Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Early Intervention Services for Children with Disability

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Social Services' administration of Early Intervention Services for Children with Disability.

Summary and recommendations

Early Intervention Services for Children with Disability

1. Initiatives to improve the social and economic outcomes for individuals with disability and their families are shaping structural reform within the disability sector. Key reforms include the move away from a welfare-driven jurisdictional model, to a market-driven national approach. Within these reforms, disability services are changing to emphasise personalised and self-directed support with government grants or block funding redirected from disability service groups to the individual to purchase services and resources from preferred suppliers.

2. Implemented in 2008, Early Intervention Services for Children with Disability (EISCD) incorporates access to a combination of diagnostic, therapeutic and education intervention services. The program is demand-driven with eligibility based on administrative and diagnostic requirements.1 It operates to augment services delivered under the Commonwealth State and Territory Disability Agreement2 and is one of several disability initiatives that will, over time, transition to the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

3. The objective of the EISCD is to provide access to early intervention services for eligible children to assist them achieve their potential. There are two EISCD components with similar service delivery arrangements, the:

- Helping Children with Autism (HCWA) package which commenced in 2008 and targets children with autism; and

- Better Start for Children with Disability (Better Start) initiative which commenced in 2011 and targets children with one or more of 16 disabilities.3

4. The EISCD consists of an individual funding package of $12 000. This enables families, within certain constraints, to purchase approved early intervention services from service providers who best suit their child’s needs, as well as resource items which support their child’s development. An additional $2000 per child is paid to families living in areas defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) as outer-regional, remote and very remote, to assist them access services. Grant funding is also provided to community groups to manage the administrative arrangements such as registering children for the program and delivering group activities such as playgroups and community events to support the inclusion of children with disabilities.

5. The Australian Government committed $608 million to the EISCD between 2008 and 2016. This is made up of $436 million allocated to HCWA from 2008 and $172 million for Better Start from 2011. The Department of Social Services (DSS) has overall responsibility for the program.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Social Services’ administration of Early Intervention Services for Children with Disability. To form a conclusion against this objective, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) examined the Department’s:

- arrangements for the registration of eligible children and service providers, and access to and utilisation of funded services;

- approach to managing entry requirements, forecasting demand, and monitoring utilisation and expenditure;

- management of the transition of eligible children to the NDIS in trial sites; and

- systems for supporting program administration and the assessment of program performance.

Overall conclusion

7. DSS’ administration of the EISCD is effective in some areas, but overall could be improved. To facilitate access to the program, the Department established a national registration process for eligible children and service providers. Service delivery is supported by program guidelines, but data is not collected on whether service delivery is consistent with the guidelines. Access to, and the utilisation of services, has remained reliant on the proximity to DSS registered service providers, with claims and expenditure for eligible children living in regional and remote areas being disproportionately low when compared to claims by children living in urban areas. This is despite additional funding being made available to children in these areas to assist with the cost of accessing services.

8. Critical to the ongoing financial sustainability of a demand-driven program is the capacity to manage entry requirements. A combination of administrative and diagnostic requirements determines EISCD access. The administrative requirements are clearly defined, but the HCWA diagnostic entry requirements have varied over time, broadening the eligibility criteria for the program. DSS has not accurately forecast demand for services funded through the two components of the program, resulting in annual budget overruns of between $1.5 million and $18 million for HCWA and under-expenditure of between $3.9 million and $19.3 million for Better Start.

9. DSS’ approach to transitioning children from the EISCD to the NDIS demonstrated limited strategic planning. The need to assist families with timely, clear and consistent information and support prior to the commencement of the NDIS trial should have been identified as part of DSS’ planning for the transition of children from the EISCD to the NDIS. Advice to families about choosing when to transition to the NDIS encouraged families to retain EISCD entitlements to maximise expenditure prior to transitioning. Some families took up the option to delay their transition and increased their annual expenditure to maximise EISCD benefits prior to transitioning. Subsequently, DSS retracted their initial advice, and placed a time limit on families transiting. Families were confused by the conflicting advice and their options. To support families DSS could have made greater use of the national network of registration service providers, in particular those that operate in the jurisdictions with NDIS trial sites. The agreements were varied with these providers to include direct assistance to families transitioning to the NDIS 13 months after the NDIS trial commenced in South Australia and one month after the Australian Capital Territory trial commenced. As at February 2016, agreements in only two jurisdictions had been varied, even though NDIS trial sites operate in each state and territory.

10. An information technology system has been developed by DSS to support the administration of the program, including the processing of claims for services, the purchase of resources and the reporting of program utilisation. DSS uses data captured in the system to report on the number of children registered to receive support, service utilisation and expenditure. Nevertheless, reporting in relation to the program has focused on the utilisation of DSS administered services only, rather than the impact of the related activities funded through the package of services available to EISCD children and their families. There would be benefit in DSS working with the Department of Health and the Department of Education and Training to collect data about outcomes and report on the impact of the combination of available intervention services.

Supporting findings

11. In July 2015, there were 2620 registered service providers for HCWA and 2368 for Better Start. Through these providers over 1.8 million services had been delivered. Service access and use is concentrated within particular early intervention services and locations. The majority of service claims are made by families living in major cities and in higher socio-economic areas. Access data indicates that the number of claims per child declines where children are living in regional and remote locations. This indicates that these families, although registered and eligible to access services, may either be unable to access services for their child, or that their access to services is limited. To June 2015, DSS had provided additional allowances of approximately $16 million to families living in these locations to support access to services.

12. The EISCD is a demand-driven program and entry requirements have a causal relationship with program use and expenditure. From the commencement of the program, EISCD entry requirements have been governed by administrative and diagnostic criteria.4 Over time, changes have been made to the entry criteria without corresponding adjustment to the forecast uptake of the program and financial modelling, or advice to Government on better management of demand.

13. The EISCD is one of several Australian Government administered programs that will progressively transition to the NDIS. DSS’ overall approach to the transitioning of EISCD children to the NDIS lacked coordination. The approach was reliant on assistance from the DSS helpdesk supported by two newsletters (October and November 2013), one information session for parents in each trial site, and two information sessions for registered service providers. The advice to families in trial sites varied over time, with the initial advice providing choice over when to transition to the NDIS, resulting in some families bringing forward EISCD expenditure to maximise benefits for their children prior to transitioning. After advising families they could retain their EISCD entitlements, DSS then retracted this initial advice, and placed a time limit on children transitioning. DSS could have made greater use of the registration service providers to support families in NDIS trial sites to transition eligible children to the NDIS.

14. While DSS collects data about service utilisation, services accessed and resource items purchased through the EISCD, reporting of program performance has largely focused on the utilisation of DSS administered services rather than the outcome of the interventions. There would be benefit in DSS working with the Department of Health and the Department of Education and Training, to collect data about, and report on, the impact of the package of intervention services available to EISCD children and their families.

Recommendations

15. The audit identified several areas where DSS could have more effectively administered the EISCD. This includes: administration of service delivery arrangements to support improved access; management of entry requirements, forecasting demand, and monitoring utilisation and expenditure on EISCD services; transitioning children from the EISCD to the NDIS; and program performance reporting.

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.18 |

To better understand the barriers to accessing services funded through the EISCD and to improve access to services for children living outside of urban areas, the ANAO recommends that DSS consult with service providers and EISCD families about access issues and provides advice to the responsible Minister about how to improve access to services. Department of Social Services response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.44 |

To assist the Australian Government in the development of policy frameworks and to make informed decisions regarding the future delivery of the EISCD within financial allocations, the ANAO recommends that DSS provide a comprehensive analysis of EISCD forecast utilisation and expenditure to Government. Department of Social Services response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 4.13 |

To assist families to transition to the NDIS, the ANAO recommends that DSS work with the registration providers, state and territory governments and the NDIA to develop clear, timely and consistent advice for families as the NDIS is implemented nationally. Department of Social Services response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No 4 Paragraph 5.15 |

Consistent with the requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 to report against program outcomes and to assist the Australian Government with making informed decisions about the EISCD, the ANAO recommends that DSS collate and report on the impact of the package of intervention services available to EISCD children and their families. Department of Social Services response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity response

16. The full response is at Appendix 1. The summary response is as follows:

DSS welcomes the findings outlined in the Section 19 Audit Report on Early Intervention Services for Children with Disability. DSS agrees with all four recommendations and will take appropriate steps to address these matters.

