Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Establishment and Administration of the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the establishment of the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority and the effectiveness of its regulatory function.

Summary

Introduction

1. The supply of energy is a major contributor to continuing global economic growth, with a key measure of energy supply being the availability of petroleum in the form of oil and gas. The process of extracting petroleum from under water or land involves exploration, drilling, construction, production and decommissioning phases. Petroleum projects are often undertaken in remote and challenging environments, in deep water involving high pressure and high temperature conditions. These projects are high cost and involve considerable commercial risks for petroleum companies, as well as risks to the safety of employees and the natural environment. Recent disasters in the world’s petroleum fields, such as the Montara and Macondo incidents, emphasise the need for effective regulatory oversight.1

2. Australia has a comparatively small petroleum industry, contributing half a per cent of the world’s total production of crude oil in 2012. The industry is nonetheless significant in domestic terms. The Australian petroleum industry was estimated to have made a direct and indirect economic contribution of $28.3 billion in 2011, or about two per cent of total market value of all goods and services produced in Australia.2

3. While acknowledging the economic returns from the petroleum industry, governments have also recognised the importance of an effective regulatory system to support safe and environmentally responsible activity. Key issues for the regulation of the offshore petroleum industry arise from the age of facilities, maturity of operators, use of new technologies, and workforce competency within a rapidly changing industry, all of which contribute to varying types and levels of risk.

Australian regulatory framework

4. Offshore petroleum industry regulation in Australia has evolved over time, largely in response to reviews of major incidents in Australia and overseas. Historically, regulatory functions were undertaken by the state and Northern Territory Government authorities.3 In January 2005, responsibility for offshore occupational health and safety (OHS) regulation was consolidated into the National Offshore Petroleum Safety Authority (NOPSA), established by amendments to the Petroleum (Submerged Lands) Act 1967.

5. Following the release of two offshore petroleum reports4, in August 2009, the then Minister for Resources and Energy announced an intention to expand the regulator’s responsibilities to include well integrity. The Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 (OPGGS Act) was amended in November 2010 to give NOPSA responsibility for non-OHS structural integrity of facilities (including pipelines), wells and well-related equipment.

6. The Montara Commission of Inquiry (the Inquiry) provided the stimulus for further reforms to offshore petroleum regulation. The report of the Inquiry contained 100 findings and 105 recommendations.5 A key recommendation related to the establishment of a single, independent regulatory body responsible for safety, well integrity and environmental management and to consolidate functions of the state and Northern Territory authorities.

7. On 24 November 2010, the then Minister for Resources and Energy tabled the Report of the Montara Commission of Inquiry and the draft Government response, and announced the Government’s intention to establish the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA) as the national regulator for safety, well integrity and environmental management.6 The establishment of NOPSEMA was legislated following amendments to the OPGGS Act, which were passed by the Parliament on 15 September 2011. The new legislative framework provided for the:

- regulation of petroleum exploration and extraction activities by NOPSEMA;

- oversight of NOPSEMA by an Advisory Board;

- granting of titles to the rights for petroleum exploration in Commonwealth waters to a Joint Authority7; and

- petroleum titles administration by the National Offshore Petroleum Titles Administrator (NOPTA).

National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority

8. NOPSEMA’s mission is to ‘independently and professionally regulate offshore safety, well integrity and environmental management’, in pursuit of its vision of ‘safe and environmentally responsible Australian offshore petroleum and greenhouse gas storage industries’.8 In 2013, NOPSEMA was responsible for regulating 29 operators of 149 facilities9, 28 titleholders of 121 wells and 42 environmental management activity operators of 129 activities.10

9. NOPSEMA’s regulatory functions relating to safety, integrity and environmental management activities include:

- developing and implementing effective monitoring and enforcement strategies to secure compliance with obligations under the Act and the regulations;

- investigating accidents, occurrences and circumstances in offshore petroleum operations;

- reporting, as appropriate, to the responsible Commonwealth Minister, and to state and Northern Territory Petroleum Ministers on those investigations;

- advising persons, either on its own initiative or on request, on matters relating to offshore petroleum operations; and

- cooperating with NOPTA, other Commonwealth agencies or authorities having functions relating to regulated operations, and state and Northern Territory agencies having functions relating to regulated operations.

