Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Defence’s Management of Sustainment Products—Health Materiel and Combat Rations

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to review the effectiveness of the Department of Defence’s (Defence) arrangements for delivering selected non-platform sustainment.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Non-platform products are items and supplies that do not represent weapons platforms, but are required to maintain the capability and operation of the Australian Defence Force. These can include clothing items, small firearms, health and dental equipment, and other consumables. The procurement, management and supply of these capabilities is conducted by Systems Program Offices within the Department of Defence (Defence).

2. The Health Systems Program Office (Health SPO) is responsible for the procurement and sustainment of pharmaceuticals, medical and dental equipment and consumables, and combat rations. Health SPO’s budget for sustainment in 2017–18 was $78 million.

3. In 2017, Health SPO undertook procurements for health materiel and combat rations with the resultant contracts having an estimated annual expenditure of $24 million and $26 million respectively. The approved estimated expenditure of the pharmaceuticals and combat rations contracts over a five year period is $120 million and $133 million respectively.

4. Defence’s effectiveness in delivering health materiel and combat rations was selected for audit to provide assurance over significant Commonwealth expenditure not previously subject to audit coverage as well as to provide transparency and assurance to the Parliament with regards to: the operation of sustainment Systems Program Offices; value for money in Defence’s sustainment of non-platform products; and compliance with the Commonwealth procurement rules for the areas under audit. This audit is part of the ANAO’s program of audits relating to Defence sustainment, which has included the recent ANAO Audit Report No.2 2017–18 Defence’s Management of Materiel Sustainment1—which focused on Defence wide governance arrangements for sustainment, including the strategic review of the Systems Program Offices.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s arrangements for delivering selected non-platform sustainment. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Defence has implemented effective governance arrangements for the selected Systems Program Office; and

- Defence has appropriate procurement and contract management arrangements for the selected non-platform sustainment products.

Conclusion

6. Defence’s arrangements for delivering health materiel and combat rations through the Health Systems Program Office are effective other than in the areas outlined below.

7. Defence has put in place appropriate governance, reporting and accountability arrangements for the Health Systems Program Office. Effectiveness could be improved through increased IT systems integration and revising the use of internal key performance indicators.

8. Defence’s 2017 procurement and contract management arrangements for the supply and delivery of health systems products were appropriate except Defence did not:

- meet the risk policy of the Department, comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules in relation to records management, or implement arrangements for risk and probity management consistent with the intent of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules;

- seek to negotiate a reduction in tendered prices during contract negotiations; or

- plan effectively for the transition to the new contractual arrangements.

9. Defence’s 2017 procurement arrangements for the supply and delivery of combat rations were appropriate except Defence did not:

- meet the risk policy of the Department, comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules in relation to records management, or implement arrangements for risk and probity management consistent with the intent of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules; or

- implement a performance-based contract.

10. Defence’s decision to supply freeze-dried meal components as Government Furnished Material rather than through the combat rations contract may have limited the market and impacted the achievement of value for money for the Commonwealth.

Supporting findings

Governance Arrangements and Performance Reporting

11. Defence has established appropriate reporting and accountability mechanisms for the sustainment of health materiel and combat rations. However, the reporting under these arrangements is not fully effective as not all data requirements are being met.

12. Defence has in place appropriate policies to manage the sustainment of the selected products, including a specific Health Materiel Manual. Effective implementation of these policies is hindered by Defence’s monitoring of multiple IT systems that are not linked, leading to complex workarounds and instances of duplication, redundancies or out of date data.

13. Defence has a fit for purpose framework for performance reporting and monitoring within the Health SPO but its implementation is not fully effective. Key performance indicators in the Sustainment Performance Management System are: relevant and reliable, but not complete; linkages between Defence’s internal key performance indicators and those included in the audited prime vendor contracts are limited for the new pharmaceutical contract and there are no linkages with the new combat rations contract; and the Sustainment Performance Management System does not include all indicators used to monitor health materiel. The Sustainment Performance Management System allows for performance monitoring, trend analysis and cross-product comparison, however Land Systems Division only uses the System to report on key performance indicators. Two of the five key performance indicators for health materiel reported in the Sustainment Performance Management System are consistently not met, indicating Defence should take action to remedy performance shortfalls or reconsider the indicators.

14. Risks pertaining to the sustainment of health materiel and combat rations are reported on at key committees and meetings by Health SPO. Defence has not provided evidence that key operational and change management risks faced by Health SPO have been documented in risk management or business plans or that they are being managed.

Health Systems Fleet

15. In Defence’s procurement for pharmaceuticals, medical and dental equipment and medical and dental consumables, Defence largely complied with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and most of its internal policies; however, it did not meet the risk policy of the Department, records management was not compliant with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, and Defence’s arrangements for risk and probity management were not consistent with the intent of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

16. Defence records indicate that tender information was removed from Defence’s secure system during the procurement evaluation.

17. The 2017 tender and evaluation process for pharmaceuticals, medical and dental consumables and medical and dental equipment was designed to produce a value for money outcome, including the use of an open tender process as a basis for introducing competition. Defence negotiated with the preferred tenderer on a number of issues which improved the value for money outcome for the Commonwealth but did not seek to negotiate a reduction in tendered prices.

18. Defence implemented a performance based contract, which is supported by appropriate reporting procedures and management plans. The contract provides for scheduled reviews of the prime vendor’s performance, with the first review due in early 2018. Defence did not plan effectively for the transition to the new contractual arrangements.

Combat Rations

19. In Defence’s procurement for combat rations, Defence largely complied with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and most of its internal policies; however, it did not meet the risk policy of the Department, records management was not compliant with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, and Defence’s arrangements for risk and probity management were not consistent with the intent of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

20. Defence records indicate that tender information was removed from Defence’s secure system during the procurement evaluation.

21. The 2017 tender and evaluation process for combat rations was designed to produce a value for money outcome. Defence undertook a two stage, open tender process and conducted detailed evaluation of tenders. Defence negotiated with the preferred tenderer on a number of issues, including actively negotiating a reduction in distribution costs. Defence decided to supply freeze-dried meal components itself as Government Furnished Material rather than having those components supplied under the contract as initially indicated in tender documentation. This may have limited the market and, as Defence did not negotiate a reduction in tendered prices for the relevant ration pack, impacted on the achievement of value for money for the Commonwealth.

22. Whilst the contract for the supply of combat rations sets out the requirements and standards of the products to be delivered and contains some individual delivery payment controls, Defence has not implemented a performance-based contract. The contract does not specify how performance issues will be managed, or link key performance indicators to payments.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.27

That Defence refines its performance reporting and management arrangements for health materiel and combat rations by:

- aligning key performance indicators reported on in the Sustainment Performance Management System to the prime vendor contracts; and

- making use of the full reporting functionality of the Sustainment Performance Management System.

Department of Defence response: Defence accepts the recommendation.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.63

That for future procurements which involve a new service provider, Defence develops adequate phase-in plans.

Department of Defence response: Defence accepts the recommendation.

Summary of entity response

Defence acknowledges the observations contained in the audit report on Defence’s Management of Sustainment Products – Health Materiel and Combat Rations; and agrees to the two recommendations made by the ANAO

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings and areas for improvement identified in this audit report that may be considered by entities when managing procurements.

Governance and risk management

Procurement

Transition to new contracting arrangements

Performance monitoring and reporting

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Non-platform products are items and supplies that do not represent weapons platforms, but are required to maintain the capability and operation of the Australian Defence Force. These can include clothing items, small firearms, health and dental equipment, and other consumables. In 2017–18, the Department of Defence’s (Defence) total budget for its capability sustainment program (including platform and non-platform products) is $9 474 million.

1.2 The procurement, management and supply of these capabilities is conducted by Systems Program Offices. As at December 2017, there were 62 Systems Program Offices within the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group of Defence responsible for managing the sustainment2 of 112 fleets of equipment, supplies or services, through a combination of internal work and commercial contracts. Systems Program Offices may be involved in acquiring new Defence capability, sustaining existing capability, disposing of or withdrawing capability, or all of these.

