Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Design and Implementation of Round Two of the National Stronger Regions Fund

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the design and implementation of round two of the National Stronger Regions Fund.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The National Stronger Regions Fund was a competitive grants program administered by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD). The program’s objective was to ‘fund investment ready projects which support economic growth and sustainability of regions across Australia, particularly disadvantaged regions, by supporting investment in priority infrastructure’.

2. Local government authorities and not-for-profit organisations were eligible to apply for grants from $20 000 through to $10 million. Grants were available for capital projects that involved the construction of new infrastructure, or the upgrade or extension of existing infrastructure, and that delivered an economic benefit to the region. Projects could be located in any Australian region or city.

3. The program’s establishment was a 2013 federal election commitment of the then Opposition, with $1 billion to be made available over five years from 2015–16. Mid-way through the third funding round, the program’s early abolition was announced as a 2016 federal election commitment of the Government. In total, 229 applications were approved for $632.2 million via the three funding rounds.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and implementation of round two of the National Stronger Regions Fund. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Did the application and assessment process attract, identify and rank the best applications in terms of the published criteria and value for money?

- Were the decision makers appropriately advised and given clear funding recommendations?

- Were the decisions taken transparent and consistent with the program guidelines?

- Was the design and implementation of the program outcomes oriented, and are arrangements in place for program outcomes to be evaluated (including the likely economic benefits to regions)?

Conclusion

5. Program design and implementation was largely effective. In addition, earlier audit recommendations aimed at improving the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development’s assessment of applications, funding advice to decision-makers and evaluation of program outcomes have been implemented.

6. The application process for round two funding was accessible and attracted sufficient applications of merit. The eligibility requirements were appropriate and consistently applied. Applications assessed as ineligible were excluded from further consideration.

7. The merit criteria were consistent with the program’s objective. The criteria would have been more effective at maximising the achievement of the underlying policy intent if explicit consideration had been given to the magnitude of economic benefits claimed and to the socio-economic circumstances and unemployment rates of regions.

8. Applications were assessed transparently and consistently against the published merit criteria. The department then used the results to rank applications in terms of its assessment of them against the criteria and the requirement to achieve value with relevant money.

9. The Ministerial Panel was appropriately advised and given a clear funding recommendation. There was a clear line of sight from the results of the department’s assessment of eligible applications against the merit criteria, the department’s selection of 104 applications for funding recommendation, the Ministerial Panel’s reassessment of 28 applications, through to the approval of 111 applications in round two. Internal documentation recording funding decisions, and their reasons, has been further improved by the department but its responses to Parliamentary scrutiny when questioned about its input to those funding decisions were not transparent (this issue has arisen previously).

10. Arrangements are in place for program outcomes to be evaluated, including the likely economic benefits to regions. Each approved project had been assessed as likely to deliver an economic benefit.

Supporting findings

Application process and eligibility checking (Chapter 2)

11. The grant application process was accessible, transparent and effectively communicated. Support was available to potential applicants, including from the network of Regional Development Australia committees. There were 514 applications submitted in round two seeking $1.5 billion (or five times the funding awarded).

12. DIRD identified 83 of the 514 applications submitted in round two (16 per cent) as being ineligible and then excluded them from further consideration as candidates for funding. The eligibility requirements were appropriate and consistently applied. They were also expressed reasonably clearly but the inclusion of examples as to what constituted written confirmation of partner contributions for eligibility purposes would have better informed potential applicants and improved compliance. One applicant later withdrew, leaving 430 eligible applications competing for funding.

Merit assessment (Chapter 3)

13. The assessment method enabled the department to clearly and consistently rank the 430 eligible applications in order of their relative merits against the published criteria. The 147 applications assessed as not satisfying one or more of the merit criteria were identified as not representing value with relevant money and excluded as candidates for funding recommendation.

14. The merit criteria were largely appropriate for identifying the most meritorious applications in the context of the program’s objective. The criteria also appropriately addressed whether approved projects would be delivered and the resulting infrastructure maintained. The criteria would have been more effective if explicit consideration was given to the: magnitude of economic benefits claimed; socio-economic circumstances and unemployment rates of regions; and risks associated with third-party delivery of funded projects.

15. The assessment work was conducted to a high standard. Assessors were well trained and supported. Their findings were quality assured by experienced officers, which added considerably to the consistency of assessments. The assessments were transparent, with a clear audit trail of the process and results maintained. The administrative cost of the assessment phase was reasonable and equated to 0.5 per cent of the funding awarded under round two.

Funding advice and decisions (Chapter 4)

16. DIRD appropriately advised the Ministerial Panel on the individual and relative merits of competing applications. DIRD made a clear recommendation that 104 applications be funded for a total of $266.5 million. The selection of applications for funding recommendation was based on their position on DIRD’s order of merit list and, in some cases, on the amount of funding they had requested. The advice was consistent with implementation of previous ANAO recommendations and complied with all but one of the mandatory briefing requirements—it had not informed Ministers of the legal authority for the proposed grants.

17. The funding decisions taken were consistent with the competitive merit-based selection process set out in the program guidelines. The Ministerial Panel considered the department’s advice, reassessed 28 of the applications against the merit criteria, and then selected 111 applications for funding totalling $293.4 million. The applications were selected based on their position on the Ministerial Panel’s order of merit list and, in some cases, on the amount of funding they had requested.

18. The funding decisions and their bases were transparent in the departmental records. DIRD’s responses to Parliament when questioned about its input to those funding decisions were not transparent (this issue has arisen previously).

Achieving outcomes (Chapter 5)

19. All 111 projects approved under round two had been assessed as likely to deliver an economic benefit to regions. Given the mix of projects approved, the majority are also likely to deliver social and community benefits.

20. Consistent with government policy, regions with low socio-economic circumstances and high unemployment received priority in that they were relatively more successful at attracting funding in round two. There was potential for DIRD to have included an explicit mechanism for targeting projects in such regions so as to maximise the achievement of the policy intent. In the absence of such a mechanism, the Ministerial Panel gave consideration to socio-economic circumstances in its assessment of round two applications.

21. Arrangements are in place for program outcomes to be evaluated. An evaluation strategy was developed during the program design stage and a review of the first funding round has been undertaken. The review’s findings included that, with some minor refinements, the program over its life should deliver economic growth for disadvantaged areas across the country.

Recommendations

Recommendation No. 1

Paragraph 5.17

That the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development ensures its program designs contain explicit mechanisms for targeting funding in accordance with the stated policy objectives of the program.

Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

22. The proposed audit report issued under section 19 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 was provided to the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development and to the Minister for Regional Development. An extract was provided to the Department of Finance. The Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development’s summary response to the report is below, while its full response is at Appendix 1.

