Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Ethanol Production Grants Program

The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Industry’s administration of the Ethanol Production Grants Program, including relevant advice on policy development.

Summary

Introduction

1. Ethanol or ethyl alcohol (molecular formula C2H5OH) is a colourless liquid and is the principal form (and intoxicating agent) of alcohol found in alcoholic beverages. It can also be used as a solvent, an antiseptic and as a fuel. When used as a fuel, it can either be used ‘neat’ (known as E100) or blended with petrol. In Australia, ethanol is typically blended with petrol at a concentration of 10 per cent ethanol and 90 per cent petrol—known as E10. Most modern vehicles available in Australia can operate successfully on E10; at concentrations higher than this, engines may require modification.

2. Since 1980, successive Australian governments have introduced initiatives aimed at assisting the development of an Australian ethanol industry1, including the Ethanol Bounty which operated from 1994—1996 and the Ethanol Production Grants Program from 2002 to the present. In addition to industry development, other indirect outcomes—such as regional development, environmental and health benefits—were also advanced in support of domestically-produced ethanol as a fuel.

The Ethanol Production Grants Program

3. In September 2002, the then Prime Minister, the Hon. John Howard MP, announced that as part of a strategy to encourage the use of biofuels in transport, the Australian Government would abolish the exemption from fuel excise for ethanol and impose an excise at the same rate as for petrol (38.143 cents per litre). At the same time, the Government introduced a ‘production subsidy’ to be paid to producers of ethanol in Australia (but not to importers of ethanol). For existing Australian producers of ethanol, the effect of this government decision was that while they would be required to pay the excise to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), they would then be reimbursed in full through the Ethanol Production Grants Program (EPGP).

4. When the EPGP was first established, program documentation did not include explicit objectives or outcomes, but referred to the terms of the Prime Minister’s media release when announcing the program. A specific Program objective and outcomes were introduced in July 2012 in the following terms:

Program objective

The objective of the Program is to support production and deployment of ethanol as a sustainable transport fuel in Australia.

The Program will provide fuel excise reimbursement of 38.143 cents per litre for ethanol produced and supplied for transport use in Australia from locally derived feedstocks.

Program outcome

The intended outcome of the Program is to:

(a) Encourage the use of environmentally sustainable fuel ethanol as an alternative transport fuel in Australia;

(b) Increase the capacity of the ethanol industry to supply the transport fuel market; and

(c) Improve the long term viability of the ethanol industry in Australia.

5. The EPGP is a demand-driven grants program. Eligible producers that have a funding agreement with the Commonwealth are reimbursed for excise paid to the ATO, usually on a weekly basis. To be eligible for grants under the EPGP, applicants must:

- be an Australian entity incorporated under the Corporations Act 2001;

- produce and supply ‘eligible ethanol’2; and

- not have been named as an entity that has not complied with the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Act 1999.3

6. Applications for funding can be submitted for assessment at any time. Under all EPGP program guidelines, approved by the relevant Minister at certain times, authority for making decisions on program eligibility and funding has been delegated to departmental officials. The EPGP program guidelines provide that the program must be administered in accordance with the Australian Government’s financial management and accountability framework, including the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines.4

7. When first introduced, the EPGP was administered by the then Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources, and later by the then Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (RET). At the time of this audit, the program was administered by the Department of Industry and Science (Industry).5 For simplicity, the title ‘Industry’ will be used throughout this report to refer to the present administering department as well as its predecessors, unless otherwise specified.

8. Since its introduction in 2002, originally as a short-term subsidy ‘while longer term arrangements are considered by the government’, the EPGP has been extended three times: in 2003, 2004 and 2011. Figure S.1 shows a timeline of the EPGP, key decision points for each phase and the administering departments over time.

Figure S.1: EPGP key decision points and administering departments

Source: ANAO.

9. The EPGP has had five participants. When the program commenced, it had two initial participants, increasing to five participants for a single year (2008–09), then declining and remaining at three participants since. Between 2002–03 and 2013–14, one participant (Honan Holdings Pty Ltd) received $543.4 million (70.2 per cent of all program funding).

10. At a number of key program phases, reviews of the EPGP have been commissioned. In February 2014, an assessment by the Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics (BREE)6, a unit within Industry, found that:

- while the annual cost of the program had been significant, regional employment and greenhouse gas abatement benefits had been modest;

- the health benefits that accrue from reduced air pollution are also modest and declining;

- there would appear to be no net benefit for agricultural producers;

- while the program supported an additional lower priced fuel product, the benefits to motorists were less than they should have been; and

- there was no evidence that provision of support for the Australian ethanol industry provided downward pressure on petrol prices.

11. In the 2014–15 Budget, the Government announced the closure of the EPGP, and program payments will cease with effect from 1 July 2015. In parallel, the fuel excise on domestically produced ethanol will be reduced to zero from 1 July 2015 and then increase by 2.5 cents per litre per year for five years from 1 July 2016 until it reaches 12.5 cents per litre.

12. The Australian Government’s total expenditure on the EPGP program since 2002–03, including estimated costs in 201415, is expected to be some $895 million.7

Audit approach

Objective, criteria and scope

13. The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Industry’s administration of the EPGP, including relevant advice on policy development.

14. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high level audit criteria were used:

- the grant application process was accessible and attracted high quality applications;

- the assessment process adopted was consistent, transparent and cost effective;

- advice to the delegate was complete and robust and funding decisions were sound;

- funding distribution is consistent with the program’s objectives and appropriate arrangements are in place to manage successful projects;

- appropriate monitoring and reporting arrangements are in place; and

- relevant government entities provided sound advice to assist with policy development and government decision making.

15. The ANAO examined program administration since 2007–08, given the difficulty in identifying and locating detailed records relating to the program’s early administration. However, the ANAO’s examination of the policy development process and decisions by government covers the period from the EPGP’s establishment in 2002. The ANAO does not have a role in commenting on the merits of government policy.

16. This audit does not involve an assessment of the administration of other (non-EPGP) government initiatives to support the Australian ethanol industry, except to the extent necessary for an understanding of the history of the EPGP.

Methodology

17. In conducting the audit, the ANAO reviewed: documents of the departments of Industry and Science, the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Treasury and Finance, including policy documents, ministerial correspondence, reports, guidelines and operational documents; examined relevant Cabinet submissions, memoranda and decisions; interviewed departmental staff; and examined the grants administration process. The ANAO also invited EPGP recipients (see Table 1.1) to provide representations about their experience as grant recipients and, in particular, Industry’s administration of the program; however, no submissions were received.

Overall conclusion

18. Originally introduced in 2002-03 as a short term (12 month) subsidy payable to eligible domestic ethanol producers, the Ethanol Production Grants Program (EPGP) was extended by successive Australian Governments and will end on 30 June 2015 at a cost to the Commonwealth of some $895 million over the program’s life. The key program objective was to support the production and deployment of ethanol produced from locally derived feedstocks as a sustainable transport fuel in Australia. Intended outcomes were to: improve the long term viability of the ethanol industry in Australia; increase the capacity of the ethanol industry to supply the transport fuel market; and encourage the use of environmentally sustainable fuel ethanol as an alternative transport fuel in Australia. Five program participants have received financial assistance under the EPGP, which is a grants program currently administered by Industry.

19. Overall, Industry’s administration of the EPGP since 2007-08, the period examined in this performance audit, has been generally effective. EPGP program arrangements were generally fit for purpose and largely consistent with the Australian Government’s grants administration framework. The department also implemented a sound arrangement for monitoring grant recipients’ compliance with key program requirements. Had the program continued beyond its planned closure in 2014-15, there would have been opportunities for the department to improve its public performance reporting on achievement against the program’s objectives and outcomes, which is currently limited to reporting on the number of companies that receive payments under the program.

