Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Delivery of Australia's Consular Services

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s delivery of services to Australians travelling or residing abroad.

Summary

Introduction

1. Australia’s consular services encapsulate the assistance the Australian Government provides to protect the welfare and interests of Australians travelling or residing abroad, and advice and information services provided to the Australian public. The provision of consular services to nationals within another country is governed by international laws and consular practice, including the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations 1963 (which allows for a country to safeguard, help and assist its nationals abroad1) and bilateral agreements between Australia and other countries.2

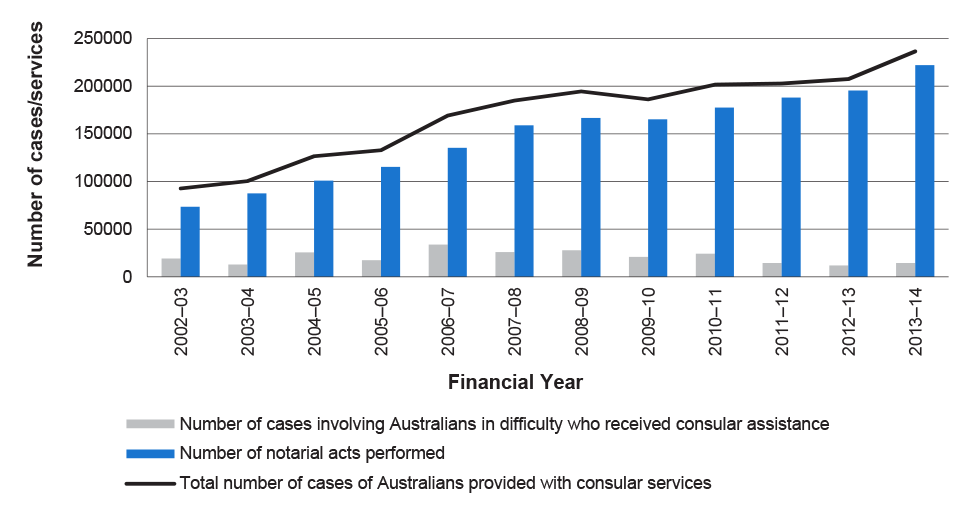

2. While the Australian Government may ‘give humanitarian assistance to Australian citizens and permanent residents whose welfare is at risk abroad, while respecting their rights to privacy’3, the provision of assistance abroad is a discretionary service with no service standards or requirements mandated in legislation. In practice, however, there is a general expectation amongst the Australian public that the Australian Government, through its consular services, will provide a ‘safety net’ for its citizens while overseas.

3. The ability of the Australian Government to intervene in cases of Australians in difficulty abroad, particularly in serious cases such as imprisonment or child custody disputes, is limited. The Australian Government has no jurisdiction in a foreign country and Australian travellers are ultimately bound by the laws and requirements of the country in which they travel. While the Government provides advice and information to assist travellers in making safe travel decisions, travellers are ultimately responsible for their own safety and taking actions to mitigate their own travel risks.

4. As of June 2014, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) delivered Australia’s consular services to Australians abroad through 167 diplomatic posts4, which are located in 121 countries around the world. Australia had a reciprocal consular sharing agreement with Canada, where Australians are able to access consular services from 14 Canadian missions, and an agreement with Romania to allow Australians to access services through that country’s embassy in Syria. In countries without a DFAT presence and not covered by these agreements, services are provided by the nearest accredited post.5

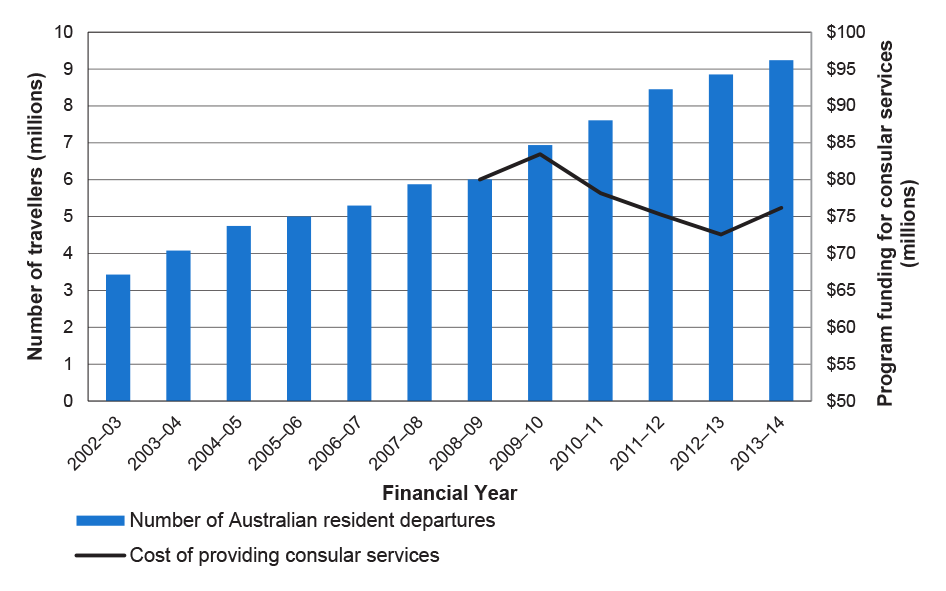

Consular services

5. The term ‘consular services’ broadly describes three categories of activity: providing travel advice and information to travellers relevant to their safety and security while abroad; providing consular assistance to travellers abroad and their next of kin, including those in difficulty; and coordinating and responding to crisis events overseas that involve Australians, such as natural disasters or terrorist attacks. DFAT’s overseas posts may also provide Australians with notarial services6, voting facilities, and the contact details of government authorities in Australia.

Travel advice and information

6. DFAT provides the Australian public with travel advisories and information on countries to inform them of potential security risks and other relevant travel information on the smartraveller.gov.au website. Travellers are encouraged to register their travel plans on the website to enable DFAT to contact them in the event of an emergency. The department promotes these services, encourages the uptake of travel insurance, and raises awareness of consular issues commonly experienced by travellers via its Smartraveller public awareness campaign.

Consular assistance

7. DFAT’s Consular Services Charter7 outlines the types of consular assistance that it can provide to Australian travellers, and the limitations of this assistance. Such assistance can include advice and support in cases of accident, serious illness, occurrence of a serious crime, or death, including providing lists of local support services (such as hospitals or lawyers); information, assistance and potentially evacuation in the event of a major crisis; and in some circumstances, as a last resort, financial assistance, including government-funded repatriation of Australians. Over the past 12 years, the number of cases of consular assistance provided to Australians in difficulty aboard has ranged from 11 000 to more than 30 000 per year.

Crisis response

8. DFAT is also responsible for the coordination of the Australian Government’s response to consular crisis events abroad, such as a terrorist attack or suspected attack; conflict or civil disorder—actual or imminent; a transport or industrial accident; and natural disaster. This coordination role includes: crisis preparation, planning and readiness activities; the establishment and management of crisis response support teams to rapidly deploy to missions; and working with key Australian Government agencies. A recent example of a consular crisis is the Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 incident in Ukraine in July 2014, that resulted in 298 deaths, including 28 passengers with Australian citizenship and a further 10 passengers residing in Australia. DFAT’s crisis response involved the coordination of several stakeholder agencies such as the Australian Federal Police and Australian Defence Force, in addition to the department’s own crisis response activities.

Demand for consular services

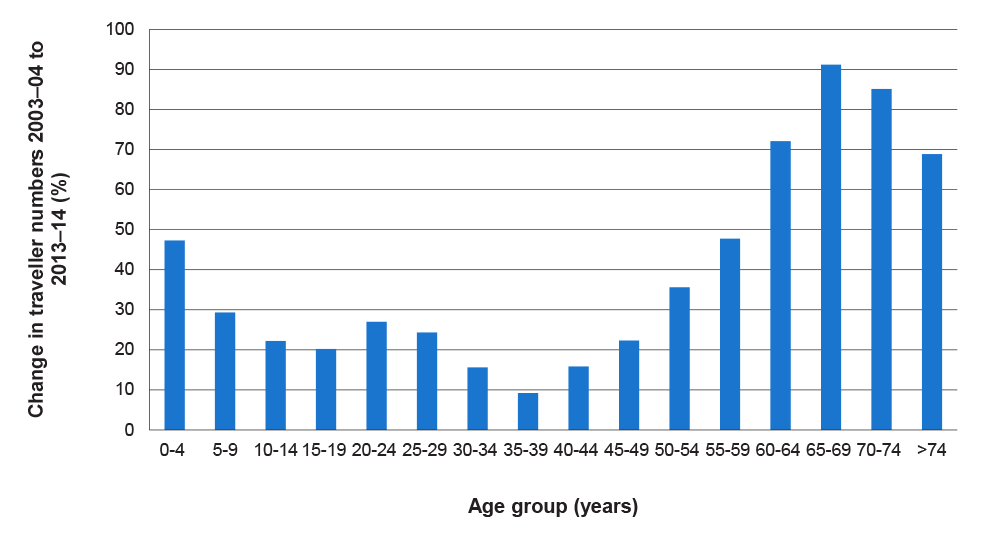

9. The demand for, and nature of, consular services has evolved over time, reflecting changes in traveller numbers and demographics. Changes in the travel industry, such as lower airfares and improved standards, has resulted in more Australians travelling abroad more often, including higher risk groups such as the elderly and children.8 These changes have led to a greater demand for consular services. Other key drivers for this increase include significant incidents that have impacted on travellers, such as:

- terrorist activities and natural disasters, where an intensive and rapid consular response is required; and

- the rising expectations of individuals and their families about the level of assistance provided, partly driven by media interest in higher profile cases.

10. Over the past 12 years, the number of Australian traveller departures has increased by around 170 per cent, from 3.4 million in 2002–03 to 9.2 million in 2013–14. Consistent with this increase, the number of travellers provided with consular services has steadily increased from 92 000 cases in 2002–03 to 236 600 cases in 2013–14.9 Meanwhile, funding for consular services, under Program 2.1: Consular Services of DFAT’s Portfolio Budget Statements, peaked in 2009–10 at $83.5 million and steadily declined to $72.6 million in 2012–13. The level of funding has since increased to $76.2 million in 2013–14, and DFAT advised the ANAO that the total estimated cost of the consular services program for 2014–15 is $85.0 million.

Audit objective and criteria

11. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s delivery of services to Australians travelling or residing abroad.

12. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- effective strategies were in place to support the delivery of consular services to Australians in selected countries;

- appropriate arrangements were in place to engage with, and provide, Australians travelling or residing abroad with information relevant to their safety and security;

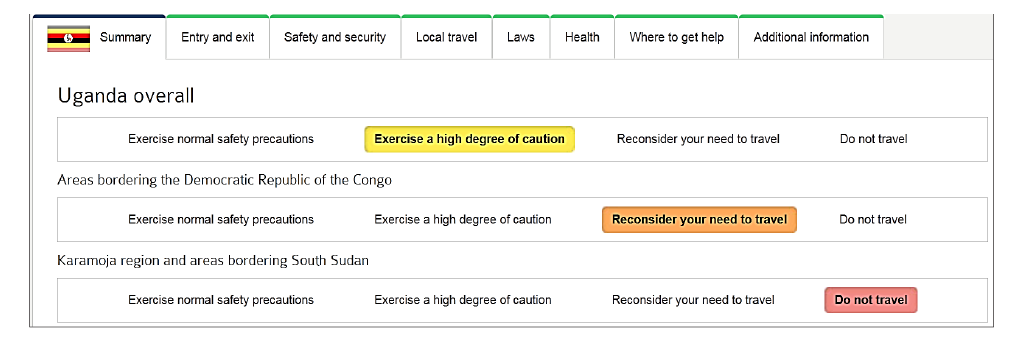

- accessible consular services were provided for Australians travelling abroad who required assistance; and

- the capacity to respond to, and coordinate, a consular crisis had been established.

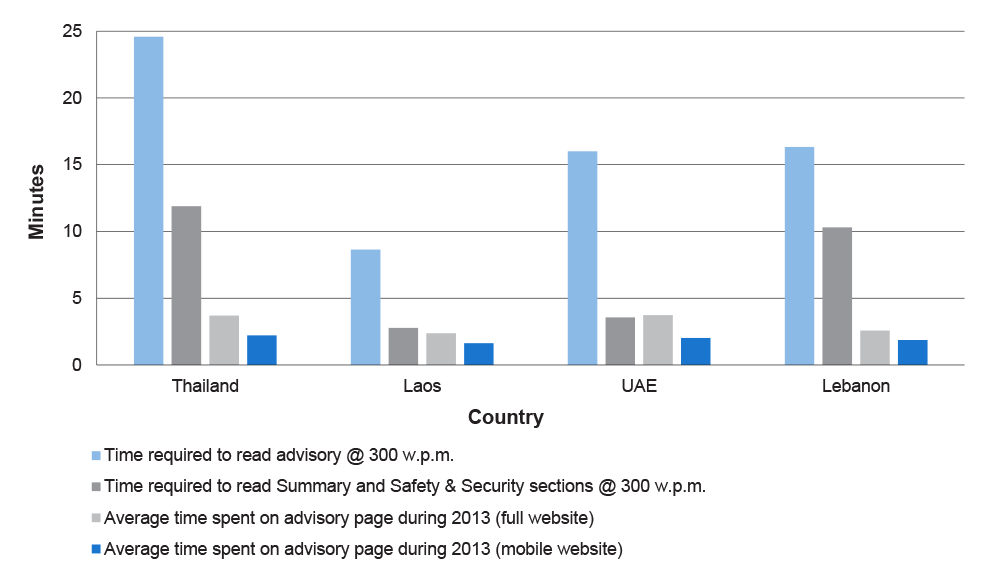

13. In conducting this audit, the ANAO observed the delivery of consular services in four of DFAT’s overseas posts, and one Austrade post.10

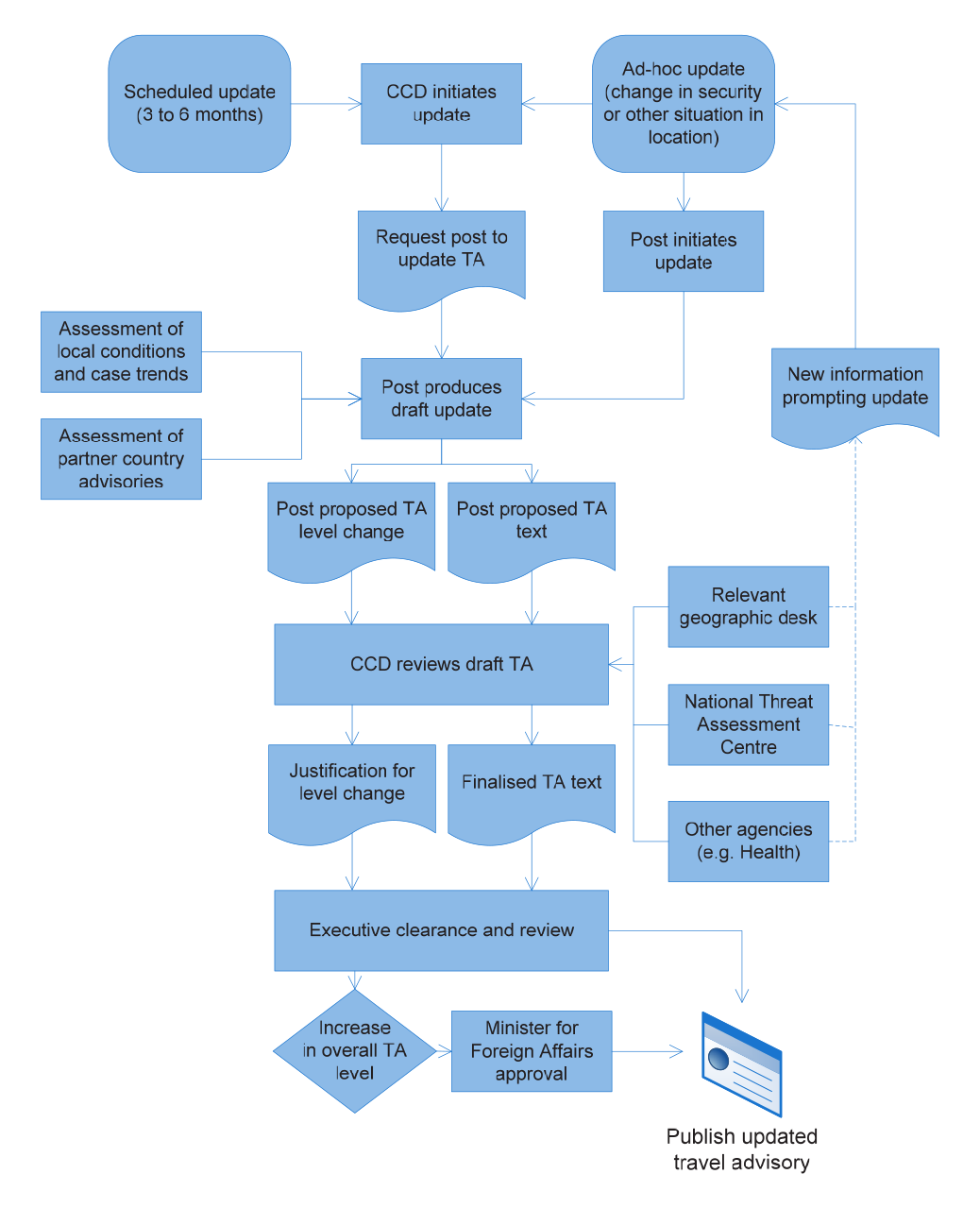

Overall conclusion

14. The operating environment for consular services is complex and DFAT delivers these services through a global network of 167 posts. Each of the countries where Australia maintains posts has unique legal, logistical and security-related factors that influence the types of services and assistance that DFAT can provide. Demand for services is increasing, and the situations in which DFAT is called upon to provide consular assistance are becoming increasingly complex due to changes in Australian traveller demographics and behaviour.

15. DFAT’s delivery of consular services to Australians travelling or residing abroad includes advising Australians of issues relevant to their safety and security overseas; providing consular assistance to Australians in difficulty; preparing and responding to crisis events; and developing strategies to manage these services in an environment of increasing demand and complexity. DFAT’s capacity to intervene in individual cases is defined in the Consular Services Charter and, inevitably, perceptions as to the adequacy of the services provided to individual Australians will vary.11 Within this context, DFAT’s administration of consular services is broadly appropriate, and these services are generally delivered effectively. DFAT’s dispersed network of service delivery locations, however, and the variety of work undertaken across this network, creates challenges for DFAT in ensuring that relevant policies and guidance are adhered to and accurate performance information is collected and reported to senior management and key external stakeholders, including the Parliament.

16. DFAT recently released its consular strategy for 2014–16.12 Prior to this, DFAT had not articulated its strategic direction for consular services, nor integrated its approach to engaging with consular stakeholders. The strategy sets its future focus and strategic direction for the delivery of consular services and also outlines plans to improve the targeting of services to those individuals most in need, including cost recovery or possible limitation of assistance to individuals who knowingly or repeatedly compromise their own safety. In introducing the new strategy (and proposed changes), it will be important to manage and, where necessary, adjust the expectations of the public, by ensuring the strategy is adequately communicated, and the circumstances in which cost recovery or service limitation might be applied clearly explained.13 DFAT intends to incorporate messages regarding the limits to consular assistance, and the need for traveller self-reliance, into the Smartraveller campaign in future.

17. The Smartraveller campaign, currently in its third phase, has raised awareness of DFAT’s consular services among the Australian public. The campaign has been informed by several successive rounds of market research and evaluation and its overall administration is sound. Despite high levels of awareness, the department has experienced difficulty in translating this success into behavioural change by the travelling public. There would be merit in DFAT reviewing those messages of the Smartraveller campaign which have proven less successful, such as promotion of the traveller registration system. Despite high levels of awareness among the public, the system is poorly utilised and promotes an attitude of dependency among those who complete the process.

18. While DFAT has predominantly sound practices for the provision of most aspects of consular services, the rationale for and documentation of key decisions, such as those related to the provision of financial assistance, is inconsistent. Developing an annual, risk-based, quality assurance process for consular assistance functions would provide assurance that procedures are being consistently applied. Such assurance is particularly important in the case management context, due to the increasing complexity of consular cases, the unique nature of many cases, and the need to consider clients’ welfare.

19. There is also scope for DFAT to strengthen its oversight and coordination of the lessons that can be learned from consular crises and related contingency planning. Consular crisis events are unique, they are also comparatively infrequent and demanding, placing a premium on contingency planning prior to events and capturing the lessons learned after events occur. While DFAT has responded well to recent crises, stronger emphasis should be given to the consistent and coordinated implementation of departmental post-event review findings. Incorporating these findings into future assessments of risks, contingency planning, and crisis response exercises would better position DFAT to respond to future events.

