Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Digital Reform of the Agricultural Export Systems

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Consistent and reliable access to foreign markets is essential to the Australian agriculture industry, which exports approximately 72 per cent of the total value of production. Effective administration of the digital reform of agricultural export systems is intended to minimise disruption to exports and provide exporters with the benefits of faster, more reliable and cost-effective export services.

- This audit examined whether the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (the department) is effectively administering the digital reform of agricultural export systems.

Key facts

- The Australian Government has committed $349.6 million over six years (2020–21 to 2025–26) for the Digital Services to Take Farmers to Markets measure.

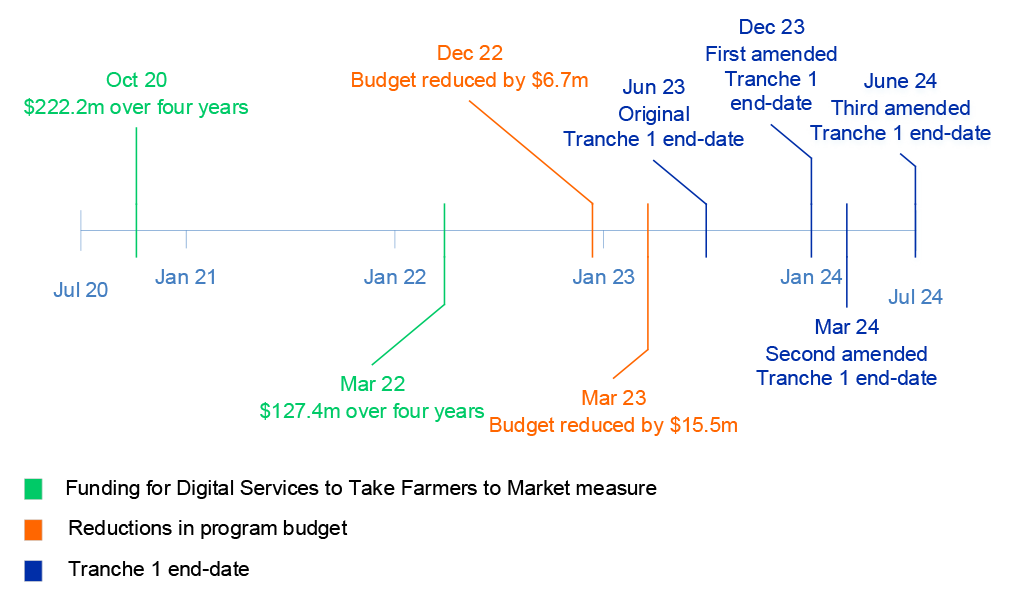

- In 2022–23, the department reduced the program budget by $22.2 million to support the department’s spending reduction efforts.

What did we find?

- The department’s administration of the digital reform of the agricultural export systems is partly effective.

- Governance arrangements are largely effective.

- Implementation is partly effective.

- Arrangements to manage change and monitor and report on benefits are partly effective.

What did we recommend?

- There were seven recommendations relating to measuring program outcomes; managing shared risk; establishing end-states for tranches and initiatives; change management; ensuring that benefits are measurable and evidence-based; and progress and performance reporting.

- The department agreed to seven recommendations.

$85bn

forecast value ofAustralia’s agricultural production for 2024–25.

54%

of the program’s Tranche 1 initiatives have been delivered or partially delivered.

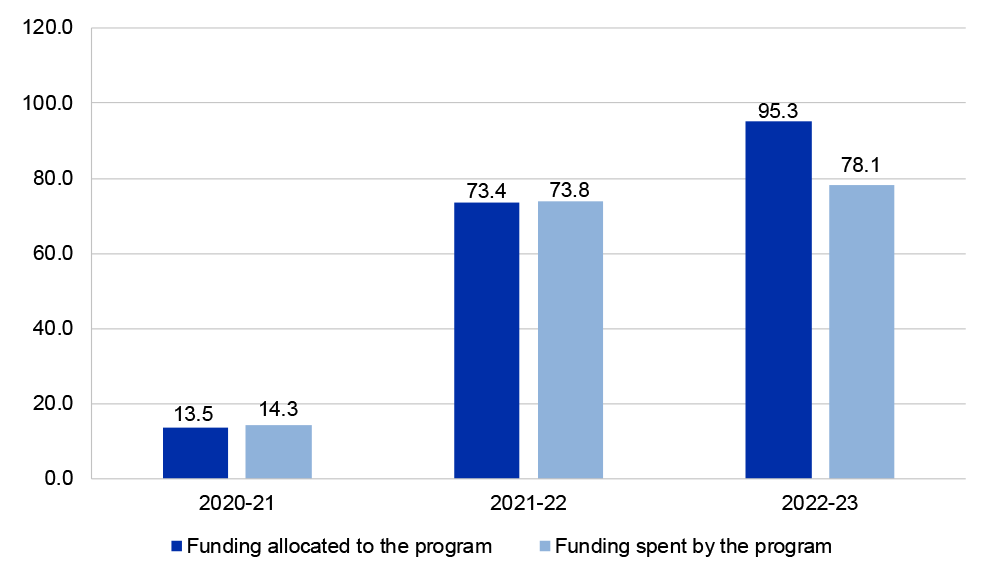

$252m to $1bn

approximate value of financial benefits forecast to be achieved by the program over five years.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The value of Australia’s agricultural production is forecast to rise by six per cent to $85 billion in 2024–25.1 Australia exports approximately 72 per cent of the total value of agricultural, fisheries and forestry production.2 The Australian Government regulates the export of agricultural, fisheries and forestry products, issuing export documentation that verifies that the goods being exported meet both the Australian export requirements and the importing country’s requirements.3

2. The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (the department) uses information and communications technology (ICT) systems to regulate and facilitate the export of agricultural, fisheries and forestry products and to issue export documentation.

3. In the 2020–21 Budget, the Australian Government committed $328.4 million over four years for a package of measures titled ‘Busting Congestion for Agricultural Exporters’. The Digital Services to Take Farmers to Markets measure accounted for $222.2 million of this funding and was intended to modernise Australia’s agricultural export systems.4

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The effective administration of the digital reform of agricultural export systems is intended to minimise disruption to exports and provide exporters with the benefits of faster, more reliable and cost-effective export services.

5. Past external reviews and ANAO performance audits of the department have found weaknesses in the department’s governance and culture, as well as its arrangements to manage its performance as a regulator.5

6. Large-scale ICT improvement programs aimed at uplifting or replacing aging ICT systems are increasingly common across Australian Government entities. Recent audits of other ICT improvement programs have found weaknesses in monitoring and reporting on the program’s status and performance, which increases the risk that the program fails to deliver outcomes and limits effective measurement of benefits realisation.6

7. This audit provides assurance to Parliament on the effectiveness of the department’s administration of the digital reform of the agricultural export systems.

Audit objective and criteria

8. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the department’s administration of the digital reform of the agricultural export systems.

9. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria.

- Has the department established effective governance arrangements for the program?

- Is the department implementing the program effectively?

- Is the department managing change for the program effectively?

10. The Australian Government has been investing in the digital reform of the agricultural export systems through a series of measures (see paragraphs 1.4 to 1.7).

11. The audit focused on the department’s administration of the package of work approved by the Australian Government in October 2020 and relevant in-flight initiatives. This work is being delivered in three tranches, the first of which was scheduled to conclude at the end of 2022–23. The audit focused on the delivery of the first tranche (Tranche 1).

12. This package of work is funded by the Digital Services to Take Farmers to Market budget measure and builds on elements of work undertaken under previous measures, such as the delivery of a digital export certification management system. The report refers to this package of work collectively as ‘the program’.

13. The audit did not examine:

- the effectiveness of individual initiatives or projects administered by the program;

- the delivery of digital initiatives that are not related to the export systems; or

- whole-of-government initiatives such as the Simplified Trade System.7

Conclusion

14. The department is partly effective in administering the digital reform of the agricultural export systems. The program focuses on short-term delivery goals without consideration of how this will contribute to the delivery of tranche or program end-states. There is a risk that the work being undertaken by the program may not effectively achieve the outcomes or benefits the program has committed to deliver.

15. The program’s governance arrangements are largely effective. The department prepared and presented first and second pass business cases for the program to the Australian Government as well as a Business Case Addendum to document the department’s implementation of the program. It does not document how the program’s outcomes will be measured. The department has established governance arrangements to support the Senior Responsible Officer to deliver the agreed program outcomes and the realisation of the program benefits. The department has established assurance arrangements and risk and issue management arrangements for the program. The department is not identifying and managing program risks that extend beyond the department and require shared oversight and management.

