Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Department of Defence’s Management of General Stores Inventory

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- As at 30 June 2022, Defence was managing general stores inventories (GSI) of more than 70 million items across 547 geographically dispersed locations.

- Efficient and economical management of GSI contributes to: achieving Defence’s purpose; and compliance with the accountable authority’s Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 responsibilities.

- This audit provides independent assurance to Parliament of the efficiency and economy of Defence’s management of GSI.

Key facts

- GSI includes items such as ration packs, clothing, screws, washers, light globes, toiletries, as well as replacement parts for Specialist Military Equipment (SME).

- Defence holds ‘operating stocks’ of GSI to maintain capability, and ‘reserve stocks’ over and above operating levels.

- Defence policy provides for a ‘balanced inventory’ that avoids both understocking and overstocking.

What did we find?

- Defence cannot demonstrate that it is achieving efficiency and economy in its management of GSI.

- The GSI management framework partly addresses efficient management and does not address economical management.

- The framework is not operating as intended to achieve the proper use and management of public resources.

- Defence cannot demonstrate it has fully implemented its framework requirements for a ‘balanced inventory’ that avoids both understocking and overstocking.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made four recommendations to improve Defence’s: guidance for holding GSI overstocks; assessment of risk relating to known non-compliance with the inventory management framework; estimates of inventory management costs; and senior management response to known issues of inefficiency and overstocking of GSI.

- Defence agreed to the recommendations.

$2.6bn

Value of GSI reported in Defence’s financial statements at 30 June 2022.

$1.7bn

Value of GSI that could not be identified against a need or activity at 30 June 2022.

65–79%

Percentage of GSI identified by Defence systems as overstock between 2015–16 and 2021–22.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Defence defines inventory management as the ‘phase of military logistics which includes managing, cataloguing, requirements determinations, procurement, distribution, overhaul and disposal’ of inventory.

2. As at 30 June 2022, Defence reported a balance of $7.9 billion in inventories comprised of explosive ordnance ($5.3 billion), general stores inventories ($2.6 billion) and fuel ($61.6 million).1 Defence holds both ‘operating stocks’ to maintain capability, and ‘reserve stocks’ over and above operating levels.2

3. This audit is focused on Defence’s management of general stores inventory (GSI).3 Defence’s Electronic Supply Chain Manual defines GSI as items:

consumed in the course of Defence operations and used in the delivery and support of deployable military capability. GSI includes expendable and consumable items (Stock Type X) such as ration packs, clothing, sleeping bags, webbing, wet weather equipment, screws, washers, light globes, toiletries, as well as accountable inventory (Stock Type A) which incorporate those high value platform-specific and general replacement parts for Specialist Military Equipment (SME) assets which are not repairable.

4. Defence’s GSI holdings comprise more than 70 million items of various stocks that are managed across 547 geographically dispersed locations. Defence records indicate that as at 17 November 2022, the majority of GSI (99.87 per cent) was being managed by Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG).

5. Defence’s Accountable Authority Instruction 8: Managing Defence Property (AAI 8) sets out a requirement to ensure that ‘Defence property is used in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner.’4 Defence property includes but is not limited to equipment, furniture, office supplies, clothing, uniforms, IT and telecommunications assets and military equipment. AAI 8 instructs ‘everyone’ of their responsibility to ‘record, store, distribute, cost, disclose, dispose, track, transfer and stocktake property in accordance with policies endorsed by the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) or the CFO [Chief Finance Officer]’. AAI 8 also instructs Defence Group Heads and military Service Chiefs that they ‘are responsible and accountable for all Defence property in your Group’s custody’.

6. By issuing AAI 8, the Secretary of Defence acts in accordance with the duty in section 15 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) to govern the entity in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources.5

Rationale for undertaking the audit

7. As at 30 June 2022, Defence was managing general stores inventories (GSI) comprising more than 70 million items of various stocks valued at $2.6 billion across 547 geographically dispersed locations. The efficient and economical management of the level of inventories (both operating stocks and reserve stocks) contributes to: the achievement of Defence’s purpose; and compliance with the accountable authority’s responsibilities for the proper use and management of public resources for which the accountable authority is responsible.

8. This audit provides independent assurance to the Parliament of the efficiency and economy of Defence’s management of GSI.

9. The JCPAA identified the potential audit topic as a priority of the Parliament for 2020–21.

Audit objective and criteria

10. The audit objective was to examine the efficiency and economy of Defence’s management of its general stores inventory. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high level audit criteria were adopted.

- Has Defence established an authorising and administrative framework for the efficient and economical management of general stores inventory?

- Can Defence demonstrate implementation of its framework for the efficient and economical management of general stores inventory?

Conclusion

11. Defence cannot demonstrate that it is achieving efficiency and economy in its management of general stores inventory.

12. Defence has established an authorising and administrative framework for the management of its general stores inventory which partly addresses efficient management and does not address economical management. Defence has been partly effective in maintaining its framework and has allowed it to degrade over time, pending implementation of new systems and supporting policies. The framework is not operating as intended to achieve the proper use and management of public resources.

13. Defence is not able to demonstrate that it has fully implemented its framework requirements regarding cost-effective and efficient inventory management, and a ‘balanced inventory’ that avoids both understocking and overstocking. Defence was also unable to demonstrate, until late in this audit, an active focus or response by Defence senior leaders on known issues contributing to inefficiency and overstocking in the management of general stores inventory.

Supporting findings

The framework for managing inventory

Authorising and planning framework

14. Defence has established but not fully documented a framework for the management of its inventory. The framework establishes both authorising and planning arrangements for the management of general stores inventory (GSI). The framework sets out roles and responsibilities within Defence and includes relevant policies and procedures to be followed. However, the authorising and planning frameworks for inventory stock holdings are not fully documented. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.65)

15. While the framework includes statements about the importance of cost-effective and efficient resource use, it does not directly address economical management of Defence inventory. (See paragraph 2.7)

16. Defence has allowed the framework to degrade over time, and non-compliant practices to arise, while awaiting the implementation of new systems and supporting policies. Defence could not provide the ANAO with evidence that the senior responsible officers — for entity-wide logistics policies and procedures and for Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) policies and procedures — have assessed the risks associated with the current approach or approved it. (See paragraphs 2.66 to 2.83)

17. The framework is not operating as intended to achieve the proper use and management of public resources and elements of the framework established in 2020 to provide visibility of, and authority for, justifiable overstocking have not been implemented. (See paragraphs 2.66 to 2.72)

Systems

18. Defence has established systems to support implementation of its authorising and planning framework for GSI. These include the Military Integrated Logistics Information System (MILIS). (See paragraphs 2.84 to 2.89)

19. A weakness of Defence’s systems is that they do not provide visibility of the holding and administrative costs associated with its GSI. Defence’s inventory management system includes ‘notional’ holding and administrative costs established in 1999, and the government’s 2008 Audit of the Defence Budget (the Pappas Review) found that Defence had materially underestimated those costs. In effect, not all relevant inventory management costs are well understood by Defence. This affects the ability of accountable logistics managers to make efficient and economical inventory procurement decisions and Defence is not well placed to demonstrate the efficiency and economy of its inventory management arrangements. (See paragraphs 2.90 to 2.101)

Operational guidance and training arrangements

20. Defence has established operational guidance and training arrangements to support the implementation of the authorising and administrative framework. Defence’s guidance and training is largely focussed on the use of MILIS by its Designated Logistics Managers (DLMs), rather than the broader range of skills and experience required by the Defence Logistics Policy Manual, and does not focus explicitly on the efficient and economical management of GSI. (See paragraphs 2.102 to 2.115)

