Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Effectiveness of Board Governance at Old Parliament House

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the governance board in Old Parliament House.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The governing board of a corporate Commonwealth entity is the accountable authority for the entity under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act)1, with responsibility for ‘leading, governing and setting the strategic direction’ for the entity.2

2. Around 60 corporate Commonwealth entities subject to the PGPA Act have governing boards, comprising a total of approximately 510 board positions.3 Corporate Commonwealth entities with governance boards vary significantly by function, and governance boards may also vary in their composition, operating arrangements, independence and subject-matter focus, depending on the specific requirements of their enabling legislation and other applicable laws.

Boards and corporate governance

Duties and roles

3. Sections 15 to 19 of the PGPA Act impose duties on accountable authorities in relation to governing the corporate Commonwealth entity for which they are responsible.4 As the accountable authority, members of Commonwealth governing boards are also officials under the PGPA Act and subject to the general duties of officials in sections 25 to 29 of the Act.5 Guidance issued to accountable authorities by the Department of Finance (Finance) observes that ‘each of these duties is as important as the others’.6

4. Boards play a key role in the effective governance of an entity. Corporate governance is generally considered to involve two dimensions, which are the responsibility of the governing board. These are:

Performance—monitoring the performance of the organisation and CEO…

Conformance—compliance with legal requirements and corporate governance and industry standards, and accountability to relevant stakeholders.

… it is important to understand that governing is not the same as managing. Broadly, governance involves the systems and processes in place that shape, enable and oversee management of an organisation. Management is concerned with doing – with co-ordinating and managing the day-to-day operations of the business. 7

Old Parliament House

5. Old Parliament House (OPH) has a governing board and operates under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (Establishing Old Parliament House) Rule 2016 (OPH Rule) as a not-for-profit corporate Commonwealth entity. OPH key functions include to conserve, develop and present the OPH building and collections; and to provide public programs and research activities related to Australia’s social and parliamentary history.8

Rationale for undertaking the audit

6. This topic was selected for audit as part of the ANAO’s multi-year audit program that examines aspects of the implementation of the PGPA Act. This audit provides an opportunity for the ANAO to review whether boards have established effective arrangements to comply with selected legislative and policy requirements and adopted practices that support effective governance. The audit also contributes to the identification of practices that support effective governance that could be applied in other entities. This audit is one of a series of governance audits that apply a standard methodology to the governance of individual boards.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

7. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the governance board in Old Parliament House.

8. To form a view against the audit objective the following high level criteria were adopted:

- the board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative requirements and the board has structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance; and

- the board has established fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance with key legislative and other requirements.

9. The audit examined the period July 2016 until March 2019.

10. Guidance to boards issued by Finance was reviewed by the ANAO having regard to the report of the 2019 Hayne Royal Commission9, which was released in the course of this audit, and other key reviews of board governance.10

Conclusion

11. The governance and oversight arrangements adopted by the Old Parliament House board are effective.

Supporting findings

Guidance

12. The 2018 APRA Prudential Inquiry and 2019 Hayne Royal Commission have again highlighted the criticality of effective governance, and there would be merit in the Department of Finance issuing guidance which has regard to the key insights and messages of those inquiries directed to accountable authorities including governance boards.

OPH board governance arrangements

13. The board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative requirements and the board has structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance.

14. The ANAO has identified a number of opportunities for improvement relating to:

- enhancing the board charter by including details of its processes for decisions without meetings, clearly defining the respective roles of the accountable authority and the employer on strategic issues such as remuneration policy and work, health and safety risks, and including behavioural expectations for board members;

- the board taking a more active role in approving key policies;

- providing board members with key policies and frameworks at induction;

- the board formally setting expectations for reporting to it by management;

- providing board members with consolidated progress results against all performance targets in the Corporate Plan; and

- annually reviewing the risk register.

OPH board arrangements to oversight compliance with key legislative and other requirements

15. The board has established fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance with key legislative and other requirements.

16. The ANAO made a number of suggestions for improvement in relation to:

- including a reference to the Statement of Expectations and Statement of Intent in future corporate plans and annual reports;

- expanding the existing Certificate of Compliance process to include compliance with enabling legislation and other legislative requirements, and including details of the basis for compliance;

- updating materials in the board induction pack;

- referencing OPH’s Corporate Plan in OPH strategy documents;

- reviewing the scheduling of audit committee meetings;

- systematically capturing instances of non-compliance;

- reviewing the board charter to better reflect the specific requirements of the PGPA Act; and

- considering the application of the entertainment and hospitality policy to board members.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 1.20

The Department of Finance update its guidance to accountable authorities having regard to the key insights and messages for accountable authorities identified in recent inquiries and reviews.

Department of Finance response: Agree.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.17

