Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Efficiency of the Australian Passport Office

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The efficiency of the DFAT’s processing of passport applications is important to the ability of Australian citizens to travel overseas and ensuring the process obtains the most benefit from available resources. Previous ANAO performance audits focused on the passports function were completed in May 2012 and April 2003.

Key facts

- Australian citizens are entitled to be issued with a passport under the Australian Passports Act 2005. Passport fees are imposed as taxes.

- The department’s key performance indicators for providing efficient passport services relate to how quickly it processes applications once in its systems, discounting any time applications are placed ‘on hold’.

What did we find?

- The delivery of passport services has not been efficient.

- Processes are partly in place for the efficient processing of passport applications. The arrangements focus on timeliness with insufficient attention given to resource efficiency. The department’s approach is not customer focused.

- Passport applications are not being processed in a time and resource efficient manner.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made nine recommendations aimed at improving the measurement of time efficiency, a greater focus on resource efficiency, improved complaints handling and improving the department’s time and resource efficiency. The department agreed to all nine recommendations.

3.1m

passports issued in 2022–23.

24%

of applications processed between June 2022 and June 2023 took longer than six weeks.

56%

fewer applications processed per full-time equivalent staff member per quarter in 2022–23 compared to before borders closed.

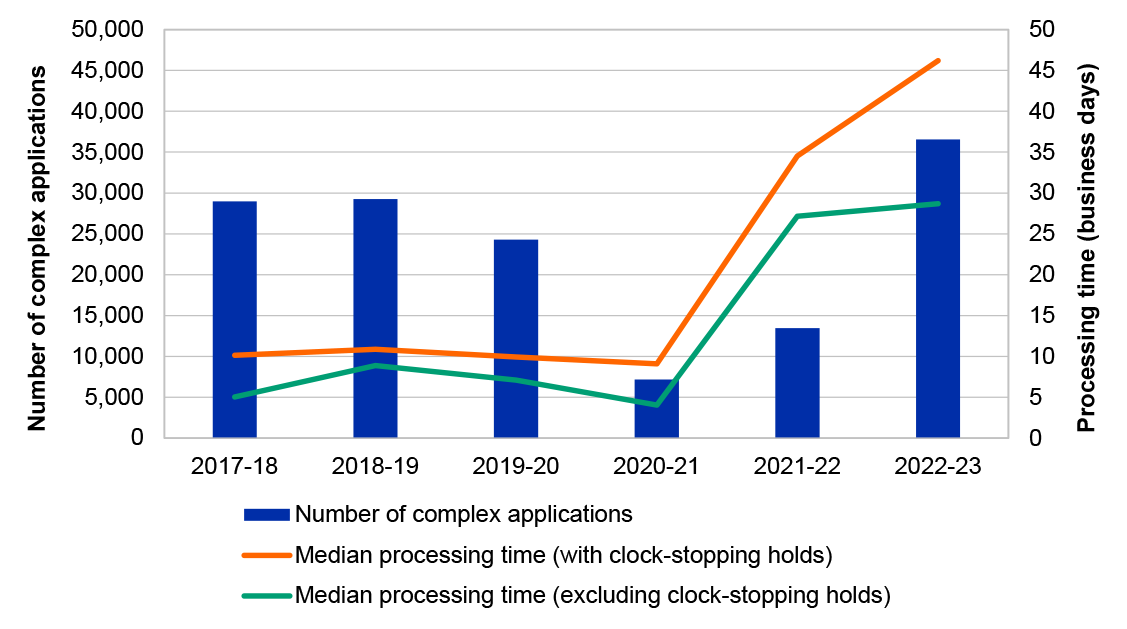

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Australian citizens are entitled to be issued with a passport under the Australian Passports Act 2005 (the Passport Act). 1 A passport enables travel across borders (with the necessary visas or entitlements) and within Australia can also act as important proof of identity. Non-citizens may be eligible to apply for other types of travel documents.2

2. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is responsible for issuing passports to Australian citizens in line with the Passport Act, with delivery of passport services in Australia and overseas being one of DFAT’s three key outcomes.

3. In July 2006, DFAT created the Australian Passport Office (APO) as a separate division to provide passport services. DFAT has offices in each Australian capital city to deliver passport services and works with DFAT diplomatic and consular missions to provide services to Australians located overseas. The Australian Trade and Investment Commission (Austrade) also provides passport services in eleven overseas locations (nine countries) where DFAT does not have a diplomatic or consular presence.3

Effect of international border closures on demand for passport services

4. Beginning in January 2020 travel restriction measures were progressively implemented in response to the emergence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Following the closure of the international border, the number of applications lodged dropped such that average quarterly demand for passport services during the border closure remained about three and a half times lower than the average before implementation of border restrictions. As a result, over the six quarters of border restrictions, 2.2 million fewer passports were issued when compared to the previous six quarters.

5. Demand for passports began increasing immediately following the reopening of the international border in November 2021. The number of applications lodged in the seven quarters following the reopening of the international border was on average 22 per cent higher than pre-pandemic levels per quarter. The increased demand for services was consistent with the passports demand modelling conducted by DFAT. That modelling predicted as early as December 2020 that the low number of passports lodged in 2020 would result in a ‘pent-up demand surge’ in 2022, providing the department with time to prepare for a sustained increased demand for passport services.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

6. The efficiency of DFAT’s processing of passport applications is important to the ability of Australian citizens to travel overseas and ensuring the process obtains the most benefit from available resources. Previous ANAO performance audits focused on the passports function were completed in May 20124 and April 2003.5 This performance audit was conducted to provide independent assurance to the Parliament that the processing of passports by DFAT is efficient.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to assess the efficiency of DFAT’s delivery of passport services through the Australian Passport Office. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has DFAT put in place efficient processes for the processing of passport applications?

- Is DFAT’s processing of passport applications efficient?

Conclusion

8. DFAT has not been efficiently delivering passport services. While the department has timeframe targets for processing applications those targets are not customer focused and are not being consistently met. There are no resource efficiency targets; the average cost to produce a passport has increased more than the increase in the price of labour; and staff efficiency, which was improving up until the COVID-19 pandemic, has deteriorated since the international border was reopened.

9. Processes are partly in place for the efficient processing of passport applications. The arrangements focus on timeliness of processing with insufficient attention given to resource efficiency. In addition, the department’s approach is not sufficiently customer focused:

- calculations of the time taken to process passport applications do not reflect the full amount of time experienced by citizens from when they lodge their application to when they receive a passport; and

- the department does not centrally capture and analyse all complaints received so as to identify improvement opportunities.

