Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Coordination Arrangements of Australian Government Entities Operating in Torres Strait

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the coordination arrangements of key Australian Government entities operating in Torres Strait.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Torres Strait is located between the tip of Cape York in northern Australia and Papua New Guinea (PNG). It contains over one hundred islands and reefs, 17 of which are inhabited. The population consists of approximately 4,500 people, over 90 per cent of whom are of Torres Strait Islander and/or Aboriginal background.

2. The region is characterised by the operation of the Torres Strait Treaty (the Treaty), which defines the border between Australia and PNG and provides a framework for the management of the common border area. The Treaty establishes a Protected Zone (delimited in green on the map in Figure S.1), the main purpose of which is to protect the traditional way of life of Torres Strait Islanders and the coastal peoples of PNG. Within the Protected Zone, Torres Strait Islanders and the inhabitants of 13 defined PNG villages are able to move freely (without passports or visas) for the purpose of conducting traditional activities.1 The Treaty also prescribes a set of principles to protect the fisheries and sea environment of Torres Strait, including that commercial fisheries should be administered in the Protected Zone so as not to prejudice traditional fishing.2

3. In 2017–18 traditional inhabitants from PNG made approximately 27,300 visits to the Protected Zone under the provisions of the Treaty. In comparison, the number of visits made by traditional inhabitants of the Protected Zone to PNG Treaty villages is significantly lower, with approximately 1,000 visits during the same period.

4. A large number of government entities operate in Torres Strait, at Australian, state and local government levels. At the Australian Government level, the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA), which is part of the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio, has responsibility for the development and implementation of programs aimed at supporting: economic development; health and wellbeing; culture; land and sea management; and native title rights of Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal peoples living in the region. Four other key Australian Government entities operate in Torres Strait:

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT): DFAT has overall responsibility for the Torres Strait Treaty.

- Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR): Through the Northern Australia Quarantine Strategy, DAWR conducts operations to address biosecurity risks associated with southward movements of people, cargo, aircraft and vessels.

- Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs), represented by the Australian Border Force (ABF): The ABF’s purpose in Torres Strait is to manage the movement of people across the border, including the flow of people throughout the Protected Zone in accordance with the free movement provisions of the Treaty.

- Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA): AFMA is responsible for the management and sustainable use of Commonwealth fish resources.

Figure S.1. Map of Torres Strait

Source: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. Australia recognises Torres Strait region as a sensitive and important zone because:

- the scattered islands represent stepping stones between PNG and Australia and is often referred to as ‘the closest thing Australia has to a land border’3. The close distance of PNG has immigration, customs and biosecurity implications;

- the region supports critical fisheries habitats and ecosystem resources; and

- the region is an international shipping route with difficult waters.

6. A 2010 Senate Inquiry into Torres Strait by the Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Reference Committee4 documented key issues associated with health, biosecurity, law and order and border protection, relating primarily to the shared border with PNG and the operation of the Treaty. The committee’s report stressed the importance of achieving effective whole-of-government cooperation and coordination between government entities. The audit examines the coordination arrangements of five Australian Government entities operating in Torres Strait.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit is to assess the effectiveness of the coordination arrangements of key Australian Government entities operating in Torres Strait. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high level criteria have been adopted:

- Do Australian Government entities operating in Torres Strait have appropriate governance arrangements to support the coordination of their activities?

- Are the coordination arrangements effective in supporting Australian Government activities in Torres Strait?

Conclusion

8. The coordination arrangements of key Australian Government entities operating in Torres Strait are largely effective in supporting Australian Government activities.

9. The business rules are effective for the implementation of biosecurity and fisheries legislation, and support the application of the Treaty provisions and the coordination of activities in Torres Strait. The business rules are not fully effective for the implementation of immigration and customs legislation in the context of the Treaty. This impacts on the capacity of entities to coordinate their activities and to develop a shared understanding of immigration and customs rules applicable in the region.

10. The governance structures and joint activities are largely effective to support cross-entity coordination. However, key policy decisions made by the Torres Strait Joint Advisory Council (JAC)5 are not adequately documented, and the risks associated with the impacts of a changing strategic and operational environment on the Treaty operation have not been analysed. The Protected Zone Joint Authority (PZJA)6 annual reports and website are not up-to-date.

11. The key systems and assets support the coordination of Australian Government entities’ operations in Torres Strait. An important project to improve telecommunications in Torres Strait is progressing.

Business rules

12. Immigration and customs business rules do not fully support the implementation of legislation and the coordination of activities in Torres Strait. There is insufficient guidance to implement the Treaty provisions, which has impacted on the consistency and lawfulness of some of immigration and customs decisions and has contributed to long-term immigration issues.

13. Biosecurity business rules are comprehensive and up-to-date, and support the implementation of the biosecurity legislation in Torres Strait.

14. The business rules, combined with the legislation, applying to fisheries in Torres Strait are comprehensive and fit-for-purpose, but some key governance documents are not up-to-date.

Governance Structures and Joint Activities

15. The governance structures provide an effective framework to support the operation of the Treaty, but could be improved by the establishment of a central register to record key decisions reached by the JAC. Also, issues relating to the changing strategic and operational environment represent a risk to the enduring operation of the Treaty.

16. Effective governance structures and joint activities support the control of cross-border movements and related law enforcement activities.

17. The governance structures and joint activities that support the management of biosecurity in Torres Strait are effective.

18. Through the PZJA, the consultative framework is largely effective to support and coordinate the decision making process of the range of entities involved in Torres Strait fisheries. Some of the actions agreed following the 2009 review of the PZJA’s administrative arrangements are still to be completed, and the PZJA’s annual reports and website are not up-to-date.

Systems and assets

19. Systems supporting the monitoring and recording of traditional inhabitant visits are fit for purpose. However there are some issues with: the data quality of the IT system used to record traditional inhabitants’ visits; and the controls applied to verify that traditional visits are conducted for the purpose for which they are authorised.

20. Robust arrangements are in place to optimise the use of vessels and aircraft across government entities operating in Torres Strait. Home Affairs could further engage with local stakeholders to assess and, as appropriate, address concerns that the ABF’s utilisation of assets is not always sufficiently timely or effective to respond to law enforcement issues of local relevance, in particular in the northern part of the Protected Zone.