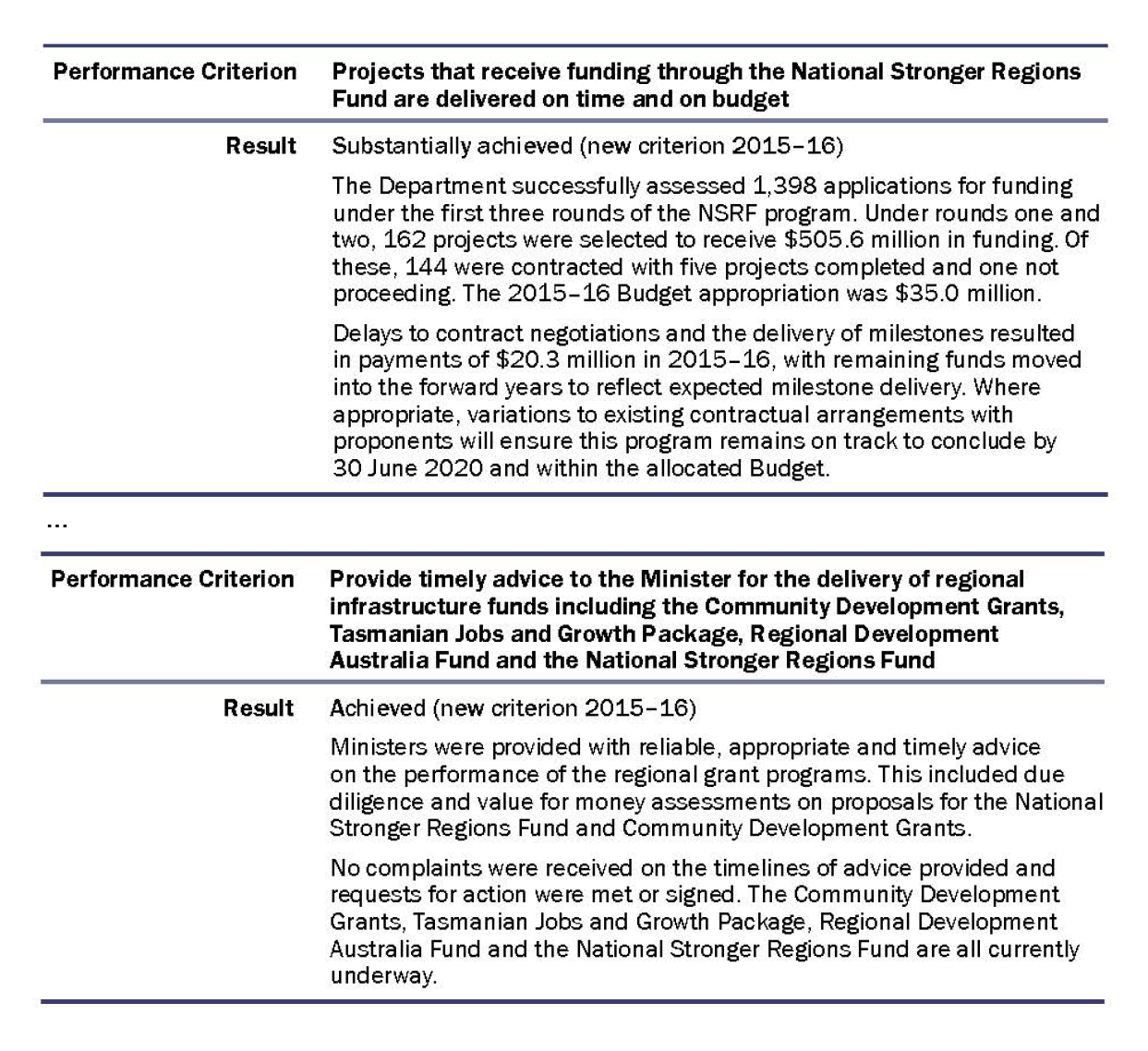

The Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (the Department) welcomes the ANAO report and notes the comments that “The merit criteria were consistent with the program’s objective” and “Consistent with government policy, regions with low socio-economic circumstances and high unemployment received priority in that they were relatively more successful at attracting funding in round two”.

The Department agrees with the report’s recommendation, and the comment that “The merit criteria would have been more effective at maximising the achievement of the underlying policy intent if explicit consideration had been given to the magnitude of economic benefits claimed and to the socio-economic circumstances and unemployment rates of the regions”.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The establishment of a $1 billion National Stronger Regions Fund was a 2013 federal election commitment by the then Opposition. The program’s objective was to ‘fund investment ready projects which support economic growth and sustainability of regions across Australia, particularly disadvantaged regions, by supporting investment in priority infrastructure’. Funding was made available over five years from 2015–16 to be allocated via discrete rounds using a competitive merit-based selection process.

1.2 Local government authorities and not-for-profit organisations were eligible to apply for grants from $20 000 through to $10 million. Grants were available for capital projects that involved the construction of new infrastructure, or the upgrade or an extension of existing infrastructure, and that delivered an economic benefit to the region. Projects could be located in any Australian region or city.

1.3 The National Stronger Regions Fund was administered by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD). Funding decisions were made by a Ministerial Panel in consultation with the National Infrastructure Committee. Three funding rounds were held and an overview of each is provided in Table 1.1. In total, 229 applications were approved for $632.2 million.

Table 1.1: Overview of the three funding rounds

|

|

Round one |

Round two |

Round three |

|

Funding requested |

|||

|

Date applications closed |

November 2014 |

July 2015 |

March 2016 |

|

Applications submitted |

405 applications |

514 applications |

479 applications |

|

Total funding requested |

$1.2 billion |

$1.5 billion |

$1.4 billion |

|

Funding awarded |

|||

|

Date funding decisions made |

May 2015 |

December 2015 |

October 2016 |

|

Applications approved |

51 applications |

111 applications |

67 applications |

|

Total funding approved |

$212.3 million |

$293.4 million |

$126.5 million |

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records.

1.4 The round three decision-making was delayed by the government assuming a caretaker role on 9 May 2016 in the lead up to the 2016 federal election. DIRD advised the ANAO in November 2016 that the Government’s election commitments had included funding 66 of the projects that had been submitted in round three for $199.8 million, with the majority of these to be delivered through the Community Development Grants Programme.

1.5 The Government’s 2016 election commitments also included re-focussing the program to become the Building Better Regions Fund. Funding will be available only to regional, rural and remote Australia and be broadened to include small community groups. It will introduce two streams, being infrastructure projects and community investments, and applications will be assessed in three categories depending on the size of the project. Round three therefore became the last round of the National Stronger Regions Fund. In reference to the distribution of the $1 billion originally budged for the National Stronger Regions Fund, DIRD advised the ANAO in October 2016 that:

- Funding of $631.8 million has been committed to projects under the NSRF.

- Funding of $48.6 million will be transferred to the Community Development Grants Programme, as advised in a letter dated 16 August 2016 from the Prime Minister, the Hon Malcolm Turnbull MP, to Senator the Hon Fiona Nash, Minister for Regional Development.

- Funding of $297.7 million will be transferred to the Building Better Regions Fund, as detailed in the Coalition’s Policy for a Stronger Economy and Balanced Budget document.

Joint Committee recommendations

1.6 The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit reviewed ANAO Report No. 9 2014–15 The Design and Conduct of the Third and Fourth Funding Rounds of the Regional Development Australia Fund. The Regional Development Australia Fund was the predecessor of the National Stronger Regions Fund. The recommendations made by the Joint Committee in its report of 11 August 2015 (Report 449) included:

- Recommendation 1

The Committee recommends that the Australian National Audit Office consider prioritising the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development—or, as applicable, the department responsible for administering the regional portfolio—in its continuing series of audits of agencies’ implementation of performance audit recommendations. - Recommendation 4

To encourage better practice grants administration, particularly concerning regional grants programs, the Committee recommends that the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) consider including in its schedule of performance audits:- priority follow-up audits of the effectiveness of grants program administration by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development;

- a standing priority audit focus on regional grants administration by the relevant department (with the specific timing of such audits as determined by the ANAO), noting that a potential performance audit of the design and implementation of the National Stronger Regions Fund is included in the ANAO’s current forward Audit Work Program.

1.7 The ANAO’s response to Recommendation 1 advised the Joint Committee that an audit of the former Department of Infrastructure and Transport’s (now DIRD’s) implementation of recommendations was included in Audit Report No. 53 2012–13 and that the ANAO would also examine the implementation of relevant earlier recommendations as part of the scope of performance audits of individual funding programs. In relation to Recommendation 4, the ANAO advised the Joint Committee that it had commenced this performance audit of round two of the National Stronger Regions Fund and that future audit coverage of regional grants administration would be considered in the context of developing the forward work program.

Audit approach

1.8 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the design and implementation of round two of the National Stronger Regions Fund.

1.9 To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Did the application and assessment process attract, identify and rank the best applications in terms of the published criteria and value for money?

- Were the decision makers appropriately advised and given clear funding recommendations?

- Were the decisions taken transparent and consistent with the program guidelines?

- Was the design and implementation of the program outcomes oriented, and are arrangements in place for program outcomes to be evaluated (including the likely economic benefits to regions)?

