Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Establishment of the Workforce Australia Services Panel

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- To provide assurance to the Parliament on the design and establishment of the Workforce Australia Services Panel and to examine whether the procurement conducted was effective and consistent with achieving value for money.

Key facts

- Planning for the New Employment Services Model (NESM) commenced in 2018, which aimed to reduce long-term unemployment through providing ‘enhanced services’ to vulnerable job seekers alongside the delivery of a new Digital Employment Services Platform.

- Three procurements were conducted through the NESM Request for Proposal, with one of these processes (for Enhanced Services) resulting in the establishment of the Workforce Australia Services Panel.

- 99 of the 113 provider organisations (88 per cent) evaluated were appointed to the panel. Of these, 43 were issued with 178 licences to deliver Enhanced Services across 51 employment regions.

What did we find?

- The establishment of the Workforce Australia Services Panel and the award of business to employment services providers was largely effective.

- The design of the procurement process was largely consistent with the Australian Government’s policy objectives.

- The procurement process was largely conducted in accordance with the published process.

- The results of the evaluation process appropriately informed the award of business to successful providers. The establishment of the Workforce Australia Services Panel was not informed by an appropriate value for money assessment.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made three recommendations to the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (the department) to improve procurement planning, contract management and promoting the independence of probity advisers.

- The department agreed to two recommendations and agreed in part to the other recommendation.

1192

conformant Enhanced Services proposals received by the department.

1176

proposals considered by the Tender Review Committee for Enhanced Services.

91%

of Enhanced Services proposals evaluated by the Tender Review Committee appointed to the panel.

Summary and recommendations

Background

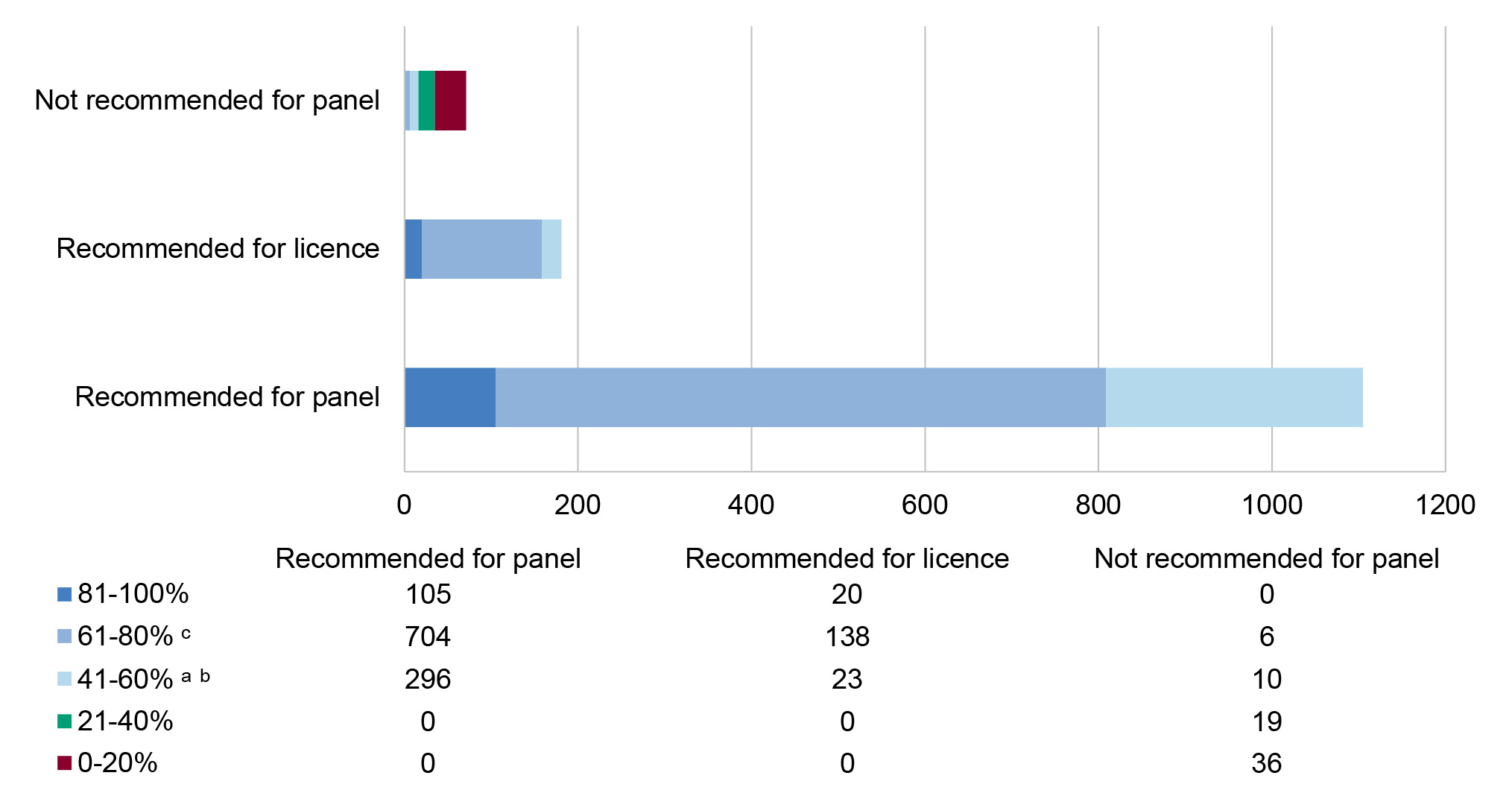

1. The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR or the department) commenced planning in 2018 for the delivery of a New Employment Services Model (NESM). This arrangement was to replace the previous employment services program, jobactive, which had been in place from 1 July 2015. The planning process included the establishment of an Employment Services Expert Advisory Panel (the expert panel), which provided 11 recommendations in October 2018 around improving outcomes for job seekers through the employment services system.

2. In September 2021, the department undertook the NESM procurement process to establish a panel of service providers to deliver employment services to at-risk job seekers. The department evaluated proposals between October 2021 and February 2022, and notified providers of the outcomes in March 2022. Work orders were executed in July 2022 for the commencement of the new program — Workforce Australia — from 1 July 2022. The Workforce Australia Services Panel was established through this procurement process.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. The audit was conducted to provide independent assurance to the Parliament on the design and establishment of the panel arrangements for the program, including whether the procurement process conducted was effective.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the establishment of the Workforce Australia Services Panel. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Was the design of the procurement consistent with policy objectives and achieving value for money?

- Was the procurement conducted in accordance with the published process?

- Did the results of the evaluation process appropriately inform the establishment of the panel?

Conclusion

5. The department’s establishment of the Workforce Australia Services Panel was largely effective.

6. The design of the procurement process was largely consistent with the Australian Government’s policy objectives for the New Employment Services Model (NESM). Four key ‘transformational’ changes were to be implemented, including a new regulatory licensing framework for employment services through legislative amendments. A contractual licensing model through a procurement process was adopted, rather than the establishment of a legislative regulatory framework. The design was intended to give effect to the underlying policy intent of easier entry and exit of providers from the market through the establishment of a panel of providers. Proposal documentation was made publicly available when the tender process opened for submissions. An appropriate evaluation process was established and probity arrangements commensurate with the risk and scale of the procurement were established. Not all aspects of the probity plan were executed.

7. Financial viability analysis was undertaken by KPMG in 2020 and 2021 to provide advice to the department on whether providers would be viable under the new policy settings, including operating with a target caseload to staff ratio of 80:1 to provide these more intensive services. The analysis indicated that there remained at least two and up to 12 employment regions that were unlikely to be able to support a single provider under the final policy settings for the new model.

8. The department’s procurement process was largely conducted in accordance with the published process. All proposals were received, and compliant proposals assessed, in line with the published process. Delays in the implementation of a new IT system, the Procurement and Licence Management System (PaLMS), contributed to delays in the procurement activities. The detailed evaluation methodology for NESM proposals was finalised after the release of tender documentation, with shortcomings in the design features not apparent until late in the assessment process. While appropriate processes were established to support compliance with internal probity frameworks, some key elements were not fully implemented.

9. The results of the evaluation process appropriately informed the award of licences to successful employment services providers. The establishment of the Workforce Australia Services Panel was not informed by an appropriate value for money assessment, with 362 (41 per cent) of the 893 proposals — from 84 of the 99 providers appointed to the panel — scoring less than 50 per cent against one or more of the evaluation criteria. Although these providers may not be best placed to deliver the intensive and tailored services required in some regions, they remain available for selection for gap-filling requirements in accordance with the department’s Panel Maintenance Guide. This places greater importance on assessing for value for money each time the panel is used over the life of the program.

10. The ‘special conditions’ offered by providers in their tender submissions were not captured in the executed deeds in July 2022. By August 2023, the department had identified all commitments deemed relevant to the award of licences and notified the respective providers of their contractual obligations to deliver the commitments made during the RFP process.

11. As at October 2023, the department had not yet used the panel. Where a need arose due to the exit of the one provider in the Broome region (due to financial unviability), a limited tender process was conducted, and a new ‘hybrid’ employment services model was announced in May 2023. The Broome region was consistently found to be not viable for supporting a single provider throughout the KPMG analyses in 2020 and 2021.

Supporting findings

Design and implementation

12. Learnings identified through discussion papers and public consultations conducted by the Employment Services Expert Advisory Panel (the expert panel) between January and October 2018 informed the design of the new program. In December 2018, the Australian Government agreed that ‘transformational’ changes from the jobactive program would underpin the NESM, including:

- the implementation of job seeker self-service through a digital services platform;

- more intensive support for the job seekers needing the most help; and

- a ‘licensing framework’ to lower barriers to entry and exit for providers, more effectively drive quality outcomes, and reduce the cost and disruption of procurement processes. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.9)

13. The Australian Government’s policy intent was largely reflected in the design of the new model. Key aspects included: intensive support and case management for disadvantaged job seekers; lowering the consultant to job seeker caseload ratio; and allowing low risk job seekers to self-manage online through a new digital services platform. A point of difference from the expert panel’s envisaged model was the establishment of the NESM through a procurement process rather than a statutory licensing framework. In this respect, the department advised the Minister that greater risks were associated with a ‘statutory licensing model’ and a procurement process could still give effect to the policy objectives. This involved designing a process that would reduce barriers to entry for new, small and/or specialist providers, including by:

- allowing providers to tender for ‘part region’ servicing;

- applying weightings to criteria to lower the importance placed on providers’ past performance, while increasing the importance on local community knowledge and connections; and

- establishing a panel arrangement through a deed of standing offer, with successful providers to be issued a ‘contractual licence’ through executed work orders.

