Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Electronic Health Records for Defence Personnel

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of the Department of Defence’s planning, budgeting and implementation of an electronic health records solution for Defence personnel.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Department of Defence (Defence) provides health care services to some 80 000 Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel throughout their service, from their induction until their discharge. ADF personnel move regularly during their military service, for postings and deployments, and they receive health care services through both military and civilian channels. The number of serving personnel, their multiple locations, mobility, and access to different channels for health care increase the complexity of maintaining complete, accurate and up to date medical records. An effective electronic health (eHealth) system assists in maintaining medical records, delivering integrated health care, and in providing valuable information to stakeholders on health care services and the health of personnel.

2. In May 2009, Defence finalised a business case to deliver a contemporary health records management system for ADF personnel. The proposed system was originally called the Joint eHealth Data and Information System (JeHDI) and was later known as the Defence eHealth System (DeHS).1 The business case noted that the proposed system would centralise, electronically capture and manage ADF health records, and seamlessly link health data for ADF personnel. The system was also to be used to help assess the preparedness of ADF personnel for operations, and inform health groups2 preparing for deployment in support of operations.

3. In February 2010, Defence approached the market seeking tenders for a proven eHealth system to meet its business requirements. CSC Australia Pty Ltd (CSC)3 was awarded the contract to implement an off-the-shelf product sourced from Egton Medical Information Systems, a United Kingdom (UK) firm. The product was known as the Primary Care System (EMIS PCS)—an eHealth system used by the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD).4

4. The DeHS project has been managed by Defence’s Joint Health Command (JHC)5, with the system designed, built, hosted and supported by CSC. By December 2014, DeHS was deployed and in use across Defence’s Garrison Health environments. Deployment of DeHS for use in operational environments, such as on board ships, remained a planned activity.

DeHS funding approvals and basis

5. The Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) and Secretary of Defence approved acquisition and sustainment funding of $23.3 million in June 2009 to develop DeHS in a staged approach: from prototype to pilot, and on to a mature production system by December 2011. There was an expectation at the time that the system would be hosted and managed internally as part of the Defence ICT environment, which meant that the resources applied to support Defence’s extant eHealth systems could eventually be used to support the new system.

6. Since 2009 there have been two major increases to the original DeHS acquisition and sustainment budget of $23.3 million, resulting from changes to project scope:

- In November 2010, the Minister for Defence sought concurrence from the Finance Minister for approval of the DeHS project, including significantly higher project costs.6 The Finance Minister agreed to the commencement of final contract negotiations with CSC, conditional on the then Department of Finance and Deregulation (Finance) agreeing to final project costs prior to Defence signing the contract. In January 2011, Finance agreed to total project costs of $85.9 million, comprising $54.6 million for acquisition costs and $31.3 million for sustainment costs from 2010–11 to 2019–20.

- In February 2014, Defence obtained approval from the National Security Committee of Cabinet to increase the DeHS budget by a further $47.4 million to address capability shortfalls, including for the purchase of additional software licences and to fund training requirements.

7. Over time, the approved total DeHS project cost rose to $133.3 million, some $110.0 million higher than the original budget. At each approval stage, the project has been funded internally using Defence’s departmental budget, and Defence did not request supplementary funding from government. Nevertheless, there is an opportunity cost associated with Defence allocating significant additional funds to the project. Table S.1 provides a summary of DeHS funding approvals since 2009, and the principal reasons for the increase in costs.

Table S.1: DeHS funding approvals and basis of costings

|

Approval date |

Acquisition ($ million) |

Sustainment ($ million) |

Total ($ million) |

Costing basis and reasons for change |

|

June 2009 |

20.5 |

2.8 |

23.3 |

|

|

January 2011 |

54.6 |

31.3 |

85.9 |

|

|

February 2014 |

84.5 |

48.8 |

133.3 |

|

Source: ANAO.

8. In summary, the principal reasons for the increase in DeHS project costs were: a one year extension of the funded sustainment period; hosting the system externally rather than internally; and the inclusion of previously unbudgeted items such as training requirements.

9. In light of concerns about cost overruns, shortcomings in Defence’s project planning and the quality of the project proposals brought forward to government, the Treasurer requested that the Auditor-General consider undertaking a performance audit of the processes used by Defence in its development of DeHS. The Auditor-General agreed to the Treasurer’s request.

Audit objective and scope

10. The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Defence’s planning, budgeting and implementation of an electronic health records solution for Defence personnel. The scope of this audit covered the development and implementation phases of DeHS from project inception in 2009 through to the end of 2014, and included a focus on the quality of Defence’s advice to government.

11. To reach a conclusion against the audit objective, the following highlevel criteria were used:

- Defence adequately defined DeHS business requirements;

- Defence developed an appropriate DeHS project scope and budget, and adhered to government procurement policies and procedures;

- DeHS project governance and management supported effective system implementation, and the design and build of DeHS delivered intended functionality;

- DeHS has maintained the security and integrity of health information; and

- Defence established standardised eHealth processes through the use of DeHS.

Overall conclusion

12. Defence provides health care services to some 80 000 ADF personnel in many different locations using both military and civilian providers. In 2009 Defence recognised that it did not have contemporary information and patient records systems to support the delivery of ADF health services. To address this situation, Defence planned to procure a proven off-the-shelf 7 eHealth system to record details of health consultations, treatments and findings, and report on individual and corporate health information requirements. Procurement of the Defence eHealth System (DeHS) followed two unsuccessful earlier attempts to effectively implement an enterprise eHealth system.8

13. Overall, Defence’s planning, budgeting and risk management for the implementation of DeHS were deficient, resulting in substantial cost increases, schedule delay and criticism within government. During the initial phases of the project, Defence did not: scope and cost key components of the project; validate project cost estimates and assumptions; obtain government approval when required; follow a project management methodology; or adequately mitigate risk by adopting fit for purpose governance and co-ordination arrangements. Defence’s planning and management of the initial phases of the DeHS project were well below the standards that might be reasonably expected by Defence’s senior leadership, and exposed the department to reputational damage. The initial June 2009 budget of $23.3 million increased almost five-fold to $133.3 million by February 2014, in response to a different ICT hosting model and a better understanding of business needs. Further, Defence initially planned to develop DeHS as a mature system by December 2011, but did not complete rollout until December 2014.

14. The DeHS project was led by Defence’s Joint Health Command (JHC), which lacked experience in managing complex ICT-related projects. Further, the contribution of Defence’s Chief Information Officer Group was limited; a weakness in internal project governance and coordination arrangements which introduced substantial additional risk. A routine internal audit in 2012 and a further internal audit initiated by the Commander Joint Health in 2013 identified major shortcomings in Defence’s project management and preparedness to implement many DeHS requirements. Between 2012 and 2014, Defence strengthened project governance and management arrangements to implement both the ICT system and related business reforms. These remedial steps refocused the project and assisted the rollout of DeHS by December 2014. The system as rolled-out delivers most of the intended functionality, and notwithstanding the need for some corrective action, stakeholders have identified early benefits from the use of the system, including access to a single patient eHealth record.9

15. As indicated above, the ANAO identified significant weaknesses in the early stages of the project—relating to project planning and budgeting; and project management and implementation—which affected the overall project budget and timely implementation of outcomes. Following on from improvements in project management and implementation in the later stages of the project, an ongoing focus on system and business enhancements is required to realise the anticipated benefits of the system given the substantial investment made to date.

Project planning and budgeting

16. Shortcomings in project planning and budgeting were evident from the project’s earliest days. Defence’s initial 2009 DeHS project proposal and budget were not properly scoped, made an incorrect assumption about ICT hosting arrangements, and were not appropriately validated before approval. The approved budget did not include funding for progressive deployment of the system in the Garrison Health and operational environments, and the absence of costing detail in the proposal was not identified as a concern. Further, Defence did not seek ministerial approval of the DeHS project in 2009 in accordance with government requirements.10 Defence first informed the then Minister for Defence about the DeHS project in February 2010, before releasing the Request for Tender. In its advice, Defence informed the Minister that the estimated cost of the project was $19 million when the approved cost was actually $23.3 million, and in excess of the financial threshold for approval by the Minister for Defence. The weaknesses identified by the ANAO in the project planning and advisory phase were avoidable.