20. DFAT’s key performance indicators are aligned with its program objectives, but do not provide a clear and complete picture of overall program performance. The department also lacks accurate and reliable performance information necessary for informed management decision-making, and to provide assurance that service delivery standards are being met across the network. These shortcomings could, in part, be addressed through proposed improvements to DFAT’s Consular Management Information System (CMIS) and improved data entry.

21. DFAT has acknowledged the need to improve its delivery of consular services, and has identified areas for improvement as part of its recently released consular strategy. To assist this process, the ANAO has made three recommendations relating to improving consular case management processes and crisis response arrangements, and performance reporting.

Key findings by chapter

Stakeholder Engagement (Chapter 2)

22. DFAT’s consular stakeholders are diverse, including Australians travelling and residing abroad, Australians contemplating or planning travel, and the broader travel industry. DFAT engages with these stakeholders through its Smartraveller campaign and the Smartraveller Consultative Group of travel industry representatives. The department’s ability to successfully engage with these target groups should reduce the need for consular assistance over time.

23. The Smartraveller campaign was launched in September 2003 and is one of DFAT’s primary means of disseminating travel advice and information to the public, and encouraging safe travel practices. Smartraveller consists of a website, www.smartraveller.gov.au, an advertising campaign (spanning radio, television, print and online media) and a social media presence online. The most recent phase of the campaign (Smartraveller Phase III) commenced in November 2011 and received funding of $13 million over four years. Phase III focuses on three key behaviours: register travel plans; subscribe to travel advice updates; and insure yourself and belongings.

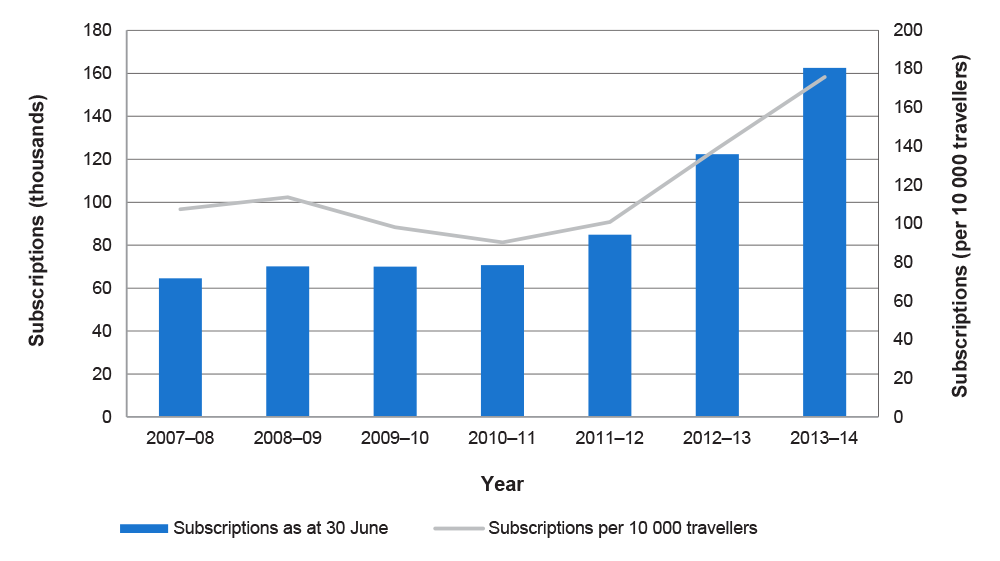

24. The Smartraveller campaign has generally been successful in raising the awareness of these three key focus areas. The ANAO’s analysis found that the proportion of travellers subscribing to travel advisories has increased by 75 per cent between 30 June 2012 and 30 June 2014, from 100 subscriptions per 10 000 travellers to 175 subscriptions per 10 000 travellers. DFAT has also received anecdotal evidence from the travel industry suggesting greater use of travel insurance. The department’s third message relating to registration, however, has proven less effective. Internal research commissioned by DFAT in 2013 indicates that 77 per cent of Australians recognise the importance of registering their travel itinerary, yet despite these high levels of awareness the use of the registration system remains very low.14 The research also indicated that registration could encourage a mindset of dependency that the department seeks to avoid.15 The ANAO’s analysis of Smartraveller website data also suggests that travellers become disengaged during the registration process as only 20 per cent of those who visit the starting page complete the registration process.

25. Low levels of take-up of the registration process reduce its value in providing DFAT with the contact details of Australians in the event of a crisis or other emergency overseas. In addition, the system cannot be relied upon to accurately provide the number and location of those Australians abroad who have registered, because of the extensive error rate of registrations.16 While DFAT intends improving the ease of the registration process as part of its consular strategy, there would also be merit in the department conducting a broader review of its ongoing utility, particularly in light of moves by other countries such as the United Kingdom to abandon similar universal registration processes in favour of more targeted approaches that use mobile phone applications and social media to connect to their citizens when a crisis or other emergency occurs.17

26. The overall success of the Smartraveller Phase III campaign is difficult to determine as there were no specific targets set out in the beginning of the campaign. DFAT has outlined improved performance measures in its communications strategy for Smartraveller Phase IV.

27. DFAT’s Consular Charter provides an overview of the department’s role in providing consular services, and outlines the expectations the department has of travellers—such as making sensible safety arrangements—and the expectations travellers should have of DFAT. The department’s consular strategy, released on 3 December 2014 outlines, for the first time, DFAT’s future strategic direction for consular services, including plans to improve the targeting of services to those individuals most in need, and mechanisms to limit assistance to, or recover costs from, those who knowingly or repeatedly compromise their safety overseas. It will be important for the department to develop and communicate appropriate guidance (for DFAT staff), and outline to the public the circumstances when provisions will be used so that travellers’ expectations of the department are properly managed.

Travel Advisories (Chapter 3)

28. DFAT issues travel advisories for more than 160 destinations that are intended to provide information to Australian travellers about safety and security, as well as practical advice on travel-related topics such as health, local laws and customs. Each advisory includes one of four advisory ‘levels’18 to indicate the overall severity of safety and security risks to travellers, and a map of the destination.19 Travellers value travel advisories, with internal market research commissioned by DFAT finding that 83 per cent of surveyed travellers agreeing that the advisories provide practical advice about destination countries.

29. Younger travellers and the elderly comprise an increasing proportion of Australia’s travelling demographic, and as of 2013–14 made up approximately 33 per cent of travellers. The department has also seen increases in travellers from non-English speaking backgrounds and a greater use of mobile devices such as smartphones to access travel advisory content.20 DFAT has improved its engagement with younger travellers and those using mobile devices by developing a Smartraveller iPhone app and promoting advisory updates via social media.

30. The ANAO’s analysis suggests that travellers are unwilling to invest the time needed to read the lengthy travel advisories. The average visitor to DFAT’s travel advice pages spends less than a third of the time required to read an advisory in its entirety. For some high-risk destinations for which DFAT provides highly detailed commentary of the local security situation, the average time on the website is insufficient to read even the safety and security information. The ANAO found that this commentary is often lengthier than that of international counterparts; the United Kingdom’s terrorism warnings for low risk countries were, on average, 50 per cent shorter than those issued by DFAT. Additionally, only eight per cent of travellers surveyed by DFAT in 2010 who accessed travel advisories indicated that they had changed their in-country behaviour as a result of the advice. Reducing the length of advisories, improving the conciseness of messages and using simpler language, would also make advisories more accessible to those with limited English language backgrounds.

31. DFAT’s travel advisories are subject to ongoing change. New advisories are issued for new destinations, and existing advisories updated to include new information or changed to reflect a new travel advisory level. In 2013–14, DFAT made 877 updates to its travel advisories. Each overseas post is responsible for reviewing the content of their advisories, risk assessing local threats and providing updated text to DFAT’s Consular and Crisis Management Division (CCD) for approval. CCD consults with other stakeholders (including external agencies, and policy areas within DFAT) to seek further input. DFAT’s processes for developing and updating travel advisories are sound. However, to be effective, these processes need to be followed consistently by DFAT’s staff at its overseas posts, particularly in recording the rationale behind their risk assessments. The ANAO’s examination of the documentation of risk assessments for five21 travel advisories found one instance where the travel advisory level had been downgraded with no risk assessment being provided to CCD, and a lack of documentation to support the rationale for maintaining current risk levels in all instances.

Provision of Consular Services Overseas (Chapter 4)

32. The demand for consular services continues to increase, in line with the increase in overseas travel by the Australian public. The assistance rendered by DFAT is often complicated by difficult overseas environments, and the needs of higher risk travellers such as the young and elderly. Consistent with these trends, the number of travellers provided with consular services has risen from 92 000 cases in 2002–03 to 236 600 cases in 2013–14.22 Over the same period, the number of consular assistance cases for Australians in difficulty has ranged from 11 000 to more than 30 000 per year.

33. Each consular assistance case presents unique service delivery challenges emphasising the importance of consistency and equity in service delivery. A sound administrative framework helps to ensure decisions are appropriate, clearly communicated and, where necessary, subject to review. While DFAT has internal guidelines that set out the assistance it can provide, the basis by which the department makes key decisions about the assistance that will (or will not) be provided was not always adequately documented. The ANAO’s analysis of a sample of 35 consular repatriation cases from 2013–14, found that consular case documentation did not consistently provide a clear record of the reasons not to provide repatriation funding.23 Although DFAT has in place informal oversight arrangements24 to provide assurance to management that the decision making process by which it assesses the need for and provides consular assistance is sound, the management of the consular assistance caseload is not currently supported by a quality assurance process that is independent from case decision making. An annual risk-based quality assurance process undertaken by the CCD teams25 would provide greater assurance that the services DFAT delivers to its clients across the diplomatic network are equitable, and delivered in accordance with relevant policies and guidance.26 Such a program could also highlight good practices and areas for improvement.

34. DFAT has identified that its Consular Management Information System (CMIS) is outdated, and efforts to replace it have been an ongoing process since 2003. CMIS has a limited ability to provide performance reporting information, and is inconsistently used. For example, in a sample of 20 prisoner cases, ANAO analysis showed that the ‘date of the last consular visit’ field was not completed in 30 per cent of the cases, while for those cases for which the field was completed, the recorded date varied by an average of 588 days from the date identified in the case notes.27 As such, CMIS can offer little assurance to management as to the state of a post’s workload and the service standards delivered at posts.

