Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Defence’s Procurement of Offshore Patrol Vessels — SEA 1180 Phase 1

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Defence’s SEA 1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV) program is intended to enhance the Australian Defence Force's maritime capability and is one of three interrelated elements of the Australian Government's 2017 Naval Shipbuilding Plan.

- The Government’s requirements to split OPV construction between two shipyards, and a compressed build schedule, pose challenges to Defence in managing program risks.

- The OPV program was last examined in Auditor-General Report No.39 2017–18 Naval Construction Programs—Mobilisation, which found that Defence carried several risks into the OPV acquisition as a consequence of the compressed schedule.

Key facts

- Defence is acquiring 12 new OPVs and associated support systems for the Royal Australian Navy through SEA 1180 Phase 1, at an approved cost of $3.58 billion.

- On 31 January 2018, Defence signed a $1.988 billion (GST-exclusive) contract for the design and build of the OPVs with Luerssen Australia Pty Ltd.

What did we find?

- To date, Defence’s procurement and contract management of the OPV program have been largely effective and have supported the achievement of a value for money outcome.

- Defence conducted a largely effective platform selection process which supported the achievement of a value for money outcome.

- Defence has largely established fit-for-purpose contracting and program governance arrangements for the OPV program.

- Defence’s OPV program has been largely effective to date in making progress against its milestones and has contributed to delivery of the wider Naval Shipbuilding Plan.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made two recommendations aimed at: improving Defence’s processes for the effective sequencing of Independent Assurance Reviews; and retaining evidence and advice regarding decision-making in procurement.

- Defence agreed to both recommendations.

$3.58 billion

is the approved acquisition cost of the OPVs.

3

OPVs were under construction as at September 2020, in two shipyards.

59%

Australian Industry Content commitment, reported to have risen to 62.8% and a value of $1.248 billion.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The SEA 1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV) program, at an approved cost of $3.58 billion, is acquiring 12 new patrol vessels and associated support systems to replace and improve upon the capability delivered by the Royal Australian Navy’s (Navy) existing fleet of 13 Armidale class patrol boats.

2. The acquisition of 12 OPVs was included in the Australian Government’s 2016 Defence White Paper as a contributor to the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) maritime capability. The primary role of the OPVs will be to undertake patrol and response duties, security operations and border protection activities. The construction of the OPVs is also a key element of the Government’s continuous naval shipbuilding program under the Naval Shipbuilding Plan (May 2017).

3. The Government selected German shipbuilder, Fr. Lürssen Werft GmbH & Co. KG (Lürssen), through a competitive evaluation process1 to be the designer and prime contractor for the OPVs. The first two OPVs will be built at the Osborne South shipyard (Osborne) in South Australia by ASC OPV Shipbuilder Pty Ltd. The remaining 10 OPVs will be built at the Henderson maritime precinct (Henderson) in Western Australia by Civmec Construction & Engineering Pty Ltd (Civmec). As of July 2020, construction of the first three OPVs was underway — two at Osborne and one at Henderson.

4. The OPVs will be named the Arafura class. The first-of-class vessel, HMAS Arafura, is planned to enter Navy service in 2022.2 The last OPV is expected to enter service in 2030.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The OPV program is intended to enhance ADF maritime capability and is one of three interrelated components of the Australian Government’s continuous naval shipbuilding program under the Naval Shipbuilding Plan.3 The Government has identified the OPV program as having an important role in mitigating identified risks to workforce continuity at the Osborne shipyard between the end of the Hobart class air warfare destroyer build and the commencement of the Hunter class frigate build. The Government’s requirements to split OPV construction between two shipyards under an accelerated build schedule pose a challenge to Defence in managing program risks. The audit will provide assurance to the Parliament on the effectiveness of Defence’s procurement and management of the OPV program, its ability to deliver the required capability on schedule and within budget, the workforce outcomes achieved, and the program’s contribution to delivery of the Naval Shipbuilding Plan in establishing a sovereign naval shipbuilding enterprise.

6. The OPV program was last examined by the ANAO in the context of Auditor-General Report No.39 2017–18 Naval Construction Programs—Mobilisation. The audit concluded that at the time of tabling (May 2018) Defence was meeting scheduled milestones to deliver the OPV program, although the program was still at an early stage. A key finding of the audit was that the design and build milestones for the OPV program were brought forward to help maintain the shipbuilding workforce from the end of the Hobart class destroyer build to commencement of the Future Frigate build. As a consequence of the compressed schedule, Defence carried several risks into the OPV acquisition. In particular, reliable sustainment cost estimates were not provided to the Government at second pass approval, and commercial arrangements between the selected shipbuilder and Australian shipbuilding firms had not been settled when the tender outcome was announced.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness to date of Defence’s procurement and contract management of the OPV program.

8. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Did Defence conduct an effective competitive evaluation process for the procurement of the OPVs that supported the achievement of value for money?

- Has Defence established fit-for-purpose contracting and program governance arrangements?

- Is the OPV program meeting program milestones and supporting the delivery of the Naval Shipbuilding Plan?

Conclusion

9. To date, Defence’s procurement and contract management of the Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV) program have been largely effective and have supported the achievement of a value for money outcome.

10. Defence conducted a largely effective platform selection process which supported the achievement of a value for money outcome. Defence surveyed the market for an appropriate OPV design and implemented a well-documented process to select three designs for detailed evaluation. The competitive evaluation process was supported by appropriate governance, assurance and probity arrangements and a Tender Evaluation Plan that was applied consistently across the three invited tenders, to provide a basis for assessing value for money. The tender evaluation process addressed the essential criteria and requirements that the Government had set for the program. The effectiveness of Defence’s processes was impacted by the poor timing of and information access restrictions placed on a key assurance review activity, shortcomings in Defence record-keeping for the introduction of an additional condition late in the platform selection process, and Defence’s approach to advising its ministers.

11. Defence has largely established fit-for-purpose contracting and program governance arrangements for the OPV program. Contractual arrangements reflect the key preferred Commonwealth negotiation outcomes and the program governance and oversight structure includes an issues escalation process. To establish the contract and commence construction in the expected timeframes, a number of issues were not finalised at contract signature in January 2018 and remained incomplete in July 2020. Processes for monitoring progress against the contract schedule and activities to verify the accuracy of Australian Industry Capability (AIC) reported by the prime contractor are yet to be fully established. As of July 2020 the program was constructing the first three vessels without an Earned Value Management System or approved shipbuilder specific Contract Master Schedules to measure progress against an agreed baseline, as required under the contract.

12. Defence’s OPV program has been largely effective to date in making progress against its milestones and has contributed to delivery of the wider Naval Shipbuilding Plan. As at July 2020 all but three program milestones were met on time, with Defence withholding payments for these three missed review milestones. Through its reviews, Defence has identified early signs of design and integration risks emerging, particularly with regards to Government Furnished Equipment. Delivery of the required capability will depend on Defence actively managing the identified risks, a number of which are related to the accelerated build schedule. As the foundation program for the Government’s continuous naval shipbuilding program, there is evidence that the OPV program is contributing to the delivery of the wider naval shipbuilding enterprise, including through the transfer of shipbuilding expertise to Australia.

Supporting findings

Platform selection

13. While Defence established appropriate governance, assurance and probity arrangements for the platform selection process, the implementation of one aspect of the assurance arrangements was not fully effective. Defence established fit-for-purpose arrangements to conduct and oversight the competitive evaluation process, which included a series of steering groups and internal reviews to provide assurance to senior leaders. The reviews usefully identified issues requiring attention but in one case, the poor sequencing of the activity and the restrictions on the reviewers’ access to information compromised the effectiveness of the assurance review activity. Defence made appropriate arrangements for obtaining third-party legal and probity advice during the competitive evaluation process.