1.3 The Health Systems Program Office (Health SPO) is within the Integrated Soldier Systems Branch of Land Systems Division in Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group. The Health SPO is responsible for the procurement and sustainment of pharmaceuticals, medical and dental equipment and consumables, and combat rations. The Health SPO is also responsible for the acquisition and through life support of the Australian Defence Force replacement Deployable Health Capability through Joint Project 2060 Phase 3.3

1.4 The Health SPO’s sustainment budget for 2017–18 is: $52.7 million for medical and dental equipment, pharmaceuticals, medical and dental consumables; and $25.3 million for combat rations packs. The Health SPO manages the sustainment of over 15 000 individual items of health materiel and combat rations (referred to as ‘line items’). The breakdown of the Health SPO’s budget for 2017–18 and line items is in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: 2017–18 budget and number of line items for the Health SPO by sustainment product

|

Category |

Budget 2017–18 ($million)a |

Number of line items |

|

Medical and dental equipmentb |

18.5 |

4 539 |

|

Medical and dental consumables |

15.6 |

9 644 |

|

Pharmaceuticals, medical gases and pathology |

18.5 |

1 165 |

|

Total for health materiel (JHC01) |

52.7c |

15 348 |

|

Combat rations (CA50) |

25.3 |

90 |

|

Total |

78.0 |

15 438 |

Note a: This figure does not include any costs incurred by Defence in undertaking the management of sustainment, for example: staffing, accommodation, and other overhead costs.

Note b: This includes $6.6 million in funding for the Defence Services Agreement with Joint Logistics Command for equipment maintenance.

Note c: Total may differ due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

1.5 The provision of health materiel and combat rations in Defence is managed primarily though Materiel Sustainment Agreements. These are contract‐like arrangements that set out the level of performance and support required by the Defence Capability Manager from the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, within an agreed price, as well as the key performance indicators by which service delivery will be measured. Through the agreements, the Defence Capability Manager undertakes to supply funding and the Systems Program Office within the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group undertakes the sustainment of a specific platform, product, commodity or service.

1.6 The lead Capability Managers for health materiel and combat rations in Defence are Joint Health Command and Army Headquarters respectively.

Review and reform in Systems Program Offices

1.7 The 2015 First Principles Review4,5 recommended that each of the Systems Program Offices be examined to determine the most appropriate procurement model for delivering capability and achieving value for money.

1.8 A review of the Health SPO was conducted by an external consultant in April 2017. The review made nine recommendations. Key recommendations related to: the SPO changing its supplier engagement model to a single prime vendor arrangement6 for combat rations and multiple prime vendors for health materiel; the SPO developing a workforce planning program to increase its contract management skills; investigating the opportunity to consolidate health services; and addressing issues with existing information technology systems. The Head of Land Systems Division agreed to two recommendations, and conditionally agreed with the remaining seven.7

1.9 The majority of the recommendations are due for implementation in 2019 and 2020. The Health SPO has begun to implement one of the agreed recommendations (which is due to be implemented by mid-2018) relating to moving supplier engagement models to a single prime vendor for combat rations and to multiple prime vendors for health materiel. The transition to a new supplier engagement model is reflected in two recent prime vendor contracts Health SPO has negotiated, which are for the supply and delivery of pharmaceuticals and medical and dental consumables (discussed in Chapter 3), and the supply of combat rations and ancillary items (discussed in Chapter 4).

Audit approach

1.10 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s arrangements for delivering selected non-platform sustainment. To form a conclusion against the objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Defence has implemented effective governance arrangements for the selected Systems Program Office; and

- Defence has appropriate procurement and contract management arrangements for the selected non-platform sustainment products.

1.11 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- reviewed relevant Defence files and documentation;

- collected and analysed data relating to the contract for the provision and delivery of pharmaceuticals and medical and dental consumables, and the current retender for the combat rations pack contract; and

- interviewed key Defence personnel including: staff from the Health Systems Program Office; Joint Health Command; and Army Headquarters.

1.12 The scope of this audit includes the management of sustainment of health materiel and combat rations undertaken by Health SPO. The audit examined the following two procurements in greater detail:

- the contract for the provision and delivery of pharmaceuticals and medical and dental consumables (Chapter 3); and

- the retender for the combat rations packs and ancillaries (Chapter 4).

1.13 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $353 898.

1.14 The team members for this audit were Natalie Whiteley, Megan Beven, Sophie Gan and David Brunoro.

2. Governance Arrangements and Performance Reporting

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the effectiveness of governance arrangements for the Health Systems Program Office, focusing on: reporting and accountability mechanisms to senior management outside the Health Systems Program Office; policies, practices, and systems within the Health Systems Program Office; and performance reporting and risk management.

Conclusion

The Department of Defence (Defence) has put in place appropriate governance, reporting and accountability arrangements for the Health Systems Program Office. Effectiveness could be improved through increased IT systems integration and revising the use of internal key performance indicators.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at the Defence refining its key performance indicators in relation to health materiel and combat rations, through ensuring clear linkages to the prime vendor contracts, and making use of the full reporting functionality of the Sustainment Performance Management System.

Has Defence established effective reporting and accountability mechanisms to senior management?

Defence has established appropriate reporting and accountability mechanisms for the sustainment of health materiel and combat rations. However, the reporting under these arrangements is not fully effective as not all data requirements are being met.

