephone MBS items was made without consultation with the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Sector. As noted in paragraph 2.27, NACCHO met regularly with Health in the GP Peak Body COVID-19 Response Teleconference meetings and had representation on the Primary Health Reform Steering Group, however it was not represented in the meetings described in paragraph 2.33, where the specifics of telehealth policy settings were negotiated. The Minister received correspondence from NACCHO that noted the Australian Government’s commitment under the National Agreement on Closing the Gap to provide Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with a greater say in policy making that affects them. Internal Health correspondence also noted that the interests of NACCHO were significant and different to those of other peak bodies.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.41 When co-designing policy settings, Health could assess whether the parties invited to co-design collectively represent all relevant interests, and if not consider whether additional targeted consultation is required to complement the co-design process. |

Incorporation of lessons from past experience

2.42 In December 2019 the MBS Review Taskforce33 convened a working group to examine telehealth as a concept, develop a set of MBS ‘Telehealth Principles’ to guide future telehealth policy, and provide recommendations to the Australian Government through the MBS Review Taskforce regarding telehealth. The MBS Review Taskforce endorsed the final report of the working group on 30 June 2020.34 The findings of the MBS Review Taskforce relating to telehealth, which included an emphasis on video rather than telephone as a telehealth medium, were referenced by Health in advice to the Australian Government in April 2021 and November 2021.

2.43 In June 2020 the Australian Government directed that proposals for permanent telehealth items should be assessed by and receive a recommendation from either the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC)35 or the MBS Review Taskforce. Health did not implement this direction.

- Health determined that MSAC would be unlikely to be able to provide advice of the nature requested before August 2021, which did not meet Health’s intended timeframe to provide advice in April 2021 to the Australian Government for the 2021–22 Budget.

- The MBS Review Taskforce held its final meeting to complete its review of existing MBS items on 30 June 2020, and in May 2020 had already commenced drafting its final report, which was submitted to the Australian Government on 14 December 2020.

2.44 In November 2020 Health commissioned a Bond University research institute36 to provide a systematic literature review of the efficacy and value of telehealth services within primary care. The final report of the literature review was presented to the Australian Government and considered at a meeting of the Primary Health Reform Steering Group in April 2021.

2.45 Policy advice presented to the Australian Government in support of extensions of telehealth or proposals for permanent telehealth progressively contained greater analysis of telehealth billing trends during the pandemic.

Was an appropriate implementation plan developed?

In introducing temporary telehealth in response to COVID-19, Health followed existing processes associated with section 3C determinations under the Health Insurance Act 1973 without a documented implementation plan. Implementation stages and milestones for both temporary and permanent telehealth were described at a high level in advice to government. The high-level advice to government did not set out how the changes would be evaluated. Health aligned planning for permanent telehealth with other plans for primary health care reform. The implementation plan for permanent telehealth has been subject to multiple changes, including in response to the ongoing pandemic.

Implementation plan for temporary telehealth

2.46 In the period of rapid implementation of the initial temporary telehealth expansion, there was no documented implementation strategy or plan that outlined in advance deliverables and milestones. Consistent with the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus, which states that ‘it will be important to commence measures as quickly as possible’ and before there is likely to be a good understanding of the disease, Health prioritised rapid implementation of telehealth changes over documented planning in March 2020.

2.47 Initial policy advice to government on 10 March 2020 sought only high-level approval to implement changes to the MBS to enable telehealth to be accessible for nominated classes of patients, with further details to be worked out with the Department of Finance. The advice did not identify specific health services as deliverables or nominate milestones for implementing these as MBS items. The advice did not specify the mechanism by which the changes would be made. The advice nominated an expiry date for the new services and the conditions under which an extension might be recommended to government, but did not otherwise discuss how the changes might be evaluated.

2.48 The Minister may add a health service to the MBS by making a 3C determination. The power to make a 3C determination has been delegated to specified senior executives within Health. 3C determinations were used as the mechanism to implement the expansion of telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.49 Health advised the ANAO that making a 3C determination is an established process that is suited to implementing changes to the MBS that are temporary or urgent. Although only partly documented, the ANAO found that the roles and responsibilities, and steps in the process of implementing a 3C determination, were well understood.