1.10 The audit also examined the extent to which round two of the National Stronger Regions Fund reflected the implementation of relevant recommendations made in ANAO Audit Reports:1

- No.3 2012–13, The Design and Conduct of the First Application Round for the Regional Development Australia Fund;

- No.1 2013–14, Design and Implementation of the Liveable Cities Program; and

- No.9 2014–15, The Design and Conduct of the Third and Fourth Funding Rounds of the Regional Development Australia Fund.

1.11 The scope of the audit was the design and implementation of round two of the National Stronger Regions Fund up to the funding decisions being made. To the extent that it informed the audit, the scope also included an examination of the establishment of the program and the design and implementation of the first and third funding rounds.

1.12 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $336 000.

2. Application process and eligibility checking

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the process for applying for round two funding was accessible and whether ineligible applications were identified and then excluded from further consideration. This included examining whether the application process and eligibility requirements were appropriate and effectively communicated.

Conclusion

The application process for round two funding was accessible and attracted sufficient applications of merit. The eligibility requirements were appropriate and consistently applied. Applications assessed as ineligible were excluded from further consideration.

Was the application process accessible?

The grant application process was accessible, transparent and effectively communicated. Support was available to potential applicants, including from the network of Regional Development Australia committees. There were 514 applications submitted in round two seeking $1.5 billion (or five times the funding awarded).

2.1 The opportunity to access the National Stronger Regions Fund was open to local government bodies and not-for-profit organisations nationally. Discrete funding rounds were held, with eligible applications received by the closing date being assessed against published merit criteria and prioritised against competing applications for the available funding. This is known as a competitive merit-based selection process. It promotes open, transparent and equitable access to grants and can achieve better outcomes and value for money than alternate models.2

Communicating the process

2.2 The funding opportunity and processes were effectively communicated to potential applicants and other interested parties. The Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD) developed and implemented a comprehensive communications strategy, which was updated after each of rounds one and two to reflect lessons learned. In a survey commissioned by DIRD on completion of round one, 84 per cent of the applicant respondents agreed it was easy to find out about the National Stronger Regions Fund. Further, round two attracted sufficient interest from across both applicant types:

- 514 applications were submitted in round two seeking $1.5 billion or five times the funding awarded; and

- two thirds of the applications were from local government bodies and one third from not-for-profit organisations, consistent with the predecessor Regional Development Australia Fund.

2.3 The application, assessment and selection processes were explained in program guidelines, which were published on DIRD’s website for each funding round. The program guidelines were sufficiently clear and comprehensive. Additional detail was contained in a suite of supporting documents, including a Frequently Asked Questions document, a draft funding agreement and a guide to completing and lodging the electronic application form. The published material did not include the likely amount of funding to be awarded under the round.3 Applicants may have benefited from greater clarity on the eligibility requirement that partner contributions be confirmed (see paragraphs 2.13 to 2.15 below).

Supporting potential applicants

2.4 A range of mechanisms were available to assist potential round two applicants to understand the process and to develop and submit their applications. These were offered by DIRD and by Regional Development Australia committees, which balanced providing useful support with maintaining equity and probity.

2.5 In the lead up to round two DIRD held open information sessions in each capital city, nine regional centres and via teleconference. These provided an overview of the application process, general feedback on round one and advice on how to prepare a competitive application. The sessions were well publicised and attracted an estimated 470 attendees. The presentation slides were made available on DIRD’s website.4 Those who had competed in round one were also offered individualised feedback on how they might have improved their application.

2.6 Potential applicants could communicate with the National Stronger Regions Fund team via email. Where a new question was posed, the Frequently Asked Questions document was updated so that others could also be informed by the department’s response. A separate helpdesk provided technical support to those requiring assistance accessing the department’s grant management system or submitting their application online via that system. The helpdesk received a total of 756 calls and emails relating to round two.

2.7 The national network of 55 Regional Development Australia committees promoted the National Stronger Regions Fund, held information sessions and grant writing workshops, and provided advice and guidance to individual applicants. Regional Development Australia committees had been consulted in the development of 88 per cent of the applications submitted in round two, with these applications having a higher success rate in obtaining funding (23 per cent compared with 15 per cent). There was no conflict of interest involved as the Regional Development Australia committees did not play a role in the assessment or prioritisation of National Stronger Regions Fund projects.

Submitting applications

2.8 Round two opened to applications on 15 May 2015 and closed at 5:00 pm local time on 31 July 2015. All application forms were completed and submitted online via DIRD’s grant management system.

2.9 DIRD advised users in advance that its system would be unavailable from 9:30 pm to 11:00 pm on 22 July 2015 due to a server upgrade. A related data backup running from 1:30 pm to 9:30 pm caused seven newly created applications to be lost. It also prevented any edits made during the backup period to 92 draft applications, and to the organisational details of 21 applicants, from being saved. DIRD properly managed the situation. It notified the applicants of the data loss on 23 July and offered to email them the last saved copy of their application. Following a request from an applicant, the closing date was extended by one business day to 3 August 2015 for all affected applications and applicants.5

2.10 Ultimately, 435 organisations submitted 514 application forms and over 9500 supporting documents for consideration. The system was able to manage the influx of applications and supporting documents at the end of the application period. Despite the department urging applicants to lodge early, applicant behaviour did not change. The proportion of applications submitted on the closing date was 63 per cent in round one, 61 per cent in round two and 75 per cent in round three. These figures are a message to other agencies to ensure their systems can similarly cope and to future grant applicants of the need to submit early if they are to have ready access to technical and other support.

Were ineligible applications identified and then excluded from further consideration?

DIRD identified 83 of the 514 applications submitted in round two (16 per cent) as being ineligible and then excluded them from further consideration as candidates for funding. The eligibility requirements were appropriate and consistently applied. They were also expressed reasonably clearly but the inclusion of examples as to what constituted written confirmation of partner contributions for eligibility purposes would have better informed potential applicants and improved compliance. One applicant later withdrew, leaving 430 eligible applications competing for funding.

2.11 The eligibility requirements that an application had to satisfy in order to compete for round two funding were set out in the published program guidelines. The requirements were appropriate, reasonably clear and included that:

- applications be for a grant of at least $20 000 and up to $10 million;

- the grant amount be at least matched by cash contributions from the applicant and/or from other project partners;

- written confirmation of all cash and in-kind contributions be provided; and

- the project be a capital project involving the construction of new or upgraded infrastructure that delivers an economic benefit to the region beyond the period of construction.

2.12 DIRD checked all 514 applications for compliance with the eligibility requirements. The requirements were applied consistently and the results were documented and quality assured. There were 83 applications (16 per cent) assessed as ineligible and these were excluded from further consideration as candidates for round two funding. One applicant later withdrew, leaving 430 eligible applications competing for funding. Ultimately the department assessed 283 of these as having at least satisfied all of the merit criteria and as representing value with relevant money. These sought 2.7 times the funding awarded and so the round had attracted sufficient applications of merit.

Requirement that partner contributions be confirmed

2.13 By far the most common basis for ineligibility was having unconfirmed partner contributions. In total across the three funding rounds, DIRD assessed 194 applications as ineligible against the requirement that partner contributions be confirmed in writing. The applicant’s own contributions were automatically confirmed via a mandatory declaration in the application form whereas written confirmation of the cash and in-kind contributions from any other partners needed to be submitted with the application form.