16. The department’s implementation of the program is partly effective. The department established a Tranche 1 implementation plan that did not specify an end-state for Tranche 1. In March 2024, the department advised the ANAO that, of the 35 initiatives in Tranche 1, six (17 per cent) had been delivered and 13 (37 per cent) had been partially delivered. In November 2022, the Executive Board agreed to spending reductions across the department to address a forecast departmental overspend. In December 2022 and March 2023, the program’s budget was reduced to support the department’s efforts to reduce spending. This resulted in the program stopping planned work, pausing the implementation of initiatives and reducing contractor staffing. The department established consultation and communication arrangements for the program.

17. The department’s arrangements to manage, measure and report on changes made through its digital reform program are partly effective. The department has not fully implemented change management arrangements for the program. Not all agricultural export ICT systems have authority to operate. While the department has established a benefits management framework, it has not established an evidence-based baseline or methodology. Internal reporting is limited to short-term delivery goals. It does not include reporting on the program’s progress in delivering the outcomes that the program has committed to deliver. The department has continued to receive significant or moderate findings from the ANAO regarding its external reporting to the Parliament.

Supporting findings

Governance

18. The department prepared and presented first and second pass business cases to the Australian Government in October 2018 and July 2020 respectively. In October 2021, the department presented a Business Case Addendum to the Australian Government to document the department’s implementation of the program. It does not document how its outcome statements will be measured. Without measurable outcomes, the department’s ability to effectively monitor and report on the achievement of the program’s implementation is limited and there is a risk that the work being undertaken by the program may not effectively achieve the program outcomes or benefits. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.22)

19. The Senior Responsible Officer (SRO) is accountable to the accountable authority for the delivery of the agreed program outcomes and the realisation of the program benefits. The department has established policies and strategies for the program as well as governance bodies to support the Senior Responsible Officer. The department has established assurance arrangements for the program and is subject to assurance activities for the program, such as Department of Finance Gateway Reviews and internal audits. (See paragraphs 2.23 to 2.58)

20. The department has established risk and issue management arrangements for the program, which align with the department’s Enterprise Risk Management Framework and Policy. The program maintains centralised risk and issue registers. The program has developed a risk management plan that details the key risks for the program and how they are being managed. The department is not identifying and managing program risks that extend beyond the department and require shared oversight and management. (See paragraphs 2.59 to 2.83)

Implementation

21. The department established a Tranche 1 implementation plan that did not specify an end-state for Tranche 1. In March 2024, the department advised the ANAO that, of the 35 initiatives in Tranche 1, six (17 per cent) had been delivered; 13 (37 per cent) had been partially delivered; and 16 (46 per cent) had been discontinued, consolidated into other initiatives, or were under development. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.26)

22. Funding for the Digital Services to Take Farmers to Market measure amounted to $199.9 million for 2020–21 to 2022–23. During this period, the department spent $166.2 million. In November 2022, the Executive Board agreed to spending reductions across the department to address a forecast departmental overspend. In December 2022 and March 2023, the program’s budget was reduced to support the department’s efforts to reduce spending. This resulted in the program stopping planned work for the program, pausing the implementation of initiatives and reducing contractor staffing. The department established a sourcing strategy and financial management arrangements for the program and its financial reporting accurately reflected the financial records in the department’s financial management system. (See paragraphs 3.27 to 3.57)

23. The department established consultation and communication arrangements for the program. The department is not coordinating consultation and communication activities that are being undertaken by program teams. (See paragraphs 3.58 to 3.68)

Change management, monitoring benefits and reporting

24. The program has not fully implemented the change management arrangements established by the department. The program is not completing impact assessments for all of its projects and is not completing readiness assessments for all projects with ‘medium’ and ‘high’ impact changes. As at June 2023, 67 per cent of exports-related instructional material documents were overdue for review. Not all of the agricultural export systems have active authority to operate. The department has not documented whether the functionality of those systems without active authority to operate would require an active authority to operate. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.25)

25. The department has established a benefits management framework and is reporting on the achievement of financial benefits for program initiatives. The department has not established an evidence-based baseline or methodology for the total forecast value of the program’s benefits. The department is unable to demonstrate that its benefits reporting provides decision-makers with complete and accurate information on the realisation of financial benefits for the program. (See paragraphs 4.26 to 4.53)

26. Program reporting is limited to short-term delivery goals. It does not focus on reporting on the program’s progress in delivering Tranche 1 as a whole, or the program initiatives’ progress in achieving their established end-states. Nor does it report on progress in achieving program outcomes. This limits the SRO’s ability to effectively monitor the progress of the program as a whole and to determine whether the program is on track to deliver its commitments on time and within budget. The department has continued to receive significant or moderate findings from the ANAO regarding its external reporting to the Parliament. (See paragraphs 4.54 to 4.90)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.21

The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry determine how:

- the program’s initiatives will contribute to the delivery of the program’s outcomes; and

- the achievement of the program’s outcomes will be measured.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.82

The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry identify and manage program risks that extend beyond the department and require shared oversight and management.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.21

The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry establish end-states for program tranches prior to tranche implementation.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 4.12

The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry complete impact assessments and readiness assessments in accordance with the change management arrangements established by the department.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.22

The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry ensure that all ICT systems that process, store or communicate information and data have an active authority to operate.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 4.52

The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry review its benefits management arrangements for the program to ensure that all benefits are measurable and evidence-based, including:

- establishing appropriate baselines for each benefit;

- establishing methodologies to measure each benefit; and

- ensuring consistent reporting of realised benefits to inform decision-makers regarding progress towards achieving the program’s expected benefits.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 4.76

The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry review and update its reporting arrangements to ensure that progress and performance reporting includes:

- reporting against the outcomes of the program, as a whole, and how the work being undertaken is contributing to these outcomes; and

- consistent updates on the program’s overall progress towards the delivery of the program’s outcomes, so that performance can be effectively measured over time.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (the department) is committed to appropriate and timely implementation of the seven recommendations of the report, all of which we agree.

The recommendations focus on establishing and measuring program initiatives and outcomes, risk management, change management, benefits management, and progress and performance reporting. These recommendations provide valuable insight to inform work underway in the department to deliver digital reform of the agricultural export systems.

The department welcomes the ANAO’s assessment that the governance arrangements for the digital reform of the agricultural export systems are largely effective, with such arrangements established to support the Senior Responsible Officer to deliver the agreed program outcomes and the realisation of the program benefits. The department also notes the ANAO’s assessment that financial reporting accurately reflected the records in the department’s financial management system.

The department acknowledges it can benefit from improving processes for managing shared risks, measuring and reporting benefits and ensuring consistency with departmental processes, and notes work is underway to clarify the documentation of end states and enhance reporting against progress in delivering the program.

The department also notes work is already underway to action the matters identified by the report as opportunities for improvement.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

27. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy/program design

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The value of Australia’s agricultural production is forecast to rise by six per cent to $85 billion in 2024–25.8 Australia exports approximately 72 per cent of the total value of agricultural, fisheries and forestry production.9 The Australian Government regulates the export of agricultural, fisheries and forestry products, issuing export documentation that verifies that the goods being exported meet both the Australian export requirements and the importing country’s requirements.10

1.2 The entity responsible for the regulation of the export of agricultural, fisheries and forestry products is the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.11 The report refers to the entity as ‘the department’, unless distinction is required. During the period covered by the audit, the entity responsible for the regulation of the export of agricultural, fisheries and forestry products has been the: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (from 29 May 2019 to 31 January 2020); Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (from 1 February 2020 to 30 June 2022); and Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (from 1 July 2022 to date).

Digital reform of agricultural export systems

1.3 The department uses information and communications technology (ICT) systems to regulate and facilitate the export of agricultural, fisheries and forestry products and to issue export documentation, including the:

- Export Documentation System (EXDOC), which is used ‘to generate export documentation’ to ‘export prescribed primary produce from Australia’12;

- New Export Documentation System (NEXDOC), which is used to ‘generate export documentation’ and ‘introduces new features and enhances existing ones to streamline the export documentation process’13;

- Export Establishment Registration Database (ER), which is used to store information relating to registered establishments that prepare, store, handle and/or present for inspection prescribed goods for export14;

- Tracking Animal Certification for Export system (TRACE), which is used to manage ‘the application and approval processes for consignments of livestock and animal reproductive material exported from Australia’15;

- Plants Export Management System (PEMS), which is used to ‘capture and store information relating to the export of plants and plant products from Australia; including plant export Authorised Officer (AO) inspection and calibration results for product and transport units and all supporting documentation’16; and

- Manual of Importing Country Requirements (Micor), which is a resource that provides guidance for exporters on importing country requirements.17

Export Certification Modernisation and Digitisation

1.4 In the 2019–20 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, the Australian Government committed $29.2 million over four years to ‘streamline export processes by completing the delivery of a digital export certification management system, which will provide a modern and secure approach to assuring that produce meets importing country requirements’.18 This measure is referred to by the department as the Export Certification Modernisation and Digitisation (ECMOD) measure.