17. Defence’s approach to market in February 2010 differed from the DeHS business case in that it sought bids for an externally hosted system and ongoing support, rather than an internally hosted system. This change in direction had significant implications for the project’s scope and budget, and contributed to a subsequent approach to government seeking approval of significantly higher project costs. Five companies responded to the tender, each with international experience in designing, building, implementing and hosting an eHealth system. The tender evaluation team assessed the tenders against the evaluation criteria and shortlisted two companies to conduct negotiations for best and final offers. This process led to the selection of CSC as the preferred tenderer on the basis that it offered a robust and proven (off-the-shelf) solution that represented value for money and reduced financial, corporate and legal risks.

18. In finalising the tender selection process in November 2010, Defence arranged for concurrent approval by the Ministers for Defence and Finance of revised DeHS project funding of $85.9 million. A key matter raised by the Finance Minister was the conduct of an independent Gateway Review for the project.11 It is not evident from Defence records why a Gateway Review was not undertaken. The subsequent history of the DeHS project indicates that the decision not to proceed with a Gateway Review was an opportunity lost.

19. Leading up to November 2013, JHC identified further impediments to delivering DeHS. Defence had not properly scoped and budgeted for system deployment and business implementation, including: changes to Defence’s core ICT systems to interface with DeHS; hardware upgrades to support 1200 concurrent DeHS users; and training requirements and user software licences.12 Defence obtained approval from the National Security Committee of Cabinet in February 2014 to increase the DeHS budget by a further $47.4 million. In effect, Ministers were asked to support additional funding for system components and features which should properly have been factored into the original 2009 project proposal.

Project management and implementation

20. Defence underestimated the complexity of project managing and implementing DeHS. At the outset of the DeHS project, Defence did not follow an approved program or project management methodology, even though Defence ICT projects are required to apply proven methodologies. Commencing in 2012, two internal audits, the second initiated by JHC reported major shortfalls in DeHS project management, controls, reporting and documentation. Internal audit confirmed that key assumptions underpinning the DeHS business case were not valid and without greater focus on business implementation, the project would be at risk.

21. More fundamentally, Defence underestimated the broader program and governance challenges inherent in the project, and did not mitigate key risks until mid-2012. Defence initially adopted a narrow implementation approach, focusing on delivery of the project’s ICT component, rather than a broader program focus which treated DeHS as a key ICT enabler of Defence’s health system and capability. In April 2012, nearly three years into the project, JHC assigned responsibility for DeHS organisational level change management to a newly formed team within JHC; and in September 2012, a program management structure was implemented to provide for joint governance oversight of

ICT–related activities and business reform.

22. On a more positive note, Defence recognised the benefits of implementing an off-the-shelf solution. While Defence made necessary configuration changes to the off-the-shelf system to accommodate business needs, Defence retained the integrity of the system for future upgrades. Defence also intended that the system would automatically capture civilian health care provider referrals and reporting; support dispensing of pharmaceuticals; and exchange information with Defence’s financial management and accounting system. However, this work was not progressed, which has delayed the implementation of agreed DeHS functionality and the realisation of intended benefits.13

23. The ANAO interviewed clinical practitioners and practice managers from two health centres some six months after site rollout, and found general acceptance of DeHS from most Defence health groups. These health groups reported better patient care with access to a single patient eHealth record.14 However, stakeholders also considered there were issues requiring attention, including system performance, delays in accessing templates and longer clinical consultation periods for several health groups. DeHS is a complex system that requires ongoing management to avoid risks to business processes and technical functionality.

24. Prior to the implementation of DeHS, JHC had identified that business processes were not uniform across health centres. In consultation with health groups, JHC developed standardised business processes for the use of DeHS to support Defence’s clinical service delivery model. However, pockets of clinical practitioners elected to revert to prior business practices. The adoption of past practices does not provide a uniform basis for accurate reporting of clinical and health trends—an aid to the efficient delivery of health care services. As with any major ICT and business reform, successful implementation relies on cultural acceptance and behaviour change, and Defence should maintain an ongoing focus on stakeholder consultation as well as remediation to help realise intended benefits of the system.

Lessons learned and recommendations

25. As discussed, Defence’s management of the DeHS project was beset, in its early phases, by a range of avoidable shortcomings. A key lesson of this audit is the importance of properly scoping and planning complex ICT projects, as a basis for providing sound advice to Defence senior leadership and government, and establishing the pre-conditions for successful implementation. There are more restricted options for Defence senior leadership and government once a project that is considered beneficial is well underway and clearly requiring funds beyond its original budget. This underlines the critical importance of applying a rigorous approach at the outset of a project to develop the project scope and budget. Project proposals and cost estimates should be based on a full understanding of project parameters and risks, and subject to thorough review.

26. A further lesson of the audit is the importance of adequate coordination of internal resources and expertise—to mitigate project risks and inform effective delivery—and the adoption of sound project management methodologies and practices. Government has endorsed project management methodologies so that entities follow a structured approach in developing, overseeing and delivering intended capability, and these methodologies should be consistently followed.15 Further, Ministerial approvals, and processes such as Gateway reviews, are specified by government to oversight the effective use of public resources so as to achieve value for money in project delivery, and Defence is expected to apply these requirements.

27. The ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at providing Defence with reasonable assurance that project proposals and cost estimates are reliable; and achieving benefits realisation for DeHS by standardising use of the system and implementing agreed functionality.

Summary of entity response

28. The Department of Defence provided the following summary response, with the formal response at Appendix 1:

29. Defence acknowledges the findings contained in the audit report on the Electronic Health Records for Defence Personnel and agrees with the two recommendations.

30. Since the implementation of Defence eHealth System (DeHS), Defence has made significant improvements in the assurance of ICT projects. In particular, improvements in the governance of approval processes and the establishment of professionalization streams have reinforced the internal accountabilities. These accountabilities ensure future adherences to approved project management methodologies, ministerial approval and Gateway Review processes.

31. Defence thanks the ANAO for the insights provided regarding the system implementation of DeHS, and will incorporate the issues identified in the audit with the continued use of DeHS.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.46 |

To provide reasonable assurance that complex ICT project proposals and cost estimates are reliable, the ANAO recommends that Defence reinforce the internal accountabilities necessary to:

Defence’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 3.82 |

To achieve benefits realisation, the ANAO recommends that Defence:

Defence’s response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the Defence Electronic Health System. It also introduces the audit, including the audit objective, criteria and approach.

Overview of the Defence Electronic Health System

1.1 The Department of Defence (Defence) provides health care services to some 80 000 Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel throughout their service, from their induction until their discharge. ADF personnel move regularly during their military service, for postings and deployments, and they receive health care services through both military and civilian channels. The number of serving personnel, their multiple locations, mobility, and access to different channels for health care increase the complexity of maintaining complete, accurate and up to date medical records. An effective electronic health (eHealth) system assists in maintaining medical records, delivering integrated health care, and in providing valuable information to stakeholders on health care services and the health of personnel.

1.2 In May 2009, Defence finalised a business case to deliver a contemporary health records management system for ADF personnel. The proposed system was originally called the Joint eHealth Data and Information System (JeHDI) and was later known as the Defence eHealth System (DeHS).16 The business case noted that the proposed system would centralise, electronically capture and manage ADF health records, and seamlessly link health data for ADF personnel. The system was also to be used to help assess the preparedness of ADF personnel for operations, and inform health groups17 preparing for deployment in support of operations.

1.3 In February 2010, Defence approached the market seeking tenders for a proven eHealth system to meet its business requirements. CSC Australia Pty Ltd (CSC)18 was awarded the contract to implement an off-the-shelf product sourced from Egton Medical Information Systems, a United Kingdom (UK) firm. The product was known as the Primary Care System (EMIS PCS)—an eHealth system used by the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD).19

1.4 When announcing the system development contract, the then Minister for Defence Science and Personnel outlined the main purpose of the new system, stating that ‘[DeHS] will link health data from recruitment to discharge and allow for treating health practitioners to access a patient’s complete health record’. He described DeHS as ‘a web based system which can be accessed wherever Internet is available, while still maintaining confidentiality and data integrity’.20

1.5 The DeHS project has been managed by Defence’s Joint Health Command (JHC)21, with the system designed, built, hosted and supported by CSC. By December 2014, DeHS was deployed and in use across Defence’s Garrison Health environments. Deployment of DeHS for use in operational environments, such as on board ships, remained a planned activity.

