Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Defence Industry Support and Skill Development Programs

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s administration of industry support and skill development programs.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Industry has an important role in supporting the Department of Defence (Defence) and the Australian armed forces, supplying over $5 billion of materiel and equipment each year.1 In the Australian context, eight defence industry prime contractors (primes) deliver approximately 70 per cent of the value of defence materiel annually.2 The industry also includes a number of small to medium enterprises (SMEs).3 Around 29 000 to 30 000 Australians are employed in the defence industry in support of military acquisition and sustainment tasks – around half of whom are employed in SMEs.4

2. In 2010, Defence released a Defence Industry Policy Statement to provide Australia’s defence industry with an indication of future policy directions. The Policy Statement announced that $445.7 million in funding was to be allocated to 19 industry support and engagement programs over the period 2009-19. The Government of the day committed to increasing the opportunities for, and improving the competitiveness of, the Australian defence industry. Since that time, several of the programs have been discontinued, and other programs have been announced. There are currently 11 main industry programs. A new Defence Industry Policy Statement and Defence White Paper are due for release in 2016.

Audit objective and criteria

3. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s administration of industry support and skill development programs.

4. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence effectively coordinates, promotes and monitors the performance of the suite of industry programs; and

- for the three programs examined in depth, Defence has implemented sound management arrangements for the programs; and the programs are meeting their objectives.

Conclusion

5. To give effect to the Defence Industry Policy Statement, Defence delivers programs that aim to support the Australian defence industry and build its skill base. Responsibility for individual programs is dispersed across Defence, and there has been no overarching framework to help coordinate Defence’s management of the large number of programs and monitor their alignment with the goals of the Policy Statement. Across the suite of industry programs, less than half have effective performance frameworks in place. As a result it is difficult for Defence to assess: whether a program’s outcomes are meeting its objectives; the value for money of these programs; or an individual program’s contributions to the achievement of the Policy Statement. There is also limited or inconsistent information available about Defence’s industry programs through relevant websites.

6. For the three programs examined in detail by the ANAO, there remains scope to improve compliance with relevant business processes and program requirements, and a need to focus on strengthening performance management frameworks to provide assurance that program outcomes are being realised.

Supporting findings

Governance arrangements for Defence’s industry programs

7. Defence has administered a large number of small programs over the last five years without an overarching framework to help coordinate activity. These programs have been managed and administered by various areas within Defence and other government departments, and include involvement from industry and research agencies.

8. There was limited and inconsistent information available about Defence’s industry programs through their websites.

9. Defence does not adequately monitor program performance at a collective or, in most cases, at an individual level. Only a few of the programs report on performance and outcomes. The others do not undertake any reporting against KPIs or assess how they are meeting the program objectives. Not tracking performance for the programs means that Defence cannot assess whether program outcomes are meeting defined objectives, or the contribution made by individual programs towards achieving the overall objective of the Australian Government’s Defence Industry Policy Statement.

10. The ANAO has made a recommendation aimed at improving performance measurement, monitoring and reporting of the industry programs.

Skilling Australia’s Defence Industry program

11. The Skilling Australia’s Defence Industry (SADI) program provides funding support for training or skilling activities in trade, technical and professional skills in defence industries.

12. The SADI program has a clearly defined objective and eligibility criteria. Key documents, such as guidelines and the assessment process, were provided to potential applicants on the SADI website. The ANAO tested a sample of applications for funding of 350 training activities over the last three SADI rounds and found that Defence followed the approved assessment processes, although record-keeping could be improved in some cases.

13. There are also opportunities to improve the program through communicating to potential applicants the list of eligible courses, improving data collection for support relating to apprentices5, and assessing the benefit of elements of the program such as on the job training.

14. In the last three years, the SADI program has awarded grants totalling $25 million to fund 1743 training activities, 2223 apprentice supervision positions and 752 on the job training positions. However, Defence has struggled to accurately forecast likely demand for the program, which has had a cumulative forecast error of $67 million since its inception. The department’s inability to expend all program funds represents a lost opportunity for potential recipients.

15. The SADI program does not have a performance measurement and reporting framework in place, and Defence has no basis on which to assess whether the program is achieving value for money or meeting its objectives.

Global Supply Chain program

16. The objective of the Global Supply Chain (GSC) program is to provide opportunity for Australian industry, particularly SMEs, to win work in the global supply chains of large multinational defence companies working with Defence.

17. Management arrangements for key aspects of the GSC program have recently been improved. Following a review in 2013, Defence improved the GSC contracts and has been rolling them out with prime contractors. There is now a clearer definition of a GSC ‘contract’ for reporting purposes, and clearer reporting requirements, including a reporting template and expectations for performance.

18. The GSC program is promoted through a range of channels including industry associations, Defence publications and other industry programs.

19. Since the program’s inception, the value and number of GSC contracts has risen but remains concentrated among a small number of companies. Defence has sought to assess the value for money of the program through a return on investment performance indicator, and has calculated that the program’s overall return on investment is higher than the initial target. The program’s performance framework has been improved by linking indicators to outcomes and moving from a ‘best endeavours’ to an activity-based reporting approach. However, the performance indicators do not measure the extent to which a prime’s participation in the GSC program results in work for SMEs that they otherwise would not have obtained, and performance reporting still relies on self-assessment from the participating prime. To reduce the risks associated with a self-assessment approach, Defence could directly approach a sample of SMEs awarded GSC contracts on a periodic basis to validate the self-reported performance of the primes.

20. Industry generally views the GSC program as beneficial, and industry stakeholders have identified some opportunities for improvement through better aligning the program with the Priority Industry Capability areas, developing a closer relationship between Australian primes and their overseas counterparts, and making more data on the program publicly available.

Rapid Prototyping Development and Evaluation program

21. The Rapid Prototyping, Development and Evaluation (RPDE) program was established to accelerate and enhance Australia’s warfighting capability through innovation and collaboration in Network Centric Warfare. Using a partnering arrangement with industry, the RPDE program is delivering important technical guidance, advice and solutions to Defence that may not otherwise be delivered in a timely manner using a conventional acquisition process.

22. The RPDE program has clear and well documented management, advisory and governance arrangements. The arrangements also reflect the collaborative nature of the program, which is intended to involve Defence, defence industry and academia.

23. The RPDE Board has reduced its monitoring of program performance. Current performance reporting to the Board provides minimal information on the RPDE program’s overall performance, and focuses largely on the status of individual program activities at a particular point in time. Further, a 2009 Board resolution makes no mention of the Board having a continuing role in performance monitoring. The ANAO has recommended that Defence clarify the roles of the RPDE Board.

24. Defence has well documented administrative arrangements for its RPDE program activities. However, compliance with key requirements has varied, including in respect to financial approvals.

25. Since 2005, the RPDE program has undertaken 169 activities (112 Quicklooks and 57 Tasks) at a total reported cost of $129 million. The RPDE program seeks to monitor the completion of its individual activities and report their outcomes. However, the program no longer produces an annual report on its activities and program-level performance monitoring and reporting is limited.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.15 |

The ANAO recommends that Defence:

Defence’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 5.15 |

To provide assurance about the governance of the Rapid Prototyping, Development and Evaluation program (RPDE), the ANAO recommends that the new RPDE program Relationship Agreement and Standing Offer clearly sets out the roles of the RPDE Board, and that Defence ensures that the Board’s activities are consistent with the specified roles. Defence’s response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity responses

26. The proposed audit report was provided to Defence, with extracts provided to the Defence industry primes Finmeccanica, Boeing Defence Australia, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, BAE Systems, Thales, and Northrop Grumman.

27. Defence, Raytheon and BAE Systems provided formal responses to the proposed audit report for reproduction in the final report. Summaries of these responses are set out below, with the full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Department of Defence

Defence thanks the Australian National Audit Office for conducting the audit of Defence Industry Support and Skill Development Programs. Defence accepts both recommendations and has already made significant progress on the implementation of the recommendations relating to the Rapid Prototyping, Development and Evaluation Program. Defence sees both recommendations contributing to management of its industry support and skills development programs.

Defence remains dedicated to building an enduring partnership with Australian industry and as noted in this report, has implemented a large number of investment and support programs to help achieve this objective. The upcoming Defence White Paper, together with the Defence Industry Policy Statement, will articulate the future strategic direction of Defence’s partnership with industry.

Raytheon

Raytheon Australia appreciates the opportunity to comment on the extract of the proposed report into Defence Industry Support and Skill Development Programs.