14. Findings from the New Employment Services Trial (NEST) pilot enabled key policy settings to be tested and refined between July 2020 and September 2021, with changes informing the NESM Request for Proposal (RFP). Financial viability analysis was conducted throughout the pilot to provide assurance that providers could be viable under the new policy settings, including operating with a target caseload to staff ratio of 80:1. Steps were taken to improve the viability of providers, such as increasing certain outcome payments and the national market share cap. However, the analysis indicated that there remained at least two and up to 12 employment regions that were unlikely to be able to support a single provider under the final policy settings for the new model. (See paragraphs 2.10 to 2.41)

15. The RFP documentation was made publicly available when the tender process opened for submissions on 8 September 2021. Three weighted evaluation criteria and 18 sub-criteria questions were included, with each criterion comprising between four and nine sub-criteria questions. While not identified in the RFP, criteria weightings were evenly distributed across the 18 questions. (See paragraphs 2.42 to 2.53)

16. An appropriate evaluation process was established, with a high-level overview of that process included in the published RFP. Limited information on the evaluation process was otherwise provided. Key internal guidance to support the evaluation process was not timely. This guidance was to be included in the ‘NESM Purchasing Plan’, which required Delegate approval before the RFP closing date and opening of the tender box. While the Delegate’s approval was obtained, the required contents — including the NESM Business Allocation Guideline and the NESM Assessment Guide — were not included in the approved plan. This guidance was developed later, in parallel with the assessment process throughout November and December 2021, and approved by the Chair of the Tender Review Committee (TRC), rather than the Delegate. (See paragraphs 2.54 to 2.63)

17. Probity arrangements commensurate with the risk and scale of the procurement were established in the January 2021 NESM probity plan. Appropriate protocols and processes were put in place to record and manage probity risks, including the completion of mandatory probity undertakings and conflicts of interest declarations. An external probity adviser was appointed in July 2020 to provide both procurement process and probity advice for employment services purchasing activities. While this represented the replacement of the incumbent adviser, in that role since August 2015, the incoming adviser had been engaged regularly for other services between 2019 and 2022. The probity plan included a provision that a further independent probity audit may be undertaken. While this was a new option that had not been included in previous probity plans, a probity auditor was not engaged. (See paragraphs 2.64 to 2.76)

Evaluation process

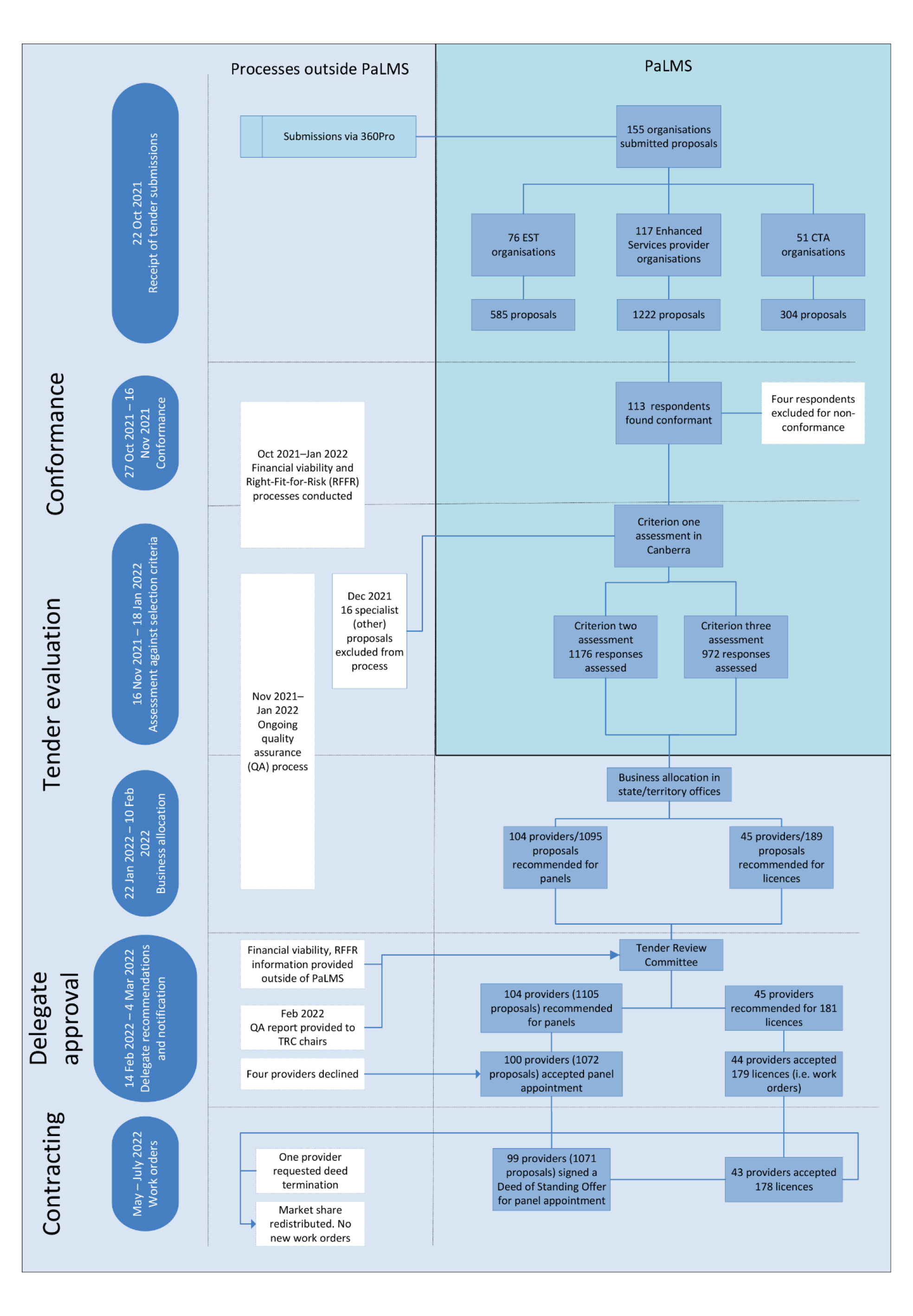

18. Tender proposals for the NESM were received through the online portal specified in the request documentation. In total, 155 respondents submitted 2111 complete proposals across the three NESM service areas. Incomplete proposals (of which there were three) were excluded from further consideration prior to the conformance assessment stage. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.6)

19. Non-compliant proposals were removed from consideration prior to the evaluation process. The request for proposal documentation allowed the department to exercise discretion during the conformance stage, which the department exercised in 39 instances in relation to ensuring respondents had supplied satisfactory tax records (STR) statements from the ATO. The department assessed that six of the 155 NESM respondents had submitted non-compliant bids and removed these from further consideration. This included four respondents who submitted proposals for Enhanced Services. (See paragraphs 3.7 to 3.16)

20. Detailed evaluation processes were developed after the RFP was published. Compliant proposals were assessed largely in accordance with the limited publicly available information and in parallel with the implementation of the new Procurement and Licence Management System (PaLMS). The assessment methodology was largely based on the previous jobactive process, with modifications to reflect the new policy settings and to accommodate the workload associated with conducting seven procurement processes by June 2022. This combination resulted in the following shortcomings in the evaluation process.

- Delays in the development of guidance documents and reduced training for assessment staff, many of whom were contracted staff.

- Optimistic advice provided to Ministers on the delivery timeframe for PaLMS, which was used for the assessment process and delivered as part of Tranche 1 of the broader Digital Employment Services Platform.

- Assessment scoring variations for individual regions were identified during the final stages of the assessment process. While these instances were later confirmed in quality assurance and internal review processes post-assessment, the methodology meant that other variations may not have been identified as a global approach was not undertaken throughout the process.

- Reliance upon a methodology of averaging providers’ region-specific star ratings nationally to assess existing providers’ demonstrated performance, and an additional evaluation process being introduced in November 2021 for proposal categories not identified in the tender documentation. (See paragraphs 3.17 to 3.55)

21. The overall scores and relative rankings of proposals were examined as part of the ‘Business Allocation’ process in late January and early February 2022 and used to create orders of merit for each employment region. These assisted State Office business allocation teams to:

- identify the respondents with ‘suitable’ proposals and recommend that they be appointed to the panel for the respective employment regions; and

- recommend which of those providers on the panels should be awarded a licence, along with the percentage of market share to be awarded to those licensed providers.

22. A total of 104 respondents (with 1095 proposals) were recommended to the TRC for appointment to a panel, with 45 of those respondents (with 189 proposals) to be offered licences across the 51 employment regions. Any ‘special conditions’ offered within proposals were to be identified in assessment reports and a ‘national consistency review’ conducted to ensure balance in provider coverage and market share across state boundaries. These processes were either partially implemented or not undertaken at the business allocation stage and therefore did not inform advice to the TRC. (See paragraphs 3.56 to 3.74)

23. Procurements examined by the ANAO were conducted ethically and appropriate processes were established to support compliance with the department’s internal probity frameworks. However, some key elements were not fully implemented. For example:

- the probity issues register did not contain all important or high-risk probity issues, including the recruitment of two previously employed senior departmental officials by potential respondents; and

- the probity undertakings and conflicts of interest (COI) registers were incomplete and, in some areas, inaccurate.

24. The department was not able to demonstrate that all 711 project personnel listed across its probity registers had completed all three COI declarations and probity undertakings, with:

- 209 (29 per cent) recorded as having completed all three;

- 127 (18 per cent) completing at least one of the three components; and

- 375 (53 per cent) not completing any of the three components.

25. Not all key project personnel submitted COI declarations, including the Delegate and seven TRC members. Where declarations were provided, not all conflicts were declared, with at least five NESM project personnel providing generic information such as friendships with a ‘number of former departmental employees who now work for employment services providers.’ Management strategies involved reducing IT access, recusal from work related to those providers and reduction of NESM-related involvement. (See paragraphs 3.75 to 3.95)

Procurement outcomes

26. Providers recommended by the TRC for the award of licences were those it considered had the best value for money proposals in the respective employment regions. Panel membership was determined by a threshold score of more than 40 per cent against criterion one. As a result of this approach, 104 providers (with 1105 conformant proposals) were recommended for panel appointment irrespective of their overall score or results against criteria two and three (which were each worth 40 per cent of the total score). Of those 1105 proposals:

- 181 (16 per cent) were recommended for licences; and

- 924 (84 per cent) were recommended for appointment to one or more regional sub-panels without licences.

27. Of those 924 proposals recommended for a sub-panel, 376 (41 per cent) of these from 88 providers had scored less than 50 per cent against one or more of the evaluation criteria. According to the department’s Panel Maintenance Guide for gap-filling requirements, if ‘no suitable organisation exists’ on the relevant sub-panel, any of these 88 providers could be approached through a limited tender process and potentially awarded a licence in any employment region. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.24)

28. Provider coverage across employment regions was appropriately addressed in the TRC’s advice to the Delegate. While coverage was a priority, it was often balanced against provider viability concerns during the TRC’s deliberations. Provider coverage was considered within the context of individual employment regions, with the aim of enabling job seekers to be appropriately supported without unreasonable obstacles to accessing services. Consistent with earlier stages of the procurement, the TRC’s deliberations were impacted by issues that emerged earlier in the assessment process. Specifically, these involved TRC concerns with the consistency of proposal evaluations, and as such, scores needing to be re-examined. (See paragraphs 4.25 to 4.35)