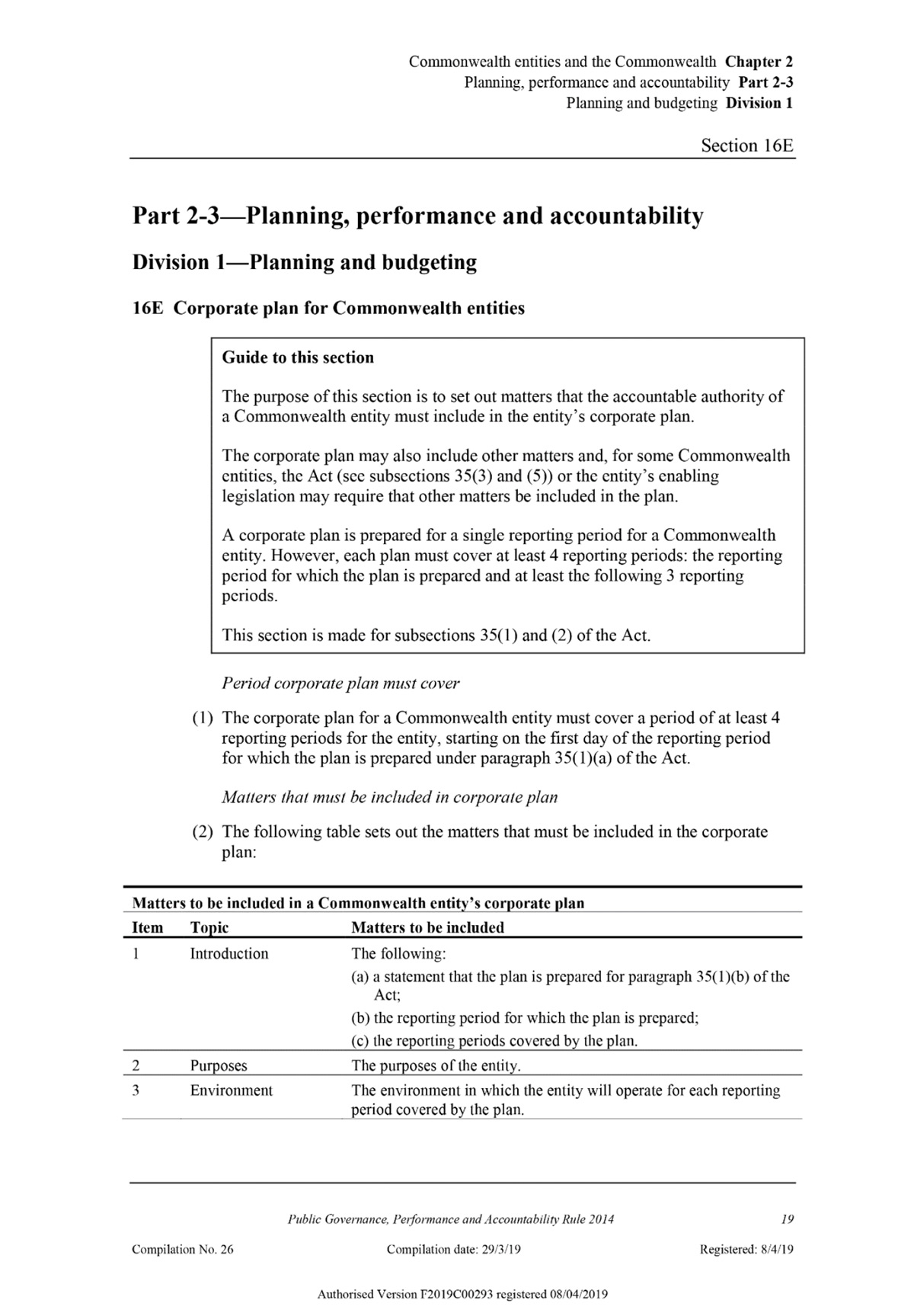

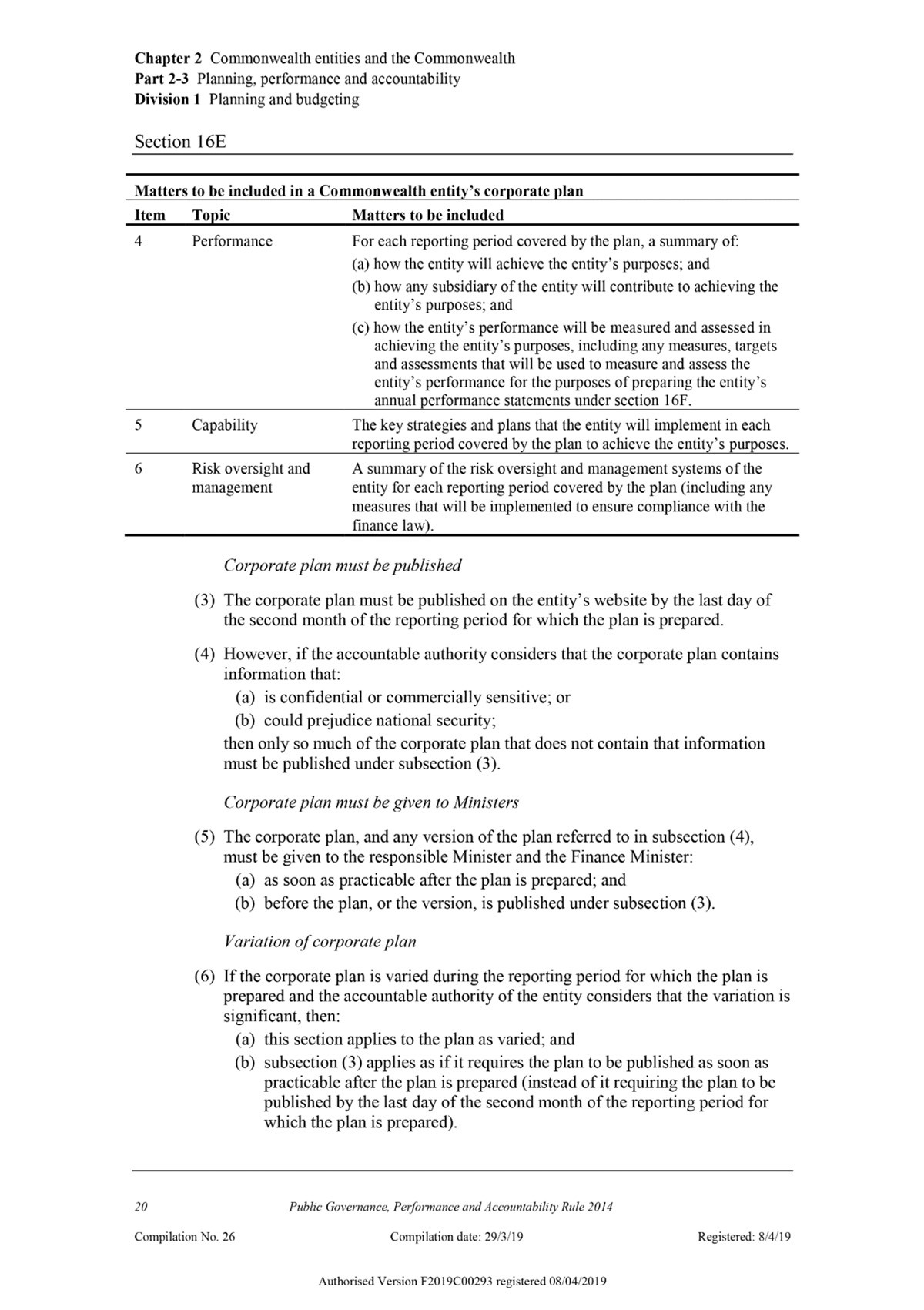

Old Parliament House ensure its corporate plan meets all the minimum requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014.

Old Parliament House response: Agree.

Summary of entities’ responses

17. The proposed report was provided to OPH which provided a summary response that is set out below. An extract of the report was provided to the Department of Finance which also provided a summary response that is set out below. The full responses from OPH and Finance are provided at Appendix 1.

Old Parliament House

18. OPH notes the ANAO’s very positive findings that:

- governance and oversight arrangements adopted by the OPH board are effective;

- OPH board governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative requirements and the board has structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance; and

- OPH has fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance and alignment with key legislative and policy requirements.

19. OPH notes the ANAO’s recommendation relating to ensuring OPH’s corporate plan meets all the minimum requirements of the Public, Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014. OPH is taking steps to ensure that all future OPH Corporate Plans are updated to include more dialogue around risk and capabilities across the four year period covered by the plan to ensure they meet the minimum requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014.

Finance

20. The Department of Finance agrees with the findings of the report.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

21. This audit is one of a series of governance audits that apply a standard methodology to the governance of individual boards. The four entities included in the ANAO’s 2018–19 board governance audit series are:

- Old Parliament House;

- the Special Broadcasting Service;

- the Australian Institute of Marine Science; and

- the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust.

22. Key messages from the ANAO’s series of governance audits will be outlined in an upcoming ANAO Insights product available on the ANAO website.

1. Background

Introduction

Governance boards

1.1 The governing board of a corporate Commonwealth entity is the accountable authority for the entity under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act)11, with responsibility for ‘leading, governing and setting the strategic direction’ for the entity.12

1.2 Around 60 corporate Commonwealth entities subject to the PGPA Act have governing boards, comprising a total of approximately 510 board positions.13 Corporate Commonwealth entities with governance boards vary significantly by function, and governance boards may also vary in their composition, operating arrangements, independence and subject-matter focus, depending on the specific requirements of their enabling legislation and other applicable laws.

Boards and corporate governance

Duties and roles

1.3 Sections 15 to 19 of the PGPA Act impose duties on accountable authorities in relation to governing the corporate Commonwealth entity for which they are responsible (see Box 1).14 As the accountable authority, members of Commonwealth governing boards are also officials under the PGPA Act and subject to the general duties of officials in sections 25 to 29 of the Act (see Box 1).15 Guidance issued to accountable authorities by the Department of Finance (Finance) observes that ‘each of these duties is as important as the others’.16

|

Box 1: Department of Finance, Guide to the PGPA Act for Secretaries, Chief Executives or governing boards (accountable authorities) – RMG 200, December 2016 |

|

General duties as an official You must exercise your powers, perform your functions and discharge your duties:

Like all officials, you must disclose material personal interests that relate to the affairs of your entity (section 29) and you must meet the requirements of the finance law. Accountable authorities who do not comply with these general duties can be subject to sanctions, including termination of employment or appointment. General duties as an accountable authority The additional duties imposed on you as an accountable authority are to:

|

Source: Department of Finance, Guide to the PGPA Act for Secretaries, Chief Executives or governing boards (accountable authorities) - RMG 200, Summary: Governing your entity [internet].

1.4 Boards play a key role in the effective governance of an entity. Corporate governance is generally considered to involve two dimensions, which are the responsibility of the governing board:

Performance — monitoring the performance of the organisation and CEO. This also includes strategy — setting organisational goals and developing strategies for achieving them, and being responsive to changing environmental demands, including the prediction and management of risk. The objective is to enhance organisational performance;

Conformance — compliance with legal requirements and corporate governance and industry standards, and accountability to relevant stakeholders.