Crisis Readiness and Response (Chapter 5)

35. Under the Australian Government’s Emergency Management Arrangements, DFAT has responsibility for managing the preparation for, and response to, an overseas crisis event in collaboration with other Australian and overseas stakeholders. DFAT has responded to several crises in recent times, including the October 2013 Lao Airlines aircraft (QV301) crash in Pakse, Typhoon Haiyan in November 2013, and most recently, the MH17 disaster in Ukraine in July 2014. Crisis preparations may also be activated in preparation for a major event (including sporting events such as the FIFA World Cup). DFAT continues to refine its framework for responding to such events in light of these experiences.

36. DFAT’s network of overseas posts each prepare contingency plans for crisis events. The department has recently developed a new Crisis Action Plan (CAP) template, that combines posts’ business continuity and consular contingency plans. This process has improved and simplified posts’ crisis arrangements.28 The earlier post consular contingency plans examined by the ANAO averaged 144 pages in length; the new CAPs average 53 pages. The new plans could be further improved by considering additional secondary risks that could complicate a crisis response. These risks are more localised and can relate to failures of key infrastructure (such as electricity or water supplies) or financial systems (necessitating a supply of available currency), problems with transportation, or lack of basic necessities such as food, water and hygiene equipment in a location.29 It is recognised that many posts have informal arrangements to cooperate with consular partner nations on crises in their accredited countries, supplemented by a number of formal agreements with select nations in some areas. These have the potential to increase the scope of Australia’s ability to respond to, and mitigate, crises overseas and should be included in the CAPs.

37. DFAT has several mechanisms to refine and review its crisis preparation, including the use of Contingency Planning Assistance Teams (CPATs) that work with posts to test and develop their existing contingency arrangements, and a formal lessons learned evaluation process that occurs at the end of every crisis event. While these processes have identified improvements that could be made to the department’s contingency planning and crisis response arrangements, DFAT was not able to demonstrate that these issues had been addressed and the recommendations implemented, where relevant, across the network.30 DFAT’s existing processes for learning from crises would benefit from greater centralised coordination and oversight to help ensure that any improvements resulting from these exercises and CPAT visits are implemented by the relevant overseas posts.

Consular Performance Monitoring and Reporting (Chapter 6)

38. DFAT’s performance framework for consular services consists of four key performance indicators (KPIs) relating to service delivery, provision of travel advice, contingency planning and crisis response. There are no targets or definitions to support the KPIs.

39. While DFAT’s KPIs provide useful information regarding trends in consular service delivery, they lacked sufficient detail, and do not provide a basis to enable the department, and other key stakeholders including the Government and the Parliament, to assess the extent to which the objectives for the delivery of consular services are being achieved. Other countries, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, make use of other performance measures including client satisfaction, response times to client assistance needs, and the ratio of travellers requiring consular assistance. There would be merit in DFAT considering international experience in reviewing its performance measures.

40. DFAT’s reporting against these KPIs did not include results (or quantifiable targets) in both 2012–13 and 2013–14, and was limited to providing consular activity metrics, such as the number of consular cases and phone calls received from the public.

Summary of entity response

41. DFAT’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, with the full response at Appendix 1.

DFAT notes the ANAO’s conclusion that DFAT’s administration of consular services is broadly appropriate and that services are generally delivered effectively. The audit report provides assurance to the government, DFAT’s Senior Executive and the travelling public that the delivery of consular services is efficiently managed by the department.

DFAT accepts the ANAO’s three recommendations and will work towards implementing them. DFAT notes that a number of the findings in the audit were addressed in the department’s Consular Strategy 2014–16, which was commenced by the department in November 2013 and launched by Ms Bishop in December 2014.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 4.59 |

To strengthen the management and oversight of consular services to Australians abroad, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade:

DFAT’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 5.44 |

To strengthen its crisis preparations and response capabilities, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade:

DFAT’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 6.15 |

To improve the transparency and reporting of consular service delivery, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade:

DFAT’s response: Agreed |

1. Background and Context

This chapter outlines the background of Australia’s consular services and the focus of the audit.

Introduction

1.1 Australia’s consular services encapsulate the assistance the Australian Government provides to protect the welfare and interests of Australians travelling or residing abroad, and advice and information services provided to the Australian public.

1.2 The provision of consular services to nationals within another country is governed by international laws and consular practice, including the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations 1963 (which allows for a country to safeguard, help and assist its nationals abroad31) and bilateral agreements between Australia and other countries.32

1.3 While the Australian Government may ‘give humanitarian assistance to Australian citizens and permanent residents whose welfare is at risk abroad, while respecting their rights to privacy’33, the provision of assistance abroad is a discretionary service with no service standards or requirements mandated in legislation or law. In practice, however, there is a general expectation amongst the Australian public that the Australian Government, through its consular services, will provide a ‘safety net’ for its citizens while overseas.34

1.4 The ability of the Australian Government to intervene in cases of Australians in difficulty abroad, particularly in serious cases, such as imprisonment or child custody disputes, is limited. The Australian Government has no jurisdiction in a foreign country and Australian travellers are ultimately bound by the laws and requirements of the country in which they travel. While the Government provides advice and information to assist travellers in making safe travel decisions, travellers are ultimately responsible for their own safety and taking actions to mitigate travel risks.

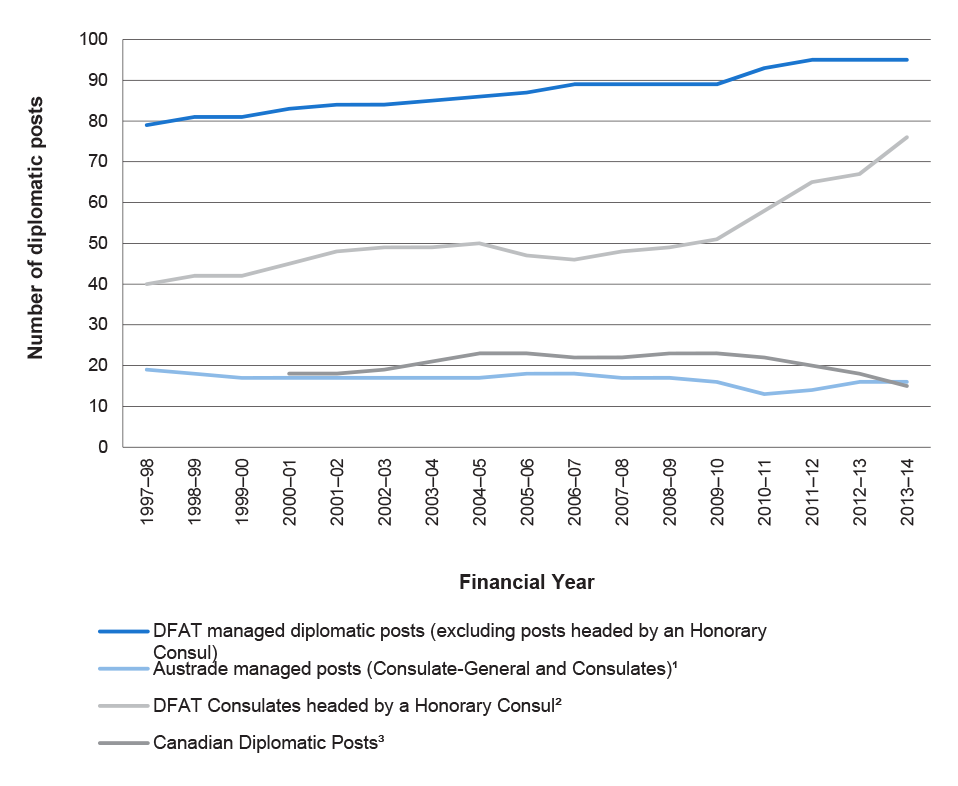

Consular services—helping Australian travellers

1.5 As at 30 June 2014, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) delivered Australia’s consular services to Australians abroad through 167 diplomatic posts35 in 121 countries across the world, including an Honorary Consul network and 16 posts managed by the Australian Trade Commission (Austrade). In addition, Australia has a reciprocal consular sharing agreement with Canada, where Australians are able to access consular services from 14 Canadian missions36, and an agreement with Romania to allow Australians to access services through the Romanian embassy in Syria. The delivery of consular services by diplomatic posts is supported by a Consular Emergency Centre located in Canberra, which provides a 24 hour, seven day a week service for Australians abroad and/or their next of kin in Australia.37

Consular services

1.6 DFAT uses the term ‘consular services’ to describe all travel-related services provided to Australians both overseas and domestically. The consular services provided by DFAT fall into three core activities:

- providing travel advice and information to travellers relevant to their safety and security while abroad;

- providing notarial services and consular assistance to travellers abroad, and their next of kin, including those in difficulty; and

- coordinating and responding to crisis events overseas that affect Australians, such as natural disasters or terrorist attacks.

Travel advice and information

1.7 DFAT provides the Australian public with travel advisories and information on countries, issues and events to inform them of potential safety and security risks and other relevant travel information on the smartraveller.gov.au website. Travellers are also encouraged to register their travel plans on the website to enable DFAT to contact them in the event of an emergency.

1.8 DFAT promotes these services, encourages the uptake of travel insurance, and raises awareness of consular issues commonly experienced by travellers via the Smartraveller public awareness campaign. As part of the Smartraveller campaign, DFAT is using various channels to target and inform Australian travellers, including commercial television advertising, printed media advertising and social media, such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

Consular assistance and notarial services

1.9 DFAT’s Consular Services Charter38 outlines the types of consular assistance that DFAT can, and cannot, provide to Australian travellers, with assistance including the provision of:

- advice and support in case of accident, serious illness, occurrence of a serious crime, or death, including providing lists of local support services (such as hospitals or lawyers);

- information, assistance and potentially evacuation in the event of a major crisis;

- notarial services, voting facilities, and the contact details of government authorities in Australia; and

- in some circumstances, as a last resort, financial assistance, including government-funded repatriation of Australians.39

1.10 Notarial services (such as certifying copies of documents and witnessing signatures, statutory declarations and affidavits) account for the majority of consular services provided, with 222 000 of the 236 600 cases in 2013–14. Consular assistance cases—categorised by DFAT as ‘assistance to Australians in difficulty’—were around 14 600 for the same period.