20. The Australian Government’s recent decision to close the EPGP was informed by a consistent body of analysis and advice—provided to successive governments since the program’s earliest days—drawing attention to shortcomings in the overall policy approach and the likelihood that program costs would exceed benefits. Prior to the EPGP’s establishment and at key decision points, the administering department and central co-ordinating agencies8 offered candid advice on value for money, drawing on past Australian and international experience and the findings of two key reviews (in 2008 and 2014) which had concluded that the benefits of the program were modest and had come at a high cost. These assessments of value for money are underlined by the program’s limited success in achieving key objectives and outcomes. After 12 years of operation and some $895 million in government support directed towards improving the long-term viability of the domestic ethanol industry, in 2014 only three domestic producers (up from two in 2002) were operating,9 and an expanded Australian ethanol industry based on market priced feedstock was considered unlikely to be commercially viable in the absence of the EPG rebate.10

21. The ANAO has not made recommendations in this audit, as the EPGP is scheduled to close from 30 June 2015. While there was scope for the administering departments to develop a more effective performance reporting framework as a basis for assessing outcomes, Industry and the central agencies did provide candid advice to government on the modest performance of the program against its objectives, drawing on Australian and international experience and two reviews of the program; with decisions to continue the program until 2014–15 made by successive governments.

Key findings by chapter

Achievement of program objectives (Chapter 2)

22. The Australian Government announced the closure of the Ethanol Production Grants Program (EPGP) in the context of the 2014-15 Budget. While originally established as a one year assistance measure, the EPGP operated for 12 years at a cost of some $895 million, with successive governments extending the program on three occasions.

23. The EPGP is a grants program currently administered by the Department of Industry and Science (Industry). The 2012 program objective was to support the production and deployment of ethanol produced from locally derived feedstocks as a sustainable transport fuel in Australia. The intended program outcomes were to: improve the long term viability of the ethanol industry in Australia; increase the capacity of the ethanol industry to supply the transport fuel market; and encourage the use of environmentally sustainable fuel ethanol as an alternative transport fuel in Australia.

24. At the outset of the program and at key phases in the program’s life, the administering department and central coordinating agencies consistently highlighted shortcomings in the overall policy approach and drew attention to the EPGP’s limited success in achieving its program objectives. In their advice, entities drew on international experience and available Australian evidence, including experience with the earlier Ethanol Bounty Scheme on which the EPGP was largely modelled. A 1996 program evaluation of the Ethanol Bounty Scheme had observed that it would not achieve its objective and should be discontinued.

25. At a number of key program phases, external and internal reviews were commissioned to inform government decisions on the EPGP. In particular, a 2014 report by Industry’s Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics (BREE) provided a concise high level assessment of the program’s costs and benefits11, leading soon after to the Australian Government’s decision to close the program.12

26. In 201314, only three ethanol producers were in receipt of EPGP support. When the program was introduced in 200203, it was suggested that up to a further 15 domestic ethanol plants might be established across Australia. While the program has directly supported a small number of grant recipients13, in some cases for an extended period14, the program has had limited success in achieving the program outcome of improving the long-term viability of Australia’s domestic ethanol industry. In 2014, the BREE considered that an expanded Australian ethanol industry based on market priced feedstock was considered unlikely to be commercially viable in the absence of the EPG rebate.15 The BREE further concluded that realisation of expected indirect benefits—including regional development, environmental and health benefits—has been modest at best, and/or at a much higher cost than could be achieved using more direct forms of government support.

Administration of the EPGP (Chapter 3)

27. In September 2002, the then Prime Minister, the Hon. John Howard MP, announced publicly that the EPGP would commence within a week, providing the administering department16 with very limited opportunity to plan for program implementation. The department focussed initially on establishing funding arrangements with existing producers, consistent with the core program parameters set by Ministers. When the program was subsequently extended, the department formalised several of the program’s key administrative supports, such as application forms and program guidelines, placing its grants administration on a sounder footing. The program guidelines examined by the ANAO were clear and generally reflected the requirements of the grants administration framework. While the program guidelines referred to the Prime Minister’s 2002 statement about the program, an explicit program objective and set of program outcomes were only developed in the course of preparing the July 2012 guidelines.

28. The EPGP is a demand-driven grants program which allows for applications to be submitted at any time. Since its establishment, only two formal applications have been submitted to the administering department—in 2006 and 2008—as the three companies initially contacted in 2002 were directly invited to enter into a funding agreement.

29. As part of its assessment process for the 2008 application, the administering department did not document its assessment of the applicant’s claims against all of the program’s mandatory criteria. In particular, the department did not advise the program delegate whether the applicant met or was likely to meet the ‘eligible ethanol’ criterion17—a key consideration in assessing whether the application would represent a ‘proper use’ of Commonwealth resources.18 In this case, as the applicant advised that it had not yet commenced production of ethanol, it would have been appropriate for the delegate to consider approving EPGP funding on a conditional basis, subject to further inquiries in due course regarding the production of ‘eligible ethanol’. In the event, the department adopted a comparable course of action when, 18 months later in March 2010, it conducted a compliance audit of the then grant recipient to satisfy itself that all EPGP payments had been for ‘eligible ethanol’. The department’s approach could usefully have been documented as part of the approval process for the grant, to help the department demonstrate its consideration of ‘proper use’ before payments were made.19

30. The ANAO examined all 20 of the EPGP funding agreements, including variations, executed since 2007-08 and found that the key financial framework approval requirements had been observed in 13 of these agreements. Where required, Regulation 10 approvals had also been obtained.20 However, departmental records could not demonstrate that the relevant expenditure approvals had been prepared for seven of these 20 funding agreements prior to their execution.

31. Departmental processes for accepting, verifying and paying EPGP claims by grant recipients have been assessed by the ANAO as part of its financial assurance audit process over each of the last six years, providing reasonable assurance that payments have been correctly and accurately made and reconciled each quarter with the ATO’s records. In addition, a sound arrangement was established for ongoing monitoring of recipients’ compliance with the key program requirements, including through a program of external and internal compliance reviews.

32. Departmental reporting on the EPGP has been mixed. Reporting requirements set out in participants’ funding agreements facilitated ongoing monitoring of program administration. However, the reporting requirements contained in the funding agreements were not designed to assist the administering department monitor achievements against the program’s intended outcomes and claimed benefits (such as the impact of the program on regional employment).

33. Further, for the first seven years of the program’s operation, there were no program-level key performance indicators (KPIs) established for the purposes of internal or external reporting. In 2009 (with revisions made in 2012) internal KPIs were developed but there was no indication that they were used to report to senior departmental management or the Minister to assist with an assessment of whether the EPGP was achieving its objectives. Until 2014–15, public reporting related to ‘Delivery of the Ethanol Production Grants Program’, a broad activity measure which offered no insight into program performance. A revised KPI was published in Industry’s 2014–15 Portfolio Budget Statements, relating to the number of companies that received payments under the program. This KPI offered some improvement over the previous measure but nonetheless provided a very limited basis for assessing achievement of the program’s objectives and outcomes released in 2012.

34. The Government announced the closure of the EPGP in the 2014-15 Budget, effective from 30 June 2015. Internal advice to the program delegate in May 2014 indicated that the department planned a thorough end of program evaluation, incorporating a final compliance audit, be undertaken in the final quarter of 2014–15.

Summary of entity responses

35. The proposed audit report issued under section 19 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 was provided to Industry. In addition, relevant extracts of the proposed report were provided to the departments of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Treasury and Finance.

36. A summary of Industry’s response to the proposed audit report is below, with the full response at Appendix 1.

The Ethanol Production Grants Program commenced in September 2002 as a measure to further assist the development of an Australian ethanol industry. The Government announced the closure of the Program from 1 July 2015.