… it is important to understand that governing is not the same as managing. Broadly, governance involves the systems and processes in place that shape, enable and oversee management of an organisation. Management is concerned with doing – with co-ordinating and managing the day-to-day operations of the business.17

1.5 The relationship between effective corporate governance and organisational performance is summarised in Box 2.

|

Box 2: The relationship between corporate governance and organisational performance |

|

Narrowly conceived, corporate governance involves ensuring compliance with legal obligations, and protection for shareholders against fraud or organisational failure. Without governance mechanisms in place — in particular, a board to direct and control — managers might ‘run away with the profits’. Understood in this way, good governance minimises the possibility of poor organisational performance … more recent definitions of good governance emphasise the contribution good governance can make to improved organisational performance by highlighting the strategic role of the board. Legal compliance, ongoing financial scrutiny and control, and fulfilling accountability requirements are fundamental features of good corporate governance. However, a high-performing board will also play a strategic role. It will plan for the future, keep pace with changes in the external environment, nurture and build key external relationships (for example, business contacts) and be alert to opportunities to further the business. The focus is on performance as well as conformance. The board is not there to simply monitor and protect but also to enable and enhance.18 In summary, research conducted by those working closely with boards suggests that:

|

Culture and governance

1.6 The interplay of the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ attributes of governance—and the criticality of board and organisational culture to an entity’s performance, values and conduct—have been central themes in notable Australian inquiries into organisational misconduct. These have included the 2003 Royal Commission into the failure of HIH Insurance20, the 2018 APRA Prudential Inquiry into the Commonwealth Bank of Australia21 and the 2019 Royal Commission into the financial services industry.22 While the specific focus of these inquiries was on financial institutions, their key insights on culture and governance have wider applicability and provide lessons for all accountable authorities, including governance boards. Many Auditor-General Reports have made findings consistent with those appearing in these inquiries.23

2003 HIH Royal Commission

1.7 The HIH Royal Commissioner defined corporate governance as the framework of rules, relationships, systems and processes within and by which authority is exercised and controlled in corporations—embracing not only the models or systems themselves but also the practices by which that exercise and control of authority is in fact effected. Justice Owen observed by way of introduction that:

A cause for serious concern arises from the [HIH] group’s corporate culture. By ‘corporate culture’ I mean the charism[a] or personality—sometimes overt but often unstated—that guides the decision-making process at all levels of an organisation …

The problematic aspects of the corporate culture of HIH—which led directly to the poor decision making—can be summarised succinctly. There was blind faith in a leadership that was ill-equipped for the task. There was insufficient ability and independence of mind in and associated with the organisation to see what had to be done and what had to be stopped or avoided. Risks were not properly identified and managed. Unpleasant information was hidden, filtered or sanitised. And there was a lack of sceptical questioning and analysis when and where it mattered.

At board level, there was little, if any, analysis of the future strategy of the company. Indeed, the company’s strategy was not documented and it is quite apparent to me that a member of the board would have had difficulty identifying any grand design …

… A board that does not understand the strategy may not appreciate the risks. And if it does not appreciate the risks it will probably not ask the right questions to ensure that the strategy is properly executed. This occurred in the governance of HIH. Sometimes questions simply were not posed; on other occasions the right questions were asked but the assessment of the responses was flawed.

1.8 More specifically, Justice Owen reported in chapter 6 of the report—which was dedicated to corporate governance—on key aspects of board operations and the importance of:

- clearly defined and recorded policies or guidelines;

- clearly defined limits on the authority of management, including in relation to staff emoluments;

- independent critical analysis by the board;

- recognition and resolution of conflicts of interest;

- dealing with governance concerns;

- maintaining control of the board agenda; and

- providing relevant information to the board.

2018 APRA Prudential Inquiry

1.9 The APRA Prudential Inquiry also dedicated substantial sections of its report to culture and governance. The review panel observed that:

Culture can be thought of as a system of shared values and norms that shape behaviours and mindsets within an institution. Once established, the culture can be difficult to shift. Desired cultural norms require constant reinforcement, both in words and in deeds. Statements of values are important in setting expectations but their impact is sotto voce. How an institution encourages and rewards its staff, for instance, can speak more loudly in reflecting the attitudes and behaviours that it truly values.24

1.10 The Prudential Inquiry associated weaknesses in board oversight and organisational culture with:

- insufficient rigour and urgency by the Board and its Committees around holding management to account in ensuring that risks were mitigated and issues closed in a timely manner;

- gaps in reporting and metrics hampered the effectiveness of the Board and its Committees; and

- a heavy reliance on the authority of key individuals that weakened the Committee construct and the benefits that it provides.25

2019 Hayne Royal Commission

1.11 The Hayne Royal Commission similarly incorporated a substantial chapter on culture, governance and remuneration in the final report. Commissioner Hayne reported that the evidence before the Commission showed that:

… too often, boards did not get the right information about emerging non-financial risks; did not do enough to seek further or better information where what they had was clearly deficient; and did not do enough with the information they had to oversee and challenge management’s approach to these risks.

Boards cannot operate properly without having the right information. And boards do not operate effectively if they do not challenge management.26

1.12 The Commissioner challenged governance boards to actively discharge their core functions, including the strategic oversight of non-financial risks such as compliance risk, conduct risk and regulatory risk:

Every entity must ask the questions provoked by the Prudential Inquiry into CBA:

- Is there adequate oversight and challenge by the board and its gatekeeper committees of emerging non-financial risks?

- Is it clear who is accountable for risks and how they are to be held accountable?

- Are issues, incidents and risks identified quickly, referred up the management chain, and then managed and resolved urgently? Or is bureaucracy getting in the way?

- Is enough attention being given to compliance? Is it working in practice? Or is it just ‘box-ticking’?

- Do compensation, incentive or remuneration practices recognise and penalise poor conduct? How does the remuneration framework apply when there are poor risk outcomes or there are poor customer outcomes? Do senior managers and above feel the sting?27

1.13 Key observations made in the Hayne Royal Commission on governance boards’ use of information, and the link between culture, governance and remuneration, are summarised in Box 3.

|

Box 3: 2019 Hayne Royal Commission |

|

Information going to boards and its effective use The Royal Commission observed that ‘it is the role of the board to be aware of significant matters arising within the business, and to set the strategic direction of the business in relation to those matters,’28 and identified ‘the importance of a board getting the right information and using it effectively’.29

Culture, governance and remuneration The Royal Commission highlighted the importance of governance boards focusing on entity remuneration policy, because ‘the remuneration arrangements of an entity show what the entity values’.31 The Commission concluded that ‘Culture, governance and remuneration march together.’32

|

Assessment of culture and governance by boards

1.14 Recommendation 5.6 of the Hayne Royal Commission—titled ‘changing culture and governance’—was that entities should, as often as reasonably possible, take proper steps to: assess the entity’s culture and its governance; identify any problems with that culture and governance; deal with those problems; and determine whether the changes it has made have been effective.

1.15 Underlining the criticality of organisational culture to entity performance, values and conduct, the Royal Commissioner emphasised that this recommendation, ‘although it is expressed generally, can and should be seen as both reflecting and building upon all the other recommendations that I make.’34

1.16 In a similar vein, the HIH Royal Commission had warned in 2003 of the dangers of a ‘tick the box’ mentality towards corporate governance, and the benefits of periodic review by boards of corporate governance practices to ensure their suitability.

