Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Design and Implementation of the First Funding Round of the Bridges Renewal Programme

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development’s design and implementation of the first funding round of the Bridges Renewal Programme.

Summary and recommendations

1. Following the 2013 change of government, the Bridges Renewal Programme was established to deliver on a Coalition election commitment. Specifically, to allocate $300 million, matched dollar for dollar, to renew and upgrade deteriorating local bridges that are often beyond the financial resources of Councils. The funding was to be allocated on a transparent, competitive basis, giving priority to community needs and economic return.

2. The programme is administered by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD). The programme design work was undertaken between December 2013 and June 2014. The first funding round was to focus on those projects ready to commence construction in 2014–15. It opened on 1 July 2014 and attracted 267 proposals from State government and Councils.1 In February 2015, the Minister selected 73 proposals for funding totalling $114.8 million.

3. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DIRD’s design and implementation of the first funding round of the Bridges Renewal Programme.

Conclusion

4. DIRD continues to make improvements to its internal processes for the conduct of competitive funding rounds. But the design and implementation of the Bridges Renewal Programme took too long (14 months). This contributed to less than 20 per cent of approved projects commencing construction in 2014–15, despite the round’s intended focus on construction-ready projects.

5. There was mixed performance in terms of achieving the programme objectives. On a positive note, the results of the first round mean the programme is on track to deliver the desired investment of at least $600 million.

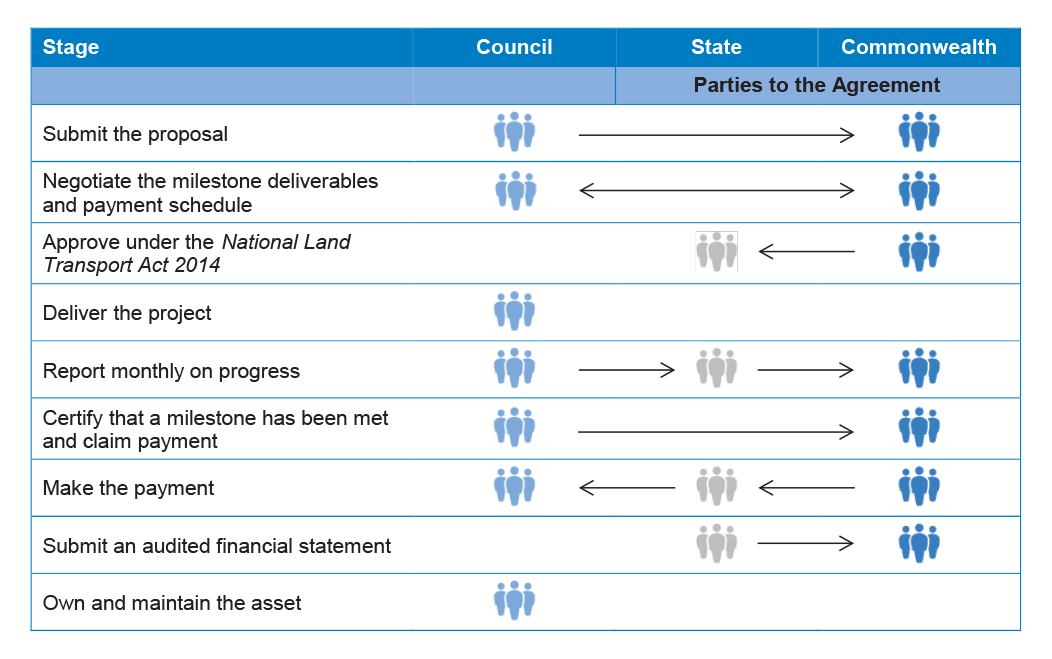

6. Critically, although the programme had both productivity and community access objectives, projects seeking to improve community access were disadvantaged in the application and assessment approach and so they were less successful in obtaining funding. In addition, notwithstanding the policy rationale for the introduction of a bridges renewal programme, the assessment approach did not include consideration of the applicant’s relative need for financial assistance, the condition of the existing bridge or urgency of its repair.2 While the department had recognised the productivity benefits of bridge works, it otherwise lost sight of the Australian Government’s intentions for a programme that would address the backlog of deteriorating local bridges that were beyond the financial resources of Councils to renew.3

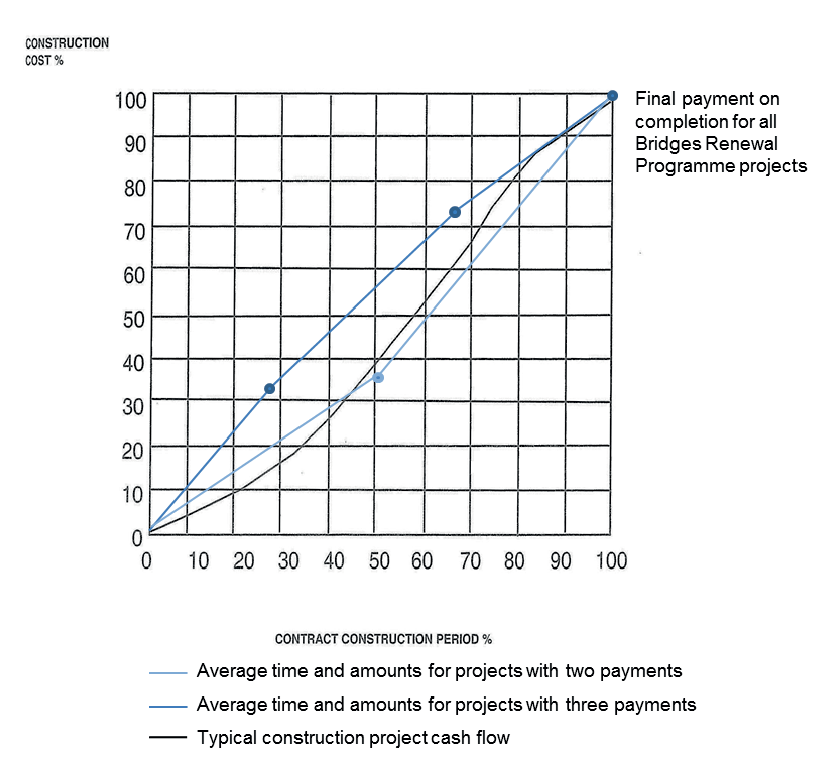

Supporting findings

Application and assessment process (Chapter 2)

7. A competitive application-based process was used, which promoted transparent and equitable access to the funding opportunity. The number of proposals received represented a healthy level of competition for the available funding. The large majority (96 per cent) of the 267 proposals received were assessed as eligible. Although, greater attention still needs to be paid by DIRD to documenting the basis for assessing a proposal as eligible when the available evidence indicates that it does not meet a requirement.

8. The method used to score the 255 eligible proposals against the merit criteria, and to rank them in order of value for money, was consistently and transparently applied. But the scores awarded were not sufficiently reliable as indicators of project merit in the context of the programme’s objectives. Of particular note was that the round one arrangements did not include a mechanism for scoring proposals according to the relative need for financial assistance or condition of the existing bridge.

9. Further, in order to achieve the desired objectives of funding programmes, DIRD must:

- better align eligibility requirements with programme objectives;

- ensure that the design and application of the merit criteria encompass all key objectives and the underlying policy rationale for the programme; and

- recognise that smaller value projects should be expected to deliver fewer benefits than higher value projects, and should not be disadvantaged in the selection process for this circumstance.

Advice and funding decisions (Chapter 3)

10. There was a clear alignment between the department’s funding recommendations and its underlying assessment work. The Minister’s funding decisions were consistent with his department’s advice on each proposal’s merit and value for money. The funding decisions were appropriately recorded.

Funding arrangements (Chapter 4)

11. Funding for approved projects is delivered under the federal financial relations framework. That framework was appropriate for those projects being delivered by State agencies. It is not well suited to administering funding for Council-delivered projects. This is because it introduces an intermediary (the State) between the applicant/project deliverer (the Council) and the funding provider (the Commonwealth). DIRD took worthwhile steps to manage some of the risks involved but it should have consulted more with State agencies before implementing an arrangement dependent on the States taking on Commonwealth administrative functions.