2.14 There were 269 applications submitted in round two that listed cash and/or in-kind contributions from partners other than the applicant. DIRD identified that 66 of these applications (25 per cent) contained unconfirmed partner contributions either in full or in part. It also identified that, in some cases, the unconfirmed amounts were not material to the overall project. DIRD recorded in an ‘eligibility issues register’ the decision to accept applications as eligible ‘where the unconfirmed contribution/s can be deemed to have little or no impact on the successful implementation and completion of the project.’ Following consistent consideration of the unconfirmed amounts relative to the total project cost and to any contingency provisions, DIRD reassessed 21 of the 66 applications as eligible against the requirement and recorded the basis for each reassessment. The other 45 applications remained ineligible in round two.6

2.15 The suite of round two materials consistently advised that written confirmation of partner contributions was required. The materials may have been further improved by:

- examples of what constituted satisfactory evidence of confirmation for eligibility purposes;

- an explanation of how loans were to be treated and evidenced. There was some inequity in this regard, as the requirement was applied differently depending on how the applicant chose to record the loan amount. If the applicant recorded the loan as part of its own contribution, then the mandatory declaration sufficed as evidence of confirmation. If the applicant included the financial institution in its list of project partners, then evidence of a signed loan contract was required (five applications that contained an offer of a loan, expression of interest or similar document from a financial institution were assessed as ineligible); and

- the option to record partner contributions as ‘unconfirmed’ being either removed from the application form or activating a warning that it may result in the application being assessed as ineligible. That is, the application form included ‘unconfirmed’ in a list of three options that applicants were to select from when recording their partner contribution details (the others being ‘confirmed’ and ‘received’). This may have given applicants the impression that ‘unconfirmed’ was a valid option. The ANAO identified 16 applications in round two that had ‘unconfirmed’ selected against cash or in-kind contributions from other partners, of which 14 were assessed as ineligible. DIRD had reassessed the other two applications as eligible following consideration of the materiality of the unconfirmed amounts.

3. Merit assessment

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the merit assessment approach provided a clear and consistent basis for differentiating between competing applications of varying merit. Further, whether the merit criteria were appropriate and whether the assessment of applications against those criteria had been conducted to a high standard and at a reasonable cost.

Conclusion

The merit criteria were largely consistent with the program’s objective. The criteria would have been more effective at maximising the achievement of the underlying policy intent if explicit consideration had been given to the magnitude of economic benefits claimed and to the socio-economic circumstances and unemployment rates of regions.

Applications were assessed transparently and consistently against the published merit criteria. The department then used the results to rank applications in terms of its assessment of them against the criteria and the requirement to achieve value with relevant money.

Area for improvement

Related to the finding that the translation of the policy intent into the merit criteria could have been more effective, the ANAO has made a recommendation in Chapter 5 of this report aimed at ensuring the department’s future program designs contain explicit mechanisms for targeting funding in accordance with the stated policy objectives of the program.

Did the assessment method enable applications to be ranked according to merit and value with relevant money?

The assessment method enabled the department to clearly and consistently rank the 430 eligible applications in order of their relative merits against the published criteria. The 147 applications assessed as not satisfying one or more of the merit criteria were identified as not representing value with relevant money and excluded as candidates for funding recommendation.

3.1 The published merit criteria are summarised in Table 3.1. The criteria were drawn from, and were largely consistent with, the program’s objective.

3.2 The Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD) assessed all 430 eligible applications. Each application was awarded a score out of five against each merit criterion. Numerical ratings scales provide a clear and consistent basis for assessing applications against weighted criteria and for effectively differentiating between applications of varying merit. Its use was consistent with DIRD’s undertaking to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit that ‘in future we will use a numerical rating scale of 1 to 5’7 and with implementation of a previous ANAO audit recommendation.8

Table 3.1: Merit criteria used in round two

|

Program objective To fund investment ready projects which support economic growth and sustainability of regions across Australia, particularly disadvantaged regions, by supporting investment in priority infrastructure. |

||||

|

Merit criteria |

||||

|

Criterion 1 The extent to which the project contributes to economic growth in the region. |

Criterion 2 The extent to which the project supports or addresses disadvantage in a region. |

Criterion 3 The extent to which the project increases investment and builds partnerships in the region. |

Criterion 4 The extent to which the project and applicant are viable and sustainable. |

|

|

Criterion 2A |

Criterion 2B |

|||

|

The region (or part thereof) is disadvantaged. |

The project addresses the identified disadvantage. |

|||

|

43% of overall score |

14% of overall score |

14% of overall score |

14% of overall score |

14% of overall score |

Source: ANAO analysis of the published program guidelines for round two of the National Stronger Regions Fund.

3.3 The individual scores were used to calculate an overall score out of 35 for each eligible application. DIRD multiplied the score awarded against criterion 1 (economic growth) by three and then added it to the sum of the scores awarded against criteria 2A, 2B, 3 and 4. Criterion 1 therefore represented 43 per cent of the overall score. The heavy weighting reflected its importance to the program’s policy intent of supporting the economic growth of regions. The weighting applied to criterion 1, and the approach of scoring criterion 2 in two separate but equally weighted parts, had been clearly outlined to applicants in the program guidelines.

3.4 The overall scores provided a clear and consistent basis for ranking applications according to their relative merit against the published criteria. Applications with the same overall score were assigned equal weighting on the resulting order of merit list.

3.5 DIRD also used the scores awarded against the criteria as the basis for assessing whether or not each application represented value with relevant money.9 A threshold score of three out of five was applied to each criterion. The 147 applications that had scored less than three against one or more of the criteria were assessed as not representing value with relevant money. They were clearly identified on the merit list and excluded as candidates for funding recommendation. This approach recognises that applications assessed as not satisfactorily meeting the published merit criteria are most unlikely to represent value with relevant money in terms of the program’s objectives. The assessment approach, and the clear recording of the results against each application, was consistent with implementation of three previous ANAO audit recommendations.10

3.6 Overall, DIRD assessed 283 of the 514 applications submitted in round two (55 per cent) as being eligible applications that satisfied the merit criteria and represented value with relevant money. These were ranked into the top 15 positions on the merit list according to their overall scores, which ranged from 21 to 35. DIRD then drew from these when selecting applications for funding recommendation and provided the merit list to the Ministerial Panel to inform its decision-making (as outlined in paragraphs 4.10 to 4.11).

Were the merit criteria appropriate?

The merit criteria were largely appropriate for identifying the most meritorious applications in the context of the program’s objective. The criteria also appropriately addressed whether approved projects would be delivered and the resulting infrastructure maintained. The criteria would have been more effective if explicit consideration was given to the: magnitude of economic benefits claimed; socio-economic circumstances and unemployment rates of regions; and risks associated with third-party delivery of funded projects.

3.7 The merit criteria against which applications are assessed and selected are the key link between a program’s objectives and the outcomes subsequently achieved through the grants awarded.

3.8 The objective of the National Stronger Regions Fund was to ‘fund investment ready projects which support economic growth and sustainability of regions across Australia, particularly disadvantaged regions, by supporting investment in priority infrastructure’. As outlined below, this objective was reflected in each of the merit criteria adopted in round two. Although, as outlined in Chapter 5, there were limitations on the extent to which the merit criteria gave priority to ‘disadvantaged regions’, being those with low socio-economic circumstances and high unemployment.

Criterion 1 (economic growth)

3.9 Criterion 1 was intended to assess ‘the extent to which the project contributes to economic growth in the region’. The score awarded represented 43 per cent of an application’s overall score and so could substantially influence its position on the order of merit list. Consequently, the applications selected for funding recommendation had all achieved high scores of four or five against criterion 1.

3.10 Against criterion 1, 33 per cent of applications received a score of four and 20 per cent the maximum score of five. These applications had clearly explained and quantified the economic benefits of their project. They had also provided independent evidence that supported their claims and (for applications seeking more than $1 million) a cost-benefit analysis.

3.11 The assessment method did not include consideration of the magnitude of the economic benefits relative to competing projects and/or relative to the circumstances and economic needs of the region. For example, if a project was expected to generate 10 new jobs in a region, the assessment did not include consideration of whether the number and cost of those jobs was high or low relative to competing projects. Nor did it include consideration of the extent to which 10 jobs represented economic growth given the population and unemployment level of the region. That is, there was no starting point from which ‘growth’ was measured. Whether a region was economically strong or weak was also not a factor.

3.12 The method adopted means that the projects proposed in applications assessed as being value with relevant money against criterion 1 will generate an economic benefit if delivered, which is essential to achieving the program’s core objective. The difference then between a score of 3, 4 or 5 was more a measure of the degree of confidence in the validity of the economic benefits claimed and less a measure of the degree of economic growth in the region expected from the project.

Criterion 2 (addressing disadvantage)

3.13 Criterion 2 was assessed and scored in two equal parts. Applicants had to demonstrate against criterion 2A that their region was disadvantaged, and against criterion 2B that their project would directly address that disadvantage. The program guidelines did not define ‘disadvantage’ for the purposes of criterion 2.