The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act)

1.17 The objects of the PGPA Act include: to establish a coherent system of governance and accountability across Commonwealth entities; and to require the Commonwealth and Commonwealth entities to meet high standards of governance, performance and accountability.35

1.18 As discussed in paragraph 1.3 of this audit report, the PGPA Act includes both general duties of accountable authorities and general duties of officials. It also establishes obligations relating to the proper use of public resources (that is, the efficient, effective, ethical and economical use of resources).36 In so doing, the PGPA Act establishes clear cultural expectations for all Commonwealth accountable authorities and officials in respect to resource management. Finance, which supports the Finance Minister in the administration of the PGPA Act framework, has also issued a range of guidance documents on the technical aspects of resource management under the framework.

1.19 Finance issued a Resource Management Guide (RMG 200) in December 2016 to assist accountable authorities37, which is principally a factual and procedural guide with a focus on legal compliance. There is no equivalent in the Commonwealth public sector of resources built up over time—such as the ASX Corporate Governance Council’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations38 and Australian Institute of Company Directors resources—to support public sector governance boards. In consequence, public sector accountable authorities would need to rely on a combination of personal experience and other resources to supplement the guidance released by Finance. As discussed, the recent APRA Prudential Inquiry and Hayne Royal Commission have again highlighted the criticality of effective board governance, corporate culture and the interplay of the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ attributes of governance, and there would be merit in Finance issuing guidance which has regard to the key insights and messages of those inquiries directed to accountable authorities.

Recommendation no.1

1.20 The Department of Finance update its guidance to accountable authorities having regard to the key insights and messages for accountable authorities identified in recent inquiries and reviews.

Department of Finance response: Agree.

1.21 Finance agrees the recommendation, which reflects the work already undertaken by Finance, both prior to this audit, and subsequently.

1.22 Finance undertakes, on a continuous basis as part of our core business, the review and refinement of guidance material to support entities and accountable authorities under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 to meet their duties under the Act. We actively consider the outcomes of inquiries and reviews and apply these to guidance, tools and materials as appropriate.

1.23 Further, following the completion of the PGPA Act and Rule Independent Review, Finance has commenced reviewing guidance material to support a maturing framework through enhanced and strengthened guidance, including Resource Management Guide 200 referenced in the proposed report, with a strong focus on self-service and stewardship.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.24 This topic was selected for audit as part of the ANAO’s multi-year audit program that examines aspects of the implementation of the PGPA Act. This audit provides an opportunity for the ANAO to review whether boards have established effective arrangements to comply with selected legislative and policy requirements and adopted practices that support effective governance. The audit also contributes to the identification of practices that support effective governance that could be applied in other entities. This audit is one of a series of governance audits that apply a standard methodology to the governance of individual boards.

1.25 The four entities included in the ANAO’s 2018–19 board governance audit series are:

- Old Parliament House;

- the Special Broadcasting Service;

- the Australian Institute of Marine Science; and

- the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust.

Old Parliament House (OPH)

1.26 OPH39 was the seat of the Parliament of Australia from 1927 to 1988. After the Commonwealth Parliament transferred to the new Parliament House in 1988 the OPH building was left vacant for several years. In 1992, the building reopened and was run as a museum. The building was rebranded and re-opened in May 2009 as the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House (MoAD).40

1.27 OPH operates under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (Establishing Old Parliament House) Rule 2016 (OPH Rule) as a not-for-profit Corporate Commonwealth Entity. OPH became a Commonwealth Corporate Entity in July 2016. Prior to that time OPH had operated as a non-corporate Commonwealth entity with an advisory board. Establishing OPH as a corporate Commonwealth entity was intended to:

provide the most efficient and effective governance structure to promote Australia’s democracy and provide greater access for all Australians to our nation’s first parliament house and preserve it for future generations.41

1.28 OPH key functions include to conserve, develop and present the OPH building and collections; and to provide public programs and research activities related to Australia’s social and parliamentary history.42 OPH is accountable to the Minister for Communications and the Arts and is governed by a board.43 Under the OPH Rule, the board consists of the Board Chair, Deputy Board Chair, Director, and not more than four other members. At the time of the audit fieldwork there were six board members including the Director. The functions of the board set out in the OPH Rule are to decide the objectives, strategies and policies to be followed by OPH and to ensure the proper and efficient performance of OPH’s functions. The Director is responsible for the day-to-day administration of OPH.

1.29 OPH has a staff of approximately 74 (and 65 volunteers), receives around $16 million in appropriations, and generates approximately $2 million in own source revenue.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.30 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the governance board in Old Parliament House.

1.31 To form a conclusion against the audit objective the following high level criteria were adopted:

- the board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative requirements and the board has structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance; and

- the board has established fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance with key legislative and other requirements.

1.32 The audit examined the period July 2016 until March 2019.

1.33 Guidance to boards issued by the Department of Finance was reviewed by the ANAO having regard to the report of the 2019 Hayne Royal Commission44, which was released in the course of this audit, and other key reviews of board governance.45

Audit methodology

1.34 In undertaking the audit the ANAO:

- reviewed board and audit committee papers and minutes from July 2016 to December 2018;

- reviewed a range of relevant documentation including entity corporate plans, strategy documents, board and audit committee charters, risk registers, and conflict of interest declarations;

- interviewed current board members;

- attended two board meetings (September and November 2018) and one audit committee meeting (August 2018) as an observer; and

- reviewed relevant guidance and reviews on board and corporate governance.

1.35 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Audit Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $203,000. The team members for this audit were Grace Guilfoyle, Kelly Williamson, Shane Armstrong and Michelle Page.

2. OPH board governance arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative requirements and whether the board has structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance.

Conclusion

The board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative requirements and the board has structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has identified a number of opportunities for improvement relating to:

- enhancing the board charter by including details of its processes for decisions without meetings, clearly defining the respective roles of the accountable authority and the employer on strategic issues such as remuneration policy and work, health and safety risks, and including behavioural expectations for board members;

- the board taking a more active role in approving key policies;

- providing board members with key policies and frameworks at induction;

- the board formally setting expectations for reporting to it by management;

- providing board members with consolidated progress results against all performance targets in the Corporate Plan; and

- annually reviewing the risk register.

Are the board’s governance and administrative arrangements consistent with relevant legislative requirements and has the board structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance?

The board’s governance and administrative arrangements are consistent with relevant legislative requirements and the board has structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance.

2.1 Old Parliament House (OPH) operates under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (Establishing Old Parliament House) Rule 2016 (OPH Rule). The ANAO examined whether:

- the board’s governance and administrative arrangements were consistent with the enabling legislation; and

- whether the board had structured its own operations in a manner that supports effective governance.

2.2 The results of the ANAO’s assessment against each of these requirements and any suggestions for improvement are outlined below.

Consistency of governance and administrative arrangements with the OPH Rule

Membership and appointment of board members

2.3 The OPH Rule outlines the requirements for board membership, with the Arts Minister responsible for appointments. The Rule requires the appointment of:

- a Chair;

- a Deputy Board Chair;

- the Director; and

- not more than four other members.

2.4 The board met all of these requirements. During the period July 2016 to March 2019, board numbers varied from four to seven members. From 1 January 2017 until 21 November 2017 the board consisted of a Chair, a Deputy Chair, a Director, and only one other member. All board members had been appointed by the Minister for three year terms, consistent with the OPH Rule.

2.5 In respect to oversight of the appointments process, there is evidence that in 2016 the Director considered the skills needed for new board appointments and provided OPH’s portfolio department46 with advice on preferred candidates and skill requirements to support the initial establishment of the board as the accountable authority. In 2017 the Chair similarly provided the department with advice on preferred candidates and skill requirements for further appointments.

2.6 The OPH board charter provides a general expectation that board members have relevant skills and experience and OPH management maintain a document that outlines desirable board member skills. Some of the board members interviewed by the ANAO identified desirable skills to have on the board which were not held by the current members of the board.

2.7 There would be benefit in the board engaging with the department and the Minister in relation to the skill requirements for future board appointments.