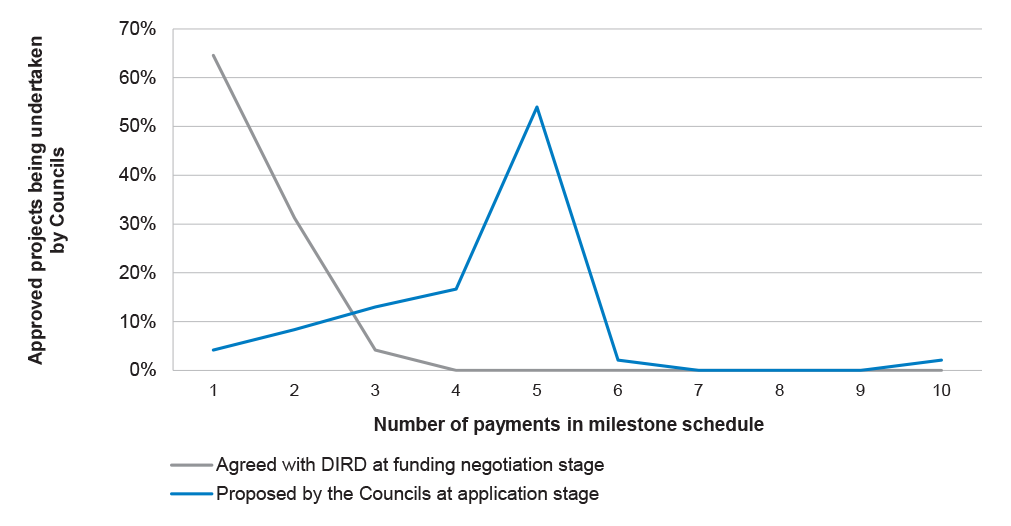

12. The payment strategy appropriately safeguarded Commonwealth funds and was improved compared with a number of infrastructure funding programmes previously examined by the ANAO. There remains scope to further improve the linking of milestone payments to cash flow requirements, so as to ensure projects remain viable and programme objectives are achieved.

13. The funding arrangements included a mechanism for collecting relevant, comparable data on project outputs and outcomes. This data will support the implementation of the monitoring and evaluation strategy developed for the Bridges Renewal Programme.

Achieving objectives (Chapter 5)

14. The department has not set any public performance measures that are specific and tailored to the Bridges Renewal Programme. Rather, as it is able to do under the new performance framework established by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, the department’s performance measurement is undertaken at a broader level than individual programmes such as the Bridges Renewal Programme.

15. DIRD put in place mechanisms that helped ensure that approved funding would be matched dollar for dollar and generate the desired net increase. The extent to which the programme itself will generate an additional $300 million in Commonwealth funding for bridge projects has been somewhat offset by the concurrent decision to make bridge projects ineligible under round four of the Heavy Vehicle Safety and Productivity Programme. This removed a funding avenue that had been available for bridge projects since 2008–09, redirecting such proposals to the Bridges Renewal Programme.

16. Consistent with the programme’s origins, the Minister requested that the capacity of the proponent to pay be a consideration in project selection. To give effect to the Minister’s request, DIRD requested relevant information from Council applicants. The department did not then use this information to influence its funding recommendations to the Minister. This contributed to the funding round result whereby the majority of the approved funding (66 per cent) went to State agencies, with those Councils with a low rate base being no more successful than other Councils at attracting funding.

17. The bulk of the available funding was awarded to projects likely to deliver the desired outputs of renewed, replaced and upgraded bridges. Of particular concern is the four per cent ($4.8 million) of funding awarded to construct new bridges where no bridge had previously existed—an output at odds with the programme’s intent. The projects recommended and selected for funding predominately sought to increase productivity, as opposed to those seeking to improve community access. The population of projects selected did not therefore maximise the achievement of the programme’s two-fold objective.

18. There was a 14 month period between the policy decision to establish the programme being formalised in December 2013 and the results of round one being announced in February 2015. This left little time remaining in 2014–15 for funding arrangements to be negotiated and construction to commence. Ultimately, 14 (19 per cent) of the 73 projects selected commenced construction in 2014–15; five of which were subsequently assessed as ineligible for starting before the decisions had been announced.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Para 4.18 |

When a funding arrangement is dependent on State/Territory agencies undertaking functions on behalf of the Commonwealth, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development negotiate and agree roles and responsibilities with each agency during the design stage. DIRD’s response: Agreed with qualification. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Para 5.45 |

For optimum outcomes, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development link programme criteria and their application more clearly to the specific objectives of, and underlying policy rationale for, each funding programme. DIRD’s response: Agreed with qualification. |

Summary of entity response

19. The proposed audit report was provided to DIRD and the Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development. A formal response to the proposed audit report was received from DIRD. The full response is at Appendix 1 and the summary response is as follows:

The Department welcomes the ANAO’s positive comments on the Department’s continued improvements to the application and assessment process, as well as the link between funding decisions and advice. In addition, the ANAO has noted that the Department has linked reporting and milestone payments to the release of Commonwealth funds.

Alternately, the ANAO has commented that the assessment criteria are not sufficiently aligned with programme objectives. The assessment criteria were intended to capture likely quantifiable ‘outcome’ information and allow clearer identification of the relative merit of applications, which in turn would inform an assessment of value for money. Applications with insufficient quantifiable information received low scores. The Department has undertaken a number of activities to improve the quality of applications.

The Department disputes the ANAO’s assertion that construction of new bridges was ‘at odds with the programme’s intent’, as new bridges were within the programme objectives.4

20. Relevant extracts of the proposed audit report were also provided to the organisations that submitted the proposals the ANAO has used as examples in the sub-section headed ‘Assessment of need (missing from the criteria)’ at paragraphs 2.39 to 2.46. Relevant comments received have been incorporated into the report.

1. Background

Programme origins

1.1 The Coalition announced during the 2010 federal election campaign its commitment to introduce a Bridges Renewal Programme. The then Shadow Minister for Local Government noted ‘the growing infrastructure problem posed by the gradual decay of the more than 30 000 small road bridges … [which] are key economic assets in connecting local communities to the broader road network and getting people to work and school.’ Further, that ‘some councils have been unable to afford maintenance and upgrades necessary to keep these bridges open’. The proposed programme was to provide $300 million, matched dollar for dollar, to ‘help fix these bridges’.5

1.2 The Australian Local Government Association publicly supported the Coalition’s pledge. One of the priorities for federal funding that had been identified in the Association’s National Local Roads and Transport Policy Agenda 2010–20 was ‘additional funding to address the backlog of timber bridges’.6

1.3 During the 2013 federal election campaign, the Coalition reiterated its commitment to ‘invest $300 million to upgrade the nation’s deteriorating bridges’. Additionally, that ‘the federal funding will be allocated on a transparent, competitive basis, giving priority to community needs and economic return’.7

Programme establishment

1.4 Following the 2013 change of government, the Bridges Renewal Programme was established to deliver on the Coalition’s election commitment. The programme’s objectives are ‘to contribute to the productivity and community access of bridges serving local communities, and facilitating increased productivity by enhancing access to allow for greater efficiency’.

1.5 The programme is administered by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD). A total of $300 million is available over the five years from 2014–15. The funding is to assist States and Councils to renew, replace and upgrade bridges that carry road vehicles on recognised public roads, excluding those situated on the National Land Transport Network.

1.6 The funds are to be allocated via competitive funding rounds. The Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development (‘the Minister’) is responsible for making the funding decisions.

Applicable legislation

1.7 The Minister’s approval of Bridges Renewal Programme funding needed to be in accordance with Section 71 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. The projects selected for funding also needed to be approved as Investment Projects under Part 3 of the National Land Transport Act 2014.8

1.8 The delivery of both State and Council projects is managed through the States under the National Partnership Agreement on Land Transport Infrastructure Projects. Payments made under the National Partnership Agreement are made to States for the purposes of the Federal Financial Relations Act 2009. As a result, the Bridges Renewal Programme is not subject to the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines.

Funding rounds

1.9 Round one of the Bridges Renewal Programme was launched on 18 June 2014 and was expected to provide up to $100 million. The call for proposals opened on 1 July 2014 and closed on 28 August 2014. The department received 267 proposals from States and Councils. DIRD was responsible for checking eligibility, assessing the value for money offered by eligible proposals, and making funding recommendations to the Minister. In February 2015, the Minister selected 73 proposals for funding totalling $114.8 million.

1.10 Round two of the Bridges Renewal Programme opened on 1 July 2015 and closed on 31 August 2015, with $100 million expected to be allocated. When announcing the round, the Minister explained:

Our experience with the first round showed that State Government projects were better able to meet the criteria for the programme. Their projects generally could demonstrate the bigger traffic counts and therefore stronger economic benefits. Last mile local projects could not be competitive. Therefore, this $100 million second round of the Bridges Renewal Programme will be exclusively available to local government.9

1.11 In October 2015, the Minister announced that 270 proposals were received in round two.10

1.12 While arrangements are not yet finalised, it is expected that a third round will be held to allocate the remainder of the available funding.

Heavy Vehicle Safety Productivity Programme

1.13 Round one of the Bridges Renewal Programme was implemented and administered in conjunction with round four of the Heavy Vehicle Safety and Productivity Programme. The objectives of round four were to: increase productivity of heavy vehicles by enhancing the capacity of existing roads and improving connections to freight networks; and improve the safety environment for heavy vehicles drivers. In February 2015, the Minister approved 53 proposals for a total of $96 million under round four.