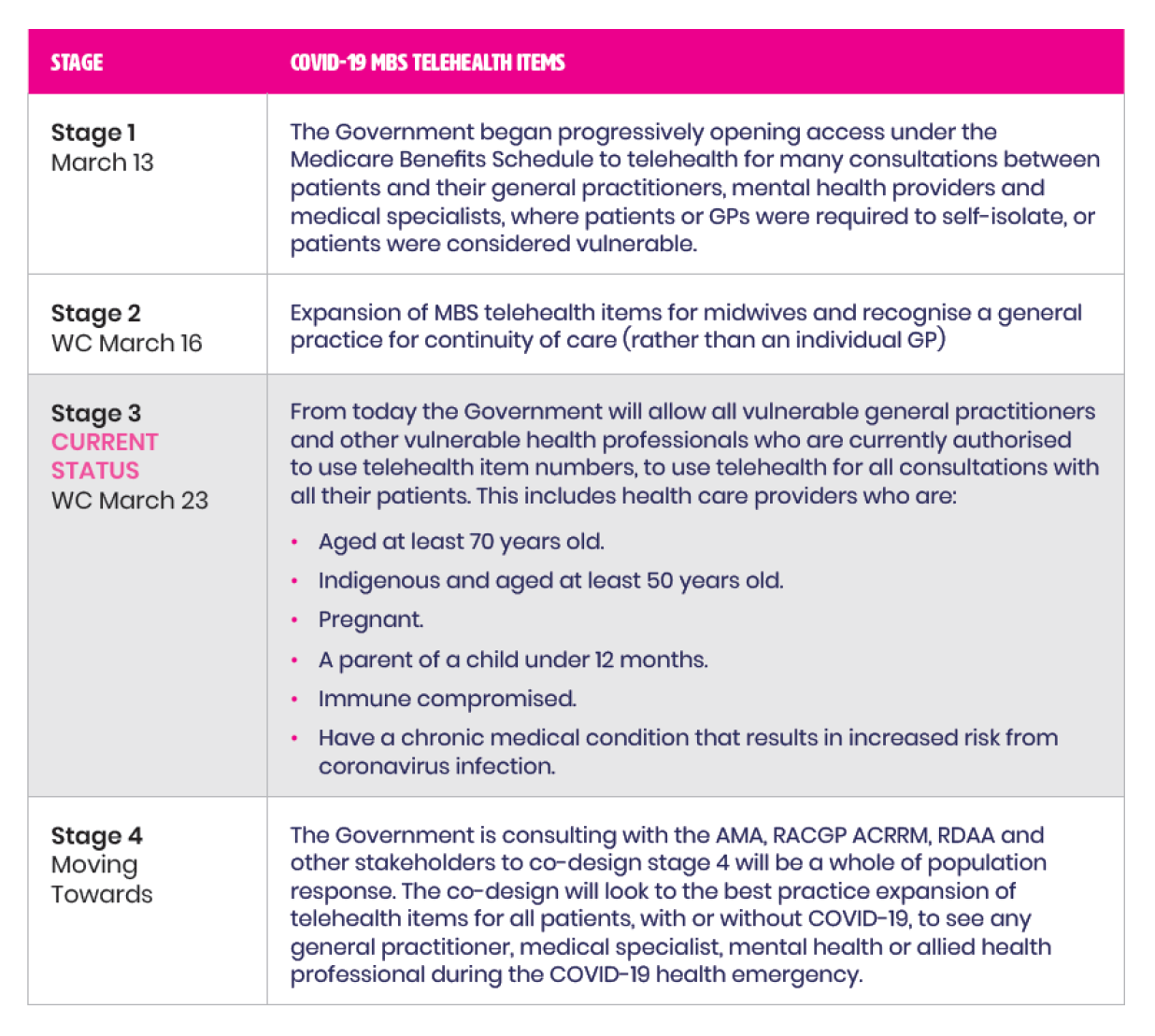

2.50 The further expansion of telehealth between March and July 2020 was implemented incrementally, with Health adopting the terminology of ‘staged implementation’ to describe changes made in this period. On 23 March 2020 Health issued a fact sheet that categorised actions taken since 13 March 2020 into three stages, and stated that a fourth stage would be conducted (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Telehealth expansion implementation stages 1–4 outlined in Health fact sheet, 23 March 2020

Note: On 30 March 2020 Health provided further policy advice to the government regarding Stage 4. Health advised that approximately 70 new telehealth items would be implemented via a 3C determination, but due to operational limitations might not be implemented in one tranche. Health advised that it had already solicited stakeholder advice on implementation priorities in the event progressive implementation of the items would be necessary.

Source: Health records.

2.51 Two further implementation stages are outlined in Health documentation.

- Stage 5 — Policy advice on 30 March 2020 foreshadowed that further advice would be provided regarding a future Stage 5, which would consider a range of specialist items for expansion. On 3 April 2020 Health requested the Minister approve a ‘stepped approach to implement stage 5 of the Government’s response to COVID-19’, and subsequently progressed this stage in three tranches.

- Stage 7 — On 10 July 2020 the Minister announced the reintroduction of the requirement for telehealth patients to have an existing clinical relationship with the provider, and referred to this change as Stage 7 of the telehealth reforms.

2.52 ANAO identified inconsistent usage of the term ‘Stage 6’ in departmental records to refer to the second and third tranches of Stage 5. The ANAO also identified records that referred to the first tranche of Stage 5 changes as part of Stage 4. These inconsistencies illustrate that Health did not maintain a reliable reference that tracked what implementation activities occurred in each stage and how these stages related to one another. Health advised the ANAO that the discrepancies are a reflection of the operational pressures of the COVID-19 response at that time.

