Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Diagnostic Imaging Reforms

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Health's implementation of the Diagnostic Imaging Review Reform Package, some three years into the five year reform period.

Summary

Introduction

1. Diagnostic imaging supports the diagnosis of a wide range of medical conditions, from musculoskeletal injuries to cancer. It requires specialised machinery such as ultrasound, X-ray, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and gamma cameras, and the professional input of a radiologist or other medical specialist to interpret the generated images. Some 15 per cent of all Medicare1 outlays in 2014–15, approximately $3.1 billion, are related to diagnostic imaging services.

2. Expenses for Medicare benefits, including diagnostic imaging services, continue to increase in real terms driven by higher demand for increasingly expensive health services and a growing and ageing population. Medicare outlays on diagnostic imaging services have grown at an annual average rate of nine per cent between 1984–85 and 2013–14, increasing from $225 million to $2.9 billion during this time.2 Against this background, successive governments have sought to maintain the sustainability of Medicare in the face of rising costs and demand for medical services.3

3. The Diagnostic Imaging Review Reform Package (the reform package), a 2011–12 Budget measure, was introduced to help improve the overall sustainability of Medicare by reforming key aspects of government-funded diagnostic imaging following two detailed funding reviews. The five year reform package, to be implemented between 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2016, focussed on achieving six objectives for diagnostic imaging services funded through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS)4:

- patients’ access to affordable and convenient diagnostic imaging services be maintained;

- patients in rural and remote areas have continued access to quality diagnostic imaging services;

- requesting practitioners and imaging services communicate effectively to ensure that patients receive appropriate imaging;

- each diagnostic imaging service reflects best clinical practice, is performed by an appropriately qualified practitioner and is provided within a facility which meets all necessary accreditation standards, minimising exposure to unnecessary radiation;

- ongoing Government expenditure for diagnostic imaging services is sustainable; and

- the diagnostic imaging sector is sustainable.5

4. The key elements of the reform package are to:

- expand patient access to MRI through a number of measures, including an increase in the number of MBS-eligible MRI machines;

- improve the requesting practices of medical practitioners of diagnostic imaging services – known as ‘appropriate requesting’;

- address fee relativities and incentives by restructuring the Diagnostic Imaging Services Table (DIST)6 to align with current clinical practice and review MBS fees for diagnostic imaging services so that they are appropriate and do not provide unintended incentives; and

- enhance the Diagnostic Imaging Accreditation Scheme (DIAS)7 by introducing more stringent quality and safety standards.

5. The reform package included additional funding of $104.4 million over four years from 2011–12 to improve and expand the provision of diagnostic imaging services, including $94.5 million in Medicare funding for MRI expansion initiatives. Initiatives such as ‘appropriate requesting’ were intended to help offset the cost to Medicare of expanding MRI services, following studies showing that some 20 to 50 per cent of diagnostic imaging services are potentially redundant or unnecessary.8 Further, as the cost to Medicare of different types of diagnostic imaging services can vary significantly – an MRI scan is approximately seven times more expensive than an X-ray and 20 per cent more expensive than a CT scan9 – the requesting practices of health professionals can directly affect the cost-effectiveness of patient care.

6. The Department of Health (Health), which is responsible for health policy and program implementation, has primary responsibility within government for implementing the reform package, which also relies for its success on effective consultation with the diagnostic imaging service industry and medical profession, and the take-up of key measures by them.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

7. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Health’s implementation of the Diagnostic Imaging Review Reform Package, some three years into the five year reform period.

8. To conclude on this objective, the ANAO examined the progress and impact of the reform initiatives to date and whether Health has:

- worked effectively with stakeholders, planned for implementation of the reform measures, and monitors and reports on the progress and achievement of the reform package;

- effectively progressed initiatives intended to improve the financial sustainability of Medicare related to diagnostic imaging, in particular improving ‘appropriate requesting’ of imaging services and addressing fee relativities and incentives;

- effectively implemented reforms to enable patient access to affordable and convenient MRI services; and

- enabled diagnostic imaging service quality and safety enhancements by introducing relevant regulations and guidance in a timely manner.

9. The ANAO interviewed Health staff involved in the implementation of the reform package and key stakeholders, considered submissions from stakeholders received via the ANAO’s citizen input portal, and reviewed key reform implementation materials and documents. The ANAO also examined a sample of approved applications for MBS-eligibility of MRI machines and analysed key MBS service and expenditure data related to the diagnostic imaging reform initiatives.

10. The audit did not examine: the administration of related grant programs; the Department of Human Services’ (DHS’) roles and responsibilities in relation to Medicare payment processing and compliance, Health’s conduct of MBS reviews; or the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) application process for listing medical services on the MBS.

11. Relevant to this current audit, the ANAO undertook a performance audit of MRI policy development and implementation in 1999–2000.10 The audit examined the effectiveness and probity of the processes involved in the development and announcement of a 1998 Budget measure regarding MRI expansion, including negotiations with the diagnostic imaging profession, and the registration of eligible providers and equipment for receipt of Medicare payments. That audit found that the anticipated level of control over growth in diagnostic imaging outlays had not been achieved and that the then Department of Health and Aged Care’s management of the probity arrangements surrounding negotiations for the MRI measure was not adequate for the circumstances.11 The current audit has examined whether Health had regard to the lessons learned from the previous MRI expansion process and the ANAO audit report thereon, in the course of further extending access to Medicare for MRI services as part of the current reform package.

Overall conclusion

12. Diagnostic imaging, which includes the use of ultrasound, X-rays, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is used to support the diagnosis of a wide range of medical conditions. The Diagnostic Imaging Review Reform Package (the reform package), a 2011–12 Budget measure to be implemented over five years from 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2016, was intended to achieve multiple objectives, relating to accessibility, quality and financial sustainability, through the implementation of a balanced set of initiatives. Key initiatives included: improved patient access by increasing the number of MBS-eligible MRI machines12; improved ‘appropriate requesting’ by health professionals, to promote the more efficient and effective use of diagnostic imaging services; and regulatory changes to enhance quality and safety for patients. The reform package was also intended to contribute to the financial sustainability of Medicare13, with initiatives such as ‘appropriate requesting’ expected to help offset the cost of MRI expansion.14 The Department of Health (Health) has primary responsibility within government for implementing the reform package, which also relies for its success on effective consultation with the diagnostic imaging service industry and medical profession, and their adoption of key measures.

13. Some three years after the Budget measure was announced, Health’s overall implementation of the diagnostic imaging reform package has had mixed results. There has been an overall improvement in patient access to MRI services, including in regional areas; however, almost three times more MRI machines have been granted MBS-eligibility than originally estimated15, and the cost to Medicare of expanded MRI access is likely to be more than double the original Budget estimate of $94.5 million.16 While the introduction of complementary initiatives forming part of the reform package, such as ‘appropriate requesting’, was intended to help offset the cost of MRI expansion, those initiatives have not been adequately planned17 or substantively implemented and the anticipated benefits have not been realised. As a consequence, the cost impact of MRI expansion has been significantly greater than advised to government, with long-term implications for the Commonwealth Budget.18 In this context, the development of cost estimates for the MRI expansion initiative and the department’s implementation planning for the reform package as a whole, have not been fully effective.