Busting Congestion for Agricultural Exporters package

1.5 In the 2020–21 Budget, the Australian Government committed $328.4 million over four years for a package of measures titled Busting Congestion for Agricultural Exporters. The package aimed to ‘transform Australia’s weak and outdated systems and processes into a cost-effective model to get products to export markets faster and more efficiently’ and ‘establish modern digital services, reduce regulatory cost and administration and improve interactions with export systems’.19

Digital Services to Take Farmers to Market

1.6 The Digital Services to Take Farmers to Markets measure, which was described as the ‘centrepiece of the reform package’, accounted for $222.2 million of this funding and was intended to:

modernise Australia’s agricultural export systems by slashing red-tape and improving regulation and service delivery for our producers and exporters. This measure will transition our systems online and provide a single portal for transactions between exporters and government, streamlining processes for exporters and helping them experience faster and more cost-effective services.20

1.7 In March 2022, the department received an additional $127.4 million over four years ‘to continue and expand the Digital Services to Take Farmers to Market initiative to transform the delivery of Government agricultural export systems’.21

Agricultural exports

1.8 The gross value of Australian agricultural production has increased by 51 per cent in the last 20 years in real terms (adjusted for consumer price inflation), from approximately $62.2 billion in 2003–04 to $94.3 billion in 2022–23.22 When including fisheries and forestry, the total value of agricultural, fisheries and forestry production has increased by 46 per cent, from approximately $68.5 billion in 2003–04 to $100.1 billion in 2022–23.23

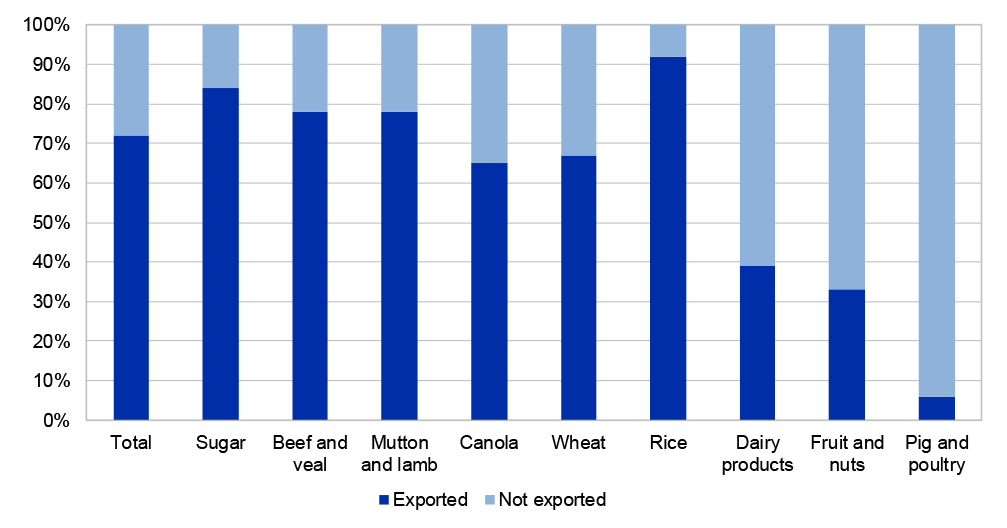

1.9 In real terms, the value of agricultural exports has fluctuated between $44 billion and $80 billion annually since 2003–04. In the three years to 2019–20, Australia exported approximately 72 per cent of the total value of agricultural, fisheries and forestry production. The proportion of goods exported varied by commodity, with more than 80 per cent of rice and sugar being exported on average from 2017–18 to 2019–20, compared to less than 10 per cent of pig and poultry (Figure 1.1).24

Figure 1.1: Share of agricultural production exported by sector

Note: The information presented is a three-year average from 2017–18 to 2019–20.

Source: ANAO representation of Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES), ABARES Insights: Snapshot of Australian Agriculture 2024, March 2024, figure 6.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.10 The effective administration of the digital reform of agricultural export systems is intended to minimise disruption to exports and provide exporters with the benefits of faster, more reliable and cost-effective export services.

1.11 Past external reviews and ANAO performance audits of the department have found weaknesses in the department’s governance and culture, as well as its arrangements to manage its performance as a regulator.25

1.12 Large-scale ICT improvement programs aimed at uplifting or replacing aging ICT systems are increasingly common across Australian Government entities. Recent audits of other ICT improvement programs have found weaknesses in monitoring and reporting on the program’s status and performance, which increases the risk that the program fails to deliver outcomes and limits effective measurement of benefits realisation.26

1.13 This audit provides assurance to Parliament on the effectiveness of the department’s administration of the digital reform of the agricultural export systems.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.14 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the department’s administration of the digital reform of the agricultural export systems.

1.15 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria.

- Has the department established effective governance arrangements for the program?

- Is the department implementing the program effectively?

- Is the department managing change for the program effectively?

1.16 The Australian Government has been investing in the digital reform of the agricultural export systems through a series of measures (see paragraphs 1.4 to 1.7).

1.17 The audit focused on the department’s administration of the package of work approved by the Australian Government in October 2020 and relevant in-flight initiatives. This work is being delivered in three tranches, the first of which was scheduled to conclude at the end of 2022–23. The audit focused on the delivery of the first tranche (Tranche 1).

1.18 This package of work is funded by the Digital Services to Take Farmers to Market budget measure and builds on elements of work undertaken under previous measures, such as the delivery of a digital export certification management system. The report refers to this collectively as ‘the program’.

1.19 The audit did not examine:

- the effectiveness of individual initiatives or projects administered by the program;

- the delivery of digital initiatives that are not related to the export systems; or

- whole-of-government initiatives such as the Simplified Trade System.27

Audit methodology

1.20 The audit methodology included:

- examining the department’s documentation, with a focus on documents that relate to the program’s governance, strategic planning, benefits realisation, financial management and monitoring and reporting;

- examining system incident logs and accreditation documentation;

- walkthroughs to demonstrate the system capabilities reported as having been achieved;

- reconciliation of contracts for the program with AusTender data;

- reconciliation of program financial records with departmental financial records; and

- meetings with relevant department staff.

1.21 The ANAO received no submissions from the public via the citizen contribution facility on the ANAO website.

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $622,700.

1.23 The team members for this audit were Casey Mazzarella, Jake Farquharson, Sky Lo, Michelle Penalurick, Talia Song, Dale Todd, Nathan Daley, Naveed Nisar, Jamie Lee and Corinne Horton.

2. Governance

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (the department) has established effective governance arrangements for the digital reform of the agricultural export systems (the program).

Conclusion

The program’s governance arrangements are largely effective. The department prepared and presented first and second pass business cases for the program to the Australian Government as well as a Business Case Addendum to document the department’s implementation of the program. It does not document how the program’s outcomes will be measured. The department has established governance arrangements to support the Senior Responsible Officer to deliver the agreed program outcomes and the realisation of the program benefits. The department has established assurance arrangements and risk and issue management arrangements for the program. The department is not identifying and managing program risks that extend beyond the department and require shared oversight and management.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations for the department to determine how the program’s initiatives will deliver outcomes and how the achievement of outcomes will be measured; and to identify and manage program risks that extend beyond the department.

2.1 The department identified the need for investment in the reform and ICT28 modernisation of Australia’s agricultural export systems. The Commonwealth Digital and ICT Oversight Framework (IOF) includes the following key elements that support the government to manage digital and ICT-enabled investments:

- developing and presenting detailed business case(s) for consideration by the Australian Government to inform its decision on investment in the program of work proposed29;

- establishing and maintaining appropriate governance and assurance arrangements30; and

- establishing and maintaining effective risk management arrangements.31

Is the program supported by an appropriate business case?

The department prepared and presented first and second pass business cases to the Australian Government in October 2018 and July 2020 respectively. In October 2021, the department presented a Business Case Addendum to the Australian Government to document the department’s implementation of the program. It does not document how its outcome statements will be measured. Without measurable outcomes, the department’s ability to effectively monitor and report on the achievement of the program’s implementation is limited and there is a risk that the work being undertaken by the program may not effectively achieve the program outcomes or benefits.

First and second pass business case

2.2 Digital and ICT-enabled policy proposals with financial implications of $30 million or more are subject to the ICT Investment Approval Processes (IIAP). These proposals go through a staged government approval process. At each stage of approval, the agency is required to develop a business case. This ‘ensures that the Cabinet and its relevant committees have sufficient information about the proposal to make an informed investment decision’.32

2.3 In October 2018, the department presented a first pass business case (1PBC) to the Australian Government for a package of reforms to modernise Australia’s agricultural trade. It outlined the need for digital reform, advising that international trade is becoming increasingly digital and that the volume of exports and industry participants as well as the number of export certificates issued by the department is increasing. It explained that importing country regulatory requirements are becoming more sophisticated, which increases the complexity of export certification and associated compliance activities. The 1PBC detailed the department’s technical environment, business problem, stakeholder impact and risks.