Audit approach

1.14 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DIRD’s design and implementation of the first funding round of the Bridges Renewal Programme. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the application and eligibility checking processes promoted transparent and equitable access to the available funding;

- the merit assessment process identified and ranked in priority order those eligible applications that best represented value for money in the context of the programme objectives and desired outcomes;

- the Ministerial decision-maker was well briefed on the assessment of the merits of eligible applications, was provided with a clear funding recommendation, and the decisions taken were transparent;

- funding arrangements for approved projects were appropriate for effective ongoing management and also support a programme evaluation framework;

- the distribution of funding was consistent with the programme objectives and with funding being awarded on the basis of competitive merit; and

- programme planning and design was sound, outcomes oriented, met policy and legislative requirements, and supported efficient and effective programme administration.

1.15 The audit also examined the extent to which the round one arrangements reflected implementation of recommendations made in relevant ANAO audit reports tabled over recent years. Specifically, Audit Report No.3 2012–1311, Audit Report No.1 2013–1412 and Audit Report No.9 2014–15.13 This focus was in part a response to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit’s recommendation of August 2015 ‘that the Australian National Audit Office consider prioritising the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development … in its continuing series of audits of agencies’ implementation of performance audit recommendations’.14

1.16 The audit’s scope covered key programme elements of the Bridges Renewal Programme, from the design and implementation of the first funding round to the establishment of the funding arrangements. The audit did not examine the delivery of individual projects.

1.17 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $553 950.

2. Application and assessment process

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the: application and eligibility checking process promoted transparent and equitable access to the available funding; and merit assessment process identified and ranked the eligible proposals that best represented value for money in the context of the programme objectives.

Conclusion

The funding opportunity presented by the Bridges Renewal Programme was well received. This was reflected in a large body of proposals being submitted and assessed as eligible.

DIRD continues to improve its application assessment methods, including taking action in response to previously agreed audit recommendations. More work remains to be done in certain areas, such as documenting the bases for eligibility decisions.

In a number of important respects, the design and application of the merit assessment process did not adequately focus on the programme’s policy underpinnings and its objectives. As a result, aspects of the department’s approach did not promote competition for the available funding. Proposals that were disadvantaged in the assessment process were those:

- focused on improving community access;

- submitted by Councils; and/or

- smaller value projects.

Chapter 5 further analyses the effect of the assessment approach on achieving programme objectives, with a resulting audit recommendation that DIRD link its approach more clearly to the specific objectives of, and underlying policy rationale for, each funding programme. In addition, the ANAO provided feedback to DIRD in August 2015 on ways it could improve aspects of its assessment approaches. As the guidance DIRD developed for the States and for departmental assessors for round two of the Bridges Renewal Programme reflected the ANAO feedback, as well as other lessons learned by the department during the course of round one, we have made no recommendations in Chapter 2.

Was the application process open and competitive?

A competitive application-based process was used, which promoted transparent and equitable access to the funding opportunity. The number of proposals received represented a healthy level of competition for the available funding.

2.1 It was a decision of government that Bridges Renewal Programme funding be allocated through a competitive, merit-based selection process. This was reflected in the design of the application process.

2.2 The opportunity to apply for first round funding was sufficiently publicised to potential applicants, including by the Australian Local Government Association. The process for submitting a proposal was also effectively communicated. The application stage opened on 1 July 2014, with completed Proposal Forms15 to be emailed to DIRD by 11:59pm on 28 August 2014.

2.3 DIRD registered 267 proposals for round one funding, but the register did not include the time and date each was received. ANAO identified that at least six proposals had been submitted after the deadline. Three of these had been submitted within two hours of the closing time and were amongst the 267 proposals registered. The other three proposals did not appear on the register or elsewhere in the programme records. Two of these had been submitted 11 hours late, while the other was nearly three days late. DIRD should have recorded the time and date each proposal was received and, against any late proposals, whether it had been accepted or rejected. If accepted, then the basis for that decision should also have been clearly recorded and been consistent with the principles of equity and probity.

2.4 The round attracted a sufficient number of proposals from across the applicant types. There are around 560 Councils in Australia and 133 of these (24 per cent) participated in round one, submitting between one and 16 proposals each. Councils were responsible for 227 of the proposals submitted (or 85 per cent). Each State and Territory government also participated. They were responsible for the other 40 proposals.

2.5 A total of $306.1 million was requested. The amount sought was three times the $100 million announced as available under round one.

Sufficiency of information obtained from applicants

2.6 An important factor in determining the appropriate application process is the information that will be required in order to verify eligibility, assess merit and inform funding decisions. The design of the Proposal Form gave applicants the scope and flexibility to describe their projects, detail their costings, respond to each merit criterion and attach supporting evidence. Potential applicants were also given access to departmental officers via telephone and email if they required assistance during the application process.

2.7 Nevertheless, in some cases the Proposal Form did not elicit the information required from applicants to demonstrate the merits of their projects.16 This situation contributed to a high proportion of the eligible proposals being assessed by DIRD as not representing value for money (at 71 per cent, as outlined in paragraph 2.24 below). DIRD advised the Minister that these proposals:

… were not as successful in demonstrating their claims and/or there was a lack in justifiable analysis and evidence compared with those proposals that received a higher score … We note that where some of these projects have underlying value, proponents could seek to further develop the arguments and evidence in the proposal and/or undertake further project planning and re-submit these under Round Two.

2.8 DIRD put in place a number of initiatives to help ensure that the information obtained from applicants in round two would be sufficient to reach an informed assessment of their projects’ individual and relative merits. Specifically:

- unsuccessful applicants were offered the opportunity to receive individual feedback via telephone on their round one proposal/s and on how they could further develop any proposals they intended to submit for round two;

- general tips on how to submit Bridges Renewal Programme proposals were included in the National Stronger Regions Fund Roadshow, which was conducted in all capital cities and selected regional centres over May and June 2015; and

- reflecting lessons learned from round one, the Proposal Form issued in round two contained more explicit data fields and guidance.17

Were the eligibility requirements expressed clearly and applied fairly?

An earlier ANAO audit of a funding programme administered by DIRD had identified shortcomings in the recording of eligibility issues.18 Analysis of round one of the Bridges Renewal Programme indicates that greater attention still needs to be paid to documenting the basis for assessing a proposal as eligible when the available evidence indicates that it does not meet a requirement. Further, the approach taken to assessing the eligibility of Bridges Renewal Programme proposals could have been better aligned with the programme objectives.

2.9 All 267 proposals received were checked for eligibility by DIRD and the findings recorded on individual assessment sheets. The checking process resulted in 12 of the proposals (four per cent) being assessed as ineligible and excluded from further consideration. The eligibility requirements and checking procedures were largely sound. Those shortcomings that impacted the degree of transparency, accountability and equity achieved are outlined below.

Requirement that construction commence 2014–15

2.10 An intended eligibility requirement was that the projects be ready for construction to commence in 2014–15. DIRD’s website had advised potential applicants that:

Round One is focused on projects that are well developed, with planning and approvals well advanced so construction can begin in the 2014–15 financial year. Proponents who would like to seek funding but who are not at a construction ready stage should prepare themselves for Round Two which is expected to be announced in mid to late 2015. [ANAO emphasis]

2.11 The Proposal Form also referred to the need for projects to be well developed ‘so construction can commence in the 2014–15 financial year’. The associated eligibility requirement, however, was poorly worded.

2.12 The Proposal Form stated ‘Proponents must demonstrate that projects can commence in 2014–15’ [ANAO emphasis] instead of ‘construction’. ANAO analysis identified that 19 per cent of submitted proposals contained indications that construction was planned to commence after 2014–15.19 During the checking process DIRD amended the requirement to be that project activity (such as designing or tendering) needed to occur in 2014–15. DIRD considered this to be in the interest of fairness to applicants, given the requirement had been ambiguously worded in the material available to potential applicants.

2.13 The decision to amend the eligibility requirement was not clearly documented and authorised at the programme level. It was also not brought to the attention of the Minister.20 Further, the approach adopted was not made transparent in the individual assessment sheets. For example, the following extract from the assessment sheet for a proposal that was ineligible against the intended criterion (given it ‘Proposed to commence construction in 2016/2017’) does not explain why this proposal was found eligible by DIRD:

|

Eligibility Criteria |

Yes / No |

Comments (only provide a comment if there is some doubt about the answer) |

|

Has the proponent demonstrated that project construction can commence in the 2014-15 financial year? |

YES |

|

2.14 While the amended eligibility requirement was equitably applied to all submitted proposals, the situation reduced the extent of the equitable access afforded to potential applicants. Others with proposals at ‘project ready’ stage may have chosen not to apply in round one based on the intended eligibility requirement and on advice that such proposals should instead await round two (see the quote at paragraph 2.10).

2.15 As eligibility criteria are expected to have been derived from programme objectives, amending a criterion is likely to increase the risk that the objectives will not be achieved. It eventuated that 81 per cent of the projects approved in round one (representing 95 per cent of the funding approved) did not commence construction in 2014–15. See further at paragraph 5.54 of Chapter 5.

Eligibility of budget items

2.16 Consistent with the election commitment that the Commonwealth funding would be ‘matched dollar for dollar’, an eligibility requirement was that applicants contribute (or otherwise source) at least half of the total project cost. Assessors checked the project budgets and supporting information to ensure that the amount of funding requested did not exceed 50 per cent and that funds had not been sourced from another Australian Government programme.