14. In implementing the diagnostic imaging reform package, the expansion of MRI services has been the department’s primary focus to date. Implementation dates were established for the expansion process, providing an impetus which was missing for other elements of the reform package. As discussed, Health has significantly expanded the number of MRI machines eligible to receive MBS payments, improving overall patient access to MRI services.19 While improved patient access is expected to improve health outcomes20, it has been at a substantial cost to the Australian Government, with MRI expenditure growing 30 per cent between 2012–13 and 2013–14. The decision to allow General Practitioners (GPs) to request MRI services as part of the reform package21 has been the biggest driver of growth in MRI expenditure, and increased costs have not been offset by efficiencies expected from the take-up of ‘appropriate requesting’ practices by GPs; a behavioural reform initiative which has proven more difficult to implement than originally expected. Further unanticipated expenditure resulted from almost three times more MRI machines receiving MBS-eligibility under the reform package than originally estimated22, with ongoing budget implications.23

15. Health advised the ANAO that its ability to consult with industry – to develop an accurate estimate of the number of MRI machines likely to achieve MBS-eligibility – had been constrained by the need to avoid disclosing government policy intentions before the 2011–12 Budget. Health relied instead on available information and DHS data on the number of registered MRI machines. While this approach reflected the experience of an earlier MRI expansion process24, the limitations of the estimate became evident soon after the Budget measure was announced. At that time Health received numerous requests from providers seeking information on the eligibility of machines not identified by the department. Health subsequently recommended that the then Minister for Health (the Minister) broaden the eligibility criteria for approving MBS-eligibility25, in the belief that overall demand for MRI services and MBS expenditure would not be affected by making additional machines MBS-eligible. The department’s November 2011 advice contrasted with advice provided to the Minister in February 2011, which had noted that limiting the number of MBS-eligible machines had been an approach adopted to contain growth in Medicare expenditure.

16. Health also undertook a competitive invitation-to-apply process to identify and provide MBS-eligibility to 12 MRI machines in defined areas of need.26 The primary assessment process was not efficient, as it was re-run using an alternative scoring system developed late in the process to replace the original scoring system which was found to have shortcomings. Further, limited information was provided to inform the Minister’s decision-making on short-listed applicants – in particular, which 12 of the 21 machines on the short-list represented best value for money – and the department did not advise the Minister of the legal requirements applying to her in approving the commitment of public money. The department’s experience in administering the earlier MRI expansion process, which had demonstrated shortcomings, suggests that greater care should have been taken in these key aspects of the recent MRI expansion process.

17. The reform package included a commitment to review MBS fees for diagnostic imaging to help direct patients to the most clinically appropriate imaging service and avoid unintended incentives.27 The department has not commenced the review and restructure of MBS diagnostic imaging fees28, and this element of the reform package would benefit from the preparation of a targeted plan of action. Similarly, the department should prepare a plan identifying its proposed strategies and actions to improve the take-up of ‘appropriate requesting’ by health professionals. While Health has facilitated some well-targeted projects to improve ‘appropriate requesting’29, to date no enduring initiatives have been introduced to change, in a lasting way, the current practice of requesting diagnostic imaging services in Australia.

18. The ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at improving the effectiveness of Health’s implementation of remaining initiatives by: assessing progress made to date; developing an overall implementation plan to provide strategic direction and a basis for assessing the realisation of anticipated outcomes and benefits; and preparing targeted plans which identify proposed actions to progress key initiatives not yet implemented, including the review of MBS fees for diagnostic imaging and ‘appropriate requesting’ of diagnostic imaging services. To achieve full implementation of the reform package by 30 June 2016, as announced in the 2011–12 Budget context, will be challenging and will require a strong departmental focus and effective engagement with key stakeholders.

Key findings by chapter

Implementation Planning and Consultation (Chapter 2)

19. In its planning and implementation of the diagnostic imaging reform package, Health consulted widely and generally effectively with relevant stakeholders through the Diagnostic Imaging Review Consultation Committee and the Diagnostic Imaging Advisory Committee. The development of the reform package was also informed by two detailed reviews.30

20. Effective implementation planning requires a structured approach to thinking and communicating in the key areas of: planning; governance; engaging stakeholders; managing risk; monitoring review and evaluation; resource management; and management strategy.31 For long-term projects, strategic implementation plans are commonly prepared to provide structure to the implementation effort, prioritise activity and help maintain momentum. Contrary to advice provided to the Minister, Health did not develop an overall implementation plan, and did not provide its senior executive or Minister with advice on the prioritisation of implementation activity. While milestones were established for the implementation of MRI access initiatives, the department did not identify timeframes or milestones for the implementation of other key initiatives.

21. Some three years into the reform program, some key initiatives, including all those related to expanding MRI access, have been implemented by their due dates. However, significant elements of the reform package remain to be fully implemented, most notably initiatives relating to improving Medicare sustainability, such as ‘appropriate requesting’, which were intended to offset the cost of expanded access to MRI services. Health advised that a key reason for the limited progress on this issue was its complexity and the number of different stakeholders involved; which had made it difficult to identify and implement a solution which is effective and acceptable to all stakeholders.32

22. Following the MRI expansion, there has been a loss of momentum and implementation of the remaining measures is flagging. In these circumstances, the department should assess progress made to date in its implementation of the reform package to inform the development of an overall implementation plan to provide strategic direction going forward.

Enhancing Medicare Sustainability through Diagnostic Imaging Reforms (Chapter 3)

23. Evidence-based initiatives – including the development of clinical guidelines and educational resources to improve ‘appropriate requesting’ of diagnostic imaging services by health professionals – were a key element of the reform package. In particular, revised clinical practices were expected to help reduce the number of unnecessary, harmful or wasteful diagnostic imaging services requested by health professionals, and help offset the cost of improved patient access to diagnostic imaging through expanded access to MRI services.

24. Health has funded and undertaken some well-targeted research projects and trials to improve ‘appropriate requesting’, including funding for the development of guidelines for GP-requesting of MRI services and decision support tools. To date, however, no enduring initiative or group of initiatives has been introduced to change, in a lasting way, the current practice of requesting diagnostic imaging services in Australia. Health advised the ANAO that ‘appropriate requesting’– an initiative requiring take-up and behavioural change by health professionals such as GPs – has proven more difficult to implement than originally expected and may take some years to realise, notwithstanding the adoption of a multi-pronged approach. Given the importance of achieving better results here, the department should prepare a targeted plan identifying its proposed strategies and actions to improve the take-up of ‘appropriate requesting’ by health professionals.

25. The reform package included a commitment to review MBS fees for diagnostic imaging; acknowledging that some fees may not accurately reflect the cost of delivering imaging services. The review was also intended to avoid unintended incentives arising and help ensure that patients are directed to the most clinically appropriate imaging service.33 However, the department has not yet commenced the review and restructure of MBS diagnostic imaging fees, and this element of the reform package would also benefit from the preparation of a targeted plan of action identifying proposed strategies and actions to be undertaken.

Enabling Access to Affordable and Convenient MRI Services (Chapter 4)

26. To date, the MRI components of the reform package have been the department’s primary focus. Key initiatives have included: expanding the number of MRI machines with full or partial MBS-eligibility; standardising the conditions of those MRI machines that were already eligible; allowing GPs to request particular MRI items on the MBS; and providing additional incentives for diagnostic imaging providers to bulk bill for MRI services.