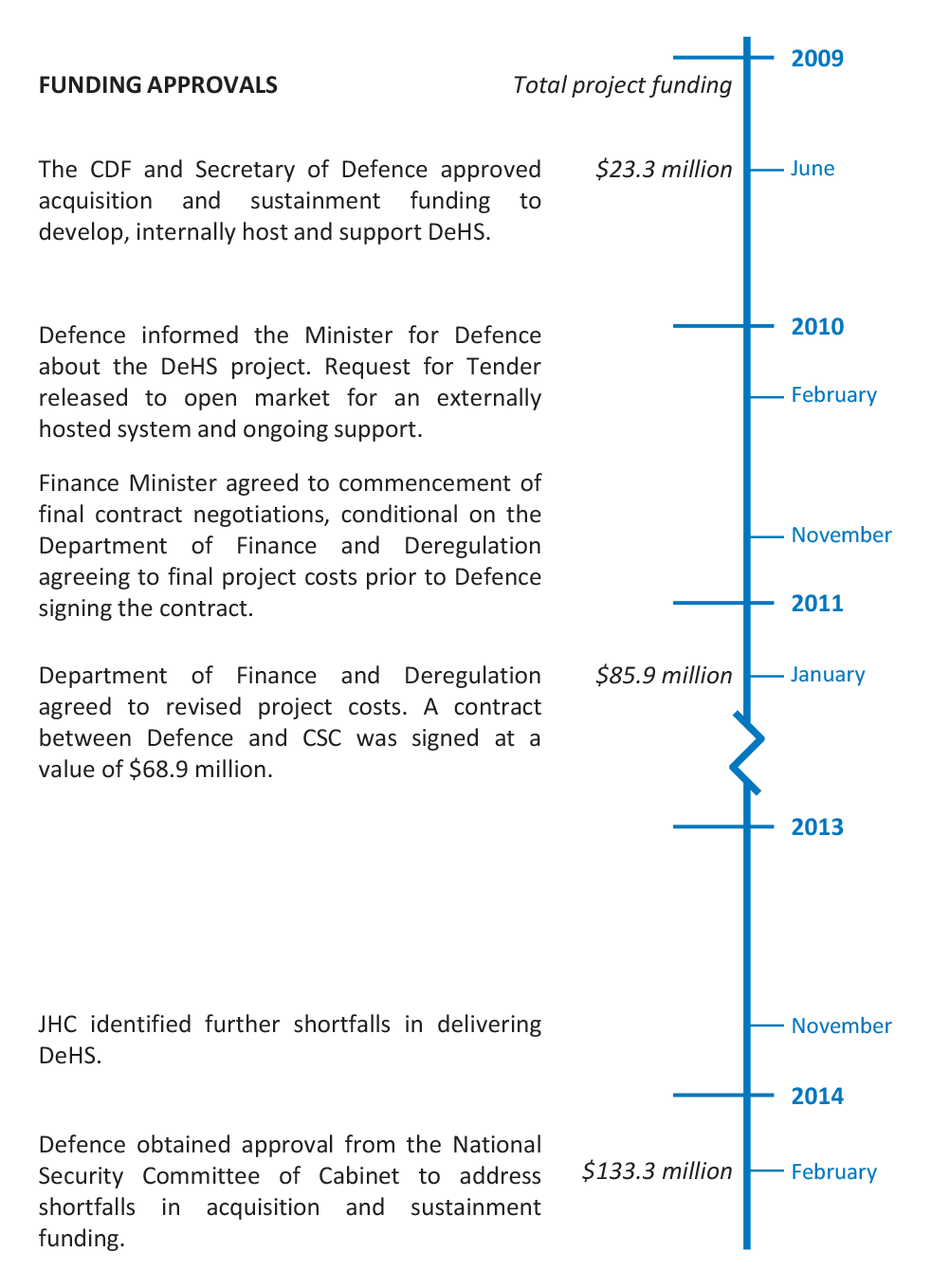

DeHS funding approvals and basis

1.6 The Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) and Secretary of Defence approved acquisition and sustainment funding of $23.3 million in June 2009 to develop DeHS in a staged approach: from prototype to pilot, and on to a mature production system by December 2011. There was an expectation at the time that the system would be hosted and managed internally as part of the Defence ICT environment, which meant that the resources applied to support Defence’s extant eHealth systems could eventually be used to support the new system.

1.7 Since 2009 there have been two major increases to the original DeHS acquisition and sustainment budget of $23.3 million, resulting from changes to project scope:

- In November 2010, the Minister for Defence sought concurrence from the Finance Minister for approval of the DeHS project, including significantly higher project costs.22 The Finance Minister agreed to the commencement of final contract negotiations with CSC, conditional on the then Department of Finance and Deregulation (Finance) agreeing to final project costs prior to Defence signing the contract. In January 2011, Finance agreed to total project costs of $85.9 million, comprising $54.6 million for acquisition costs and $31.3 million for sustainment costs from 2010–11 to 2019–20.

- In February 2014, Defence obtained approval from the National Security Committee of Cabinet to increase the DeHS budget by a further $47.4 million to address capability shortfalls, including for the purchase of additional software licences and to fund training requirements.

1.8 Over time, the approved total DeHS project cost rose to $133.3 million, some $110.0 million higher than the original budget. At each approval stage, the project has been funded internally using Defence’s departmental budget, and Defence did not request supplementary funding from government. Nevertheless, there is an opportunity cost associated with Defence allocating significant additional funds to the project. Table 1.1 provides a summary of DeHS funding approvals since 2009, and the principal reasons for the increase in costs.

Table 1.1: DeHS funding approvals and basis of costings

|

Approval date |

Acquisition ($ million) |

Sustainment ($ million) |

Total ($ million) |

Costing basis and reasons for change |

|

June 2009 |

20.5 |

2.8 |

23.3 |

Sustainment period to 2018–19. System hosted and managed internally in Defence’s ICT environment.

|

|

January 2011 |

54.6 |

31.3 |

85.9 |

Sustainment period to 2019–20. System hosted and supported externally by CSC. |

|

February 2014 |

84.5 |

48.8 |

133.3 |

Sustainment period to 2019–20. System hosted and supported externally by CSC.

|

Source: ANAO.

1.9 In summary, the principal reasons for the increase in DeHS project costs were: a one year extension of the funded sustainment period; hosting the system externally rather than internally; and the inclusion of previously unbudgeted items such as training requirements.

1.10 In light of concerns about cost overruns, shortcomings in Defence’s project planning and the quality of the project proposals brought forward to government, the Treasurer requested that the Auditor-General consider undertaking a performance audit of the processes used by Defence in its development of DeHS. The Auditor-General agreed to the Treasurer’s request.

DeHS features and potential benefits

1.11 The key features of DeHS are:

- a Primary Care System (PCS)—an eHealth care system used to record all clinical, dental, mental health and allied health consultations, treatments and findings;

- DeHS Access—an online patient-accessible summary of each patient’s eHealth record; and

- DeHS Reporting—a suite of reporting tools available to report on individual or corporate information requirements.

1.12 These three features of DeHS are intended to operate together to provide a clinical management tool that enables safe and quality health care for the ADF member. The system design provides for health groups and Defence to refer to the health information contained within DeHS to enable evidence based decision making. The DeHS business case also noted that the system would:

- inform ADF Commanders of the readiness for operational deployments of individuals and Force Elements;

- contribute to the generation of health performance and work health and safety (WHS)23 metrics to support the management of resources, planning and accountability; and

- provide for effective health management after an ADF member’s discharge. For example, the health record of an ADF member would be transferred or accessed by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs as part of ongoing care and/or to inform compensation determinations.

1.13 Table 1.2 summarises the anticipated benefits of DeHS.

Table 1.2: DeHS anticipated benefits

|

Key focus areas |

|

|

|

ADF personnel / customer |

||

|

Health readiness |

|

|

|

Productivity |

|

|

|

Defence health |

||

|

Productivity |

|

|

|

Quality of care |

|

|

|

Population health |

|

|

|

Other entities |

||

|

Claims assessment |

|

|

|

Veterans’ health |

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence’s business case for an eHealth information system.

Note A: The Medical Employment Classification (MEC) system provides a consistent tri-Service approach to the application of medical fitness standards in the employment of Defence members.