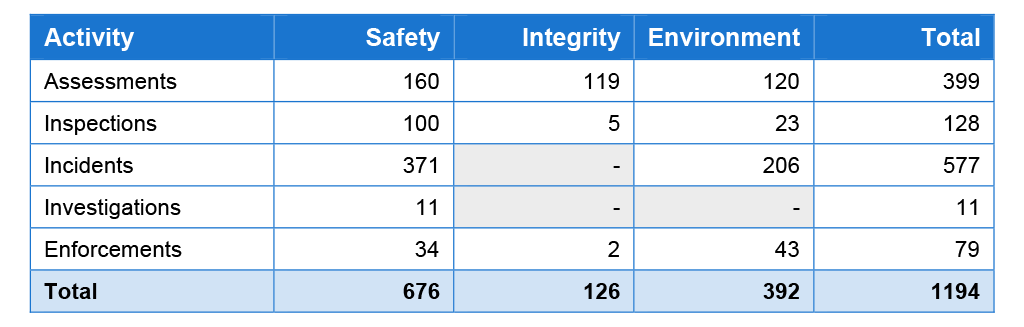

10. The safety, integrity and environmental management regulatory activities undertaken by NOPSEMA in 2013 are summarised in Table S 1.

Table S.1: Summary of NOPSEMA regulatory activities 2013

Source: NOPSEMA.

11. NOPSEMA administers an objective regulatory regime, which sets principles and outcomes for industry rather than standards. The onus is on the operator to identify and evaluate their risks and demonstrate safe, effective and fit-for-purpose practices, that reduce those risks to as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP).11 This approach has applied to operators in Commonwealth waters since 1996. Australia adopted an objective regime for offshore petroleum regulation following the findings of Lord Cullen’s public inquiry into the Piper Alpha disaster of 1988 in the North Sea, which was commissioned by the British Government. The principles or goals-based objective regulatory regime can be contrasted against prescriptive regimes that prescribe requirements and standards for regulated entities to meet.

12. Under the regulatory regime, NOPSEMA is required to provide advice and guidance to operators in relation to regulatory requirements12, assess whether the measures proposed by the operator are appropriate in its permissioning documents13 and, where accepted, monitor and enforce the operator’s compliance with those measures. In delivering its regulatory functions, NOPSEMA must balance the risks posed to safety and the environment with the regulatory burden placed on petroleum operators.

13. NOPSEMA’s petroleum industry stakeholders include Australian Government departments, State and Northern Territory regulators, industry representative bodies and workforce representative groups. The Department of Industry is the primary Australian Government department with oversight of policy and legislation on the exploration and development of petroleum resources.14 Australian Government regulators include the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) and the Department of the Environment.

Administrative arrangements

14. NOPSEMA’s head office is in Perth in close proximity to the majority of regulated petroleum activity adjacent to the coast of Western Australia. Of the 112 total staff employed by NOPSEMA in December 2013, 106 staff were based in Perth. The remaining six staff were based in Melbourne in proximity to the regulated entities located on the Otway and Gippsland Basins in Victoria.

15. NOPSEMA is funded by industry on a cost recovery basis under the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Regulatory Levies) Act 2003. The system of levies covers regulatory activities, including the assessment of safety cases, well operations management plans and environment plans, and the conduct of investigations. In the 2012–13 financial year, $24.5 million in levies was received by NOPSEMA. Total revenue, including revenue from government to fund capital and operating costs arising from the establishment of NOPSEMA, was $28.6 million.15

16. As required by the OPGGS Act, a NOPSEMA Advisory Board has been established to provide advice and strategic guidance to the Chief Executive Officer, the responsible Commonwealth Minister (currently the Minister for Industry) and state and Northern Territory Petroleum Ministers who are members of the Standing Council on Energy and Resources (SCER).16 NOPSEMA is also required to report, as appropriate, to the responsible Commonwealth Minister and members of SCER on investigations.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

17. The objective of the audit was to assess the establishment of the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority and the effectiveness of its regulatory function.