DSS notes that Early Intervention programmes have been identified to transition to the NDIS. The programmes commenced transition in trial sites in 2013 and will continue to transition, with full scheme phasing commencing in July 2016.

All work in response to this report will be undertaken in the context of the transition of the programmes to the NDIS.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 There is a broad range of disabilities that can affect children, including disabilities that impact on a child’s health, their movement, and/or their ability to learn and communicate. The ABS in Australian Social Trends reported disability rates of 3.4 per cent for children aged from birth to four years, increasing to 8.8 per cent of children aged from five to 14 years nationally. Boys were more likely to have a disability than girls, with 8.8 per cent of boys aged from birth to 14 years with a disability, compared to 5 per cent of girls of the same age.5

1.2 The impact of having a child with a disability varies across families, although ‘families with at least one young child with a disability…tend to have lower socio-economic status, labour force participation and income than other families with young children’.6 The nature and severity of a child’s disability, the family structure and dynamics, as well as individual characteristics and the socio-economic circumstances of the family, all influence the nature of services that families may need. In this respect, disability services have been moving increasingly to models based on providing individualised choice and flexibility to clients based on their circumstances.

Early Intervention Services for Children with Disability

1.3 In 2007, the Australian Government announced the establishment of a package of services to support children with autism, their parents and carers (Helping Children with Autism, or HCWA). Funding of $190.7 million was committed for four years from July 2008. Subsequently, an additional $245 million was made available for continued delivery of the HCWA package from 2012–16, amounting to total funding of approximately $436 million for the period 2008–16. The package of services was to operate in addition to, and complement services delivered by the state and territory governments under the Commonwealth State and Territory Disability Agreement.7

1.4 In July 2011, in addition to the HCWA services, the Australian Government allocated $147 million to June 2015, with an additional $25 million to June 2016, to provide access to early childhood intervention services for children with 16 specified disabilities.8 This is known as Better Start for Children with Disability (or Better Start).9 These two components constitute the EISCD administered by the Department of Social Services (DSS).

1.5 The overall objective of Early Intervention Services for Children with Disability is to provide access to early intervention services for eligible children, up to seven years of age, to assist them achieve their potential. The main component of the EISCD is an individual funding package of $12 000 per child that can be used to purchase early intervention services, including one on one services or small group activities delivered by registered service providers. Up to 35 per cent of the funding can also be used to buy resource items, such as books or learning aids, which support the child’s development. Funds for these services and resources are held by DSS which makes payments to service providers on behalf of families. No more than $6000 of the individual funding package can be spent in any one financial year. For children living in outer-regional, remote or very remote locations, supplementary funding of $2000 is available to help families with the cost of accessing services.10 DSS pays this funding directly to the families of eligible children.

1.6 The Australian Government also provides support to eligible children through Medicare. EISCD-specific Medicare rebates have been created to assist with the cost of:

- developing treatment and management plans;

- allied health diagnostic/assessments—funding for four appointments; and

- allied health services—funding for 20 appointments.11

1.7 In addition to funding for specialist services for children, DSS funds community based organisations to deliver a range of group activities to support the inclusion of children with disability and their families within mainstream services and activities.12 DSS is also responsible for grants to community groups to deliver education and support services for children and families, including parent workshops, and the Autism Specific Early Learning and Care Centres. The Department of Education and Training also receives Australian Government funding to deliver services for teachers and parents of children with autism. Table 1.1 presents a summary of EISCD services available to eligible children.

Table 1.1: Summary of EISCD services

|

|

|

|

EISCD services for children |

|

|

EISCD services common to both HCWA and Better Start: Individual funding packages: up to $12 000 (maximum $6000 in any one financial year) to pay for early intervention services delivered by approved service providers and to purchase resources. Outer Regional, Remote and Access Support Payment: a one-off support payment for families living in outer-regional and remote areas as defined by the ABS to assist with the cost of accessing services. Early Days Workshops: provide autism or disability specific education and services for parents and carers. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Liaison Officers (ALO) project: funding for ALOs aims to increase Indigenous family access to HCWA and Better Start services. Website content: autism and disability-specific online material for parents, carers and families. |

|

|

HCWA and Better Start specific support elements |

|

|

HCWA |

Better Start |

|

Autism advisors: confirm eligibility, register eligible children and provide families with information and contact details of DSS registered service providers. The autism advisor function is delivered by the peak autism associations in each state/territory under a grant agreement with DSS. Playgroups: provide play activities suited to the needs of children aged 0–6 years with autism or autism-like symptoms. Six Autism Specific Early Learning and Care Centres (ASELCCs): provide early learning programs and specific support for children with autism, or autism like symptoms, in long day care centres. |

Registration and Information Service: confirm eligibility, register eligible children and provide families with information and contact details of DSS registered service providers. The Registration and Information Service is operated by Carers Australia nationally under a grant agreement with DSS. Playgroup Community Events: promotes community playgroups to parents of children with disability nationally. |

|

EISCD services—administered by other entities |

|

|

Medicare items: funding for a treatment and management plan; up to four allied health diagnostic services to assist in the preparation of the treatment plan; and up to 20 allied health treatment services per eligible child (in total). Positive Partnerships (HCWA eligible children only): provides professional development for teachers and other school staff, and workshops and information sessions for parents and carers to improve educational outcomes for children with autism. |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Social Services material.

Transition to the National Disability Insurance Scheme

1.8 From July 2013, eligible children are being transferred from the EISCD to receive support under the NDIS. The NDIS operates as a stand-alone model and once a child has an approved individualised plan with the NDIA13, that child is no longer eligible for disability services from the EISCD or the respective state or territory government.14 The EISCD will continue to operate until the full national implementation of the NDIS in July 2019, as outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: NDIS implementation schedule

|

Location |

Implementation schedule |

|

Tasmania |

Commenced on 1 July 2013 for eligible young people aged 15 to 24 years. There is a state-wide approach to transitioning government program participants and new participants into the scheme by July 2019. |

|

South Australia |

Commenced on 1 July 2013 for children aged five years and under. All participants are expected to transition into the scheme by July 2018. |

|

Victoria |

Commenced in the Barwon area of Victoria on 1 July 2013 for people to age 65. From 1 July 2016, the NDIS will begin to be available across other areas of Victoria. |

|

New South Wales |

Commenced in the Hunter area of New South Wales on 1 July 2013 for people to age 65, and the Nepean Blue Mountains area from July 1 2015 for children and young people less than 18 years of age. From 1 July 2016, a staged geographical transition combined with a programmatic transfer of some cohorts, is expected to be completed by July 2018. |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

Commenced on 1 July 2014 for people to age 65. All eligible participants are expected to transition to the scheme by July 2016. |

|

Northern Territory |

Commenced in the Barkly area on 1 July 2014 for people to age 65. From July 2016, the NDIS will progressively be implemented across the NT and by July 2019, all eligible residents will be covered. |

|

Western Australia |

Commenced in the Perth Hills area of Western Australia on 1 July 2014 for people with disability to age 65. Western Australia is trialling two different disability service models during the two year NDIS trial, the My Way model administered by the Western Australia Disability Services Commission and the NDIS model administered by the NDIA. The outcome of these trials will determine how Western Australians will receive disability services from July 2016. |

|

Queensland |

In September 2015 the Commonwealth and Queensland Governments announced an early transition to the NDIS in Townsville and Charters Towers for children and young people less than 18 years of age, and Palm Island for all people to age 65. The NDIS will progressively be implemented across Queensland over a three year period from 1 July 2016. |

Source: ANAO analysis of National Disability Insurance Agency data, available from <http://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/our-sites>.