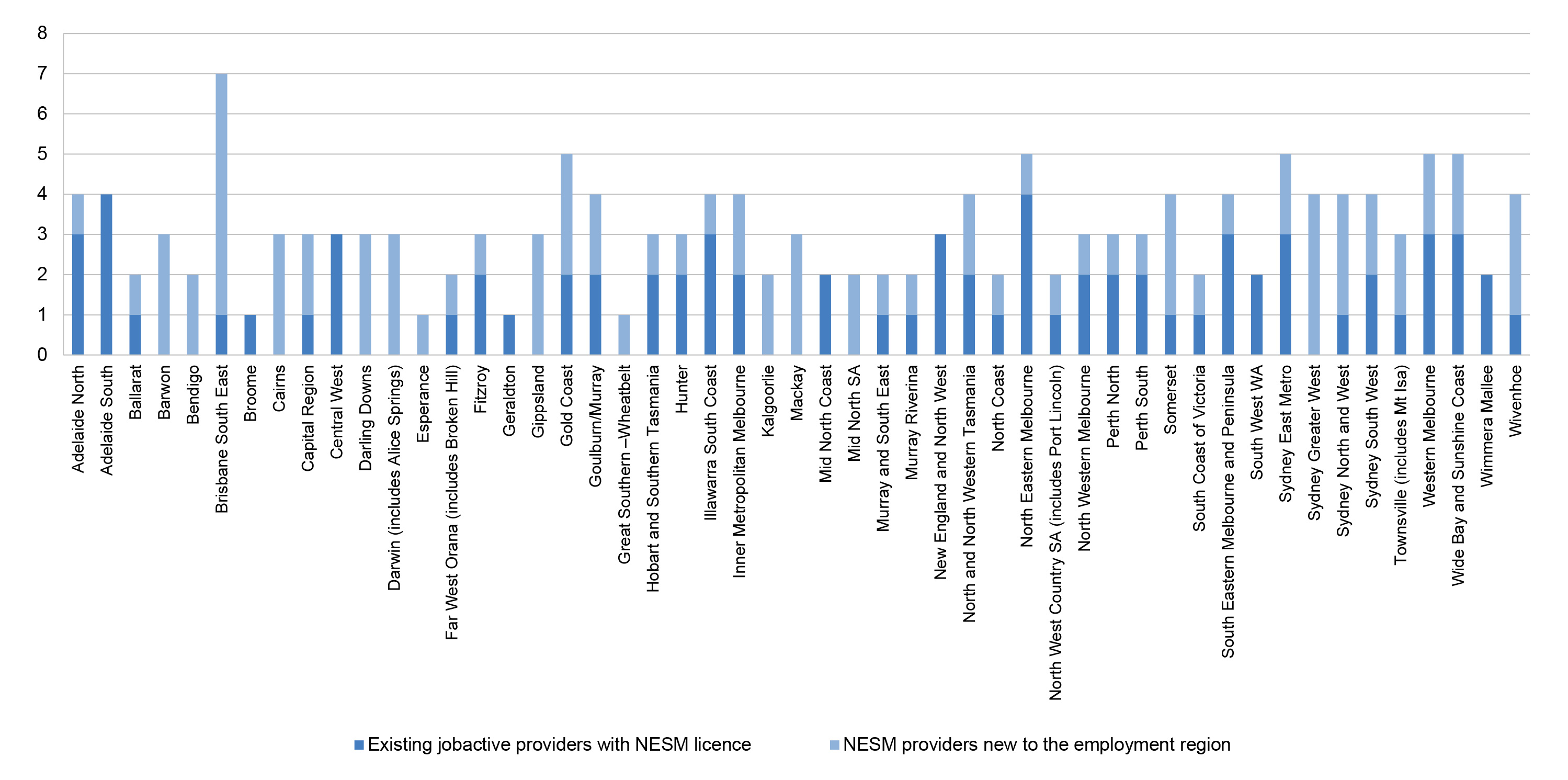

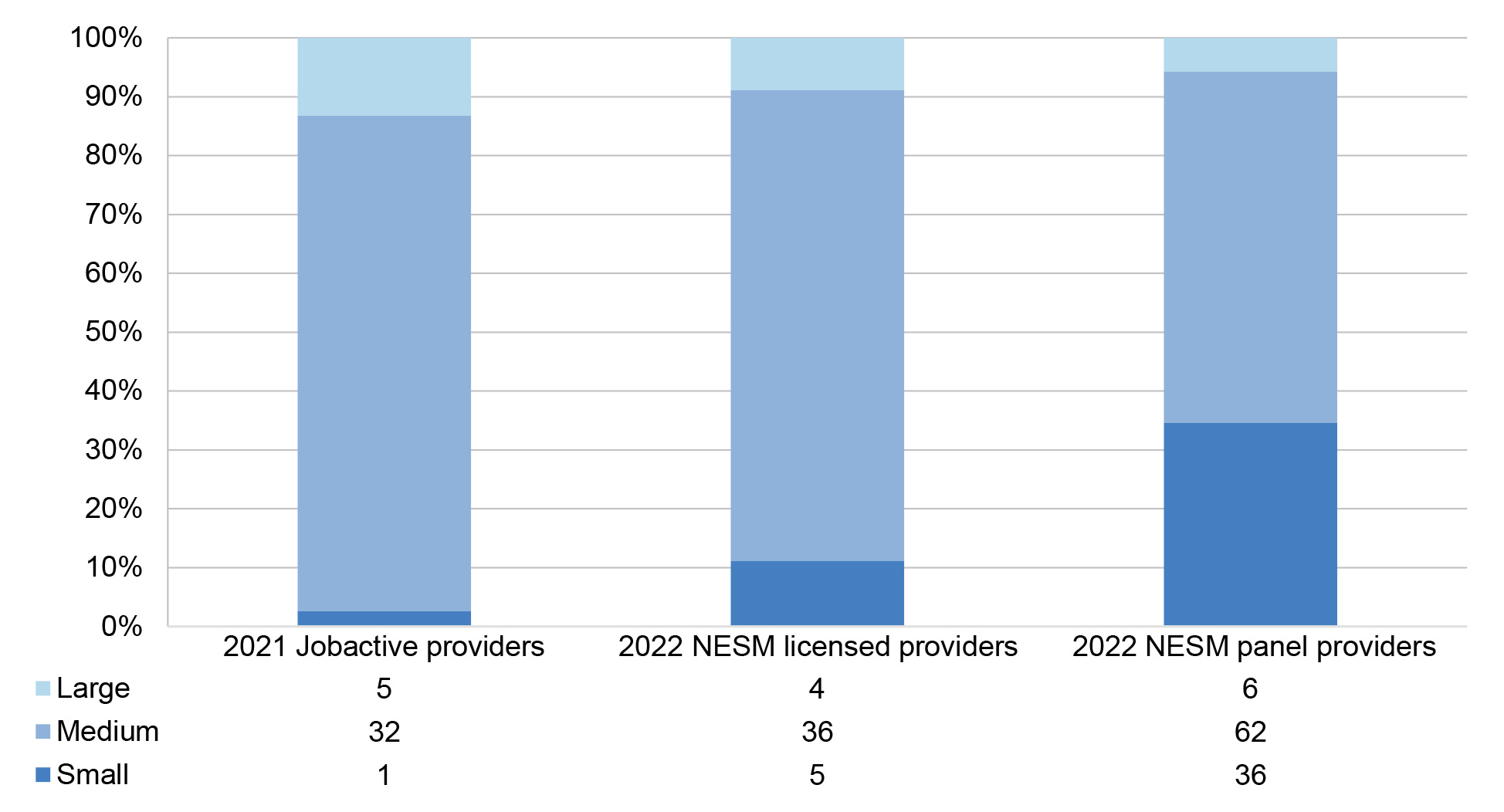

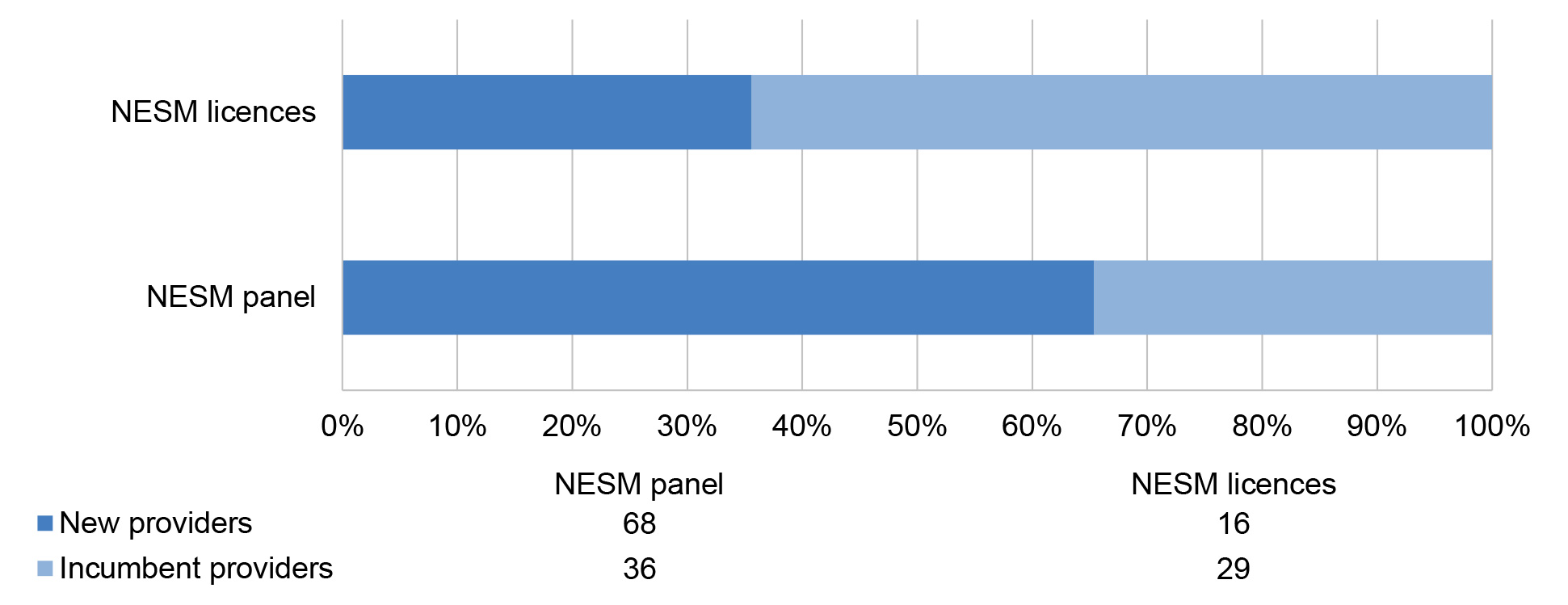

29. Consistent with the TRC’s recommendations, the Delegate approved 104 providers for appointment to the Workforce Australia Services Panel and 45 providers for 181 licences for the provision of Enhanced Services under the NESM. Five providers subsequently declined the department’s offer due to viability concerns, resulting in the panel being established in July 2022 with 99 panel members, of which 43 providers were issued 178 licences. The allocation of those licences resulted in:

- 15 employment regions experiencing a total turnover of providers with no previous jobactive providers being awarded business share, and six regions with no new providers awarded business share;

- 36 small providers appointed to the panel (representing 35 per cent of panel membership), of which five were offered licences (11 per cent of licence holders), representing an increase from the one small provider under jobactive;

- 68 new providers appointed to the panel, of which 16 of those (24 per cent) were offered licences; and

- 36 incumbent jobactive providers on the panel, with 29 of those (81 per cent) offered licences.

30. In February 2022, the department commenced work to capture ‘key service commitments’ offered by providers in their proposals. As at August 2023, the department had identified those commitments it deemed necessary to monitoring and compliance purposes and notified the respective providers in writing of their obligations to deliver those services, consistent with their proposals or as negotiated with the department.

31. Implementation commenced in July 2023 for a new ‘hybrid’ employment services model in the Broome region, following the exit of the sole provider due to financial unviability. The new servicing model is to be supported by APS staff and involves a new payment framework and a new provider, selected through a limited tender process (under the Indigenous Procurement Policy) in September 2023. The Broome region was consistently found not viable for supporting a single provider throughout the KPMG analyses in 2020 and 2021. (See paragraphs 4.36 to 4.63)

32. The department notified respondents promptly in writing of the procurement outcomes on 11 March 2022. Respondents were able to request a verbal debriefing within one month of notification and the department was to provide feedback (via teleconference) within three months. In total, 52 debriefing requests were received from Enhanced Services respondents. On average, the department took 84 days to respond to each request. Feedback provided through debriefing sessions was largely scripted. This allowed a consistent approach across providers but resulted in high-level feedback being provided, which lacked the depth required to assist providers to improve their future proposals. (See paragraphs 4.64 to 4.70)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.70

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations improve its procurement framework to specifically address the engagement of probity advisers, including ensuring that advisers are independent and objective by not engaging the same probity advisers on an ongoing or serial basis or for overlapping tasks such as procurement and probity advice.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations response: Agreed in part.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.71

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations strengthen its procurement planning activities, including by ensuring evaluation processes are sufficiently developed prior to the release of tender documentation and testing that new IT systems are fit-for-purpose before implementation.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.53

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations strengthen its approach for managing unique service features proposed by suppliers, including by identifying and including these features in executed contractual arrangements.