2.4 In July 2020, the department presented the second pass business case (2PBC) to the Australian Government for consideration. The 2PBC provided an update on the department’s operating environment and advised that the program will deliver 16 modern digital services from which three financial and three non-financial benefits would be realised.

2.5 The 2PBC proposed that the program would be delivered over six years from 2020–21, delivered in three ‘tranches’ with each tranche comprising two years. The 2PBC outlined packages of work that the program would deliver. These packages of work were referred to as ‘initiatives’ and were described as ‘outcomes-based’, with each initiative contributing to the development of one or more digital services.

2.6 In October 2020, the Australian Government agreed to proceed with Tranche 1, with options to proceed with the subsequent tranches to be considered in the 2022–23 Budget. The Australian Government approved funding for Tranche 1 over four years from 2020–21 to 2023–24. The Minister for Agriculture, Drought and Emergency Management announced that the Australian Government was investing in a ‘suite of reforms [that] will modernise Australia’s export systems by slashing red-tape and streamlining regulation and service delivery for our farmers’.33 The Minister explained that this included:

$222.2 million over 4 years for digital services to take farmers to market. This will deliver a modern and reliable digital service to help farmers do business quickly and cost effectively – a single touchpoint for exporters that is available 24/7.34

2.7 The package of work outlined in the 2PBC is funded by the Digital Services to Take Farmers to Market budget measure and builds on elements of work undertaken through previous measures, such as the delivery of a digital export certification management system. The report refers to this collectively as ‘the program’.

Business case addendum

2.8 In April 2021, the first mid-stage Department of Finance Gateway Review35 of the program found that there was a disconnect between the work being delivered by the department and the program of work outlined in the 2PBC. It noted that:

The 2PBC included a Benefits Realisation Framework of investment outcomes, benefits resulting from these outcomes (that are both financial and non-financial), change priorities, key capabilities and key initiatives (outputs). This framework is appropriate however needs to reflect the pivot that the program has recently undertaken.

2.9 The Gateway Review noted that ‘a benefits realisation plan does not currently reflect this pivot or how this significant change to the program will be implemented’. The Gateway Review recommended that the department ‘develop a business case addendum to reflect the revised approach to deliver business value earlier’. Benefits realisation is discussed at paragraphs 4.26 to 4.51.

2.10 In October 2021, the department sought funding for future tranches of the program as part of a broader whole-of-government reform agenda to simplify Australia’s international trade. The department provided the Australian Government with a Business Case Addendum (BCA) to document the department’s implementation of the program.

2.11 The BCA included a program roadmap, which listed the initiatives that would be delivered by the program. The roadmap provided an indication of the start and end date for 63 initiatives, mapped across three tranches. Tranche 1 was scheduled from 2020–21 to 2022–23; Tranche 2 was scheduled from 2023–24 to 2024–25; and Tranche 3 was scheduled for 2025–26.

2.12 The program roadmap listed 31 initiatives that would commence in Tranche 1 (with 28 to be completed in Tranche 1 and three to be completed in Tranche 2); 31 that would commence in Tranche 2 (with 17 to be completed in Tranche 2 and 14 to be completed in Tranche 3); and one that would commence and be completed in Tranche 3.

2.13 In March 2024, the department advised the ANAO that ‘the initiatives described within the [BCA] program roadmap … are intended to replace those listed in the 2PBC’.

2.14 The BCA listed four outcome statements that described benefits arising from the completion of the program, including making industry’s export experience and the department’s regulation of exports easier and improving the quality of data and systems.

2.15 The BCA listed three financial benefits and one non-financial benefit that would be realised by the program. More information about the program’s benefits is at paragraphs 4.26 to 4.51.

2.16 The second mid-stage Department of Finance Gateway Review stated that its recommendation had been fully addressed:

The business case addendum has been developed and included as an attachment for the comeback to government.

…

The review team notes that the program has informed Government on the updated baseline of the TFTM Program within the existing timeframes, with some deliverables extending [into] Tranche 2.

Measurable outcomes

2.17 The 2PBC outlined the initiatives that would be delivered by the program and the 16 digital services that would be developed by this work. The 16 digital services were largely documented as measurable statements of capability, such as sign in once to access all functionalities; access to information is managed based on authorisation levels; and digital certifications by default, paper certification by exception.

2.18 The BCA listed 63 initiatives that would be delivered by the program and four outcome statements. The outcome statements described benefits that are anticipated to arise from the program. The BCA does not document how the outcome statements will be measured.

2.19 Measurable outcomes are an important element of effective oversight and accountability. Without measurable outcomes, the department’s ability to effectively monitor and report on the achievement of the program’s implementation (see paragraphs 4.54 to 4.75) is limited. This also limits the department’s ability to determine whether it is on track to deliver the program on time and within budget.

2.20 By focusing on the delivery of the program’s initiatives without reference to or consideration of how they will deliver the outcomes that the program has committed to deliver (digital services and outcome statements), there is a risk that the work being undertaken by the program may not effectively achieve the program outcomes or benefits.

Recommendation no.1

2.21 The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry determine how:

- the program’s initiatives will contribute to the delivery of the program’s outcomes; and

- the achievement of the program’s outcomes will be measured.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry response: Agreed.

2.22 The department will undertake further work on mapping initiatives to the outcomes specified in the business case. Formal processes are underway to measure and report performance against these outcomes.

Is the program supported by appropriate oversight?

The Senior Responsible Officer (SRO) is accountable to the accountable authority for the delivery of the agreed program outcomes and the realisation of the program benefits. The department has established policies and strategies for the program as well as governance bodies to support the Senior Responsible Officer. The department has established assurance arrangements for the program and is subject to assurance activities for the program, such as Department of Finance Gateway Reviews and internal audits.

Taking Farmers to Market Program

2.23 In October 2019, the department started drafting the Taking Farmers to Market Program Management Plan (Program Management Plan).

2.24 In February 2021, the Trade Reform Board (TRB) approved the operating model for digital trade initiatives in the portfolio, establishing the Taking Farmers to Market (TFTM) program to deliver the program of work funded by the Digital Services to Take Farmers to Market budget measure (the program).

2.25 In March 2021, the department commenced drafting the Taking Farmers to Market Governance Plan (Governance Plan).

2.26 In April 2021, the Program Management Plan was finalised and approved. In October 2021, the Governance Plan was approved.

2.27 The Program Management Plan states that the program is intended to deliver a ‘suite of contemporary and connected digital services for exporters, reducing the administrative burden by streamlining the multiple manual processes and reducing the associated effort for business and the department’. It explains that:

The program’s focus is the digital transformation of Australia’s agricultural export systems to help get agricultural products to market faster. It will deliver a modern and reliable digital service to help exporters do business quickly and cost effectively – a single touch point for exporters that is available 24/7.

2.28 From October 2021, work related to the development and delivery of a digital export certification management system (NEXDOC) and transition of commodities to NEXDOC was included in the program.36

Governance structure

2.29 The Deputy Secretary of the Agricultural Trade Group is the Senior Responsible Officer (SRO) for the program. The SRO is accountable to the accountable authority37 for the delivery of the agreed program outcomes and the realisation of program benefits.

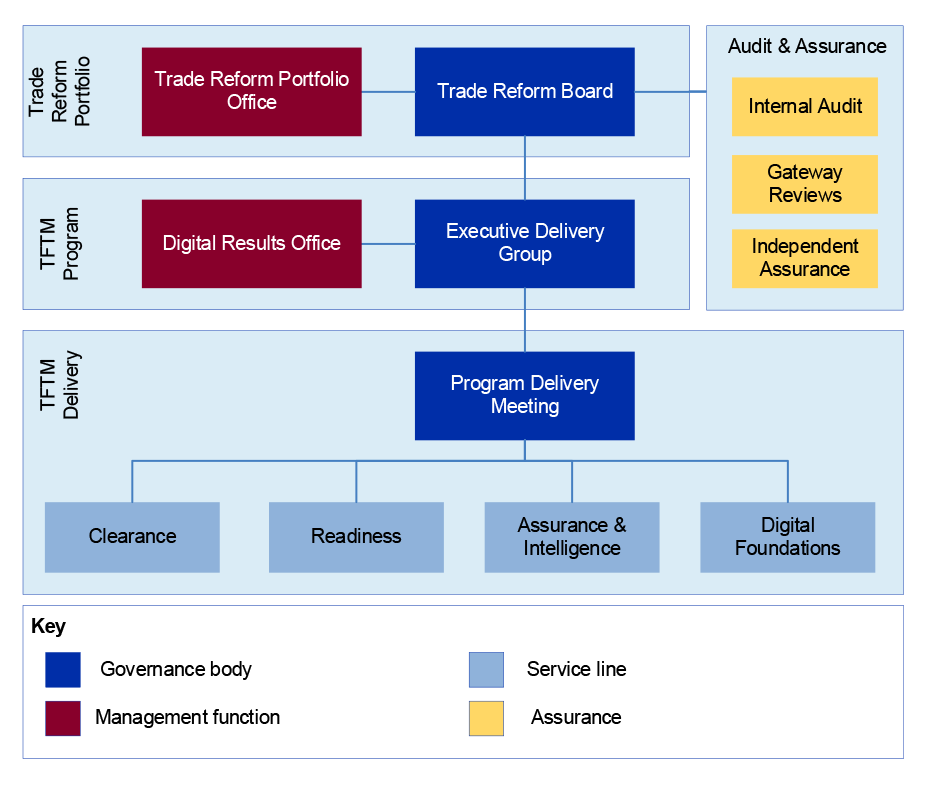

2.30 The Program Management Plan and the Governance Plan document the program’s governance arrangements. Figure 2.1 illustrates the governance structure from June 2022 to May 2023. In May 2023, the program’s governance arrangements were restructured (this is discussed in more detail at paragraphs 2.32 to 2.34).

