Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Delivery and Evaluation of Grant Programmes

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the selected entities:

- management of the delivery of projects awarded funding under four programmes where ANAO has previously audited the application assessment and selection processes; and

- development and implementation of evaluation strategies for each of those programmes.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Grants are commonly used by the Commonwealth to transfer funding to external parties for the purpose of achieving Australian Government policy objectives. The Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines establish the requirements and key principles under which entities undertake grants administration activities.

2. Over recent years, particularly in response to the nature of concerns raised by Parliamentary Committees and individual Parliamentarians in relation to specific programmes, the ANAO’s performance audits of individual grant programmes have increasingly focused on the processes by which grant funding have been awarded. Key issues raised by those audits have included funding decisions not being made in a manner, and on a basis, consistent with the published guidelines; poor quality assessment work; and shortcomings in the advice that was provided to Ministerial decision-makers.

3. To enable audits of the award of funding to be completed as quickly as possible, less attention has been given to the administration of approved grants, and programme evaluation activities. To balance the ANAO’s coverage across the lifecycle of grants administration activities, the objective of this cross-portfolio audit was to assess the effectiveness of selected department’s:

- management of the delivery of projects awarded funding under three programmes1 where the ANAO previously audited the award of grant funding; and

- development and implementation of evaluation strategies for each of those programmes.

Conclusion

4. Each audited department had in place a sound overarching framework through grant agreements to oversight the delivery of projects awarded grant funding. But it was common for there to be inadequacies in the administration of those agreements. This included delays in obtaining progress and other reports from funding recipients, as well as some reports not being obtained at all.

5. Delays in the delivery of projects were common across the three programmes. This situation resulted in the programme completion date being significantly delayed for two of the programmes. Nevertheless, reflecting that it was common for grant funding to be paid in advance of need, all funding had been paid by the nominated programme completion date even in respect to yet to be completed projects.

6. Of the three audited entities, only the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science planned and delivered timely and comprehensive programme evaluation work.

Supporting findings

Management of grant agreements

7. A sound overarching framework was in place through the grant agreements for each audited department to monitor project progress and completion. In each department, the administration of this framework was inadequate in a number of important respects. This included delays in obtaining reports and reports not being obtained at all. As a result, there were inadequacies in each department’s oversight of progress with, and completion of, the funded projects.

8. In this context, only the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme was delivered by its nominated completion date. There were considerable delays with the delivery of the other two programmes. The Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund is expected to take twice as long to be completed (six years rather than the three year original timeframe) and Liveable Cities has become a five year programme rather than the planned two year delivery timeframe.

9. Nevertheless, all grant funding has been paid out under each of the three programmes. For each programme, grant funds were paid significantly in advance of need. There was no demonstrable net benefit to the Commonwealth from the payment approaches. But there were some risks. In the circumstances, the ANAO’s analysis is that the approaches taken were inconsistent with the obligation under the financial framework to make proper (efficient, effective, economical and ethical) use of resources.

Programme evaluation

10. Two of the three audited entities had evaluation plans in place. Only the plan developed by the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science was comprehensive.2

11. Where evaluation activity was planned, it was undertaken. But entities gave less attention to acting on evaluation findings and recommendations.

12. Each programme had a broader aim than simply paying grant funding to deliver the approved projects. In particular, each programme was intended to influence the behaviour of entities other than grant recipients; for example, awarding funding for demonstration construction projects under both the Liveable Cities programme and the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund was intended to encourage other organisations to undertake similar projects. But each programme had limited success in demonstrably influencing the behaviour of entities other than the funding recipient.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.13 |

The ANAO recommends that entities:

|

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 2.40 |

To properly manage taxpayer’s funds, the ANAO recommends that, for project-based grants, entities clearly link payments to the cash flow required in order for the project to progress. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 3.15 |

To benefit fully from programme evaluation activities, the ANAO recommends that entities administering grant funding develop implementation plans to follow through on evaluation findings and recommendations. |

|

Recommendation No.4 Paragraph 3.28 |

The ANAO recommends that, when designing and implementing grant programmes that fund capacity building and/or demonstration projects, entities implement strategies that aim to influence the behaviour of entities other than the grant recipients, and measure the impact. |

Summary of entity responses

13. The Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development; the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science; and the Department of Social Services provided formal comment on the proposed audit report. The summary responses are provided below, with the full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science

14. The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science acknowledges the ANAO’s report on the Delivery and Evaluation of Grant Programmes and specifically, the audit of the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme.

15. The department welcomes the ANAO’s conclusions that the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme had a sound overarching framework in place; and that there was a comprehensive and timely evaluation of the programme.

16. The ANAO report does highlight delays in the delivery of milestones and suggests that payments were made in advance of need.

17. Although the report notes delay in delivery, it is important to recognise that the majority of milestones were submitted on time. The delays that occurred were between receipt of and finalisation (acceptance) of milestones. These delays were reflective of the complexities associated with information materials and the time and resource-poor nature of grant recipients. At all times, the department actively monitored milestones and worked with grant recipients to ensure best possible outcomes for projects. Importantly, all projects were delivered in advance of the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme closure date of 30 June 2015.

18. The ANAO report referenced the upfront payment of funds to grant recipients and recommended that payments be linked to cash flows. In deciding on upfront payments for Energy Efficiency Information Grants (up to 50 per cent), the department considered a number of factors. Some of these included the nature of programme recipients (that is, they were non-profit organisations that were cash and resource-poor) and the value of the grant. Based on these considerations, the department saw ‘net benefit’ to the Commonwealth by providing grant recipients with the funding that would enable them to prepare quality information and communication products in a timely manner. Following initial payment on execution of the funding agreements, payments were made on completion of milestones, as outlined in funding schedules.

19. The department continuously reviews programme design and delivery processes as part of the Digital Transformation Agenda and the establishment of the AusIndustry Business Grants Hub. This includes regular review of completed programmes through policy/programme partner interactions and the Departmental Program Assurance Committee to ensure policy and programme lessons are understood, shared with relevant parties, and formalised as necessary into procedures and policies. The experiences and lessons learned from the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme and from the ANAO audit will make a strong contribution to this process.

Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development

20. The Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development notes the ANAO’s recommendations in its report Delivery and Evaluation of Grant Programmes.

21. The department acknowledges the ANAO’s comments relating to the sound overarching framework in place through grant arrangements. The department also notes the ANAO’s findings on the department’s approach to the application of interest earned on advance payments to project proponents forming part of the Commonwealth funding contribution and the effective recovery of funds paid to proponents withdrawing from the programme. The department also acknowledges that the ANAO has cited that the department’s approach for subsequent programmes, such as the Bridges Renewal programme, has improved.

22. The department notes the ANAO’s findings concerning the timeframe taken to deliver projects under the programme. The timeframe for completion of projects was based on the advice of project proponents at the early stages of negotiations. The department has adopted an improved approach for subsequent infrastructure funding programmes managed by the department where grant payments are tied to the achievement of milestones.

23. Further, the department also notes the ANAO’s findings that an evaluation strategy was not undertaken for the project. While the department accepts the ANAO’s findings in relation to this matter, lessons from the Liveable Cities programme, including those from the first ANAO audit, have been incorporated in the design and management of existing, ongoing programmes. For example, under the Bridges Renewal programme, the department pays milestones based on the achievement of physical progress with projects, and makes final payment on receipt of post completion reports.