10. Passport applications are not being processed in a time and resource efficient manner:

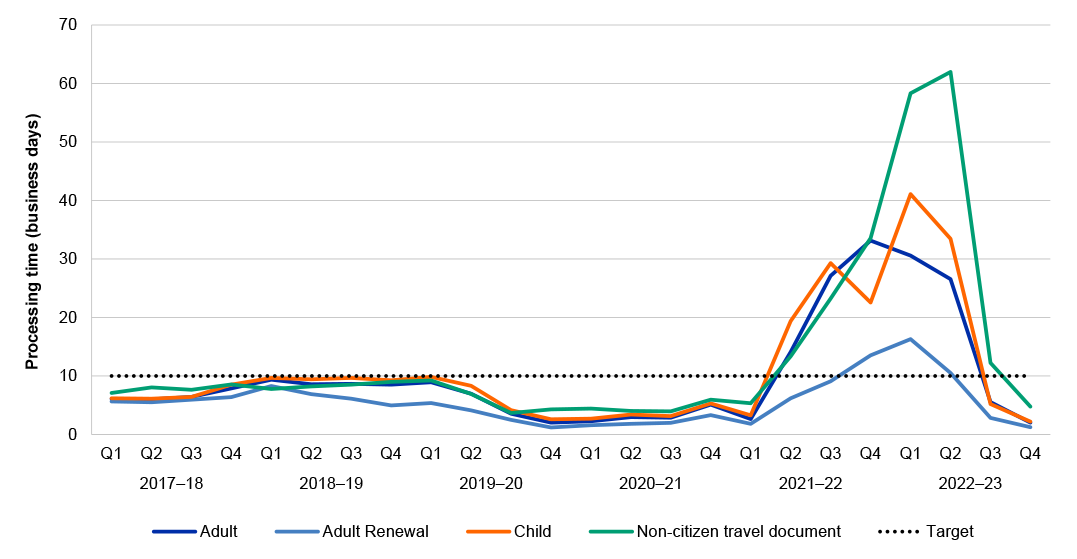

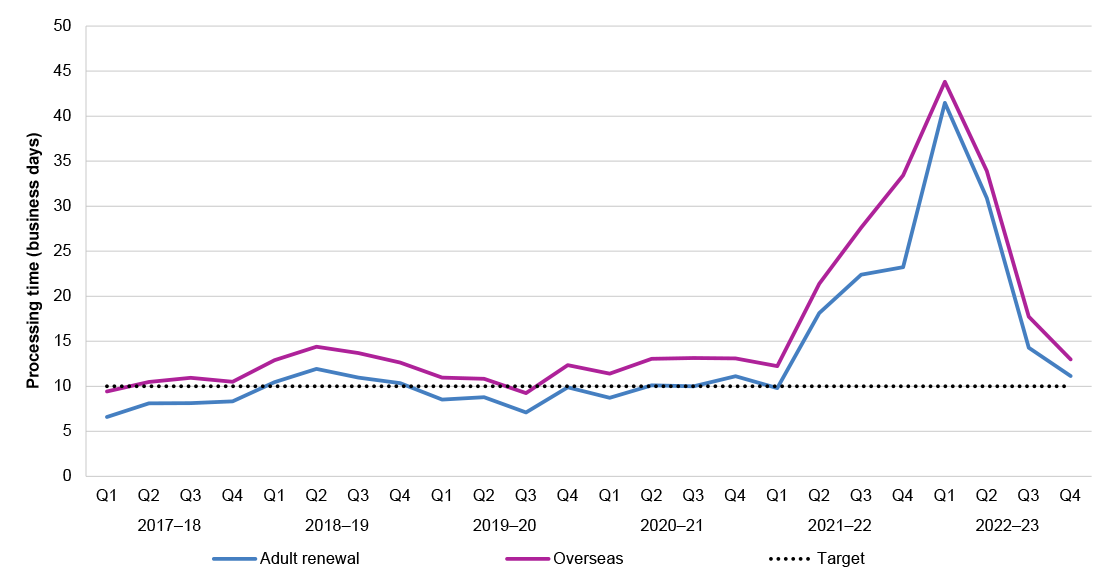

- DFAT has not achieved its target to process 95 per cent of routine passports within 10 business days for three out of the last five financial years. Following the reopening of the border, an increasing proportion of applicants chose to pay an additional fee to have their application processed as a priority within two business days. The department’s performance in processing priority applications has declined over time.

- DFAT’s resource efficiency has declined when considered in terms of the average cost to process passport applications and the average number of passport applications processed per full-time equivalent (FTE) staff member (Australian Public Service (APS) employees plus contractors). Additional staff to process applications once the international border reopened were not engaged and trained in time to avoid a significant processing backlog developing.

Supporting findings

Passport processing arrangements

11. Appropriate performance measures have not been established to enable an assessment of the department’s passport processing efficiency:

- Time efficiency: the department has two targets (one for routine applications and another for priority applications) to demonstrate timeliness of processing that could be used as efficiency proxy measures. Both require improvement so that they measure the turnaround experienced by applicants. The department’s current approach is to calculate the time applications spend in the department’s processing systems (excluding the time it takes for an application to enter the systems as well as the time it takes to provide the passport to an applicant once processing has been completed) and exclude the time an application might spend on ‘hold’.

- Resource efficiency: the department has no performance measures. This situation is at odds with the department previously agreeing to a 2022 internal audit recommendation that it develop efficiency measures for functions that are transactional in nature (such as passport services) that measure the cost of inputs relative to outputs. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.22)

12. Once an application is registered in its processing systems, DFAT is able to capture data that can be used to inform an assessment of its time efficiency in delivery of passport services, although the department relies on manual workarounds when calculating performance using this data. Data is not currently captured for analysis of the time taken from an applicant perspective from when an application is lodged through to the passport being provided to the applicant.

13. Relevant and reliable data is available on resource usage for Australian-based staff in the APO which could be used to measure efficiency. While expenditure information is captured at a department-wide level, a reliable measure on the cost of passport services is not available. In 2021, DFAT commenced the development of an activity-based cost model. The model does not include an apportionment of corporate enabling and overseas costs. (See paragraphs 2.23 to 2.33)

14. DFAT uses two workflow systems for passport processing, an approach the department has long recognised as being inefficient. While DFAT diplomatic and consular missions have access to systems, policies and procedures to support efficient processing, Austrade officials with responsibility for delivery of passport services have not been provided with the same access when delivering the same services. DFAT has not achieved the intended benefits from projects to improve photo quality for overseas passport applicants and automate manually intensive workflow steps. Passport policy and standard operating procedures for processing are available to DFAT staff on a centralised intranet site. (See paragraphs 2.34 to 2.54)

15. The funding arrangements for passport processing are not designed to promote efficiency in the delivery of passport services and are based on outdated assumptions with the result that those arrangements do not support the efficient use of resources. Ministers have agreed that Department of Finance (Finance) and DFAT should revise the passport funding agreement to cover the full costs of passport provision. (See paragraphs 2.55 to 2.64)

16. DFAT does not have appropriate arrangements in place to manage complaints about passport processing. While complaints made via the online portal are captured in a centralised database, other important avenues where complaints may be made (such as the public-facing Passport Enquiries inbox as well as contracted service providers for the lodgement of passport applications and the call centre) are not included. As a result, DFAT does not have a complaint system capable of producing complete and reliable passport complaint data so as to analyse performance and identify opportunities for improvement. (See paragraphs 2.65 to 2.78)

Passport processing efficiency

17. DFAT has not achieved its target to process 95 per cent of routine passports within 10 business days for three out of the last five financial years.

18. The department’s target processing time differs to its advice to applicants on its website to allow a ‘minimum of 6 weeks to receive a passport, no matter where you apply’ because the department’s performance measurement does not capture the period from application lodgement through to the receipt of the passport by the applicant and discounts the time that application processing is on ‘hold’. While the 10 business days internal processing target has not changed, advice to customers on how long they will need to wait to receive a passport was ‘three weeks’ up until October 2021, changing to ‘up to six weeks’ from November 2021 to May 2022 and since June 2022 has been a ‘minimum of six weeks’. The incongruity between the department’s timeliness performance targets and its public messaging reflects that the department’s approach to measuring time efficiency is not customer focused.

19. An increasing proportion of applicants are choosing to pay an additional fee to have their application processed within two business days, resulting in substantial additional passports revenue being received by the Australian Government. A change in methodology for calculation of ‘two business days’ approved by DFAT in February 2020 resulted in more favourable performance results for DFAT against the priority processing target. The change in methodology was not transparently disclosed in its performance statements.

20. DFAT’s processes do not assist applicants to seek refunds in circumstances where priority applications are not processed within two business days. In 2022–23, DFAT refunded $733,224 in priority fees while up to $15.9 million in revenue was retained from applicants who may have been eligible to claim a refund.

21. Processing times for complex applications are not publicly reported or captured by DFAT’s performance measures. While the proportion of complex applications, when compared to total passport applications processed, has remained stable over time, processing times for complex applications have increased from a median of 10 business days in 2017–18 to 46 business days in 2022–23, in excess of the six to eight weeks timeframe communicated to applicants.

22. DFAT may place applications on ‘clock-stopping holds’ which stops an application’s recorded processing time. DFAT guidance states that clock-stopping holds should be used when contact is ‘being attempted’ or ‘has been made with the person or area relevant to the hold’ to gain further information relevant to the application. The department undertakes insufficient analysis of its use of manual holds to identify the factors causing these to occur and opportunities to improve its time efficiency in processing passport applications by reducing how often and for how long applications are placed on hold. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.61)

23. Apart from 2020–21 and, to a lesser extent, 2021–22, the average cost per passport produced has been growing over time (being 23 per cent higher in 2022–23 than it was five years earlier compared with a 15 per cent increase in the wage price index). A higher average cost to produce passports in 2020–21 and 2021–22 reflected the lower number of passports produced rather than a significant increase in costs. Cost growth as passport application demand increased following the re-opening of international borders has been in the areas of supplier expenses and additional processing staff obtained through contractual arrangements (rather than employees).