Longer term benefits

1.15 While the primary focus for DeHS is to provide a clinical health management tool which centralises, electronically captures and manages ADF health records, Defence intends to progressively extend the system’s functionality as part of other Defence projects. In particular, the ADF Deployable Health Capability (JP2060) project is to deliver health capability across operational environments; and the Defence Management Systems Improvement (JP2080) project is to improve the functionality of Defence’s corporate support systems and the interchange of information between systems.24

1.16 More broadly, the National eHealth Strategy provides a strategic framework and plan to guide national coordination and collaboration in eHealth.25 DeHS is intended to align closely with the guidance contained in the strategy and with the eHealth standards and specifications developed by the National eHealth Transition Authority (NEHTA). These standards and specifications provide for interconnectivity between health information systems.

1.17 DeHS is also expected to link with the national Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record (PCEHR)26, which is being implemented by the Department of Health as part of the National eHealth Strategy. More specifically:

[DeHS] is building the capability to interact with the national Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record (PCEHR) for the interchange of health information across private and public health systems. Members will be able to consent to participation in the PCEHR system while in Defence or when they discharge.27

Related reviews and audits

1.18 The catalyst for DeHS dates back to 1989 when the Defence Regional Support Review identified the need to centralise and computerise ADF health records. Since that time other reviews and ANAO performance audits have identified shortcomings in Defence’s management of ADF health services.28

1.19 ANAO Audit Report No.49 of 2009–10, Defence’s Management of Health Services to Australian Defence Force Personnel in Australia, highlighted inadequacies in electronic medical records management for serving personnel. The ANAO noted that:

Defence does not currently have effective information and patient records systems to support the delivery of ADF health services. These systems are needed to help realise efficiencies (for example, through the provision of better management information) in the provision of appropriate health care for ADF members.

Defence has previously attempted to introduce a patient records system, the Health Key Solution or HealthKeyS. However, users found HealthKeyS difficult to use (for example, moving between different screens is not easy and the system has poor response times). For this reason, only some health facilities currently use HealthKeyS and Defence has now decided to introduce a replacement system which is currently under development. A lesson learned from the failure of HealthKeyS is the need for the system to meet user needs. Defence expects to progressively deploy its replacement system, to be developed based on commercial off-the-shelf products and to be called the Joint e-Health Data Information system, between July 2011 and December 2013.29

1.20 Defence’s Audit Branch conducted internal audits of DeHS as part of its 2011–1230 and 2012–1331 Audit Work Programs, the second internal audit was initiated by JHC. The first audit focused on key controls in connection with the management of health care data, including privacy management, data conversion, archiving of data and compliance with relevant data management standards and legislation. The audit observed that:

Audit expected planning and project documentation to be more advanced than was observed during the review. This is particularly relevant to the security design, data migration process and benchmarking of compliance against legislation (being privacy and records management legislation). Given the extreme reputational exposure from failure to manage security, privacy and data accuracy in connection with healthcare records, and the short time frame to implement the system (less than five months), priority must be given to address these issues.

1.21 During the first internal audit, Defence management requested that the Audit Branch extend the scope of its review to examine project management processes, including financial management and business implementation. The second internal audit responded to the request and observed that as at November 2012:

Analysis of the overall financial status of the projects indicates that the:

- approved budget was underestimated by approximately $8.4 million32;

- project contingency is overspent by $2.2 million with no unallocated contingency funds available for 2013–2020;

- overall costs (e.g. Full Time Equivalent (FTE) costs and rental costs) associated with the implementation of the [DeHS] system are not being costed and tracked.

1.22 The internal audit report also expressed concern that DeHS may not realise intended business benefits:

The full benefit of [DeHS] will be only realised if it is continuously updated with up to date health records. However, the current architecture does not support this as the [DeHS] system will only be implemented in the garrison environment. It will not be available in the deployed environment or aboard Navy vessels. At this time, business processes have not been established to continuously update the [DeHS] system in instances where the system is unavailable.

The relatively tight timeframe to achieve key milestones and the readiness of Joint Health Command (JHC) to support the implementation increases the risk that the eHealth capability will not be achieved with a November 2012 implementation. Therefore, it is critical for JHC to reschedule system implementation to a timeframe which will ensure business acceptance of the system.

About the audit

1.23 The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Defence’s planning, budgeting and implementation of an electronic health records solution for Defence personnel. The scope of this audit covered the development and implementation phases of DeHS from project inception in 2009 through to the end of 2014, and included a focus on the quality of Defence’s advice to government.

1.24 To reach a conclusion against the audit objective, the following highlevel criteria were used:

- Defence adequately defined DeHS business requirements;

- Defence developed an appropriate DeHS project scope and budget, and adhered to government procurement policies and procedures;

- DeHS project governance and management supported effective system implementation, and the design and build of DeHS delivered intended functionality;

- DeHS maintains the security and integrity of health information; and

- Defence established standardised eHealth processes through the use of DeHS.

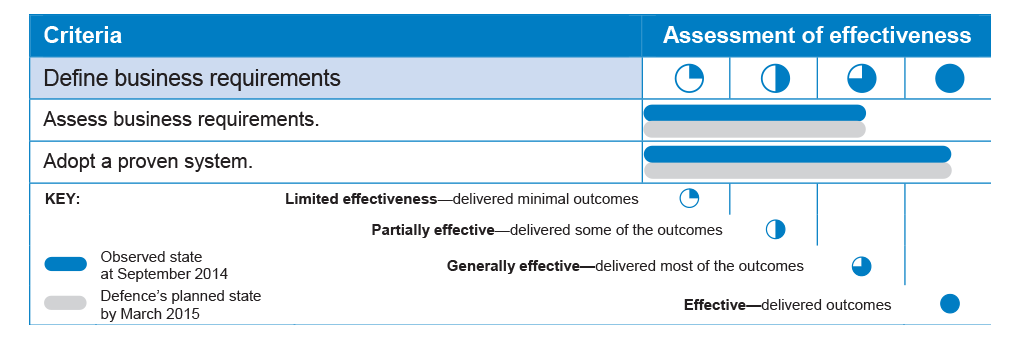

1.25 To assess the effectiveness of Defence’s administration of DeHS, the ANAO developed a grading scheme, as illustrated in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Grading scheme for assessing effectiveness

INSERT TABLE 1.3 AS FIGURE/IMAGE

Source: ANAO.

1.26 The ANAO’s assessments in terms of the audit criteria, as at 2014–15, are included in the body of the report, with a consolidated table of assessments presented in Appendix 2. The assessments are presented in the format illustrated in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4: Assessment of effectiveness against criteria

INSERT TABLE 1.4 AS FIGURE/IMAGE

Source: ANAO.

1.27 The audit fieldwork was conducted between July and September 2014. The ANAO:

- reviewed Defence’s project documentation and government submissions;

- interviewed key business stakeholders, including Defence and other Australian Public Service personnel, medical and allied health staff, and contractors involved in the delivery of the project;

- reviewed implementation of the agreed recommendations in Defence’s two internal audits; and

- examined user access controls and administrative privileged accounts that support the integrity of the information system.

1.28 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards, at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $316 000.

Structure of the report

1.29 The structure of the report is as follows:

- Chapter 2 examines Defence’s planning and procurement processes for DeHS. It also outlines the typical steps for accessing eHealth records from DeHS.

- Chapter 3 examines Defence’s project management and implementation; the security and integrity of information maintained in DeHS; and the development of standardised DeHS business processes.

2. Planning and Procurement

This chapter examines Defence’s planning and procurement processes for DeHS. It also outlines the typical steps for accessing eHealth records from DeHS.

Introduction

2.1 The effective development of complex ICT project proposals depends on a structured approach: to engage resources and expertise; identify business requirements, project scope and key risks; and provide reasonable assurance that proposals and cost estimates are reliable. A sound planning approach also informs the procurement process, and the identification of a system that is ‘fit for purpose’ to deliver intended functionality and achieve outcomes.

2.2 In this chapter, the ANAO examines Defence’s:

- definition of DeHS business requirements; and

- DeHS project scope, budget and procurement.

Defining business requirements

2.3 A business case should be prepared with due consideration given to business requirements, as a first step towards acquiring or developing a system that is fit for purpose. Before the development of the DeHS business case in 2008–09, Defence had experienced deficiencies in the collection, quality and reporting of health care information over a 15 year period. Following two unsuccessful earlier attempts to implement an eHealth system33, Defence intended to introduce a contemporary health records management system for ADF personnel.