24. In terms of the ANAO’s finding in relation to the underspend within the programme, three of the 22 funded project proponents did not continue with their projects and chose to withdraw from the programme. It is important to note that in all cases the decision to discontinue projects were outside the control of the department.

Department of Social Services

25. The Department of Social Services acknowledges the findings of the report in relation to the delivery and evaluation of the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund and agrees with Recommendations one, two and three, and notes Recommendation four.

26. The department has recently undertaken significant reform in administering grants programmes with the introduction, in mid-2015, of the Programme Delivery Model (PDM). The PDM has been designed to comply with the Commonwealth Resource Management Framework and will be followed for the design, management and administration of all future departmental grant programmes, including capital works activities.

1. Background

1.1 Grants administration is an important activity for many Commonwealth entities, involving the payment of billions of dollars of public funds each year. The Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines outline that grants administration encompasses all processes involved in granting activities. This includes programme design, the grant selection process, the development and administration of grant agreements and programme evaluation activities.

1.2 Selecting grant applications that demonstrably satisfy well-constructed selection criteria is considerably more likely to lead to a positive result in terms of achieving programme objectives, as well as being more efficient for agencies to administer. The approach taken to administering approved grants is also instrumental to achieving value for money outcomes. Key elements include:

- putting in place grant agreements that provide an efficient and effective mechanism for identifying the outcomes expected to result from an approved grant, and the governance arrangements that apply;

- effective planning of the strategy to be used in paying approved funds to grant recipients. This helps entities to take relevant budgetary factors into account. It also promotes observance of the statutory obligation to make proper use of public money, including appropriate management of risks; and

- an ongoing monitoring regime to ensure grant recipients are meeting agreed milestones and other key requirements of their grant agreement.

1.3 The timely development and effective delivery of an evaluation strategy is also important to achieving planned programme outcomes.3 Evaluation can also help to identify opportunities to improve programme design and implementation approaches. The current version of the ANAO’s grants administration Better Practice Guide emphasises the importance of agencies having a strong early focus on establishing an evaluation strategy. It also outlines that the benefits of this work will be lost if agencies do not implement the evaluation strategy, or do not apply the results of the evaluation work.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.4 The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of selected department’s:

- management of the delivery of projects awarded funding under three programmes where the ANAO previously audited the award of grant funding; and

- development and implementation of evaluation strategies for each of those programmes.

1.5 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- management of grant agreements with successful applicants was sound; and

- an evaluation strategy was developed and implemented in a timely and effective way, with the results appropriately used.

1.6 The audit examined three grant programmes previously audited by the ANAO where the scope of the earlier audit was focused on the design of the programme and the grants selection processes.4 These were the:

- Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme, now administered by the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science;

- Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund, administered by the Department of Social Services; and

- Liveable Cities programme, administered by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development.

1.7 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $565 100.

2. Management of grant agreements

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the key terms of the grant agreements that were put in place, and whether each department effectively managed those agreements so as to achieve timely delivery of their respective programmes.

Conclusion

Each of the three audited programmes should have been delivered by no later than 30 June 2015. But delays in the delivery of approved projects were common across the three programmes. For two programmes, the Liveable Cities programme and the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund, those delays resulted in the programme completion date being significantly delayed. Nevertheless, as a result of entities paying grant funds in advance of project needs, all grant funding was paid out by the nominated programme completion date.

The approach adopted by the audited entities to project delivery delays varied considerably. The Department of Social Services and the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science applied resources to varying grant agreements to reflect the delays. But in 90 per cent of applicable projects, the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development took no such action in response to delays. Entity practices in disclosing the delays was also inconsistent, with only the Department of Social Services meeting the requirement to update its website reporting on grants to reflect the extended project durations.

A sound overarching framework was in place through the grant agreements for each audited department to monitor project progress and completion. But it was common for there to be inadequacies in each entity’s administration of the framework it had agreed with the funding recipients (as reflected in the signed grant agreement). This included delays in obtaining reports as well as some reports not being obtained at all.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has not made a recommendation relating to improved administration of grant agreement reporting arrangements. This is because entities simply need to pay greater attention to the range of guidance that is already available, including in the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines.

The ANAO has made two recommendations. The first relates to more realistic delivery timeframes being established at the programme level, as well as in the grant agreements that are signed for individual projects. The second seeks to encourage entities to pay grant funds in alignment with, rather than significantly in advance of, actual project needs.

Have the programmes been delivered?

The Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme was delivered by its nominated completion date. There were considerable delays with the delivery of the other two programmes. The Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund is expected to take twice as long to be completed (six years rather than the three year original timeframe) and Liveable Cities has become a five year programme rather than the planned two year delivery timeframe.

2.1 The three audited programmes were designed with delivery timeframes of two years (Liveable Cities), three years (Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund) and four years (Energy Efficiency Information Grants).

2.2 Advice to government on the design of those programmes had not identified the delivery timeframes as being unrealistic. However, only the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme was delivered in accordance with the planned timeframe (although there were still some delays). Specifically:

- all of the projects approved for funding proceeded to have a grant agreement signed; and

- each contracted project was delivered without any extension to the programme completion date (of 30 June 2015). This was possible by there being few delays with round two projects, and the frequent delays with round one projects were not significant enough to push them past the planned programme completion date.5

Liveable Cities programme

2.3 The Liveable Cities programme is providing 24 per cent less funding than was budgeted over a 150 per cent longer timeframe. The reduced funding reflects that a relatively high proportion of approved projects did not proceed (15 per cent). This involved the later reversal of funding approval, projects not proceeding to have a grant agreement signed or the agreement being terminated when the project did not proceed.