24. Staff efficiency was steadily improving up until the COVID-19 pandemic. This reflected a consistent and generally slightly increasing number of passports being produced and a slight decline over time in the number of processing staff. The average number of passport applications processed per FTE (employees plus contractors) has not returned to pre-pandemic levels, averaging 384 per FTE per quarter throughout 2022–23, 56 per cent lower than the 865 per FTE achieved on average in eleven quarters before the closure of the international border and corresponding drop in demand for passport services.

25. The timing of the post border reopening increase to processing resources (through contractors) was such that there were insufficient trained and experienced resources available to prevent a large backlog in applications developing from late 2021. The backlog in applications grew considerably over the next year, peaking in September 2022 at 428,750 applications on hand. (See paragraphs 3.62 to 3.89)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.13

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improve its performance measures to include an explicit focus on the time it takes from an applicant perspective from the lodgement of an application through to the receipt or collection of a passport.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.17

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade establish and report on performance measures that address the efficiency with which it uses resources in processing passport applications.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.41

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improve the processing of passport applications by equipping Austrade staff with responsibility for delivery of passport services in overseas locations with the same access to passport systems as is provided to its departmental officers in overseas locations.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 2.77

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improve its complaints handling for passports processing by:

- expanding the capture of complaints data to include all relevant channels including the Passport Enquiries inbox as well as from third-party service providers; and

- recording passport complaints received via any channel in an electronic system capable of producing complaint data that is reliable and complete.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.11

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improve transparency over its passport application processing by improving its systems to expand its published processing time to the number of consecutive business days that applicants can expect their passport to take from application submission to passport receipt.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.23

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade ensure any methodology changes that impact on reported performance, and the rationale for the changes, are explained in reporting.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.28

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade provide refunds of the priority processing fee paid by all applicants where the department does not meet the processing timeframe advertised for those applications.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 3.59

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade analyse its use of manual holds to identify the factors causing these to occur and opportunities to improve its time efficiency in processing passport applications. The department should seek to minimise the number of applications that are placed on hold, and the time they spend on hold.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 9

Paragraph 3.66

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade adopt an activity-based costing approach to reporting on the cost of the department providing passport services.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

26. The proposed report was provided to DFAT, Finance and Austrade. Extracts of the report were also provided to: Australia Postal Corporation (Australia Post), Community and Public Sector Union, Customer Driven Solutions Pty Ltd, Datacom Systems (AU) Pty Ltd, Grosvenor Performance Group Pty Ltd, Mühlbauer ID Services GmbH (Mühlbauer), Serco Citizen Services Pty Ltd, Synergy Group Australia Pty Ltd and UiPath S.R.L. The letters of response that were received for inclusion in the audit report are at Appendix 1. Summary responses, where provided, are included below.

Austrade

Austrade has noted the Australian National Audit Office’s findings.

Australia Post

Australia Post notes that, while the extract of the proposed report provided contains various references to Australia Post, there are no recommendations included for consideration by Australia Post. Should there be aspects of the full and final report that require our review or response, Australia Post representatives are available to assist.

Australia Post recognises the critical importance of an efficient passport services process, including the efficiency of arrangements in place to manage complaints about passport processing. Noting the extract identifies findings related to complaints management, Australia Post will ensure relevant complaints data received by Australia Post is provided to DFAT in compliance with contractual requirements. If complaints data is requested by DFAT that is not required under the existing contract, Australia Post will work with DFAT to identify and implement a mutually agreeable solution.

Mühlbauer

Upon receiving reports from DFAT indicating that an increased number of photos and signatures that had been processed by Mühlbauer’s Image Enhancement software (MBIE) required manual processing, Mühlbauer immediately conducted a detailed analysis of statistical information and test data made available by DFAT and identified three key criteria that negatively affected performance when compared to tests and validation carried out as part of the rollout process. There is a clear correlation between poor quality input photos and increased manual workload.

Mühlbauer has provided DFAT with a detailed report, describing methodology and the details of our findings, alongside with recommendation to mitigate the identified root causes. Mühlbauer stands committed and continues to work with DFAT’s team on adjustments to key processing parameters and machine learning algorithms within the MBIE software, by providing additional training and assisting DFAT with revised guidelines for photographs submitted as part of an applicant’s passport application.

Addressing these key topics should immediately reduce the number of photos requiring manual processing and drastically reduce the workload and processing times.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Performance and impact measurement

Program design

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australian citizens are entitled to be issued with a passport under the Australian Passports Act 2005 (the Passport Act). 6 A passport enables travel across borders (with the necessary visas or entitlements) and within Australia can also act as important proof of identity. Non-citizens may be eligible to apply for other types of travel documents.7

1.2 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is responsible for issuing passports to Australian citizens in line with the Passport Act, with delivery of passport services in Australia and overseas being one of DFAT’s three key outcomes.

1.3 In July 2006, DFAT created the Australian Passport Office (APO or Passport Office) as a separate division to provide passport services. DFAT has offices in each Australian capital city to deliver passport services and works with DFAT diplomatic and consular missions to provide services to Australians located overseas. The Australian Trade and Investment Commission (Austrade) also provides passport services in eleven overseas locations (nine countries) where DFAT does not have a diplomatic or consular presence.8

Passport application process

1.4 The methods by which a customer can apply for a passport depends on the application type9 and whether the applicant lives in Australia or overseas. In 2017, DFAT implemented the Online Passport Application System (OPAS)10, which enabled adult customers to generate applications online for a new passport or renewal. Adults applying online are directed to the digital capture process, which sends data to DFAT systems digitally and generates a short ‘application checklist’ for the customer to print and lodge in person. Child and overseas applicants may use OPAS to generate application forms which the applicant (or their parent or guardian) populates digitally. These forms are not tailored to individual circumstances and no data is delivered to the DFAT systems digitally.

1.5 Applications generated using OPAS must still be lodged in person at a state or territory Passport Office, a participating Australian Postal Corporation (Australia Post) outlet or a diplomatic or consular mission, except in some limited circumstances.11 DFAT advised the ANAO in November 2023 that in 2022–23, 76 per cent of application forms submitted were generated using OPAS. Appendix 3 sets out the passport application process in more detail.

Passport application fees

1.6 Passport and other travel document fees12 are determined by the Australian Passports (Application Fees) Act 2005 (Passport Application Fees Act) and Australian Passports (Application Fees) Determination 2015 (the Passport Fees Determination). These fees are imposed as taxes13, meaning that the passport application fee charged to customers is not related to the cost of issuing the document.14 Passport revenue collected is returned to the Consolidated Revenue Fund. DFAT is funded for delivery of passport services through the Budget process, underpinned by a funding arrangement with the Department of Finance (Finance).

1.7 Figure 1.1 illustrates the quantum of passport services revenue reported by DFAT as well as the department’s reported passport expenses. With the exception of 2020–21 when revenue declined due to the border closure resulting in a significant drop in passport applications, passport revenue collected has exceeded DFAT’s reported ‘actual expenses’ since 2016–17.

Figure 1.1: DFAT’s expenditure on passport services and revenue collected

Note a: DFAT’s reported actual expenses on passport services is presented in the agency resourcing statement in Appendix 3 of its annual report and does not form part of the audited financial statements. DFAT advised the ANAO in September 2023 that the ‘actual expenses’ reflect ‘the budget estimate (per the [Passport Funding Arrangement]) plus/minus no-win no-loss adjustment at year end…we do not reconcile PFA estimate to actual expenditure’.

Note b: Passport services revenue is reported in DFAT’s audited financial statements.

Source: DFAT annual reports.