The Department notes the ANAO has concluded the department’s administration of the Program has been effective. The report also notes the department’s intent to conduct an end-of-program evaluation, incorporating a final compliance audit of grant recipients.

1. Introduction

This chapter provides background information on the use of ethanol as a transport fuel in Australia and summarises government support for ethanol production in Australia, including the Ethanol Production Grants Program. It also outlines the audit approach including its objective, scope and methodology.

Background

1.1 Ethanol or ethyl alcohol (molecular formula C2H5OH) is a colourless liquid. It is the principal type (and intoxicating agent) of alcohol found in alcoholic beverages. It can also be used as a solvent, an antiseptic and as a fuel.21

1.2 Ethanol’s use as a fuel for internal combustion engines dates back to the early nineteenth century. In 1908, when the Model T Ford was introduced, early models ran on ethanol, with adjustable carburettors allowing them to be run on petrol as an alternative.22

1.3 Ethanol can be used as a fuel for motor vehicles, either ‘neat’ (known as E100) or when blended with petrol. Most modern vehicles available in Australia will operate satisfactorily on a blend of 10 per cent ethanol and 90 per cent petrol (E10). At blends higher than this, engines may need modification or damage may occur.

1.4 In Australia, fuel for use in motor vehicles (especially petrol) has been subject to excise23 since 1929. Between 1929 and 1959, excise on fuel was hypothecated (earmarked) for road funding but in 1959, hypothecation was abolished and the revenue became a source of general revenue..

1.5 Since 1980, successive Australian governments have introduced initiatives in various forms aimed at assisting the development of an Australian ethanol industry.24

Australian Government support for ethanol production

Early government initiatives

Excise exemption

1.6 In February 1980, the then (Fraser) Government abolished the $19.25 per litre excise on ethanol when used as a fuel, to ‘encourage research into the production of ethanol as a fuel in internal combustion engines’.25

Ethanol bounty

1.7 In 1994, the then (Keating) Government introduced a bounty26 ‘on the production of certain fuel ethanol in Australia to assist in the development of a competitive, robust and ecologically sustainable fuel ethanol industry’.27 The bounty scheme provided 18 cents per litre payable to registered companies or persons which produced fuel ethanol for use in Australia’s transport industry. Although $25 million was allocated to the three year scheme, only $3.1 million in total claims had been paid by the end of its second year. In 1996, the then Department of Primary Industries and Energy undertook an evaluation of the bounty, which concluded that:

- evidence concerning the greenhouse gas and pollution impacts of fuel ethanol is ambiguous, and the appropriateness of encouraging its production and use, as implemented until now through the Ethanol Bounty Scheme, is questionable;

- current production and use of fuel ethanol is not cost effective in reducing emissions of greenhouse gas and environmental pollutants; and

- the Ethanol Bounty Scheme has not as yet met the objective of the Act28 and is unlikely to significantly achieve this if continued in the future.

1.8 The evaluation recommended:

In light of the conclusions of the evaluation, the Ethanol Bounty Scheme, in its current form, will not achieve its objective and should be discontinued at the current time.

1.9 The bounty scheme was terminated in August 1996.29

Overview of the Ethanol Production Grants Program (EPGP)

1.10 On 12 September 2002, the then Prime Minister (the Hon. John Howard MP) announced that as part of the Government’s strategy to encourage the use of biofuels in transport, the Government would abolish the previous excise exemption and impose an excise to apply at the same rate as for petrol (38.143 cents per litre). In parallel, the Government also introduced a ‘production subsidy’ at the same rate to be paid to producers of ethanol in Australia (but not to importers of ethanol). For existing Australian ethanol producers at the time, the effect of this decision was that while they would be required to pay excise to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), they would be reimbursed in full by the EPGP payment. The Prime Minister’s announcement stated that the subsidy would be provided for 12 months ‘while longer term arrangements are considered by the government regarding the future of the emerging renewable energy industry’.

1.11 When the EPGP was established, program documentation did not include explicit objectives or outcomes, but referred to the terms of the Prime Minister’s 12 September 2002 media release. A specific program objective and outcomes were introduced in July 2012 in the following terms:

Program objective

The objective of the Program is to support production and deployment of ethanol as a sustainable transport fuel in Australia.

The Program will provide fuel excise reimbursement of 38.143 cents per litre for ethanol produced and supplied for transport use in Australia from locally derived feedstocks.

Program outcome

The intended outcome of the Program is to:

- (a) Encourage the use of environmentally sustainable fuel ethanol as an alternative transport fuel in Australia;

- (b) Increase the capacity of the ethanol industry to supply the transport fuel market; and

- (c) Improve the long term viability of the ethanol industry in Australia.

1.12 In order to be eligible for grants under the EPGP, applicants must:

- be an Australian entity incorporated under the Corporations Act 2001;

- produce and supply ‘eligible ethanol’30; and

- not have been named as an entity that has not complied with the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Act 1999.31

1.13 Once assessed as eligible, recipients are required to enter into a funding agreement with the administering department.32 Since its introduction, the EPGP has been administered by four departments33; most recently the Department of Industry and Science (Industry).

1.14 Ethanol producers make payments of excise to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) on a weekly basis and receive a receipt in the form of an Excise Return Form. They then present this receipt, together with evidence of payment (such as a bank statement) and a claim form to Industry for reimbursement of the same amount—usually on a weekly basis.

Progress to date

1.15 Since its introduction in 2002, the EPGP has been extended three times: in 2003, 2004 and 2011. Total expenditure on the program between 2002–03 and 2014–15 is expected to be some $895 million, comprising $773.1 million in actual payments between 2002–03 and 2013–14, and $122.1 million in estimated expenditure in 2014–15.

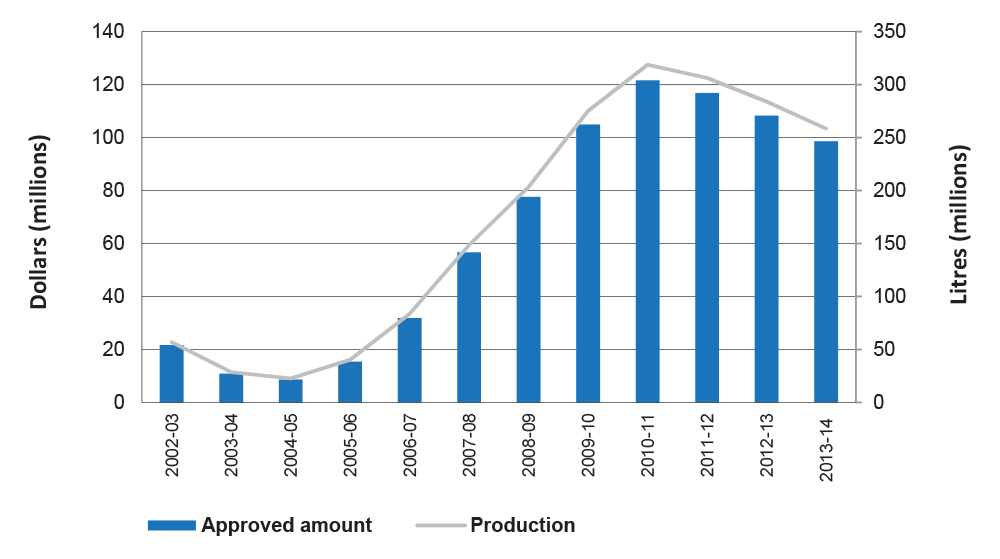

1.16 Figure 1.1 shows the total EPGP payments and production levels from its inception in September 2002 to the end of 2013–14.

Figure 1.1: Ethanol Production Grants Program: grant payments and production, 2002–03 to 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis from Industry data.

1.17 When the EPGP commenced in 2002, two companies were assessed as eligible for EPGP grants. Over the life of the scheme, five companies have received assistance.