Raytheon Australia is committed to the sustainability of the Australian Defence Industry, and to the development and growth of Australian small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) to enhance Australian industry capability across the sector. Raytheon Australia has a long and successful pedigree in supporting the Department of Defence and the Australian armed forces across a range of programs, including our involvement in the Global Supply Chain Program.

BAE Systems

The vision of GAP [Global Access Program] is to develop a more competitive and technologically advanced Australian Defence industry that mutually benefits the Australian Defence Force, and BAE Systems. We endeavour to deliver this vision by increasing the number of SMEs winning work in the global supply chain of BAE Systems.

The challenges for industry and all of the Prime participants on the Global Supply Chain program are; the extremely competitive international market, the protectionist policies of overseas countries and the impact of offset obligations on the volume and types of opportunities afforded to Australian industry.

What GSC program participants can and do, influence, is; identifying and creating the opportunities, matching suppliers to the opportunities, mentoring and assisting SMEs with their responses, providing targeted and sustained training and development of SMEs and advocating for Australian companies at the highest levels within our organisation. The Australian GSC program is unique in the worldwide Programs of Offsets and Industrialisation in this regard and gives unprecedented exposure to overseas supply chains.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Industry has an important role in supporting the Department of Defence (Defence) and the Australian armed forces, supplying over $5 billion of materiel and equipment each year.6 In the Australian context, eight defence industry prime contractors (primes) deliver approximately 70 per cent of the value of defence materiel annually.7 The industry also includes a number of small to medium enterprises (SMEs).8 Around 29 000 to 30 000 Australians are employed in the defence industry in support of military acquisition and sustainment tasks – around half of whom are employed in SMEs.9

1.2 Successive Australian governments have released Defence Industry Policy Statements to provide industry with an indication of future policy directions. The current Policy Statement, Building Defence Capability – A Policy for a Smarter and More Agile Defence Industry Base, was released in 2010. A new Defence Industry Policy Statement, together with the Defence White Paper 2016, is due for release in 2016.

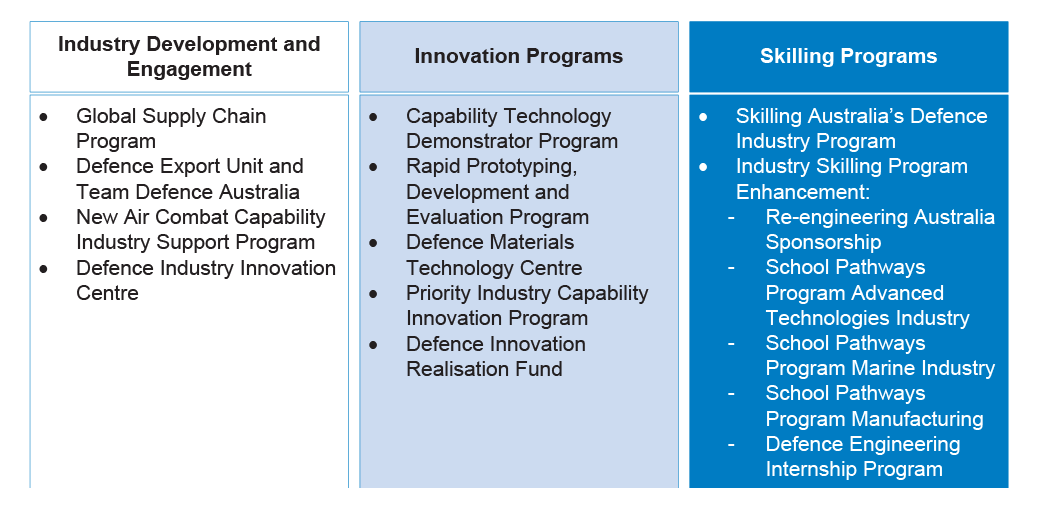

1.3 The 2010 Policy Statement announced that $445.7 million in funding was to be allocated to 19 industry programs over the period 2009–19.10 The then Australian Government committed to increasing the opportunities for, and improving the competitiveness of, the Australian defence industry. Since that time, several of the programs have been discontinued, and other programs11 have been announced. Defence industry programs fall into three categories:

- Industry development and engagement programs – aim to create opportunities to develop and leverage local industry capabilities required by defence, and to ensure that industry is aware of Defence’s capability needs.

- Innovation programs – aim to encourage innovative capabilities, technologies, and processes for Defence.

- Skilling programs – aim to address capacity and capability gaps, including encouraging participation in science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

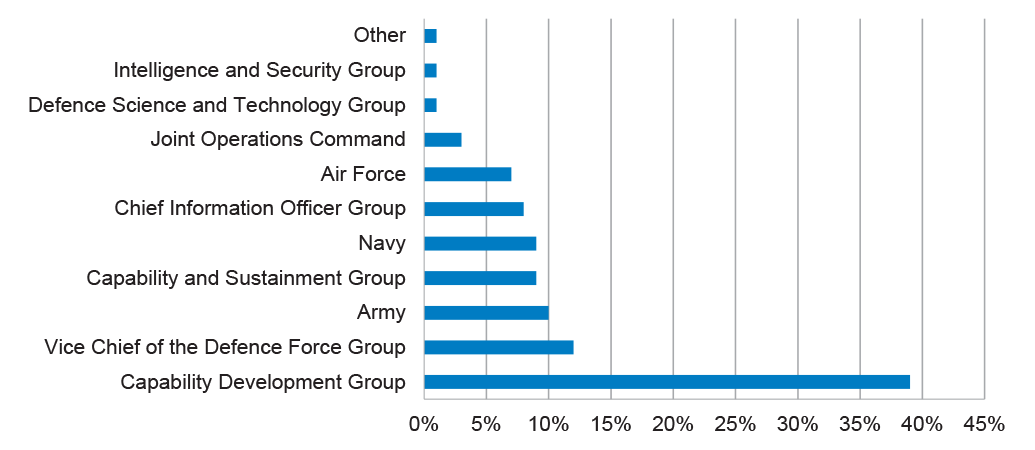

1.4 Most of the programs are now managed by Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group12, with some managed by the Defence Science and Technology Group and the Department of Industry and Science. Figure 1.1 below outlines the 11 main industry programs, categorised according to their type. A description of each of these programs, and details of their administration and funding, is included in Appendix 2.