2.31 The program’s governance bodies are outlined in Table 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Program governance structure, June 2022 to May 2023

Source: Adapted from Governance Plan.

2.32 In March 2023, the TRB noted that the ‘Trade Reform Portfolio Office (TRPO) has been required to adjust its service offering since December 2022, in light of resource reductions due to the department’s difficult FY2022–23 financial position’.

2.33 In May 2023, the TRB agreed that it would be stood down and the Trade Reform Portfolio Office would cease providing ‘all governance and support services to the Trade Reform Portfolio of programs’. Support services such as the Communications Team and the Change Management Team are discussed from paragraphs 3.59 to 3.63 and in Table 4.1 respectively.

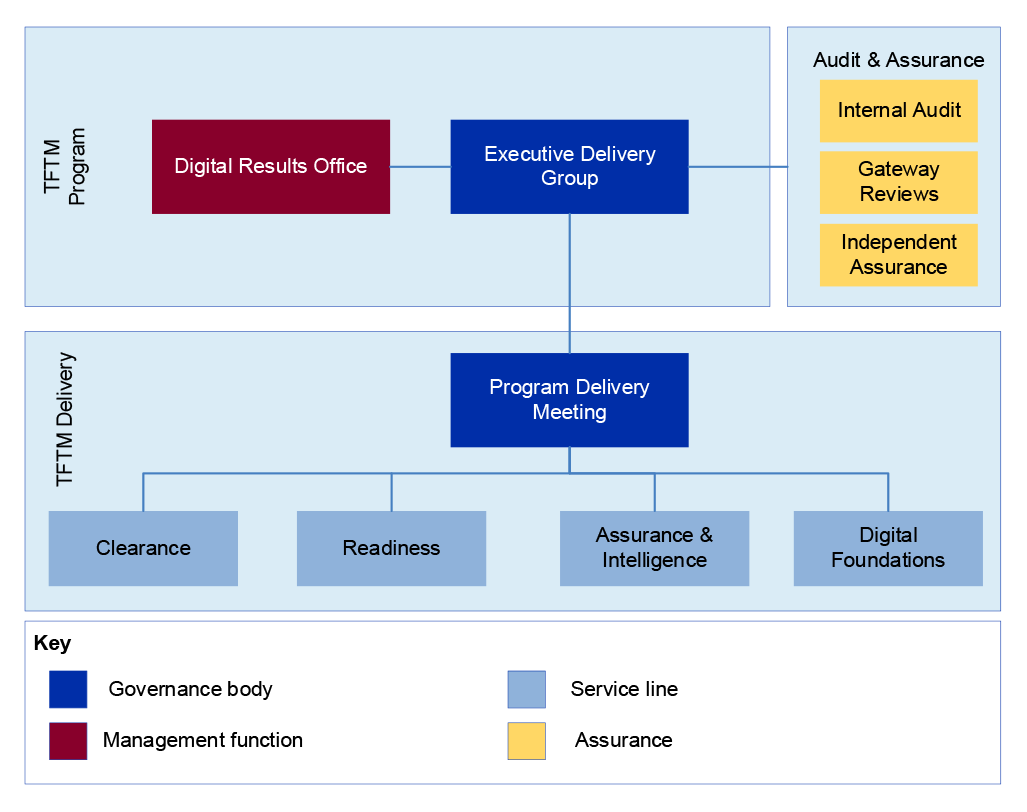

2.34 The TRB agreed that ‘all digital, and digitally connected projects [be] governed solely by the Executive Delivery Group’. Figure 2.2 illustrates the program’s governance structure from May 2023.

Figure 2.2: Program governance structure, from May 2023

Source: Adapted from Governance Plan.

Table 2.1: Program governance bodies

|

Governance Body |

Operation |

Membership |

Purpose |

ANAO comments |

|

Trade Reform Board (TRB) |

|

It also had an external independent board observer and was advised by the Chief General Counsel. |

|

|

|

Executive Delivery Group (EDG) |

|

It is also advised by seven Assistant Secretariesf, the TFTM Program Manager and the TFTM Program Architect. |

|

|

|

Program Delivery Meeting (PDM) |

|

|

|

|

Note a: The Head of Digital Trade Strategy and Initiatives also holds the title TFTM Program Director.

Note b: First Assistant Secretary, Trade Market Access & International; First Assistant Secretary, Plant and Live Animal Exports; First Assistant Secretary, Exports and Veterinary Services; First Assistant Secretary, Biosecurity Strategy and Reform; and First Assistant Secretary, Digital Reform.

Note c: Between August 2021 and August 2023, the EDG was chaired by the Head of Digital Trade Strategy and Initiatives. From August 2023, the EDG is chaired by the SRO, with the Head of Digital Trade Strategy and Initiatives as Deputy Chair.

Note d: First Assistant Secretary, Exports & Veterinary Services; First Assistant Secretary, Traceability, Plant & Live Animal Exports; First Assistant Secretary, Trade & International.

Note e: Branch Manager, Investment Advice and Contestability, Digital Transformation Agency. The terms of reference describe the representative’s role as ‘monitors implementation of assurance arrangements and ensures minimum requirements are met’.

Note f: Assistant Secretary, Meat Exports; Assistant Secretary, Plant Export Operations; Assistant Secretary, Live Animal Exports; Assistant Secretary, Residues & Food; Assistant Secretary, Digital Clearance Service; Assistant Secretary, Digital Platforms & Products; Assistant Secretary, Digital Strategy.

Source: ANAO summary of departmental documents.

Trade Reform Portfolio Office

2.35 The Trade Reform Portfolio Office (TRPO) was established in February 2021 to provide ‘support for strategy, investment, governance’ and manage ‘portfolio-level risks and dependencies that could compromise benefits realisation’. The TRPO ceased in May 2023.

Digital Results Office

2.36 The Digital Results Office (DRO) was established in February 2021 to ‘drive the planning and delivery work required to achieve program outcomes and benefits’. The DRO ‘supports program operations and ensures that the program remains strategically aligned to the broader portfolio’.

Program plans and strategies

2.37 In addition to the Program Management Plan and Governance Plan, the department has established several plans and strategies for the program, including:

- Sourcing Strategy (approved in January 2020);

- Risk and Issue Management Strategy (approved in September 2021);

- Assurance Strategy (approved in October 2021);

- Benefits Management Plan (approved in December 2021);

- Financial Management Plan (approved in December 2022);

- Reporting Plan (dated January 2023); and

- Risk Management Plan (approved in June 2023).

2.38 In March 2024, the department updated the program plans and strategies to remove references to the TRB.

2.39 The program is also currently using plans and strategies from the former Trade Reform Portfolio. For example:

- Trade Reform Communication Strategy (dated July 2022) (see paragraphs 3.59 to 3.61);

- Trade Reform Change Management Strategy (approved in September 2022) (see paragraphs 4.3 to 4.6); and

- Trade Reform Portfolio Benefits Management Strategy (dated September 2021) (paragraph 4.27).

2.40 These strategies relied on governance and other support structures and bodies that ended with the dissolution of the TRB and cessation of the TRPO in May 2023.

Oversight

2.41 The program’s governance frameworks and bodies have been established to support the SRO in ensuring that the program delivers the agreed outcomes and benefits. Governance bodies receive reporting regarding the status of the program’s initiatives (see paragraphs 4.59 to 4.75); risks and issues (see paragraphs 2.73 to 2.77); and the program budget (see paragraphs 3.40 to 3.43).

2.42 Program reporting is limited to short-term delivery goals and does not report on progress achieving the outcomes of the program as a whole, which the SRO is accountable to deliver. This may limit the SRO’s ability to effectively oversee the program’s progress and to make informed decisions regarding the direction of the program.