1.8 DFAT advised the ANAO in November 2023 that:

In periods during 2020-21, up to 40 per cent of passport office staff were redeployed to Services Australia or other functions within DFAT such as consular services, to support the government response to COVID (subject of other ANAO reviews)…These costs were not shifted from the department, as no APS agency seconding staff during COVID had their costs shifted as part of the APS2000 mass-secondment project. Each department continued to cover their own staffing costs.

Demand for passport services

1.9 DFAT’s 2018–19 Annual Report noted a long-term year-on-year increase in demand for passports, with the 2.1 million travel documents issued that financial year being a new record. This represented a 39 per cent increase from the 2008–09 financial year.

1.10 Figure 1.2 sets out demand for passport services, as well as the number of passports issued between July 2017 and June 2023. Demand for passport services was stable in 2017–18 and 2018–19, both in terms of the number of applications submitted and the seasonality of the applications (that is, the number of applications submitted in a particular month). The number of applications lodged in 2017–18 and 2018–19 was 2,059,028 and 2,084,255 respectively (the number of applications submitted in 2018–19 was one per cent higher than 2017–18).

1.11 Beginning in January 2020 travel restriction measures were progressively implemented in response to the emergence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). On 1 February 2020 the Australian Government issued a requirement for Australian citizens, permanent residents and their immediate families returning from China to self-isolate for 14 days. On 24 March 2020 the international border was closed to prevent Australians travelling overseas.15 The international border remained closed until 1 November 2021.16

Figure 1.2: Passport applications lodged and processed from July 2017 to June 2023

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT records.

1.12 Following the closure of the international border, the number of applications lodged dropped from 485,358 applications in quarter 3 2019–20 to 115,939 in quarter 4 2019–20 (Figure 1.2). Average quarterly demand during the border closure remained about three and a half times lower than the average before implementation of border restrictions (151,693 applications per quarter compared to 516,547 applications, respectively). Over the six quarters of border restrictions, 2.2 million fewer passports were issued when compared to the previous six quarters.

1.13 Demand for passports began increasing immediately following the reopening of the international border in November 2021. This was noted in the 2021–22 DFAT Annual Report:

Following Australia’s 1 November 2021 border reopening, the department faced unprecedented demand for passports as Australians started travelling overseas again. The department issued almost 1.5 million passports in 2021–22, about two-and-a-half times the number seen the year before.

1.14 The number of applications lodged in the seven quarters following the reopening of the international border was on average 22 per cent higher than pre-pandemic levels per quarter. The increased demand for services was consistent with the demand modelling conducted by DFAT to predict the number of passport applications that will be submitted in the coming months. After the closure of the international border, this simulated demand model was updated monthly to reflect public health advice, travel advice, COVID-19 trends and other possible influences on consumer sentiment (Figure 1.3). The passports demand modelling predicted as early as December 2020 that the low number of passports lodged in 2020 would result in a ‘pent-up demand surge’ in 2022, providing the department with time to prepare for a sustained increased demand for passport services (Figure 1.3).

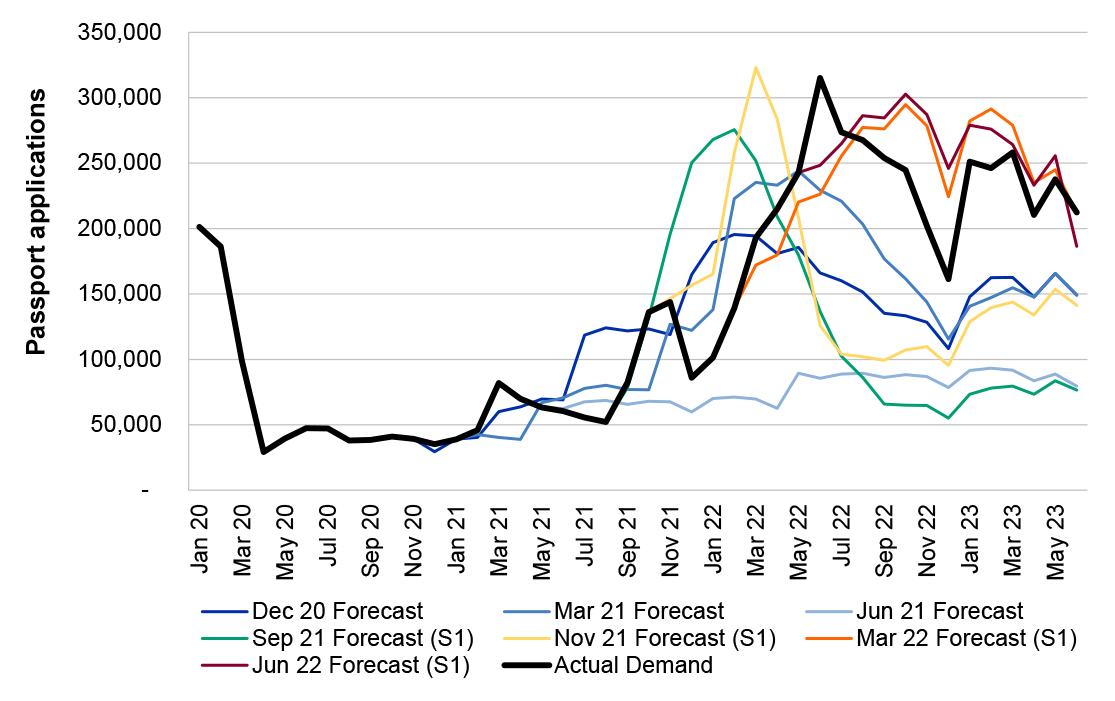

Figure 1.3: Forecast passport demand and actual demand

Note: DFAT advised the ANAO in September 2023 that it transitioned to a scenario-based simulation model to forecast passport demand following the closure of the international border due to changes in traveller behaviour. From September 2021, DFAT generated five possible recovery scenarios to forecast passport demand. The scenario variables lay in the timing and rate of demand growth. The forecasts presented in the figure are of scenario 1, which predicted the highest growth of demand for passport services with an accelerated recovery.

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT data.

1.15 With the exception of a forecast created in June 2021, each simulated demand curve predicted that a spike in demand would occur following the reopening of the international border. The November 2021 forecast indicated that demand following the border reopening would reach a peak of 320,000 applications in March 2022. The prediction of volume was accurate; actual demand reached a peak of 315,141 applications in June 2022.

1.16 In February 2022, the modelling team advised DFAT Executives that:

Four out of five forecast scenarios anticipate demand will exceed pre-pandemic levels for a sustained period in the coming two years. In these periods, applications rates are likely to exceed 10,000 applications per business day. It would be prudent to prepare for a surge from April 2022.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.17 The efficiency of the DFAT’s processing of passport applications is important to the ability of Australian citizens to travel overseas and ensuring the process obtains the most benefit from available resources. Previous ANAO performance audits focused on the passports function were completed in May 201217 and April 2003.18 This performance audit was conducted to provide independent assurance to the Parliament that the processing of passports by DFAT is efficient.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.18 The objective of the audit was to assess the efficiency of DFAT’s delivery of passport services through the Australian Passport Office. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has DFAT put in place efficient processes for the processing of passport applications?

- Is DFAT’s processing of passport applications efficient?

1.19 The scope of the audit examined the volume of passports processed between July 2017 and June 2023. The scope did not include passport fees as they are imposed as taxes (see paragraph 1.6).

1.20 During the conduct of this audit of passport services efficiency, the ANAO observed a number of practices in respect of the conduct of procurement by DFAT through its Australian Passport Office that merited further examination. As a result, the Auditor-General decided to remove the procurement-related sub-criterion from the efficiency audit and to commence a separate audit of whether the procurements DFAT conducts through its Australian Passport Office comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and achieve value for money. That audit is scheduled to table in July 2024.

Audit methodology

1.21 This audit referenced the ANAO’s methodology for auditing efficiency, ANAO Special Considerations for Efficiency Auditing Methodology and Guidance, which is based on a general model for assessing public sector performance. Efficiency is defined as ‘the performance principle relating to the minimisation of inputs employed to deliver the intended outputs in terms of quality, quantity and timing.’19

1.22 The methodology recognises that an examination of efficiency needs to be ‘fit for purpose’ for each entity or subject matter being audited. In most cases, this is likely to include:

- identifying if the audited entity has its own efficiency measures in place;

- identifying the relevant inputs and outputs, as well as the policy outcome(s) being sought;

- determining appropriate performance measures, drawing on data for inputs and outputs;

- determining suitable comparators to benchmark against it, to identify relative efficiency;

- identifying the key operational processes that are used to transform inputs into outputs (or outcomes) and the linkages between these elements; and

- undertaking appropriate audit procedures to understand and account for any material differences in the comparison of measured efficiency.

