Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Design and Governance of the Child Care Package

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Education’s design and governance of the Child Care Package.

Summary and recommendation

Background

1. In the December 2018 quarter more than 1.3 million children used approved child care in Australia — representing 32 per cent of Australia’s children aged 12 years and under. The Australian Government has been providing child care fee assistance since 1972. Between mid-2000 and mid-2018, the Child Care Benefit1 and Child Care Rebate2 were the two most widely used forms of child care fee assistance.

Child Care Package

2. The Australian Government announced the new Child Care Package (the Package) on 10 May 2015, with the policy objective to deliver ‘a simpler, more affordable, more flexible and more accessible child care system’ and ‘to help parents who want to work or work more’.3 The Package comprises the Child Care Subsidy ($35.7 billion over four years from 2019–20) and support for the child care system, including the Child Care Safety Net ($1.4 billion over four years from 2019–20).

3. The Department of Education4 (the department) is the policy owner, accountable authority and lead entity with responsibility for implementing the child care reforms that make up the Package.5 The department engaged Services Australia6 under service delivery arrangements to deliver information technology (IT) services and manage the child care subsidy payments. The department also has a memorandum of understanding with the Department of Social Services for the delivery of information and communication technology (ICT) services.

4. The Family Assistance Legislation Amendment (Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Act 2017, which outlined the new Package arrangements and requirements, was enacted on 4 April 2017, and the Package took effect on 2 July 2018.

Child Care Subsidy

5. The Child Care Subsidy (the subsidy) is the centrepiece of the Package. It replaced the Child Care Benefit and the Child Care Rebate as a single means-tested subsidy to be paid to child care service providers (providers) and passed on to families as a fee reduction. In addition to basic eligibility requirements, the amount of subsidy entitlement is determined by a combination of family income, hours of activity and the type of child care service used.

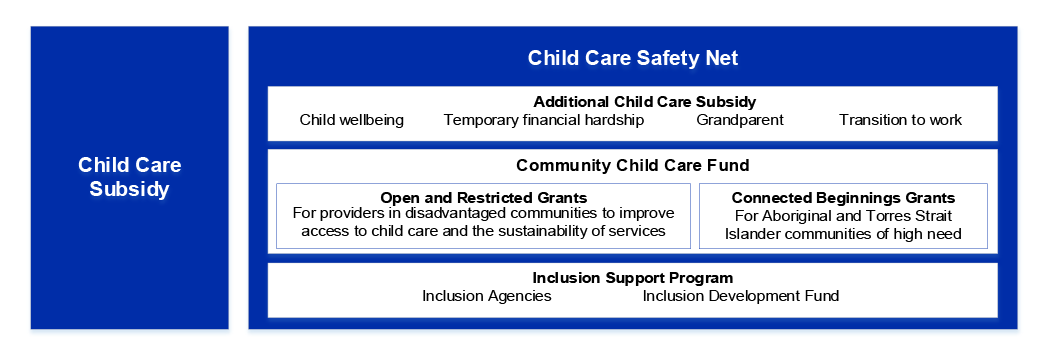

Child Care Safety Net

6. The Child Care Safety Net comprises three main elements: the Additional Child Care Subsidy; the Community Child Care Fund (including Connected Beginnings); and the Inclusion Support Program. These programs aim to provide additional support to disadvantaged or vulnerable communities and families.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

7. The Australian Government has provided financial support for child care since 1972 and established a new Child Care Package in 2018, with the objective to deliver a simpler, more affordable, more flexible and more accessible child care system that would help parents who want to work or work more. More than 1.3 million children used approved child care in the December 2018 quarter. This audit examines whether the new Package has been designed to support the achievement of the policy objectives and is being governed effectively.

Audit objective and criteria

8. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Education’s design and governance of the Child Care Package.

9. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Was the Child Care Package designed to support the achievement of the Australian Government’s policy objectives?

- Have sound arrangements been established and implemented to support the transition to, and management of, the Child Care Package?

Conclusion

10. The Department of Education’s design and governance of the Child Care Package was largely effective, except that the focus on key policy objectives for the Package in key documentation has diminished over time and ongoing oversight arrangements were not established in a timely manner.

11. The department’s design of the Package to support the achievement of the Australian Government’s policy objectives was largely effective. The department considered impacts on key stakeholders in the design of the Package, implemented an effective engagement strategy and provided appropriate advice to the Australian Government at key stages of design and implementation. Objectives were developed for the Package that aligned with the Australian Government’s policy objectives, however, these have not been consistently stated in departmental documents and the focus on key policy objectives in these documents, such as greater workforce participation, has diminished over time.

12. Sound arrangements were implemented to support the transition to the Package. Arrangements for the management of the Package are being implemented, with frameworks established for the Package’s risk management, compliance, performance management and evaluation activities. However, oversight arrangements for the management of the Package, were not established in a timely manner and are still under development.

Supporting findings

13. Objectives were developed for the Package that aligned with the Australian Government’s policy objectives. The focus on key policy objectives, such as greater workforce participation, has not been consistently or accurately stated in key departmental documents such as the 2018 Corporate Plan and Package planning, governance and communications documents.

14. Impacts on key stakeholders, such as families and child care service providers, were considered in the design of the Package.

15. An effective engagement strategy was developed and implemented for the Package.

16. Appropriate advice was provided to the Australian Government on the design and implementation of the Child Care Package.

17. Effective arrangements were established and implemented to assist key stakeholders, including families and child care providers, to transition to the new package arrangements in a timely manner, with 88.1 per cent (1,024,359 of 1,162,908) of the families who had been invited to transition and 99.9 per cent of child care providers transitioning by the 2 July 2018 deadline.7

18. Effective oversight arrangements were established and implemented for the transition to the Package. Oversight arrangements for the ongoing management of the Package were not established in a timely manner and are still under development.

19. Effective risk management plans, which were consistent with the department’s entity-wide risk management policy and framework, have been established and implemented for the Package.

20. A compliance framework has been established for the Package, building on prior compliance strategies and activities, and is in the process of being implemented.

21. A performance management framework has been established for the Package which has the potential to be effective.

22. An evaluation framework has been developed and is being implemented, with the first report finalised in July 2019 and the final report expected in June 2021.

Recommendation

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.13

The department ensure that the Child Care Package objectives are accurately described in internal and external documents and are consistent with the Australian Government’s key policy objectives, such as greater workforce participation.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

Department of Education response

23. The proposed report was provided to the Department of Education. The Department’s summary response is below and its full response is at Appendix 1.

The department welcomes the ANAO’s report and will use the findings and observations from the report to inform and enhance ongoing Package implementation and delivery arrangements. The recommendation is agreed and the ANAO’s suggested area for improvement regarding oversight arrangements for the Package will also be used to strengthen existing arrangements including where service delivery is outsourced to another entity.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

24. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy/program design

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

1.1 In the December 2018 quarter more than 1.3 million children used approved child care in Australia — representing 32 per cent of Australia’s children aged 12 years and under.8 The majority of these children (57 per cent) attended centre-based day care, 36 per cent attended outside school hours care and 10 per cent attended family day care.9

1.2 The Australian Government has provided child care fee assistance since 1972. Between mid-2000 and mid-2018, the Child Care Benefit10 and Child Care Rebate11 were the two most widely used forms of child care fee assistance. The Child Care Benefit was a means-tested payment designed to help low and middle-income families with the cost of child care. The Child Care Rebate was a non-means-tested payment providing families who were eligible for the Child Care Benefit with additional financial assistance.

Child Care Package

1.3 The Australian Government announced the new Child Care Package (the Package) on 10 May 2015, with the policy objective to deliver ‘a simpler, more affordable, more flexible and more accessible child care system’ and ‘to help parents who want to work or work more’.12 The Package comprises the Child Care Subsidy ($35.7 billion over four years from 2019–20) and support for the child care system, including the Child Care Safety Net ($1.4 billion over four years from 2019–20), as outlined at Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Main elements of the Child Care Package

Source: ANAO representation of Department of Education documentation.