Figure 1.1: Current main Defence industry support programs by type

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

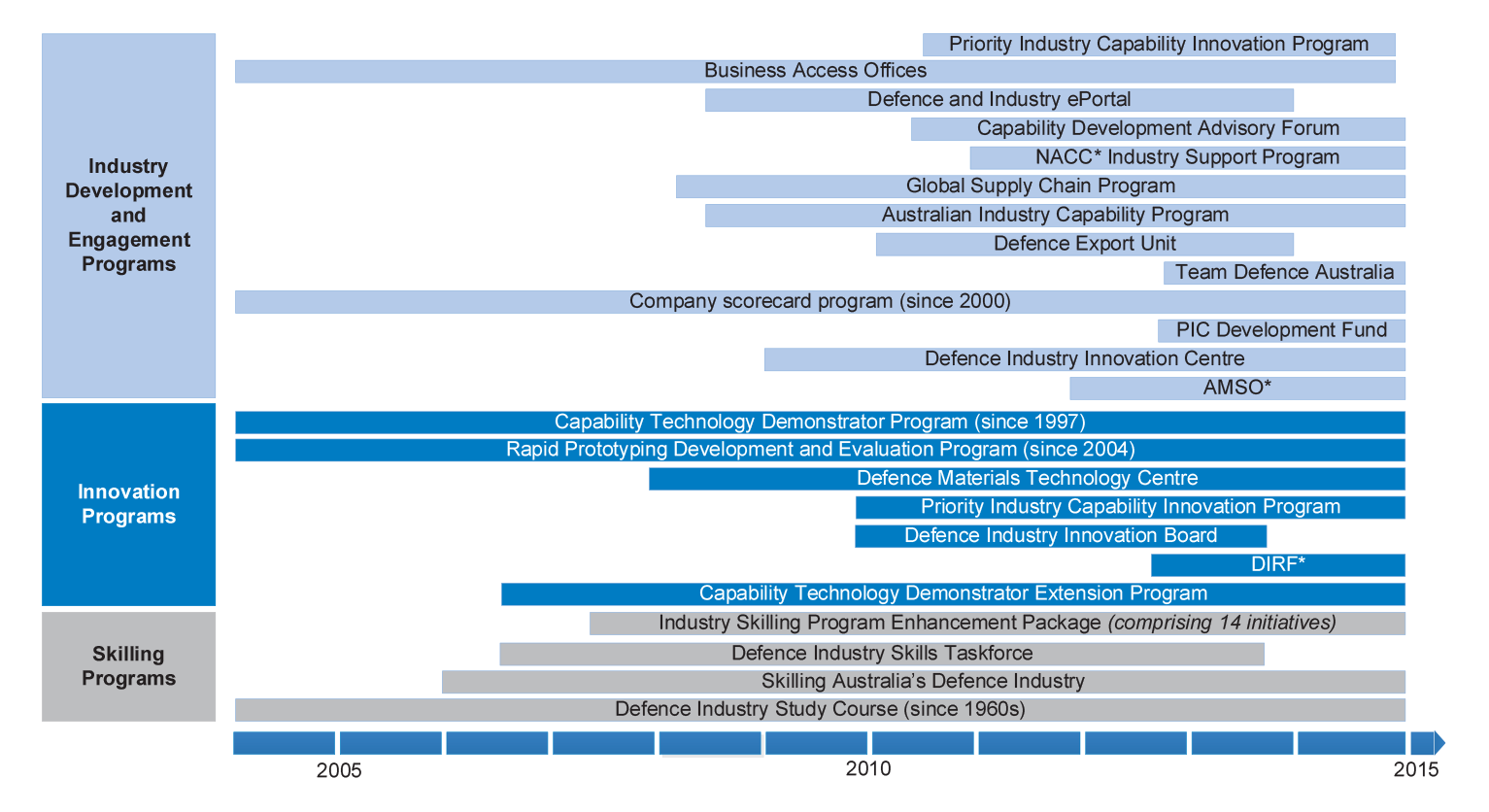

1.5 Defence has administered at least 57 individual industry support programs over the past decade (including the current set of Defence industry programs). To illustrate the spread of programs and provide an indication of timeframes, Figure 1.2 below outlines 25 of these programs by type and duration from 2005 to 2015.

Figure 1.2: Timeline of industry programs by type 2005-2015

Notes: NACC – New Air Combat Capability; AMSO – Australian Military Sales Office; DIRF – Defence Innovation Realisation Fund.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

Audit approach

1.6 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s administration of industry support and skill development programs.

1.7 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- Defence effectively coordinates, promotes and monitors the performance of the suite of industry programs; and

- for the three programs examined in depth, Defence has implemented sound management arrangements for the programs; and the programs are meeting their objectives.

1.8 The audit scope included an assessment of Defence’s overall approach to its industry support and skill development programs including their objectives, funding and administrative arrangements. The audit also included a detailed analysis of three higher value programs managed by Defence: the Skilling Australia’s Defence Industry grant program; the Global Supply Chain program; and the Rapid Prototype Development and Evaluation program. These programs each fall into one of the three categories of Defence industry programs, illustrated in Figures 1.1 and 1.2.

1.9 The audit involved analysis of Australian Government and Defence policies, manuals and procedures relevant to the industry programs, including grant program policies and guidance, and a review of records held by Defence in relation to the development of guidelines, administration of the programs and adherence to the guidelines. The audit team also conducted interviews with key Defence staff, and met with industry stakeholders (including primes, SMEs and industry groups) involved in the programs.

1.10 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $569 000.

2. Governance arrangements for Defence’s industry programs

Areas examined

This chapter examines Defence’s:

• coordination and promotion of industry programs; and

• arrangements for program performance monitoring and evaluation.

Conclusion

Defence has not implemented an overarching framework to help coordinate its management of the large number of government industry support programs and monitor their alignment with the goals of the Australian Government’s Defence Industry Policy Statement. For many of the programs, the direct benefits to Defence are not measured and there are shortcomings in the relevant performance frameworks. As a result it is difficult for Defence to assess: whether a program’s outcomes are meeting its objectives; the value for money of these programs; or an individual program’s contributions to the achievement of the Policy Statement.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made a recommendation aimed at strengthening the performance framework for Defence industry programs.

Does Defence effectively coordinate and promote its range of industry programs?

Defence has administered a large number of small programs over the last five years without an overarching framework to help coordinate activity. These programs have been managed and administered by various areas within Defence and other government departments, and include involvement from industry and research agencies.

There was limited and inconsistent information available about Defence’s industry programs through their websites.

2.1 Current Defence industry programs are administered by three Defence groups13; other government agencies; and contractors. There is no one area within Defence responsible for coordinating the suite of industry programs. The number of Defence industry support programs and the diffusion of administrative responsibility places a premium on the effectiveness of Defence’s coordination arrangements. This issue has been noted by a number of Defence reviews over the last several years including the recent review of industry programs undertaken by PricewaterhouseCoopers in preparation for the next Defence Industry Policy Statement.14

2.2 Defence communicates with industry on its range of industry programs through various channels including Defence publications such as the Defence magazine, forums, engagement with Defence industry groups, Business Access Offices, the Defence Industry Innovation Centre and the websites for its individual industry programs.

2.3 An ANAO review of 28 program websites15 indicated that the information provided was limited and inconsistently presented. In summary:

- program information was difficult to find without a single point of entry, websites were located on eight different domain names, and there was inconsistent presentation of information across those websites;

- six of the programs did not have websites, and public information on these programs was difficult to find16; and

- several websites had links that are no longer active.

2.4 While Defence has made some attempts to coordinate the range of industry programs, and better communicate these programs to industry, the attempts have not always been successful:

- The Defence and Industry ePortal was established in 2008 to help Australian industry, particular Small to Medium Enterprises (SMEs), advertise their capabilities and access information on industry programs. At that time it was intended that the functionality of the ePortal would be broadened to allow Australian industry to provide confidential feedback on Defence’s industry policies and programs. The Defence and Industry ePortal was subsequently closed, on 1 December 2014, due to the expense of maintenance and limited utility for industry users.

- The 2010 Defence Industry Policy Statement established the Defence Industry Innovation Board to better coordinate and communicate the range of industry programs. The board was suspended in 2014 pending revisions to its membership and terms of reference.17

2.5 Notwithstanding Defence’s efforts to date to promote and coordinate its industry programs, the suite of programs remains fragmented. The report on community consultation for the development the upcoming Defence White Paper noted this fragmentation and the lack of awareness among industry of the programs.18

2.6 Implementing a uniform approach to the planning and management of the programs was recommended by the 2012 internal review of the Industry Programs Financial Reconciliations. In October 2015, Defence confirmed that it had not implemented a uniform management approach across the industry programs, as recommended by the review.

Does Defence adequately monitor the performance of its industry programs?

Defence does not adequately monitor program performance at a collective or, in most cases, at an individual level. Only a few of the programs report on performance and outcomes. The others do not undertake any reporting against KPIs or assess how they are meeting the program objectives. Not tracking performance for the programs means that Defence cannot assess whether program outcomes are meeting defined objectives, or the contribution made by individual programs towards achieving the overall objective of the Australian Government’s Defence Industry Policy Statement.

Performance indicators and targets for the industry programs in the Portfolio Budget Statements are not meaningful

2.7 Performance information plays an important role in assessing program effectiveness. The industry programs in the 2015–16 Defence Portfolio Budget Statements are included under: Outcome 1: Contributing to the preparedness of Australian Defence Organisation through acquisition and through-life support of military equipment and supplies; and Programme 1.3 Provision of Policy Advice and Management Services. The program’s objective, Key Performance Indicators (KPI) and performance targets are included in Table 2.1 below.

Table 2.1: Defence Materiel Organisation 2015–16 Outcome 1 and supporting Programme 1.3 Objective, KPIs and performance targets

|

Outcome 1: Contributing to the preparedness of Australian Defence Organisation through acquisition and through-life support of military equipment and supplies |

|

|

Programme 1.3 Objective |

Programme 1.3 KPIs and performance targets |

|

The DMO will meet Government, Ministerial and Departmental expectations and timeframes for the provision of policy, advice and support and delivery of industry programmes. |

The DMO is meeting Government, Ministerial and Departmental expectations and timeframes for provision of policy, advice and support and delivery of industry programmes. Programme 1.3 performance targets include:

|

Note: The 2015–16 Defence Portfolio Budget Statements also list a range of industry development initiatives under the Programme 1.3 performance target.

Source: 2015–16 Defence Portfolio Budget Statements.

2.8 In 2015–16, the KPIs and performance targets included in Defence’s Portfolio Budget Statements did not provide a useful basis for reporting on performance in the Department’s next annual report, and Defence would need to expand its performance reporting in the 2015–16 annual report to provide the parliament and stakeholders with a meaningful assessment of its administration of industry programs.

