Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Effectiveness of the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman’s Regulatory Functions

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman (the OFWO) regulates approximately one million businesses and 13 million workers under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Fair Work Act).

- Since July 2022, the OFWO has made changes to its strategic direction and operations in response to changes to legislation and revisions to its budget. The OFWO uses a range of compliance and enforcement activities and tools.

- The audit examined the effectiveness of the OFWO’s exercise of its regulatory functions.

Key facts

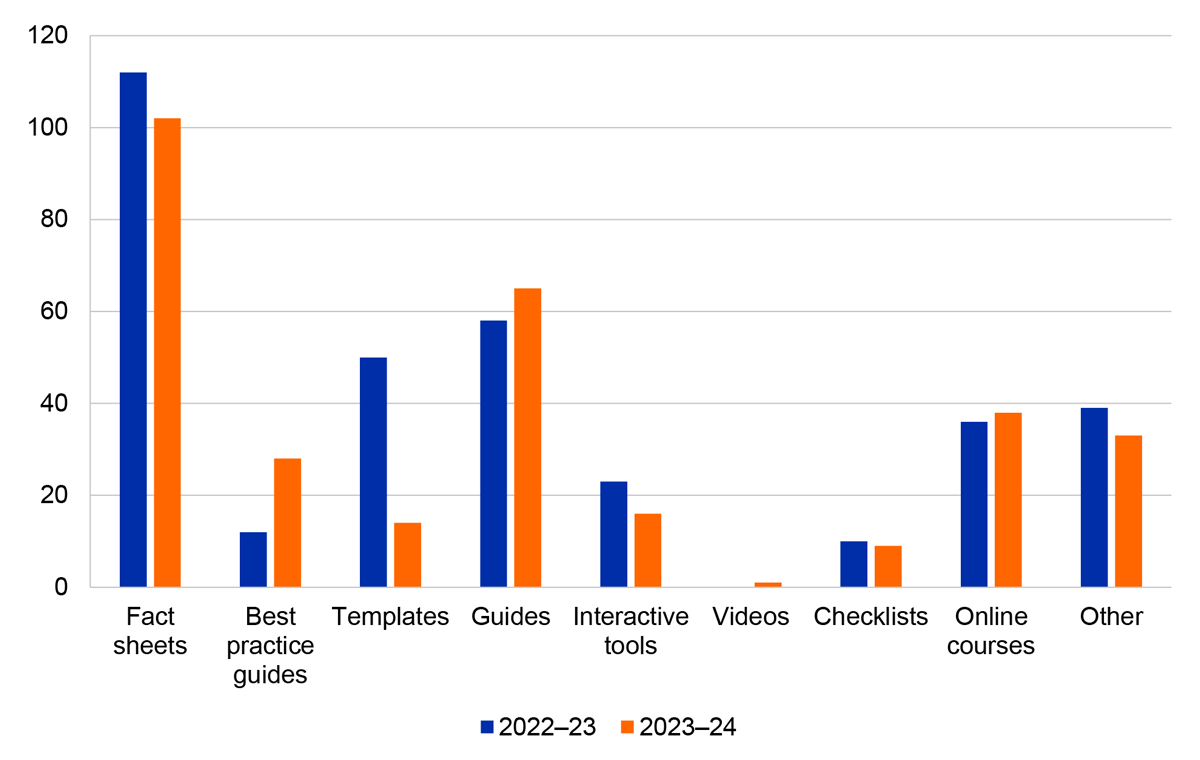

- In 2023–24 there were over 300 education tools and resources maintained and published by the OFWO.

- In 2023–24 approximately 16,440 enquiries were classified as formal requests for assistance. This represents approximately five per cent of total enquiries received.

- The proactive investigation caseload in 2023–24 was 1,329. This is approximately 20 per cent of the total investigation caseload for the OFWO.

What did we find?

- The OFWO is largely effective in the exercise of its regulatory functions.

- The OFWO has established largely fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support the effective management of compliance with the Fair Work Act.

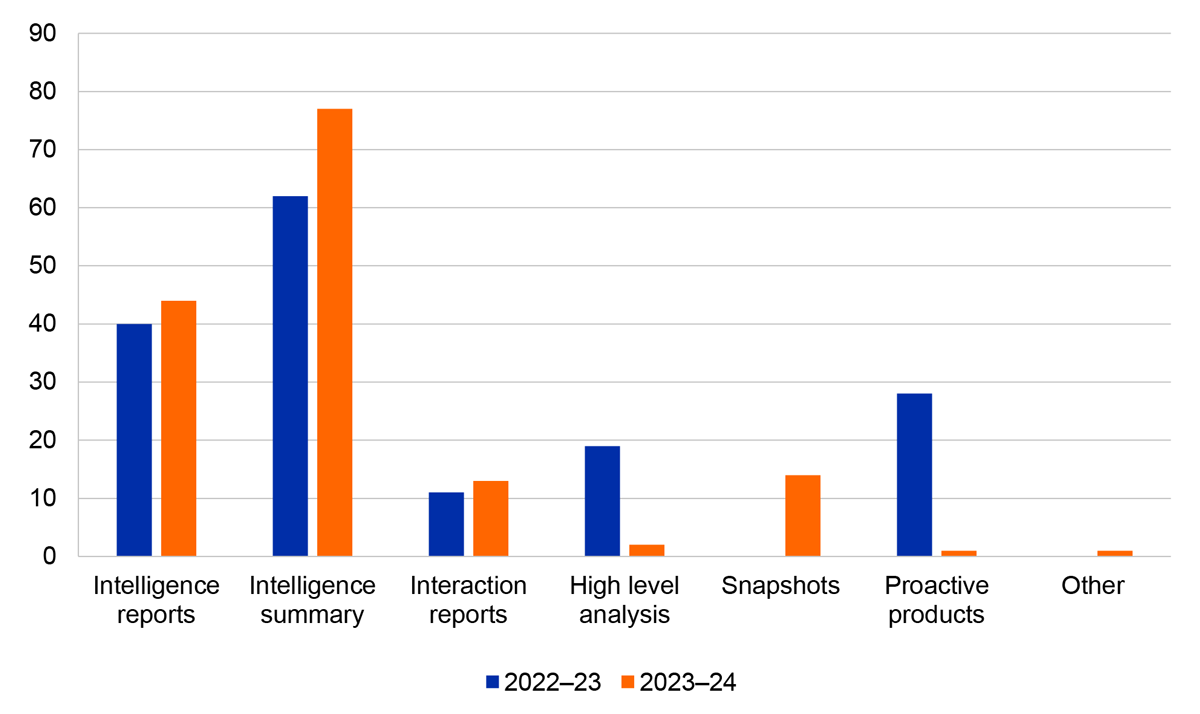

- The OFWO’s arrangements to encourage voluntary compliance and detect

non-compliance with the Fair Work Act are largely effective. - The OFWO’s arrangements to enforce compliance with the Fair Work Act are largely effective.

What did we recommend?

- There were three recommendations to the OFWO aimed at: delivering a framework for the implementation and monitoring of regulatory priority areas; ensuring governance bodies perform strategic oversight and consider the efficiency and effectiveness of regulatory activities; and ensuring there is adequate documentation, review and quality assurance of investigations.

- The OFWO agreed to all three recommendations.

310,000

number of phone or online enquiries received by the OFWO in 2023–24.

3,256

requests for assistance referred for investigation in 2023–24.