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

33. The department’s summary response is provided below and its full response is included at Appendix 1.

The department welcomes the audit’s recommendations and the overall positive findings. The department is particularly encouraged by the ANAO’s recognition that the establishment of the Workforce Australia Services Panel was ‘largely effective’, was consistent with the Australian Government’s policy objectives and Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

The department has agreed, in part or full, to all recommendations. In respect of Recommendation 3 in particular, prior to the conclusion of the audit, the department had documented and agreed all Key Tender Representations with current (licensed) Workforce Australia Providers – highlighting our commitment to continuous improvement.

ANAO comment on Department of Employment and Workplace Relations’ summary response

34. As outlined at paragraphs 6, 9, 26 and 27, the ANAO concluded that the design of the procurement process was largely consistent with the Australian Government’s policy objectives (see paragraphs 2.16 to 2.19). While licences were awarded to the providers assessed as representing the most overall value for money, the establishment of the Workforce Australia Services Panel was not informed by an appropriate value for money assessment (see paragraphs 3.58, 3.64 to 3.65, 4.3 to 4.5, and 4.10 to 4.16).

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

1. Background

1.1 The Australian Government has outsourced employment services to largely non-government owned providers since 1998.1 Workforce Australia is the Australian Government’s current employment services program. It commenced on 1 July 2022 and is administered by the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR or the department). It replaced the predecessor program, jobactive, which had been in place since July 2015.

1.2 Jobactive was initially established to operate for five years between July 2015 and June 2020. By April 2019, deeds between DEWR and the jobactive providers were extended for a further two years to June 2022 to, among other things, ‘enable continuation of employment services while the new employment services model [was] trialled.’

1.3 There were around 630,000 job seekers in jobactive as at 29 February 2020, prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.2 This increased to a peak of 1.49 million by 30 September 2020, and by December 2021, had reduced to 895,000. As at August 2023, there were 604,000 job seekers in Workforce Australia employment services.3

1.4 Employment service providers are contracted by DEWR to deliver employment services and support job seekers and employers, including assisting job seekers receiving certain income support payments to manage their mutual obligations requirements.4 Under Workforce Australia, mutual obligations are reflected in a ‘Job Plan’ and involve agreed tasks and activities to increase job readiness, taking account of job seekers’ personal circumstances.5

New Employment Services Model

1.5 Between May 2018 and May 2021, the Australian Government invested funding of over $6 billion across the forward estimates for the delivery of ‘a new approach to employment services that is digitally driven, tailored and flexible.’ Details announced in the context of Federal Budget processes included:

- five announcements between January 2018 and October 2020 relating to the development of ‘Online Employment Services’, commencing with a trial in July 2018. The trial was expanded progressively until online self-servicing was implemented for all ‘job-ready job seekers’ in April 2020.6 In November 2023, the department advised the ANAO that the collective net efficiencies recorded against these measures totalled $1.3 billion;7

- an April 2019 announcement for ‘$249.8 million over five years from 2018–19 (including $25.7 million in capital funding over four years from 2018–19) to pilot key elements of a new employment services model’ in two employment regions;

- an October 2020 announcement of $295.9 million over four years from 2020–21 (including $150.7 million in capital funding) to ‘establish a new digital employment services platform that will be available to all Australians’8;

- an announcement in May 2021 that an efficiency of $860.4 million over four years from 2021–22 would be achieved by transitioning from jobactive to the ‘New Employment Services Model’ (the new model, or NESM) from 1 July 2022.

1.6 In October 2021, the NESM was renamed as ‘Workforce Australia’ and was to introduce two pathways of support for job seekers, comprising:

- Enhanced Services — a network of employment services providers to deliver tailored and intensive case management support to higher-risk job seekers; and

- Online Employment Services — also known as ‘Workforce Australia Online’, for job seekers assessed as lower-risk, considered job ready, and able to self-manage their mutual obligations and job search activities online.9

1.7 The new model was to be a ‘transformational change’ from the previous program. In contrast to jobactive, where all job seekers were referred to the provider network for face-to-face assistance, only higher-risk job seekers would be required to access employment services through a provider under the NESM.10 Net efficiencies from the reduction in face-to-face servicing arrangements were to be ‘reinvested in the employment services system to provide a more intensive, targeted and tailored service for those who need extra help in addressing their barrier to getting a job.’11

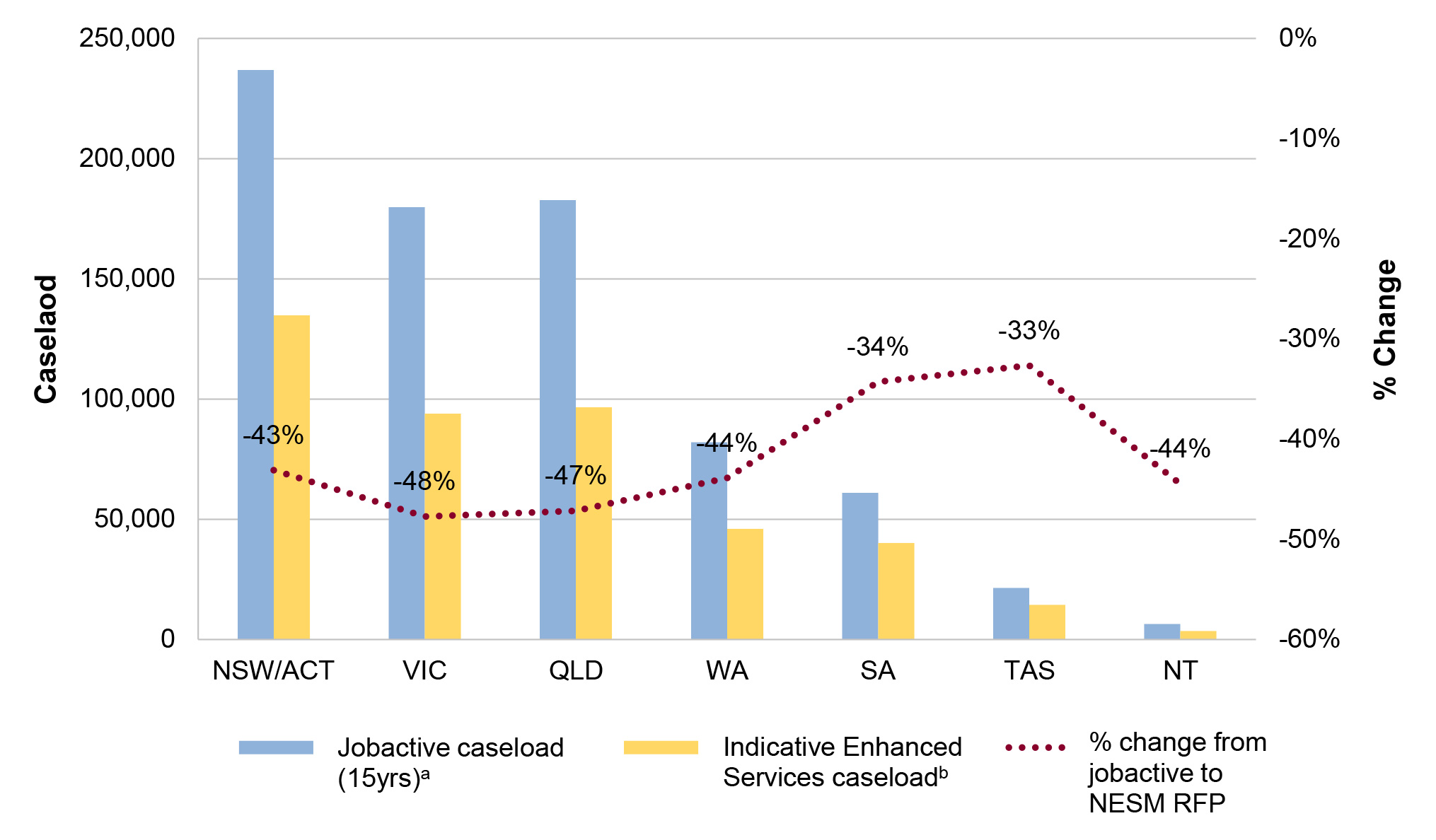

1.8 Development of the NESM commenced in early 2018. Detailed aspects of the new model were developed between 2018 and 2021, which was informed by a ‘New Employment Services Trial’ pilot from July 2019 and a range of financial viability analyses conducted from mid-2020 and early 2021. The department engaged KPMG to undertake these analyses in May 2020 to inform its refinement of the ‘micro policy’ settings for the program and to provide assurance that providers would remain viable under the new model when servicing the smaller pool of job seekers in Enhanced Services. This work was a key input to the design of the NESM procurement process and tender documents (discussed from paragraph 1.10). Figure 1.1 illustrates the reduction of the job seeker caseload between jobactive and the new model.

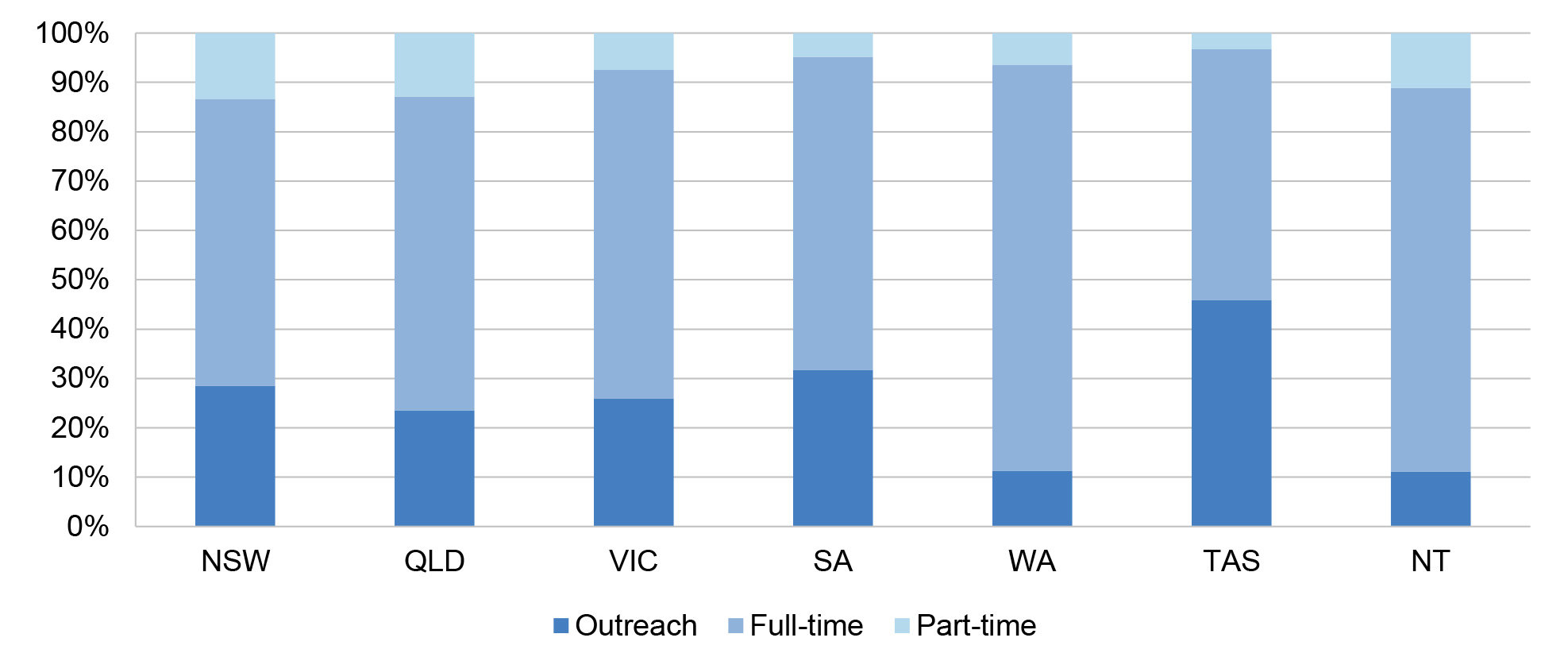

Figure 1.1: Changes in the job seeker caseload between jobactive and Workforce Australia by state and territory

Note a: The jobactive caseload data is taken from Australia Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reporting in June 2020.