Performance monitoring at the program level is variable

2.9 Table 2.2 below provides a summary of the ANAO’s assessment of the objectives, performance measures, reporting and monitoring arrangements for current key Defence industry programs.

Table 2.2: Defence industry programs – objectives, performance measures and monitoring

|

Program |

Objectives clearly identified? |

KPIs linked to program objectives? |

Regular reporting against KPIs? |

Regular monitoring of program? |

|

Priority Industry Capability Innovation Program |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Team Defence Australia |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Re-Engineering Australia Sponsorship |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

|

New Air Combat Capability Program |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

Engineering Internship |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

School Pathwaysa: |

||||

|

Advance Technologies Industry (SA) |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

|

Marine Industry (WA) |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Manufacturing (NSW) |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

|

Skilling Australia’s defence industry (SADI)b |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

|

Global Supply Chain (GSC)b |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Rapid Prototyping, Development and evaluation (RPDE)b |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Note a: The School Pathways initiative has three programs based in three states aimed at introducing students to the skills required for defence industry careers. The ANAO examined the performance monitoring and evaluation for these three programs separately.

Note b: The SADI, GSC or RPDE programs are assessed in Chapters 3, 4 and 5 respectively.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

2.10 In summary, objectives have been clearly identified for each of the industry programs reviewed by the ANAO. For the majority of programs, performance measures are poorly aligned to program objectives and monitoring and reporting arrangements have either not been implemented or are not regular. Shortcomings in the performance framework were identified as an issue in the internal review of industry programs for the upcoming Defence White Paper, which noted that programs had ‘only loose connections back to Capability Managers, with limited KPIs to assess value and performance’19 This was particularly a problem for the skilling programs.

2.11 The current performance framework limits Defence’s capacity to: monitor program performance; assess the achievement of value for money; and assess program outcomes against objectives. The framework also provides limited transparency and assurance to government, Parliament, and stakeholders.

The operating context for the defence industry programs is changing

2.12 Defence has begun implementing the recommendations of the April 2015 Defence First Principles Review, which included significant organisational design changes. The review noted a number of organisational units had emerged within Defence doing work that may be more efficiently carried out by other areas of government, or not at all. The review also drew attention to the Industry Division within the then Defence Materiel Organisation, suggesting that the division’s roles and functions should be transferred to the Department of Industry so as to better position defence industry within the broad Australian industrial landscape.20

2.13 As discussed, a new Defence White Paper is expected to be released in 2016. The White Paper is expected to be accompanied by a new Defence Industry Policy Statement. In preparation, Defence tasked PricewaterhouseCoopers with recommending a streamlined and more coherent suite of Defence industry programs in accordance with Defence priorities.

2.14 As a result of the structural changes to Defence and likely defence industry policy changes, the operating context for the industry programs is also likely to change. These developments provide an opportunity for Defence to reconsider its overarching management and coordination arrangements for the industry support programs, and to address weaknesses identified in this audit, particularly in regards to a meaningful performance framework for the programs, consistent with the new Commonwealth Performance Management Framework.21

Recommendation No.1

2.15 The ANAO recommends that Defence:

- assesses the performance of Defence industry support programs and their contribution to achieving the intended outcomes of the Australian Government’s Defence Industry Policy Statement; and

- monitors and reports on the performance of each industry program against clear targets, based on measurable performance indicators.

Defence’s response: Agreed.

3. Skilling Australia’s Defence Industry Program

Areas examined

This chapter examines the:

- management arrangements for the Skilling Australia’s Defence Industry (SADI) program; and

- performance of the program.

Conclusion

The SADI program has been administered consistently with key elements of the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines and ANAO testing of a sample of applications for funding indicated that Defence was applying the documented assessment processes. The ANAO also identified some opportunities to improve program administration including documentation of key decisions, performance measurement and forecasting.

The SADI program does not have a performance measurement and reporting framework, and Defence has no basis for assessing program outcomes or value for money. Defence has also struggled to accurately forecast likely demand for the program, and there have been consistent underspends in the program in recent years.

Program overview

3.1 The Skilling Australia’s Defence Industry (SADI) program was announced during the 2004 election campaign to address a shortfall in engineers, technical trades and project management skills in order to meet future Defence requirements.22 The program provides funding support for training or skilling activities in trade, technical and professional skills in defence industries. The program is now administered by Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.23 At the time of the audit there were five staff in the SADI team and, when required, contractors assisted in the assessment process.

3.2 The original budget for the SADI program was estimated at $200 million over a 10 year period. Defence advised the ANAO that the actual expenditure to July 2015 was $54.8 million, a substantial underspend. The structure of the program has changed significantly over its life and has undergone several administrative changes around eligibility, sourcing, type and levels of funding. The key changes for the program over the last decade are summarised in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Key changes in the SADI program 2005–2015

|

Year |

Key changes or events in the program |

|

2005 |

The original 2005–06 budget projecting expenditure of $74.5 million over four years. |

|

2006 |

The 2006–07 Portfolio Budget Statements note that SADI funding is transferred to DMO along with additional funding. |

|

2007 |

The Defence Industry Policy Statement 2007 expands the SADI program to include applications from third parties such as industry organisations. |

|

2011 |

The 2011–12 Portfolio Budget Statements mention grants for the first time. The 2011–12 round was the first administered as a ‘grants’ program. |

|

2012 |

Defence runs two grants rounds to get more coverage and better align with training semesters. |

|

2014 |

SADI program funding changed from reimbursement to upfront payment method. |

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.3 It was originally intended to fund SADI by accessing contingency risk funding built into major projects. In practice, the SADI program was funded from Defence’s Departmental Budget. As noted in Table 3.1, in 2011 the program was changed to a grant program in response to the introduction, in July 2009, of the new Commonwealth Grant Guidelines by the then Department of Finance and Deregulation.

The future of the SADI program

3.4 Since 2011 Defence has administered five SADI grants rounds. Defence entered into an agreement with the Department of Industry and Science to administer the 2015 round for the program. Defence informed the ANAO that the Department of Industry and Science has systems in place that mean it is better suited than Defence to administer the 2015–16 SADI round. A Memorandum of Understanding between the departments has been signed but the schedules were still being negotiated as at October 2015. As of October 2015, the cost to Defence of program administration was $603 000 for 2015–16.

3.5 In June 2015, the Minister for Defence extended the program for an additional year (resulting in a funding round for 2015–16). This round opened on 27 July 2015. A decision on the future of the program will be made when the upcoming Defence Industry Policy Statement and Defence White Paper are released.

Has Defence implemented sound management arrangements for the SADI program?

The SADI program has a clearly defined objective and eligibility criteria. Key documents, such as guidelines and the assessment process, were provided to potential applicants on the SADI website. The ANAO tested a sample of applications for funding of 350 training activities over the last three SADI rounds and found that Defence followed the approved assessment processes, although record-keeping could be improved in some cases.

There are also opportunities to improve the program through communicating to potential applicants the list of eligible courses, improving data collection for support relating to apprentices, and assessing the benefit of elements of the program such as on the job training.

The SADI program’s objectives are clearly defined

3.6 The objectives of the SADI program have changed over time. Since 2011, the objectives have been:

to support defence industry to increase the quality and quantity of skilled personnel available through training and skilling activities in trade, technical or professional skill sets where that training is linked to a defence capability. This will support the Australian Defence Force in acquiring the capabilities it needs to defend Australia and its national interests.

The SADI Program has three main objectives:

- generating additional skilled positions;

- upskilling existing employees; and

- increasing the quality and quantity of skills training.24

The SADI program has clearly defined eligibility criteria

3.7 The Commonwealth grants framework requires grant programs to have straightforward and easily understandable eligibility criteria. The SADI program guidelines include clear high level criteria relating to the eligibility of the company and the type of training activity (see Table 3.2).

Table 3.2: High level criteria for the SADI program

|

|

|

The entity must: |

|

|

The training activity must: |

|

Source: Department of Defence, Skilling Australia’s Defence Industry Program Guidelines, 2014–15 Round One, pp. 9–10.

3.8 The SADI guidelines have also outlined the particular costs that can, and cannot, be covered by the program funding. For example, in the 2014–15 guidelines, online training course fees and interstate and international travel were allowed while taxis and wages of employees attending were not. The list of items provided was not exhaustive and allowed for some flexibility in the claims.

Promotion of the program to industry is mainly via the internet

3.9 The SADI program has primarily been publicised on the internet, with the SADI website providing a range of information including details of the successful applicants dating back to 2008–09.25 For each round, key documents were made available on the website: SADI program guidelines, the SADI draft funding agreement and a frequently asked questions sheet for completing the application. The guidelines included a brief outline of the assessment process.