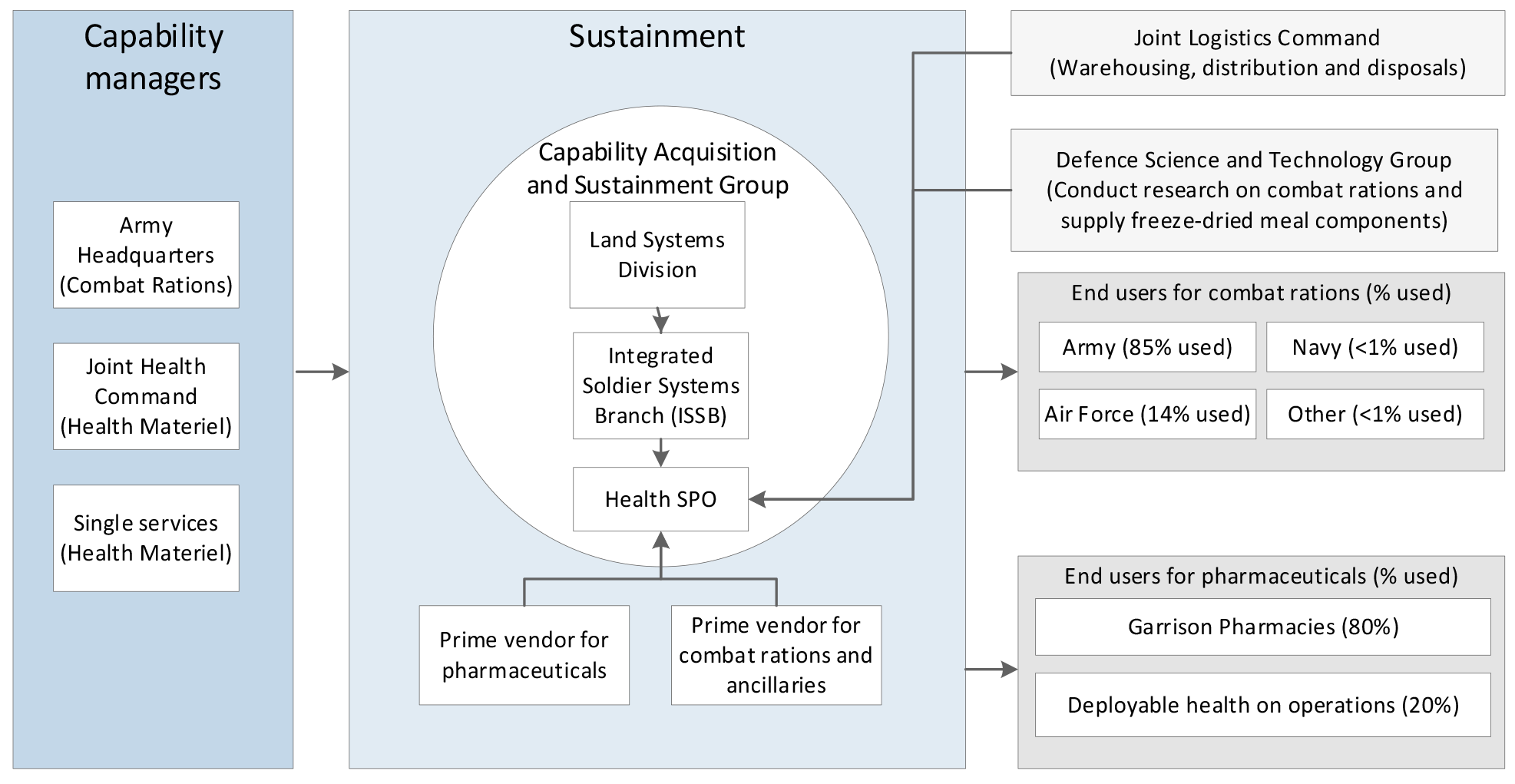

2.1 The Health Systems Program Office (Health SPO) interacts with a number of key areas in the Department of Defence (Defence) including: Joint Health Command for the health systems fleet and deployed and garrison health support8; Army for the provision of combat ration packs; and all Services for delivery and support of specific single service health requirements (for example, the incorporation of medical facilities and equipment into ships and aircraft). Figure 2.1 outlines the key areas in Defence involved in the sustainment of pharmaceuticals and combat rations.

Figure 2.1: Key areas in sustainment of pharmaceuticals and combat rations in Defence

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

2.2 The relationship between the Health SPO and the relevant capability manager is set out in Materiel Sustainment Agreements. The agreements outline the level of performance and support required by the capability manager in the sustainment of health materiel and combat rations. The Agreement includes an agreed price for the sustainment work and performance indicators by which the Health SPO’s service delivery is measured and reported.

2.3 Materiel Sustainment Agreements are divided into two sections: a Heads of Agreement which details the high level overarching agreement; and the product schedules that detail the specific agreement for the sustainment of various products. The product schedule sections of the Materiel Sustainment Agreements are reviewed annually by Defence.

2.4 To support the delivery of capability relating to health materiel and combat rations required under the Materiel Sustainment Agreements, there are a number of expert and coordinating committees in Defence (see Box 1).

|

Box 1: Committees |

|

2.5 The management of health materiel and combat rations is also considered in weekly Health SPO reports to Joint Health Command, Director General Senior Leadership Team meetings, and weekly briefing reports and talking points to the Head of Land Systems Division.9

2.6 The Health SPO provides representatives and contributes data to the above committees and reporting processes. The ANAO’s analysis of reporting by the Health SPO indicates that not all data requirements are being met, for example:

- The Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee requested data from the Health SPO to inform decisions on the management of pharmaceuticals in the Australian Defence Force. The committee’s minutes indicate that Joint Health Command and the Health SPO have had ongoing discussions over the last two years on how the committee’s data requests can be met using available resources and IT systems.

- There is partial reporting against the performance measures specified in relevant Materiel Sustainment Agreements at the Health Materiel Working Group (see paragraphs 2.15 to 2.22 for further discussion on the adequacy of performance reporting and measures for health materiel and combat rations).

2.7 Further to the above reporting, following a projected overspend in the health materiel budget (see Box 2), Health SPO began providing additional weekly reports to Joint Health Command on financial information by commodity (pharmaceuticals, consumables, medical and dental equipment) in June 2017.

Has Defence implemented appropriate policies and systems within the Health SPO?

Defence has in place appropriate policies to manage the sustainment of the selected products, including a specific Health Materiel Manual. Effective implementation of these policies is hindered by Defence’s monitoring of multiple IT systems that are not linked, leading to complex workarounds and instances of duplication, redundancies or out of date data.

2.8 The Health SPO is required to manage the sustainment of health materiel and combat rations in accordance with key Defence manuals, namely:

- The Electronic Supply Chain Manual—this manual provides an overview of the Defence supply chain including inventory management, supply purchasing, financial management and performance reporting; and

- The Defence Logistics Manual, Part 2, Volume 5—Defence Inventory and Assets—this manual outlines key roles and responsibilities in the management of Defence inventory including around logistics, funding agreements, performance management and stocktaking.

2.9 In addition, the Health Materiel Manual outlines the roles and responsibilities, processes and procedures for the management of health materiel in Defence. This comprehensive manual is reviewed every three years and includes references to relevant legislation, standards and practices for the management of health materiel.

2.10 The key IT systems used by the Health SPO in the management of health materiel and combat rations are:

- Military Integrated Logistics Information System (MILIS)—As the primary Defence logistics system, MILIS is intended to provide visibility and management of every catalogued item of supply. Deployable and deployed health facilities use MILIS to order all health materiel.

- Advanced Inventory Management System (AIMS)—AIMS is used to forecast the demand for products based on historical data from MILIS.

- Army Capability Management System (ACMS)—Army uses this system for forecasting requirements for its product schedules including combat rations.

- Pharmacy Integrated Logistics System (PILS)—Garrison pharmacy staff and authorised deployed elements use PILS to order non-exclusion list health materiel from a prime vendor. PILS can be used to: demand and receipt health materiel; support clinical functions; and provide patient medication profiles.

- Resource and Output Management and Accounting Network (ROMAN)—ROMAN is Defence’s core financial transaction system.

2.11 The prime vendor for the provision and delivery of pharmaceuticals also has an online portal, allowing Defence staff to view available stock and place online orders with the prime vendor.

2.12 The key limitations with IT systems identified during the course of the audit relate to:

- The multiple IT systems used in the sustainment of health materiel and combat rations are often not linked, creating data duplication, complex workarounds and redundant and out of date data.

- Frequent oversight is required to ensure the accuracy of data used to forecast requirements when manually transferring data from Defence’s logistic management system (MILIS) to Defence’s forecasting system (AIMS). For example, data from MILIS that is used to forecast requirements in AIMS needs to be reviewed for spikes in usage, otherwise a single order could become an annual order.

- The prime vendor’s online portal does not interface with Defence’s other system for managing pharmaceutical inventory—PILS. As a result, pharmacists at Garrison Health Centres are manually entering data from the portal to PILS. This issue is discussed further in Chapter 3 of this audit report.

2.13 The box below provides an example of the impact of IT system limitations.

|

Box 2: Example of limitations in IT systems used in Health SPO |

|

In early 2017, a projected overspend of the health materiel budget of around $4.5 million triggered an immediate reduction in activity and consumption of stock. The overspend related to the purchase of medical consumable items. Defence’s internal advice noted the overspend was in part caused by limitations in key IT systems and a lack of monitoring of these systems. In particular, a lack of appropriate oversight of relevant IT systems resulted in a purchase being made through Defence’s inventory management system based on incorrect forecasting data from AIMS, in isolation of other funding requirements. As a result of the overspend, Joint Health Command sought to reduce budget expenditure in health materiel through introducing control measures for Garrison Health Centres including filling only critical pharmacy scripts, cross levelling of consumable materiel, and drawing against stocks of consumables held in Defence warehouses. Additionally, maintenance funding for hardware equipment was restricted to essential repair for essential medical hardware and the purchase of the flu vaccine for the Australian Defence Force was staged. The minute detailing the overspend noted that:

In response to the budget overspend Health SPO and Joint Health Command agreed to a set of financial and inventory management reporting including weekly financial reporting by commodity type (pharmaceuticals, medical and dental consumables, medical and dental equipment). |

Has Defence implemented an effective performance reporting and monitoring framework within the Health SPO?

Defence has a fit for purpose framework for performance reporting and monitoring within the Health SPO but its implementation is not fully effective. Key performance indicators in the Sustainment Performance Management System are: relevant and reliable, but not complete; linkages between Defence’s internal key performance indicators and those included in the audited prime vendor contracts are limited for the new pharmaceutical contract and there are no linkages with the new combat rations contract; and the Sustainment Performance Management System does not include all indicators used to monitor health materiel. The Sustainment Performance Management System allows for performance monitoring, trend analysis and cross-product comparison, however Land Systems Division only uses the System to report on key performance indicators. Two of the five key performance indicators for health materiel reported in the Sustainment Performance Management System are consistently not met, indicating Defence should take action to remedy performance shortfalls or reconsider the indicators.