1.11 Consistent with the increase in Australian travellers over the past 12 years, the number of travellers provided with consular services has steadily increased from 92 000 cases in 2002–03 to 236 600 cases in 2013–14 (as shown in Figure 1.1). Over the same period, the number of consular assistance cases has ranged from 11 000 to more than 30 000 per year. This variability is largely due to the number of inquiries about Australians abroad who could not be contacted by their next of kin in Australia during a crisis event.40

Figure 1.1: Total number of Australians provided with consular services (2002–03 to 2013–14)

Source: DFAT annual reports.

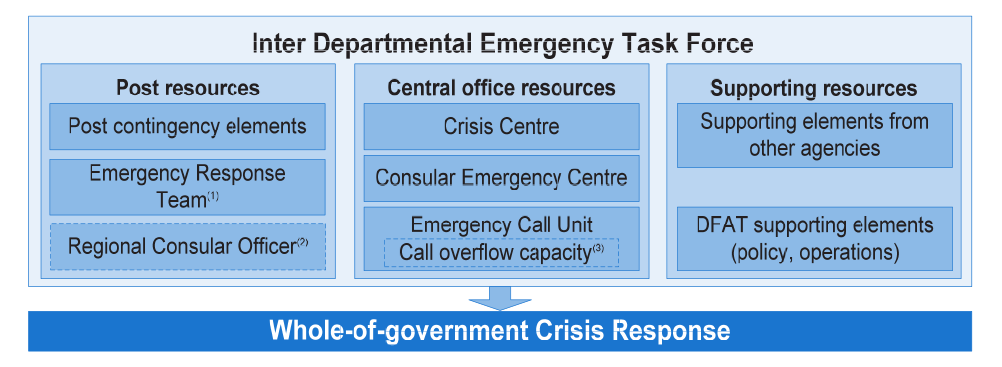

Crisis response

1.12 DFAT is also responsible for the coordination of the Australian Government’s response to consular crisis events abroad.41 This coordination role includes: crisis preparation, planning and readiness activities; the establishment and management of crisis response support teams to rapidly deploy to missions; and working with key Australian Government agencies. Recent consular crises have included:

- the Lao Airlines aircraft (QV301) crash in Pakse, southern Laos on 16 October 2013, resulting in 49 deaths including six Australian citizens;

- Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines on 7 November 2013, which resulted in around 5700 casualties, including two Australian deaths; and

- the Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 incident in Ukraine in July 2014, resulting in 298 deaths, including 28 passengers with Australian citizenship and a further 10 passengers residing in Australia.

1.13 In each of the above crises, DFAT coordinated the response to the disaster with staff, both in Canberra and at the scene of the crisis, from several stakeholder agencies, such as the Australian Federal Police and Australian Defence Force.

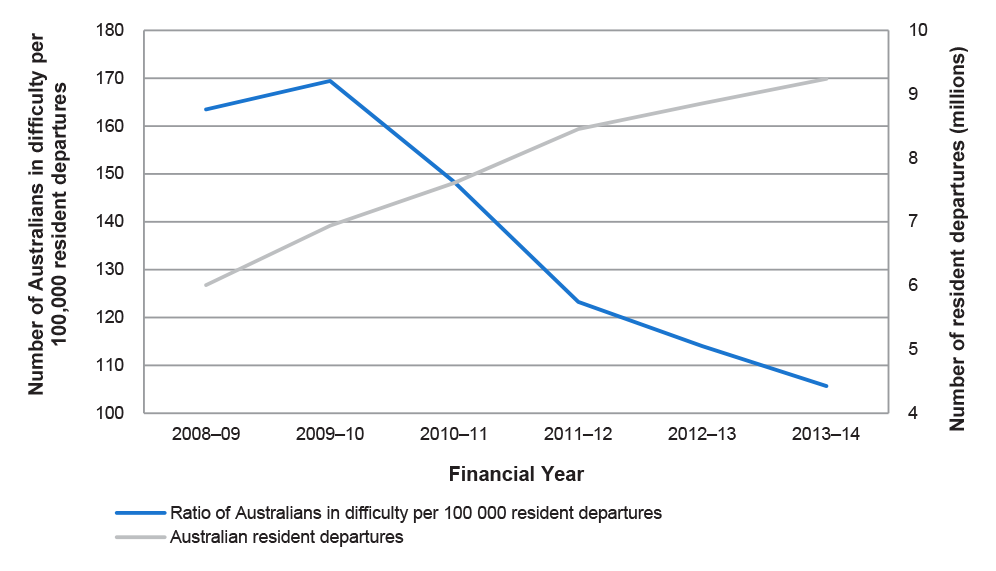

Consular demand

1.14 The demand for, and nature of, consular services has changed over time, reflecting changes in traveller numbers and demographics. Changes in the travel industry, such as the lower cost of air travel and improved standards, has resulted in more Australians travelling abroad more often, including higher risk groups such as the elderly and children.42 These changes have led to a greater demand for consular services. Other key drivers for this increase include significant incidents that impact on travellers, such as:

- terrorist activities and natural disasters, where an intensive and rapid consular response is required; and

- rising expectations from individuals and their families about the level of assistance provided, partly driven by media interest in higher profile cases.

1.15 Over the past 12 years, the number of Australians travelling abroad has increased by around 170 per cent, from 3.4 million traveller departures in 2002–03 to 9.2 million in 2013–14. Meanwhile, funding for consular services peaked in 2009–10 at $83.5 million and steadily declined to $72.6 million in 2012–13.43 The level of funding has since increased to $76.2 million in 2013–14, and DFAT advised the ANAO that estimated costs for 2014–15 will be $85.0 million. The increase in Australian travellers over time and the budget to provide consular services is shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Number of Australian traveller departures (2002–14) and cost of consular services (2008–14)

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT Annual Reports and Portfolio Budget Statements.

Note: Prior to 2008–09, the reported budget for consular services was combined with passport services. Since 2008–09, the budget for consular and passport services has been reported separately.

Stakeholder entities

1.16 While DFAT is primarily responsible for the provision of consular services, the following government entities are involved in supporting DFAT’s consular activities:

- Austrade: delivers consular services at several of its overseas posts;

- Department of Defence: contributes to DFAT’s contingency planning for crisis events and, in some cases, logistic and evacuation support in the event of a crisis;

- agencies in the intelligence, security and law enforcement community that may assist in responding to crisis events, and through the National Threat Assessment Centre44 contribute to risk assessments used to inform travel advisories;

- Department of Health: provides advice regarding disease outbreaks and public health issues that may be included in travel advisories;

- Emergency Management Australia: has ownership of several whole-of-government crisis response plans, and responsibility for receiving repatriated casualties from overseas in the event of a mass casualty event;

- Department of Immigration and Border Protection: assists with the processing of returning Australians in the event of a crisis; and

- Department of Human Services: provides support to repatriated Australians and, through Centrelink, supports DFAT in responding to telephone enquiries during a crisis event.

1.17 More broadly, DFAT’s external consular stakeholders include the travel industry, travel associations, the media, Australian businesses operating overseas, and the general public. DFAT engages with several of these stakeholders via a forum established as part of the Smartraveller campaign, known as the Smartraveller Consultative Group.45

Audit coverage

1.18 The provision of Australia’s consular services by DFAT has previously been examined in the following ANAO audit reports:

- Audit Report No.31 2000–01 Administration of Consular Services; and

- Audit Report No.16 2003–04 Administration of Consular Services Followup Audit.

1.19 The initial ANAO audit in 2000–01 followed a Parliamentary Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee June 1997 report, Helping Australians Abroad–A Review of the Australian Government’s Consular Services. The Committee’s report included 23 recommendations to improve consular services. The ANAO audit included the review of DFAT’s progress in implementing these recommendations.

1.20 The audit found that, in general, consular services were satisfactorily administered and that DFAT had strengthened the arrangements to prevent Australians from experiencing difficulties abroad by focusing its staff on the provision of consular services. Notwithstanding these improvements, the audit found weaknesses in supporting management processes and administrative systems, including: travel advice and information arrangements; the case management system; performance management arrangements; and contingency planning. The audit made six recommendations to address these weaknesses.

1.21 The 2003–04 follow-up audit reviewed and reported DFAT’s progress in implementing the six recommendations from the previous audit. The audit concluded that DFAT had implemented one recommendation and was in the process of implementing another three recommendations. Two of the recommendations—relating to performance management and registration of Australians abroad—had not been addressed by DFAT. The follow-up audit made two further recommendations in relation to the new consular case management system and contingency planning.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

1.22 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s delivery of services to Australians travelling or residing abroad.

Audit criteria

1.23 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- effective strategies were in place to support the delivery of consular services to Australians in selected countries;

- appropriate arrangements were in place to engage with, and provide, Australians travelling or residing abroad with information relevant to their safety and security;

- accessible consular services were provided for Australians travelling abroad who required assistance; and

- the capacity to respond to, and coordinate, a consular crisis had been established.

Audit methodology

1.24 In conducting this audit, the ANAO: interviewed DFAT officers; reviewed DFAT files and documents and analysed relevant data; and observed the delivery of consular services in four of DFAT’s overseas posts, and one Austrade post.46 The audit team also invited contributions to the audit from members of the Smartraveller Consultative Group, and members of the public via the ANAO’s Citizen Input Facility.

1.25 The ANAO also analysed a sample of 245 consular case management records (approximately 15 per cent of cases under management) from Abu Dhabi, Atlanta, Bangkok, Beirut, Copenhagen, Dubai, London, Los Angeles, New York and Vientiane. These cases spanned the variety of case types managed by DFAT, including prisoner and arrests, hospitalisation, welfare, child abduction, death, assault, general enquiries and notarial services, theft, whereabouts and repatriation.47

1.26 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $590 000.

Report structure

1.27 The structure of this report is shown below:

|

Chapter |

Chapter Overview |

|

Chapter 2: Stakeholder Engagement |

This chapter examines DFAT’s strategies for delivering consular services, including engagement and communication with stakeholders. |

|

Chapter 3: Travel Advisories |

This chapter examines the arrangements established by DFAT to provide Australians travelling and residing abroad with information relevant to their safety and security. |

|

Chapter 4: Provision of Consular Services Overseas |

This chapter examines the arrangements that DFAT has in place to manage access to, and the provision of, consular services, including case decision-making and the management of case information. |

|

Chapter 5: Crisis Readiness and Response |

This chapter examines DFAT’s arrangements for preparing and responding to consular crisis events, including contingency planning undertaken at Australia’s overseas posts, the management of crisis events by DFAT Canberra and the evaluation of these events. |

|

Chapter 6: Consular Performance Measurement and Reporting |

This chapter examines the performance measurement and reporting arrangements supporting DFAT’s delivery of consular services. |

2. Stakeholder Engagement

This chapter examines DFAT’s strategies for delivering consular services, including engagement and communication with stakeholders.