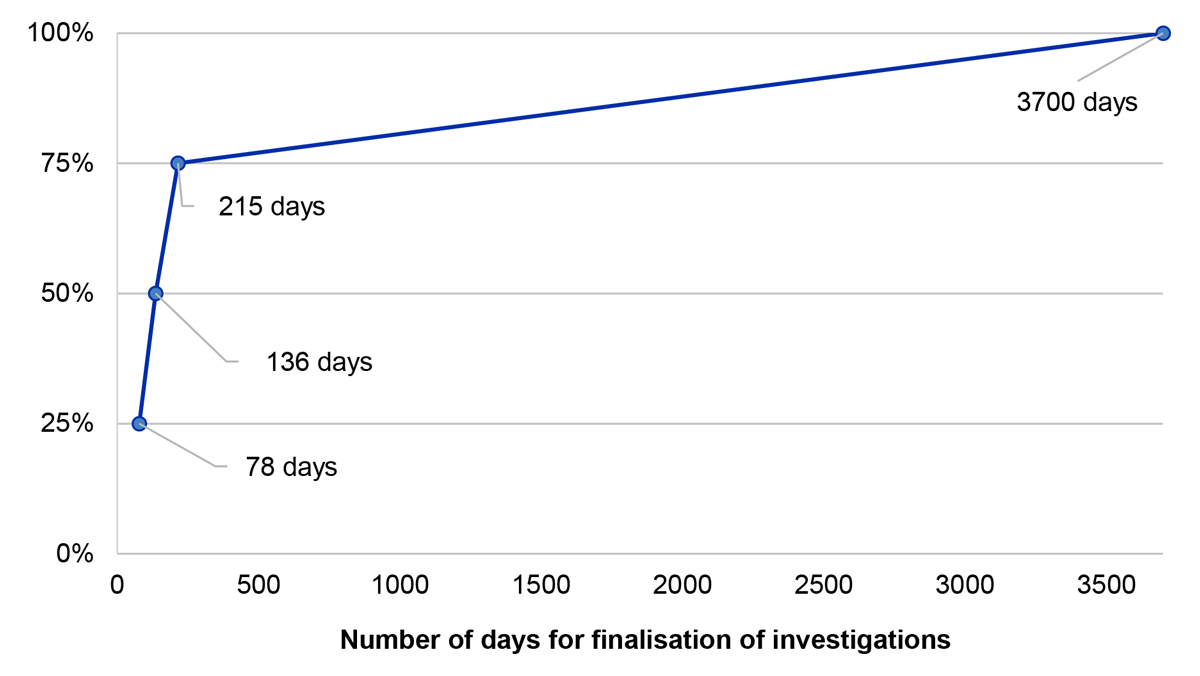

215 days

to finalise 75 per cent of investigations closed between July 2022 and September 2024.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman (the OFWO) was established on 1 July 2009 as an independent statutory office created by the Fair Work Act 2009 (the Fair Work Act) to promote compliance with workplace relations through advice, education and, where necessary, enforcement.1

2. The OFWO regulates all businesses and workers covered by the Fair Work Act. This represents approximately one million employing businesses and around 13 million workers. In 2023–24 the OFWO reported that it recovered $473 million in unpaid wages and entitlements for nearly 160,000 employees, of which $333 million was recovered from the large corporates sector.2

3. The Fair Work Ombudsman is the accountable authority of the OFWO. The Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations sets government policies and objectives relevant to the OFWO in carrying out its statutory functions as a regulator.3 Since July 2022, there have been legislative amendments to the Fair Work Act, including changes to the protection and entitlements of employees and additional responsibilities and funding for the OFWO. This included the OFWO assuming responsibility for the regulation of the Fair Work Act for the commercial building and construction industry and the ability to investigate allegations related to the prohibition of workplace sexual harassment.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The OFWO is the national workplace relations regulator. Its functions include promoting and monitoring compliance with workplace laws, inquiring into and investigating breaches of the Fair Work Act and taking appropriate enforcement action. Since July 2022, the OFWO has made changes to its approach and operations in response to: the expansion of the coverage of the Fair Work Act; implementation of the recommendations resulting from an external review; and revisions to its budget. This audit was conducted to provide assurance to Parliament that the OFWO is exercising its regulatory functions effectively.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman’s exercise of its regulatory functions.

6. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has the OFWO established fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support the effective management of compliance with the Fair Work Act?

- Are the OFWO’s arrangements to encourage voluntary compliance and detect non-compliance with the Fair Work Act effective?

- Are the OFWO’s arrangements to enforce compliance with the Fair Work Act effective?

Conclusion

7. The OFWO is largely effective in the exercise of its regulatory functions. There are opportunities for it to improve its effectiveness by improving strategic oversight of its regulatory objectives and outcomes, establishing frameworks for implementing and monitoring of regulatory priority areas and activities, and measuring the efficiency and effectiveness of its regulation.

8. The OFWO has established largely fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support the effective management of compliance with the Fair Work Act. The OFWO developed compliance strategies that reflected ministerial Statements of Expectations. The compliance strategies were partly risk-based and not fully integrated into OFWO’s business planning. The OFWO is effective in managing its stakeholder relationships except for not assessing regulatory capture risk as a discrete source of risk. The OFWO’s monitoring of its regulatory performance focused on operational decision-making rather than the achievement of its regulatory priorities and outcomes. The OFWO is redeveloping its performance measures with the intention of improving its reporting of efficiency and effectiveness.

9. The OFWO’s arrangements to encourage voluntary compliance and detect non-compliance with the Fair Work Act are largely effective. The OFWO has established arrangements for the prevention, and proactive and reactive detection, of non-compliance and has published a compliance and enforcement policy. The OFWO does not monitor timeliness, risk, or return on investment for its prevention and detection of non-compliance. The OFWO does not have insight into whether the balance of preventative and detective compliance and enforcement activities is appropriate.

10. The OFWO’s arrangements to enforce compliance with the Fair Work Act are largely effective. The OFWO has established arrangements to manage non-compliance cases and the OFWO deploys its enforcement tools in line with its regulatory posture and policies. The OFWO’s monitoring and reporting does not provide an assessment of the effectiveness of its enforcement activities and outcomes in promoting compliance with the Fair Work Act. The OFWO compliance and enforcement actions were undertaken in accordance with internal policies. These actions were not adequately documented in OFWO’s records management systems. The OFWO documented that it would deviate from implementing the mandatory requirements of the Australian Government Investigations Standard, October 2022 (AGIS 2022). Deviations include not implementing a quality assurance framework.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements

11. The OFWO’s approach to developing and implementing regulatory priorities and compliance strategies takes into consideration the requirements of the ministerial Statements of Expectations. The OFWO’s regulatory priorities and compliance strategies are not fully integrated into business planning and do not reflect a comprehensive assessment of risk exposures and mitigations. (See paragraphs 2.4 to 2.30)

12. The OFWO has established stakeholder engagement and management arrangements to support its regulatory functions. The OFWO has also established stakeholder feedback processes. The OFWO has not documented regulatory capture as a discrete source of risk or assessed the adequacy of its controls to mitigate regulatory capture risk. (See paragraphs 2.31 to 2.49)

13. The OFWO’s governance arrangements have a focus on operational decision-making. The enforcement board did not fully meet its terms of reference to provide strategic monitoring of regulatory activities. The OFWO’s performance reporting arrangements prior to 2024–25 included measures of output rather than efficiency and effectiveness. The OFWO is re-developing its performance measures and will need to provide greater insight into the ongoing effectiveness of its regulatory outcomes and impacts. (See paragraphs 2.50 to 2.84)

Prevention and detection of non-compliance

14. The OFWO has provided assistance, advice and education to employees, employers, outworkers, outworker entities and organisations to achieve regulatory objectives. The OFWO has developed and published a compliance and enforcement policy. The policy does not provide clear guidance to users about: how services will be prioritised and provided; and does not fully address the different needs of internal and external users. (See paragraphs 3.4 to 3.33)

15. The OFWO has established arrangements for proactive and reactive detection of non-compliance, including intelligence and analysis, proactive investigations, responding to requests for assistance, self-reporting of non-compliance and ad hoc investigations. These arrangements do not consider operational requirements and constraints, such as budgets, timeliness, risk and return on investment. This information would allow the OFWO to monitor the efficiency and effectiveness of its regulatory activities and assess whether the balance of preventative and detective activities is appropriate for the OFWO’s regulatory objectives. (See paragraphs 3.34 to 3.66)

Enforcement

16. The OFWO deploys its compliance and enforcement tools in line with its regulatory posture and compliance and enforcement policy. The use of compliance and enforcement tools requires long term management. Fifty per cent of investigations take more than 136 days to finalise with two per cent taking more than two years. The OFWO’s monitoring and reporting does not provide an assessment of the effectiveness of its enforcement activities and outcomes in promoting compliance with the Fair Work Act. (See paragraphs 4.2 to 4.17)

17. In July 2024, the OFWO assessed and agreed deviations from AGIS 2022. One ‘notable deviation’ from AGIS 2022 was the decision not to implement a quality assurance framework. Prior to July 2024, the OFWO did not use the relevant AGIS to inform the development of its policies, procedures, staff roles and staff qualifications. At November 2024, 50 per cent of OFWO staff conducting or oversighting investigations did not hold the relevant certification as required by AGIS 2022. The OFWO’s decision records did not evidence that compliance and enforcement activities were performed adequately. For example, case monitoring meeting and approvals were not consistently recorded in OFWO’s records management systems. (See paragraphs 4.18 to 4.55)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.29

The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman delivers a framework for the implementation and monitoring of regulatory priority areas and activities that is integrated with business planning and is risk-based.

Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.63

The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman ensures that governance bodies perform strategic oversight and monitoring of regulatory objectives and outcomes and consider the efficiency and effectiveness of regulatory activities.

Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 4.54

The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman ensures that there is:

- documentation of the completion of mandatory steps set out in policies and procedures for investigations; and

- appropriate review and quality assurance of investigations to improve levels of compliance and to take corrective action where necessary.

Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

18. The proposed audit report was provided to the OFWO. The OFWO’s summary response is reproduced below and its full response is at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the course of this audit are listed in Appendix 2.

The OFWO welcomes the ANAO’s report and agrees with the recommendations.