Summary assessment

2.4 To assess Defence’s overall effectiveness in defining DeHS business requirements, the ANAO examined whether:

- the DeHS business case was informed by a formal analysis of business requirements;

- business requirements addressed patient and health group needs, management reporting and the sharing of information between Defence and other health services;

- Defence was mindful of the lessons learned from implementing extant eHealth systems, including any shortcomings, and the need for a fit for purpose system;

- the business case considered a proven ‘off-the-shelf’ solution;

- the business case aligned with Defence’s eHealth strategy and the National eHealth Strategy; and

- consideration was given to the National eHealth Transition Authority (NEHTA) standards and specifications.

2.5 Table 2.1 provides a summary assessment of Defence’s overall effectiveness in defining DeHS business requirements. The table shows the state observed by the ANAO as at September 2014; and the planned state as anticipated by Defence by March 2015.

Table 2.1: Summary assessment of Defence’s effectiveness in defining DeHS business requirements

Source: ANAO analysis.

Assessing business requirements

2.6 During the development of the DeHS business case, JHC consulted key representatives from health groups and support services—such as the Chief Information Officer Group—to better understand current and emerging business needs in the Garrison Health and Defence ICT environments. JHC also consulted the then Department of Health and Ageing and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs to define and validate the business need and system requirements necessary to support the National eHealth agenda.

2.7 The business case identified that extant Defence eHealth information systems were well below contemporary Australian practice; and there were no means to effectively facilitate multi-discipline exchange of health, mental health, epidemiological, management and work health and safety (WHS) information. As a consequence, there was a risk that some ADF members were receiving sub-optimal care. The business case also identified risks for the transition to DeHS, including the need to manage multiple eHealth systems, the requirement to redevelop disparate health processes into standardised business processes, and reputational risks should Defence encounter shortcomings in deploying an eHealth system.

2.8 The business case noted that the proposed system would:

- centralise, electronically capture and manage ADF health records, and seamlessly link health data for ADF personnel;

- assist the preparation of ADF personnel for operations, and the preparation of health groups for deployment in support of operations;

- initially be deployed in the Garrison Health environment, and later deployed in the Defence operational environment; and

- comply with national and international standards for eHealth systems.

2.9 While the business case identified business requirements and key risks, it was also somewhat ambitious. Defence planned to: aggregate patient health records from multiple Defence systems; standardise business processes across all health groups at the same time Defence was redesigning its health services support model, including its contractual arrangements; and deploy DeHS in operational environments.34 However, the business case lacked detail on how these requirements would be achieved.

Adopting a proven system

2.10 Following the 2008 ADF Health Services Review, the then Commander Joint Health recommended the investigation of a commercial or military

‘off–the–shelf’ eHealth informatics system that could fast track Defence’s system requirements. In September 2008, Defence’s Rapid Prototyping, Development and Evaluation (RPDE) program was tasked to investigate the availability of off-the-shelf products, and to confirm Defence’s business case through a proof of concept. The RPDE Report identified several off-the-shelf products that would support Defence’s business needs.

2.11 The May 2009 DeHS business case noted that a number of mature and immediately available off-the-shelf products could be integrated to form the basis of the proposed system. The business case also indicated ‘the capability proposal is well aligned to the existing need and can work with legacy ADF systems such as HealthKeyS, PMKeyS and ROMAN.’ 35

Project scope, budget and procurement

2.12 Having established the DeHS business case, Defence commenced work on a procurement process for the system. That process confirmed the availability of a suitable ‘off-the-shelf’ system, and led to changes in the project scope and budget. Defence approved project funding internally in June 2009, sought government approval of the DeHS project during the procurement process in November 2010, and later sought government approval of additional project funding in February 2014.

Summary assessment

2.13 To assess Defence’s overall effectiveness in scoping, budgeting for and procuring DeHS, the ANAO examined whether:

- business and functional requirements appropriately informed the procurement process;

- the procurement process adhered to government and Defence procurement policies and procedures;

- an accurate budget—to procure, implement and sustain the system—was prepared and formally approved;

- DeHS is fit for purpose as an ‘out-of-the-box’ solution and configurable to accommodate specific Defence requirements;

- additional functionality can be introduced with nominal ICT system changes; and

- DeHS can interface with extant information systems.

2.14 Table 2.2 provides a summary assessment of Defence’s overall effectiveness in scoping, budgeting for and procuring DeHS. The table shows the state observed by the ANAO as at September 2014; and the planned state as anticipated by Defence by March 2015.

Table 2.2: Summary assessment of Defence’s effectiveness in scoping, budgeting for and procuring DeHS

Source: ANAO analysis.

Supplying business requirements

2.15 A well prepared and comprehensive business case informs the procurement process. Tender documentation needs to clearly express business and functional requirements for potential suppliers, and the criteria to be used to assess tender proposals.

2.16 Following the development of the DeHS business case, in June 2009, JHC submitted a proposal to the CDF and Secretary of Defence seeking approval to commence the DeHS project in the first quarter of 2009–10. The proposal advised that:

- Defence’s extant eHealth systems were below contemporary Australian practices;

- ‘off-the-shelf’ products were available that could interface with Defence ICT systems and other information systems;

- further delays to implement an eHealth system posed risks to Defence’s reputation; and

- DeHS had many potential benefits and would help shape the National eHealth agenda.

2.17 The CDF and Secretary of Defence approved acquisition and sustainment funding for DeHS in June 2009 at a cost of $23.3 million. JHC then commenced work on the DeHS procurement process. Defence released an open approach to the market in February 2010. The Request for Tender statement of work reflected the DeHS business case in detailing the required high level functionality of the system36:

- Clinical care—support the assessment and treatment of patients and the provision of health care within Defence;

- Practice management—support the coordination and operation of the health care providers’ business;

- Health management and reporting—support overall health management and reporting for analysis and management needs; and

- Interface with systems—interface with other Defence and NEHTA-compliant systems.

2.18 To better assist the market in understanding Defence’s complex business and technical environments, the statement of work also provided background information on the business and service delivery model for JHC, an overview of the Defence computing environment, and the proposed system architecture and information management lifecycle. Overall, Defence made significant effort to inform the market of the proposed concept of operations for DeHS, the functional and performance specifications for the system, and the business and operational scenarios the system must support.

2.19 Five companies responded to the tender, each with international experience in designing, building, implementing and hosting an eHealth system. The tender evaluation team assessed the tenders against the evaluation criteria and shortlisted two companies to conduct negotiations for best and final offers. This process led to the selection of CSC as the preferred tenderer on the basis that it offered a robust and proven (off-the-shelf) solution that represented value for money and reduced financial, corporate and legal risks.

2.20 CSC was awarded the contract to implement an off-the-shelf product sourced from Egton Medical Information Systems, a United Kingdom (UK) firm. The product was known as the Primary Care System (EMIS PCS)—an eHealth system used by the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD). The military version of EMIS PCS was selected by MoD in May 2006 as part of the Defence Medical Information Capability Programme. The system has been implemented by the MoD and is reported to support over 16 000 consultations per day. In the early phases of the DeHS project, then Commander Joint Health and project staff discussed the UK experience of EMIS PCS with MoD colleagues. Defence sought reassurance from its discussions with MoD that EMIS PCS was ‘fit for purpose’ and would only require configuration changes.

2.21 The final negotiated contract price with CSC was $68.9 million for the period 2010–11 through to 2019–20. This included initial build costs of $30.0 million; infrastructure and software rental costs of $16.0 million; managed support of $18.6 million from 2015–16 to 2019–20; and EMIS licencing costs of $4.2 million.

Budget and approval

2.22 As discussed, the CDF and Secretary of Defence approved acquisition and sustainment funding of $23.3 million in June 2009, and by January 2011 the final negotiated contract price with CSC was $68.9 million.37

2.23 Over the course of the project, Defence developed a better understanding of the project scope and the associated costs, which led to government approval of additional project funding on two occasions. The project budget increased to $85.9 million in January 2011 and again to $133.3 million in February 2014, some $110 million higher than the original budget. The funding approvals are illustrated in Figure 2.1 and discussed in the following paragraphs.

Figure 2.1: DeHS project funding approvals

Source: ANAO.