3.14 The disadvantages claimed by applicants were broad ranging. Some cited economic disadvantages, such as declining industry sectors, low income households or high unemployment. Others referred to more social disadvantages, such as homelessness, a growing need for aged care or a shortage of cultural, sporting or recreational facilities. Many presented a mix of these.

3.15 To assist applicants demonstrate their claims, the program guidelines contained a list of possible indicators of disadvantage that were similarly broad ranging. As the applicants chose the nature and source of the evidence provided, data could not be reliably compared across applications.

3.16 Assessors exclusively considered the claims and evidence presented in each application. The process did not allow for research into, or consideration of, regional circumstances or disadvantages not claimed by the applicant. It did not include consideration of the severity of the disadvantage relative to competing applications and did not give scoring preference to particular types of disadvantage over others.

3.17 Most applications (91 per cent) achieved a score of at least three against criterion 2A because they had defined the nature of the disadvantages faced by their region and had provided some form of evidence in support of their claims. High scoring applications had also demonstrated that their region faced multiple disadvantages, had quantified those disadvantages and provided independent evidence.

3.18 Most applications (87 per cent) also achieved a score of at least three against criterion 2B, as they had made a reasonable link between their identified disadvantage and the expected outcomes of their project. Though they were less successful at attracting the maximum score, with only eight per cent receiving a score of five against criterion 2B compared with 29 per cent against criterion 2A. Applications awarded the maximum score of five against criterion 2B had clearly defined how the project would address the disadvantage, had quantified the reduction in disadvantage and provided independent evidence.

3.19 Essentially, the scores awarded against criterion 2 were a measure of the extent to which applicants had demonstrated that their infrastructure project was needed by their region. The program’s objective as set out in the program guidelines included supporting investment ‘in priority infrastructure’. Other statements of government policy used the phrase ‘building needed infrastructure’. The assessment of applications against criterion 2 helped achieve this.

3.20 The assessment against criterion 2A may have also partially contributed to achieving the program’s objective to ‘particularly [support] disadvantaged regions’. The National Stronger Regions Fund’s policy defined ‘disadvantaged regions’ as being those with low socio-economic circumstances and higher than average unemployment. Yet criterion 2A did not adopt this definition. There was potential to improve the design and implementation of the criterion so that it explicitly gave priority to projects located in regions with these characteristics and so maximise the achievement of the underlying policy intent. This matter is examined further in Chapter 5 at paragraphs 5.11 to 5.16, with a related ANAO audit recommendation at paragraph 5.17.

3.21 There are parallels here with the findings of the ANAO’s performance audit of the Bridges Renewal Programme, which was also administered by DIRD. The audit report was published shortly after round two of the National Stronger Regions Fund was completed and its findings included:

The purpose of the assessment process is to identify and recommend for funding those proposals that will provide the greatest value with money in the context of the programme’s objectives. The Bridges Renewal Programme originated from a call for federal assistance to address the backlog of old and unsafe local bridges that were beyond the financial capacity of Councils to repair or replace. Missing from round one was a criterion and/or assessment process that explicitly identified and prioritised proposals with these characteristics. As a result the mix of projects that scored most highly, and so were approved for funding, was not focused towards such proposals and so did not maximise the achievement of the programme’s objectives.11

Criterion 3 (partnerships)

3.22 To be eligible in round two, the funding amount requested had to be at least matched by cash contributions from the applicant and/or other partners. The inclusion of merit criterion 3 encouraged applicants to source contributions in excess of the minimum required and to seek support from multiple partners. On average, eligible applications involved two project partners in addition to the Australian Government and $1.82 in cash contributions for every $1 of grant funding sought. A third of the applications had also secured in-kind contributions to the project.

3.23 Specifically, criterion 3 assessed ‘the extent to which the project increases investment and builds partnerships in the region’. Scores were awarded following calculation of the:

- extent to which the cash contributions exceeded the required 50 per cent;

- in-kind contributions to the project, with a higher weighting given if the value assigned the contribution had been substantiated; and

- number of project partners, with provision to reward the building of non-financial partnerships in the region where significant.

3.24 It would not have been appropriate to score an application below the value with relevant money threshold if it had made the minimum contribution required. Accordingly, all eligible applications were awarded a score of at least three. The 186 eligible applications (43 per cent) that achieved a score of four against criterion 3 had secured significantly more contributions than the minimum required or had several funding partners. The 70 eligible applications (16 per cent) that achieved a score of five had offered both of these.

3.25 The assessment of applications against criterion 3 therefore contributed to the objective of ‘supporting investment in priority infrastructure’. It also contributed to achieving the desired program outcome of ‘improved partnerships between local, state and territory governments, the private sector and community groups’.

Criterion 4 (viability and sustainability)

3.26 Criterion 4 assessed ‘the extent to which the project and applicant are viable and sustainable’. To achieve a score of three or higher, applications needed to have a risk profile that was acceptable to the Australian Government and to have at least satisfied each of the following components:

- project viability, which addressed the program’s objective to ‘fund investment ready projects’ and included consideration of the project planning, design, costing and approval documents;

- project sustainability, which included consideration of how the infrastructure would be maintained into the medium term; and

- applicant viability, which assessed the applicant’s financial position.

3.27 There were 113 eligible applications (26 per cent) scored below the value-with-relevant-money threshold against criterion 4—more than any other single criterion. Most commonly, they had been assessed as not satisfying the project viability component. On 14 occasions the department had also identified risks associated with the project that could not be mitigated through the funding agreement. Criterion 4 helped ensure that projects selected for funding would be delivered and the resulting infrastructure maintained, and so achieve the expected benefits and value with relevant money on which the approval was based.

No assessment of the viability of significant third-parties

3.28 According to the program guidelines, a reason for assessing applicant viability was to determine ‘whether the applicant has sufficient funds to meet its obligations, fund any cost overruns and maintain the project in the medium term’. Determining whether the applicant has sufficient funds is of limited value in arrangements where a third-party is to deliver the project, fund any cost overruns and then own and maintain the resulting asset. The financial obligations of the third-parties undertaking projects could be significant—one private company was contributing $51.2 million to an approved round two project. The department neither assessed the viability of significant third-parties nor requested information that would have enabled it to do so.

3.29 To illustrate the nature of arrangements where consideration of the viability of the third-party and associated risks to the project would be prudent, there were five applications approved for a total of $23.6 million in round two with the following characteristics:

- they were submitted by Councils making no financial contribution to the projects;

- involved non-government partners that were ineligible to apply for the funding in their own right; and

- the partners were responsible for undertaking the projects, making financial contributions totalling $78.6 million or 77 per cent of the project costs, covering any cost overruns and then maintaining the resulting assets.

3.30 At the request of the Minister, the round three guidelines introduced a new requirement that consortiums be led by an eligible applicant that has a financial or in-kind commitment to the project. This did not negate the benefits of considering the viability of significant third-parties and associated risks, as illustrated by the following comparison of a round two application with a round three application for the same project:

[Private company], in its own right, is ineligible to lodge an application for funding under the NSRF, as the applicant must either be a Local Government Authority or a not-for-profit organisation.

[Private company] has requested Council to enter into a joint venture with it for the purposes of submitting an application for a grant from the NSRF for the Project.

- In round two, the Council that submitted the application was making no cash or in-kind contribution to the project. Its partner would undertake the project and was responsible for 50 per cent of the total project costs, any cost overruns and maintaining the asset. The relationship between the partners was set out in an agreement, which explained:

- In its round three application, the Council was still not making a cash contribution but was making an in-kind contribution it valued at $0.1 million and so fulfilled the new eligibility requirement. The partner was responsible for 54 per cent of the total project costs, any cost overruns and for maintaining the resulting asset.