The OFWO has experienced considerable transformation over the past year. Central to the new strategic enforcement approach is tripartism, recognising that each element within the workplace relations system plays an important role in fostering a culture of compliance. As part of this, the OFWO has established a range of collaborative mechanisms with stakeholders and is updating critical strategic documents that define the Agency’s approach and operating environment.

A new organisational structure took effect on 1 July 2024 so that the OFWO is best positioned to deliver its identified objectives and strategic goals.

As detailed in our Statement of Intent, we use intelligence and data to inform our work, including the selection of our priority areas. We are committed to maintaining strong governance, supporting transparent and consistent decision-making.

As detailed in our Statement of Intent, we strive for continuous improvement in our policies, processes and practices. We are committed to focussing on developing the leadership and operational capability of staff at all levels, through our capability uplift program, to ensure we effectively discharge our statutory functions.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

19. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

Policy/program implementation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman (the OFWO) was established on 1 July 2009 as an independent statutory office created by the Fair Work Act 2009 (the Fair Work Act) to promote compliance with workplace relations legislation by employees and employers through advice, education and, where necessary, enforcement.4

1.2 The OFWO regulates all businesses and workers covered by the Fair Work Act. This represents approximately one million employing businesses and around 13 million workers. In 2023–24 the OFWO reported that it recovered $473 million in unpaid wages and entitlements for nearly 160,000 employees, of which $333 million was recovered from the large corporates sector.5

1.3 The Fair Work Ombudsman is the accountable authority of the OFWO. The Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations sets government policies and objectives relevant to the OFWO in carrying out its statutory functions as a regulator. The minister expects the OFWO ‘to be agile and to adapt to legislative change, working with stakeholders to implement these reforms and to support tripartism in Australian workplace relations’. The minister also expects the OFWO to apply the principles outlined in the Department of Finance Resource Management Guide No. 128: Regulator Performance (RMG 128)6 in its regulatory functions and in assessing performance and engagement with stakeholders.7

Regulatory functions

1.4 The Fair Work Ombudsman has the following functions as outlined in section 682 of the Fair Work Act:

- to promote: harmonious, productive and cooperative workplace relations; and compliance with the Fair Work Act and fair work instruments; including by providing education, assistance and advice to employees, employers, regulated workers, regulated businesses, persons in a road transport contractual chain, outworkers, outworker entities and organisations and producing best practice guides to workplace relations or workplace practices;

- to monitor compliance with the Fair Work Act and fair work instruments;

- to inquire into, and investigate, any act or practice that may be contrary to the Fair Work Act, a fair work instrument or a safety net contractual entitlement;

- to commence proceedings in a court, or to make applications to the Fair Work Commission8, to enforce the Fair Work Act, fair work instruments and safety net contractual entitlements;

- to publish a compliance and enforcement policy, including guidelines relating to the circumstances in which the Fair Work Ombudsman will, or will not, exercise relevant powers;

- to refer matters to relevant authorities; and

- to represent employees, regulated workers, or outworkers who are, or may become, a party to proceedings in a court, or a party to a matter before the Fair Work Commission, under the Fair Work Act or a fair work instrument, if the Fair Work Ombudsman considers that representing the employees, regulated workers, or outworkers will promote compliance with the Fair Work Act or the fair work instrument.

1.5 To discharge its regulatory functions, the OFWO uses a range of compliance and enforcement activities and tools that are either preventative or detective. Preventative regulatory activities include: providing education and advice to employees, employers, outworkers, outworker entities and organisations9; producing best practice guides and tools; and publishing a compliance and enforcement policy.

1.6 Detective regulatory activities include: gathering and reviewing intelligence and evidence; monitoring and analysis of workplace trends; exchanging information and intelligence with other regulators and government agencies; responding to requests for assistance; proactive investigations10; and monitoring and investigating voluntarily reported non-compliance (self-reported non-compliance).

1.7 When responding to requests for assistance, proactive investigations and monitoring and investigating instances of self-reported non-compliance, the OFWO can use a range of compliance and enforcement tools described in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Compliance and enforcement tools

|

Compliance and enforcement tool |

Description |

|

Enforceable undertaking |

An enforceable undertaking is a written agreement between an employer and the OFWO in relation to a Fair Work Act or fair work instrument contravention. An enforceable undertaking is often used where a contravention has occurred and the employer is prepared to voluntarily fix the issue and has agreed to prevention actions for the future. If an employer fails to comply with an enforceable undertaking, it may result in litigation/court proceedings. Enforceable undertakings are an enforcement tool outlined in section 715 of the Fair Work Act. |

|

Compliance notice |

A compliance notice may be issued by a Fair Work Inspector if they form a reasonable belief that the employer has contravened the Fair Work Act or fair work instrument. A compliance notice requires an employer to take specified action to remedy the direct effects of the identified contraventions and/or require the employer to produce reasonable evidence of compliance. The OFWO confirms compliance with compliance notices. If an employer fails to meet the requirements of a compliance notice, it may result in litigation/court proceedings. Compliance notices are an enforcement tool under section 716 of the Fair Work Act. |

|

Infringement notice |

An infringement notice requires an employer to pay a penalty if a Fair Work Inspector reasonably believes that the employer has committed one or more contraventions of the Fair Work Act, the regulations or fair work instrument. The level of the penalty will depend on the number and type of contraventions. Infringement notices are an enforcement tool outlined in regulation 4.04 of the Fair Work Regulations 2009. |

|

Contravention letter |

A contravention letter may be issued by a Fair Work Inspector under regulation 5.05 of the Fair Work Regulations 2009 if the inspector is satisfied that the employer has failed to observe a requirement of the Fair Work Act, regulations or fair work instrument. The contravention letter informs the employer of the failure, requires the employer to take the action specified in the letter, within the period specified in the letter to rectify the failure and require the employer to notify the Fair Work Inspector of any action taken to comply with the letter. |

|

Caution letter |

A caution letter is correspondence between the OFWO and an employer providing a caution regarding future compliance and warning that any future contraventions may lead to the issuing of an infringement notice or litigation/court proceedings. |

|

Litigation/court proceedings |

Litigation/court proceedings are reserved for more serious cases of non-compliance or when there is a failure to comply with another type of compliance and enforcement tool such as a compliance notice. |

Source: ANAO analysis of the OFWO compliance and enforcement policy and internal policies and procedures.

1.8 Since July 2022, there have been legislative amendments to the Fair Work Act, including changes to the protection and entitlements of employees and additional responsibilities and funding for the OFWO. This included the OFWO assuming responsibility for the regulation of the Fair Work Act for the commercial building and construction industry11 and the ability to investigate allegations related to the prohibition of workplace sexual harassment. In addition, legislative changes have introduced Commonwealth jurisdiction over criminal underpayments to allow the Commonwealth to bring criminal charges against businesses and individuals for the intentional underpayment of employees’ wages and certain entitlements. The impact of this change is that from January 2025 — in addition to the OFWO’s existing compliance and enforcement activities through civil proceedings — the OFWO has the responsibility to investigate potential criminal underpayment offences. As a result of these investigations the OFWO may, where appropriate, refer matters to the Australian Federal Police or the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions for consideration of criminal prosecution.

1.9 In 2023–24 the OFWO received approximately $167 million in departmental operating appropriations.12 As at 30 June 2024, the OFWO had 996 staff located in a network of 22 offices — one in each of the capital cities and 14 in regional areas. The Fair Work Ombudsman is structured into four groups, each lead by a Group Manager (SES Band 2 positions). The OFWO Executive team comprised Group Manager – Operations, Group Manager – Regulatory Transformation, Chief Operating Officer (Group Manager – Corporate and Engagement) and Chief Counsel (Group Manager – Legal and Policy). The Fair Work Ombudsman has established two executive advisory groups – referred to as governance bodies – to assist with oversight of the exercise of its regulatory functions. These are the enforcement board and corporate board.

External review of the OFWO

1.10 The Australian Government announced a review into the operations of the OFWO in the 2023–24 Budget. The objectives of the review were to:

- examine the operational practices and activities of the OFWO;

- assess how the OFWO allocates its resources to deliver its statutory mandate;

- identify any barriers to the OFWO operating efficiently to fulfil its functions; and

- provide recommendations to identify efficiencies and opportunities for savings and provide the basis for a 2.5 per cent ongoing saving from the OFWO’s departmental budget based on its October 2022 budget allocation.

1.11 The review was conducted by KPMG, contracted by the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations through a procurement process.13 The final report, the Review of the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman, was provided to the Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations in December 2023.