1.18 Table 1.1 shows EPGP grant payments to each company for the period 2002–03 to 2013–14.

Table 1.1: EPGP grant recipients and amounts, 2002–03 to 2013–14

|

Year (and number of recipients) |

Dalby Biorefinery Pty Ltd (Qld) |

Honan Holdings Pty Ltd (NSW)1 |

Schumer Pty Ltd (Qld) |

Wilmar Bioethanol Pty Ltd (Vic)2 |

Tarac Pty Ltd (SA) |

Total |

|

2002–03 (2) |

0 |

20 857 998 |

0 |

824 942 |

0 |

21 682 940 |

|

2003–04 (3) |

0 |

10 486 262 |

97 138 |

299 656 |

0 |

10 883 056 |

|

2004–05 (3) |

0 |

7 671 436 |

414 733 |

559 818 |

0 |

8 645 987 |

|

2005–06 (3) |

0 |

11 387 565 |

71 163 |

3 922 281 |

0 |

15 381 009 |

|

2006–07 (4) |

0 |

21 637 968 |

718 |

10 044 841 |

193 856 |

31 877 383 |

|

2007–08 (4) |

0 |

43 937 217 |

2 513 |

12 635 228 |

111 110 |

56 686 068 |

|

2008–09 (5) |

6 478 916 |

57 012 826 |

1 146 |

14 028 932 |

94 006 |

77 615 826 |

|

2009–10 (3) |

23 382 360 |

62 190 636 |

0 |

19 369 757 |

0 |

104 942 753 |

|

2010–11 (3) |

25 093 998 |

83 417 832 |

0 |

13 087 898 |

0 |

121 599 728 |

|

2011–12 (3) |

23 043 155 |

78 285 150 |

0 |

15 511 559 |

0 |

116 839 864 |

|

2012–13 (3) |

23 468 482 |

74 613 764 |

0 |

10 221 481 |

0 |

108 303 727 |

|

2013–14 (3) |

15 932 612 |

71 880 659 |

0 |

10 789 007 |

0 |

98 602 278 |

|

Total |

117 399 523 |

543 379 313 |

587 411 |

111 295 400 |

398 972 |

773 060 619 |

Source: Industry.

Notes:

1. Honan Holdings Pty Ltd is part of the Manildra Group of companies and is sometimes referred to by that name.

2. Also known as Sucrogen and CSR.

1.19 In the 2014–15 Budget, the current Government announced that the EPGP would close effective from 30 June 2015. At that time, the rate of excise will be reduced to zero (from 1 July 2015) and then increased annually in five even stages (by 2.5 cents per litre) for five years until it reaches a ‘final rate’ of 12.5 cents per litre from 1 July 2020.34

1.20 Figure 1.2 shows a timeline of the EPGP, key decision points for each phase and the administering departments over time.

Figure 1.2: EPGP key decision points and administering departments

Source: ANAO.

Other Australian Government ethanol support initiatives

Biofuels Capital Grants Program (BCGP)

1.21 On 25 July 2003, the then Acting Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources announced the Biofuels Capital Grants Scheme (BCGP). Under the BCGP, eligible biofuel producers would receive a subsidy of 16 cents per litre for projects producing a minimum of five million litres of biofuel35, to a maximum of $10 million per project.

Ethanol Distribution Program (EDP)

1.22 On 14 August 2006, the then Prime Minister (The Hon. John Howard MP) announced funding of $17.2 million over three years to assist petrol retailers with the cost of installing new pumps or converting existing ones to encourage the sale of E10 fuel. Up to $10 000 would be paid for direct costs and up to a further $10 000 would be paid, after conversion, if an ethanol sales target was achieved. In October 2008, the then Prime Minister (The Hon. Kevin Rudd MP) approved an additional $6 million for the program, bringing the total funding available under the EDP to $23.2 million.

The Australian Government’s grants administration framework

1.23 Australian Government grant programs involve the provision of financial assistance by the Commonwealth to third parties, and are subject to applicable resource management legislation. Until 30 June 2014, the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) established the overarching framework for the proper use of public money.36

1.24 In support of FMA Act requirements, in July 2009, the Australian Government introduced a policy framework for grants administration.37 The new framework had a particular focus on the establishment of transparent and accountable decision-making processes for the awarding of grants and included new specific requirements set out in the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs) 2009.38 Officials performing grants administration must act in accordance with the CGGs.

1.25 The EPGP is subject to the grants policy framework. The EPGP program guidelines provide that the department must administer the program in accordance with the Australian Government’s financial management and accountability framework, including the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines.39

Audit objective, criteria, methodology and scope

1.26 The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Industry’s administration of the EPGP including relevant advice on policy development.

Audit criteria and scope

1.27 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high level audit criteria were used:

- the grant application process was accessible and attracted high quality applications;

- the assessment process adopted was consistent, transparent and cost effective;

- advice to the delegate was complete and robust and funding decisions were sound;

- funding distribution is consistent with the program’s objectives and appropriate arrangements are in place to manage successful projects;

- appropriate monitoring and reporting arrangements are in place; and

- relevant government entities provided sound advice to assist with policy development and government decision making.

1.28 The ANAO examined program administration since 2007–08, given the difficulty in identifying and locating detailed records relating to the program’s early administration. However, the ANAO’s examination of the policy development process and decisions by government covers the period from the EPGP’s establishment in 2002. The ANAO does not have a role in commenting on the merits of government policy.

1.29 This audit does not involve an assessment of the administration of other (non-EPGP) government initiatives to support the Australian ethanol industry, except to the extent necessary for an understanding of the history of the EPGP.

1.30 There have been a range of entities involved in both the administration and policy aspects of the EPGP. When the EPGP was established in 2002, the then Prime Minister announced that it would be administered by the then Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources (DITR), with the actual delivery of the program carried out by AusIndustry (a division of DITR). Following the November 2007 election and consequent Machinery of Government changes, the newly-created Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (RET) assumed policy responsibility for the EPGP, with AusIndustry continuing to perform the program delivery role. From December 2011, RET assumed both policy and program delivery responsibilities for the EPGP. After the September 2013 election, RET was abolished and its resources and energy functions, including the EPGP, were transferred to the Department of Industry. In December 2014, the Department was renamed the Department of Industry and Science. For simplicity, the title ‘Industry’ will be used throughout this report to refer to the present administering department as well as its predecessors, unless otherwise specified.

Audit methodology

1.31 The ANAO:

- reviewed documents of the departments of Industry and Science, the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Treasury and Finance, including policy documents, ministerial correspondence, reports, guidelines and operational documents;

- examined relevant Cabinet submissions, memoranda and decisions;

- examined the grants administration process; and

- interviewed departmental staff.

1.32 The ANAO also invited EPGP recipients (as shown in Table 1.1) to provide representations about their experience as grant recipients and, in particular, Industry’s administration of the program. However, no submissions were received.

1.33 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $472 000.

Report structure

1.34 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Chapter Overview |

|

2. Program Objectives |

Examines advice provided by several Australian Government entities to government on the Ethanol Production Grants Program (EPGP) and related matters, from its establishment phase in 2002 to its planned closure effective from June 2015, as well as progress towards achievement of the program objectives. |

|

3. Program Administration |

Examines the administration of the Ethanol Production Grants Program with a focus on activity since 2007–08. |

Source: ANAO.

2. Program Objectives

This chapter examines advice provided by several Australian Government entities to government on the Ethanol Production Grants Program (EPGP) and related matters, from its establishment phase in 2002 to its planned closure effective from June 2015, as well as progress towards achievement of the program objectives.