3.31 The ANAO has previously raised concerns about the insufficient management of risks associated with third-party involvement in infrastructure projects by DIRD and its predecessor agencies. In this context the ANAO has also previously observed that ‘as it is expected that the eligibility requirements will reflect the policy objectives of the granting activity, it is questionable whether having an ineligible party as the key beneficiary of the funding would fulfil those objectives’. This observation applies equally to round two of the National Stronger Regions Fund.12

Was the assessment work conducted to a high standard?

The assessment work was conducted to a high standard. Assessors were well trained and supported. Their findings were quality assured by experienced officers, which added considerably to the consistency of assessments. The assessments were transparent, with a clear audit trail of the process and results maintained.

3.32 DIRD was responsible for assessing the round two applications to determine their eligibility, merit and value with relevant money. Assessment teams were established, comprising a mix of officers from the program area, officers drawn from elsewhere in the department and temporarily contracted staff. Assessors completed a five day training program involving a combination of on-line, face-to-face and practical exercises. They were provided a comprehensive suite of guidance materials specific to round two, including a procedures manual, an assessment guide, an eligibility assessment worksheet, and merit criteria assessment worksheets and spreadsheets. Consistent with the implementation of a previous ANAO audit recommendation, the assessment guide and worksheets articulated benchmarks and standards to inform the judgment of assessors when considering the extent to which an application had met the merit criteria.13

3.33 For each eligible application:

- an assessor undertook and recorded the assessment;

- an assessment team leader guided and reviewed their work; and

- a director quality assured the results, recording and justifying any changes made to the scores.

3.34 To inform the assessment of more complex applications, DIRD procured the services of a specialist firm through a competitive process. The firm undertook the preliminary assessment of 152 applications against criterion 1 (economic growth) and of five applications against the applicant viability component of criterion 4 (viability and sustainability). The firm’s findings were provided to the assessors for consideration.

3.35 DIRD also sought input from relevant State/Territory and Australian Government agencies. Specific questions posed to the agencies related to their prior history with the applicant in delivering projects, whether they had any comments on the viability of the project and applicant, the extent to which the project aligned with their priorities, and confirmation of any funding commitments they had made to the project. Input was received for 290 of the 430 eligible applications (67 per cent) and was primarily used to inform the assessment of criterion 4.

Complexity of the merit assessments

3.36 Assessing the individual and relative merits of National Stronger Regions Fund applications was relatively complex. The nature of the infrastructure proposed in round two varied greatly. There was the construction of a solar farm, airport terminal, concrete dam, motor racing circuit and marine rescue tower. There were upgrades to intersections, swimming pools and the storm water drainage system at a business park. The installation of a shade structure over a bowling green, a roof over a saleyard and a fire sprinkler system at a hostel for the aged.

3.37 The size of the projects also varied greatly. Ranging from an application seeking $22 400 towards a $44 800 improvement to the lighting and irrigation of a soccer pitch, to an application seeking $10 million towards the construction of $97.6 million performing arts and cultural facility. Consistent with the principle of proportionality outlined in the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines, the extent of the documentation requested from applicants varied according to the amount of funding requested. Assessors were instructed to consider whether the evidence provided and benefits claimed by applicants were commensurate with the size, scope and nature of the project. Benchmarks were included in the guidance to assist assessors and aid consistency.

Transparency and consistency of assessment

3.38 The assessments were transparent, with a clear audit trail maintained. The assessment process was well documented. The assessment findings and scores were clearly recorded and authorised. These were subsequently presented to the Ministerial Panel to inform its decision making. In addition, to inform the feedback provided to unsuccessful applicants, the assessors had noted specific areas where each application could have been improved. To inform the negotiation of funding agreements with successful applicants, they had also recorded any risks and mitigation strategies identified.

3.39 Applications were assessed consistently against criterion 3 by virtue of the assessment guidance and method. The guidance also went a long way towards promoting consistency of assessments against criteria 1, 2 and 4. But it is the strength of the quality assurance process that gave the greatest confidence that these criteria were applied consistently. A quarter of the applications had their scores against one or more of these criteria adjusted at quality assurance stage and the reasons recorded. The quality assurance was undertaken by two experienced directors with detailed knowledge of the program and of related government policies.

Was the administrative cost of the assessment phase reasonable?

The administrative cost of the assessment phase was reasonable and equated to 0.5 per cent of the funding awarded under round two.

3.40 DIRD advised the ANAO that it incurred National Stronger Regions Fund administrative costs totalling $1.36 million between round two opening for applications on 15 May 2015 and funding advice being provided to the Ministerial Panel on 28 October 2015.14 The assessment phase was completed in accordance with the schedule published in the program guidelines.

3.41 Benchmarks against which to reliably measure the cost-efficiency of grants administration are not readily available. The ANAO therefore compared the administrative cost of the round two assessment phase with the cost of the same round of the predecessor program. The ANAO used information collected during a previous audit, in which DIRD had estimated the costs for round two of the Regional Development Australia Fund at $1.26 million.15 As indicated by Table 3.2, the National Stronger Regions Fund costs compared favourably.

Table 3.2: Comparison of costs to administer infrastructure program funding rounds

|

|

Round two Regional Development Australia Fund (2012 dollars) |

Round two National Stronger Regions Fund (2015 dollars) |

|

Approximate cost of administering the round |

$1.26 million |

$1.36 million |

|

As an average cost per application submitted |

$8296 |

$2642 |

|

As an average cost per grant awarded |

$27 413 |

$12 232 |

|

As a percentage of total funding approved |

0.6% |

0.5% |

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD data.

3.42 Overall, the administrative cost of the assessment phase was reasonable, given:

- 514 applications containing over 9500 supporting documents were assessed;

- the timeliness, quality and complexity of the assessment process;

- DIRD used a competitive procurement process to engage the services of the specialist firm that assisted in the assessment of more complex applications; and

- the favourable comparison with round two of the predecessor program.

4. Funding advice and decisions

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the advice provided to the Ministerial Panel on the merits of competing applications and the funding decisions then taken.

Conclusion

The Ministerial Panel was appropriately advised and given a clear funding recommendation. There was a clear line of sight from the results of the department’s assessment of eligible applications against the merit criteria, the department’s selection of 104 applications for funding recommendation, the Ministerial Panel’s reassessment of 28 applications, through to the approval of 111 applications in round two. Internal documentation recording funding decisions, and their reasons, has been further improved by the department but its responses to Parliamentary scrutiny when questioned about its input to those funding decisions were not transparent (this issue has arisen previously).

Area for improvement

DIRD would benefit from implementing a control framework to ensure decision-makers are advised of the legislative authority for proposed grants and that the legislative authority accurately reflects the nature and scope of the granting activity at the time.

Was the Ministerial Panel appropriately advised and given a clear funding recommendation?

The Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD) appropriately advised the Ministerial Panel on the individual and relative merits of competing applications. DIRD made a clear recommendation that 104 applications be funded for a total of $266.5 million. The selection of applications for funding recommendation was based on their position on DIRD’s order of merit list and, in some cases, on the amount of funding they had requested. The advice was consistent with implementation of previous ANAO recommendations and complied with all but one of the mandatory briefing requirements—it had not informed Ministers of the legal authority for the proposed grants.

4.1 A Ministerial Panel was established to select National Stronger Regions Fund applications for funding. For round two, the Ministerial Panel comprised the:

- Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development (as Chair);

- Assistant Minister to the Deputy Prime Minister;

- Minister for Territories, Local Government and Major Projects; and

- Assistant Cabinet Secretary (as representative of the Prime Minister).

4.2 DIRD provided written advice to the Ministerial Panel on their obligations as decision-makers and on the individual and relative merits of competing applications. The written advice was clear, comprehensive, accurate and timely. It was provided in late October 2015—three months after applications had closed and as per the schedule published in the program guidelines.

4.3 The written advice was consistent with implementation of previous ANAO recommendations for DIRD to provide advice that:

- clearly outlines to decision makers the basis on which it has been assessed whether each application represents value for money in the context of the published program guidelines and program objectives;

- clearly and consistently establishes the comparative merit of applications relative to the merit criteria and includes a high-level summary of the assessment results of each application; and

- aligns the assessment results of each application with its position on the order of merit for funding recommendation.16

Legal authority for the proposed grants

4.4 The Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines set out minimum briefing requirements that apply where a Minister is the grant approver. The written advice DIRD provided in round two complied with these briefing requirements except for the requirement to advise the Minister of the legal authority for the grant.