2.17 The Proposal Form had stated clearly that ‘Proponent contributions are cash only and in-kind contributions will not be considered’. Nevertheless, a number of proposals contained budget items that were clearly, or potentially, in-kind costs. For example, one proposal included $59 500 for project management to be undertaken in-house. Some proposals also contained budget items that appeared ineligible on the basis of being costs already incurred. For example, the budget for one of the successful proposals included $1.3 million for a design that had already been completed. The department’s planned approach to assessing the eligibility of individual budget items was not clearly documented in the programme records. Nor was the basis for the department’s actual assessment judgments evident given no distinction was made between eligible and ineligible budget items throughout the assessment, funding recommendation or funding negotiation stages.

Eligible project types

2.18 The Proposal Form described the bridge projects eligible for funding under round one as follows:

- The BRP is open to bridge projects carrying road vehicles on recognised public roads.

- Funding is not available for rail bridges; or stand-alone cycleway, pedestrian or stock bridges.

- Bridges situated on the National Land Transport Network are excluded.

2.19 The Proposal Form did not explain that the construction of new bridges—where no bridge previously existed—was an eligible project type. There were seven proposals to construct a new bridge. Each was assessed as eligible and six were ultimately approved for $7.8 million of Commonwealth funding.21 The basis for DIRD’s decision to treat new bridges as eligible was not explained in the departmental records. If it had been clear to all eligible entities that new bridges were eligible for funding, it would be reasonable to have expected the department would have received more than seven proposals to construct a new bridge.

2.20 The information provided to potential applicants did not promote transparent and equitable access to the funding available for such bridges, as it did not clearly state that a ‘renewal’ programme would also fund the construction of new bridges. Assessing proposals to construct new bridges as being eligible also represented a disconnect with the objectives of the programme. This issue is examined further in paragraphs 5.37 to 5.41 of Chapter 5.

2.21 In November 2015, DIRD advised the ANAO that the eligibility of new bridges ‘has been clarified in round two documentation’. The department’s claim that it was clearer in the round two documentation that new bridges were eligible is at odds with the available evidence. The word ‘new’ did not appear in the round two Proposal Form. Further, the Proposal Form advised potential applicants that ‘If you answer NO to any question below the project is NOT eligible for this Round of the BRP’ and then posed the question: ‘Can you confirm all costs are for the replacement and/or renewal of a bridge?’ This implies that new bridges were ineligible, rather than eligible. DIRD advised ANAO that it would ‘consider whether there is further need for clarification/consistency’.

Did the scoring method provide a clear and consistent basis for ranking competing proposals?

DIRD awarded each of the eligible proposals a score out of five against the specified merit criteria. It used the results to identify the proposals that the department considered individually represented value for money and then to rank those proposals in order of their relative value for money. The method was consistently and transparently applied.

2.22 Each of the 255 eligible proposals was assessed against the four merit criteria22 set out in the Proposal Form (see Table 2.1). The merit criteria were equally weighted. The assessment findings were documented and were quality-assured by a second assessor.

Table 2.1: Merit criteria used in round one

|

Criterion |

Description |

|

Criterion 1— Improved Productivity and Access |

The degree to which the project is consistent with the programme objectives. This will include consideration of evidence to support claims relating to how the project: a. facilitates access to services for the local community; b. facilitates integration with key freight networks; c. increases access for higher mass and productivity vehicles; d. facilitates improvements to ‘last mile’ freight logistics (the portion of the supply chain from the final delivery hub to the customer’s door); e. facilitates improvements in the ‘whole of journey’ for freight in the overall supply chain; and f. aligns with industry and community priorities. |

|

Criterion 2— Quantified Benefits |

The degree to which the project provides a level of measurable benefits relative to other proposals. The Department will consider stated benefits and supporting evidence provided by proponents to assess projects relative to other proposals, including: a. Analysis and evidence supporting claimed benefits in terms of: i. capacity for greater efficiency; ii. reduced operating costs; iii. shortened distances travelled; iv. traffic volumes, including proportion of heavy and higher productivity vehicles; and v. community access; b. Benefit-to-cost (BCR) analysis, where available. |

|

Criterion 3—State/Territory Priority |

Project proposals will be prioritised by each state or territory government and higher ranked projects will be assessed by the Department as meeting this criterion to a higher degree. |

|

Criterion 4— Construction Readiness |

The degree to which proposals demonstrate that they can be delivered within required timeframes—commencement in 2014–15 and completion by 30 June 2017. Evidence may include: a. completed planning documents, including preliminary or final design; b. project costings, where possible supported by an independent Quantity Surveyor; c. progress on gaining relevant Development Approvals and other approvals such as environmental, cultural and heritage; and d. identification of any risks and steps for managing those risks, including scope, construction, approvals, financial and delivery. |

Source: Text taken from the Programme Criteria and Proposal Form issued by DIRD for round one.

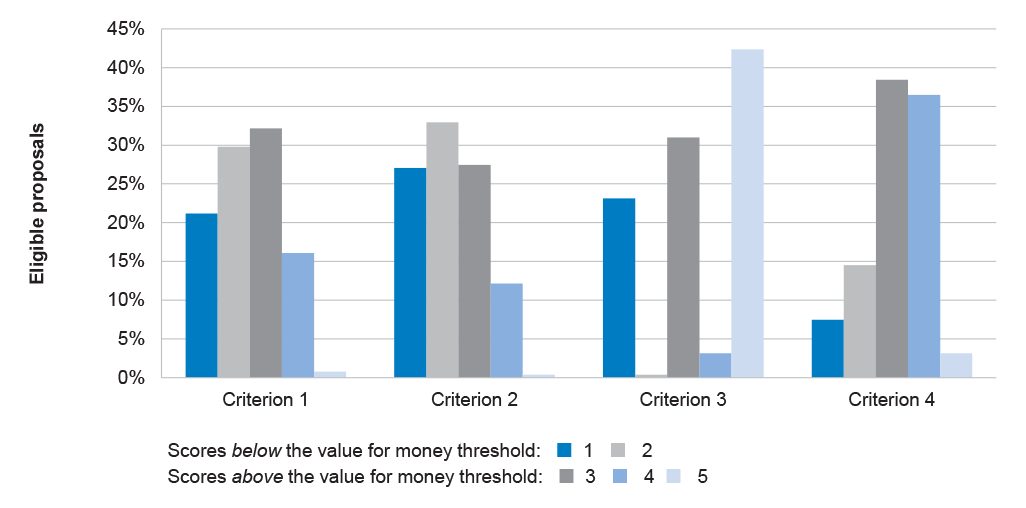

2.23 The departmental assessors awarded each proposal a score out of five against each criterion. Numerical rating scales such as this have distinct advantages over qualitative scales. Its use is consistent with implementation of Recommendation No.1 of ANAO Audit Report No.3 2012–13 and with DIRD’s related undertaking to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit that ‘in future we will use a numerical rating scale of 1 to 5’.23 The distribution of the scores awarded against each criterion is shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Distribution of scores awarded by criterion

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records.

2.24 DIRD used the scores awarded as the basis for assessing whether or not each proposal represented value for money. Proposals that had been scored less than a three out of five against any merit criterion were assessed as not representing value for money. The method reflected the principle that proposals assessed as not satisfactorily meeting the merit criteria are most unlikely to represent value for money in the context of the programme’s objectives. The results were documented clearly, with 181 of the eligible proposals (71 per cent) assessed as not representing value for money and so excluded from further consideration as possible candidates for funding.

2.25 The 74 proposals remaining were ranked in order of the relative value for money offered by each. To clearly and consistently differentiate between proposals of varying merit, DIRD added the scores awarded against the four criteria to produce an overall score out of 20 for each proposal. Competing proposals were then ranked in descending order of merit according to their overall scores. Proposals with the same overall score were ranked as being of equal merit. As discussed in Chapter 3, and illustrated in Table 3.1, the resulting order of merit was used as the basis for selecting proposals for funding recommendation and was provided to the Minister to inform his decision making.

2.26 The value for money assessment process adopted in round one was consistent with implementation of Recommendations No.1 (b) and No.2 of ANAO Audit Report No.1 2013–14 and of Recommendation No.2 of ANAO Audit Report No.9 2014–15.

Were the scores awarded a reliable indicator of merit in the context of the programme’s objectives?

The scores were not sufficiently reliable as indicators of project merit in the context of the programme’s objectives. This was because the merit criteria did not encompass all key objectives and the underlying policy rationale for the programme. In particular, the round one arrangements did not include a mechanism for scoring proposals according to the applicant’s relative need for financial assistance or the condition of the existing bridge.

2.27 For the order of merit list to be relied upon, it is necessary that the underlying scores be an accurate reflection of each proposal’s merit. Shortcomings in this area had been identified in a previous audit, resulting in Recommendation No.1 (a) of ANAO Audit Report No.1 2013–14.24 As per the audit findings outlined below, more work is needed to implement this recommendation fully and to ensure that the suite of proposals that are scored most highly reflect the full range of the programme’s objectives.