18. To form a conclusion against this audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- an appropriate governance framework to support effective regulation was established;

- compliance risk was adequately assessed;

- a compliance program to effectively communicate regulatory requirements to the petroleum industry and to monitor compliance with regulatory obligations was implemented; and

- arrangements to effectively manage non-compliance were in place.

19. The audit focuses on NOPSEMA’s administration of regulation within the legislative framework in place to mid-2013. It is intended that this audit complements, rather than duplicates, the statutory triennial reviews of the operational effectiveness of NOPSEMA.17 The audit did not assess the operation of NOPSA, NOPSEMA’s administration of the most recent series of legislative amendments,18 and the processes for the setting of levies.

Overall conclusion

20. The National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA) was established in January 2012 as part of the Australian Government’s response to Australia’s most significant offshore petroleum incident, the Montara wellhead blowout in the Timor Sea in 2009. The new regulator continued the existing offshore safety role of its predecessor, the National Offshore Petroleum Safety Authority (NOPSA), consolidated the oversight of well integrity and incorporated the new function of environmental management, previously regulated by the states and the Northern Territory.

21. NOPSEMA’s regulatory activities include providing advice and guidance to operators in relation to regulatory requirements, assessing whether the measures proposed by operators in their permissioning documents19 are appropriate and, monitoring and enforcing operators’ compliance with the measures outlined in the permissioning documents after they have been accepted by the Authority. The Authority has regulatory responsibility for around 400 facilities, wells and petroleum activities and in 2013, it conducted a total of 399 assessments, 128 inspections, 14 investigations and completed 79 enforcement actions across its functions of safety, well integrity and environmental management.

22. Overall, NOPSEMA has appropriately integrated administrative arrangements for the new function of environmental management and has established a sound framework for the regulation of the offshore petroleum industry. There are, however, elements of NOPSEMA’s governance arrangements and aspects of its administration of its regulatory functions that require further strengthening.

23. In relation to governance arrangements, NOPSEMA’s identification and management of business risks is still maturing and would be enhanced by more clearly defining its business risks, better aligning the mitigation strategies designed to address these risks, and developing mitigating strategies for all identified risks. There is also scope for NOPSEMA to improve its performance monitoring and reporting arrangements. The Authority does not currently report against the key performance indicators (KPIs) included in its Portfolio Budget Statements to internal and external stakeholders, while supplementary performance information published by the Authority provides limited insights into the extent to which its objectives are being achieved. The current KPIs are predominantly focused on activities and legislative compliance rather than regulatory performance. Reporting against relevant, reliable and complete KPIs would enable NOPSEMA to better demonstrate the extent to which it is achieving its regulatory objectives.

24. In undertaking its regulatory functions, NOPSEMA’s planning of well integrity and environmental inspections appropriately takes into account the compliance risks posed by individual wells and activities. This approach supports a targeted allocation of regulatory effort to the areas of greatest compliance risk. In contrast, the Authority’s planning of safety inspections is not underpinned by a similar assessment of the safety record and risks posed by each facility. Rather, the frequency of safety inspections is guided by a policy of inspecting each normally attended facility twice each year.20 The planning of its safety inspection program having regard to the risk profile of individual facilities would enable NOPSEMA to prioritise its regulatory activities and more effectively deploy its compliance resources. An assessment of relevant risk factors, including but not limited to past performance and previous incidents as well as future risk exposure, would help to direct greater regulatory coverage towards operators posing the most significant risks and potentially reduce the regulatory burden and costs on compliant operators.

25. Monitoring and compliance activities are delivered through NOPSEMA’s program of planned inspections which are generally implemented in line with core policies and procedures. At each inspection the Authority makes recommendations to operators to encourage better practice or as a preliminary step towards enforcement action. While operators are not compelled to implement the recommendations arising from inspection activities, NOPSEMA reviews the status of previous recommendations at subsequent inspections. Given the regulatory effort required to monitor the implementation of over 1400 recommendations made each year, there would be merit in NOPSEMA focusing its inspection recommendations on matters related to compliance and prioritising those recommendations for operators. Aspects of better practice can be separately communicated to operators in each inspection report. Consideration should also be given to taking enforcement action where compliance related recommendations are not implemented within agreed timeframes. Such an approach would send a clear message to operators on the priority matters for attention and enable the Authority to better manage non-compliance, while potentially reducing the regulatory burden on compliant operators.