Introduction

2.1 DFAT’s consular stakeholders are diverse, including Australians travelling and residing abroad, their families and friends, Australians contemplating or planning travel, and the broader travel industry. Promoting safe travel behaviours requires DFAT to tailor messages and communication methods to appropriately target each stakeholder group. DFAT’s ability to successfully engage with these groups should minimise the need for consular assistance over time.

2.2 The primary means by which DFAT engages with target groups is through information disseminated to, and accessed by, consular stakeholders via: the Smartraveller campaign, including internet content and advertising activities that are managed centrally by CCD. Individual posts communication with Australian travellers and residents is through post websites, email lists, social media accounts and printed material.

2.3 The ANAO examined DFAT’s strategies for the delivery of consular services and its engagement with stakeholders, including through its Smartraveller campaigns and post communications.

Consular strategy

2.4 As discussed in Chapter 1, the consular services that Australians can expect to receive from DFAT are outlined in the Consular Services Charter. The Charter provides an overview of DFAT’s role in providing consular services, includes the services DFAT can and cannot provide48, the expectations the department has of travellers—such as making sensible safety arrangements—and the expectations travellers should have of DFAT.

2.5 In late 2013, DFAT identified the need for, and commenced developing, a consular strategy to outline the focus and strategic direction for the delivery of consular services over the period 2014–2016.49 The strategy was endorsed by the Minister for Foreign Affairs in November 2014, and is intended to assist the department to manage broader public expectations, and to provide strategic direction to DFAT’s consular activities. The consular strategy focuses on the following five areas:

- promoting a culture of responsible travelling and self-reliance;

- raising public awareness and informing the public of travel issues;

- providing more assistance to those who need it most, including vulnerable clients;

- striving to improve Australia’s consular services; and

- improving the training, development and skills of consular officers.

2.6 The strategy also introduces the possibility of limiting consular assistance to those clients who knowingly engage in behaviour that is illegal, or to those who deliberately or repeatedly engage in reckless or negligent behaviour that puts themselves or others at risk. As part of the process of developing the strategy, the department also revised the Charter, to align the two documents.

2.7 The recent release of the consular strategy on 3 December 2014 will better place DFAT to manage the delivery of consular services within a changing global environment. However, in introducing possible limits to the services provided and cost recovery arrangements, it will be important that the department develops guidance for DFAT staff to ensure that consular assistance is consistent and equitable across the network. Advising the public as to when such provisions may be applied will also be necessary if travellers’ expectations of the department are to be adequately managed. DFAT advised the ANAO that such provisions are expected to apply in ‘a very small minority’ of cases, and that decisions to limit assistance would in most cases be made in consultation with the Minister.50

Consular communications strategy

2.8 In October 2014, as part of its preparations for the next phase of the Smartraveller campaign (Smartraveller Phase IV) scheduled to launch in 2015, DFAT finalised a new consular communications strategy. This strategy primarily discusses how DFAT will promote its revised Smartraveller campaign (discussed below), but also explores how the department intends to work with other consular stakeholders to promote its key messages. Mechanisms the department intends to use during Phase IV include targeted paid advertising (particularly television and digital); enhanced use of social media and mobile messaging to disseminate key messages (including sending ‘alerts’ in a crisis); engagement with the travel industry through partnerships, public relations activity and an expanded Smartraveller Consultative Group51; outreach programs to engage with travellers at key points in their travel planning; and development of resources and publications that target segments with special travel needs.

2.9 The communications strategy is supported by research, planning, evaluation and dedicated funding, as discussed later in this chapter. However, some elements of DFAT’s consular communication activities, such as those conducted by posts, are not explicitly incorporated into Smartraveller communications planning. Articulating the role that post activities have in the Smartraveller communications strategy will help ensure that consular communication activities are aligned and focused on key objectives.

Smartraveller campaign

2.10 The Smartraveller campaign was launched on 7 September 2003 by the then Minister for Foreign Affairs, with the campaign being conducted in a series of phases, each running for several years. The current phase, Phase III, commenced in November 2011. Broadly, the campaign phases focused on the following themes:

- Phase I: Raising awareness of Smartraveller;

- Phase II: Raising awareness and promoting behavioural change; and

- Phase III: Building on levels of awareness to focus on behavioural change.

2.11 Total funding for Smartraveller Phase III is $13 million over four years and is separate from general consular services funding. The Consular and Crisis Management Division (CCD) is responsible for managing the campaign. Phase III focused on three key behavioural messages for the travelling public, which are outlined in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: DFAT’s Smartraveller messages

Source: www.smartraveller.gov.au.

2.12 The ANAO examined the department’s approach to raising awareness of Smartraveller among travellers, consultation with the travel industry, communicating the key messages, and how the performance of the campaign has been measured.

Raising awareness

2.13 The website smartraveller.gov.au is DFAT’s primary tool for conveying consular information. It consists of the primary website and a mobile sub-site m.smartraveller.gov.au, which features the same content in a form more suitable for viewing on a mobile device. DFAT has also produced a Smartraveller iPhone app, which in addition to providing the standard content of the mobile website, also features a simplified process for users to register their travel itinerary.52

2.14 The Smartraveller websites provide a variety of content for Australian travellers, including travel advice for selected countries, travel bulletins for major events and specific incidents and specialised guidance for select demographics (for example, business people; children; persons with dual nationality; lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex individuals; seniors; youth; and women).

Campaign Advertising

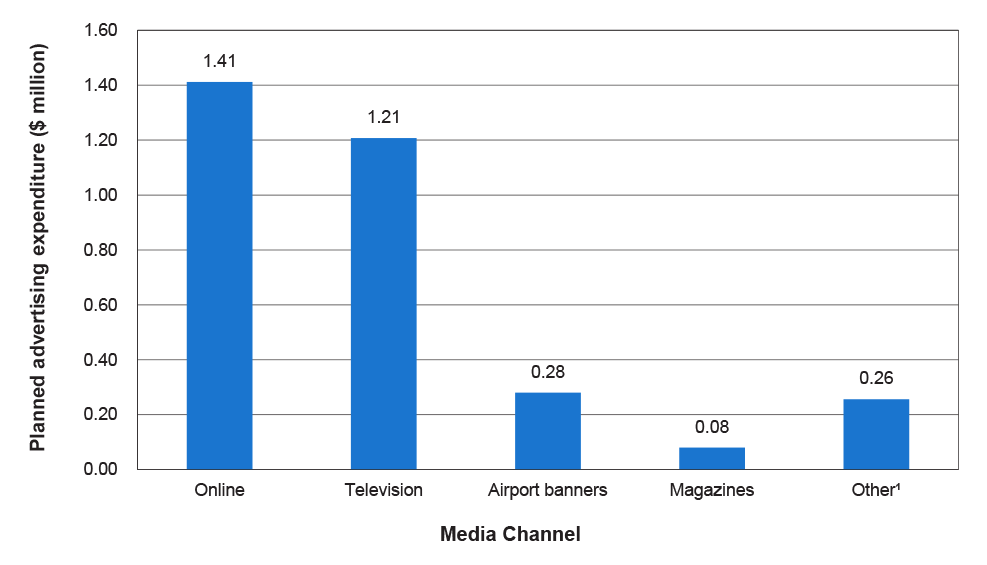

2.15 The Smartraveller campaign aims to raise travellers’ awareness of consular issues through a range of advertising media, including radio, television, print, and online advertising. DFAT has also sponsored travel industry events as avenues to promote the Smartraveller brand and messages, and provided free wireless internet in Australian airports during peak holiday periods as a promotional tool. Figure 2.2 shows the 2013–14 Smartraveller advertising expenditure across the various media channels.

Figure 2.2: Planned Smartraveller advertising expenditure by channel (2013–14)

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT Smartraveller media plan.

Note 1: ‘Other’ includes advertising in languages other than English, and advertising targeted to hearing impaired audiences.

2.16 DFAT’s advertising method selection and expenditure is based on the recommendations of contracted media consultants, with the booking of advertising space managed through whole-of-government advertising arrangements.53

Social media

2.17 Online social media platforms, while presenting risks, also provide opportunities for agencies to engage with their stakeholders in new, and more active, ways. DFAT operates Smartraveller-themed social media accounts, controlled centrally by CCD, to promote and share safe travel practices, information, and Smartraveller resources. DFAT uses Facebook and Twitter accounts to post brief summaries and provide links to advisories and other information. A selection of Smartraveller video content, including advertisements and country travel advice and information has also been added to DFAT’s YouTube channel.

2.18 The department takes a relatively passive approach to the interactive capabilities inherent in social media platforms. The ANAO examined DFAT’s Facebook account activity for a one-month period.54 During this period, DFAT made 68 posts and received 1179 public comments in response. Of these, 26 asked a question of DFAT, to which the department made nine replies.55 The ANAO also observed three instances where members of the public disputed elements of DFAT’s travel advisories, or advised travellers that the local situation was less dangerous than outlined in the advisory. DFAT did not respond to these comments and advised the ANAO that responding to every comment would be resource prohibitive, but that responses will always be given to questions or when an Australian is in trouble.

2.19 In November 2014 DFAT hosted a live forum on its Smartraveller Facebook account, in which consular and passports officers responded to questions from participants on a range of issues. The initiative is a positive example of two-way engagement and, if done on an occasional basis, could potentially improve DFAT’s social media presence and offer value to the public with minimal implications for the department’s resource position.

2.20 The use of multiple communication channels also creates challenges in delivering a consistent message across all platforms. The ANAO observed that information presented by social media is not updated as frequently as DFAT’s travel advisories on the Smartraveller website and, as a consequence, may not be consistent with this advice. For example, the DFAT YouTube channel contains Smartraveller-branded ‘travel advice’ videos featuring a consular officer discussing local conditions for 11 countries. As at June 2014, these videos had not been updated since March 2012, with one video continuing to advise that ‘thousands’ of Australians travelled to a location ‘and generally have a great time’ despite that country being subject to DFAT’s current travel advice level of ‘Reconsider Your Need to Travel’. During the course of the audit DFAT informed the ANAO that the outdated content would be removed.