Audit approach

1.9 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Social Services’ administration of Early Intervention Services for Children with Disability. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO examined the Department’s:

- arrangements for the registration of eligible children and service providers, and access to and utilisation of funded services;

- approach to managing entry requirements, forecasting demand, and monitoring utilisation and expenditure;

- management of the transition of eligible children to the NDIS in trial sites; and

- systems for supporting program administration and the assessment of program performance.

Audit methodology

1.10 The audit included an examination of DSS’ records relating to the administration of the program. Client and transactional data extracted from DSS’ supporting information technology system was also analysed, and interviews were held with relevant DSS staff and key stakeholders. The interviews provided the ANAO with feedback on DSS’ administration of key tasks nationally, including the provision of policy advice, response to program queries, and the management of service payments and reporting requirements.

1.11 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $722 463.

2. EISCD registration and service delivery arrangements

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the arrangements for the registration of eligible children and service providers, and access to and utilisation of funded services.

Conclusion

- DSS has developed systems and processes for the registration of children and eligible service providers. Program access and registration of eligible children is managed by service provider organisations contracted by DSS, while professionally accredited and qualified service providers are also registered by DSS to deliver interventions.

- The program guidelines promote a collaborative, multidisciplinary and/or transdisciplinary approach to service delivery, but DSS does not collect data on whether service delivery is consistent with this approach.

- Access to and the utilisation of services has remained reliant on the proximity to DSS registered service providers with claims per child and annual expenditure declining for children living in regional and remote areas.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation focused on DSS better understanding the barriers to accessing services and providing advice to the responsible Minister about improving access for children living outside of urban areas.

EISCD service delivery model

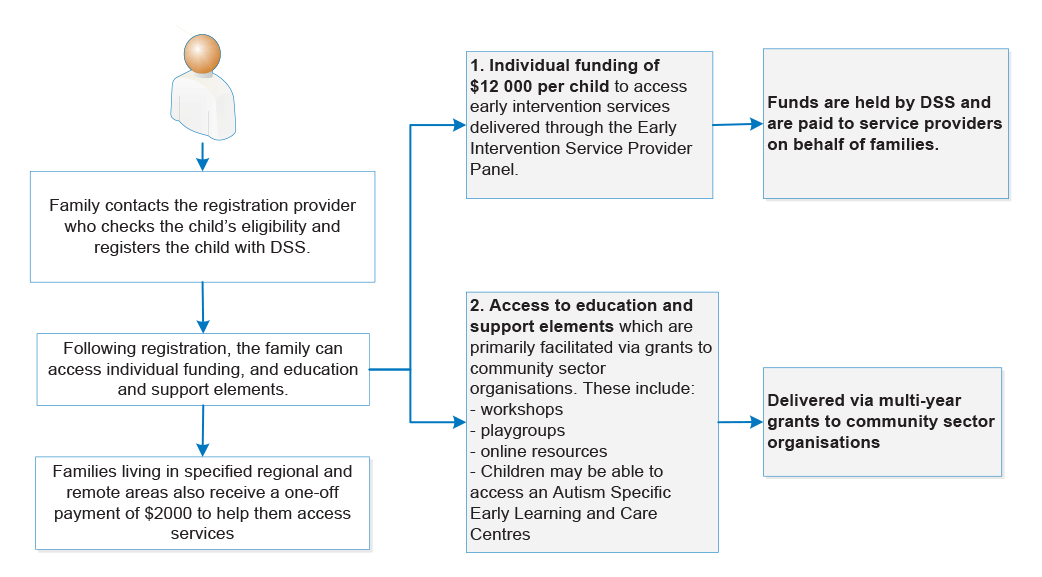

2.1 DSS contracts service provider organisations to deliver registration services to manage access to the EISCD, with other providers operating on a fee-for-service basis to deliver intervention services for eligible children and their families. The service delivery model is illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Service delivery model—individual funding supported by multi-year grants to community groups for the delivery of administrative and group services

Source: ANAO analysis of DSS documentation.

Has DSS developed appropriate registration mechanisms for eligible children and service providers?

To facilitate national registration for the program, DSS has contracted and funded a network of organisations with existing service infrastructure and reputation in the disability sector to manage the registration of children. DSS has also developed a process to register suitably professionally qualified and experienced service providers nationally, for the direct provision of services for EISCD children. These arrangements are effective in supporting the registration of eligible children and service providers.

Registration of eligible children

2.2 Program access and registration is managed by autism advisors for HCWA and the Registration and Information Service for Better Start. The registration service providers assess applications received, confirm a child’s eligibility,, register the child for funding through the FaHCSIA Online Funding Management System (FOFMS)15, and provide families with information about DSS registered service providers. The peak state and territory autism associations are contracted to deliver the autism advisor service, while Carers Australia delivers the Better Start registration service nationally through its network of offices.

2.3 Involvement of the peak state and territory autism associations in the program resulted from initial Australian Government funding to support their development, and subsequent contracting via direct sourcing16 of their services by DSS as autism advisors. In addition to their role as autism advisors, five of the seven autism associations also operate as EISCD registered fee-for-service providers, with three of the seven autism associations offering diagnostic services for autism.

2.4 In their role as autism advisors, the associations are required to provide contact details and information to families about service providers who can assist their child once registered. As at 30 June 2015, fee-for-service billings by four of the autism associations, who were also funded as autism advisors, were in the top ten HCWA billers and accounted for nine per cent of total HCWA billings nationally, with two accounting for almost 20 per cent of the billings within their state. Under this model, autism advisors are able to refer families directly to their own organisation to access fee-for-service interventions. One part of the DSS funding application required each of the autism associations to have protocols in place to ensure that advisory and support services are provided in an impartial manner. While this required organisations to manage the risk in the delivery of services, DSS did not implement mechanisms to assess or monitor this risk, nor directly advise the Minister of the risk of a potential conflict of interest.

Registration of service providers

2.5 Registration as a service provider is available to a range of allied health professionals and organisations, and is made subject to the provider meeting prescribed criteria. All allied health professionals are required to have appropriate professional qualifications and current membership of their relevant professional body. It is also desirable for practitioners to demonstrate experience and capability in working with families from Indigenous and culturally and linguistically diverse17 backgrounds, and/or families in rural, regional and remote areas.

2.6 Providers can apply to deliver services under either, or both components of the program. In July 2015, there were 2620 registered service providers for HCWA and 2368 for Better Start. Speech therapy was the most commonly accessed service and most expenditure on services occurred through the HCWA component of the program.

Guidance to service providers

2.7 The Early Intervention Service Provider Panel Operational Guidelines are publically available online and include details of service provider registration requirements and early intervention services that are authorised for payment under the fee-for-service funding agreement between DSS and each of the registered service providers. The guidelines emphasise the importance of early intervention services being delivered collaboratively through multidisciplinary and/or transdisciplinary teams, and require service providers, including sole practitioners, where appropriate and possible, to adopt these collaborative approaches as better practice in the delivery of early intervention services.

2.8 Some service providers interviewed by the ANAO reported working collaboratively with families and other providers. As DSS does not collect information on whether providers are working in this way, DSS is unable to readily determine whether service providers are routinely collaborating in the delivery of early intervention services for children with disabilities, as per the program guidelines.

2.9 DSS commissioned two evaluations which noted that the EISCD had largely been effective in reaching the target population, increased access to approved early intervention services, and produced positive outcomes for families. Nevertheless, the evaluations also raised concerns about the extent to which services were consistent with DSS published guidelines in relation to multidisciplinary and/or transdisciplinary approaches. In November 2015, DSS advised that it is continuing to explore options to recognise and compensate service providers for the time taken to collaborate with other providers and children’s families.

Does the EISCD model support access to, and the utilisation of, early intervention services nationally?

ANAO analysis of claims data indicates that access to services remains reliant on the proximity to DSS registered service providers, with the number of claims for each child declining for children living in areas defined as regional and remote.