21. The TSRA, in partnership with other entities including DAWR, is coordinating a project to improve telecommunications across the islands of Torres Strait.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.18

Noting the complexities in Torres Strait and the need for a degree of flexibility and discretion, the Department of Home Affairs develop comprehensive business rules to guide the implementation of immigration and customs legislation in Torres Strait and ensure consistent application of Treaty and legislative provisions.

Department of Home Affairs: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.12

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade establish and maintain a central register of policy decisions made by the Torres Strait Joint Advisory Council and ensure that the register is accessible to stakeholders, including Australian Government entities, operating in Torres Strait.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 3.16

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade conduct an analysis of the risks associated with the impacts of a changing strategic and operational environment on the enduring implementation of the Torres Strait Treaty.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade: Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 3.68

Australian Fisheries Management Authority work with the Protected Zone Joint Authority’s other member entities, the Torres Strait Regional Authority and Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, to:

- finalise the Protected Zone Joint Authority annual reports for the 2015–16, 2016–17 and 2017–18 financial years and implement a process to ensure that future annual reports are published in a timely manner; and

- keep the Authority’s website up-to-date.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

22. Summary responses from the entities are provided below. The full responses are provided at Appendix 1.

Department of Agriculture and Water Resources

The department welcomes the audit’s overall conclusions and findings.

The department is pleased the audit recognises that the business rules, governance structures and joint activities supporting biosecurity in Torres Strait are comprehensive, up-to-date and effective.

The department is also pleased the audit illustrates its strategic and collaborative approach to working with Australian Government entities and other agencies in Torres Strait and the Northern Peninsula Area (NPA). By way of update, the Exchange of Letters with the Australian Border Force has now been finalised by both parties and formalises current and future operational arrangements.

The department notes the audit’s recommendations and, while it is not directly responsible for any of the recommendations, will maintain awareness of initiatives to address the audit findings and will participate where appropriate.

The department remains committed to working in partnership with Australian Government entities, other agencies and communities in Torres Strait and NPA, to manage biosecurity risk and to support the ongoing implementation of the Torres Strait Treaty.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade [DFAT] welcomes the Australian National Audit Office [ANAO] findings that the governance structure and coordination arrangements of key Australian Government entities operating in the Torres Strait area are largely effective. The report’s acknowledgement of the complex and challenging environment in which agencies operate is also welcomed.

DFAT remains committed to ensuring the enduring integrity of the Torres Strait Treaty and the traditional way of life for Torres Strait Islanders and the coastal people of Papua New Guinea, which the Treaty protects. We are pleased that ANAO recognises DFAT’s efforts including: coordinating governance arrangements supporting the Treaty’s operation; Treaty Awareness Visits and joint multi-agency cross-border compliance activities; and extensive stakeholder engagement with traditional inhabitants.

We welcome the recommendations that support improvements in the Torres Strait area. The ANAO has noted some key areas requiring improvement, particularly in identifying risks associated with a changing strategic and operational environment on the implementation of Treaty arrangements and documenting key policy decisions made by the Torres Strait Treaty Joint Advisory Council. DFAT agrees to implement the relevant recommendations to strengthen the effectiveness of our cooperative arrangements and to ensure the relevance of the Treaty in a modern setting.

Department of Home Affairs

The Department of Home Affairs (the Department) and the Australian Border Force (ABF) acknowledge the value of the ANAO providing independent analysis of and insights into the coordination arrangements in the Torres Strait. We are pleased that the report found that the coordination arrangements in place optimise the use of vessels and aircraft for planned surveillance and intelligence activities, and that the governance structure and joint activities that support the management of biosecurity in the Torres Strait are effective.

The Torres Strait is a particularly unique and complex operating environment involving the collaboration of multiple Government entities, the operation of the Torres Strait Treaty aimed at protecting the traditional way of life of Torres Strait Islanders and the coastal peoples of PNG, and application of legislation including the Migration Act 1958. Operations are conducted and powers are exercised in the context of appropriately regulating the jurisdiction sympathetic to the normal activities and traditions of the indigenous people.

The Department and the ABF note the findings, conclusions and the recommendation made in the report. We agree with the recommendation regarding the need for comprehensive business rules to guide the implementation of immigration and customs legislation in the Torres Strait, which should have regard as the report notes, to the complexities of operating in the Torres Strait and the need for a degree of flexibility and discretion in applying legislative and Treaty provisions. The Department agrees that good governance is essential in any operating environment and is actively addressing relevant policies and procedural instructions to guide the implementation of immigration and customs legislation in Torres Strait, and the consistent application of the relevant Treaty and legislation.

On 10 May 2019, the Department finalised a Policy Statement relating to allowed inhabitants of the Protected Zone. This Statement broadly satisfies the recommendation and will facilitate the ABF to enhance Procedural Instructions and Standard Operating Procedures to provide further guidance around the exercise of discretionary detention powers. A Procedural Instruction for detaining an unlawful non-citizen in an excised offshore place and a Standard Operating Procedure providing further guidance border monitoring officers on the importation of goods used in connection with traditional activities, have been reviewed and are currently in the final stages of drafting. We expect to finalise these two documents soon. Further, on 18 April 2019, the ABF and the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR) signed a Letter of Exchange which articulates roles, responsibilities and work instructions, and reflects the amendments to the Biosecurity Act 2015.

In relation to the suggested areas of improvement, we note that IT connectivity in the Torres Strait will continue to impact operations in the region until it is more generally improved in the region and the ABF will continue to assist with local law enforcement matters based on a holistic consideration and prioritisation of threat and risk to the Australian border. The ABF has a standing Concept of Operations and command, control and coordination (C3) doctrine to deliver operational effect and outcomes. Under this operating model the Australian Border Operations Centre as the centralised and unified operations centre plays a critical role in the provision of a single source of truth or situational awareness to ensure decision making on the acceptance of tasks and any redirection or allocation of resources and capability is undertaken based on a holistic consideration and prioritisation of threat and risk to the Australian border.

Australian Fisheries Management Authority

AFMA has extensive responsibilities in managing Commonwealth fisheries resources in the Torres Strait and works to deliver on these in cooperation with a number of Commonwealth and other agencies.

AFMA has considered the proposed audit report and accepts that timely finalisation of Protected Zone Joint Authority annual reports and regular updating of the Authority’s website will enable stakeholders to be better informed about fisheries management issues and actions. Together with other PZJA member agencies, AFMA will also continue to work towards further integration and coordination of fisheries in the Torres Strait.