Assessing project outcomes and benefits (criterion 1 and 2)

2.28 Criterion 1 (Improved Productivity and Access) was designed to assess the degree to which the project was consistent with the programme’s objectives. Criterion 2 (Quantified Benefits) somewhat supplemented criterion 1. It related to the degree to which the project provided a level of measurable benefits relative to other projects. As evident from Figure 2.1 above, proposals performed relatively poorly against these criteria. The majority (65 per cent) were awarded a score of less than three against criterion 1 and/or criterion 2, placing them below the value for money threshold set for this funding round.

2.29 Of note is that proposals predominately aimed at increasing productivity were generally scored more highly against criterion 1 and 2 than those predominately or partially aimed at improving community access. A comparison of the average scores awarded is provided in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Average score awarded by merit criterion by project focus

|

Project focus |

Criterion 1 |

Criterion 2 |

Criterion 3 |

Criterion 4 |

|

Increase productivity (36%) |

3 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

|

Improve community access (22%) |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

|

Both productivity and community (42%) |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records, including the department’s analysis of which programme objective/s the projects aimed to achieve.

2.30 ANAO analysis suggests there were two key factors driving this result. Firstly, proposals aimed at increasing productivity contained relatively more objective evidence and data in support of the claims made than those aimed at improving community access. It appeared more challenging for applicants seeking to improve community access to identify ways to demonstrate their projects’ merits. The initiatives outlined at paragraph 2.8 that DIRD introduced in the lead up to the second round should assist these applicants to prepare proposals that are assessed as being more meritorious.

2.31 Secondly, departmental assessors were familiar with assessing the extent to which road projects delivered productivity benefits, particularly given they were concurrently assessing proposals submitted under round four of the Heavy Vehicle Safety and Productivity Programme. The policy objective of ‘improved productivity’ was common to both programmes and the assessor guidance associated with this objective was identical. In contrast, the objective of ‘improved community access’ was specific to the newly established Bridges Renewal Programme.25 A different range of factors needed to be considered by assessors but the associated guidance provided was very limited in this regard. The risk was that proposals seeking to improve community access would instead be measured against indicators of heavy vehicle productivity and so perform relatively poorly as a result. There would have been benefit in additional guidance being provided to assessors on the scoring of proposals seeking to improve community access, so as to ensure these proposals were not disadvantaged and that the suite of successful projects would deliver both productivity and community access benefits.

The priority of the project to the relevant State/Territory (criterion 3)

2.32 The score awarded against criterion 3 (State/Territory Priority) was dependent on the priority assigned to that proposal by the relevant State agency. DIRD emailed each State a copy of the proposals submitted for projects located in that State. These were accompanied by an Excel spreadsheet and the instruction ‘the attached spreadsheets include places for you to provide a state ranking (e.g. high medium low) and a comment (i.e. justification)’. In response to a request from the ANAO to clarify whether any detailed guidance on prioritising the proposals was provided to States, DIRD advised on 3 July 2015 that:

Following a number of discussions between the Department and state/territory government representatives in the lead up to providing copies of the proposals, some jurisdictions expressed reservations about their willingness and capacity to undertake assessments and rankings. At this time, the Department determined that we would let the jurisdictions have some flexibility in the way they assessed, ranked and prioritised but noted they consider two key aspects:

1. Our preference was for them to provide a low-medium-high ranking on all proposals; and

2. The Programme Criteria and Proposal Form including that “state and territory agencies will use information provided in proposal forms to assist in prioritising”.

These messages were conveyed via telephone conversations and no formal guidance was provided to state/territory governments.

2.33 In the absence of detailed guidance, each State determined its own method and scale.26 This resulted in consistency of assessment within States but some inconsistency of assessment across States. For example, one agency assigned a priority of ‘high’ to every proposal submitted in its State. In the context of a competitive merit-based process, this offers the proposals from that State an advantage over others and it is difficult to see such an approach as achieving the objective of criterion 3. It is also at odds with a nationally competitive funding programme.

2.34 DIRD mapped the priorities assigned by States to its five-point numerical rating scale. For example, proposals assigned a ‘high’ priority were awarded a score of five against criterion 3. Most States used the three-point qualitative scale suggested by DIRD (high, medium and low), resulting in the serrated scoring-distribution that appears in Figure 2.1 above.

2.35 As shown in Table 2.2, proposals focussed on increasing productivity were generally assigned a higher priority by States and were therefore awarded a higher score against criterion 3. As an example, the basis given by one State for assigning a proposal focussed on improving community access a priority of ‘low’ was:

Bridge located on road with low traffic volumes and provides minimal contribution to freight productivity. Low benefit project from a state perspective.

2.36 As indicated by the quote above, there was evidence that some States were ranking proposals according to their degree of alignment with State agency priorities. Whereas the available evidence indicated other States were ranking proposals according to the economic and community benefits that would flow to local areas within their State. This is evident from comments such as ‘It is an important route for that community’ and ‘This bridge provides a critical link for the … rural community’. This situation suggests that the States (and the programme) would have also benefited from additional guidance from DIRD as to which of these perspectives to take when prioritising proposals and on the ‘improving community access’ objective of the programme.

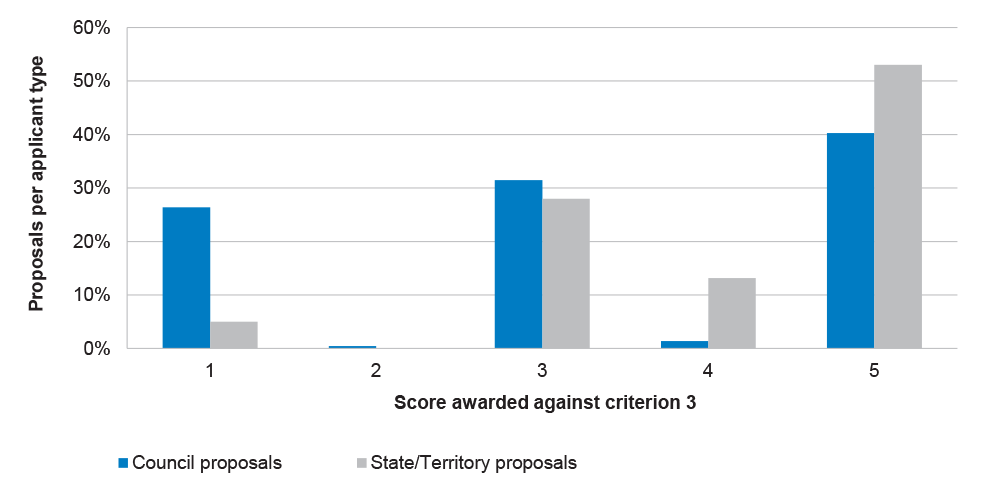

2.37 Without negating the advantages of State involvement, there was an inherent conflict of interest in the States assigning priorities to their own proposals as well as to competing Council proposals. It was not evident that the department had a strategy in place to proactively manage this conflict.27 When considering the results of the merit assessment, the Minister also expressed concern about the involvement of the States in prioritising Council projects in competition with their own (see further at paragraph 3.8). The ANAO’s analysis of the distribution of scores awarded by applicant type is presented in Figure 2.2. On average, States assigned their own proposals a higher priority in round one than the competing Council proposals.

Figure 2.2: Scores awarded against criterion 3 by applicant type

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records.

Construction readiness (criterion 4)

2.38 There were some inconsistencies in the scoring of proposals against criterion 4, such as the extent to which having an unconfirmed State contribution influenced the score awarded. The actual impact of such inconsistencies on the round one funding results was minimised by all proposals that were assessed as representing value for money being ultimately approved for Commonwealth funding. It is more common for the relative ranking of proposals to influence the funding results.28 It would therefore have been beneficial for DIRD to have provided additional guidance to assessors on the extent to which the factors considered against criterion 4 were to impact the score awarded.

Assessment of need (missing from the criteria)

2.39 The purpose of the assessment process is to identify and recommend for funding those proposals that will provide the greatest value with money in the context of the programme’s objectives. The Bridges Renewal Programme originated from a call for federal assistance to address the backlog of old and unsafe local bridges that were beyond the financial capacity of Councils to repair or replace. Missing from round one was a criterion and/or assessment process that explicitly identified and prioritised proposals with these characteristics. As a result the mix of projects that scored most highly, and so were approved for funding, was not focused towards such proposals and so did not maximise the achievement of the programme’s objectives.

Proponent’s need for financial assistance

2.40 The relative need of competing proponents for financial assistance was not factored into the four merit criteria, the scores awarded or the value for money assessment method. Information that could have been used as an indicator of relative need, which was collected by DIRD, included rate revenue data and the number of bridges under each Council’s management. In reference to this information, DIRD advised the ANAO in November 2015 that ‘The assessment criteria agreed by the Minister did not include this information and the projects were assessed on this basis’. As a result, the rate revenue and bridge numbers data obtained was not used in the assessment process and the available funding was not targeted to those proponents most in need of financial assistance (see further at paragraphs 5.19 to 5.31 of Chapter 5).