2.21 DFAT recognises that social media enables the department to enhance its engagement with its stakeholders, but also requires a clear strategy that articulates how these platforms will be used, taking into account resource implications and the ongoing investment in maintaining consistency of messages. The Smartraveller Phase IV Communications Strategy incorporates the results of market research from media and advertising agencies that found that users of DFAT’s Facebook page did not express a preference for more interactive content, but identified that the department may experience resource pressures managing its social media presence, particularly in crisis situations, as users expect their comments and messages to be responded to promptly. Additionally, the provision of inconsistent advice has the potential to adversely affect the reliance placed on travel advisories, and while it may not always be appropriate to engage with social media participants, there is a risk that incorrect or inappropriate user comments may be perceived to be ‘endorsed’ by the department if some form of response is not forthcoming.

Television media

2.22 In 2014, DFAT provided a commercial television network with access to the consular and passports areas of the Bangkok embassy, to produce a television documentary series covering incidents of Australians receiving consular services in Thailand. The series aired nationally in late 2014, and has provided DFAT with a vehicle to promote its consular function, and safe travel messages, to a wide audience.

Travel industry consultation

2.23 The Smartraveller Consultative Group was established by DFAT in 2004 as a joint initiative between the Government and the travel industry to enhance and promote safe travel messages. The group meets on a biannual basis, is chaired by DFAT and includes senior representatives from various bodies in the travel industry.56

2.24 The feedback provided to the ANAO on the Smartraveller campaign indicated members are generally satisfied with the operation of the consultative group. Notwithstanding this view, there were a number of suggested improvements, including the broadening of the involvement of the group to include consular issues more generally—as the group’s current focus is limited to the Smartraveller campaign—and expanding the membership to include online travel providers. The recently released consular strategy highlighted DFAT’s intention to expand the role and membership of the group to become the key stakeholder outreach body on consular matters.

Key Smartraveller messages

Traveller registration

2.25 Registering travel plans is one of the three key Smartraveller messages, with DFAT encouraging travellers to provide details of their itinerary prior to departure. This process is promoted as a means to allow DFAT to contact or locate Australians abroad, particularly in an emergency. Registration is available via the Online Register of Australians Overseas (ORAO), an online form on the Smartraveller website, in person at DFAT’s overseas posts, or by mailing a form to CCD. In addition, travel groups—such as tour groups or schools—can email travel details to DFAT for manual entry into ORAO. The cost of operating ORAO in 2013–14 was $189 147.57

2.26 While ORAO is used by DFAT to locate Australians during an emergency and to estimate the number of Australian travellers visiting, or residing in, an overseas location at a point in time, the rates of registration across the traveller community are generally low. In 2012–13, DFAT reported a total of 1 179 000 registrations58, compared to 8 856 000 Australian resident departures. The department noted that ‘it remains the case that only a minority of Australian travellers register their travel’59, with ORAO registrations typically understating the actual number of Australians in a location by a factor of between five and 10. Registration figures do, however, typically increase during a consular crisis.

Barriers to travel registration

2.27 Market research commissioned by DFAT in 2013 indicated that 77 per cent of Australians recognise the importance of registering their travel itinerary. However, surveyed travellers indicated they would be more likely to register if the process:

- was simple, took minimal effort and was convenient;

- articulated and provided a compelling benefit;

- was promoted during the booking process;

- provided guarantees of privacy protection; and

- was automatically linked to information collected at the time of departure.

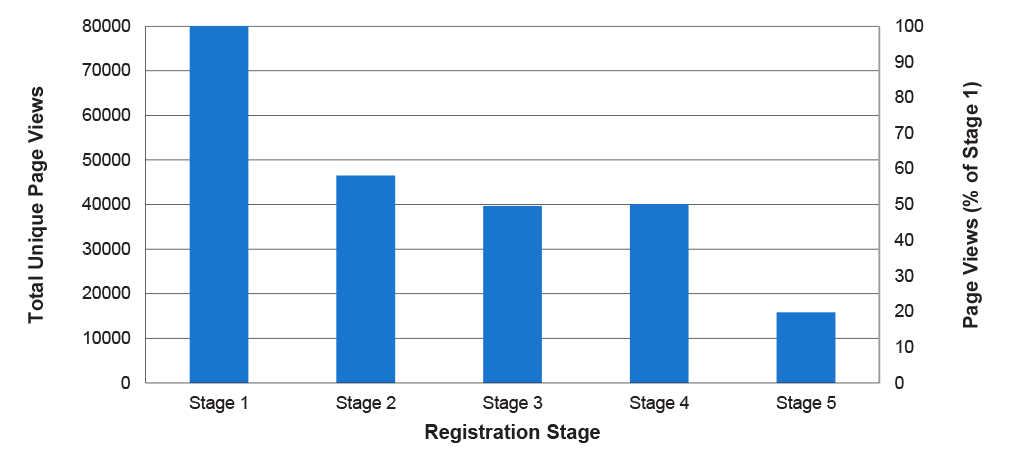

2.28 The ANAO’s analysis of DFAT’s Smartraveller website data suggests that, while travellers may be initially interested in registering, many become discouraged during the process, which requires travellers to complete questions on a series of online pages. Only 20 per cent of those travellers who visit the starting page progress to the final page, as outlined in Figure 2.3. The department advised that it has recently launched a new starting page (in November 2014) highlighting the importance of registration and the information required to complete the process.

Figure 2.3: Smartraveller website registration progression

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT website data.

2.29 Selecting a travel destination in ORAO is also difficult for users. For example, travellers are required to select their destination from a single list of 603 options which are neither filtered nor limited by location. Of these 603 choices, 182 are duplicated variations.60 Filtering the list of destinations, such as by region, then country, and removing potentially confusing duplicate options may assist travellers to more efficiently complete the registration process. DFAT’s consular strategy has flagged that the department will introduce modifications to the registration system to make it easier to use.

2.30 Research conducted during Smartraveller Phase III indicated that travellers would value an automated registration system that is integrated with travel booking arrangements, for example the ability to share itineraries from agents/airlines/other intermediaries at the point of booking. DFAT is not, however, able to accept automated registration information from travel agents and other providers because of limitations to the current Consular Management Information System (CMIS).61 As DFAT is intending to replace the ORAO system as part of its redevelopment of CMIS, there would be merit in exploring the costs and benefits of receiving registration data from approved agents as part of the new system.

2.31 In 2010, the department commissioned an evaluation of the Smartraveller Phase II campaign, and research for the forthcoming Phase III campaign. The research found that the benefits of registration were not clear to travellers. Many travellers considered that they achieved a similar benefit by informing their family and friends of their travel plans, and maintaining contact via social media, and did not perceive an additional benefit in registering with DFAT. Further, the research found that encouraging registration created a perception that the Government would provide a ‘safety net’ in the event of an emergency, and that this perception may conflict with the attempts by DFAT to encourage self-sufficiency.

2.32 The value of registering travel details is adversely affected where incorrect information is entered. Many registration fields, such as contact addresses and passport numbers, are free-text fields, which may result in travellers registering with erroneous information.62 DFAT is aware of these issues, and acknowledges that data is often incomplete or inaccurate, undermining its usefulness, and is often of limited value except as a starting point for following up whereabouts inquiries. The department has also considered the possibility that registration encourages complacency, by implying a level of assistance that may not be available.

2.33 DFAT informed the ANAO that it intends to address data integrity issues during its redevelopment of CMIS, by making greater use of drop-down menus and data verification where possible. While the recently released consular strategy states that it intends to review the ease of use of the traveller registration system, the department is yet to clearly articulate how it intends to address broader issues regarding the value of registration information and the behavioural effects on travellers of providing a registration service.

2.34 Research completed in 2010 also suggested that providing registration facilities in airport departure areas post-check-in—such as Smartraveller ‘kiosks’—may encourage travellers to register at a time when few other activities are available. Such kiosks were trialled by DFAT in 2003 but were limited to providing travel advice, and were ultimately withdrawn due to low usage rates. More recently, DFAT has explored areas of potential collaboration with the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (Customs), including the use of Customs-provided kiosks for registration services, but no formal arrangements or plans are currently in place.

International registration systems

2.35 Consular partner nations—Canada, New Zealand, the United States of America (USA) and the United Kingdom (UK)—also operate similar traveller registration systems:

- the Safe-travel registration system from the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade63;

- the Registration of Canadians Abroad service, delivered by Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada64; and

- the Smart Travel Enrolment Program delivered by the USA State Department.65

2.36 Until May 2013, the UK operated a comparable system called LOCATE. However, the UK discontinued this system as less than one per cent of UK nationals abroad were found to use it.66 Instead, the UK has promoted subscription to travel advisories, and the use of mobile applications and social media registration tools that are activated when a crisis or similar emergency occurs. There would be benefit in DFAT considering the experiences of international partners when reviewing the future direction for the traveller registration system.

Subscriptions to travel advisories

2.37 DFAT allows travellers to subscribe to email notifications that travel advice has been updated, and this service forms one of the key Smartraveller messages. The service is provided independently of travel registration—registering an itinerary with DFAT will not subscribe a traveller to travel advice updates for the countries selected. Travellers can also subscribe to travel advisories using the Smartraveller iPhone app, which can send a notification to the user’s device when an advisory is updated. Travel advisories are discussed in Chapter 3.

Travel insurance

2.38 Under the Smartraveller campaign, DFAT encourages travellers to purchase comprehensive travel insurance to mitigate the financial costs that they may incur should they experience accident or injury overseas. The department does not offer its own travel insurance products, nor does it endorse products from a particular insurer. It does, however, try to assist travellers in selecting the most appropriate product for their needs. For example, in October 2014 DFAT undertook a joint initiative with the consumer group Choice to release a travel insurance buyer’s guide, which was published on the Smartraveller website, to assist consumers in this process. Additionally, DFAT is exploring options for collaborating with the Insurance Council of Australia, a member of the Smartraveller Consultative Group, to conduct research into the uptake of travel insurance among the Australian public.

Smartraveller campaign performance

2.39 The effectiveness of the Smartraveller campaign is intended to be measured through several metrics. In evaluating the effectiveness of the Phase II campaign, DFAT’s market researcher observed in March 2010 that the absence of overt targets for the campaign’s performance ‘means that it is not possible for us to say definitively whether the campaign was a success’. The research recommended that DFAT examine how key measures have changed over the course of the campaign, and in turn develop more specific, quantifiable objectives.