2.10 The EISCD is a national program which is available to children under the age of seven with an eligible diagnosis. EISCD services are delivered throughout Australia by 2620 registered service providers for HCWA and 2368 registered service providers for Better Start. An allocation of $12 000 is provided to each eligible child to purchase interventions and resources through any registered service provider. Families eligible for the additional $2000 Outer Regional, Remote and Access Support Payment receive this payment directly.

2.11 DSS collects data on service claims funded directly through the program, as well as where registered children reside. Analysis of this data indicates a concentration of DSS funded service access and use by families living in major cities. This is reflective of population density and the availability of disability-related services. Consistent with the distribution of the Australian population, service access is highest in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland.

2.12 The ANAO analysed a sample of 45 321 EISCD children’s records and service claims made between February 2008 to January 2015. The 1.7 million service claims extracted from the supporting information technology system were matched against the Australian Bureau of Statistics Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA). This analysis indicated that the majority of EISCD families lived in major cities (31 781) with the number declining in areas defined as inner regional (9122), outer regional (3836), remote (427) and very remote (155). The data indicated that the distribution of registered EISCD children is broadly proportional to the distribution of the Australian population.

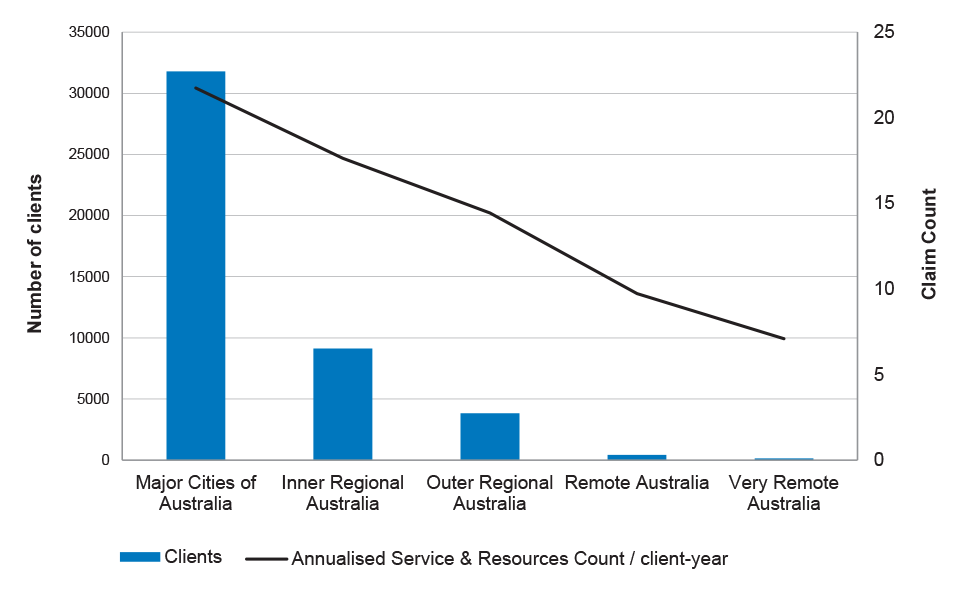

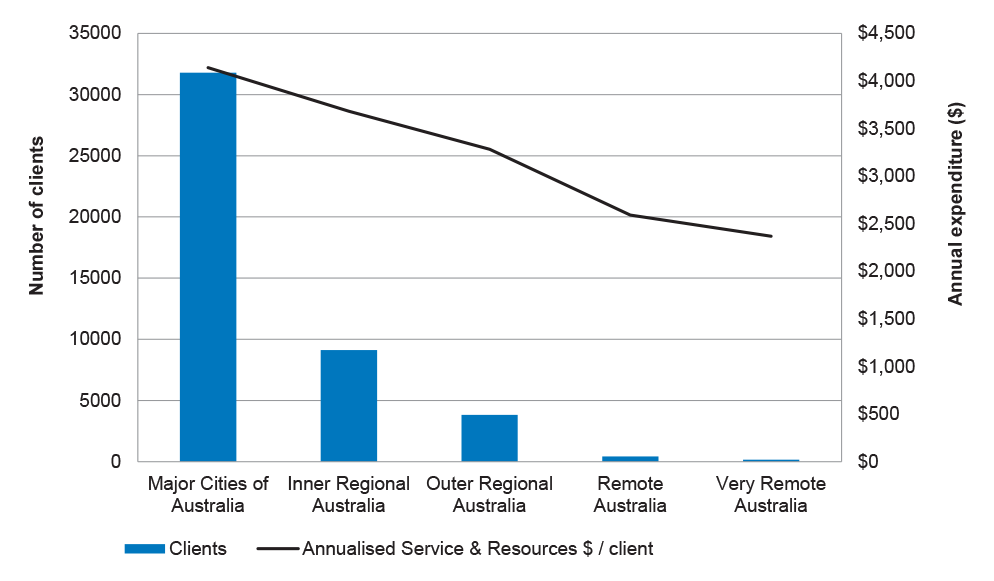

2.13 Analysis of the data also indicated that EISCD clients who live in major cities made, on average, 22 claims each year, with the number of claims per year declining as remoteness increased, with an average of seven claims each year for children living in very remote areas. This trend in service utilisation is reflected in Figure 2.2. Similarly, the annualised expenditure progressively declines for children living outside major cities, as shown in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.2: Annualised number of service and resource claims by location (remoteness)

Source: ANAO analysis of DSS data from February 2008 to January 2015.

Figure 2.3: Annualised expenditure on service and resource claims by location (remoteness)

Source: ANAO analysis of DSS data from February 2008 to January 2015.

2.14 A DSS-funded report completed in 201418 made similar findings, noting that children with a disability living in rural areas are up to 23 per cent less likely to register with HCWA and Better Start, and that those who are registered are less likely to access services and support.19 In part, this can be attributed to the limited number of allied health professionals operating in regional areas. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported that in 2006 there were 354 allied health workers per 100 000 population in major cities reducing to 64 allied health professionals per 100 000 population in very remote areas.20 Service providers interviewed by the ANAO commented that families living in areas where local services are limited may purchase resource items with their funding, but access few or no early intervention services.

Outer Regional, Remote and Access Support Payment

2.15 The Outer Regional, Remote and Access Support Payment—a one-off payment of $2000 is made to families living in designated areas to support travel and accommodation from their home location to access DSS registered service providers. Eligibility for this payment is assessed by DSS using the family’s home address matched against the ABS ARIA measure. Requests for payments may be considered by DSS for children not located in outer regional and remote locations under ‘exceptional circumstances’.21 Payment of the $2000 is transferred directly to families’ bank account on registration. No acquittal requirements apply.

2.16 DSS has allocated almost $16.3 million in Outer Regional, Remote and Access Support Payments between 2008 and 2015. DSS also funded a $495 000 project from 2012–13 to 2014–15 to increase service coverage in rural and remote locations by offering support to existing and potential service providers. Despite measures to increase access, use of services remains largely reliant on proximity to service providers, with the number of claims per child declining for children living in areas defined by the ABS as regional and remote.

Service access across socio-economic indicators

2.17 Utilisation data indicates that overall, use of services is variable when compared to measures of socio-economic disadvantage. Analysis of service access relative to the ABS ARIA measure and the Social and Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA)22 indicates that in urban areas, where services are readily available, program access is highest by families experiencing lower levels of socio-economic disadvantage. Conversely, program access is highest for people living in all other areas, where the level of socio-economic disadvantage is greater. Table 2.1 presents information about EISCD service access by location and level of socio-economic disadvantage.