Torres Strait Regional Authority

The Torres Strait Regional Authority provided a letter of response to the audit. The letter is provided at Appendix 1.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

23. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Torres Strait

1.1 Torres Strait is located between the tip of Cape York in northern Australia and Papua New Guinea (PNG) (Figure 1.1). It contains over one hundred islands and reefs, 17 of which are inhabited. The population consists of approximately 4,500 people, over 90 per cent of whom are of Torres Strait Islander and/or Aboriginal background. Thursday Island, with approximately 3,000 inhabitants, is the administrative centre of Torres Strait. The key sources of employment in the region are public administration, health care and education services; commercial fishing also plays an important role in the local economy.

Figure 1.1: Map of Torres Strait

Source: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources.

1.2 Torres Strait is characterised by its close proximity to PNG. Western Province, the largest province in PNG, is about four kilometres, or ten minutes by boat, from the Australian islands closest to PNG (Saibai, Boigu and Dauan). In 2017, PNG had a population of approximately 8.3 million and a gross domestic product per capita of US$2,401 (Australia’s gross domestic product per capita was US$56,692). Eighty per cent of Papua New Guineans reside in traditional rural communities, relying on subsistence farming and small-scale cash cropping.

The Torres Strait Treaty

1.3 The region is also characterised by the operation of the Torres Strait Treaty (the Treaty). The Treaty and associated documents, signed in 1978 and coming into effect in 1985, define the border between Australia and PNG and provide a framework for the management of the common border area. The Treaty establishes a Protected Zone (delimited in green on the map in Figure 1.1), the main purpose of which is to protect the traditional way of life of Torres Strait Islanders and the coastal peoples of PNG.

1.4 The Treaty also prescribes a set of principles to protect the fisheries and sea environment of Torres Strait. It establishes the principle that commercial fisheries should be administered in the Protected Zone so as not to prejudice traditional fishing.7

1.5 Within the Protected Zone, inhabitants of the Torres Strait Islands and of 13 defined PNG villages are able to move freely (without passports or visas) for the purpose of conducting traditional activities. Traditional activities are defined in the Treaty as ‘activities performed by the traditional inhabitants in accordance with local tradition’, and include gardening, collection of food, hunting, traditional fishing, religious and secular ceremonies or gatherings for social purposes (for example, marriage celebrations and settlement of disputes), and barter and market trade.8 The Treaty villages are shown on Figure 1.2.

1.6 In 2017–18 traditional inhabitants from PNG made approximately 27,300 visits to the Protected Zone under the provisions of the Treaty.9 Approximately 98 per cent of these visits were to the Islands of Saibai, Boigu or Dauan, and the main declared purpose for visiting was ‘barter and trade’ (approximately 85 per cent of visits in 2017–18). The Treaty does not provide for commercial activities, seeking health or medical treatment, business dealings and working for money during traditional visits. However, selling goods and traditional artefacts to other traditional inhabitants for money is permitted. These trading activities primarily take place at markets organised weekly on set days on Saibai, Boigu or Dauan.

1.7 In comparison, the number of visits made by Torres Strait Islanders living in the Protected Zone to PNG Treaty villages is significantly lower, with approximately 1,000 visits during the same period.

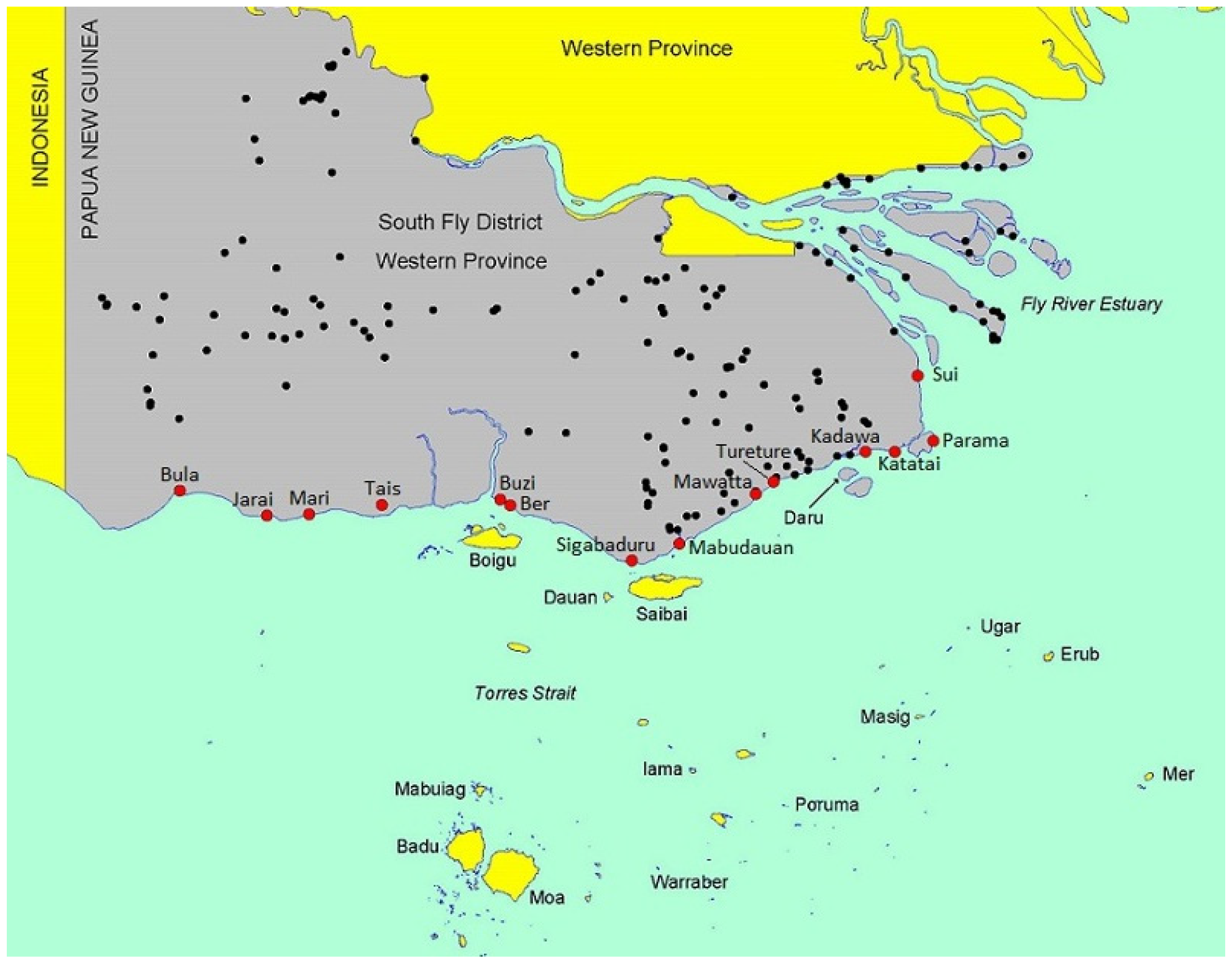

Figure 1.2: Map of the Torres Strait Islands and PNG villages covered by the Torres Strait Treaty Provisions