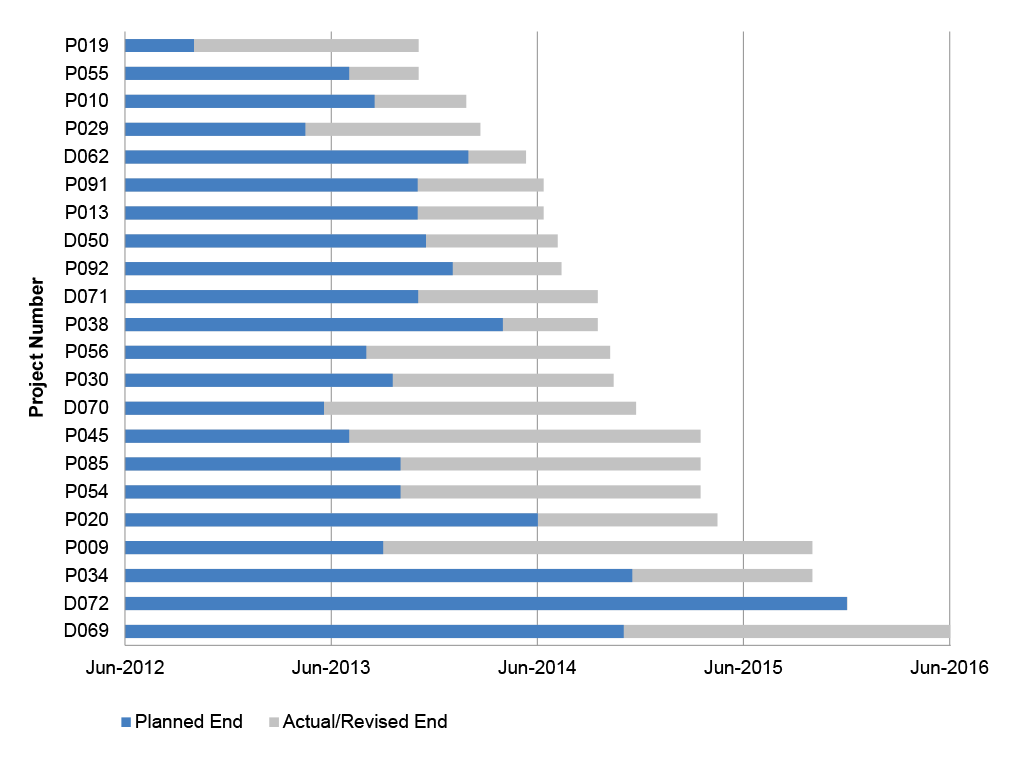

2.4 The longer timeframe for the delivery of the programme reflected two factors. Firstly, the funding agreement negotiation and signing process took considerably longer than expected. Secondly, and more significantly, as illustrated by Figure 2.1, major delays in the delivery of projects have been common. This was the case notwithstanding that the department’s assessment of applications involved it being satisfied that each of the successful projects was ‘ready to proceed’ and would be completed by the planned programme completion date of 30 June 2013.

2.5 As it eventuated, only three projects were contracted to be completed by 30 June 2013.6 Further, only two of the 22 projects were delivered in accordance with their originally contracted timeframe. One of those projects had been completed on schedule but the department did not close it out for another 12 months. The delays in the remaining 20 projects being completed ranged from three months to more than two years (with an average delay of nearly 12 months). The various delays have seen the programme move from a two year delivery timeframe when applications were sought, to a four year timeframe for most projects, and five years for four of the projects.

Figure 2.1: Scheduled and actual/revised Liveable Cities programme project durations

Source: ANAO analysis of Liveable Cities programme grant agreements and project closure records.

Delivery of accommodation for disabled persons

2.6 All but one of the 27 approved Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund projects has proceeded.

2.7 The programme eligibility requirements included that projects would be ready for residents to occupy (or have a certificate of occupancy issued) by 30 June 2014. Each of the approved applications had been assessed by the Department of Social Services as meeting that eligibility requirement. In addition, the merit assessment process included a criterion related to the applicant’s ability to manage the construction of supported accommodation. Each of the approved applications had been scored highly by the department against that criterion.

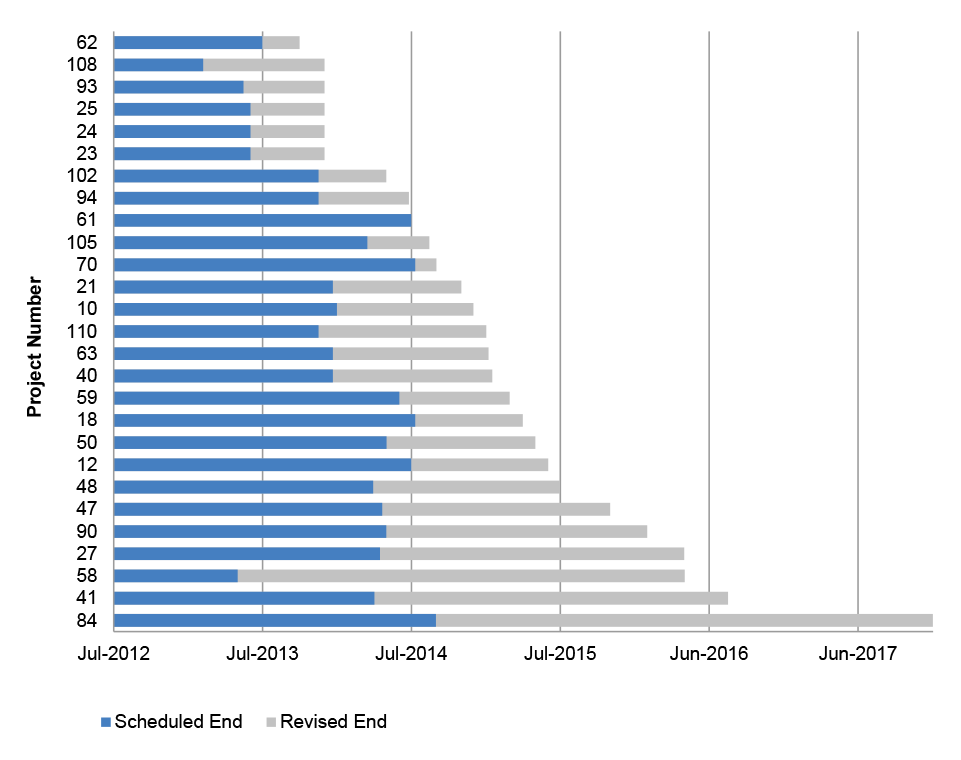

2.8 Delays with project delivery have been common. By 30 June 2014 five projects had not even commenced construction. At this time, two-thirds (18 of 27 projects) had contracted timeframes for completion beyond 30 June 2014, as far out as late 2017 (see Figure 2.2). As of December 2015, when ANAO audit activity was completed, one project had been terminated and four projects had still not been completed.

Figure 2.2: Scheduled and revised Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund project activity durations

Note: Project 48 was terminated in mid-2014.

Source: ANAO analysis of Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund funding agreements and variations.

Grant agreement variations

2.9 Agency performance has been quite mixed in terms of amending grant agreements to reflect project delivery delays. At one extreme, notwithstanding that delays in delivery of Liveable Cities programme projects were common; only two grant agreement variations were executed by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development. Rather, in 90 per cent of applicable projects, no action to vary the agreement was taken in response to delays. For 17 projects, the activity end dates set out in the grant agreements expired before the projects were completed.

2.10 By way of comparison, the Department of Social Services and the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science processed a significant number of variations to reflect delays in the delivery of funded projects. Specifically, for the:

- Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund, by mid-2015 some 92 funding agreement variations had been processed. This represented an average of more than three variations per project. Of these 92 variations, 12 were made late (up to nine months after the activity end date had expired). Each project had at least one variation, and as many as five variations7;and

- Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme, 81 variations were executed (an average of nearly two variations per project). For 11 projects the activity end date set out in the funding agreement expired before the project was due to be completed (that is, the end dates were not varied).8 This situation exacerbated the insufficient attention to detail that was evident in the drafting and execution of some of the original funding agreements. Specifically, for 11 projects the activity end date specified in the original agreement was due to expire before the final milestone scheduled in the agreement.

2.11 Since December 2007, website reporting by entities of individual grants and their key terms has been in place as a measure to promote transparency and accountability. One aspect of the website reporting requirement is that grant agreement durations be amended where there has been a significant variation. With the exception of one project, this requirement was adhered to by the Department of Social Services for the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund. However, delays with projects funded under the other two audited programmes were not reflected in the website reporting by the relevant administering department.

2.12 In addition to requiring updates to the website reporting of key grant terms, managing multiple and frequent funding agreement variations is not an efficient and effective use of limited departmental and grant recipient resources. Adopting more realistic programme timeframes and project milestones when negotiating funding agreements can assist in minimising the need for variations. It is also important that advice to government on delivery timeframes for future grant programmes be more realistic.