1.12 The review identified three primary opportunities for potential ‘immediate budget savings’ with associated recommendations; and four ‘other opportunities for consideration’ that were focused on improving overall operational efficiency and maximising regulatory impact. These were:

- review and rationalise office space in line with demand and flexible working arrangements (primary opportunity);

- address structural inefficiencies both horizontally across groups and vertically within organisational units (primary opportunity);

- achieve greater efficiency through shared services (primary opportunity);

- review regulatory strategy and outcomes of regulatory actions and adjust to ensure these are focused on the greatest harm, and are risk-based, strategic and targeted (other opportunity for consideration);

- strengthen the OFWO’s focus on collaboration to better leverage the influence and resources of other actors in the workplace relations ecosystem (other opportunity for consideration);

- support employees to engage with risk to allow for devolved decision-making, reduced layers of approval and more efficient processes (other opportunity for consideration); and

- continue capability uplift initiatives (other opportunity for consideration).

1.13 In March 2024, the Fair Work Ombudsman responded to the review in a letter to the Minister for Employment and Workplace Relations outlining the steps that the OFWO would take to consider and implement the recommendations. This included incorporating changes into the entity’s regulatory approach outlined in its 2024–25 corporate plan.

Previous ANAO audit

1.14 Auditor-General Report No. 14 2012–13 Delivery of Workplace Relations Services by the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman14 assessed the effectiveness of the OFWO’s administration of education and compliance services under the Fair Work Act. It found that the OFWO’s administration was generally sound, with scope to improve the use of information and analysis to further inform service delivery strategies. The ANAO made two recommendations relating to integrating risk management into planning and decision-making, and establishing performance measures, including measures of efficiency. For details on the implementation of these recommendations see paragraphs 2.28 and 2.84.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.15 The OFWO is the national workplace relations regulator. Its statutory functions include promoting and monitoring compliance with workplace laws, inquiring into and investigating breaches of the Fair Work Act and taking appropriate enforcement action. The OFWO regulates approximately one million employing businesses and around 13 million workers under the Fair Work Act. Since July 2022, the OFWO has made changes to its approach and operations in response to: the expansion of the coverage of the Fair Work Act; implementation of the recommendations resulting from an external review; and revisions to its budget. This audit was conducted to provide assurance to Parliament that the OFWO is exercising its regulatory functions effectively.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.16 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman’s exercise of its regulatory functions.

1.17 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has the OFWO established fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support the effective management of compliance with the Fair Work Act?

- Are the OFWO’s arrangements to encourage voluntary compliance and detect non-compliance with the Fair Work Act effective?

- Are the OFWO’s arrangements to enforce compliance with the Fair Work Act effective?

1.18 The audit examined the regulatory operations of the OFWO over the period from 1 July 2022 to 31 December 2024.

Audit methodology

1.19 To address the audit objective, the audit team:

- reviewed legislative and internal arrangements for activities to support regulatory functions;

- examined executive and governance committee meeting papers and minutes;

- reviewed strategy, procedures, guidance, risk registers and monitoring information relevant to regulatory decision-making;

- examined internal and external review outcomes and tracking of recommendation implementation; and

- held meetings with the Fair Work Ombudsman, OFWO Executives and officials.

1.20 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $351,714.

1.21 The team members for this audit were Peter Bell, Susan Ryan, Renina Boyd and Anne Rainger.

2. Governance arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman (the OFWO) has established fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support the effective management of compliance with the Fair Work Act 2009 (the Fair Work Act).

Conclusion

The OFWO has established largely fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support the effective management of compliance with the Fair Work Act. The OFWO developed compliance strategies that reflected ministerial Statements of Expectations. The compliance strategies were partly risk-based and not fully integrated into OFWO’s business planning. The OFWO is effective in managing its stakeholder relationships except for not assessing regulatory capture risk as a discrete source of risk. The OFWO’s monitoring of its regulatory performance focused on operational decision-making rather than the achievement of its regulatory priorities and outcomes. The OFWO is redeveloping its performance measures with the intention of improving its reporting of efficiency and effectiveness.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at: delivering a framework for the implementation and monitoring of regulatory priority areas and activities that is integrated with business planning and is risk-based; and ensuring governance bodies perform strategic oversight and consider the efficiency and effectiveness of regulatory activities.

The ANAO also identified one opportunity for improvement relating to performing a risk assessment for regulatory capture.

2.1 The Department of Finance has issued better practice guidance as part of Resource Management Guide No. 128: Regulator Performance (RMG 128) to assist Commonwealth entities that perform regulatory functions.15 This guidance outlines the content and use of the ministerial Statements of Expectations for regulators and corresponding regulator Statements of Intent.

2.2 Ministerial Statements of Expectations are issued by the responsible minister to a regulator to provide clarity about government policies and objectives relevant to the regulator in line with its statutory objectives, and the priorities the minister expects it to observe in conducting its operations. RMG 128 states that Statements of Expectations should be refreshed with every change in minister, change in regulator leadership, change in Australian Government policy or every two years.

2.3 In line with ministerial Statements of Expectations, the ANAO’s assessment of the OFWO’s governance arrangements for regulatory functions focuses on the development of a risk-based compliance strategy and regulatory priorities, effectiveness in managing stakeholder relationships and monitoring and reporting on regulatory performance.

Has the OFWO developed a risk-based compliance strategy?

The OFWO’s approach to developing and implementing regulatory priorities and compliance strategies takes into consideration the requirements of the ministerial Statements of Expectations. The OFWO’s regulatory priorities and compliance strategies are not fully integrated into business planning and do not reflect a comprehensive assessment of risk exposures and mitigations.

Statements of expectations

2.4 The OFWO has been issued with two Statements of Expectations — the first in October 2021 and the second in October 2023.16

2.5 The October 2021 Statement of Expectations reflected the principles of regulator best practice to be implemented by the OFWO as required by RMG 128. These principles were:

Continuous improvement and building trust: regulators adopt a whole-of-system perspective, continuously improving their performance, capability and culture, to build trust and confidence in Australia’s regulatory settings.

Risk-based and data-driven: regulators maintain essential safeguards, using data and digital technology to manage risks proportionately to minimise regulatory burden and to support those they regulate to comply and grow.

Collaboration and engagement: regulators are transparent and responsive, implementing regulations in a modern and collaborative way.

2.6 This Statement of Expectations emphasised the need to take a risk-based and data-driven approach to compliance and enforcement activities, centred on the establishment and maintenance of well-defined and clearly communicated compliance and enforcement priorities, and a clearly articulated approach to risk and how this informs decision-making. This statement also reflected the minister’s expectations for the OFWO’s contribution to the government’s deregulation agenda.

2.7 The 2023 Statement of Expectations built on the earlier statement and outlined expectations related to supporting tripartism17, working with stakeholders and adapting to legislative change that reflected the changed legislative landscape under the government’s workplace reform agenda and role of the OFWO. In particular, the Statement of Expectations referred to the need for the OFWO to make appropriate use of the full range of its enforcement powers and tools, while seeking to resolve workplace issues using voluntary means where appropriate to do so.

2.8 To develop its response (Statement of Intent), the OFWO established a formal process. This process included both internal and external consultation to allow staff and workplace relations stakeholders to engage with, and have an opportunity to provide input into, the direction of the OFWO. Statements of Intent were provided to the minister in December 2021 and December 2023 respectively.

2.9 RMG 128 states that Statements of Expectations should be incorporated into Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) processes such as corporate plans and annual reports. This requirement came into effect for the 2023–24 reporting year. The OFWO corporate plan for 2023–24 did not mention the Statement of Expectations or Statement of Intent. The corporate plan for 2024–25 mentions both. The OFWO annual report for 2023–24 mentions the Statement of Intent.

Compliance strategy and regulatory posture

2.10 A compliance strategy and regulatory posture are mechanisms used by regulators to articulate their regulatory approach. For the OFWO, its compliance strategy should cover regulatory priorities, how it will balance education and advice, compliance activities and enforcement actions to maximise regulatory effectiveness. Regulatory posture defines its approach and prioritisation of its regulatory functions. This includes the emphasis placed on the use of compliance and enforcement tools and how it will make decisions about resource allocation and risk. The OFWO uses its priority areas and priority work plans to articulate and document its overarching compliance strategy and regulatory posture. In addition, the OFWO’s compliance and enforcement policy communicates, internally and externally, how the OFWO fulfills its role as the workplace regulator.

2.11 Each year the OFWO develops and communicates its priority areas in its corporate plan.18 The development of priority areas is one mechanism used by the OFWO to enable the community to remain informed about the OFWO’s areas of focus. The priority areas are intended to give priority to industries that are at significant risk or demonstrate a history of non-compliance. The OFWO also prioritises, as enduring commitments, cohorts that are identified as requiring additional assistance. This includes vulnerable or at risk workers, including those who are young, live with disability or arrived in Australia on a temporary visa.