Implementation plan for transition to permanent telehealth

2.53 In April 2021 Health provided advice to the Australian Government that set out its implementation plan at a high level for a transition from temporary to permanent telehealth settings. The plan clearly outlined deliverables and timeframes for delivery up to 31 December 2021, and proposed that permanent telehealth items would commence on 1 January 2022 with the exact settings to be determined closer to that date. Health noted that the permanent telehealth implementation plan and 10 Year Plan were interdependent and the permanent telehealth implementation plan addressed the interaction between the two plans.

2.54 The permanent telehealth implementation plan discussed including GP telehealth items in the ‘80/20 rule’.37 At the time the advice was provided to the Australian Government, the proposed implementation date for this deliverable could not be met due to resourcing constraints in business areas within Health responsible for preparing the necessary legislative changes.

2.55 The permanent telehealth implementation plan was updated in December 2021 advice to government. The updated plan clearly outlined deliverables and timeframes in 2022 and 2023 (including the introduction of a new ‘30/20 rule’ from 1 January 2022)38 and addressed the interaction between permanent telehealth and the implementation of voluntary patient registration.

2.56 Neither the April 2021 or December 2021 advice contained detailed plans for performance monitoring or evaluation for permanent telehealth.39

2.57 Shortly after the Minister announced the Australian Government’s plan to implement permanent telehealth on 13 December 2021, there was an outbreak of the Omicron variant of COVID-19. Implementation activities deviated from the permanent telehealth implementation plan in response to the outbreak. Deviations included:

- on 17 January 2022, reinstating temporary telehealth items that had expired on 31 December 2021, with a new expiry date of 30 June 2022; and

- on 20 January 2022, removing telehealth items from the 80/20 rule and repealing the 30/20 rule.40

2.58 Submissions to the audit relating to the implementation approach adopted by Health are summarised in Table 2.2. A consistent theme was that the number, frequency and speed of changes to telehealth arrangements was problematic for some stakeholders.

Table 2.2: Feedback on the implementation approach in submissions to the audit

|

Nature of feedback |

Number (%) of submissions providing feedback on the implementation approach |

|

Stated that changes to telehealth settings were made abruptly or without sufficient notice |

9 (29%) |

|

Accepted that rapid and flexible implementation was necessary to respond to the pandemic |

8 (25%) |

|

Stated the frequency of changes to telehealth settings created confusion |

6 (19%) |

|

Expressed appreciation for the personal implementation efforts of Health officials |

4 (13%) |

|

Stated the expiry, extension and/or reinstatement of temporary items over short timeframes prevented long-term decision making by businessesa |

3 (10%) |

|

Stated the frequency of changes to telehealth settings increased costs to businessesb |

2 (6%) |

Note a: For example, investing in hardware, software, or staff training to provide telehealth via videoconference.

Note b: For example, by necessitating updates to billing systems, education and training of staff, and communications to patients on service options and costs.

Source: ANAO analysis of 31 submissions to the audit.

3. Implementation arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the telehealth expansion was supported by sound implementation arrangements.

Conclusion

The Department of Health and Aged Care implemented significant changes to the Medicare Benefits Schedule and in doing so provided largely appropriate support to delivery partners. However, the telehealth expansion was only partly supported by sound implementation arrangements. Although the Department conducted risk-based post-payment compliance activities, the governance arrangements for the implementation of temporary telehealth involved inadequate assessment of the implementation and integrity risks.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations to the Department of Health and Aged Care. The first was to strengthen its systems of control for the implementation of material changes to the Medical Benefits Schedule, to embed elements of governance that are currently unaddressed. The second recommendation was that implementation, integrity and other risks to proposed material changes to the Medicare Benefits Schedule are subject to a structured and documented risk assessment.

The ANAO also suggested that Health could work with Services Australia to improve practices for the consideration, approval and record keeping of External Costing Requests.

3.1 The delivery of Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) changes relating to telehealth needed fit-for-purpose governance arrangements; collaboration with and support to delivery partners; a structured approach to managing risks to successful implementation; and an assessment of how integrity risks associated with new telehealth items could be mitigated.41

Were governance arrangements fit-for-purpose?

Standard procedures used by Health to implement telehealth changes to the MBS did not require key implementation decisions and plans to be documented, implementation and integrity risks to be managed, or performance monitoring and evaluation plans to be considered. As a result, Health’s governance arrangements for the expansion of telehealth were not fit-for-purpose. Health’s project management framework provides suitable governance arrangements, but it was not used.

Senior management oversight

3.2 Accountability for the MBS rests with the Secretary of the Department of Health and Aged Care (Health) and the Services Australia Chief Executive Officer (who is also the Chief Executive of Medicare).

3.3 The Secretary of Health is assisted by two standing advisory committees (the Program Assurance Committee and the Digital, Data and Implementation Board) with mandates that include providing oversight of new measures affecting the MBS. The committees report to the Executive Board. Neither committee provided material oversight of the expansion of telehealth in 2020 and 2021.