26. The ANAO has made three recommendations directed at further strengthening NOPSEMA’s performance of its regulatory activities, focusing on: enhancing aspects of existing governance arrangements; developing risk profiles to inform safety inspection planning; and focusing inspection recommendations on matters related to compliance while addressing better practice aspects in inspection reports.

Key findings by chapter

Establishing and governing NOPSEMA (Chapter 2)

27. NOPSEMA commenced operations in January 2012, building on NOPSA’s existing governance framework. This framework included executive management oversight arrangements for the Authority, including the establishment of the executive leadership team, and an advisory board to provide advice to both the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Authority and the Commonwealth Minister. The Authority did, however, operate without the independent oversight of an Audit Committee until December 2013, as required by the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997.21

28. The Authority implemented appropriate arrangements to incorporate the new function of environmental management, which was previously regulated by the states and the Northern Territory Designated Authorities (DAs), into its governance arrangements within a limited timeframe (between September and December 2011). This new responsibility was in addition to the ‘non-OHS structural integrity’ function that was legislated in late 2010 and assigned to the Authority in April 2011, replacing DAs with the Authority as the regulator of well integrity in Commonwealth waters. NOPSEMA recognises that further work is required to promote a common approach to regulation across its three regulatory functions.

29. In the early months of implementing environmental management regulation, an expectation gap emerged between NOPSEMA and industry in relation to the regulatory requirements for environment plans (EPs). NOPSEMA considered that most of the new EPs did not meet the acceptance criteria as specified in the OPGGSA (Environmental) Regulations 2009.22 Operators concerns included a lack of clarity of regulatory requirements, that approval of EPs was withheld on trivial grounds and that the Authority had been inconsistent in its assessments. In response, NOPSEMA has directed additional effort towards communicating the regulatory requirements and its assessment procedures for environmental management.

30. NOPSEMA has in place an appropriate system of executive management oversight to support the administration of corporate and regulatory activities. However, its identification and management of business risks, while maturing, requires further attention. There is scope for NOPSEMA to more clearly define and link identified business risks with appropriate mitigation strategies and for these to be regularly monitored. Key areas of risk exposure include the management of conflicts of interest and fraud. Although NOPSEMA considered the risk of fraud to be integrated within risk management processes, evidence of integration was limited and was not underpinned with a current fraud control plan or fraud awareness training for new staff. Similarly, although NOPSEMA requires staff to declare real or potential conflicts of interest, these declarations were not retained for all staff and did not include other relevant information, such as family or other relationships that may pose a conflict of interest.

31. Whilst acknowledging the challenges in setting performance indicators for the regulation of the offshore petroleum industry, there is scope for NOPSEMA to improve its performance monitoring and reporting arrangements. The Authority does not currently report against the KPIs included in its Portfolio Budget Statements to internal and external stakeholders. Other published performance information, such as the Annual offshore performance report, provides limited insights into the extent to which NOPSEMA is achieving its regulatory objectives. The current KPIs are predominantly focused on activities and legislative compliance rather than regulatory performance.

Assessing compliance risk (Chapter 3)

32. NOPSEMA uses regulatory intelligence to assess compliance risk and plan individual compliance activities. Its analysis of the performance of operators, the inherent risks associated with activities and other factors, is principally based on the information held within its regulatory management system (RMS). NOPSEMA’s intelligence capability could be strengthened by refining its guidance to staff on the collection of regulatory information and enhancing the mechanisms used to store and share intelligence collected by the Authority.

33. The regulatory risks posed by individual wells and environmental activities are appropriately assessed, which supports a targeted allocation of regulatory effort. In contrast, NOPSEMA currently inspects normally attended facilities twice a year and unattended facilities once every two or four years. There would be merit in NOPSEMA adopting a risk-based approach (similar to well integrity and environmental management) to determine its safety inspection program for normally attended facilities to help ensure that regulatory effort is directed towards those facilities with highest regulatory risk. The reduced regulatory impact of fewer inspections may serve as an incentive for compliant operators, as well as enabling greater resources to be directed towards areas of most significant risk, while maintaining a minimum frequency of inspections.