14. Defence conducted an effective process to select three ship designers — Lürssen, Fassmer and Damen — to participate in the competitive evaluation process. Advice to the Government on the viability of available ship designs was informed by a market study and screening process which helped Defence survey the market for an appropriate OPV design, followed by a formal assessment against three risks — capability, cost and risk to commencing construction in 2018.

15. Defence conducted an effective tender evaluation process that supported the achievement of value for money outcomes. The tender process was preceded by a design risk reduction process which required the three invited tenderers to refine their offers and establish the baseline ship design to be proposed in their responses to the request for tender. The tender evaluation process documented in the Tender Evaluation Plan was applied consistently across the three tenders and reporting to the delegate in the Source Evaluation Report aligned with the findings in the Tender Evaluation Criteria Reports and outlined the results of the value for money assessment. The tender evaluation process addressed the essential criteria and requirements that the Government had set for the program.

16. Defence’s approach to advising its ministers, to inform their submission to government for second pass approval, was not appropriate as it did not include a clear recommendation on the preferred design and did not offer its ministers an opinion on its assessment of value for money — a core departmental function in procurement. There were shortcomings in Defence’s documentation of the basis of its advice to its ministers to also include Austal as a potential shipbuilder for the Lürssen design.

Contracting and program governance

17. Defence’s contract with Luerssen for the acquisition of 12 new OPVs and associated support system components is fit-for-purpose, reflecting preferred Commonwealth negotiation outcomes. Defence’s contract negotiation approach was informed by a Contract Negotiation Directive and an Acquisition Contract Negotiation Plan which provided guidance on core negotiation issues. While all key identified negotiation issues were addressed during the contract negotiation process, some matters had not been finalised when the contract was signed in January 2018 and remained incomplete in July 2020. These were the establishment of the performance management framework and implementation of the Naval Shipbuilding Principals’ Council.

18. Defence has largely established a fit-for-purpose governance and oversight structure for the OPV program. However, assurance arrangements are yet to be fully established, including processes for monitoring progress against the contract schedule and activities to verify the accuracy of the value of AIC reported by the prime contractor. As of July 2020 the program was constructing the first three vessels without an Earned Value Management System or approved shipbuilder specific Contract Master Schedules to measure progress against an agreed baseline, as required under the contract.

Progress against milestones

19. The OPV program milestones have been developed to achieve the Government’s requirements for an accelerated build schedule to manage shipbuilding workforce risks. As at July 2020, the program had achieved 29 contractual review and construction milestones on time or ahead of schedule. Three reviews were delayed, with payments withheld by Defence for these three missed milestones. Defence has identified system integration risks and emerging design risks, particularly relating to Government Furnished Equipment, that could impact program schedule and cost at later stages of program delivery. There has been some rework in the course of construction that was driven by design work occurring in parallel with OPV construction, with design changes subject to a monitoring and approval process. Program cost is within the allocated budget and the program has not accessed contingency funding. Delivery of the required capability on time and within budget will be dependent on the active management of identified design and integration risks.

20. To date, the OPV program remains largely aligned with the Government’s wider continuous naval shipbuilding plan and enterprise. The OPV program is supporting the delivery of the key Naval Shipbuilding Plan outcomes of naval capability enhancement, shipbuilding infrastructure improvement, Australian industry involvement and the transfer to Australia of shipbuilding expertise, and job creation. Two Defence reviews have identified uncertainties as to whether the OPV program has ‘de-risked’ production of the Hunter class frigate as intended, by trained OPV workers transitioning to the frigate program.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.21

That Defence plan the sequencing of Independent Assurance Reviews undertaken during a platform selection process, to avoid conflicts with other processes and ensure access to all relevant information.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 2.97

That Defence, consistent with requirements to maintain Commonwealth records, document and retain all evidence and advice regarding its decision-making in procurement.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

21. The proposed audit report was provided to the Department of Defence. Defence’s summary response is provided below and its full response is at Appendix 1.

Defence welcomes the ANAO’s conclusion that the procurement and contract management of the Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPV) has been assessed as largely effective and achieving a value for money outcome.

To address the recommendations made by the audit, Defence will improve planning and timing of Independent Assurance Reviews during selection processes to ensure that these reviews are conducted effectively, and that reviewers can access the required information. Defence will also ensure that procurement records are maintained in line with requirements.

The OPV project has been developed and executed ahead of the Naval Shipbuilding Plan and was accelerated by the Government in 2015 to ensure commencement of the build in late 2018. The strategy to achieve construction in 2018 was ‘minimum change’ to an established design. To date, all major construction milestones have been achieved despite the growing impact of the COVID 19 pandemic. Defence has also chosen a highly experienced designer and shipbuilding prime contractor in Luerssen to affect a knowledge transfer to Defence and Industry, and establish an efficient shipbuilding industry.

The production of Arafura Class Offshore Patrol Vessels is currently occurring in both South Australia and Western Australia. The Arafura Class Offshore Patrol Vessel will provide Navy with a highly capable vessel when it comes into service in 2022. Defence is also actively planning the Sustainment arrangements for the Offshore Patrol Vessels with an emphasis on implementing region based maintenance arrangements.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Department of Defence (Defence) is acquiring 12 new Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs) and associated support systems for the Royal Australian Navy (Navy) through the SEA 1180 Phase 1 program, at an approved cost of $3.58 billion. The OPVs are expected to:

… provide greater range and endurance than the existing Armidale Class patrol boat fleet. The new vessels will be capable of undertaking several different roles, including enhanced border protection and patrol missions, over greater distances than is currently possible with the existing patrol boat fleet.4

1.2 SEA 1180 Phase 1 has two key objectives:

- to construct 12 OPVs between 2018 and 2030 to replace and improve upon the Australian Defence Force (ADF) capability delivered by the Armidale class patrol boats; and

- to contribute to the Government’s continuous naval shipbuilding program (see Box 1) in accordance with analysis undertaken for Defence in 2015 (the 2015 shipbuilding analysis).5

1.3 The 13 Armidale class patrol boats currently in use are due to be withdrawn from Navy service between 2020 and 2022.6 As of July 2020, construction of the first three OPVs was underway at shipyards in South Australia (two vessels) and Western Australia (one vessel). The Government announced in November 2018 that the OPVs will be named the Arafura class, with the first-of-class expected to enter Navy service in 2022.7

|

Box 1: Continuous naval shipbuilding program |

|

In August 2015, the Government announced that the OPV program would become part of the continuous naval shipbuilding program.a In its announcement, the Government stated that it was:

The 2016 Defence White Paper stated that:

The accompanying 2016 Defence Integrated Investment Program outlined the Government’s investment of over $90 billion in the continuous naval shipbuilding program and allocated up to $4 billion for design and construction of the OPVs.c The Government’s May 2017 Naval Shipbuilding Pland involves the rolling acquisition of new submarines and the continuous build of major ships such as future frigates, as well as minor naval vessels such as the OPV.e The continuous naval shipbuilding program, commencing in 2018, was intended to address a gap in workforce demand and maintain the shipbuilding workforce in South Australia. Defence’s 2015 shipbuilding analysis (see footnote 4 above) identified a gap in demand for workers, measured by full-time-equivalent (FTE) workers, between the completion of the Hobart class destroyer (AWD) build in 2019 and the expected start of Hunter class frigate construction in 2020. The gap (referred to as the ‘valley of death’) is illustrated in Figure 1.1. Figure 1.1: 2015 shipbuilding analysis of the workforce profile for building the Hobart Class air warfare destroyers and Hunter class frigates

Source: RAND Corporation, Australian Naval Shipbuilding Enterprise: Preparing for the 21st Century, 2015. |

Note a: Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, media release, ‘The Government’s plan for a strong and sustainable naval shipbuilding industry’, media release, 4 August 2015, available from https://www.minister. defence.gov.au/minister/kevin-andrews/media-releases/joint-media-release-prime-minister-and-minister-defence-1 [accessed 22 September 2020].