27. Health has implemented each of the MRI expansion initiatives in line with set dates. The total number of MBS-eligible MRI services was 829 000 in 2013–14, an increase of approximately 238 000 services (or 40 per cent) since 2011–12. In addition, the number of MRI machines has grown from amongst the lowest per capita in the OECD to above the OECD average. There has also been significant growth in the provision of services outside capital cities, with the number of MRI machines per capita more than doubling over a three year period. These initiatives have improved overall patient access to convenient MRI services. Further, MRI was made more affordable for patients overall, with the number of bulk billed MRI services almost doubling since 2009–10.34

28. The improvement in access to affordable and convenient MRI services has been achieved at a substantial cost to the Commonwealth Budget, with expenditure between 2011–12 and 2014–15 on these initiatives around twice the amount provided for in Budget estimates. Allowing GPs to request particular MBS-funded MRI services has been the biggest driver of growth in MRI services and expenditure.35 There is little doubt that an additional factor, acknowledged by Health as contributing to the unforeseen increase in expenditure, has been the significant growth in the number of MRI machines; with almost three times more machines approved for MBS-eligibility than originally estimated.

29. Some 125 MRI machines were MBS-eligible before the 2011–12 reform package was announced. The then Government’s decisions on the package were based on a Health estimate that this number would increase by 83 machines, bringing the total to 208 machines by 2014–15. In the event, 349 MRI machines are expected to become fully or partially MBS-eligible by January 2015. The department advised that its ability to consult with industry and develop an accurate estimate had been constrained by the need to avoid disclosing government policy intentions before the 2011–12 Budget36, and it relied instead on available information and DHS data on the number of registered MRI machines.

30. The limitations of the estimate became evident following the Minister’s announcement in the 2011–12 Budget context that 65 MRI machines would gain MBS-eligibility. Health subsequently received numerous requests from providers seeking information on the eligibility of other machines, and advised the Minister that an extra 139 machines would potentially qualify for full or partial MBS-eligibility, in addition to the 65 already announced. In November 2011, Health also recommended that the Minister broaden the eligibility criteria for approving MBS-eligibility37, in the belief that overall demand for MRI services and MBS expenditure would not be affected by making additional machines MBS-eligible. On the basis of this advice, in November 2011 the Minister approved the inclusion of newly identified MRI machines, noting that:

I am very surprised that there can be little/no cost change for such a large extra number of machines. I have approved, based on the assurance that DOFD agree to this cost. I will not approve a future increase if these calculations are wrong.38

31. The department’s November 2011 advice to the Minister contrasted with advice provided to the Minister in February 2011, which had noted that limiting the number of MBS-eligible machines had been an approach adopted to contain growth in Medicare expenditure. Health advised the ANAO during the course of the audit that it considers GP-requestors39 are the key driver for MRI services, but also acknowledged that the availability of additional MRI machines is a factor.

32. As discussed, Health advised the ANAO of the need to avoid signalling government Budget intentions in its development of estimates of MRI machines likely to achieve MBS-eligibility. While this approach reflected the experience of an MRI expansion process conducted in 1998, other aspects of the most recent MRI expansion did not have full regard to an ANAO performance audit of the earlier process40, which highlighted the importance of effective risk management, review of documentation and cross-checking of applications.41 At the planning stage for the recent MRI expansion initiative, a key risk was the development of robust budget estimates; and at the implementation stage, Health’s assessment plan did not identify risks to be managed in the assessment of applications, provide detailed guidance to help assessors determine whether applicants met eligibility criteria, or require cross-checking with other stakeholders on the accuracy of information supplied by applicants.42 The ANAO’s review of a sample of applications indicated that half43 of the planned machines that were approved were not supported by documentation, other than a statutory declaration, demonstrating that applicants had made a financial investment in a planned MRI machine.44

33. In addition, Health undertook a competitive, invitation-to-apply (ITA) process for MBS-eligibility to identify 12 applicants seeking to operate MRI machines in defined areas of need.45 The primary assessment process was not efficient, as it was re-run using an alternative scoring system developed late in the process to replace the original scoring system, which was found to have shortcomings. The ANAO’s review indicated that there was likely to have been little material difference in outcomes from the ITA process arising from the re-run of the primary assessment phase. However, the ANAO’s review of the secondary assessment phase indicated that limited information was provided by Health to the Minister on the 21 short-listed applicants to assist the Minister in selecting 12 machines on value for money grounds. In addition, the basis for the Minister’s selection was not documented. These factors limited the transparency of the decision-making process. Further, the department did not advise the Minister of the legal requirements applying to her in approving commitments of public money. The department’s experience in administering the 1998 MRI expansion process, which had demonstrated shortcomings, suggests that greater care should have been taken in these key aspects of the recent MRI expansion process.

Reforms to Enhance Quality and Safety in Diagnostic Imaging (Chapter 5)

34. To date, parts of two reform initiatives relating to improving quality and safety in diagnostic imaging have been implemented. Amendments to the diagnostic imaging regulations have strengthened minimum qualification requirements for diagnostic radiology46 and guidance has been developed relating to safe dosage levels for CT scans, including for children. However, the department has not established ongoing monitoring and evaluation activities to enable it to demonstrate whether these initiatives have been effective in reducing radiation and other risks.

35. Health has also commenced work on a number of other initiatives, including a review of supervisory requirements for diagnostic imaging, whose successful implementation will depend on the outcomes of stakeholder consultation and Ministerial consideration.47 A key initiative in this category is the implementation of enhancements to the DIAS accreditation approach, which Health has acknowledged was ‘in its infancy and cannot provide robust quality assurance’. At present, the accreditation process does not include risk-based on-site inspections or targeted phone interviews by accreditors to verify whether documented policies and procedures are being implemented by diagnostic imaging practices; and in consequence the current implementation of the DIAS provides only marginally more assurance than a self-assessment process.48 The department could provide additional assurance – on the consistency of accreditation assessments by the three approved accreditors, and the quality of the accreditation process overall – by reviewing and testing a sample of assessments from each accreditor. There is also scope to introduce a quality assurance process focusing on whether accreditors’ decisions are adequately supported by sufficient and appropriate evidence and that evidence is being assessed in a consistent manner.

36. The appropriateness of the existing accreditation approach is currently being discussed by Health and its stakeholders through the DIAS Monitoring and Implementation Committee, and Health has advised the ANAO of its intention that the DIAS accreditation process be strengthened over time. In particular, Health is considering whether on-site visits and a shorter accreditation cycle or mid-term assessments against some standards, such as infection control, is appropriate for the DIAS.

Summary of entity response

37. The proposed audit report issued under section 19 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 was provided to Health. In addition, relevant extracts of the proposed report were provided to the Department of Finance and the former Minister for Health, the Hon Tanya Plibersek MP.

38. A summary of Health’s response to the proposed audit report is below, with the full responses provided by Health and the Department of Finance at Appendix 1.

The Department of Health accepts the two recommendations. As the timeframe for implementation of the full package was 2011–12 to 2015–16, the findings of the report will inform the implementation activities remaining under the package. It is acknowledged that, as recommended in the report, implementation plans for all individual elements of the package, as well as an overall implementation and evaluation plan, would be of value. Consideration of the current Government’s priorities will be part of this process.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.30 |

The ANAO recommends that the Department of Health:

Department of Health’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 3.34 |

The ANAO recommends that the Department of Health develop, as part of its implementation planning, targeted plans which identify proposed strategies and actions to progress key initiatives not yet implemented, including ‘appropriate requesting’ of diagnostic imaging services and the review of MBS fees for diagnostic imaging. Department of Health’s response: Agreed. |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the Diagnostic Imaging Review Reform Package and the role of the Department of Health in its development and implementation. It also provides an outline of the audit objective, criteria and approach.

Background

1.1 Diagnostic imaging supports the diagnosis of a wide range of medical conditions, from musculoskeletal injuries to cancer. It requires specialised equipment, such as ultrasound, X-ray, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and gamma cameras, and the professional input of a radiologist or other medical specialist to interpret the generated images. Some 15 per cent of all Medicare49 outlays in 2014–15, approximately $3.1 billion, are related to diagnostic imaging services.