Recommendation No.1

2.13 The ANAO recommends that entities:

- provide more realistic advice to Ministers on programme delivery timeframes when new grant programmes are being designed; and

- when developing and administering grant agreements, pay greater attention to adopting realistic project delivery timeframes and actively managing any delays.

Entity responses:

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science

2.14 Part (a) – Agreed, noting that the department delivered the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme in advance of the programme closure date of 30 June 2015. Realistic programme delivery timeframes will remain a key design element of future programmes.

2.15 Part (b) – Agreed. In the case of the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme, slippage of milestones reflected the complex nature of funded projects and the internal resource constraints of grant recipients. In all instances, the department actively worked with grant recipients to manage slippage of milestones and delivery timeframes. As a result, all projects were completed before the programme closure date.

Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development

2.16 Agreed with Qualification. The programme delivery timeframes were based on funding profiles that were too optimistic. This in turn influenced how payment schedules were tied to project delivery timeframes. In setting funding profiles, more recognition needs to be given to timeframes needed for establishing and implementing new programmes. The department notes that the ANAO was critical of longer time frames in establishing the Bridges Renewal programme.

Department of Social Services

2.17 Agreed. The department’s Programme Delivery Model, introduced in mid-2015, provides clear guidance, supporting tools and references to assist staff in administering grants programmes which will assist in the development of realistic timeframes for advice to Ministers.

2.18 The department’s Programme Delivery Model includes guidance for staff on managing all aspects of grant agreements, including managing risks and issues. This includes a range of project management and project planning tools and guidance as well as comprehensive Activity Design Risk and Provider Capacity Risk Assessments.

2.19 The Programme Delivery Model is the single source of guidance and resources for staff monitoring funded organisations’ performance, including those related to delivery timeframes, and resources are tailored to individual service delivery models. This ensures consistency across the department for all programme deliverables.

2.20 Implementation of the Programme Delivery Model addresses the concerns raised under this recommendation.

Have entities efficiently and effectively oversighted progress with, and completion of, the funded projects?

A sound overarching framework was in place through the grant agreements for each audited department to monitor project progress and completion. In each department, the administration of this framework was inadequate in a number of important respects. This included delays in obtaining reports and reports not being obtained at all. As a result, there were inadequacies in each department’s oversight of progress with, and completion of, the funded projects.

2.21 The grant agreements that were in place for each of the three programmes provided a sound overarching framework for the relevant department to oversight the delivery of the approved projects by the funding recipient that was proportional to the complexity of the programme and the risks involved. Two of the programmes required reporting from the funding recipient when specified project milestones had been met, with one also requiring a progress report in months when no milestone was due. The third entity required quarterly performance reports.9

2.22 The required content of the reports was appropriate for the Liveable Cities programme, but deficient for both the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund and the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme, as follows:

- for the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund, the Department of Social Services did not require reporting on the funding received to date; any funds that had been contributed by project partners towards project costs10; or the extent to which construction activity had been undertaken; and

- a notable absence from the project reporting arrangements for the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme given the payment of funds in advance of need was any requirement for timely reporting on the receipt and expenditure of project funds. The funding agreements required only annual reporting of this information as part of the grant acquittals process.

2.23 Each of the three departments performed poorly in terms of obtaining timely reports. For example:

- 72 per cent of the milestone reports required for Liveable Cities projects were submitted late. Performance was generally better in respect to the department obtaining progress reports in months when a milestone was not scheduled, but there were some significant exceptions. For instance, the recipient of a $3.75 million grant for one of the demonstration projects stopped providing monthly reports in mid-2014 after it received its final payment (notwithstanding that the project being funded by the grant is not expected to be completed until June 2016);

- over 68 per cent of required milestone reports for the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme that were of an acceptable standard to the department were submitted late;

- the Department of Social Services did not send reminders or actively seek quarterly reports unless a payment was due. To enable programme payments to nevertheless be made, by early 2013, the department had effectively abandoned its intended approach of payments being made only where satisfactory progress of the project had been demonstrated. It was also commonplace for the department to not seek reports after the final payment for a project had been made notwithstanding that the project had not yet been delivered. The result, as illustrated in Table 2.1, was that many reports were either not provided or were submitted late.

Table 2.1: Summary of findings on submission of Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund quarterly reports to the Department of Social Services

|

Grant |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

Q5 |

Q6 |

Q7 |

Q8 |

Q9 |

Q10 |

Q11 |

Q12 |

Q13 |

|

10 |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

OT |

L |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

12 |

OT |

L |

OT |

L |

L |

L |

L |

L |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

18 |

OT |

L |

L |

OT |

L |

OT |

OT |

L |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

|

21 |

OT |

L |

OT |

OT |

L |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

23 |

OT |

L |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

24 |

OT |

L |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

25 |

OT |

L |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

27 |

OT |

L |

OT |

NR |

NR |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

|

40 |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

41 |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

OT |

NR |

L |

NR |

NR |

|

47 |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

L |

L |

OT |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

48 |

OT |

NR |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

Project terminated |

||||

|

50 |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

|

58 |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

|

59 |

NR |

L |

L |

OT |

L |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

|

61 |

L |

NR |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

62 |

OT |

NR |

NR |

OT |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

63 |

L |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

70 |

L |

NR |

L |

L |

NR |

L |

L |

L |

OT |

NR |

OT |

n/a |

n/a |

|

84 |

L |

NR |

L |

OT |

L |

OT |

NR |

NR |

L |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

|

90 |

NR |

L |

OT |

OT |

L |

L |

NR |

NR |

L |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

|

93 |

L |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

94 |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

|

102 |

OT |

L |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

|

105 |

L |

OT |

L |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

|

108 |

L |

OT |

NR |

NR |

NR |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

110 |

OT |

L |

OT |

OT |

OT |

NR |

OT |

OT |

OT |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Key: OT (Green shading) – received on time or less than one week late. L (Orange shading) – received late. NR (Red shading) – not received. n/a (grey shading) – not applicable.

Source: ANAO analysis of quarterly reports received by the Department of Social Services.

2.24 Shortcomings were also evident in the extent to which the Department of Social Services made use of the data that was reported. In particular, the department did not collate quarterly reports or track reported actual expenditure. Had it undertaken this analysis, it would have identified errors in reporting such as the content not being updated from the previous report and errors in the reported expenditure.

How well was the payment of grant funding linked to project delivery?

For each of the three programmes, grant funds were paid significantly in advance of need. There was no demonstrable net benefit to the Commonwealth from the payment approaches. But there were some risks. In the circumstances, the ANAO’s analysis is that the approaches taken were inconsistent with the obligation under the financial framework to make proper (efficient, effective, economical and ethical) use of resources.

2.25 As outlined in the ANAO’s grants administration Better Practice Guide, for project-based grants, value for money and sound risk management are promoted by funds becoming payable only upon the demonstrated completion of work that represents a milestone defined in the signed agreement. That is, if project work is not completed satisfactorily, no further funds should be forthcoming. The timing and amount of each payment also needs to appropriately reflect the:

- cash flow required in order to progress the project, including consideration of whether funding contributions required from the proponent and other sources are being applied to the project at the same proportional rate as the Australian Government contribution;

- risk of non-performance of obligations, or non-compliance with the terms of the agreement. In particular, the Australian Government’s capacity to influence project delivery can be expected to diminish once funds have been substantially paid; and

- cost to the Australian Government, through interest foregone, of payment of funds earlier than needed to achieve programme objectives.