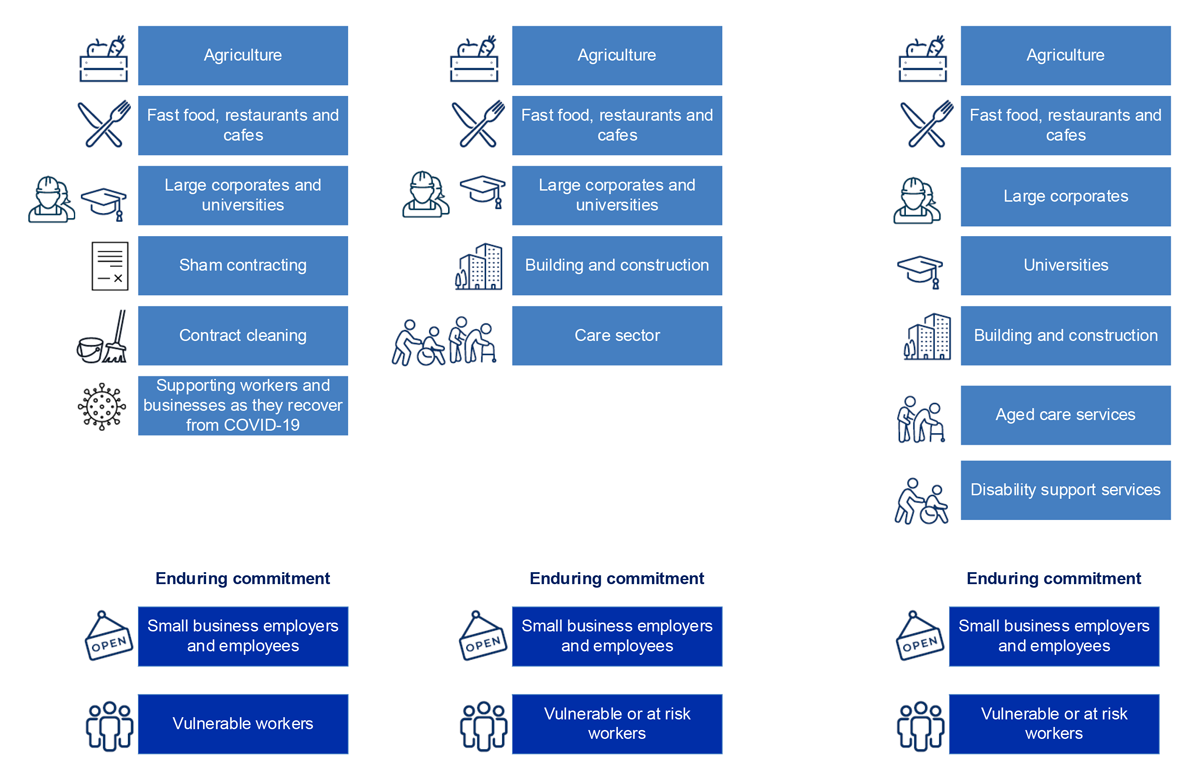

2.12 Figure 2.1 sets out how the OFWO’s priority areas have changed over the past three financial years.

Figure 2.1: Evolution of OFWO priority areas 2022–23 to 2024–25

Source: ANAO analysis of the OFWO’s corporate plans for 2022–23, 2023–24 and 2024–25.

2.13 The development of OFWO’s priority areas is undertaken using a process which includes an analysis of quantitative and qualitative data derived from feedback from staff and stakeholders and an analysis of existing priorities, emerging issues, trends and regulatory risks across the labour market.

2.14 In 2022–23 and 2023–24 the OFWO established annual work plans covering each priority area. These work plans identified activities to be undertaken such as: education and communication; development of tailored material and resources; and proactive compliance and enforcement activities. These work plans were provided to the OFWO governance bodies on a quarterly basis.19 An annual priority work plan for 2024–25 has not been developed by the OFWO. In December 2024, the OFWO advised the ANAO that it is taking a new approach to addressing its priority areas by working with external stakeholder reference groups to identify and understand the issues within each priority area.

2.15 An overarching compliance strategy and regulatory posture were not consistently incorporated into the OFWO’s business planning documentation. Business plans and work plans did not contain information on the number of activities, budget or resources allocated to each priority area based on risk. The work plans did not articulate how the planned mix of regulatory activities would achieve the OFWO’s regulatory posture and target the areas of greatest harm.

2.16 Some priority areas had detailed strategies and performance measures established, whereas others had no strategies or performance measures reported. Two examples are discussed below.

- The agriculture sector had detailed communication and enforcement strategies which were provided to governance bodies on a quarterly basis.

- The care sector became a priority area on 1 July 2023, a care sector communication strategy was not prepared until October 2024. As at December 2024, this document had not been provided to the OFWO governance bodies.

2.17 The OFWO has not identified or documented what business planning information should be prepared to support the implementation and monitoring of its priority areas and/or work plans. Without adequate documentation and monitoring of each priority area, there is a risk that the OFWO is not targeting or achieving effective regulation of its priority areas.

2.18 Annual branch business plans are prepared by all branches within the OFWO to set out each branch’s intended deliverables for the year and to provide links to corporate plan objectives and strategies. Branch business plans for 2022–23 and 2023–24 included information on activities, outcomes, risks and measuring success (often linked to corporate plan performance measures and targets). Branch business plans for 2024–25 included information on key deliverables and risks linked to strategic objectives.20 Branch business plans for 2024–25 did not include information on activities in the priority areas.

2.19 Branch business plans are supported by organisation-level budget processes where average staffing levels for each branch are allocated, monitored and reviewed mid-year and annually. The OFWO’s priority work plans were not supported by budget or resource planning information. For example, annual priority plans do not provide a connection to budget or performance measures for proactive and responsive compliance and enforcement activities.

Identification and management of risks and exposures

2.20 The ministerial Statements of Expectations issued in October 2021 and October 2023 set out the requirement for the OFWO’s compliance and enforcement activities to be risk-based and data-driven. In its responding Statements of Intent, the OFWO outlined a number of mechanisms to fulfil this requirement including:

- through a risk management framework and processes, including risk appetite statements;

- risk-based and data-driven analysis to support the development of the regulatory priorities and corporate plans;

- use of intelligence and analysis to drive compliance and enforcement activities (such as anonymous reports, research, education and proactive investigations); and

- regularly seeking feedback from a range of stakeholders.

Risk management framework and processes

2.21 The OFWO risk management policy and guidelines were updated in July 2023. These documents are consistent with the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy 2023.

2.22 The OFWO risk management policy and guidelines provide information on risk management responsibilities and activities for corporate functions. They do not include information on regulatory functions.

2.23 The OFWO risk management guidelines identify that risk assessments should be undertaken as part of annual business planning processes. Business plans for 2022–23, 2023–24 and 2024–25 included risk information. They did not assess risks in accordance with the OFWO risk management policy. For example, they did not identify current controls, proposed mitigations and/or rate residual risks.

2.24 The OFWO risk management policy states that a review of the strategic risk register will be undertaken ‘at least every six months’. The OFWO’s strategic risks were last assessed by the OFWO in December 2022. Strategic risks were updated as part of the preparation of the 2024–25 corporate plan, with two additional risks added. An assessment of the strategic risks in accordance with OFWO’s risk management guidelines (for example the rating of residual risk and assessment of whether the risk was within risk appetite) has not occurred as at December 2024.

2.25 The OFWO risk management policy outlines the entity’s risk appetite and tolerance statement. The risk tolerances were identified for three of five strategic risks that were identified in corporate plans for 2022–23 and 2023–24.21 The target risk levels in the strategic risk assessment were set above stated risk appetites and tolerances included in the OFWO’s risk management policy without challenge or explanation of why these risks were acceptable to the OFWO. As at December 2024 the risk appetite and tolerance statements in the OFWO risk management policy were not updated to reflect the strategic risks outlined in the 2024–25 corporate plan published in August 2024.

2.26 The OFWO has not tested controls related to strategic and operational risks in accordance with the requirements of the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy 2023 and its own risk management policy.

2.27 The KPMG review of the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman, December 202322, identified that there were opportunities for consideration related to a review of the OFWO’s regulatory strategy and outcomes based on risk. In response to the KPMG report, the OFWO agreed to perform a comprehensive review of its compliance and enforcement policy (refer to paragraphs 3.29 to 3.33). Regulatory posture and performance measures were also updated as part of the 2024–25 corporate plan development process (refer to paragraphs 2.72 to 2.84 for further discussion on performance reporting). The actions taken by the OFWO to address the external review’s ‘opportunities for consideration’ did not resolve underlying issues with business planning and risk management.

2.28 Auditor-General Report No. 14 2012–13 Delivery of Workplace Relations Services by the Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman assessed the effectiveness of the OFWO’s administration of education and compliance services under the Fair Work Act. At that time, the audit found that the quality of business plans prepared by the OFWO was variable, particularly in terms of alignment with the strategic plan and projects, performance information and risk assessments. In that report, the ANAO recommended that the OFWO ‘better integrate risk management into strategic and operational planning and decision making’. These findings from 2012–13 have not resulted in a lasting improvement and continue to be relevant for the OFWO and its approach to business planning, performance monitoring and risk management.