4.5 The Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines state that ‘the advice must, at a minimum … provide information on the applicable requirements … including the legal authority for the grant’. It also states that, ‘before entering into an arrangement for the proposed commitment of relevant money, there must be legal authority to support the arrangement’. These requirements reflect that, in Williams v Commonwealth of Australia [2012] HCA 23, a majority of the High Court held that legislative authority is necessary for certain spending by the Commonwealth and that appropriation legislation was not sufficient.

4.6 Early in the program’s establishment phase, DIRD arranged for the National Stronger Regions Fund to be included in Schedule 1AB of the Financial Framework (Supplementary Powers) Regulations 1997 as Item 62 of Part 4. Item 62 states that the National Stronger Regions Fund’s objective is: ‘To provide grants to support the construction, expansion and enhancement of infrastructure across regional Australia’.

4.7 It was subsequently a decision of government that the National Stronger Regions Fund not be restricted to regional initiatives. DIRD reflected this decision in the design and implementation of the program. But it did not also ensure it was reflected in the legislative authority. The scope of the program as worded in the legislation was limited to ‘regional Australia’ and so did not extend to the grants awarded in metropolitan Australia. Under the three funding rounds, 51 grants totalling $189.2 million were approved for infrastructure projects in major cities.17 This equates to 30 per cent of the total funding awarded under the program.

4.8 Under Finance’s policy framework, where legislative authority for a spending activity is in the Financial Framework (Supplementary Powers) Regulations 1997 that existing authority cannot be relied upon when an activity changes significantly and new authority is required. It is a matter for non-corporate Commonwealth entities to determine whether a change to a spending activity is significant using their own judgement and knowledge of the activity. A significant change to an activity may include a change in the purpose; a change in the scope (including national applicability); a change in target groups and eligibility criteria; a change in service delivery methods; or a change in administration methods.

4.9 The ANAO’s analysis is that DIRD should have sought an amendment to the legislation to reflect the change in the National Stronger Regions Fund’s scope. There would be benefit to DIRD implementing a control framework to ensure that it advises decision-makers of the legislative authority for proposed grants and that the legislative authority accurately reflects the nature and scope of the granting activity at the time.

Funding recommendation

4.10 DIRD provided clear advice with respect to each of the 514 applications submitted in round two, as summarised in Table 4.1. This included ranking in order of merit the 283 applications it had assessed as offering value with relevant money and recommending that 104 of these be funded for a total of $266.5 million.

Table 4.1: Summary of Department’s advice with respect to each application

|

Department’s advice |

Number of applications |

Total funding requested |

|

‘Value with Relevant Money Recommended for Funding’ |

104 (20%) |

$266.5m |

|

‘Value with Relevant Money’ |

179 (35%) |

$524.1m |

|

‘NOT Value with Relevant Money’ |

147 (29%) |

$423.6m |

|

Ineligible |

83 (16%) |

$252.4m |

|

Withdrawn by applicant |

1 (0.2%) |

$1.3m |

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records.

4.11 The selection of applications for funding recommendation was consistent with the competitive merit-based process set out in the program guidelines. Applications were selected based on their position on DIRD’s order of merit list and, in some cases, on the amount of funding they had requested. The program guidelines had advised that $25 million would be quarantined for those applications assessed as offering value with relevant money that were seeking funding of $1 million or less.18 Specifically:

- DIRD selected the 57 applications at the top of its order of merit list that had achieved an overall score of 31 or above. These were recommended for $239.8 million, of which $11.5 million was for 15 applications seeking funding of $1 million or less; and

- to satisfy the $25 million quarantine, DIRD also selected the 47 applications that had achieved an overall score of 28 to 30 inclusive and that were seeking funding of $1 million or less.19 These were recommended for $26.7 million.

4.12 There were sufficient applications of merit for DIRD to select from, with the 104 recommended applications being strong performers. For example, each had achieved a score of at least four out of five against key policy criterion 1 (economic growth). DIRD noted in its advice to the Ministerial Panel that, if the recommended applications were approved, the funds remaining would enable a further two rounds of approximately $250 million each.

Alternative options

4.13 A challenge DIRD faced in formulating its funding recommendation was that it had not been decided how much of the $787.7 million available at the time would be allocated under round two. In this context, the department suggested alternative options should the Ministerial Panel decide to select a greater number of applications for funding than had been recommended. Consistent with a competitive merit-based selection process, each option involved funding all applications down to a specific point on the department’s order of merit list.

Were the funding decisions consistent with a competitive merit-based selection process?

The funding decisions taken were consistent with the competitive merit-based selection process set out in the program guidelines. The Ministerial Panel considered the department’s advice, reassessed 28 of the applications against the merit criteria, and then selected 111 applications for funding totalling $293.4 million. The applications were selected based on their position on the Ministerial Panel’s order of merit list and, in some cases, on the amount of funding they had requested.

4.14 DIRD provided its advice to the Ministerial Panel on 28 October 2015. The funding decisions were announced on 7 December 2015. The decision-making process included:

- the Ministerial Panel considering the advice provided, forming its own conclusions as to the individual and relative merits of applications, and then selecting 111 applications for funding totalling $293.4 million;

- the Ministerial Panel, as required, consulting with the National Infrastructure Committee,20 which noted the projects the Ministerial Panel proposed to fund; and

- for each of the 111 applications selected, a member of the Ministerial Panel approving the proposed expenditure of relevant money in a manner that complied with section 71 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and with the requirements for Ministers set out in the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines.

Ministerial Panel’s assessment and selection of applications

4.15 The Ministerial Panel was adequately informed, and made reasonable inquiries, to fulfil its decision making responsibilities. It considered DIRD’s written advice and then, on three occasions, requested additional information. This included requesting additional information about 25 of the applications and about the department’s assessment of criterion 2 (disadvantage).