Table 2.1: EISCD service access by SEIFA and ARIA locations

|

Level of disadvantage |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

Total |

|

|

Most disadvantaged |

|

Least disadvantaged |

|

|||||||

|

Remoteness |

|||||||||||

|

Major cities of Australia

|

3220 |

1582 |

2201 |

2850 |

2659 |

4066 |

4065 |

4583 |

5302 |

4660 |

35 188 |

|

9.1% |

4.4% |

6.25% |

8% |

7.5% |

11.5% |

11.5% |

13.% |

15.0% |

13.2% |

65% |

|

|

Inner-regional Australia

|

650 |

1977 |

1309 |

1844 |

1712 |

1101 |

880 |

679 |

529 |

194 |

10 875 |

|

5.9% |

18% |

12% |

16.9% |

15% |

10% |

8% |

6.2% |

4.8% |

1.7% |

20% |

|

|

Outer-regional Australia

|

677 |

1278 |

873 |

1594 |

649 |

472 |

857 |

280 |

286 |

- |

6 966 |

|

9.7% |

18% |

12.5% |

22.8% |

9.3% |

6.7% |

12.3% |

4% |

4% |

- |

12.8% |

|

|

Remote Australia

|

65 |

104 |

106 |

67 |

126 |

135 |

47 |

8 |

70 |

44 |

772 |

|

8.4% |

13.4% |

13.7% |

8.6% |

16% |

17.4% |

6% |

1% |

9% |

5.6% |

1.4% |

|

|

Very remote Australia

|

62 |

24 |

33 |

16 |

23 |

30 |

22 |

- |

6 |

21 |

237 |

|

26% |

10.1% |

13.9% |

6.75% |

9.7% |

12.6% |

9.2% |

- |

2.5% |

8.8% |

.43% |

|

|

Total1 |

4674 |

4965 |

4522 |

6371 |

5169 |

5804 |

5871 |

5550 |

6193 |

4919 |

54 038 |

|

Per cent of total |

8.65 |

9.19 |

8.37 |

11.79 |

9.57 |

10.74 |

10.86 |

10.27 |

11.46 |

9.10 |

100 |

Note 1: Total refers to number of clients over the life of the EISCD. Percentages are rounded.

Source: DSS data as at 1 December 2014.

Recommendation No.1

2.18 To better understand the barriers to accessing services funded through the EISCD and to improve access to services for children living outside of urban areas, the ANAO recommends that DSS consult with service providers and EISCD families about access issues and provides advice to the responsible Minister about how to improve access to services.

Department of Social Services response:

2.19 DSS agrees with this recommendation. DSS notes that the programmes will transition completely into the NDIS with full scheme phasing commencing July 2016. The NDIA is building capacity and will work directly with communities to overcome the challenges of delivering services in rural and remote Australia. In the lead-up to full scheme, DSS will consult with service providers and brief the Minister as appropriate. We will use consultation mechanisms already in place, including a helpdesk for service providers, and NDIS transition seminars currently in planning, which will include consultation about access issues. We will continue to implement strategies to improve access, including the Access Payment and the Indigenous Liaison Officers project.

3. EISCD entry requirements, forecasting of demand, utilisation and expenditure

Areas examined

The ANAO examined arrangements implemented by DSS to: define entry requirements; forecast demand for services; assess whether utilisation and expenditure is consistent with program forecasts; and provide estimates of the number of eligible children to transition to the NDIS.

Conclusion

- Critical to the ongoing financial sustainability of a demand-driven program is DSS’ capacity to manage entry requirements. A combination of administrative and diagnostic requirements determines program access. The administrative requirements have been clearly defined, but the HCWA diagnostic eligibility requirements have varied over time, increasing the demand for services under the program.

- DSS has not accurately forecast demand for services funded through the two components of the program. Between 2008–09 and 2014–15, DSS underestimated HCWA registrations by almost 14 000 children. Since the commencement of Better Start in 2010–11 to 2014–15, DSS overestimated Better Start registration by approximately 1200 children.

- HCWA utilisation annually exceeded forecasts to 2013–14, resulting in annual budget overruns of between $1.5 million and $18 million. Better Start has generally recorded less than forecast utilisation with annual under-expenditure of between $3.9 million and $19.3 million.

- DSS has underestimated the number of children expected to transition from the EISCD to the NDIS. Net growth in the EISCD has also been higher than expected, having a flow on effect for the NDIS.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at the Department improving the forecasting of demand for the EISCD and better managing EISCD expenditure.

Are entry requirements clearly defined and applied?

Entry to each component of the EISCD is determined by administrative and diagnostic entry requirements. The administrative requirements are clearly defined, but the HCWA diagnostic entry requirements have varied over time, broadening the eligibility criteria for the program, and increasing demand for services.

3.1 A combination of administrative and diagnostic requirements determines program access. Children must be under the age of six years at the time of registration with eligibility ceasing when the child turns seven; and both the parent/carer and the child must be living in Australia permanently:

- as an Australian citizen;

- be the holder of a permanent resident visa; or

- be a New Zealand citizen who was:

- in Australia on 26 February 2001, for 12 months in the two years immediately before that date, or

- assessed as ‘protected’ before 26 February 2004.

3.2 Children must also be diagnosed with an eligible disability. While both components of the program rely on a professional diagnosis, there are some differences regarding the assessment of eligibility between components. These relate to how the diagnosis is made, who can make the diagnosis, whether the degree of impairment resulting from the disability determines eligibility, and whether a level of disability threshold applies.

HCWA diagnostic requirements

3.3 A diagnosis of autism is based on observed behaviours. There are no blood tests, no single defining symptom, and no physical characteristics that are unique to autism. Accordingly, clinicians must use careful observation to determine whether a child’s behaviours result from autism, or are better described by another disability. HCWA guidelines define an eligible diagnosis of autism as including one of the following: Autism; Autism Spectrum Disorder; Autistic Disorder; Asperger’s Disorder/Syndrome; Childhood Disintegrative Disorder; or Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified. HCWA guidelines, effective from February 2014, note that having ‘similar characteristics’ to autism is not an eligible diagnosis.

3.4 To support registration, autism advisors must sight a written, conclusive diagnosis of autism made in Australia by, or through, one of the following:

- state/territory government or equivalent multidisciplinary assessment service;

- private multidisciplinary team23;

- paediatrician; or

- psychiatrist.

Within the diagnosis of autism for HCWA eligibility, no threshold or severity of the disability applies.

3.5 There has been variability in the description of the diagnostic requirements for HCWA eligibility over time. At the commencement of the program a diagnosis of autism consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders version four (DSM-IV) was used as the basis for determining eligibility for HCWA. The DSM is produced by the American Psychiatric Association and is used by mental health professionals internationally. It provides a common language for the definition of mental health conditions by listing the signs and symptoms of each condition and stating how many of these must be present to confirm a diagnosis. This assists independent professionals to reach consistent diagnostic conclusions and to provide similar interventions.

3.6 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders version five (DSM-5), was released in May 2013. It refined the diagnosis of autism under the term Autism Spectrum Disorder. Following the release of the DSM-5, DSS advised the Minister that the changes to the DSM diagnostic criteria for autism may result in an estimated 10 to 20 per cent of children, who may have previously been eligible, based on a diagnosis of autism under the DSM-IV, possibly missing out on support. Accordingly, an interim policy was recommended to the Minister, which based eligibility on a professional diagnosis using either the DSM-IV, or the DSM-5, or a diagnosis of autism described by DSS as, commonly used by health professionals. It was also recommended that this interim policy remain in place until the full implementation of the NDIS in July 2019—a period of almost six years. The Government accepted these recommendations.

3.7 A DSS Fact Sheet prepared at the time to communicate the revised HCWA eligibility requirements references the need for a professional diagnosis only. While the Fact Sheet notes that diagnostic eligibility for HCWA was previously based on the DSM-IV, no other reference to either version of the DSM is made, nor to any criteria for the diagnosis of autism. In May 2015, DSS advised the ANAO that there is no requirement for a diagnosis to be consistent with either the DSM-IV or DSM-5 or other manuals such as the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, as long as the diagnosis of autism is made.

3.8 Eligibility for the Autism Specific Early Learning and Care Centres (ASELCCs)24, an additional commitment to the HCWA package, also demonstrates some inconsistency with the HCWA package. The centres were established in areas with a high incidence of autism25 and provide programs and support for children with autism to enable their participation in child care and early childhood education. Eligibility to attend an ASELCC does not require a diagnosis of autism, nor does it require a child to be registered with HCWA. Children diagnosed with ‘autism-like symptoms’ are able to attend.