Recommendation no.1

2.29 The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman delivers a framework for the implementation and monitoring of regulatory priority areas and activities that is integrated with business planning and is risk-based.

Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman response: Agreed.

2.30 The OFWO acknowledges the identified issues regarding a lack of consistency as to how regulatory priority areas are considered in the business planning process. The OFWO will undertake a review of these processes to identify improvements across all relevant areas, including the development of a risk-based framework to inform the implementation and oversight of regulatory priority areas. This review will also encompass the methods by which operational areas design, monitor, and report on outcomes in accordance with the framework.

Does the OFWO effectively manage its relationships, including appropriately addressing regulatory capture risk?

The OFWO has established stakeholder engagement and management arrangements to support its regulatory functions. The OFWO has also established stakeholder feedback processes. The OFWO has not documented regulatory capture as a discrete source of risk or assessed the adequacy of its controls to mitigate regulatory capture risk.

2.31 The Statement of Expectations October 2023 states that to perform its regulatory functions, the OFWO must be open, transparent and have consistent engagement with a wide range of stakeholders, including industry, government and the broader community to build tripartism, and to maintain competent and innovative regulatory practices.

2.32 The 2018 stakeholder engagement strategy was in effect until a new stakeholder engagement strategy was developed and approved in December 2022. The new strategy took into consideration the collaboration and engagement expectations outlined in the 2021 Statement of Intent. The strategy included information on how the OFWO would ‘involve and collaborate’ with stakeholders for advice, to seek expertise, to share perspectives or experience, to generate innovative ideas, or to help address complex issues. This included the use of reference groups, taskforces, cross-government working groups and bi-lateral and multi-lateral government forums. An updated stakeholder engagement strategy (including changed dates and titles) was published on the OFWO website in May 2024.23

2.33 In addition to the stakeholder engagement strategy, a community engagement strategy and work plan were developed by the OFWO in September 2023. The aim of the community engagement strategy outlined in the document was to:

educate communities and stakeholders about the role of the OFWO, workplace rights and obligations, the tools and resources available to support workplace participants, and the pathways available for accessing advice services to achieve harmonious, productive, cooperative and compliant workplace relations.

2.34 Community engagement work plans were prepared to support the strategy. The work plans outlined key activities and success measures to be implemented during the year. The success measures included a mixture of targets, tasks and mechanisms (such as feedback and regular forums) to be used by the OFWO to understand the use and impact of engagement activities. These measures did not include baselines to assess achievements, and results were compared to prior years.

2.35 The OFWO governance bodies were provided with quarterly updates on activities related to stakeholder and community engagement. Updates focused on activities, performance and engagement types compared to the prior period.

Forums and advisory groups

2.36 To facilitate the establishment and maintenance of arrangements for collaboration and engagement, in its December 2023 Statement of Intent the OFWO committed to the following stakeholder engagement arrangements:

There was consensus on the benefits of establishing a standing tripartite advisory group of peak employer organisations and worker representatives to provide … advice and information relevant to our work assisting the regulated community, with equal representation from worker and business organisations. The organisations that I intend to invite to become standing members of this group are key workplace relations institutions and represent the broad interests of both workers and businesses. They are the:

- Australian Council of Trade Unions

- Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- Australian Industry Group

- Business Council of Australia

- Council of Small Business Organisations of Australia.24

2.37 As at December 2024, the OFWO had established a range of tripartite forums which comprise external stakeholder representatives and are chaired by the Fair Work Ombudsman or OFWO Executive. Terms of reference, agendas and meeting outcomes are maintained for these forums. The forums, which are aligned to the priority areas, are:

- advisory group (peak group which includes sub-committees for large corporates and small business);

- aged care services reference group;

- agriculture reference group;

- building and construction reference group;

- disability support services reference group;

- fast food, restaurants and cafés reference group; and

- higher education reference group.

2.38 In addition, the OFWO participates in a number of intergovernmental committees to share information and approaches to regulation and monitoring non-compliance with the Fair Work Act. These include the: Federal Regulatory Agency Group; Phoenix Taskforce; Interdepartmental Committee on Human Trafficking and Slavery; Migrant Workers Interagency Group; Pacific Labour and Pacific Migration Interdepartmental Committee; and Respect@Work Council.

Stakeholder feedback

2.39 The OFWO has established stakeholder feedback mechanisms and considers stakeholder feedback when preparing its strategic direction, priority areas and in corporate plan performance measure reporting.

2.40 In 2023 the OFWO engaged with external stakeholders when preparing its response to the ministerial Statement of Expectations. It also engaged with external stakeholder groups when developing its priorities, corporate plans and performance measures in 2023 and 2024. Feedback from external stakeholders has been collated and maintained by the OFWO to assist in informing its strategic planning activities.

2.41 In its 2022–23 and 2023–24 corporate plans the OFWO identified a range of performance measures which included the collection and analysis of stakeholder feedback to assess satisfaction with advice from, and interactions with, the OFWO. These performance measures included obtaining direct feedback and information on satisfaction levels from customers25 interacting with the OFWO through the Fair Work Infoline26 and use of digital education tools. In 2022–23 and 2023–24 the OFWO reported in its annual reports that these performance measures were met with satisfaction levels of customers meeting the target of greater than 75 per cent.27

2.42 In its 2024–25 corporate plan, the OFWO states that it is re-developing its performance measures, including those related to customer perceptions and feedback. The revisions to the performance measures include the development of a performance measure to conduct a survey to assess the Australian public’s knowledge of the Fair Work Ombudsman and the role of the OFWO. As at December 2024 these new performance measures remained under development.

Regulatory capture risk

2.43 Maintaining independence is crucial for regulators to effectively perform their functions. The 2019 Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (the Hayne Royal Commission) stated that ‘the risk of regulatory capture is well acknowledged’.28 The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, in its 2019 report on Statutory Oversight of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, the Takeovers Panel and the Corporations Legislation, stated that:

The committee considers that regulatory capture is a significant issue faced by Australian regulators generally, given the size and power of corporations that operate in Australia.29

2.44 The committee defined regulatory capture as:

instances where regulators are excessively influenced or effectively controlled by the industry they are supposed to be regulating. There are three areas in which particular risks arise for regulatory capture:

- staff moving between industry and regulatory jobs;

- secondments; and

- where regulatory staff are embedded in private sector organisations (that is, required to conduct their work within the workplace of industry participants, away from their home base at the regulator).30

2.45 The NSW Government Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal has stated that:

Regulatory capture risks refer to the scenario where a regulatory agency, mandated to oversee and enforce rules to maintain public interest, ends up being unduly influenced by parties with vested interests, such as entities it is meant to regulate or special interest groups. This situation can result in the regulator making decisions that prioritise the interest of those parties over the broader public interest.31

2.46 The OFWO has not assessed regulatory capture risk or controls as part of its risk management or business planning processes. The OFWO has considered reputational risks, stakeholder engagement risks, and fraud and integrity risks as part of developing its internal processes and procedures. Branch business plans did not assess risks in accordance with the OFWO risk management policy and guidelines, and did not identify controls, mitigations and/or residual risk ratings for risks.

2.47 The OFWO fraud risk assessment, December 2023, identified risks related to the fraudulent manipulation or misuse of authority of position in compliance and enforcement activities including:

- employees using their position to exert influence over parties subject to regulation (or perform additional investigation processes) for personal gain, or for the benefit of family or friends;

- employees provide favourable interpretations of awards, legislative or regulatory instruments or overlook contraventions or fraudulent/criminal activity for personal gain;

- staff do not appropriately escalate complaints received from the public about personnel due to a conflict of interest or personal relationship with the personnel member; and

- an employee fails to declare changes in their personal circumstances that have a material impact on their suitability to carry out their role, such as criminal conviction or bankruptcy proceedings.

2.48 The fraud risk assessment identified a range of controls to mitigate these risks including: annual declarations by fair work inspectors of continuing good character; the need for all staff to disclose potential, real or apparent conflicts of interest; annual declarations of interest for fair work inspectors; and that non-SES staff must seek approval of a delegate prior to accepting gifts, benefits or hospitality.

Opportunity for improvement

2.49 The OFWO could perform a risk assessment for regulatory capture, including identification and assessment of controls and residual risk.

Does the OFWO effectively monitor and report on its performance?

The OFWO’s governance arrangements have a focus on operational decision-making. The enforcement board did not fully meet its terms of reference to provide strategic monitoring of regulatory activities. The OFWO’s performance reporting arrangements prior to 2024–25 included measures of output rather than efficiency and effectiveness. The OFWO is re-developing its performance measures and will need to provide greater insight into the ongoing effectiveness of its regulatory outcomes and impacts.