Note b: Indicative Enhanced Services caseload numbers were those published in the NESM Request for Proposal.

Source: ANAO analysis of ABS and DEWR records.

Procurement process

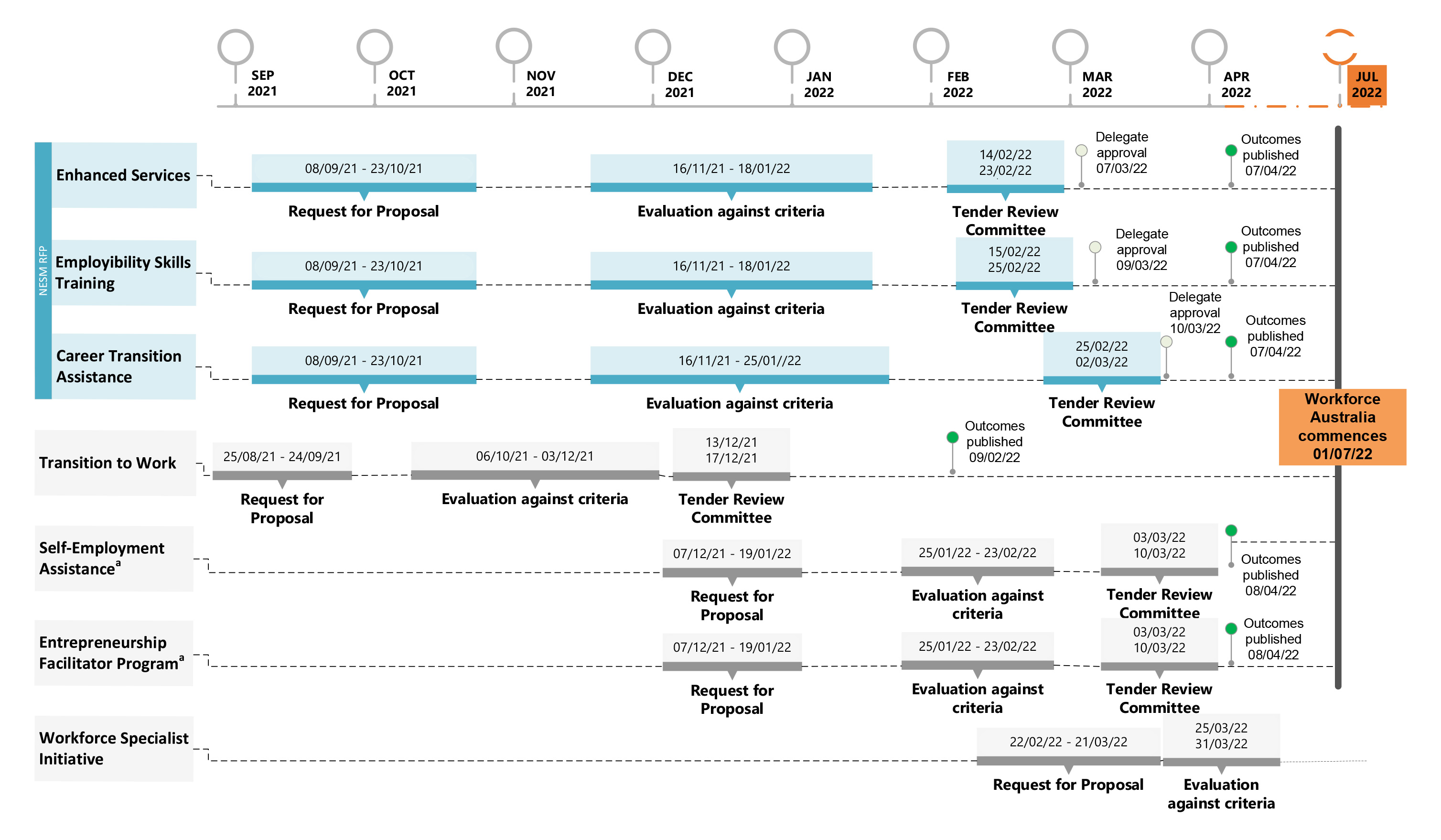

1.9 At least seven procurement processes for a range of employment assistance and related services were conducted either in parallel or in close succession throughout 2021–22. One of these processes was for identifying providers to deliver Enhanced Services under the new program, which was also used to establish the Workforce Australia Services Panel. The panel was established to ‘streamline’ any future procurement processes required over the life of the new program, such as when filling an Enhanced Services provider ‘gap’ in a specific employment region. Figure 1.2 illustrates the timing of these procurements.

Figure 1.2: Timeline of the NESM and other employment services procurements in 2021–22

Note a: Savings announced as part of the 2023–24 Budget process included $22.8 million by ceasing the Entrepreneurship Facilitator Program from 1 July 2023 and $111.6 million by reducing place allocations for the Self-Employment Assistance Small Business Coaching program. See: Australian Government, Budget 2023–24 Budget measures: Budget Paper No. 2, p. 106, available from https://budget.gov.au/content/bp2/download/bp2_2023-24.pdf [accessed 3 October 2023].

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records.

1.10 On 8 September 2021, proposals for the following three ‘service areas’ were invited through a single open tender process:

- Enhanced Services — a range of intensive, individualised and tailored services for vulnerable job seekers delivered by a network of employment service providers.

- Employability Skills Training (EST) — a targeted training service to enhance work readiness through intensive pre-employment training.

- Career Transition Assistance (CTA) – designed to help mature age job seekers aged 45 and over to build their confidence and skills to become more competitive in their local labour market.

1.11 The EST and CTA service areas are support services for job seekers, which were also available under the jobactive program. Under jobactive, providers were able to refer job seekers to these services according to their personal needs. While this remains the case under Workforce Australia, Enhanced Services providers are now subject to a ‘referral cap’ and job seekers in online services can enrol themselves if they are eligible.12

1.12 The relevant information for each service area was provided within the published ‘Request for Proposal for the New Employment Services Model 2022’ (RFP), which included a consolidated request for proposal document, draft deeds or deed of standing offer, and a range of factsheets on program aspects. Proposals for all three services were to be received by 3pm (Canberra time) on 22 October 2021. The assessment processes for each service area were conducted separately but in close succession, with successful providers notified in March 2022.

1.13 Work orders with successful Enhanced Services providers were executed during July 2022. In total, 155 providers submitted 2111 proposals across 51 employment regions. As outlined by Table 1.1, over half of these proposals were for Enhanced Services.

Table 1.1: Tender submissions to the NESM procurement (by service area)

|

Service area |

Provider organisations |

Number of individual proposals |

Number of individual proposals |

|

Enhanced Services |

117 |

1222 |

58% |

|

Employability Skills Training |

76 |

585 |

28% |

|

Career Transition Assistance |

51 |

304 |

14% |

|

Total |

155a |

2111 |

100% |

Note a: Total number of providers does not equal the sum of individual providers as some bid for multiple service areas.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records.

1.14 On 11 March 2022, the department notified 104 providers that they had been appointed to the national panel13, and from those providers, 45 were offered 181 ‘licences’ to deliver Enhanced Services within one or more employment regions.14 Licences were ‘issued’ by executing work orders under a Deed of Standing Offer (DoSO).15 Of the 45 providers invited to sign a work order in March 2022, 43 had provided written acceptances by 13 July 2022. After the commencement of Workforce Australia from 1 July 2022, the panel consisted of 99 providers, inclusive of the 43 that accepted offers under the DoSO.16 The total estimated value of the licences awarded, as reported on AusTender, was $3.27 billion.

Recent reviews and inquiries into employment services

1.15 On 2 August 2022, the House Select Committee on Workforce Australia Employment Services was established to ‘inquire into and report on matters related to Workforce Australia Employment Services’.17 The Committee tabled its Interim Report in ParentsNext in February 2023, and as at mid-November 2023, the Committee was due to table its final report by 30 November 2023.

1.16 On 25 September 2023, the Australian Government released the White Paper on Jobs and Opportunities.18 The White Paper set out the Government’s ‘roadmap’ for the labour market and included eight ‘guiding principles to strengthen employment services in Australia’.19

Previous audits

1.17 Previous ANAO performance audits relating to the department’s administration of the previous employment services program include:

- Auditor-General Report No. 31 2021–22 Jobactive – Integrity of Payments to Employment Service Providers; and

- Auditor-General Report No. 4 2017–18 Jobactive: Design and Monitoring.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.18 This audit was conducted to provide independent assurance to the Parliament on the design and establishment of the panel arrangements for the program, including whether the procurement process conducted was effective and consistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.20

Audit approach

Audit objective and criteria

1.19 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the establishment of the Workforce Australia Services panel.

1.20 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were considered.

- Was the design of the procurement consistent with policy objectives and achieving value with money?

- Was the procurement conducted in accordance with the published process?

- Did the results of the evaluation process appropriately inform the establishment of the panel?

Audit methodology

1.21 The audit methodology included examination and analysis of entity records and meetings with relevant departmental officials and stakeholders.

1.22 As the procurement process was conducted during periods of COVID-19 health restrictions in early 2022, departmental records for the procurement process comprised online meeting recordings of the Tender Review Committee (TRC) deliberations on proposals in each the 51 employment regions. The audit approach included reviewing the recordings for at least 42 of those regions.

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $652,200.

1.24 The team members for this audit were Swatilekha Ahmed, Dr Adam Reddiex, Jay Banpel, Kathryn Longstaff, Jude Lynch, Josh Carruthers, Michelle Page and Amy Willmott.

2. Design and implementation

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the design of the procurement was consistent with policy objectives and achieving value for money.

Conclusion

The design of the procurement process was largely consistent with the Australian Government’s policy objectives for the New Employment Services Model (NESM). Four key ‘transformational’ changes were to be implemented, including a new regulatory licensing framework for employment services through legislative amendments. A contractual licensing model through a procurement process was adopted, rather than the establishment of a legislative regulatory framework. The design was intended to give effect to the underlying policy intent of easier entry and exit of providers from the market through the establishment of a panel of providers. Proposal documentation was made publicly available when the tender process opened for submissions. An appropriate evaluation process was established and probity arrangements commensurate with the risk and scale of the procurement were established. Not all aspects of the probity plan were executed.

Financial viability analysis was undertaken by KPMG in 2020 and 2021 to provide advice to the department on whether providers would be viable under the new policy settings, including operating with a target caseload to staff ratio of 80:1 to provide these more intensive services. The analysis indicated that there remained at least two and up to 12 employment regions that were unlikely to be able to support a single provider under the final policy settings for the new model.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation relating to the engagement of probity experts.

2.1 The Australian Government has outsourced the delivery of employment services since the ‘Job Network’ program was introduced in May 1998. While this model has evolved over time in successor programs, its underlying elements have remained largely unchanged.21

2.2 In November 2017, the Australian Government agreed to pursue ‘fundamental reform’ to improve those services. That reform was to be guided by seven foundational principles, which included a system design that would maximise job seeker and employer engagement; and ensure efficiency and value for money in policy design and service delivery.22 The ANAO examined whether these aspects were reflected in the design of the procurement process.