1.23 Specific audit procedures undertaken included:

- examining DFAT, Austrade and Finance records;

- meetings with key staff;

- analysis of DFAT passport application20, financial and staffing data; and

- observing the processing of applications, including the conduct of passport interviews, passport production processes (including scanning, data verification, signature and image cropping and personalisation of passport booklets) and application assessment at five APO sites and two locations in New Zealand (one DFAT location and one Austrade location).

1.24 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $593,833.

1.25 The team members for this audit were Jocelyn Watts, Joshua Carruthers, Michaelia Liu, Dale Todd, Tracey Bremner and Brian Boyd.

2. Passport processing arrangements

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) has established efficient processes for the processing of passport applications.

Conclusion

Processes are partly in place for the efficient processing of passport applications. The arrangements focus on timeliness of processing with insufficient attention given to resource efficiency. In addition, the department’s approach is not sufficiently customer focused:

- calculations of the time taken to process passport applications do not reflect the full amount of time experienced by citizens from when they lodge their application to when they receive a passport; and

- the department does not centrally capture and analyse all complaints received so as to identify improvement opportunities.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations aimed at improving aspects such as the measurement of time efficiency, a greater focus on resource efficiency, and improved complaints handling and one opportunity for improvement aimed at reducing DFAT’s reliance on manual workarounds in its performance reporting.

2.1 The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity has a duty under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) to govern the entity in a way that promotes the efficient use and management of the public resources for which they are responsible, and to measure and assess the performance of the entity in achieving its purposes.21 The core outcomes set out in the Portfolio Budget Statements for achieving DFAT’s purpose include the provision of timely and responsive passport services.

2.2 Reflecting the PGPA Act obligation for the efficient use and management of resources, the ANAO examined:

- the performance measures DFAT has adopted as well as whether information to apply those measures is being collected;

- the policies, procedures and systems in place to support efficient passport processing;

- funding arrangements; and

- complaints handling arrangements.

Does DFAT have appropriate performance measures to enable an assessment of passport processing efficiency?

Appropriate performance measures have not been established to enable an assessment of the department’s passport processing efficiency:

- Time efficiency: the department has two targets (one for routine applications and another for priority applications) to demonstrate timeliness of processing that could be used as efficiency proxy measures. Both require improvement so that they measure the turnaround experienced by applicants. The department’s current approach is to calculate the time applications spend in the department’s processing systems (excluding the time it takes for an application to enter the systems as well as the time it takes to provide the passport to an applicant once processing has been completed) and exclude the time an application might spend on ‘hold’.

- Resource efficiency: the department has no performance measures. This situation is at odds with the department previously agreeing to a 2022 internal audit recommendation that it develop efficiency measures for functions that are transactional in nature (such as passport services) that measure the cost of input relative to output.

DFAT’s external performance measures

2.3 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 requires that an entity’s corporate plan include details of how the entity’s performance will be measured and assessed through ‘specified performance measures for the entity that meet the requirements of section 16EA’ and ‘specified targets for each of those performance measures for which it is reasonably practicable to set a target’. The performance measures for an entity meet the requirements of subsection 16EA(e) if they include measures of an entity’s efficiency if those things are appropriate measures of an entity’s performance.22 Related Department of Finance (Finance) guidance advises that ‘key activities that are transactional in nature (such as the processing of welfare or grant payments, the operation of call centres or revenue collection functions) lend themselves to efficiency measurement’.23

2.4 The Finance guidance further advises that:

Efficiency is generally measured as the price of producing a unit of output, and is generally expressed as a ratio of inputs to outputs. A process is efficient where the production cost is minimised for a certain quality of output, or outputs are maximised for a given volume of input. In a public sector context, efficiency is generally about obtaining the most benefit from available resources; that is, minimising inputs used to deliver the policy or other outputs in terms of quality, quantity, and timing.24

2.5 In a 2018–19 audit of performance statements the ANAO made the following recommendation to DFAT and three other entities: ‘Entities review their performance measurement and reporting frameworks to develop measures that also provide the Parliament and public with an understanding of their efficiency in delivering their purposes.’ DFAT ‘agreed with qualification’.25 DFAT also agreed to implement a recommendation of a February 2022 internal audit report which recommended it:

Establish efficiency measures which fit the definition as articulated by Finance Guidance. These should generally measure cost of input in comparison to output. The department should concentrate on developing efficiency measures for the functions that are transactional in nature in the first instance, such as the Australian Passport Office. Where this is not possible in the coming performance cycle (i.e. 2022-23), clearly articulate how ‘efficiency proxy’ measures will provide an indication of efficiency over time (for example, processing timeliness measures), and then work towards bona-fide efficiency measures at the earliest opportunity.26

2.6 DFAT’s 2022–23 Corporate Plan contained two performance measures relating to passport services, with associated targets. They were not efficiency measures nor presented as efficiency proxy measures.27 The two performance measures are outlined in Table 2.1, along with the results reported in DFAT’s 2022–23 Annual Report.

Table 2.1: DFAT’s performance measures related to passport services for 2022–23

|

Performance measure |

Targets for 2022–23 (and 2023–24 to 2024–25) |

Reported results for 2022–23 |

|

Effectiveness measures |

||

|

6.1 The department maintains a high standard in processing passports.a |

95 per cent of passports processed within 10 business days. |

Not achieved (61 per cent) |

|

98 per cent of priority passports processed within two business days. |

Not achieved (91 per cent) |

|

|

Output measures |

||

|

6.4 Clients are satisfied with passport services. |

85 per cent satisfaction rate of overall passport service from client survey. |

Achieved (85 per cent) |

Note a: Performance measure 6.1 has been updated in DFAT’s 2023–24 annual report to ‘Australian passports are processed efficiently.’ The associated targets and percentage benchmarks have not changed.

Source: 2022–23 DFAT Corporate Plan and 2022–23 DFAT Annual Report.

2.7 In the absence of an efficiency measure, the two timeliness targets against performance measure 6.1 could provide a partial assessment of passport processing efficiency as proxy measures. These targets have appeared in DFAT’s Corporate Plans since 2016–17 and DFAT has long reported on its passport processing performance in terms of days taken (see Appendix 5 for DFAT’s reported performance since its 1999–2000 Annual Report).

2.8 The appropriateness of the timeliness targets as effectiveness measures and/or efficiency proxy measures is undermined by how DFAT calculates and reports its performance. It is not transparent in the Corporate Plans or Annual Reports that DFAT’s calculation of business days taken is not based on the time elapsed from the customer’s perspective. This is notwithstanding that DFAT has either control over or influence over each step in the process of obtaining an Australian passport. For example, DFAT contracted the Australian Postal Corporation (Australia Post) to provide passport application lodgement services nationally at a cost of $357.4 million between 1 July 2017 and 30 June 2024, in addition to its passport postage services.

2.9 The start and end points that DFAT uses in its calculation of processing time reported against performance measure 6.1 differs based on where a customer lodges their application, the location where the passport is printed and whether the applicant elects to collect the passport or receive it by mail. Appendix 6 outlines the different measures of processing time based on these factors.

2.10 For the majority of applications reported against performance measure 6.128, DFAT reports the time taken from the registration of the application in the main computerised Passport Issue and Control System (PICS) through to the final quality assurance of the completed passport booklet or receipt of the passport by the state and territory office. Time taken is not measured, for example, from the point of a person lodging an application at Australia Post through to passport despatch to the applicant or receipt by the applicant. This is even though, under the relevant contract, data is required to be collected on the time spent by customers waiting for an appointment at an Australia Post outlet and the time between lodgement by a customer at Australia Post to its delivery to a state or territory office for processing.