1.2 Expenses for Medicare benefits, including diagnostic imaging services, continue to increase in real terms driven by higher demand for increasingly expensive health services and a growing and ageing population. Medicare outlays on diagnostic imaging services have grown at an annual average rate of nine per cent between 1984–85 and 2013–14, increasing from $225 million to $2.9 billion during this time.50 Against this background, successive governments have sought to maintain the sustainability of Medicare in the face of rising costs and demand for medical services.51,52 Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS)53 service volumes, expenditure and growth for diagnostic imaging from 2005–06 to 2013–14 are outlined in Appendix 2 (Table A.1).

1.3 The reform package, a 2011–12 Budget measure, was introduced to help improve the overall sustainability of Medicare by reforming key aspects of diagnostic imaging following two detailed reviews, discussed in the following paragraphs.

Review of funding for diagnostic imaging services

1.4 In 2008, a taskforce54 was established to manage expenditure growth and to respond to concerns about the diagnostic imaging industry’s sustainability and the expiry of a previous memorandum of understanding (MoU) between Health and the radiology sector.55 As part of the taskforce’s advice to Government, it indicated that another MoU would not achieve the structural reform in diagnostic imaging considered necessary, and on that basis the then Government commissioned a detailed funding review as part of the 2009–10 Budget.56

1.5 The review of government funding for diagnostic imaging services focused on whether the Government was paying the right amount of support for patients to access quality diagnostic imaging services, and considered whether there was a need for structural changes to the way these services were provided through Medicare.57

1.6 The terms of reference for the funding review also indicated that it would ‘establish fee relativities for the MBS items across and within different diagnostic imaging modalities’.58 The ANAO has not examined the work of the funding review.

1.7 The funding review recognised that there were complex, interrelated issues beyond the funding arrangements that needed to be addressed in order to maintain ongoing access to appropriate, quality services for patients and to support the long term sustainability of the diagnostic imaging sector.59

The Diagnostic Imaging Review Reform Package

1.8 In response to the funding review findings, the then Government announced a five year Diagnostic Imaging Review Reform Package (the reform package) in the 2011–12 Budget, to be implemented between 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2016. The reforms are focussed on achieving six objectives for diagnostic imaging services funded through the MBS:

- patients’ access to affordable and convenient diagnostic imaging services be maintained;

- patients in rural and remote areas have continued access to quality diagnostic imaging services;

- requesting practitioners and imaging services communicate effectively to ensure that patients receive appropriate imaging;

- each diagnostic imaging service reflects best clinical practice, is performed by an appropriately qualified practitioner and is provided within a facility which meets all necessary accreditation standards, minimising exposure to unnecessary radiation;

- ongoing Government expenditure for diagnostic imaging services is sustainable; and

- the diagnostic imaging sector is sustainable.60

Reform initiatives

1.9 The key elements of the reform package61 are to:

- expand patient access to MRI through a number of measures, including an increase in the number of MBS-eligible MRI machines;

- improve the requesting practices of medical practitioners of diagnostic imaging services – known as ‘appropriate requesting’;

- address fee relativities and incentives by restructuring the Diagnostic Imaging Services Table (DIST)62 to align with current clinical practice and review MBS fees for diagnostic imaging services so that they are appropriate and do not provide unintended incentives; and

- enhance the Diagnostic Imaging Accreditation Scheme (DIAS)63 by introducing more stringent quality and safety standards.

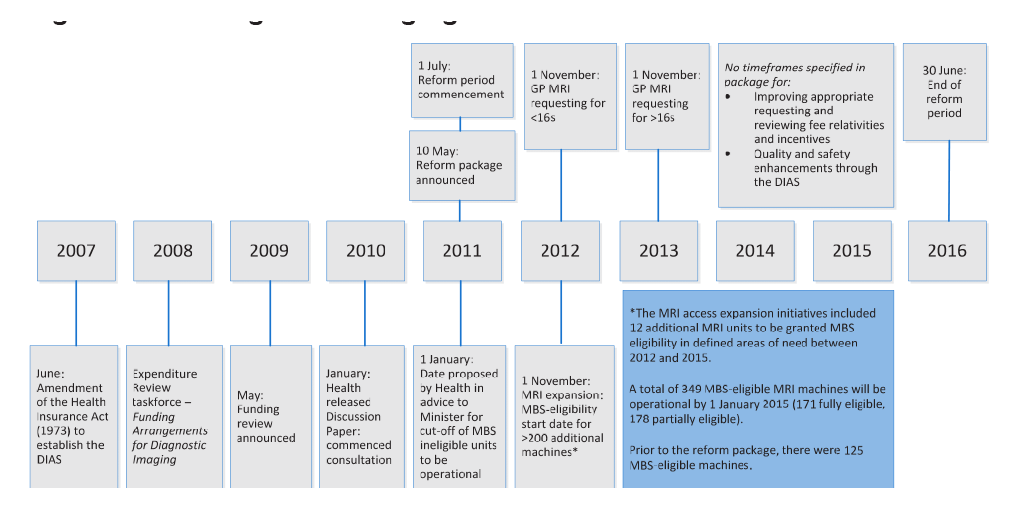

1.10 Key reform implementation dates are outlined at Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Diagnostic imaging reform timeline

Source: ANAO analysis

Funding of diagnostic imaging reforms

1.11 The reform package included additional funding of $104.4 million over four years from 2011–1264 to improve and expand the provision of diagnostic imaging services, including $94.5 million in Medicare funding for MRI expansion initiatives. Initiatives such as ‘appropriate requesting’ were intended to help offset the cost to Medicare of expanding MRI services, following studies showing that some 20 to 50 per cent of services are potentially redundant or unnecessary.65 In addition, Health is funded several million dollars per annum to undertake diagnostic imaging-related policy and program implementation activities, including those related to the reform package as outlined at paragraph 1.14, to consult with industry and provide related policy and regulatory advice to Government.

1.12 Funding from two grant programs has also been used by Health to progress initiatives related to diagnostic imaging reform. The Diagnostic Imaging Quality Program (DIQP) commenced in 2012–1366 and funded more than $3 million worth of projects that have been identified by Health as directly relevant to implementation of reform initiatives.67 Prior to the announcement of the reform package, the National Prescribing Service (NPS) received $9.4 million over four years from 2009 to promote ‘appropriate requesting’ by medical practitioners of diagnostic imaging and pathology services.68

The Department of Health’s role

1.13 Health is responsible for health policy and program implementation, including Medicare–eligible services such as diagnostic imaging. The Department of Human Services (DHS) is responsible for administering Medicare payments on behalf of Health.69

1.14 In relation to the reform package, Health is responsible for ensuring the reforms are implemented, including working directly with the diagnostic imaging service industry and medical profession to:

- encourage more effective use of diagnostic imaging;

- amend regulations and guidelines for the standardisation of operating arrangements for MRI units;

- increase the bulk billing incentives for MRI;

- review the DIST with respect to fee relativities and incentives;

- assess MBS-eligibility for MRI units; and

- facilitate the implementation of the quality and safety enhancements through the DIAS.