Monitoring compliance (Chapter 4)

34. NOPSEMA encourages voluntary compliance through its inspection program and by publishing a broad range of guidance material. Workshops are also conducted with industry participants to communicate regulatory requirements. This ongoing, as well as, targeted engagement with industry assists NOPSEMA to ensure that its guidance material remains relevant.

35. NOPSEMA assesses permissioning documents to determine whether the operator has considered all practicable risk reduction measures for the particular facility, activity or well under consideration.23 Generally, the assessment activities undertaken by NOPSEMA were appropriately documented. Assessment processes did, however, result in a number of requests for further information or resubmissions from operators. Of the 113 assessments sampled by the ANAO, NOPSEMA requested further information or resubmissions for 51 per cent of safety assessments, 42 per cent of well integrity assessments and 88 per cent of environmental plan assessments. As any delays in assessments can impose significant costs on operators, it is important to clearly communicate requirements to operators during the assessment process. The duration of the environmental management assessment process was a particular concern of operators, along with lack of clarity in communicating regulatory requirements. The number of resubmissions and the feedback received indicates scope for refining the guidance provided in relation to the environmental management function.

36. NOPSEMA conducts inspections to monitor and promote compliance with regulatory requirements. The inspections are generally implemented in line with the established compliance program and procedures, with inspections including engagement with the offshore workforce employed by operators where possible. There is, however, scope to review target timeframes for inspection milestones, such as the finalisation of inspection reports. Of the 25 safety inspections sampled by the ANAO, inspection reports were issued, on average 43 days following the inspections, more than double the 20-day target.

37. In 2013, NOPSEMA conducted a total of 128 inspections, of 152 facilities, wells and environmental activities and made a total of 1537 recommendations to promote compliance, outline good practice and as a preliminary step towards enforcement. Although operators are not compelled to implement these recommendations, NOPSEMA reviews the implementation of previous recommendations at subsequent inspections. Given the effort required to monitor the implementation of over 1400 recommendations made each year, there would be merit in NOPSEMA focusing its recommendations on matters related to compliance with regulatory requirements, while continuing to promote good practice within the industry.24 This approach would enable NOPSEMA to focus its recommendations on the matters of greatest priority that may warrant the consideration of enforcement action if not implemented within the agreed timeframe.

Responding to incidents (Chapter 5)

38. Operators are required to notify NOPSEMA of accidents, dangerous occurrences and environmental incidents as soon as practicable after the event. To enable the Authority to monitor the implementation of remedial measures, operators are also required to provide an initial report within three days and, for safety incidents, a root cause report within 30 days. While NOPSEMA has established appropriate procedures for the consideration of incident notifications, there is scope to improve the administration of those procedures through more timely consideration of environmental incident notifications.

39. Once an incident notification and report has been considered, NOPSEMA may initiate an investigation depending on the severity of the incident or the adequacy of the operator’s proposed response. The Authority has established over 30 policies, standard operating procedures, work instructions, forms and templates to guide the conduct of its investigations. NOPSEMA’s policies and procedures require the preparation of an investigation plan, the use of a running sheet to manage the investigation and the completion of a lessons learnt review. Of the 13 sampled investigations, eight included an investigation plan, 11 were managed using running sheets and none undertook a lessons learnt review.

40. Where an offence has been identified and prosecution is determined as the appropriate form of enforcement action, NOPSEMA is required to prepare a brief of evidence for consideration by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP). Of the seven finalised briefs prepared between 2005 and 2013, two have resulted in successful prosecutions. The most recent finalised brief of evidence was for the prosecution of PTTEP Australia Pty Ltd in relation to the Montara wellhead blowout.25 However, more than four years after the incident, NOPSEMA has not concluded its review of the investigation and agreed on a consolidated set of revised procedures. NOPSEMA has, nonetheless, advised the ANAO of improvements to its investigation processes following the Montara investigation.