1.4 The Department of Education13 (the department) is the policy owner, accountable authority and lead entity with responsibility for implementing the child care reforms that make up the Package.14 The department engaged Services Australia15 under service delivery arrangements to deliver information technology (IT) services and manage the child care subsidy payments. The department also has a memorandum of understanding with the Department of Social Services for the delivery of information and communication technology (ICT) services.

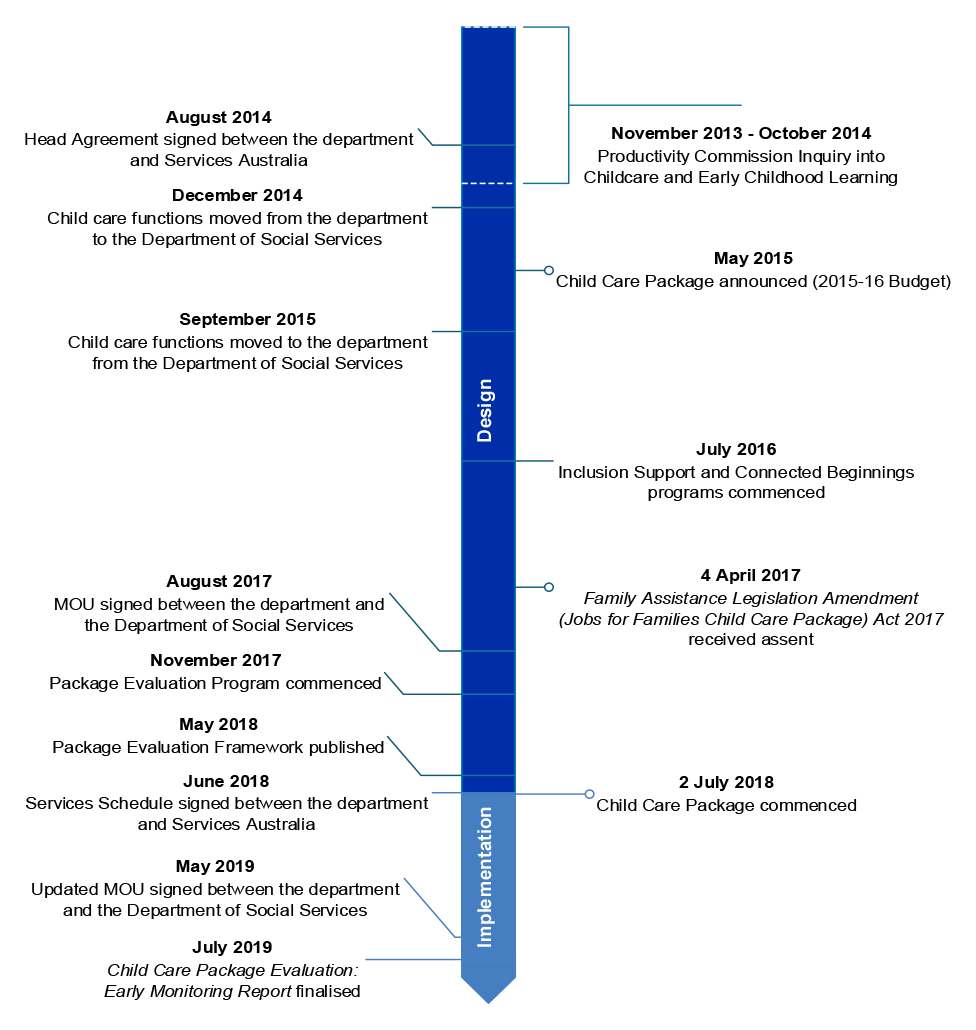

1.5 The Family Assistance Legislation Amendment (Jobs for Families Child Care Package) Act 2017, which outlined the new Package arrangements and requirements, was enacted on 4 April 2017, and the Package took effect on 2 July 2018. A timeline outlining the key elements of the Package’s design and implementation process is provided at Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Child Care Package timeline

Source: ANAO analysis.

Child Care Subsidy

1.6 The Child Care Subsidy (the subsidy) is the centrepiece of the Package. The subsidy replaced the Child Care Benefit and the Child Care Rebate, with key changes to the system including:

- a single means-tested subsidy payment instead of the two prior payments (with the Child Care Benefit means tested and the Child Care Rebate not means tested);

- the subsidy rate more closely linked to income levels than before, with the aim to make child care more affordable for low and middle income families (see Table 1.1);

- the subsidy paid directly to child care service providers16 (providers) and passed on to families as a fee reduction17;

- no annual cap for incomes up to $188,163 (2019–20) and an increased annual cap of $10,373 (2019–20), up from $7613 for the Child Care Rebate (2017–18) for families with incomes above this threshold; and

- a tightened activity test (see Table 1.2).

1.7 To be eligible to receive the subsidy, families must meet the following basic requirements: the child must be 13 years or under and not attending secondary school; the child must meet immunisation requirements; and the individual, or their partner, receiving the subsidy for a child must meet residency requirements.

1.8 The amount of subsidy entitlement is determined by a combination of family income, hours of activity and the type of child care service used, as discussed in the following sections.

Family Income

1.9 Combined family income determines the percentage of subsidy a family can receive, with lower income families receiving higher rates of subsidy. Table 1.1 illustrates the relationship between combined family income and rate of subsidy entitlement.

Table 1.1: Subsidy rate by family income level, 2019–20

|

Subsidy rate |

Combined family incomea |

|

85 per cent |

Up to $68,163 |

|

Gradually reducing to 50 per centb |

Over $68,163 to under $173,163 |

|

50 per cent |

$173,163 to under $252,453 |

|

Gradually reducing to 20 per centb |

$252,453 to under $342,453 |

|

20 per cent |

$342,453 to under $352,453 |

|

0 per cent |

$352,453 or more |

Note a: Income amounts are subject to adjustment through annual indexation.

Note b: Subsidy gradually decreases by one per cent for each $3000 of family income.

Source: ANAO representation of Department of Education documentation.

1.10 In 2019–20 if a family earns more than $188,163 and less than $352,453, child care costs are subsidised up to an annual cap of $10,373 for each child for the financial year.18

Hours of activity

1.11 The hours of subsidised care a family can access each fortnight is determined by an activity test. Recognised activities include paid work, volunteering, study of an approved course or setting up a business. The parent with the least hours of activity each fortnight determines the hours of subsidised care a child can receive. The relationship between hours of activity and maximum hours of subsidy for each fortnight is outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Subsidy activity test

|

Hours of recognised activity (a fortnight) |

Maximum hours of subsidised care (a fortnight) |

|

Less than 8 hours |

0 hoursa |

|

8 hours to 16 hours |

36 hours |

|

More than 16 hours to 48 hours |

72 hours |

|

More than 48 hours |

100 hours |

Note a: Families on $68,163 or less in 2019–20 are entitled to up to 24 hours of subsidised care under the Child Care Safety Net.

Source: ANAO representation of Department of Education documentation.

Child care service type

1.12 An hourly rate cap is placed on the amount of subsidy a family can receive for each child. This rate cap is determined by the service type used, as outlined in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Subsidy hourly rate caps by service type, 2019–20

|

Service type |

Subsidy hourly rate capa |

|

Centre Based Day Care |

$11.98 |

|

Family Day Care |

$11.10 |

|

Outside School Hours Care |

$10.48 |

|

In Home Careb |

$32.58 |

Note a: Hourly rate caps are subject to adjustment through annual indexation.

Note b: Subsidy hourly rate caps are by child, except for the In Home Care service type cap, which is by family.

Source: ANAO representation of Department of Education documentation.