ANAO audit coverage

1.15 In 1999–2000, the ANAO undertook an audit of MRI policy development and implementation.70 The audit examined the effectiveness and probity of the processes involved in the development and announcement of the 1998 Budget measure regarding MRI expansion, including negotiation with the diagnostic imaging profession, and the registration of eligible providers and equipment for receipt of Medicare payments. That audit found that the anticipated level of control over growth in diagnostic imaging outlays had not been achieved and that the then Department of Health and Aged Care’s management of the probity arrangements surrounding negotiations for the MRI measure was not adequate for the circumstances.71

1.16 As part of the ANAO’s wider coverage of Human Services’ management of risks to Medicare, in 2013–14 the ANAO undertook a performance audit of Medicare compliance audits, which examined risks related to health professionals’ MBS claiming at the post-payment stage.72

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.17 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Health’s implementation of the Diagnostic Imaging Review Reform Package, some three years into the five year reform period.

1.18 To conclude on this objective, the ANAO examined the progress and impact of the reform initiatives to date and whether Health has:

- worked effectively with stakeholders, planned for implementation of the reform measures, and monitors and reports on the progress and achievement of the objectives of the reform package;

- effectively progressed initiatives intended to improve the financial sustainability of Medicare, related to diagnostic imaging, in particular improving ‘appropriate requesting’ of imaging services and addressing fee relativities and incentives;

- effectively implemented reforms to enable patient access to affordable and convenient MRI services; and

- enabled diagnostic imaging service quality and safety enhancements by introducing relevant regulations and guidance in a timely manner.

1.19 The ANAO interviewed Health staff involved in the implementation of the reform package and key stakeholders, considered submissions from stakeholders received via the ANAO’s citizen input portal, and reviewed key reform implementation materials and documents. The ANAO also examined a sample of approved applications for MBS-eligibility of MRI machines and analysed key MBS service and expenditure data related to the diagnostic imaging reform initiatives.

1.20 The audit scope did not include an examination of: the administration of related grant programs (including DIQP); DHS’ roles and responsibilities in relation to Medicare payment processing and compliance, Health’s conduct of MBS reviews; or the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC)73 application process for listing of medical services on the MBS.

1.21 The audit was conducted74 in accordance with ANAO audit standards at an approximate cost to the ANAO of $503 338.

Figure 1.2: ANAO visit to a diagnostic imaging facility

Source: ANAO fieldwork – audit team’s visit to the Canberra Imaging Group’s Deakin site, with CT machine shown, August 2014.

Report structure

1.22 The report structure is set out in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Chapter Overview |

|

Chapter 2–Implementation Planning and Consultation |

This chapter examines Health’s implementation planning, and the effectiveness and probity of the department’s consultation with stakeholders during the reform review and subsequent implementation. |

|

Chapter 3–Enhancing Medicare Sustainability through Diagnostic Imaging Reforms |

This chapter examines the status and progress of Health’s implementation of the reform initiatives that aim to improve the sustainability of Australian Government expenditure for diagnostic imaging services. |

|

Chapter 4–Enabling Access to Affordable and Convenient MRI Services |

This chapter examines the extent to which Health has effectively implemented reforms to enable access to affordable and convenient MRI services. |

|

Chapter 5–Reforms to Enhance Quality and Safety in Diagnostic Imaging |

This chapter examines the status and progress of Health’s implementation of the reform initiatives that aim to enhance quality and safety in diagnostic imaging, in particular through the Diagnostic Imaging Accreditation Scheme (DIAS). |

2. Implementation Planning and Consultation

This chapter examines Health’s implementation planning and the effectiveness and probity of the department’s consultation with stakeholders during the reform review and subsequent implementation.

2.1 Effective stakeholder consultation and implementation planning are key enablers for achieving the diagnostic imaging reform objectives. Health advised the then Minister for Health (the Minister) that the reform package would be implemented in close consultation with the diagnostic imaging sector.

2.2 The ANAO examined the effectiveness of Health’s:

- stakeholder consultation process, including probity arrangements adopted as part of that process; and

- implementation planning process, including monitoring, evaluation and reporting, and advice to Government.

Stakeholder consultation

2.3 Appropriate levels of openness, transparency and integrity are required to provide stakeholders with confidence in public sector decision-making processes and actions. Openness and transparency involve meaningful consultation with stakeholders and the consistent communication of reliable information, having regard to charter responsibilities, privacy obligations and other legal and policy requirements.75

2.4 In determining the extent to which stakeholders were informed of the reform measures and their advice considered in implementation decisions, the audit examined Health’s arrangements and processes for consulting with stakeholders. The audit also considered probity arrangements adopted as part of the consultation process.76 This was important given the issues identified in relation to consultation with stakeholders over previous diagnostic imaging Budget measures, where probity was found not to be adequate in the circumstances.77

Consultation during the funding review

2.5 The reform package was developed in consultation with industry, the medical profession and consumer stakeholders, through five meetings of the Diagnostic Imaging Review Consultation Committee (DIRCC).78 The DIRCC was convened by Health in December 2009 following the 2009–10 Budget announcement of a detailed funding review of diagnostic imaging. Health considered that input from diagnostic imaging stakeholders was necessary to fully inform the review process of relevant issues for providers, requesters and consumers of diagnostic imaging.79 Following the release of a public discussion paper in January 2010, DIRCC meetings were held between March 2010 and May 2011. The last meeting was held on 13 May 2011 to inform stakeholders of the reform package announced in the 2011–12 Budget.80

2.6 To provide an evidence base for the diagnostic imaging funding review, Health drew on analysis of Medicare data, peer-reviewed scientific research and industry input and analysis. The funding review identified, with the support of stakeholders, that there were complex, interrelated issues beyond funding arrangements that needed to be addressed in order to maintain ongoing access to appropriate, quality services for patients and to support the long-term sustainability of the sector.

Consultation during implementation of the reform package

2.7 Following the finalisation of the funding review and announcement of the reform package, Health convened the Diagnostic Imaging Advisory Committee (DIAC)81 to ‘provide assistance to the Government on the implementation of the Diagnostic Imaging Reform Package and issues relating to diagnostic imaging and the diagnostic imaging sector’.82 The first DIAC meeting was held in December 2012 and a total of five meetings have been held to September 2014.

2.8 Matters that have been considered by DIAC include: examining radiation exposure to children from CT, ‘appropriate requesting’ and decision support tools, quality in diagnostic imaging, supervision of services, and capital sensitivity.83 Health has used the DIAC to inform its development of diagnostic imaging policy and as a forum for committee members to share perspectives and information on complex subject matter. Health also engages regularly with relevant stakeholders, through other forums84, on implementation of key elements of the package. While Health has established a range of consultative mechanisms, it advised the ANAO that progressing issues relating to diagnostic imaging has often been challenging and time consuming due to their complexity.

2.9 Stakeholders consulted during the course of the audit acknowledged Health’s efforts to effectively consult and engage on issues related to diagnostic imaging in both the funding review and reform implementation phases. However, a common concern expressed by several stakeholders involved in the reforms was that Health’s focus has been predominantly on the MRI expansion. Stakeholders indicated that, while the increased access to MRI services is an important improvement in access for patients, other equally important reform initiatives have not received appropriate attention. Health has acknowledged the substantial resources devoted to the MRI expansion, and noted that the process was more time consuming and resource intensive than anticipated. Health has further acknowledged that having specific timeframes for MRI-related implementation helped focus departmental attention on those reform elements.85

Probity arrangements

2.10 When consulting and negotiating with industry participants who may gain knowledge or insights that could benefit them materially, it is important that adequate probity arrangements are implemented. The audit considered whether arrangements to adequately preserve confidentiality and manage potential conflicts of interest were implemented in relation to the reforms.

2.11 The ANAO found that in establishing the DIRCC and DIAC, Health used departmental templates to obtain deeds of undertaking in relation to confidentiality of information and conflicts of interest from all committee members, and declarations of conflicts of interest were submitted by all members when appointed. Committee meeting minutes show that declarations of conflicts of interest were also sought verbally before the commencement of each committee meeting.86

2.12 The management of specific probity issues relating to the expansion of MRI services is discussed in Chapter 4 of this report.

Implementation planning, monitoring and reporting

Implementation planning

2.13 Effective implementation planning is a critical factor contributing to an entity’s ability to successfully prepare for the delivery of intended policy outcomes. Planning for successful implementation involves getting the implementation strategy, plan and design right before beginning time-critical and expensive implementation activities. Planning provides a ‘map’ of how an initiative will be implemented, addressing matters such as timeframe, dependencies with other policies or activities, phases of implementation, roles and responsibilities and resourcing.87 It is desirable that risk identification and treatment as well as arrangements for regular monitoring and review of key implementation deliverables be established as early as possible, preferably during the policy design and implementation planning phase.

Progress with implementation

2.14 Some three years into the reform period, Health has implemented a number of reform initiatives in line with the publicly announced timeframes, most notably those associated with improving MRI access. Other reform initiatives did not have publicly announced timeframes for implementation. To date, the department has:

- progressed some of the quality and safety initiatives outlined in the funding review, including strengthening qualification requirements for providers of some diagnostic imaging types;

- reviewed diagnostic imaging regulations and identified potential changes that are currently being assessed; and

- funded projects and trials that will inform the department’s approach to improving ‘appropriate requesting’ of diagnostic imaging services.

2.15 However, a number of important reform initiatives have not yet been implemented. These include: addressing fee relativities and incentives, and implementing effective arrangements to improve ‘appropriate requesting’ of diagnostic imaging services. Efforts to improve ‘appropriate requesting’ were intended to contribute to the financial sustainability of MBS expenditure and help offset the cost of the MRI expansion measures. Establishing appropriate fee relativities and incentives across different types of diagnostic imaging services was a task that the funding review was originally intended to achieve, however this was deferred to be implemented as part of the reform package. While this task was considered a priority by the then Government, no meaningful progress has been achieved some five years later.88 During this audit, Health advised the ANAO that the current government is also seeking to address the overall financial sustainability of Medicare through its 2014–15 Budget measure relating to patient co-payments, and that the delay to date in implementing that measure has impacted on the department’s ability to resolve issues in the diagnostic imaging sector in a way that the sector considers satisfactory.

Implementation planning

2.16 For each initiative that has been implemented to date, Health has developed and been guided by various annual team work plans, assessment plans and consultation with stakeholders. In some cases, risks and mitigation strategies have been identified. In addition, an initial implementation approach was provided to the Minister in December 2011. This identified that in addition to the MRI reforms, the remaining reform elements were to be delivered in a phased manner in close cooperation with the diagnostic imaging sector over the following five years. Health also advised the Minister that a more detailed implementation approach would be developed and that the Minister would be kept informed of its development.

2.17 To date, however, Health has not developed an overall implementation plan for the reform package as a whole that assesses risks, specifies timeframes, resources, proposed approaches and performance indicators for all reform initiatives. Further, in the absence of an overall implementation plan, the department has not provided advice to its executive or the Minister on the prioritisation of implementation activities over the five year reform period.

2.18 Health has not yet identified timeframes or milestones that will be achieved, either within the five year reform period or beyond, for implementation of the remaining key reform initiatives. Following the implementation of initiatives to expand access to MRI services, the ANAO has observed that there has been a loss of momentum for the reform process, and implementation of the remaining measures is flagging. The development of a five-year implementation plan covering each aspect of the reform package would have provided structure to the implementation effort, prioritised activity and helped maintain momentum for the package as a whole. Effective departmental planning would have been of particular benefit for reform initiatives that did not have publicly specified timeframes.

Monitoring, evaluation and reporting

2.19 Implementation, to be successful, requires ongoing and active management. Active management – informed by well-designed monitoring, review and evaluation activity – enables entities to ensure that adequate resources continue to be available and commensurate with the scope, risk and sensitivity of the implementation. It also enables entity leadership and ministers to assess implementation progress, identify and address problems and review the ongoing relevance and priority of the initiative.89

Monitoring and evaluation

2.20 In its 2011 advice to the Minister that led to the 2011–12 Budget decisions on the reform package, Health outlined the desired outcomes to be achieved within five years and the proposed monitoring and performance review arrangements for several proposed reform elements. In particular, although specific targets and performance indicators were not publicly identified for the reform package, Health advised the Minister that it would monitor the initiatives for improved patient access to MRI services and the development of clinical guidelines for general practitioners (GPs), on an ongoing basis through in-depth analysis of Medicare data and by working closely with stakeholders. In addition, Health advised the Minister that it would review arrangements for MRI access after three years from implementation to determine whether patient access and affordability problems had been addressed. More generally, in its 2013 Portfolio Budget Statement, Health indicated that it would:

Continue to monitor and evaluate the impact of the changes introduced on 1 November 2012, which require those performing the actual diagnostic imaging procedure to hold minimum qualifications for all MBS-funded X-ray, angiography and fluoroscopy (diagnostic radiology) services, addressing quality and safety concerns that arose from the funding review.90

2.21 Health has scheduled a review of the impact of MRI access reforms to be undertaken in 2014–15. However, this review has not yet commenced and ongoing monitoring of reform initiatives, as advised to the Minister, has not occurred. The intended monitoring and evaluation of the impact of the changes introduced on 1 November 2012, in relation to the qualifications of practitioners providing diagnostic radiology services, is in its early stages.91

2.22 In common with the department’s approach to overall implementation planning, there has not to date been a structured approach to monitoring and evaluating progress against intended objectives for the reform package as a whole.

2.23 The diagnostic imaging reform package was intended to achieve multiple objectives, relating to accessibility, quality and financial sustainability, through the implementation of a balanced set of initiatives. Given these objectives for the reform package, Health should assess progress made to date in its implementation of the reform package, to inform the preparation of an overall implementation plan providing strategic future direction.

Reporting

2.24 Maintaining accountability through clear reporting on performance and operations is a critical factor in building and retaining the trust of the government and community. Timely and transparent public reporting on expenditure, activities and outcomes allows parliamentarians and members of the public to scrutinise and to make informed judgements about the performance and contributions of public sector entities.92

2.25 As discussed, Health did not develop an implementation plan for the reform package as a whole. Similarly, the department did not implement a structured approach to reporting on progress and impact over the life of the initiative. Health advised the ANAO that the department does not undertake regular, structured risk or performance reporting to the department’s senior executive, including in relation to the diagnostic imaging reform package. Rather, reporting occurs as considered appropriate and relevant at a point in time on a particular issue.

2.26 Reporting to Health’s senior executive and successive Ministers has occurred when Health has required a decision to be made, in preparation for briefings with stakeholders, or in response to a direct ministerial request for information. To date, advice to the senior executive and Ministers has predominantly focussed on the activities associated with the initiatives to improve MRI access.

2.27 Public reporting in relation to some of the reform initiatives has occurred in Health’s annual report against KPIs in portfolio budget statements. Information has been provided on activities undertaken in relation to granting MBS-eligibility for MRI machines, the number of sets of symptoms for which GPs have MRI requesting rights, and strengthening minimum requirements for practitioners delivering diagnostic radiology services (discussed above). While these are key elements of the reform package, Health has not yet reported on the outcomes of the reform package as a whole. Further, there is a lack of specific targets and performance indicators for the various initiatives, to assess outcomes and benefits achieved by the package.

2.28 In its public annual reporting, Health has not provided quantitative data and in some cases there have been shortcomings in reporting in relation to individual reform initiatives, such as the impact of introducing GP-requested MRI items. Health reported in its 2013–14 annual report that since increasing access to MRI services for primary care patients, MBS data has shown ‘a steady rise in services’.93 The ANAO found, however, that following the introduction of GP-requesting rights for MRI scans for patients aged 16 years and over, the number of MRI services increased by 30 per cent; a sharp increase rather than the steady rise reported by the department. The graph at Figure 2.1 shows the impact of the MRI access initiatives, noting in particular the steep rise in total MRI services since GP-requesting rights for MRI services were introduced in November 2013 for patients over 16 years.94

Figure 2.1: MRI services and expenditure requested by specialists/ consultant physicians and total, 2009–10 to 2013–14

Source: ANAO analysis from Health and DHS data.

Note: Services and expenditure ‘less GP-requested’ refer to those requests by specialists and consultant physicians.

2.29 With the change of government in September 2013, and its policy focus on the sustainability of Medicare, the audit examined whether the new Government had been advised on the reform measures. Other than a minute to the Minister in November 2013, which briefly listed the elements of the reform package in the context of seeking a decision on the third round of MRI expansion applications, there has been no specific advice provided on the overall progress and impact of the reform package. The preparation of an overall implementation plan would provide a basis for assessing and reporting on the realisation of outcomes and benefits of the reform package.

Recommendation No.1

2.30 The ANAO recommends that the Department of Health:

- assess progress made to date in its implementation of the diagnostic imaging reform package; and

- develop an overall implementation plan to provide strategic direction and a basis for assessing the realisation of anticipated outcomes and benefits.

Department of Health’s response: Agreed.

Conclusion

2.31 In its planning and implementation of the diagnostic imaging reform package, Health consulted widely and generally effectively with relevant stakeholders through the DIRCC and the DIAC. The development of the reform package was also informed by two detailed reviews.95

2.32 Effective implementation planning requires a structured approach to thinking and communicating in the key areas of: planning; governance; engaging stakeholders; managing risk; monitoring review and evaluation; resource management; and management strategy.96 For long-term projects, strategic implementation plans are commonly prepared to provide structure to the implementation effort, prioritise activity and help maintain momentum. Contrary to advice provided to the Minister, Health did not develop an overall implementation plan, and did not provide97 its senior executive or Minister with advice on the prioritisation of implementation activity. While milestones were established for the implementation of MRI access initiatives, the department did not identify timeframes or milestones for the implementation of other key initiatives.

2.33 Some three years into the reform program, some key initiatives, including all those related to expanding MRI access, have been implemented by their due dates. However, significant elements of the reform package remain to be fully implemented, most notably initiatives relating to improving Medicare sustainability, such as ‘appropriate requesting, which were intended to offset the cost of expanded access to MRI services. Health advised that a key reason for the limited progress on this issue was its complexity and the number of different stakeholders involved; which had made it difficult to identify and implement a solution which is effective and acceptable to all stakeholders.98

2.34 Following the MRI expansion, there has been a loss of momentum and implementation of the remaining measures is flagging. In these circumstances, the department should assess progress made to date in its implementation of the reform package to inform the development of an overall implementation plan to provide strategic direction going forward.

3. Enhancing Medicare Sustainability through Diagnostic Imaging Reforms

This chapter examines the status and progress of Health’s implementation of the reform initiatives that aim to improve the sustainability of Australian Government expenditure for diagnostic imaging services.

3.1 Medicare expenditure on diagnostic imaging continues to grow at 9.3 per cent per annum.99 The reform package was designed to address the high rate of growth in diagnostic imaging services and the resultant impact on the Commonwealth Budget and the sustainability of Medicare.

3.2 The reform package included two key initiatives that were intended to directly address the rate of volume growth of diagnostic imaging services. They were:

- improving the requesting practices of medical practitioners of diagnostic imaging services – known as ‘appropriate requesting’; and

- reviewing the fees paid by the Government for diagnostic imaging services, including relativities and incentives and restructuring the DIST to align with current clinical practice.100

3.3 The ANAO examined implementation of the two initiatives, and their effect to date on the rate of growth of diagnostic imaging.

Improving ‘appropriate requesting’

3.4 Requesting appropriate imaging services means that patients are directed to the most clinically appropriate service and that images are of value in diagnosing patient conditions. In addition, it relates to there not being unnecessary, harmful or wasteful services undertaken during the course of caring for a patient. The reform package sought to address these elements, in particular as requesting relates to growth in diagnostic imaging expenditure and patient safety risks, particularly computed tomography (CT) scans for children.

The importance of ‘appropriate requesting’

3.5 International studies have shown that 20 per cent to 50 per cent of diagnostic imaging for a variety of conditions fails to provide information that improves patient diagnosis and treatment and may therefore be considered redundant or unnecessary.101

3.6 In Australia, radiologists deliver over 80 per cent of diagnostic imaging services at the request of other medical practitioners, such as general practitioners (GPs) or specialists.102 GPs request over 65 per cent of diagnostic imaging services, with the rate of imaging tests ordered having increased by 45 per cent over the decade to 2012.103, 104 Nuclear medicine specialists also provide diagnostic imaging services at the request of other medical practitioners.105 In addition, diagnostic imaging is undertaken by medical practitioners at the point-of-care106, without a request from another doctor.

3.7 As part of its reform package, the then Government recognised that there are some areas where diagnostic pathways could be better defined and that there are interacting factors that affect requesting behaviours. These factors include the level of understanding and awareness by medical practitioners of the risks, benefits and suitability of different diagnostic tools in different circumstances. In addition, patient expectations and their understanding of risks, benefits and costs107, as well as access to services and perceived medico-legal risk are relevant. Furthermore, Health and the sector have recognised that financial or other incentives for providers of diagnostic imaging services may lead to preferential requesting or provision of certain types of services over others.108

3.8 In advice to government in the lead-up to the 2009–10 Budget, the interdepartmental expenditure review taskforce109 included an expert consultant’s report that examined funding issues and concluded that any strategy to address long-term expenditure growth on diagnostic services would be incomplete if it did not include measures to address growth in demand driven by requesting practitioners. The report also concluded that there is considerable scope to make better use of electronic decision support tools.

Reform initiatives to improve ‘appropriate requesting’

3.9 The reform package contained the following initiatives to improve ‘appropriate requesting’ of diagnostic imaging:

- [Health] will work with the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and other stakeholder bodies to develop clinical guidelines and educational resources, such as professional development modules to increase GPs’ knowledge of diagnostic imaging, including the risks associated with radiation;

- the development of guidelines and educational resources will support the extension of requesting rights to GPs for a limited range of clinically appropriate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses. These guidelines will also assist GPs when determining the most appropriate imaging modality across CT and MRI; and

- where interventions are effective in reducing the rate of volume growth for imaging, funding may be redirected to allow schedule fee increases for appropriate imaging items.110

3.10 It was recognised at the time that the success of initiatives to improve ‘appropriate requesting’ would rely on the involvement of the diagnostic imaging service industry and medical profession.

Implementation to date

3.11 The reform package did not provide specific timeframes for completion of ‘appropriate requesting’. To date, Health has undertaken a number of activities and funded a number of research projects to support ‘appropriate requesting’ of diagnostic imaging services and to inform future policy. However, Health advised that there has been limited progress in implementing the initiative because of its complexity and the number of different stakeholders, noting that:

Although the stakeholders agreed in principle that there could be more ‘appropriate requesting’, they have diverging perspectives and proposals. This has made it difficult for the department to identify and implement a solution which is effective and acceptable to all stakeholders.111

3.12 Activities undertaken include funding, through the Diagnostic Imaging Quality Programme (DIQP), seven projects related to improved requesting.112 These projects, outlined in Table 3.1, address matters raised in the funding review including educational modules, electronic decision support113, informed consumer consent and examining image ordering by GPs.

Table 3.1: Projects funded under the Diagnostic Imaging Quality Program (DIQP)

|

Organisation |

Project Title |

Funding Provided |

Project Outputs or completion date |

|

RadLogix |

Electronic Decision Support in a GP Practice |

$329 384 |

Completed July 2013 (no web link available) |

|

Australian Society for Ultrasound in Medicine (ASUM) |

Point of Care Ultrasound Qualifications |

$166 969 |

|

|

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR) |

Inside Radiology – Update 2013 |

$294 589 |

|

|

RANZCR |

CT Dose Optimisation |

$196 255 |

http://www.ranzcr.edu.au/quality-a-safety/program/insideradiology |

|

RANZCR |

Educational Modules |

$1 023 587 |

Completion due May 2015 |

|

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) |

Nuchal Translucency Reflections on Effectiveness |

$223 300 |

Completion due late 2014 |

|

QLD Health |

CT Dose optimisation |

$165 000 |

http://www.health.qld.gov.au/hsq/biomedical-tech/ct-optimisation.asp |

|

University of Sydney |

Evaluation of the linear feature extraction algorithm |

$297 410 |

Completion due mid-2016 |

|

University of Sydney |

BEACH – Image Ordering by Australian GPs |

$156 417 |

http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/BItstream/2123/10610/3/9781743324141_ONLINE.pdf |

|

Consumer Health Forum (CHF) |

Diagnostic Imaging and Informed Consumer Consent |

$303 407 |

|

|

WA Health |

Diagnostic Imaging Pathways Consent |

$248 848 |

Completion due late 2014 |

|

Australasian Association of Nuclear Medicine Specialists (AANMS) |

Provision of enhanced information to referrers and patients |

$48 400 |

http://www.anzapnm.org.au/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=40&Itemid=49 |

|

Total |

|

$3 453 566 |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of information provided by Health

3.13 In addition, guidelines developed by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners to support GP-requesting rights for MRI have been funded by the department in the amount of $1.2 million. These guidelines were made available to GPs to support the introduction of the new MBS-supported referral items in November 2013.

3.14 As a result of the taskforce’s advice to government leading up to the 2009–10 Budget114, the National Prescribing Service (NPS)115 was funded $9.4 million over four years (2009–2013) to promote high quality and appropriate requests for diagnostic imaging services and pathology tests.116 The outcomes of this initiative have provided Health with information on the impact of interventions to improve ‘appropriate requesting’ for diagnostic services. The NPS project is estimated to have saved $23 million from initiatives undertaken targeting one diagnostic imaging and one pathology MBS item.117 The NPS advised the ANAO that based on its experience, education and awareness-raising campaigns directed at health professionals need to be repeated periodically, approximately every 18 months to two years, otherwise requesting habits may revert to previous levels. There would be benefit in Health considering past experience, in the context of designing and delivering decision support tools, professional educational modules and related actions to improve ‘appropriate requesting’ as part of the reform package.

3.15 In addition to the DIQP-funded projects and other initiatives, Health has commenced planning a review of lower-back imaging. This is in response to growth in services and research that early imaging in the absence of certain risk factors and clinical indications is generally not the most appropriate diagnostic and treatment pathway. Findings from this departmental MBS review will be referred to the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) for independent expert advice and a recommendation to the Minister.118 This review may result in changes in MBS item descriptors, changes to MBS fees, new MBS items, and education programs for medical and allied health professionals.

3.16 A related measure identified in the reform package was the review of restrictions limiting imaging substitution and the role of radiologists in appropriate imaging. The current regulations broadly permit a provider of diagnostic imaging services (usually a radiologist) to substitute a service for the one originally requested when it is considered more appropriate for the diagnosis of the patient’s condition and when the provider has consulted with the requesting practitioner, or taken steps to do so.119 The ANAO found that restrictions limiting imaging substitution have not yet been changed, notwithstanding the inclusion of this initiative in the reform package. Health and key stakeholders have advised the ANAO that the current situation works reasonably well, as there is scope for the provider to communicate suggested changes to the requester, and consequently this reform element is considered a lower priority than others not yet implemented.

3.17 Health has advised the ANAO that the MRI guidelines developed for GPs and initiatives undertaken to date are considered a first step and that:

Before making a decision on the best way to improve ‘appropriate requesting’, Health will consider the outcomes of all DIQP projects and related initiatives when remaining projects are completed in 2015. Health has no current intent to mandate the use of any tools and agreement with the diagnostic imaging sector will be sought, through the DIAC120 and possibly broader consultation, on the way forward. As an initial task, the Diagnostic Imaging section has included on its 2014–15 annual team workplan the preparation of an information paper to inform itself of how it will proceed with evaluating DIQP project outcomes.

3.18 Some three years into the reform process however, no enduring initiative or group of initiatives has been introduced to change, in a lasting way, the current practice of requesting diagnostic imaging services in Australia. The continued high growth rate in diagnostic imaging service expenditure over the last three years (discussed in paragraph 3.1) confirms this. The growth in MRI expenditure of 30 per cent between 2012–13 and 2013–14121, which arose particularly as a result of changes to GP-requesting rights, reinforces the benefits, identified in the context of developing the reform package, of improving ‘appropriate requesting’ of higher-value services as a means of managing the rate of expenditure growth.

3.19 Given the importance of achieving better results here, the department should develop, as part of its implementation planning, a targeted plan which identifies proposed strategies and actions to progress ‘appropriate requesting’ of diagnostic imaging services.

Addressing fee relativities and incentives

3.20 The second main reform element aimed at improving the sustainability of Medicare was a review of Medicare fees for diagnostic imaging services and a restructure of the regulations that support those payments.

3.21 The Diagnostic Imaging Services Table (DIST)122 specifies the services that are eligible for MBS rebates, the fees applicable to each item, and rules for interpretation of the table. There are approximately 870 service items currently on the DIST categorised by imaging modality.

The need to address fee relativities and incentives

3.22 Health and stakeholders advised the ANAO that for a number of reasons the MBS fees payable for many items on the DIST do not reflect the current cost of delivering the service. These reasons include: annual indexation of imaging schedule fees not being applied since November 1998123; adjustments made to fees under the capped-volume agreements with the radiology sector prior to 2008; and changes in technology and clinical practice.

3.23 While some services are known by Health and stakeholders to be under-funded in the MBS, there is also recognition that other types of imaging services are over-remunerated and therefore more profitable to imaging providers.124 The risk that remuneration arrangements may provide unintended incentives to invest in higher end technologies was identified in the funding review. An interdepartmental taskforce125 provided advice to the Government on this matter in the lead-up to the 2009–10 Budget, highlighting the potential for providers to invest in more profitable services (such as basic X–ray, CT and some types of ultrasound services with high revenue potential) rather than comprehensive diagnostic imaging practices, which may then result in the contraction of imaging services available to patients.

3.24 Government interest in reviewing MBS fees for diagnostic imaging preceded the reform package. The 2009 terms of reference for the review that led to the diagnostic imaging reform package focused primarily on the funding of diagnostic imaging, with the first task of the review being ‘to establish appropriate fee relativities for MBS items across and within diagnostic imaging modalities’.126 However, MBS fees were not reviewed or adjusted during that review and the task was instead deferred as part of the five-year reform package.