Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Defence's Management of Health Services to Australian Defence Force Personnel in Australia

The objective of the audit was to assess whether Defence is effectively managing the delivery of health services to ADF personnel in Australia (chiefly Garrison Health Services).

Summary

Introduction

1. Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel must be fit and free from illness or disability so that they can perform effectively under operational conditions. Accordingly, it is important that ADF members maintain a high level of preparedness for operational deployments. These can occur at short notice and have increased in number in recent years. For this reason, free health care, including dental and other ancillary health care , is a condition of service in the ADF.

2. The provision of comprehensive health care to ADF members as a condition of their employment is also seen as playing a role in attracting and retaining members in the forces. Recruitment and retention of ADF personnel is always an important issue for Defence given the significant investment required to train personnel and generate capability.

3. The level of health care provided to ADF members is that which is: ‘deemed necessary by the Chief of the Defence Force'. While the level of health care provided to the general community under Medicare is used as a guiding principle in determining the basic level of health care to which ADF members are entitled, Defence health policy recognises that the health services provided to ADF members will usually exceed this level of care so that the ADF requirement for members to meet and maintain operational readiness can be satisfied.

4. For example, members of the community with a medical condition that is not immediately life-threatening, seeking to have it treated under Medicare, may have to wait until a place is available for that condition to be treated. However, in the context of the ADF, such a medical condition is expected to be treated in a timely way to maximise the operational availability of the ADF member.

5. The ADF employs medical, dental and ancillary support health professionals, including members of the ADF Reserves, to support its military operations. These staff may also provide services to ADF members while they are not on deployment (that is, while ‘in garrison'). Defence also engages civilian health professionals (Contracted Health Professionals) to work exclusively or on a sessional basis, within ADF health facilities and provides its members with off-base health care that it generally pays for on a fee-for-service basis. Because of the difficulties involved in recruiting sufficient numbers of medical, dental and ancillary support health professionals for full-time service in the ADF, health professionals who are members of the ADF Reserves (Health Reservists) , provide specialist skills that are not available in the full-time military staff and generate additional operational capability.

6. There are some 104 health facilities around Australia currently providing health support services to ADF personnel in garrison. These facilities include ADF hospitals on military bases, a whole ward of a civilian hospital, health centres, regimental aid posts and sick bays providing outpatient services, psychology support units and rehabilitation services.

7. Joint Operations Command (JOC) and the single Services (Navy, Army and Air Force) are responsible for Operational Health Support (that is support for offshore operations, force assigned personnel, collective training, exercises and work-up activities and field training areas).