21. Defence has stated that its training arrangements are intended to support the professionalisation of logistics personnel. While training to access MILIS is mandated for DLMs and managed centrally, other relevant training is not. The completion of other training requirements is managed at a local level and Defence is not well placed to provide internal assurance that DLMs have the skills and experience required by the Defence Logistics Policy Manual. (See paragraphs 2.111 to 2.119)

Framework implementation

Governance, monitoring, reporting and evaluation arrangements

22. Defence has established governance, monitoring, reporting and evaluation arrangements for its GSI. These arrangements generate relevant management information for Defence’s operational managers and senior leaders with oversight responsibilities, including in respect to overstocks of GSI. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.25)

23. The information available from these arrangements indicates that Defence is only partly effective in its implementation of the documented framework for cost-effective and efficient inventory management, which includes the goal of a ‘balanced inventory’ that avoids both understocking and overstocking. Since their introduction in 2015–16, annual Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) inventory health checks have repeatedly drawn attention to an inadequate focus on efficiency and resultant overstocking of Defence warehouses. They have further highlighted that overstocking is indicative of unnecessary overspending. (See paragraphs 3.26 to 3.53)

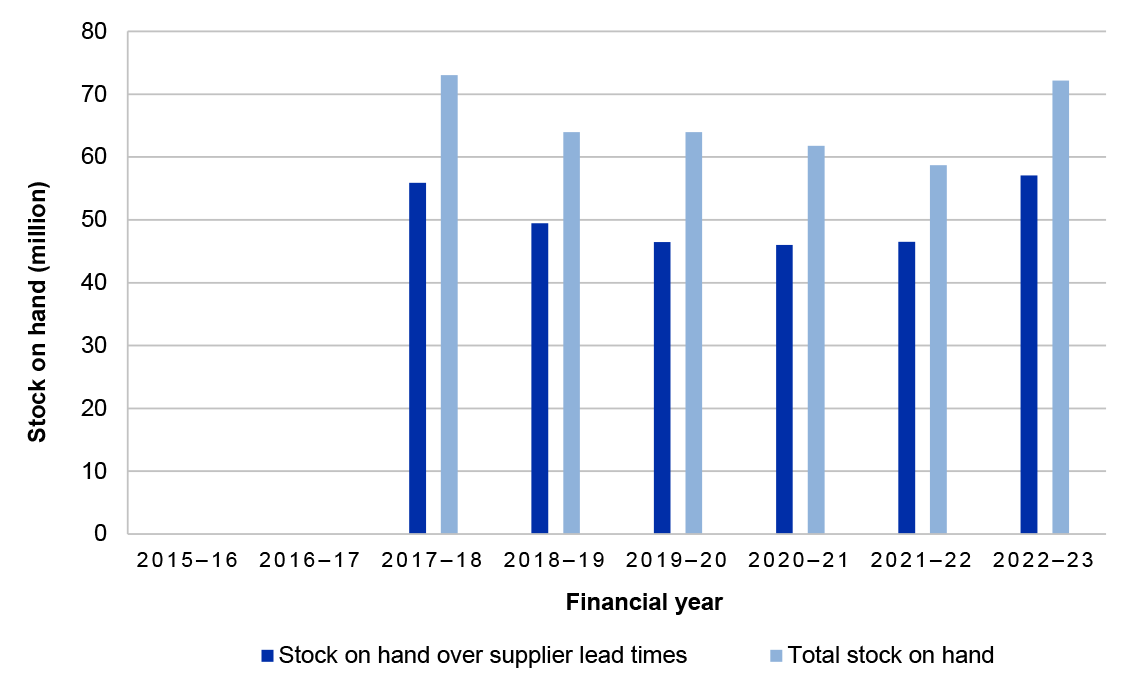

Demonstrating implementation of the framework

24. Data from Defence systems indicates that on every measure examined by the ANAO, Defence’s GSI is not ‘balanced’. As of 7 February 2023, 79 per cent of general stores inventory warehouse stock on hand represented system-calculated overstock. Historically, this figure has been between 65 and 79 per cent. (See paragraphs 3.54 to 3.75)

25. The high levels of system-calculated GSI overstocks indicate that CASG’s System Program Offices (SPOs) — which are responsible for day-to-day inventory management — continue to not calculate and/or model, or enter in Defence inventory management systems, operational and reserve stock quantities. (See paragraph 3.76)

26. Defence’s performance against the examined measures, and non-compliance with the documented inventory framework, indicate that Defence is not able to demonstrate that it has fully implemented framework requirements regarding cost-effective and efficient inventory management, and a ‘balanced inventory’. (See paragraph 3.76)

27. CASG’s annual inventory health check findings on the reasons for overstocking and inefficiency in the management of GSI have been reported to operational management and senior leaders since the health checks were introduced in 2015–16. However, there was no indication until late in this audit of an active focus by Defence senior leaders on these known issues, nor an active management response (see paragraphs 3.77 to 3.82).

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.64

The Department of Defence clarify the status, and review the implementation, of the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group’s Materiel Planning and Management Policy and associated procedures, to ensure that there is a documented rationale for holding general stores inventory identified as overstock.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.82

The Department of Defence assess:

- the risks associated with the current approach of allowing the existing framework of logistics policies and procedures to degrade over time while awaiting the implementation of the logistics management component of the Enterprise Resource Planning system; and

- whether the current approach and related non-compliance can be authorised or needs to be re-aligned with documented requirements.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.100

The Department of Defence review holding and carrying cost values established in its systems supporting inventory management, to ensure that they reflect a contemporary evidence-based estimate of these inventory management costs.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.81

The Department of Defence develop a senior management response to the known issues contributing to inefficiency and overstocking in the management of general stores inventory, including a review of:

- inventory management training and compliance arrangements across all Domains and System Program Offices, to ensure that operational and reserve stock requirements are calculated and/or modelled and that these values are recorded in Defence’s inventory management systems; and

- procurement against stock codes which are inactive, including those with no usage history, to determine whether these represent unauthorised overstocking.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

28. Defence’s summary response is provided below. Defence’s full response is included at Appendix 1.

Defence acknowledges the ANAO’s assessment that Defence cannot fully demonstrate it has implemented a framework that achieves ‘balanced inventory’ (i.e. that avoids both understocking and overstocking).

Defence is committed to strengthening processes and controls for the management of general stores inventory and will consider key strategic inputs to Defence preparedness and planning guidance to inform remediation priorities for consistency and assurance. The Defence Enterprise Resource Planning system currently being implemented will deliver enhanced capability to track labour, storage and distribution costs to a greater level of granularity.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Defence defines inventory management as the ‘phase of military logistics which includes managing, cataloguing, requirements determinations, procurement, distribution, overhaul and disposal’ of inventory. The Defence Logistics Policy Manual states that Defence holds two broad categories of inventory.6

- Operating stocks — defined as ‘those stocks required to support the [military] Service Chiefs in meeting established raise, train and sustain targets, including exercises and current operations’. Defence holds operating stocks to maintain Defence capability.

- Reserve stocks — held where ‘operating stocks are insufficient to initiate or sustain approved contingency activity’. Reserve stocks are those stocks over and above operating levels that Defence holds to safeguard its inventory holdings against possible future events such as emergencies, short-notice operations, delays in production and transit, or other unforeseen fluctuations in supply or demand.

1.2 As at 30 June 2022, Defence reported a balance of $7.9 billion in inventories comprised of explosive ordnance ($5.3 billion), general stores inventories ($2.6 billion) and fuel ($61.6 million).7 This audit is focused on Defence’s management of general stores inventory (GSI).8 Defence’s Electronic Supply Chain Manual defines GSI as items:

consumed in the course of Defence operations and used in the delivery and support of deployable military capability. GSI includes expendable and consumable items (Stock Type X) such as ration packs, clothing, sleeping bags, webbing, wet weather equipment, screws, washers, light globes, toiletries, as well as accountable inventory (Stock Type A) which incorporate those high value platform-specific and general replacement parts for Specialist Military Equipment (SME) assets which are not repairable.