Defence has used a grant management system over the last three rounds

3.10 The use of a well-designed automated Grant Management System can assist in monitoring the progress and outcomes of grants. Defence purchased a Grant Management System for use with the SADI program at a cost of $921 755. This system does not provide any connectivity to other defence systems, such as Defence’s primary record management system Objective, meaning that manual work around by staff was needed to complete an application round.

3.11 Prior to 2012–13, all applications were paper based and companies were required to provide hard copies of brochures and quotes. Since the second round in 2012–13, Defence has required that SADI applications be completed using the online Grant Management System. Defence informed the ANAO that it made allowances in quality and the amount of information provided for in 2012–13 applications, to provide applicants some flexibility. Defence further advised that since then, there has been a strict enforcement of the guidelines and this has meant that some applications were rejected due to the lack of supporting material or descriptive evidence required to fully assess them.

Defence assessed applications according to the published guidelines

Funding priorities

3.12 The SADI guidelines have over time included the criteria used for deciding funding priorities. Skilling activities that support a Priority Industry Capability26 are to be given precedence over other activities. In the last three application rounds, a total of $7.36 million (29 per cent) was awarded to training activities in industries that Defence accepted were Priority Industry Capability related. Where a company self-identified Priority Industry Capability relevance in their application the applications were sent to the relevant Defence team for further evaluation. An analysis of the data shows that Defence’s system for such evaluation caused no delays in the assessment process.

3.13 A funding cap can be applied where the value of applications exceeds available funds. The only time the funding cap was applied was in 2014–15 and this affected two companies.

Assessment criteria

3.14 The Grant Guidelines require agencies to develop policies, procedures and guidelines for the sound administration of grants.27 Consistent with this guidance, Defence developed a grant assessment plan for use in conjunction with the Grant Management System in 2013–14 and 2014–15. The plan described the assessment process, governance arrangements and the documentation required to evidence the assessment process. The plan also outlined how applications would be assessed and selected for funding. Defence also included:

- in the SADI guidelines for each year, a brief summary of the assessment process that would take place;

- a merit ranking during the assessment for the 2014–15 round in case funding cap decisions may be required. Each training activity was given a ranking from 1 (Eligible– PIC Relevant) to 5 (not eligible); and

- a conflict of interest form to be signed by each staff member who completed the in-house training.

ANAO testing of a sample of applications

3.15 The ANAO examined a sample of applications relating to the funding of 350 training activities and 109 company applications. The ANAO focussed on Defence’s assessments for application eligibility and training activity eligibility. Each application was required to include an external training activity quote and on the job training summary. No additional information was required for apprentice supervision support.28 For each criterion the ANAO considered whether the documentation required under the SADI guidelines was provided, and whether it matched the description in the application. The quotes provided in the application were also compared with the attached documents to see if they matched. The outcomes of the ANAO’s testing are set out below.

Table 3.3: ANAO sample of applications

|

|

2012–13a |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

Total |

|

Number of companies that applied |

55 |

58 |

58 |

109b |

|

Number of training activities requested |

95 |

119 |

136 |

350 |

|

Training activities approved |

67 |

94 |

79 |

240 |

|

Number of students requested |

422 |

556 |

648 |

1,626 |

|

Number of students approved |

289 |

362 |

309 |

960 |

|

Requested Activity Amount ($m GST exclusive) |

1.15 |

2.29 |

1.63 |

5.07 |

|

Funded amountc ($m GST exclusive) |

0.716 |

1.33 |

0.721 |

2.77 |

Note a: The figures for 2012–13 refer to round 2 applications. Round 1 applications for 2012–13 were not assessed by the ANAO.

Note b: Some companies applied in more than one year.

Note c: The funded amount is the dollar value agreed to in the signed funding agreement.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

|

Box 1: ANAO sample of applications |

|

Company eligibility For the three rounds reviewed by the ANAO, six companies were found by Defence to be ineligible. One was a late application and the others did not have the required Defence contract. Records of the assessment of companies’ eligibility for SADI grants were made, but not always saved in Objective by the assessors, as required. Training activities For the ANAO sample, 66 per cent of training activities were approved. The quality of the decision records was mixed: some records were detailed and others lacked certain information. For example, for around 10 per cent of assessments there was a lack of detail included in the records for rejected applications for training activities. Not all assessors recorded details of the reasons for rejecting training activities, or the specific sections of the guidelines which referenced why particular training activities were rejected. |

Issues warranting further examination by Defence

3.16 The ANAO noted a number of issues to do with the SADI program that warrant further examination by Defence, relating to the consistency of funding decisions, and consulting with stakeholders on opportunities to streamline administrative arrangements.

|

Box 2: Issues warranting further examination by Defence |

|

Inconsistent funding decisions The ANAO identified several cases where particular training courses or activities were initially rejected and then accepted in subsequent rounds, and vice versa. For example, at various times the following courses were both rejected and accepted for different rounds and different companies:

Opportunities for streamlining administrative arrangements As indicated below in Table 3.4, there is a low rate of success for on the job training applications (37 per cent of the amount requested has been funded) compared to companies applying for other training activities (a success rate of 61 per cent for external training activities and 81 per cent for apprentice supervision positions). One company interviewed by the ANAO advised that the reason it did not apply for on the job training was the complexity of the application process. The company highlighted that Defence required evidence of log books and supervisor costings, when other training activities only required a quote and course description. |

|

In 2014–15, the method for payment was changed from a reimbursement model to an upfront payment to applicants with repayment of unused funds to Defence. This change allowed applicants to change and adjust their studies without additional administrative burden. Companies interviewed by the ANAO provided mixed responses on the benefit of the change, with some indicating that it did not necessarily improve SADI’s administrative processes. These examples indicate that there would be benefit in defence periodically consulting with key stakeholders on opportunities to further streamline administrative processes.a |

Note a: Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines, effective from 1 July 2014, p. 15.

3.17 On the question of consistency, Defence advised the ANAO in December 2015 that:

… funding decisions are based on each specific application, and the relative merit of the applicants claims. Whilst this may give an appearance of inconsistency, it actually reflects the complexity of a fully considered assessment process.

At times it may appear that there is inconsistency in decisions relating to a particular course title across years because an activity is funded in one year and not in another, but there are a range of factors beyond the course name which influence eligibility. The various criteria for determining activity eligibility can also result in a particular course being supported for one applicant, but not another, as a company has not met all the eligibility criteria in their application. The eligibility of a training activity is assessed on the qualitative analysis of the information provided as well as determining that the required supporting evidence is provided.

What has been the performance of the SADI program?

In the last three years, the SADI program has awarded grants totalling $25 million to fund 1743 training activities, 2223 apprentice supervision positions and 752 on the job training positions. However, Defence has struggled to accurately forecast likely demand for the program, which has had a cumulative forecast error of $67 million since its inception. The department’s inability to expend all program funds represents a lost opportunity for potential recipients.

The SADI program does not have a performance measurement and reporting framework in place, and Defence has no basis on which to assess whether the program is achieving value for money or meeting its objectives.

Distribution of funds

3.18 Forty per cent of SADI funding over the last three years, totalling $10 million, was awarded to 11 large defence contracting firms—‘primes’.29 Sixty per cent of funding ($15 million) was awarded to 165 SMEs. The primes received an average of $900 000 each, while SMEs averaged $90 000. Table 3.4 provides an overview of the applications for the last three rounds of SADI.

Table 3.4: Applications summary for the last three rounds of SADI

|

All training activities |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

Total |

|

Number of companies that applied |

128 |

133 |

118 |

194a |

|

Funding applied for ($m GST exclusive) |

12.46 |

18.55 |

17.51 |

48.52 |

|

Funding awarded ($m GST exclusive) |

6.92 |

11.21 |

6.55 |

25.47 |

|

External training activities |

||||

|

Number of training activities applied for |

779 |

942 |

1103 |

2824 |

|

Number of activities awarded funding |

513 (65%) |

701 (74%) |

530 (48%) |

1743 (61%) |

|

Funding awarded ($m GST exclusive) |

4.64 |

6.95 |

4.42 |

16.02 |

|

Apprentice supervision positions |

||||

|

Number of positions applied for |

586 |

1248 |

901 |

2735 |

|

Number of positions awarded funding |

564 (96%) |

968 (77%) |

680 (75%) |

2223 (81%) |

|

Funding awarded ($m GST exclusive) |

1.53 |

2.5 |

1.6 |

5.63 |

|

On the job training |

||||

|

Number of students requested |

367 |

538 |

1110 |

2015 |

|

Number of students funded |

118 (32%) |

374 (70%) |

260 (23%) |

752 (37%) |

|

Funding awarded ($m GST exclusive) |

0.75 |

1.75 |

1.3 |

3.81 |

Note a: Some companies have applied for multiple rounds over the last three years.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.