Governance arrangements

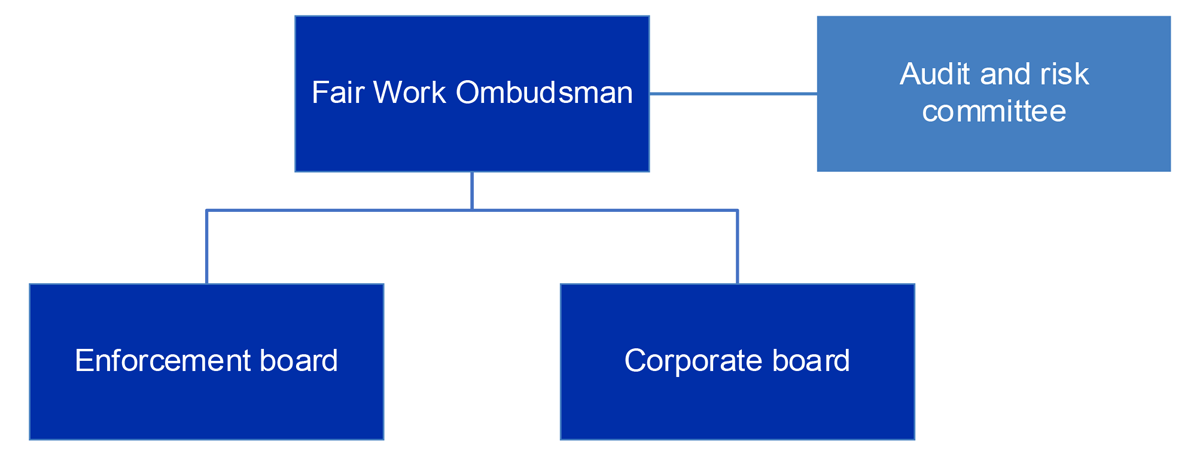

2.50 The Fair Work Ombudsman has established two executive advisory groups to assist in discharging their role as the accountable authority of the OFWO under the PGPA Act — the enforcement board and the corporate board. In addition, the OFWO audit and risk committee provides ‘independent assurance and advice’ on the OFWO’s financial and performance reporting, risk oversight and management, internal controls system and policy compliance. Figure 2.2 illustrates the governance structure.

Figure 2.2: Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman’s governance structure

Source: ANAO analysis of the OFWO’s governance structure.

Enforcement board

2.51 The enforcement board was established to advise and assist the Fair Work Ombudsman in relation to the OFWO’s whole of agency compliance and enforcement activities and the strategic application of resources to achieve the OFWO’s functions under the Fair Work Act and other legislation. The enforcement board terms of reference dated July 2022 outlined the three members of the board as: the Fair Work Ombudsman (chair); Deputy Fair Work Ombudsman Compliance and Enforcement; and Deputy Fair Work Ombudsman Policy and Communications. The terms of reference stated that the Chief Operating Officer and the Chief Counsel were standing attendees — not voting members of the board. The position of Deputy Fair Work Ombudsman Large Corporates and Industrial Compliance, created in February 2023, was not added to the terms of reference as a member of the board. This position ceased in July 2024 when there were structural changes to the OFWO Executive team.

2.52 Since September 2023, the enforcement board has been chaired by the Deputy Fair Work Ombudsman Compliance and Enforcement rather than the Fair Work Ombudsman. The terms of reference were updated to reflect this change in July 2024. The composition of the enforcement board between July 2022 and June 2024 did not include the Chief Operating Officer who had responsibility for people, technology and corporate services.

2.53 The July 2024 enforcement board terms of reference updated the membership of the board to reflect changes in OFWO’s organisational structure. The three members of the enforcement board from July 2024 were: Group Manager – Operations (Chair); Fair Work Ombudsman and Group Manager – Regulatory Transformation. The Group Manager – Corporate and Engagement and Group Manager – Legal and Policy may attend the board. They are not voting members of the board. The enforcement board meets fortnightly.

2.54 In the terms of reference, the purpose of the enforcement board was to provide advice and assistance to the accountable authority. This was achieved with meeting minutes recording board ‘endorsement’ of decisions and accountable authority ‘approval’ of the decision in the same meeting.

2.55 The functions of the enforcement board remained consistent between July 2022 and December 2024. The specific functions of the board, as set out in its terms of reference, have been summarised in Table 2.1, including a high-level analysis of whether the function was discharged.

Table 2.1: Functions of the enforcement board and analysis of its responsibilities

|

Function of the board |

ANAO analysis |

Assessment |

|

Setting the key priority areas for the OFWO. |

Priority areas were analysed and set for 2022–23, 2023–24 and 2024–25. |

◆ |

|

Making key strategic and operational decisions with respect to the OFWO’s compliance and enforcement activities in line with the priorities, as well as the OFWO’s purpose and functions as set out in the Fair Work Act. |

There was no analysis and decision-making related to strategic planning and monitoring of regulatory activities and outcomes. For example, the balance of activities, time and effort for implementation of regulatory functions and activities or achievement of regulatory performance outcomes and impacts were not considered by the board. Key operational decisions were considered by the board and recommended to the accountable authority for approval. This included information related to: ‘significant matters progressing to potential high-end enforcement outcomes’; key investigations; key litigations; self-report decisions and enforcement outcomes; approval of proactive investigations plans and finalisation of key investigations. Neither the enforcement board nor corporate board assessed the efficient and effective deployment of resources, investments and budgets for the OFWO’s regulatory functions and activities. |

▲ |

|

Guiding the OFWO to promote a culture of compliance by equipping workers and businesses in Australia with the information and support they need to make good choices in their workplaces and comply with workplace laws. |

Although education, advice and assistance were included as categories in the priority annual work plans monitored by the enforcement board; underlying strategies were not assessed or monitored by the board for all priority areas. The OFWO monitored corporate plan performance measures. It did not monitor regulatory impacts and outcomes. |

▲ |

|

Leveraging communication activities to send a strong message to the community about workplace relations laws and the consequences of non-compliance. |

Quarterly communications reporting was considered by the board. |

◆ |

|

Approving the annual Priority Areas Plan, including the key deliverables designed to address identified priorities and how information, education and communication activities will support the OFWO’s compliance activities. |

Annual work plans were approved for 2022–23 and 2023–24. Deficiencies in these work plans are identified at paragraphs 2.14 and 2.15. No annual work plan was approved or monitored for 2024–25. |

▲ |

|

Monitoring implementation of deliverables in the Priority Areas Plan, and efforts to support these through complementary promotional, education and communication activities. |

Work plans were provided on a quarterly basis until June 2024. Work plans included ‘tracked changes’ to record progress. Several activities spanned multiple years and were not appropriately tracked. Operational constraints such as budget and resource allocation were not considered by the board. |

▲ |

|

Approving the OFWO’s Compliance and Enforcement Policy |

The compliance and enforcement policy was not updated between July 2020 and December 2024. In January 2025 a new compliance and enforcement policy was published on the OFWO website. The enforcement board did not approve the new compliance and enforcement policy before it was published. |

■ |

|

Making decisions relating to the exercise of the OFWO’s powers and functions under the Fair Work Act and other relevant legislation, including with respect to:

|

Information on enforceable undertakings was examined by the board, including recommendations to commence negotiations for enforceable undertakings. Key operational decisions were reviewed by the enforcement board. |

◆ |

Key: ◆ Fully discharged ▲ Partially discharged ■ Not discharged

Source: ANAO analysis of enforcement board papers and minutes between July 2022 and December 2024.

2.56 Table 2.1 shows that the enforcement board did not discharge its strategic oversight functions as outlined in its terms of reference. The board received operational reporting on investigations underway. These reports did not include analysis of important trends or impacts on the OFWO’s strategies and objectives. Regulatory activities frequently spanned multiple years. The enforcement board did not adequately monitor these multi-year regulatory activities and outcomes. Since July 2024, with the implementation of the new organisational structure and changes in membership of the Executive team, the enforcement board has commenced consideration of changes to its forward agenda to better align to its terms of reference.

2.57 The enforcement board had a role in the OFWO’s regulatory operational decisions.32 For example, all decisions relating to negotiating an enforceable undertaking were taken to the board. The enforcement board did not leverage its operational role into strategic decision-making and oversight as required by its terms of reference.

Corporate board

2.58 The corporate board was established to support and assist the Fair Work Ombudsman by engaging in informed discussion in relation to the corporate and financial performance of the OFWO, compliance with relevant legislation, and the monitoring and review of compliance requirements and performance indicators. It meets monthly.