Were lessons learnt from the previous program used to inform the new design, including any stakeholder input?

Learnings identified through discussion papers and public consultations conducted by the Employment Services Expert Advisory Panel (the expert panel) between January and October 2018 informed the design of the new program. In December 2018, the Australian Government agreed that ‘transformational’ changes from the jobactive program would underpin the NESM, including:

- the implementation of job seeker self-service through a digital services platform;

- more intensive support for the job seekers needing the most help; and

- a ‘licensing framework’ to lower barriers to entry and exit for providers, more effectively drive quality outcomes, and reduce the cost and disruption of procurement processes.

Employment Services Expert Advisory Panel

2.3 To inform the development of future employment services, the Australian Government established an Employment Services Expert Advisory Panel (the expert panel) on 22 January 2018.23 The expert panel’s work was informed through public consultation of over 1400 job seekers, employers, employment services providers and community groups.24 It reported its findings in October 2018 and made 11 recommendations, with key findings including that:

- a new digital approach should be adopted, with capable job seekers allowed to self-serve online and providers able to focus on supporting job seekers needing the most help; and

- a provider licensing framework and improved payment and performance model should be adopted to allow for greater competition and diversity between providers, without compromising market stability.

Licensing arrangements

2.4 A licensing framework for employment services was contemplated by the Productivity Commission in its review of the Job Network in 2002. It noted that competitive tendering is complex and expensive for providers and disruptive to services. It recommended that licensing of providers be adopted to enable free entry into the market by accredited agencies — subject to ongoing assessment of quality.25

2.5 Similarly, the expert panel recommended a ‘managed approach to increasing competition’ in the employment services market by issuing provider licences for a minimum of five years and, ‘at least initially, guaranteed minimum and maximum market shares’. The panel envisaged that:

- entry into the market would be easier, with flexibility in the number of licences available and the timing of their distribution;

- providers would be required to complete a licence application, with that process being simpler and less costly than tender processes; and

- licence extensions would be available for consistently high performing providers and loss of licences before expiry for consistently poor performers.

2.6 The expert panel recommended that the number of licences issued in each of the 51 employment regions be capped, which differed from the Productivity Commission model. This was to ensure an appropriate balance between market sustainability and providers’ capacity to meet job seeker and employer needs. The licensing approach is discussed further at paragraph 2.16.

Senate Education and Employment References Committee inquiry into jobactive

2.7 In August 2018, the Australian Senate referred an inquiry into ‘the appropriateness and effectiveness of the objectives, design, implementation and evaluation of jobactive’ to the Education and Employment References Committee (the committee). The committee’s findings were published in February 2019.26 It found that jobactive was not meeting its intended objectives and, among other things, noted that:

- the program was not providing sufficient or appropriate support for disadvantaged job seekers; and

- the funding model incentivised providers to churn people through short term work, rather than securing longer-term employment.

2.8 The committee made 41 recommendations to improve the employment services system. The Australian Government’s response to the report was tabled on 20 May 2020, which outlined a range of features to be explored as part of a new model, including separate ‘streams’ for job-ready and disadvantaged job seekers, and intensive case management for the job seekers most in need.

Policy intent for the design of the New Employment Services Model

2.9 On 11 December 2018, the Australian Government agreed that a range of fully costed options for the NESM be developed for implementation following the expiry of jobactive contracts on 30 June 2020. Consistent with the expert panel’s recommendations, the following ‘key transformational changes’ from the jobactive model were to underpin the design of the NESM:

- self-servicing through digital services for job-ready job seekers and a digital and data ecosystem that will reduce red tape;

- more intensive support for disadvantaged job seekers;

- more effective, tailored and flexible job seeker activity requirements that maintain mutual obligations; and

- a licensing framework to lower barriers to entry and exit, more effectively drive quality outcomes, and reduce the cost and disruption of procurement processes.

Was the policy intent reflected in the new design, including the procurement approach?

The Australian Government’s policy intent was largely reflected in the design of the new model. Key aspects included: intensive support and case management for disadvantaged job seekers; lowering the consultant to job seeker caseload ratio; and allowing low risk job seekers to self-manage online through a new digital services platform. A point of difference from the expert panel’s envisaged model was the establishment of the NESM through a procurement process rather than a statutory licensing framework. In this respect, the department advised the Minister that greater risks were associated with a ‘statutory licensing model’ and a procurement process could still give effect to the policy objectives. This involved designing a process that would reduce barriers to entry for new, small and/or specialist providers, including by:

- allowing providers to tender for ‘part region’ servicing;

- applying weightings to criteria to lower the importance placed on providers’ past performance, while increasing the importance on local community knowledge and connections; and

- establishing a panel arrangement through a deed of standing offer, with successful providers to be issued a ‘contractual licence’ through executed work orders.

Findings from the New Employment Services Trial (NEST) pilot enabled key policy settings to be tested and refined between July 2020 and September 2021, with changes informing the NESM RFP. Financial viability analysis was conducted throughout the pilot to provide assurance that providers could be viable under the new policy settings, including operating with a target caseload to staff ratio of 80:1. Steps were taken to improve the viability of providers, such as increasing certain outcome payments and the national market share cap. However, the analysis indicated that there remained at least two and up to 12 employment regions that were unlikely to be able to support a single provider under the final policy settings for the new model.

2.10 Following government agreement in December 2018, the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (the department) worked until early February 2019 to develop policy options for the NESM, for consideration in the 2019–20 Budget process.

2.11 The department established six ‘sprint teams’ to focus on refining the options and policy settings for key aspects of the new model.27 On 11 January 2019, the department advised the Minister for Jobs and Industrial Relations (the Minister)28 that:

- the employment services reforms represented significant fiscal and reputational risk, and given the tight timeframes for the April 2019 Federal Budget, the department’s capacity to manage these risks by engaging with stakeholders on the detailed design and implementation of the model was ‘severely’ limited; and

- instead of the full implementation of a new model on 1 July 2020, it recommended that an iterative implementation process for the new model be adopted, consisting of:

- rolling over the existing jobactive contracts; and

- commencing with a pilot of the reforms from July 2019 and a national rollout from July 2021.29

2.12 The Minister’s proposal to government was consistent with this advice. On 5 March 2019, the Australian Government agreed that a fully costed model for the NESM be developed in accordance with the Minister’s preferred option. The model was to be informed by evidence from a pilot in two employment regions: Adelaide South in South Australia (SA) and Mid North Coast in New South Wales (NSW).30 The Minister announced the reform process on 20 March 2019 at a jobactive CEO Forum and provided further details in another announcement on 2 April 2019.

New Employment Services Trial (NEST)

2.13 The New Employment Services Trial (NEST) pilot was implemented in phases between July 2019 and June 2021 to test key design elements including the provider payment framework, ‘points-based activation system’ for mutual obligations, and job seeker registration and referral processes (for both online and face-to-face services). The contractual licensing model and the provider performance framework were not tested as part of the trial.31

2.14 On 2 April 2019, the eight pre-existing jobactive providers in the two pilot regions were invited to submit expressions of interest (EOIs) to participate in the NEST through a limited tender process.32 All eight providers participated in the pilot.

2.15 The final evaluation report covering the period from July 2019 to June 2021 was delivered in November 2022, around four months after Workforce Australia commenced.33 Learnings from the pilot, including analysis undertaken by KPMG (discussed at paragraphs 2.24 to 2.31), informed the refinement of policy settings. This included changes to the proposed provider payment framework and simplification of the new model by removing the ‘Digital Plus’ stream and consolidating the ‘tiers’ of support within Enhanced Services.34

Licensing framework

2.16 The initial NESM program design in July 2019 was largely consistent with the ‘transformational changes’ agreed by government in December 2018. The key point of difference was that the NESM was to be established through a procurement process, rather than through a licensing application process and framework (see paragraphs 2.4 to 2.6). When examining potential options in January 2019, the department recorded that there were two approaches available: ‘statutory licensing’ and ‘contractual licensing’, and also considered whether the number of providers in the market should be capped (each with allocated ‘market share’ percentages) or uncapped. It noted that a:

- [statutory] licencing model would require primary legislation to establish it and is subject to rejection or amendment by Parliament. This creates a risk that a licencing model may not pass Parliament, or that is amended by Parliament, that could result in a model inconsistent with the intent and objectives of the overarching employment services model; … and

- … contractual licencing model is a procurement administered under the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and in practice is not materially different to the current procurement processes used….

2.17 The department’s analysis was that while an uncapped statutory licensing model most closely met the government’s objectives, the ‘risks associated with progressing with this option [were] considered too high.’35 Contractual licensing through a ‘streamlined procurement model’ was identified as the preferred approach and recommended to government in late January 2019.36

2.18 A risk identified in a procurement approach was that it may be seen as disadvantaging small and specialist providers.37 To mitigate this and give effect to the policy objectives, the department noted that there were a number of options available to streamline, simplify and differentiate the upcoming procurement process from previous processes. It further noted that a number of changes could be made to reduce barriers to entry, particularly for small and niche organisations. This included:

- allowing ‘part region’ tendering, to encourage local, regionally/locally focused providers to tender38;

- different tender requirements for generalist/specialists/part region providers; and

- re-weighting of the selection criteria (for example, reducing the weighting for past performance and increasing it for local community connections and feedback).

2.19 These changes were factored into the evaluation criteria for the procurement and are examined further from paragraph 2.45.

National panel and regional sub-panels

2.20 In a panel arrangement, suppliers are appointed to supply goods or services for a set period of time under agreed terms and conditions. Once a panel has been established, an entity may then purchase directly from the panel by approaching one or more suppliers.39 A ‘national panel’ was established through the NESM Request for Proposal (RFP) process to, among other things, streamline the entry and exit of providers in the market and to fill gaps within regions as needed.40

2.21 The RFP required providers to give tailored responses for each employment region they had bid for. Sub-panels were to be established for each of the 51 employment regions. Where providers were found ‘suitable’ for one or more regions, they were to be appointed to the national panel and the sub-panels for those regions.41 The national panel was established for an initial period of six years through a Deed of Standing Offer (DoSO). After that period, panel members may be extended for up to an additional four years at the department’s discretion.

2.22 Successful providers were identified from the sub-panels and offered ‘licences’ for those regions through the execution of work orders under the DoSO.

Provider payment model and financial viability

2.23 The NESM program design was based on the premise that by lowering providers’ caseloads, more intensive and tailored services could be provided to the most disadvantaged job seekers. Under jobactive, the average job seeker to consultant (caseload) ratio was 150:1.42 The NESM policy objective was to achieve a caseload ratio of 80:1.

2.24 The department engaged KPMG in May 2020 to conduct financial viability analysis, based on jobactive and NEST pilot data. While this work was initially due for completion by the end of July 2020, additional analysis was requested by the department. The analysis progressively examined the feasibility of the policy underpinning the NESM — with a focus on assessing the financial viability of providers under the new policy settings — to identify the appropriate number and types of licences for each employment region. In total, three sets of modelling were undertaken by KPMG in August 2020, January 2021 and May 2021.43 The results of these analyses informed the detail included in the RFP.44

August 2020 financial viability analysis

2.25 Between May and June 2020, KPMG conducted interviews with departmental subject matter experts (across seven employment services programs) and engaged with providers directly to source financial and operating data and, where relevant, seek their perspectives and experiences from participating in the NEST. In total, four providers contributed data for the financial viability analysis and eight provided insights during interviews. The department also provided NEST and jobactive caseload and payment data to KPMG.

2.26 Initial findings provided to the department on 13 July 2020 indicated there would be ‘significant viability challenges for providers’ if the current NEST settings were included in the NESM, with 65 per cent of employment regions unable to support a single provider over two years.45 In response to feedback from the department, KPMG drew ‘more deeply on historic jobactive data as an additional input’ to its analysis.46 The updated results were reflected in the final August 2020 ‘New Employment Services Model Financial Viability Analysis’ report (August 2020 KPMG report), which included the following observations.