Introduction

2.1 Australian Government entities have a key role in providing advice to government on matters within their areas of responsibility. For the Ethanol Production Grants Program (EPGP), primary responsibility for energy policy and industry development rests with the (now) Department of Industry and Science (Industry).40 However, the program intersected with broader policy concerns—including taxation (in particular fuel excise), regional development, renewable energy and other environmental issues—and the central agencies were also closely involved in advising successive governments on the EPGP’s development and achievement of program objectives since 2002.

2.2 As noted in Chapter 1, the EPGP had a number of phases:

- Phase 1—Establishment (2002-2003);

- Phase 2—First Extension (2003-2008);

- Phase 3—Second Extension (2008-June 2011);

- Phase 4—Third Extension (July 2011-November 2021); and

- Phase 5—Closure (2014 to June 2015).

2.3 In this context, the ANAO examined advice to governments provided by Industry and the central agencies at key decision points in the EPGP’s life, including progress towards achievement of the program objectives.

2.4 Governments may also draw on advice from other parties, such as researchers, experts and stakeholders. In this audit, the ANAO has referenced a number of external expert reports relevant to the EPGP.

Phase 1 – Establishment (2002–2003)

2.5 Ahead of the November 2001 election, the (Howard) Government released an action plan entitled Biofuels for cleaner transport.41 The plan stated that, if reelected, the Coalition would establish an objective that biofuels42 contribute at least 350 million litres to the total fuel supply by 2010, and would provide a capital subsidy of 16 cents per litre for new or expanded domestic ethanol production. The plan also stated that biofuels such as ethanol and biodiesel have a number of advantages over fossil fuel:

- multiple regional benefits, including increased employment, more efficient use of agricultural and forestry residues and an additional income stream to provide a buffer against shifting commodity prices;

- biofuels are renewable, whereas other alternative fuels (such as Compressed Natural Gas (CNG), Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) are not;

- environmental benefits such as improved air quality and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions; and

- increased domestic biofuels production and use will reduce Australia’s reliance on fossil fuels.

2.6 In September 2002, the Government also considered options (and a range of associated measures) to assist the Australian sugar industry which was facing difficulties due to a range of factors including low world sugar prices, adverse seasonal conditions and plant diseases and plagues.

2.7 One option considered by the Government (and subsequently adopted as the EPGP—see paragraph 1.10) was to remove the excise exemption on ethanol, impose excise and customs duty at the same level as for petrol (38.143 cents per litre) and, in parallel, provide a production subsidy of the same amount for existing or new producers of ethanol in Australia (but not for importers of ethanol). The effect of this measure would be to provide domestic producers of ethanol with a 38.143 cents per litre cost advantage over importers of ethanol and other transport fuels.

2.8 In responding to this option (and other proposals) Treasury, Finance and Industry identified a range of concerns, including:

- that assistance to ethanol producers would not assist sugar producers because the (sugar) industry’s difficulties were fundamentally due to low world sugar prices which would not be affected by such assistance;

- that there were already lower cost feedstocks43 than sugar, such as wheat starch and sorghum;

- that ethanol was an inferior product to petrol, having only 60 per cent of the energy content of petrol, had potential operability issues in engines and had significantly higher production costs;

- that the proposed measure offered no quantifiable environmental benefits, could impose significant costs on other Australian industries and would potentially result in significant costs to the Budget; and

- experience to date both internationally and in Australia44 suggested that ethanol as a transport fuel was not commercially viable unless supported by government assistance.

2.9 On 12 September 2002, Prime Minister Howard announced the establishment of (what became known as) the EPGP as a ‘shortterm production subsidy’45—for 12 months. While the announcement did not directly reference this initiative as an assistance measure for the sugar industry, it added ‘the subsidy will provide a targeted means of maintaining the use of biofuels in transport in Australia, while longer term arrangements are considered by the government regarding the future of the emerging renewable industry’. The media release also stated that the subsidy scheme (EPGP) and the excise and customs changes would take effect from midnight on Tuesday 17 September 2002.

2.10 Shortly after the Prime Minister’s announcement, a number of articles in the media46 reported that at the time the subsidy was introduced, a company named Trafigura Fuels had a shipment of ethanol from Brazil on its way to Australia. There was also commentary in the media in 2002 and 200347 about the fact that one of the EPGP recipients—Honan Holdings Pty Ltd (part of the Manildra Group of companies and then the largest Australian producer of ethanol)—had made significant donations to the major political parties.48

Phase 2 - First extension

2.11 In the 2003–04 Budget, the (Howard) Government decided49 to extend the existing EPGP arrangements until 30 June 2008, and then over the following five years the EPGP would be reduced in five yearly instalments until July 2012 to ‘establish an environment where ethanol producers can invest in confidence knowing the arrangements that will apply to their industry for the next nine years’.50 By gradually reducing the EPGP while in parallel introducing the excise in five even annual steps, the Government intended to establish a ‘transition path’ whereby over time the ethanol industry would move from a position of paying no excise (because the EPGP of 38.143 cents per litre was the same amount as the excise, thus producing an effective excise rate of 0 cents per litre) to paying excise (at a rate then yet to be determined).

2.12 During 2003, the Government considered a range of other proposals to support the ethanol industry, including mandating the use of E1051 in Commonwealth vehicles as well as in Australia’s general vehicle fuel supply (as a smaller percentage of fuel content). At this time, it was suggested that while there were only two domestic ethanol producers operating, up to a further 15 ethanol and another 16 biodiesel plants or expansions might be established across Australia.

2.13 Central agencies identified a range of issues relating to the proposal to mandate use of E10 in the Commonwealth vehicle fleet, including: costs; potential for market distortion; and whether a mandated approach would provide existing suppliers with disproportionate market power.

2.14 In mid-2003, a downturn in consumer demand for ethanol in vehicle fuels stemmed from unlabelled 20 per cent blends being sold into the market, and media reports of potential for vehicle engine damage to arise from using petrol with 20 per cent or more ethanol. In this context, the Government also considered a number of short-medium term options to support the biofuels sector, including: financial support for storage of EPGP recipients’ excess ethanol supplies (due to falling sales); as well as a pre-payment arrangement to offset suppliers’ storage costs until consumer demand levels improved.52

2.15 The debate within government at this time revolved around whether to respond to short term issues, a number of which were considered to have resulted from the commercial decisions of some producers.

2.16 In December 2003, a report entitled Appropriateness of a 350 million litre biofuels target53 was released. The report, commissioned by the Government, considered the feasibility of its policy objective of ‘biofuels contributing at least 350 million litres to Australian fuel supply by 2010’. The report concluded that:

- the biofuels industry would require substantial and ongoing assistance in order to meet a target of 350 million litres by 2010 (although ethanol produced from waste starch could be competitive with traditional fuels over the medium to longer term);

- if the 350 million litres target was met, there would be savings of approximately 268 000 tonnes of greenhouse gases (about 0.3 per cent of transport emissions), although this would come at a relatively high cost;

- meeting the target would reduce GDP in 2010 by approximately $70 million in 2010;

- the cost of each direct job created in the biofuels industry would be between $492 000 and $516 000; and

- the benefits of biofuels in terms of improving energy security54 are minimal because 350 million litres of biofuels represents only 1.1 per cent of Australia’s total motor vehicle fuel demand.

2.17 Overall, the report concluded that ‘the costs of implementing a policy of assisting the Australian biofuels industry to meet a 350 million litre biofuels target are estimated to exceed the benefits’.

2.18 On 16 December 2003, Prime Minister Howard announced an ‘overhaul of the fuel excise system’ to give effect to one of the key recommendations of the Fuel Tax Inquiry55: that excise should apply to all liquid fuels, irrespective of their derivation. Under the new arrangements, excise would be introduced for ‘alternative’ fuels—such as ethanol—based on the energy content of the fuels relative to petrol and diesel. In parallel, the Government also decided that it would provide a 50 per cent discount of the full energy content rate for alternative fuels. In relation to ethanol, the proposals meant that it would attract excise at a rate of 2.5 cents per litre from 1 July 2008, increasing by 2.5 cents per litre each year until it reached its ‘final’ discounted rate of 12.5 cents per litre on 1 July 2012.