2.59 The corporate board terms of reference July 2022 prescribed that there would be five members of the board: the Fair Work Ombudsman (chair); Chief Operating Officer; Chief Counsel; Deputy Fair Work Ombudsman Compliance and Enforcement; and Deputy Fair Work Ombudsman Policy and Communications. Updated terms of reference were introduced in July 2023 to include the Deputy Fair Work Ombudsman Large Corporates and Industrial Compliance as a member of the corporate board.

2.60 In practice, since September 2023, the corporate board was chaired by the Chief Operating Officer rather than the Fair Work Ombudsman. The terms of reference have not been updated as at December 2024 to reflect this change in the board’s operation.

2.61 The functions of the corporate board remained consistent between July 2022 and December 2024. The specific terms of reference of the board which relate to the exercise of its regulatory functions have been summarised in Table 2.2, including a high-level analysis of whether the function was discharged.

Table 2.2: Functions of the corporate board relevant to its regulatory role and analysis of its responsibilities

|

Function of the boarda |

ANAO analysis |

Assessment |

|

Making key strategic and operational decisions with respect to corporate and financial performance |

Budgets and mid-year budget reviews were assessed by the board, this included the allocation of average staffing levels to relevant branches. |

◆ |

|

Initiation of entity wide reviews |

The tracking of the implementation of actions to address key reviews was considered by the board. This included tracking recommendations from:

|

◆ |

|

Systems of internal controls for the oversight and management of strategic risks Strategic risks and risk appetite of the OFWO |

Monitoring of strategic risk registers. This was last reviewed by the board in December 2022. The OFWO’s risk management policy including the risk appetite statement was endorsed by the board in July 2023. The OFWO corporate plan 2024–25 was discussed at the board, this included revisions to the strategic risks. A strategic risk assessment, as required by the OFWO risk management policy and guidelines, was not performed. The assessment should have included the identification of controls, mitigations and residual risk ratings. |

▲ |

|

The efficient and effective deployment of resources, investments and budgets in accordance with agreed [regulatory] priorities |

Although budget and mid-year budget review information is considered, this was at the branch level focused on allocation of average staffing levels within branches. There is no resourcing allocated to priority areas or activities. Neither the corporate board nor enforcement board assessed the efficient and effective deployment of resources, investments and budgets for the OFWO’s regulatory functions and activities. |

▲ |

|

Endorsing and monitoring business plans and the OFWO’s corporate plan |

Information related to corporate plan development and branch business planning processes were discussed by the board. There were mid-year budget reviews of branch business plans. |

◆ |

|

Whole of entity corporate strategies and frameworks, including the Information and communications technology strategy and performance, capability and staff development frameworks |

Discussed the compliance and enforcement capability framework review progress. Endorsed the gap analysis of the Australian Government Investigations Standard (AGIS), including acceptance of deviations from mandatory requirements. Provided with updates on the approach to determining and implementing the criminal underpayment responsibilities. |

◆ |

Key: ◆ Fully discharged ▲ Partially discharged ■ Not discharged

Note a: General functions outlined in the corporate board terms of reference identified in this table have been assessed against their relevance to the exercise of the OFWO’s regulatory role.

Source: ANAO analysis of corporate board papers and minutes between July 2022 and December 2024.

2.62 The corporate board did not fully discharge its terms of reference relevant to the exercise of its regulatory functions. This was largely because there was no connection between regulatory priorities, budget and resource information and risk.

Recommendation no.2

2.63 The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman ensures that governance bodies perform strategic oversight and monitoring of regulatory objectives and outcomes and consider the efficiency and effectiveness of regulatory activities.

Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman response: Agreed.

2.64 The OFWO acknowledges the observations and findings regarding the functions of its governance bodies and recognises the identified areas for improvement in strategic and operational risk management. The OFWO commenced a comprehensive governance review in late 2024 that includes evaluating the current governance bodies and assessing whether the governance framework operates effectively and supports the Accountable Authority in ensuring that the OFWO meets its objectives, including maintaining appropriate systems for risk oversight and consideration of efficiency and effectiveness of regulatory activities. The outcomes of this governance review involve changes to the current governance bodies, including a review of the terms of reference for each Board and Sub-Committee, to embed a strong governance framework that supports strategic oversight and monitoring of the legislative functions and strategic objectives of the OFWO.

Governance reviews

2.65 The terms of reference for the enforcement board and corporate board include that a review of the boards will form part of the annual governance framework review conducted by the OFWO.

2.66 A 2022 governance evaluation review report was prepared in December 2022. This document reviewed the activities of the enforcement board and corporate board. The review was based on a survey of 80 staff including committee members and regular attendees.33 A total of 58 people responded to the survey. The survey centred around whether members and attendees believed the mandate was discharged appropriately and to identify opportunities to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of decision-making.

2.67 Eight recommendations were identified by the review and monitored by the OFWO. These recommendations related to administrative support for the boards; clarifying the type and volume of information to be provided to boards; processes to manage conflicts of interest; and decision-making responsibilities of sub-committees.

2.68 A subsequent governance review was deferred in 2023 to allow for the new Fair Work Ombudsman — who commenced in September 2023 — to have input into the review. There was a further deferral of a governance review to accommodate the organisational restructure which became effective in July 2024. In December 2024, the outcomes of the 2024 governance evaluation review were tabled at the corporate board for discussion. The review identified 46 general findings and 11 considerations for change.

Audit and risk committee

2.69 The audit and risk committee charter was updated in March 2024. The committee has been established in accordance with section 45 of the PGPA Act and section 17 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule). The charter sets out the role and responsibilities of the committee, including its objective, authority, membership, functions, reporting and administrative arrangements. During 2022–23 and 2023–24, the committee comprised four independent members and met five times during the year.

2.70 In June 2023 the committee discussed and supported the preparation of a 2023–26 internal audit plan.34 Internal audit reports and outcomes were discussed at the audit and risk committee. The committee monitored the implementation of management actions to address identified risk, control and compliance weaknesses.

2.71 The committee examined processes to prepare information to support the annual financial statements and annual performance statements and provided advice to the accountable authority.

Performance reporting

Performance reporting as a non-corporate Commonwealth entity

2.72 In line with the PGPA Act and PGPA Rule requirements the OFWO performance measures and targets are included in its corporate plans and annual reports. The OFWO’s performance measures and targets included in its corporate plans and annual reports remained consistent for 2022–23 and 2023–24.35 For the 2024–25 corporate plan, performance measures and targets were redeveloped. As at December 2024, two performance measures and targets for 2024–25 were under development. The intention of the redevelopment is to improve measurement of the efficiency and effectiveness of the OFWO’s regulatory activities and outcomes.

2.73 The OFWO’s performance measures and targets outlined in its corporate plans for 2022–23 and 2023–24 are summarised in Appendix 3. There were a total of nine performance measures:

- three of the performance measures were output measures related to the quality of the services provided by the OFWO through its Fair Work Infoline, digital tools and engagement with key stakeholders (KPI 1, KPI 2 and KPI 3);

- one of the performance measures was an output measure related to the time taken to produce an output for responding to requests for assistance involving a workplace dispute (KPI 4);

- four of the performance measures were output measures related to the number of compliance and enforcement tools used by the OFWO during the reporting period. For example, the number of compliance notices issued (KPI 5, KPI 6, KPI 7 and KPI 8); and

- one of the performance measures related to the task of developing and publishing priority areas (KPI 9).

2.74 The OFWO’s performance measures and targets outlined in its corporate plan for 2024–25 are also summarised in Appendix 3. There were a total of eight performance measures, with two still under development.36

2.75 An assessment of the OFWO’s compliance with PGPA Rule requirements for the design and establishment of its performance measures related to its regulatory functions is detailed in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: ANAO analysis of OFWO’s compliance with PGPA Rule requirements for its regulatory function performance measures

|

PGPA Rule requirement |

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

2024–25 |

ANAO analysis |

|

Use sources of information and methodologies that are reliable and verifiable Subsection 16EA(a) |

◆ |

◆ |

Under development |

For each financial year, the OFWO prepared information on every performance measure and target to outline the sources of information and methodologies to be used to measure performance. The OFWO has documented its awareness of deficiencies related to the reliability of information, particularly where surveys with low response rates are used to assess performance. |

|

Provide an unbiased basis for the measurement and assessment of the entity’s performance Subsection 16EA(c) |

◆ |

◆ |

Under development |

For each financial year, the OFWO prepared information on every performance measure and target to outline the sources of information and methodologies to be used to measure performance. The OFWO has documented its awareness of the potential bias in the performance measure and how this would be managed by the OFWO. |

|

Comprise a mix of qualitative and quantitative performance measures Subsection 16EA(d) |

◆ |

◆ |

Under development |

The OFWO has provided a mix of qualitative and quantitative measures through performance measures which focus on the number of compliance and enforcement actions, the timeliness of operations and the level of satisfaction of customers with the quality of service. |

|

Include measures of the entity’s outputs, efficiency and effectiveness Subsection 16EA(e) |

■ |

■ |

Under development |