1.3 Within Defence systems, GSI is identified by two Stock Type codes — ‘A’ for accountable inventory, and ‘X’ for expendable inventory. Table 1.1 below sets out the definitions of the two Stock Type codes. It also sets out the amount of warehouse stock on hand, as recorded against these codes.

Table 1.1: How general stores inventory (GSI) items are identified by Defence

|

Stock Type code |

Description |

Count of stock codesa |

Warehouse stock on handa |

Definition |

|

A |

Accountable Inventory |

77,887 |

3,972,820 |

Items which by reason of special requirements such as health, safety, security or operational criticality require a higher measure of control; or by reason of their value and attractiveness are deemed to present a high risk of misappropriation for the purpose of private use; or the loss or mismanagement would be likely to create significant media or public interest or be considered a breach of State or Commonwealth law. |

|

X |

Expendable Inventory |

553,936 |

68,210,328 |

Items of inventory that are consumed but not accountable (for example, uniforms). |

|

Total |

– |

631,823 |

72,183,148 |

– |

Note a: Stock codes are types of items. This column sets out the numbers of types of items as at 7 February 2023.

Source: Defence documentation.

1.4 Defence’s GSI holdings comprise more than 70 million items of various stocks that are managed across 547 geographically dispersed locations. As shown in Table 1.2 below, since 30 June 2020, the number of locations, stock codes and total stock on hand has decreased and the reported financial value of GSI holdings has increased.

Table 1.2: Characteristics of Defence’s GSI holdings — as at 30 June 2020, 2021 and 2022

|

Date |

Number of locations |

Number of stock codes |

Total stock on hand |

Reported financial statement value ($’000) |

|

30 June 2020 |

597 |

322,191 |

75,321,058 |

2,335,148 |

|

30 June 2021 |

564 |

306,219 |

73,355,051 |

2,469,837 |

|

30 June 2022 |

547 |

307,480 |

70,849,141 |

2,566,153 |

Source: Defence documentation.

1.5 Defence records indicate that as at 17 November 2022, the majority of GSI (99.87 per cent) was being managed by the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG). The breakdown of which parts of Defence were managing GSI as at 17 November 2022 is shown in Table 1.3 below.

Table 1.3: Management of GSI within Defence — as at 17 November 2022

|

Group |

Number of stock codes |

Total stock on hand |

Percentage of total stock on hand (%) |

Reason for managing stock |

|

CASG |

319,061 |

73,799,622 |

99.87 |

Core business |

|

Army |

496 |

42,178 |

0.06 |

Specialist items for Special Forces |

|

Joint Capabilities Group |

424 |

53,219 |

0.07 |

Fuel, oils and lubricants for which the group is the stock item owner and some specialist items for explosive ordnance services |

|

Air Force |

2 |

17 |

0.00 |

Old training parts for obsolete aircraft engines |

|

Not Assigned |

4 |

100 |

0.00 |

Codification error under remediation |

|

Total |

319,987 |

73,895,136 |

100 |

– |

Source: Defence documentation.

Management of Defence property

1.6 Defence’s Accountable Authority Instruction 8: Managing Defence Property (AAI 8) sets out a requirement to ensure that ‘Defence property is used in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner.’9 Defence property is defined in AAI 8 as ‘anything other than money, owned or held by Defence.’ Defence property includes but is not limited to equipment, furniture, office supplies, clothing, uniforms, IT and telecommunications assets and military equipment. AAI 8 instructs ‘everyone’ of their responsibility to ‘record, store, distribute, cost, disclose, dispose, track, transfer and stocktake property in accordance with policies endorsed by the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) or the CFO [Chief Finance Officer]’. AAI 8 also instructs Defence Group Heads and military Service Chiefs that they ‘are responsible and accountable for all Defence property in your Group’s custody’.

1.7 By issuing AAI 8, the Secretary of Defence acts in accordance with the duty in section 15 (see Box 1) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).

|

Box 1: Duties of accountable authorities |

|

Section 15 of the PGPA Act sets out the duties of an accountable authority in governing a Commonwealth entity.

|

Note a: ‘Proper’ is defined in section 8 of the PGPA Act, in relation to the use or management of public resources, as ‘efficient, effective, economical and ethical’ use. The term ‘use’ refers to the spending of relevant money, the commitment of appropriations, and the application of public resources generally to achieve a public purpose. The term ‘management’ is broad and encompasses the decisions, systems and controls around the custody and use of, and accountability for, public resources.

Source: PGPA Act and the associated explanatory memorandum.

Administrative arrangements

1.8 Defence’s Administrative Policy Instruction, dated July 2022, identifies the Chief of Joint Capabilities (military three-star officer) as the accountable officer for joint logistics in Defence, including the enterprise-wide policies and procedures that apply to the management of Defence inventory.10 These policies and procedures include the Defence Logistics Manual (DEFLOGMAN) series.11

1.9 Internal agreements between Joint Capabilities Group (JCG) and CASG establish the warehousing, distribution and stocktaking services provided by JCG for inventory managed by CASG.12 The agreements set out what is supplied at no cost to CASG and what is supplied on a ‘user pays’ basis. The current agreements were signed in January 2013 and have not been updated since then.

1.10 Defence’s Administrative Policy Instruction identifies the Deputy Secretary CASG (a civilian Senior Executive Service Band 3 official) as the accountable officer for the provision of ‘integrated product support’ to Defence’s Capability Managers.13 Capability Managers are responsible for developing logistical support plans and sustainment agreements with CASG, and setting the level of investment in preparedness, including reserve stock. Support for capability managers is administered through internal agreements between the Capability Managers and CASG (discussed further in paragraph 2.18). Box 2 below describes the key CASG management positions that are responsible for the management of GSI.

|

Box 2: Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) roles and responsibilities for the management of general stores inventory (GSI) |

|

Division Heads CASG Division Headsa are responsible for:

Chair of the CASG Materiel Logistics Management Group The Chair of the CASG Materiel Logistics Management Groupb is responsible for developing and promulgating process and procedural level guidance to support Domain Heads (Division Heads) to achieve compliance with CASG’s Materiel Planning and Management policy. System Program Offices (SPOs) SPOs are responsible for forecasting, determining order quantities, and the procurement of Defence’s GSI.c In October 2022, Defence advised the ANAO that there are 64 SPOs, all of which manage GSI items. SPO Directors are accountable for the collection of Designated Logistics Manager responsibilities associated with the items their SPO manages. Designated Logistics Managers (DLM) The Designated Logistics Manager is the single point of accountability for the through-life management of the allocated item/s. DLMs are designated by, and accountable to, the Product Manager or SPO Director within CASG. DLM roles and responsibilities are summarised in paragraphs 2.9 to 2.13. |

Note a: Defence policy refers to Domain Heads, which is not a contemporary position. The current equivalent is Division Head. These are military two-star officers or civilian Senior Executive Service (SES) Band 2 positions.

Note b: The Chair of the Materiel Logistics Management Group is an Executive Director (Executive Level 2.1) within CASG. The Materiel Logistics Management Group is discussed in Table 3.1.

Note c: Defence advice to the ANAO, November 2022. Also see Table 1.3.

Source: Defence documentation.