Note: The red dots represent PNG villages included in the Treaty. The black dots represent other PNG villages in South Fly District.

The PNG villages of Buzi and Ber are treated as one village under the Treaty provisions.

Source: Map courtesy of Dr Garrick Hitchcock, The Australian National University.

Australian Government entities operating in Torres Strait

1.8 A large number of government entities operate in Torres Strait, at local, state and federal government levels. The three local councils are: the Torres Strait Island Regional Council, which covers all the land and sea territory included in the Protected Zone (plus Hammond Island, which is outside the Protected Zone); the Torres Shire Council, which represents Thursday Island, Prince of Wales Island, Horn Island and immediate surrounding islands; and the Northern Peninsula Area Regional Council, which represents five communities situated on the northern part of Cape York on the Australian mainland.

1.9 At the Australian Government level, the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA) ), which is part of the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio, has responsibility for the development and implementation of programs aimed at supporting: economic development; health and wellbeing; culture; land and sea management; and native title rights of Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal peoples living in the region. As at 30 June 2018 the TSRA employed 162 staff, of whom 122 are Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal people. In 2017–18 the TSRA received $53.3 million from a range of Australian Government agencies, including $36 million in appropriation from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

1.10 Four other key Australian Government entities operate in Torres Strait.

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT): DFAT has overall responsibility for the implementation of the Torres Strait Treaty. It has established a Liaison Office on Thursday Island, staffed as at 28 February 2019 by two officers at the Executive Level 1 and Australian Public Service Level 5. The role of the Treaty Liaison Officer is prescribed in the Treaty and aims to facilitate the practical operation of the Treaty provisions, including through the implementation of local arrangements developed in consultation with representatives of traditional inhabitants. Their role is also to escalate nationally any issue that cannot be resolved at the local level.

- Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR): Through the Northern Australia Quarantine Strategy,10 DAWR conducts operations to address biosecurity risks associated with southward movements of people, cargo, aircraft and vessels into and between defined biosecurity zones in Torres Strait (which encompass the Protected Zone), and from these zones to mainland Australia. As at 28 February 2019, DAWR employed 27 staff across Torres Strait and the Northern Peninsula Area, all of whom were locally engaged and identified as being from Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander backgrounds, and 13 of whom were based on the islands of the Protected Zone.

- Department of Home Affairs, represented by the Australian Border Force (ABF): The ABF is Australia’s frontline border law enforcement agency and Australia’s customs service. Its purpose in Torres Strait is to protect Australia’s border and enable legitimate travel and trade, including the flow of people throughout the Protected Zone in accordance with the free movement provisions of the Treaty. The ABF office located on Thursday Island comprised, as at 28 February 2019, 13 funded positions (four vacant). The highest ranking officer is an inspector (Executive Level 1). In addition, the ABF has ten funded positions (one vacant) for Border Monitoring Officers. Border Monitoring Officers are locally engaged officers employed to monitor and record the movements of traditional inhabitants across the border, including refusing immigration clearance to people not meeting the provisions of the Treaty. Border Monitoring Officers are employed at the Australian Public Service Levels 1 and 2.

- Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA): AFMA is responsible for the management and sustainable use of Commonwealth fish resources. To discharge its responsibilities in Torres Strait, AFMA employed 12 staff as at 28 February 2019, which included nine officers in fisheries management and three in compliance. Of these 12 officers, eight officers are based on Thursday Island, and four officers are based in Canberra.

1.11 Other Australian Government entities operating in Torres Strait include the following.

- Australian Federal Police (AFP): The AFP carries out an intelligence function in Torres Strait, and has two permanent officers based on Thursday Island.

- Australian Defence Force: The 51st Battalion, Far North Queensland Regiment, primarily carries out reconnaissance and surveillance tasks in support of border security operations. One of the Battalion’s companies is headquartered on Thursday Island. Approximately 30 per cent of the 51st Battalion is reported by the Department of Defence as being from Torres Strait Islander and mainland Aboriginal backgrounds.

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA): AMSA aims to improve and promote boat safety in Torres Strait and reduce the number of search and rescue operations in the area. As at March 2019, AMSA has two employees servicing Torres Strait and the Northern Peninsula Area, both based on Thursday Island.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.12 Australia recognises the Torres Strait region as a sensitive and important zone because:

- the scattered islands represent stepping stones between PNG and Australia and is often referred to as ‘the closest thing Australia has to a land border’.11 The close distance of PNG has immigration, customs and biosecurity implications;

- the region supports critical fisheries habitats and ecosystem resources; and

- the region is an international shipping route with difficult waters.

1.13 A 2010 Senate Inquiry into Torres Strait by the Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Reference Committee12 documented key issues associated with health, biosecurity, law and order and border protection, relating primarily to the shared border with PNG and the operation of the Torres Strait Treaty. The committee’s report stressed the importance of achieving effective whole-of-government cooperation and coordination between government entities. The audit examines the coordination arrangements of five Australian Government entities operating in Torres Strait.

Audit objective and criteria

1.14 The objective of the audit is to assess the effectiveness of the coordination arrangements of key Australian Government entities operating in Torres Strait. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high level criteria have been adopted:

- Do Australian Government entities operating in Torres Strait have appropriate governance arrangements to support the coordination of their activities?

- Are the coordination arrangements effective in supporting Australian Government activities in Torres Strait?

1.15 The report examines:

- the business rules (such as procedures and guidance) that Australian Government entities use to deliver their functions in accordance with their legislation and the provisions of the Torres Strait Treaty (Chapter 2);

- the governance structures and joint activities that Australian Government entities have established to support the coordination of their activities, and the activities that they are conducting jointly (Chapter 3); and

- the systems and assets (permits and IT systems monitoring cross-border movements, arrangements to deploy and share vessels and aircraft, and telecommunications) that support the coordination of Australian Government entities’ operations in Torres Strait (Chapter 4).

Audit methodology

1.16 The audit methodology included the following.

- Fieldwork in Torres Strait and the Northern Peninsula Area, and some PNG Treaty villages adjacent to Torres Strait. Fieldwork included observing activities conducted by individual entities and those conducted jointly by multiple entities.

- Review of relevant departmental documents.

- Interviews and meetings with representatives of the Australian Government, Queensland Government and local Councils on Thursday Island, in Cairns and in Canberra.

- Interviews with, and submissions from, community members and organisations based or operating in Torres Strait.

1.17 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $450,000.

1.18 The team members for the audit were Dr Isabelle Favre, Hugh Balgarnie, Yvonne Buresch and Deborah Jackson.

2. Business rules

Areas examined

This chapter examines the business rules that Australian Government entities use to deliver their functions in accordance with their legislation and the provisions of the Torres Strait Treaty (the Treaty) relating to immigration and customs, biosecurity and fisheries. The chapter also assesses whether these business rules are effective in supporting the coordination of activities in Torres Strait.

Conclusion

The business rules are effective for the implementation of biosecurity and fisheries legislation, and support the application of the Treaty provisions and the coordination of activities in Torres Strait. The business rules are not fully effective for the implementation of immigration and customs legislation in the context of the Treaty. This impacts on the capacity of entities to coordinate their activities and to develop a shared understanding of immigration and customs rules applicable in the region.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving immigration and customs business rules.

2.1 The Treaty prescribes a set of rules and principles that provides a framework for the management of the common border area between Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Australia. With the establishment of the Protected Zone, the requirements and procedures that normally apply at other Australian borders to deal with immigration, customs, biosecurity and fisheries, are interpreted or adapted to comply with the provisions of the Treaty.

2.2 A set of business rules (such as procedures and guidance) consistent with the provisions prescribed in the Treaty is instrumental for entities to operate effectively and lawfully in Torres Strait, and to support the coordination of their activities with other entities. Given the different rules in place in the Protected Zone, it is important that officers operating in Torres Strait are provided with practical guidance on how to exercise their functions, relative to Treaty provisions.

2.3 Box 1 outlines the key provisions prescribed in the Treaty in relation to immigration, customs, biosecurity and fisheries.

|

Box 1: Torres Strait Treaty’s provisions on immigration, customs, biosecurity and fisheries |

|

Immigration, customs and biosecurity The provisions to be applied for immigration, customs and biosecurity are briefly described in Article 16 of the Treaty. The article establishes that, as a principle:

The article also prescribes that:

Fisheries The Treaty is considerably more detailed in relation to the management of fisheries in the Protected Zone, to which it dedicates nine articles (Articles 20 to 28). In particular, it establishes the principle that commercial fisheries should be administered in the Protected Zone so as not to prejudice traditional fishing. The Treaty also:

In the case of a suspected offence committed in or in the vicinity of the Protected Zone in the course of traditional fishing, corrective actions should be taken by the country of which the alleged offender is a citizen and, if detained, the alleged offender and their vessel should be released or handed over to the authorities of their country of origin (Article 28). |

Do immigration and customs business rules support the implementation of legislation and coordination of activities?

Immigration and customs business rules do not fully support the implementation of legislation and the coordination of activities in Torres Strait. There is insufficient guidance to implement the Treaty provisions, which has impacted on the consistency and lawfulness of some of immigration and customs decisions and has contributed to long-term immigration issues.

2.4 Home Affairs is responsible for administering migration and customs legislation, including in Torres Strait.

Immigration legislation

2.5 In reference to the Treaty, the Migration Act 1958 establishes three key points:

- PNG traditional inhabitants who are in the Protected Zone to perform traditional activities do not need to travel with a passport or a visa and are referred to as lawful non-citizens;

- an officer ‘may’ detain a person in the Protected Area if the officer ‘knows or reasonably suspects’ that the person is a PNG citizen and an unlawful non-citizen (Migration Act subsection 189(3A)); and

- PNG traditional visitors may have their right to enter Australia (including the Protected Zone) removed by the responsible Minister (Migration Act section 16).

2.6 Subsection 189(3A) of the Act was introduced as part of the Migration Legislation Amendment (Offshore Processing and Other Measures) Act 2012 to allow for the discretionary detention of a PNG citizen found to be an unlawful non-citizen in the Protected Zone, whether that person is a traditional visitor (that is, from one of the Treaty Villages) or not. Elsewhere in Australia, subsection 189(1) prescribes that ‘if an officer knows or reasonably suspects that a person in the migration zone … is an unlawful non-citizen, the officer must detain the person’.

2.7 The Migration Act refers to the Torres Strait Treaty for the definition of traditional activities, and to the Torres Strait Fisheries Act 1984 for the definition of traditional inhabitant.13 The Migration Reform Act 1994 further specifies that an ‘allowed’ PNG traditional inhabitant must not be a ‘behaviour concern’ or ‘health concern’.

Immigration business rules

2.8 Home Affairs’ database for policies, procedures, delegations and authorisations (the Policy and Procedure Control Register) contains two instructions of relevance to the implementation of the Torres Strait Treaty:

- Instruction TT-2987 Allowed inhabitants of the Protected Zone was last updated in November 2013. The instruction defines the key terms and provisions of the Treaty and provides some information on the role of the department in the Protected Zone and on the migration status and clearance process for allowed and non-allowed visitors. It provides detailed guidance on how to use a ban under section 16 of the Migration Act (section 16 ban), indicating that the decision to issue a section 16 ban should be made with great care given the impact on the rights of the traditional visitors, and in consultation with local, state and federal government representatives.

- Procedural Instruction BC-536 Arrival, immigration clearance and entry – Immigration Clearance at airports and seaports (September 2018) specifies that if a traditional visitor is in the Protected Zone for activities other than traditional, they become unlawful non-citizens. In line with Migration Regulation 1994, the instruction prescribes that traditional visitors leaving the Protected Zone must comply within five days with immigration clearance requirements (including holding a visa and identity documents) at a departmental office or at any place where there is a clearance officer. The instruction takes into consideration the fact that traditional visitors may leave the Protected Zone inadvertently and should also be given the option to return to the Protected Zone immediately.

Implications for immigration decisions

2.9 In summary:

- a PNG citizen in the Protected Zone who conducts any non-traditional activities becomes an unlawful non-citizen who may be detained. For example, a PNG traditional inhabitant who visits the Protected Zone to work for money (such as doing some gardening or fishing for an Australian operator) or to sell goods to non-traditional inhabitants; or who, during a traditional visit, commits a criminal offence; becomes an unlawful non-citizen who may be detained; and

- a PNG citizen outside the Protected Zone becomes an unlawful non-citizen who must be detained (or given the option to apply for a visa or return to the Protected Zone). For example, a PNG traditional inhabitant whose boat inadvertently lands on an island outside the Protected Zone because of poor weather, must be detained unless they obtain a visa and identity documents within five days or agree to return to the Protected Zone immediately.

2.10 The two instructions available to ABF officers (see paragraph 2.8) do not provide any guidance on how to implement the discretionary power (‘may be detained’) to detain a PNG citizen found to be an unlawful non-citizen in the Protected Zone. Apart from limited situations (which include, since late 2018, PNG citizens accessing health care in the Protected Zone and the Australian mainland — see Case Study 1 below), there is also insufficient guidance about how to resolve situations where PNG citizens find themselves outside the Protected Zone and cannot be practically detained14, and the options that can be used as an alternative to detention.

2.11 The two case studies below illustrate the range of complex situations that can arise from the operation of the Treaty and the difficulties generated by an inconsistent interpretation of the migration legislation.

|

Case study 1. PNG health visitors in the Protected Zone and the Australian mainland |

|

While seeking health care is not a traditional activity under the Treaty, Queensland Health provides health services to PNG nationals who travel to Torres Strait and require health treatment.a Emergency treatment is provided at local clinics and non-emergency presentations are referred back to clinicians in PNG for ongoing care. If patients require emergency inpatient care they may be transported to other Queensland Health facilities, generally on Thursday Island but sometimes on the mainland, or referred to the PNG health system, depending on the severity of presentation. Queensland Health estimates that every year, approximately 100 PNG patients are admitted to Thursday Island and other hospitals on the mainland, and 2000 PNG out-patients visit health care facilities of Torres Strait (inside and outside of the Protected Zone). The immigration status and treatment of PNG citizens transferred to a health care facility inside and outside the Protected Zone has been inconsistent over the years. Inside the Protected Zone, the department’s instructions to Border Monitoring Officers assessing PNG health visitors and their escorts have been to record them as ‘refused immigration clearance’ and, as much as practicable, accompany them to and from the health clinic. This enables the department to act consistently and lawfully. However, when PNG citizens are medically transferred to a health care facility outside the Protected Zone, they are not covered by the Treaty provisions and become unlawful non-citizens who, by law (subsection 189(1)), must be detained. The department has not applied a consistent policy to address these situations. Until March 2018, departmental documents indicate that PNG patients transferred to Thursday Island or mainland Australia were in most cases not detained. From March 2018, the department commenced detaining PNG patients and their escorts on the mainland (mostly Brisbane, Cairns or Townsville), but not patients and escorts transferred to Thursday Island. In December 2018 the ABF developed an interim standard operating procedureb to clarify the immigration status of PNG citizens transferred to a health care facility outside the Protected Zone. The procedure states that PNG patients and their escorts are not to be detained within health care facilities in the Protected Zone and Thursday Island hospital, but they must be detained if they arrive on the Australian mainland (including Brisbane, Cairns or Townsville). The Migration Act prescribes that unlawful non-citizens must be detained when outside the Protected Zone, including on Thursday Island, if an officer has a reasonable suspicion that the person is an unlawful non-citizen (subsection 189(1)). In May 2019, Home Affairs advised that the decision to detain a PNG national in Torres Strait can be complicated, particularly where the person has no travel document or is unclear about their parentage/heritage. Home Affairs also advised that it is working on options to regularise the status of PNG nationals who travel outside the Protected Zone (for instance, Thursday Island or the Australian mainland) for medical treatment through the grant of an appropriate visa. The procedure also prescribes that patients and their escorts must be returned to the Protected Zone where they are not to be detained, but are to be accompanied to the waterfront where their departure can be monitored by ABF officers. |

Note a: An agreement between the Commonwealth Department of Health and Queensland Health provides funding to Queensland Health to support the delivery of healthcare and disease prevention projects in the Torres Strait Islands. Under the current agreement, the Commonwealth is providing an estimated total financial contribution to Queensland of $26.5 million over four years (2016–17 to 2019–20). Three projects are funded: Management of cross-border health issues, including treatment of PNG visitors ($19m); Testing, treatment and prevention of blood-borne viruses and sexually transmissible infections ($4.5m); and Mosquito control and cross-border liaison in regard to communicable diseases and other health issues ($3m).

Note b: Australian Border Force, Interim process for the arrival, detention and return of PNG nationals originating from the Torres Strait in Australia for medical Treatment, December 2018.

|

Case study 2. Migration status of children residing in Australia through the process of customary adoptions |

|

In some areas of Torres Strait, a number of Australians are raising children of PNG citizens (that is, parents who are not Australian citizens or Australian visa holders), based on family linkages within the region. These customary adoptions are not formalised in PNG or recognised by the Australian Government. Additionally, a number of children born in Australia to PNG citizens reside in Torres Strait. As children do not automatically acquire Australian citizenship or an Australian visa when they are born in or brought to Australia, these children do not have a lawful migration status in Australia. Two Home Affairs internal information reports dated January 2018 indicate that ‘several hundred’ PNG minors are living in Torres Strait, based on an arrangement between PNG parents and Australian hosts to care for the children. Another internal report, dated December 2017, indicates that ‘thousands’ of PNG citizens are living in Torres Strait and mainland Australia without a visa as a result of either customary adoption practices or being born in Australia by PNG parents. Customary adoptions among Torres Strait Islander peoples are a long-standing practicea that has extended to children from PNG in the Protected Zone. Until 2016 Home Affairs had not addressed the migration issues related to customary adoptions. In 2016 a decision was made to require that Australian carers register PNG minors by 31 March 2017 so the department could consider whether these minors are eligible for Australian citizenship or a visa. Past this date, customary adoptions would have to be undertaken through normal migration channels. However, the department has not addressed the situation of adult children living in Australia.b |

Note a: In October 2018 the Queensland Government announced its intention to develop new legislation that officially recognises Torres Strait People’s ‘ancient and enduring cultural’ child rearing practices. Queensland Government, ‘Torres Strait child rearing practices to be enshrined in law’, media release, 12 October 2018, Available from http://statements.qld.gov.au/Statement/2018/10/12/torres-strait-child-rearing-practices-to-be-enshrined-in-law [accessed 4 March 2019].

Note b: Home Affairs advised that the measures established to resolve the status of PNG children residing in Torres Strait could apply to individuals aged up to 24 years (noting that individuals over 18 years were required to meet additional dependency criteria).

2.12 Having insufficient business rules about how to manage the situations arising from the Treaty provisions increases the risk that the Home Affairs’ officers will act inconsistently, inappropriately or unlawfully.15 This can lead to the creation of long-term immigration issues (as demonstrated by the legacy of the department’s historical management of customary adoptions documented in Case Study 2). It can also adversely impact on: communities’ expectations and perceptions of ABF’s role; and other government entities’ capacity to coordinate their activities with the ABF and fully understand ABF’s role and responsibilities.

Customs legislation

2.13 The Customs Act 1901 includes one section that refers to the Treaty, section 30A, which establishes that certain ships and goods may be exempt from some of the provisions of the Customs Act, as long as these ships or goods are associated with traditional inhabitants and traditional activities in the Protected Zone.16 Ships are defined as having on board ‘at least one traditional inhabitant who is undertaking that voyage in connection with the performance of traditional activities in the Protected Zone’. Goods are defined as being goods that are ‘owned by, or under the control of, a traditional inhabitant who is on board that ship and … used by him or her in connection with the performance of traditional activities in the Protected Zone’.

2.14 The provisions of the Customs Act from which ships and goods may be exempt are to be published in the Gazette. Two Notices of Exemption were published in the Gazette in July 1986, listing the different sections of the Customs Act from which traditional inhabitants’ ships and goods were exempted. On 7 March 2019, the two Notices were revoked and a new Notice of Exemption, reflecting the amendments to the Customs Act since 1986, was gazetted.

Customs business rules

2.15 While the definition of traditional inhabitants and traditional activities are established in other legislation and guidance documents17, the concept of goods used in connection with traditional activities from a customs perspective has not been defined18. For instance, PNG traditional inhabitants invited to a wedding in the Protected Zone may want to bring alcohol or tobacco ‘in connection with the performance of traditional activities’ (Customs Act subsection 30A(3)). The Customs Act and associated prohibited import regulations would apply to these goods. However, Border Monitoring Officers have not been provided with guidance on how to recognise and authorise the importation of goods used in connection with traditional activities.19

2.16 Home Affairs’ Policy and Procedure Control Register does not include any guidance related to the application of customs legislation in Torres Strait. Home Affairs advised on 25 March 2019 that ABF officers based in Torres Strait District Command on Thursday Island provide advice or instruction to Border Monitoring Officers over the phone. Nevertheless, providing written guidance on the implementation of customs legislation in the context of the Protected Zone will assist ABF officers, including Border Monitoring Officers, to make decisions that are consistent with legislation and the Treaty. Consistent implementation of customs decisions also contributes to more effective coordination of entities activities as it facilitates a shared understanding of the rules applicable in the Protected Zone.

2.17 On 28 March 2019, Home Affairs advised that the Department and the ABF are working towards developing updated and additional guidance for officers working in Torres Strait. Home Affairs also noted that whilst good governance is essential in any operating environment, the particular complexities in Torres Strait, including the interaction of Treaty and legislative provisions, require a degree of flexibility and discretion.

Recommendation no.1

2.18 Noting the complexities in Torres Strait and the need for a degree of flexibility and discretion, the Department of Home Affairs develop comprehensive business rules to guide the implementation of immigration and customs legislation in Torres Strait and ensure consistent application of Treaty and legislative provisions.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.19 The Department agrees with this recommendation noting the need for comprehensive business rules to guide the implementation of immigration and customs legislation in the Torres Strait, which should have regard as the report notes, to the complexities of operating in the Torres Strait and the need for a degree of flexibility and discretion in applying legislative and Treaty provisions. The Department agrees that good governance is essential in any operating environment and is actively addressing relevant policies and procedural instructions to guide the implementation of immigration and customs legislation in Torres Strait, and the consistent application of the relevant Treaty and legislation.

2.20 On 10 May 2019 the Department finalised a Policy Statement relating to allowed inhabitants of the Protected Zone. This Statement broadly satisfies the recommendation and will facilitate the ABF to enhance Procedural Instructions and Standard Operating Procedures to provide further guidance around the exercise of discretionary detention powers. A Procedural Instruction for detaining an unlawful non-citizen in an excised offshore place and a Standard Operating Procedure providing further guidance border monitoring officers on the importation of goods used in connection with traditional activities, have been reviewed and are currently in the final stages of drafting. We expect to finalise these two documents soon.

2.21 Further, on 18 April 2019, the ABF and the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR) signed a Letter of Exchange which articulates roles, responsibilities and work instructions, and reflects the amendments to the Biosecurity Act 2015. The ABF and DAWR have a long productive working relationship in this unique operating environment that relies on cooperation to provide border security and deliver services to the Commonwealth, including the administration of immigration, customs and biosecurity regulations. A copy of this Letter of Exchange has been provided to the ANAO.

Do biosecurity business rules support the implementation of legislation and coordination of activities?

Biosecurity business rules are comprehensive and up-to-date, and support the implementation of the biosecurity legislation in Torres Strait.

2.22 The Biosecurity Act 2015 provides the legislative framework relating to diseases and pests that may affect human, animal and/or plant health. The framework is administered jointly by the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (DAWR) and the Department of Health.20

Biosecurity legislation

2.23 Section 617 of the Biosecurity Act relates to the Treaty and allows regulations to be made in order to implement the Treaty, by exempting Protected Zone vessels (and persons and goods on board these vessels) from all or any provisions of the Act while in the Protected Zone.21 Goods may be exempt from the provisions of the Biosecurity Act if they are:

- owned by, or are under the control of, a traditional inhabitant who is on board that vessel and have been used, are being used or are intended to be used by him or her in connection with the performance of traditional activities in a Protected Zone area; or

- the personal belongings of a traditional inhabitant.