Enforcing compliance (Chapter 6)

41. NOPSEMA has adopted a graduated enforcement model, with actions including improvement notices directing an operator to take certain action, and prohibition notices requiring immediate cessation of an activity. The Authority has procedures in place to help ensure that the enforcement action in relation to safety regulations is graduated in line with risk. NOPSEMA informed the ANAO that its guidance in response to safety non-compliance is used to inform the consideration of enforcement action relating to well integrity and environmental management functions. NOPSEMA decided not to update its guidance material on enforcement to take account of these functions until proposed legislated changes are enacted giving the Authority expanded enforcement powers.

42. The ANAO’s analysis of the 58 sampled enforcement cases found that the rationale for enforcement decisions was recorded in relevant supporting documentation. Furthermore, NOPSEMA’s implementation of enforcement actions has been proportionate and timely. However, there is scope for NOPSEMA to review its procedures for ensuring that operators return to compliance in a timely manner. Of the 26 safety improvement notices sampled, seven operators were granted extensions and, in 10 cases, the required action was implemented after the original or extended timeframe.

Summary of agency response

43. NOPSEMA’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, with the full response at Appendix 1.

NOPSEMA welcomes the conclusion of the ANAO's Performance Audit that had the objective ‘to assess the establishment of the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority and the effectiveness of its regulatory function’.26

As noted in the Report, this Audit was executed in addition to the legislated operational effectiveness reviews of NOPSEMA which are conducted every 3 years.27 These Triennial Reviews are conducted by panels of experts with petroleum, industry or regulatory, backgrounds. The audit officers from the ANAO did not have such experience and may have found it challenging to comprehend the nature of regulation required in a performance based regulatory regime for the high hazard offshore petroleum industry.

Nevertheless, the audit has been extensive. Over a period exceeding 12 months, the Audit has been informed by approximately 190 requests for information, the review of nearly 4000 of NOPSEMA's regulatory records and an examination of NOPSEMA's personnel files. It has consumed substantial resources from both the ANAO and NOPSEMA.

While the Report does not directly provide an overall conclusion in line with the above audit objective, NOPSEMA notes the Report's summary statement ‘Overall, NOPSEMA has appropriately integrated administrative arrangements for the new function of environmental management and has established a sound framework for the regulation of the offshore petroleum industry’.

This summary statement is similar to that made in the Report of the Second Triennial Review of the Operational Effectiveness of the National Offshore Petroleum Safety Authority in November 2011 which stated as follows. “The period since the 2008 operational review of NOPSA has been one of consolidation, interspersed with ongoing legislative change, significant reviews and inquiries requiring resource intensive operational and policy responses. This year, NOPSA has had to plan and prepare for significant structural change with the passage of legislation to create NOPSEMA, which is to commence at the start of 2012. We have concluded that, notwithstanding these significant events and some recommendations for further improvement in our Report, NOPSA has firmly established itself as a respected and competent safety regulator among stakeholders and peers in both the domestic and international offshore petroleum and gas industry”.

The ANAO's Performance Audit (conducted during the calendar years 2013 and 2014) immediately precedes the next Triennial Review which is scheduled to commence in 2014.

The ANAO Report points to a number of potential improvement areas which have either been addressed or will be considered as part of NOPSEMA's ongoing reviews of its policies and procedures.

As feedback on the conduct of the Performance Audit, it is suggested that the ANAO consider raising emerging issues or concerns during the progression of the audit rather than waiting until the last weeks of the audit. Such an approach would provide an opportunity to correct misunderstandings or errors of fact prior to the production of the ANAO's Issues Papers and might facilitate better learning opportunities for the audited agency.

A detailed response to the 3 Recommendations made in the Report are provided in Appendix 1.

ANAO comment

44. Over many years, the ANAO has developed and refined its knowledge of better practice regulatory approaches, as well as drawing from the experience of various reports in Australia and overseas.28 For this audit, the ANAO applied considerable resources to developing a sound understanding of the regulatory framework applying to the offshore petroleum industry as administered by NOPSEMA. The fieldwork undertaken during the audit included the review of governance and regulatory documentation, consultation with NOPSEMA’s stakeholders, a detailed analysis of 334 sampled regulatory actions and direct observations of the conduct of regulatory activities.