Reviews of Defence’s management of inventory

1.11 Auditor-General Report No. 5 1997–98 Performance Management of Defence Inventory14 observed that the 1996–97 Defence Efficiency Review (DER, known as the McIntosh review) had highlighted that there were significant opportunities to improve the management of Defence inventory. The DER logistic review team had concluded that levels of operating stock were far too high, reflecting a ‘just in case’ culture. The ANAO considered that an important element in the implementation of Defence’s strategic logistics planning would be an effective performance management strategy and framework that would enable both its effectiveness and efficiency to be measured and managed. The absence of such a framework was considered to have contributed to many of the inefficiencies in inventory management identified by the DER. The ANAO also discussed the importance of Defence understanding and having regard to the costs associated with managing its inventory, that is the economy of its inventory management.

Making cost-effective use of Defence supply-related resources requires a full understanding of the requirement for items based upon capability, preparedness and safety considerations. These factors should then, particularly in peace time, be traded-off against the costs involved in various procurement, storage and distribution strategies.

However, there has been little focus within Defence on developing a management approach for inventory from this perspective. There are few incentives within the current resource and performance management frameworks for managers to consider wider supply chain costs. For example, inventory managers have little knowledge of the additional costs associated with procurement, such as freight and storage costs.15

1.12 Subsequent government commissioned reviews16 of Defence’s management of inventory also identified issues and areas for improvement in the management of GSI, including:

- unnecessary costs associated with storage, distribution and management of excess inventory;

- that storage and transaction costs were not adequately considered in inventory purchasing decisions; and

- opportunities for Defence to make one-off and ongoing savings by reducing its excess stocks of GSI.

1.13 The Logistics Companion Review to the 2009 Defence White Paper discussed the relationship between unnecessary costs associated with excess inventory and inadequate consideration of storage and transaction costs in inventory purchasing decisions.

There are numerous examples of poor decision making by users of the logistic system, or clear abuse of the service offered, because the offenders do not incur any financial penalty as a consequence of their choices. For example … Logistic Managers have no visibility of the additional warehousing costs incurred as a result of their decision to purchase large quantities of stock. Indeed they would be oblivious to the fact that the ‘total cost’ of their acquisition may be considerably more, despite them having negotiated a bargain unit purchase price. Defence has no cost attribution model, or agreed means of transferring logistics costs to the user. As improved cost visibility and transparency is likely to influence improved behaviours among users, such an approach is seen as a key generator of efficiencies and is a high priority target in the package of inventory reform being considered by Defence. It may be that a cost attribution model will achieve the intent by making it transparent to Capability Managers what the cost drivers [are] under their responsibility.

1.14 Defence has undertaken a number of initiatives to address identified issues in its logistics management. Key initiatives are discussed in Appendix 3 of this audit report. Most recently, in January 2021, Defence undertook a health check of ‘Supply Chain Assurance’ and found that:

A range of controls and assurance activities are in place across the receipting, returning and disposal phases, however limited to no second and third line assurance activities exist in relation to the earlier planning, sourcing, and manufacturing phases. Defence is currently unable to provide confidence or certainty that supply chain governance and risk management processes are effective in mitigating risks in these early phases.

…

Defence currently has work underway which will introduce controls aimed at better managing and mitigating supply chain risks, but would benefit from a holistic supply chain assurance and control effectiveness audit once these controls have been implemented.

1.15 The health check noted that the planned controls were due to be implemented during 2022, as part of the Supply Chain Risk Management Project and the Supply Network Analysis Program.17

- In respect to the Supply Chain Risk Management Project, Defence advised the ANAO in September 2022 that it was on track to finalise development of ‘risk lenses’ in the 2022 calendar year and transition to business-as-usual support for ongoing support and maintenance at the end of the 2022–23 financial year. Defence further advised in May 2023 that the Supply Chain Risk Management solution had not yet been operationalised and was being prioritised as part of Inventory Analytics Reporting activities (see paragraph 3.15 of this audit report).

- In respect to the Supply Network Analysis Program, Defence advised the ANAO in September 2022 that it was available to all Defence Groups and Services on a user pays basis and was reported on regularly to executive committees.

1.16 The ANAO noted in the Interim Report on Key Financial Controls of Major Entities for 2021–22 that the existence and completeness of Defence’s inventory balances was a key area of financial risk due to the ‘variety and number of inventory items which are managed differently across a large number of geographically dispersed locations and through a number of IT systems.’18 The report outlined that the ANAO had tested the operating effectiveness of the controls implemented to confirm the existence and completeness of inventory. The ANAO made no audit findings on this topic.19

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.17 As at 30 June 2022, Defence was managing general stores inventories (GSI) comprising more than 70 million items of various stocks valued at $2.6 billion across 547 geographically dispersed locations. The efficient and economical management of the level of inventories (both operating stocks and reserve stocks) contributes to: the achievement of Defence’s purpose; and compliance with the accountable authority’s responsibilities for the proper use and management of public resources for which the accountable authority is responsible.

1.18 This audit provides independent assurance to the Parliament of the efficiency and economy of Defence’s management of GSI.

1.19 The JCPAA identified this potential audit topic as a priority of the Parliament.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.20 The audit objective was to examine the efficiency and economy of Defence’s management of its general stores inventory. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high level audit criteria were adopted.

- Has Defence established an authorising and administrative framework for the efficient and economical management of general stores inventory?

- Can Defence demonstrate implementation of its framework for the efficient and economical management of general stores inventory?

1.21 The audit focused on Defence’s management of GSI for which CASG is responsible, comprising 99.87 per cent of total stock on hand for GSI. The ANAO did not conduct audit procedures over the remaining balance. Accordingly, the ANAO’s review of policies and procedures focused on the DEFLOGMAN series and the governance of CASG’s management of GSI.

1.22 The Defence IT system in scope for the audit was the Military Integrated Logistics Information System (MILIS). MILIS is an amalgamation of applications (with the core application being Ellipse®), interfaces, and modules that facilitate the management of Defence inventory. The ANAO did not examine the financial management of GSI in other systems, such as the Computer System for Armaments used for explosive ordnance, and the Pharmaceutical Integrated Logistics System used for controlled drugs.

1.23 The audit scope did not include:

- physical stocktaking or an examination of the contracts Defence has in place for management of inventory at warehouses20;

- end use of GSI including the management and use of inventory at the military unit level and in operations, the receipting of goods, returning inventory, and the disposal of inventory; and

- the technical or environmental aspects of GSI storage, including work health and safety issues relating to handling and incident reporting.

Audit methodology

1.24 The ANAO reviewed Defence’s:

- strategies and policies;

- operational guidance and manuals;

- training arrangements;

- supporting systems, including planning arrangements and procedures;

- governance and assurance arrangements, including monitoring, internal and external reporting, and reviews on the management of GSI; and

- inventory data for GSI forming inputs to reporting arrangements.

1.25 The ANAO also held discussions with relevant Defence personnel.

1.26 The audit was open to contributions from the public. One submission was received and reviewed.

1.27 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $431,101.

1.28 The team members for this audit were James Woodward, Natalie Whiteley, Kim Murray, Michael Brown, Jude Lynch, Sally Ramsey and Amy Willmott.

2. Framework for managing inventory

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Defence (Defence) has established an authorising and administrative framework for the efficient and economical management of its general stores inventory (GSI).

Conclusion

Defence has established an authorising and administrative framework for the management of its general stores inventory which partly addresses efficient management, and does not address economical management. Defence has been partly effective in maintaining its framework and has allowed it to degrade over time, pending implementation of new systems and supporting policies. The framework is not operating as intended to achieve the proper use and management of public resources.

Recommendations

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at improving Defence’s: guidance for holding GSI overstocks; assessment of risk relating to known non-compliance with its inventory management framework; and estimates of inventory management costs.