Note b: Department of Defence, 2016 Defence White Paper, p. 21.

Note c: Department of Defence, 2016 Defence Integrated Investment Program, pp. 89–90.

Note d: The Naval Shipbuilding Plan was released by the Minister for Defence on 16 May 2017. See media release, ‘Securing Australia’s naval shipbuilding and sustainment industry’, available from https://www.minister. defence.gov.au/minister/marise-payne/media-releases/securing-australia-naval-shipbuilding-and-sustainment-industry [accessed 22 September 2020].

Note e: On 1 July 2020, Defence released the 2020 Defence Strategic Update and 2020 Force Structure Plan to outline a new Defence strategy and the capability investments to deliver it (available from https://www. defence.gov.au/strategicupdate-2020/). The 2020 Force Structure Plan builds on the Government’s continuous naval shipbuilding program as set out in the 2016 Defence White Paper. According to Defence, an update to the Naval Shipbuilding Plan in late 2020 will provide further detail on opportunities for Australia’s shipbuilding industry that result from the new plan.

SEA 1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel program

1.4 In November 2015, the SEA 1180 Phase 1 OPV program received funding approval of $11.53 million for the commencement of a competitive evaluation process8 to select a ship designer and builder for the OPV program.

Competitive evaluation process to select a ship designer and builder

1.5 The competitive evaluation process informed the advice provided by Defence to support the Government’s approvals at first and second pass.9 The agreed competitive evaluation process comprised five activities set out in Table 1.1. The timing of competitive evaluation process activities and Government approvals is summarised in Appendix 2 of this audit report (Figure A.1).

Table 1.1: Competitive evaluation process — Offshore Patrol Vessel program

|

Activity |

Purpose |

|

Analysis of Alternatives |

A market survey and analysis to down-select existing off-the-shelf ship designs that potentially met the requirements sought by Defence and the Government. |

|

Risk Reduction Design Studies |

To enable Defence to better understand the cost and schedule risks associated with making changes to the reference ship designs (base designs) of the down-selected ship designers. |

|

Request for Tender |

To request down-selected designers to submit tenders for the design and construction of the OPVs and associated support systems. |

|

Offer Definition and Improvement Activities |

To clarify and better define particular aspects of the tenders. This process sought to reduce risks and maximise value for money in order to facilitate the selection of a preferred tenderer for contract negotiations. |

|

Schedule Protection Activities |

To bring forward design work from the acquisition contract statement of work, where possible, to reduce the time required to achieve a production ready design. This was done so that the System Requirement Review, System Definition Review and Preliminary Design Review could be conducted in a timely manner after contract signature. The aim of this process was to preserve schedule and ensure construction could commence on time in 2018. |

Note: The Government endorsed, as part of the first pass approval, Defence’s strategy to undertake Risk Reduction Design Studies, Request for Tender, Offer Definition and Improvement Activities and Schedule Protection Activities concurrently during the competitive evaluation process.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.

1.6 In November 2015, the Government agreed to the essential criteria that the competitive evaluation process would use to progressively narrow the ship designer options (through a limited tender process) to be presented for second pass. The Government required that the successful ship design should:

- be buildable in Australia within program budget and starting in 2018;

- be an off-the-shelf option10 that is proven in service (defined as previously built and used in service by another navy, coast guard or in commercial shipping);

- meet Navy’s capability requirements;

- be able to accommodate communications and combat management systems compatible with Navy’s surface fleet, and comply with applicable Australian legislative and regulatory requirements;

- be based on a steel hull;

- have a maximum displacement of approximately 1,800 tonnes and a maximum length of approximately 80 metres; and

- be supportable in Australia for operation and sustainment.

1.7 The Government also required the successful ship designer and shipbuilder to:

- maximise Australian shipbuilding jobs;

- de-risk the Hunter class frigate program by maintaining jobs and the skills base at the Osborne shipyard in South Australia;

- maximise opportunities for Australian industry; and

- support implementation of the principles in the 2015 shipbuilding analysis (discussed in paragraph 1.2). The principles from that analysis to be applied were:

- rationalising the number of Australian naval shipyards to no more than two;

- selecting a mature design that is buildable in Australian shipyards;

- limiting changes to those necessary for meeting unique Australian requirements;

- sourcing designs from countries with similar naval architecture standards;

- making significant improvements in workplace productivity; and

- having a well-integrated designer, builder and supplier team.

First pass approval

1.8 On 18 April 2016, the Prime Minister and Minister for Defence announced:

- First pass approval for the Offshore Patrol Vessels, with construction to begin in Adelaide from 2018, following the completion of the Air Warfare Destroyers and transfer to Western Australia when the Future Frigate construction begins in Adelaide in 2020. This approach ensures that jobs and skills are retained in Adelaide.

- As part of the Competitive Evaluation Process three designers have been shortlisted; Damen of the Netherlands, Fassmer of Germany, and Lurssen of Germany to refine their designs.

- This program is estimated to be worth more than $3 billion and will create over 400 direct jobs.11

Second pass approval

1.9 On 24 November 2017, the Prime Minister announced the final outcome of the competitive evaluation process in a press conference:

We are building 54 naval vessels, that’s our commitment and today, we’re announcing that we have selected Lürssen as the designer and prime contractor for 12 Offshore Patrol Vessels.12

1.10 The Minister for Defence Industry further announced that the OPV program would create ‘1000 jobs across Adelaide and then 1000 jobs across Henderson.’13

1.11 On 25 November 2017, Ministers issued a joint media release announcing that:

The Navy’s OPVs will be the Lürssen design utilising ASC Shipbuilding in Adelaide for the construction of the first two ships.

The project will then transfer to the Henderson Maritime Precinct in WA where Lürssen will use the capabilities of Austal and Civmec to build ten OPVs, subject to the conclusion of commercial negotiations.14

1.12 In line with the essential criteria and requirements for the competitive evaluation process (refer paragraphs 1.6-1.7 above), Defence stated in November 2017 that the selected Lürssen OPV design:

- is based on a military off-the-shelf design15 — the Darussalam class — in service with the Royal Brunei Navy; and

- has had minimal changes made. Changes were limited to those necessary to meet Australian legislative and regulatory requirements, and specific Defence communications and situational awareness needs.16

1.13 The $3.58 billion approved acquisition cost did not include sustainment funding for the OPVs. In seeking second pass approval, Defence provided rough-order-of-magnitude sustainment cost estimates to the Government.17 Defence records indicate that the OPV sustainment strategy has been incorporated into a broader continuous sustainment model for Navy vessels and that Defence planned to return to Government to present its revised OPV sustainment strategy. Defence advised the ANAO in July 2020 that the revised strategy is expected to be provided to Government for consideration in June 2021.

1.14 The Government’s second pass approval included:

- an indicative capability transition plan involving the life-of-type extension of up to six Armidale class patrol boats and lease extension of up to two Cape class patrol boats18, at an estimated cost of $103.7 million; and

- upgrades of OPV wharves and port facilities, at a cost of $918.5 million, funded from a separate Integrated Investment Program facilities provision.

Establishment of the contract

1.15 On 31 January 2018, Defence signed a $1.988 billion (GST-exclusive) contract for the design and build of the OPVs with Luerssen Australia Pty Ltd (Luerssen), a subsidiary of Fr. Lürssen Werft GmbH & Co. KG (Lürssen).19

1.16 Luerssen subcontracted ASC OPV Shipbuilder Pty Ltd for the build of the initial two OPVs at the Osborne South shipyard (Osborne) in South Australia, and Civmec Construction & Engineering Pty Ltd (Civmec) for the build of 10 OPVs at the Henderson maritime precinct (Henderson) in Western Australia.

1.17 At the Australian Government’s request, Luerssen also entered into commercial negotiations with Austal Limited (Austal) but did not reach agreement on a role for Austal in the OPV build.

1.18 On 1 May 2020, the Minister for Defence and Minister for Defence Industry announced that Austal would build six new Cape class patrol boats for Navy under a separate $350 million build program:

The six new Cape Class Patrol Boats will grow the patrol boat force to 16 vessels20, while the new larger Arafura Class Offshore Patrol Vessels are introduced into service.

Minister for Defence, Senator the Hon Linda Reynolds CSC said the new vessels will play an important role in keeping Australia’s borders safe, while Navy’s new capability is brought online.

“These vessels will not only enhance national security, but will provide important economic stimulus and employment continuity during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Minister Reynolds said.21

Approved design of the Offshore Patrol Vessel

1.19 The OPV design is based on the existing Darussalam class ship design (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Image of the Lürssen-designed Offshore Patrol Vessel

Source: Artist impression of an OPV provided by Defence.

1.20 Figure 1.3 outlines the platform characteristics and primary systems of the approved OPV. By way of comparison, Armidale class patrol boats have a length of 56.8 metres, a beam of 9.7 metres, a displacement of 300 tonnes, a standard range of 3,452 nautical miles and a crew of 21.22

Figure 1.3: Platform characteristics and primary systems of the Offshore Patrol Vessel

Source: Department of Defence infographic.

1.21 In addition to its arrangements with two Australian shipbuilders (see paragraph 1.16), Luerssen’s Public Australian Industry Capability Plan (dated October 2018) sets out a number of other contracting arrangements with Australian industry. Table 1.2 lists the Australian companies that supply the major systems for the OPVs to Luerssen.

Table 1.2: Subcontractors supplying the Offshore Patrol Vessel’s primary systems

|

System components |

Subcontractor |

|

Propulsion engines |

Penske Power Systems Pty Ltd |

|

Main gun weapons system |

Leonardo Australia Pty Ltd |

|

Integrated platform management system, navigation and communications systems |

L3 Communications Australia Pty Ltd |

|

9LV combat management systema |

SAAB Australia Pty Ltd |

|

Accommodation |

Taylor Bros Marine Pty Ltd |

|

HVAC (heating, ventilating and air conditioning), CO2 firefighting, refrigeration and chilled water systems |

Noske-Kaeser Marine Australia Pty Ltd |

|

Electrical installation |

Marine Technicians Australia Pty Ltd |

Note a: The Government has mandated the SAAB Australia 9LV combat management system. See: Prime Minister, Minister for Defence and Minister for Defence Industry, ‘New approach to naval combat systems’, media release, 3 October 2017, available from https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/minister/marise-payne/media-releases/joint-media-release-new-approach-naval-combat-systems [accessed 22 September 2020].

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.

Administrative arrangements and expenditure

1.22 Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) is responsible for managing the acquisition of the OPVs on behalf of Navy, which is the capability owner. Navy and CASG have agreed the terms and key dates for delivery of the OPVs in a Materiel Acquisition Agreement (MAA)23 summarised in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Key dates for Offshore Patrol Vessel delivery under the Materiel Acquisition Agreement

|

Project event |

Delivery datea |

|

Initial Materiel Release for OPV 1 to Navy

|

December 2021 |

|

Initial Operational Capability for OPV 1

|

December 2022 |

|

Final Materiel Release (all 12 OPVs to be delivered)

|

December 2029 |

|

Final Operational Capability

|

June 2030 |

Note a: See Table 4.1 in Chapter 4 for a more detailed timeline on the delivery schedule of the OPVs.

Source: ANAO analysis of the Materiel Acquisition Agreement. For definitions see Auditor-General Report No.19 2019–20, 2018–19 Major Projects Report, p.viii.

1.23 As discussed, the approved acquisition cost for 12 OPVs under SEA 1180 Phase 1 is $3.58 billion, which does not include sustainment funding. As at 30 June 2020, Defence had spent $580.30 million on the OPV program.24

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.24 The OPV program is intended to enhance ADF maritime capability and is one of three interrelated components of the Australian Government’s continuous naval shipbuilding program under the Naval Shipbuilding Plan.25 The Government has identified the OPV program as having an important role in mitigating identified risks to workforce continuity at the Osborne shipyard between the end of the Hobart Class air warfare destroyer build and the commencement of the Hunter class frigate build. The Government’s requirements to split OPV construction between two shipyards under an accelerated build schedule pose a challenge to Defence in managing program risks. The audit will provide assurance to the Parliament on the effectiveness of Defence’s procurement and management of the OPV program, its ability to deliver the required capability on schedule and within budget, the workforce outcomes achieved, and the program’s contribution to delivery of the Naval Shipbuilding Plan in establishing a sovereign naval shipbuilding enterprise.

1.25 The OPV program was last examined by the ANAO in the context of Auditor-General Report No.39 2017–18 Naval Construction Programs—Mobilisation. The audit concluded that at the time of tabling (May 2018) Defence was meeting scheduled milestones to deliver the OPV program, although the program was still at an early stage. A key finding of the audit was that the design and build milestones for the OPV program were brought forward to help maintain the shipbuilding workforce from the end of the Hobart class destroyer build to commencement of the Future Frigate build. As a consequence of the compressed schedule, Defence carried several risks into the OPV acquisition. In particular, reliable sustainment cost estimates were not provided to the Government at second pass approval, and commercial arrangements between the selected shipbuilder and Australian shipbuilding firms had not been settled when the tender outcome was announced.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.26 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness to date of Defence’s procurement and contract management of the OPV program.

1.27 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Did Defence conduct an effective competitive evaluation process for the procurement of the OPVs that supported the achievement of value for money?

- Has Defence established fit-for-purpose contracting and program governance arrangements?

- Is the OPV program meeting program milestones and supporting the delivery of the Naval Shipbuilding Plan?

1.28 The ANAO did not examine:

- the sustainment strategy for the OPVs;

- the acquisition and build program for six new Cape class patrol boats announced by the Government in May 2020 (see paragraph 1.18 above); or

- contract arrangements between the prime contractor (Luerssen) and its sub-contractors.

Audit methodology

1.29 The audit methodology involved:

- review of records and data held by Defence, particularly the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group and Navy;

- site visits to the Osborne shipyard in South Australia and the Henderson shipyard in Western Australia; and

- discussions with relevant Defence personnel and contractors responsible for the OPV program.

1.30 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $510,000.

1.31 The team members were Esther Barnes, Leo Simoens, Alex Wilkinson and Sally Ramsey.

2. Platform selection

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether Defence conducted an effective platform selection process for the procurement of Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs), which supported the achievement of a value for money outcome.

Conclusion

Defence conducted a largely effective platform selection process which supported the achievement of a value for money outcome. Defence surveyed the market for an appropriate OPV design and implemented a well-documented process to select three designs for detailed evaluation. The competitive evaluation process was supported by appropriate governance, assurance and probity arrangements and a Tender Evaluation Plan that was applied consistently across the three invited tenders, to provide a basis for assessing value for money. The tender evaluation process addressed the essential criteria and requirements that the Government had set for the program. The effectiveness of Defence’s processes was impacted by the poor timing of and information access restrictions placed on a key assurance review activity, shortcomings in Defence record-keeping for the introduction of an additional condition late in the platform selection process, and Defence’s approach to advising its ministers.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving Defence’s processes for Independent Assurance Reviews and record-keeping.

2.1 To assess whether Defence conducted an effective platform selection process that contributed to the achievement of value for money, the ANAO examined whether:

- Defence established appropriate governance arrangements to support the platform selection process;

- Defence conducted an effective process to select suitable ship designers to participate in the competitive evaluation process;

- Defence conducted an effective tender evaluation process, which included an assessment of value for money; and

- Defence provided appropriate advice to the Government on the outcome of the competitive evaluation process to inform second pass approval.

Did Defence establish appropriate governance arrangements for the platform selection process?

While Defence established appropriate governance, assurance and probity arrangements for the platform selection process, the implementation of one aspect of the assurance arrangements was not fully effective. Defence established fit-for-purpose arrangements to conduct and oversight the competitive evaluation process, which included a series of steering groups and internal reviews to provide assurance to senior leaders. The reviews usefully identified issues requiring attention but in one case, the poor sequencing of the activity and the restrictions on the reviewers’ access to information compromised the effectiveness of the assurance review activity. Defence made appropriate arrangements for obtaining third-party legal and probity advice during the competitive evaluation process.

Governance and oversight of the competitive evaluation process

2.2 Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) is responsible for managing the acquisition of OPVs on behalf of the Royal Australian Navy (Navy), which is the capability owner. The Assistant Secretary Ship Acquisition – Specialist Ships26 within CASG’s Specialist Ships Branch is the Program Manager of the SEA 1180 Phase 1 OPV program.

2.3 An initial version of the OPV Integrated Project Management Plan specified that the competitive evaluation process was managed by the Director-General Specialist Ships Acquisition, who subsequently delegated authority for this activity to the Project Director of the OPV program. The Project Director is also the chair of an Integrated Project Team, which is directly responsible for delivery of the project within the scope, cost and schedule parameters approved by government at second pass.27

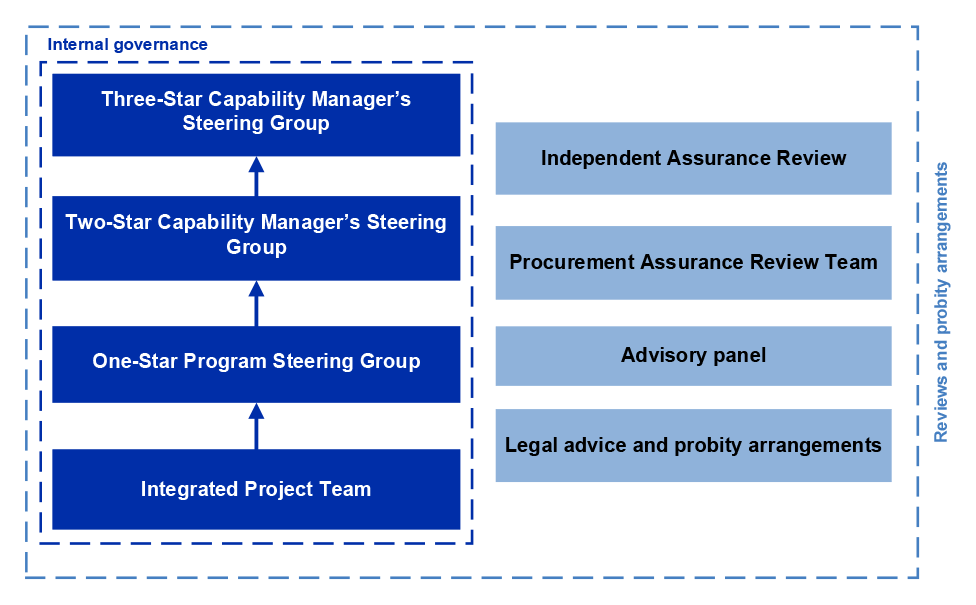

2.4 In addition to the Integrated Project Team, a One-Star Program Steering Group, Two-Star Capability Manager’s28 Steering Group and Three-Star Capability Manager’s Steering Group were established to provide advice, oversight and strategic direction on OPV program activities29, including the competitive evaluation process. The governance structure Defence adopted for the OPV competitive evaluation process is set out in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Governance structure for the OPV competitive evaluation process

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.

2.5 The terms of reference for the One-Star Program Steering Group and Two-Star Capability Manager’s Steering Group stated that their roles include the review and endorsement of relevant program documentation and business cases for clearance by higher level Defence committees, and to provide advice to higher level Defence committees to support the decision-making process. The terms of reference for the Three-Star Capability Manager’s Steering Group provide that the group is the governance body that oversees the capability transition of the OPV program and makes decisions on key program issues.

2.6 Examples of the advice and oversight provided by these groups included setting the capability requirements of the OPV and restricting changes to the reference ship designs (the respective ship design of the three designers that Defence had down-selected) to only those that were necessary for meeting essential requirements during the Risk Reduction Design Studies.30 Defence’s approach to commencing the construction of the OPVs in 2018, by seeking minimal changes to the ship design through Risk Reduction Design Studies, was endorsed by the One-Star Program Steering Group, Two-Star Capability Manager’s Steering Group and Three-Star Capability Manager’s Steering Group. In addition, these steering groups endorsed the Request for Tender approach, which restricted the tenderers’ proposed ship designs to the modified variants of their reference ship designs from the Risk Reduction Design Studies.

Arrangements to provide assurance on project delivery

2.7 Arrangements to provide Defence senior leaders with assurance on the delivery of the SEA 1180 Phase 1 OPV project have included: Independent Assurance Reviews31; the appointment of a procurement assurance review team and an advisory panel; and legal and probity advice. These arrangements are discussed below.

Independent Assurance Reviews of the competitive evaluation process

August 2015 Project Initiation / Acquisition Strategy Gate Review

2.8 In August 2015, Defence conducted a Gate Review on the project initiation and acquisition strategy of the OPV program. The review found that the Government’s requirement to commence the OPV build in 2018 was the major driver of the project, and that the schedule to second pass was considered high risk. The review board provided guidance on the development of the OPV program acquisition strategy, including approaches to consider for the Analysis of Alternatives, Request for Tender and Risk Reduction Design Studies.

2.9 One of the recommendations of the review board was that governance and oversight arrangements suitable for the high risk project be agreed and established. The review board commented that:

Project governance arrangements for this project will require careful consideration, with a need for strong oversight and effective mechanisms to resolve project issues in a timely manner. The suitability of a relatively standard one star CDSG [Capability Development Steering Group] and a three star steering group for this project needs to be considered.

2.10 Defence advised the ANAO that to address the review board’s recommendation, the governance arrangements for the SEA 1180 Phase 1 OPV program were amended to provide a weekly issues brief directly to the Head of Navy Capability (chair of the Two-Star Capability Manager’s Steering Group) during the competitive evaluation process activities occurring between first pass and second pass. Defence further advised that 61 weekly briefs were provided to the Head of Navy Capability over the period.

2.11 The review board also recommended that the project be identified as a Project of Interest.32 Defence did not consider the project to be a Project of Interest candidate and did not list it as one.

August 2016 Solicitation Independent Assurance Review

2.12 In August 2016, a Solicitation Assurance Review was conducted ‘to review the project status, outlook and readiness to continue towards release of tenders for acquisition of 12 Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPV) and associated support’. The review board noted that:

After significant discussion of the intended approach to ship building, the Board noted the need for further development work within Defence to define tender requirements in the areas of Australian Industry Content (AIC), the transition of supply chain activities to Australia and obsolescence management. The Board was advised that meeting the schedule to cut steel may compromise AIC and supply chain achievements, at least for the lead vessels. The Board considered that requirements addressing the evolution of these capabilities over the whole of the build period were essential to support the continuous shipbuilding expectation of Government and to enable costed tender responses to be provided. The Board noted the project’s intent to address this requirement in the RFT [Request for Tender].

2.13 The review board considered that ‘SEA 1180 Ph 1 is not a candidate Project of Concern’ and concluded that:

The project is proceeding to plan with respect to capability requirements definition and is likely to deliver the capability specified by Defence. It was approved by Government as high risk in the cost, schedule, materiel implementation and workforce domains and remains so …

2.14 The review board recommended that agreement be sought for the project office to be supplemented by additional staff resources to complete the Tender Evaluation Plan and Request for Tender preparation. In signing off the Independent Assurance Review outcomes, the General Manager Ships commented that:

In project terms, the 1180 Ph 1 [SEA 1180 OPV Phase 1] approach is still High Risk. There are further complexities which are being handled separately, such as the development of infrastructure …

2.15 Defence advised the Government in a May 2017 project update that it assessed the schedule risk as ‘high’.33

July 2017 Independent Assurance Review

2.16 On 17 July 2017, Defence conducted an Independent Assurance Review to ‘review the project status, outlook and readiness for Gate 2 [second pass] consideration’. This review was undertaken three days after the Source Evaluation Report34 was approved by the delegate (Director-General Specialist Ships Acquisition) but before the finalisation of the Offer Definition and Improvement Activities, which were part of the competitive evaluation process.35 The review concluded that:

The project team and Navy sponsor are in lock step on the SEA 1180 Phase 1 project. Both are to be commended on the progress achieved to date particularly the work completed through the risk reduction activities, clarity of requirements expressed through the RFT [Request for Tender] documentation, and engagement with the Designers in what has been an extremely tight timeframe driven to meet Government’s target of cutting steel in 2018.

2.17 The review found that the project had made significant progress since the August 2016 Independent Assurance Review. It also observed that information about the OPV program was restricted and inaccessible by the review team:

The restrictive approach to access to information including the Tender Evaluation Plan (TEP), Request for Tender (RFT) responses, Tender Evaluation Working Groups (TEWG) reports, Source Evaluation Reports (SER), associated cost models and schedules significantly limited the ability of the external reviewers to address these matters appropriately in the Agendum Paper. …

As you are aware the team were restricted in being able to provide any meaningful detail, even when there was no suggestion that they provide the outcomes for each tenderer. Consequently, I am not able to provide an informed independent assessment of the deliverability of this project, nor of the appropriateness of the schedule, cost and risk assessments. I do feel that this is a missed opportunity for the project given the breadth of experience of the Board Members. Furthermore, I am not sure of the value of conducting an Independent Assurance Review for Gate 2 projects that have such restrictive information access. …

Given the limitation of access to information for reviewers and the restrictions imposed on the project team and the Capability Sponsor’s ability to speak to the specifics of tender responses, particularly as they relate to cost, schedule and risk at the Board Meeting, I am not in a position to advise on the true status of the project, whether the cost estimates, schedule or risk assessments are a sound basis for progressing to Second Pass Approval, nor what more needs to be done to support the Approval Process or to enhance the actual delivery.

2.18 The review recommended that the OPV program be considered a Project of Interest. Defence did not list the OPV program as a Project of Interest.

2.19 Defence advised the ANAO that information access was restricted to protect the integrity of the competitive evaluation process, as that process had not reached an outcome at the time of the review.36 The Independent Assurance Review process is intended to provide the Defence senior executive with assurance that projects and products will deliver approved objectives and are prepared to progress to the next stage of activity. Previous ANAO audits have identified Independent Assurance Reviews and their predecessor, Gate Reviews, as providing valuable insights to Defence senior leaders.37 The timing of the review process is driven by Defence, and well–timed reviews can support the early identification of problem projects and products, facilitating their timely recovery.38

2.20 As observed in the July 2017 review report, in this case restrictions on information access represented a missed opportunity for Defence to realise the full benefits of the review activity — including in respect to the true status of the project, whether the cost estimates, schedule or risk assessments provided a sound basis for progressing to second pass approval, and what more might need to be done to support the government approval process or to enhance delivery. Commencing the review, with full knowledge that there was not the expected level of information access necessary for it to be fully effective and achieve its full benefit for the taxpayer, raises the question of whether Defence made ‘proper use’ of the public resources it directed to the review.39 To prevent avoidable conflicts of this sort and ensure the proper use and management of the public resources in its care, Defence needs to appropriately sequence and coordinate its capability acquisition and review processes.

Recommendation no.1

2.21 That Defence plan the sequencing of Independent Assurance Reviews undertaken during a platform selection process, to avoid conflicts with other processes and ensure access to all relevant information.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

2.22 Defence will improve planning and timing of Independent Assurance Reviews during a selection process to ensure the review is able to be effectively conducted with access to all information required.

Procurement assurance review team

2.23 In August 2017, Defence engaged two contractors and an APS member as a procurement assurance review team. The team’s role was to provide assurance and advice to the Deputy Secretary CASG and the Three-Star Capability Manager’s Steering Group in relation to the competitive evaluation process and to provide specialist advice to the tender evaluation team on the source evaluation outcomes and conduct of the Offer Definition and Improvement Activities. The procurement assurance review team undertook a review and reported that the Offer Definition and Improvement Activities (discussed in paragraphs 2.77 to 2.80 below) properly addressed relevant risks and issues identified in the Source Evaluation Report; and that the Offer Definition and Improvement Activity Evaluation Report fairly and defensibly reflected the combined outcomes of the detailed evaluation and the Offer Definition and Improvement Activities.

Advisory panel

2.24 In August 2017, Defence also engaged an advisory panel to conduct a peer review of the competitive evaluation process.40 The review scope included:

- the process that was followed to assess the consistency of the Source Evaluation Report, the Tender Evaluation Plan and the Request for Tender with the competitive evaluation process;

- delivery of the competitive evaluation process against the Government’s requirements to achieve build commencement in 2018; and

- alignment of the competitive evaluation process with the Naval Shipbuilding Plan, government requirements and the outcomes of the 2015 (RAND) shipbuilding analysis.41

2.25 The advisory panel found that the project ‘has generally followed the CEP [competitive evaluation process] defined by Government, with attention to traceability of requirements and evaluation criteria.’ The panel also found that the competitive evaluation process had been aligned with the Naval Shipbuilding Plan, government requirements and the principles from the 2015 shipbuilding analysis (set out in paragraphs 1.6–1.7). The panel commented that:

The key elements of the NSP [Naval Shipbuilding Plan] and the RAND Report have been incorporated into each step of the CEP [competitive evaluation process] from the AoA [Analysis of Alternatives], to the RRDS [Risk Reduction Design Studies], to the RFT [Request for Tender], to the SER [Source Evaluation Report] and they are now being further addressed as part of ODIA [Offer Definition and Improvement Activities].

2.26 The advisory panel considered the risk of achieving construction commencement in 2018 to be ‘high’, despite the project team revising the schedule risk from ‘high’ to ‘medium’ in the Source Evaluation Report.

Arrangements for obtaining legal and probity advice

2.27 Defence engaged two private law firms during the competitive evaluation process — one to provide general legal advice and the other as probity advisor. The latter reviewed documentation and provided advice on the process to ensure it was conducted in accordance with relevant probity principles.

2.28 Defence sought legal and probity advice on a range of issues, including: contracting arrangements; commercial structures for the program; and the appropriateness of tenderers lobbying or meeting with ministers and Defence executives during the process. As discussed below, Defence also sought probity advice on two identified conflicts of interest.

Probity briefings and management of conflicts of interest

2.29 The SEA 1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel Legal Process and Probity Plan, dated 3 May 2016, documented that the probity advisors should provide a briefing to all individuals involved in the procurement process on their responsibilities under the plan and other legal requirements as necessary. The probity plan also required all Defence personnel and contractors involved in the procurement process to sign a conflict of interest declaration before accessing any program information.

2.30 Defence documentation indicates that probity briefings were conducted during the Request for Tender period from March 2017 to November 2017. Defence recorded, in a probity register, attendance at these briefings and whether a conflict of interest declaration was obtained. The ANAO’s review of the probity register indicated that 184 personnel and contractors were recorded as attending the probity briefings during this period. Of those 184, Defence did not obtain a conflict of interest declaration form for four personnel and contractors (2.2 per cent). Defence advised the ANAO that three of those four personnel did not participate in the competitive evaluation process despite their attendance at the probity briefings. Defence also advised that the only person out of the four who had involvement in the Request for Tender process did sign a conflict of interest form but Defence was unable to locate it. Two of the people who submitted a declaration to Defence identified a conflict of interest. Defence sought advice from its probity advisors on these cases and established an appropriate treatment plan in each case to address the issues raised.

2.31 Defence’s approach of restricting access to tender evaluation information was not limited to the review team that undertook the July 2017 Independent Assurance Review (discussed at paragraphs 2.16–2.20 above). During the tender evaluation process, Defence declined a request from the Department of Finance (Finance) to provide it with a copy of the Tender Evaluation Plan. In May 2017 Defence42 advised Finance in writing that:

Defence considers that the Tender Evaluation Plan forms a significant part of the tender evaluation process and given the evaluation of the OPV RFT [Request for Tender] is ongoing we are unable to release the document to you at this stage. In the interests of maintaining the integrity of the tender process, and consistent with sound well established probity practices, distribution of the evaluation documents of the nature you have requested must remain limited to members of the Defence SEA 1180 Tender Evaluation Organisation at this critical stage of the process.

2.32 Defence also cited the need to manage real or perceived conflicts of interest, given that the Minister for Finance is the shareholder minister for ASC Pty Ltd, a Government Business Enterprise (GBE) and one of the nominated shipbuilders in the competitive evaluation process:

As you would appreciate Defence is rightly concerned about maintaining this integrity, as any breach has the potential to affect the process for all stakeholders involved. The integrity extends to the management of real or perceived conflicts of interest, and in the case of DoF [Finance] its relationship with ASC Shipbuilding Pty Ltd (ASC) and Australian Naval Infrastructure Pty Ltd (ANI).

Noting that ASC are involved in two of the OPV RFT [Request for Tender] responses and that ANI is likely to play a role in relation to the provision of facilities required to build the first two OPV at the Osborne shipyard in SA [South Australia], we request you address how you will actively manage the dual role with respect to the GBE’s (ASC, ANI) and advising the Minister/Department Secretary on outcomes from the tender evaluation through to Government approval at Second Pass.

Did Defence conduct an effective process to identify suitable ship designers to participate in the competitive evaluation process?

Defence conducted an effective process to select three ship designers — Lürssen, Fassmer and Damen — to participate in the competitive evaluation process. Advice to the Government on the viability of available ship designs was informed by a market study and screening process which helped Defence survey the market for an appropriate OPV design, followed by a formal assessment against three risks — capability, cost and risk to commencing construction in 2018.

2.33 Defence’s process to identify suitable ship designers to participate in the competitive evaluation process for the OPV program (known as an Analysis of Alternatives) involved:

- a market survey to identify potential ship designs; and

- the down-selection of ship designs that would be presented to government for first pass approval. The designs approved by government would be invited to tender.

Identifying available ship designs

2.34 In August 2015 Defence contracted an engineering consulting company43 to conduct a study to identify and evaluate available vessel designs for the OPV program. The purpose of the study was to provide Defence with a comparative selection of vessels to enable it to select up to three OPV designs to progress to the competitive evaluation process.

2.35 The study was undertaken in two phases — a market survey and screening, followed by detailed analysis (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Phase 1 and Phase 2 of study to identify potential ship designs

|

Phase 1: Market survey and screening |

|

|

Completed October 2015 |

Screening and risk-based assessment of 129 potential ship designs against the following criteria:

Seven ship designs progressed to Phase 2 for detailed analysis.a |

|

Phase 2: Detailed analysis |

|

|

Completed December 2015

|

The seven potential ship designs identified in Phase 1 were subject to detailed analysis against the following criteria, to allow Defence to down select up to three designs:

|

Note a: A One-Star Capability Development Steering Group reviewed BMT’s assessment results from Phase 1 and agreed on the seven ship designs to progress to detailed analysis under Phase 2.

Note b: BMT’s cost analysis was based on open source information. The cost estimates provided were high level, indicative costs of each design to enable a comparative assessment of acquisition and through-life cost.

Source: ANAO analysis of BMT documents provided to Defence.

2.36 Phase 2 involved the development of a shortlist of seven ship designs with analysis against Defence’s requirements and a risk assessment for each design. In its final report to Defence, the consultant concluded that the 20 De Julio class (Fassmer’s ship design) and Darussalam class (Lürssen’s ship design) were the most capable and lowest risk platforms. The report stated that:

Both are obvious candidates. They meet the capability requirement well, are modern designs and from well-respected sources.

2.37 The consultant also suggested possible strategies for Defence’s down-selection of a third platform. The strategies were: lowest cost; next highest capability; lowest design transfer risk; potential for a ‘box set’ (combined approach) with the SEA 5000 Future Frigate program; and existing Australian shipbuilding capacity.

2.38 Prior to conducting a limited tender process, it was sound practice for Defence to undertake a market survey and risk-based analysis. This information informed Defence’s understanding of the market of potential ship designers and designs for the OPV program.

Selection of ship designs

2.39 The purpose of the down-selection process was to identify ship designs that would proceed to the next stage of the competitive evaluation process — the Risk Reduction Design Studies. The studies were intended to enable Defence to better understand the cost and schedule risks associated with making changes to the reference ship designs (base designs) of the down-selected ship designers. To down-select the ship designs, the OPV Integrated Project Team assessed the seven potential ship designs from the consultant’s study. Its assessment and recommendations were then considered by the Defence Capability Development Steering Groups (discussed above).44

Integrated Project Team’s assessment

2.40 The Integrated Project Team’s Summary Report for SEA 1180 Phase 1 Offshore Patrol Vessel Analysis of Alternatives (19 January 2016) advised the delegate45 that the seven ship designs identified in the consultant’s study had been assessed against identified risks (these were risks to schedule achievement, capability and cost). The report also outlined the three stages of assessment undertaken:

- Stage 1: Schedule achievement risk assessment.

- Stage 2: Capability risk assessment.

- Stage 3: Capability versus cost risk assessment (to determine if cost might be a discriminator).

2.41 Figure 2.2 summarises the outcomes of the OPV Integrated Project Team’s assessment of the seven potential ship designs.

Figure 2.2: OPV Integrated Project Team’s assessment

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

2.42 As shown in Figure 2.2, the OPV Integrated Project Team assessed that the Darussalam class (Lürssen) and the 20 De Julio class (Fassmer) were the most viable designs that offered the lowest risk to schedule achievement and capability. In terms of cost46, the OPV Integrated Project Team determined that there was little difference between the ship designs considered in the consultant’s Phase 2 detailed analysis (discussed in Table 2.1). Further, it was assessed that cost was not a discriminator for the Lürssen and Fassmer vessels. The OPV Integrated Project Team stated that:

Based on Reference A [consultant’s Analysis of Alternatives Report] and Project Office analysis it is clear that the Darussalam and 20 De Julio Classes are the best candidates to participate in the RRDS [Risk Reduction Design Studies], with the other designs presenting significant risks in at least one of the risk categories.

2.43 On 19 January 2016 the OPV Integrated Project Team recommended that two designs — the Darussalam class and 20 De Julio class — be progressed in the competitive evaluation process. It stated that:

Progressing only two (2) designs to the RRDS [Risk Reduction Design Studies] would provide advantages to both project cost and schedule risk, as well as present an opportunity to develop a deeper understanding of the candidate designs.

Should a third candidate be required for the RRDS then the design selected will depend upon a discriminator or criteria determined by the steering group in order to justify the design’s inclusion in the RRDS. There is no clear standout candidate under the AoA [Analysis of Alternatives] assessment process as outlined here and at Reference A [consultant’s Analysis of Alternatives Report].

2.44 The OPV Integrated Project Team’s report to the delegate also included advice anticipating that a third option might be required. The report included the three remaining shortlisted designs that could meet Defence’s required 2018 build schedule — the Arialah class, Ship Design A and Ship Design B — for consideration. The three designs assessed as potentials for consideration as a third option all met the threshold capability requirement.

2.45 On 19 January 2016, the delegate gave approval for two ship designs — the Darussalam class and 20 De Julio class — to progress to Risk Reduction Design Studies. The delegate commented that a third option ‘is not justified unless a senior stakeholder supports the argument’.

Defence Capability and Investment Committee

2.46 Before the Defence Capability and Investment Committee47 met to consider Defence’s advice to government, the options were canvassed internally by Navy (the capability sponsor, via the One-Star, Two-Star and Three-Star Capability Development Steering Groups), Defence Contestability Division and within CASG. Issues considered as part of this process included progressing three ship design options, so as to maintain competitive tension in the process and to help manage risk.

2.47 Affordability was also an area of concern. Based on the consultant’s cost estimation, the two ship designs identified as most viable for progression in the Australian context — the Darussalam class (Lürssen) and the 20 De Julio class (Fassmer) — were both high cost options. Defence advised the ANAO that:

The Fassmer and Lürssen designs were within the IIP [Integrated Investment Program] provision but closer to the provision cap suggesting the need to ensure a low cost risk option was available that whilst presenting a higher capability risk provided greater certainty that the Industry Solicitation pre Gate 2 [second pass] would provide a viable and affordable option within the IIP [Integrated Investment Program] provision.

2.48 This process resulted in a proposal that the Defence Capability and Investment Committee present a broader range of options to the Government, to offer the opportunity for cost and capability trade-offs to be considered. It was proposed that the options to be provided for government consideration include the two ship designs considered most viable for Australian needs — the Darussalam class and the 20 De Julio class — and three further potential ship designs — the Arialah class, Ship Design A and Ship Design B.

2.49 On 22 February 2016, the Defence Capability and Investment Committee met to consider the proposed designs to be recommended to government at first pass. The Chief of Navy advised the committee that the two most viable designs for Australian needs, to be progressed through the competitive evaluation process, were the Darussalam class (Lürssen) and the 20 De Julio class (Fassmer), and that the three other options offered a range of cost, schedule and risk trade-offs. Chief of Navy also indicated that between first and second pass, trade-offs would need to be made between capability, cost and risk in order to meet the Government’s requirement to commence construction in 2018. The committee meeting outcome was agreement that:

… the proposed Darussalam (Lurssen) and 20 De Julio class (Fassmer) and the Arialah be recommended to Government as viable options for progression through the next stage of the SEA 1180 Phase 1 Competitive Evaluation Process post First Pass scheduled for May 2016 …

Advice to government at first pass

2.50 On 17 April 2016, Defence Ministers proposed that the Government approve the progression of three ship designs to the next stage of the competitive evaluation process:

- Darussalam class (Lürssen);

- 20 De Julio class (Fassmer); and

- Arialah class (Damen).

2.51 The Government was informed that the Lürssen and Fassmer designs were the most viable to meet the 2018 build schedule and capability requirements. The Government was also informed that while the two designs had a higher cost, they were likely to be affordable within the Integrated Investment Program provisions. It was further proposed that the Damen design be included as it was lower cost, while also noting that it had lower but acceptable capability in terms of Australian requirements and was a medium risk to 2018 build schedule achievement.

Government first pass approval

2.52 On 17 April 2016, the Government provided first pass approval to progress the three selected ship designers to Risk Reduction Design Studies, finalise the competitive evaluation process and develop a business case for second pass, at an approved cost of $46.6 million.

Did Defence conduct an effective tender evaluation process that supported the achievement of value for money outcomes?

Defence conducted an effective tender evaluation process that supported the achievement of value for money outcomes. The tender process was preceded by a design risk reduction process which required the three invited tenderers to refine their offers and establish the baseline ship design to be proposed in their responses to the request for tender. The tender evaluation process documented in the Tender Evaluation Plan was applied consistently across the three tenders and reporting to the delegate in the Source Evaluation Report aligned with the findings in the Tender Evaluation Criteria Reports and outlined the results of the value for money assessment. The tender evaluation process addressed the essential criteria and requirements that the Government had set for the program.

2.53 To select a preferred tenderer, Defence:

- conducted Risk Reduction Design Studies which commenced in May 2016 (prior to the Request for Tender being issued);

- issued a Request for Tender to the three shortlisted designers on 30 November 2016, with responses due by 30 March 201748; and

- conducted an evaluation of tenders against the Tender Evaluation Plan from 4 April 2017 to 30 June 2017. The Tender Evaluation Plan was finalised in March 2017 and set out the framework, criteria and process for evaluating the tenders.49

2.54 The results of the tender evaluation process were documented in Defence’s SEA 1180 Phase 1 Source Evaluation Report.

2.55 To assess the effectiveness of Defence’s tender evaluation process and whether the process supported the achievement of a value for money outcome, the ANAO examined whether Defence:

- implemented the documented tender evaluation process; and

- addressed all the essential criteria and requirements set by the Government in its evaluation of the three shortlisted designs.

Risk Reduction Design Studies

2.56 Following first pass approval, Risk Reduction Design Studies were conducted with the three shortlisted ship designers in May 2016. The purpose of the Risk Reduction Design Studies was to enable Defence to better understand the cost and schedule risks associated with making changes to the three reference ship designs (base designs) to meet essential capability requirements and mandated Australian legislative and regulatory requirements.

2.57 The Risk Reduction Design Studies required the three ship designers to refine and change only those aspects of their reference ship design that were necessary to address the essential requirements in the Threshold Requirements List. Each designer’s modified variant of their reference ship design from the Risk Reduction Design Studies became the baseline ship design to be proposed in their response to the Request for Tender.

Evaluation of tenders

2.58 Tenders were received from each of the three ship designers, who were invited to tender for: the design and construction of the vessels; and the design, development and construction or procurement of the support system components and training.

2.59 The Request for Tender required each designer to partner with an experienced Australian shipbuilder (either under a joint venture arrangement or as an approved subcontractor) to undertake the build program. The ship designers proposed the following commercial structures:

- Damen — proposed to be the prime contractor and to subcontract shipbuilding to ASC/Forgacs JV, a joint venture between ASC Shipbuilding Pty Ltd (ASC) and Forgacs Marine and Defence Pty Ltd (Forgacs).50

- Fassmer — proposed the establishment of AustalFassmer Pty Ltd, an incorporated joint venture between Austal Limited (Austal) and Fassmer Australia Pty Ltd (a wholly owned subsidiary of Fassmer Germany). AustalFassmer Pty Ltd would be the prime contractor and would subcontract design support to Fassmer Australia, and design and build of the vessels to Austal.

- Lürssen — proposed to be the prime contractor and to subcontract shipbuilding to ASC/Forgacs JV (the same joint venture supporting Damen’s bid).

2.60 The tender evaluation was conducted from April 2017 to June 2017. The process set out in the Tender Evaluation Plan included:

- screening tenders to ensure that the Conditions of Tender had been met. The conditions included minimum content and format requirements, conditions for participation, and essential requirements;

- assessing the tenders against the evaluation criteria;

- assessing the value for money offered;

- advising the delegate of the assessment outcomes; and

- conducting Offer Definition and Improvement Activities.

2.61 Defence established a Tender Evaluation Organisation, as illustrated in Figure 2.3, for the conduct of the tender evaluation. The results of the tender evaluation were consolidated into the Source Evaluation Report. The report presented the results from the tender evaluation, including an assessment of value for money, and included recommendations to the source evaluation delegate (the Director-General Specialist Ships Acquisition).

Figure 2.3: Tender Evaluation Organisation structure

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.