Assurance arrangements

2.43 In June 2021, the department engaged Terrace Services as a program assurer. Terrace Services38 was contracted to:

- ‘develop a plan for assurance activities across the life of the program’;

- ‘in line with the agreed plan … conduct assurance activities and report findings and make recommendations to the SRO and Program Director’; and

- ‘at the discretion of the SRO and Program Director … undertake targeted assurance activities as may be required to address, for example, program risks or delivery concerns’.

2.44 In October 2021, the department established an Assurance Strategy for the program. The most recent version is dated January 2023. The Assurance Strategy outlines the assurance arrangements for the program (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2: Program assurance model

|

Line of defence |

Elements |

Focus |

|

First: Day to day management and control |

|

|

|

Second: Governing functions |

|

|

|

Third: Independent assurance |

|

|

Source: Adapted from TFTM Assurance Strategy.

2.45 The program’s risk management arrangements are discussed at paragraphs 2.59 to 2.66 and the program’s plans and strategies are examined at paragraphs 2.37 to 2.40.

Assurance activities

Terrace Review

2.46 In December 2022, Terrace Services conducted a Product Teams Review (Terrace Review) for the program. It examined ‘whether TFTM’s operating model will deliver on intended commitments and realise intended benefits’, reviewing the program’s planning; leadership and coordination; delivery health; and benefits realisation.

2.47 The Terrace Review reported on ‘challenges associated with both the program’s novel delivery approach within DAFF and with its rapid expansion’, including:

- ‘Devolved approaches to scope definition, planning and coordination have resulted in challenges with dependency management and orchestration of activities across the program’;

- ‘Delivery, release and product uptake bottlenecks’; ‘unresolved dependencies’; and ‘conflicts between foundational capability and digital services technologies or implementations’; and

- ‘Cultural considerations have impacted the effective operation of delivery, governance and reporting practices that would typically be expected in a program of TFTM’s size’, with ‘delivery oversight and orchestration risks’ being introduced as a result of ‘organic and un-curated pursuit of product development’.

2.48 The Terrace Review found that the department’s approach ‘is not best suited for delivery of value for money and business benefits across the TFTM program’. It stated that ‘Top-down leadership, direction and monitoring is essential for accountability and effectiveness’.

2.49 The review made five recommendations, each of which included actions to implement the recommendation. All five recommendations are listed as ‘high priority’. The review recommended a total of 22 actions, of which 17 were listed as ‘high’ priority and five were listed as ‘medium’ priority. The EDG received reports on the program’s progress in completing the action items arising from the review (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: Summary of completion status of Terrace Review action items

|

Implementation status |

Number of action items |

|

Completed, with supporting evidence |

3 |

|

Reported as complete in relation to Tranche 2 planning or expected delivery |

8 |

|

Reported as complete, without supporting evidence |

7 |

|

Incomplete |

4 |

|

Total |

22 |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documents, as at January 2024.

Gateway Reviews

2.50 Department of Finance Gateway Reviews (Gateway Reviews) ‘examine programs/projects at key decision points during design, implementation and delivery’. The reviews are conducted by the Department of Finance and aim ‘to provide independent, timely advice and assurance to the SRO as the person responsible for delivering the program/project outcomes’.39

2.51 Gateway Reviews provide a Delivery Confidence Assessment using a five-tiered rating system (green, green/amber, amber, amber/red, and red). The reviews also provide an assessment of key focus areas using a three-tiered rating system (green, amber and red).

2.52 As at May 2024, five Gateway Reviews have been conducted for the program: a first stage review in 2019 and four mid-stage reviews in 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024. The Gateway Reviews rated the delivery confidence for the program as green/amber, amber, or amber/red with several key focus areas rated as amber in each review (Table 2.4).

Table 2.4: Summary of program Gateway Reviews

|

Year of review |

Delivery confidence assessmenta |

Key focus areas with ratings of amber or redb |

|

2019 |

green/amberc |

|

|

2021 |

green/amberc |

|

|

2022 |

amberd |

|

|

2023 |

green/amberc |

|

|

2024 |

amber/rede |

|

Note a: The Gateway Reviews use five delivery confidence assessment ratings: green, green/amber, amber, amber/red and red.

Note b: The Gateway Reviews use three key focus area ratings: green, amber and red. Green is defined as ‘There are no major outstanding issues in this Key Focus Area that at this stage appear to threaten delivery significantly’. Amber is defined as ‘There are issues in this Key Focus Area that require timely management attention.’ Red is defined as ‘There are significant issues in this Key Focus Area that may jeopardise the successful delivery of the program.’

Note c: The Gateway Reviews define green/amber as ‘Successful delivery of the program to time, cost, quality standards and benefits realisation appears probable however constant attention will be needed to ensure risks do not become major issues threatening delivery.’

Note d: The Gateway Reviews define amber as ‘Successful delivery of the program to time, cost, quality standards and benefits realisation appears feasible but significant issues already exist requiring management attention. These need to be addressed promptly.’

Note e: The Gateway Reviews define amber/red as ‘Successful delivery of the program to time, cost, quality standards and benefits realisation is in doubt with major issues apparent in a number of key areas. Urgent action is needed to address these.’

Source: ANAO summary of findings of Gateway Reviews.

2.53 In May 2024, the department provided the April 2024 mid-stage Gateway Review. It found that ‘Successful delivery of the program to time, cost, quality standards and benefits realisation is in doubt with major issues apparent in a number of key areas’ and that ‘Urgent action is needed to address these.’ It explained that:

Since the last review the program has suffered serious delays and a reduction in scope, resources and program governance. These issues were mainly due to resource constraints imposed on the program during the agency’s financial crisis and consequent austerity measures.

…

Under difficult circumstances the program has delivered on most of the major technology elements and some business services in Tranche 1 and recovered from some of its significant resourcing pressures but there is still considerable doubt that Tranche 1 can be delivered by its revised deadline of June 2024.

…

Urgent action to progress the recommendations of the review including updating the minister on progress of the program, transitioning program approach and appointing a dedicated program director is needed.

2.54 The Gateway Reviews have made a total of 59 recommendations for the program to date. Recommendations are rated as ‘critical’, ‘essential’ or ‘recommended’.40 Once a recommendation is made, an update on its implementation is provided in the next Gateway Review, including an assessment of implementation by the Gateway Review team (Table 2.5). After this, implementation is no longer tracked in Gateway reports.

Table 2.5: Number of fully addressed Gateway Review recommendations — as assessed by Gateway Reviews

|

Year of review |

Fully addressed ‘critical’ recommendations |

Fully addressed ‘essential’ recommendations |

Fully addressed ‘recommended’ recommendations |

Total |

|

2019 |

1/1 (100%) |

2/4 (50%) |

3/5 (60%) |

6/10 (60%) |

|

2021 |

2/3 (67%) |

5/5 (100%) |

0/1 (0%) |

7/9 (78%) |

|

2022 |

1/2 (50%) |

2/4 (50%) |

4/4 (100%) |

7/10 (70%) |

|

2023 |

4/4 (100%) |

8/9 (89%) |

2/2 (100%) |

14/15 (93%) |

Source: ANAO summary of Gateway Reviews.

2.55 In April 2024, the fourth mid-stage Gateway Review made 15 recommendations: five critical, six essential and four recommended.

Internal audit

2.56 In May 2023, the department conducted an internal audit of the implementation of Gateway and Digital and ICT Investments Review Recommendations. The internal audit assessed the department’s processes to manage, monitor, and report on its Gateway and Digital and ICT Investments Review activities and recommendations.

2.57 The internal audit found that ‘the department has effective governance arrangements to oversee the Gateway and Digital and ICT Investments Review activities at the program level’. It noted that ‘program teams have established processes to address the recommendations arising from reviews’ but that ‘these processes are project-dependant and inconsistently documented’.

2.58 The review made one recommendation and noted two business improvement opportunities. In June 2023, the department reported to its Audit and Risk Committee that the recommendation had been implemented.

Have appropriate risk management arrangements been implemented?

The department has established risk and issue management arrangements for the program, which align with the department’s Enterprise Risk Management Framework and Policy. The program maintains centralised risk and issue registers. The program has developed a risk management plan that details the key risks for the program and how they are being managed. The department is not identifying and managing program risks that extend beyond the department and require shared oversight and management.

Risk and issue management

2.59 The department’s Enterprise Risk Management Framework and Policy (Enterprise Risk Framework) outlines the department’s arrangements to manage risk, including the department’s risk appetite and tolerance; risk matrix for assessing risk; and roles and responsibilities for risk management. The Enterprise Risk Framework states that the SRO ‘is ultimately responsible for ensuring that a program … meets its objectives and delivers the projected benefits and has the authority on how risks will be managed’.