Child Care Safety Net

1.13 The Child Care Safety Net comprises three main elements: the Additional Child Care Subsidy; the Community Child Care Fund (including Connected Beginnings); and the Inclusion Support Program. These programs aim to provide additional support to disadvantaged or vulnerable communities and families.

Additional Child Care Subsidy

1.14 The Additional Child Care Subsidy is a top-up payment in addition to the Child Care Subsidy that is designed to provide further assistance to families facing barriers to accessing affordable child care. These families include: those that require practical help to support their children’s safety and wellbeing; those where grandparents are the principal carers and are on income support; those experiencing temporary financial hardship19; or those with parents transitioning from income support to work. Elements of the Additional Child Care Subsidy are outlined in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4: Elements of the Additional Child Care Subsidy

|

Element |

Activity test exempt |

Maximum hours of subsidy (a fortnight) |

Maximum hourly subsidy |

|

Child wellbeing |

Yes |

100 hours |

120 per cent of the Child Care Subsidy hourly rate cap (up to actual costs) |

|

Grandparent |

Yes |

100 hours |

|

|

Temporary financial hardshipa |

Yes |

100 hours |

|

|

Transition to work |

No |

According to the activity test |

95 per cent of the Child Care Subsidy hourly rate cap |

Note a: The subsidy is paid for a maximum of 13 weeks for each event.

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Education documentation.

Community Child Care Fund

1.15 The Community Child Care Fund is a grants program providing additional funding to child care service providers in rural, regional or vulnerable communities. Under the Community Child Care Fund, eligible providers can apply for supplementary funding to:

- reduce the barriers in accessing child care, particularly for disadvantaged or vulnerable families and communities;

- provide sustainability support for child care services experiencing viability issues; and

- provide capital support to increase the supply of child care places in areas of high unmet demand.

1.16 A sub-section of the Fund is the Connected Beginnings grants program, which commenced in July 2016 and supports projects in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities of high need. Connected Beginnings is designed to support the integration of early childhood, maternal and child health and family support services with schools in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities experiencing disadvantage, so that children are well prepared for school.

Inclusion Support Program

1.17 The Inclusion Support Program commenced on 1 July 2016 and assists child care providers in improving their capabilities with the aim of bringing children with additional needs into mainstream child care services. The program has two main objectives:

- to support mainstream child care providers to improve their capacity and capability to provide quality inclusive practices, address participation barriers and include children with additional needs alongside their peers; and

- to provide parents and carers of children with additional needs with access to appropriate child care services that assist those parents to participate in the workforce.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.18 The Australian Government has provided financial support for child care since 1972 and established a new Child Care Package in 2018, with the objective to deliver a simpler, more affordable, more flexible and more accessible child care system that would help parents who want to work or work more. More than 1.3 million children used approved child care in the December 2018 quarter. This audit examines whether the new Package has been designed to support the achievement of the policy objectives and is being governed effectively.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Education’s design and governance of the Child Care Package.

1.20 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Was the Child Care Package designed to support the achievement of the Australian Government’s policy objectives?

- Have sound arrangements been established and implemented to support the transition to, and management of, the Child Care Package?

1.21 The audit focused on:

- design of the Child Care Package;

- implementation of the Child Care Reform Program;

- management of the transition to the Child Care Subsidy from the Child Care Benefit and Child Care Rebate; and

- governance arrangements established to support the implementation and ongoing management of the Child Care Package.

Audit methodology

1.22 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- examined documentation and data held by the department relating to the design and governance of the Child Care Package;

- reviewed 60 submissions sent to the ANAO from the public — 35 from child care providers, six from peak bodies and 19 from individuals; and

- interviewed relevant departmental staff.

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $299,000. The team members for this audit were Brendan Gaudry, Jennifer Eddie, Elizabeth Robinson and Deborah Jackson.

2. Design of the Child Care Package

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Child Care Package (the Package) was effectively designed to support the achievement of the Australian Government’s policy objectives.

Conclusion

The department’s design of the Package to support the achievement of the Australian Government’s policy objectives was largely effective. The department considered impacts on key stakeholders in the design of the Package, implemented an effective engagement strategy and provided appropriate advice to the Australian Government at key stages of design and implementation. Objectives were developed for the Package that aligned with the Australian Government’s policy objectives, however, these have not been consistently stated in departmental documents and the focus on key policy objectives in these documents, such as greater workforce participation, has diminished over time.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at ensuring that Package objectives are accurately described and are consistent with the Australian Government’s key policy objectives.

2.1 On 21 September 2015 child care functions and the responsibility for the Package were transferred from the Department of Social Services (DSS) to the Department of Education (the department).20 The department subsequently established the Child Care Reform Program to finalise the design and deliver the Package. In order to assess whether the department designed the Package to support the achievement of the Australian Government’s policy objectives, the ANAO examined whether: clear objectives were developed for the Package that aligned with the Australian Government’s policy objectives; impacts on key stakeholders were considered in the design of the Package; an engagement strategy was developed and implemented; and appropriate advice was provided to the Australian Government on design and implementation.

Were clear objectives developed for the Package that aligned with the Australian Government’s policy objectives?

Objectives were developed for the Package that aligned with the Australian Government’s policy objectives. The focus on key policy objectives, such as greater workforce participation, has not been consistently or accurately stated in key departmental documents such as the 2018 Corporate Plan and Package planning, governance and communications documents.

2.2 In April–May 2015 the government approved a child care reform package that: included a workforce participation stream that focused on the subsidy and an early childhood safety net; and was designed to deliver a simpler more affordable child care system that encouraged workforce participation.

2.3 In May 2015 the Australian Government announced the policy objectives of the Package in a media announcement by the Minister for Social Services, which stated that the Package would deliver ‘a simpler, more affordable, more flexible and more accessible child care system’ that would help ‘parents who want to work or work more’.21

2.4 The 2015–16 budget did not mention the objective of making the child care system simpler, but included the other key objectives, stating under Outcome 2 (Families and Communities) that:

- the Package would ‘deliver on the government’s commitment to a more affordable, accessible and flexible child care system’ and ‘facilitate economic growth by encouraging workforce participation’; and

- the ‘workforce participation stream is the key element of the Package and consists of a Child Care Subsidy based on family income, with the objective of encouraging families into work or other community based engagement’.22

2.5 Following the return of child care functions to the department from DSS in September 2015, the department developed objectives for the Package that aligned with the Australian Government’s policy objective to deliver ‘a simpler, more affordable, more flexible and more accessible child care system’ that would help ‘parents who want to work or work more’.23 These objectives were published in the department’s portfolio budget statements, corporate plan and internal planning and governance documents, however, these objectives were not consistently stated in departmental documents.

2.6 The department’s 2016–17 Portfolio Budget Statements included the Package as one of the department’s key priorities in its Strategic Direction Statement: ‘progressing the implementation of the Jobs for Families Child Care Package to make the system simpler, more flexible, more accessible and more affordable’.24 This statement omitted greater workforce participation, but included the other policy objectives. The document was not internally consistent, with the objectives under the department’s Outcome 1 mentioning accessibility, affordability and workplace participation, but excluding the objectives of a simpler system and a more flexible system. The department’s subsequent portfolio budget statements (2017–18, 2018–19 and 2019–20), also did not explicitly include the objectives of a simpler system and more flexible system under Outcome 1, as outlined in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Package objectives as reported in the department’s corporate plans and portfolio budget statements

|

|

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

|||

|

Policy objective |

PBSa |

Corporate Plan |

PBS |

Corporate Plan |

PBS |

Corporate Plan |

PBS |

|

Child care is simpler |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Child care is more accessible |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Child care is more affordable |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

Child care is more flexible |

✘ |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Greater workforce participation |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

Note a: Portfolio Budget Statements.