Acting arrangements for the board Chair and board members

2.8 The OPH Rule enables the Arts Minister to: appoint a board member to act as the board Chair; appoint a person to act as a board member other than the board Chair; and appoint a person to act as the Director. OPH management advised the ANAO that there were no acting arrangements required for board members or the board Chair in the period covered by the audit.

Meeting requirements, quorum, presiding at meetings and voting

2.9 The OPH Rule states that the board Chair must convene such meetings of the board as are, in his or her opinion, necessary for the efficient conduct of its affairs, and that the board Chair must convene at least two meetings of the board in each calendar year.47 During the period reviewed by the ANAO the board met more frequently than these minimum requirements (three times in the period July 2016–December 2016) and four times in both 2017 and 2018.

2.10 In relation to board meetings, the OPH Rule specifies that a quorum is constituted by a majority of the board members for the time being holding office. The ANAO reviewed board meetings from July 2016 to December 2018 and a quorum was achieved at each board meeting.

2.11 The OPH Rule specifies that a question is decided by a majority of the votes of board members present and voting and that the board member presiding at the meeting has a deliberative vote and, in the event of an equality of votes, a casting vote. OPH advised the ANAO that all decisions were made by consensus during the period examined by the audit.

2.12 The OPH Rule specifies that the board Chair must preside at all meetings of the board at which he or she is present and if the Chair is not present, the Deputy Chair, if present, must preside at the meeting. If neither the Chair nor the Deputy Chair is present at a meeting of the board, the board members present must elect one of their number to preside at the meeting. The ANAO reviewed minutes from board meetings from July 2016 to December 2018. The board Chair attended and presided at all meetings.

Decisions without meetings

2.13 The OPH Rule allows for decisions to be taken without meetings, where a majority of the board members entitled to vote on the proposed decision indicate agreement with the decision; and that agreement is indicated in accordance with the method determined by the board. In November 2016 at its first full meeting the OPH board considered and approved a mechanism for decisions without meetings with what is known as “out of session approvals”. This involves emailing requests to board members to approve documents via a circular resolution.

2.14 The ANAO identified five instances of decisions being taken outside of meetings during the testing period, all of which met the legislative requirements and the mechanism agreed to by the OPH board. Decisions via circular resolution have been reported in board papers as a standing agenda item at each board meeting since June 2017. Reference to the legislative power allowing decisions to be taken without meetings was reflected in the board charter approved in 2016 and the revised 2018 board charter, but not details of the specific circular resolution method agreed and adopted by the board.

Opportunities for improvement

2.15 There is an opportunity for the OPH board to include, in the board charter, its circular resolution process for decisions without meeting. This would assist board members and those providing secretariat services to better understand expectations, particularly if new to the role.

Appointment and responsibilities of Director

2.16 The OPH Rule specifies that there is to be a Director appointed by the Arts Minister in the case of the first appointment, and otherwise by the board, with the Arts Minister’s agreement in writing. The Director of OPH was appointed on 2 April 2013 by the Arts Minister, and was reappointed by the board on 28 February 2018 (with the term to commence on 1 April 2018) following written approval from the Arts Minister. This process is consistent with the OPH Rule. In relation to the reappointment of the Director, OPH documentation indicates: the board discussed the performance of the Director; the Director provided the Chair of the OPH board with details of key achievements; and the Chair of the OPH board provided a letter of recommendation for reappointment to the Minister, which included some details of the Director’s achievements.

2.17 The OPH Rule further states that the Director is responsible for the day-to-day administration of OPH; that the board may give written directions to the Director about the performance of the Director’s role; and that the Director is to act in accordance with any policies determined, and any directions given, by the board. The board charter provides further guidance, specifying that the Director is accountable to the board for OPH’s performance, and the performance of its staff. The board delegated authority to the Director through an Instrument of Financial Delegations in July 2016.48

2.18 Typically, an entity’s accountable authority is the employer. OPH is a statutory agency under the Public Service Act 1999. The Director of OPH is the agency head and the employer of OPH staff. This means that the Director has responsibility for issues relating to employment and workplace health and safety (WHS).

Opportunities for improvement

2.19 In circumstances such as these, where the agency head and not the accountable authority is the employer, a challenge for a governance board is to clearly define the respective roles of the accountable authority and the employer on strategic issues, such as remuneration policy and WHS risks. These issues could be usefully drawn out in the board charter.

Outside employment

2.20 The OPH Rule states that if the Director is appointed on a full-time basis, that the Director must not engage in paid employment outside the duties of the Director’s office without the board Chair’s approval. OPH advised the ANAO that the Director has not engaged in outside employment. As discussed further in Table 3.1, conflict of interest declaration is a standing item at board meetings.

Board operations

2.21 Paragraphs 1.3 to 1.16 of this audit report outlined key insights on corporate governance and board operations, including in recent reviews and inquiries. Key themes include the need for:

- recognition and management of conflicts of interest;

- board members to question and challenge management;

- risk to be properly identified, considered and managed;

- boards to consider future strategy and key policies, including remuneration policy;

- boards to periodically assess corporate governance and organisational culture; and

- appropriate oversight of compliance.

2.22 The ANAO attended two board meetings at OPH (September and November 2018) and one audit committee meeting (August 2018). In those meetings, and through the review of board and audit committee papers and minutes, and interviews and interactions with board members, the ANAO observed board members collectively displaying a range of qualities and behaviours that indicated the existence of a positive governance culture at board level. These included:

- an openness to declaring conflicts of interest;

- a willingness to challenge management, engage in robust debate, explore various options and seek further clarification as needed;

- an ability to conduct meetings in a professional, collegiate and respectful manner;

- an understanding of their obligations as the accountable authority and the challenges facing the entity;

- a desire and commitment to act in the best interests of the entity; and

- a willingness to undertake sufficient preparation to enable meetings to be conducted in a productive manner.

2.23 At board meetings the ANAO observed discussion relating to OPH’s strategic direction, including the content of exhibitions and promoting and protecting democracy and the heritage building. This focus was also reflected in board papers and minutes. OPH exhibition content and governance (particularly risk management) are interconnected as exhibitions have the potential to give rise to reputational risk. Other risks related to content include the risks of a significant drop in visitor numbers; that programs and activities are unable to be delivered to an appropriate standard; that staff, contractors and public safety are not managed effectively; and that key assets and visitor experiences are not properly managed and maintained.

2.24 Board meetings observed included a verbal update from OPH’s Audit, Finance and Risk Committee49 and discussion of items included in the management reports provided in the board papers. The board papers include the Director’s report, which provides information on finance and risk, governance and WHS, learning, heritage, content, exhibitions and engagement, facilities and IT. The board papers also contain a finance report, and section reports from business areas including Exhibitions, Digital, Museum Experience, Museum Engagement, Learning; Heritage and Collections; Content; Facilities and Information Technology; People and Strategy; Digital; and Communications and Partnerships.

2.25 The ANAO observed that senior and other OPH staff attend board meetings to present details of activities. This enables board members to have direct engagement with staff. Board members advised the ANAO that their ability to access and question a cross section of staff provided them with additional comfort and assurance.

2.26 The remainder of this section examines specific aspects of the board’s governance and administrative arrangements.

Does the board have a charter?

2.27 A board charter is a written document that sets out such things as:

- the functions, powers, and membership of the board;

- role, responsibilities and expectations of members, both individually and collectively, and of management50;

- role and responsibilities of the chairperson51;

- procedures for the conduct of meetings52; and

- policies on board performance review.