2.60 The department has established risk and issue management arrangements for the program. The arrangements are documented in the Risk and Issue Management Strategy (Risk Management Strategy), approved in April 2021. The program’s arrangements align with the department’s Enterprise Risk Framework, using the same risk matrix to assess risks and risk appetite and tolerance statements.

2.61 The department has appointed a Risk Manager for the program. The Risk Manager is responsible for: assisting the Program Manager in the management of risks and issues; updating and maintaining the program risks and issues register; and developing program monthly reports, detailed risk reports, and risk summary reports. The Risk Manager provides support and guidance to program staff regarding the risk and issue management process. The Risk Manager also works with the Digital Results Office, Delivery Leads and Delivery Managers to ‘ensure risks and issues are actively managed and routinely reported’.

Risk management

2.62 The department’s Enterprise Risk Framework and the program’s Risk Management Strategy define risk as ‘The effect of uncertainty on objectives.’ They explain that ‘An effect can be positive, negative or both, and can address, create or result in opportunities or threats.’

2.63 The Risk Management Strategy outlines the program’s processes for assessing, treating, escalating and reporting risks. It defines three categories of risk for the program:

- program risks: ‘those which are likely to impact on the program objectives, realisation of benefits, and any individual risks at the initiative level that, if realised, will have a broader impact’;

- initiative level risks: ‘those that will have a life no longer than a quarter and are likely to impact on the initiative’s delivery commitments and Objective and Key Results’; and

- sprint41 risks: ‘those risks which are manageable within the sprint and likely to impact on the initiatives sprint goals’.

2.64 The Risk Management Strategy outlines the process for identifying, analysing, evaluating, and treating risks. It details how risks should be communicated and escalated, explaining that:

Staff at all levels must obtain appropriate and regular information about the management of risks within their area of accountability and control. Effective communication is critical to the identification of new and emerging risks and issues as well as understanding changes to existing risks. Appropriate and effective communication, recording and reporting of risk, facilitates effective risk-based decision-making.

2.65 Risks are recorded in Azure DevOps. As at February 2024, the program has documented 899 risks (627 closed and 272 open) in DevOps. Risks recorded in Azure DevOps are assigned an ID number. Each risk entry includes a risk title; description of the consequence and risk source; assessment of the current risk rating; assessment of the residual risk rating; description of controls (identifying each control’s owner); an assessment of each control’s effectiveness; and treatment decisions.

2.66 Of the 72 open risks at the ‘treat’ stage that are listed on the program’s risk register:

- 72 (100 per cent) have assessed the current risk rating;

- 59 (82 per cent) have assessed the residual risk rating;

- 41 (57 per cent) have identified a risk owner;

- 56 (78 per cent) have included at least one control;

- 43 (60 per cent) have assessed at least the first control’s effectiveness; and

- 53 (74 per cent) have documented a treatment decision.

Issue management

2.67 The Risk Management Strategy defines an issue as ‘an event that has occurred and is impacting Service Line and/or program objectives, scope, schedule, budget, quality and realisation of benefits’. It explains that ‘issues often constitute the realisation of identified risks’.

2.68 The Risk Management Strategy outlines the program’s processes for capturing, examining, treating and monitoring issues. Issues are recorded in Azure DevOps. As at February 2024, there were 551 issues (402 closed and 149 open) in DevOps. Issues recorded in Azure DevOps are assigned an ID number. Each issue entry includes an issue title, description, issue owner, ‘assigned to’, treatment options, and resolution.

2.69 Of the 149 open issues that were listed on the program’s issue register:

- 104 (70 per cent) have included a description of the issue;

- 37 (25 per cent) have identified the issue owner;

- 36 (24 per cent) have included treatment option(s); and

- 40 (27 per cent) have documented a resolution.

Risk management plan

2.70 In May 2023, the program established a Risk Management Plan, which was approved by the Head of Digital Trade Strategy and Initiatives. The Risk Management Strategy states that the Risk Management Plan ‘details the strategic risks for the program and the mitigations the program will employ to manage them’.

2.71 The Risk Management Plan documents the risk ID number, title, risk owner, risk manager and the category of risk. It assesses the current and post-treatment likelihood, consequence and risk rating. It details the risk sources, risk statement and consequences if the risk is realised. It lists the controls and control owners as well as assessing each control’s effectiveness. It also lists treatments, treatment owners and treatment due dates.

2.72 The Risk Management Plan and the program’s approach to risk management was presented to the department’s Audit and Risk Committee in September 2023.

Oversight of risks and issues

2.73 The Risk Management Strategy states that the program’s risks and issues will be managed by four governance levels: delivery managers and delivery leads (for medium to low risks, unless it impacts the program); the Program Delivery Meeting (PDM) (for initiative risks above medium); the Executive Delivery Group (EDG) (for severe and high risks); and the SRO (for severe and enterprise-level risks) ‘based on the risk rating and the risk/control owner’s delegation’.

2.74 The Risk Management Strategy states that the PDM is the ‘forum for risks and issues to be escalated within the program’. The PDM considers risks at its meetings, primarily through the Sprint Reports. The Sprint Reports identify initiative risks and issues. The PDM has a standing agenda item for program issues for all of its meetings. The PDM had a standing agenda item for program risks, which ceased from November 2022.

2.75 The EDG considers risks and issues at its meetings, primarily through the Program Status Reports (for more information about Program Status Reports, see paragraphs 4.68 to 4.71). The Program Status Reports list the program risks and issues, the risk ID number, rating and provides an update on the status of the risk.

2.76 As at November 2023, there was one open program risk with ‘treat’ status and a residual risk rating of high listed on the program’s risk register. This risk had been raised with the PDM and EDG and is included in the Risk Management Plan.

2.77 As at November 2023, of the 31 open program risks at the ‘treat’ stage that were listed on the program’s risk register with a residual risk rating of medium or higher, 18 (58 per cent) had been raised with the PDM, EDG or included in the Risk Management Plan. Examples of the 13 risks (42 per cent) that had not been raised include:

- key program decisions may not be made in a timely manner or without appropriate authority;

- the program may not maintain continuity of corporate knowledge and intellectual property;

- program incurs significant underspend against budgeted operational and capital expenditure; and

- financial records are incomplete (e.g. missing timesheet) and inaccurate (e.g. incorrect charging).

Shared risk

2.78 The department’s Enterprise Risk Framework and the program’s Risk Management Strategy define shared risk as:

A risk which extends beyond a single party which requires shared oversight and management. This may include other Commonwealth departments, State and territory governments, industry, community groups, international trading partners, groups, divisions, or another business area of the department.

2.79 The Risk Management Strategy states that ‘governance and oversight of shared risks will be dependent on internal and external stakeholders’. It explains that ‘staff should aim to utilise existing forums such as interdepartmental committees, portfolio committees or program governance boards to discuss, monitor and report on shared risks where appropriate’.

2.80 Of the 11 risks listed in the Risk Management Plan, no risks are classified as shared risks. Of the 80 open program risks at the ‘treat’ stage listed on the program’s risk register, no risks are classified as shared risks.

2.81 The digital reform of agricultural export systems involves and impacts the Australian export industry as well as other Commonwealth departments and agencies, especially those involved in the regulation of exports42 and international trade.43 The department’s Enterprise Risk Framework and the program’s Risk Management Strategy require it to identify and manage program risks that extend beyond the department and require shared oversight and management.

Recommendation no.2

2.82 The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry identify and manage program risks that extend beyond the department and require shared oversight and management.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry response: Agreed.

2.83 The department updated its enterprise risk management framework in late 2022, including guidance policies and tools to ensure alignment with the Commonwealth’s risk management framework. The department will apply these processes to identify and document program risks that extend beyond the department, including analyses and treatment, and ensure there is appropriate governance to share the oversight and management of these risks for the program.

3. Implementation

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (the department) is effectively implementing the digital reform of agricultural export systems (the program).

Conclusion

The department’s implementation of the program is partly effective. The department established a Tranche 1 implementation plan that did not specify an end-state for Tranche 1. In March 2024, the department advised the ANAO that, of the 35 initiatives in Tranche 1, six (17 per cent) had been delivered and 13 (37 per cent) had been partially delivered. In November 2022, the Executive Board agreed to spending reductions across the department to address a forecast departmental overspend. In December 2022 and March 2023, the program’s budget was reduced to support the department’s efforts to reduce spending. This resulted in the program stopping planned work, pausing the implementation of initiatives and reducing contractor staffing. The department established consultation and communication arrangements for the program.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation for the department to establish end-states for program tranches prior to tranche implementation.

The ANAO identified an opportunity for the department to improve the coordination of the program’s stakeholder engagement and communications activities.

3.1 The Australian Government has committed $349.6 million for the Digital Services to Take Farmers to Market budget measure over six years (2020–21 to 2025–26) for the department to deliver the digital reform of Australia’s agricultural export systems outlined in the program’s business cases.