3.9 Variability in eligibility requirements was also identified in the DSS commissioned report Patterns of expenditure and service use: An analysis of Helping Children with Autism and Better Start data, commissioned by the Department and published in June 2013. The report prepared by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare described the ‘primary disability’ field, which determined program eligibility, in each of the HCWA and Better Start data sets, as poorly recorded.26

3.10 Overall, the HCWA eligibility requirements demonstrate some variability. As autism co-varies27 at very high rates with other disabilities, including intellectual disability, HCWA eligibility requirements may leave room for the inclusion of children whose disability may be better described by another disability and supported by other interventions.

Better Start diagnostic requirements

3.11 Of the 16 eligible Better Start disabilities, 11 are rarely occurring genetic disorders defined by chromosomal variations identifiable through clinical testing. The remaining five conditions are assessed using various sensory or physical assessment instruments, for example, limitations in hearing or vision. Of these five conditions, disability thresholds apply to four, with thresholds clearly specified.

3.12 Only one of the 16 disabling conditions, cerebral palsy, an umbrella term which refers to a group of disorders affecting a person’s ability to move28, has no disability threshold applied. Children diagnosed with cerebral palsy may be affected in different ways and to varying degrees. For a description of eligible Better Start disabilities and the thresholds which apply see Appendix 3.

3.13 To accommodate the diversity of disabling conditions included under the Better Start initiative, a written conclusive diagnosis including assessment within the prescribed threshold, is required from one of the following in Australia:

- paediatrician;

- relevant medical specialist, such as a geneticist, neurologist, ophthalmologist, otologist, or ear, nose and throat specialist;

- general practitioner;

- multidisciplinary assessment service; or

- Australian Hearing.29

3.14 The Better Start diagnostic requirements are clearly specified with defined disability thresholds applied.

Was DSS’ forecasting of EISCD demand and expenditure robust?

DSS’ forecasting of demand for and related expenditure under the program has been poor. HCWA utilisation has annually exceeded forecasts to 2013–14, with over-expenditure of the HCWA budget allocation of between $1.5 and $18 million annually. Better Start has generally recorded less than forecast utilisation with annual under-expenditure of between $3.9 million and $19.3 million.

3.15 Critical to the ongoing financial sustainability of a demand-driven program, is the capacity to forecast utilisation. Concurrently, careful monitoring of utilisation against forecasts is required particularly where funding is allocated relative to forecast use and expenditure. Eligibility has a causal relationship with utilisation, and as costs associated with individual funding packages account for approximately 80 per cent of all EISCD expenditure, any over, or under-estimating of utilisation, will likely result in proportionate under, or over-expenditure of the funding allocation.

3.16 The availability of prevalence30 and incidence31 data to assist in forecasting utilisation for each of the eligible EISCD disabilities varies, as can the reliability of that data. This variability influences the reliability of DSS’ forecasting of service utilisation and associated expenditure.

HCWA forecasting and utilisation

3.17 From the commencement of HCWA in 2008 to 2013–14, service utilisation and expenditure has annually exceeded projections. Although less than forecast utilisation was recorded in 2014–15, expenditure remained above forecast. Forecast and actual utilisation and associated expenditure are detailed in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: HCWA forecast and actual utilisation and expenditure

|

Year |

Children |

Expenditure $ million |

||||

|

|

Forecast |

Actual |

Difference |

Forecast |

Actual |

Difference |

|

2008–09 |

3 540 |

4 344 |

804 |

13.3 |

16.3 |

3.0 |

|

2009–10 |

7 010 |

9 943 |

2 933 |

34.1 |

48.4 |

14.3 |

|

2010–11 |

10 100 |

14 772 |

4 672 |

38.9 |

56.9 |

18.0 |

|

2011–12 |

14 750 |

17 655 |

2 905 |

55.9 |

66.9 |

11.0 |

|

2012–13 |

19 024 |

20 414 |

1 390 |

70.5 |

74.0 |

3.5 |

|

2013–14 |

21 845 |

22 997 |

1 152 |

69.9 |

79.4 |

9.5 |

|

2014–15 |

22 463 |

22 415 |

(48) |

63.8 |

65.3 |

1.5 |

Source: DSS documentation.

3.18 The original HCWA model, as announced in 2007, was based on grant funded organisations providing group services for the majority of eligible children where the diagnosis was categorised as mild to moderate (estimated to be approximately 12 000 children), with a smaller number of individual funding packages reserved for children where the disability was diagnosed as severe (estimated to be approximately 5200 children). Total funding allocations were based on this model, as was the financial allocation for the individual funding package. In November 2007, in response to stakeholder feedback, the program design was amended. The redesigned program, as implemented, directed financial support from grant funded group services to individual funding packages. In addition, individual funding packages were made available to all children with an eligible diagnosis, not only to those children where the diagnosis was recorded as severe. No revisions to forecast utilisation or expenditure were made to reflect the program changes.

3.19 Initial forecasting for the program was not soundly based. There was a lack of consistency between national data sets on the prevalence and incidence of autism in Australia. DSS’32 baseline forecasts for eligibility were estimated using the number of children whose families/carers were in receipt of the Carer Allowance (Child)33 and, where the family had nominated autism as the eligible disability to claim the payment.

3.20 The original forecasts were limited by an inconsistency between the eligibility guidelines for HCWA and the eligibility guidelines for the Carer Allowance (Child). The data set used understated the potential number of eligible children as it did not include children diagnosed with Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS),34 as this diagnosis was not eligible for payment of the Carer Allowance (Child). Of the children receiving HCWA benefits between July 2010 and June 2012, approximately 17 per cent were reported as having a diagnosis of PDD-NOS.35

3.21 DSS subsequently extended HCWA eligibility to a broader group of children, providing access to all eligible children from birth to six years, rather than as originally proposed to children in the two years prior to formal schooling. Eligibility was further expanded in February 2009 with children able to retain entitlements to seven years of age. These changed eligibility requirements reduced the reliability of the forecasting model as the underlying assumptions on which the model was based were not adjusted to reflect the expected increase in demand for services.

3.22 DSS has taken sporadic action to improve HCWA forecasting. In 2009, each of the six peak autism associations received one-off funding ($56 250 each) to develop a national autism register, to improve the statistical evidence base, and to inform policy development and improvements to service delivery. Additional funds were also allocated for a feasibility study and pilot to progress the development of the register. Following expenditure of approximately $600 000, DSS discontinued work on the register in 2011 with funds reallocated to support the HCWA Indigenous Liaison Officers (later known as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Liaison Officers).

3.23 DSS also engaged external consultants in 2013 at a cost of $40 000 to improve the HCWA budget model. The work completed did not address the relationship between entry requirements and utilisation. In February 2014, DSS allocated $50 000 to investigate autism diagnostic practices in Australia, with the aim of establishing the extent of over-diagnosis nationally. The Department advised Government that this would assist with developing a more consistent standard of autism diagnosis which may lead to a reduction of expenditure for HCWA with fewer new children becoming eligible. The research was incomplete in February 2016.

3.24 HCWA utilisation indicates that the diagnosis of autism in Australia has increased. Recent research36 suggests factors such as the widening of the diagnostic criteria and improved awareness and diagnostic sensitivity is leading to this increase. Additionally, the DSS-commissioned Evaluation of the Helping Children with Autism Package (2012)37 noted that the package had created pressure to diagnose autism, with about three quarters of all diagnosticians surveyed reporting feeling pressured to provide an autism diagnosis, and that the nature of disabilities being diagnosed as autism may be widening because of the availability of funding for support services.