45. The audit conclusion, set out at paragraphs 20–26 of the report, appropriately addresses the audit’s objective. In particular, the conclusion comments on the establishment of NOPSEMA and the arrangements it has established to deliver its regulatory functions. The audit identified that there was scope to strengthen the Authority’s management of business risks and performance measures. Further, the audit identified several areas for enhancing the effectiveness of NOPSEMA’s regulatory activities, including taking into account the risk profile of individual facilities when developing its planned safety inspection program.

46. The ANAO’s performance audits are intended to stimulate improved administration by public sector entities. The audit has highlighted that there is scope for NOPSEMA to improve its performance and achieve better outcomes consistent with its statutory objectives by strengthening elements of its governance arrangements and aspects of its regulatory functions. The recommendations in this report are directed to that end.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No 1 Paragraph 2.73 |

To support the effective management of regulatory activities, the ANAO recommends that NOPSEMA strengthen its governance arrangements by:

NOPSEMA’s response: First part agreed and complete. Parts two and three are agreed in part. |

|

Recommendation No 2 Paragraph 3.43 |

To help ensure that compliance activities are targeted to the areas of highest regulatory risk, the ANAO recommends that NOPSEMA develop its planned safety inspection program having regard to the risk profile of individual facilities. NOPSEMA’s response: Agreed in part.

|

|

Recommendation No 3 Paragraph 4.53 |

To better target the management of compliance, the ANAO recommends that NOPSEMA focus and prioritise its recommendations arising from inspections towards compliance related matters, while continuing to identify and monitor opportunities for better practice in its inspection reports. NOPSEMA’s response:Agreed in part. |

Footnotes

[1] On 21 August 2009, the Montara Wellhead Platform in the Timor Sea experienced an uncontrolled release that continued until 3 November 2009. The affected area was estimated to be up to 90 000 square kilometres. This was considered to be Australia’s most significant offshore petroleum incident. On 20 April 2010, the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig located in the Gulf of Mexico experienced an uncontrolled release following drilling of the Macondo well. The release triggered an explosion and fire causing 11 fatalities and spilling an estimated 4.9 million barrels of oil. Over one‑third of US federal waters in the Gulf were closed to fishing during the incident. The release was contained on 15 July 2010. More recently, on 27 August 2012 two workers were fatally injured on the Stena Clyde mobile offshore drilling facility located in the Otway Basin off the Victorian coast.

[2]Deloitte Access Economics, Advancing Australia: Harnessing our comparative energy advantage, Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association Limited, June 2012, p.i.

[3] Regulatory activity was previously undertaken by Designated Authorities, which were departments of the states and the Northern Territory designated as being responsible for the regulation of offshore petroleum facilities in state waters and, prior to 2005, in Commonwealth waters.

[4] Those reports were: Bills, K. and Agostini, D., Offshore Petroleum Safety Regulation Better Practice and the Effectiveness of the National Offshore Petroleum Safety Authority, Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism, June 2009; and Bills, K. and Agostini, D., Offshore Petroleum Safety Regulation: Marine Issues, Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism, 2009.

[5] Commissioner Borthwick AO PSM, Report of the Montara Commission of Inquiry, Commonwealth of Australia, 2010.

[6] Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 24 November 2010, M Ferguson, Minister for Resources, Energy and Tourism.

[7] The Joint Authority comprises the responsible Commonwealth Minister and the responsible state or Northern Territory Ministers, and may delegate any or all of its functions and powers to the respective Commonwealth, state or Northern Territory departments.

[8] NOPSEMA, Corporate Plan 2012–15, 2012.

[9] Facilities include platforms, floating production storage and offloading vessels, floating storage vessels, and mobile offshore drilling units and pipelines.

[10] Petroleum activities include drilling, seismic surveys, operation of a petroleum pipeline, operation of a facility, and construction and installation of a facility. NOPSEMA, Annual offshore performance report: Regulatory information about the Australian offshore petroleum industry to 31 December 2013, 2014, p. 9.

[11] A risk is considered as being ALARP if the cost of any reduction in that risk is grossly disproportionate to the benefit obtained from the reduction.