The ANAO also identified two opportunities for improvement relating to: the adjustment of policy and/or administrative arrangements to prevent avoidable non-compliance; and providing internal assurance that people undertaking a Designated Logistics Manager function have the skills and experience to undertake their role to the appropriate standard.

2.1 A fit for purpose authorising and administrative framework would enable Defence to provide internal assurance that GSI is managed in an efficient and economical manner and that obligations relating to the proper use and management of resources are being met.

2.2 A fit for purpose framework would include arrangements focused on the proper use and management of resources, including the achievement of efficiency and economy. Specific arrangements would include:

- up-to-date policies and processes to be followed to achieve proper use and management of resources;

- clear roles and responsibilities regarding the implementation of requirements;

- systems to support the implementation of requirements; and

- operational guidance and training to support officials in undertaking their responsibilities to implement requirements and achieve the proper use and management of resources.

Has Defence established an authorising and planning framework for the efficient and economical management of general stores inventory?

Defence has established but not fully documented a framework for the management of its inventory. The framework establishes both authorising and planning arrangements for the management of general stores inventory (GSI). The framework sets out roles and responsibilities within Defence and includes relevant policies and procedures to be followed. However, the authorising and planning frameworks for inventory stock holdings are not fully documented.

While the framework includes statements about the importance of cost-effective and efficient resource use, it does not directly address economical management of Defence inventory.

Defence has allowed the framework to degrade over time, and non-compliant practices to arise, while awaiting the implementation of new systems and supporting policies. Defence could not provide the ANAO with evidence that the senior responsible officers — for entity-wide logistics policies and procedures and for Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) policies and procedures — have assessed the risks associated with the current approach or approved it.

The framework is not operating as intended to achieve the proper use and management of public resources and elements of the framework established in 2020 to provide visibility of, and authority for, justifiable overstocking have not been implemented.

Policies and procedures

2.3 Defence has documented policies and procedures for the management of its inventory. The primary policy documents for Defence’s management of its GSI are the:

2.4 Defence’s inventory management policies are supported by documented procedures — primarily those in the Electronic Supply Chain Manual23 and CASG procedure documents that support the CASG Materiel Planning and Management policy. Defence’s inventory management policies and procedures are presented in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Defence’s policies and procedures for the management of GSI

Source: Defence documentation.

Defence’s policy approach for the management of general stores inventory

2.5 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual states that Defence’s objective for the management of its inventory is to ensure that Defence Capability Managers are provided with the agreed level of support in the most cost-effective manner.

2.6 The manual also sets out the organisational arrangements and decision-making principles that Defence considers are essential to ‘ensure the efficient and effective use of resources’, to support Capability Manager requirements, and to support ‘One Defence initiatives in seeking a more cost conscious solution for Defence’.

2.7 While it refers to ‘efficient’ and ‘effective’ use, Defence’s logistics management policy is not explicitly framed around the full requirements of section 15 of the PGPA Act (see Box 1) with regards to the proper use of resources. As noted in Box 1, ‘proper’ in relation to the use or management of public resources also includes the requirement for ‘economical’ use. In this context, the Department of Finance defines ‘economical’ as:

(in relation to the proper use of public resources) The extent to which the proposed use avoids waste and sharpens the focus on the level of resources that the Commonwealth applies to deliver results. This generally relates to approving the best cost option to deliver the expected results. Economical considerations must be balanced with whether the use will also be efficient, effective and ethical [emphasis in original].24

2.8 Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that the next release of the Defence Logistics Manual ‘would make more explicit linkages to Section 15 of the PGPA Act.’

Defence’s Single Accountable Logistics Manager approach

2.9 Defence has not effectively operationalised its primary accountability mechanism for the management of inventory items, the concept of a ‘single accountable logistics manager’. The following section examines Defence’s operationalisation of this concept in its management of GSI.

2.10 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual states that:

Each IOS [item of supply] within Defence must have a single accountable Logistics Manager for In-Service Support within a Defence Group … The Logistics Manager is the single point of accountability, facilitating inventory and optimisation support … In doing so, the Logistics Manager may be responsible for the support of an IOS that is associated with a range of higher level products, capability systems and platforms. These are universally referred to as a Common Item.

DLMs [Designated Logistics Managers] are designated by and accountable to the Product Manager (or SPO [System Program Office] Director) or equivalent for the efficient and effective logistics management of assigned items including disposal … In cases where a DLM is responsible and accountable to multiple SPO Directors/Product Managers/customers, any competing pressures can be managed effectively through SLAs [service level agreements]. DLM must act prudently, ethically and lawfully in accordance with Government, Defence and CASG policies and initiatives, including the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, the Public Service Act 1999, Australian Public Service and Defence Values, applicable Work Health and Safety requirements, Legal Services directions, and the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines

…

The DLM must also:

a. act in the best interests of the Commonwealth and provide excellent stewardship of assigned IOS to maximise efficiency, effectiveness and value for money, constantly seeking opportunities for continuous improvement and to ensure Defence Capability outcomes;

b. employ best practice logistics management, ensuring that decisions are made and documented by appropriately qualified and experienced persons, and judiciously managing associated risks;

c. communicate effectively with Capability Manager representatives, the relevant Product Manager/SPO Director, and other related elements of CASG, E&IG, CIOG, JLC, Defence Groups, and industry;

d. lead, enable and motivate their logistics management team to achieve high performance, provide quality advice, and develop productive working relationships;

e. bring any matters that adversely impact on the efficient and effective management of assigned IOS to the attention of the relevant Product Manager or SPO Director; and

f. discharge financial reporting accountability

2.11 The Electronic Supply Chain Manual lists the primary functions of the DLM as including, but not limited to, technical and configuration management, procurement, inventory and repair management and disposal. This includes management of the following.

- The initial codification and cataloguing of inventory items in Defence systems of items upon their introduction into service to support the correct management of that item throughout its life.

- Inventory levels, which includes:

- establishing the stocking policy to meet requirements set out in the agreement/s with Defence’s Capability Managers;

- determining requirements to establish appropriate stocking levels;

- maintaining stocking levels through replenishment activities; and

- maintaining accurate records in Defence systems in accordance with the requirements in the Electronic Supply Chain Manual.

- Disposal of surplus and obsolete items, including the issue of disposal directives.

- The processes for hazardous chemicals and dangerous goods.

2.12 Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that DLM roles are filled by contractors, Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel and Australian Public Service (APS) employees.25 Defence further advised that:

- the Designated Logistics Manager (DLM) is not necessarily a single person or position and may be an organisation;

- the DLM may include several Stock Item Owners (SIOs)26; and

- the Product Manager (PM) can hold the sustainment Integrated Logistic Support Manager (ILSM) responsibility but this is not the DLM.

2.13 Defence confirmed to the ANAO that it has no central record of its DLMs. That is, Defence is unable to identify who has been assigned as a DLM.

2.14 In response to a request for evidence that all items of supply had been assigned to a single accountable DLM, Defence advised the ANAO in November 2022 that:

Within the MILIS Catalogue, Catalogue Management tab, under Stock Item Owner drop down menu employees are listed. The Stock Item Owner (SIO) two digit code is derived from the MILIS Establishment module or organisation Hierarchy in which the employee is as an incumbent to an SIO position.

2.15 Defence’s advice conflates the Designated Logistics Manager (DLM) and Stock Item Owner roles. There is no basis in the relevant Defence policy (DEFLOGMAN) for these roles being equivalent. While Defence’s relevant IT system — the Military Integrated Logistics Information System (MILIS) — provides for items to be assigned a ‘Stock Item Owner’ (see paragraphs 2.18 to 2.20) to identify the managing team for that item within a System Program Office (SPO), MILIS does not identify the DLM for that item. As a result, Defence is unable to provide internal assurance through its IT system (MILIS) that its policy has been operationalised by ensuring that every item of GSI has been assigned to a DLM.