Phase 3 - Second extension (2008-June 2011)

2.19 In a separate measure contained in the 2003-04 Budget, the (Howard) Government also announced that it would legislate to bring all previously untaxed fuels (which included ethanol and biodiesel, but also LPG, CNG and LNG) into the excise net in order to ‘promote long-term sustainability and move to a neutral tax treatment between competing fuels’.56 It proposed to do this by introducing specific legislation, known as the Energy Grants (Cleaner Fuels) Scheme Act 2004 (the EG(CF) Act). Under this arrangement, the EPGP would cease on 30 June 2008 (as described in paragraph 2.11) and both ethanol producers and importers would be entitled to EG(CF) grants, which were to be administered by the Australian Taxation Office from 1 July 2008.

2.20 In March 2004, in negotiations for the passage of the EG(CF) Act, the Government agreed to an amendment proposed by the Australian Democrats57 to defer the commencement date for the phase-in of excise from 1 July 2008 until 1 July 2011, effectively extending the subsidy for ethanol by three years. As a result of this decision, the EPGP would continue until 30 June 2011, when the EG(CF) grants would commence.

2.21 Ahead of the agreement with the Democrats, Prime Minister Howard received advice from his department in March 2004 that ‘the delay in extending excise to alternative fuels has a cost to revenue of $100m in 2008–09 rising to $290m in 2010–11 and 2011–12 and then declining to zero by 2015–16’.

2.22 In November 2007, the Rudd Government was elected. In February 2008, the new Prime Minister requested that the Minister for Resources and Energy and the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry undertake an internal review of existing biofuels policies. This internal review found no single compelling policy rationale for providing Commonwealth assistance to the biofuels industry and the benefits of regional economic development, enhancing energy security and improving public health outcomes are small and may be outweighed by the costs.58

2.23 In February 2009, Ministers considered the review report and recommendations by the two Ministers, which included closing the EPGP to new entrants, capping grant payments to new entrants and phasing out the EPGP. No decision was made by Ministers in response to this report.

Variation to second extension

2.24 In the 2010–11 Budget context, the Government considered a range of savings options to respond to increasing program costs. EPGP expenditure had grown from $77.6 million in 2008-09 to $104.9 million in 2009-10, and there was no discretion on payment levels under the existing demand-driven program arrangements. The Government decided to change the rate of excise on ethanol to 25 cents per litre from 1 July 2011, phasing down to 12.5 cents per litre from 1 July 2015. Over the same period, the rate of the ethanol subsidy would be reduced from a starting point of 22.5 cents per litre to zero, such that from 1 July 2015, ethanol producers would pay 12.5 cents per litre in excise, but receive no subsidy.

2.25 In May 2010, in the 2010–11 Budget context, the Assistant Treasurer stated:

The sudden loss in the relative tax advantage of domestic ethanol compared to imported ethanol that would have occurred under the policy announced by the previous government will be addressed. Entitlement to the Energy Grants (Cleaner Fuels) Scheme will be removed and direct subsidies will be provided to domestic producers and phased down over the transition period.

Phase 4 - Third extension (July 2011- June 2021)

2.26 Following the August 2010 federal election, and during negotiations with Mr Tony Windsor MP, the (then) independent member for New England, the (Gillard) Government agreed59 to continue the EPGP and the transition to the final excise rate until 30 June 2021.

2.27 The financial impacts of the agreement were considered by Ministers in October 2010 as part of the 2010 MidYear Economic and Fiscal Outlook and announced in the 2011–12 Budget.

2.28 On 12 May 2011, the day after the 2011–12 Budget, in the Second Reading speech for the Taxation of Alternative Fuels Legislation Amendment Bill 2011, the Assistant Treasurer said:

This bill also includes a commitment that renewable fuels (ethanol, methanol and biodiesel) do not pay effective excise. This commitment reflects discussions with our crossbench colleagues and industry on these longstanding reforms… The taxation and grant arrangements that currently apply to ethanol, namely application of fuel taxation to both imported and domestically produced ethanol with a grant for domestically produced ethanol, will be maintained for a period of ten years before a review is undertaken.

Phase 5 – Closure (2014-June 2015)

2.29 In the 2014–15 Budget, the current Government announced that the EPGP would be abolished with effect from 30 June 2015, with a transition path to payment of fuel excise60 commencing at 0 cents per litre from 1 July 2015 and increasing by 2.5 cents per litre per year.

2.30 In their consideration of options presented by Industry for closure of the EPGP, Ministers were alerted to the February 2014 report on the program by the Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics (BREE) (discussed below at paragraphs 2.35 to 2.36.). The BREE report indicated that the EPGP had not been successful in achieving its intended outcomes, in particular creating a viable ethanol industry in Australia.

2.31 Actual expenditure on the EPGP between 2002 and 2013–14 was $773.1 million, with estimated expenditure for 2014–15 of $122.1 million, totalling some $895 million over the life of the program.

Progress towards achieving EPGP program objectives

2.32 Prior to 2012, the EPGP program documentation made reference to Prime Minister Howard’s 12 September 2002 media release (see paragraph 2.9) that the EPGP was ‘part of the Government’s strategy to encourage the use of biofuels in transport’. In 2012, the EPGP Program Administration Guidelines were revised to include more explicit statements on its objective and outcomes, as follows:

Program objective

The objective of the Program is to support production and deployment of ethanol as a sustainable transport fuel in Australia.

The Program will provide fuel excise reimbursement of 38.143 cents per litre for ethanol produced and supplied for transport use in Australia from locally derived feedstocks.

Program outcome

The intended outcome of the Program is to:

(a) Encourage the use of environmentally sustainable fuel ethanol as an alternative transport fuel in Australia;

(b) Increase the capacity of the ethanol industry to supply the transport fuel market; and

(c) Improve the long term viability of the ethanol industry in Australia.

2.33 While ultimately a matter for government decision, during the program’s 12 years of operation, there was a consistent flow of advice from departments and external review opinion61, highlighting shortcomings in the overall policy approach.

2.34 In its report62 to the Government in February 2014, the National Commission of Audit recommended that the government abolish the EPGP, on the basis that:

The grant subsidises the production of fuel ethanol in Australia. It provides a benefit to a small number of Australian producers, skewing commercial decision making towards ethanol production, and distorting Australian markets for fuel and feedstock products. As the subsidy is not available for imported ethanol, it also provides protection from foreign competition and increases the consumer price of fuel ethanol blends. The environmental benefits are contestable, with the Productivity Commission (2011)63 finding the grants resulted in only marginal carbon dioxide abatement at a cost of over $500 per tonne of abatement.