2.11 Further, not every business day between the start and end point is necessarily included in DFAT’s calculation of processing time. DFAT excludes the time an application is placed on a clock-stopping hold in the system. There are many reasons an application may be placed on a clock-stopping hold by processing officers, such as if additional information is required from a customer, and this pauses the processing clock (that is, the time counted towards DFAT’s performance targets). Eight per cent of routine passport applications processed in 2022–23 were placed on a clock-stopping hold in the system at least once for a median duration of 2.8 days per application and an average duration of 5.3 days (see further ANAO analysis at paragraph 3.39 to 3.58). To reduce hold times, DFAT can influence customer compliance through its information products, form design and its contracts with Australia Post, which require staff to check during application lodgement that the form has been completed correctly and that the photograph meets the Commonwealth’s standards.

2.12 Greater transparency in service performance perceived by the applicant could be achieved by adequately measuring the full range of processing steps. The incongruity between DFAT’s targets and its customer messaging is discussed at paragraphs 3.5 to 3.11 and the ANAO’s analysis of the affect of clock-stopping holds on DFAT’s time efficiency in processing passport applications is outlined at paragraphs 3.39 to 3.59.

Recommendation no.1

2.13 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improve its performance measures to include an explicit focus on the time it takes from an applicant perspective from the lodgement of an application by the applicant through to the receipt or collection of a passport.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

2.14 DFAT accepts this recommendation.

2.15 Among other things, the department will explore publishing Australia Post delivery timeframes alongside the processing timeframes currently published.

DFAT’s internal performance measures

2.16 DFAT has not established internal performance measures that enable an assessment of passport processing efficiency. DFAT reports internally each week against its external performance measures relating to passport services. In terms of output volumes, as of August 2023, DFAT has established output targets for each step of passport processing based on resource availability, staff composition, skills, competencies and expected demand. State and territory DFAT officers are responsible for monitoring output daily and ensuring these are within the expected range.29

Recommendation no.2

2.17 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade establish and report on performance measures that address the efficiency with which it uses resources in processing passport applications.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

2.18 DFAT accepts this recommendation.

2.19 The department is considering the suitability and application of an efficiency measure as part of the ANAO’s audit of DFAT’s 2023–24 Annual Performance Statements.

Austrade’s performance measures

2.20 In a 2016–17 audit of performance statements, the ANAO directed the following recommendation to the Australian Trade and Investment Commission (Austrade) and three other entities: ‘Entities review their performance measurement and reporting frameworks to develop measures that provide the Parliament and public with an understanding of their efficiency in delivering their purpose/s.’ Austrade ‘agreed’.30

2.21 Austrade’s 2022–23 corporate plan contains one performance measure related to its delivery of passport services to Australians overseas: ‘Effective delivery of consular and passport services to Australians overseas’.31 This performance measure (and associated targets) is set by the memorandum of understanding (MOU) between DFAT and Austrade on the delivery of passport services. There are no efficiency measures in Austrade’s corporate plan related to the delivery of passport services, although Austrade advised the ANAO in November 2023 that the accuracy rate is being used ‘as a proxy efficiency measure’.32

2.22 The MOU also contains other timeliness indicators for application scanning, financial reconciliation and the forwarding of fees collected. These could be used as proxy efficiency measures. From the systems it maintains, DFAT provides information to Austrade monthly on Austrade’s performance against the indicators in the MOU. Austrade officers responsible for passport processing do not have access to performance reporting in real time as DFAT has not provided Austrade access to Atlas, one of the key passport processing systems (refer to paragraph 2.39 for more information).

Does DFAT collect relevant and reliable information on its passport processing efficiency?

Once an application is registered in its processing systems, DFAT is able to capture data that can be used to inform an assessment of its time efficiency in delivery of passport services, although the department relies on manual workarounds when calculating performance using this data. Data is not currently captured for analysis of the time taken from an applicant perspective from when an application is lodged through to the passport being provided to the applicant.

Relevant and reliable data is available on resource usage for Australian-based staff in the Australian Passport Office (APO or Passport Office) which could be used to measure efficiency. While expenditure information is captured at a department-wide level, a reliable measure on the cost of passport services is not available. In 2021, DFAT commenced the development of an activity-based cost model. The model does not include an apportionment of corporate enabling and overseas costs.

Collection of input and output data

2.23 DFAT collects data on the number of domestic staff responsible for delivery of passport services. Data is available from PeopleSoft, which is DFAT’s main human resources management system. Data extracted from Peoplesoft is suitable to determine the number of domestic (Australian) staff delivering passport services from April 2021, but does not enable an assessment of the number of overseas staff delivering passport services or corporate enabling staff supporting the delivery of passport services. Expenditure information on passport services is captured within DFAT’s Financial Management Information System.

2.24 DFAT collects data on the number of passports issued and the timeframe taken for application processing once the application is in its processing system. Data is available from PICS, which is the core passport processing system and ‘the source of truth for passports data’. PICS has suitable functionality for registering passport application details and calculating passport processing time for different types of travel documents once an application is captured within the department’s processing systems.

2.25 Data is not currently available to enable a calculation of time efficiency from an applicant perspective (that is, from when an application is lodged through to when the passport is received). Some information is collected, or should be available, to DFAT on Australia Post’s performance against the Passport Application Lodgement Services contract which could be used to provide greater transparency in service performance to applicants. This includes time spent by customers waiting for an appointment at an Australia Post outlet and the time an application spends in the mail between lodgement by a customer to the time it is delivered to the APO. This is of particular relevance to measuring the customer experience, as 92 per cent of passports processed between July 2017 and June 2023 were submitted at an Australia Post outlet.

Reliability of data

Passports processed

2.26 PICS calculates the turnaround timeframe for each travel document application, as well as the proportion of routine passports issued within ten business days and the proportion of priority passports issued within two business days. DFAT approved changes to the calculation of priority application turnaround benchmarks in February 2020. DFAT did not implement these changes in PICS, instead relying on manual workarounds in an Excel spreadsheet to recalculate the number of priority applications that passed the new definition of a two business day turnaround.33

2.27 ANAO analysis indicates that between July 2017 and June 2023 there were 83,858 form numbers duplicated in PICS reporting used by DFAT for reporting its progress against performance measure 6.1 (Table 2.1). DFAT’s methodology control documentation notes that, for annual reporting cycle 2022–23, ‘Where there are duplicate records of the same form number, the record with the longest processing time is maintained. Other records are removed.’

2.28 Performance measure methodologies should be designed in a way to produce accurate data, be applied consistently and be able to be substantiated.34 Manual workarounds, such as re-calculation of system generated results or manual removal of duplicates, increase the risk that performance information produced and reported is not reliable.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.29 DFAT reduce its reliance on manual workarounds in its calculation of results against performance measure 6.1 to reduce the risk that performance information reported is not reliable. |

Expenditure information

2.30 While activity-based costing has existed since the 1980s35, until 2021 DFAT did not have an activity-based costing model for passport services. At an agreed cost of up to $436,700 (including GST) DFAT engaged Synergy Group Australia Pty Ltd (Synergy) in February 202136 to produce an activity-based cost model. A framework from Synergy outlined that:

Currently a framework to achieve cost transparency is absent within the APO. This absence reduces the APO’s ability to have clear visibility of the activity costs that contribute to the portfolio’s delivery of services. A lack of operational transparency has the potential to results in inaccuracies and inefficiencies. This Framework seeks to define consistent assumptions and outline the APO’s approach to support management reporting and decision making.

The purpose of this Framework (alongside an activity and a service catalogue) is to provide a single and holistic source of truth outlining a structured approach, methodology and set of assumptions used to cost services and activities. This will help identify funding shortfalls (surplus) in relation to the Passport Funding Agreement (PFA) and streamline the internal reporting process.