2.16 Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that it can provide internal assurance that items of supply relating to specialist military equipment have a DLM assigned to them, through its internal materiel agreements with capability managers.27

- An Item is assigned to a Materiel Sustainment Agreement through the application identifier.

- Whilst there is no DLM record or table within MILIS, Defence does understand its SME [Specialist Military Equipment] and parent equipment’s [sic]. By definition a SPO Director manages Products which will have a Sustainment manager. These are the DLMs. Materiel Acquisition Agreements and Materiel Sustainment Agreements are proof of the allocated DLM.

Authorising framework for general stores inventory stock holdings

2.17 The authorising framework for inventory stock holdings is not fully documented.

2.18 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual states that all inventory items ‘must’ be associated with an agreement between Defence capability managers and ‘In-Service Support agencies’. Within Defence these agreements include Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs), Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs) and Service Level Agreements (SLAs).28 For Defence GSI, the ‘In-service Support agency’ is CASG, as the Defence group responsible for determining and maintaining the appropriate levels of GSI to support capability manager requirements.

2.19 Defence was not able to provide the ANAO with evidence of how it can provide internal assurance that all its GSI items are associated with an agreement between CASG and capability managers, as mandated by Defence policy. Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that while MILIS contains an agreement identifier field, agreement identifiers vary between the military Services and the field is not populated in every case. Defence further advised that:

Each GSI item has a Stock Item Owner (SIO) identified. Each SIO is mapped to a Product, Platform or Capability. Therefore, every GSI item can be linked to a Materiel Acquisition Agreement or a Materiel Sustainment Agreement.

2.20 While a stock item owner can be identified in MILIS against a stock code, ANAO analysis of 631,823 stock codes comprising GSI as at 7 February 2023 found that two per cent had no stock item owner. This represented less than one percent of total warehouse stock on hand. 97 per cent of stock codes with no stock item owner were stock codes recorded as being merged with other stock codes. Additionally, while MILIS contains a field for identifying products, platforms or capability associated with a stock code, Defence was unable to provide evidence that every GSI stock code was linked to a product, platform or capability.

2.21 As noted in paragraph 1.1, the Defence Logistics Policy Manual further states that Defence holds two broad categories of inventory — operating stocks and reserve stocks.29 The Manual mandates that Defence’s military Service Chiefs and Group Heads distinguish between operating stocks and reserve stocks and manage the requirements accordingly.

2.22 Notwithstanding the distinctions drawn between operating and reserve stocks in Defence policy, Defence advised the ANAO that in the case of GSI, operating and reserve stockholdings ‘are entwined in the broader sense of CASG managing the Capability Managers preparedness requirements, [and] internal/external supply pressures.’ As a consequence, for its GSI Defence has not established arrangements to manage compliance with the mandated requirement that operating stocks and reserve stocks be distinguished and managed accordingly. There is scope for relevant policy and/or administrative arrangements to be adjusted, to prevent avoidable non-compliance.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.23 Where Defence establishes a mandatory requirement, it should also establish effective administrative arrangements to manage compliance with that requirement. |

2.24 In response to this opportunity for improvement, Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that:

Logistics Assurance Branch (JLC) will work with CASG to develop a GSI Management Assurance Framework which will be based on risk and will capture evidence of compliance through independent sample and testing program. This framework will be based on the policies and procedures for the management of GSI under the Enterprise Resource Planning system.30

Planning framework for general stores inventory stock holdings

2.25 The CASG Materiel Planning and Management Policy states that CASG is responsible for determining the ‘most appropriate level of stock to support service level agreements, Service Head Quarters preparedness requirements and supply chain deficiencies and opportunities.’

2.26 Planning for and setting the level of stockholdings is an important task. Too much inventory results in waste. Too little inventory can undermine preparedness efforts and impact capability. Settings are translated into procurement activity through requirements determination, which is the process by which Defence establishes the quantity of an inventory item to be procured.

2.27 The requirements determination process comprises assessment31, requirement computation32 and procurement determination.33 The requirements determination process is supported by data and functionality within MILIS, which includes Defence’s Advanced Inventory Management System (AIMS). How MILIS supports the elements of the requirements determination process is outlined in paragraphs 2.84 to 2.98.

2.28 The ANAO reviewed the instructional material established in Defence policy for the setting of stock levels for operating and reserve stocks. Defence’s procedures for requirements determination do not set out explicitly how authorised levels of reserve stockholdings are to be considered. However, the procedures mandate that stock holding policies are to be considered during requirements computation.

Determining operating stock levels

2.29 The ANAO also reviewed Defence guidance relating to the authorising and planning arrangements for determining GSI operating stock levels and reserve stock levels. The ANAO found that Defence’s arrangements for determining GSI stock holding levels are not fully documented.

2.30 The DEFLOGMAN series does not include any requirements pertaining to setting or authorising operating stocking levels.

2.31 In March 2023 Defence advised the ANAO as follows.

- Operating stock levels are derived from either the ADF Capability Manager or Defence Logistics Information Systems.

- The target settings for operating stock levels are contained within the relevant Materiel Sustainment Agreement, in the form of a Health Indicator, the Demand Satisfaction Rate.

- Evidence of the stocking level required is articulated in the Materiel Sustainment Agreement.

2.32 The ANAO sought clarification on the advice that target settings for operating stock levels are contained in Materiel Sustainment Agreements, as outlined in paragraph 2.31. Defence advised the ANAO in May 2023 that not all Materiel Sustainment Agreements contain target settings for operating stock levels:

Sustainment Performance Management System (SPMS) is utilised by CASG and Capability Manager representatives to report on Product performance metrics. SPMS application … details Supply Chain KHIs [key health indicators], which are a linked to related product schedules and related MSA [Materiel Sustainment Agreements] via the KHI stream … The Demand Satisfaction Rate (KHI) is one of the KHI within SPMS. Not all products measure DSR [Demand Satisfaction Rate] and some measure … as a KPI rather than KHI.34

Determining reserve stock levels

Preparedness objectives

2.33 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual states that:

the process of determining reserve stock requirements must be conducted collaboratively by the Capability Managers and Designated Logistic Managers … based on agreed preparedness objectives contained in the Chief of the Defence Force Preparedness Directive (CPD). The preparedness objectives are supplemented by guidance provided by the Capability Manager.

2.34 Defence’s Preparedness Management Policy outlines how the introduction of ‘Preparedness Posture Settings’ allows for the development of logistics requirements, including deriving contingency stock from parameters included in these settings, specifically duration and response time. The policy also states the following.

- ‘Explosive ordnance and fuel are to be the priority commodities for which Logistics Preparedness Requirements are developed’.

- That ‘detailed processes to determine Logistics Preparedness Requirements will be developed as subordinate documents’, broadly involving: developing and maintaining logistics demand data sets; conducting supply analysis; determining preparedness requirements; and assurance of logistics preparedness requirements.

- That the policy ‘will be replaced with an enduring set of documents by Dec 2021 with support preparedness management procedures to be developed and confirmed in the same timeframe.’ Defence was unable to provide the ANAO with evidence that this had occurred.

2.35 Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that reserve stocks for fuel and explosive ordnance inventories are formally assessed as part of its Strategic Materiel Reserve (SMR) activities — such as SMR-Fuel and SMR-Explosive Ordnance — and that it plans to undertake a similar activity for General Stores Inventory (see paragraph 2.65).

2.36 More generally, Defence advised the ANAO in September 2022 that there is no line of sight between Defence’s GSI holdings and the Chief of Defence Force Preparedness Directive. In March 2023 Defence confirmed this advice and further advised that this was ‘due to security restrictions, between Preparedness directives and GSI holdings.’