2.26 For each audited programme, payments were contracted to be paid in advance of project needs. This included, under some agreements, a significant proportion of the funds being paid upfront without there being a demonstrated net benefit to the Commonwealth from doing so.11 It was also evident that two departments (the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development and the Department of Social Services) had made payments subsequent to the first instalment in circumstances where they should not have done so. This allowed both departments to pay all grant funding by the nominated programme completion date, notwithstanding that a significant proportion of projects were not expected to be completed for some considerable time after that date. The payment approaches adopted by each of the three departments were inconsistent with the obligation under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 to make proper (efficient, effective, economical and ethical) use of resources. A practice of paying funds out by the nominated programme completion date notwithstanding delivery delays can also avoid accountability for those delays.

2.27 The Department of Social Services adopted a two-fold approach to increasing grant payments above those that were warranted. ‘Progress’ payments under the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund were made in circumstances where it was evident from quarterly reports submitted by grantees that further payments were not needed to progress the project. The department also adopted a practice of making significant payments immediately prior to the end of a financial year (that is, in June 2012, June 2013 and June 2014). To maximise programme expenditure, payments were made even in circumstances when preceding milestones had not been met or were overdue, or when the department held inadequate evidence to support that a milestone had been met. This approach was taken notwithstanding that obtaining documentary evidence supporting the achievement of milestones was a requirement of the grant agreements.

2.28 As a result, a number of grantees reported holding significant amounts of unexpended grant funding as at the 30 June 2014 planned programme end-date. For example, six grantees reported holding a total of $20.8 million (39 per cent of total programme payments) as at that date. The amounts involved ranged between 69 per cent and 99 per cent of the total each of these six grantees had been paid to that date.

2.29 In an attempt to manage the risk to the Commonwealth over the security of these funds, across 11 projects the department attempted to use bank guarantees to secure payments made in advance. However, 94 per cent of the bank guarantees were obtained after the payment had been made.12 The bank guarantees obtained also provided less protection for the Commonwealth than the grant payments that had been made, as the amounts required by the department to be guaranteed did not include the equivalent of the GST component included in the payments. In addition, the ANAO’s analysis was that the department’s approach to recording the receipt and discharge of those bank guarantees was inadequate in a number of respects.

2.30 There was also an illogical inconsistency in the department’s approach to the financial implications for grantees of the advance payments and associated bank guarantees. Specifically:

- there was a financial benefit to the grantee in terms of being able to earn interest on the funds. But the Department of Social Services did not require interest on grant funds to be acquitted. This has been required in other grant programmes audited by the ANAO.13 Further, where grantees voluntarily reported interest earned on grant funding, the department did not take these amounts into consideration for acquittal purposes. Rather, it advised grantees that they did not need to report or acquit the interest received; and

- conversely, the department accepted the costs of establishing and maintaining the bank guarantees as being eligible to be included in the acquittals as a legitimate use of grant funds.

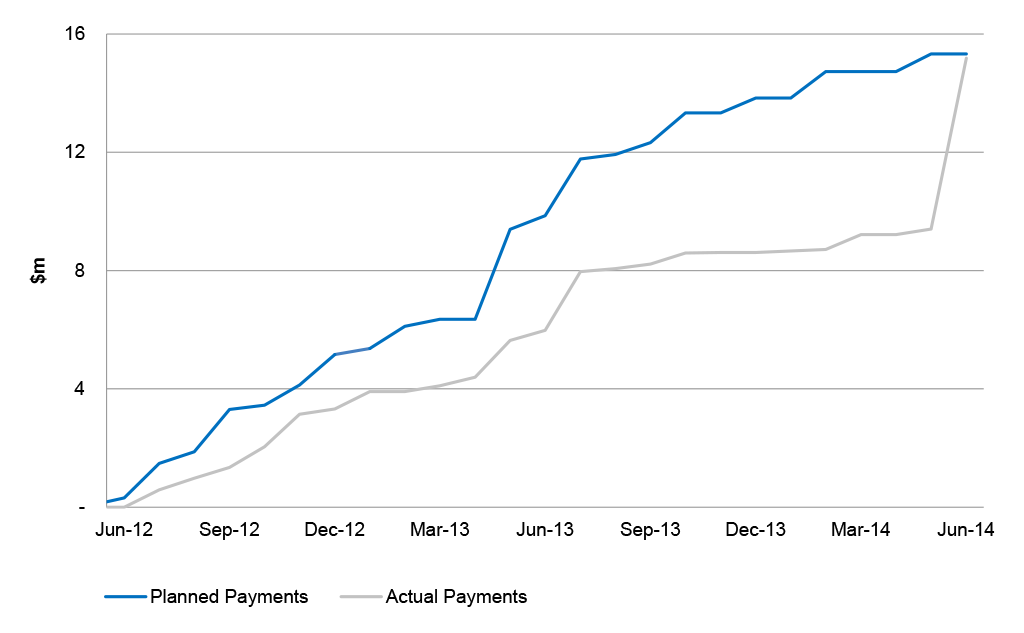

2.31 The most notable feature of the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development’s approach to ensuring the Liveable Cities programme was fully paid out by its planned completion date of 30 June 2014 involved a significant increase in payments in June 2014 (see Figure 2.3). Only five of the 22 projects that proceeded (23 per cent) had been completed by that date. In some cases, to ensure payments could be made before 30 June 2014 notwithstanding delays with project delivery, the department amended the relevant grant agreement to reduce the extent to which the project was required to have progressed before funds were payable.

Figure 2.3: Planned and actual Liveable Cities programme project expenditure

Source: ANAO analysis of Liveable Cities programme grant agreements and payment records.

2.32 The ANAO’s current audit of the Bridges Renewal Programme indicates that the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development is adopting an improved funding strategy. For the Bridges Renewal Programme, notwithstanding the potential pressure associated with having a $60 million appropriation and only four months remaining in 2014–15 at the time funding negotiations commenced, the department did not attempt to maximise programme expenditure by making advance payments. Instead, a lower-risk strategy was adopted with each of the payments set out in the agreed milestone schedules being linked to the satisfactory delivery of activities. These were commonly construction activities, with final payments made subject to completion of the project and delivery of a post-completion report.

2.33 The Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme was the only programme in which the final payment scheduled in the funding agreement was contingent upon the receipt and acceptance by the department of the final project report and acquittal. These final payments were most commonly 10 per cent but ranged from one per cent to 15 per cent of grant funding.

Recovery of overpayments

2.34 Not surprisingly given payments were made in advance of project needs under each programme, recovery of grant funds was required for each of the three audited programmes. The extent of recoveries, and the timeliness and completeness of recovery action, varied considerably.

2.35 The total amount required to be recovered was relatively small for the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme. In a total of 18 instances, the funded project was completed at a lower cost than had been budgeted. In two of these instances, this required a recovery of payments that had been made. The amount was small for one grant ($24 080 plus GST) but comprised the majority of the funding (approximately 84 per cent) in respect to another grant of $528 250 plus GST. Specifically, in addition to not making the final scheduled payment of $52 825 plus GST, some $452 914 (plus GST and including interest14) of the total funding awarded needed to be recovered after the proponent advised that it and its partner organisation had performed more in-house work on the project than originally expected (which reduced the need to engage external contractors). The need to recover such significant amounts of Commonwealth funding would have been obviated if the department had adopted a payment regime that reflected project cashflow needs (for example, payments based on the actual project expenditure incurred as at each milestone reporting date and expected to be incurred by the next scheduled milestone).