- Most scenarios are viable over both a three and five year period – … Scenarios with higher commencement numbers, higher caseload to staff ratios, lower fixed cost structures and higher outcome rates tended to increase profitability over three and five years. Scenarios with a combination of negative factors – notably lower caseload, high cost structures and low outcome rates – were loss making over the period examined.47

- Caseload to staff ratios of 80:1 were not viable under any of the scenarios examined – No scenarios examined were viable under the high cost structure assumption. This assumption included caseload to staff ratios of 80:1. However, providers were viable at a ratio of 120:1.

- Jobseeker volumes and cost structures are key factors driving viability – … analysis indicates that, in order of importance, the key drivers of viability are caseload to staff ratios, jobseeker volumes, provider fixed costs and outcome rates. Staff ratios and fixed costs are clearly factors determined by providers.

- Upfront cash flow for providers supports initial viability – In all scenarios examined, providers experience net monthly losses in the first year of operation.

- Market share allocations may need to change compared with jobactive – The scenario analysis suggests that providers are unlikely to be viable based on historic market share allocations and some reduction in provider numbers may be necessary to maintain viability. [Emphasis in original]

2.27 In this latter respect, KPMG noted that ‘[w]hile this could reduce competition within some regions … the department could consider a mixed model where fewer large and medium providers are contracted but competition within a region is maintained through adding a number of smaller, low cost providers.’ This was, in part, to achieve a balance between two competing policy objectives of providing intensive and tailored services to job seekers and increasing job seeker choice of providers within employment regions.

January 2021 analysis on updated provider payment framework

2.28 The department re-engaged KPMG in November 2020 to ‘undertake supplementary financial analysis’ on caseload ratios using updated Treasury forecasts and data. This analysis was to test the impact of changes to provider viability using an updated payment model and examine policy settings that had not been settled at the time of the first analysis.

2.29 The NEST pilot policy settings were adjusted, and supplementary analysis was undertaken by KPMG based on a broader range of fixed cost assumptions for providers, a revised payment model and updated inputs from the department.48 The supplementary analysis was finalised in a January 2021 KPMG report, which outlined that the analysis was undertaken to ‘investigate payment settings which aim to increase the likelihood of provider viability when caseload to staff ratios of 80:1 are applied.’ The market share allocations were not increased and the caseload ratio of 80:1 was maintained (as the intent was to achieve provider viability at that caseload ratio). The range of fixed cost assumptions used for the January 2021 analysis are outlined in Table 2.1.

2.30 The supplementary analysis was finalised in January 2021, finding that a provider operating with a revised payment model and caseload ratio of 80:1 would be ‘viable across a 10-year contract period’, with the new payment structure having a positive impact on viability. It was noted that while there ‘would be months within the first year when losses would be recorded, in aggregate and across the 10-year period, the modelled provider is viable’.

2.31 The department advised government in April 2021 that the provider payment model was critical to the success of the NESM and KPMG’s analysis had found that the revised payment model will support provider viability at caseload ratios of 80:1. The department did not outline that the January 2021 report noted that at least two and up to 12 employment regions could not support a single Enhanced Services provider under the NESM policy settings (as shown in Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Number of viable Enhanced Services providers by region and provider fixed cost base compared with contracted jobactive providers

|

Number of viable providers in region |

Number of contracted jobactive providers |

August 2020 report |

January 2021 report |

||

|

|

|

Caseload 80:1 |

Caseload 80:1 |

||

|

|

|

# of regions based on $2.2m fixed costs |

# of regions based on $0.4m fixed costs |

# of regions based on $2.2m fixed costs |

# of regions based on $2.4m fixed costs |

|

No profitable provider |

0 |

17 |

2 |

10 |

12 |

|

1-2 providers |

2 |

18 |

1 |

13 |

14 |

|

2-3 providers |

7 |

6 |

1 |

11 |

10 |

|

3-4 providers |

15 |

7 |

1 |

6 |

5 |

|

4-5 providers |

9 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

6 |

|

More than 5 providers |

18 |

1 |

43 |

7 |

4 |

|

Total regions |

51 |

51 |

51 |

51 |

51 |

|

Total contracts/licences across regions |

196 |

89 |

772 |

133 |

121 |

Source: ANAO representation of departmental records.

Market share and diversity of providers

2.32 Reflecting that some policy settings were introduced or modified to support smaller providers and encourage more diversity in the market, the published RFP stated that:

- assistance would be provided for eligible small organisations through a new Capacity Building Fund49; and

- the total business share of an organisation licensed to deliver Enhanced Services was not to exceed 20 per cent of the national market (inclusive of related entities).

2.33 In respect to the latter, this represented a doubling of the initially agreed 10 per cent market share cap determined by the department’s procurement interim steering committee in June 2021. This change was made as a result of a request from the Minister in August 2021. The previously agreed market share cap had been communicated to stakeholders and providers through the RFP Exposure Draft in June 2021.

May 2021 analysis of specialist licences

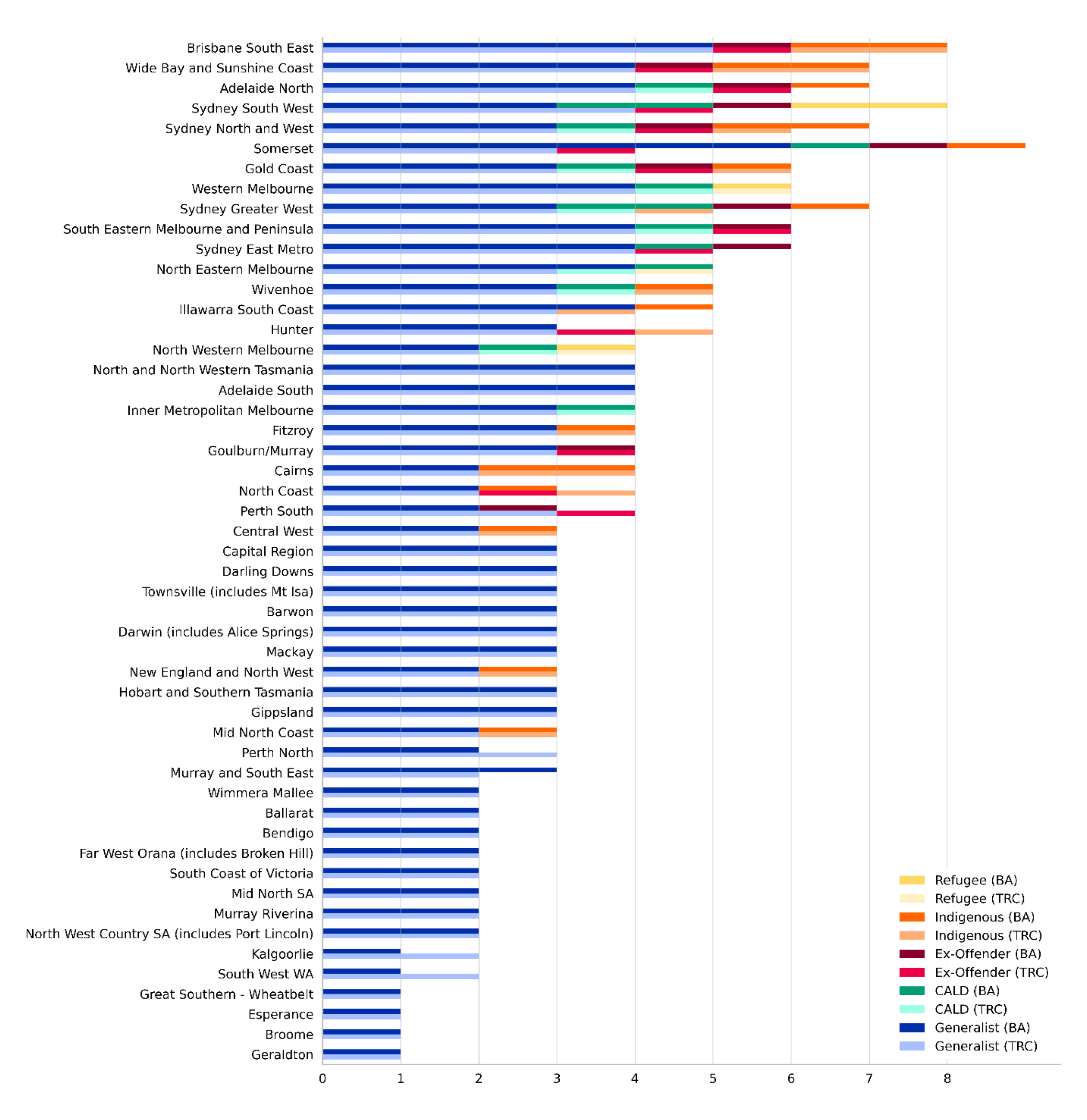

2.34 The RFP outlined that ‘Specialist Enhanced Services’ licences would be allocated in some regions to providers with expertise in supporting refugee, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD), Indigenous or ex-offender job seekers (specialist cohorts). In regions with no specialist services, generalist providers were expected to ensure appropriate support for all job seekers on their caseload.

2.35 The November 2020 work order with KPMG was extended in early April 2021 for additional analysis to identify whether particular job seeker cohorts could be viable in each employment region, and whether specialist licences would have an impact on the viability of generalist providers in those regions.50 The final report was provided to the department on 10 May 2021.

2.36 The analysis indicated that specialist providers were unlikely to be viable in most employment regions. This was based on the assumption that a specialist provider would hold 40 per cent of the market share for the relevant cohort in the region, as this was required for viability. Table 2.2 outlines the findings of that analysis.

Table 2.2: Number of viable specialist cohorts across employment regions

|

Viability assessmenta |

Indigenous |

Persons with disabilities |

Ex-offender |

Refugee |

CALD or refugee |

|

Unlikely |

31 |

19 |

32 |

43 |

33 |

|

Possible |

20 |

26 |

19 |

7 |

10 |

|

Likely |

0 |

5 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

|

Viable |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|

Total region # |

51 |

51 |

51 |

51 |

51 |

Note a: The analysis was based on ‘representative’ provider sizes. For example, a medium to large provider was assumed to have fixed costs of approximately $2.4 million and would therefore need a gross margin of more than this to operate viably.

Source: ANAO representation of departmental records.

2.37 This analysis informed the ‘indicative’ number of licences and average caseload numbers that were included in the NESM RFP for each employment region. The maximum number of licences included in the RFP for each region exceeded the number of licences identified as being viable by KPMG.51 The department’s rationale for suggesting more providers could be viable was ‘promoting job seeker choice and market diversity.’52 This resulted in the RFP stating that between one and three licences could be awarded in 12 regions identified by KPMG as unlikely to be able to support a single provider (see Table 2.1).

Public release of financial viability reports

2.38 The department kept the Minister progressively informed of KPMG’s findings and sought legal advice on at least three occasions between September 2020 and May 2021 regarding its obligations for the public release of the financial viability reports.53 The advice sought was in respect of the department’s obligations under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act) and deeds with the providers participating in the KPMG analysis.

2.39 Following a request from the Minister, the department made arrangements in early August 2021 for all three KPMG reports to be provided to government, to inform the government’s policy considerations. As outlined at paragraph 2.40, Australian Government policy approval for the final NESM design was provided on 11 May 2021. In response to ANAO queries in late September 2023, the department advised that it ‘has not had an FOI request for the release of these reports so further consideration has not been required’ with respect to their public release. The department advised that ‘[t]o better support tenderer’s response to the NESM [RFP], the department provided a summary of the findings from the KPMG report as well as the assumptions that underpinned the KPMG analysis’ as attachments to the RFP exposure draft.