2.24 The June 2009 DeHS project proposal did not include funding for progressive deployment of the system in the Garrison Health and operational environments. The proposal instead made the assumption that savings from Defence’s Strategic Reform Program (SRP)38 remediation activities would fund full deployment across the Garrison Health environment, and that the program to establish the ADF Deployable Health Capability (JP2060)39 would fund deployment in the operational environment. However, Defence did not determine the level of funding required from these alternate sources, and the absence of costing detail in the proposal was not identified as a concern.

2.25 Further, Defence did not identify in June 2009 that the project required ministerial rather than departmental approval because it exceeded the financial threshold for ministerial approval of $20 million.40 Defence first informed the then Minister for Defence about the DeHS project in February 2010, before releasing the Request for Tender. However, Defence informed the Minister that the estimated cost of the project was $19 million when the approved cost was actually $23.3 million.41

2.26 Defence’s approach to market in February 2010 differed from the DeHS business case in that it sought bids for an externally hosted system and ongoing support, rather than an internally hosted system. This change in direction had significant implications for the project’s scope and budget, and it was not approved by Defence senior leadership prior to commencing the procurement process.

2.27 In November 2010, the Minister for Defence sought concurrence from the Finance Minister for approval of the DeHS project, including significantly higher project costs. The Finance Minister agreed to the commencement of final contract negotiations with CSC, conditional on the then Department of Finance and Deregulation (Finance) agreeing to final project costs prior to Defence signing the contract.

2.28 A key matter raised by the Finance Minister was the conduct of a Gateway Review for the project. These independent reviews are normally conducted for all IT projects valued at over $10 million, and are intended to identify and focus on issues of most importance to a project, so that the project team’s effort is directed to those aspects that will help the project be successful.42 However, the Finance Minister pointed out that in the case of DeHS:

the project has progressed too far for the Gateway Review Process to add value, even though the Gateway team has indicated that [DeHS] would have benefited from the review process.43

2.29 It is not evident from Defence records why a Gateway Review was not undertaken. The subsequent history of the DeHS project indicates that the decision not to proceed with a Gateway review was an opportunity lost.

2.30 In January 2011, the then Department of Finance and Deregulation (Finance) agreed to project costs of $85.9 million, including $54.6 million towards acquisition costs and $31.3 million for sustainment costs from 2010–11 to

2019–20. The increase in project costs was to be funded internally using Defence’s departmental budget. The contract between Defence and CSC Australia was signed on 13 January 2011 at a value of $68.9 million. The difference between the total project costs of $85.9 million and the value of the CSC contract ($68.9 million) mostly comprised project management services (provided by Oakton), and project contingency funding.

2.31 By November 2013—during the fifth year of the project and on the eve of commencing the implementation phase—JHC identified further impediments to delivering DeHS. Defence had not properly scoped and budgeted for system deployment and business implementation, including: changes to Defence’s core ICT systems to interface with DeHS; hardware upgrades to support 1200 concurrent DeHS users; and training requirements and user software licences. While Defence expected that some 50 per cent of JHC’s workforce (1200 of 2500 staff) would access DeHS based on MoD’s experience, Defence had initially purchased only 400 software licences.44

2.32 Defence obtained approval from National Security Committee of Cabinet in February 2014 to increase the DeHS budget by a further $47.4 million. According to Defence’s submission to government, the requirements for an eHealth system had grown substantially over time, and the need to refine the scope and increase the budget reflected a better understanding of Defence’s current and long term needs in managing health services for ADF personnel. The budget adjustment increased the overall cost of the project to $133.3 million, some $110.0 million higher than the original budget. While Defence did not request supplementary funding from government, there is nevertheless an opportunity cost associated with Defence allocating significant additional funds to deliver the project.

2.33 In summary, Defence’s budgeting and approval processes for the implementation of DeHS were deficient, resulting in substantial cost increases and criticism within government.

Shaping the system to meet business requirements

2.34 On a more positive note, Defence recognised the benefits of implementing an off-the-shelf solution. According to CSC, the EMIS Primary Care System (EMIS PCS) is designed to effectively support the detailed care processes involved between the patient and primary health care providers, as well as practice management of health centres.45 EMIS PCS has been used by the MoD for some time as an interoperable medical information and communications system. The functionality delivered by EMIS PCS to MoD is similar to Defence’s business requirements for DeHS.

2.35 The DeHS design involves a number of integrated clinical modules to enable collaborative work across primary care settings and health groups. Authorised health care providers can gain access to DeHS to immediately review patient eHealth records. This removes potential delays in retrieving (paper-based) medical records, specialists’ reports, diagnostic imaging and pathology results, and provides for a better understanding of patients’ medical history, prescriptions and treatments during clinical consultations.46

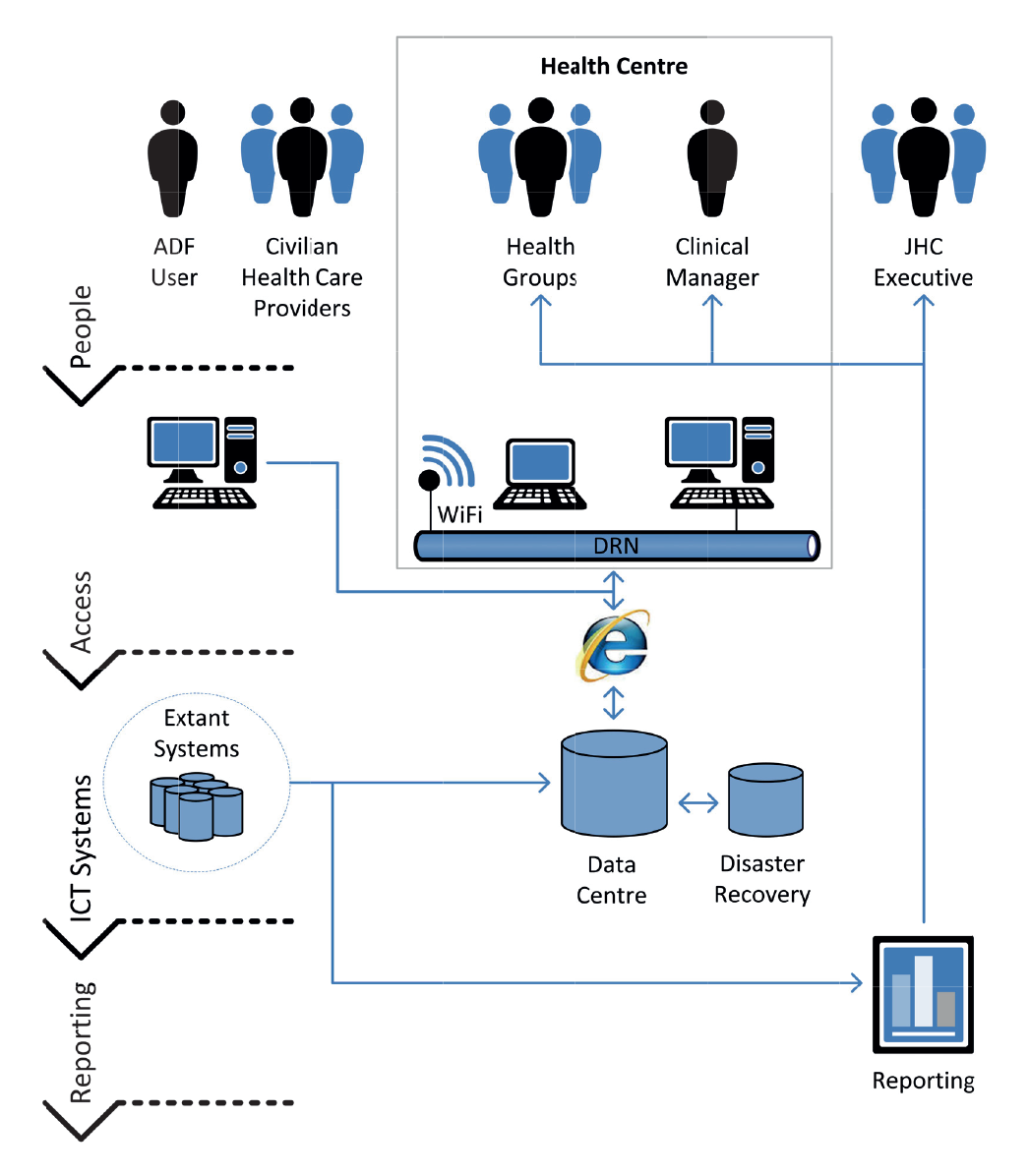

2.36 Accessing patient eHealth records and summary reports from DeHS involves four steps (illustrated in Figure 2.2):

- people—role-based access controls distinguish between clinical practitioners, practice managers and administrative personnel;

- access—access to DeHS is via the Defence Restricted Network (DRN) using a Desktop PC or a ‘computer-on-wheels’47, or via a standard (public) Internet connection using a Windows-based PC with Internet Explorer;

- ICT systems—eHealth records are stored in the DeHS primary data centre, and other information systems that interface with DeHS can amend data, append clinical information to patient records and extract information for Defence reporting; and

- reporting—Defence executives, practice managers and administrative personnel receive various health reports.48 Data that is required and approved to inform reporting is extracted from the primary data centre and stored within separate infrastructure hosted within the Defence network.49

Figure 2.2: Typical steps for accessing eHealth records from the primary data centre and developing reports

Source: ANAO analysis of DeHS processes.