2.35 Also, in February 2014, the Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics (BREE)64, within Industry, released a report entitled An assessment of key costs and benefits associated with the Ethanol Production Grants program. The report was intended to provide a concise high level assessment of the impacts of the Australian Government’s Ethanol Production Grants (EPG) Program. In doing so, it examined the key costs and benefits associated with the program’s operation and the resultant Australian ethanol production. The report concluded:

- the annual cost of the program to the taxpayer is significant. Two of the key economic and environmental benefits from ethanol production, notably regional employment65 and greenhouse gas abatement, are estimated to be relatively modest but come at a high to very high cost;

- the health benefits that accrue from reduced air pollution are also relatively modest and declining. The small and concentrated nature of the industry also provides no real benefit in terms of Australia’s liquid fuel security and in fact may be slightly negative;

- there would appear to be no net benefit for agricultural producers as feedstock used is either waste/residue product or would have been sold into other markets;

- while the EPG program clearly supports an additional lower priced fuel product for consumers, the benefits to motorists are also less than they should be66;

- there is no evidence to suggest that provision of support for the Australian ethanol industry through the EPG program provides downward pressure on retail petrol prices or materially increases retail market competition in a sustainable way; and

- that an expanded Australian ethanol industry based on market priced feedstock was considered unlikely to be commercially viable in the absence of the EPG rebate.67

2.36 The BREE assessment report comprises a useful economic analysis and synthesis of internal program data and other evidence and research, including from external sources, on the EPGP’s achievements against its stated objective and intended outcomes. In essence, the BREE came to much the same conclusion in 2014 as the 1996 program evaluation of the Ethanol Bounty68 on which the EPGP was largely modelled. The 1996 evaluation had observed that the Ethanol Bounty Scheme ‘in its current form, will not achieve its objective and should be discontinued at the current time’.69

Conclusion

2.37 The Australian Government announced the closure of the Ethanol Production Grants Program (EPGP) in the context of the 2014-15 Budget. While originally established as a one year assistance measure, the EPGP operated for 12 years at a cost of some $895 million, with successive governments extending the program on three occasions.

2.38 The EPGP is a grants program currently administered by the Department of Industry and Science (Industry). The 2012 program objective was to support the production and deployment of ethanol produced from locally derived feedstocks as a sustainable transport fuel in Australia. The intended program outcomes were to: improve the long term viability of the ethanol industry in Australia; increase the capacity of the ethanol industry to supply the transport fuel market; and encourage the use of environmentally sustainable fuel ethanol as an alternative transport fuel in Australia.

2.39 At the outset of the program and at key phases in the program’s life, the administering department and central coordinating agencies consistently highlighted shortcomings in the overall policy approach and drew attention to the EPGP’s limited success in achieving its program objectives. In their advice, entities drew on international experience and available Australian evidence, including experience with the earlier Ethanol Bounty Scheme on which the EPGP was largely modelled. A 1996 program evaluation of the Ethanol Bounty Scheme had observed that it would not achieve its objective and should be discontinued.

2.40 At a number of key program phases, external and internal reviews were commissioned to inform government decisions on the EPGP. In particular, a 2014 report by Industry’s Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics (BREE) provided a concise high level assessment of the program’s costs and benefits70, leading soon after to the Australian Government’s decision to close the program.71

2.41 In 201314, only three ethanol producers were in receipt of EPGP support. When the program was introduced in 200203, it was suggested that up to a further 15 domestic ethanol plants might be established across Australia. While the program has directly supported a small number of grant recipients72, in some cases for an extended period73, the program has had limited success in achieving the program outcome of improving the long-term viability of Australia’s domestic ethanol industry. In 2014, the BREE considered that an expanded Australian ethanol industry based on market priced feedstock was considered unlikely to be commercially viable in the absence of the EPG rebate. The BREE further concluded that realisation of expected indirect benefits—including regional development, environmental and health benefits—has been modest at best, and/or at a much higher cost than could be achieved using more direct forms of government support.

3. Program Administration

This chapter examines the administration of the Ethanol Production Grants Program with a focus on activity since 2007–08.

Introduction

3.1 The EPGP is a demand-driven grants program whereby eligible producers who have a funding agreement with the Commonwealth are reimbursed for excise paid to the ATO, usually on a weekly basis. To be eligible for grants under the EPGP, applicants must:

- be an Australian entity incorporated under the Corporations Act 2001;

- produce and supply ‘eligible ethanol’74; and

- not have been named as an entity that has not complied with the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Act 1999.75

3.2 There are no additional, merit-based, criteria under the program framework agreed by the Government in 2002. Applications for funding can be submitted to the department for assessment at any time; therefore, the department does not manage formal funding ‘rounds’ as such, but will assess applications upon receipt. Under all EPGP program guidelines, approved by the relevant Minister at certain times (see paragraph 3.10), authority for making decisions on program eligibility and funding has been delegated to departmental officers.

3.3 The EPGP, as an Australian Government grant program, was subject to the financial management framework established by the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (the FMA Act) and its associated Regulations from 2002 to June 2014.76 Since 2009, entities responsible for grants administration have also had to comply with the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs).77 The EPGP program guidelines provide that the department must administer the program in accordance with the Australian Government’s financial management and accountability framework, including the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines.78

3.4 In assessing Industry’s administration of the EPGP since 2007-0879, the ANAO has examined: the EPGP’s compliance with the relevant financial framework requirements and CGGs; as well as the following aspects of program administration:

- program planning and design;

- program guidelines and procedures;

- application and assessment;

- funding arrangements;

- claims for payment and monitoring compliance; and

- program reporting.

Program planning and design

3.5 The ANAO’s 2002 Better Practice Guide (BPG) on grants administration observed that ‘effective planning is the cornerstone of an economic, efficient and effective grant program’.80 The BPG also highlighted the importance of well-designed program guidelines81 and reporting arrangements.82

3.6 On 12 September 2002, when Prime Minister Howard announced the establishment of the EPGP as a ‘short-term production subsidy’, he also stated that this initiative would commence from 17 September 2002, less than one week from the date of his announcement. The key program design parameters—a demand-driven grant program whereby eligible applicants would be fully reimbursed for fuel excise paid on ‘eligible ethanol’—were also settled by senior ministers in September 2002.

3.7 In this context, the administering department83 had very limited time to design and plan for the implementation of the program.84 Further, the EPGP was originally announced as an interim measure, and the initial administrative arrangements were not fully developed; chiefly comprising a funding agreement setting out the terms and conditions of program funding, but not a set of formal program guidelines and reporting arrangements.

3.8 In the 2003-04 Budget, the Government decided to extend the EPGP until June 2008. The department then took the opportunity to formalise aspects of the program, such as the development of formal program guidelines and reporting requirements by grant recipients; placing its grants administration on a sounder footing.

Program guidelines and procedures

Guidelines

3.9 The guidelines established for a granting activity play a central role in the conduct of effective, efficient and accountable grants administration. Grant guidelines should be fit for purpose (having regard to the policy objective of the granting activity) and support the decision-maker’s capacity to demonstrate that funding decisions have been taken in accordance with the relevant statutory and policy requirements.85 Successive ANAO Better Practice Guides on grants administration and the 2009 CGGs86 also highlighted the long-established expectation that grant programs should operate under clearly defined and documented operational objectives. The operational objectives should be clearly linked to the outcomes set by government for the grant-giving organisation.87

3.10 The first edition of the EPGP program guidelines was approved by the then Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources on 23 November 2004. The guidelines were subsequently revised and reissued a further six times to reflect successive governments’ various decisions, particularly extensions, to the EPGP over time,88 and the evolving framework for grants administration.89

3.11 While successive editions of the EPGP guidelines incorporated background references to Prime Minister Howard’s 12 September 2002 statement (see paragraph 2.9) that the EPGP was ‘part of the Government’s strategy to encourage the use of biofuels in transport’, it was not until 2012 that the EPGP Program Administration Guidelines included more explicit statements on its objective and outcomes (see paragraph 2.32). It would have been preferable that program objectives and outcome statements were more formally and explicitly included in the guidelines from the start of the program.

3.12 The 2009 and 2013 CGGs required entities to:

- develop and make publicly available grant guidelines for all new granting activities (including grant programs)90;

- ensure that grant guidelines and related operational guidance are consistent with the CGGs91; and

- promote ‘open, transparent and equitable access to grants’ by, for example, including relevant program documentation (such as the guidelines) on their websites.92

3.13 The 2013 CGGs introduced a further requirement that entities must complete a risk assessment of new grant activities and new or revised grant guidelines, in consultation with the Department of Finance (Finance) and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).93

3.14 The ANAO assessed the EPGP 2012 and 2014 program guidelines against the 2009 and 2013 CGG requirements, respectively. The ANAO found that, for both editions, the program guidelines generally reflected, and were developed in accordance with, the CGG requirements discussed above. In consultation with Finance and PM&C, the overall program risk was assessed as low, and both sets of guidelines were approved by the relevant portfolio minister. The 2012 and 2014 EPGP program guidelines were also published on the department’s website.