Final policy approval

2.40 Policy approval for the final NESM design was provided by the Australian Government on 11 May 2021, with remaining details to be finalised via correspondence between the Minister and the Prime Minister. Details finalised by correspondence included: the Enhanced Services Provider Performance Framework; final Enhanced Services provider payment model; and Employability Skills Training (EST) payment model adjustment.

2.41 Letters were exchanged between the Minister and the Prime Minister on 23 August 2021 and 6 September 2021, respectively. The Prime Minister noted the final details and agreed the proposed changes, with costs to be agreed with the Department of Finance (Finance).54 Finance’s agreement was received on 13 September 2021. The RFP was released on 8 September 2021.55

Was request for proposal documentation made publicly available, including appropriate evaluation criteria?

The RFP documentation was made publicly available when the tender process opened for submissions on 8 September 2021. Three weighted evaluation criteria and 18 sub-criteria questions were included, with each criterion comprising between four and nine sub-criteria questions. While not identified in the RFP, criteria weightings were evenly distributed across the 18 questions.

2.42 In accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs), the department published the NESM procurement on the AusTender website on 8 September 2021. Potential respondents were invited to submit proposals across three ‘service areas’ under the NESM. Multiple responses were required for those bidding to deliver more than one service and/or in more than one of the 51 employment regions. Proposals were to be tailored to address the local needs of each region and received on or by 22 October 2021. The three service areas were:

- Enhanced Services — a range of intensive, individualised and tailored employment services for vulnerable job seekers delivered by generalist and specialist providers.56 The procurement process for Enhanced Services was used to establish the ‘Workforce Australia National Panel’.

- Employability Skills Training (EST) — a targeted training service to enhance work readiness by providing intensive pre-employment training.

- Career Transition Assistance (CTA) — designed to help mature age job seekers aged 45 and over to become more competitive in their local labour market.

2.43 The relevant information for each service area was included in the ‘Request for Proposal for the New Employment Services Model 2022’ (RFP), which was available on the department’s website and on AusTender. In addition to the RFP document, the approach to market materials included a range of other supporting attachments, such as frequently asked questions (FAQs) and information sheets.

2.44 Generally, where tender documentation is amended after it has been released, addenda are published to ensure all potential respondents are made aware of any additional information and clarifications. The NESM Probity Plan required the external probity adviser to be consulted prior to addenda being issued. Eight addenda were published on the department’s website between 15 September and 18 October 2021, with majority for the release of FAQs. One addendum was reviewed by the probity adviser prior to being issued.57

Published evaluation criteria

2.45 Relevant evaluation criteria should be included in request documentation to enable the proper identification, assessment and comparison of submissions on a fair, common and appropriately transparent basis.58 Request documentation must include a complete description of the evaluation criteria to be used when assessing submissions and, if applicable, the relative importance of those criteria.59

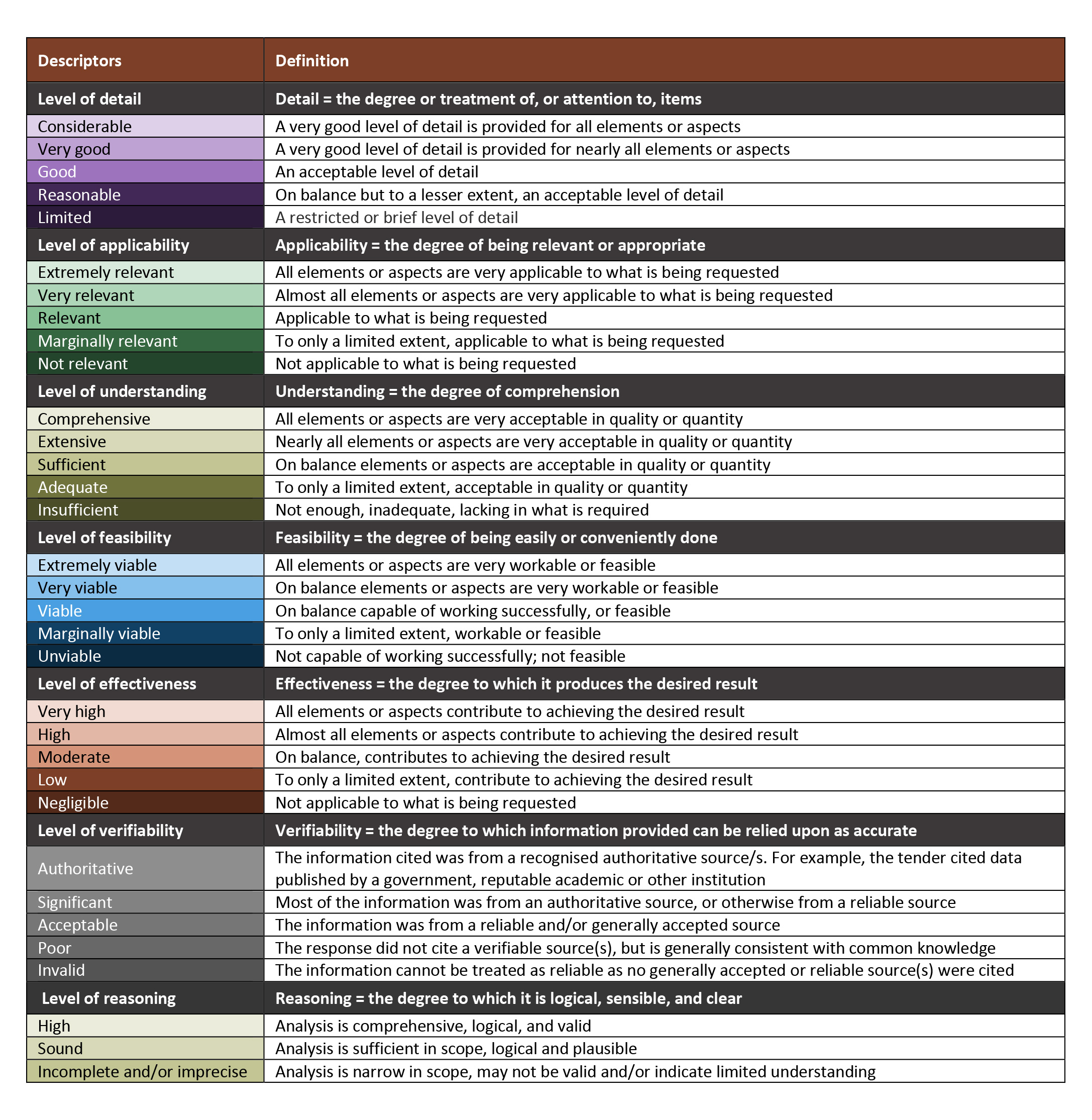

2.46 The selection criteria were grouped into three ‘areas of capability’ in the RFP. Respondents were required to address the first criterion only once, irrespective of the number of services and regions being bid for. Tailored responses for the other two criteria were required for each service and/or employment region being bid for. The selection criteria are outlined in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: NESM selection criteria and sub-criteria questions (and respective weightings)

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records.

Evaluation criteria weightings

2.47 As illustrated by Figure 2.1, each of the three high-level criteria comprised between four and nine sub-criteria questions.

2.48 The qualitative rating scale to be used for the NESM was developed throughout September 2021 and programmed into the IT system used to assess proposals — the Procurement and Licence Management System (PaLMS).60 These qualitative ratings, or ‘evaluation descriptors’, were mapped to numerical values in PaLMS, enabling assessment results to be calculated and orders of merit to be produced. ANAO review of PaLMS identified that:

- the questions were of equal value and importance in the calculation of the overarching criteria scores, as sub-criteria weightings were evenly distributed across the relevant questions; and

- between two and four evaluation descriptors were to be selected for the assessment against each question.

Evaluation component descriptors

2.49 The NESM Assessment Guide, approved on 5 November 2021, was a key reference document for staff conducting assessments against the evaluation criteria.61 It explained that:

EDs [evaluation descriptors] are specific indicators used to rate aspects of the Respondent’s submission against the selection criterion questions. Assessors must consider the criterion question responses and select the relevant ED as they analyse how and to what degree the Respondent’s response supports its claims against the selection criterion.

2.50 The number of aspects, or ‘evaluation component descriptor elements’, to be assessed for each selection criterion question comprised between two and four of the seven elements listed in Table 2.3. Appendix 3 provides further detail, including the combination of elements adopted for each criterion and the respective spread of weightings.

2.51 User acceptance testing (UAT) for the PaLMS was conducted over a two-week period between late July and early August 2021, after delays caused by the IT build and competing priorities across multiple concurrent procurements. The combination of evaluation descriptors to be used for the NESM procurement was determined in parallel with the PaLMS platform build and finalised after the UAT period, on 12 October 2021. Therefore, the department’s ability to fix any system issues or analyse any unintended effects on the assessment process or outcomes was limited.

Table 2.3: Distribution of selection criteria weightings across the evaluation component descriptor elements adopted for the Enhanced Services criteria

|

Evaluation component descriptor element |

Criterion 1 Organisational capability |

Criterion 2 Tailored services capability |

Criterion 3 Local knowledge and connections |

Total |

||||

|

|

#a |

% |

#a |

% |

#a |

% |

# |

% |

|

Level of detail |

8 |

7% |

5 |

11% |

4 |

10% |

17 |

28% |

|

Level of effectiveness |

5 |

4% |

5 |

11% |

4 |

10% |

14 |

25% |

|

Level of verifiability |

3 |

3% |

4 |

8% |

4 |

10% |

11 |

21% |

|

Level of understanding |

3 |

2% |

3 |

6% |

3 |

8% |

9 |

16% |

|

Level of applicability |

1 |

1% |

2 |

5% |

– |

– |

3 |

5% |

|

Level of feasibility |

2 |

1% |

– |

– |

1 |

3% |

3 |

4% |

|

Level of reasoning |

1 |

1% |

– |

– |

– |

– |

1 |

1% |

|

Total |

23 |

20% |

19 |

40% |

16 |

40% |

58 |

100% |

Note a: These columns identify the number of times this ‘evaluation component descriptor element’ was used across the sub-criteria questions for this selection criterion. Appendix 3 provides further details.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records.

Providers with previous experience with the department

2.52 Respondents were to provide information on their ‘demonstrated performance’ under sub-criteria 1.8 and 1.9. Consistent with departmental advice in early 2019, these sub-criteria represented 4.45 per cent of the total score. In contrast, the equivalent criteria for the 2014 jobactive procurement was 30 per cent of the total score. This shift in approach for the NESM was adopted to reduce barriers to entry, particularly for small or new providers and alleviate administrative burden (see paragraph 2.18). Guidance in the RFP stated that:

- for existing jobactive providers — ‘the department will use current performance and other quantitative data held by the department. Existing Providers will have the option to NOT provide additional information in response to this question’ [emphasis in original]; and

- respondents not contracted by the department — ‘should ensure they describe current or past performance in delivering similar services for another organisation(s) and/or different services targeted to similar Participants. These Respondents must provide details of referees who can verify the Respondent’s specific claims.’

2.53 The implications of this approach during the assessment process are discussed from paragraph 3.40.

Was an appropriate evaluation process established and supported by appropriate guidance?

An appropriate evaluation process was established, with a high-level overview of that process included in the published RFP. Limited information on the evaluation process was otherwise provided. Key internal guidance to support the evaluation process was not timely. This guidance was to be included in the ‘NESM Purchasing Plan’, which required Delegate approval before the RFP closing date and opening of the tender box. While the Delegate’s approval was obtained, the required contents — including the NESM Business Allocation Guideline and the NESM Assessment Guide — were not included in the approved plan. This guidance was developed later, in parallel with the assessment process throughout November and December 2021, and approved by the Chair of the Tender Review Committee (TRC), rather than the Delegate.