Alternative measures to holding reserve stocks

2.37 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual further states that:

Reserve stocks must be held to support Work Up, Operational Viability Period and the Sustainment Period requirements. To ensure there are sufficient reserve stockholdings to support short notice operations and longer term Operational Preparedness Objectives (OPO) requirements, they need to be calculated (or otherwise assessed), considered and procured against a conscious risk management decision largely based on threat (scenario based), discretion, consequence, cost and availability.

…

the holding of reserve stocks is only one of many options for meeting preparedness requirements. Alternative measures include industrial surge, changes to procurement and maintenance plans, re-deployment of training or peacetime stocks and purchase from other nations.

…

funding priorities will inform the decision to establish physical holdings or establish arrangements and agreement to meet the contingency planning.

2.38 Defence was unable to provide evidence to the ANAO of any formal process where Defence actively considers and assesses the alternative measures set out in paragraph 2.37 in deciding whether to establish and maintain reserve stocks of GSI.

Divisional policies on stock holdings

2.39 The Electronic Supply Chain Manual states that the ‘decision on whether to stock an item or to buy for dues out is dependent on division policy and is to be included in the logistics instructions for that division’. The manual defines ‘dues out’ as the ‘total quantities due out for issue on a customer requisitions or warehouse transfers.’

2.40 Defence was unable to provide evidence to the ANAO of such decisions being documented in divisional logistics instructions, as required by the manual.

Prioritising reserve stock levels

2.41 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual further requires the military Service Chiefs and CASG to prioritise reserve stock items as either ‘critical’ or ‘important’ items, as follows.

- Critical items are ‘those that are operationally essential’ to meet requirements.

- Important items are ‘those that are not operationally essential but that provide for enhanced operational performance; and those that are important to effective and efficient support, that can be deferred for a limited time without unacceptable consequences, but that cannot be deferred for as long as Contingency Provisioning Lead Time.’

2.42 Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that Defence systems do not support the identification of ‘critical’ versus ‘important’ items as described in the logistics policy manual. Defence also noted that there was ‘a difference between Supply Critical and Engineering Critical,’ although this distinction is not made in Defence policies and procedures.35 Defence provided the ANAO with an example of a Materiel Sustainment Agreement (MSA) which included a list of critical items, including items which appeared to be GSI. The agreement did not state whether items were ‘engineering critical’ or ‘supply critical’ and did not include ‘important’ items.

Stock holding policies established by Designated Logistics Managers

2.43 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual states that reserve stock holding policy applies to all classes of supply needed to be held by the ADF to meet contingencies.36 Stock holding policies in Defence may be expressed as an entitlement quantity, the number of operating days, reserve or contingency stock requirements.

2.44 Defence’s Electronic Supply Chain Manual explains that establishing a stock holding policy is important because it ‘will impact on the total requirements for an item at all levels within the supply chain’. The manual states that establishing stocking policy is a function of the Designated Logistics Manager.

2.45 Defence advised the ANAO that there is no mandated requirement in these documents to develop stock holding policies.37

Lines of accountability for determining reserve stocks

2.46 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual further states that ‘the process of determining reserve stocks for the ADF requires clear lines of accountability for stating the materiel liability and ensuring other agencies or organisations deliver the necessary support to agreed levels of quantity, quality, cost and time’.

2.47 Defence informed the ANAO that the process of determining reserve stocks is managed between CASG (CASG Domains, Project Management Offices and System Program Offices) and the respective ADF Headquarters and Force Element Groups. In October 2022, Defence advised the ANAO that:

Reserve Stock Quantity (RSQ) represents the amount of inventory reserved for contingency requirements. The amount of RSQ (if any) is determined externally to the AIMS [Advanced Inventory Management System] processes and is either interfaced or entered manually online.

2.48 Defence was unable to provide evidence to the ANAO of a process for determining reserve stock quantities. However, the Operational Supply Chain Supplement to the Electronic Supply Chain Manual provides guidance for the management of contingency holdings or reserve stock quantities held by or on behalf of Army.38

JLC [Joint Logistics Command], in conjunction with CASG [Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, manage a number of contingency caches, stores, equipment and vehicles on behalf of the Services and HQJOC [Headquarters Joint Operations Command]. The majority of contingency stores JLC manage are land materiel, managed on behalf of Army, in support of the Force Generation Cycle (FGC), Defence Aid to the Civil Community (DACC), Humanitarian Aid and Disaster Relief (HADR) and Defence Force Aid to the Civil Authority. Chief of Army articulates the ADF land materiel contingency holding requirements via an annual directive.

…

Contingency holdings, less explosive ordnance (EO) and camp stores designated as minimum stock on shelf are to be categorised on MILIS as category CH (cache).

…

The effective management of contingency holdings is critical to ensure key contingencies can be supported within dedicated timeframes. To achieve effective and efficient management CASG, through the respective National Fleet Managers (NFM) and the JLU [Joint Logistics Unit] are responsible for the daily management of contingency stock. JLU will include contingency stores in stocktake schedules and non-technical and technical inspection programs. The NFM will ensure stock rotation; sustainment, replenishment and governance processes are established and maintained.

To ensure an accurate picture of cache holdings, CASG with assistance from JLC will provide a quarterly report to AHQ [Army Headquarters].

2.49 Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that AIMS forecasting looks at reserve stock quantity in Joint Logistics Unit ‘parent’ warehouses and that while the air domain manages reserve stocks at this level, the land and maritime domains do not, with Army and Navy holding stock at ‘subordinate’ warehouses. Defence further advised that the maritime and land domains manage reserve stock as part of normal consumption.

Agency support agreements and reserve stock levels

2.50 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual states that where necessary, agreed levels of reserve stocks will normally be referred to in agency support agreements (Materiel Acquisition Agreements or Materiel Sustainment Agreements) developed between the supporting agencies and the respective Services.

2.51 Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that:

Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs) and Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs) cover Raise, Train, and Sustain (RTS) activity and then what the Capability Manager requires based on their Military Response Option (MRO) analysis. This is not necessarily referred to as Reserve Stocks.

Joint contingency reserve stocks

2.52 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual also requires CASG, under the direction of and in collaboration with the Service Chiefs, to establish and manage a Joint Contingency Reserve Stock for inventory items with a high degree of commonality among the ADF Services (known within Defence as Common Items — see paragraph 2.10).39

2.53 Defence was unable to provide the ANAO with any agreements, plans, or documents for any such Joint Contingency Reserve Stocks.

Reserve stocks as a capital investment

2.54 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual refers to establishing ‘reserve stocks as a capital investment’.

2.55 In contrast, Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that ‘GSI would not be a capital investment as it is consumed’. Defence further advised that:

Where the initial value of an acquired asset is above the relevant capitalisation threshold … the asset is expected to be used for more than twelve months, and the costs can be measured reliably, the item must be recorded (capitalised) as an asset, against the relevant asset class and in the appropriate logistics or financial management system (i.e. MILIS or ROMAN). The asset is referred to as a ‘Reportable Asset’.

Review of reserve stocks

2.56 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual requires the application of controls and reporting arrangements to maintain and preserve approved reserve stockholding levels. Defence policy further requires that reserve stockholdings be reviewed on a regular basis to ensure that they continue to meet changing preparedness objectives.

2.57 Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that the review of reserve stockholdings is provided for through Materiel Acquisition Agreements and Materiel Sustainment Agreements. The MSAs provided by Defence for ANAO review (discussed at paragraph 2.42) linked ‘critical’ reserve stock (see paragraph 2.41) items to annual Defence Management and Financial Plan planning activities.40

Managing for a balanced inventory

2.58 Defence’s Electronic Supply Chain Manual states that ‘one goal of inventory management is to establish and maintain a balanced inventory’. It describes a balanced inventory as one where ‘appropriate levels of held stock satisfy an acceptable proportion of customer demands, within cost constraints.’ It further states that ‘an understocked inventory will result in poor customer satisfaction, whereas an overstocked inventory is indicative of poor funds utilisation.’