Procedures

3.15 Operational guidance, including in the form of a procedures manual, is a useful tool for staff administering a grant program to ensure consistency in, for example, processing of claims. The CGGs encourage entities to develop such policies, procedures and guidelines as are necessary for the sound administration of grants, including operational guidance for the administration of the program, consistent with financial framework requirements.94

3.16 While some procedural guidance was available to staff in earlier program phases, at the time of the current audit there was no explicit procedural document for staff administering the EPGP. The department advised in May 2014 that due to the straightforward nature of the program, it considered that operational guidance such as a procedures manual was not necessary.

3.17 The ANAO did not identify any significant procedural shortcomings for the period examined in the audit. However, in the context of a small administrative team95 oversighting a large expenditure program, there is potential for program administration to be disrupted by the absence or loss of a key officer. Appropriate documentation of relevant key procedures would have been prudent, reflecting better practice and the Government’s expectations as expressed in the CGGs since 2009.

Application and assessment

3.18 The application and assessment process for a granting activity should promote open, transparent and equitable access to the program, with any eligibility or threshold criteria easily understood and effectively communicated to potential applicants. Information obtained from applicants should also be sufficient to properly inform funding decisions. The basis for recommendations and decisions at all stages of the grant process must be effectively documented.96

Application process

3.19 When the EPGP opened in 2002, the department decided to inform potential applicants of the program by emailing the (then) known ethanol producers to advise them of the program’s existence and invite them to participate. Three existing Australian ethanol producers were approached directly by the department and the scheme was not advertised. Those producers who wished to participate in the program were required to supply certain information, to satisfy the eligibility criteria—being an Australian entity incorporated under the Corporations Act 2001, and a producer of ‘eligible ethanol’. Producers were also asked to provide estimates of ethanol production, to assist with program expenditure estimates, prior to being offered a funding agreement. Two of the companies contacted by the department commenced participation in the program in 2002–03, while the third entered the program in 2003–04. As the three companies initially contacted did not submit formal applications for funding, the ANAO noted that only two formal applications have been received by the EPGP: in 2006 and in 2008.

3.20 The ANAO reviewed the information and advice currently available to potential EPGP applicants, as well as the application and assessment process for the 2008 applicant—the only one during the time period within the scope of the audit.

3.21 The department’s website provides the following guidance to prospective EPGP applicants:

- the current Program Administrative Guidelines;

- an Initial Enquiry Form;

- an Application for Funding; and

- a sample Funding Agreement.

3.22 The current publicly available materials are relatively clear, and provide potential applicants with sufficient information to make an initial enquiry about program eligibility as well as understand the information requirements associated with a formal application. The available materials also set out the key program requirements, including eligibility criteria, monitoring, reporting and compliance arrangements.

Assessment process

3.23 For the 2008 application reviewed by the ANAO, the applicant provided both a completed Initial Enquiry Form followed by a formal application in September 2008. While there was evidence that the department confirmed that the applicant was ‘an Australian entity incorporated under the Corporations Act 2001’ (one of the mandatory eligibility criteria), the department was not able to assess the ‘eligible ethanol’ criterion, because at the time of application, the applicant had not commenced production of ethanol. In this context, the department did not document its assessment, for the benefit of the program delegate, whether the applicant met or was likely to meet the ‘eligible ethanol’ criterion; a key consideration in assessing whether the application would represent a ‘proper use’ of Commonwealth resources.97 In this case, it would have been appropriate for the delegate to consider approving EPGP funding on a conditional basis, subject to further inquiries in due course regarding the production of ‘eligible ethanol’. In the event, the department adopted a comparable course of action when, 18 months later in March 2010, it conducted a compliance audit of the then grant recipient to satisfy itself that all EPGP payments had been for ‘eligible ethanol’ (see paragraph 3.37). This approach could usefully have been documented as part of the approval process for the grant, to help the department demonstrate its consideration of ‘proper use’ before payments were made.98

Funding arrangements

3.24 A well-drafted funding agreement provides for a clear understanding between the parties on required outcomes. It represents a formal legal arrangement between the Australian Government (the Commonwealth) and program participants; it should establish relevant accountabilities and set out the agreed terms and conditions of the funding assistance, including performance information, access requirements, as well as clearly defined roles and responsibilities of all parties.99

3.25 In addition, the FMA Regulations imposed specific obligations on entities in relation to entering into financial commitments with third parties. While the specific regulations that apply have changed from time to time, the overarching principle is that an official must not enter into an agreement which may financially commit the Commonwealth unless a properly authorised person (known as an approver) has considered and approved a number of matters, including whether the agreement would constitute ‘proper use’ of Commonwealth resources.100 Such authorisations101 must be in place before the proposed commitment of expenditure can be entered into.

3.26 The ANAO examined the content, as well as the relevant FMA approvals and authorisations, for all (20) funding agreements, including variations, executed with the EPGP recipients from 200708.

EPGP funding arrangements from 2007-08

3.27 The ANAO’s examination of the EPGP funding agreements found these agreements generally covered key program requirements such as: claiming and payment processes; provisions for prompt refund or recovery (including interest, where applicable) for any breaches of the agreement; grant acquittal and reporting; publication details; record-keeping, inspections and audits; and provisions for varying or terminating the agreement. For the purpose of ongoing program monitoring, the funding agreements generally provided a sound foundation for program administration.

3.28 The EPGP funding agreements were not used to assist the department’s monitoring of achievements against the program’s broader outcomes and expected benefits (such as the impact of the program on regional employment). The funding agreements required recipients to provide information of direct relevance to the EPGP’s administration, such as the amount of ethanol produced and an estimate of future production. The department advised that it was able to draw upon other sources of information for broader monitoring purposes.

3.29 For the 20 funding agreements executed between 2007-08 and 2013-14, the ANAO found that the key financial framework requirements had been observed for 13 funding agreements. In the eight instances where an approval under FMA Regulation 10 was required, the ANAO found these requirements had been observed. However, the department was unable to provide evidence that the relevant expenditure approvals (FMA Regulation 9) had been prepared for seven of the 20 agreements, prior to their execution.102

Claims for payment and monitoring compliance

Processing claims

3.30 After establishing an agreement covering a defined funding period, the process for participants to claim EPGP payments involves submitting a claim for payment, supported by a copy of the ATO Excise Return Form—showing the amount of excise reported and paid to the ATO—together with evidence (such as a bank statement) of the excise paid to the ATO.103

3.31 This claims documentation process is intended to help the department confirm that EPGP payments made to program participants match precisely the amount of excise paid to the ATO, providing a measure of assurance of its program expenditure.

3.32 To support the claim assessment process, the department has developed a template for use by program staff with inbuilt formulae that calculates the amount payable based on the amount of ethanol the claimant reported as excisable. The template also prompts staff to confirm the provision of supporting documentation. Payments are authorised by two separate staff members within the relevant division—one being the program manager—prior to processing by the department’s central finance unit.

Acquittal of grant payments

3.33 EPGP payments are acquitted every quarter by assessing quarterly reports provided by each program participant. Under the terms of the funding agreements, quarterly reports provided by grant recipients must include an original signed letter from the ATO confirming the total excise paid during the preceding quarter, as well as providing information on:

- the total volume of eligible ethanol produced (in litres);

- the amount of excise paid the ATO;

- the value of any excise refunded or offset by the ATO;