Bridge’s need for renewal

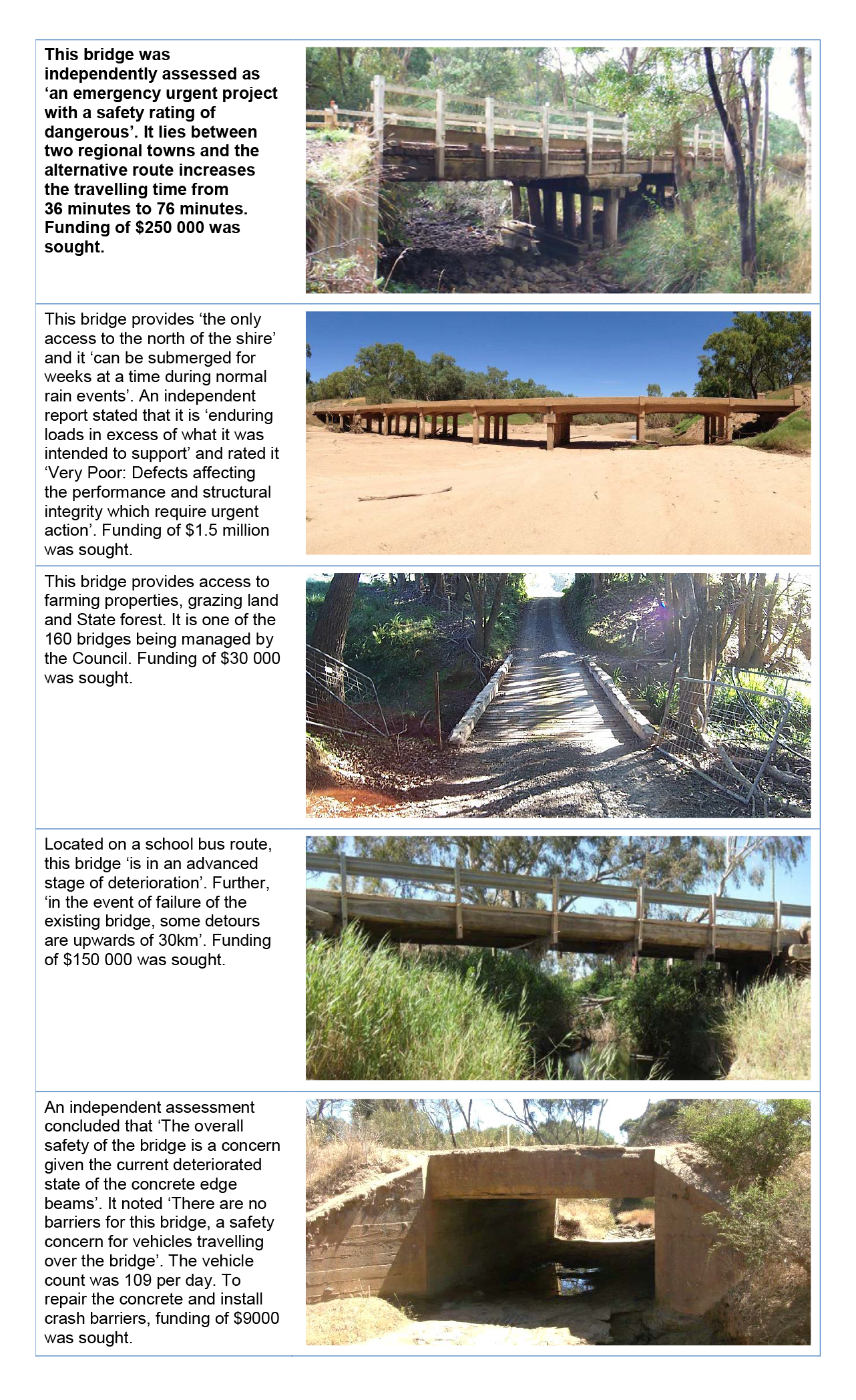

2.41 In November 2013, a brochure was published containing photographs from ‘Australia’s Worst Bridge Competition’ and a statement by the then President of the Australian Local Government Association that ‘The need for a national Bridges Renewal Programme is illustrated by this brochure and the pictures tell the story better than any words can’.29 While the Programme then established was not exclusive to the type of old and unsafe local bridges featured in the brochure, they lay at the heart of the policy objective. Many applicants chose to include photographs showing the degree of their bridge’s deterioration, include condition reports and/or express their safety concerns. But there was no criterion or weighting designed for assessors to then reflect the relative condition and safety of the bridge in the proposal’s score. Nor had the Proposal Form explicitly requested information on the current condition of the bridge.

2.42 There was potential for consideration of the bridge’s condition to be a sub-element of criterion 1 and/or 2, given the broadness of their expressed scope in assessing project outcomes and benefits. While at times assessors made reference to a bridge’s condition in relation to criterion 1 or 2, particularly as to whether it was load limited, the focus of the scoring was on productivity and community access. Hence proposals to construct new bridges were scored relatively highly by virtue of their traffic flow benefits, even though they were not replacing an existing bridge.

2.43 Proposals with low traffic numbers or no traffic volume data had difficulty attracting scores above the value for money threshold, notwithstanding they may have otherwise demonstrated through photographs, condition reports or letters of support that their bridge needed renewing. For example, a Council with the eighth lowest annual rate revenue of the 133 Councils competing in round one sought $239 500 to help repair a series of six bridges along a road in an outer-regional area. Its 147-page proposal was awarded the lowest score possible against criterion 2, which was to assess the stated benefits and supporting evidence provided. This was notwithstanding the applicant had provided letters of support from affected residents, photographs, a Structure Inspection and Load Rating Assessment Report, Bridge Inspection Reports, Box Culverts Analysis Results, Masonry Arch Load Capacity Assessment, engineering report on required works and estimated costs, and a Risk Assessment and Management Strategy. The department’s overall assessment comments included:

This proposal presents some excellent points about access and safety for the community, and these are backed by reports and photos of the bridge’s defects; however there does not appear to be data on vehicle numbers to further support the claim, or to support any claims to productivity … Moreover, the safety issues are serious, with one of the culverts having a ‘0’ rating. The proposal would receive a higher ranking if there was data on traffic numbers (current and forecast) and properties (farms, homes etc.) favourably impacted by the project.

2.44 In contrast, the overall assessment comments against a 13-page proposal from a State government for $432 500 to strengthen a bridge in a capital city, which was scored relatively highly and so recommended for funding, included:

The section of the road is in 60 km/hr speed zone with two lanes for two ways traffic and carries 17,900 vehicles/ day with 6% commercial vehicles. Strengthening of the bridge will avoid freight productivity loss by enabling unrestricted access over the bridge for freight-efficient semi-trailer and B-doubles. This bridge has been assessed by technical experts as having an “S1” rating with at least 50% probability of the bridge being load limited within the next 24 months.

2.45 Reflecting the brochure’s message that ‘pictures tell the story better than any words can’, Figure 2.3 contains examples of photographs of old, unsafe bridges from Council proposals awarded the lowest score possible against both criterion 1 and 2 and assessed by the department as not being value for money (and so were not considered as candidates to be recommended for funding). That is, within a programme established to address such deterioration, these proposals did not receive a single point above the starting score. Two of the Councils whose proposals are included in the Figure 2.3 examples provided comments to the ANAO, as follows:

- Coffs Harbour City Council: ‘Council is very supportive of external funding programs designed to assist Councils in managing their road and bridge infrastructure replacement obligations. In the past, external funding has been received by Coffs Harbour City Council from well executed external programs that have meaningful Council representation at an engineering level integrated into them. Council has a view that this aspect is particularly important during the process of developing grant application criterion (and their application forms) and during the process of assessment and ranking of submitted projects …’

- Kangaroo Island Council: ‘The Audit Report adequately addresses some of the limitations in the distribution of this funding to regional councils with low traffic counts and lower value bridges that require renewal and/or upgrade to provide transport networks to enable productivity and access to businesses and residents. This report adequately reflects Council’s position on round 1 of the Bridges Renewal Programme and that we look forward to these audit findings being incorporated into the assessment criteria for round two which we have applied for with new proposals.’

Figure 2.3: Examples of Council proposals awarded the lowest score possible against both criterion 1 and 2 and assessed as not being value for money

Source: DIRD records—information provided by applicants in their proposals for funding under round one of the Bridges Renewal Programme.

