Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Department of Home Affairs’ Regulation of Migration Agents

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Significant changes have been made in recent years to the regulation of migration agents.

- There has been no government response to a February 2019 parliamentary committee report on the efficacy of regulation of Australian migration and education agents.

- The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit identified an audit of the regulation of migration agents as an audit priority of the Parliament.

Key facts

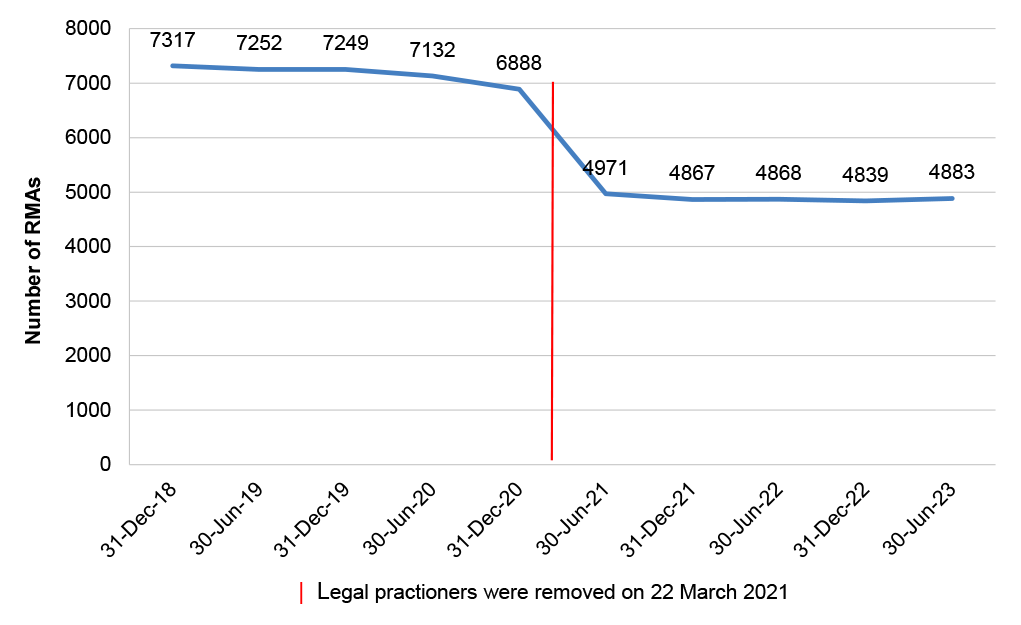

- As at 30 June 2023, there were 4883 registered migration agents.

- There were 299 complaints received in 2022–23 in respect to 244 agents (five per cent of agents).

- In the years 2019 to 2023, Home Affairs approved the registration of 267 applicants that had not met the continuing professional development requirements.

What did we find?

- Home Affairs’ regulation of migration agents is not effective.

- Appropriate arrangements are not in place to support the regulation of migration agents.

- Migration agents are not effectively regulated. The regulation of agent continuing professional development has also not been effective.

- There is an absence of regulatory action to monitor the activities of registered agents, and complaints are not actioned in a timely and effective manner.

What did we recommend?

- There were 11 recommendations to Home Affairs.

- Home Affairs agreed to the recommendations.

59%

of applications to re-register since April 2021 renewed using an automated approval process rather than being considered by a departmental officer.

9%

of complaints in 2022–23 were actioned using the powers under the Migration Act.

0

number of occasions a department officer observed a continuing professional development session in the four years between 2019–20 and 2022–23.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Migration Act 1958 (the Migration Act) requires that anyone providing immigration advice or assistance must be a registered migration agent (RMA), legal practitioner or exempt person, and that an RMA must conduct himself or herself in accordance with the prescribed Code of Conduct. The Migration Act also establishes the Migration Agents Registration Authority and sets out its powers and functions. The Office of the Migration Agents Registration Authority (OMARA or the Authority) is a section within the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs or the department).

2. The role of the OMARA is to protect consumers of migration assistance and the integrity of the Australian visa system by regulating RMAs. It is to do this by:

- maintaining a register of migration agents and administering the registration process;

- investigating and assessing complaints made in relation to the provision of immigration assistance by RMAs and where appropriate, taking disciplinary action against RMAs or former RMAs; and

- approving who can be a continuing professional development (CPD) provider and checking how CPD providers perform against the provider standards (the Migration Act requires that applicants not be registered if OMARA is satisfied that the CPD requirements have not been met).

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. In recent years there have been some significant changes to the regulation of migration agents including: legal practitioners being removed from the regulatory scheme in March 2021; a new Code of Conduct for registered migration agents being introduced in March 2022; and, also in 2022, a decision to significantly increase OMARA’s resourcing.

4. The Joint Standing Committee on Migration conducted an inquiry into the efficacy of regulation of Australian migration and education agents reporting in February 2019 making ten recommendations. There has been no government response. The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit has identified an audit of the regulation of migration agents as an audit priority of the Parliament. This audit provides independent assurance to the Parliament over whether Home Affairs is effectively regulating migration agents.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Home Affairs’ regulation of migration agents.

6. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were applied.

- Have appropriate arrangements been established to support regulatory activities?

- Is the regulatory approach effective?

Conclusion

7. Home Affairs’ regulation of migration agents is not effective.

8. Appropriate arrangements are not in place to support the regulation of migration agents. Some relevant policy and procedural documentation, including a compliance strategy and plan, either does not exist or is not current. The department has not adopted a risk-based regulatory approach informed by analysis of data, evidence and intelligence, notwithstanding the availability of data suitable for this purpose in the department’s Migration Agents Regulatory System.

9. Migration agents are not effectively regulated by Home Affairs. The administration of the agent registration process does not sufficiently address whether registered agents are fit and proper to give immigration assistance and are persons of integrity. There is an absence of regulatory action to monitor the activities of registered agents, and the department does not take timely and effective action in response to complaints it receives about the activities of registered agents. The regulation of the continuing professional development of registered agents has not been effective.

Supporting findings

Arrangements to support regulatory activities

10. Appropriate policies, procedures and guidance are not in place for the regulation of migration agents. In particular:

- there is no ministerial statement of expectations and no responding regulator statement of intent from the department;

- the department does not have an up-to-date procedure manual or instruction;

- the most recent version of the department’s compliance plan for the regulation of migration agents related to 2018–19; and

- the department has implemented an automated decision-making process for the approval of applications for re-registration, without the department having taken the necessary steps to obtain assurance that the process meets the requirements of the Migration Act 1958. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.29)

11. Home Affairs’ approach to regulating migration agents has not been informed by an appropriate assessment of compliance risk. In relation to regulating:

- continuing professional development of agents, the department does not have sufficient data to inform an assessment of risk to meet its responsibility to check that registered migration agents maintain the knowledge they need to give clients accurate advice; and

- the activities of registered migration agents, the department has data that it has not used as the basis for assessing compliance risk. The department’s data enables it to take a risk-based approach to regulatory compliance in order to focus its attention on a small proportion of agents, and shows that an educative approach to regulation would not be appropriate for them. (See paragraphs 2.30 to 2.36)

12. Home Affairs does not have an appropriate compliance plan for the regulation of migration agents. The last compliance plan was for 2018–19, with no plan in place for any of the next five years including the current year. The 2018–19 plan was not implemented by the department, and a planned evaluation by the department of the impact of the compliance strategy was not undertaken. (See paragraphs 2.37 to 2.44)

Effectiveness of the regulatory approach

13. Migration agents are not being effectively regulated by Home Affairs.

- The registration and re-registration process has not been administered in a way that has ensured the department only registers applicants that the department is satisfied are fit and proper to give immigration assistance and are persons of integrity.

- Planned compliance activity to monitor the conduct of agents was not implemented, the number of monitoring activities recorded by the OMARA has reduced substantially since 2015–16 with no monitoring activities having been recorded since the first quarter of 2020–21.