2.31 The approach to the market did not include provision for the successful tenderer to be re-engaged to refresh the cost base of the model that was developed as it was planned that a team of full-time internal employees would contribute to the development and maintenance of the cost model. Instead, through a direct source procurement, in September 2022 DFAT engaged Synergy at a cost of $87,890 (including GST) to ‘undertake a one-off post implementation refresh’ of the activity-based costing model for the APO. The scope of services included updating the cost base from 2020–21 to 2021–22.37 The value of this additional contract was increased in February 2023 to $114,084.30 (including GST). A second amendment was made on the same day in February 2023 to increase the contract value to $251,584.30 for ‘additional services’ to update the cost base to 2022–23.38

2.32 While the model provides DFAT a tool for calculating the average cost per passport, and for analysing costs, the data generated by the model has not been used by the department to monitor its efficiency or as the basis for its public reporting on passport services expenditure. For example, in its 2021–22 annual report the department reported passport program expenses of $267.5 million, 68 per cent higher than the $159.6 million identified by its activity-based costing model. This reflects, in part, that the department’s model is not full activity-based costing as it does not include an apportionment of corporate enabling and overseas costs.

2.33 DFAT advised the ANAO in November 2023 that the software that supports the costing model was no longer supported by the department and ‘DFAT plans to convert the ClearCost model into an Excel workbook to support the cost model being managed and updated by APS officers.’ This approach by the department was at odds with the approach it took at the time of the procurement. All three tenderers who responded to the Request for Quote in October 2020 offered an excel-based solution. Synergy’s quote contained both an excel and a ClearCost option. DFAT selected Synergy without specifying in the approval minute or in the contract which option it had chosen. During the course of the engagement with Synergy, DFAT proceeded with the ClearCost based model and separately procured ClearCost subscription services at a cost of $59,950 from June 2021 to June 2024.

Do DFAT’s systems, policies and procedures support efficient processing of passport applications?

DFAT uses two workflow systems for passport processing, an approach the department has long recognised as being inefficient. While DFAT diplomatic and consular missions have access to systems, policies and procedures to support efficient processing, Austrade officials with responsibility for delivery of passport services have not been provided with the same access when delivering the same services. DFAT has not achieved the intended benefits from projects to improve photo quality for overseas passport applicants and projects to automate manually intensive workflow steps. Passport policy and standard operating procedures for processing are available to DFAT staff on a centralised intranet site.

Systems

2.34 DFAT uses different systems to process applications and authorise the issue of passports.

- Delta: used by processing staff to process paper application forms including paper forms generated online for clients overseas and all child applications. Delta was first implemented between 1998 and 2000.39

- Atlas: used by processing staff to process adult (checklist40) passport applications lodged in Australia and to view client records. Atlas was first implemented in June 2018 and was one of the deliverables of the Passport Redevelopment Program.

- Travel Document and Related Document Issuance System (TARDIS): used as the offshore system for Australian travel document issuance (including emergency passports).

2.35 While most passport applications are reviewed individually by a processing officer to assess an applicant’s citizenship, identity and eligibility, a proportion of applications may bypass the assessment process on a risk basis and be issued by bulk approval or with reduced checks. For example, DFAT’s weekly reporting between 5 June 2023 to 30 June 2023 indicates that there were 215,437 applications assessed in this time period, 103,894 (48 per cent) were finalised in Delta, 73,659 (34 per cent) were finalised through bulk approval processes or with reduced checks in Atlas and Delta and 37,884 applications (20 per cent) were finalised in Atlas.

Decommissioning legacy systems

2.36 In the 2010–11 Budget, DFAT was provided with $100.8 million over six years to replace the existing passport IT system (the project known as the Passport Redevelopment Program), noting that this measure would ‘return efficiencies’ in later years. These targeted efficiencies were reliant (in part) on decommissioning of legacy systems including Delta. DFAT’s 2018–19 Portfolio Budget Submission stated that this saving was to be deferred to 2020 to allow for development testing of new replacement systems.

2.37 Decommissioning of Delta was also identified in a September 2018 business case as being necessary to ‘remove inefficiencies and risks from managing multiple passport systems.’ Key ‘inefficiencies’ identified by DFAT were maintenance of parallel passport policy and standard operating procedures for paper application forms and digital capture processes, maintenance of parallel versions of training materials, allocation of resources to support and maintain legacy systems (at the same time as supporting maintenance of new systems) and complexity of development activities as a result of maintaining two workflow systems.

2.38 As of November 2023, DFAT uses both Delta and Atlas to process passport applications and has not addressed the stated inefficiencies. Planned improvements to Atlas and the Online Passport Application System, such as digital capture of child and overseas applications, have not progressed.41A training environment for new processing officers is also not available in Atlas (meaning that new processing officers onboarded to meet increased passport demand in 2022–23 were instead trained in Delta). According to a March 2023 ‘Passport Blueprint Project’, DFAT plans to decommission both Atlas and Delta in 2026 following a period of ‘core system uplift and investment in new technologies.’

Overseas processing

2.39 DFAT and Austrade staff at overseas posts undertake passport interviews, as well as application scanning and data input.42 Posts log on and off multiple systems when performing lodgement tasks and conducting checks and processes. These include accessing PICS to check applicant details, TARDIS to conduct lost and stolen checks, also TARDIS to input applicant information, TARDIS to scan photos and signatures and ImageWeb to review previous passports. DFAT’s own analysis indicated that use of multiple systems was ‘inefficient, duplicates effort and is a time-consuming process.’ To address these ‘inefficiencies’, DFAT approved a project to provide diplomatic and consular missions with access to Atlas in November 2018.

2.40 While DFAT posts were equipped with access to Atlas throughout 2019, Austrade officials delivering passport services have not been provided with the same access (with the exception of one Austrade location that has access to DFAT systems). Austrade advised the ANAO in August 2023 that without access to Atlas ‘Austrade staff are still trying to piece information together or have to rely on supervising missions or overseas support43 to upload or provide guidance.’

Recommendation no.3

2.41 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improve the processing of passport applications by equipping Australian Trade and Investment Commission staff with responsibility for delivery of passport services in overseas locations with the same access to passport systems as is provided to its departmental officers in overseas locations.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

2.42 DFAT accepts this recommendation.

2.43 The department is considering how Austrade staff could be provided with additional access to passport systems in overseas locations, noting significant changes to systems, access permissions and policy may be required.

2.44 DFAT has also pursued different system upgrades to improve its efficiency in processing overseas applications. A recurring issue for overseas applicants is accessibility of suitable overseas photo providers.44

2.45 Between October 2018 and January 2022 DFAT implemented a mobile capture application (referenced internally as ‘Atlas Mobile Capture’ or ‘AMC’) for overseas posts to digitally capture a client’s face and signature. The initial business case outlined benefits of introducing a mobile capture application, including that ‘the new process will eliminate issues regarding poor photo quality derived from scanning photos into the system or from clients obtaining poor quality photos from overseas suppliers.’ While the risk for the project was assessed as low in October 2018, it was discontinued in January 2022 following a review by Grosvenor Performance Group Pty Ltd (Grosvenor)45 which made findings about the project planning and implementation.

- The original purpose and business problem behind the development of the mobile capture application was not agreed. Feedback provided noted that the ‘AMC sounds like a solution looking for a problem’.

- The application met the original requirements of the request for quote, but these requirements were not reflective of the business needs.

- The project included limited engagement, consultation and testing with end-users resulting in a solution considered not fit for purpose. The most common issues reported were posts being unable to take compliant passport photos through bullet-proof glass, not having the correct lighting levels or having insufficient space to take photos. For example, end-users noted that:

- ‘the use case when it was originally developed was flawed, it wasn’t tested with overseas posts to check if it actually met their needs.’

- ‘the auto-flash on the phones can’t be turned off and it makes the photos unacceptable’; and

- ‘the post does not provide adequate space for photo shooting.’

- Despite sufficient guidance and training material, two thirds of posts did not use the mobile capture application.

Automation

2.46 An APO Automation Strategy was endorsed by DFAT in January 2019. The purported benefits of automation set out in the strategy were reduction of costs, reduced work effort for passport processing and improved staff participation, motivation and career path development. The strategy recognised that while automation is already used in the APO’s systems46, there were opportunities in the short-term for greater efficiency through automation.

2.47 In March 2022, the APO briefed the DFAT Audit Committee that one of the ‘levers’ to increase capacity and manage demand following the re-opening of the international border was system improvement (specifically automation).47 The briefing set out that automation work had begun on the design and development of data verification through robotic processing automation48 as customer applications are scanned (to be implemented in April 2022) and automatic cropping, background removal and image enhancement of photo images (to be implemented in July 2022).