2.14 The performance reporting and monitoring framework stems from the Materiel Sustainment Agreements for health materiel and combat rations. These agreements outline the key performance indicators as well as a number of other performance measures for each area.

2.15 The key performance indicators are reported on through the Sustainment Performance Management System (SPMS) and are outlined in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Key performance indicators for health materiel and combat rations

|

Key Performance Indicators |

Green |

Amber |

Red |

Measurement source |

|

Health materiel |

||||

|

Inventory and asset demand satisfaction rate |

≥ 90 per cent |

≥ 80 per cent to < 90 per cent |

< 80 per cent |

Calculated by Inventory Measurement and Analysis Tool.a |

|

Equipment (date equipment is required) |

≤ 30 days |

30 to 45 days |

≥ 45 days |

MILIS (run by Health SPO). |

|

Availability of operational items (A) |

= 100 per cent |

≥ 90 per cent to < 100 per cent |

< 89 per cent |

Operational availability technical state as averaged each month in SPMS. |

|

Availability of operational items (B) |

≥ 95 per cent |

≥ 85 per cent to < 95 per cent |

< 85 per cent |

Operational availability technical state as averaged each month in SPMS. |

|

Percentage inside lead time for operational itemsb |

= 100 per cent |

≥ 90 per cent to < 100 per cent |

< 89 per cent |

MILIS (run by Health SPO). |

|

Combat rations |

||||

|

Demand satisfaction rate for operationsc |

100 per cent |

< 100 to 85 per cent |

< 85 per cent |

Calculated by Inventory Measurement and Analysis Tool. |

|

Demand satisfaction rate for points of entry for Army training centresd |

> 80 per cent |

< 80 to 70 per cent |

< 70 per cent |

Calculated by Inventory Measurement and Analysis Tool. |

|

Demand satisfaction rate for raise, train, sustain |

> 80 per cent |

< 80 to 70 per cent |

< 70 per cent |

Calculated by Inventory Measurement and Analysis Tool. |

|

Maintain contingency stock levels |

100 per cent |

80 to < 100 per cent |

< 80 per cent |

Stock on hand at the MILIS district as a snapshot at the time of SPMS reporting. |

|

Compliance with delivery schedule |

< 14 days |

14 to 30 days |

> 30 days |

MILIS (run by Health SPO). |

Note a: The Land Sustainment Management Directorate within the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group provides all Systems Program Offices across Land Systems Division with monthly reports from the Inventory Measurement and Analysis Tool (IMAT). The IMAT reports are a suite of AIMS inventory key health indicators including: demand satisfaction rate, inventory balance trend, requirements determination workload trend, stock on hand and excess stock trends, AIMS replenishment recommendation trend, recommended orders, purchase orders profile, and overdue redistributions.

Note b: This key performance indicator has been removed from the 2018–19 of the Materiel Sustainment Agreement following the annual review in late April 2018.

Note c: Prior to July 2017, the target for this key performance indicator was 95 per cent.

Note d: Prior to July 2017, the target for this key performance indicator was 100 per cent.

Source: Materiel Sustainment Agreement JHC01 Sustainment of Health Capability 2017–18, Module B–Capability Requirements and Measures of Success, pp. 3–4; Materiel Sustainment Agreement CA50 2017–18, Module B—Capability Requirements and Performance Indicators, p. 6.

2.16 The other, non-key performance indicator, performance measures outlined in the Materiel Sustainment Agreement are largely reported on in a variety of other forums rather than through the Sustainment Performance Management System. These forums include the monthly meeting between Joint Health Command and Health SPO, and the Health Materiel Working Group. The performance measures include:

- achievement against planned and unplanned maintenance of medical equipment managed by Joint Logistics Command under the Defence Supplier Agreement;

- planned and phased commitment and expenditure of health materiel funding for the current financial year;

- codification of health equipment10;

- timely approval, publishing, amendments and review of key documents including for end users of medical equipment, equipment schedules, engineering and maintenance plans;

- planned and phased execution of health materiel procurement plan for the current financial year; and

- the delivery of health materiel on time, in full, and in serviceable condition in response to valid demands placed by customer units, organisations and agencies.11

2.17 In addition, the Business Plan for Land Systems Division 2016–18 identifies the measures of effectiveness for the Materiel Sustainment Agreements. These measures include:

- Achieving green traffic lights against key performance indicators on the Sustainment Performance Management System.12

- Achieving within a five per cent variance on the expenditure versus the budget for the product schedule.

- Delivering 100 per cent availability for all critical platforms in accordance with the Materiel Sustainment Agreement.

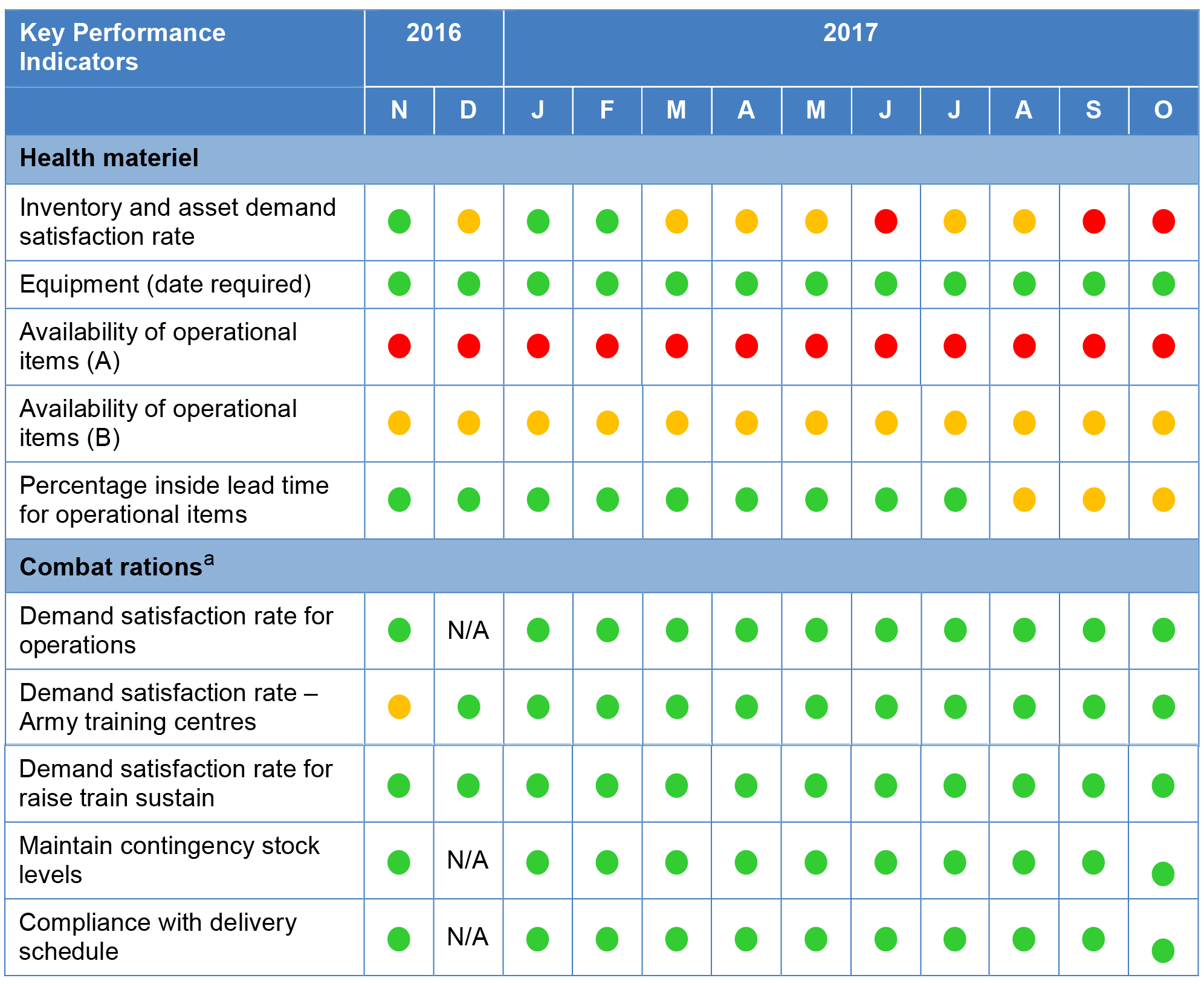

2.18 Figure 2.2 provides a summary of performance against key performance indicators as recorded in the Sustainment Performance Management System over a twelve month period.

Figure 2.2: Performance against key performance indicators as recorded in the Sustainment Performance Management System November 2016 to October 2017

Note a: Performance data for demand satisfaction rate for operations, maintaining contingency stock and complying with delivery schedules was not recorded in the Sustainment Performance Management System for combat rations for the month of December 2016.

Source: Sustainment Performance Management System.

2.19 The ANAO’s assessment of the appropriateness of key performance indicators for health materiel and combat rations found that they were relevant and reliable but not complete—as summarised in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: ANAO assessment of key performance indicatorsa for health materiel and combat rations against key characteristics

|

Characteristicb |

Health materiel assessment |

Combat rations assessment |

|

Relevant |

Yes. Each of the measures is designed to measure relevant outcomes for the sustainment of health materiel in Defence. |

Yes. Each of the measures is designed to measure relevant outcomes for the sustainment of combat rations in Defence. |

|

Reliable |

Yes. Each of the measures is reliable in that they can be objectively and readily measured, and performance can be tracked over time. |

Yes. Each of the measures is reliable in that they can be objectively and readily measured, and performance can be tracked over time. |

|

Complete |

No, because:

|

No, because:

|

Note a: The assessment relates to the key performance indicators in Figure 2.2.

Note b: These characteristics are based on the criteria developed to evaluate the appropriateness of an entity’s key performance indicators contained in Audit Report No.58, 2015–16, Implementation of the Annual Performance Statement Requirements 2015–16.

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.20 The key performance indicators identified in the Materiel Sustainment Agreements, and reported on in the Sustainment Performance Management System (listed in Table 2.1), are not aligned with the performance indicators included in the prime vendor contracts for pharmaceuticals and combat rations. For example:

- Both the pharmaceuticals contract and the Sustainment Performance Management System reporting on health materiel have key performance indicators relating to satisfying demands for inventory. However, they have different targets. The key performance indicator reported on in the Sustainment Performance Management System has a demand satisfaction target of greater than or equal to 90 per cent, while the key performance indicator in the pharmaceuticals contract has a target of 100 per cent. In addition, the key performance indicator in the Materiel Sustainment Agreement does not specify the need for ‘delivery in full’—which means the product meets specific quality standards (see Table 3.2 in Chapter 3).

- The pharmaceuticals contract includes a strategic performance measure of cost effectiveness which is a measure of the prime vendor’s ability to provide services at the best possible cost. A performance indicator for cost is not included in the health materiel key performance indicators in the Sustainment Performance Management System (see Table 3.2 in Chapter 3).

- There are no key performance indicators in the combat rations contract. There is also no explicit section in the contract regarding performance management (see paragraph 4.87 in Chapter 4).

2.21 As indicated in Figure 2.2, Health SPO has reported in the Sustainment Performance Management System that the key performance indicators for combat rations are, with one exception in the 12 month reporting period, consistently met. In contrast, the two key performance indicators regarding operational items for the Health SPO are either consistently reported as ‘red’ or ‘amber’ in the Sustainment Performance Management System. The reported underperformance is due to an inability to procure certain operational items at the 100 per cent stock level required under the key performance indicator. Defence advised that some of these items are subject to a worldwide supply shortage.

2.22 Defence informed the ANAO that there are ongoing discussions between Joint Health Command, Health SPO, and the Services regarding the key performance indicators, and how they impact on the Australian Defence Force’s ability to meet training, operational requirements, and current threat protection rules. Defence informed the ANAO in February 2018 that key performance indicators for Health Materiel will be discussed at the February 2018 Health Materiel Working Group meeting with the aim of incorporating any agreed amendments into the 2018–19 Materiel Sustainment Agreement. Defence’s review process for the 2018–19 Materiel Sustainment Agreement was completed in April 2018. ANAO’s review of the 2018–19 Materiel Sustainment Agreement found one key performance indicator—percentage inside lead time for operational items—had been removed.

Defence’s use of the Sustainment Performance Management System

2.23 The Sustainment Performance Management System is Defence’s primary sustainment reporting and performance management system.13 It is a web-based system designed to provide performance reports for Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group and Capability Managers. Data is entered monthly, usually by officers in the relevant Systems Program Office. The Systems Program Office Director reviews the data and comments for each measure and provides additional comments. Further comments can be added up the hierarchy to the relevant Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group division head.

2.24 The System can include key performance indicators and key health indicators (as defined by the Services), and also strategic sustainment analytics, or high level health indicators used for cross-platform performance analysis.

2.25 The ANAO found that the Sustainment Performance Management System was viewed favourably by Health SPO and Army and Joint Health Command as capability managers.

2.26 However, the ANAO also found that the Health SPO and relevant capability managers were not making use of the full reporting functionality of the System and that ongoing review was needed. For example:

- The System has been used inconsistently across the Systems Program Offices and across the Services. While the System allows for performance monitoring, trend analysis and cross-product comparison, some of the Services only use a limited range of the System’s functions. For example, Maritime Division (Navy) undertakes more detailed reporting than Land Systems Division, which does not report on indicators that monitor ongoing trends or allow comparison across products.

- There has been an instance where information recorded in the System was not reviewed and necessary action not taken. A contributing factor to the budget overspend noted in Box 2 was that advice to the capability manager on the System regarding the management of the budget for medical hardware was not reviewed and investigated.

Recommendation no.1

2.27 That Defence refines its performance reporting and management arrangements for health materiel and combat rations by:

- aligning key performance indicators reported on in the Sustainment Performance Management System to the prime vendor contracts; and

- making use of the full reporting functionality of the Sustainment Performance Management System.

Department of Defence response: Defence accepts the recommendation.

Has Defence undertaken appropriate risk assessment and management within Health SPO?

Risks pertaining to the sustainment of health materiel and combat rations are reported on at key committees and meetings by Health SPO. Defence has not provided evidence that key operational and change management risks faced by Health SPO have been documented in risk management or business plans or that they are being managed.

2.28 Health SPO manages two types of risks:

- risks pertaining to the sustainment of health materiel and combat rations; and

- operational risks associated with conducting its business, including changes to the Supplier Engagement Model, workforce planning and meeting Defence policy requirements.

2.29 The Materiel Sustainment Agreement product schedules identify the risks and constraints14 for health materiel and combat rations, as shown in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Risks and constraints for Health Materiel and Combat Rations as identified in the Materiel Sustainment Agreements

|

Risks and constraints |

Mitigation strategies |

|

Health Materiel |

|

|

Extant inventory and procurement procedures incur delay to the acquisition and provision of stock. |

|

|

Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group may be unable to accommodate variation and surge due to increased workload associated with unconstrained demand due to resource limitations or reductions. |

|

|

Commitment and expenditure schedule variation due to extended lead times associated with procurement. |

|

|

Technical failure of equipment, system or deficiency in compliance with technical regulatory framework. |

|

|

Long procurement lead times for medical and dental equipment and limited capacity for commercial marketplace to supply within short timeframes. |

|

|

Technology advances and changes in clinical practice contribute to short life of type for many health systems fleet items. |

|

|

Requirement to integrate equipment with ancillary components and delivery of platforms. |

|

|

Combat Rations |

|

|

Insufficient contingency holdings. |

|

|

Surge above contracted annual order. |

|

Source: Materiel Sustainment Agreement JHC01 2017–18, Module E—Product Issues, Risks and Constraints; and Materiel Sustainment Agreement CA50 2017–18, Module E—Product Issues, Risks and Constraints

2.30 These risks and mitigation strategies are discussed regularly at key committees and meetings including the Health Materiel Working Group and Health SPO Monthly Performance Meeting.

2.31 The significant change occurring across all Systems Program Offices in the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group raises some potential operational challenges and risks for Health SPO. These primarily relate to: changes to the Supplier Engagement Model—with an increase in the use of prime vendor contracts; and workforce planning—including ensuring staff are reskilled to move from transactional based work to undertaking more complex contract management roles.15 In addition, the Health SPO has also concurrently undertaken a number of large procurements, including for pharmaceuticals and medical consumables (Chapter 3), medical and dental equipment (paragraph 3.12), and combat rations (Chapter 4).

2.32 Health SPO does not have its own risk management or business plans to document and help manage its specific operational risks, as risk management in the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group is undertaken at the divisional level.16 However, the specific key Health SPO risks such as those in paragraph 2.31 are not documented in the Land Systems Division Risk Management Implementation Plan.

2.33 The management of risk relating to the procurement process for the health materiel and combat rations contracts is discussed in Chapters 3 and 4 respectively.

3. Health Systems Fleet

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Department of Defence’s (Defence) 2017 procurement and contract management arrangements for the supply and delivery of pharmaceuticals, and medical and dental consumables, were appropriate—focusing on compliance with procurement requirements, procurement design to achieve value for money, and contract deliverable outcomes.

Conclusion

Defence’s 2017 procurement and contract management arrangements for the supply and delivery of health systems products were appropriate except Defence did not:

- meet the risk policy of the Department, comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules in relation to records management, or implement arrangements for risk and probity management consistent with the intent of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules;

- seek to negotiate a reduction in tendered prices during contract negotiations; or

- plan effectively for the transition to the new contractual arrangements.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving Defence’s planning processes when new contracts are introduced.

Overview of the Health Systems Fleet

3.1 The Health Systems Fleet supports medical, dental, veterinary and ancillary health care in the Department of Defence (Defence) for both garrison and deployable environments.17 The fleet has three broad commodity groupings:

- pharmaceuticals18—items which require specialised management and handling to maximise product security, efficacy and shelf-life (for example, paracetamol, adrenaline, vaccines and anti-venoms);

- medical and dental consumables—items which are expendable and consumable (for example, surgical dressing materials, syringes and needles, diagnostic kits); and

- medical and dental equipment—items used for the diagnosis, prevention, monitoring and/or treatment of a medical condition (for example, aeromedical evacuation equipment and radiology diagnostic equipment).

New support contract for the provision of pharmaceuticals

3.2 In early 2016, Health Systems Program Office (Health SPO) undertook a procurement process for a single prime vendor to supply and deliver pharmaceuticals, medical and dental consumables and selected medical and dental equipment.

3.3 Prior to this, Defence procured pharmaceuticals and medical and dental consumables through two separate prime vendor contracts (both contracts were with the same supplier); and procured the selected medical and dental equipment as required through either a Standing Offer Panel or Request for Quotes. Warehousing, distribution and maintenance of the selected medical and dental equipment were managed through a Defence Services Agreement between Joint Logistics Command and Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group worth $6.6 million.

3.4 The extant contracts and/or standing offers for the three commodity groupings (pharmaceuticals, medical and dental consumables, medical and dental equipment) had different expiry dates. Consequently, Defence planned a staged approach to the implementation of the three separate work packages, as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Key dates in the new prime vendor contract

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

3.5 On 16 June 2017, Defence entered into a contract with a new prime vendor, Central Healthcare Services, to manage the supply, warehousing and distribution of pharmaceuticals.19

3.6 The inclusion of medical and dental consumables was scheduled for introduction under the new contract for November 2017, but has been delayed until May 2018. In the interim the extant provider will continue to deliver medical and dental consumables to Defence.

3.7 The approved estimated expenditure under the contract was $120.64 million across the initial five year period for the pharmaceutical component only. A significant proportion of the approved estimated expenditure under the contract is for non-fixed pricing and task-based services.20

Did Defence comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and relevant Defence policies?

In Defence’s procurement for pharmaceuticals, medical and dental equipment and medical and dental consumables, Defence largely complied with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and most of its internal policies; however, it did not meet the risk policy of the Department, records management was not compliant with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, and Defence’s arrangements for risk and probity management were not consistent with the intent of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

Defence records indicate that tender information was removed from Defence’s secure system during the procurement evaluation.

3.8 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules21 are the basic rule set for Australian Government procurements and govern the way in which entities undertake their procurement processes.22 To support the application of procurement related legislation and policy, Defence has established a single overarching procurement policy framework, managed by Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.23 This includes a number of compulsory activities Defence officials were required to carry out when undertaking procurement.

Planning the procurement

3.9 Defence undertook key planning activities. These included: engagement with the capability manager on key requirements; development of a procurement schedule; endorsements to proceed; and a tender evaluation plan.

Procurement strategy

3.10 Defence’s procurement strategy consisted of the Endorsement to Proceed24 which provided a high-level overview of Defence’s consideration of whether the procurement would deliver value for money. In August 2015 two work packages—pharmaceuticals (Work Package One), and medical and dental consumables (Work Package Two)—were endorsed for inclusion in the procurement. In March 2016, several days prior to the release of the request for tender, an additional work package for selected medical and dental equipment (Work Package Three) was included in the tender.25 The selected medical and dental equipment is only a small proportion of the overall medical and dental equipment procured by Defence.

3.11 The inclusion of the third work package was to allow Defence to:

assess the option to utilise the resultant contract, with the existing contractor, without the need to conduct a separate open approach to market for all or any of the products described in [Work Package Three].26

3.12 There is a separate concurrent tender activity underway by Health SPO for the procurement of the remainder of the medical and dental equipment and services Defence requires. The introduction of Work Package Three will be dependent on the outcome of this activity and decisions regarding Defence’s Randwick facility (see paragraphs 3.75 to 3.76). The relevant Endorsement to Proceed and other planning documentation (such as the Tender Evaluation Plan) contained limited information on how these two procurement processes would interact.

Risk management

3.13 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules state that:

Relevant entities must establish processes for the identification, analysis, allocation and treatment of risk when conducting a procurement. The effort directed to risk assessment and management should be commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement. Relevant entities should consider risks and their potential impact when making decisions relating to value for money assessments, approvals of proposals to spend relevant money and the terms of the contract.27

3.14 Defence’s internal Project Risk Management Manual also requires that all project risks be documented in a risk register and that staff are to update the risk assessment for a project at key decision points and milestones.

3.15 There was no documented risk management register for the procurement and Defence was unable to provide evidence to the ANAO that it established processes for the identification, analysis, allocation and treatment of risk when conducting the procurement.

Probity and conflict of interest

3.16 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules require that ‘officials undertaking procurement must act ethically throughout the procurement’, including ‘recognising and dealing with actual, potential and perceived conflicts of interest’ and the equitable treatment of participants.28

3.17 Defence also has specific instructions on managing potential conflicts of interest, which apply to Defence personnel and external service providers under contract to Defence.

3.18 In the absence of a risk management plan for the procurement, there is no evidence of specific consideration of or actions taken to ensure officials undertaking the procurement acted ethically. Defence was unable to demonstrate to the ANAO that it established processes to recognise and deal with actual, potential or perceived conflicts of interest. For example, staff involved in the procurement process, including the tender evaluation, were not required to complete conflict of interest declarations.

3.19 Additionally, Defence was unable to demonstrate to the ANAO that it established processes to ensure the equitable treatment of participants. For example, Defence did not develop a probity plan for the procurement which addressed arrangements for the provision of probity advice.29 In April 2018, Defence advised the ANAO that:

Probity advice was available throughout the procurement process from the Integrated Soldier Systems Branch Chief Contracting Officer. Ultimately, no formal request for probity advice was required. The validity of using an internal source of probity advice was confirmed orally by the Branch Chief Contracting Office in 2016, and is consistent with Defence procurement policy that states ‘there is no requirement for Defence officials to engage an external probity or process adviser’ and that ‘internal personnel (for example, contracting officers or Defence Legal officers) can potentially perform the role of a probity adviser for a Defence procurement’.

Security of tender information

3.20 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules provide that: ‘when conducting a procurement … entities should take appropriate steps to protect the Commonwealth’s confidential information’.30 The Tender Evaluation Plan stated that all tendered material should be kept secure.

3.21 Defence records indicate that tender information was removed from Defence’s secure system, and information was sent from Defence email accounts to personal email accounts of Defence staff.31 Documents potentially containing information of a sensitive nature relating to the tender and Health SPO activities that were emailed to personal accounts included:

- internal briefing material on certain vaccines;

- internal briefing material on health materiel budget concerns; and

- internal briefing material on the closure of a Defence facility responsible for warehousing, delivering and maintaining pharmaceuticals, medical and dental consumables, and medical and dental equipment (see paragraph 3.76).

3.22 In the course of the audit the ANAO advised Defence of this issue. Defence informed the ANAO in March 2018 that it had undertaken an independent32 assessment of the issue. The security incident was documented in a security report and individuals involved received formal correspondence from their senior executive officer as well as a verbal debriefing on the outcomes of the investigation.33 Defence advised the ANAO in April 2018 that: ‘the issues regarding security of tender information did not affect the conduct or outcome of the tender assessments. Tenders were not altered, as the tender had been closed.’

Approach to market

3.23 Defence adopted an open request for tender process for the procurement. The ANAO’s review of the Request for Tender documentation found that it met the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.34

3.24 Tenderers were required to tender for Work Packages One and Two, and provide a response to demonstrate their capacity and capability to provide Work Package Three.

3.25 The tender was open for applications for 13 weeks (from March 2016) to ensure ‘tenderers had adequate time to address the tender requirements and form any business arrangements that they require to ensure the submission of one tender to address all requirements sought’.35 This was compliant with the minimum time limits of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.36 Defence held an industry briefing for potential suppliers in April 2016, with the opportunity for organisations to request individual meetings with Defence.

Evaluation

3.26 Defence developed a Tender Evaluation Plan outlining the evaluation process for the procurement.

3.27 A Tender Evaluation Board was formed to conduct the evaluation of the tenders received. The Board consisted solely of Defence officials from within Health SPO, including those staff involved in the management of the extant contract. As discussed earlier in paragraphs 3.17 to 3.19, Defence was unable to provide evidence that there were probity plans or conflict of interest arrangements in place for the procurement.

3.28 The evaluation process and outcomes are summarised in Table 3.1 below. The Tender Evaluation Board considered only two of the seven tenders received to be competitive. Of the five tenders considered to be non-competitive37:

- one was not accepted due to late submission;

- one was excluded for not containing sufficient information to enable a competitive assessment and did not contain a number of key deliverables; and

- three were considered non-competitive or not exhibiting value for money and were set aside by the Tender Evaluation Board.38

Table 3.1: Tender evaluation process and outcomes

|

Process |

Description |

Outcome |

|

Registration and late tenders |

Register the receipt of all tenders, with late tenders excluded.a |

Seven tenders received, with one tender not accepted as it was received after the tender period closed. |

|

Screening |

Screen tenders, excluding tenders which did not satisfy the minimum content and format requirements from detailed evaluation. |

Six tenders screened and shortlisted:

|

|

Shortlisting |

Identify non-competitive tenders that had no reasonable prospect of exhibiting the best value for money in comparison to other tenders received. Tenders that were identified as non-competitive were not considered for detailed evaluation. |

|

|

Detailed evaluation |

Detailed evaluation to assess tender deliverables against the requirements of the request documentation, producing analysis and comparative assessment of each tender against the evaluation criteria. Each tender would also undergo a value for money assessment. Tenders were assessed as preferred and non-preferred. |

Five tenders underwent detailed evaluation, with:

|

Note a: The Commonwealth Procurement Rules specify late tender submissions must not be accepted, unless the submission was late as a consequence of mishandling by the relevant entity.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

3.29 The detailed evaluation against the evaluation criteria39 was performed by each of the Tender Evaluation Working Groups and reported to the Tender Evaluation Board. The Tender Evaluation Board then assessed the tenderers’ overall compliance and the level of risk of each tender against the requirements and ranked them accordingly.40 Tenders were provided with an overall ranking based on these assessments.

3.30 According to the Tender Evaluation Plan the evaluation of tenders was anticipated to have been completed by 15 August 2016 and approved by the delegate by 1 September 2016. The evaluation of tenders was completed on 30 November 2016 and approved by the delegate in December 2016.

Evaluating prices and pricing structure

3.31 As a requirement of the tender, in addition to providing recurring service fee costs, tenderers were asked to provide information on how they would price product and delivery costs for both Work Package One and Work Package Two. Defence did not require a tendered price for Work Package Three, as noted in the Endorsement to Proceed:

Due to the limited information that will be provided in the release documentation on [Work Package Three] content, the Commonwealth will not seek or evaluate tenderers’ offers regarding price or delivery rates. Detailed evaluation will be limited to an assessment of tenderers ability and managerial capability to supply products within the categories identified in [Work Package Three] and associated risk assessment.

3.32 To ‘obtain consistency across responses to facilitate evaluation’, tenderers provided cost information for 605 pharmaceutical items and 670 medical and dental consumable items against Defence’s estimated requirements.41

3.33 In evaluating prices and pricing structure, Defence undertook a compliance and risk rating for each tender. Defence also assessed and compared each tender on:

- the pricing structure and tendered prices for a sample of 475 pharmaceutical items42;

- the pricing structure for medical and dental consumables;

- recurring service fee costs; and

- delivery costs.

3.34 There was no assessment or comparison between tenderers for the tendered prices for medical and dental consumables (Work Package Two), with the Tender Evaluation Working Group advising that, whilst ‘the evaluation of pharmaceuticals was achievable due to the use of industry based identification numbers’, there were ‘significant levels of complexity to the evaluation of the [medical and dental consumables] items due to the inability to match like-for-like items due to varying descriptions’.

3.35 In the assessment of the pricing structures, Defence assessed that pricing structures which fixed prices annually and were required to be re-negotiated each year presented limited flexibility and increased risk to the Department. This is because pricing reductions or increases would not be passed on in real time, and imposed ‘an administrative task on the parties which is unlikely to provide the Commonwealth with cost comparative saving’. Defence instead opted for the preferred tenderer’s cost mark-up model, which Defence assessed as ‘consistent with the [Request for Tender] pricing model, which seeks to take advantage of market fluctuating pricing’.

3.36 The preferred tenderer did not have the lowest tendered price compared to other tenderers. The preferred tenderer was ranked higher as it was considered to have a lower risk pricing structure as well as lower recurring service fees. Additionally, advice to the delegate noted that a comparison with the preferred tenderer’s tendered prices and the current general product price list with Defence offered an average cost saving of 1.5 per cent.

Australian Industry Capability Plans

3.37 Consistent with Defence policy, Australian Industry Capability43 plans were required to be submitted as part of tender responses.

3.38 In evaluating tenders responses the Tender Evaluation Board found all responses were ‘deficient to various degrees’ with the relevant Tender Evaluation Working Group, noting that ‘they will take a lot of work to reach compliance, even the marginal ones’.

3.39 The Tender Evaluation Board agreed that ‘no tender response would be ranked’ and that ‘every tender was assessed as similar … due to the restrictions placed by legislation and the tender process did not identify any significant [Australian Industry Capability] within any offer’. The Tender Evaluation Board noted ‘that the [Australian Industry Capability Plan] would need to be developed as part of the negotiation stage with the preferred tenderer’.

3.40 During negotiations Defence and the preferred tenderer reached agreement that the preferred tenderer would amend its plan by the contract effective date and that it would continue to evolve for the duration of the contract. An Australian Industry Capability Plan was included in the resultant contract.

Records management

3.41 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules require that ‘officials must maintain for each procurement a level of documentation commensurate with the scale, scope and risk of the procurement’.44 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules note this should include, for example, the process that was followed, how value for money was achieved and relevant decisions and the basis for those decisions.

3.42 Defence maintained records of key documentation for the procurement; however, there are instances where there was insufficient documentation to assess some of the processes that were followed, some of the relevant decisions made, and/or the basis for some of the decisions, namely:

- correspondence and/or communication with potential suppliers, tenderers and suppliers;

- no record of any directive from the delegate on the inclusion of the medical and dental equipment in the procurement; and

- minutes, directives and working documents for meetings of the Tender Evaluation Board and some relevant Tender Evaluation Working Group reports.

Were Defence’s procurement arrangements designed to achieve value for money for the Commonwealth?

The 2017 tender and evaluation process for pharmaceuticals, medical and dental consumables and medical and dental equipment was designed to produce a value for money outcome, including the use of an open tender process as a basis for introducing competition. Defence negotiated with the preferred tenderer on a number of issues which improved the value for money outcome for the Commonwealth but did not seek to negotiate a reduction in tendered prices.

3.43 Achieving value for money is the core rule of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.45

3.44 Defence adopted an open tender process for the procurement, as a basis for introducing competition and contributing to value for money outcomes.

3.45 In advice to the ANAO, Defence commented that ‘despite the large annual budget, Defence is considered by industry to be a relatively small customer with a consumption rate for health products similar to a large city based hospital.’ Defence considered that the option to consolidate the services and items contained in the three work packages under one contract would increase the commercial attractiveness of supplying these services and items, ‘potentially increasing cost savings and streamlining the requirement’. Defence advised the ANAO that, as a result of the consolidation, ‘a number of major providers to the healthcare industry responded [to the request for tender], which has not been the case for previous [tenders] of this nature’.

3.46 Consistent with the First Principles Review, Defence also aimed to reduce transactional and administrative overheads by reducing its involvement in the supply process. For example, Defence sought direct order placement by its pharmacists with the prime vendor. Defence did not estimate or undertake analysis of the potential savings that may be delivered to government as a result of these changes.

3.47 Defence also sought a value for money solution by broadening the pharmaceuticals that the prime vendor would be required to supply to a ‘full range of pharmaceutical[s] and medicines’.46 The previous contract was limited to the current, approved formulary list47 which Defence identified as contributing to ‘large administrative overheads’ when changes to the formulary were made.48

3.48 As noted in paragraph 3.35, Defence considered the tenderers’ pricing structures in the tender evaluation. Consistent with broadening the items to be supplied, for task-based services, Defence gave preference to a formula based costing method applied across the full range of requested items, over a fixed-price model negotiated annually.

3.49 In evaluating price tenders, Defence did not explicitly consider the pricing model for the supply of Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme items. Defence informed the ANAO in February 2018 that the open tender ensured the best price possible and that a ‘desktop scan only of [Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme] pricing was taken from the Department of Health [Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme] Website … to provide a high level comparison’.

3.50 The resultant contract includes arrangements for the pricing of Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme items. Items with a cost price to the provider of $930 or greater will have a flat rate mark-up of $69.94 (before applying any supplier funded discounts).49 Defence informed the ANAO in February 2018 that the $930 threshold resulted from the preferred tenderer’s offer and contract negotiation. These amounts are set under the Pharmaceuticals Benefits Scheme as listed on the Department of Human Services website.50

Contract negotiations

3.51 In January 2017, around four months behind the original schedule, Defence commenced negotiations with the preferred tenderer. Defence’s negotiation strategy identified several issues to be resolved during negotiations, but Defence did not plan to negotiate a reduction in tendered prices during negotiations phase. Even relatively small price savings achieved through negotiation could have delivered overall savings to the Commonwealth.51

3.52 Advice to the delegate noted that, in all issues negotiated, Defence achieved its preferred or minimum fall-back position.

3.53 The delegate approved the provision of the contract to the preferred tenderer in May 2017. The contract was signed on 16 June 2017, approximately six months after the original planned date. As a result of the delay, the extant provider—whose contract expired in December 2016—continued to supply pharmaceuticals to Defence as per their contractual requirements.52

3.54 The contract notice was published on AusTender on 1 August 2017 (46 days after contract signature), which is above the Commonwealth Procurement Rules requirement of 42 days.53

3.55 Regarding possible savings from the contract, advice to the delegate noted that:

Compared to the extant Contract costs of $18.3 [million] annually, subsequent information provided through the tender evaluation and negotiation process has borne possible savings of $2.9 [million] equating to a potential 15.94 [per cent] savings of contracted costs.

3.56 Defence documentation indicates that the calculation of the $2.9 million in savings was based on a comparison of the extant contractor’s fixed-price contract costs (such as management fees, delivery charges, progress meetings, and warehousing costs) and that proposed by the preferred tenderer for the first year only.

Are Defence’s contract deliverables provided to the required standard, within the agreed budget and timeframes?

Defence implemented a performance based contract, which is supported by appropriate reporting procedures and management plans. The contract provides for scheduled reviews of the prime vendor’s performance, with the first review due in early 2018. Defence did not plan effectively for the transition to the new contractual arrangements.

Management of transition arrangements

3.57 The contract was phased in with around two weeks between contract signature and the contract’s operative date, 3 July 2017. The contract with the new prime vendor, Central Healthcare Services, included information on the requirements and responsibilities of the transition as well as the implementation of subsequent work packages. Defence did not seek or receive a documented phase out plan as required under the extant contract. Additionally, Defence did not develop its own broader plan to manage the transition to the new contract, nor did it conduct a risk assessment to identify and mitigate risk.54

3.58 Defence pharmacists received three working days’ notice of the transition to the new contract, receiving advice from Health SPO on Thursday 29 June 2017 that the ‘go live’ date for the new contract and online ordering was Monday 3 July 2017.55 In addition, limited information was provided to pharmacists on the arrangement for placing orders (pharmacists were required to have additional software installed on their computers to enable them to order stock through the new prime vendor’s portal).

3.59 There were several issues identified by Defence with the phase in of the contract56, including:

- the duplication of processes for ordering pharmaceuticals as relevant IT systems were not integrated57;

- insufficient stocks of common medication (for example, paracetamol);

- problems with the delivery of medication (for example, couriers not having access to closed Defence bases);

- unclear procedures on returning medication supplied by the previous prime vendor; and

- problems with the ordering of pharmaceuticals by generic names rather than brand names and consequently receiving unintended products (for example, variations in the number of items per packet; different expiry dates; constantly switching the brands of pharmaceuticals a single patient uses, potentially introducing the risk of reduced medication compliance).

3.60 Defence advised the ANAO in November 2017 that:

Defence is meeting with (the prime vendor) on a weekly basis to resolve minor teething issues identified in the implementation. Defence is expected to meet with (the prime vendor) and [Joint Health Command] in (early 2018) to go over a lessons learnt activity to ensure we have a smooth transition of medical and dental consumables in May (2018).

Transition to subsequent Work Packages

3.61 As specified in the contract, the planned commencement date for Work Package Two—the medical and dental consumables component—was 14 November 2017 when the extant provider’s contract expired. In late 2017, Defence delayed the introduction of the work package until May 2018. This was to ensure the new prime vendor is ‘able to deliver [Work Package Two] without compromising [Work Package One]’.

3.62 In the interim, the extant prime vendor will continue to deliver medical and dental consumables through a six month contract extension worth up to $7.39 million.58 There is an additional cost to Defence for this extension, as the fixed-price component under the extant provider is higher than under the new contractual arrangements. This extension was approved by the relevant delegate.

Recommendation no.2

3.63 That for future procurements which involve a new service provider, Defence develops adequate phase-in plans.

Department of Defence response: Defence accepts the recommendation.

Management of budget

3.64 The new support contract had an estimated average annual expenditure of $24.13 million per year. Only 1.7 per cent of this estimated expenditure is classified by Defence as having certainty in terms of scope and cost. For example, while monthly administrative fees are known, the consumption of health items can only be estimated.

3.65 Following recent issues with the management of the budget for health materiel (discussed in Box 2) Defence has implemented additional weekly reporting by Health SPO to Joint Health Command to monitor actual expenditure against the allocated budget.

3.66 Defence documentation indicates that the delay in the introduction of medical and dental consumables (Work Package Two) component of the contract has increased pressure on the annual budget and will reduce the funds available for task-based services. Defence advised the ANAO that ‘any pressure on the annual budget is being managed within the governance framework established for [health materiel]’.

Management of contract deliverables

3.67 Health SPO is responsible for contract management and ensuring that the provider meets the contractual obligations, including ensuring that contract deliverables are provided to the required standard, within the agreed budget and timeframes.