- Timely and effective regulatory action is not taken by the department when it receives complaints about the activities of individual agents. The regulatory powers provided to the department by the Migration Act are rarely used, and reporting on regulatory action has been inaccurate. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.71)

14. Home Affairs does not effectively regulate providers of continuing professional development to migration agents either in relation to the approval of providers or oversighting the performance of providers. (see paragraphs 3.73 to 3.93)

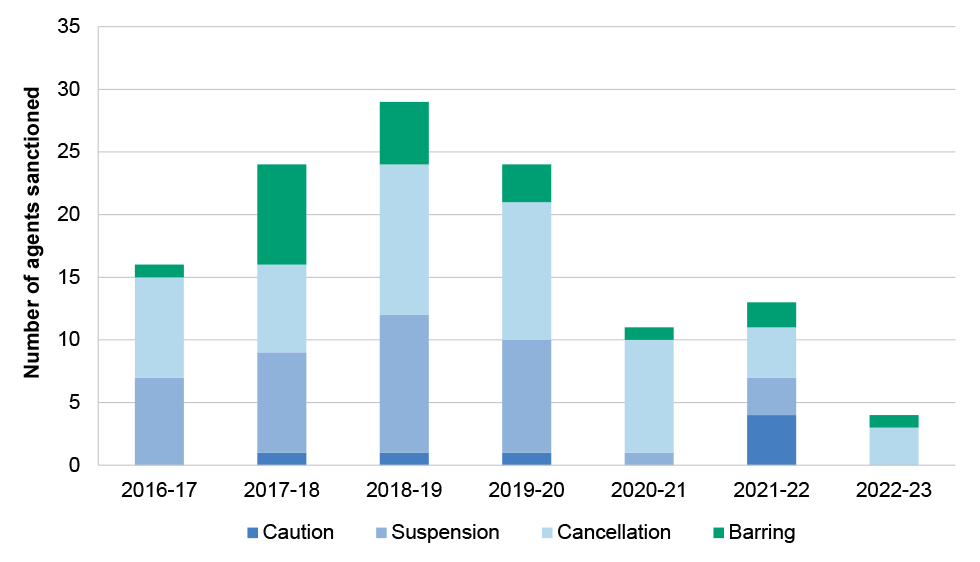

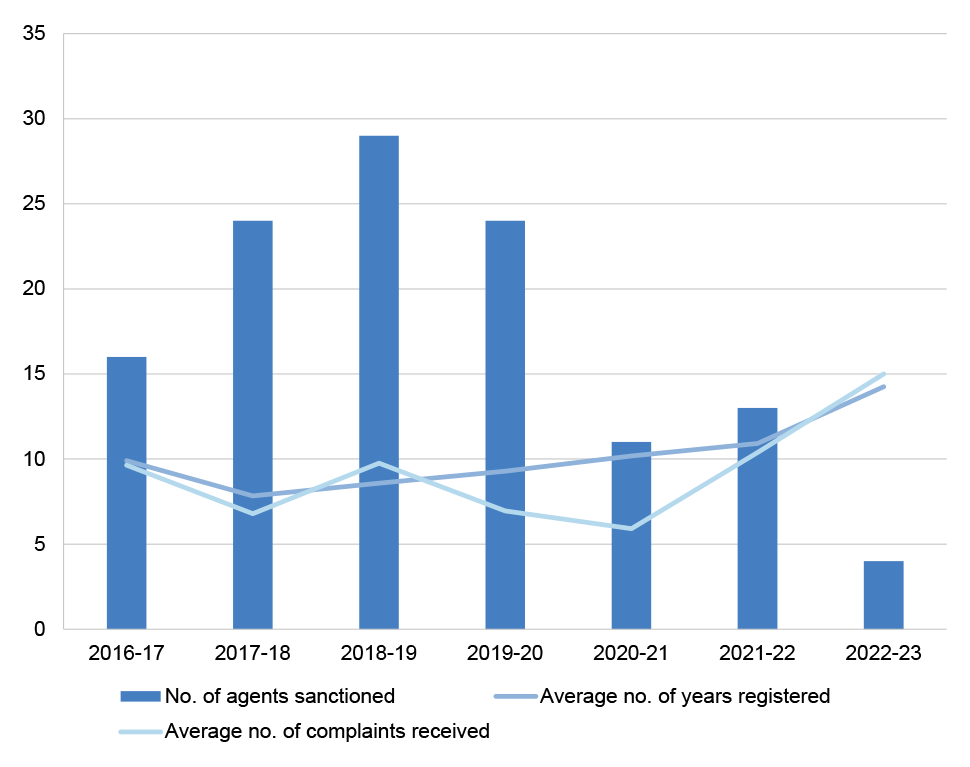

15. Home Affairs does not take appropriate action to use the regulatory powers available to it to sanction migration agents. The department’s reporting on its use of regulatory powers has been inaccurate, overstating the extent to which it has acted. Home Affairs is taking sanction action against fewer agents, and the threshold required — in terms of complaints — is increasing. The number of years of experience of those sanctioned over the last seven years indicates that the agent registration and CPD processes are not ensuring those persons being registered by the department are fit and proper persons. (see paragraphs 3.97 to 3.118)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.7

The Department of Home Affairs apply the Resource Management Guide 128: Regulator Performance and:

- advise the Minister for Home Affairs of the requirements and prepare for the minister’s approval a ministerial statement of expectations that outlines the regulatory functions within the department, including those of the Office of Migration Agents Registration Authority;

- prepare and issue in a timely manner a responding regulator statement of intent; and

- make the two statements publicly available.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.17

The Department of Home Affairs take steps to assure itself that the automated approval of applications for registration of migration agents is supported by the Migration Act 1958.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.35

The Department of Home Affairs develop, and maintain current, a documented risk assessment based on data, evidence and intelligence for its regulation of migration agents, including the continuing professional development of those agents.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 2.43

The Department of Home Affairs develop, and maintain current, a compliance strategy and compliance plan for migration agents that reflects the scope of its responsibilities under the Migration Act 1958, an assessment of risks and the regulatory powers and resources available to the department to manage those risks.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 3.9

The Department of Home Affairs assure itself that agents are registered only where they meet the continuing professional development requirements within the time period specified by the Migration Agents Regulations 1998.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.26

The Department of Home Affairs strengthen its regulation of migration agent registration requirements by making greater use of the powers provided to it by the Migration Act 1958 to inform an assessment of whether applications for registration should be granted.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.36

The Department of Home Affairs, in accordance with an up-to-date compliance strategy and compliance plan informed by an assessment of identified risk, plan and undertake regulatory monitoring of the activities of registered migration agents and report on those activities.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 3.65

The Department of Home Affairs strengthen its regulation of migration agent registration requirements by making greater use of the powers provided to it by the Migration Act 1958 to investigate complaints in relation to the provision of immigration assistance by registered migration agents.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 9

Paragraph 3.70

The Department of Home Affairs establish and report (for example, in the Migration Agent Activity Reports) on performance measures that address its performance in actioning complaints, including in relation to the timeliness of its performance and the extent to which it has used the investigation powers provided by the Migration Act 1958.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 10

Paragraph 3.92

The Department of Home Affairs improve its regulation of the continuing professional development of registered migration agents by:

- developing, and maintaining current, a documented risk assessment based on data, evidence and intelligence of the population of approved continuing professional development providers as well as data on which entities are providing the continuing professional development to those agents being frequently complained about;

- strengthen the approval process for providers by taking steps to satisfy itself that all persons that will be delivering training have been identified by the provider and that any complaints made about those persons are analysed to assess whether they are a fit and proper person; and

- use its existing powers to implement a risk-based program of quality assurance over the delivery of continuing professional development by approved providers including obtaining relevant documentation to inform desk audit activity as well as attending a selection of activities.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 11

Paragraph 3.117

The Department of Home Affairs implement processes that provide assurance that it is taking timely and effective regulatory action using the powers provided by the Migration Act 1958.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

16. The proposed audit report was provided to Home Affairs and an extract of the proposed report (in relation to the regulator performance framework discussed at paragraphs 2.3 to 2.6) was provided to the Department of Finance (Finance). The letter of response provided by Home Affairs is included in Appendix 1. Home Affairs’ summary response is reproduced below. Finance did not provide a response.

Department of Home Affairs

The department agrees with the recommendations.

In 2022, the department identified the need to enhance the OMARA’s capabilities and improve regulatory functions in order to improve the timeliness of progressing complaints to investigation and possible sanction outcomes. The department will continue to focus on enhancing the OMARA’s capabilities to ensure that it is able to operate as an effective regulator of registered migration agents in Australia.

The department does not agree with the finding that the OMARA does not take effective action on complaints it receives about the activities of registered agents. While the department agrees that it is important to make use of the powers available to the OMARA under the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Migration Act), the exercise of a statutory power and the imposition of a disciplinary decision are not the only appropriate actions that the OMARA can take in response to complaints and/or concerns about registered migration agents.

The department will continue to respond to risks posed by prospective and current registered migration agents in a timely manner, including through the exercise of relevant powers under the Migration Act as appropriate.

ANAO comment on Department of Home Affairs summary response

17. In relation to the use of powers under the Migration Act, paragraph 1.8 identifies amendments to the Migration Act that have been made over time to strengthen the regulation of migration agents. While the department does not accept that the extent to which it uses the Migration Act powers to be an appropriate benchmark of regulatory performance, the department’s formal comments included at Appendix 1: recognise that it must have supporting evidence obtained using the powers under the Act in order to pursue disciplinary action; advise that it will cease the practice of recording a breach without imposing a sanction on the agent under the Act; and state that it is implementing quality assurance processes over sanction decisions under the Act.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

18. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Migration Act 1958 (the Migration Act) requires that anyone providing immigration advice or assistance must be a registered migration agent (RMA), legal practitioner or exempt person, and that an RMA must conduct himself or herself in accordance with the prescribed Code of Conduct.1 The Migration Act also establishes the Migration Agents Registration Authority and sets out its powers and functions.2 The Office of the Migration Agents Registration Authority (OMARA or the Authority) is a section within the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs or the department). OMARA staff are primarily located in Sydney with officers also based in Victoria, Western Australia and South Australia.