Better Start forecasting and utilisation

3.25 From the commencement of Better Start in 2010–2011 through to 2013–14, DSS overestimated utilisation and expenditure. Utilisation exceeded forecasts in 2014–15 although expenditure for the same period was $6.9 million less than forecast. Better Start forecast and actual utilisation and expenditure are detailed in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: Better Start forecast and actual utilisation and expenditure

|

Year |

Children |

Cost $ million |

||||

|

|

Forecast |

Actual |

Difference |

Forecast |

Actual |

Difference |

|

2010–11 |

|

|

|

1.1 |

1.1 |

0 |

|

2011–12 |

6 000 |

4 490 |

(1 510) |

35.7 |

16.4 |

(19.3) |

|

2012–13 |

7 070 |

6 865 |

(205) |

25.0 |

21.1 |

(3.9) |

|

2013–14 |

7 957 |

7 888 |

(69) |

27.8 |

20.4 |

(7.4) |

|

2014–15 |

7 412 |

7 954 |

542 |

21.8 |

14.9 |

(6.8) |

|

2015–16 |

Not available |

- |

- |

Not available |

- |

- |

Source: DSS documentation.

3.26 The initial Better Start forecasts were based on the reported incidence of eligible conditions. This was indexed using ABS population growth figures of 1.4 per cent per annum as estimated for the year ending March 2011.38 DSS subsequently increased the 2011–12 Better Start estimate to a first year forecast of 6000 eligible children at a cost of $35.7 million in anticipation of possible utilisation rates similar to HCWA. This resulted in a first year underspend of $19.3 million. In 2013–14, an additional nine disabilities were added as eligible Better Start disabilities with a corresponding increase in projected utilisation.

3.27 For the period 2015–16 to 2018–19 DSS had requested the provision of approximately $25 million per year to support the operation of Better Start. Based on historical utilisation this estimate exceeds funding requirements by approximately $9 million per year. In February 2016, DSS advised the ANAO that over the forward years, program expenditure is expected to be in the order of $16.3 million.

Has program uptake and associated expenditure been consistent with DSS’ program forecasts?

DSS’ has not accurately forecast demand for the two components of the EISCD. Uptake of the HCWA component of the program has exceeded forecasts with expenditure also being higher than expected. Forecast utilisation and expenditure in relation to Better Start has been overestimated, and on two occasions DSS has redistributed funds between the two program components to compensate.

Increases in utilisation and expenditure inconsistent with forecasts

3.28 During 2014–15 there were 30 369 children registered to receive EISCD assistance—22 415 children under HCWA, and 7954 children under Better Start, as shown in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3: EISCD clients 2008–09 to 2014–151

|

Year |

HCWA |

Change in the number of eligible children |

Better Start |

Change in the number of eligible children |

Totala |

|

2008–09 |

4 344 |

- |

N/A |

- |

4 344 |

|

2009–10 |

9 943 |

128 % |

N/A |

- |

9 943 |

|

2010–11 |

14 772 |

49 % |

N/A |

- |

14 772 |

|

2011–12 |

17 655 |

20 % |

4 490 |

- |

22 145 |

|

2012–13 |

20 414 |

16 % |

6 865 |

53 % |

27 279 |

|

2013–142 |

22 997 |

13 % |

7 888 |

15 % |

30 885 |

|

2014–15 |

22 415 |

(2.5) % |

7 954 |

1 % |

30 369 |

Note 1: These figures refer to children that were active during that financial year.

Note 2: It could be expected that in 2013–14 and 2014–15 there would be a reduction in numbers due to the movement of children from the EISCD to the NDIS and/or entering the NDIS directly in trial sites nationally.

Source: DSS data.

3.29 The number of children registered and accessing services has increased considerably from the commencement of HCWA in 2008 when it was expected that the program would assist, in total, around 15 000 families of children up to six years of age, between July 2008 and June 2012. Subsequent changes to eligibility requirements resulted in a total of approximately 15 000 children accessing services between 2008 to June 2010, and by June 2012, a total of 26 35039 children had registered under HCWA, with 20 026 children lodging one or more claims for services or resources. The demand for Better Start, although less than forecast, saw numbers almost doubling between 2011–12 and 2013–14. At a program level, between 2008–09 and 2013–14, EISCD recorded annual percentage increases of between 13 and 128 per cent, substantially higher than the general population growth rate of between 1.5 and 1.8 per cent. This has generated commensurate increases in annual program expenditure from $6.5 million to $80 million.

3.30 Program expenditure has not been well-managed by DSS. The Australian Government committed $436 million for the delivery of HCWA from 2008–09 to 30 June 2016. Of these funds, $407 million or approximately 93 per cent of allocated funding had been spent by 30 June 2015. DSS has forecast HCWA expenditure of over $78.6 million in 2015–16, which would bring total expenditure to $485.6 million. This is $49.6 million in excess of the Government’s initial allocation. At the same time there has been a continuing under-expenditure of the Better Start allocation. Of the $172 million made available to fund services to June 2016, $73.9 million had been spent by June 2015 with DSS anticipating a further spend of $25.2 million in 2015–16.

3.31 No program utilisation targets were included in DSS’ Portfolio Budget Statement 2015–16 for the period 2016–17 to 2018–19. Based on the net annual expenditure trends to date, a significant reduction in net entry to the EISCD will be required if the program is to remain within the funding allocated from 2015–16 onwards. To June 2014, DSS has reported increases of between 3000 and 5000 EISCD eligible children each year followed by a reduction of approximately 500 children in the 12 months to July 2015. Between July 2013 and August 2015, 2650 children transitioned from the EISCD to the NDIS, suggesting that the number of new EISCD entrants may exceed the number of children transitioning from the EISCD to the NDIS.

3.32 At the commencement of each NDIS trial, for all EISCD children living in that site, DSS transfers EISCD funds to the NDIA—a one off payment of $3000 per child. Consequently, between 2015–16 and 2018–19, DSS will be required to transfer approximately $91 million from the existing program allocation to the NDIA to meet this commitment. DSS will need to periodically monitor program expenditure to determine whether sufficient program funding will be available to meet this commitment.

Redistribution of funds between the two program components

3.33 To compensate for the over-expenditure of the HCWA allocation, DSS has redistributed funds from Better Start on two occasions. In April 2013 DSS recommended the Minister transfer $4.6 million from Better Start to HCWA to offset HCWA expenditure for 2012–13, indicating that work completed by the external consultant to improve HCWA forecasting would result in more accurate estimates of HCWA utilisation and expenditure in the forward years. The revised estimates for 2012–13 and 2013–14, provided to support the transfer of funds from Better Start, underestimated expenditure for those years by approximately $10 million annually. In 2013–14, DSS again sought Ministerial approval to transfer funds from Better Start to HCWA—$4.15 million was transferred. Transfer of funds from Better Start has enabled service delivery to continue under HCWA and DSS has periodically advised Government of the pattern of expenditure under the program, but has not otherwise provided options to better manage program utilisation and expenditure.

Has the number of children transitioning to the NDIS been accurately identified?

DSS has, over time, underestimated overall EISCD demand. With the introduction of the NDIS, net growth in the EISCD has been higher than expected having a flow on effect for the NDIS as children transition to the scheme. The unanticipated EISCD demand and the higher than expected cost of NDIS individualised funding packages has created a risk that DSS and the NDIA may need to approach the Australian Government, in future periods, for additional funding.

3.34 Following the introduction of the NDIS in trial sites nationally, eligible children are gradually transferring from the EISCD to access benefits through the scheme. The EISCD will continue to operate in areas where the NDIS is still to be implemented, with national implementation scheduled for July 2019.

3.35 Under the EISCD all eligible children receive a $12 000 individual funding package. As children transition to the NDIS the nature and range of entitlements available changes based on an assessment of need. In consultation with children’s families, required services and support are identified and associated costs are estimated to generate an individualised service plan. On acceptance of the NDIS plan by the family, access to both EISCD and state and territory services ceases.

3.36 The transition of existing Government programs to the NDIS is guided by the Intergovernmental Agreement on the National Disability Insurance Scheme Launch.40 This agreement provides that clients in receipt of existing Government services transition to the NDIS on a ‘no disadvantage’41 basis while those assessed as ineligible have a ‘continuity of service’42 guarantee. Service and registration providers consulted during the audit indicated that EISCD children who applied to the NDIS, had been assessed as eligible for individualised packages, or funding support, although the total value of the packages was often unknown.