2.48 These recent automation projects have not reduced work effort required to process passports, decreased cost or achieved greater efficiency in passport processing.

- A contract with UiPath S.R.L (UiPath) for improved data capture technology was signed in November 2021. The intended benefits of this project were ‘improved data integrity, accuracy and efficiency in our capture and verification processes…’ The software was not implemented into DFAT’s workflow process and the project was terminated in November 2022. This means that DFAT presently relies on its employees to verify that items have been scanned correctly. DFAT advised the ANAO in November 2023 that it paid UiPath $2.7 million for the delivery of its software.49

- Automatic cropping software from Mühlbauer ID Services GmbH was implemented in workflow processing in September 2022 as part of the roll-out of the new series (R Series) of passport.50 Analysis undertaken by DFAT in November 2023 indicates that the number of photos and signatures requiring re-cropping has increased and that 50 per cent of images cropped using the software are failed, requiring manual cropping by a second person. 51 This has resulted in extended processing times and the cost of rework due to incorrect cropping or image background removal was estimated by DFAT to be $6.3 million (62.5 FTE).

2.49 An increasing proportion of applications are being issued through bulk approval processes or with reduced checks. DFAT has also considered implementing automatic approval of some adult renewal applications. Draft advice from the Australian Government Solicitor (AGS) in February 2019 (which the department did not have finalised52) set out that:

There is a reasonable argument that s47 of the Passports Act provides scope to achieve an outcome under which using specified technological methods results in specified outcomes (including the making of simple decisions) for the purposes of the Act. However, while this scope exists, there is nothing in the current terms of the Passports Determination indicating that the process of using the technological methods prescribed for the purposes of s47(1)(a) is intended to involve or result in the making of a decision having effect for the purposes of the Passports Act…While we think the Passports Act would permit the making of a determination that specified automated decision-making processes to meet the requirements of s 8 of the Act, we think there is real doubt that the Passports Determination as presently worded achieves this.

2.50 In November 2023, DFAT advised the ANAO that it was not currently working on any changes to the automation decision making rules for adult renewals.

Passport modernisation

2.51 Australia is one of three countries in the Passport Six (P6) with no universal digital passport application capability, as illustrated by Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Comparison of P6 nations’ digital passport capabilities

|

|

Australia |

Canada |

Ireland |

New Zealand |

UK |

USA |

|

Digital photograph |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Digital lodgement |

✘a |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Integration with national digital identity |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Online payment |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

Note a: Online lodgement using a digital photo is only available at overseas locations in exceptional circumstances such as natural disaster, crisis, living in a war zone or ongoing medical reasons. This was first introduced in September 2021 to assist passport application in areas affected by Covid-19.

Source: Australian, Canadian, Irish, New Zealand, UK and USA passport websites.

2.52 Under the National Identity Proofing Guidelines, in-person interaction is a requirement for the highest level of identity assurance.53 This is the standard on which DFAT bases its requirements for sighting original personal identity documents in person. The National Identity Proofing Guidelines also state that:

However developments in biometrics, mobile and other technology are continually improving the integrity of online or remote processes for identity proofing. AGD will continue to monitor these developments to determine whether in future this could offer government agencies with a viable alternative method for remote identity proofing with an equivalent ‘gold standard’ level of assurance.

2.53 APO’s Passport Modernisation section is focusing on a digital application solution that will enable digital photographs, digital lodgement and online payment. In November 2023, DFAT advised the ANAO that:

To meet Level of Assurance 4 under the National Identity Proofing Guidelines, an in-person interaction is required when establishing identity, not for subsequent confirmations of that identity (that is, passport renewals). This approach is being captured in plans for moving passports to a digital solution.

Policies, procedures and guidance

2.54 Passport policy and procedures are available to DFAT officers on an internal intranet site (COMPASS) which aims to provide a ‘single source of truth for APO staff for policy and all resources that they need to process travel document applications.’ There are thirty chapters of passport policy to support decision-making, standard operating procedures which provide detailed guidance to processing officers on each stage of the passport process (i.e. capture, assess, personalise and despatch) and standard email, letter and file note templates and forms.

Do funding arrangements for passport processing support the efficient use of resources?

The funding arrangements for passport processing are not designed to promote efficiency in the delivery of passport services and are based on outdated assumptions with the result that those arrangements do not support the efficient use of resources. Ministers have agreed that Finance and DFAT should revise the passport funding agreement to cover the full costs of passport provision.

2.55 DFAT and Finance agreed the Passport Services Funding Arrangement in November 2016. The funding arrangement was to be a ‘true and full-cost model’ for the global delivery of passport services.

2.56 The passport services funding model has fixed and variable components. Variable funding is adjusted to reflect actual movements in workload drivers, being the number of passports issued and changing supplier costs. As part of an annual funding model reconciliation, any movements in funding earned are recognised as adjustments to Revenue from Government in the current financial year.

Costing assumptions

2.57 Before 2016, the funding agreement was reviewed by Finance and DFAT every three years to reflect the actual costs of production and detailed benchmarking of staff requirements. Ministers agreed to extend the funding arrangement indefinitely in 2016 agreeing to accept the risk that indexation less the efficiency dividend may erode the cost base faster than procurement or technology could deliver offsetting savings.

2.58 The arrangement does not have a focus on promoting the efficient use of resources in DFAT’s delivery of passport services.

2.59 The assumptions on which the funding model is based on have become outdated due to changes in passport services delivery.

- A new series of passport (R Series) was released in September 2022. Supplier costs have not been reviewed and updated to reflect that wallets and hint books are no longer produced as a result of the R Series.

- The number of domestic service delivery staff and the breakdown between APS staff and contractors has changed over time above the ceiling set out in the arrangement (refer to paragraph 3.69 to 3.70 and Figure 3.5).

- New business structures within DFAT are not reflected in the agreed staffing profile. For example, the workload management team, service recovery team and in-house call centre staff are not included in DFAT’s staffing profile under the current funding arrangement.

- Funding for call centre services was based on Services Australia costs. As of May 2022, a third-party service provider (Datacom Systems (AU) Pty Ltd (Datacom)) provides call centre services on behalf of DFAT (with different charges).

2.60 Though the funding arrangement was intended to be a ‘full-cost model’, DFAT received supplementation in the 2023–24 Budget of $57.5 million over three years to support the costs associated with increased demand for passport services not covered by the existing funding arrangement ($54 million was incurred in 2022–23 financial year). The $57.5 million was comprised of $35.2 million for additional production and call centre staff (Serco Citizen Services Pty Ltd and Datacom), $11.6 million related to additional information and communications technology expenditure and $10.6 million related to additional property. Ministers also agreed that DFAT and Finance should revise the funding agreement to cover ‘full costs of passport provision’.

2.61 The funding agreement does not include any provisions relating to how DFAT procures goods and services through contractual arrangements. DFAT is required to comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. In November 2023, Finance advised the ANAO that:

We note that non-corporate Commonwealth entities such as DFAT are required to observe the CPRs, including the core rule of value for money, and the overarching requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 under which the rules are made, to ensure that public resources are used in the most efficient, effective, ethical and economic manner. We support the reiteration of these requirements in the passport funding agreement. Finance provides a range of guidance to support compliance with the CPRs and welcomes the reiteration of or cross reference to relevant obligations, including achieving value for money.

No-win no-loss arrangement

2.62 The 2016 funding agreement includes a no-win no-loss arrangement about supplier costs. Where total supplier costs (excluding changes attributable to changes in passport processing volume) increase or decrease by more than $3 million in a single year, or by more than $4 million over two years, the quantum of budget funding provided to DFAT is adjusted.

2.63 Passport ‘supplier costs’ are defined in the Passport Services Funding Arrangement as including costs for passport interviews and application lodgement services (Australia Post), passport booklet costs (Note Printing Australia) and passport postage. There are other costs assigned to be paid to suppliers that are not subject to the no-win no-loss clause, such as paper application forms, freight costs and mail sorting services.