1.2 The role of the OMARA is to protect consumers of migration assistance and the integrity of the Australian visa system by regulating RMAs. It is to do this by:

- maintaining a register of migration agents and administering the registration process including the legislated requirements that it not register applicants where it is satisfied they: are not a fit and proper person or not a person of integrity; or have not met the continuing professional development (CPD) requirements. As at 30 June 2023, there were 4883 agents on the register;

- investigating and assessing complaints made in relation to the provision of immigration assistance by RMAs and where appropriate, taking disciplinary action against RMAs or former RMAs. In 2022–23, 299 complaints were received in respect to 243 agents. In 2022–23, four agents were sanctioned in relation to 14 complaints, one of which had been received in 2022–23, with the other complaints having been received up to five years prior to the agent being sanctioned; and

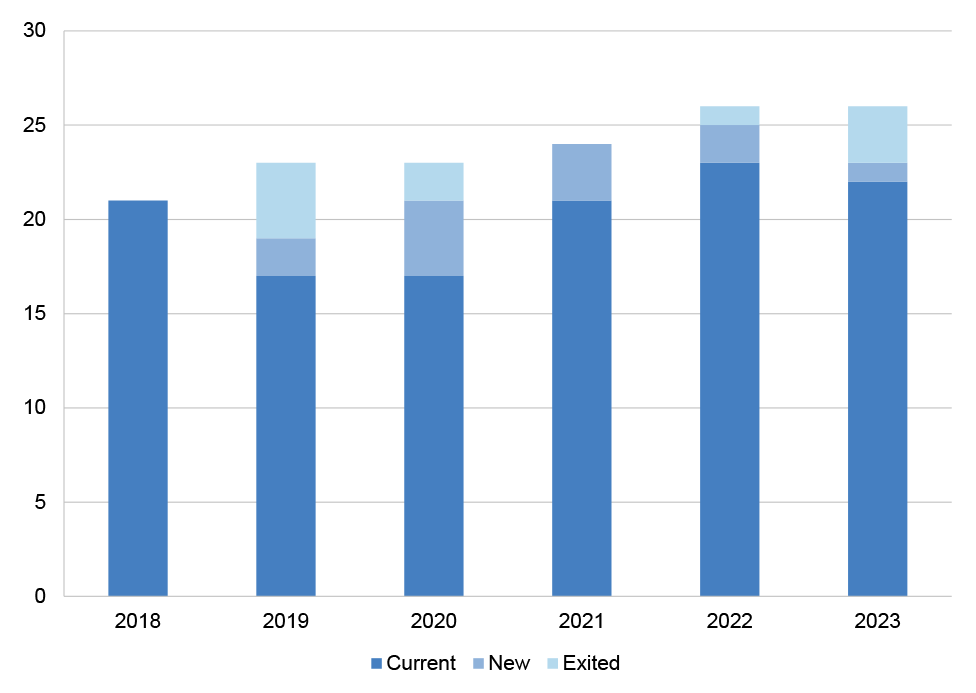

- approving who can be a CPD provider and checking how CPD providers perform against the provider standards (the Migration Act requires that applicants not be registered if OMARA is satisfied that the CPD requirements have not been met). As at September 2023 there were 22 approved CPD providers, three of which deliver CPD only within their own entity.

1.3 Since 2020–21 the OMARA has been included in one of the department’s performance outcomes (Outcome 2, Activity 2.1) and its performance reported in the department’s annual report. In relation to its regulatory performance:

- in 2020–21 and 2021–22 the performance metric was ‘Improvements to information provided to registered migration agents and consumers increase consumers’ understanding of their rights and agents’ understanding of their obligations under the regulatory framework’. While no targets were set, Home Affairs assessed the metric as met in both years;

- the metric was changed for 2022–23 to ‘100 per cent of proven instances of non-compliance results in disciplinary action taken’ with this reported as having been met on the basis that ‘appropriate’ action was taken with the registration of three agents cancelled and one former agent barred for two years3 from re-registering. The reporting did not include instances where agents had been found to be in breach of the Code of Conduct but sanction actions were not taken4; and

- for 2023–24 the metric has been changed again to ’75 per cent of less serious complaints received are resolved within 90 days and 50 per cent of serious complaints received are resolved within 180 days’.

1.4 There was no performance measure in any year relating to the administration of the registration process for agents or the regulation of CPD.

1.5 Home Affairs publishes six-monthly reports on its website that present information on the population of RMAs, some statistics on complaint processing by OMARA and some information on regulatory sanction decisions taken by OMARA (tables of sanction decisions and case studies of each instance where an agent has been cautioned, or had their registration suspended or cancelled, or where a former agent has been barred from re-registering). The reports do not set out how many complaints were received during the period or were on hand. The reports also do not include information on the CPD part of OMARA’s regulatory role.

1.6 Similar to the reporting on OMARA’s performance included by the department in its annual report, a June 2022 internal audit undertaken by the department concluded that the OMARA is ‘effectively carrying out its regulatory remit in its role as a regulator and also educator’.

1.7 Home Affairs advised the ANAO in April 2023 that it is working to implement a decision taken in 2022 to support a significant increase in the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) staff in OMARA. Previously staffed and funded at 19 FTE, additional staff have been recruited since September 2022 to reach an FTE of 38.75 as at February 2024, and the target is to reach an FTE of 50 by 30 June 2024.

1.8 Various amendments to the Migration Act have been made over a long period of time, including to strengthen the regulation of migration agents. Key amendments have included:

- 1992: legislating a registration scheme in response to government concerns about the level and nature of complaints about agents;

- 1997: implementing a package of measures reflecting the, at that time, intention to move the migration advice industry towards voluntary self-regulation through a period of statutory self-regulation;

- 2002: allowing investigation of complaints against migration agents even if they are no longer registered and dealing with situations where some time might elapse before the regulator is able to make a decision on an agent’s repeat registration application (by providing that, if the regulator has not made a decision within 10 months, the agent’s registration application will be deemed to have been granted);

- 2004: stronger registration requirements including: changes to the ‘fit and proper person’ test; empowering people to make complaints by removing any threat that civil proceedings can be taken against them for doing so; stronger investigation powers including clarifying and strengthening requirements for agents to provide documents and information to the regulator; and strengthening existing powers to sanction agents and introducing new sanction powers; and

- 2020: removal of legal practitioners with unrestricted legal practising certificates (unrestricted legal practitioners) from the regulatory scheme governing RMAs, resulting in a significant reduction in the number of immigration assistance providers regulated by OMARA (see Figure 1.1).

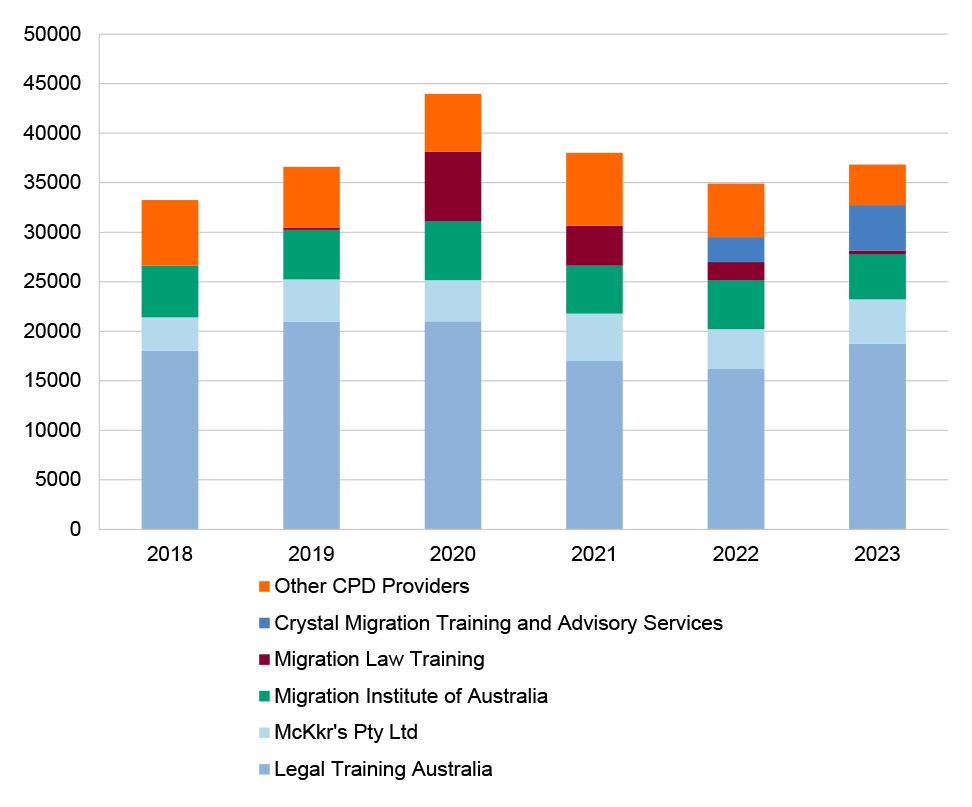

Figure 1.1: Number of migration agents registered with OMARA

Source: ANAO analysis of Home Affairs reporting.

1.9 In January 2023, the department5 entered into an engagement deed6 with Ms Christine Nixon AO APM to undertake a ‘rapid review’ into exploitation of Australia’s visa system.7 The review was to examine the powers, resourcing and sanctions available to relevant regulators, including OMARA. On 4 October 2023, the Minister for Home Affairs and Cyber Security released the Rapid Review into the Exploitation of Australia’s Visa System (the Nixon Review). While the department’s performance reporting (see paragraph 1.3) and the June 2022 internal audit (see paragraph 1.6) concluded that the regulation of migration agents has been effective, the Nixon review found that the regulation of registered migration agents must be strengthened and included nine related recommendations including increased powers for OMARA (earlier increases to regulatory powers are summarised in paragraph 1.8).

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.10 In recent years there have been changes to the regulation of migration agents including: legal practitioners being removed from the regulatory scheme in March 2021; a new Code of Conduct for registered migration agents being introduced in March 2022; and, also in 2022, a decision to significantly increase OMARA’s resourcing.

1.11 The Joint Standing Committee on Migration conducted an inquiry into the efficacy of regulation of Australian migration and education agents reporting in February 2019 making ten recommendations. There has been no government response. The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit has identified an audit of the regulation of migration agents as an audit priority of the Parliament. This audit provides independent assurance to the Parliament over whether Home Affairs is effectively regulating migration agents.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.12 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Home Affairs’ regulation of migration agents.

1.13 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were applied.

- Have appropriate arrangements been established to support regulatory activities?

- Is the regulatory approach effective?

1.14 The audit examined OMARA’s responsibilities in relation to regulation of migration agents and continuing professional development providers using the powers already provided by the Migration Act, including through the legislative amendments summarised at paragraph 1.8.

Audit methodology

1.15 The audit methodology included:

- review and analysis of relevant Home Affairs records, as well as records held by the Office of Parliamentary Counsel in relation to the drafting of relevant amendments to the Migration Act;

- review and analysis of relevant data held in the Migration Agents Regulatory System (MARS) that is used by Home Affairs as well as the six-monthly reports published by Home Affairs (see paragraph 1.5); and

- meetings with key Home Affairs staff.

1.16 Audit analysis was made more difficult due to issues with the quality of the department’s data, including its accuracy, reliability and completeness. The ANAO’s approach included the use of examples and case studies to illustrate some of the audit findings. There were 50 examples/case studies of completed/closed cases raised by the ANAO with the department as part of this performance audit and included in this audit report.

1.17 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $680,000.

1.18 The team members for this audit were Sean Neubeck, Tracy Houston, Lachlan Miles, Joshua Carruthers and Brian Boyd.

2. Arrangements to support regulatory activities

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether appropriate arrangements have been established by the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs or the department) to support its regulation of migration agents.

Conclusion

Appropriate arrangements are not in place to support the regulation of migration agents. Some relevant policy and procedural documentation, including a compliance strategy and plan, either does not exist or is not current. The department has not adopted a risk-based regulatory approach informed by analysis of data, evidence and intelligence, notwithstanding the availability of data suitable for this purpose in the department’s Migration Agents Regulatory System.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made four recommendations aimed at adopting a risk-based approach to regulating migration agents that is supported by stronger governance arrangements.

2.1 Procedures and guidance are important to ensure the delivery of policy, including regulation, is consistent with achieving intended outcomes.

2.2 Best practice regulators take a risk-based approach to compliance activities and are informed by data, evidence and intelligence. Regulators that assess the risk of non-compliance are better positioned to focus limited resources on areas of greatest impact.8 Regulators should seek to improve how they exercise their powers and deliver their legislated functions, while remaining flexible and responsive to changing circumstances.

Are appropriate policies, procedures and guidance in place?

Appropriate policies, procedures and guidance are not in place for the regulation of migration agents. In particular:

- there is no ministerial statement of expectations and no responding regulator statement of intent from the department;

- the department does not have an up-to-date procedure manual or instruction;

- the most recent version of the department’s compliance plan for the regulation of migration agents related to 2018–19; and

- the department has implemented an automated decision-making process for the approval of applications for re-registration, without the department having taken the necessary steps to obtain assurance that the process meets the requirements of the Migration Act 1958.

Statements of expectations and intent

2.3 In April 2021, ministers agreed to issue or refresh ministerial statements of expectations for the regulators within their portfolios, and in July 2021, the Regulator Performance Guide came into effect, replacing the previous Regulator Performance Framework in operation since 2014. The Regulator Performance Guide stated that:

Ministerial Statements of Expectations should be issued or refreshed every two years for all Commonwealth entities with regulatory functions, or earlier if there is a change in Minister, change in regulator leadership, or significant change in Commonwealth policy.9

2.4 Under the framework, the regulator is to respond to a ministerial statement of expectations with a regulator statement of intent.10

2.5 The Minister for Home Affairs issued a statement of expectations to the department in January 2022.11 The department did not respond with a statement of intent.

2.6 After the change of government following the May 2022 Federal election there was a change in Minister for Home Affairs. Notwithstanding the requirement to issue or refresh statements of expectations every two years or earlier if there is a change in minister, no advice has been provided by Home Affairs to the minister and, reflecting this absence of advice, no statement of expectations has been issued to the department. As a result, as at February 2024, the last ministerial statement of expectations was issued more than two years earlier and not by the current minister in the current government, and no responding regulator statement of intent has been issued by the department.

Recommendation no.1

2.7 The Department of Home Affairs apply the Resource Management Guide 128: Regulator Performance and:

- advise the Minister for Home Affairs of the requirements and prepare for the minister’s approval a ministerial statement of expectations that outlines the regulatory functions within the department, including those of the Office of Migration Agents Registration Authority;

- prepare and issue in a timely manner a responding regulator statement of intent; and

- make the two statements publicly available.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.8 The Department agrees with the recommendation and will consult within the Department and with the Minister for Home Affairs on a statement of expectations for the Minister’s approval and a responding statement of intent.

Delegation of powers

2.9 To enable officers in the Office of Migration Agents Registration Authority (OMARA or the Authority) to lawfully undertake the regulatory functions of the OMARA, the minister is required to delegate powers and functions under the Migration Act and the Migration Agents Regulations 1998 (the Regulations). Such regulatory functions include:

- considering and deciding applications for registration as a migration agent;

- deciding if organisations should be approved as continuing professional development (CPD) providers for the migration advice profession;

- issuing statutory notices under the Migration Act; and

- imposing sanctions on migration agents and former migration agents.

2.10 For a nine month period in 2016 and 2017, officers in the OMARA did not have the delegations to perform their functions and duties. Specifically, in early August 2017, the department identified that the Governance Instrument of Delegation and Authorisation Ministerial, GIDAM 24, which commenced on 12 December 2016, did not include the delegations to enable the OMARA to carry out its regulatory functions. In September 2017, more than five weeks after identifying the issue, the department advised the Assistant Minister for Immigration and Border Protection of its failure to include all pages in the relevant schedule to the instrument when it was presented to the minister for signature. The department further advised the assistant minister that:

The Department has received internal legal advice that any exercise of powers by officers of the OMARA that have not been properly delegated due to the omission in the current instrument is effective until set aside by a court or tribunal empowered to rule on the validity of that exercise of power. There has to date been no such challenge brought. The advice also provided that while the OMARA is able to continue to collect charges for registration, it would be prudent not to exercise powers that have not been properly delegated until a new instrument is in place.

2.11 Appropriate delegations are now in place. In February 2024, the department advised the ANAO that:

This was an administrative error that occurred within the department in 2016 and 2017 and was not an intentional operational decision. This administrative error does not indicate that OMARA has a tendency to operate unlawfully or that it will operate unlawfully with the autogrant process that was implemented in 2021 (see paragraph 3.17).

Departmental policies, procedures, and guidance

2.12 In August 2009, a policy and procedures manual for the OMARA was approved for issue. The manual focused on key issues and decision-making points and implemented a number of recommendations made in the 2007–08 Review of Statutory Self-Regulation of the Migration Advice Profession (the Review). It was divided into separate sections on registration, complaints handling and CPD.

2.13 The introduction to the manual stated that it would be updated and modified over time to reflect changes such as those arising from legislative amendments and further implementation of the Review recommendations with four further versions approved for issue between 2009 and 2012. While amendments for a sixth version were prepared in 2013 this update was not finalised and issued.

2.14 At the time of this ANAO performance audit, the primary governance document supporting the OMARA’s activities was a procedural instruction for working with the migration advice industry. The instruction provides information on the provision of immigration assistance, regulatory requirements to become a registered migration agent (RMA), the professional standards required of RMAs and guidance for departmental staff working with the migration advice industry. Home Affairs advised the ANAO in January 2024 that the introduction of the Policy and Procedure Control Framework saw Procedures Advice Manuals (PAMs) replaced with Policy Statements, Procedural Instructions, Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and training guides.

2.15 The first version of the Working with the Migration Advice Industry procedural instruction was issued in August 2016 with a further version issued in May 2019. Reflecting that no further versions have been issued in the subsequent four and a half years, the procedural instruction is out of date. For example, it does not reflect significant changes made to the regulation of providers of immigration assistance or advice including the March 2021 removal of unrestricted legal practitioners from the regulatory scheme. The instruction also does not reflect current aspects of the regulatory approach taken by the department in respect of:

- the application of the current complaint risk matrix (see paragraphs 3.38 to 3.40);

- the implementation of the current ‘early resolution’ model12;

- the approach to allowing applications to re-register of agents for whom there are serious integrity concerns to be ‘deemed’ rather than approved by the department (see paragraph 3.15); and

- the implementation of an automated decision-making process for the approval of applications for re-registration (see paragraph 3.17).

2.16 In relation to the latter, in September 2023, the department advised the ANAO that ‘We have not been able to locate any policy or legal document that supports implementation of the auto-grant process’.

Recommendation no.2

2.17 The Department of Home Affairs take steps to assure itself that the automated approval of applications for registration of migration agents is supported by the Migration Act 1958.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.18 The Department is taking steps to assure itself that the automated approval of applications for registration of migration agents is supported by the Migration Act 1958. This includes seeking legal advice as to the relevant legislative framework for automated decision making.

2.19 The Working with the Migration Advice Industry procedural instruction states that it consolidated the 26 page Procedures Advice Manual and the 82 page policy and procedures manual into a 35 page document. The consolidation resulted in significant detail that had been included in the policy and procedures manual on operationalising aspects of the department’s regulatory responsibilities under the Migration Act being removed.

2.20 For example, the procedures manual included guidance on the operation of section 309 of the Act (which requires that OMARA invite submissions in situations to inform decisions about whether to refuse registration or sanction agents) that was not retained in the procedural instruction. In October 2023 the department advised the ANAO in relation to section 309 that:

Wherever possible, we will seek to put the substance, or ‘gist’, of the information to the RMA but this is not always possible. We will also, if possible, seek to substantiate the information through other information or evidence that can be disclosed to the RMA.

2.21 In response to the ANAO’s further enquiries of October 2023 requesting a list of those cases where the department has put the substance, or ‘gist’, of the information to the RMA (as opposed to providing protected information to the agent), or alternatively, some examples if a full list could not be identified, notwithstanding this earlier advice, the department advised the ANAO in December 2023 that:

We do not have any examples of matters where the OMARA provided the ‘gist’ of information to an RMA as a matter of procedural fairness rather than providing security classified/non-disclosable information.

2.22 Similarly, while the procedures manual included guidance on the conduct of hearings under section 308 of the Migration Act (which is one of the investigation powers available to Home Affairs), the procedural instruction does not.

2.23 The department has a template for section 308 notices and advised the ANAO in February 2024 that it ‘is very clear in terms of its approach to issuing section 308 notices and has a standard template available’. Notwithstanding this, in respect to one of the complaints against an agent included in Appendix 3, the department recorded in its database that it had sent a section 308 notice and informed the ANAO that it considered a letter to the agent written in the following terms to be a notice under section 308: ‘If I am satisfied that the timeframe you have proposed to provide me with the special medical evidence is reasonable, I will require, under subparagraph 308(1)(c) of the Act, that you provide…’.13 The department later advised the ANAO that this letter did not involve using the section 308 power.

2.24 The procedural guidance does not set out the conduct of a hearing. August 2023 legal advice to the department (in respect to a complaint against an agent) was that, noting that the Migration Act provides little guidance on how a hearing is to be conducted and that other regulators with hearing powers have established processes in place for the exercise of their hearing powers in a fair and effective manner, it would be prudent for the department to develop guidelines on the use of the section 308 power if it intends to use it on a more frequent basis.

2.25 In July 2023, the department advised the ANAO that the Working with the Migration Advice Industry procedural instruction was being updated. As of February 2024, this update had yet to occur. In February 2024 Home Affairs advised the ANAO that:

The procedural instructions and policy statement have been drafted and are in the review stage, pending the proposed legislative amendments being introduced in 2024 via the ‘Strengthening Integrity of Immigration Assistance’ Bill.14

2.26 In relation to Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), a finding of the June 2022 internal audit (see paragraph 1.6) was that SOPs that outline the step-by-step processes for registration, CPD Provider approval, complaints handling and communications and stakeholder engagement had not yet been developed nor finalised by the department. A related recommendation was that the OMARA should develop and finalise SOPs for all relevant internal business processes and practices within the OMARA, particularly with the forthcoming restructure and increase in staffing levels.

2.27 Home Affairs agreed to implement the recommendation by 30 December 2022. SOPs relating to registrations, CPD provider approval, Capstone management15, and complaints handling were approved between February 2023 and April 2023. SOPs for communications and stakeholder engagements have not been developed. In April 2024, the department advised the ANAO that ‘a separate SOP is not required to address communication and stakeholder engagement because it has developed and approved Terms of Reference for its engagement with the Migration Industry associations and a communications plan.’

2.28 The most recent compliance strategy and plan developed by the department was for the 2018–19 financial year (see further in the section commencing at paragraph 2.37).

2.29 Training documents and user guides have been developed.

Is the regulatory approach informed by an assessment of compliance risk?

Home Affairs’ approach to regulating migration agents has not been informed by an appropriate assessment of compliance risk. In relation to regulating:

- continuing professional development of agents, the department does not have sufficient data to inform an assessment of risk to meet its responsibility to check that registered migration agents maintain the knowledge they need to give clients accurate advice; and

- the activities of registered migration agents, the department has data that it has not used as the basis for assessing compliance risk. The department’s data enables it to take a risk-based approach to regulatory compliance in order to focus its attention on a small proportion of agents, and shows that an educative approach to regulation would not be appropriate for them.

2.30 Home Affairs collects data about RMAs through the registration processes, providers of CPD, the complaints it receives from consumers of migration advice, tribunals, and from intra-departmental referrals and intelligence work within the department.

2.31 The second (of three) principles outlined by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet in its 2021 Regulator Performance Guide is for a risk-based approach informed by data, evidence and intelligence. Home Affairs has not undertaken and documented an assessment of risk consistent with this principle, notwithstanding the availability of data suitable for this purpose in the department’s Migration Agents Regulatory System (MARS).

2.32 The department’s data enables it to take a risk-based approach to regulatory compliance in order to focus on a small proportion of agents, where an educative approach would not be appropriate for them given:

- the Migration Act requires that applicants not be registered if academic and vocational requirements are not satisfied or if continuing professional development requirements are not satisfied and, in this context, most agents are experienced, with relatively few new entrants each year. Specifically:

- between 2019 and 2022, on average less than 5 per cent of all applicants were first time applicants;

- as of August 2023, current registered agents had been registered for an average of 10 years; and

- seven per cent of current RMAs as at August 2023 had less than one year of experience, and 72 per cent have six or more years (and 39 per cent have 11 or more years of experience).

- there are no complaints, or few complaints, made about the significant majority of RMAs. Specifically:

- 78 per cent have not been subject to any complaints and a further 11 per cent are complained about once every five years; and

- a small proportion of agents (one per cent) have been subject to 11 or more complaints (less than 1 per cent and 46 in total have been the subject of more than 20 complaints).

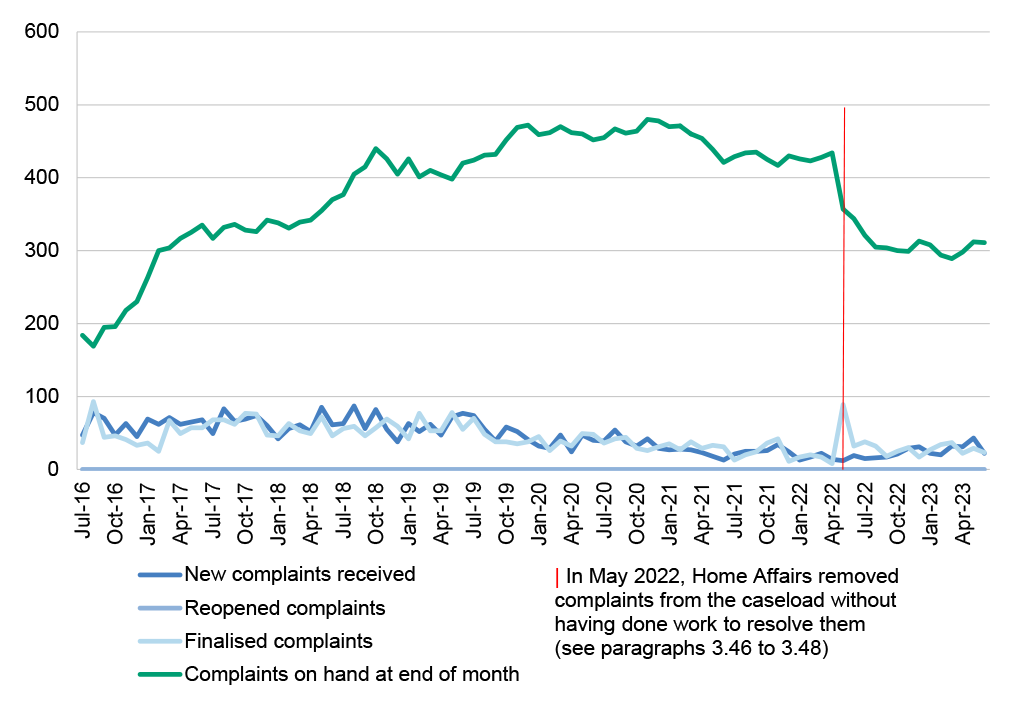

2.33 The department’s approach to managing compliance risk does not consider the risk of delays in managing and resolving complaints. The number of complaints on hand exceeded 400 complaints for more than half the seven-year period examined (see paragraph 3.43). It is common for the department to take a long time to investigate and resolve complaints. For example, as of March 2024, there is an open complaint dating back to 2017, nine open complaints from 2018, 22 open complaints from 2019, and 14 open complaints from 2020.

2.34 Part of the department’s regulatory role is to check that registered migration agents maintain the knowledge they need to give clients accurate advice, through continuing professional development (CPD). The department approves who can be a CPD provider and is responsible for checking how CPD providers perform against the provider standards. The department has access to data that it could use to analyse the population of approved CPD providers (see paragraphs 3.75 to 3.77). In relation to the delivery of CPD by those providers, the department identified a risk that providers may deliver poor quality CPD activities that do not comply with the requirements of the provider standards. The department proposed to address this risk through strategies that it has not implemented and so the data on the results have not been available to inform updates to a risk assessment. The specific strategies in its 2018–19 compliance plan that the department did not implement were:

- a ‘desk audit’ of 100 per cent of CPD providers; and

- attending a selection of mandatory CPD activities for 40 per cent to 60 per cent of providers.

Recommendation no.3

2.35 The Department of Home Affairs develop, and maintain current, a documented risk assessment based on data, evidence and intelligence for its regulation of migration agents, including the continuing professional development of those agents.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.36 The Department will develop and maintain a documented risk assessment for its regulation of migration agents across all of its regulatory functions, including the continuing professional development of those agents.

Has an appropriate compliance plan been documented reflecting an assessment of identified risk?

The Department of Home Affairs does not have an appropriate compliance plan for the regulation of migration agents. The last compliance plan was for 2018–19, with no plan in place for any of the next five years including the current year. The 2018–19 plan was not implemented by the department, and a planned evaluation by the department of the impact of the compliance strategy was not undertaken.

2.37 One of OMARA’s functions under section 316 of the Migration Act is to monitor the conduct of RMAs. The department’s procedural instruction for working with the migration advice industry of May 2019, outlines that:

The OMARA has a responsibility to give confidence to the Parliament, the Government, consumers and the community, that RMAs are complying with their obligations and the potential for harm is minimised. OMARA has a Compliance Strategy and plan to enhance OMARA’s delivery against this remit.

The objectives of the OMARA’s planned compliance activities are to protect consumers by raising and maintaining the standards of the migration advice industry.

2.38 The department does not have a current compliance strategy and plan. The most recent compliance strategy was developed by the department for the 2018–19 financial year. The compliance plan to deliver on the strategy was an attachment to the 2018–19 strategy. An updated plan was not in place for 2019–2016, 2020–21, 2021–22, 2022–23 or 2023–24 and the 2018–19 plan included a number of risk treatment activities the department does not undertake including:

- conducting 200 website audits each year to address the risk of misleading advertising by migration agents;

- in relation to four of the identified risks, issuing notices under section 308 of the Migration Act to provide the information necessary for the department to undertake 35 client file audits per year (which the plan said would involve approximately 0.03 per cent of cases represented by migration agents); or

- the risk treatments relating to the regulation of CPD providers (see paragraphs 2.34 and 3.91).

2.39 In addition, several significant changes to the regulatory environment have occurred since 2018–19, including:

- the removal of legal practitioners from the regulatory scheme in March 2021; and

- the introduction of a new Code of Conduct for RMAs from 1 March 2022.

2.40 The decision taken by the department in 2022 to increase OMARA staff to undertake regulatory functions was not on the basis of a documented compliance strategy.17

2.41 The 2018–19 compliance strategy stated that it would be evaluated in the first quarter of 2019–20 to ascertain whether the strategy resulted in:

- an increase in the detection and sanctioning of RMAs who pose high or medium level threats;

- a better understanding of the risk indicators associated with RMAs for whom we don’t necessarily currently receive complaints against; and

- a better understanding of the proportion of RMAs who present high, medium and low threats to inform future compliance strategies.

2.42 The department did not undertake this evaluation.

Recommendation no.4

2.43 The Department of Home Affairs develop, and maintain current, a compliance strategy and compliance plan for migration agents that reflects the scope of its responsibilities under the Migration Act 1958, an assessment of risks and the regulatory powers and resources available to the department to manage those risks.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.44 The Department has developed a draft Compliance and Monitoring Framework, Strategy and Plan and will continue to refine this further as the OMARA Risk Management Plan and Risk Register is matured.

3. Effectiveness of the regulatory approach

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs or the department) has an effective approach to the regulation of migration agents, consistent with the objectives of the regulatory scheme legislated by the Parliament.

Conclusion

Migration agents are not effectively regulated by Home Affairs. The administration of the agent registration process does not sufficiently address whether registered agents are fit and proper to give immigration assistance and are persons of integrity. There is an absence of regulatory action to monitor the activities of registered agents, and the department does not take timely and effective action in response to complaints it receives about the activities of registered agents. The regulation of the continuing professional development of registered agents has not been effective.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made seven recommendations. Five recommendations are focussed on the department more effectively regulating the activities of registered migration agents, including greater use of the powers provided to it by the Migration Act 1958 (the Migration Act) when registering agents and in responding to complaints it receives. Further recommendations were made in relation to the regulation of agent continuing professional development and in relation to the use of the regulatory sanctions available under the Migration Act.

3.1 Regulators have a responsibility to give confidence to Parliament, the government and the community that regulated entities are complying with their statutory obligations and that appropriate enforcement action is taken when a regulated entity fails to meet its obligations.

Does Home Affairs effectively regulate registered migration agents?

Migration agents are not being effectively regulated by Home Affairs.

- The registration and re-registration process has not been administered in a way that has ensured the department only registers applicants that the department is satisfied are fit and proper to give immigration assistance and are persons of integrity.

- Planned compliance activity to monitor the conduct of agents was not implemented, the number of monitoring activities recorded by the OMARA has reduced substantially since 2015–16 with no monitoring activities having been recorded since the first quarter of 2020–21.

- Timely and effective regulatory action is not taken by the department when it receives complaints about the activities of individual agents. The regulatory powers provided to the department by the Migration Act are rarely used, and reporting on regulatory action has been inaccurate.

3.2 The functions of the Office of Migration Agents Registration Authority (OMARA or the Authority) specified in the Migration Act include dealing with registration applications, monitoring the conduct of Registered Migration Agents (RMAs) and investigating complaints. As discussed at paragraphs 2.10 and 2.11, for a nine-month period in 2016 and 2017 the department did not have in place the delegations necessary for officials to exercise regulatory powers provided under the Migration Act. While the department identified that this affected more than 5200 registration decisions, it did not impact the exercise of other powers to monitor agent activities, investigate complaints or sanction agents because the department had not undertaken any monitoring activities, used the legislated investigation powers or sanctioned any agents during the period when there was not a delegation in place.

Registration

3.3 Amendments to the Migration Act in 1992 (see paragraph 1.8) introduced a registration scheme for migration agents. One of the recommendations of the Nixon review (see paragraph 1.9) was to increase the background checks undertaken for initial and repeat applications for registration. As set out at paragraph 2.32, there are relatively few new entrants into the population of RMAs each year with, on average, less than 5 per cent of all applicants between 2019 and 2022 being first time applicants.

Continuing professional development

3.4 As discussed in paragraphs 3.73 and 3.74, RMAs are required to complete a specified amount of continuing professional development (CPD) each year to stay registered. Notwithstanding this requirement, Home Affairs has recorded that it is ‘fairly common’ to receive agent registration applications that have not met the CPD requirements and that ‘we do allow time to provide additional documents or evidence of having accrued CPD points’.

3.5 The department does not have adequate controls to identify whether only those agents who have met the CPD requirements (as set out in Section 290A of the Migration Act) are registered. For example:

- the department’s registrations and CPD standard operation procedure (SOP) does not include procedural guidance for verifying, clarifying, and assessing whether an applicant has met CPD requirements (see paragraph 3.73);

- evidence supporting the assessment of applications to register is not stored in the Migration Agents Regulatory System (MARS)18 in accordance with the SOP (for example, checklist items are not completed, supporting documents and correspondence are not attached, and sufficient supporting information is not included in records of decision);

- the criteria used to ‘auto-grant’ approval of applications to re-register (see paragraph 3.17 below) do not include CPD requirements; and

- there are data quality issues in the MARS used to store records relating to registrations, including errors that indicate the department has not performed adequate quality assurance of its data held within MARS.19

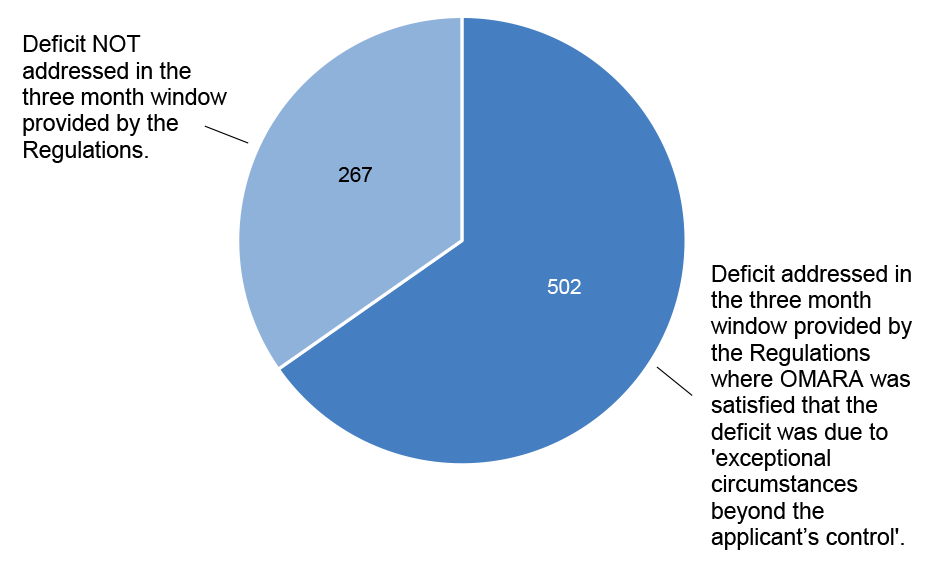

3.6 The Migration Agents Regulations 1998 (the Regulations) require applicants to have completed activities worth at least 10 points within the 12 months ending on the day the application was made, and provide for an extension of three months if the Authority is satisfied that the applicant did not meet the requirements because of exceptional circumstances beyond the applicant’s control. Approved CPD providers are required to send in advice of attendees at CPD activities to the department (which can be used by the department to monitor whether agents are meeting their CPD obligations). The department’s data shows that 769 agents (three per cent of registrations over that period) that were registered between 2019 and 2023 had not accrued the required 10 CPD points in the 12 months prior to submitting their applications. After allowing for an additional three months after applications were submitted, the number of applicants who had not accrued 10 points reduced substantially to 267, a reduction of 65 per cent (see Figure 3.1). The proportion of applicants for which the deficit was not addressed in the three-month window increased from 14 per cent in both 2019 and 2020 to an average of 57 per cent from 2021 to 2023. In April 2024, the department advised the ANAO that:

The data extracted by the Department with the assistance of Dialog [the contracted service provider for the MARS system], indicates that the vast majority of the applications had met the CPD requirements at the time of application. However, for these identified cases the individual’s CPD records were not correctly linked in the system to the correct registration application.

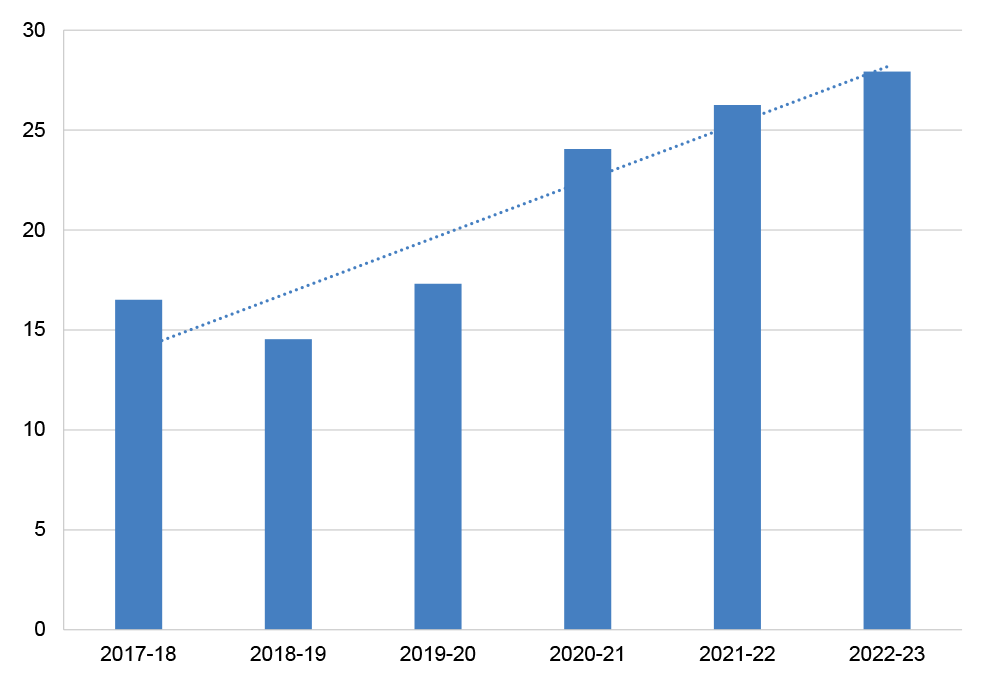

Figure 3.1: Applications submitted without the required 10 Continuing Professional Development points over the 12 months prior to lodging the application

Source: ANAO analysis of Home Affairs data.

3.7 As highlighted in Figure 3.1, there were 502 applications between 2019 and 2023 where the department’s actions indicate that the CPD points deficits were due to ‘exceptional circumstances beyond the applicant’s control’. While the department’s processes invite agents to identify the relevant exceptional circumstances, they do not require that the agent explain how those circumstances were beyond the applicant’s control, for example:

- an agent explained to the department he had been overseas20 during the 12 months without outlining how travelling internationally represented exceptional circumstances outside his control (or why he was unable to undertake the CPD remotely); and

- four applications were submitted by an agent in October 2019, October 2020, October 2021, and September 2023, in which the CPD requirements had not been met at the time the applications were made. On all four occasions, the department provided the agent with additional time to meet the requirements, notwithstanding that the agent had not claimed and provided supporting evidence, at the time of application, that exceptional circumstances beyond the agent’s control had prevented the agent from meeting the CPD requirements.

3.8 Home Affairs data held in MARS indicates that the applications of ten agents since 2009 have been refused on the basis of the agent not meeting the CPD requirements, the most recent of which was in 2018. The ANAO’s analysis is that 267 applications (as shown in Figure 3.1) were approved by the department between 2019 and 2023 without the 10 point deficit having been addressed either in the 12 months prior to lodging the application in which agents are expected to have completed the required amount of CPD (subject to exceptional circumstances beyond their control) or in the three month window provided by the Regulations. Of those 267, 29 applications received an ‘auto-granted’ approval since April 2021 (see paragraphs 2.15 and 3.17), while three were ‘deemed’ to have been approved (see paragraph 3.14), without having accrued 10 CPD points.

Recommendation no.5

3.9 The Department of Home Affairs assure itself that agents are registered only where they meet the continuing professional development requirements within the time period specified by the Migration Agents Regulations 1998.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

3.10 The Department agrees that it will take measures to strengthen quality assurance processes relating to the assessment that agents are registered only where they meet the continuing professional development requirements within the time period specified by the Migration Agents Regulations 1998 as set out in section 290A of the Migration Act 1958. The Department will pursue systems changes, undertake staff training and further develop support materials to contribute to the strengthening of quality assurance processes.

Late repeat applications to re-register

3.11 Section 299 of the Migration Act provides that the registration of a registered migration agent ends 12 months after the day of registration. To remain registered and to continue to lawfully provide immigration assistance, agents are required to submit an application to re-register prior to the expiry date. Under Section 306B of the Migration Act, if an agent has not submitted a repeat application prior to the expiry date, the agent becomes an ‘inactive migration agent’ for a period of two years (unless the agent registers again within that two-year period).

3.12 While an agent ceases to be an ‘inactive migration agent’ after the two-year period, the Regulations define a repeat registration as one where the applicant has previously been registered at some time within the period of three years before making the application. This is reflected in the department’s Registrations and CPD SOP, which states that a person has up to three years to submit a late repeat application.

3.13 Automated reminders are sent to RMAs that their registration is due for renewal at 60 days, 30 days and 14 days prior to expiry. Nonetheless, over six per cent of repeat applications since 1 July 2016 are late repeats.21

Deemed applications for registration

3.14 Under section 300 of the Migration Act, repeat registration applicants who make a registration application and pay the application charge before their current registration expires will automatically continue to be registered and may continue to provide immigration assistance until:

- a decision is made on the application, or

- a decision is made to suspend or cancel the agent’s registration, or

- a period of 10 months has passed since the day after the applicant’s registration expired. At the end of the 10-month period, the RMA’s application for registration is taken to have been granted or ‘deemed’.

3.15 The department’s data shows that agents for which there are serious integrity concerns22 are having their repeat applications to register ‘deemed’ rather than approved by the department, often for multiple years. For example, 40 per cent of the agents identified by the department as suspected of facilitation of criminal enterprise (see paragraph 3.57) have had their registration applications ‘deemed’.23 Based on the Explanatory Memorandum as well as the drafting instructions for the amendments to the Migration Act in 2002 that introduced the deeming provision, this was not the intended purpose of the deeming provision.

3.16 Examples of where applications for repeat registration have been deemed have included:

- an agent for whom the department recorded that it had, since 2009, received a number of allegations relating to matters that included possible fraudulent visa applications, and was identified by the department as a facilitator of fraudulent visa applications in November 2017. The agent has also been the subject of 21 complaints. Each annual registration for this agent has been deemed since 2020, while being the subject of three open complaints. The last time the department approved the agent’s application on the basis of a finalised assessment of the re-registration application was in October 2019;

- an agent for whom the department had integrity concerns since at least 2015 and was the subject of nine complaints received between 2014 and 2019 (all of which were dismissed by the department), had been ‘deemed’ for four consecutive years between 2016 and 2019 before the agent’s application for re-registration was refused in June 2020; and

- an agent that is the subject of an open complaint (as of February 2024) that was submitted in June 2019 relating to fraudulent and/or criminal behaviour, had been ‘deemed’ in November 2020, November 2022, and November 2023. In relation to that complaint:

- the complaint was submitted to the department in June 2019;

- a section 308 notice was issued to the agent 34 months later in April 2022 requesting a statutory declaration and supporting information relating to the complaint;

- the agent responded to the notice the same month;

- in February 2023, the agent’s legal representative contacted the department for information about the status of the complaint. The department did not respond;

- the agent’s legal representative again contacted the department in July 2023 outlining concerns that it was over a year since the agent had responded to the section 308 notice and that he had not received a reply to his email of February 2023. In response, the department advised that the legal representative’s correspondence on behalf of the agent was ‘on file’;

- the department requested further information from the agent in July 2023, a further 15 months since issuing and receiving a response to its section 308 notice, and over four years since receiving the complaint; and

- as of February 2024, the complaint remains open and the department has not issued a section 309 notice to the agent regarding the complaint.

Automated registration approvals

3.17 As mentioned at paragraph 2.15, in April 202124, the department implemented an automated decision-making process for the approval of applications for repeat registration.25 MARS, used by the department to manage RMA registration, CPD providers, complaints against RMAs, and consumer enquiries, automatically approves an application for repeat registration (or re-registration) based on certain criteria. The criteria include, but are not limited to: agent experience (the date first registered is greater than 12 months); character (the agent’s answer must be ‘no’ to the questions set out in relation to the agent’s integrity and fitness and propriety to provide immigration assistance); complaints (no open complaints and two or less closed complaints in less than 5 years); OMARA disciplinary action (the agent must not have been subject to a caution, suspension, cancellation or barring).

3.18 Fifty-nine per cent of repeat registrations have been subject to automated approval since April 2021.

3.19 Those repeat registrations being ‘auto-granted’ rather than having a departmental officer assess the application have included, similar to the department’s approach to the deeming provisions outlined above, agents for which the department holds integrity concerns. For example, an agent’s application for repeat registration was ‘auto-granted’ after a complaint related to fraud and/or criminal behaviour was dismissed by the department notwithstanding that it had ‘residual concerns’.

- The agent was first registered in July 2018. The agent’s first repeat registration was ‘deemed’ as approved in May 2020 and the most recent application received an ‘auto-granted’ approval in July 2023.

- The agent has been the subject of one complaint. The complaint was a referral from another area of the department that was submitted in August 2019 and related to allegations of fraud and/or criminal behaviour. Notwithstanding the serious nature of the allegations, the department recorded in its risk assessment a score of ‘minor’.

- The department dismissed the complaint three years later in August 2022 with a primary outcome recorded as ‘insufficient evidence’.

- In dismissing the complaint, the department did not exercise any of its available regulatory powers to investigate the complaint. For example, the department did not issue notices under sections 305C or 308 of the Migration Act to require the RMA to give information or documents.

- The department recorded that it had ‘residual concerns’ about the agent’s likely involvement in the alleged activity. Nevertheless, approval of the agent’s repeat application to register was ‘auto-granted’ the following year in July 2023.

3.20 Further examples include:

- an agent’s application for repeat registration was ‘auto-granted’ approval in September 2023, notwithstanding that the agent had been the subject of an earlier complaint resulting from an intra-departmental referral involving allegations of criminal and/or fraudulent behaviour. The department dismissed the complaint as having ‘insufficient evidence’ 17 months after receiving it, during which time the department had not issued any notices to the agent or exercised any of its regulatory powers to investigate the complaint.

- an agent’s applications for repeat registration were ‘auto-granted’ approval in November 2021 and November 2022, after three complaints had been received against the agent, one of which had resulted in the department finding that the agent had breached the Code of Conduct. No disciplinary action was taken by the department. Another complaint was finalised by the department as having been ‘addressed with agent’ (which is not a disciplinary action prescribed in the Migration Act). The agent is the subject of a fourth complaint, which the department identified as of ‘high risk’ of fraud and criminal behaviour, received in March 2023, four months after the most recent of the two ‘auto-granted’ approvals.

- an agent’s application for repeat registration was ‘auto-granted’ approval in March 2022. The agent had been the subject of five complaints between 2010 and 2019, including two complaints received in 2018 and 2019 related to fraud and/or criminal behaviour that the department dismissed as having ‘no permission to publish’. This means the complainant did not agree to have the details of their complaint provided to the agent (the functions of OMARA under the Migration Act includes investigating complaints, and this is not limited to only complaints where the complainant has agreed that details of the complaint be provided to the agent26 (see also Case Study 1 in Appendix 3)). While the department advised the ANAO in October 2023 that, ‘[w]here warranted and where the matter is serious, the OMARA can commence an own motion investigation to source evidence that would not reveal the complainant’s identity’, this was not the case for either of these two complaints.

Powers to obtain information to inform registration refusal and sanction decisions

3.21 The Migration Act (section 305C) provides a power for OMARA to, by written notice to the agent, require him or her to provide prescribed information or prescribed documents in circumstances where it is considering refusing a registration application or making a decision to cancel or suspend an agent’s registration, or cautioning an agent.27 In December 2023, Home Affairs advised the ANAO that:

there may be very clear reasons why the OMARA may not exercise the power in section 305C of the Act. These may include, for example, where:

- evidence has already been obtained from the relevant RMA under section 308 of the Act initially28

- evidence is already available to support the allegations

- the OMARA is not considering sanctioning the agent due to the OMARA having determined that available evidence does not support the allegations (or not considering refusing a registration application).

3.22 Analysis did not support the department’s advice as to why it may not exercise the power provided by section 305C. For example, an agent’s applications for registration and re-registration had been approved annually between 2005 and 2022 (although on four occasions the applications were ‘deemed’ to have been approved (see paragraphs 3.14 to 3.16). Between 2006 and 2019, 15 complaints had been made against the agent, including allegations related to undeclared assistance and misrepresentation. The department stated in a brief to the Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs in November 2022 that ‘All 16 [sic] complaints were investigated and dismissed, due mainly to insufficient evidence’. In the matter/s covered in the brief, the department had not:

- issued notices under sections 305C or 308 of the Migration Act to require the RMA to provide information; nor

- at any time considered whether it should reopen prior complaints that were relevant to the allegations at hand.

3.23 The department did not advise the minister that it had not used the powers available to it.

3.24 The agent’s registration was cancelled in December 2022, 15 months after a complaint was submitted by another area of the department in September 2021 relating to undeclared assistance, and one month after media reporting (see paragraphs 3.39 and 3.40), which the department identified as alleging the agent was engaged in conduct which undermined the migration law.29

3.25 In February 2024, the department advised the ANAO that it accepts that it needs to ‘uplift its capabilities’ to use the Migration Act powers without specifying the regulatory actions it plans to undertake. Of the 50 examples/case studies of completed/closed cases raised by the ANAO with the department as part of this performance audit, there was only one (see paragraph 3.52) where the department indicated OMARA is considering whether further action might have been, or is, warranted. In April 2024, Home Affairs advised the ANAO that:

the Department considers that an increase in administrative investigative capabilities includes everything on the continuum – governance, SOPS, procedures, team structures and functions, training and development, skilled and qualified staff, case management system and reporting capabilities, sophistication of evidence collection capabilities (access to systems, intelligence gathering and skilled staff trained to navigate and interpret those systems and intelligence/information), consideration of all powers available to the OMARA and future powers and identifying and using levers from other functions and capabilities across the Department, working with key stakeholders both internal and external with dual interests, streaming decision making (focus on key allegations, well-reasoned and evidence based decisions, timeliness etc), quality review processes etc.

Recommendation no.6

3.26 The Department of Home Affairs strengthen its regulation of migration agent registration requirements by making greater use of the powers provided to it by the Migration Act 1958 to inform an assessment of whether applications for registration should be granted.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

3.27 The Department agrees that it is important to make use of the powers available to the Authority under the Migration Act (such as through issuing a Notice under sections 288B, 305C, 308 or 309), where it is relevant, appropriate and lawful to do so.

3.28 The Department will continue to enhance its ability to appropriately assess whether an application for registration should be granted having regard to available evidence before the Authority including through the exercise of relevant powers under the Act. The Government has agreed to implement an AusCheck scheme to undertake a background check for all registered migration agents, to replace the existing requirement to provide a National Police Check. This will strengthen the assessment of the character requirements for registration to ensure individuals applying to become RMAs are more thoroughly vetted before they can register and at subsequent renewals of their registration. The OMARA will implement these changes subject to the passage of legislation through Parliament.