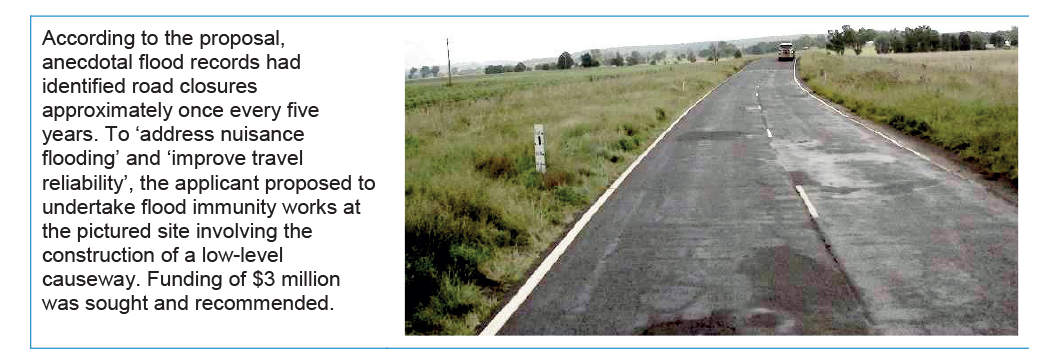

2.46 While the cohort of proposals that scored highly enough to be considered value for money by the department did include a number of deteriorating bridges, others did not sit comfortably within the programme’s intended target group. For example, one that DIRD scored relatively highly, and recommended for $3.0 million of Bridges Renewal Programme funding, proposed to undertake flood immunity works along a stretch of State highway. As illustrated by Figure 2.4, there was no bridge to renew. The proposal sought to construct a low-level causeway, which is also not a bridge but rather a raised road built across a low or wet place. The Minister had advised the department during the programme’s development that ‘flood immunity should only be taken into account when a bridge needs to be replaced for other reasons’.30

Figure 2.4: Proposal recommended for $3 million of Bridges Renewal Programme funding

Source: DIRD records—information provided by an applicant in its proposal for funding under round one of the Bridges Renewal Programme.

How well did the assessment approach reflect the principle of proportionality?

Proportionality is a key principle of funding programme administration but the assessment approach did not recognise that smaller value projects should be expected to deliver fewer benefits than higher value projects. The result was that smaller value projects were less successful.

2.47 In the context of selecting individual candidates for funding, value with money is promoted by selecting those proposals that, amongst other things, involve a reasonable (rather than excessive) cost having regard to the quality and quantity of deliverables that is proposed (and any relevant benchmarks/comparators).

2.48 It would be expected that lower value projects would need to deliver fewer benefits than higher value projects in order to be considered value for money. The Proposal Form advised applicants that more detail would be expected for larger and more complex proposals. The assessment guidance/method did not then explicitly recognise that smaller and less complex proposals required less detail to demonstrate sufficient merit. The ANAO’s analysis was that this contributed to smaller value projects being relatively less successful under round one. Eligible proposals that requested above the median amount of funding from the Commonwealth were twice as likely to be assessed by DIRD as representing value for money. At either end of the scale:

- 41 proposals sought funding amounts of up to $100 000 and five of these (12 per cent) were assessed by DIRD as being value for money; while

- 50 proposals sought funding of more than $1 million and 18 of these (36 per cent) were assessed by DIRD as being value for money.

2.49 There was no cap placed on the amount of funding that could be requested under round one, beyond the requirement that it not exceed 50 per cent of the total project cost. Funding requested by eligible proposals ranged from $6000 to $35 million, with a median of $350 000. It is challenging to determine the relative value for money of proposals without a specific method in place to manage such a wide range of project sizes. That is, to support the result that the largest proposal—the only one that achieved a total score of 20 out of 20—offered the greatest value for money to the Commonwealth when at $35 million it cost the same amount to fund as would the 159 smallest proposals competing against it.

2.50 Input to the programme’s development from the Minister, as summarised by the Minister’s Office in an email to DIRD of March 2014, included: ‘The program needs to deliver a significant number of small projects in areas where there are a large number of failing or inadequate local bridges and a handful of larger projects …’ This view is consistent with the programme’s objective of addressing the backlog of deteriorating local bridges and highlights the importance of ensuring that the assessment process allows small projects to be competitive.

3. Advice and funding decisions

Areas examined

The advice provided to the Minister by DIRD as to which applications should be approved for funding and the decisions then taken.

Conclusion

The approach taken to advising the Minister as to which proposals were recommended for funding approval, and why, was sound. In particular, there was a clear alignment between the department’s funding recommendations and the underlying assessment work.

The Minister’s funding decisions were consistent with the advice he had received.

Was the Minister adequately advised by his department?

DIRD provided sufficiently accurate and comprehensive advice to enable the Minister to perform his responsibilities as funding approver. This included outlining the relative merits of competing applications against the programme’s criteria and the extent to which they would provide value for money.

3.1 It is common for agencies to provide written advice to Ministers to inform their funding decisions.31 This assists Ministers to meet the requirements of Section 71 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 to make ‘reasonable inquiries, that the expenditure would be a proper use of relevant money’ and to ‘record the terms of the approval’. The practice also promotes informed, transparent decision-making.

3.2 The Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development was the decision maker for the Bridges Renewal Programme. The Proposal Form for round one stated that ‘The Department will assess proposals against programme criteria to develop a merit list representing best value for money and make recommendations to the Minister’. DIRD’s advice to the Minister was primarily contained in a written briefing of 19 December 2014 and, in response to the Minister’s preference to fund additional Council projects, a further briefing of 9 February 2015.

Advice of December 2014

3.3 DIRD’s December 2014 briefing clearly outlined the stages and results of the assessment process. This included the:

- details of the 12 proposals assessed as being ineligible;

- merit criteria and the scores awarded against each criterion to each of the 255 eligible proposals;

- method used to assess whether or not each eligible proposal represented value for money; and

- method used to rank the 74 proposals assessed as representing value for money in order of merit.

3.4 In so doing, the briefing was consistent with implementation of the relevant recommendations from the ANAO audits of the Regional Development Australia Fund.32

Funding recommendation

3.5 The December 2014 briefing also contained a clear funding recommendation with respect to each proposal. That is, the:

- 64 highest ranked proposals on the order of merit list were identified as recommended by the department;

- 10 remaining proposals on the order of merit list were identified as representing value for money but were not recommended for funding approval; and

- 181 eligible proposals assessed as not representing value for money, and the 12 ineligible proposals, were not recommended.

3.6 Two options for funding the 64 highest ranked proposals were presented to the Minister. The department clearly identified which was its preferred option and why. In summary, the department recommended that the Minister either:

- Option 1: approve the 64 proposals for the $105.4 million requested (which was greater than the $100 million advertised as available); or

- Option 2: approve the department’s preferred option, which related to the 64 proposals but only part funding of $29.6 million (against the $35 million requested) for the Queensland Government’s Peak Downs Highway project to ensure that the total allocated in round one was within the stated cap of $100 million.

3.7 In support of Option 2, the briefing also explained why the department had targeted the Peak Downs Highway project as the means for keeping within the $100 million funding envelope that had been advertised:

… Justification for this reduced payment includes the large amount sought in relation to the overall funding available in Round One and the Department’s view that the Queensland Government should have sufficient capacity to complete the project notwithstanding a small reduction in Australian Government funding. We note, in particular the large contingency amounts (>$10 million) in the project costings provided by Queensland. While there was not a stated cap on funding amounts for proposals in the Programme Criteria, the amount sought for Peak Downs represents more than a third of funding available. Further, $35 million would represent the largest project by a very long margin, with the next largest Australian Government contribution being $8.5 million … also going to the Queensland Government.

Minister’s concerns

3.8 The Minister did not approve the department’s recommendations or sign the December 2014 briefing. The following were the key concerns raised by the Minister and/or his Office in subsequent email exchanges and in the departmental record of a 3 February 2015 meeting between the Minister and the department:

- the large percentage of funding recommended for State government proposals, particularly for the Queensland Government;

- the involvement of the States in prioritising Council projects in competition with their own;

- whether smaller Councils had their proposals fairly assessed against those from State government and from large Councils;

- that in many cases Council proposals were assessed as not being value for money for reasons of inadequate information being provided against the quantified benefits criterion, when it should have been recognised that small Councils in particular would struggle to do detailed economic analysis or provide benefit cost ratios and traffic data, and yet the projects may be worthy; and

- that few bridge projects located in high rainfall areas were recommended and that some Councils in areas with scores of bridges in poor condition had none of their proposals recommended.

3.9 Applications from States were much more successful than Council applications at being assessed by DIRD as sufficiently meritorious and value for money. As a result, one quarter of the 64 proposals recommended were from State government and these accounted for nearly three-quarters of the funding proposed (being $73.1 million for State proposals under the department’s preferred Option 2 or $78.5 million under the non-preferred Option 1). While State government had submitted only 15 per cent of the round one proposals, they had sought over seven times more funding on average and were nearly twice as likely to be recommended than Council proposals.

3.10 At the 3 February 2015 meeting, the Minister informed the department of his preference to fund more Council proposals than had been recommended. This approach was consistent with the programme having originated in response to calls from Councils for a dedicated programme of funding to address the backlog of deteriorating local timber bridges.