2.59 CASG’s Materiel41 Planning and Management Policy is intended ‘to ensure that materiel management is accountable, auditable and ensures a greater balance and certainty of the inventory position’. The policy defines balanced inventory as:

the most efficient and effective stocking levels to meet operational and capability requirements, as stated in Material [Materiel] Sustainment Agreements, including Safety Stock that ensures against any unforeseen emergency, fluctuation and/or expenditure, delays in production and transit or misfortune.

2.60 To support the achievement of a balanced inventory and the related concept of ‘materiel optimisation’, CASG’s Materiel Planning and Management Policy contains two policy directives. These are outlined in Box 3 below.

|

Box 3: Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) Materiel Planning and Management Policy directives — materiel optimisation and balanced inventory |

|

First policy directive This policy directive mandates ‘materiel optimisation’ for every item of inventory, with the goal of providing uninterrupted customer service levels at optimum cost. The policy states that compliance with the inventory optimisation policy will:

The policy directive requires CASG Product Support Managersa to ‘maximise the relationship between costs, constraints, risks and target service levels for operating stock and supplementary stocking policies, and authorises CASG Designated Logistics Managers to implement ‘materiel planning strategies to support the Defence supply chain.’ The policy directive refers to a supporting procedure, which is described as providing ‘the effective planning processes for achieving a balance of inventory across the Defence supply chain’. As discussed further in paragraph 2.69, the supporting procedure was ‘suspended’ by CASG in July 2020 for a complete re-write, which has not occurred. Defence advised the ANAO in March 2023 that the ‘materiel optimisation’ requirement was first implemented in 2011 in the context of the Balanced Inventory Project, which ran from 2011 to 2013b, and that the rationale for the requirement was to change inventory management practices that had resulted in Defence carrying significant inventory overstocks (see Appendix 3 of this audit report). The Balanced Inventory Project transition plan identified risks that ‘could jeopardise the successful transition and ability for DMO [the Defence Materiel Organisation] to leverage of[f] the environment established by the BIP [Balanced Inventory Project]’. The identified risks included the following.

Defence further advised the ANAO in March 2023 that optimising inventory so that it could respond to a threat would be an important part of how inventory was managed in the future, including determining what is required to respond to scenarios in a preparedness context. Defence was giving deeper consideration to what stock it held and making sure it was fit for purpose in the context of a ‘changing geo-strategic environment’ and the 2023 Defence Strategic Review commissioned by government.c Second policy directive This policy directive requires stock assignment codes to be assigned to inventory items in MILIS to justify, and provide visibility of, variations to a balanced inventory in the form of overstocking. CASG’s ‘materiel optimisation’ policy sets out eight MILIS stock assignment codesd for use by CASG Domains and SPOs and assigns approval delegationse and expiration times to each. As discussed further in paragraph 2.71, Defence has not complied with its documented stocking strategy policy directive. |

Note a: The role of Product Support Manager is usually performed by CASG SPO Directors.

Note b: The Balanced Inventory Project transition plan included a schedule for ongoing SPO health checks, with reference to a centralised inventory management Centre of Excellence ‘to ensure monitoring of the PMF [performance measurement framework] and future health of inventory management.’

Note c: A public version of the Defence Strategic Review (DSR) was published on 24 April 2023.42

Note d: The eight stock assignment codes are: Contingency Stock; Deployment Allowance; Global Slow-Moving Items; Life of Type (LOT); Insurance Stock; Project Stock; Value for Money Stock; and Safety Stock.

Note e: The delegations to approve supplemental stocking strategies range from the Capability Manager to APS 6 or equivalent positions depending on the stocking strategy.

Source: Defence documentation and Defence advice to the ANAO.

2.61 The ANAO’s analysis found that as of 7 February 2023, some 1,499,235 items, representing 2.08 per cent of GSI warehouse stock on hand, were calculated to be ‘balanced’ by Defence’s Advanced Inventory Management System (AIMS) (see footnote 83 and Figure 3.1). Of those items, 74.08 per cent was comprised of items assigned inventory segmentation codes that identify that AIMS should be used to conduct requirements determination (see paragraphs 2.86 to 2.89).

2.62 The achievement of a ‘balanced inventory’ and ‘materiel optimisation’ of GSI, as required by the policy directives outlined in Box 3, would contribute to achievement of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requirement for proper use and management of public resources, including efficient and economical use. As discussed in Box 3, at the time of this audit the first policy directive was not being implemented by CASG and the second policy directive was not being complied with within CASG.

2.63 The policy directives are intended to assist relevant personnel to operationalise the policy objectives of achieving ‘balanced inventory’ and ‘materiel optimisation’, including the rationale for holding overstocked GSI. Overstocking without a clear policy rationale introduces the risk of inefficient and uneconomic procurement and management of inventory. Defence senior management should clarify the status of the two policy directives, and review their implementation, to provide clear direction to responsible personnel and assurance regarding the proper use and management of public resources.

Recommendation no.1

2.64 The Department of Defence clarify the status, and review the implementation, of the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group’s Materiel Planning and Management Policy and associated procedures, to ensure that there is a documented rationale for holding general stores inventory identified as overstock.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

2.65 Defence will consider the output of key strategic inputs to Defence preparedness and planning, including the Defence Strategic Review (DSR) and Strategic Materiel Reserve (SMR) reviews, and strengthen CASG materiel planning and overstocking management policy and procedures.

Maintenance of policies and non-compliant practices

2.66 The ANAO examined Defence’s maintenance of, and compliance with, key policies and associated procedures that are applicable to the management of its GSI.

2.67 The ANAO’s review indicates that Defence has not maintained key documents in its policy and procedural framework for GSI to ensure the documents are contemporary and relevant. The principal shortcomings in policy and practice are discussed below.

Out of date policies

2.68 The Defence Logistics Policy Manual references the following out-of-date information.

- Superseded policy documents, such as the Defence Security Manual. The manual was replaced by the Defence Security Principles Framework in July 2018.

- Both CASG and Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) Accountable Authority Instructions. The DMO was disbanded in 2015 and its principal responsibilities were transferred to CASG. As a group within Defence, CASG does not have a separate accountable authority.

- Superseded legislation — the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 — which was replaced by the PGPA Act in 2013.

- Historical Defence organisational and administrative arrangements. There are references to the DMO and the manual identifies the Commander Joint Logistics (CJLOG) as the senior accountable officer for logistics, which has not been the case since 2020.

2.69 CASG’s Materiel Planning and Management policy on mandating inventory optimisation directs the reader to a supporting procedure on how to optimise inventory. That procedure was ‘suspended’ by CASG in July 2020 for a complete rewrite. This has not occurred, leaving Defence staff without a procedure on how to optimise inventory since that time.

2.70 CASG has not reviewed its inventory management procedures in accordance with the requirements of its Quality Management System.43 All four of the CASG Materiel Logistics procedure documents relevant to this performance audit were ‘cancelled’, based on the sunset provisions included in each procedure. Three documents were cancelled in 2020 and one was cancelled in November 2022. Based on the sunset provision within CASG’s Materiel Planning and Management Policy, the policy itself was ‘cancelled’ at the end of March 2023.

Non-compliant practices

2.71 CASG practice with regards to central performance reporting of inventory balances, to determine whether inventory is optimised, is non-compliant with the documented CASG procedures. This is discussed further in paragraphs 3.11 to 3.17.