3.37 The Parliamentary Joint Standing Committee on the National Disability Insurance Scheme’s Progress report on the implementation and administration of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (July 2014), observed that the annual package cost for children under the NDIS generally range from $6000 to $16 000 with the cost of ‘therapeutic supports for children under the age of six’, generally falling into one of three categories:

- Level 1 defined as low needs—$6000 to $8000 per annum;

- Level 2 defined as medium needs—$8001 to $12 000 per annum; and

- Level 3 defined as high needs—$12 001 to $16 000 per annum.

3.38 The Committee also reported that ‘a significant proportion of children eligible for the NDIS in the South Australian trial site have received financial support packages greater than $16 000 per annum’.43 Service providers interviewed by the ANAO made similar observations and noted that the value of packages was higher for children diagnosed with multiple disabilities and complex needs. DSS transfers one-off funding of approximately $3000 per child44 for all children living in a trial site at the commencement of the trial. This is a significantly lower amount than the costs incurred under the NDIS. The potential impact on the NDIS is further amplified by the growth in the number of children registering for services under the EISCD, with demand for the program being far greater than forecast by the Department. New registrations have exceeded forecasts by approximately 14 000. In the longer term these children will transition to the NDIS.

EISCD forecasts to 2018–19

3.39 DSS has forecast total EISCD expenditure of approximately $104 million from 2015–16 increasing to approximately $110 million by 2018–19 as illustrated in Table 3.4. Within these forecasts, DSS expects HCWA expenditure to continue to increase before plateauing between 2017–18 and 2018–19, the final years of the program, prior to the full transition of the NDIS. Over this period, DSS has estimated that Better Start expenditure will remain relatively constant.

Table 3.4: DSS forecasts 2015–16 to 2018–19

|

EISCD |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

|

|

$ million |

$ million |

$ million |

$ million |

|

HCWA |

78.6 |

82.0 |

83.9 |

83.8 |

|

Better Start |

25.2 |

25.8 |

25.8 |

25.8 |

|

Total |

103.8 |

107.8 |

109.8 |

109.6 |

Note 1: DSS advised in February 2016 that the Better Start allocation for 2016–17, 2017–18, and 2018–19 may be varied with a reduction in the annual allocation from $25.8 million to $16.3 million in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook adjustments. These figures have been rounded.

Source: Advice from DSS.

3.40 Based on the forecast expenditure in Table 3.4, and noting that DSS has been unable to provide the forecast utilisation data on which these estimates are based, the forecast expenditure patterns suggest that DSS anticipates a small increase in the demand for HCWA between 2015–16 and 2017–18, with demand for Better Start remaining largely constant.

3.41 The NDIS trials commenced in July 2013 and the scheme will be implemented nationally from July 2016 to July 2019. As a result it could be anticipated that EISCD registrations will progressively decline due to:

- no new children entering the EISCD in NDIS trial sites;

- increasing numbers of children exiting the EISCD and transitioning to the NDIS; and

- children exiting the EISCD via natural attrition (reaching the age of seven years and/or expending their full entitlements).

Alternatively, DSS forecasts indicate that EISCD registrations are increasing, but are masked by the impact of the implementation of the NDIS. There would be benefit in the Department reviewing the impact of the rollout of the NDIS on the future demand for EISCD services.

Impact of the NDIS on EISCD demand

3.42 Between July 2013 and August 2015, DSS advised that around 2650 children transitioned from the EISCD to the NDIS in three of the four trial sites operational from July 2013.45 At the same time approximately 415 families were working with the NDIA to develop a personal plan for their children. An additional three trial sites commenced in July 2014, with another three sites commencing in July 2015. DSS advised that following the commencement of each NDIS trial site, no new EISCD registrations had been accepted for children living in these sites, and that services must now be accessed through the NDIS.

3.43 The progressive implementation of the NDIS will incrementally reduce EISCD demand as increasing numbers of EISCD children transition to the NDIS. Additionally, as the number of sites increase there will be a corresponding decrease in new EISCD entrants as children access the NDIS directly. The subsequent reduction in the number of eligible children is likely to accelerate as the NDIS is implemented nationally from July 2016. Bilateral agreements between the Australian, state and territory governments will determine how entry to the NDIS will be managed, but it is likely that infants and young children will be prioritised.

Recommendation No.2

3.44 To assist the Australian Government in the development of policy frameworks and to make informed decisions regarding the future delivery of the EISCD within financial allocations, the ANAO recommends that DSS provide a comprehensive analysis of EISCD forecast utilisation and expenditure to Government.

Department of Social Services response:

3.45 DSS agrees with this recommendation and will provide a comprehensive analysis of EISCD forecast utilisation and expenditure to Government.

4. Transition to the NDIS

Areas examined

The EISCD is one of several Australian Government programs which will transition to the NDIS over time. The ANAO examined how DSS managed the transition of children to the NDIS in trial sites.

Conclusion

- Introduction of the NDIS increased the need to support parents, carers and early childhood professionals to understand when and how children were to transition to the NDIS. DSS’ approach to transitioning children from the EISCD to the NDIS demonstrated limited strategic planning and coordination.

- The need to assist families with information and support should have been identified in planning for the transition of children from the EISCD to the NDIS.

- Advice to families about choosing when to transition to the NDIS encouraged families to retain EISCD entitlements to maximise expenditure prior to transitioning.

- The initial advice to families about transitioning to the NDIS was subsequently retracted due to funding constraints, with revised arrangements being put in place.

- DSS could have made greater use of the registration service providers to assist families to transition to the NDIS. Some 13 months after the NDIS trial commenced, contracts with the registration service providers were amended to include direct assistance to families transitioning to the NDIS.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that DSS work with registration service providers and key stakeholders to develop clear, timely, and consistent advice for families, in order to assist them with the transition to the NDIS.

Implementation of the NDIS

4.1 The trial of the NDIS has been negotiated bilaterally between each state and territory and the Australian Government with each trial site reflecting local needs and priorities. For example, in the Australian Capital Territory, access to the NDIS has been prioritised on an ‘ages and stages approach’46, while in Tasmania the focus has been on young people aged 15 to 24 years.

4.2 Children eligible to receive support under the EISCD have transitioned to the NDIS in six of the seven national trial sites. This includes three of the four initial trial sites commencing in July 2013 and subsequent trial sites commencing in July 2014 as set out in Table 4.1. In Tasmania the NDIS trial has focused on young people aged from 15 to 24 years only. Transition of children from the EISCD to the NDIS commenced from July 2015 for children living in the Nepean/Blue Mountains and Queensland sites.

Table 4.1: NDIS trial site locations

|

NDIS trial site location |

Eligible age groups |

|

From July 2013 |

|

|

Tasmania |

Young people aged 15 to 24 years. |

|

South Australia |

Children and young people under 14 years. |

|

Victoria: Barwon region |

People up to age 65 years. |

|

New South Wales: Hunter region |

People up to age 65 years. |

|

From July 2014 |

|

|

Australian Capital Territory |

People up to age 65 years. |

|

Northern Territory: Barkley region |

People up to age 65 years. |

|

Western Australia: Perth Hills area |

People up to age 65 years. |

|

From July 2015 |

|

|

New South Wales: Nepean/Blue Mountains |

Children and young people under 18 years. |

|

From January 2016 |

|

|

Queensland: Townsville, Charters Towers and Palm Island |

Children and young people under 18 years in Townsville and Charters Towers and people up to age 65 in Palm Island. |

Source: Information available from the NDIS website: <http://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/our-sites>.

Did DSS provide clear and timely advice to families about the process for transitioning to the NDIS?

In July 2013 DSS offered EISCD families in NDIS trial sites choice in determining when to transition to the NDIS. Some families took up the option to delay their transition and increased their annual expenditure to maximise EISCD benefits prior to transitioning. After advising families they could retain their EISCD entitlements, DSS retracted their initial advice and placed a time limit on families transitioning.

4.3 In the initial phase of the NDIS trial from July 2013, DSS published information on its website to inform families living in the NDIS trial sites that their options were to either: