Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Design and Implementation of the Liveable Cities Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and implementation of the Liveable Cities Program, including the assessment and approval of applications.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Liveable Cities Program (LCP) is a competitive, merit-based grant program administered by the Department of Infrastructure and Transport (Infrastructure). A total of $20 million was available under the program over the period 2011–12 to 2012–13. This period was later extended to 2013–14. LCP is part of the Australian Government’s $120 million Sustainable Communities package, released in conjunction with the National Urban Policy.1 The objective of LCP is to improve the planning and design of major cities that are experiencing population growth pressures, and housing and transport affordability cost pressures.

2. LCP funding was available for planning and design projects (stream one) and demonstration construction-projects (stream two). Projects had to be located in one of the 18 major cities2 that were the subject of the National Urban Policy. Local governments operating within those cities, as well as state and territory governments, were eligible to apply.

3. Infrastructure was responsible for receiving the LCP applications and checking that each one complied with the eligibility requirements. The department was then to assess each eligible application against the published assessment criteria and, for high-ranking stream two projects, consider construction viability risks. This assessment was to form the basis for its advice to the Minister for Infrastructure and Transport (the Minister) on the merits of each application and its recommendations as to which applications should be approved for funding.

4. In April 2012, the Minister approved a total of $20 million in grants for 26 projects. Following a reversal of one funding decision by the Minister, and a withdrawal by one successful applicant, Infrastructure was responsible for negotiating agreements for 24 approved LCP projects. By the end of April 2013, agreements had been signed for 22 projects totalling $15.33 million.

Audit objectives and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and implementation of the LCP, including the assessment and approval of applications. The audit criteria reflected the requirements of the grants administration and better practices articulated in the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines and ANAO’s Administration of Grants Better Practice Guide.

Overall conclusion

6. Through the LCP, a total of $20 million in grant funding was awarded to 26 projects located in 14 major cities across all states and territories.3 These included seven infrastructure projects, primarily directed at improving pedestrian and cycling access but which also included the supply of low carbon energy, two residential developments and a rapid bus transit system. The other 19 projects approved were for planning, feasibility assessment and/or design activities that will inform future investment in infrastructure.

7. The distribution of funding in geographic terms and the nature of the demonstration projects provided the desired mix foreshadowed in the program guidelines so as to contribute to achieving the program objective of improving the planning and design of major cities. By the end of April 2013, funding agreements had been signed for the majority of the approved projects, with most of these projects contracted to be delivered by the program’s amended completion date of 30 June 2014.

8. Infrastructure’s management of the design and implementation of LCP was effective in most respects. Of note was that improvements were evident in the merit-assessment approach adopted by the department compared with earlier grant programs audited by ANAO. In particular:

- all eligible applications were assessed against published assessment criteria; and

- the scoring approach adopted enabled the comparison of the relative merits of applications against each criterion and in aggregate.

9. Infrastructure also adopted an improved approach to briefing the Minister on the outcome of the assessment process. The LCP briefing included a clear funding recommendation to the Minister based on the scores awarded against the assessment criteria and in consideration of the program objectives. In addition, a record was kept of the eight instances where the Minister’s decision diverged from the recommendation of the department—three projects not recommended by Infrastructure were approved by the Minister, and five projects recommended by the department were not approved for funding. This approach provides transparency and accountability for the advice given by Infrastructure, and the funding decisions that were subsequently taken.

10. However, there remain opportunities for further improvements to Infrastructure’s grants administration practices. Firstly, there were shortcomings with the assessment of applications in relation to the department’s eligibility checking and aspects of its conduct of the merit-assessment process.4 Secondly, it needs to be recognised that applications that are assessed as not satisfactorily meeting the published merit assessment criteria are most unlikely to represent value for money in the context of the program objectives.

11. In addition, an evaluation strategy was not developed at the outset of the program and remained outstanding as at May 2013, notwithstanding that most funding agreements had been signed by then and the program was nearly two years into its three year duration. Such a situation will have an adverse effect on the quality of advice to Ministers on any proposal to provide further funding to the program or to a similar program5, as well as in assessing the contribution the program has made to the objectives of the National Urban Policy.