Source: ANAO analysis of the Department of Education’s corporate plans and portfolio budget statements.

2.7 The department’s 2016 Corporate Plan did not include the objective of a simpler child care system, but included the other objectives, stating that the objective of the Package was to ‘create a more sustainable system that encourages greater workforce participation, while addressing children’s learning and development needs’ and to ‘make child care more affordable, accessible and flexible’. The department’s 2017 Corporate Plan omitted the objectives of a simpler system and a more flexible system, but included the other objectives. The 2018 Corporate Plan omitted all key policy objectives except for more accessibility.

2.8 The department’s aim and vision for the Package, outlined in many of the department’s internal planning and governance documents did not include the policy objective of greater workforce participation, which was one of the government’s key policy objectives. For example, the department’s Child Care Reform Program Management Plan (January 2018), Child Care Reform Program Risk Management Plan (January 2018), Child Care Reform Change Management Plan (February 2018), Child Care Reform Program Issue Management Plan (January 2018) and Child Care Reform Governance Plan (May 2018) all stated that:

The Package aims to make the child care system more flexible, more accessible, more affordable and targeted to those who need it most. […] The vision for the new Child Care Package is: Simpler, more flexible, more accessible, affordable and targeted child care system supported by world class technology.

2.9 The department prepared a Child Care Subsidy Project Plan in 2015 that reiterated the government’s policy objectives, stating that:

This project will provide an opportunity to produce strategic and operational policies to give effect to the Child Care Subsidy in a way that supports families with access to quality, flexible and affordable child care to assist them to enter and remain in the workforce. [… The Subsidy] will be simpler for families to understand than the current multiple payment system.

2.10 The department’s Communications Strategy for the ‘National Child Care Plan’ campaign25 stated that the aim of the campaign was to inform parents about the proposed changes to the child care system which would make it simpler, more affordable, more accessible and more flexible. The policy objective of greater workforce participation was omitted from this statement, but was mentioned later in the document when discussing Package details and key issues for the campaign.

2.11 The focus on core policy objectives, such as encouraging workforce participation, in key departmental documents diminished over time. Other key department documents, such as the Stakeholder Engagement and Communication Strategic Plan, the Early Learning and Child Care Communication Strategy 2019 and the Child Care Provider Handbook did not discuss the objectives of the Package.

2.12 To help ensure that the department’s implementation of the Package aligns with the government’s policy intent, the department could more accurately and consistently state the government’s key policy objectives, such as greater workforce participation, in its portfolio budget statements, corporate plans and Package planning, governance and communications documents.

Recommendation no.1

2.13 The department ensure that the Child Care Package objectives are accurately described in internal and external documents and are consistent with the Australian Government’s key policy objectives, such as greater workforce participation.

Department of Education response: Agreed.

2.14 The department agrees with the recommendation and will ensure that the Australian Government’s key policy objectives for the Child Care Package are accurately and consistently stated in all relevant documentation at the entity and program level.

Were the impacts on key stakeholders considered in the design of the Package?

Impacts on key stakeholders, such as families and child care service providers, were considered in the design of the Package.

2.15 When designing the Package, impacts on key stakeholders were considered through: a Productivity Commission inquiry and public consultation on child care and early childhood learning; a behavioural micro-simulation model for the child care sector; a child care forward estimates model; a Regulation Impact Statement and consultation process; and stakeholder councils and reference groups. These processes are discussed below.

2.16 In November 2013 the Treasurer requested that the Productivity Commission undertake an inquiry into child care and early childhood learning. The Australian Government’s objectives in commissioning the inquiry were to examine and identify future options for a child care and early childhood learning system that, among other things: supports workforce participation; addresses children’s learning and development needs; is more flexible; and supports flexible, affordable and accessible quality child care and early childhood learning. The Productivity Commission’s findings in relation to the government’s key policy objectives for child care reforms are outlined at Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Productivity Commission inquiry findings on child care reform policy objectives

|

Policy objective |

Productivity Commission inquiry findings |

|

Simpler |

Child care fee assistance arrangements were complex and difficult for parents and providers to navigate and calculate. The Commission indicated its recommended reforms should make the child care system simpler. |

|

Accessible

|

There were shortfalls in providing access and supporting the needs of children with disabilities and vulnerable children, regional and rural families and parents who were moving from income support into study and employment. The Commission indicated its recommended reforms should make the child care system more accessible. |

|

Affordable |

Families were struggling to find quality child care that was affordable. The Commission indicated that: reforms primarily aimed at making child care more flexible and accessible should also improve affordability; and recommended reforms were not all aimed at making child care less costly to all families, as it also considered what was affordable for taxpayers more broadly. |

|

Flexible

|

Families struggled to find quality child care that was flexible enough to meet their needs. Improving the flexibility of child care arrangements would ideally be complemented by improvements in the flexibility of workplaces for parents. The Commission indicated its recommended reforms should make the child care system more flexible. |

|

Workforce participation |

Participation in the workforce is affected by many factors other than child care costs (including flexible work arrangements, other government family payments and support of partners). The accessibility and affordability of child care are important, but not the only factors, that discourage parents from working. The Commission estimated that its recommended reforms would increase the workforce participation of mothers by 1.2 per cent. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Productivity Commission, Childcare and Early Childhood Learning: Overview, Inquiry Report, No. 73, Canberra, 2014.

2.17 The October 2014 report included analysis of the child care market, the affordability, accessibility and flexibility of child care in Australia and how to increase workplace participation.26 The inquiry involved more than 2000 submissions and comments, public hearings and consultation with child care service providers and families who use these services. Further, the Commission created a behavioural micro-simulation model for the child care sector to examine the impacts of the recommended reforms on key stakeholders. The model simulated immediate child care and labour force responses of families to complex changes in child care arrangements, given existing tax and welfare settings. The Commission used this model to inform its recommendations for the design of child care reforms.

2.18 The department developed a child care forward estimates model for the 2016–17 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook and updated the model for the 2017–18 Budget. The departmental models examined how families would be affected by the different policy design elements, such as the activity test, the hourly rate cap and subsidy percentages based on income. The department made improvements for the 2017–18 model, such as using a year’s worth of child care administrative data (60 million records) as the basis, instead of a single week’s worth of data (1 million records) as had been the case for the previous model. As the updated model was based on a larger number of records, the department was better placed to more accurately determine the impacts of policy elements and to make adjustments.

2.19 The department published a Regulation Impact Statement for consultation on 29 June 2015 and invited members of the public to review the implementation options for the Package and provide feedback by 31 July 2015. About 1700 individuals and organisations participated in the consultation. The Regulation Impact Statement included a consideration of the impact of the proposed Package on families, providers, communities and governments.

2.20 The Regulation Impact Statement includes examples of stakeholder feedback, which was taken into account in the design of the Package, such as:

- broad support for a single subsidy;

- that a minimum co-contribution from all child care users was seen by stakeholders as acceptable, fair and necessary; and

- that families and sector representatives broadly support a closer alignment between the number of hours of subsidised care and the level of work, training, study or other recognised activity by the family.27

2.21 In relation to impact on workforce participation, the Regulation Impact Statement noted that:

While it is difficult to estimate the impacts on workforce participation due to data limitations and behavioural variables, it is expected the Jobs for Families Child Care Package will encourage families to increase their involvement in paid employment. It is expected that families increasing their workforce participation will do so by a small amount of activity. A marginal attachment to the workforce could grow over time and result in a stronger workforce participation impact.28

2.22 In relation to impact on child care fees, the Regulation Impact Statement noted that:

A co-contribution should encourage families to consider their child care service options and, in combination with a tighter activity test, exert downward pressure on fee prices. This is expected to help increase affordability for families, particularly low income families, as well as help minimise growth in Government child care fee expenditure. The Child Care Subsidy rate will also assist in improving budget sustainability for Government as less assistance is targeted to higher income families.29

2.23 The department published the final version of the Regulation Impact Statement in November 2015. The Office of Best Practice Regulation assessed it and advised the department that it was compliant with the Australian Government’s Regulation Impact Statement requirements but was not best practice. The Office of Best Practice Regulation stated: ‘Given the significance of the reforms being undertaken and the likely impacts on the early childhood education and care market, a more in-depth analysis of the expected net benefits would have resulted in the Regulation Impact Statement being assessed as best practice’.