2.37 The build and implementation phases of DeHS occurred in parallel with other ADF business change initiatives, as part of a broader JHC transformation. This approach required Defence to align the DeHS clinical service delivery model with JHC’s new concept of operations, including:

- an organisational restructure of JHC—nine Area Health Services were replaced by five Regional Health Services, with five Regional Health Directors responsible for coordinating health service delivery within their region, including clinical services, resource management and training of personnel50; and

- realigning the health services support model, including its contractual arrangements—in October 2012, Medibank Health Solutions (MHS) commenced administering national health care services for Defence, by providing access to medical practitioners and specialists, allied health professionals, hospital, radiology, pathology and optometry services, and referral services.51

2.38 MHS personnel administer both on-base and off-base health care services for ADF personnel. DeHS is the primary health care system for onbase services, with consultations, prescriptions and treatments directly recorded in patient Defence eHealth records. In contrast, health professionals do not use DeHS when performing off-base services because the system is only being deployed in the Garrison Health environment. DeHS is technically able to interface with MHS and there are ongoing discussions to facilitate the commencement of this process. Currently the transfer of consultation notes, specialist referral and diagnostic summary reports relies on the exchange of paper-based files.52

2.39 In summary, DeHS is designed to support clinical care processes between patients and health care providers, as well as practice management of health centres and reporting on health care activities. However, DeHS is designed to interface with external health care services if the provider elects to do so.

Conclusion

2.40 Defence’s initial 2009 DeHS project proposal and budget were not properly scoped, made an incorrect assumption about ICT hosting arrangements, and were not appropriately validated prior to approval. Further, the approved budget did not include funding for progressive deployment of the system in the Garrison Health and operational environments, and the absence of costing detail in the proposal was not identified as a concern.

2.41 Defence did not seek ministerial approval of the DeHS project in 2009 in accordance with government requirements. Defence first informed the then Minister for Defence about the DeHS project in February 2010, before releasing the Request for Tender. In its advice, Defence informed the Minister that the estimated cost of the project was $19 million when the approved cost was actually $23.3 million, and in excess of the financial threshold for approval by the Minister for Defence.

2.42 Defence’s approach to market in February 2010 differed from the DeHS business case in that it sought bids for an externally hosted system and ongoing support, rather than an internally hosted system. This change in direction had significant implications for the project’s scope and budget, and contributed to a subsequent approach to government seeking approval of significantly higher project costs.

2.43 Five companies responded to the tender, each with international experience in designing, building, implementing and hosting an eHealth system. The tender evaluation team assessed the tenders against the evaluation criteria and shortlisted two companies to conduct negotiations for best and final offers. CSC was selected as the preferred tenderer on the basis that it offered a robust and proven (off-the-shelf) solution that represented value for money and reduced financial, corporate and legal risks.

2.44 In November 2010, in the context of finalising the tender selection process, Defence arranged for concurrent approval by the Minister for Defence and Finance Minister of revised DeHS project funding of $85.9 million. A key matter raised by the Finance Minister was the conduct of an independent Gateway Review for the project, and it is not evident from Defence records why a Gateway Review was not undertaken.

2.45 In early 2012 JHC requested a Defence internal audit to address scope and cost concerns and established a program manager to take over the running of the requisite program of work. The audit found that Defence had not properly scoped and budgeted for system deployment and business implementation, including: changes to Defence’s core ICT systems to interface with DeHS; hardware upgrades to support 1200 concurrent DeHS users; and user software licences and training requirements. To fund additional system components and features, Defence obtained approval from the National Security Committee of Cabinet in February 2014 to increase the DeHS budget by a further $47.4 million.

Recommendation No.1

2.46 To provide reasonable assurance that complex ICT project proposals and cost estimates are reliable, the ANAO recommends that Defence reinforce the internal accountabilities necessary to:

- properly scope, cost and validate project proposals; and

- adhere to approved project management methodologies, ministerial approval and Gateway Review processes.

Defence response: Agreed

2.47 Defence has already made significant improvements in the assurance of ICT projects. Since the inception of the DeHS project and the deficiencies identified within this audit, CIOG and Defence have improved governance around approval processes including:

- establishing the Business Relationship Management Office with dedicated personnel involved in understanding client requirements;

- limiting the ability to procure ICT capability outside CIOG;

- mandatory involvement of financial assurance staff in reviewing project approval documentation; and

- establishing the ICT Investment Review Committee.

2.48 CIOG has established professionalisation streams including:

- establishing a dedicated Project and Program Management stream;

- professionalising project and program managers;

- enhancing the roles of the CIOG Portfolio Management Office; and

- formalising structures placed around projects (including identification of Responsible Officers).

2.49 The professionalisation of project and program managers has reinforced the internal accountabilities necessary to adhere to approved project management methodologies, ministerial approval and Gateway Review processes.

2.50 Defence is confident ICT project and program management and internal accountabilities necessary to properly scope, cost and validate project proposals has improved.

2.51 The delegations for the procurement of ICT both software and hardware are centralised to CIOG under FINMAN 2 Schedule 1 Part 3 & 4. This excludes all groups and service ability to procure ICT without involvement of CIOG.

2.52 All proposals including ICT are now reviewed by embedded finance staff within VCDF under the Finance Shared Services model.

3. System Implementation

This chapter examines Defence’s project management and implementation; the security and integrity of information maintained in DeHS; and the development of standardised DeHS business processes.

Introduction

3.1 The successful implementation of an eHealth system is dependent on sound project management and implementation, including rigorous ICT system development and testing, and a consultative approach to rolling out and making improvements to the system. It is also critical that the health information captured in the system is accurate and secure so that stakeholders have confidence in the integrity of the system. The ICT component is only one part of an eHealth solution, which relies on the design and implementation of standardised business processes to achieve efficiencies in health practice and effectively capture useful information for health reporting and management purposes.

3.2 In this chapter, the ANAO examines:

- DeHS project management and implementation;

- the security and integrity of information maintained in DeHS; and

- delivery of standardised DeHS business processes.

Project management and implementation

3.3 Government entities should develop and implement complex ICT systems in accordance with endorsed program or project management methodologies.53 Key success factors include close oversight of the project, and regular testing and feedback to identify and resolve ICT and business issues and meet business requirements. Defence considered the lessons learned from past attempts to deliver eHealth systems54, which had experienced shortcomings, and decided to adopt a staged approach for the design, build, testing and implementation of DeHS.

Summary assessment

3.4 To assess Defence’s overall effectiveness in project managing and implementing DeHS, the ANAO examined whether:

- project and ICT system roles, responsibilities and decision rights are clear, and monitored through an agreed accountability framework;

- the ICT system is: robust and reliable; secure from unauthorised access; and capable of, or expandable to, support increases in users;

- the ICT system integrates with appropriate Defence systems to support the eHealth system, and can integrate with extant information systems across Australian Government entities and health services;

- requirement, system and usability acceptance testing was conducted to deliver functional and business requirements, and optimise performance; and

- the ICT system is deployed as designed, maintained to deliver ongoing and optimal performance, and enhanced as required.

3.5 Table 3.1 provides a summary assessment of Defence’s overall effectiveness in project managing and implementing DeHS. The table shows the state observed by the ANAO as at September 2014; and the planned state as anticipated by Defence by March 2015.

Table 3.1: Summary assessment of Defence’s effectiveness in project managing and implementing DeHS

INSERT TABLE 3.1 HERE (AS A GRAPHIC)

Source: ANAO analysis.

Establishing management arrangements

3.6 Typically, ICT project documentation provides information on proposed management arrangements, covering issues such as: decision-making and governance (the project sponsor, governance committee or project board); oversight and control of the project (the steering committee); and day-to-day management and reporting on progress, problems and review points (the project manager). Effective management arrangements can instil confidence in decision-makers that all stages of the project are well managed and that project status updates are timely, accurate and useful.

3.7 DeHS management arrangements were established upon project commencement in June 2009. The project governance framework set out organisational arrangements, roles and responsibilities, resources, communication arrangements, and monitoring and reporting arrangements. Two key elements of the governance framework were a DeHS Project Board and project management arrangements.

3.8 The Project Board is chaired by the Commander Joint Health and includes senior representatives from Defence’s Chief Information Officer Group (CIOG), senior users within Joint Health Command (JHC), the program manager, independent advisors, and the contractor (CSC). Board Meetings have been held monthly and minutes of meetings record project status updates, discussions and key decisions made to inform project directives.55 In the design and build phases of the project, Oakton represented the Commonwealth as the project manager and provided project management support.

3.9 There were clear signs that implementation of DeHS was off-track in 2011. Defence’s Audit Branch undertook fieldwork for an internal audit focused on implementation of DeHS, in particular the adequacy of security and privacy controls. The resultant internal audit report stated that:

Audit expected that planning and project documentation to be more advanced than was observed during the review. This is particularly relevant to the security design, data migration process and benchmarking of compliance against legislation (being privacy and records management legislation). Given the extreme reputational exposure from failure to manage security, privacy and data accuracy in connection with healthcare records, and the short time frame to implement the system (less than five months), priority must be given to address these issues.56

3.10 Project Board minutes also recorded shortcomings in the contribution of CIOG. There were delays in the delivery of DeHS work packages by CIOG, including integration of DeHS with extant Defence information systems, and delivery of ICT hardware to Garrison health environments.

3.11 Following on from the findings of the internal audit, in October 2011, the Commander Joint Health requested that the Defence Audit Branch assess DeHS project management, implementation management and financial management. The internal audit report noted that:

Joint Health Command (JHC) formally established a related Business Implementation Team (BIT) project in April 2012. This team is responsible for managing organisational level change management (including training), the development of policies and procedures, and undertaking tasks which fall outside the scope of the [DeHS] project team. As at August 2012, the terms of reference and project plan for the BIT project had not yet been finalised.

The development and business implementation of the [DeHS] system relies on the delivery of both the [DeHS] and BIT projects. The current governance arrangements for the two projects are ineffective due to overlaps in scope, diluted accountability and unclear lines of responsibility.57

3.12 In essence, JHC had not followed the advice of program and project management methodologies by planning and coordinating for both ICT and business changes from the outset of the project. Defence initially adopted a narrow implementation approach, focusing on delivery of the project’s ICT component, rather than a broader program focus which treated DeHS as a key ICT enabler of Defence’s health system and capability. JHC lacked experience in managing complex ICT-related projects, and CIOG’s contribution was limited; weaknesses in internal project governance and coordination arrangements which introduced substantial additional risk.

3.13 In September 2012, a program management structure was implemented to provide joint governance and oversight of ICT-related activities and business reform. The revised governance and management arrangements involved: establishing a DeHS Program and aligning system and business implementation projects; realigning the Projects Board’s focus on program-related issues, the budget, risks and business implementation; assigning program management responsibility to a JHC staff member with program management support to be provided by Oakton resources; and establishing weekly meetings between JHC and CSC. Further, in late 2012, the Project Board decided to manage a range of project risks by rescheduling full DeHS implementation for late 2013—a 12 month delay in the schedule.

3.14 In April 2013, the Project Board informed the Defence Advisory Committee58 of a number of key achievements it attributed to the new governance restructure and program management arrangements, including:

- more than 80 per cent of the procedures which align system functionality with business requirements had been finalised;

- strengthened governance and oversight of the project’s financial status and funding requirements;

- reprioritisation of identified system and business enhancements;

- implementation of internal audit recommendations was nearing completion; and

- a more cohesive and coordinated approach to the rollout of DeHS.

3.15 In summary, DeHS management arrangements were inadequate through to mid–2012 because they did not provide for coordinated oversight and development of both ICT-related activities and business reform—a shortcoming which highlights that Defence did not follow endorsed program and project management methodologies. Project governance and management arrangements have improved over time, notably following internal review. The Project Board’s assessments of overall progress led it to delay full implementation by 12 months so as to mitigate risk.

Building the ICT environment

3.16 DeHS is complex in design and build, and the system relies on a well implemented and managed ICT environment to deliver intended functionality in a secure and timely manner.

3.17 As previously discussed, Defence recognised the benefits of implementing an off-the-shelf solution, and in January 2011 entered into a contract with CSC to procure the Primary Care System (EMIS PCS) used by the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD).59 During the subsequent build phase of the DeHS project, CSC made necessary configuration changes to the off-the-shelf system to accommodate Defence’s business needs, while retaining the integrity of the system for future upgrades. CSC also produced detailed design specifications, ICT architecture and supporting artefacts to address Defence’s business requirements for system interoperability with extant information systems.

3.18 A high-level description of DeHS is one of a complex system-of-systems located across geographically dispersed ICT environments. The core of the system is the EMIS PCS suite of clinical modules that provide the user interface to capture and retrieve patient data. EMIS PCS and patient eHealth records are stored in a centralised primary data centre in Sydney. Data and health information is exchanged between DeHS and other internal and external information systems through a secure network. Only data that is required and approved to inform reporting is extracted from the primary data centre and stored in separate infrastructure hosted within the Defence network. Backup data is stored within a secondary data centre located in Melbourne, for use in the event of disaster recovery.

3.19 A user description of DeHS is one of a centralised eHealth system that is accessible by authorised users through a web interface from the Defence network or via any standard (public) Internet connection. The system is a fully managed service, including IT maintenance, server back-up and software upgrades.

Connecting with extant systems

3.20 A high-level functionality requirement of DeHS is the exchange of data and health information with other ICT systems located inside and outside the Defence network.

3.21 Defence relies on management information from its systems to make key decisions concerning current and future personnel and equipment availability, and to assess preparedness and operational readiness. Defence has three enterprise resource planning systems in the management information domains of:

- personnel—the Personnel Management Key Solution (PMKeyS);

- finance—the Resource and Output Management and Accounting Network (ROMAN); and

- logistics—the Military Integrated Logistics Information System (MILIS).

3.22 The implementation of DeHS is intended to support Defence management with a fourth enterprise-level resource planning system, in the health domain.

3.23 An interface between DeHS and PMKeyS is planned to be implemented this financial year and will support the up-to-date exchange of relevant personnel information. The data exchange reduces multiple sources of the same data and the administrative overhead when personnel records are updated.

3.24 In order for DeHS to interface with other systems, Defence needed to work with third party vendors to plan, fund and make changes to related systems. However, this scoping activity was not progressed and Defence was not well positioned to proceed with system interfaces. As a consequence, Defence decided to not enable:

- an interface to ROMAN;

- integration with Defence’s extant dispensing module for pharmaceutical services (FRED) and pharmaceutical information logistic system (PILS); and

- electronic reporting (eReports) and referrals (eReferrals) from civilian health care providers’ NEHTA-compliant eHealth systems.

3.25 Defence’s decision not to exchange financial data between systems followed the awarding of the Garrison Health service contract to Medibank Health Solutions (MHS), including financial reporting responsibilities. Defence also took into account the scope and cost to reconfigure ROMAN, which was considered to be approaching the end of its service. Defence now relies on MHS’s accounting information system for invoicing and financial reporting on Garrison Health services.

3.26 In relation to the interface between DeHS and FRED/PILS, a July 2012 briefing from the DeHS project manager to the Commander Joint Health noted that:

The Contractor is responsible for the [DeHS] System end point of the interfaces … The Contractor will not be responsible for the external end points of the systems for the aforementioned interfaces. …

It should be noted that the [DeHS] project was not funded to upgrade internal Defence systems to participate in information exchange with [DeHS]. Thus funding for any external interfaces would have to be sought for what is essentially Commonwealth Furnished Material.60