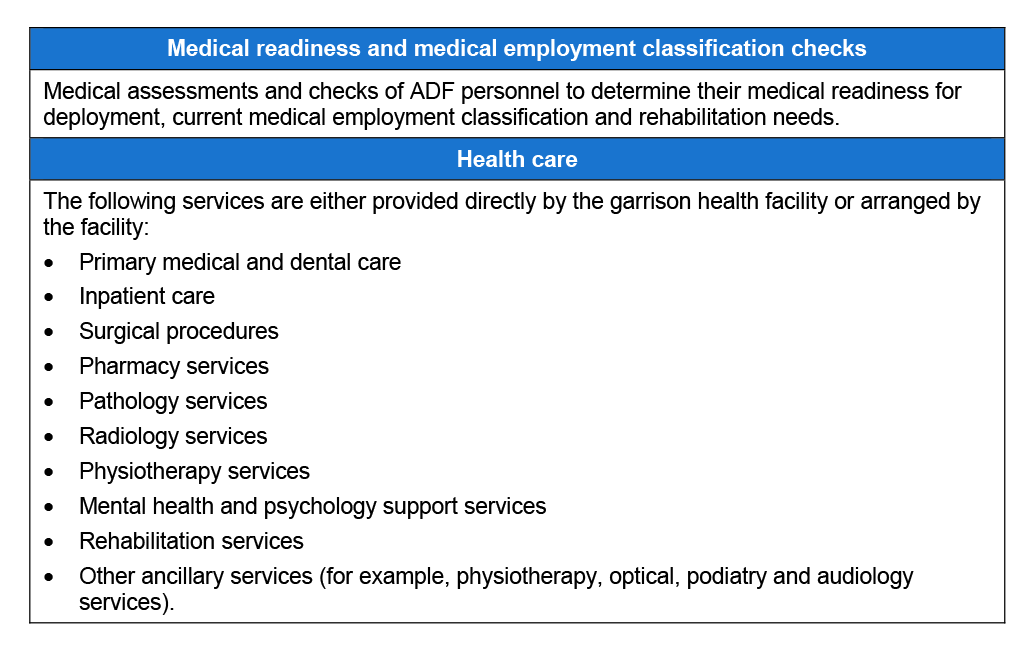

8. Non-Operational Health Support (that is, health support for non-deployed ADF personnel ‘in garrison' in Australia and any other health support that is not part of the Operational Health Support listed in paragraph 7) involves both the single Services and Joint Health Command (JHC). This support has to date mainly been provided by the single Services, in facilities that are attached to ADF units, but some Defence health facilities are managed and operated by JHC. In this audit report, health support provided to non-deployed ADF members in, or arranged by, Defence health facilities is termed ‘Garrison Health Services'. The range of services provided as part of Garrison Health Services is summarised at Figure S 1.

Figure S.1: Garrison Health Services

Source: ANAO analysis.

9. The provision of Garrison Health Services occurs in what Defence terms the National Support Area (NSA). In addition to its shared responsibility for the provision of Garrison Health Services, JHC has been responsible for the provision of other health support in the NSA. It also develops strategic health policy, provides strategic level health advice and exercises technical control of ADF health units.

10. Recognising a need to simplify the complex command and control arrangements for the delivery of Defence's health services and to improve the management of the services, the ADF's Chiefs of Service Committee (COSC) decided in July 2008 that responsibility for health services in the ADF should in future be split between:

- JHC, which will provide health care to ADF personnel within the NSA (that is, chiefly at the garrison level and in the other circumstances described in footnote 5), but with augmentation of resources from the single Services for Garrison Health Services; and

- JOC and the single Services, which will be responsible for health aspects of deployable capability.

11. As part of the 2009 Defence White Paper, the Government committed to extensive reform of Defence business to improve accountability, planning and productivity. In response to this, in June 2009, Defence announced the Strategic Reform Program, Delivering Force 2030 (the ‘SRP'). Under the SRP, Defence has committed to make gross savings of some $20 billion over the ten years from 2009–19. Defence expects to realise savings in the provision of health care of around $118 million in the budget of JHC over the 10 years of the SRP as part of the non-equipment procurement savings stream. JHC aims to realise efficiencies to achieve these savings by making better use of Defence health resources (for example, by consolidating the number of Defence health facilities into a single or small number of linked facilities at each base or regional location).

Audit approach

12. The objective of the audit was to assess whether Defence is effectively managing the delivery of health services to ADF personnel in Australia (chiefly Garrison Health Services).

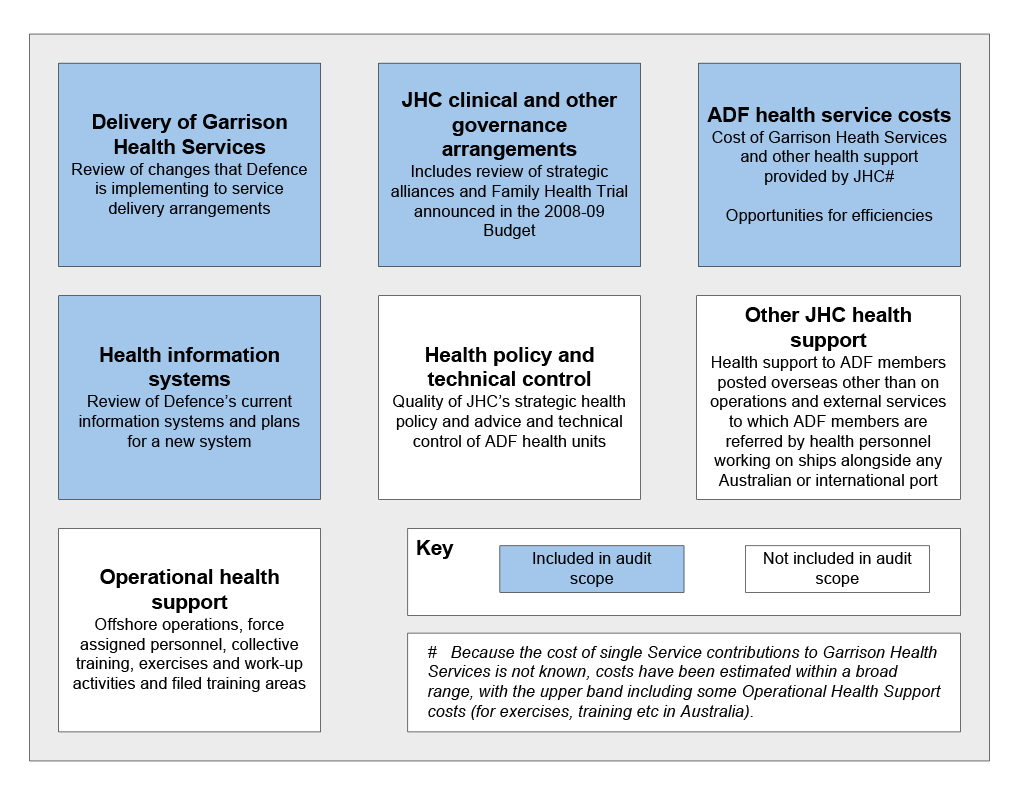

13. In particular, the audit reviewed Defence's reform of health services delivery to non-deployed ADF personnel in Australia, including the role of JHC and implementation of the revised arrangements for Garrison Health Services. The audit also examined the cost of Garrison Health Services and other health support provided by JHC, Defence's health information management systems and Defence's management of a trial, announced in the 2008–09 Budget and that was under way during the audit, of the provision of basic medical and dental services to dependants of full-time ADF members. The audit scope is depicted at Figure

S 2. It did not include a review of Operational Health Support.

Figure S.2: Audit scope – Health Services to ADF personnel in Australia

Source: ANAO analysis.

14. The high level criteria for the audit were that:

• Defence has effective arrangements for improving the delivery of ADF health services and, in particular, of Garrison Health Services; and

• Defence has effective information and patient records systems that support the delivery of ADF health services.

Overall conclusion

15. Defence provides comprehensive health support to around 55 000 ADF personnel. However, Defence recognises that there is scope to significantly improve the efficiency and effectiveness of its Garrison Health Services and is in the process of implementing reforms to the management and delivery of these services. While the overall direction of these changes is sound, because they are in the early stages of implementation and will take some years to complete, the ANAO has not been able assess their effectiveness.

Defence health services reforms

16. Two previous ANAO audits (1997 and 2001 ) and several internal and external reviews of JHC's predecessors have highlighted the difficulties posed for effective and efficient management of health care delivery to ADF members by the complex command and control arrangements for ADF health personnel. Defence's decision in July 2008 that JHC should have overall responsibility for Garrison Health Services will help to simplify somewhat the command and control of ADF personnel involved in delivery of Garrison Health Services, albeit that command and control arrangements for health personnel attached to single Service units who are involved in the delivery of Garrison Health Services continue to be complex.

17. Defence's planned model of health care delivery at the garrison level represents an improvement on the current model and should realise significant efficiencies if implemented effectively. Currently, there can be up to 11 Regimental Aid Posts and other medical facilities on a single base. The revised health care delivery model envisages consolidation of a range of services in a single facility (or a small number of linked or ‘hubbed' facilities) at each base or regional location, providing the opportunity for a more holistic health response. Basic services are to be provided from ‘hubbed' garrison locations and higher level and specialist services supplied from civilian facilities off-base.

18. JHC has negotiated service level agreements (SLAs) with each of the Services that provide endorsement of the new service model. These SLAs will be given effect at a local level through regional level agreements (RLAs) that JHC is currently in the process of negotiating. Defence has also sought to strengthen the management of JHC and of Garrison Health Services by moving to provide better oversight and support of health facilities , transferring responsibility for JHC from DSG to the Vice Chief of the Defence Force (VCDF) Group and increasing to three the number of one-star ADF branch head positions in JHC.

Governance arrangements for Garrison Health Services

19. Governance arrangements that Defence has in place for Garrison Health Services include high level oversight by senior Defence committees, an advisory committee and a well developed system of health directives , instructions and manuals. Defence has also made a number of organisational changes to support health care delivery. However, there are further opportunities to improve the governance arrangements for Garrison Health Services including by:

- strengthening the performance monitoring and accountability framework for Garrison Health Services;

- ensuring that the continued application of all health directives is reviewed every three years in accordance with current Defence policy;

- building on existing arrangements and reforms currently being implemented to enhance Defence's clinical governance framework;

- analysing the nature, frequency, types and underlying causes of complaints and the effectiveness of complaint resolution arrangements; and

- improving collection and analysis of information on health incidents as a means of identifying opportunities to further improve health care delivery.

20. Going forward, it will be important for the governance arrangements for ADF health support (including for both Operational and Garrison Health Services) to be sufficiently flexible to support innovative solutions Defence is adopting to address some of the particular challenges it faces in having sufficient access to appropriately qualified health personnel and services. In this context, Defence is currently exploring strategies to facilitate the timely release of health professionals who are members of the ADF Reserves (Health Reservists) from their regular employment to assist with emergency situations in the future. Defence has reached an agreement with the University of Queensland for the establishment of an inaugural Chair of Military Surgery to help strengthen, shape and lead military surgery, research and training for military surgeons. Defence also has local arrangements in place with various civilian hospitals for ADF health professionals to gain clinical experience in acute care.

21. As part of Garrison Health Services, JHC is also seeking to develop strategic alliances with state and territory hospitals for the provision of services. Defence already has a commercial arrangement with St Vincent's Hospital in Sydney that provides good access for ADF members to surgical facilities at the hospital and recovery in an ADF ward at the hospital. Defence considers that this arrangement provides a good model for the provision of acute care to ADF members in other locations in the future, should this be needed.

Managing the cost of ADF health services

22. Defence does not have in place mechanisms to monitor the total cost of Defence health services or its major components such as Garrison Health Services, other JHC activities and Operational Health Support. While Defence has not routinely monitored all costs related to the provision of Garrison Health Services, a 2006 review commissioned by the Chiefs of Services Committee (COSC) attempted to establish the total costs. The review calculated that the total annual cost of health care provided to ADF members at garrison level had increased in the period from 2001–02 to 2005–06 by around 16.7 per cent per annum to $293 million. In 2008–09 prices, this would equate to about $335 million. However, since health care costs in the community, and in Defence, have increased more rapidly than consumer prices, the estimate of $335 million is likely to be understated. For example, over the ten years to 2007–08, total health expenditure in Australia increased in real terms by around 5.2 per cent a year.

23. The ANAO estimates that expenses on Garrison Health Services currently range between $455 million and $654 million. As Defence is unable to identify the proportion of their time that ADF single Service health members are spending on Garrison Health Services, the ANAO's estimates cover a wide band. However, these estimates are broadly consistent with previous estimates of total Garrison Health Services expenses.

24. Monitoring is necessary to provide assurance that the overall cost of Defence health services, including Garrison Health Services, is being effectively managed. JHC manages only part of the cost of Garrison Health Services; the remaining cost components are the responsibility of the single Services, the Defence Support Group (DSG) and the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO). Current Defence financial systems do not effectively support the identification of relevant costs across the various parts of the agency that aggregate to form the total cost of health care provided to ADF members.

25. There was rapid growth in Defence's expenditures related to purchased health professional services over the five years from 2004–05 to 2008–09, with total expenditures increasing from $162 million in 2004–05 to $261 million in 2008–09. Over the same period, expenditure by JHC on ADF employees fell around eight per cent from $42 million in 2004–05 to $39 million in 2008–09. Accordingly, to assist in reducing reliance on these contractor resources, it is important that Defence maximise the use of the ADF health personnel already in garrison to provide Garrison Health Services, consistent with operational requirements and the requirement for them also to gain experience in acute care settings to ready them for deployment. Defence is also examining the scope to increase the number of Australian Public Service (APS) health personnel employed by the department, who have been assessed as less expensive overall than contractors, as a means of reducing the current high cost of using Contracted Health Professionals.

26. Other opportunities to reduce the cost of Garrison Health Services include:

- ensuring that the level of health support provided to ADF members is aligned with operational requirements;

- redirecting ADF health care resources away from work that adds limited value; and

- transferring responsibility for administrative tasks from health personnel to administrative support staff, where it is professionally appropriate and cost effective to do so.

Health information systems

27. Defence does not currently have effective information and patient records systems to support the delivery of ADF health services. These systems are needed to help realise efficiencies (for example, through the provision of better management information) in the provision of appropriate health care for ADF members.

28. Defence has previously attempted to introduce a patient records system, the Health Key Solution or HealthKEYS. However, users found HealthKEYS difficult to use (for example, moving between different screens is not easy and the system has poor response times). For this reason, only some health facilities currently use HealthKEYS and Defence has now decided to introduce a replacement system which is currently under development. A lesson learnt from the failure of HealthKEYS is the need for the system to meet user needs. Defence expects to progressively deploy its replacement system, to be developed based on commercial off-the-shelf products and to be called the Joint e-Health Data Information system (JeHDI), between July 2011 and December 2013.

Key findings

Defence health service reforms (Chapter 2)

Command and control of Garrison Health Services

29. A 1997 ANAO audit and several internal and external reviews of JHC's predecessors have previously highlighted the difficulties posed for effective and efficient management of health care delivery to ADF members by the complex command and control arrangements for ADF health personnel.

30. Defence's decision in July 2008 that JHC should have overall responsibility for Garrison Health Services will help to simplify the command and control of ADF personnel involved in delivery of Garrison Health Services. However, there may be the potential to simplify command and control arrangements relating to health care delivery in garrisons even further by integrating the single Services' health units within JHC. For example, it would be possible for all ADF health personnel to be employed by JHC, but be formally transferred to units for the duration of a deployment and be available for training with units in preparation for deployments. When on deployment, the health personnel would come under the command and control of the deployed unit's commander. Under this approach, there would no longer be a requirement to retain separate health agencies in each of the single Services. A similar option was proposed in the 1997 ANAO performance audit. In the longer term, the ANAO suggests that Defence re-examine this option.

Efficiency and effectiveness of Garrison Health Services

31. Defence's planned model of health care delivery at the garrison level represents an improvement on the current model and should realise significant efficiencies if implemented effectively. Currently, there can be up to 11 Regimental Aid Posts and other medical facilities on a single base. The revised health care delivery model envisages consolidation of a range of services in a single facility (or a small number of linked or ‘hubbed' facilities) at each base or regional location, so providing the opportunity to provide a more holistic health response. Basic services are to be provided from ‘hubbed' garrison locations and higher level and specialist services supplied from civilian facilities off-base. A diagram of this service model is at Figure 2.3.

Implementation of the new Garrison Health Services delivery model

32. JHC has negotiated service level agreements (SLAs) with each of the Services that provide endorsement of the new service model. These SLAs will be given effect at a local level through regional level agreements (RLAs) which will detail the services, responsibilities and expected requirements of JHC and each single Service at military locations in each JHC region. The arrangements that will apply at each location will be dependent on the needs of the particular location. The completion of the RLAs has not yet been finalised, although JHC has made considerable progress in understanding the services that are required in each region.

33. Defence has also sought to strengthen the management of JHC and of Garrison Health Services by:

- moving to provide better oversight and support of health facilities. Currently, JHC has nine regions, but these are to be reduced to five, mirroring regional boundaries already adopted by the Defence Support Group (DSG). Senior Regional Health Directors (RHDs) are to be appointed to head these new JHC regional offices and improve direction of them; and

- transferring responsibility for JHC from DSG to the Vice Chief of the Defence Force (VCDF) Group and increasing to three the number of one-star ADF branch head positions in JHC, one each from the three Services (an additional one-star position was created in JHC for this purpose and a fourth branch head position, headed by an APS officer, has also been established to manage Defence's mental health services). The three one-star officers, in addition to their JHC responsibilities, are responsible for representing the interests of each Service as a means of improving coordination between the three Services.

34. Although the direction of these reforms is sound, it is too early to assess the effectiveness of them, since some elements of the reforms are in the early stages of implementation. Much will also depend on the outcomes of negotiations on the new RLAs and the effectiveness of support to be provided by the new RHDs.

Governance arrangements for Garrison Health Services (Chapter 3)

35. Governance arrangements that Defence has in place for Garrison Health Services include high level oversight by senior Defence committees, an advisory committee and a well developed system of health directives, instructions and manuals. Defence has also made a number of organisational changes to support health care delivery. However, the ANAO considers that governance arrangements for Garrison Health Services can be improved.

Planning and performance monitoring

36. Significantly, JHC does not have a current strategic plan, which is required given the many changes to priorities flowing from Defence's reforms of Garrison Health Services and the Strategic Reform Program. Related to this, Defence also has few meaningful measures against which to monitor its performance and how well health services are being delivered, due in large measure to the lack of a reliable, robust and complete health management information system across the ADF. Defence's performance monitoring and accountability framework for Garrison Health Services could be strengthened by:

- developing both effectiveness and efficiency Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that adequately reflect JHC's business performance and which can be progressively refined and implemented over the course of the reforms as improved management information becomes available; and

- including the provision of annual performance reports against these KPIs in the context of the Department's annual report or on its website.

37. In this context, Defence informed the ANAO that it has now commenced work on a new performance management framework.

Clinical governance

38. Defence has a well developed system of directives, instructions and manuals to support health care delivery to both deployed and non-deployed ADF personnel. While Defence's policy is that the continued application of all health directives should be reviewed every three years, this has not been occurring. The ANAO considers it is important that all health directives are reviewed in accordance with this policy, with performance against this benchmark being monitored and reported on.

39. There are also opportunities to improve Defence's clinical governance framework, which is built on the credentialing of health professionals, the accreditation of facilities, health incident reporting, the management of health complaints and the orientation of health staff.

40. To provide assurance on the credentialing of health professionals, Defence requires ADF health professionals to maintain their health credentials. Currently, this is monitored by the single Services, but, as JHC takes on responsibility for Garrison Health Services, it will need to put in place arrangements to monitor the credentials of all ADF health personnel working in its facilities.

41. Accreditation of health facilities is important in providing assurance that health care provision will not be compromised by facilities that do not meet recognised health standards. In the past, Defence has primarily accredited its facilities against International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards. However, Defence is now planning to accredit most of its facilities against Royal Australian College of General Practice (RACGP) standards for ADF primary care, Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS) for inpatient facilities and National Association of Testing Authorities (NATA) standards for pathology laboratories. The standards for ADF primary care will be tailored to the specific needs of ADF health facilities. Defence is also planning to conduct internal audits of facilities against the new standards. Defence is considering the extension of the new accreditation arrangements to dentistry at a later stage. It is not yet possible to assess the effectiveness of these arrangements, since they have still to be implemented. However, if effectively implemented, the new arrangements should provide the necessary assurance that health facilities meet recognised health standards.

42. The performance of each Contracted Health Professional working in ADF facilities is reviewed by JHC annually. However, there is little clinical supervision of them by ADF members. The ANAO considers that, with the significant number of Contracted Health Professionals working in Defence health facilities (786 in September 2009), there is a need for JHC to put in place mechanisms to ensure that there is adequate clinical supervision of them. This would, for example, help to ensure that Contracted Health Professionals are aware of and are applying ADF health policies.

43. Defence collects and monitors information on client feedback and complaints, but analysis of the nature, frequency, types and underlying causes of complaints and the effectiveness of complaint resolution arrangements would further improve these arrangements.

44. JHC does not have a system to collect information on reported health incidents. However, it has advised that it is taking steps to introduce paper-based arrangements to collect and analyse information on health incidents as a means of identifying opportunities to further improve health care delivery. The ANAO considers that an effective health incident management system is an essential part of an integrated clinical management system.

Strategic alliances

45. As noted in paragraph 20, it will be important for the governance arrangements for Defence health services (including for both Operational and Garrison Health Services) to be sufficiently flexible to support innovative solutions Defence is adopting to address some of the particular challenges it faces in having sufficient access to appropriately qualified health personnel and services.

46. Because of the ADF's ongoing need for Health Reservists, Defence has had in place for some time higher level Employer Support Payments in respect of medical, dental, nursing and allied health officers (who are within specified health disciplines) undertaking various forms of Defence service. However, in the event of an emergency, Defence needs to have quick access to the services of Health Reservists. Until now, the release of these members from their regular employment has been on an ad hoc basis. This relies heavily on the goodwill of state and territory hospitals and the personal availability of the Health Reservists themselves.

47. Accordingly, Defence is currently exploring strategies to facilitate the timely release of such health personnel to assist with emergency situations in the future. For example, Defence is considering entering into strategic alliances with state and territory public hospitals at which many Health Reservists are currently employed to develop teams of personnel, who would continue to work in the public hospitals on a day-to-day basis, but who, as Health Reservists, could also be released for Defence deployments at short notice. Such an alliance is currently being explored with the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital (RBWH) and the Queensland Department of Health. Defence has also reached an agreement with the University of Queensland for the establishment of an inaugural Chair of Military Surgery to help strengthen, shape and lead military surgery, research and training for military surgeons.

48. JHC is seeking to develop strategic alliances with state and territory hospitals for the provision of services for Garrison Health Services. It has a commercial arrangement with St Vincent's Hospital in Sydney that provides good access for ADF members to surgical facilities at the hospital and recovery in an ADF ward at the hospital. Defence considers that this arrangement provides a good model for the provision of acute care to ADF members in other locations in the future, should this be needed.

49. Defence also has local arrangements in place with various civilian hospitals to provide clinical experience in acute care areas to ADF members as required. However, as JHC assumes responsibility for Garrison Health Services, the ANAO considers there would be benefit in it systematically developing and monitoring arrangements with civilian hospitals for ADF medical staff to gain the required clinical experience. These arrangements should be developed in cooperation with the single Services to ensure that all ADF medical personnel, including those not providing Garrison Health Services, are able to acquire beneficial clinical experience.

Family Health Trial

50. The Family Health Trial has only recently been implemented, and so it has not been possible to assess it fully. However, given risks identified with the trial, including its high cost, the ANAO suggests that Defence undertake a preliminary evaluation of it after it has been operating for a year.

Managing the cost of ADF health services in Australia (Chapter 4)

51. JHC's administered expenses are almost entirely made up of the cost of Contracted Health Professionals (employed either as individuals or via regional prime contracts) and the costs of medical and dental services provided by civilian health professionals on a fee-for-service basis. However, these costs make up only a small part of ADF health care costs. They do not include expenses related to ADF and APS health personnel working in garrison health facilities; the bulk of expenses related to health materiel; expenses incurred in maintaining and operating ADF health facilities; or corporate services expenses, such as information technology (IT) expenses.

52. JHC expenditures on purchased health professional services increased by around 60 per cent from $162 million in 2004–05 to $261 million in 2008–09, while its expenditures on ADF employees fell around eight per cent from

$42 million in 2004–05 to $39 million in 2008–09.

53. Defence does not monitor the overall cost of Defence health care, including Garrison Health Services, provided to ADF members. Such monitoring is necessary to provide the required assurance that the overall cost of health care in Defence is being effectively managed and because changes in one part of Garrison Health Services can affect the cost in other areas. JHC manages part of the cost of Garrison Health Services; the remaining cost components are the responsibility of the single Services, the Defence Support Group (DSG) and the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO). Current Defence financial systems do not support the identification of relevant costs across the various parts of the agency that aggregate to form the total cost of health care provided to ADF members. So that JHC can develop accurate estimates of the total cost of Defence health care and then monitor these costs, the other relevant areas of Defence will need to provide it with details of the cost of Garrison Health Services related services that they provide.

Estimated cost of Defence health care in Australia

54. The ANAO estimates that expenses on Garrison Health Services range between $455 million, excluding the cost of non-JHC ADF single Service members providing Garrison Health Services, and $654 million if all non-JHC ADF health members in garrison are included (although some of their time will be spent in preparing for operations and other matters, rather than in providing Garrison Health Services). These estimates are broadly consistent with previous estimates of total Garrison Health Services expenses.

55. The 1996–97 audit compared ADF health care costs with estimates of health costs in the community. At that time, the cost per ADF member was almost three times the Australian average. This cost included the cost of all ADF members providing health support (around 2382 members). The ANAO estimates that the cost per ADF member is now between about 1.7 (excluding non-JHC ADF members in garrison) and about 2.5 times (including non-JHC ADF members in garrison) the cost per person in the wider Australian community.

56. There are several reasons why ADF health care costs exceed the cost per person in the community. These relate to the maintenance of a military that is well prepared for operational duty and government policy that, for this purpose, ADF members should be provided with free health care.

Reducing the cost of Defence health care

57. There is scope for Defence to reduce the cost of health care to ADF members and one of the objectives of the current health reforms by Defence is to realise efficiencies in its health care delivery. Contracted Health Professional, fee-for-service and sessional provider health services costs are rising largely in response to reducing numbers of ADF health personnel who are providing Garrison Health Services. It is important therefore that ADF health personnel are actively used by Defence to provide Garrison Health Services, consistent with operational requirements and the need for such staff also to gain experience in acute care settings. Defence is also examining the scope to increase the number of APS health personnel employed by the department as a means of reducing the current high cost of using Contracted Health Professionals.

58. Other opportunities to reduce the cost of Garrison Health Services include:

- ensuring that the level of health support provided to ADF members is aligned with operational requirements;

- redirecting ADF health care resources away from work that adds limited value. For example, the current mandatory annual health assessments undertaken for all ADF members may not provide an efficient and cost effective means of determining an ADF member's readiness for deployment or of promoting the health of ADF members; and

- transferring responsibility for administrative tasks from health personnel to administrative support staff, where it is professionally appropriate and cost effective to do so.

Health information systems (Chapter 5)

59. Defence has several electronic health (e-health) information systems but, despite considerable efforts over the past 20 years, it still does not have a single patient records management system. As a result Defence medical personnel continue to rely primarily on paper-based patient records. One of its existing systems, Health Key Solution or HealthKEYS, was intended to meet Defence's e-health patient records needs. However, it does not do so, because among other things the selected system was out-dated, not suited to Defence's preferred information architecture model and was not implemented efficiently and effectively. Another system used widely within Defence health facilities is the Medical Information Management Index (MIMI). However, this system was not developed as a fully functioning health information system and has many limitations. In most locations, it is facility based.

60. Defence recognises that the absence of a comprehensive e-health information system is inefficient and, as noted earlier, has decided that a new system, based on a suite of commercial off-the-shelf products and to be called the Joint e-Health Data Information system (JeHDI), should be developed. In February 2010, Defence called for tenders for the development of this system. Defence expects JeHDI to be progressively deployed between July 2011 and December 2013.

61. The failed development and implementation of HealthKEYS emphasises the value of having strong project governance arrangements, independent assurance of the development of a system and effective change management during the implementation phase.

Defence response

62. Defence acknowledges the ANAO report findings in relation to Defence's Management of Health Services to Australian Defence Force Personnel in Australia. Defence agrees fully with five of the recommendations and agrees with qualification to one recommendation.

63. Joint Health Command within Defence has been undertaking a significant health reform program for the past 18 months as is acknowledged in the audit report. Defence's reform activities will address the requirements of the agreed recommendations.

64. Defence as a matter of course will continue to pursue continuous improvement in relation to the provision of Health Services for ADF personnel both in Australia and overseas.