2.28 A charter can provide a single reference point that clearly sets out the functions, powers and membership of the board, as well as roles, responsibilities and accountabilities, consistent with relevant legislative requirements. Board charters can also articulate the desired culture of the board and address the ‘soft attributes’ of governance discussed in chapter 1 of this audit report relating to board culture and behaviours, which are critical to good governance.53 The Australian Institute of Company Directors has indicated that:

In most organisations the governance framework is determined by the legislation that it has been created under…However, there are many aspects of modern governance which the board must consider and act upon that lie outside legal requirements. The board charter is one way of documenting these matters.54

2.29 OPH has a board charter, approved by the board in November 2016 and reviewed and approved again in September 2018.55 The charter provides an overview of the board and its role, including references to the enabling legislation and duties under the PGPA Act. The charter states that the board should ‘approve the objectives, strategies and policies to be followed by OPH, and ensure the proper and efficient performance of OPH’s functions’. OPH’s functions are stated in the Charter, including undertaking ‘other relevant tasks as the Arts Minister may require from time to time’. The charter includes information on the functions of OPH and the board, powers of the board, powers delegated to the Director, board composition, appointments and terms of board members, mechanisms to keep board members informed, the potential for a ministerial statement, and the capacity for access to independent advice. The charter also provides guidance on independence of board members, conflict of interest, outside employment, performance review, board procedures including quorum, voting, minutes, and resolutions without meetings, confidentiality, and additional board member obligations. The charter also advises that legal action can be taken in regards to breaches of statutory and fiduciary duties.

2.30 The 2016 Board Charter, updated in 2018 to include the name of the Museum of Australian Democracy, contains an extract from Division 3 of the OPH Rule which states that the board may conduct meetings as it thinks fit, subject to the Act. The same extract also contains procedures relating to the convening of meetings, quorum, presiding at meetings, voting at meetings, minutes and decisions without meetings.

2.31 The charter contains some behavioural guidance for board members relating to confidentiality and conflicts of interest. As discussed in chapter 1 of this audit, it is valuable for boards to address the range of ‘soft attributes’ of governance relating to board culture and behaviours, which are critical to good governance.

Opportunities for improvement

2.32 There is an opportunity for the OPH board to address in its charter key behavioural and cultural expectations for board members.

Does the accountable authority approve or have oversight of key policies?

2.33 The following policies, procedures and frameworks were reviewed and endorsed by the board during the period examined by the ANAO:

- Financial Delegations, approved by the board in July 2016;

- Risk Management Framework, approved by the board in March 2017;

- Investment Policy, approved by the board in June 2017;56

- Accountable Authority Instructions, approved by the board in December 2017; and

- Fraud Control Policy and Framework approved by the board in November 2018.

2.34 OPH does not have its own code of conduct, but its employees are bound by the APS Code of Conduct.

Opportunities for improvement

2.35 There is an opportunity for the OPH board to consider the policies it reviews and endorses with a view to ensuring the board periodically and systematically reviews and approves all key policies, particularly those that relate to the duties of an accountable authority. Board review of key policies and frameworks such as financial delegations, fraud, risk management, work health and safety can assist board members gain assurance that they are effectively discharging their duties as the accountable authority by setting the framework for compliance with relevant legislation. Having the board approve policies such as a code of conduct, remuneration and key quality assurance frameworks (if applicable) enables boards to influence behaviours and can be an important mechanism in communicating the desired culture within the entity. Recent reviews such as the 2018 APRA Prudential Review and the 2019 Hayne Royal Commission have highlighted that boards need to be alive to how incentives in organisations can drive inappropriate behaviours.57 Periodic board review of key policies can assist a board in its messaging to the entity about the organisational culture it wishes to promote.

Are board members provided with relevant information at induction?

2.36 Upon induction, board members are provided with a range of information. This includes:

- a high level overview of the role of OPH, which includes references to the PGPA Act and PGPA Rule establishing OPH, and the staffing structure;

- an overview of the audit committee, work health and safety obligations, and finance and funding;

- an overview of board meetings and board composition;

- overviews of business areas, including exhibitions and events, learning and visitor experience, heritage and collection management; and

- the board charter.

2.37 All board members indicated to the ANAO that they were satisfied with the information provided at induction.

Opportunities for improvement

2.38 At induction, there is an opportunity for OPH to provide board members with key policies and frameworks including those relating to delegations, risk, fraud, work health and safety and remuneration.

Has the board set expectations for reporting to it by management?

2.39 The board has not formally set expectations for reporting to it by management. Management reports to the board through standing agenda items and a standard format for presenting papers that has evolved over time. In March 2018, OPH changed how management reports were organised, moving from separate business area reports to one report directly aligned with Corporate Plan strategic objectives.58 There is evidence that the Director has sought feedback from the board on reporting. The board’s self-assessment questionnaire, further discussed in paragraph 2.41, included whether management reporting met board expectations, and OPH advised the ANAO that informal feedback is provided from the board Chair.

Opportunities for improvement

2.40 The corporate governance reviews discussed in chapter 1 of this audit report have consistently highlighted the importance of holding management to account. There is an opportunity for the OPH board to formally set expectations for reporting to it by management through its board charter. This could assist in ensuring that the board and management have a shared understanding of the board’s requirements and could assist the board in meeting its obligations as an accountable authority.

Is board performance collectively and individually assessed?

2.41 The board charter, approved in November 2016, and the revised board charter, approved in September 2018, state that each year the board will review its performance under the direction of the Chair. Board papers indicate there had been a performance assessment of the Director (who is also a board member) in 2017 and 2018.59 The board commenced its first formal self-assessment exercise in September 2018 and discussed the results in the November 2018 board meeting. OPH advised the ANAO that the assessment took place at this time because for the majority of 2017 the OPH board consisted of only four of its possible seven board members. Three previous members’ terms expired on 31 December 2016 and new members were not appointed until 21 November 2017. OPH further advised that when the board had less than the optimum number of members, the assessment of board performance was undertaken informally between the board Chair and individual members.

Does the board establish arrangements and expectations in relation to the board secretariat?

2.42 The OPH Rule and board charter do not provide requirements relating to secretariat arrangements. The board secretariat is provided by the OPH Director’s Executive Officer and OPH has advised that there is no documentation formalising this role. OPH maintains a checklist to support the secretariat role, which includes organising papers and arranging board member travel. ANAO interviews with board members indicate satisfaction with secretariat arrangements, with staff able to access information required and no dissatisfaction raised regarding timeliness of papers or accuracy of minutes.

Are all meetings minuted and do minutes record all decisions made and action to be taken?

2.43 The OPH Board Charter provides a requirement for the board to keep minutes of meetings. The ANAO reviewed minutes of board meetings held from July 2016 until December 2018. The minutes clearly indicate when items have been noted and when resolutions have been made by the board.

Do board meeting papers include draft minutes of previous meetings for board approval?

2.44 Consideration and approval of draft meeting minutes for the previous board meeting is a standing agenda item for board meetings. The board notes any changes and agrees to adopt the minutes as a true and accurate record of the previous meeting. This agreement is noted in the minutes. Board members advised that ANAO that they were satisfied with the minutes.

Has the board established procedures to handle decisions without meetings?

2.45 Sometimes it is necessary for boards to approve and action issues outside of scheduled meeting times. To effectively manage these instances it is useful to have established a process to support the making and recording of board decisions. As discussed in paragraph 2.13, OPH’s enabling legislation contains provisions for decisions without meetings.

2.46 OPH advised that board members communicate on board business through a variety of channels including private email. Board members and the entity should be cognisant of the need to ensure that information relating to the entity is handled and maintained in accordance with applicable Commonwealth information security and record keeping requirements. These requirements apply to communication channels such as emails, which are official records.

Is reporting of performance results listed as an agenda item at each meeting?

2.47 As discussed in Table 3.1, since March 2018 at each meeting the board is provided with a report from OPH business areas that is directly aligned with OPH’s Corporate Plan strategic priorities. Progress against most performance targets outlined in the Corporate Plan is included within individual section updates in board papers.

Opportunities for improvement

2.48 Providing board members with consolidated progress results against all performance targets outlined in the Corporate Plan would better support board members gaining an understanding of entity performance and aid decision-making. It would also support board member assurance over annual performance statement reporting.

Is the board provided with information to assist members to gain a good understanding of the entity’s strategic environment and risks?