Not all SADI program funding has been spent

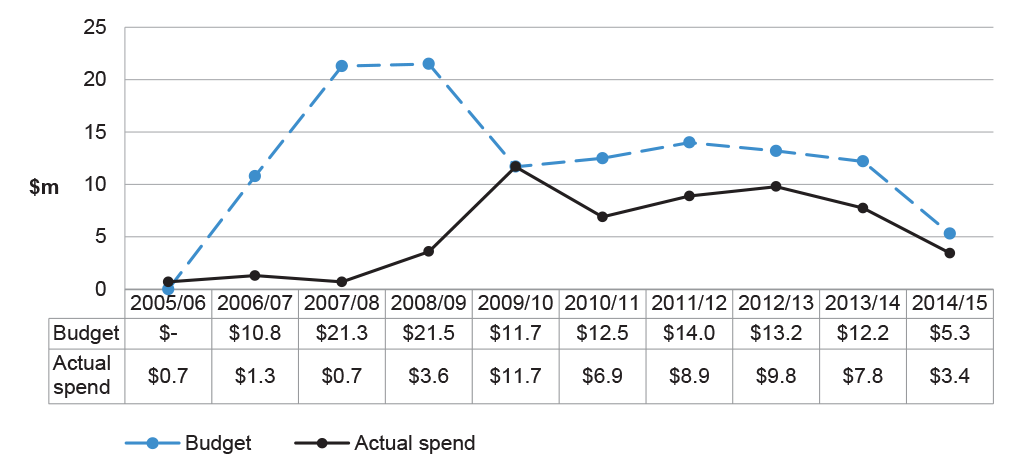

3.19 Since the program’s inception, it has had a cumulative forecast error of over $67 million. The gap between budgeted and actual expenditure was greatest prior to SADI being treated as a grant program. However, there has still been a consistent underspend in recent years (see Figure 3.1), pointing to ongoing difficulties in Defence’s ability to forecast likely demand for the program. The Department’s inability to expend available program funds represents a lost opportunity for potential recipients. For example, if all of the $67 million had been expended on apprentice supervision, approximately 3300 more positions could have been supported under the program.

Figure 3.1: SADI budget and expenditure 2005–06 to 2014–15

Note: The 2006-07 Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements allocated an additional $0.3 million to the SADI program.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

3.20 The program has been included in a number of Defence internal reviews over the past five years. The findings of these reviews identified shortcomings in the management and administration of the program including around strategy, planning, communication arrangements and performance monitoring.

There is no performance monitoring and reporting framework for the SADI program

3.21 No performance measures were developed for the SADI program when it was established, and no effort has been made to develop a performance framework for the program. As a consequence, while the program’s objectives are clearly stated in the program guidelines, there are no KPIs to measure how well Defence is meeting these objectives or to assess Defence’s administrative performance.

3.22 To comply with the Grant Guidelines agencies have to take into account the principle of achieving value with relevant money.30 In the sample of grants the ANAO examined, some companies’ applications had been rejected or had their funding amounts reduced as a result of a value for money assessment.31 However, at a strategic level there has been no assessment of the program’s overall value for money, and the absence of any performance measures for the program means that Defence has no basis for making such an assessment.

3.23 Defence advised the ANAO that it was ‘too difficult to develop performance measures during the life of the program’ and that performance information could be resource intensive to collate. The ANAO considers that the main objective of SADI (see paragraph 3.6) is measurable, and Recommendation No.1 in this performance audit report (see paragraph 2.15) should apply to the SADI program and any future programs of this nature.

4. Global Supply Chain program

Areas examined

This chapter examines the:

- management arrangements for the Global Supply Chain program; and

- performance of the program.

Conclusion

Defence has recently improved its administration of key aspects of the GSC program, including contracts and the performance framework. However, the new performance framework is still being implemented and the impact and benefit to Defence of the GSC program remains largely unassessed. Program performance data under the new performance framework relies on unvalidated self-reporting by the participating multinational prime contractors. The program is promoted widely to industry and industry generally sees the program as beneficial.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made a suggestion aimed at reducing the risks associated with the self-assessment approach to the new program performance framework.

Program overview

4.1 The objective of the Global Supply Chain (GSC) program is to provide opportunity for Australian industry, particularly Small to Medium Enterprises (SMEs)32, to win work in the global supply chains of large multinational defence companies working with Defence (‘primes’). This, in turn, aims to facilitate sustainment of a capable defence industry to support Defence’s needs.

4.2 In 2007 Boeing received $2 million in funding from Defence to form Boeing’s Office of Australian Industry Capability. The intention was that Boeing would work with Defence to identify globally competitive Australian companies and facilitate the release of bid opportunities for those companies to supply Boeing. Defence advised that this activity led to orders for Australian companies worth around $20 million.

4.3 In July 2009 the then Government announced the GSC program to assist other defence multinationals set up GSC teams within their offices, and assigned a budget of $59.9 million over ten years.33 Defence advised the ANAO that 115 SMEs have been involved with the program and they had entered into 664 contracts totalling $713 million.34 Funding for the GSC program was reduced in 2013, and the forthcoming Defence White Paper and Defence Industry Policy Statement are expected to clarify the funding source and level for the program.

4.4 Under the GSC program, Defence funds small teams within the primes to identify bid opportunities across their defence and commercial business units and advocate inclusion of Australian industry on bid requests. The engagement and funding of primes to participate in the program is effectively exempt from the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.35 In addition to providing bid opportunities, the GSC primes are required to advocate on behalf of Australian industry, train and mentor companies in the primes’ purchasing practices and methods, and provide a range of market assistance including facilitating visits and meetings with key decision makers.

4.5 In early 2015, Defence engaged consultants PricewaterhouseCoopers to review the range of Defence industry programs to inform the development of the upcoming Defence White Paper and the Defence Industry Policy Statement. The review recommended that the GSC program be delivered by the Department of Industry and Science.

Has Defence implemented sound management arrangements for the GSC program?

Management arrangements for key aspects of the GSC program have recently been improved. Following a review in 2013, Defence improved the GSC contracts and has been rolling them out with prime contractors. There is now a clearer definition of a GSC ‘contract’ for reporting purposes, and clearer reporting requirements, including a reporting template and expectations for performance.

The GSC program is promoted through a range of channels including industry associations, Defence publications and other industry programs.

The agreements between Defence and the primes have been improved

4.6 In 2013, Defence engaged a contractor to review the GSC program, including its current effectiveness and future opportunities. The report (known as the Wilton review) was finalised in October 2013, and made 20 recommendations aimed at improving the GSC program including recommendations to improve the performance framework36 and increase the pool of SMEs engaged in the program.

4.7 Following the Wilton review, the deed and annex arrangements with the participating primes were replaced with GSC agreements. Table 4.1 below outlines the key differences between the previous deed and annexes and the new GSC agreements.

Table 4.1: Key differences between previous deed and annex arrangement with the primes and new GSC agreements

|

Previous deed and annex arrangement |

New GSC agreement |

|

Type of arrangement |

|

|

The deed was an umbrella agreement, and there were annexes with defined activities to be undertaken by the prime. |

Single agreement to manage the relationship with the prime. |

|

Definition of a GSC contract |

|

|

The scope of a GSC ‘contract’ for reporting purposes was not defined in the annex or the deed. |

The scope of a GSC contract for reporting purposes is now clearly defined. Australian subsidiaries of the prime are now excluded for reporting purposes. |

|

Performance reporting and assessment |

|

|

Reporting was largely subjective (a ‘best endeavours’ approach) and activity based, not linked to performance. |

Performance now reported against defined expectations, and linked to renewal of agreements. |

|

Primes required to have a biannual program management review to report on the performance and outcomes of all activities. |

Prime required to report to the Australian Government on a quarterly basis in addition to a biannual program management review. |

|

Not explicitly stated how the Australian Government will assess outcomes of program management reviews. |

Clearly states how the Australian Government will assess the performance reporting information provided by primes. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

4.8 The change from the deed and annex arrangement to a GSC agreement has led to:

- a clearer definition of the scope of a GSC contract for reporting purposes; and

- clearer reporting requirements including a reporting template, expectations for performance and a better understanding of how performance will be assessed by the Australian Government (performance reporting for the program is discussed in the following section).

4.9 In August 2014, the first participating prime signed the new agreement, and by October 2015 a further three primes had also signed agreements. Defence advised the ANAO that, for the remaining three primes, the previous contractual arrangements continued to apply and that negotiations were underway about moving to the new agreements. Defence expects this process to be completed by September 2016.

The funding arrangements are complex

4.10 Since the 2010 Policy Statement through to April 2015, the total funding commitment for the GSC program was $59.9 million compared to actual expenditure of $41 million. Funding for the GSC program was originally a combination of: program funding to initiate arrangements with multinational prime companies; and funding from projects awarded to the respective prime contractors. Defence informed the ANAO that this approach created administrative issues for the program, as project offices did not always allocate a discrete funding line for the GSC program (although project offices are required to do so under the Defence Capability Plan37).

The program has been promoted widely and industry has been forthcoming in providing feedback

4.11 Defence promotes the GSC program widely, through:

- industry associations;

- Defence’s external website;

- Business Access Offices;

- the Defence Industry Innovation Centre;

- Austrade; and

- Team Defence Australia trade missions and exhibitions and major Defence shows and conferences.

4.12 GSC forums are also held biannually, and include attendees from Defence and each of the primes’ GSC teams. Topics discussed include any updates to the GSC program, the global supply chain environment and activities of the primes.

4.13 Defence informed the ANAO that until very recently, feedback from SMEs on the program has been largely anecdotal, with the GSC team receiving feedback from SMEs and primes when accompanying the primes on site visits to SME offices.38

4.14 In June 2015, the GSC team interviewed 17 SMEs currently engaged in the GSC program, that have been awarded one or more contracts or have the potential to be awarded contracts in the future. These interviews were conducted in order to understand the impact of the GSC Program on SMEs and to assess the SME’s relationship with the prime under the program.39 The responses from the SMEs included:

- mixed opinions on the quality of feedback provided to the SMEs by the primes. Some SMEs reported seeking feedback and received none, others reported receiving confusing or unclear feedback, and some were satisfied with the feedback received.40

- mixed opinions on the marketing efforts of the prime representatives. SMEs with high-end technology reported that prime representatives did not understand their capability, and highlighted the importance of the primes involving technical experts.

- positive views were expressed by many of the SMEs about the training opportunities provided, and the changes to the program, in particular the new performance framework focussing on program outcomes.

What has been the performance of the GSC program?

Since the program’s inception, the value and number of GSC contracts has risen but remains concentrated among a small number of companies. Defence has sought to assess the value for money of the program through a return on investment performance indicator, and has calculated that the program’s overall return on investment is higher than the initial target. The program’s performance framework has been improved by linking indicators to outcomes and moving from a ‘best endeavours’ to an activity-based reporting approach. However, the performance indicators do not measure the extent to which a prime’s participation in the GSC program results in work for SMEs that they otherwise would not have obtained, and performance reporting still relies on self-assessment from the participating prime. To reduce the risks associated with a self-assessment approach, Defence could directly approach a sample of SMEs awarded GSC contracts on a periodic basis to validate the self-reported performance of the primes.

Industry generally views the GSC program as beneficial, and industry stakeholders have identified some opportunities for improvement through better aligning the program with the Priority Industry Capability areas, developing a closer relationship between Australian primes and their overseas counterparts, and making more data on the program publicly available.

Defence collects data on the number and value of GSC contracts, but this should be read with care

4.15 The number, and value, of GSC contracts has risen over time. As discussed, Defence has advised that 115 SMEs had participated over the life of the program, with 664 contracts entered into. Table 4.2 (below) summarises these reported results, totalling $713 million and shows that there is a strong correlation between the length of time a prime has participated in the program, and the number and value of SME contracts that had been reported. The ANAO observed that:

- over three quarters (76.4 per cent) of the value of all GSC contracts have been awarded to six SMEs. A 2013 review also noted the concentration of contracts and recommended the GSC program adopt a target to substantially increase the pool of prime-contractor-ready SMEs, from the existing base of 64 to a 5-10 fold larger pool within a five year period. In the two years since the review, the number of SMEs with a GSC contract has nearly doubled, rising to 113 at 30 June 2015.

- as of September 2014, 57 GSC contracts (12 per cent) worth $119 million (some 18 per cent of the total value of all GSC contracts) had been awarded to subsidiaries of the participating primes.

4.16 The new agreements with the participating primes include a program ‘return on investment’ performance indicator. Defence has defined this indicator as the ratio of Australian Government expenditure41 over the term of the company’s participation in the GSC Program, against the total value of contracts awarded to Australian SMEs by the participating prime. Defence set performance bands ranging from poor (less than 2:1), fair (between 2:1 and 10:1), good (between 10:1 and 20:1), to superior (greater than or equal to 20:1).42 As Table 4.2 below illustrates, the performance of the GSC primes varies widely.

Table 4.2: GSC primes – contract values, payments and return on investment to August 2015

|

Prime |

Months in Program |

Number of contractsa |

Value of awarded contracts ($m) |

GSC Payments ($m) |

Return On Investmentb |

|

Finmeccanica |

28 |

8 |

0.436 |

2.763 |

-c |

|

Lockheed Martin |

41 |

30 |

33.52 |

4.959 |

6.8 |

|

BAE Systems |

41 |

103 |

6.941 |

4.564 |

1.5 |

|

Northrop Grumman |

45 |

35 |

10.716 |

5.82 |

1.8 |

|

Thales |

59 |

64 |

25.176 |

8.041 |

3.1 |

|

Raytheon |

70 |

114 |

273.665 |

9.328 |

-c |

|

Boeing |

85 |

327 |

362.871 |

14.631 |

-c |

Note a: Includes contracts awarded to the subsidiaries of most participating primes. BAE systems advised that the data does not include any contracts to the BAE systems subsidiaries.

Note b: Return On Investment is one of seven performance measures used to determine value for money and measure success in the program. The other performance measures include the identification and engagement of new Australian companies, the award of multiple, longer duration contracts, high order work, the delivery of value-add activities and the company’s behaviours in delivering the program.

Note c: Raytheon and Finmeccanica are still operating under the previous agreement that does not include a ‘return on investment’ performance indicator. Defence advised that Boeing is not currently a participant in the program.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence data.

4.17 Program data on the number and value of SME contracts, and the estimated return on investment, should be read with care. The performance indicators do not measure the extent to which a prime’s participation in the GSC program results in work for SMEs that they otherwise would not have obtained. Further, as discussed below, the data relies on unvalidated self-reporting by the primes.

The program performance framework has been improved

4.18 Until 2014, the GSC program employed a ‘best endeavours’ performance reporting framework.43 Under this reporting framework, the program’s key performance indicators (KPIs) largely related to the enabling activities performed in support of industry.44 The 2013 review of the GSC program identified limitations with this ‘best endeavours’ approach to performance reporting, noting that there was: ‘no benchmarking against a specifically articulated strategic vision for the success of the Program, nor operational targets relating to capability building or market access’.45

4.19 Since the 2013 review, Defence has introduced new performance reporting arrangements in conjunction with the new GSC agreements. Defence informed the ANAO in March 2015 that the change in focus is essentially moving the program from one where performance is assessed against ‘activity’ to a framework based on program outcomes and measures of ‘effectiveness’. The new performance monitoring arrangements outlined in the new GSC agreements with participating primes are included in the boxed text below.

|

Box 3: New performance reporting framework |

|

The Company will provide a Report to the Australian Government on a quarterly basis … Each Report will include, in respect of the relevant Reporting Period:

|

Source: Funding Agreement in relation to Defence’s Global Supply Chain Program, sections 4.1.1 and 4.1.2.

4.20 The program performance indicators are now based on the desired outcomes for the program and are tied to industry support contracts. The program performance indicators focus on SME participation, SME contract awards, SME contract values and return on investment. The strategic performance measures include: responsiveness (of the Contractor to all correspondence); relationships between the Prime, the Australian Government and third parties; and performance culture, including the Prime’s ability to transparently deliver the GSC program. Each program performance indicator and strategic performance measure includes assessment criteria, and is provided a performance rating based on predetermined expectations.

4.21 At the time of audit fieldwork, the new performance framework was being implemented and outcomes were yet to be reported. The impact and benefit to Defence of the GSC program therefore remains largely unassessed.

4.22 Participating companies are responsible for conducting a ‘self-assessment’ against each of the program performance indicators and strategic performance measures. Defence advised that it makes the final approval of the self-assessment. If a company assesses its performance as ‘poor’, the company is able to provide reasons for this in their self-assessment. Defence has noted that:

… unlike a traditional performance arrangement in Defence, we are not holding the prime’s payment at risk against their achievement. The new Agreement also allows the prime to provide an explanation against each measure as to their performance rating for the quarter … Where Defence accepts this justification, an overall rating of Satisfactory can be applied to the prime’s efforts for that reporting period.48

4.23 Defence provided the following reasoning for this approach:

There is a multitude of factors influencing the prime’s achievement against each of the performance measures. These include the length of time the prime has been involved with the program, the global competiveness of the SME and the prime’s commercial drivers / capability focus. Technology related contracts can take up to three years to be awarded due to trials and testing whereas contracts for lower order work such as machining tend to be awarded within a six month timeframe.49

4.24 Defence informed the ANAO that where a prime’s performance is assessed as unsatisfactory, there are clauses in the agreement that allow for termination. Further, the quarterly reports process provides a framework for discussions between Defence and the primes, and remedial action may be taken if necessary.

4.25 The new performance measures and monitoring arrangements are an improvement on the previous arrangements. The improvements include the removal of subjective reporting, and links between performance and renewal of agreements with the primes. There is also an expectation that the primes will focus not only on the number and value of contracts, but also aim for contracts of longer duration, and aim to increase the SME base.

4.26 The new performance arrangements still rely on self-assessment by the primes, and where performance is assessed as ‘poor’, companies can provide reasons for this and their overall performance can still be rated by Defence as satisfactory. To reduce the risks associated with a self-assessment approach, Defence could directly approach a sample of SMEs awarded GSC contracts on a periodic basis to validate the self-reported performance of the primes, particularly in assessing how well the primes engage with SMEs in providing training and marketing assistance.

Defence industry stakeholders regard the program as beneficial but have identified opportunities for improvement

4.27 The Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade commenced an inquiry into opportunities to expand Australia’s defence industry exports in May 2014. The Committee sought input from stakeholders, particularly Defence Industry, as to how Government can better facilitate export of Australian defence products and services.

4.28 Many of the submissions to the inquiry commented on the GSC program. The boxed text outlines the comments from the submissions mentioning the program.50

|

Box 4: Summary of industry submissions referencing the GSC program |

|

Source: Submissions to the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Inquiry into Government Support for Australian Defence Industry Exports.

5. Rapid Prototyping, Development and Evaluation Program

Areas examined

This chapter examines the:

- management arrangements for the RPDE program; and

- performance of the program.

Conclusion

The Rapid Prototyping, Development and Evaluation (RPDE) program differs from other programs listed in the Defence Industry Policy Statement, in that it is a collaboration between Defence and industry to provide innovative solutions to Defence for urgent, high risk capability issues. The program has clear and well documented management, advisory and governance arrangements, but the ANAO’s analysis of a sample of RPDE program activities indicated that some key processes were not always followed.

Defence monitors program performance at an activity-level, but is not well positioned to assess program-level performance. The RPDE Board has reduced its role in monitoring the performance of the RPDE program, and a 2009 Board resolution makes no mention of the Board having a continuing role in monitoring performance.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that the new RPDE program Relationship Agreement and Standing Offer should clearly set out the roles of the Board, and that Board activities should in future be consistent with those roles.

Program overview

5.1 The Rapid Prototyping, Development and Evaluation (RPDE) program was established in February 2005 to accelerate and enhance Defence’s warfighting capability through innovation and collaboration in Network Centric Warfare.51 The RPDE program was announced by the then Minister for Defence as a new ‘Network Centric Warfare’ initiative that was designed to speed up the acquisition of emerging capabilities.52

5.2 The RPDE program has a different character to other Defence industry programs, which are intended to support and develop Australia’s defence industry. In contrast, the RPDE program focuses on innovation, and involves the collaboration of Defence, industry and academia to ‘resolve urgent, high risk capability issues [for Defence] for which a solution does not exist’ and that conventional acquisition processes might not be able to solve in a timely manner. The RPDE program also evaluates options to improve Defence’s warfighting capability in the near-term, with an emphasis on network-centric capability.

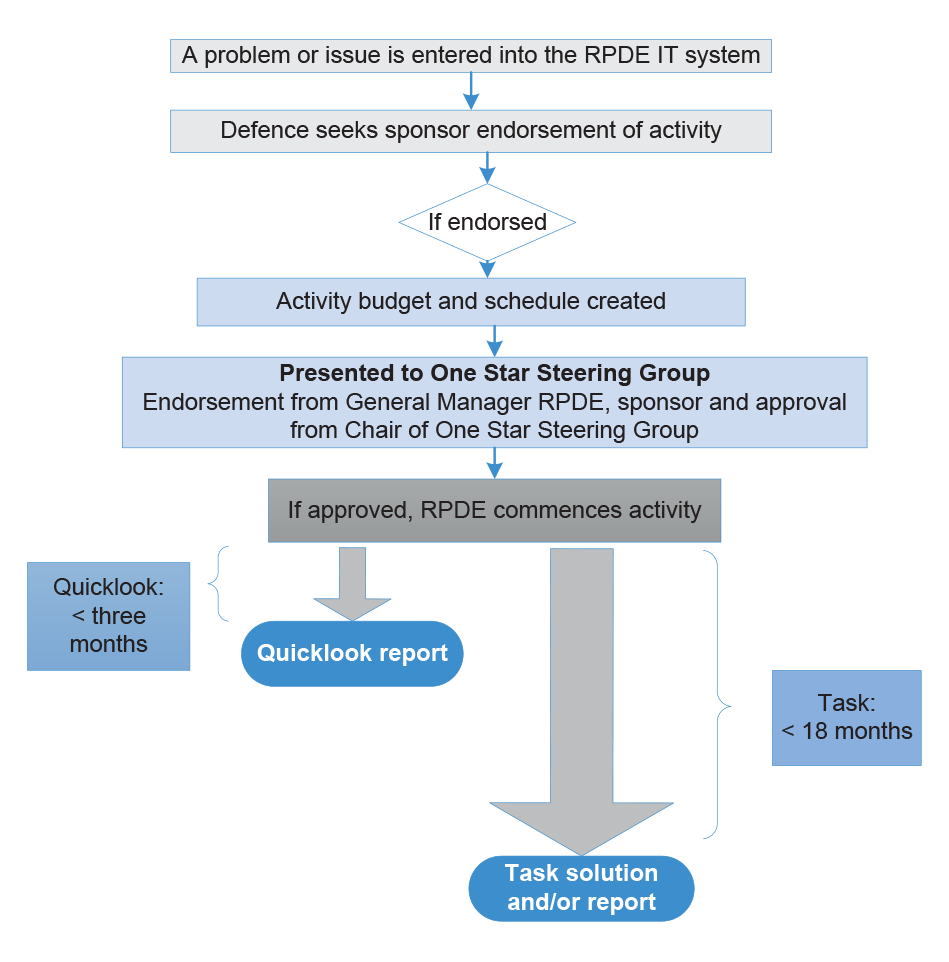

5.3 The RPDE program involves two main types of activities: Quicklooks and Tasks53 (see Table 5.1).

Table 5.1: RPDE program activities as at February 2015

|

Activity |

Time taken |

Description |

Number of activities |

Examples of activity |

|

Quicklook |

Three months or less |

Delivers guidance, advice and input on a Defence issue in the form of a report provided to the relevant Defence sponsor. |

112 |

Quicklook activities have related to the Defence Innovation Strategy, Support to future Navy electronic warfare systems and aspects of the Collins Class submarine |

|

Task |

18 months or less |

Delivers a solution to Defence. The solution may be a report, a proof of concept, or a physical prototype (limited to Technical Readiness Level 6a). The Task report focuses on all Fundamental Inputs to Capabilityb elements and on identifying, understanding and facilitating change. |

57 |

Tasks have related to improvised explosive device hand held detection, Explosive ordnance data logger and Defence’s e-health system. |

Note a: The Technical Readiness Level framework describes the technology maturity of systems and provides a standard method for conducting technical readiness assessments, and a standard language and definitions for technology readiness levels. Technical Readiness Level 6 is defined as a: ‘system/subsystem model or prototype demonstration in a relevant environment’.

Note b: The Fundamental Inputs to Capability comprise the following inputs: personnel; organisation; collective training; major systems; supplies; facilities and training areas; support and command and management.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documents.