12. As indicated, this audit of the LCP has identified improvements in key aspects of Infrastructure’s grants administration practices, which should be embedded in all grant programs within the department. The ANAO has made three recommendations to address the further opportunities for improvement mentioned above relating to:

- enhancing the assessment of eligible applications, by clearly and consistently establishing benchmarks for scoring against assessment criteria and a minimum score an application is required to satisfy for each criterion in order for an application to be considered for possible recommendation;

- recording the value for money offered by each proposal under consideration, having regard to the published program objectives and assessment criteria; and

- developing an evaluation strategy during the design of a program.

Key findings by chapter

Program governance framework (Chapter 2)

13. The LCP guidelines were sound. Importantly, they clearly identified and grouped eligibility and assessment criteria, and specified the process for lodging applications. The guidelines were also underpinned by a suite of governance documents necessary for the sound administration of the program.

14. The development of the guidelines and governance documents were informed by a number of initiatives implemented by Infrastructure to improve its program management and delivery (consistent with advice that the department had provided to the JCPAA). These included guidance from the department’s program managers’ toolkit and Major Infrastructure Projects Office. A review-ready workshop6 and a program implementation review at the planning stage of LCP, were also undertaken. However, some valuable suggestions made at the workshop were not implemented and the program implementation review was only undertaken at one of the three critical review points.

15. Further, while the program managers’ toolkit promoted the importance of program monitoring and evaluation, notably absent from the governance documents was a plan for measuring and evaluating the extent to which the LCP successfully achieved the program’s outcomes. Also absent was a strategy for ensuring the LCP funding would generate lessons that would then be transferred and applied with the desired objectives of improved planning and design.

Access to the program (Chapter 3)

16. The grant application process was accessible to eligible applicants. The process for applying for LCP funding was effectively communicated to potential applicants through the guidelines and supplementary documentation. This was further supported by Infrastructure sending information and reminders directly to eligible organisations, and responding promptly to queries.

17. There were 170 applications received and these were assessed against the eligibility criteria as published in the LCP guidelines. Four applications were assessed as ineligible during the initial eligibility check. A further three applications were reassessed as ineligible during the subsequent merit-assessment stage. Therefore, 96 per cent of applications were assessed as eligible.

18. However, there were shortcomings with Infrastructure’s implementation of its eligibility checking process. Assessors were to complete an eligibility checklist for each application. ANAO analysis of the available eligibility checklists—Infrastructure was unable to locate checklists for six applications—found that assessors had not recorded whether the application was eligible or ineligible on 40 per cent of these. Only one had been signed off as having being checked by the assessment team leader. Further, there were 43 applications for which eligibility concerns requiring follow-up were recorded, but the subsequent resolution of those concerns and decision to declare them eligible was not recorded.

19. Infrastructure advised ANAO that ‘given the unexpected large number of applications that were received and that met eligibility requirements, the eligibility checklist process was truncated.’ A risk with such an approach is that non-compliant applications may proceed to merit-assessment stage. In the interests of probity and fairness, it is expected that non‑compliant applications would be clearly identified as ineligible and excluded from further consideration. The truncation of eligibility checking is an issue raised in earlier ANAO performance audits.7 While the shortcomings identified with respect to LCP do not appear to have affected the funding outcome, these risks could be realised under future grant programs if the department does not adopt more robust eligibility checking processes.

Assessment of eligible applications (Chapter 4)

20. Improvements were evident in Infrastructure’s merit-assessment approach compared with earlier grant programs audited by ANAO. In particular, all eligible applications were assessed against the published assessment criteria, with a scoring approach adopted that enabled the relative merits of applications against each criterion, and in aggregate, to be compared. Specifically, applications were awarded a score out of five against each applicable criterion, which were added to produce an overall score for each project.