[12] The Authority undertakes planned inspections and produces a range of guidance material such as Guidance Notes, Safety Alerts and Compliance Policies and conducts workshops with industry to encourage voluntary compliance.

[13] Permissioning documents are key petroleum activity plans such as safety cases, or environment plans which govern how the petroleum activities are to be conducted, including incident mitigation and responses. It is an offence under the OPGGS Act to undertake petroleum activities without, or in contravention of, a permissioning document that has been accepted by NOPSEMA.

[14] The Department of Industry is also the Australian Government delegate of the Joint Authority. NOPTA, which is administered by the Department of Industry, is a technical adviser to the Joint Authority.

[15] NOPSEMA, Annual Report 2012–13, p. 53.

[16] SCER, which was established by the Council of Australian Governments is responsible for nationally significant issues and key reform related to the energy and resource sectors. Its membership comprises Commonwealth, state, territory and New Zealand Ministers with responsibility for energy and resource matters. SCER replaced the former Ministerial Council on Energy and the Ministerial Council on Mineral and Petroleum Resources in 2011.

[17] Under s. 695 of the OPGGS Act, the Minister is required to initiate operational reviews of the effectiveness of NOPSEMA (and its predecessor NOPSA) in bringing about improvements in offshore safety, structural integrity and environmental management.

[18] On 28 February 2013, the Australian Parliament passed the Offshore Petroleum and Green House Gas Storage Amendment (Compliance Measures) Act 2013, to increase criminal penalties for certain safety and environmental offences. On 16 May 2013, the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Amendment (Compliance Measures No. 2) Act 2013 was passed. This Act introduced alternative enforcement mechanisms, including application of the ‘polluter pays’ principle. Most of these amendments come into force on the commencement of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Bill, introduced into the House of Representatives on 20 March 2014. On 28 February 2014, amendments to the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2009 took effect, introducing requirements for offshore project proposal submissions and removing separate approval requirements under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act)for certain petroleum activities.

[19] Permissioning documents are key petroleum activity plans such as safety cases, or environment plans, which govern how the petroleum activities are to be conducted, including incident mitigation and responses. It is an offence under the OPGGS Act to undertake petroleum activities without, or in contravention of, a permissioning document that has been accepted by NOPSEMA.

[20] Normally attended facilities include platforms, floating production storage and offloading vessels, floating storage vessels, and mobile offshore drilling units on which the offshore workforce is continually present. Other facilities include unattended facilities such as pipelines and seasonally attended facilities, which are inspected once every two or four years.

[21] NOPSEMA is a prescribed agency under the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997. Section 46 of this Act provides that a Chief Executive must establish and maintain an audit committee with functions that include: helping the agency to comply with obligations under this Act, the regulations and Finance Minister’s Orders; and providing a forum for communication between the Chief Executive, the senior managers of the agency and the internal and external auditors of the Agency; and that the committee must be constituted in accordance with the regulations (if any).

[22] The regulations require that, if NOPSEMA is not reasonably satisfied that an EP meets the acceptance criteria when first submitted, it cannot accept the plan and must give the titleholder a reasonable opportunity to modify and resubmit the plan. If, after the titleholder has had a reasonable opportunity to modify and resubmit the EP, NOPSEMA is still not reasonably satisfied that the plan meets the acceptance criteria of the OPGGS(E) Regulations, NOPSEMA must refuse to accept the plan.

[23] The number of permissioning documents assessed has increased from 200 safety assessments in 2010 to over 400 safety, well integrity and environmental management assessments in 2013.

[24] The inclusion of good practice suggestions in inspection reports would help ensure that opportunities for improvement are brought to the attention of operators, while allowing recommendations to focus on more significant compliance related matters.

[25] On 21 August 2009, the Montara Wellhead Platform in the Timor Sea experienced an uncontrolled release that continued until 3 November 2009. The affected area was estimated to be up to 90 000 square kilometres. This was considered to be Australia’s most significant offshore petroleum incident.

[26] ANAO, Designation Letter to NOPSEMA, 18 April 2013.

[27] Section 695 of the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006.

[28] A revised and updated edition of the ANAO’s Administering Regulation Better Practice Guide was issued in June 2014.