2.49 OPH has established a risk management framework, first approved by the board in March 2017.60 The framework states that the executive management group is responsible for defining risk appetite, and that risk appetite and tolerance levels will be reviewed annually. It also states that the board is responsible for oversight of risk management, including setting strategic risks and providing expert advice and direction to senior management; and that the Director is responsible for establishing and maintaining the framework and ensuring governance mechanisms are in place that effectively identify, monitor and manage risks. The risk register, which includes information on risk appetite, was first reviewed by the board in May 2018 and subsequently approved in September 2018.61

2.50 The board receives information, including through management reports, on business areas and systems of risk management. For example, risk is discussed as part of the Director’s Report, in audit committee updates, in reporting on facilities, and as part of reporting on HR, Governance and Strategy.

2.51 The board approves and regularly reviews progress on OPH’s three year capital plan and capital works budget, which includes consideration of business cases for capital projects and their associated risk assessments. Overall the information provided is sufficient to enable members to have a good understanding of OPH’s strategic environment and risks. Board oversight in relation to risk management is discussed further in Tables 3.1 and 3.2.

2.52 The audit committee also considers risk through regular agenda items such as Security, Fraud and WHS. Additionally, it examines the system of oversight risk and management as part of its regular review of activities. The audit committee considered the risk management framework and policy in March 2017 and the risk register in May 2018.

2.53 The board demonstrates engagement in strategic planning through its approval of the Corporate Plan and Strategic Plan. Board members are also involved in the development of content for the museum and are shown exhibits. As discussed in paragraph 2.23 and footnote 61 the board advised the ANAO that consideration of content is interconnected with consideration of risk. OPH has advised that the board participated in a strategic planning day in March 2018.

2.54 Board members are drawn from a range of backgrounds, including former politicians, parliamentary staff, journalists and academics. This can be expected to support an understanding of OPH’s particular operating environment. The board advised the ANAO that it is comfortable with the level of attention and information provided to the audit committee regarding risk oversight.

Opportunity for improvement

2.55 There is an opportunity for the OPH board directly or through its audit committee to annually review the risk register. This process could be supplemented by a rolling review through the year.

In establishing the audit committee has the board considered structure, composition, size, skills and independence of mind of members to enable the committee to be effective and has the board established an audit charter outlining key requirements?

2.56 The OPH audit committee charter demonstrates the board’s consideration of these issues. The charter was approved by the board in August 2016 and reviewed by the board in September 2017 and November 2018, consistent with the charter requirement for annual review. The audit committee initially comprised three members, including an external Chair, who was not a board member or employee of OPH62, a Deputy Chair, who is a part of OPH management, and another member who is also a board member. From March 2017 an additional independent member joined the audit committee. This met the requirements of the charter, which requires a minimum of three members, appointed by the board, the majority of whom are not employees of OPH. The Chair of the board, Director of OPH, or CFO cannot be committee members. The charter provides guidance on collective and individual skill requirements, including financial literacy. At least one member is to have accounting or related experience, and a comprehensive understanding of accounting and auditing standards.

2.57 The charter outlines the committee’s responsibilities relating to financial reporting, performance reporting, systems of risk oversight and management, and systems of internal control. The charter allows for the Chair or Deputy Chair to determine who should be invited to attend meetings, and provides for access to information and personnel. The charter states that a representative of OPH’s internal audit service and the ANAO will be invited to attend all meetings as observers.

2.58 Relevant staff and internal and external auditors attend audit committee meetings. While there have been occasions where either OPH’s internal or external auditors have not been represented, this has been due to staff member availability, and appropriate apologies have been noted in the minutes.

Is there an internal audit function that provides assurance to the board and does the board have oversight of internal audit and the entity’s response to internal audit findings and recommendations?

2.59 OPH has an outsourced internal audit function.63 There were three internal audits undertaken during the period reviewed by the ANAO covering topics related to finance (payroll), work health and safety and information and communications technology. All internal audit reports are provided to the audit committee. The audit committee monitors the status of recommendations through an annual internal audit status report. From 2018, the status report has detailed what the recommendations are and management’s action, although it is not always clear from the response whether or not each recommendation has been agreed. Management responses to recommendations are also provided within the individual audit reports, and the ANAO notes that there is a low volume of recommendations to track.64

2.60 At board meetings the board receives a verbal report from the audit committee member who is also Deputy Chair of the board (as a standing agenda item) and minutes from the audit committee are tabled at board meetings. Internal audit is a standing agenda item at audit committee meetings, and the audit committee minutes provided to the board include updates on internal audit. The minutes provide general information on internal audit findings and management’s response, although details of recommendations are not always included. There is no record that internal audit reports have been provided to the board and internal audit has not directly reported to the board.

2.61 The internal audit program is reviewed and approved by the audit committee. There is no evidence that the board has been provided with the internal audit plan. OPH management advised the ANAO that the board has received verbal updates on the internal audit program.

2.62 Overall the board, through the audit committee, has oversight of the internal audit function and management’s response to internal audit findings and recommendations.

3. OPH board arrangements to oversight compliance with key legislative and other requirements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the board established fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance with key legislative and other requirements.

Conclusion

The board has established fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance with key legislative and other requirements.

Recommendation

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving Old Parliament House (OPH’s) compliance with the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO also made a number of suggestions for improvement including in relation to:

- including a reference to the Statement of Expectations and Statement of Intent in future corporate plans and annual reports;

- expanding the existing Certificate of Compliance process to include compliance with enabling legislation and other legislative requirements, and including details of the basis for compliance;

- updating materials in the board induction pack;

- referencing OPH’s Corporate Plan in OPH strategy documents;

- reviewing the scheduling of audit committee meetings;

- systematically capturing instances of non-compliance;

- reviewing the board charter to better reflect the specific requirements of the PGPA Act; and

- considering the application of the entertainment and hospitality policy to board members.

Has the board established fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance with key legislative and other requirements?

The board has established fit-for-purpose arrangements to oversight compliance with key legislation and other requirements.

3.1 The ANAO examined whether the Old Parliament House (OPH) board had established fit-for-purpose arrangements to ensure oversight of and compliance with:

- Ministerial Statements of Expectations and entity Statements of Intent (if applicable);

- selected parts of the entity’s enabling legalisation; and

- selected parts of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) relating to: duties of accountable authorities; duties of officials; the corporate plan; financial statements; annual report and audit committees.

3.2 The results of the ANAO’s assessment against each of these requirements and any suggestions for improvement are outlined below.

Oversight of, and compliance with, Statement of Expectations and Statement of Intent

3.3 Sometimes entities are provided with a Statement of Expectations from their Minister. These statements generally outline the Minister’s key priorities and set out the Government’s expectations for the entity, including the priorities it is expected to observe in conducting its operations. Entities then respond to their Minister as to how they intend to deliver the identified priorities through a Statement of Intent.65

3.4 On 17 September 2018 the Minister for Communications and the Arts provided the Museum of Australian Democracy at OPH with a Statement of Expectations, outlining the Minister’s priorities. The board approved a Statement of Intent on 29 November 2018 to send to the Minister in response. The Statement of Expectations and Statement of Intent are on OPH’s website. OPH was previously issued with a Statement of Expectations in June 2017 and responded with a Statement of Intent.

3.5 Board papers and minutes reflect consideration and approval of Statements of Intent in September 2017 and November 2018. OPH does not refer to either the Statement of Expectations or Statement of Intent in its 2017–18 and 2018–19 corporate plans or annual report for 2017–18. Board papers reviewed for the period July 2016 to December 2018 demonstrate that the board was provided with information in relation to matters outlined in the Statements. Based on this high-level review, the OPH board has demonstrated that it has a process in place to have regard to the Statement of Expectations.

Opportunities for improvement

3.6 There is an opportunity for OPH to include a reference to its Statement of Expectations and Statement of Intent (and related progress against it) in future corporate plans and annual reports.