2.36 A single large recovery was required for the Liveable Cities programme. The amount involved was $1 million, of a total $3.75 million grant. The $1 million had been paid in April 2013 following the signing of the grant agreement but the agreement was terminated in July 2013 after the proponent decided not to proceed with the project. The Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development recovered the amount paid plus interest.

2.37 The Department of Social Services’ approach for the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund was inadequate. In the two months between 9 April and 13 June 2013, the proponent for one of the approved projects received three payments of $880 000 each. These payments were made notwithstanding the proponent not meeting the requirements of the first milestone (being the appointment of a building contractor). Further payments totalling $536 822 were then made in September 2013, May 2014 and June 2014. Those payments were made notwithstanding that the grantee had still not signed a building contract.

2.38 In July 2014, some three weeks after the final payment had been made by the department, the grantee terminated the project. Following a considerable delay (of some seven months), in February 2015 the grant agreement was terminated and the department commenced recovery action for $2 million of the unspent grant funds. In assessing the amount to be recovered, the department permitted the grantee to consider that all payments that it may make to the builder could be met from the grant funds, notwithstanding that the programme was funding only six units of a 34 unit overall project being undertaken by the grant recipient and no contract had been executed with the builder when the project was terminated.

2.39 In December 2015, after the ANAO had raised concerns in October 2015 that the department should be seeking to recover a greater amount, the department advised that recovery of a further $300 000 was in process. The amounts the department has sought to recover do not include any interest. Further, in determining the amount that remains to be recovered, it is not clear that the department has assured itself that the total funds reported as spent on the project have been correctly apportioned between the six units that were to be constructed under the programme-funded component and the remaining 28 units (representing 83 per cent of total project costs) that were to be separately funded by the grant recipient.

Recommendation No.2

2.40 To properly manage taxpayer’s funds, the ANAO recommends that, for project-based grants, entities clearly link payments to the cash flow required in order for the project to progress.

Entity responses:

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science

2.41 Partially agreed. Determination of payment arrangements should be based on consideration of the nature of projects, the capacity of the recipient, risk profile and the policy intent of the programme. Ensuring value for money, informed by risk assessment, will remain a key consideration for the department.

Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development

2.42 Agreed. While some payments were made on signing of agreements and before proponent contributions, the department acknowledges that payments, at the time, were guided by existing allocations. Since that time, the department has improved its payment approach for infrastructure funding programmes through the linking of milestone payments to the achievement of physical progress with projects. This includes linking final milestone payments to project completion.

Department of Social Services

2.43 Agreed. All stages of the grant activity lifecycle are covered by the department’s Programme Delivery Model, including the development of grant agreements and setting of payment milestones.

2.44 The establishment of payment milestones for new grants is informed by the outcome of a grant recipient capacity risk assessment. For example, a grant recipient with a higher risk rating will be subject to smaller, more frequent payments. This process ensures payments are made to progress projects while at the same time protecting the Commonwealth from risk.

2.45 The department will investigate opportunities, using the Programme Delivery Model, to provide further guidance and instruction to staff on the setting of frequency of payment milestones for new grants, with particular attention to project-based and capital support agreements. This could include linking milestone payments to deliverables during the period of the agreement, rather than determining payment frequency in advance, noting that determining cash flow requirements would introduce a level of complexity that would increase regulation for funded organisations.

Have previously identified errors in grant reporting been corrected?

At the time of the audit, errors in website reporting by the Department of Social Services of grant funding locations remained. This was the case notwithstanding that the department had previously accepted, and purportedly implemented, an ANAO recommendation that it correct its website reporting approach.

2.46 Analysis of grants data reported by entities on their website has, on a number of occasions, led Parliamentarians to request the ANAO to audit the award of funding under a particular grant programme. One such request related to the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund because of concerns raised by a Member of Parliament that the electorate distribution of approved funding appeared to be particularly favourable to the Australian Labor Party, which was at the time in Government, and the Australian Greens.

2.47 The ANAO concluded that this perception arose due to errors in the department’s website reporting on the locations in which funding was being provided. Specifically, the department reported the location of funding according to where the project proponent was located, rather than where the accommodation was to be constructed or purchased. Correcting for the department’s errors, the ANAO concluded that, although accommodation located in electorates held by the Australian Labor Party were awarded the majority of programme funding, the situation was not as stark as was suggested by the department’s website reporting. The ANAO further concluded that no funding had been awarded for accommodation in the only electorate (Melbourne) held by the Australian Greens.

2.48 The department agreed to a recommendation from the ANAO in the 2013 audit report that it adjust its website reporting to comply with the requirements of the grants administration framework. Further, the department’s response to the 2013 audit report stated that it was addressing the issue both by correcting the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund reporting but also with broader system changes to prevent recurrence in other programmes, with the broader system changes said to be ‘in train’.

2.49 In this current audit, the ANAO examined whether the errors previously reported in respect to the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund funding had been corrected. The department’s more recent audit committee records do not identify Recommendation 3 from ANAO Audit Report No. 41 2012–13 as being outstanding. The department advised the ANAO that it considered it had implemented the recommendation, but it was unable to provide the ANAO with any records of when it closed Recommendation 3 as having been implemented, or the rationale.

2.50 In contrast to the department’s perspective that the recommendation had been implemented, the ANAO’s work revealed that the website reporting errors that led to the 2013 audit remained. Specifically, the grant location being reported by the department in discharging its website reporting obligations continued to be where the project proponent was located, rather than the address of the supported accommodation places. For example, at the time of audit fieldwork the Department of Social Services still reported the grant awarded to Life Without Barriers for the Alice Springs Respite Centre project as having a grant funding location of Newcastle in NSW (which is the location of the proponent’s national office).

2.51 In early December 2015, the department advised the ANAO that:

The Programme Office is reviewing the Department’s method for extracting and publishing grants to meet the Department of Finance obligations as specified in the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines [sic]. In particular, DSS is reviewing how to improve information provided about service locations. Any changes to DSS methodology will be made before the end of financial year.

2.52 The department subsequently advised the ANAO in mid-December 2015 that the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund grants listed on its website have been amended and now provide the correct grant funding locations.

3. Programme evaluation

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether each department developed and implemented a programme evaluation strategy in a timely and effective way, and the results of any evaluation work. As each of the three grant programmes was intended to influence the behaviour of entities other than grant recipients, the ANAO also examined whether the desired broader impact had been achieved.

Conclusion

There were considerable inconsistencies in the extent to which the audited entities evaluated their programme delivery performance, and the results achieved from the grant funding. Of the three audited entities, only the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science planned and delivered timely and comprehensive programme evaluation work. Of particular value was benchmarking research commissioned by the department. This research provided insights into the impact of the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme on its target population.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has not made a recommendation relating to agencies planning and undertaking programme evaluation activity. Sufficient guidance in this regard is already provided by the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines.

The ANAO has made two recommendations. The first relates to entities acting on the results of their evaluation work. The second is that entities pay greater attention to the dissemination and transferability of benefits from funded projects that are intended to have not only direct benefits for the funding recipient but have broader impacts (such as demonstration benefits).

Was there a strong early focus on programme evaluation evident?

Two of the three audited entities (being the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science and the Department of Social Services) had evaluation plans in place. Only the plan developed by the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science was comprehensive.

In the context of the ANAO’s earlier audit on the award of Liveable Cities funding, the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development had advised the ANAO in May 2013 that it was finalising an evaluation strategy to capture key outcomes in line with project and programme objectives. However, although some work was undertaken towards planning evaluation activity the plan was not finalised and no evaluation work was or is now planned to be undertaken.

3.1 An outcomes orientation is one of the key principles for grants administration included in the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines. It is recognised better practice15 for entities to adopt an early focus on evaluation by developing an evaluation strategy. A sound strategy identifies the objectives against which performance is to be evaluated, together with performance indicators for each objective. It also identifies the data sources intended to be used and methods of analysis expected to be applied. The planned evaluation activity should be appropriate, fit for purpose and proportional to the relative size and scale of the programme.

3.2 There was significant variation in the extent to which the three audited entities demonstrated a commitment to programme evaluation. Only the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, in respect to the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme, planned a timely and thorough evaluation approach. The first version of its Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Plan was prepared in May 2012, at around the same time that round one funding decisions were made. The Plan was updated in September 2012 for round two of the programme and again in October 2012, July 2014 and March 2015.

3.3 The Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Plan was comprehensive. It outlined that evaluation work would be undertaken at both individual project level, and for the programme overall. The approach was to draw on a range of information. This comprised:

- information provided by grant recipients in progress reports, milestone reports and final reports for each project;

- the department’s own records on the delivery of the programme; and

- benchmarking research commissioned by the department to measure outcomes.

3.4 The Department of Social Services also developed a plan to evaluate the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund. The plan was initiated relatively early in the development of the programme, with a two-phase evaluation approach finalised in October 2011, the month after applications opened. The strategy focused on the first phase and left most of the details of the second phase to be fleshed out when it was expected to be commenced in mid-2014.16

3.5 The Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development did not undertake an evaluation of the Liveable Cities programme. In the context of the ANAO’s earlier audit on the award of Liveable Cities funding, the department had advised in May 2013 that it was finalising an evaluation strategy to capture key outcomes in line with project and programme objectives.17 Although some work was undertaken to develop a draft evaluation plan, this was not completed and the plan was not finalised. In November 2015, the department advised the ANAO that:

There was no formal DIRD requirement for an evaluation plan for the Liveable Cities Programme. As discussed, there were no additional funds allocated to the development of evaluation plans or reports. DIRD can confirm that there are no final evaluation plans or reports.

3.6 In addition to not planning or undertaking an evaluation of the programme, the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development’s approach to finalising individual funded projects focused on whether the funded projects had been completed, and gave insufficient attention to whether any broader benefits have been realised. The final reports submitted to the department by funding recipients revealed:

- instances where funding recipients had not provided the data related to the outcomes that had been achieved, even where the application for grant funding had specifically identified that such data would be collected;

- that for a number of the design and planning projects, implementation activities were underway or were expected to occur; but

- in contrast, there was no evidence of either the funding recipients or the department seeking to disseminate the benefits and lessons learned from those construction demonstration projects that have been completed.

Has the planned evaluation work been undertaken and used?

Where evaluation activity was planned, it was undertaken. Entities gave less attention to acting on evaluation findings and recommendations.

Energy efficiency information for community organisations and small and medium size business enterprises

3.7 As planned, the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science adopted a multi-faceted approach to its evaluation of the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme. Of particular note was that:

- funding recipients were required to carry out an evaluation of their project, and to report their findings to the department. Specifically, for each signed funding agreement, one of the early milestones required the funding recipient to submit a draft risk and evaluation plan for departmental consideration. The department supported this process by developing an evaluation information pack for successful applicants as well as by reviewing and providing feedback on each project’s draft evaluation plan; and

- a market research consultant was contracted to conduct pre- and post-surveys of businesses and community organisations potentially exposed to the funded activity. The intention was to establish a baseline and then measure changes in awareness, attitudes and behaviour over the two to three year period of funded activities.

3.8 The benchmarking research provided was well informed by responses and, as a result, delivered useful insights into the impact of the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme on its target population. In particular, it was identified that the programme had been a success in relation to its primary goals around provision of information as well as targeted organisations’ perceived access to information and advice and being better informed. For example:

- organisations were more likely to feel well-informed. Specifically, there was an increase of 11 percentage points in the percentage of well-informed organisations, with a further eight to nine percentage points for those participating in the programme. This was considered to be a good outcome against one of the key goals of the programme;

- there was an increased proportion of businesses and community organisations aware of other organisations that had successfully taken steps to become more energy efficient or make smarter decisions on their energy use. There was a general increase over the course of the programme from 56 per cent to 65 per cent, with programme participants higher at 73 per cent. This demonstration benefit was assessed as a significant outcome ‘as knowing other organisations taking relevant and effective steps encourages and inspires actions in others’ with the research concluding that ‘many of the Energy Efficiency Information Grants projects were appreciative of this dynamic and facilitated a ripple effect’; and

- there were significantly fewer organisations that perceived barriers to taking action to reduce their energy use at the end of the programme compared to at its commencement.

3.9 However, the department’s public reporting on the performance of the programme did not draw on the outcomes and performance measures included in its Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Plan. In addition, the department’s public performance reporting on programme performance would have benefited from drawing on the results of the benchmarking research. Rather than reflecting the insights that had been gained, performance reporting in the department’s 2014–15 Annual Report stated the amount paid and number of funding recipients and claimed that:

The programme resulted in energy efficiency information being provided to around 650 000 small and medium businesses and community organisations. This information will help businesses and community organisations make better choices about energy use and reduce their energy costs.

3.10 The figure of 650 000 organisations receiving information was not supported by information reported by funding recipients (and the department was not otherwise able to provide the ANAO with adequate support for the reported figure).18

Disabled persons’ supported accommodation

3.11 As planned, evaluation work was undertaken in two stages, but the scope of the first phase was reduced compared with what had been planned. Specifically, in September 2012, the Department of Social Services reduced the scope of Phase 1. It described the reduced scope Phase 1 as ‘a rudimentary analysis of the outcomes of the selection process’. As implemented, Phase 1 was more akin to a post-implementation review. It involved departmental staff involved with the management of the programme reviewing the development and implementation of the programme up to the stage where capital works grant agreements had been executed.

3.12 In late 2012, a 34 page ‘Post Implementation Review’ report was produced. The report made eight recommendations. By mid-April 2013, the review was still ‘currently being finalised’. Departmental records also did not identify whether the recommendations had been accepted or not, or include an implementation plan. The ANAO sought advice from the department on these matters, with the department responding that one of the recommendations had been implemented.

3.13 Phase 2 of the evaluation was planned to be conducted once the funded projects had been delivered. This phase of the evaluation proceeded after the nominal programme completion date had passed. But project delays meant that the evaluation work was unable to be informed by analysis of a substantially or fully completed programme.

3.14 The contracted consultants provided their report in early 2015. The report concluded that most objectives and most performance indicators had been met in full or part. It nevertheless made 19 recommendations. Similar to the Phase 1 report, programme records did not indicate whether those recommendations had been accepted and, if so, what implementation action has occurred. Advice to the ANAO from the department was that all findings were accepted and were used to inform the development of a new funding programme for disability accommodation (the Specialist Disability Accommodation Initiative). More broadly, the Department of Social Services advised the ANAO that it is:

Transitioning to a new centralised model for programme and service evaluations located in the Policy Office. The centralised evaluation model will:

- assist in making evaluations more impartial, independent and better able to meet best practice evaluation standards; and

- support DSS by improving the evidence base for effective policy and programme development and decision making to help achieve our mission.

Recommendation No.3

3.15 To benefit fully from programme evaluation activities, the ANAO recommends that entities administering grant funding develop implementation plans to follow through on evaluation findings and recommendations.

Entity responses:

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science

3.16 Agreed. The department has developed an integrated model to ensure evaluation needs are included in programme design and implementation, through the entire programme lifecycle.

Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development

3.17 Agreed. The department has strengthened its focus on programme evaluation and has established on Evaluation, Audit and Risk Section as part of its corporate framework. The section oversees the implementation of the Departmental Evaluation Strategy and Evaluation Capability Building Plan through developing evaluation resources, promoting relevant training and workshop opportunities, and supporting line areas to undertake evaluations and design monitoring and evaluation strategies. The team has assisted in the development of a Monitoring and Evaluation Strategy for the National Stronger Regions Fund. The strategy outlines the programme logic, including the outcomes and objectives of the programme, routine monitoring and reporting, measures and data sources, and an evaluation strategy for the programme.

Department of Social Services

3.18 Agreed. Through the department’s Programme Delivery Model, guidance is provided on conducting evaluations for each of the delivery models, tailored depending on the programme model. The guidance currently ceases once an evaluation has been conducted, with direction for the evaluation process to be reviewed and lessons learnt to be shared.

3.19 The department will update the Programme Delivery Model in line with proposals to monitor the adoption of evaluation recommendations, as determined by the Evaluation Unit.

What evidence is there that the desired behavioural change has occurred as a result of the grant funding?

Each programme had limited success in demonstrably influencing the behaviour of entities other than the funding recipient.

3.20 Each of the three grant programmes was intended to influence the behaviour of entities other than grant recipients. Specifically:

- one of the medium term outcomes set for the Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme was that the targeted organisations increased their use of energy efficient technologies, practices and behaviours; and

- the Liveable Cities programme and the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund both involved the award of funding for demonstration construction projects (the Liveable Cities programme also funded urban design and planning activities).

Energy efficiency information

3.21 The benchmarking research undertaken as part of the evaluation of the Energy Efficiency Information Grants Programme concluded that results were mixed in terms of targeted organisations taking action to reduce their energy consumption as a result of being better informed. This situation was identified as reflecting a range of factors, including that the programme was at its core an information provision programme that was not expected to result in huge changes in behaviour before the programme ended on 30 June 2015. Nevertheless, the research noted that some of the grant recipients used their funds to focus on energy efficiency assessments and action plans and so it would have been reasonable to expect a direct impact on behaviour.

More liveable cities

3.22 Liveable Cities programme funding was available for planning and design projects that would later be implemented (stream one) and demonstration construction-projects (stream two). These important leverage benefits were addressed in the funding application and assessment processes. Specifically, the Department of Social Services assessed:

- for stream one applications, the likelihood that designs and plans would be implemented; and

- for stream two applications, whether awarding funding to the project would be likely to result in other entities contemplating or undertaking similar work.

3.23 The leverage benefits were given little attention after agreements were signed with the successful applicants. Fortuitously, for a number of the design and planning projects, the final reports submitted to the department outlined that implementation activities were underway or the grant recipients expected that they would be implemented in the future. The situation was much less positive for stream two projects (which were to receive three quarters of contracted funding). In particular:

- it was common for the final reports submitted by project proponents to state that the project had achieved its outcomes but to not include data related to any outcome measurement approach that had been proposed in the application for funding. The department also did not seek that data;

- absent from the signed grant agreements were activities or requirements specifically designed to ensure the projects generate lessons that would be transferred and applied across Australia’s cities so as to deliver the desired outcome of improved planning and design; and

- there was some interest shown by the department in dissemination and transferability as part of the project closure process. Specifically, departmental procedures required that final reports submitted by project proponents be assessed in terms of the ‘dissemination and transferability of the project’s findings/recommendations’. This was a sound procedure given the programme guidelines had outlined that demonstration projects were to ‘facilitate urban renewal and strategic urban development’, but it was not supported by any obligation on funding recipients to disseminate information on their project benefits and lessons to other cities. In addition, the department had no dissemination strategies of its own in place.

3.24 For each of the four demonstration projects that have been completed, the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development assessed that the proponent’s final report had not provided any information on the dissemination and transferability of the funded project. But this situation did not cause the department to undertake any follow-up inquiries with the proponent, or to consider what work the department could usefully undertake to promote the benefits of similar projects being undertaken in other cities.

Disabled persons’ supported accommodation

3.25 The aims of the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund included ‘innovative designs and models for the delivery of supported accommodation which have the potential to influence the future provision of supported accommodation in the longer term’. Innovation had been emphasised in the Department of Social Services’ assessment of funding applications (for example, there were nine criteria but the weighted score against the innovation criterion was worth more than 36 per cent of the total score that could be achieved by an application).

3.26 In relation to innovation, Phase 2 of the evaluation concluded that:

- grant funding had been instrumental in enabling the funded organisations to move away from traditional designs of shared supported accommodation models; and

- learnings from the programme should be made public to influence future design.

3.27 The evaluation report recommended that the department develop a website to upload relevant details for all of the Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund funded projects, including photographs and floor plans to share learnings across the sector. This has yet to occur and the department had not otherwise taken steps to disseminate the benefits of, and lessons from, the funded projects.

Recommendation No.4

3.28 The ANAO recommends that, when designing and implementing grant programmes that fund capacity building and/or demonstration projects, entities implement strategies that aim to influence the behaviour of entities other than the grant recipients, and measure the impact.

Entity responses:

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science

3.29 Agreed, noting that capacity to indirectly influence behaviour may be limited and measuring behaviour change is highly complex. The Energy Efficiency Information Grants programme used its grant recipients (industry associations and non-profits) to reach the target audience of small and medium enterprises and community organisations. Consultants were then engaged to measure the reach and impact of the programme.

Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development

3.30 Agreed. The department notes the ANAO’s findings in relation to this recommendation. The department has incorporated evaluation of the impact on entities other than grant recipients in implementing grant programmes. The Monitoring and Evaluation Strategy for the National Stronger Regions Fund incorporates consideration of short, medium and long-term outcomes and benefits. For example, medium-term benefits of improved level of economic activity in regions, a more skilled workforce, and more stable and viable communities where people choose to live, are all examples of benefits identified in the programme design that are not necessarily captured by grant recipients. In addition, the department has conducted an evaluation of the programme to identify the extent to which the programme is on track to achieve its objectives.

Department of Social Services

3.31 The department notes this recommendation. The department’s Programme Delivery Model does not make any statements about the need to, or how to, influence entities that are outside the cohort of grant recipients. The inclusion of this objective within the policy intent of a programme and the levers that may or may not exist to bring this to effect will differ significantly across programmes and entity cohorts. For programmes that fund capacity building and/or demonstration projects, the department will consider if this element could be included in early considerations of programme design.