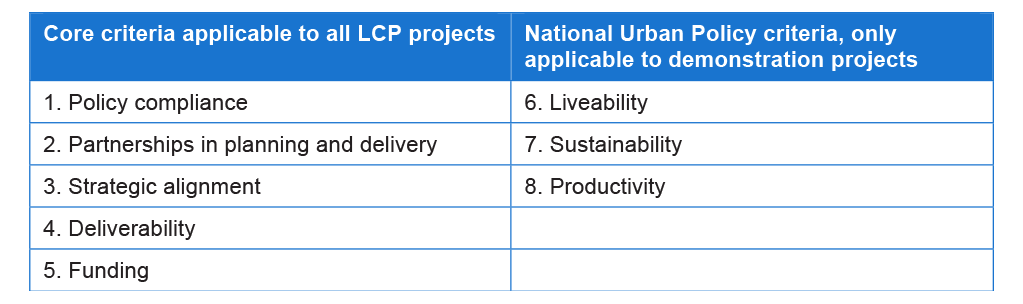

21. There were eight assessment criteria for LCP; the first five were applicable to all projects and the other three were only applicable to stream two (demonstration) projects. These are set out in the table below.

Table S.1: LCP assessment criteria

Source: ANAO analysis of Liveable Cities Program guidelines.

22. The assessment records indicate that applications were consistently and transparently assessed against criterion 1, 6, 7 and 8. That is, the extent to which the project met the Council of Australian Governments’ national criteria for cities and the goals of the National Urban Policy.

23. In relation to criterion 2, 3, 4 and 5, while assessors adequately recorded their findings, there were inconsistencies in the scores awarded. This reflected the approach taken to staffing the assessment work and the lack of benchmarks to promote a consistent approach. Further, the planned quality assurance processes were not fully implemented. This situation adversely affected the reliability of the scores as a basis for determining the varying merits of competing applications in terms of the assessment criteria. Reliability could have been enhanced if, for each criterion, the assessor guidance contained benchmarks for the achievement of each score on the rating scale and if those benchmarks had then been consistently applied in the assessment process. Such an approach is quite common in grant programs administered by other agencies.

24. Stream two applications were required to score highly against at least one of criterion 6, 7 and 8 to be considered for funding, which corresponded with the three goals of the National Urban Policy. Beyond this, there was no minimum standard set against the assessment criteria under either stream one or stream two. That is, eligible applications were ranked in order of merit solely on the basis of their overall scores. Applications therefore could be—and were—recommended for funding notwithstanding that they had been assessed as not satisfying an assessment criterion. As has previously been noted by ANAO, it is most unlikely that a proposal that does not demonstrably satisfy the merit assessment criteria set out in the published program guidelines to be considered to represent an efficient and effective use of public money and to be consistent with relevant policies (which are key elements of FMA Regulation 98).9

25. An order of merit list was produced for each funding stream. Infrastructure selected the 18 highest ranked projects from the stream one order of merit list for funding recommendation. It also selected the five highest ranked projects from the stream two order of merit list. As the next six projects on that list were located in major cities already represented amongst the five higher ranked projects, they were not selected for recommendation. Instead, Infrastructure recommended the four projects listed immediately below them, which were located in major cities not already represented under stream two. Consistent with the program objectives, this approach was designed to provide a more diverse mix of projects in terms of project geography and project type.

26. Infrastructure advised the ANAO that the process it undertook allowed for the recommendation of projects that represented value for money and a proper use of Commonwealth resources in the context of the objectives of the program. However, the department did not make an assessment record of whether, and to what extent, each eligible application had been assessed as representing value for money. Further in this respect, the department has advised ANAO that it considered that all ranked applications represented value for money, just to differing degrees. This is notwithstanding that the majority of the ranked applications had been scored a zero or a one out of five against one or more of the core assessment criteria.10 Given the program was established to operate through a competitive, merit-based selection process, applications assessed as not meeting the criteria are most unlikely to represent value for money in the context of the program objectives.11 As a minimum, some further explanation would be expected.

Advice to the Minister, and funding decisions (Chapter 5)

27. Considerable improvement was evident in the approach taken by Infrastructure to briefing its Minister on the outcomes of the application assessment process, compared with other Infrastructure-administered grant programs examined by ANAO in recent years. In particular, the department provided the Minister with a clear funding recommendation that outlined, based on the results of the eligibility checking and merit-assessment processes, those applications that were considered to best contribute to the achievement of the program objectives.

28. Further, a record was made of those instances where the Minister decided to not approve some of the recommended applications, and approve some of those projects not recommended for funding.12 It is open to a Minister to reach a decision different to that recommended by the agency. In such instances, it is expected that the recorded reasons for the decision would relate to the published program guidelines (including the relative merits of competing proposals in terms of the assessment criteria).