3.2 The Commonwealth Digital and ICT44 Oversight Framework (IOF) and Commonwealth Investment Framework include the following key elements that support the government to manage digital and ICT-enabled investments:

- detailed planning of what will be delivered, the delivery schedule and how each digital and ICT option could be acquired and delivered to deliver capability and benefits45;

- detailed cost estimates based on rigorous planning of required ICT infrastructure, applications and support and then appropriately managing costs (including whole-of-life investment costs) 46; and

- undertaking consultation to ensure effective implementation.47

Is the program being delivered in accordance with implementation plan(s)?

The department established a Tranche 1 implementation plan that did not specify an end-state for Tranche 1. In March 2024, the department advised the ANAO that, of the 35 initiatives in Tranche 1, six (17 per cent) had been delivered; 13 (37 per cent) had been partially delivered; and 16 (46 per cent) had been discontinued, consolidated into other initiatives, or were under development.

3.3 The Business Case Addendum (BCA) included a program roadmap, which listed the initiatives that would be delivered by the program. The roadmap provided an indication of the start and end date for 63 initiatives, mapped across three tranches. Tranche 1 was scheduled from 2020–21 to 2022–23 and listed 31 initiatives that would commence in Tranche 1 (with 28 to be completed in Tranche 1 and three to be completed in Tranche 2).

3.4 In February 2022, the second mid-stage Gateway Review found that the program’s implementation planning documents were not linked:

It is not clear how the initiatives in the Tranche 1 program roadmap link with the items in the 12 months rolling plan and Quarterly Horizon plans. There must be a line of sight across these plans to provide assurance that these initiatives are being delivered.

3.5 The Gateway Review recommended that ‘as a priority the program should link the key program plans so that they can be rolled up based on a supportable level of detail’.

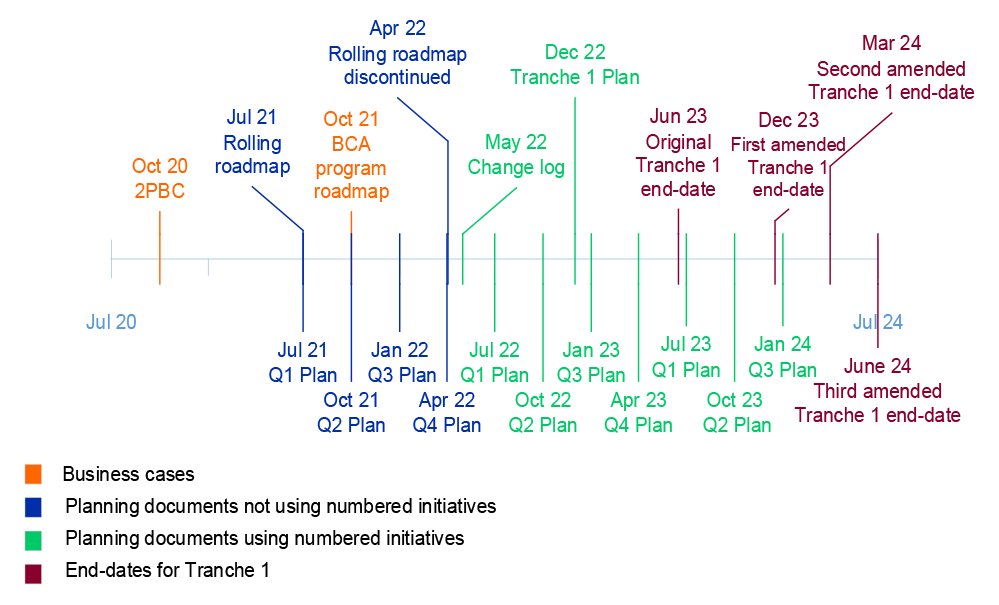

3.6 In May 2022, the program established a Tranche 1 Change Log. The Change Log assigned a number to each of the 31 Tranche 1 initiatives. The Tranche 1 Change Log was used to track changes to initiative titles and initiatives that had been consolidated, added or removed. Figure 3.1 shows the shift to the use of numbered initiatives in planning documents. The initiative numbers were used to identify and link initiatives across planning documents, such as quarterly plans and the Tranche 1 Plan. As at March 2024, the Tranche 1 Change Log listed 35 initiatives.

3.7 In February 2023, the third mid-stage Gateway Review stated that its recommendation had been fully addressed.

Figure 3.1: Timeline of program planning documents

Source: ANAO visualisation of departmental documents.

Quarterly plans

3.8 In July 2021, the Trade Reform Board (TRB) approved the first quarterly plan for the program, for Q1 2021–22. The program prepared quarterly plans for each quarter, from July 2021 to January 2024. The format of the quarterly plans changed each quarter between Q1 2021–22 and Q2 2022–23, after which the format stabilised for three quarters before the format of the quarterly plan changed. The format stabilised for Q1 2023–24 to Q3 2023–24.

3.9 For the three quarters from Q2 2022–23 to Q4 2022–23, each delivery team provided a one-page outline of the work that was anticipated to be delivered in that quarter. The outline of work identified the initiative number; listed the product manager and delivery manager; the Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) for the quarter; key dependencies; key risks; subject matter expertise (SME) requirements; ‘commodity and change impacts’; and relevant program milestones from the Tranche 1 Plan.

3.10 For the three quarters from Q1 2023–24 to Q3 2023–24, each delivery team provided a two or three-page outline of the work that was anticipated to be delivered that quarter. The outline of work identified the initiative number; listed the product manager and delivery manager; identified a quarterly objective; mapped a sprint plan; listed features the initiative would deliver; and listed key dependencies, key issues and risks.

3.11 For Q3 and Q4 2021–22, the quarterly plans established ‘Key commitments’ for the program for the quarter. From Q1 2022–23 to Q4 2022–23, the quarterly plans established ‘key milestones’ for initiatives. From Q1 2023–24, the quarterly plans established ‘features’ for initiatives.

Rolling roadmaps

3.12 The Q1 2021–22 and Q2 2021–22 quarterly plans included a ‘rolling 12-month view of the roadmap across our product teams’. It listed the capabilities or opportunities that ‘will be explored in the quarter’. The rolling roadmap noted that it would be ‘reviewed and iterated regularly and items in later quarters are likely to change’. The rolling roadmap was discontinued from April 2022 in response to work to address the second mid-stage Gateway Review (February 2022) recommendation (see paragraphs 3.4 to 3.7).

Tranche 1 Plan

3.13 In December 2022, the first Tranche 1 Plan for the program was presented to the TRB for approval. The Tranche 1 Plan states that it ‘provides a view on the scope and timeframes for delivery of Tranche 1’ for the program. The Tranche 1 Plan was updated in January 2023 and March 2023.

3.14 The Tranche 1 plans include a roadmap and ‘initiative one-pagers’. The roadmap shows the start and end dates of the initiatives across Tranches 1 and 2. The initiative one-pagers list the initiative number and name; initiative description; benefits; ‘user stories’; ‘definition of done’; initiative dependencies; and key milestones. The plan also lists the team leading delivery of the initiative and the product owner.

Tranche 1 end-state

3.15 The Tranche 1 plans include a section titled ‘definition of done/success criteria’ for each initiative, which outlines the end-state for the initiative. This was generally in the form of a list of capabilities that will be delivered by the initiative (e.g. users will be able to …; capability will be delivered when …; users can …).

3.16 In February 2023, the third mid-stage Gateway Review noted that ‘there isn’t a clear end-state for Tranche 1 and the program will need to take available budget into account when confirming what the end state is’. It recommended that the program ‘clarify and communicate end state for Tranche 1’.

3.17 In May 2023, the Executive Delivery Group (EDG) was advised that, in response to the recommendation, ‘Tranche 1 reconciliation with a clear definition of the end state will be undertaken at the completion of Tranche 1’, with an expected completion date of 31 December 2023. As at March 2024, the program had not established a Tranche 1 reconciliation with a clear definition of end-state.

3.18 In April 2024, the fourth mid-stage Gateway Review stated that its recommendation had been fully addressed:

The Tranche 1 Plan provides key milestones for delivery, and this was communicated. The program should keep Central Agencies and Government updated.

3.19 The fourth mid-stage Gateway Review made recommendations that the department ‘develop an integrated master schedule for the program’ and ‘re-confirm with business the definitions of done for the remaining Tranche 1 elements for endorsement by the EDG’.

3.20 Establishing an end-state for a package of work after its conclusion limits effective oversight and accountability. The department did not establish an end-state for Tranche 1 or document how its completion was anticipated to contribute to the delivery of the outcomes the program is committed to deliver prior to its original end-date of June 2023, or its amended end dates of December 2023 and March 2024.

Recommendation no.3

3.21 The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry establish end-states for program tranches prior to tranche implementation.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry response: Agreed.