2.40 In response, Smartraveller Phase III outlined five metrics against which the success of the campaign would be measured.67 Notwithstanding the development of metrics for Phase III, DFAT is yet to develop specific and quantifiable targets for the overall Smartraveller campaign or for the metrics identified for Phase III. In the Smartraveller Phase IV communication strategy, DFAT has set out several specific, measureable metrics for assessing campaign performance, and committed to developing measurable targets for each, based on campaign objectives.

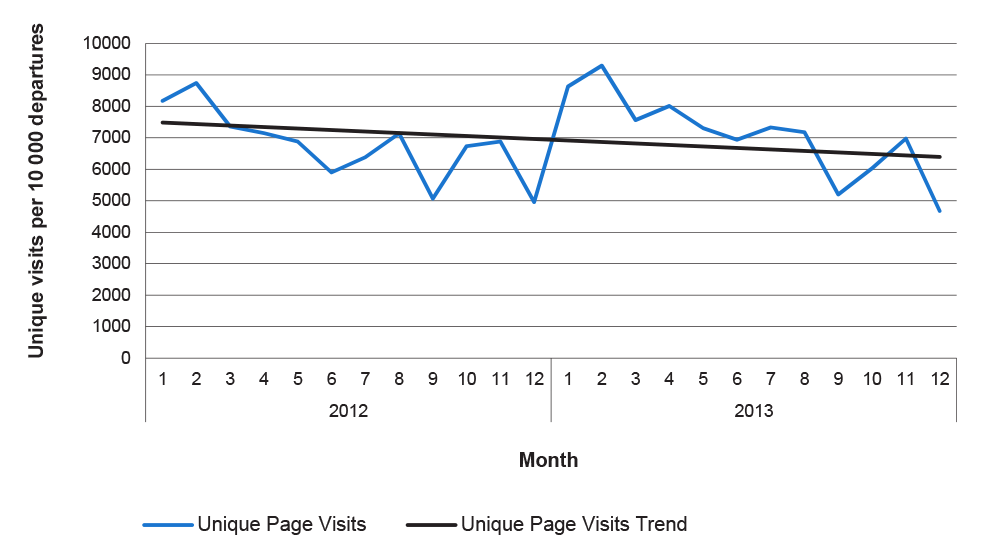

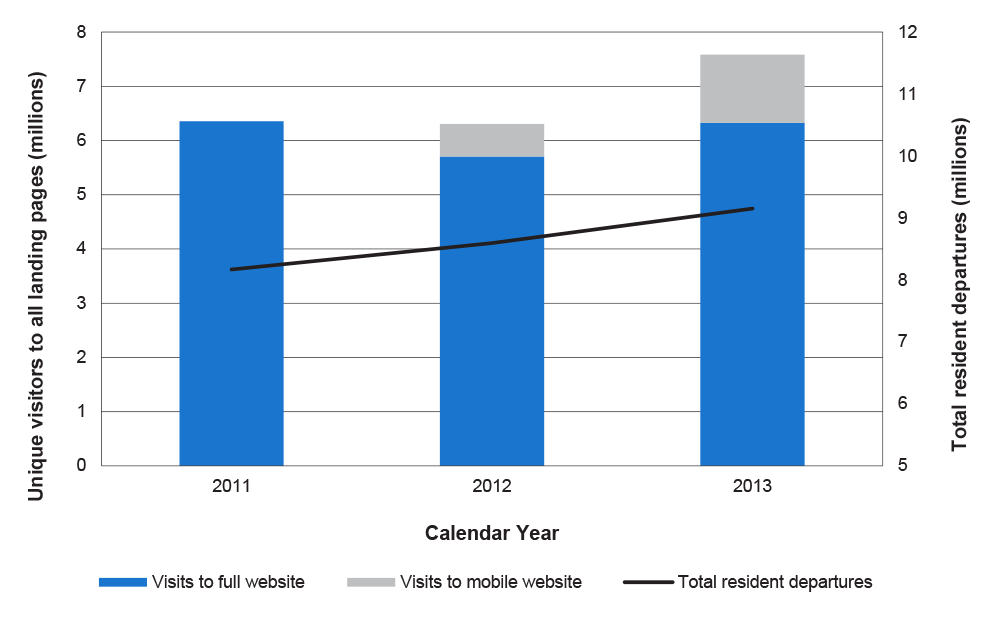

2.41 In the absence of reporting against the performance metrics for Phase III, the ANAO reviewed the performance of the Smartraveller campaign in terms of website traffic, subscriptions and registrations. The ANAO’s analysis indicated that awareness and use of the Smartraveller resources is increasing in absolute terms, but remained stable as a proportion of travellers because of increases in travel volume. The number of unique visitors to all Smartraveller website landing pages68 compared with total outbound passenger movements is shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4: Unique visitors to all Smartraveller Phase III

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT website data and overseas departures data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

2.42 DFAT has, however, been more successful in improving the uptake of its travel advisory subscription service. Subscribers as a proportion of travellers have been increasing since 2011, after experiencing two years of slight decline, as reflected in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5: Travel advisory subscriptions relative to travel departures

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT subscription statistics and overseas traveller departures data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

2.43 As DFAT is not able to determine the uptake of travel insurance among Australian travellers, it relies on anecdotal evidence from industry, as stated in DFAT’s 2012–13 annual report:

Anecdotal reports from industry sources indicate a subsequent increase in insurance take-up by Australian travellers.69

2.44 While the ANAO’s analysis and anecdotal evidence indicates the Smartraveller campaign has contributed to improved awareness and behavioural change, DFAT would be better placed to determine the extent to which campaign objectives have been achieved if it established and reported against relevant, reliable and complete performance indicators.

Overseas post communications

2.45 Overseas posts are responsible for managing communication with Australians resident in their accredited countries, and are often the first point of contact for travellers who experience difficulty while abroad. Communication methods and activities vary between posts and can include:

- websites that are separate from the DFAT central and Smartraveller websites, with local management responsible for their content and structure;

- social media accounts, which can include Facebook and/or Twitter, with the use of social media at the discretion of local management, under general guidance provided by DFAT officers in Canberra;

- email and contact lists, which can include lists of resident Australians that are used to distribute information; and

- material available and/or displayed at the post chancery70, including brochures, posters and other promotional material.

2.46 The ANAO examined how each of the above communications channels is used by posts to communicate with Australians abroad.

Websites

2.47 Each post is required to maintain a public website, which is to be used for public diplomacy purposes.71 While these websites are required to use a consistent graphical theme, which was established in the early 2000’s, decisions as to the content and structure of the website are the responsibility of local management. The overall design of post websites has not generally kept pace with contemporary trends in online activity—such as the increasing prominence of mobile browsing. Additionally, the functionality and content of post websites is variable, and often dependent upon the skills and availability of post staff. The ANAO examined a selection of six websites72 and noted differences in the consular content and information provided, as shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Consular content featured on six selected post websites

|

Selected Content |

Number of Post Websites Featuring Content |

|

Link to, or description of, consular privacy collection statement1 |

4 |

|

Link to, or list of, fees for notarial services |

2 |

|

Link to consular services charter |

4 |

|

Link to Smartraveller iPhone app |

1 |

Source: ANAO analysis of DFAT websites.

Note 1: The consular privacy collection statement outlines how DFAT collects, uses, discloses and stores personal information related to consular cases in accordance with the Privacy Act 1988.

2.48 While officers with website responsibilities are provided with training in the maintenance of websites, feedback from local management has indicated that the maintenance of post websites can be onerous. DFAT has advised the ANAO that shortcomings in the current post websites and the ongoing maintenance required are intended to be addressed as part of a broader replacement of DFAT’s web hosting platform with a contemporary solution. As part of this process, responsibility for static content, such as general information and policy documents, will be centralised in Canberra, while posts will retain ownership of dynamic content, such as local news updates and photos. DFAT expects that these changes, once complete, will provide an enhanced and consistent experience for the public, as well as reducing the administrative burden on posts. Replacement of post websites is expected to occur in tranches over the next year.

Social media

2.49 Social media accounts are used by posts to communicate consular related information, particularly information specific to the post’s location, such as latest travel advisories. Approximately half (48) of DFAT’s overseas posts use social media platforms to engage with the public, with each post managing the account and posted content. The majority of these posts used Facebook and/or Twitter, however, posts can seek approval to use other social media platforms, such as Flickr, YouTube, Sina Blog and Microblog (Weibo), and Youku, which may be more appropriate to the post’s local environment.

2.50 Coordination and oversight of posts’ social media presence is devolved to post management, although posts must present a business case to be granted approval to use social media accounts. DFAT’s policies regarding the use of social media accounts is limited to generic guidance, as found in DFAT’s conduct and ethics manual, in addition to that issued by the Australian Public Service Commission.73

2.51 DFAT has advised that it informally monitors social media content and usage by posts, and contacts post management directly to discuss issues of concern. While this approach allows posts the flexibility to focus social media communications on issues of local relevance, the ANAO identified risks in overall content and account credentials management.74 DFAT does not currently have in place a mandatory system for managing social media account credentials for those accounts established by posts. While staff are encouraged to register accounts using DFAT email addresses, this is not strictly enforced, and management of account credentials varies across posts.

2.52 Recognising these risks, DFAT has procured access to an online social media management platform and is trialling this platform over a two year period. The platform will enable central oversight of social media account credentials, account content, and evaluation tools that can identify types of content relevant to the public. As of October 2014 there were 32 post and three corporate accounts managed through the trialled platform, with an additional nine posts undergoing training in preparation for using the platform.75

Other post communications

2.53 Posts have developed a range of consular communication materials, including email and contact lists, and localised consular promotional materials. Posts develop these materials at their discretion, but are encouraged to do so where possible. The capacity of posts to develop these materials is dependent on the workload and resources of the post, the local security situation, and the number of Australians in the post’s accredited countries.

2.54 Posts have produced flyers, cards and other materials to inform Australians of the consular assistance and encourage Australians to register their contact details and/or subscribe to travel advice. Figure 2.6 shows an example where a post had developed, in partnership with partner nations, a single business card with each Embassy’s contact details to be distributed to police and prison authorities to be provided to detained nationals.

Figure 2.6: Example of post developed consular communications in partnership with partner nations

Source: Australian Embassy to the United Arab Emirates.

2.55 While the communication materials developed by each post are generally tailored to local conditions, there would be merit in CCD facilitating the sharing of locally developed communications concepts and ideas across its network of posts.

Conclusion