29. The Minister had rejected four recommended projects on the basis of preferring to fund three projects that had not been recommended. For one of the projects approved but not recommended, the recorded reason was relevant to the criteria and policy objectives and the project was selected over two recommended projects (being an equally ranked project and a lower-ranked project). Conversely, the recorded reasons for funding two other projects that had not been recommended did not relate to the program guidelines. In one case, a lower-ranked project was approved over a higher-ranked project in Adelaide after taking into account the expressed preferences of a South Australian Minister. In the other case, a stream one project was approved over a stream two project, taking account of the preferences of a Tasmanian Minister in favouring an application submitted by his government over another Tasmanian project submitted by a council (both state and local governments were eligible to compete for funding). The program guidelines did not provide for state government views to be sought, and this approach was not adopted in respect to other states.

30. In summary, the Minister approved 19 stream one (planning and design) projects for a total of $5.56 million and seven stream two (demonstration) projects for $14.44 million. The Minister later withdrew his approval of $500 000 for a stream one project that had been recommended for funding.13

Grants reporting, funding distribution and feedback to applicants (Chapter 6)

31. The outcomes of the LCP funding round were announced publicly, albeit over a six-week period.14 All applicants were advised in writing of the outcome and unsuccessful applicants were given a reasonable opportunity to receive feedback. In addition, an avenue for submitting complaints or enquiries about funding decisions was made available to applicants but no complaints were received.

32. The distribution of funding in geographic terms, and the nature of the demonstration projects, provided the desired mix foreshadowed in the program guidelines. In terms of political distribution, the majority of recommended and approved applications, and program funding, related to projects located in an electorate held by the Australian Labor Party. In this context, there were more electorates held by the Australian Labor Party that were eligible to receive funding.

33. To help achieve transparency and accountability in government decision-making, agencies and Ministerial decision-makers are subject to a number of reporting requirements. However, the extent to which the reporting requirements could promote these principles was limited as a consequence of LCP operating under two financial frameworks. That is, only the LCP payments to the 18 local government recipients were defined as grants and so were bound by the ministerial and public reporting requirements under the CGGs.15 As such, the Minister was required to report to the Finance Minister only one of the three instances where he decided to approve a funding proposal that had not been recommended by Infrastructure. However, the report for calendar-year 2012 did not identify any instances where the Minister had approved a grant not recommended by Infrastructure.

34. Another consequence of operating under two frameworks is that details of LCP agreements with local government recipients were to be reported on Infrastructure’s website, whereas the agreements with state governments were to be published on the Standing Council on Federal Financial Relations website. Having the information dispersed across multiple sites in this way reduces the efficiency and effectiveness of website publication as an accountability tool. This limitation was somewhat addressed by the department also choosing to publish the details of all LCP projects elsewhere on its website.

Project and program delivery, and evaluation (Chapter 7)

35. According to the LCP guidelines, Infrastructure had planned to have signed agreements in place, and the 2011–12 appropriation of $10 million expended, by 30 June 2012. However, only two agreements were signed, and no payments were made, in 2011–12. By the end of April 2013 (10 months after the target date for signing agreements):

- agreements had been signed for 22 projects totalling $15.33 million in funding;

- agreements had not yet been signed for the other two projects approved for a total of $3.87 million; and

- $0.8 million of the available funding remained unallocated (largely due to the reversal of a funding decision and a withdrawal by a successful applicant).

36. The LCP was originally due to end on 30 June 2013. However, only one of the signed agreements required the funded project to be completed by this date. The program’s end-date was extended to 30 June 2014 via a movement of funds. Of the 22 signed agreements, 18 were scheduled to be completed by the extended end date.

37. There were also a number of aspects of the signed agreements that may not adequately protect the Commonwealth’s interests. In particular, as has often been the case with grant programs administered by Infrastructure, payments have been contracted to be made in advance of project needs. This includes, under some agreements, a significant proportion of the funds being paid upfront without there being a demonstrated net benefit to the Commonwealth from doing so. All LCP payments are contracted to be made before the final project deliverable. In addition, Infrastructure did not fully implement the risk management strategies it had advised the Minister would be undertaken.16

38. The signed agreements contain requirements that will assist Infrastructure to monitor and evaluate performance at the individual project level. However, these requirements do not facilitate monitoring and evaluation of the desired program outcomes. In addition, it is unclear from the LCP guidelines or signed agreements how the department will identify lessons learned from the projects and then disseminate these to key stakeholders in a way that will help improve planning and design across the 18 major cities.

39. Further, the selection of LCP projects and development of funding agreements was not informed by an evaluation plan or program performance measurement framework. While such a plan can still be developed, the timing reduces Infrastructure’s capacity to collect the performance data required for a robust and comprehensive program evaluation.

Agency responses

40. The proposed audit report issued under section 19 of the Auditor‐General Act 1997 was provided to Infrastructure and the Minister, and relevant extracts were also provided to the Department of Finance and Deregulation and to the Department of the Treasury. Only Infrastructure provided formal comments on the proposed audit report and these are below, with the full response included at Appendix 1:

The Department notes the ANAO’s positive comments about its practices under the Liveable Cities Program, particularly around the merit assessment of applications and the provision of clear funding recommendations to the Minister. The Department further notes the ANAO’s conclusion that the nature and distribution of successful projects ‘provided the desired mix foreshadowed in the program guidelines’ so as to contribute to the objective of improving the planning and design of major cities.

In relation to the reporting and financial frameworks relevant to the program, the Department notes that it followed all relevant advice at the time and met, and in some cases, exceeded, the relevant reporting requirements. The ANAO’s concerns about the inconsistencies in the relevant frameworks should be directed to the relevant central agencies.

The Department notes the ANAO’s comments regarding some administrative issues that arose in the eligibility and assessment processes but stresses that these had no material impact on the selection of projects that were eventually funded. In relation to the eligibility checklists, in particular, the eligibility of all projects was considered during the broader assessment process.

The Department stands by its assessment process, which saw those projects receiving the highest overall merit score, and representing the greatest value for money, being recommended to the Minister. All successful projects met the eligibility requirements and received high overall merit scores. While some high-ranking projects were assessed as having low scores against the partnerships criteria, in particular, these criteria were not eligibility requirements. Through the design of the program, the Department sought to encourage partnerships, but not to exclude projects without a high degree of partnership. Where projects put forward by individual proponents did very well against the other criteria they were still competitive. This allowed an appropriate mix of projects to be selected for funding.

Through its program design and implementation, the Department has been able to deliver a strong suite of projects, including a number of innovative projects and those where strong partnerships have been formed across jurisdictional and other boundaries. This has been done at the same time as working to establish new processes and manage the uncertainty inherent in a new program around the level of demand and the nature of applications. We note the ANAO’s positive comments about the opportunities provided by the Department for feedback from unsuccessful applicants and, further, that there has not been a single complaint about the program by any stakeholders.

ANAO Comment:

41. The fourth paragraph of Infrastructure’s response suggests that ANAO concerns about the composition of the merit list related only to applications being included that had scored poorly against the ‘partnerships’ criterion, which was identified in the program guidelines as being core criterion five ‘funding’. However, that was not the only core criterion where a significant number of applications had been scored poorly. For example, a quarter of the applications on the merit list had been scored a zero or a one out of five against one or more of the other core criteria (including the ‘policy compliance’ criterion). This situation was reflected in the merit list descending to applications that had an overall total score as low as three out of 25. See further at paragraphs 4.82 and 4.88.

Recommendations

Set out below are the ANAO’s recommendations and the Department of Infrastructure and Transport’s abbreviated responses. More detailed responses are shown in the body of the report immediately after each recommendation.

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 4.80 |

ANAO recommends that the Department of Infrastructure and Transport further improve the assessment of eligible applications to competitive, merit-based grant programs by: (a) clearly and consistently articulating benchmarks and/or standards to inform the judgment of assessors when considering the extent to which an application has met the published assessment criteria; and (b) establishing a minimum score that an application must achieve against each assessment criterion in order to progress in the assessment process as a possible candidate to be recommended for funding. |

| Infrastructure response: Agreed in part | |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 4.85 |

ANAO recommends that the Department of Infrastructure and Transport, in the conduct of grants assessment processes, clearly record the value for money offered by each proposal under consideration in the context of the program objectives and criteria. |

| Infrastructure response: Not agreed | |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 7.69 |

In the interest of achieving the desired program outcomes, ANAO recommends that the Department of Infrastructure and Transport develops an evaluation strategy for grant programs at an early stage of the program design, so that the necessary information to evaluate the contribution that individual projects make to the overall program outcomes can be captured during the application assessment process and reflected in funding agreements signed with the successful proponents. |

| Infrastructure response: Agreed |

Footnotes

[1] Our Cities, Our Future—a national urban policy for a productive, sustainable and liveable future, known as the National Urban Policy, was released by the Australian Government on 18 May 2011. It sets out the Government’s objectives and priorities for Australia’s 18 major cities, as well as the Government’s strategies, programs and actions to deliver its urban agenda.

[2] These are the 18 Australian cities that have populations greater than 100 000.

[3] Subsequently, the Minister reversed his approval of a $500 000 project and one successful applicant withdrew, declining the offered $300 000. See paragraphs 7.6 and 5.36 to 5.38 for further information.

[4] In particular, there were inconsistencies in the scores awarded and planned quality assurance processes were not fully implemented. This situation adversely affected the reliability of the scores as a basis for determining the varying merits of competing applications in terms of the assessment criteria.

[5] The original policy proposal envisaged a $260 million program.

[6] A review-ready workshop is a facilitated discussion that aims to help teams think through goals, needs, outcomes and success criteria for their program, policy or regulatory activity.

[7] See, for example, ANAO Audit Report No.3 2010–11, The Establishment, Implementation and Administration of the Strategic Projects Component of the Regional and Local Community Infrastructure Program, Canberra, 27 July 2010.

[8] FMA Regulation 9 sets out the principle obligation applying to the approval of all spending proposals. It requires an approver to make reasonable inquiries in order to be satisfied that a proposal would be a proper use of Commonwealth resources and would not be inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth. For grant spending proposals, the relevant policies include the CGGs and the specific guidelines established for the program.

[9] The shortcomings with such an approach were previously raised by ANAO Audit Report No.38 2011–12, Administration of the Private Irrigation Infrastructure Operators Program in New South Wales, Canberra, 5 June 2012 and Audit Report No.1 2012–13, Administration of the Renewable Energy Demonstration Program, Canberra, 21 August 2012.

[10] Of the 119 ranked applications, which were scored by the department according to the approach outlined in Figure 4.1, 60 applications scored a zero (‘unacceptable—does not meet the criteria at all or attempt to’) and a further 11 applications scored a one (‘very poor—meets some criteria but unacceptable’) against one or more of the assessment criteria.

[11] This has been recognised in respect to some Australian Government grant programs, with the guidelines outlining that applications must rate highly against each of the merit criteria to receive a grant offer.

[12] These projects are identified in Table 5.1.

[13] No reason was recorded by the Minister, nor was this required. The project was located in a state electorate that would be held by the Minister’s spouse following a proposed redistribution of electoral boundaries. See further at paragraphs 5.36 to 5.38.

[14] As a matter of good practice, it is preferable for all decisions on successful or unsuccessful projects to be announced together, or within a relatively short period of time.

[15] The LCP payments to state government recipients were defined as payments made for the purposes of the Federal Financial Relations Act 2009. Such payments are explicitly excluded from the definition of a grant. The JCPAA stated in Report No. 427, Inquiry into National Funding Agreements, that it shared the concerns of the Auditor-General regarding the interaction between the federal financial relations framework and the grants framework. It recommended that Finance examine the interaction between the new grants framework and grant payments delivered under the FFR framework, and proposed options to remove inconsistencies and improve governance arrangements for all grants provided to states and territories. See further at paragraphs 2.18 to 2.20.

[16] For example, in respect of five stream two projects, Infrastructure had advised the Minister that it would implement twelve specific risk treatments prior to signing the agreements. However, it only implemented four of these risk treatments. Further, Infrastructure’s legal services section identified risks relating to the substantial involvement of a third-party in one of the projects and suggested amendments to the draft agreement so as to protect the Commonwealth’s interests. These amendments were not incorporated into the signed agreement.