Advice of February 2015

3.11 In response to the Minister’s preference to fund more Council projects, DIRD submitted a further briefing on 9 February 2015. The department recommended that the Minister approve 74 proposals for the $117.8 million requested. These comprised the:

- 64 highest ranked proposals on the order of merit list as previously recommended (but with up to $35 million for the Peak Downs Highway project as discussed below); as well as the

- 10 proposals on the order of merit list identified as representing value for money but not previously recommended, all of which had been submitted by Councils.

3.12 The written briefing of 9 February 2015 provided a revised recommendation with respect to the Peak Downs Highway project. Instead of the part funding proposed earlier, the department recommended that the Minister approve ‘up to $35 million for the highest-ranked Peak Downs, but noting to Queensland that the allocation for Round One will be taken into account in considering Round Two proposals’. The reasoning outlined in the briefing was that:

… it will take some time to negotiate alternative funding arrangements for Peak Downs (with no guarantee of success). This could put the project at risk, as Queensland may not proceed with the project at all. This would also compromise the overall value for money outcome of Round One of the Programme, as the Peak Downs project was the highest ranked project in the Round, meaning it generated the greatest value for money. The Department is therefore of the view that the recommended option, where Queensland is put on notice regarding the Round Two funding, is the most appropriate way to deal with the funding issues.

As discussed in our meeting of 3 February 2015, the proposal states that replacing all four bridges is necessary to remove the relevant load limits on the Peak Downs highway. A funding offer that saw fewer than all four bridges replaced would also mean that existing limits would remain on part of the highway, and the benefits of the project would be greatly diminished.

Identifying limitations on, or departures from, the assessment process

3.13 The December 2014 briefing identified a limitation on the information available to the assessment of criterion 3, being that the States had used differing scales when prioritising projects and that some State projects had not been assigned a priority. The department outlined the assumptions it had made when scoring proposals against criterion 3 and advised its Minister that the assumed priorities had no material effect on the funding recommendations.

3.14 However, the department did not identify in the December 2014 or February 2015 briefing that during the eligibility checking stage it had amended the intended requirement that ‘construction’ could commence in 2014–15 to be that the ‘project’ could commence in 2014–15. It also did not identify that the data collected on bridge numbers and rate revenue (at the Minister’s suggestion) was not then used during the assessment process. Nor did the briefings identify that the financial capacity of Councils was not taken into account when forming the order of merit list.33 In the interest of transparency, accountability and informed decision-making, the written advice should have outlined these departures from the agreed process as well as their consequences in terms of the programme policy underpinnings and objectives.

Were the funding decisions transparent and consistent with a merit-based process?

The Minister’s funding decisions were consistent with his department’s advice on each proposal’s merit and value for money. The funding decisions were appropriately recorded.

3.15 The Minister decided in February 2015 to approve a total of $114.8 million to fund 73 of the 74 proposals that had been recommended in the February 2015 briefing.

3.16 Three of these proposals had been submitted prior to the change of government in Queensland. The Minister placed a condition on his approval, being confirmation that the new Queensland Government wished to proceed with these projects. This approach recognised a potential risk of these proposals being withdrawn by the State government after funding had been committed by the Commonwealth. The Minister also queried the eligibility of the Peak Downs Highway project given work appeared to have commenced on one of the four bridges to be replaced. The department advised that it had assessed this project as eligible on the basis that, while there had been some rehabilitation work to the existing timber bridges, no work had started on the new concrete bridges in the proposal.

3.17 The recommended proposal that was rejected for funding by the Minister had been submitted by the NSW Government and sought $3.0 million to construct a low level causeway on the Golden Highway. The NSW Government had also applied for Heavy Vehicle Safety and Productivity Programme (HVSPP) funding to undertake these flood immunity works as part of a broader package of works along the Golden Highway. The department had separately recommended in February 2015 that the Minister approve $23.8 million for the broader package of works under the HVSPP. In this context, the department advised the Minister that ‘If you approve both projects the Department will renegotiate the costings for this HVSPP project with NSW’.

3.18 The Minister did not wish to approve the same works under two programmes—an approach consistent with ensuring public money is used efficiently and effectively. The Minister therefore proposed to approve the broader package under the HVSPP only, so long as the department was comfortable with this approach. The department confirmed that it was comfortable with the proposed approach and the Minister then documented his decision on both the HVSPP and Bridges Renewal Programme briefing papers.

Degree of alignment

3.19 There was a clear and consistent alignment between the assessment results, the order of merit list, the department’s advice and the Minister’s funding decisions. The degree of alignment with respect to the 255 eligible proposals is presented in Table 3.1. The alignment evident between the department’s funding recommendations and the underlying assessment of candidate proposals was consistent with implementation by DIRD of Recommendation No.3 of ANAO Audit Report No.3 2012–13.

Table 3.1: Alignment between assessments, ranking, recommendations and decisions

|

Score out of 20 |

No. of proposals |

Rank on merit list |

December 2014 advice |

February 2015 advice |

Funding decision |

|

Assessed as value for money |

|||||

|

20 |

1 |

1st |

Recommended |

Recommended |

Approved |

|

18 |

3 |

equal 2nd |

|

|

|

|

17 |

7 |

equal 3rd |

|

|

|

|

16 |

12 |

equal 4th |

|

|

|

|

15 |

19 |

equal 5th |

|

|

|

|

14 |

9 |

equal 6th |

|

|

|

|

13 |

13 |

equal 7th |

|

|

1 Rejecteda |

|

12 |

10 |

equal 8th |

Not recommended |

|

Approved |

|

Assessed as not representing value for money |

|||||

|

4–15 |

181 |

N/A |

Not recommended |

Not recommended |

Rejected |

Note a: One recommended proposal was rejected for Bridges Renewal Programme funding and approved as part of a broader package of works under the Heavy Vehicle Safety and Productivity Programme. See further at paragraphs 3.17 and 3.18.

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records.

Electorate distribution

3.20 The clear line of sight between the assessment results and the funding decisions helps to demonstrate equity of decision-making and guard against accusations of political bias. In addition, the ANAO’s analysis of the award of funding did not identify any evident political bias (see, for example, Table 3.2). The ANAO analysis examined the:

- population of proposals that had been received;

- department’s eligibility checking and merit assessment processes;

- department’s December 2014 recommendations;

- effect on electorate funding distribution of the Minister’s preference to fund more Council projects, which led to the February 2015 briefing; and

- population of approved projects.

Table 3.2: Electorate distribution analysis of the recommended and approved funding

|

Party holding electorate |

Proposals received |

Recommended rate (December 2014) |

Approval rate |

|||

|

|

# |

$m |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

|

Australian Labor Party |

45 |

50.4 |

33% |

37% |

38% |

34% |

|

Coalition |

218 |

252.5 |

23% |

33% |

26% |

39% |

|

Other |

9 |

8.5 |

22% |

27% |

22% |

27% |

|

Overall |

272 |

311.4 |

25% |

34% |

28% |

38% |

Note: Five proposals crossed electorates held by different political parties. In these cases, the proposal and funding is counted in full against each political party.

Source: ANAO analysis of DIRD records and Australian Electoral Commission data on 2013 federal election results.

Compliance with statutory approval requirements

3.21 The departmental briefings summarised the requirements of Section 71 (approval of proposed expenditure by a Minister) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. The records of the funding decisions and inquiries undertaken by the Minister in round one demonstrated compliance with Section 71.

3.22 Each project selected for funding also needed to be approved as an Investment Project under Part 3 Sections 9 and 17 of the National Land Transport Act 2014. The departmental briefing of December 2014 advised the Minister that the Bridges Renewal Programme projects were eligible for approval in accordance with Section 10 of the Act and appropriate to approve in accordance with Section 11 of the Act. The department obtained the Minister’s agreement that, following confirmation of project details with the successful proponents, departmental delegates would sign the relevant Project Approval Instruments under the Act.

3.23 By mid-August 2015, the completion of the evidence collection phase of this audit, signed Project Approval Instruments were in place for 58 of the successful proposals (79 per cent) for a total of $45.0 million (or 39 per cent of the funding approved). During this process, DIRD identified errors in the figures it had provided to the Minister with respect to two of the selected proposals. These errors were corrected in the signed Project Approval Instruments, resulting in a total decrease of $60 000 from that approved by the Minister.34 The status of the projects at mid-August 2015 is further outlined in Table 5.4 of Chapter 5.

4. Funding arrangements

Areas examined

ANAO examined whether appropriate funding arrangements were in place for effective oversight of the delivery of individual Bridges Renewal Programme projects, to safeguard the Commonwealth funding and for programme evaluation purposes.

Conclusion

Payments for approved projects are made under the federal financial relations framework. That framework provided adequate control and visibility for projects being delivered by State agencies. It is not well suited to administering funding for projects submitted by Councils (who were responsible for the majority—79 per cent—of the approved projects). DIRD managed some of the risks involved by engaging directly with Council proponents and by linking payments to the delivery of activities. There would have been benefits in DIRD having formally sought State agency input and agreement prior to implementing the arrangement. This could have included: