Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Defence’s Management of its Projects of Concern

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess whether the Department of Defence’s Projects of Concern regime is effective in managing the recovery of underperforming projects.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Department of Defence’s (Defence) Projects of Concern regime was established as a framework to manage the remediation of underperforming materiel acquisition projects. The objective of the regime is:

to remediate the project by implementing an agreed plan to resolve any significant commercial, technical, cost and/or schedule difficulties. Projects of Concern receive targeted senior management attention and must be reported regularly to the government.1

2. Of the 25 projects listed as Projects of Concern since 2008, Defence has cancelled two of these projects and returned most of the remainder to normal management arrangements. The period spent by individual projects on the list has ranged from a few months to over eight years. Thirteen are reported to have reached Final Operational Capability.2 As of December 2018, there were two projects on the Projects of Concern list.3

3. Entry to the Projects of Concern list, and exit from it, is decided by ministers. For most of the history of Projects of Concern, Defence has used specific criteria to provide a basis to recommend that a project be placed on the list. From 2017, a set of principles has been followed rather than specific criteria.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The reason for undertaking the audit is that Projects of Concern include projects that contribute substantial capability to the Australian Defence Force and involve a major resource commitment by the Australian Government. As a mechanism for resolving difficulties with Defence projects, there is a clear link between the effectiveness of the Projects of Concern regime and Defence’s strategic priorities as stated in one of its purposes under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act): ‘Deliver and sustain Defence capability and conduct operations’.4 Further, the Projects of Concern regime regularly receives Parliamentary attention and this audit is intended to provide insight into how Defence operates and manages the Projects of Concern regime, comprising the small number of projects requiring an increased level of management and support.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit is to assess whether Defence’s Projects of Concern regime is effective in managing the recovery of underperforming projects. The following high-level criteria were adopted for the audit:

- Defence has established an appropriate framework for the Projects of Concern regime, including processes for the entry, management and exit of projects.

- Defence applies the Projects of Concern regime with an appropriate degree of consistency.

- Defence has established appropriate internal and external reporting arrangements on the progress of Projects of Concern.

- Defence can demonstrate that the Projects of Concern regime contributes materially to the recovery of underperforming projects and products.

Conclusion

6. While the Projects of Concern regime is an appropriate mechanism for escalating troubled projects to the attention of senior managers and ministers, Defence is not able to demonstrate the effectiveness of its regime in managing the recovery of underperforming projects. Defence remains confident of the regime’s effectiveness but its confidence is based on management perception and anecdotal evidence, as it has not attempted any systematic analysis. Over the last five years, the transparency and rigor of the framework’s application has declined.

7. Defence no longer has an appropriate framework for its Projects of Concern regime. The regime has two clear purposes: to resolve troubled capability development projects through remediation or cancellation with the explicit involvement of ministers; and to help keep ministers informed. However, its current implementation lacks rigour. From 2008 forward, ministers’ involvement heightened the focus on troubled projects and strengthened the regime. It was more fully developed in 2011, with the introduction of regular summit meetings chaired by ministers to review progress and stimulate action. Over the last five years, transparency has reduced, the level of formality has declined with explicit criteria replaced by unpublished principles, and processes have become less rigorous with a greater emphasis on maintaining relationships with industry.

8. There has been inconsistency in Defence’s application of its Projects of Concern regime. In particular, application of processes for entry onto the list have been inconsistent and summit meetings to address Projects of Concern have become less frequent. Greater consistency has been maintained in preparing remediation plans and removing projects from the list, though there have been exceptions to both.

9. Defence reporting on its Projects of Concern is appropriate, with regular reports provided to senior management within Defence, to ministers and to Parliament, as part of Defence’s Quarterly Performance Report. Reporting provides useful quantitative and qualitative data though Defence has acknowledged that the timing and quality of its Quarterly Performance Reports could be improved.

10. Defence has not evaluated its Projects of Concern regime over the decade it has been in place, nor set criteria for assessing success. There is no basis, therefore, for Defence to show that the Projects of Concern regime contributes materially to the recovery of underperforming projects and products.

Supporting findings

The framework for the Projects of Concern regime

11. The Projects of Concern regime has a clear purpose and scope. Its purpose is to help keep senior Defence leaders and ministers informed of materiel acquisition projects in difficulty and resolve problems in the project’s progress either through remediation or, where that is not practicable, cancellation. The regime has applied almost exclusively to underperforming materiel acquisition projects. Despite running in parallel for almost two decades, Defence has only recently sought to align its contractor performance data across its Performance Exchange Program and the Projects of Concern regime to ensure that views on contractor performance are consistent.

12. Defence has established a policy for its Projects of Concern regime and procedures for the entry, management and exit of projects. In 2009 and 2011, Defence’s approach was made more formal and rigorous at the instigation of ministers. In recent years, the transparency and formality of the process have diminished, regular summits chaired by ministers have been replaced by ad hoc meetings, and Defence no longer publishes its principles and procedures for Projects of Concern. Maintaining collaborative relationships with industry has become a more dominant element in the governance of the regime.

Application of the Projects of Concern regime

13. Defence does not apply a consistent process to the entry of projects to the Projects of Concern list with evidence of delays as well as advice being withheld from review processes and decision-makers. Procedures for Independent Assurance Reviews do not explicitly mention Projects of Concern even though such reviews are the primary occasion for nominating a project to be a Project of Concern. There was evidence that most reviews (75 per cent) had considered whether a recommendation should be made.

14. Broadly, Defence has applied a consistent process to the management of projects while on the Projects of Concern list. However, summit meetings involving the Minister, vendors and officials, a principal process devised in 2011 to help ensure that Defence can use its Projects of Concern regime to exert commercial pressure on vendors, are no longer regular and they have become less frequent. Another long-standing process, the preparation of remediation plans, has usually been followed.

15. Defence has generally applied a consistent process to the exit of projects from the Projects of Concern list. Defence’s practice has been to recommend removal of a project from the list only when it has both fulfilled a specified set of expectations (or removal criteria) and satisfied Defence that it is on a sound trajectory, making it unlikely to return to the list. A 2018 decision to remove a project (CMATS) has not observed the second condition.

Reporting on Projects of Concern and evaluating the regime

16. Regular reports are provided on Projects of Concern to senior management within Defence, to ministers and to Parliament which contain useful quantitative and qualitative data. Projects of Concern are also reported on publicly through Defence’s Annual Report and ministerial media releases. Defence has acknowledged that the quality of the data could be improved and that information technology systems have affected the timeliness of the reports. Notwithstanding its regularity, the reporting is not timely, taking nearly two months to complete.

17. Defence cannot demonstrate that the Projects of Concern regime contributes materially to the recovery of underperforming projects. Although Defence has consistently stated that its Projects of Concern regime is ‘one of the Department’s most successful management tools for recovering problem projects’ it has not evaluated the regime and this view is based on management perception and anecdotal evidence.

Department of Defence’s response

18. The proposed report was provided to the Department of Defence. The Department’s summary response is below and its full response is at Appendix 1.

Defence maintains that the Projects of Concern regime is a significant material factor, and a strong commercial lever to influence the positive recovery of underperforming projects and products.

Defence considers that the ANAO’s analysis and overall conclusion contained in the Proposed Report do not appropriately consider the evolving nature of the Projects of Concern regime, its role within the larger project management toolkit, and elevation of priority for attention by the Minister/Government of the day.

Defence does not agree with the ANAO’s statements inferring that it has avoided adding to the Projects of Concern list in the interest of trying to maintain a positive relationship with industry, nor has this resulted in a less robust governance arrangement. The reduction in the number of projects on the Project of Concern list is linked to the changing nature of the Capital Equipment Program as well as the close out of legacy projects.

Nevertheless, Defence acknowledges that there is room to enhance the administrative arrangements supporting this program and has agreed to both recommendations.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 3.29

Defence introduce, as part of its formal policy and procedures, a consistent approach to managing entry to, and exit from, its Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern lists. This should reflect Defence’s risk appetite and be made consistent with the new Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group Risk Model and other, Defence-wide, frameworks for managing risk. To aid transparency, the policy and the list should be made public.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 4.32

Defence evaluates its Projects of Concern regime.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Risk management

Governance and program evaluation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Defence established its Projects of Concern regime to manage the remediation of underperforming projects. The objective of the regime is:

to remediate these projects by implementing an agreed plan to resolve any significant commercial, technical, cost and/or schedule difficulties. Projects of concern receive targeted senior management attention and must be reported on more regularly to the Government.5

1.2 The Projects of Concern process is essentially a risk identification and management process which is intended to escalate troubled projects to the attention of senior managers and ministers.6 Defence states:

The Projects of Concern regime is a proven process for managing underperforming capability projects at a senior level. Once a project is listed as a Project of Concern, the primary objective of the regime is to remediate the project by implementing an agreed plan to resolve any significant commercial, technical, cost and/or schedule difficulties. Projects of Concern receive targeted senior management attention and must be reported regularly to the government.7

1.3 The Projects of Concern regime is managed by Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG which was formally known as the Defence Materiel Organisation). As of 30 September 2018, CASG had responsibility for the management of 117 major acquisition projects and 110 sustainment projects.

The Projects of Concern list

1.4 Since 2008, when the Projects of Concerns list was made public8, there have been 25 Projects of Concern in total. The list has included some of the most significant capital equipment projects and sustainment products in the portfolio, such as the Air Warfare Destroyer build, the Multi-Role Helicopter (MRH90) acquisition and the sustainment of the Collins Class Submarine fleet.9 As of December 2018, there were two projects on the Projects of Concern list — the Multi-Role Helicopter (MRH90) acquisition and the deployable air traffic management system.

1.5 Of the 25 projects listed as Projects of Concern since 2008, Defence has cancelled two of these projects and returned most of the remainder to normal management arrangements. Thirteen are reported to have reached Final Operational Capability.10 A complete list of projects that have appeared on the list since 2008 is set out in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Projects of Concern, from 2008 forward

|

|

Project |

Entry and exit dates |

Elapsed time on list from January 2008 |

Final Operational Capability |

|

1 |

SEA 1411 — ANZAC Ship Helicopter Project (Super Seasprite helicopter) |

Jan. 2008 – March 2008 |

2 months |

Cancelled, March 2008 |

|

2 |

abAIR 87 — ARH Tiger Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter |

Jan. 2008 – April 2008 |

3 months |

14 April 2016 |

|

3 |

aLAND 106 — M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier Upgrade |

Jan. 2008 – May 2008 |

4 months |

19 December 2014 |

|

4 |

aSEA1390 Phase 2 — Guided missile frigate (FFG) upgrade |

Jan. 2008 – Jan. 2010 |

2 years |

3 June 2016 |

|

5 |

aAIR 5416 Phase 2A — Rotary Wing Electronic Warfare Self-Protection, Project Echidna |

Jan. 2008 – July 2010 |

2 years and 6 months |

1 January 2010 |

|

6 |

acJP 2043 — High Frequency Communications Modernisation |

Jan. 2008 – June 2011 |

3 years and 5 months |

Not yet reached. |

|

7 |

aAIR 5333 — Air Defence Command and Control System ‘Vigilare’ |

Jan. 2008 – June 2011 |

3 years and 5 months |

19 December 2012 |

|

8 |

abSEA 1448 Phase 2A/2B — ANZAC-class Anti-Ship Missile Defence (ASMD) |

Jan. 2008 – Nov. 2011 |

3 years and 10 months |

Not yet reached. |

|

9 |

acAIR 5077 Phase 3 — Wedgetail, Airborne Early Warning and Control Aircraft |

Jan. 2008 – Dec. 2012 |

4 years and 11 months |

26 May 2015 |

|

10 |

aJP 2070 — Lightweight Torpedo Replacement Program |

Jan. 2008 – Dec. 2012 |

4 years and 11 months |

25 September 2013 |

|

11 |

JP 2048 Phase 1A — LPA Watercraft |

July 2008 – Feb. 2011 |

2 years and 7 months |

Cancelled |

|

12 |

JP 0129 — Tactical Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

June 2008 – Dec. 2011 |

3 years |

31 August 2014 |

|

13 |

JP 2088 Phase 1A — Air Drop Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat Trailers |

July 2008 – Sept. 2009 |

1 year and 8 months |

No FOC declared. Materiel Capability Acceptance 29 March 2010 |

|

14 |

bLAND 121 — Overlander, Medium and Heavy |

July 2008 – Dec. 2011 |

3 years and 11 months |

Not yet reached. Current forecast: 31 December 2023 |

|

15 |

CN10 — Collins Class Submarine Sustainment |

Nov. 2008 – Oct. 2017 |

8 years and 11 months |

[In sustainment — Not applicable] |

|

16 |

cAIR 5402 — Air to Air Refuelling Capability |

Feb. 2010 – Feb. 2015 |

5 years |

1 July 2016 |

|

17 |

cAIR 5418 — Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) |

Nov. 2010 – Dec. 2011 |

1 year |

20 January 2014 |

|

18 |

AIR 5276 — AP-3C Electronic System Measure System Upgrade |

Oct. 2010 – April 2014 |

3 years and 7 months |

6 May 2016 |

|

19 |

bAIR 9000 Phases 2/4/6 — MRH90 Multi Role Helicopters |

Nov. 2011 – [continuing] |

> 7 years and 1 month |

Not yet reached. Current forecast: Dec 2021 |

|

20 |

LAND 40 Phase 2 — Direct Fire Support Weapon |

Dec. 2012 – April 2016 |

3 years and 4 months |

13 April 2018 |

|

21 |

JP 2086 Phase 1 — Mulwala Redevelopment Project |

Dec. 2012 – April 2017 |

4 years and 4 months |

15 December 2016 |

|

22 |

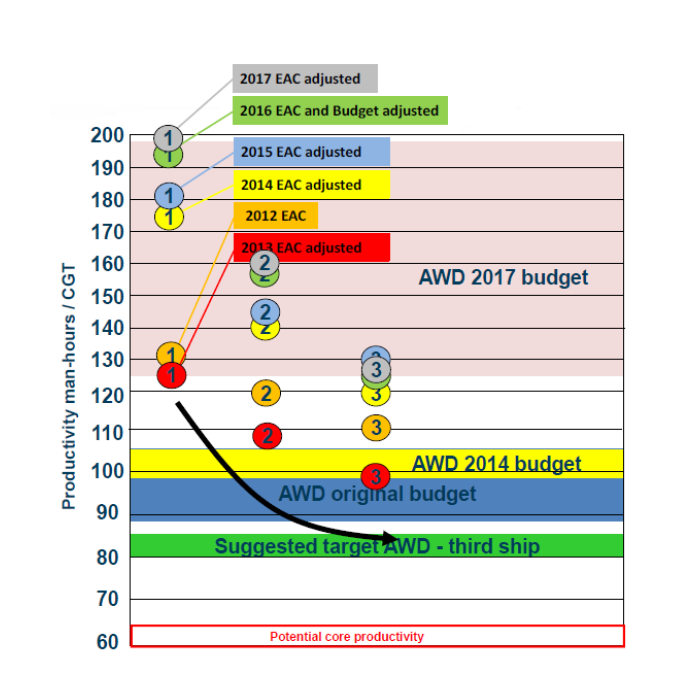

bSEA 4000 — Air Warfare Destroyer (AWD) |

June 2014 – Feb. 2018 |

3 years and 8 months |

Not yet reached. Current forecast: March 2021 |

|

23 |

JP 2008 Phase 3F — Defence SATCOM Terrestrial Enhancement |

Sept. 2014 – August 2018 |

3 years and 11 months |

Not yet reached. |

|

24 |

bAIR 5431 Phase 3 Civil — Military Air Traffic Management System (OneSKY) |

July 2017 – May 2018 |

10 months |

Not yet reached. Current forecast 31 June 2023 |

|

25 |

AIR 5431 Phase 1 — Deployable Defence Air Traffic Management System |

Aug. 2017– [continuing] |

> 1 year and 4 months |

Not yet reached. Current forecast 31 August 2019 |

Note a: In December 2007, Defence advised the incoming Minister for Defence that these ten projects — among some 215 projects then being managed within Defence by the Defence Materiel Organisation — were considered by Defence to be Projects of Concern. AIR 87 — ARH Tiger Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter and AIR 5077 Phase 3 — Wedgetail, Airborne Early Warning and Control Aircraft are known to have been on the Projects of Concern list from at least 2002.

Note b: These six are among the 27 projects reviewed in the 2016–17 Major Projects Report (Auditor-General Report No. 26 2017–18, 2016–17 Major Projects Report). The Project Data Summary Sheets in that report (p. 119 forward) give extensive detail on each project. Many of the projects that have been on the Projects of Concern list have been the subject of individual Auditor-General performance audits, including: Auditor-General Report No.26 2015–16, Defence’s Management of the Mulwala Propellant Facility; Auditor-General Report No.52 2013–14, Multi-Role Helicopter Program; Auditor-General Report No.22 2013–14 Air Warfare Destroyer Program, and Auditor-General Report No.23 2008–09, Management of the Collins-class Operations Sustainment.

Note c: These projects have been reviewed in earlier years’ editions of the Major Projects Report.

Note: No project which has been removed from the Projects of Concern list has returned to the list later. Defence advises that it has no rule, written or unwritten, prohibiting such an occurrence: it has simply not occurred.

Source: ANAO analysis of various Defence documents and ministerial press releases. Final Operational Capability (FOC) dates advised by Defence.

Length of time on the Projects of Concern list

1.6 Entry to the Projects of Concern list, and exit from it, is decided by ministers. The duration the 25 projects have spent on the Projects of Concern list differs widely, from two months (Super Seasprite helicopter) to eight years and 11 months (Collins Class submarine sustainment). The elapsed time is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Projects of Concern, January 2008–September 2018

Note: an asterisk identifies the ten projects on the original Projects of Concern list.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence data.

1.7 On the face of it, the mean elapsed time on the list of this set of projects is three years and two months. However, it should be borne in mind that:

- a range of projects had already been recognised by Defence as Projects of Concern before January 2008. For example, the Super Seasprite had been described internally as a Project of Concern in 2002; the Lightweight Torpedo replacement project had been described in this way in 2004; and the M113 Armoured Personnel Carrier went on the list in 2006. It is not known how long other projects had been there that were identified as being on the list at the start of 2008;

- Collins Class Submarine Sustainment activity had been considered a Project of Concern earlier than November 2008, but that is the effective date accepted by Defence;

- two projects remained on the list at the time this report was being prepared and their completed duration on the list will remain unknown until they are removed; and

- the audit has identified instances of projects whose entry onto the list has apparently been delayed for various reasons (see Chapter 3).

1.8 Since 2008, the number of projects on the Projects of Concern list at any one time reached a maximum of 12 during 2008–09 and 2010–11, but has a declining trend, overall, from mid-2011 to the present (Figure 1.2 on the following page). Defence has advised the ANAO that this reflects the nature of the equipment program following the changes introduced by the Kinnaird and subsequent reviews of Defence procurement.11 These reviews led to a greater priority being given to military-off-the-shelf (MOTS) acquisitions and less on developmental acquisition projects.12

Figure 1.2: Number of concurrent Projects of Concern, by month, January 2008–December 2018

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence records.

1.9 The Projects of Concern list attracts a profile in Parliamentary consideration of Defence matters and in media discussion. For most of the history of Projects of Concern, Defence has used specific criteria to provide a basis to recommend that a project be placed on the list. The approach was then enhanced with further mechanisms to invigorate and formalise the process in mid-2011. From 2017, a set of (unpublished) principles has been followed rather than specific criteria (see Appendix 2).

1.10 Defence has also maintained separate Projects of Interest and Sustainment Products of Interest lists in various forms since around 2005 (see Appendix 3).13 A Project or Product of Interest is one which Defence management considers to be underperforming and in need of senior management attention and close monitoring to prevent it deteriorating to the point of becoming a Project or Product of Concern. The Projects of Interest and Products of Interest lists are not published by Defence.

1.11 Projects of Concern and Projects of Interest form only a small proportion of the capital acquisition projects that Defence has under management. Defence reported that it had 198 major and minor capital projects under way as at 30 June 2018.

Audit approach

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.12 The reason for undertaking the audit is that Projects of Concern include projects that contribute substantial capability to the Australian Defence Force and involve a major resource commitment by the Australian Government. As a mechanism for resolving difficulties with Defence projects, there is a clear link between the effectiveness of the Projects of Concern regime and Defence’s strategic priorities as stated in one of its purposes under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act): ‘Deliver and sustain Defence capability and conduct operations’.14 Further, the Projects of Concern regime regularly receives Parliamentary attention and this audit is intended to provide insight into how Defence operates and manages the Projects of Concern regime.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.13 The objective of the audit is to assess whether Defence’s Projects of Concern regime is effective in managing the recovery of underperforming projects.

1.14 The following high-level criteria were adopted for the audit:

- Defence has established an appropriate framework for the Projects of Concern regime, including processes for the entry, management and exit of projects.

- Defence applies the Projects of Concern regime with an appropriate degree of consistency.

- Defence has established appropriate internal and external reporting arrangements on the progress of Projects of Concern.

- Defence can demonstrate that the Projects of Concern regime contributes materially to the recovery of underperforming projects and products.

Audit method

1.15 The audit was conducted by:

- examining the frameworks used by Defence for identifying projects that require additional management attention as Projects of Concern;

- examining documentation on the management, implementation, monitoring and reporting of Defence projects, scrutinising, in particular, the records of Defence Gate Reviews and Independent Assurance Reviews;

- examining three prominent case studies, of which two comprise projects that have recently been removed from the Projects of Concern list and another which is expected to be removed within a year or so; and

- interviewing key Defence officials and representatives of the defence industry. Contributions were also received from an Australian industry peak representative body and a representative of a major supplier organisation.

1.16 This audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $398,000.

1.17 The team members were David Rowlands, Natalie Whitely, Sonia Pragt and Sally Ramsey.

2. The framework for the Projects of Concern regime

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether Defence has established an appropriate framework for the Projects of Concern regime, including a clear purpose and scope, and policy and procedures for entry, management and exit of projects from the list.

Conclusion

Defence no longer has an appropriate framework for its Projects of Concern regime. The regime has two clear purposes: to resolve troubled capability development projects through remediation or cancellation with the explicit involvement of ministers; and to help keep ministers informed. However, its current implementation lacks rigour. From 2008 forward, ministers’ involvement heightened the focus on troubled projects and strengthened the regime. It was more fully developed in 2011, with the introduction of regular summit meetings chaired by ministers to review progress and stimulate action. Over the last five years, transparency has reduced, the level of formality has declined with explicit criteria replaced by unpublished principles, and processes have become less rigorous with a greater emphasis on maintaining relationships with industry.

Does the Projects of Concern regime have a clear purpose and scope?

The Projects of Concern regime has a clear purpose and scope. Its purpose is to help keep senior Defence leaders and ministers informed of material acquisition projects in difficulty and resolve problems in the project’s progress either through remediation or, where that is not practicable, cancellation. The regime has applied almost exclusively to underperforming materiel acquisition projects. Despite running in parallel for almost two decades, Defence has only recently sought to align its contractor performance data across its Performance Exchange Program and the Projects of Concern regime to ensure that views on contractor performance are consistent.

Purpose

2.1 The Projects of Concern regime has two purposes:

- to ensure that projects in serious difficulty attract senior (including ministerial) attention with a view to resolution through remediation or cancellation. The successful recovery of the project could involve a change in scope, cost or schedule15; and

- to keep ministers informed both of projects in difficulty and their progress to resolution.

Drawing underperforming projects to the attention of decision-makers

2.2 Under the PGPA Act, the Secretary of Defence has a duty to keep the responsible minister informed of any significant issue that has affected Defence.16 This is a key accountability relationship between a department and its minister. Making and keeping ministers aware of problematic projects is also a prerequisite to their involvement in resolving difficulties for the project. The first stated purpose for the Projects of Concern regime is to ensure that projects in difficulty receive ministerial and senior management attention within Defence and engagement at the most senior levels of the vendor of the project.

2.3 Further, by making the project’s difficulty known to the public, Defence expects that commercial pressure on the vendor will facilitate action on the vendor’s part that will lead to or help substantially with remediation. Defence has put the view that it has ‘few better mechanisms for influencing commercial behaviour’ than the Projects of Concern list, including the threat to a vendor’s reputation of being put on it and the possibility of being excluded from future tenders.17 There is an underlying presumption in this mechanism that vendor performance is the aspect of the project most in need of attention. Only projects where an opportunity for improvement could flow from applying pressure to industry are regarded as potential candidates for nomination to the list.

Timely consideration of underperforming projects is important

2.4 Timely consideration of underperforming projects by decision-makers is important, particularly if cancellation may be an appropriate outcome where an underperforming project is unlikely to provide good value for money or there is a substantial risk of a waste of public resources. For example, the Super Seasprite helicopter project, a Project of Concern that was subsequently cancelled, cost over $1.4 billion and yielded no capability whatsoever.18

2.5 Delay in making the cancellation decision — or failure to make that decision — raises the risk of incurring additional sunk costs, as explained by a Senate Committee inquiry into Defence procurement:

a delayed or unsuccessful project creates a capability gap, fails to meet the government’s strategic requirements, damages Defence’s relationship with industry and undermines public and parliamentary confidence in Defence’s procurement program.19

2.6 Delaying the entry of projects onto the list, as noted in Chapter 3, may undermine the purpose of the list and result in wasted public resources if the project must subsequently be cancelled.

Keeping ministers informed

2.7 The Minister for Defence set out an additional purpose for Projects of Concern in 2010:

[The Minister for Defence Materiel] and I will announce later today that project AIR 5418, the acquisition of the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM), has been added to the Projects of Concern list. This listing is not primarily because of industry delays or cost increases. It is because of our poor management, our failure to keep Government properly and fully informed about the Project and its difficulties.20

2.8 The Minister raised this matter with Defence on numerous occasions.21 Defence records show that Defence did not provide full and frank information in a timely manner on at least one occasion where a classified project with an approved $50 million facilities component had suffered a ‘cost blow-out’ to $150 million in those costs. After being aware of this for several months the relevant Defence groups could not agree to advise the Minister.22 Further, Defence records indicate concerns about providing frank assessments of Projects of Concern to the Minister, in particular, if that information might then also be available to the Auditor-General.23

2.9 In direct response to this finding, Defence advised the ANAO in February 2019 that ‘Defence is of the view that anything pre-2015 is of limited value due to the significant shift in the nature of the relationship with Industry and the Defence Operating Model as a result of the First Principles Review’.

Scope

2.10 Of the 25 projects listed as Projects of Concern between 2008 and 2018, 24 have been projects to develop and acquire military capability (acquisition projects).24 In addition, one ‘product’ under sustainment (Collins Class Submarine sustainment) has been listed.

2.11 Projects have generally been listed after ‘Second Pass’ approval of the project by government, where the vendor has been selected and contracts are in place or nearly so. In two cases, acquisition projects have entered the list before contracts have been signed with vendors. These have been AIR 5431 Phase 3, the Civil and Military Air Traffic System (CMATS), and LAND 40 Phase 2, Direct Fire Support Weapons.25

Performance Exchange Program

2.12 Since 2001, Defence has monitored and reported on the performance of major Defence contractors for capital acquisition and in-service support. Previously known as the ‘Company Scorecard Program’ and now known as the ‘Performance Exchange Program’, the program encompasses contracts that exceed the thresholds of $10 million (acquisition); $5 million (sustainment) and $5 million (services). Defence has advised that, ‘under the Performance Exchange Program, decision-makers across both Defence and industry now have a set of measures that are directly relevant to decision-making and performance across domains, military capabilities and tiers across the Defence industry sector’.26

2.13 The Performance Exchange Program and the Projects of Concern regime have a common objective, better performance, and they have proceeded in parallel for nearly two decades. Defence has raised concerns that inconsistent views can develop between the two processes. Defence has advised that:

… an updated Performance Exchange process has been developed and implemented to address this issue, as well as to deliver broader, and honest, two-way performance reporting between Defence and its contracted key industry partners.27

Has Defence established policy and procedures for the entry, management and exit of projects from the Projects of Concern regime?

Defence has established a policy for its Projects of Concern regime and procedures for the entry, management and exit of projects. In 2009 and 2011, Defence’s approach was made more formal and rigorous at the instigation of ministers. In recent years, the transparency and formality of the process have diminished, regular summits chaired by ministers have been replaced by ad hoc meetings, and Defence no longer publishes its principles and procedures for Projects of Concern. Maintaining collaborative relationships with industry has become a more dominant element in the governance of the regime.

2.14 The development of Defence’s approach to managing its Projects of Concern regime is reflected in the statements of processes, criteria and principles set out at various times since the commencement of the regime in 2001 (see Appendix 2):

- In its earliest form (2001), Defence adopted a simple set of ‘hard’ criteria for making a project a Project of Concern, relating to governance, capability, schedule and budget. The criteria at this point were substantially numerical and the regime was largely internal to Defence.

- Ministers became involved in 2008; the subsequent statement of criteria in 2009 moved away from numerical triggers and introduced a greater element of judgement. It introduces procedures for entry to the list, and exit, both by ministerial approval. A requirement for a plan for resolution (through cancellation or remediation) was required from this point.

- The 2011 statement, announced in a press release by the Minister for Defence, introduced substantial additional elements, including incentives for industry to fix problem projects; a new ‘Early Indicators and Warnings’ system to flag potential problem projects; the use of Gate Reviews to analyse each such project; more detailed requirements for remediation plans and greater ministerial involvement through bi-annual Projects of Concern reviews (summits), being face-to-face meetings with the minister ‘to hold responsible individuals to account’.

- In 2017, the ‘Statement of Principles’ introduced an emphasis on a ‘collegiate culture’ and included no reference to incentives for industry. There was no mention of review meetings (summits) with the minister.

- The 2018 principles set out more procedural activity, including reporting to government and Parliamentary committees. The principles again mention summit meetings with the minister but these are to be held ‘when required’.

Ministerial involvement in strengthening the Projects of Concern regime

2.15 In mid-2008, the General Manager, Programs, Defence Materiel Organisation flagged ‘a major shift in thinking’ at ministerial level to his colleagues. He told them that ‘Projects of Concern are a serious issue for Defence and are currently attracting high public and political visibility and could be subject to precipitous decisions’. He stated:

From my meetings with the Parliamentary Secretary and the staff in the Minister’s office it is clear to me there has been a major shift in thinking about these projects. The new default way forward for a “Project of Concern” is to assume that the project will be cancelled unless sufficient justification is provided each month that the project can deliver its scope dependably within any agreed (revised) schedule and funding. Failure to do so will result in the project being recommended for cancellation by the Minister and Parliamentary Secretary. This puts the onus on the project office (assisted by the sponsor and capability manager) to show that they have an acceptable way forward to delivering the approved materiel capability within the agreed schedule, budget and risk profile.28

2.16 With projects identified as Projects of Concern to be subject to ‘intense management’, with a prospect of cancellation, Defence required a remediation plan that set out for each Project of Concern ‘an acceptable way forward to delivering the approved materiel capability within the agreed schedule, budget and risk profile’. Ministers became more involved, including by the Minister for Defence Materiel deciding entry to the list and exit, on Defence’s advice.

2.17 The General Manager emphasised that ‘While cancellation may be a suitable outcome in a small number of cases, in most cases it would be very unacceptable from a capability and reputation point of view’. He also advised Service Chiefs that if a Project of Concern were cancelled, they should not assume there would be a replacement program. He also stated that it was important to reduce the Project of Concern list to zero in the shortest possible time.

2.18 Defence then set up a Projects of Concern unit to report to the Parliamentary Secretary on progress with remediation:

The unit has been tasked with providing assistance and advice to the projects to help them get back on track, while also drawing detailed information from each project and providing it to Government on a monthly basis. This has allowed the Government to become more active in the management of these projects and has informed its decision making when it comes to how we should handle these projects.29

2.19 The process was further strengthened in 2011 with the Minister for Defence engaging with industry on how to improve the process. Industry advice formed the basis for reforms announced on 29 June 2011 by the Minister for Defence and the Minister for Defence Materiel. The reforms, which applied from 1 July 201130 included:

- incentive arrangements for industry to focus on fixing problems — through weighing a company’s performance in remediation when evaluating tenders for other projects;

- a formal process for adding projects to the list — using the triggering of Early Indicators and Warnings (discussed below) as a basis for advising ministers and potentially leading to a Gate Review;

- a requirement for formal remediation plans — prepared by Defence and industry;

- a process for removing projects from the list — involving government decision; and

- increased ministerial involvement — through bi-annual reviews with Defence and industry.

Early Indicators and Warnings

2.20 Earlier concern that Defence senior management — and ministers — be kept aware of projects in difficulty led Defence to develop a system of mandatory ‘Early Indicators and Warnings’ on project progress. The triggering of one or more of these criteria was expected to lead to a Gate Review and consideration of whether the project should be nominated for inclusion on the Projects of Concern list.31

2.21 The Early Indicators and Warnings system emphasised early identification of risks and problems, as the name indicates.32 The Ministers’ announcement stated:

Defence assesses that 80 per cent of problems with Defence capability projects occur in the first 20 per cent of the project’s life.

That is why it is important to pick up problems early.

One of the biggest challenges in Defence procurement is projects running late. The earlier these issues are picked up, the earlier the problem can be fixed.

The Government will implement an Early Indicators and Warning System. This system will help identify and correct potential problems with projects.33

2.22 Before the 2011 reforms, nomination depended upon project staff identifying that the project had crossed a threshold and/or senior managers in Defence identifying the underperformance from internal reporting. A significant change to the process of nominating projects flowed from the use of Gate Reviews and their successor, Independent Assurance Reviews, to provide a critical review and considered approach. That process continues.34

Operation of the Projects of Concern regime in 2018

2.23 Defence has stated in evidence to the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee that the Projects of Concern regime is a disciplined process, both for entry and exit.35 In December 2018, that process was set out in Defence’s operating principles on its intranet site.36 In contrast to the 2011 principles, Defence does not make the 2018 principles public.

2.24 There has been a change over the years in the character of the criteria used to nominate projects to the Projects of Concern list (see the sets of criteria at various points of time set out in Appendix 2). In the earlier years, entry to the Projects of Concern list was based on a range of ‘hard’ criteria, such as a percentage change in expected cost or schedule being exceeded. A more recent characterisation is that ‘There are no set quantitative measures or thresholds …’ (2017). The rationale has been that the complexities that characterised the projects under consideration cannot be captured in such criteria.

2.25 A significant change is that, whereas the 2011 process included the Minister for Defence Materiel holding bi-annual reviews of Projects of Concern (summits) with Defence and Industry representatives, that element had been omitted from the 2017 edition (see Appendix 2) and referred to in the current principles as occurring ‘when required’. There is also a greater emphasis on collaboration between Defence and industry and less on mechanisms such as providing incentives for industry to fix problem projects. Defence has stated to the ANAO that ‘The main focus is on collaboration to obtain the best possible capability outcomes within the schedule and cost constraints of the program’.37

2.26 In February 2019, Defence advised that project cancellation remains an option:

Placing a project on the PoC list aims to provide additional support to remediate the project and deliver capability and value-for-money outcomes to the Department of Defence. If these outcomes cannot be achieved, project or contract cancellation may be considered.

Industry view

2.27 The ANAO received a submission from the Australian Industry Group, on the Projects of Concern process stating:

Industry feedback noted that the Projects of Concern process can be valuable; however, the current system lacks transparency. Industry comments stated that the criteria used to establish a Project of Concern are unclear, as well as the processes used to manage and resource the project once on the list.38

2.28 There is no public information on either the Defence Internet site or the Defence Annual Report 2017–18 on how the Projects of Concern process operates.39 The Australian Industry Group stated:

Overall, our members’ view is that the Projects of Concern process should have a high degree of visibility and status, a clear and transparent set of criteria and scheme for elevation, and be part of the regular conversation between Defence and industry.

Management of Projects of Concern following the First Principles Review

2.29 Following the First Principles Review, Defence introduced its Integrated Investment Program to govern investment in Defence’s strategic goals. The First Principles Review also led Defence to introduce its new Capability Life Cycle and the notion of ‘capability streams’:

To allow effective high level prioritisation and communication with Government, the Integrated Investment Program is structured into six Capability Streams which were developed through the 2015 Force Structure Review process. Defence capabilities (Programs) were defined and mapped to the Capability Streams.40

2.30 The Air Warfare Destroyer build case study undertaken as part of this audit shows that a risk which came to attention during the project — declining shipyard productivity — may now be more significant to the progress of the wider capability stream Maritime and Anti-Submarine Warfare than to the remainder of the Air Warfare Destroyer build project itself.41

2.31 However, the operation of the Projects of Concern regime is not well-defined in the context of the new Capability Life Cycle. There is no reference to Projects of Concern in: Defence’s Capability Life Cycle — detailed design; Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group’s Complex Procurement Guide (March 2018); the 2016 Defence White Paper or the accompanying 2016 Integrated Investment Program and 2016 Defence Industry Statement. The absence of clear guidance on the operation of the Projects of Concern regime as part of the risk management framework gives the appearance that the regime is of marginal importance in the context of the Capability Life Cycle.

2.32 As a result of the First Principles Review, a proposal was developed within CASG in early 2017 for the potential extension of the Projects of Concern regime to align it with the One Defence framework. Such an extension could usefully encompass the issue of broader application of risks identified in any particular project to the capability stream of which it forms a part.42 In October 2018, Defence indicated that, following a discussion by its Investment Committee in September 2018, it supports expanding the scope of the Projects of Concern regime to encompass all projects managed across Defence, and this would be consistent with the One Defence approach.43

3. Application of the Projects of Concern regime

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether Defence has applied its Projects of Concern regime with an appropriate degree of consistency, including the entry, management and exit of projects from the Projects of Concern list.

Conclusion

There has been inconsistency in Defence’s application of its Projects of Concern regime. In particular, application of processes for entry onto the list have been inconsistent and summit meetings to address Projects of Concern have become less frequent. Greater consistency has been maintained in preparing remediation plans and removing projects from the list, though there have been exceptions to both.

Area for improvement

This chapter recommends that a formal policy with supporting procedures be introduced for the Projects of Concern regime to improve consistency in managing entry to, and exit from, its Projects of Concern list and that Defence follow through on its risk assessment reform program.

Further to the recommendation, the introduction of guidance for risk assessment of projects by Independent Assurance Reviews would help Defence improve the effectiveness of the regime.

Does Defence apply a consistent process to the entry of projects to the list?

Defence does not apply a consistent process to the entry of projects to the Projects of Concern list with evidence of delays as well as advice being withheld from review processes and decision-makers. Procedures for Independent Assurance Reviews do not explicitly mention Projects of Concern even though such reviews are the primary occasion for nominating a project to be a Project of Concern. There was evidence that most reviews (75 per cent) had considered whether a recommendation should be made.

Procedures for recommending a project as a Project of Concern

3.1 From June 2011 forward, the Projects of Concern processes require a recommendation that a project be considered for inclusion on the Projects of Concern list to originate from a Gate Review or Independent Assurance Review.44 One of the primary purposes for Independent Assurance Reviews is the early identification of problem projects and sustainment products.

3.2 The existing 19-page formal instruction governing the operation of Independent Assurance Reviews does not instruct an Independent Assurance Review Board to consider whether a project should be nominated for inclusion on the Projects of Concern.45 As Projects of Concern are not directly mentioned in the instruction, there is a risk that troubled projects might not be drawn promptly to the attention of senior management for consideration for listing as a Project of Concern. There would be merit in updating instructions for Independent Assurance Reviews to reflect their role in recommending whether a project should be a Project of Concern.

Consideration of projects as Projects of Concern

3.3 From a review of records of 191 Gate Reviews and Independent Assurance Reviews conducted since 2015, the following challenges in the management of entry of projects to the Projects of Concern list were identified:

- in a minority of cases, no record of whether consideration was given by an Independent Assurance Review as to whether a project warranted nomination to the list;

- potentially delayed entry of projects to the list;

- delays in advice to ministers of a project in difficulty;

- restrictions on information available to an Independent Assurance Review;

- deciding not to nominate a project because it might attract additional workload;

- incidental identification of a potential Project of Concern; and

- an inconsistent approach to publicising additions to the Projects of Concern list.

3.4 These instances are discussed below.

Inconsistent consideration as to whether a project warrants nomination

3.5 Of the 191 Gate Review Boards and Independent Assurance Review Boards reviewed, in 144 cases (75 per cent) the Board both considered whether the project should be recommended for Project of Concern status and recorded its view (as outlined in Table 3.1). Of the remaining 47 cases, there were:

- 27 cases where the project was in the early or late stage; and

- 20 cases (10 per cent) with no record of consideration of whether the project should be nominated as a Project of Concern or as a Project of Interest (see paragraph 1.10).

Table 3.1: Gate Review and Independent Assurance Review consideration

|

|

SEA |

LAND |

AIR |

JOINT |

Total |

|

No. of Gate Reviews/IARs examined |

31 |

41 |

72 |

47 |

191 |

|

No. where consideration of Project of Interest/ Project of Concern status was not recorded |

4 |

11 |

26 |

6 |

47 |

|

No. where a rationale was not apparent for omitting consideration of this status. |

2 |

1 |

14 |

3 |

20 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence records

Delayed entry to the Projects of Concern list

3.6 Defence records indicate that there have been occasions when considerable time elapses between the first record of Defence contemplating the nomination of a project to be entered onto the Projects of Concern list and its actual entry. Any unnecessary delay in action leading to the resolution of projects carries a number of risks. Some of these risks are that:

- as Defence is aware (paragraph 2.21), the more advanced the project the greater the costs of any corrective action;

- delays can reduce the capacity of Defence to influence, on terms favourable to the Australian Government, the vendor’s actions in support of problem resolution; and

- delays increase reputational risk associated with more radical options available to Defence (such as project cancellation) and increase the risk of the public resources being wasted as observed, for example, in the Super Seasprite project.46

3.7 Instances of lengthy periods, typically two years, elapsing between Defence’s observing problems with a project and the project entering the Projects of Concern list are set out in Box 1.

|

Box 1: Projects of Concern with delayed entry to the list |

|

3.8 In relation to delayed entry of projects onto the list, Defence advised the ANAO in February 2019 that:

It needs to be acknowledged that there is a qualitative/management judgement aspect to [Projects of Concern] that has always existed and always will. Arguably, some projects could have been added sooner, however, Defence officials are always cognisant of the trade-off between allowing a company more time to ‘come good’ and the right time to add to the PoC list, including the cost/benefit analysis. A more detailed analysis would reveal that behind the scenes there is a considerable amount of engagement, negotiation, consultation, expectation setting, between the company (and/or Parent Company), Defence and often the Minister’s office. Usually, the time is related to companies working toward contractual milestones, or complex technical solutions which can be lengthy but have been negotiated in good faith. Defence often needs to wait for the expiry of timeframes (some of which are legally bound) before further firm action is taken. That does not imply that nothing is done, nor that the implication of becoming a project of concern has not been socialised at the senior level with a company.

Delays in advice to ministers

3.9 AIR 5431 Phase 1, mentioned among the case studies above, also represents a delay in Defence drawing the attention of ministers to a project that is underperforming. The November 2015 Gate Review, having observed a 16-month slippage only 11 months into the contract, recommended that government be informed of current project status, as the schedule was unlikely to be recovered.

3.10 A year later, the Defence Agendum paper prepared for the subsequent Independent Assurance Review (November 2016) noted that:

There has not yet been any specific updated advice to Government on the status of this project, despite the Gate Review recommendation last year. DGCP-AF [Director-General, Capability Planning–Air Force] advises that this project is a lower priority, both for Air Force and for Ministers, and that there is not an urgent need for such an update. Government will be advised ‘in due course’, as part of broader advice on the full range of air traffic control projects.50

3.11 As noted above, the project was added to the Projects of Concern list a year later, in August 2017, where it remained in December 2018.

Restricting information supplied to Independent Assurance Reviews

3.12 Given the important role of Defence’s Independent Assurance Reviews in identifying problem projects and products, including potential Projects of Concern, it is essential that they be supplied with all the information they need to carry out their work. The Independent Assurance Review conducted for SEA 1180 (Offshore Patrol Vessel) on 17 July 2017 reported as follows:

The team were restricted in being able to provide any meaningful detail, even when there was no suggestion that they provide the outcomes for each tenderer. Consequently, I am not able to provide an informed independent assessment of the deliverability of this project, nor of the appropriateness of the schedule, cost and risk assessments. I do feel that this is a missed opportunity for the project given the breadth of experience of the Board Members. Furthermore, I am not sure of the value of conducting an Independent Assurance Review for Gate 2 projects that have such restrictive information access …

Given the limitation for access to information for reviewers and the restrictions imposed on the project team and the Capability Sponsor’s ability to speak to the specifics of tender responses, particularly as they relate to cost, schedule and risk at the Board Meeting, I am not in a position to advise on the true status of the project, whether the cost estimates, schedule or risk assessments are a sound basis for progressing to Second Pass Approval, nor what more needs to be done to support the Approval Process or to enhance the actual delivery [Emphasis in original].

3.13 The reason for the restriction in supplying information to the Independent Assurance Review is not evident in the documentation. This approach has several consequences:

- such restrictions reduce the value of holding an Independent Assurance Review;

- the approach could keep from senior management risks that the Independent Assurance Review is best placed to identify. Those risks could then develop and crystallise; and

- even if this instance is unusual, it may form an undesirable precedent that, if followed, could lead to failure to detect risks in other projects.

3.14 In response to this finding, Defence advised the ANAO:

This example is isolated and was particularly disappointing…However, it should be noted that there is no identified systemic issue of information being withheld from IAR reviewers.51

Deciding not to nominate a project because it might attract additional workload

3.15 An Independent Assurance Review for project JP 2008 Phase 5a, UHF SATCOM, took place on 1 August 2017. The Review Board considered that there were several significant issues that put the project in jeopardy. The Board concluded that ‘the Government must be advised about the schedule slippage to Final Operational Capability’.52 It expressed concern at the lack of senior executive oversight and found that the budget was a ‘major concern’.

3.16 Nevertheless, the Board’s ‘summary assessment’, considered and approved by senior officers (SES and star-ranking) in Defence, included the following finding:

The Board did discuss the possibility of elevating the project to a Project of Concern from a Project of Interest but agreed that this could create more work and challenges for a Project Office that is already overtasked.53

3.17 If the Projects of Concern regime is working effectively it should not be viewed by senior officers as creating bureaucratic overhead. Rather, it is intended to resolve problems that are proving intractable at lower levels of management and decisions not to employ the regime may result in delays and lost opportunities to progress a troubled project.

Incidental identification of a potential Project of Concern

3.18 An Independent Assurance Review of LAND 2072 Phase 2B, Integrated Tele-communications System — Land, took place in July 2017. The Board found that the project had made good progress, was ahead of schedule and the project team was handling issues professionally. Nevertheless, there were issues beyond the team’s control that presented contingencies to the project’s success. One of these was the delivery of the next generation of deployable local area network, a project being undertaken as a sustainment item. The Board was advised that the vendor’s performance had been ‘extremely disappointing’.

3.19 The Board concluded:

I am concerned by the eDLAN [enhanced deployable local area network] situation. It is unclear why an undertaking of this obvious complexity is being performed in a sustainment environment with inadequate governance and oversight. HJS [Head, Joint Systems] made an observation that if eDLAN was a Project, it would be ACAT II [Acquisition Category II, the second most significant] and on the current performance it would be a Project of Concern. CASG should review carefully the lessons being learned from the eDLAN experience and should engage with other stakeholders to ensure that follow-on DLAN projects are subject to more appropriate governance and management arrangements.

3.20 Even though there is a precedent for sustainment products being elevated to the Projects of Concern list (for example, CN10, Collins Class Submarine), there is no evidence of any further consideration within Defence of this finding.

Inconsistent approach to publicising additions to the Projects of Concern list

3.21 Defence has indicated that the operation of the Projects of Concern list depends substantially on the commercial pressure on vendors created by the public listing as a Project of Concern of the project they are involved in (paragraph 2.3). However, there have been occasions when a project has been added to the Projects of Concern list but this fact has not been made public, or at least, not until some months later, limiting the effect intended by elevating the project to that status. Instances include:

- JP 2008 Phase 3F, Defence SATCOM Terrestrial Enhancement.

- JP 2088 Phase 1A, Air Drop Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat Trailers.

- AIR 5402, Air-to-Air Refuelling Capability.

- JP 2048 Phase 1A, Landing Platform Amphibious Watercraft.

Reforming risk management practices

3.22 Following a review of the effectiveness of the CASG’s risk management framework, practices, systems and methodologies, Defence approved a Risk management reform program and implementation plan in June 2017 to remodel the Group’s risk management.54 This reform program noted that CASG had, at that time:

no standardised approach to risk identification, assessment, risk reporting or risk reduction. [Thirty-seven] different risk management software tools were identified alongside hundreds of different templates, methods and formats for capturing and presenting risk.55

3.23 The reform program set out priorities including to ‘develop business rules regarding Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern’. These would:

enhance the means by which Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern are identified, assessed and managed as part of the CASG Risk Management Model. The goal of this effort is to proactively move projects with this status to a level where the risk is in line with the organisational appetite for risk.56

3.24 In terms of Projects of Concern, the approved program of work set out the following:

For the Specialist Risk Area of Projects of Interest or Projects of Concern, develop a suitable module that will integrate and connect with the CASG Risk Management Model for this application. This module may include the “Practice Guide” for this Specialist Risk Area (p. 8).57

3.25 Subsequently, in August 2017, the Major Programs Control Directorate advised those leading the work on the Reform Program that the governance and processes for Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern already existed and that specific risk management practice was not required. There is no record of any further action having been taken on the planned work.

3.26 A subsequent Defence Internal Audit ‘Management of Selected Projects of Interest’ (April 2018) found that formal documentation of the process for Projects of Interest was not yet complete.58 The process relied on ‘professional judgement’. With no standard approach to risk identification, assessment, risk reporting or risk reduction, there can be no assurance that Projects of Concern — or Projects of Interest — are being identified appropriately and in a timely way.

3.27 Regardless of the detailed reasons for the difficulties that arise in any individual case, every project approved by government has a defined estimate of cost and schedule, and is expected to deliver a specified set of capabilities. These will all have been agreed by government and understood at the time of that approval. It should be possible to set tolerances — a risk appetite — which, when exceeded, form a clear and sound basis for concern, and a trigger to alert ministers to emerging risks.

3.28 The Projects of Concern regime could benefit from establishing a simple set of primary entry, management and exit criteria based on cost, schedule and capability, with further technical detail supplied to ministers and senior managers as and when required. These could be embodied in a short, transparent, formally-approved set of procedures which would help provide confidence that the process is being administered rigorously, fairly and consistently.

Recommendation no.1

3.29 Defence introduce, as part of its formal policy and procedures, a consistent approach to managing entry to, and exit from, its Projects of Interest and Projects of Concern lists. This should reflect Defence’s risk appetite and be made consistent with the new Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group Risk Model and other, Defence-wide, frameworks for managing risk. To aid transparency, the policy and the list should be made public.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

3.30 Defence agrees to this recommendation noting that Defence will endeavour to provide this formal policy as the Project Management specialist risk discipline is developed as part of the new CASG Risk Model. This work will build on the current quantitative measures against scope, schedule and cost to potentially include lead indicators of project performance. The Defence Projects of Concern list will continue to be made public.

Does Defence apply a consistent process to the management of projects while on the Projects of Concern list?

Broadly, Defence has applied a consistent process to the management of projects while on the Projects of Concern list. However, summit meetings involving the Minister, vendors and officials, a principal process devised in 2011 to help ensure that Defence can use its Projects of Concern regime to exert commercial pressure on vendors, are no longer regular and they have become less frequent. Another long-standing process, the preparation of remediation plans, has usually been followed.

3.31 Defence has used three principal processes to manage Projects of Concern while they are on the list: the preparation of remediation plans (commenced in 2009); the holding of regular summit meetings with the minister, attended by Defence officials and vendors (from 2011); and the application of commercial pressure through contract arrangements (from 2011).

Remediation plans

3.32 Since 2009, there has been a requirement that when a project is placed on the Projects of Concern list, a remediation plan would be prepared and agreed between the parties. Remediation plans were to be agreed at, or prepared in light of, Projects of Concern summits. For example, the department advised the Minister for Defence in October 2011 that:

During the recent Projects of Concern summit, 27–28 September 2011, you directed that a Remediation Plan and Action Log be developed by each project in consultation with the companies … Remediation Plans define the agreed strategy to remediate a project and the basis for removing the project from the Projects of Concern list. The Action Log defines the commitments made by the project manager, company CEO and others in each six month period between Projects of Concern summits.59

3.33 With an agreed remediation plan, it becomes feasible to measure progress against that plan with the action log. Remediation plans were to include the basis on which a project would be removed from the Projects of Concern list (‘removal criteria’). The prospect of further summit meetings at a regular frequency provides an incentive for participants to discharge their commitments before the next summit.

3.34 Defence’s June 2018 Projects of Concern report provided Defence senior leaders and ministers with:

- a summary of remediation expectations for the short, medium and long term and removal criteria for all three projects on the list, a forecast date for removal and statement of progress towards that; and

- a more detailed description of the expected path towards remediation but not specific remedial actions and accountability. Some of the activities are expressed in general terms such as ‘engage with the vendor’, rather than setting out specific remedial action and who is to do it.

3.35 The audit examined whether remediation plans had been prepared for the three projects selected as case studies (Air Warfare Destroyer, MRH90 helicopters and Collins Class submarine sustainment) and the other projects that remain on the Projects of Concern list or which have been removed over the preceding twelve months (AIR 5431 Phase 3, CMATS; AIR 5431 Phase 1, Deployable Air Traffic Management and Control System; JP 2086 Phase 1, Mulwala Redevelopment Project; and JP 2008 Phase 3F, Defence SATCOM Terrestrial Enhancement).

Remediation plans for case study Projects of Concern

3.36 Remediation plans had been prepared for each of the three projects comprising the major case studies:

- For Air Warfare Destroyer (see Appendix 4, paragraph 19 forward) the remediation plan flowed from the Winter-White Review of the project, commissioned by both Defence and Finance, before the project entered the Projects of Concern list. The project is now expected to be completed with Initial Operating Capability forecast for December 2019. However, a primary basis for the project entering the Projects of Concern list, shipyard productivity, has deteriorated.

- For MRH90 helicopters (see Appendix 5, paragraph 10 forward) the remediation plan was centred on two deeds to the acquisition contract. These, too, were agreed before the project entered the Projects of Concern list. Evolving remediation requirements and action were then discussed at subsequent Projects of Concern summit meetings. Remediation is not complete and the project remains on the list.

- Collins Class submarine sustainment (see Appendix 6, paragraph 9 forward) was declared a Project of Concern before the remediation plan was prepared. The major element of that plan comprised the Coles Review. Remediation has been successful in terms of boat availability (materiel-ready-days) though sustainment costs remain an ongoing concern.

Remediation plans for other projects

3.37 For the other projects that remained on the Projects of Concern list at the time that audit fieldwork was undertaken or had been removed over the preceding twelve months, the approach to preparing remediation plans varied:

- Defence documentation indicates that, whereas no formal remediation plan was agreed with the vendors for the Mulwala Redevelopment Project, Defence was satisfied that the project had successfully completed Defence’s objectives for remediation.

- In the case of the Defence SATCOM Terrestrial Enhancement, a remediation plan was developed by Defence as an agenda item for the summit with the Minister on 20 July 2015. Defence and the vendor continued to engage on the remediation plan thereafter. However, the project was not completed as originally envisaged and a deed of settlement was signed with the vendor in November 2017.

- In the case of CMATS, which entered the Projects of Concern list in July 2017, no remediation plan was prepared upon it becoming a Project of Concern. Following contract execution, CMATS was removed from the list.60

- For the Deployable Air Traffic Management and Control System, a remediation plan had been developed in October 2016, before the project entered the Projects of Concern list. However, an Independent Assurance Review in November 2017 found that the remediation plan had not delivered the expected performance and the risk profile was bleak. Defence stated in February 2019 that a further remediation plan had been agreed in-principle on 11 September 2018. However, a contract change plan was yet to be finalised as Defence awaited outstanding documentation from the vendor.

The status of remediation plans

3.38 In October 2018, Defence advised the ANAO that the role of remediation plans set out in paragraph 3.32 no longer describes the process:

Since [the First Principles Review], industry is a Fundamental Input to Capability and remediation plans are agreed by all parties and progress reported against. The main focus is on collaboration to obtain the best possible capability outcomes within the schedule and cost constraints of the program.

3.39 On the current status of remediation plans for Projects of Concern, Defence further advised the ANAO in October 2018 that :

some were drafted during the [2010–13] era and some were drafted for the last full-on summit with [the then Minister] but not endorsed by any of the parties. It is important to keep in mind that PoC is not about introducing additional overhead, it is about getting the appropriate help for the project.61

3.40 This advice conveys a diminished view or expectation of remediation plans within Defence and leaves their current status uncertain, even though they remain a requirement under the current principles for the Projects of Concern regime.

Summit process

3.41 Under the Projects of Concern processes adopted in 2011, an important element was a six-monthly review or ‘summit’ meeting with the responsible minister. These meetings were held regularly from 2011 through to 2013, usually over a two-day period, and chaired by the responsible minister.62 They were attended by Defence officials and senior industry representatives. Their purpose was to address the problems of the Projects of Concern and prepare a remediation plan.

3.42 Typically, these summit meetings took place at Parliament House, Canberra. An hour or more was allocated for each Project of Concern, with successive groups of vendor representatives for respective projects in attendance, each only for the relevant period, along with senior Defence staff responsible for that project. The Chief Executive Officer of the (then) Defence Materiel Organisation stated:

I have observed many cases where significant progress has been achieved in the days leading up to the summit, demonstrating that their frequency is key to sustaining momentum.63

3.43 By late 2014, however, no summit had been held for over a year, which had led, in Defence’s view, to ‘a stagnation of this key element in the Projects of Concern regime’. Defence advised the Minister in November 2014 that:

Should the summits not proceed in the near term, there is a risk that some of the commercial leverage and momentum developed over the past six years would be lost. This is particularly important given the recent addition of the $8 billion Air Warfare Destroyer (AWD) programme to the list. A summit will provide a forum where the relevant senior stakeholders can be brought together to discuss the unique commercial, schedule and cost sensitivities involved, and begin the remediation work at the most senior levels.

3.44 Defence took the view that the Minister’s presence generated gravitas, which was a key element of the success of the program. Defence wished to maintain what it saw as the momentum of the program. A summit meeting was subsequently held, on 20 July 2015.

3.45 Defence has advised that two project-specific summits have been held since that time:

- 12 September 2018 for AIR 5431 Phase 1, Deployable Defence Air Traffic Management and Control System; and

- 16 August 2017 for AIR 5431 Phase 3, Civil Military Air Traffic Management System.64

3.46 As noted earlier, the Projects of Concern principles of 2017 (see Appendix 2) and those currently in effect (see paragraph 2.23) do not refer to six-monthly or any other review or summit meetings with the minister. There is no longer an expectation that there be regular summit meetings. Defence has advised that they are ‘held on an “as required” basis, depending on the nature of the issues with the project and the wishes of ministers.’65 A submission provided to the ANAO in November 2018 by an industry peak body stated that:

From a practical point of view, one company involved in the process noted that attendance and scheduling of the Projects of Concern meetings tended to be ad hoc. Similarly, the structure/ agenda for the meetings could vary greatly dependent on the Ministers at the time. The most positive meetings were when the Minister personally engaged with all the participants in an open and direct conversation.66

Using Project of Concern status to apply commercial pressure