Oversight of, and compliance with, elements of enabling legislation

3.7 OPH is required to comply with its enabling legislation, the OPH Rule. Under the OPH Rule, the Director is responsible for the day-to-day administration of OPH, in accordance with any policies determined, and any directions given, by the board. Neither the OPH board nor OPH management have defined what day-to-day administration includes. The ANAO’s assessment of the OPH’s board oversight of, and compliance with, selected key requirements of the OPH Rule is outlined below.

3.8 The ANAO has seen no formal mechanism for monitoring and reporting compliance with the OPH Rule. Matters addressed within the OPH Rule, such as board member appointment, remuneration, reappointment of the Director, and contact with the Arts Minister are reported via the Director’s Report, and on occasion through the Human Resources and Governance report. The Certificate of Compliance, presented to the audit committee annually and discussed with the board, focuses on the PGPA Act rather than the enabling legislation. Compliance processes in relation to the PGPA Act are discussed in Tables 3.1 and 3.2 of this audit report.

3.9 OPH has documentation relating to other legislative and policy compliance, including for the Australian Government Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF). PSPF compliance information was provided to the audit committee, and reported to the board in September 2018. Discussions at the audit committee indicate that the committee has considered the requirements of updates to the PSPF.66 There is no central register of compliance breaches.

3.10 Board members advised the ANAO that they gain assurance on compliance with the enabling legislation from their individual and collective experience in reviewing management reports, questioning entity management and their knowledge of the policies, procedures and processes in place that support compliance.

Opportunities for improvement

3.11 There is an opportunity for OPH to expand its existing Certificate of Compliance process to include its enabling legislation and other legislative requirements to assist in ensuring the board has oversight of compliance with legislation. Including details of the basis for compliance—for example, what controls are in place and how they are tested—would assist board members gain a greater understanding of the robustness of internal controls supporting legal compliance. Without such information the potential exists for board members to have a gap in their understanding of OPH’s compliance processes.

Oversight of, and compliance with, selected PGPA Act requirements

3.12 The PGPA Act sets out requirements for the governance, reporting and accountability of Commonwealth entities The PGPA Act is principles based and the accountable authority has the flexibility to establish the systems and processes that are appropriate for their entity. The Department of Finance (Finance) provides entities with guidance on how to meet the various requirements of the PGPA Act and Rule including providing examples of how entities can demonstrate compliance.

3.13 The ANAO examined whether the OPH board established fit-for-purpose arrangements for oversight of, and compliance with, the following parts of the PGPA Act and PGPA Rule relating to corporate governance:

- general duties of an accountable authority;

- duties as an official; and

- specific requirements relating to corporate plans, annual reports and the audit committee.

General duties as an accountable authority

3.14 The general duties imposed on an accountable authority, which are considered in the following section, are to:

- govern the Commonwealth entity (section 15);

- establish and maintain appropriate systems relating to risk management and oversight and internal controls (section 16);

- encourage officials to cooperate with others to achieve common objectives (section 17);

- take into account the effects of imposing requirements on others (section 18); and

- keep their Minister and the Finance Minister informed (section 19).67

(a) Duty to govern the Commonwealth entity (section 15)

3.15 Finance guidance states that governing an entity includes:

- promoting the proper (efficient, effective, economical and ethical) use and management of public resources;

- promoting the achievement of the purposes of the entity;

- promoting the financial sustainability of the entity;

- taking account of the effect of decisions on public resources generally; and

- establishing appropriate systems of risk management and internal control, including measures directed at ensuring officials comply with the finance law (such as accountable authority instructions and delegations).68

3.16 The ANAO’s assessment in relation to the OPH’s board requirement to govern is outlined in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Duty to govern the entity (PGPA Act section 15)

|

Finance guidance |

ANAO observations and opportunities for improvement where applicable |

|

To address requirements relating to promote the proper (efficient, effective, economical and ethical) use and management of public resources. This can include establishing:

Promote the achievement of the entity’s purposes. This includes:

Promote financial sustainability by managing the risks, obligations and opportunities relevant to their entity. Take account of the effect of decisions on public resources generally. Establish appropriate systems of risk management and internal control (discussed in more detail in Table 3.2).

|

Observations Upon induction, OPH board members are provided with information outlining the role of the board and its principal functions and responsibilities including governance. OPH maintains an instrument of Financial Delegations, last approved by the board in July 2016. The instrument provides delegation of powers in relation to approving expenditure and entering into contracts, and other powers, including banking and borrowing. OPH has established practices that support governance, the proper use of resources and appropriate behaviours including accountable authority instructions, a board charter and conflict of interest declaration as a standing agenda item at board meetings. OPH has established an Audit, Finance and Risk Committee (audit committee) which reviews the appropriateness of OPH’s financial reporting, performance reporting, system of risk oversight and management and systems of internal control. The board discussed and approved OPH’s 2018–19 Corporate Plan and the plan sets out OPH’s purpose and the activities it undertakes to achieve its purpose. As referred to in paragraph 3.5, the plan does not include reference to either the Statement of Expectations or Statement of Intent. In addition, while reporting in board papers since the beginning of 2018 has directly aligned with the strategic objectives of the corporate plan, reports do not provide updates on progress against all corporate plan performance targets. OPH also has a Strategic Framework 2018–23 which aligns with the strategic priorities in the corporate plan. Board meeting papers and minutes provide evidence of oversight of OPH’s various activities through standing agenda items that include a Director’s report, workplace health and safety report, audit committee update, finance report, and section reports from business areas including Exhibitions, Digital, Museum Experience, Museum Engagement, Learning; Heritage and Collections; Content; Facilities and Information Technology; People and Strategy; Digital; and Communications and Partnerships. The board has established systems for, and receives reports on, risk management and internal control (discussed in more detail in Table 3.2). Financial risks are included in OPH’s risk register, and the Director’s Report regularly provides an update on emerging financial issues. Board members have advised that they gain assurance on compliance from their individual and collective experience in reviewing management reports, questioning entity management and their knowledge of the policies, procedures and processes in place that support compliance. |

|

Opportunities for improvement There is an opportunity to update the material in the board induction pack and reference OPH’s Corporate Plan in OPH strategy documents. The board member briefing pack refers to new board members being provided with ‘company policies’ and also being briefed on policies. It also refers to the ‘company’s’ personnel. OPH is not a Commonwealth company and the language should be updated to better reflect the requirements of a corporate Commonwealth entity. It is not clear from documents provided what information in relation to policies is provided to new board members. OPH advised the ANAO that the briefing pack will continue to be updated as new board members join, and that in the future key policies will be included in the pack. OPH’s 2018–19 Corporate Plan refers to OPH’s Strategic Framework 2018–23 but the framework document does not directly reference OPH’s corporate plan. Under the Commonwealth performance framework the corporate plan is intended to be an entity’s primary planning document, and there is an opportunity for OPH to more directly reflect the relationship between these two key documents in future OPH strategy documents. In addition, OPH’s 2018–19 Corporate Plan did not meet all minimum requirements of the PGPA Rule 2014. Specifically the plan did not address each of the four reporting periods covered by the plan in each of the capability and risk oversight and management systems section of the corporate plan. Entities were first required to publish corporate plans by 31 August 2015. After four cycles OPH should ensure its next corporate plan meets the minimum requirements outlined in the PGPA Rule.

|

|

Source: Department of Finance, Guide to the PGPA Act for Secretaries, Chief Executives or governing boards (accountable authorities) - RMG 200, Summary: Governing your entity [Internet], Department of Finance, December 2016, available from https://www.finance.gov.au/resource-management/accountability/accountable-authorities/ [accessed March 2019] and ANAO analysis.

Recommendation no. 2

3.17 Old Parliament House ensure its corporate plan meets all the minimum requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014.

Old Parliament House response: Agree.

3.18 OPH agrees with this recommendation. Future OPH Corporate Plans will be updated to include more dialogue around risk and capabilities across the four year period covered by the plan to ensure they meet the minimum requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014.