2.24 ANAO analysis found that the Regulation Impact Statement was compliant with the requirements in The Australian Government Guide to Regulation (March 2014). However, it could have: been clearer on the strategy that underpinned the consultation process, particularly how the consultation process was designed to allow for efficient and meaningful consultation; and provided a summary of the major issues that were raised by stakeholders.

2.25 The department established a series of councils and reference groups for consultation on matters affecting the child care and early learning sector and design of the Package. The Ministerial Advisory Council for Child Care and Early Learning was established in 2014. The Council met three times a year from July 2014 until it was dissolved on 30 June 2017. The department also convened the Stakeholder Reference Group for Child Care and Early Learning in 2014, which was established to provide additional perspectives on the practical implications of child care and early learning policies. It met eight times between August 2014 and January 2016. Its membership included child care providers from across different service types.

2.26 In 2017 the department convened an Implementation and Transition Reference Group to seek feedback on key elements of the Package design and transition process. It included 12 representatives from child care peak bodies and large child care service providers and met 17 times between July 2017 and March 2019. Members discussed a variety of issues, including the impacts that certain requirements, processes and timelines would have on key stakeholders. Case Study 1 provides an example of the department considering the impacts on stakeholders and making a design change as a result.

|

Case study 1. Impact of attendance reporting requirement on stakeholders |

|

The Child Care Subsidy Secretary’s Rules 2017 included a new requirement that child care providers include daily and weekly totals of the number of hours of the child’s physical attendance during the statement period, including daily start and end times of the child’s physical attendance, in statements to parents.a This information was to be entered manually through the government’s Child Care Provider Entry Pointb or via a third-party automated attendance software solution. This requirement was to commence with the Package rollout on 2 July 2018. In July 2017, at the inaugural meeting of the Implementation and Transition Reference Group, members (child care providers and peak bodies) expressed concern that third-party software solutions that could interact with the department’s new IT system had not yet been delivered and that, without software solutions, the collection of actual attendance times would be a significant administrative burden. Members encouraged the department to consider delaying this reporting requirement by 6–12 months. The department received further stakeholder feedback through Gateway Review interviews and other consultation sessions that the 2 July 2018 deadline posed significant challenges: for providers in implementing actual attendance recording at the same time as meeting other new legislative and transition requirements; and for third-party software vendors in creating or updating automated attendance software solutions. The department considered the impact this requirement would have on stakeholders, as well as the risks to successful implementation of the child care reforms, and proposed a change to the Secretary’s Rules to delay the attendance reporting requirement by six months. The Minister approved the change in March 2018, and this reporting requirement came into effect on 14 January 2019 — six months after the commencement of the Child Care Package. |

Note a: Previously, providers had to report the number of days children attended care during a statement period, but not the number of hours or start and end times.

Note b: The department’s Child Care Subsidy System includes a Provider Entry Point, which provides basic functionality to submit legislatively required information for the payment of child care subsidies. This includes the ability to report actual attendance times manually.

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Education documentation.

2.27 Stakeholder consultation is examined further in the following section on engagement.

Was an engagement strategy developed and implemented?

An effective engagement strategy was developed and implemented for the Package.

2.28 The department developed a stakeholder engagement and communication strategic plan for the Package. The plan was endorsed in April 2016, updated in March 2017 and was in place until after the introduction of the Package in 2018. It was designed to guide communication and stakeholder engagement activities and work in parallel with the ‘National Child Care Plan’ communications campaign (discussed further in Chapter 3). The plan aligned with the objectives of the Package and outlined the four core objectives on which messages would focus:

- Awareness: messages will inform audiences what will change, why, the benefit and when.

- Prepare: messages will help audiences prepare for transition. The emphasis is on what is changing, what you need to do to prepare.

- Act: messaging will focus on what is changing, the key dates and what audiences need to do.

- Ongoing communication: when the changes are implemented, ongoing promotion will transition to the usual departmental communication activity.

2.29 The plan identified key stakeholders and outlined engagement activities tailored to each stakeholder. A Master Plan was attached to the plan that outlined proposed engagement activities and tracked completed activities. Stakeholder engagement activities included letters and emails to stakeholders, media releases, web content, fact sheets, social media posts and the Child Care Helpdesk.

2.30 A major component of engagement activities were webcasts, roadshows, information sessions and workshops, which aimed to raise awareness and answer questions about the new program for families and providers, as outlined in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Summary of engagement activities, April 2016 to December 2018

|

Stakeholder group |

Engagement activity |

No. of activities |

|

Families |

Face-to-face pilot sessions in Boxhill and Townsville (October 2017) |

2 |

|

Family webcasts (October 2017–May 2018) |

7 |

|

|

Providers and peak bodies |

Workshops on the Minister’s and Secretary’s Rules (April–December 2016) |

18 |

|

Face-to-face sessions on the Child Care Package in 12 citiesa (May–June 2017 and March 2018) |

41 |

|

|

Face-to-face sessions on the Child Care Community Fund in nine citiesb (May–June 2017) |

10 |

|

|

Webcasts and webinars on the Child Care Package, Additional Child Care Subsidy and the Child Care Community Fund (May–June 2017) |

10 |

|

|

Implementation and Transition Reference Group meetings (July 2017–December 2018)c |

17 |

|

|

Software Vendors |

Workshops (June–November 2017) |

17 |

|

Software Vendor Reference Group meeting (May 2017) |

1 |

|

Note a: Adelaide, Alice Springs, Brisbane, Broome, Cairns, Canberra, Darwin, Hobart, Melbourne, Perth, Sydney and Wodonga.

Note b: Adelaide, Brisbane, Broome, Cairns, Darwin, Melbourne, Perth, Sydney and Wodonga.

Note c: The Implementation and Transition Reference Group is discussed in paragraph 2.26. It met 17 times between July 2017 and March 2019.

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Education documentation.

2.31 Following the information sessions, the department summarised feedback from families and providers. Evaluation reports from the pilot information session for families were used to determine the timing and format of future sessions, which included holding webcasts as opposed to face-to-face sessions. Evaluations from the nine family sessions indicated that 84 per cent of families agreed or strongly agreed that the sessions were useful, and 79 per cent agreed or strongly agreed that the information was easy to understand.30

2.32 Evaluation reports from the provider sessions were used to identify key themes, concerns and misconceptions. The feedback was also used to: guide the upcoming communication and engagement activities; develop a frequently asked questions page on the department’s website; develop information sessions on targeted topics; and refine the website and the Child Care Provider Handbook.31 Evaluations from provider sessions indicated that 75 per cent of providers agreed or strongly agreed that the sessions were informative and helped them to understand changes to the child care system, but 14 per cent reported that they did not feel confident that they knew what they had to do to transition to the Package.

2.33 According to the department’s first evaluation report, as at May 2018, 86 per cent of families using paid child care reported that they were aware that the child care system was changing, but a significant proportion reported that they did not find it easy to access or understand child care fee assistance information. Just over one-third agreed or strongly agreed that they found it easy to get government information about child care fee assistance, one-quarter neither agreed nor disagreed and just over one-third disagreed or strongly disagreed.32

2.34 In February 2019 a new communications strategy replaced the stakeholder engagement and communication strategic plan. The new strategy provides an overview of business-as-usual communication activities with key stakeholders. The communications strategy outlines the department’s high-level communication approach, target audiences, and internal and external stakeholders. It uses specific measures to evaluate success of the strategy, such as seeing a reduction in enquiries to the Child Care Subsidy Helpdesk and an increase in page visits to the department’s website.

2.35 According to the new communications strategy, a brief is to be delivered to the Senior Executive Meeting33 every two months to evaluate the communication strategy and ensure the senior executive are aware of upcoming activities. The first brief on the communications strategy was presented to the Senior Executive Meeting at its 31 May 2019 meeting. The brief discussed recent communications activities and referred to the forward plan for the next four weeks of communications activities. The brief provided an update against some of the measures of success outlined in the communications strategy, such as that the daily average of visits to the department’s factsheet web page had increased from 111 visits in April 2019 to 175 visits in May 2019.

2.36 Ongoing communication activities include emails to key stakeholders, social media posts, updates to the frequently asked questions web pages, fact sheets, and the Child Care Provider Handbook. Additional webcasts were held to address specific areas of the program, such as a session on the Additional Child Care Subsidy in March 2019. The department continues to offer support to providers through the Child Care Helpdesk34, while Services Australia offers support for families in relation to the Child Care Subsidy and Additional Child Care Subsidy.

Was appropriate advice provided to the Australian Government on design and implementation?

Appropriate advice was provided to the Australian Government on the design and implementation of the Child Care Package.

2.37 The ANAO analysed 23 ministerial submissions and briefs for key decision points from July 2017 to April 2019. The department provided advice to Ministers on key matters relating to the design of the Child Care Package and the implementation of the Child Care Reform Program, including:

- policy design elements, such as the activity test, recognised activities, exemptions, child care attendance reporting and withholding provisions;

- legislative amendments, including to the Child Care Subsidy Minister’s Rules;

- key risks to the implementation of the Child Care Reform Program;

- status updates on the implementation of key elements of the Child Care Reform Program;

- status updates, key risks, delivery timeframes and results of Gateway reviews for the new Child Care Integrated IT system;

- updates on the progress of families and child care providers as they transitioned to the new Child Care Subsidy arrangements;

- outcomes of the Community Child Care Fund grant opportunities; and

- post-implementation data on the new child care system.

2.38 The briefs provided clear statements of purpose, outlined options, included the rationale for the preferred option, discussed risks and required resources, and made clear recommendations.

2.39 In addition to regular ministerial submissions and briefs, the department presented updates on the Child Care Reform Program to the Minister on 9 August 2017, 7 September 2017 and 26 March 2018. These face-to-face presentations provided the Minister with information on the program status, risks and issues, governance and change management arrangements, gateway reviews, assurance reviews, the transition and updates on the readiness of key stakeholders to transition to the new subsidy arrangements.

3. Governance arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether sound arrangements have been established and implemented to support the effective transition to and management of the Child Care Package (the Package).

Conclusion

Sound arrangements were implemented to support the transition to the Package. Arrangements for the management of the Package are being implemented, with frameworks established for the Package’s risk management, compliance, performance management and evaluation activities. However, oversight arrangements for the management of the Package, were not established in a timely manner and are still under development.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one suggestion aimed at ensuring that effective oversight arrangements are established in a timely manner and that service and quality control expectations are agreed and maintained for outsourced service delivery to provide assurance that policy objectives are being met.

3.1 In order to assess whether sound arrangements had been established and implemented to support the transition to and management of the Package, the ANAO examined the: arrangements to assist key stakeholders to transition to the Package in a timely manner; oversight arrangements; and frameworks for risk management, compliance, performance management and evaluation. These elements are discussed in the following sections.

Were effective arrangements established and implemented to assist key stakeholders to transition to the Package in a timely manner?

Effective arrangements were established and implemented to assist key stakeholders, including families and child care providers, to transition to the new package arrangements in a timely manner, with 88.1 per cent of the families (1,024,359 of 1,162,908) of the families who had been invited to transition and 99.9 per cent of child care providers transitioning by the 2 July 2018 deadline.

Child Care Reform Program

3.2 In 2015 the department established the Child Care Reform Program to deliver the Package and support the transition to the new child care arrangements. This program, which ran until September 2018, included a range of projects that were conducted in the lead-up to the transition, including Internal and external change management projects. In 2017 the department developed the Child Care Reform Program Change Management Strategy, which outlined how the program would manage and monitor the change management activities required to successfully establish and transition to the Package. The strategy included a series of primary and secondary objectives, as provided at Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Change management strategy objectives

|

Primary objectives |

Secondary objectives |

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Education documentation.

3.3 The department developed a comprehensive Child Care Reform Program Change Management Plan to define how the change management strategy objectives would be realised. The plan was endorsed in February 2018 and outlined the change management approach and activities that would be undertaken to support the transition to the Package. The change management activities were aimed at, among other things, ensuring that: families, providers and software vendors were confident to complete required transition actions in a timely manner; and the disruption to families and the sector was minimised. Key change management milestones were defined in a program milestone schedule, which was maintained by the Program Management Office.35 The program milestone schedule outlined milestones for each Child Care Reform Program project and included dependencies, milestone dates and status information and commentary. The Program Management Office provided a monthly update on the program milestone schedule to the Delivery Steering Committee.

3.4 The department undertook a range of activities to support change management and the transition of stakeholders to the new arrangements, including a communications campaign, direct communications, factsheets, task cards, emails, roadshows, workshops and direct case management, as discussed in the following sections.

‘National Child Care Plan’ campaign

3.5 To raise awareness about the Package and transition requirements, the department ran a government advertising campaign known as the ‘National Child Care Plan’ campaign. The campaign ran in two phases: the first phase from 12 November to 23 December 2017 focused on raising awareness about the Package; and the second phase from 8 April to 30 June 2018 focused on encouraging families and service providers to make the transition to the new arrangements. The department evaluated the campaign and reported positive results, including that the targeted audiences’ awareness of the change had increased from 25 per cent to 58 per cent. The campaign is summarised in Table 3.2 and discussed in greater detail in Auditor-General Report No. 7 2019–20 Government Advertising: June 2015 to April 2019.

Table 3.2: Summary of the National Child Care Plan campaign

|

Objectives |

Raise awareness of the new Child Care Package and how the reforms will affect parents and service providers; inform parents and parents-to-be of key dates and eligibility criteria; and encourage target audiences to seek further information. |

|

Timing |

Phase 1 Awareness raising: 12 November to 23 December 2017 Phase 2 Transition: 8 April to 30 June 2018 |

|

Target audience |

Parents with children aged 0 to 12 years who use, or are planning to use, formal or informal child care services; people who are considering starting a family in the next two years; and child care service providers. |

|

Media channels |

The campaign employed television, radio, search engine marketing, digital display and mobile, social media advertising, Out-of-Home (for example Billboards) and cinema, as well as channels to reach Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and culturally and linguistically diverse Australians. |

|

Total campaign expenditure |

$17.5 million (including GST) |

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Education documentation.

Transition arrangements for child care providers

3.6 In addition to the roadshows, webcasts and other engagement activities discussed in paragraphs 2.28–2.36, the department supported the transition of providers by sending ‘call to action’ and informative emails, publishing a Child Care Provider Handbook, maintaining a Child Care Helpdesk, providing direct support, conducting a provider registration ‘pilot’ and publishing transition fact sheets and other information on the Education website.

3.7 The first provider ‘call to action’ email was sent in July 2017, initially prompting providers to update their registration details. Later emails were sent at regular intervals and directed providers to take specific actions, such as registering their details or linking them to resources such as fact sheets or video presentations. In March 2018 a checklist was sent to providers outlining each of the steps providers needed to take to complete the transition process.

3.8 Following early releases of the draft for consultation, the Child Care Provider Handbook was published in June 2018. The handbook served as an in-depth walk through of the Package and how it applied to providers. Transition fact sheets were published on the department’s website, clarifying elements of the Package, such as how to define provider personnel versus service personnel. Seventy per cent of providers responding to a May–June 2018 survey reported that they had accessed the department’s website for information about the Package, with 58 per cent of respondents saying they found it helpful and 12 per cent reporting that it was not helpful.

Departmental Child Care Helpdesk

3.9 The department augmented the existing Child Care Service Helpdesk for providers. To clarify the responsibilities of the helpdesk for providers and software vendors, a helpdesk strategy was finalised between the department and Services Australia on 28 June 2018. The department’s helpdesk could assist providers with queries on the handbook; debts and repayments; child attendance data; and child care personnel verification. The strategy also outlined the limited support the helpdesk could offer to families, with families considered the responsibility of Services Australia.

3.10 The helpdesk escalates calls from families that relate to fraud, non-compliance or inadequate care facilities to the relevant internal department policy area or to the state and territory authorities responsible for regulating child care facilities. Within the helpdesk strategy, the ‘Contact One’ protocol was established, which outlined how to determine the most appropriate agency to resolve an issue and processes that aimed to reduce situations where callers are passed between entities unnecessarily.

3.11 During the week before the commencement of the Package (25–29 June 2018), the helpdesk received 3092 calls about the subsidy. Between September and December 2018, the helpdesk received 35,879 calls. In response to a May–June 2018 survey of providers, 66 per cent of respondents reported that they had accessed the department’s helpdesk, with 52 per cent of respondents saying they found it helpful and 14 per cent reporting that it was not helpful.

3.12 According to the department’s 2017–18 Annual Report, 6040 (of 605336) child care providers transitioned to the new arrangements by the 2 July 2018 deadline.

Transition arrangements for families

3.13 To transition to the new child care system, families needed to: register for a MyGov account (if they did not already have one); complete an online assessment by providing information such as their 2018–19 family income estimate and activity details; and confirm their child’s enrolment.

3.14 As previously discussed, a targeted communications campaign was directed towards families to increase awareness of the Package and to encourage families to make the transition to the new system by the 2 July 2018 deadline. Seven webcasts were held between October 2017 and May 2018. These sessions were designed to raise awareness of the incoming changes to the child care system and explain to families what they would need to do for the transition. Initial ‘call to action’ letters encouraging families to register for the child care subsidy were sent out to specific cohorts of families in January 2018, with the main ‘call to action’ campaign for families commencing in April 2018. Factsheets and task cards were made available on the department’s website to explain the steps families needed to take to complete their transition.

3.15 Of the 1,162,908 families that were invited to transition37, 1,024,359 (88.1 per cent) transitioned by the 2 July 2018 deadline.

Transition arrangements for software vendors

3.16 In its 2017 Child Care Reform Program Change Management Strategy, the department identified that successful implementation of the Package was highly dependent on child care providers being able to update their practice management software ahead of transition. For this to occur, third-party software vendors would need to update the practice management software to meet subsidy requirements by the time providers needed to start interacting with the new Child Care IT system. Without these updates, it would be difficult for providers to provide Services Australia with the data required to calculate and pay subsidy entitlements.

3.17 The department commenced consultations with software vendors in May 2017 to brief them about the new IT system and what would be required to update their software. The department and Services Australia committed to ongoing engagement with the software vendors and a process of co-design regarding the specifications the vendors would need to meet to be registered into the future. Between June and November 2017, the program held 17 software vendor working sessions. These consultations included co-design workshops and technical specification walkthroughs.

3.18 In October 2017 a centralised software account management hub was established to coordinate software vendor activities and assist with the transition of vendors to the new system. Each software vendor was assigned a dedicated account manager as a first point of contact. Account managers followed the progress of vendors, assessing their readiness for transition, developing a transition schedule for each vendor and putting contingency plans in place. In May 2018 an assurance review of software vendor readiness was conducted, which found that software vendors felt engagement had improved following the establishment of software vendor account managers. The department also regularly engaged with software vendors through face-to-face sessions and emails.

3.19 As at 6 June 2018, 24 software vendors were registered to supply software solutions for the old child care IT system. Of these, eight decided not to transition to the new IT system or were being acquired by other software providers. Of the 16 software vendors that elected to transition to the new system, 15 software vendors (representing 93 per cent of the market) transitioned by the 2 July 2018 deadline.38 By November 2018 the department had published a list of 18 software products that were registered to interface with the Child Care Subsidy System.

Monitoring and controlling transition arrangements

3.20 A multi-entity Child Care Reform Program Command Centre was established from 25 June to 25 July 2018, as a single escalation point for program issues and questions. To facilitate faster issue resolution and clearer communications, command centre team members (from the department, Services Australia and DSS) were physically co-located during these four weeks, and issue resolution meetings were held twice each day.

3.21 The department created a high-level Contingency Action Plan that outlined three major threat scenarios and established contingency actions to ensure the continuity of its key services if one of these major, unexpected or disruptive incidents were to occur during transition.39 None of the three scenarios were realised during the transition.

3.22 The department created a Go Live Checklist, which outlined readiness criteria and the associated actions required to be ready for the commencement of the Package on 2 July 2018. Each readiness criterion was assigned an accountable officer and a nominated action owner. Progress against this checklist was assessed by the Senior Responsible Officer (SRO) and key program leads in the two weeks leading up to the rollout, initially on a daily basis, and then twice daily as the commencement date approached.

Gateway reviews

3.23 Three gateway reviews were conducted to assess the Child Care IT system project status and readiness at key delivery points from August 2015 to February 2018, with the final review (Gate 5: Benefits Realisation) scheduled for late 2019. Table 3.3 outlines the Delivery Confidence Assessments for each gateway review.

Table 3.3: Gateway Review Delivery Confidence Assessments

|

Review gate |

Date provided |

Delivery Confidence Assessmenta |

No. of recommendations |

|

Gate 0/1 Business Need / Business Case Review |

21 August 2015 |

Amber/Red: Successful delivery of the project to time, cost and quality standards and benefits realisation is in doubt with major issues apparent in a few key areas. Urgent action is needed to address these. |

12 |

|

Gate 2/3 Delivery Strategy / Investment Decision |

19 May 2017 |

Amber: Successful delivery of the program/project to time, cost, quality standards and benefits realisation appears feasible, but significant issues already exist requiring management attention. These need to be addressed promptly. |

17 |

|

Gate 4 Readiness for Service Review |

16 February 2018 |

Green/Amber: Successful delivery of the project to time, cost and quality, standards and benefits realisation appears probable, however, constant attention will be needed to ensure risks do not become major issues threatening delivery. |

8 |

Note a: The Department of Finance definition of a Delivery Confidence Assessment: the collective view of the Assurance Review Team on the likelihood of overall success for the project. It uses a five-tier rating system (Red, Amber/Red, Amber, Green/Amber and Green).

Source: ANAO analysis of Department of Education documentation.

3.24 The Gateway 0/1 review report (August 2015) included 12 recommendations, of which two were rated as ‘critical’ and four were rated as ‘essential’. The Department of Social Services (DSS), the responsible entity at the time, agreed to all 12 recommendations. The Gateway 2/3 review report (May 2017) made 17 recommendations including two critical recommendations to be actioned by 30 June 2017 and nine essential recommendations to be actioned between June and December 2017. The department, DSS and Services Australia accepted all recommendations and created a joint plan of action with timelines for each. The SRO was responsible for the overall gateway review process, and updates on the status of the recommendations were provided to the Minister in July and August 2017 and to the Delivery Steering Committee in November and December 2017.40

3.25 The Gateway 4 review report (February 2018) made eight recommendations, including four rated as ‘critical’ and two rated as ‘essential’, which were all accepted. In response to one of the critical recommendations, which related to the transition of third-party software vendors, the department added a new ‘extreme’ risk to the Child Care Reform Program risk register and organised meetings with all software vendors to discuss the barriers to successful delivery of their software solutions.

3.26 The September 2018 Child Care Reform Program closure report determined that all recommendations from the three gateway review reports had been completed.

Effectiveness of transition arrangements

3.27 The department assessed the effectiveness of the transition change management and stakeholder engagement activities by regularly measuring the transition readiness of families and providers. Before the commencement of the transition, the department had estimated the anticipated transition trajectory for each stakeholder group and established contingency trigger points where the department would undertake certain activities to encourage stakeholders to transition, if transition numbers were below the department’s targets.

3.28 Starting from the initial call to action, through to the Package rollout on 2 July 2018, actual transition numbers, and a comparison against the anticipated trajectory, were reported to the SRO and other key stakeholders, such as the Program Management Office, on a daily basis. These daily transition dashboards for providers and families, as illustrated at Figure 3.1, were used to assess: progress towards transition readiness; effectiveness of the ongoing communications and stakeholder engagement; and need to trigger contingency actions.

Figure 3.1: Child Care Reform Program daily transition dashboard, 25 June 2018

Source: Department of Education.

3.29 In the May–June 2018 survey, 66 per cent of providers reported that they agreed or strongly agreed that they were prepared for the change. Of those that reported they had used government supports for the transition, such as the department’s website and helpdesk, 80 per cent stated that these supports were helpful.

3.30 According to the department’s first evaluation report (July 2019), as at May 2018, just over one-third of families agreed or strongly agreed that they found it easy to get government information about child care fee assistance, while just over one-third disagreed or strongly disagreed. In a post-implementation survey of families in July 2018, 71 per cent reported that they had found the process of applying for the new child care fee assistance quite easy or very easy. A further survey in November 2018 found that 67 per cent of families agreed or strongly agreed with the statement ‘the transition of the new subsidy was fairly seamless for me’.

3.31 As at 10:00 am on 2 July 2018, 88.1 per cent (1,024,359 of 1,162,908) of the families who had been invited to transition41 and 99.8 per cent of providers (6040 of 6053 providers)42 had completed the transition process. The department provided a grace period of 12 weeks for families to transition after the deadline.

Have effective oversight arrangements for the ongoing management of the Package been established and implemented?

Effective oversight arrangements were established and implemented for the transition to the Package. Oversight arrangements for the ongoing management of the Package were not established in a timely manner and are still under development.

Governance arrangements (October 2015 to August 2017)

3.32 In 2015 the department established the Child Care Reform Program to deliver the Package and dedicated governance and oversight arrangements to support the Package’s design and rollout. The program’s governance structure from October 2015 to August 2017 is depicted at Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: Child Care Reform Program governance structure, until August 2017

Source: ANAO representation of Department of Education documentation.

Child Care Reform Implementation Committee

3.33 The Child Care Reform Implementation Committee was responsible for decisions on the Package’s strategic direction and implementation. The committee delegated operational decisions to three subordinate boards: the Programs Board; the Payments Board; and the Child Care IT System Board. It was chaired by the department, with members from the department and DSS.

Senior Executive Meeting

3.34 The Senior Executive Meeting existed prior to the establishment of the Child Care Reform Program. It provides strategic focus and guidance to the work of the department’s Early Childhood and Child Care Cluster (the cluster) and supports the cluster’s Deputy Secretary and senior management. It is chaired by the Deputy Secretary of the cluster and is made up of all senior executive service officers within the cluster. In relation to the Package, the Senior Executive Meeting makes policy decisions and provides guidance.

Assessment of the Child Care Reform Program

3.35 In 2017 the department commissioned an assessment of the Child Care Reform Program. The review found instances of duplicate governance arrangements and that the department and Services Australia had inconsistent views of their respective roles and responsibilities.43 The June 2017 report recommended the department establish a more integrated approach, appoint a single SRO, ‘reset’ governance arrangements and agree on a clear scope of work for each department. The resulting reset commenced in September 2017 and was established by early October 2017, as discussed in the next section.

Governance arrangements (September 2017 to September 2018)

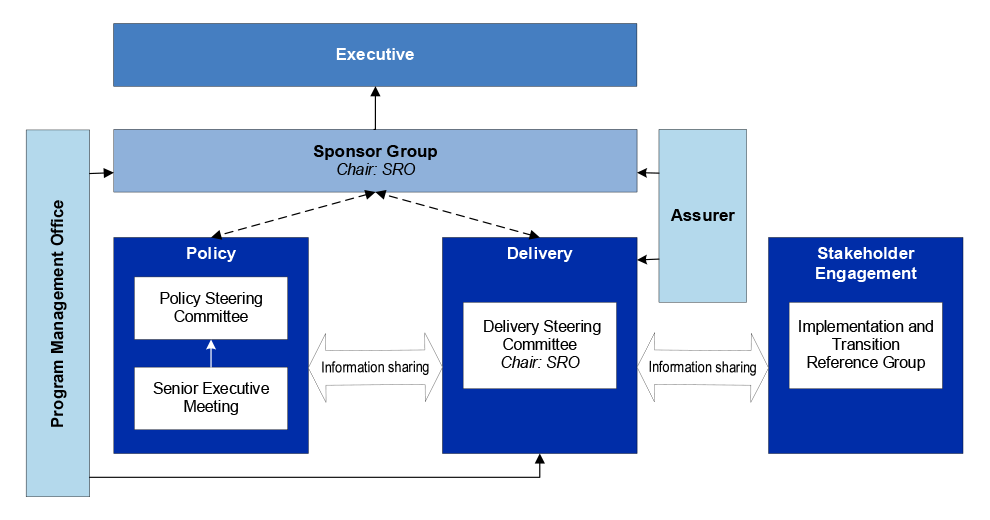

3.36 In September 2017 the department appointed a single SRO, re-established its governance structure for the Child Care Reform Program and set up a Program Management Office, as outlined in Figure 3.3. The Program Management Office developed a Governance Plan in late 2017, which received endorsement in May 2018. The plan defined the overall governance framework, reporting framework and governance controls for the program. The plan also provided an overview of the key governance committees that were to provide oversight for the program.

Figure 3.3: Child Care Reform Program governance structure, September 2017 to September 2018

Source: ANAO representation of Department of Education documentation.

Senior Responsible Officer

3.37 The SRO position is at Deputy Secretary level. From September 2017 to 8 July 2018, the SRO was provided by the department. From 9 July 2018, the SRO has been provided by Services Australia. During the transition, the SRO was responsible for ensuring that the Child Care Reform Program adhered to its vision, met program objectives and delivered the desired change. The SRO operated program-wide, with responsibility across all entities involved in the program. The SRO was the chair of the Sponsor Group and the Delivery Steering Committee.

Sponsor Group

3.38 The Sponsor Group was established in October 2017, replacing the Child Care Reform Implementation Committee. Membership included representatives from the department (including the Program Management Office), Services Australia, DSS and a commissioned Assurer. The Sponsor Group’s role was to:

- provide high level oversight of the implementation of the new child care package;

- monitor key milestones and evaluate the success of deliverables;

- oversee the effective operation of the Delivery Steering Committee and the Policy Steering Committee;

- support the SRO to achieve timely and effective delivery;

- provide strategic advice and organisational context for implementation of the new child care package;

- ensure sufficient resourcing to facilitate timely and effective delivery; and

- resolve issues escalated by the Delivery Steering Committee or Policy Steering Committee.

3.39 The Sponsor Group met 13 times between 5 October 2017 and 5 July 2018 under the department-appointed SRO and three times under the Services Australia-appointed SRO between 25 July 2018 and 27 September 2018.

Policy Steering Committee

3.40 The Policy Steering Committee was established in October 2017. Members included representatives from the department, Services Australia, DSS and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The role of the committee was to: