Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Department of Health’s Coordination of Communicable Disease Emergencies

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health's strategies for managing a communicable disease emergency.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Outbreaks and epidemics of communicable disease can cause enormous social and economic disruption. In 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome spread across four continents and cost the global economy between US$13 billion and US$50 billion.1 The 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic killed between 151 700 and 575 000 people worldwide, with 37 000 Australian cases resulting in over 5 000 hospitalisations and nearly 200 deaths.

2. In Australia, state and territory governments are primarily responsible for managing communicable disease emergencies within their respective jurisdictions. The Commonwealth Department of Health (Health) may become involved when a national response is required, and its primary role is one of coordination.

Audit objective and criteria

3. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Health’s strategies for managing a communicable disease emergency.

4. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- Health has a robust framework in place to prepare for a potential communicable disease emergency; and

- Health has effective arrangements in place to respond to a communicable disease emergency.

Conclusion

5. Health responded effectively to the three communicable disease incidents examined. The department has developed strategies to manage its coordination role for communicable disease emergencies and collects sufficient information to identify communicable disease incidents. The systems and processes that support the strategies could be improved.

6. Health’s communicable disease plans do not clearly define in what circumstances and to what extent the department will become involved in a communicable disease emergency and Health’s administrative process and public communications could be improved. The department has made progress towards addressing approximately half of the lessons learnt through previous communicable disease emergency reviews and responses, but does not record or assess its progress towards implementation.

Supporting findings

7. Health has developed communicable disease plans, a risk plan and has identified potential improvements to communicable disease preparedness that are outlined in the National Framework for Communicable Disease Control. The risk plan does not identify the areas that require improvement.

8. Health has systems and processes in place, and collects information from a range of sources, to identify communicable disease incidents.

9. Health’s guidance material is not current and comprehensive and its communicable disease incident management systems do not provide Health with assurance that incidents are managed effectively.

10. Health conducts tests and exercises to determine its level of preparedness but does not have a structured process to ensure that lessons from tests, exercises, responses and reviews are implemented.

11. The Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance is the key governance document specific to communicable disease emergencies, but it does not clearly articulate the circumstances in which Health will respond to a communicable disease incident. The terminology used to describe communicable disease emergencies and the events that trigger a national response vary across different governance documents.

12. Health has effectively coordinated a response for three recent incidents. However, Health’s processes are not always timely or well documented when transitioning through the response stages.

13. Health’s primary means of communicating with the public about communicable disease is through its website. The website contains out-of-date information, and does not always provide relevant information about communicable disease in a timely manner.

14. Health has addressed or partially addressed approximately half of the relevant recommendations and lessons learnt from five recent reviews relating to communicable disease emergencies. Health has not developed a plan to monitor their implementation.

Recommendations

Recommendation No.1

Paragraph 2.33

Mandate the use of an effective incident management system to manage communicable disease incidents and notifications.

Department of Health’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation No.2

Paragraph 3.30

Ensure Health’s public communication regarding communicable disease incidents is consistent, accurate and timely.

Department of Health’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation No.3

Paragraph 3.34

Develop a process to record, prioritise and implement lessons and agreed recommendations from tests, exercises, communicable disease emergency responses and relevant reviews.

Department of Health’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

15. The Department of Health’s summary response to the report is provided below, and its full response is at Appendix 1.

I am pleased that the ANAO found that Health has developed strategies to manage its coordination role for communicable disease emergencies and that it responded effectively to the three communicable disease incidents examined. The report also concluded that Health is able to detect communicable disease incidents, a critical first step to managing a response.

The report has highlighted important areas for improvement in order to strengthen the systems and processes that support response strategies, particularly with regard to ensuring that the documentation of processes is comprehensive and timely, and that a process for implementing lessons learnt from tests, exercises, responses and reviews is in place. The report identified that the Communicable Disease Plan could better describe the circumstances in which Health will get involved in an emergency and Health acknowledges that this new emergency response plan is still being trialled and refined, and that roles and responsibilities and language could be further developed.

Health acknowledges public communications is a critical component of emergency response. The timeliness of this information is given a high priority during a response; however, Health agrees that improvements could be made when a response is stood down.

The Department of Health’s implementation of the ANAO’s recommendations will further ensure that the Australian Government is able to provide effective coordination of the prevention, preparedness, detection and response activities of communicable disease emergencies.

1. Background

Communicable disease

1.1 Outbreaks and epidemics of communicable disease can cause enormous social and economic disruption. In 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome spread across four continents and cost the global economy between US$13 billion and US$50 billion.2 The 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic killed between 151 700 and 575 000 people worldwide, with 37 000 Australian cases resulting in over 5 000 hospitalisations and nearly 200 deaths.

1.2 A number of recent outbreaks of diseases such as Ebola virus disease and Zika virus have shown that communicable diseases remain a threat to human populations. In an increasingly globalised world, nation states have a responsibility to their own citizens and the global population to minimise the spread of disease.

Communicable disease management

1.3 The management of communicable disease is governed by a range of legislation and plans (outlined in Appendix 2). On a day-to-day basis, the Commonwealth Department of Health’s (Health’s) responsibilities for communicable disease management are focussed on coordination. Health acts as a national focal point for distribution of health related information3 and maintains the national incident room and medical stockpile.

1.4 States and territories have primary responsibility for managing communicable disease emergencies within their jurisdiction. This includes surveillance, identification of, and response to communicable disease. Cooperation and collaboration between Health and the states and territories is essential to ensure information is shared and potential health risks are identified early.4

Communicable disease emergencies

1.5 This report uses the term communicable disease emergency to describe an outbreak of disease that may lead to Australian Government intervention. The term emergency is widely used by state and territory health authorities and is understood by the general public.

1.6 The department recently adopted the term Communicable Disease Incident of National Significance (CDINS) to describe a communicable disease incident that requires implementation of national policy, interventions and public messaging, or deployment of Commonwealth or inter-jurisdictional resources to assist affected jurisdictions.5

1.7 According to the Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance (CDPlan), factors which may be considered when determining whether a communicable disease requires national intervention include:

- a request for assistance by a state or territory in managing the health aspects of a response;

- the health system’s response resources are overwhelmed;

- there is a need for national leadership and coordination;

- there is an international communicable disease incident with implications for Australia; and

- the incident presents complex political management implications.

Responsibility for communicable disease emergencies

1.8 Australia’s communicable disease emergency response arrangements are based on the premise that health authorities and healthcare providers are in a constant state of preparedness and response. For example, disease surveillance, identification and treatment occur on an ongoing basis. Similarly, health protection committees meet regularly to assess information gathered through those ongoing activities. The CDPlan states that transitioning from routine response to an emergency response is likely to represent an escalation in the scale or complexity of existing activity.

1.9 The states and territories control most functions essential for effective prevention, preparedness, response and recovery. This includes the operational aspects of surveillance, identification, containment and treatment of communicable disease within their own jurisdictions, in particular:

- detecting and reporting communicable disease incidents;

- working with local government, business and the community to implement response measures; and

- managing cross-border events on a cooperative basis and providing assistance to other states and territories when necessary.

1.10 In the case of a major communicable disease incident that involves multiple states or territories, or has the potential to overwhelm state or territory resources, a nationally coordinated approach may be required. Where it has been agreed that a state or territory requires assistance in managing the health aspects of a response, Health would be the lead agency to coordinate response activities. Forms of assistance that may be provided by Health include: coordination; communication; consultation; facilitation of laboratory services; secondment of personnel to affected areas; financial assistance; and deployment of the national medical stockpile.

1.11 In 2005, Health established the Office of Health Protection (OHP) to expand its emergency response capability. The mission of OHP, in partnership with key stakeholders, is to protect the health of the Australian community through effective national leadership and coordination, and building of appropriate capacity and capability to detect, prevent and respond to threats to public health and safety. This includes threats posed by communicable disease emergencies. OHP is a division within Health and employed 132 staff as at 30 June 2016.6

Governance structure

1.12 The management of communicable disease emergencies is governed by a range of regulations, frameworks, plans and agreements. The primary governance documents relevant to communicable disease emergencies are listed at Appendix 2.

1.13 Health protection committees provide the forums for ongoing communication and coordination between Health and the states and territories (see Table 1.1). The Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC), chaired by Health’s Chief Medical Officer, is the committee responsible for national coordination of emergency operational activity in health emergencies.7 AHPPC and its standing committees are the primary forums in which the Australian Government and state and territory governments share resources, information, expertise and decision making.8

Table 1.1: Health protection committees with communicable disease responsibility

|

Committee |

Key functions relevant to communicable disease emergency |

Summary of membership |

|

Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) |

Coordinate national emergency operational activity. Promote alignment of state and territory strategic plans. Coordinate national response. Facilitate communications between relevant organisations. Prepare for emerging health threats through exercises and planning. |

Chief Medical Officer of Australia Chief Health Officer of each state and territory Clinical experts Australian Government representatives |

|

Communicable Disease Network Australia (CDNA) |

Coordinate surveillance, investigation and control of multi-jurisdictional outbreaks of communicable disease. Coordinate national technical aspects of communicable disease surveillance and response. |

Public health physicians from each state and territory Clinical experts Australian Government representatives |

|

Public Health Laboratory Network |

Provide advice on laboratory resources and improve capacity to respond to communicable disease. |

Clinical experts in public health microbiology |

|

National Health Emergency Management Standing Committee |

Address the operational aspects of disaster medicine and health emergency management. |

Australian Government representatives State and territory government representatives |

|

Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation |

Provide technical advice on immunisation issues. |

Clinical experts Consumer representative General practitioners |

Note: CDNA, Public Health Laboratory Network, National Health Emergency Management Standing Committee and Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation are standing committees of AHPPC.

Source: Health, CDPlan, pp. 15–16.

Audit approach

1.14 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Health’s strategies for managing a communicable disease emergency.

1.15 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- Health has a robust framework in place to prepare for a potential communicable disease emergency; and

- Health has effective arrangements in place to respond to a communicable disease emergency.

1.16 The ANAO assessed Health’s plans, policies and procedures relating to communicable disease emergencies, and reviewed response activities for a number of health related incidents. The audit team also sought input from relevant Australian Government agencies, state and territory health authorities, private sector stakeholders and Health personnel.

1.17 The audit focused on Health’s management of communicable diseases that are transmissible between humans, and also between humans and animals or insects. It did not address communicable disease originating from food borne pathogens or environmental factors and did not examine arrangements at the state and territory level.

1.18 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $378 000.

1.19 The team members for this audit were Benjamin Siddans, Jennifer Myles, Lucy Donnelly and Deborah Jackson.

2. Preparing for a communicable disease emergency

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Health has a robust framework in place to plan for and identify a potential communicable disease emergency.

Conclusion

Health has developed strategies to manage its coordination role for communicable disease emergencies and collects sufficient information to identify communicable disease incidents. The systems and processes that support the strategies could be improved.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at mandating the use of an effective incident management system.

Has Health planned for a communicable disease emergency?

Health has developed communicable disease plans, a risk plan and has identified potential improvements to communicable disease preparedness that are outlined in the National Framework for Communicable Disease Control. The risk plan does not identify the areas that require improvement.

Legislation and plans

2.1 The Department of Health’s (Health’s) responsibilities in relation to communicable disease emergencies are established in a series of agreements and legislation. At a high level, Health’s role as Australia’s National Focal Point is established by the International Health Regulations. These are given effect by the National Health Security Act 2007 (the Act). The National Health Security Agreement (the Agreement) is the means through which the Commonwealth and the states and territories have agreed roles and responsibilities for sharing information regarding communicable disease incidents. It also defines the criteria for determining a Public Health Event of National Significance to be reported to the National Focal Point.9 The Biosecurity Act 2015 provides for a series of powers to support emergency response actions that may be implemented to assist with managing specific diseases.10

2.2 Beneath Health’s enabling legislation, a number of plans have been developed to assist in the coordination of communicable disease emergencies. The Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance (CDPlan) is the primary communicable disease response plan and is designed to be applied to any communicable disease emergency for which there is no disease specific plan. There are currently two disease-specific plans—the Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (AHMPPI) and the Poliomyelitis Outbreak Response Plan for Australia. These arrangements are summarised in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Interaction of legislation, frameworks and plans relevant to communicable disease

Source: ANAO analysis of various Australian Government and Department of Health documents.

Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance

2.3 The CDPlan, finalised in 2016, is intended to facilitate a generic and flexible approach to communicable disease hazards. The plan is a hazard specific sub-plan of the National Health Emergency Response Arrangements11, and is intended to sit above disease specific plans. The CDPlan notes that where disease specific plans are available, these are the primary plans to be used if the disease arises.

Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza

2.4 The AHMPPI was revised in 2014 following a review of the response to the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009. The plan is disease-specific to pandemic influenza, and provides a broad range of guidance for a response. The AHMPPI is a stand-alone document, and includes specific activities to be conducted when preparing for and responding to a pandemic. It also defines roles and responsibilities for key stakeholders.

Poliomyelitis Outbreak Response Plan for Australia

2.5 The current version of the Poliomyelitis Outbreak Response Plan for Australia was developed in 2014. The plan is disease-specific to poliomyelitis and includes detail on investigating and responding to suspected and confirmed poliomyelitis cases in Australia.

Future Directions

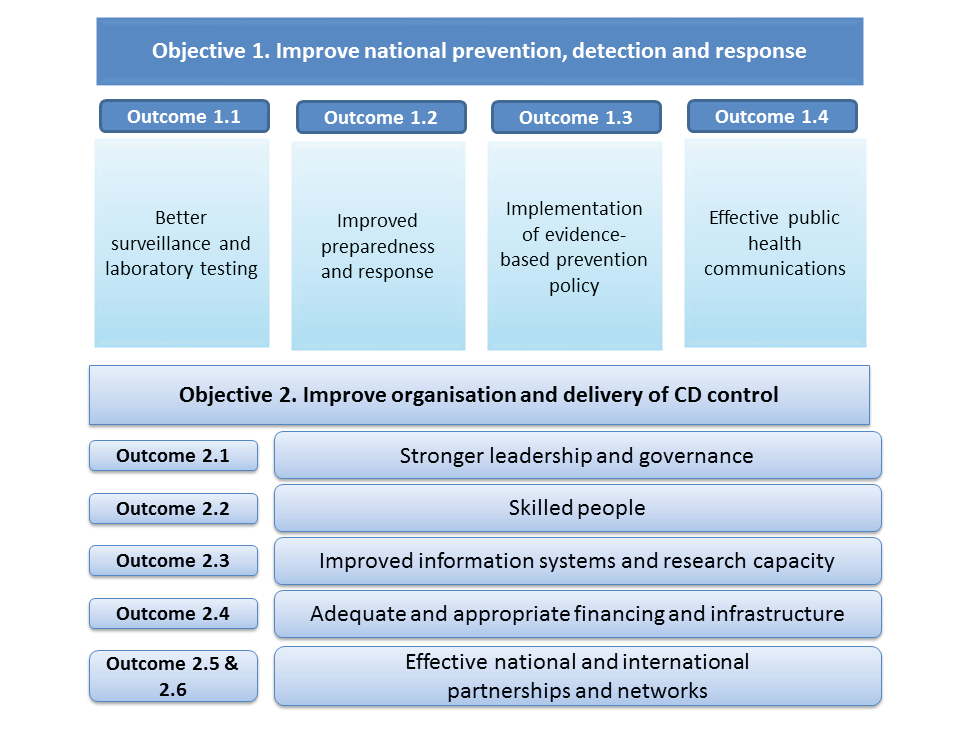

2.6 In 2014, the Communicable Disease Network Australia (CDNA), supported by Health, developed a document titled the ‘National Framework for Communicable Disease Control’ (the CD Framework). The document does not articulate the framework in which communicable disease is currently managed. Rather, it seeks to identify shortcomings in the current system, recommend potential improvements to existing arrangements and articulate options for achieving those improvements. An implementation plan was drafted in 2016. The plan categorises the recommended improvements into two objectives and ten outcomes as shown in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: National Framework for Communicable Disease Control Implementation Plan—objectives and outcomes

Source: Department of Health, National Framework for Communicable Disease Control Implementation Plan, 2016 (Draft), p. 5.

2.7 Health’s priorities are outcomes 1.1, 2.1 and 2.3 and the following specific activities have been identified against these outcomes:

Table 2.1: National Framework for Communicable Disease Control draft implementation plan priority activities

|

Outcome |

Activity |

|

1.1 |

Identify and agree core functions of Australia’s public health laboratory system required for communicable disease control. |

|

1.1 |

Targeted integration of specialised laboratory testing data with existing surveillance. |

|

1.1 |

Embed continuous quality improvement of surveillance systems through development of surveillance standards/plans for all notifiable diseases. |

|

2.1 |

Optimise the governance of the Communicable Diseases Network Australia (CDNA) to preserve and improve its ability to perform as the principal technical advisory committee in communicable disease control in Australia. |

|

2.1 |

Build national capacity to conduct risk assessment for decision support and to inform risk communications in communicable disease control, especially during crises or outbreaks. |

|

2.3 |

Work towards achieving nationally inter-operable disease surveillance and outbreak management systems. |

|

2.3 |

Make surveillance data more accessible through improved public facing formats and interactive outputs of surveillance systems. |

|

2.3 |

Strengthen engagement with the research sector in communicable disease control through key national partnerships. |

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.8 The draft plan has not been costed, it does not include timeframes, and responsibilities for completion of specified activities have not been assigned.12

Assessing the risk of a communicable disease emergency

2.9 The Office of Health Protection (OHP) has developed a risk management plan for the period July 2016 to June 2017. The detailed plan includes OHP’s assessment against 11 departmental risks and 10 risks specific to the division. All 21 risks are rated as medium, 19 were deemed acceptable and require no additional treatment. For two risks, the plan did not record whether the risk was acceptable or required treatment.

2.10 Health advised the ANAO that surveillance is the primary control activity for communicable disease threats. Surveillance is included as a source of risk in relation to data collection at the departmental risk level. This risk indicates that the current controls are effective and require no further treatment.

2.11 The risk plan is not aligned with the CD Framework. For example, the risk plan indicates that the risks associated with poor surveillance are acceptable and require no additional treatment. The CD Framework indicates that current surveillance systems, and effective response, are compromised by system limitations.

2.12 Under the CDPlan, Health is responsible for national risk assessment in the event of a communicable disease emergency. Health has conducted risk assessments for communicable disease incidents. For example, a comprehensive risk assessment was conducted in January 2016 for Zika virus following reports of a possible correlation between Zika virus and birth defects. Health addressed the likelihood and consequences of the disease, allocated risk ratings13 and identified five possible risk mitigation options. A second risk assessment was conducted in June 2016 at the request of the Chief Medical Officer.

Does Health have systems and processes in place to identify communicable disease incidents?

Health has systems and processes in place, and collects information from a range of sources, to identify communicable disease incidents.

2.13 Health collects surveillance data from various sources, including:

- data aggregated from states and territories;

- the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System;

- notifications from focal points in other countries;

- information from the World Health Organization of outbreaks in international jurisdictions;

- Australian health protection committees; and

- sentinel surveillance systems such as the Australian Sentinel Practice Research Network.14

2.14 The key data sources are described below. Health uses this surveillance data to identify outbreaks of communicable disease and national trends.

National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System

2.15 Each state and territory uses its own surveillance system to record communicable disease data. Health’s National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS) acts as a central collection point for notifications sourced from the states and territories. Health received 324 665 such notifications in 2015. The diseases that must be reported to Health for inclusion in the NNDSS are defined in the National Notifiable Disease List, which as of January 2017 contained 69 diseases.15 One or more cases, or potential cases of a disease on this list is considered to be a public health event of national significance.

2.16 Health uses the NNDSS data to produce publicly available reports of disease occurrence.16 The reports are generated fortnightly and provide state and territory breakdowns of disease incidents, and comparisons to previous historical periods.

National Focal Point

2.17 The International Health Regulations establish the need for signatory nations to establish a National Focal Point that will act as a liaison point with the World Health Organization and public health bodies within each nation. The Act establishes the Secretary of the Department of Health as the National Focal Point for Australia.

2.18 As the National Focal Point, Health receives notifications from states, territories, and other countries regarding communicable disease incidents. For incidents involving travellers who may have contracted a communicable disease, Health is responsible for notifying the relevant jurisdictions that these people have travelled to, so that public health bodies can arrange an appropriate response and contact affected travellers, if required. Health responded to approximately 140 such incidents in 2016.

Health protection committees

2.19 Health may also be informed about communicable disease incidents by state and territory representatives at health protection committees.

2.20 The following case study demonstrates how a communicable disease incident was identified using information from state authorities, as well as NNDSS data, with coordination provided through the committee system.

|

Case study 1. Identification of invasive meningococcal disease, serogroup W |

|

In a July 2015 meeting of CDNA a state representative advised that the year-to-date number of invasive meningococcal disease, serogroup W (meningococcal W) it had experienced was higher than previous years. The State undertook an investigation of the outbreak and continued to provide updates to CDNA, resulting in the formation of a working group to further monitor the issue. NNDSS data was used to provide updates of identified meningococcal W cases at a national level. This process is discussed further in Chapter 3. |

Do Health’s systems and processes assist in preparing for a communicable disease emergency?

Health’s guidance material is not current and comprehensive and its communicable disease incident management systems do not provide Health with assurance that incidents are managed effectively.

Procedures and guidance

2.21 The CDPlan establishes the concept of a Communicable Disease Incident of National Significance (CDINS), the declaration of which would prompt a coordinated response led by Health. The ANAO observed that the CDPlan does not clearly articulate the decision-making criteria by which Health determines if a CDINS exists (discussed further in Chapter 3).

2.22 The ANAO assessed a sample of tasks detailed in the CDPlan to determine whether appropriate guidance exists. The results are shown at Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Guidance for Health’s communicable disease emergency responsibilities

|

Health emergency responsibilitya |

Does appropriate guidance exist? |

|

National risk assessment |

No |

|

Maintain capacity for surveillance within Australia |

Yes, but the NNDSS manual has not been updated since 2011 and no longer reflects current processes. |

|

Identify potential communicable disease emergency incident |

Process is described in CDPlan, but it does not accurately reflect Health’s decision making criteria (see Chapter 3). |

|

Conduct rapid assessment |

No |

|

Establish health incident management teamb |

Yes |

|

Develop incident action plan |

Yes |

|

Operate the national incident room as contact and coordination point for Health’s role in an emergency |

Yes, but the procedure does not specify timeframes for response to all incidents or provide guidance as to urgency of incidents.c The process for undertaking contact tracing is inconsistent with CDNA guidance. |

|

Deployment of the national medical stockpile |

Yes, but the deployment procedure does not reflect the new contractor arrangements (see paragraph 2.39). |

Note a: Responsibilities have been extracted from various sections of the CDPlan and listed in the order in which they would occur in practice.

Note b: Incident Management Teams and Incident Action Plans are developed by Health on a per-incident basis to internally manage Health’s response to an emergency. Health’s response to emergencies is discussed further in Chapter 3.

Note c: Health’s standard operating procedures require that contact tracing for measles and invasive meningococcal disease be actioned immediately, and tuberculosis and Legionnaire’s disease contact tracing be actioned as soon as possible during the Watch Officer’s shift. Timeframes for responding to other incidents are left to the judgement of the Watch Officer.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health’s guidance material relevant to managing communicable disease emergencies.

2.23 Health should review its guidance material for managing communicable disease emergencies and ensure it is up-to-date and covers the full range of its responsibilities as outlined in the governance documentation listed at Appendix 2.

National Incident Room

2.24 Health uses the National Incident Room (NIR) to coordinate a national health response to a public health event of national significance. The NIR telephone number and email accounts are also monitored continuously by a designated Watch Officer during business hours, and a rotating Duty Officer after hours.17

2.25 To prepare for a CDINS, Health maintains a register of 108 staff that could be drawn upon to staff the NIR in an emergency. The NIR Workforce standard operating procedure specifies that NIR staff must complete mandatory induction training. Health’s incident management system indicates that 59 per cent of registered staff have not completed induction training.18 This limits the assurance available to Health that its staff are appropriately trained and can operate the NIR in the event of an emergency.

National Medical Stockpile

2.26 The National Medical Stockpile is a strategic reserve of drugs, vaccines, antidotes and protective equipment for use in the national response to a public health emergency which could arise from natural causes or terrorist activities.19 Health is responsible for ensuring that the stockpile is maintained in preparation for a deployment in response to a CDINS.

2.27 ANAO Audit Report No.53 2013–14 examined the National Medical Stockpile and made four recommendations. Health has completed these recommendations.

Systems for incident management

2.28 Health has two systems for managing incidents and emergencies:

- an email-based system, consisting of a shared email account with a series of sub-folders for specific incidents, topics or issues; and

- a commercial incident management system.20

2.29 The incident management system is not used to its full capability. It is used primarily for the initial registration of incidents. Following this, the shared email account is used for the majority of incident management and monitoring tasks.

2.30 The shared email account does not facilitate effective monitoring of notifications or incidents. It does not have the functionality to manage the allocation, status or completion of tasks, or record the time taken to do so. The number of notifications and incidents received are calculated through manual counts of incoming email correspondence. Some examples of incidents that have been poorly managed through the shared email account are included in Case Study 2.

2.31 The incident management system is underutilised. Health advised the ANAO that the system does not provide the required functionality. Health has not undertaken an analysis of the additional functionality it requires to manage incidents. The ANAO notes that the system provides functionality not available in the shared email account, such as:

- assigning tasks to specific individuals;

- tracking tasks;

- workflows to automatically manage tasks and issue alerts;

- centralising correspondence and communications (including text messages and telephone conversations);

- recording issues and lessons and assigning them to staff for action, and

- an auditable log of tasks and activities performed.

2.32 Although Health has not analysed the functionality it requires, in December 2016 it renewed its licence for the incident management system for one year.

Recommendation No.1

2.33 Mandate the use of an effective incident management system to manage communicable disease incidents and notifications.

Department of Health’s response:

2.34 Agree, noting Health is currently undertaking work to better utilise the existing incident management system.

Management of tasks and priorities

2.35 The absence of a single incident management approach presents risks for the effective management of tasks and information in an emergency response. The ANAO analysed 12 recent incidents to determine the extent to which they were managed effectively.21 No issues were identified in seven of the incidents. For five incidents, issues were observed that related to management of contact information, completing necessary response tasks, timeliness of response, and clear documentation of actions taken. These issues are summarised in the following case study.

|

Case study 2. Examples of incident management issues |

|

Example 1: Unmaintained contact information In the course of responding to a notification, a state public health authority informed Health on 6 January 2017 that the contact details Health had supplied for an airline were incorrect, and provided updated contact details. As of 1 February 2017, Health had not updated the airline contact information in its incident management system. Example 2: Incomplete action A state public health authority notified Health on 5 January 2017 that a passenger on an international flight to Australia was infected with measles, and requested Health notify other jurisdictions to allow them to inform passengers who may have travelled further. Health was prompt in notifying Australian jurisdictions. Health advised the state authority it would also notify the country from which the flight originated, but did not do so. Example 3: Delayed response A state public health authority notified Health on 11 January 2017 that a passenger had travelled to another country prior to completing treatment for tuberculosis, and requested Health advise that country’s national tuberculosis program. Health requested further information from the state on 19 January 2017, which was provided within 10 minutes. Health notified the country of the incident on 20 January 2017. Example 4: Delayed response On 23 December 2016 a state public health authority advised Health that a patient may have been exposed to legionella pneumophila while staying in a hotel overseas one month previously. Health staff determined that a notification should be sent to the focal point of the relevant country for advice. Health sent the notification on 12 January 2017. The country requested additional information the same day, but the request was misfiled. Health responded to a follow-up request for further information on 9 February 2017. Example 5: Response unclear Health received notification in the morning of 22 December 2016 from another country that a passenger who had travelled on flights to, within and from Australia had been diagnosed with tuberculosis and was potentially infectious at the time of travel. Health acknowledged the notification in the afternoon of 23 December 2016. Health requested passenger travel data from the relevant airline and other Commonwealth entities on 9 January 2017. Health was advised on 11 January 2017 that requested data was ready for delivery, but as of 1 February 2017 no further action has been recorded. |

2.36 Responses to these incidents occurred during a period in which Health was not engaged in an emergency response.22 Health could improve its ability to manage its workload in an emergency by defining incident priorities and acceptable response timeframes, and monitoring performance against these targets.

Does Health review and test its level of preparedness?

Health conducts tests and exercises to determine its level of preparedness but does not have a structured process to ensure that lessons from tests, exercises, responses and reviews are implemented.

Capability audits and reviews

2.37 In 2013 the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee undertook a capability audit of national response capability for health disasters generally (such as mass casualty incidents). Health has also undertaken a review of the capability and capacity of laboratories across Australia to diagnose notifiable diseases and other agents, which was completed in 2016.

Tests and exercises

2.38 One branch (Health Emergency Management) of the Office of Health Protection regularly undertakes activities to develop skills relevant to communicable disease responses. An example of these activities is branch level discussions of responses to hypothetical scenarios. Health also undertakes tests of the National Incident Room, the most recent of which occurred in August 2016. There is no schedule for testing the National Incident Room.23

2.39 In 2016 Health implemented new contract arrangements for the National Medical Stockpile, which include provisions requiring the contractor (responsible for management of stockpile inventory) to demonstrate preparedness for a response through biennial drills, one of which must include physical movement of stock. The first of the required drills was undertaken in August 2016, consisting of a desktop exercise, which identified a need to update standard operating procedures in line with the new arrangements. Health completed the second drill, which involved deployment of supplies to a state health authority, in March 2017.

2.40 Health also conducts exercises with external stakeholders. For example, in 2014 Health led Exercise Panda. Key stakeholders at the Commonwealth, state and territory and local government levels were invited to discuss the strategic arrangements and decision making processes for managing a national response to an influenza pandemic. This exercise identified that stakeholder understanding of interactions within whole-of-government response arrangements could be improved, and that further opportunities to learn about the involvement of other entities in responses would be beneficial.

2.41 Health has developed a health emergency management exercise schedule for 2017. The basic schedule is broader than communicable disease emergencies. On 17 May 2017 Health provided the ANAO with reports for the two exercises conducted to date.24 Health’s schedule indicates that nine activities should have been completed by this date. The nature of the activities, the objectives and the relevance to communicable disease is not specified in either the schedule or the reports. The activities could be improved by clearly articulating this information.

2.42 Health does not have a formal process for capturing, monitoring and implementing the lessons it learns from the exercises it conducts, or from actual emergencies. For some exercises and incidents, Health has produced debrief reports outlining possible improvements, however responsibility for implementing these improvements or their current status is not documented. Health’s processes for capturing and implementing lessons from operational events are discussed further in Chapter 3.

3. Responding to communicable disease emergencies

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Health has effective arrangements in place to respond to a communicable disease emergency.

Conclusion

Health’s communicable disease plans do not clearly define in what circumstances and to what extent the department will become involved in a communicable disease emergency. Health responded effectively to the three communicable disease incidents examined. However, Health’s administrative processes and public communications could be improved. The department has made progress towards addressing approximately half of the lessons learnt through previous communicable disease emergency reviews and responses, but does not record or assess its progress towards implementation.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving Health’s communications with the public and recording progress towards implementation of recommendations and lessons.

Does Health clearly define the circumstances in which it will respond to a communicable disease emergency?

The Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance is the key governance document specific to communicable disease emergencies, but it does not clearly articulate the circumstances in which Health will respond to a communicable disease incident. The terminology used to describe communicable disease emergencies and the events that trigger a national response vary across different governance documents.

Defining communicable disease emergencies

3.1 The Department of Health’s (Health’s) Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance (CDPlan) does not define the term ‘emergency’. The Department has adopted the term ‘Communicable Disease Incident of National Significance’ (CDINS). A CDINS is a communicable disease incident that requires implementation of national policy, interventions and public messaging, or deployment of Commonwealth or inter-jurisdictional resources to assist affected jurisdictions.

3.2 In addition to CDINS, other terms are used in governance documentation to describe an event that may require coordination at a national level (see Table 3.1).25

Table 3.1: Terms used to describe an event requiring a nationally coordinated response

|

Term useda |

Governance document |

|

Public Health Emergency of International Concern |

International Health Regulations |

|

Public Health Event of National Significance to be reported to the national focal point |

National Health Security Agreement |

|

Domestic public health crisis |

Australian Government Crisis Management Framework |

|

Emergency of national consequence |

National Health Emergency Response Arrangements |

|

Communicable Disease Incident of National Significance (CDINS) |

Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance (CDPlan) |

Note a: Different definitions apply to the terms used in these governance documents.

Source: Relevant Australian Government health emergency documentation.

3.3 Although the term emergency is not defined in the CDPlan, Health used it in determining whether to declare a CDINS for the recent invasive meningococcal disease, serogroup W (meningococcal W)26 outbreak in Australia. During its assessment process, Health suggested that declaring a CDINS is the same as declaring an emergency, stating:

Noting that the CDPlan is an Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance, there is concern that declaring the increase in cases of [meningococcal W] a CDINS is akin to declaring a communicable disease emergency.

3.4 Conversely, Health later stated during a meeting of the meningococcal W assessment panel, that declaring a CDINS does not require an emergency to be declared. Similarly, Health’s process for assessing a communicable disease incident does not require the presence of an emergency and specifies that a request from a state or territory for assistance is sufficient to recommend a CDINS.27

3.5 The above example demonstrates that there is a lack of clarity surrounding the term emergency and its use in determining whether to recommend or declare a CDINS and the level of response Health will provide.

Triggers for declaring a communicable disease emergency

3.6 The events that trigger a need for national coordination of a communicable disease emergency response are the subject of a variety of definitions as outlined in Appendix 4.28

3.7 When a potential emergency is identified, Health may convene a rapid assessment panel to assess the status of an identified communicable disease incident.29 The panel includes representatives from Health, and the states and territories, and convenes to assess the characteristics of a communicable disease incident against the decision instrument shown at Figure 3.1. The panel then makes a recommendation to the Chief Medical Officer for consideration of whether the incident is a CDINS, potential CDINS, or not a CDINS.30

Figure 3.1: Decision instrument to support rapid assessment panel

Source: Department of Health, CDPlan, p. 47.

The principle of escalation

3.8 The CDPlan states that the Chief Medical Officer has authority to escalate the plan through the preparedness and response stages (see Table 3.2).

Table 3.2: Preparedness and response stages

|

Stage |

|

Actions |

|

Preparedness |

Business as usual. State and territory response arrangements are adequate. |

|

|

Response |

Standby |

Potential CDINS Health authorities and committees monitor the incident and prepare to escalate some or all of the response measures under the CDPlan. For example, preparing surveillance systems, communication material, planning investigations and research partnerships. |

|

Response |

Action |

Declared CDINS The incident requires implementation of national policy, interventions, public messaging or inter-jurisdictional resources. Health coordinates a national response. A CDINS warrants escalation of several response measures under the CDPlan. For example, escalate public health system measures and coordination mechanisms. |

|

Response |

Stand-down |

End of CDINS Return to preparedness stage. Response can be managed within by states and territories. |

Source: ANAO analysis of the CDPlan.

3.9 As discussed in Chapter 2, Health regularly responds to small scale communicable disease incidents. This may involve registering the incident, tracing people who may have had contact with an infected person, or passing information to relevant jurisdictional health authorities for follow up. Such incidents do not require national coordination.

3.10 The CDPlan states that:

Transitioning from routine communicable disease response to a national emergency response for a communicable disease incident is likely to represent an escalation in the scale or complexity of an existing response.

3.11 Therefore emergency response actions are based on the principle of escalation, rather than activation. Examples of Health’s escalation activities include enhanced surveillance and facilitating more frequent committee meetings.

3.12 Point A of the decision instrument shown at Figure 3.1 indicates that a request from a state or territory for assistance automatically results in a recommendation to declare a CDINS, triggering an escalation of Health’s activities. This has created an expectation that Health will take action at the request of a state or territory. In the case of the recent meningococcal W incident, Health decided that national intervention was not warranted despite a request from a state jurisdiction. It is, therefore, unclear when Health will move beyond the standby stage and take action to respond to an incident.

3.13 Given the range of terminology used, the various definitions that apply to those terms, and the expectations raised by the rapid assessment panel process, the ANAO suggests Health amend the CDPlan to:

- include a single clear definition of ‘emergency’;

- clarify the triggers for declaring a CDINS; and

- indicate that the assessment process will take into account the capacity of state and territory authorities to manage the incident within their own resources, including at Point A of the decision instrument shown at Figure 3.1.

Are Health’s response mechanisms effective?

Health has effectively coordinated a response for three recent incidents. However, Health’s processes are not always timely or well documented when transitioning through the response stages.

3.14 Health’s role in relation to three recent communicable disease incidents (for which a nationally coordinated response was considered) is described below.

Invasive meningococcal disease, serogroup W

3.15 The most recent national communicable disease incident that Health has responded to, and the first time the CDPlan has been used, is meningococcal W. Invasive meningococcal disease is a rare but serious communicable bacterial illness. Since 2014 there has been a national increase meningococcal W. A timeline of key actions taken since the incident was identified is shown at Table 3.3.

Table 3.3: Meningococcal W timeline

|

Date |

Action |

CDPlan Phase |

|

29 July 2015 |

During a CDNA meeting, a state government representative advises that the year-to-date number of meningococcal W cases is higher than previous years. |

Preparedness |

|

November 2015 |

Communicable Disease Network Australia begins monitoring meningococcal W in Australia and convenes a working group. |

|

|

19 September 2016 |

Health receives a state sponsored request for assistance to respond to increasing meningococcal W cases. |

|

|

20 September 2016 |

A Rapid Assessment Panel is formeda, and recommends that meningococcal W is a CDINS.b |

|

|

5 October 2016 |

The Office of Health Protection sends a Minute to the Chief Medical Officer, providing the outcomes of the RAP and recommending meningococcal W is a potential CDINS. |

|

|

6 October 2016 |

Chief Medical Officer formally declares meningococcal W a potential CDINS, with status to be reviewed in three months. |

Response - Standby |

|

12 October 2016 |

First Incident Management Team meeting held. |

|

|

17 October 2016 |

Draft Incident Action Plan is developed by the Incident Management Team. |

|

|

12 December 2016 |

Western Australian State Government announces vaccination program in response to a localised outbreak. |

|

|

14 December 2016 |

Incident Action Plan released. |

|

|

20 December 2016 |

Health publishes information about meningococcal W on its website. |

|

|

24 January 2017 |

Second Rapid Assessment Panel meeting held. |

|

|

2 February 2017 |

Draft outcomes from Rapid Assessment Panel meeting circulated to Health staff. |

|

|

6 February 2017 |

New South Wales State Government announces vaccination program. |

|

|

8 February 2017 |

Victorian State Government announces vaccination program. |

|

|

13 February 2017 |

Chief Medical Officer declares meningococcal W remains a potential CDINS. |

|

|

17 February 2017 |

The Office of Health Protection advises stakeholders of the outcomes of the Rapid Assessment Panel held on 24 January 2017. |

|

|

19 February 2017 |

Queensland State Government announces vaccination program. |

|

Note a: The panel was chaired by Health and included public health officials from states and territories.

Note b: A request for assistance leads to a recommendation to declare a CDINS (see Figure 3.1).

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.16 In the absence of a national approach to meningococcal W, four states have implemented separate vaccination programs.

Zika virus

3.17 Zika virus (Zika) is closely related to Dengue virus and is spread by the same mosquito species. While most people infected with Zika experience mild symptoms, it has been linked to serious health conditions. Between 2013 and 2015 there were large outbreaks in the Pacific Islands, and in 2015 it emerged in South America. Local transmission has not occurred in Australia. Table 3.4 shows a timeline of Zika related events.

Table 3.4: Zika timeline

|

Date |

Event |

CDPlan Phase |

|

November 2015 |

Health begins monitoring Zika virus after reports of the possible links between the virus and congenital and neurological complications. |

Preparedness |

|

19 January 2016 |

A Rapid Assessment Team is formed.a |

|

|

January 2016 |

The Office of Health Protection commences producing regular whole-of-government communications, epidemiological updates and information for the public, and Health professionals, on the Health website. |

Response - Standby |

|

1 February 2016 |

The World Health Organization declares Zika a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. |

|

|

3 February 2016 |

CDNA establish a working group, chaired by the Office of Health Protection, to develop nationally consistent public health advice on Zika. |

|

|

18 November 2016 |

The World Health Organization declares that Zika is no longer considered a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. |

|

|

12 January 2017 |

The Chief Medical Officer agrees to an Office of Health Protection recommendation to stand down the response to Zika virus. |

Response – Stand down |

|

20 January 2017 |

The Office of Health Protection emails other government agencies to advise of the stand down of the Zika virus response. |

|

|

3 March 2017 |

Health’s website still states the World Health Organization has declared a Public Health emergency of International Concern. |

|

Note a: A Rapid Assessment Team consists of staff from the Office of Health Protection. A Rapid Assessment Panel is a formal assessment panel including state and territory representatives, and other experts as required, chaired by Health.

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.18 Health was timely in providing information to the public via its website, and responded to 136 public enquires relating to the outbreak. Health monitored international developments, and used this information to undertake risk assessments of affected countries. During 2016 Health provided 57 situation reports to stakeholders across the Commonwealth to inform them of current developments. Updates were also provided to state and territory stakeholders via the health protection committees. Health could have better managed the transition to standing down the response, by providing timely public information that the response has been de-escalated.31

Ebola virus disease

3.19 Ebola virus disease (Ebola) is a severe illness, with an average fatality rate of 50 per cent in humans. The virus is transmitted to people from wild animals and spreads in the human population through human-to-human transmission. An outbreak of Ebola in early 2014 in West Africa triggered a world-wide health emergency. Table 3.5 shows a timeline of relevant Ebola related events.

Table 3.5: Ebola timeline

|

Date |

Action |

CDPlan Phase |

|

1 April 2014 |

Health commences regular reporting to department executives about Ebola. |

Preparedness |

|

28 April 2014 |

Advice for laboratories, GPs, clinician and the public is developed in consultation with CDNA and the Public Health Laboratory Network. |

|

|

22 July 2014 |

Health commences producing information for the public, and Health professionals, on the Health website. |

|

|

29 July 2014 |

Rapid Assessment Team meetings commence, and are held regularly until October 2014. |

|

|

8 August 2014 |

The World Health Organization declares Ebola is a Public Health Event of International Concern. |

Response - Standby |

|

2 September 2014 |

Health commences issuing weekly Ebola updates to the Prime Minister. |

|

|

9 August 2014 |

Additional border screening commences to identify and assess travellers from West Africa. |

|

|

17 September 2014 |

Formal inter-departmental committee meetings commence, co-chaired by Health and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. |

|

|

20 October 2014 |

Ebola Response Taskforce task force is created within Health. |

|

|

3 November 2015 |

Australia’s Ebola response arrangements are downscaled. |

Response – Stand down |

|

29 March 2016 |

The World Health Organization declares that Ebola is no longer a public health emergency of international concern. |

|

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.20 An internal review of Health’s Ebola response concluded that the formation of the Ebola response taskforce was appropriate and effective in its operations.

3.21 The end of Ebola transmission was declared in Sierra Leone in November 2015, and in Guinea and Liberia in June 2016. As at 4 April 2017, there is conflicting information available on Health’s website regarding the status of Ebola. Health’s ability to maintain consistent, accurate and timely communicable disease information is discussed further below.

Is Health’s public communication effective?

Health’s primary means of communicating with the public about communicable disease is through its website. The website contains out-of-date information, and does not always provide relevant information about communicable disease in a timely manner.

3.22 Under the CDPlan, Health is responsible for health-specific communications with the public at a national level. Health’s primary means of communicating communicable disease information to the public is via its website, which contains information such as:

- information for the general public about specific communicable diseases;

- technical information about communicable diseases targeted at health professionals; and

- communicable disease surveillance data.

3.23 Members of the public can also contact Health directly for information via telephone, email, or social media.32

3.24 Until January 2017, Health operated two websites to provide communicable disease information: www.health.gov.au; and www.healthemergency.gov.au.

3.25 The emergency website was out-of-date at the time it ceased functioning in mid-January 2017, referring to health issues that were no longer current while omitting information about current issues.33 The website continues to be referenced in Health’s CDPlan.

3.26 Health’s primary website (www.health.gov.au) includes a communicable disease section but does not distinguish between disease issues that are considered emergencies, and those which are discussed for general information. Adding such functionality would be of benefit in an emergency response.

3.27 The ANAO observed examples of incorrect website content. For example, in March 2017 Health’s website advised:

- travellers to Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia of the presence of widespread, intense transmission of Ebola—these countries were declared Ebola-free by the World Health Organization in mid-2016; and

- that the World Health Organization has declared Zika to be a public health emergency of international concern—this state of emergency was lifted in November 2016.

3.28 The ANAO also observed that Health does not always publish relevant information on its public website in a timely manner. For example, Health determined the need for coordinated public messaging on meningococcal W in early October 2016, after monitoring the disease since late 2015. Health did not publish information on the disease until late December 2016.

3.29 Health informed the ANAO that it is undertaking a department-wide transformation program to improve and rationalise its public-facing web presence. Health was not able to provide an indication of the extent of the program in relation to communicable disease or a timeframe for its implementation.

Recommendation No.2

3.30 Ensure Health’s public communication regarding communicable disease incidents is consistent, accurate and timely.

Department of Health’s response:

3.31 Agree noting that there is no indication that information is not consistent, accurate and up to date during an emergency response.

Does Health implement lessons learnt from previous emergencies?

Health has addressed or partially addressed approximately half of the relevant recommendations and lessons learnt from five recent reviews relating to communicable disease emergencies. Health has not developed a plan to monitor their implementation.

3.32 Table 3.6 lists five reports published since 2009 reviewing Health’s ability to respond to communicable disease emergencies and its implementation of relevant recommendations.

Table 3.6: Communicable disease emergency reviews

|

Review |

Number of recommendations relevant to Health |

Recommendations partially or fully addressed |

Recommendations not addressed |

|

Review of Australia’s Health Sector Response to Pandemic (H1N1), 2009 |

25 |

19 |

6 |

|

Diseases have no borders: Report on the inquiry into health issues across international borders, 2013a |

9 |

5 |

4 |

|

Exercise Panda – National Action Plan for Human Influenza Pandemic Exercise – Exercise Report, 2014b |

18 |

6 |

12 |

|

Review of the implementation of the Australian Government’s response to the West Africa Ebola outbreak, 2015 |

10 |

4 |

6 |

|

Review of the implementation of the Department’s response to the Ebola virus, 2015 |

6 |

1 |

5 |

|

Total |

68 |

35 |

33 |

Note a: Health has not formally responded to this report of the Standing Committee on Health and Ageing.

Note b: This report referred to ‘Themed Observations’, rather than recommendations.

Source: ANAO analysis of relevant reports.

3.33 Collectively, the five reviews made 68 recommendations relevant to Health’s management of communicable disease emergencies. The ANAO found evidence of some progress towards addressing 35 of those recommendations. However, there is no mechanism to assess whether recommendations will be accepted, or to record, track and evaluate implementation of recommendations. Registration, prioritisation and tracking of recommendations and lessons would assist Health to maintain oversight of the status of identified improvements and assess their effectiveness.

Recommendation No.3

3.34 Develop a process to record, prioritise and implement lessons and agreed recommendations from tests, exercises, communicable disease emergency responses and relevant reviews.

Department of Health’s response:

3.35 Agree.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Entity response

Appendix 2 Key communicable disease legislative and governance documents

|

Document name |

Health’s responsibilities |

|

International Health Regulations, 2005 |

|

|

National Health Security Act 2007 |

Part 2 objectives:

Mandatory requirements:

|

|

Biosecurity Act 2015a |

Allows:

|

|

Australian Government Crisis Management Framework, 2016 |

|

|

National Health Security Agreementd |

|

|

Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance (CDPlan), 2016 |

National Responsibilities

International Responsibilities

|

Note a: The Biosecurity Act is co-administered by Health and the Department of Agriculture.

Note b: Powers include: prescribe requirement in relation to individuals, and operators of certain aircraft or vessels entering or leaving Australia; and determine certain biosecurity measures to prevent a communicable disease entering, emerging, spreading or establishing in Australia.

Note c: For example, a person who has been exposed to or has symptoms of a listed disease.

Note d: The Agreement is between the Commonwealth of Australia and the states and territories.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Appendix 3 Diseases on the National Notifiable Disease List

Diseases on the National Notifiable Disease List:

- Anthrax

- Australian bat lyssavirus

- Barmah Forest virus

- Botulism

- Brucellosis

- Campylobacteriosis

- Chikungunya virus

- Chlamydia

- Cholera

- Creutzfeldt Jakob disease

- Cryptosporidiosis

- Dengue virus infection

- Diphtheria

- Donovanosis

- Flavivirus (unspecified)

- Gonococcal infection

- Haemolytic uraemic syndrome

- Haemophilus influenzae type b

- Hepatitis

- Hepatitis A

- Hepatitis B (newly acquired)

- Hepatitis B (unspecified)

- Hepatitis C (newly acquired)

- Hepatitis C (unspecified)

- Hepatitis D

- Hepatitis E

- Highly pathogenic avian influenza

- Human immunodeficiency virus

- Influenza (laboratory confirmed)

- Japanese encephalitis virus

- Legionellosis

- Leprosy

- Leptospirosis

- Listeriosis

- Lyssavirus

- Malaria

- Measles

- Meningococcal disease—invasive

- Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus

- Mumps

- Murray Valley encephalitis virus

- Ornithosis

- Pertussis

- Plague

- Pneumococcal disease—invasive

- Poliovirus

- Q fever

- Rabies

- Ross River virus

- Rotavirus

- Rubella

- Rubella—congenital

- Salmonellosis

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- Shiga Toxin producing E. Coli or Verotoxin producing E. Coli

- Shigellosis

- Smallpox

- Syphilis—congenital

- Syphilis <2 years duration

- Syphilis >2 years or unspecified duration

- Tetanus

- Tuberculosis

- Tularaemia

- Typhoid fever

- Variant Creutzfeldt Jakob disease

- Varicella zoster—Chickenpox

- Varicella zoster—Shingles

- Varicella zoster—unspecified

- Viral haemorrhagic fever

Source: National Health Security (National Notifiable Disease List) Instrument 2008.

Appendix 4 Triggers for Health’s involvement in national health emergencies

|

CDPlan |

National Health Emergency Response Arrangements |

National Health Security Agreement |

AHMPPI |

|

Notification by an affected jurisdiction that assistance in managing the health aspects of a communicable disease incident is required. The number and/or severity of cases is overwhelming the capacity of the affected health system including the public health sector. There is a need for consistent public messaging about the incident, and/or there is a need for national leadership and coordination. There is a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), or an international outbreak or incident, with implications for Australia. Other circumstances as deemed necessary by the AHPPC or the CMO. Recommendation from a Rapid Assessment Panel that a CDINS is occurring.a The CDI has complex political management implications above and beyond the routine jurisdictional clinical and operational management and response. |

A domestic or international event has the potential to overwhelm or exhaust a state and/or territory’s health assets and resources. A domestic or international event impacts or threatens to impact two or more states and/or territories and across jurisdictional borders. The scale or complexity of a domestic or international event warrants a nationally coordinated response. An international health emergency such as a border health event or overseas health emergency affecting Australian interests, Australian nationals or other designated persons is occurring. |

A public health event that is potentially of national significance or international concern, as defined in this Agreement, is nominated by a State or Territory or the Commonwealth and/or identified through national or international surveillance systems or networks. A mass casualty incident occurs overseas and one or more Australian citizens (or other persons) need to come to Australia for treatment. |

Notification from a jurisdiction that assistance in responding to severe seasonal influenza may be required, including an explanation of why the need cannot be met from state/territory resources. AHPPC will then determine whether this is an appropriate basis for escalation. Declaration of a pandemic by the WHO. Advice from a credible source that sustained community transmission of a novel virus with pandemic potential has occurred. |

Note a: Note that according to the CDPlan decision instrument, a request for assistance from a state or territory would automatically lead to a recommendation to declare a CDINS.

Source: Relevant Health governance documents.

Footnotes

1 C Castillo-Chavez, R Curtiss, P Daszak, S A Levin, O Patterson-Lomba, C Perrings, G Poste, S Towers, Beyond Ebola: lessons to mitigate future pandemics, The Lancet, Volume 3, July 2015.

2 C Castillo-Chavez, R Curtiss, P Daszak, S A Levin, O Patterson-Lomba, C Perrings, G Poste, S Towers, Beyond Ebola: lessons to mitigate future pandemics, The Lancet, Volume 3, July 2015.

3 This includes maintaining communication with the World Health Organization and health authorities in other countries.

4 In addition, Health has a responsibility to monitor international surveillance and to communicate its understanding of public health risks with its Commonwealth whole of government partners.

5 The term CDINS has been used by Health since the development of the Emergency Response Plan for Communicable Disease Incidents of National Significance in September 2016. Terminology is discussed further in Chapter 3.

6 Department of Health, Annual Report 2015–16, Health, Canberra, September 2016, p. 261.

7 AHPPC membership includes senior representatives from the Commonwealth, Australian states and territories, Department of Defence, the Attorney-General’s Department, Emergency Management Australia, and New Zealand.

8 Health provides secretariat services for the AHPPC and its standing committees.

9 Triggers for Health’s involvement in a health emergency are discussed further in Chapter 3.

10 Appendix 2 outlines Health’s responsibilities in relation to key legislative and governance documents.

11 The National Health Emergency Response Arrangements direct how the Australian health sector (incorporating state and territory health authorities and relevant Commonwealth agencies) would work cooperatively and collaboratively to contribute to the response to, and recovery from, emergencies of national consequence.

12 Work on the plan is continuing through Australian Health Minister’s Advisory Council.

13 The assessment allocated a risk rating of ‘very low’ to ‘high’ for each identified risk.

14 The Australian Sentinel Practice Research Network is a national network of around 50 general practitioners who collect and report data on selected conditions seen in general practice.

15 The National Notifiable Disease List is shown at Appendix 3.

16 The reports are available from http://www.health.gov.au/cdnareport.

17 Health also maintains a roster of Medical Officers who are able to provide on call support.

18 Participation in induction training is the only mandatory activity NIR staff must complete.

19 The stockpile was last deployed in response to a public health emergency during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.

20 The incident management system was procured in 2012 to replace an ad-hoc system of paper registers and custom-developed applications that were not considered suitable for an all-hazards approach and required specialised experience to maintain. In November 2016 Health purchased a 3 month subscription for the incident management system at a cost of $25 500 (excluding training and configuration costs).

21 The ANAO examined 12 incidents as this is the average number Health receives in a month. The incidents are all those registered by Health between 22 December 2016 and 25 January 2017. Each incident relates to a disease listed on the National Notifiable Disease List and fulfils the criteria of a Public Health Event of National Significance under the National Health Security Act 2007.

22 Watch Officers are required to complete a daily debrief of their shift. Of the 20 debriefs recorded between 20 December 2016 and 20 January 2017, 12 (60 per cent) summarised the shift using the word ‘quiet’, and two were summarised as ‘steady’ or ‘normal’. Summaries were not completed for six of the 20 debriefs.

23 Health does conduct monthly maintenance checks of the National Incident Room, which involve a physical inspection of the room and key equipment items.

24 The activities were conducted on 22 February and 31 March 2017.

25 Terminology used in governance documentation does not exclusively refer to communicable disease incidents, and encompasses other health emergencies such as natural disasters.

26 Six serogroups of invasive meningococcal disease (A, B, C, W, X and Y) account for most cases of the disease in Australia.

27 See Figure 3.1.

28 For example, a trigger in the CDPlan is a ‘notification by an affected jurisdiction that assistance …. is required’. The Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza states that notification from a jurisdiction regarding assistance with severe seasonal influenza must include ‘an explanation of why the need cannot be met from state/territory resources’.

29 A rapid assessment panel may be convened at the request of any member of AHPPC or an AHPPC standing committee.

30 According to the CDPlan, the Chief Medical Officer has sole delegation to declare a CDINS.

31 Health’s public communications are discussed below.

32 Health advised the ANAO that during 2016 it received 297 enquiries via telephone, 37 via email, and three via Twitter.

33 For example, in November 2016, the website’s front page discussed the summer heatwave of 2013–14, which was the most recent emergency mentioned. The website did not mention the Zika outbreak. At that time, Zika was considered a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization, for which Health had an active response. Health provided Zika information on its non-emergency website.