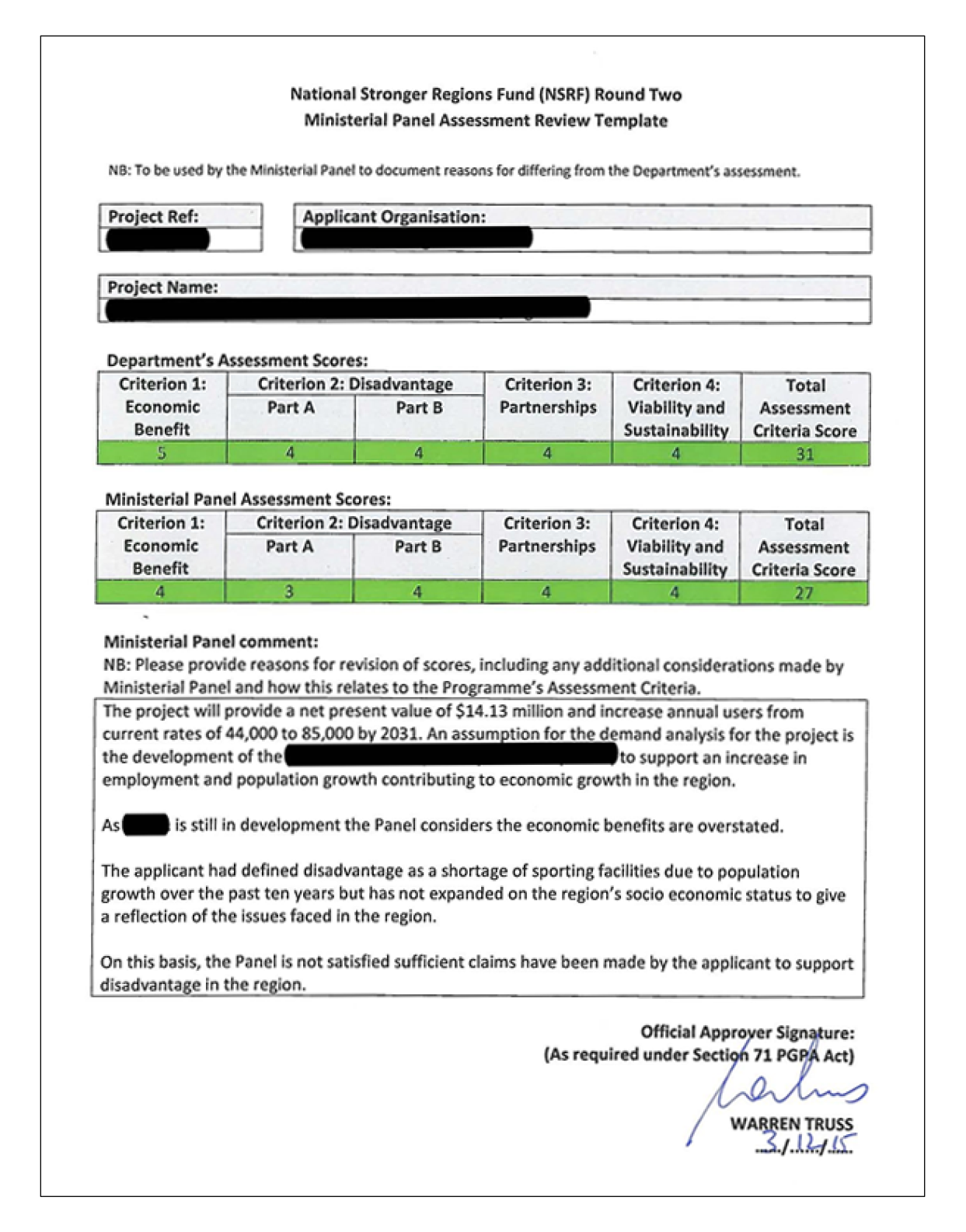

4.16 Different conclusions can often be legitimately drawn from the same set of information. The Ministerial Panel formed a contrary view to DIRD’s assessment of 28 of the 430 eligible applications (seven per cent) and rescored them against one or more of the merit criteria. The original scores, the revised scores and the basis for the Ministerial Panel’s view were clearly recorded and authorised on a ‘Ministerial Panel Assessment Review Template’. The recorded bases were specific to the application, relevant to the merit criteria and supported by the information DIRD had provided. Examples of completed templates are at Appendix 1 of this report.

4.17 The rescoring resulted in five applications moving up the order of merit list and 23 moving down.21 The Ministerial Panel then selected applications for funding based on their position on the revised order of merit list and, in some cases, on the amount of funding they had requested. As illustrated in Table 4.2:

- the Ministerial Panel selected the 89 applications at the top of the revised order of merit list that had achieved an overall score of 29 or above. These were approved for $280 million, of which $22.3 million was for 37 applications seeking funding of $1 million or less; and

- to satisfy the $25 million quarantine, it also selected the 22 applications that had achieved an overall score of 28 and that were seeking funding of $1 million or less. These were approved for $13.4 million.

Table 4.2: Results of the Department’s and of the Ministerial Panel’s assessment and selection of eligible applications in round two

|

|

|

Department’s assessment |

Ministerial Panel’s assessment |

||||

|

Score |

Sizea |

# |

Amount |

Recommended |

# |

Amount |

Approved |

|

31–35 |

Med–Large |

42 |

$228.3m |

Yes |

34 |

$169.2m |

Yes |

|

Small |

15 |

$11.5m |

Yes |

13 |

$9.6m |

Yes |

|

|

30 |

Med–Large |

10 |

$63.1m |

|

7 |

$33.7m |

Yes |

|

Small |

10 |

$5.2m |

Yes |

9 |

$4.6m |

Yes |

|

|

29 |

Med–Large |

16 |

$86.8m |

|

11 |

$54.8m |

Yes |

|

Small |

15 |

$8.1m |

Yes |

15 |

$8.1m |

Yes |

|

|

28 |

Med–Large |

14 |

$74.4m |

|

13 |

$72.4m |

|

|

Small |

22 |

$13.4m |

Yes |

22 |

$13.4m |

Yes |

|

|

21–27 |

Med–Large |

61 |

$263.8m |

|

70 |

$315.2m |

|

|

Small |

78 |

$36.0m |

|

80 |

$37.6m |

|

|

|

Not value for money |

All sizes |

147 |

$423.6m |

|

156 |

$495.6m |

|

Note a: ‘Small’ denotes a request for funding from $20,000 through to $1 million and ‘Med–Large’ denotes a request for more than $1 million through to $10 million.

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records.

4.18 Consistent with a competitive merit-based selection process, there was a clear alignment between the selection of applications for funding and the results of the Ministerial Panel’s assessment of each eligible application against the published merit criteria. The $25 million quarantine set out in the program guidelines also influenced the selection of applications in the manner intended.

4.19 The Government’s 2016 federal election commitment to refocus the National Stronger Regions Fund to become the Building Better Regions included the statement, ‘A $500,000 project should not be competing with a $20 million project for funding’.22 Smaller-value projects had been underrepresented in the round one decisions of the National Stronger Regions Fund. This was successfully resolved with the introduction of the $25 million quarantine, which meant that smaller-value projects were not competing against larger ones for a portion of the funding. As outlined in Table 4.3, eligible applications seeking $1 million or less were relatively more successful than larger projects in round two and were considerably more successful in round three.

Table 4.3: Success rates of eligible applications by amount of funding requested

|

Funding round |

Applications for $1 million or less |

Applications for more than $1 million |

||

|

|

Number approved |

Success rate |

Number approved |

Success rate |

|

Round one |

12 of 118 |

10% |

39 of 153 |

25% |

|

Round two |

59 of 210 |

28% |

52 of 220 |

24% |

|

Round three |

46 of 170 |

27% |

21 of 197 |

11% |

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records.

Comparison of funding advice with decisions taken

4.20 Overall 80 per cent of the applications, and 64 per cent of the funding, approved under round two were as recommended by DIRD.

4.21 DIRD had recommended the 104 applications it categorised as ‘Value with Relevant Money Recommended for Funding’ for a total of $266.5 million. The Ministerial Panel selected 89 of these (86 per cent) for funding totalling $187.2 million. The Ministerial Panel disagreed with DIRD’s assessment of the other 15 recommended applications, reducing their scores against merit criterion 1, 2A and/or 2B and rejecting them for funding. In summary, the Ministerial Panel rescored:

- five applications on the basis that there was insufficient evidence that the economic benefits would be realised;

- four applications on the basis that the economic benefits were overstated;

- three applications on the basis that the project was unlikely to address the claimed disadvantage;

- two applications on the basis that both the economic benefits and disadvantage were overstated; and

- one application on the basis that the disadvantage was overstated.

4.22 DIRD had assessed a further 179 applications as offering ‘Value with Relevant Money’ but had not recommended them for funding. The Ministerial Panel selected 20 of these applications (11 per cent) for approval.

4.23 Against 17 of the 20 applications selected, the Ministerial Panel recorded that it agreed with the department’s assessment. Each had been awarded an overall score of either 29 or 30 but had not been recommended by DIRD on the basis that they were seeking more than $1 million (called ‘Med–Large’ applications in Table 4.2). The Ministerial Panel selected these 17 applications for funding totalling $82.6 million, along with all other applications on its merit list that had an overall score of 29 or above.

4.24 The Ministerial Panel recorded its disagreement with DIRD’s assessment of the other three of the 20 applications selected from the ‘Value with Relevant Money’ category. The Ministerial Panel had increased the scores against:

- criterion 1, 2A, 2B and 4 for the ‘Northern Rivers Livestock Exchange Redevelopment’ in Casino, which raised its overall score considerably from 26 to 32, and selected it for $3.5 million;

- criterion 2A for the ‘Bourke Small Stock Abattoir Development Project’, which raised its overall score from 30 to 31, and selected it for $10 million; and

- criterion 1 for ‘The Hamilton Regional Livestock Exchange Up-grade’, which raised its overall score from 28 to 31, and selected it for $1.99 million.