2.24 Several instruments of the biosecurity legislation further define the provisions of the Biosecurity Act from which Protected Zone vessels are exempt.22 This includes section 49 of the Biosecurity (Prohibited and Conditionally Non-prohibited Goods) Determination 2016, which defines the classes of goods that can be brought into the Protected Zone. These exemptions aim to enable free movement of traditional inhabitants and the performance of lawful traditional activities within the Protected Zone, in line with the Treaty provisions.

2.25 The Biosecurity Regulation 2016 also determines the Torres Strait Permanent Biosecurity Monitoring Zone, which includes the area south of the Protected Zone to mainland Australia (Figure 2.1). Permanent Biosecurity Monitoring Zones are established in places that are assessed as presenting a higher biosecurity risk. They are used to:

… monitor whether pests or diseases that may pose an unacceptable level of biosecurity risk have entered, or are likely to enter, emerge, establish or spread from places that are known to be subject to high traffic of goods or conveyances that are subject to biosecurity control.23

2.26 The Biosecurity Act outlines the powers that may be exercised in the zone to manage this elevated risk, as well as civil penalty provisions.

Figure 2.1: Torres Strait Biosecurity Zones

Source: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources.

2.27 By determining a Permanent Biosecurity Monitoring Zone between the Protected Zone and the mainland which, in practice, acts as a ‘buffer zone’, DAWR has recognised the heightened risk posed by movements allowable under the Treaty.

Biosecurity business rules

2.28 DAWR has developed a range of business rules to assist biosecurity officers operating in the Protected Zone. These include work instructions on:

- the clearance of traditional vessels;

- the inspection of goods transported between the Protected Zone to the Permanent Biosecurity Monitoring Zone or from either of these zones to the mainland; and the delivery of permits for goods that require them;

- the assessment and management of aircrafts and larger vessels departing from Torres Strait; and

- the interim procedures for ABF Border Monitoring Officers to follow when conducting biosecurity inspections of PNG traditional visitors.

2.29 DAWR has also developed a reference guide outlining the conditions to be applied to the movement of goods from PNG treaty villages to the Protected Zone or the Permanent Biosecurity Monitoring Zone and from the zones to the mainland. The guide includes, for each good, a description and photograph.

2.30 The rules provide detailed instructions and guidance on how to implement the elements of the biosecurity legislation that are relevant to the application of the Treaty provisions. All the documents were updated to reflect the changes introduced by the Biosecurity Act 2015. All the documents include evidence of amendments and a version history. All but one, the work instruction Clearance of Torres Strait traditional vessels, notes the date of the next review. DAWR advised that this work instruction should be reviewed at least every three years in accordance with its internal policy.

Do fisheries business rules support the implementation of legislation and coordination of activities?

The business rules, combined with the legislation, applying to fisheries in Torres Strait are comprehensive and fit-for-purpose, but some key governance documents are not up-to-date.

2.31 The management of commercial and traditional fishing in the Protected Zone is governed by the provisions of the Treaty which, as previously noted (Box 1, page 23), dedicates nine of its 32 articles to issues related to fisheries.

Fisheries legislation

2.32 The Torres Strait Fisheries Act 1984 came into force in February 1985, shortly after the Treaty. The purpose of the Torres Strait Fisheries Act is to give effect, in Australian law, to the fisheries elements of the Treaty. In particular, the Act prescribes as management priorities:

- the acknowledgment and protection of the traditional way of life and livelihood of traditional inhabitants;

- the protection and preservation of the marine environment and indigenous fauna and flora (in such a way as to minimise any restrictive effects of the measures on traditional fishing);

- the management of commercial fisheries for optimum utilisation, but so as not to prejudice the provisions of the Treaty in regard to traditional fishing;

- the sharing of the commercial fish harvest with PNG in accordance with the Treaty; and

- the promotion of economic development in the Torres Strait area and employment opportunities for traditional inhabitants.

2.33 The Torres Strait Protected Zone Joint Authority (PZJA) is established by Part V of the Torres Strait Fisheries Act. The PZJA comprises the Commonwealth minister responsible for fisheries, the chair of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA) and the Queensland minister responsible for Fisheries. Its key functions are to ‘[keep] constantly under consideration the condition of the fishery; formulate polices and plans for the good management of the fishery’, while ‘cooperating and consulting with other authorities’.

2.34 The PZJA is responsible for the administration of the Torres Strait Fisheries Act. Its members are supported by the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA), DAWR, the TSRA and Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (Queensland Fisheries). Currently AFMA and Queensland Fisheries have the delegation to undertake day-to-day administrative decisions related to the operation of the Torres Strait Fisheries Act.24

2.35 The instruments related to the operationalisation of the Torres Strait Fisheries Act include the Torres Strait Fisheries Regulation 1985 as well as:

- two Proclamations;

- four Declarations;

- one Determination; and

- three Management Plans (for tropical rock lobsters, finfish and prawns).

2.36 In addition, fisheries management instruments and fisheries management notices, prescribing the conditions surrounding the taking of specific types of fish, are issued from time to time by the Commonwealth Minister responsible for fisheries on behalf of the PZJA.

Fisheries business rules

2.37 In addition to guidance developed to support fisheries officers when undertaking their duties in Australian waters in general, AFMA has developed a range of documents related to the management of fisheries in the Protected Zone which take account of obligations under the Torres Strait Treaty and supporting arrangements. These documents include the Guideline to assist officers dealing with PNG fishermen operating in Australian waters of the Torres Strait Protected Zone (published October 2017), which provides guidance on the conduct of investigations and apprehensions in the context of the Protected Zone.

2.38 AFMA has also contributed to the development of policy and guidelines for the operation of the PZJA. In particular, Fisheries Management Paper No.1 (May 2008) sets out the PZJA’s policy for the operation and administration of the consultative groups supporting its operation; and Fisheries Management Paper No.2 (April 2006) provides guidance for the formation of advisory panels for the allocation of fishing concessions in the Protected Zone.

2.39 AFMA advised that it also uses guidance developed by other entities, including:

- guidelines to address biosecurity risks associated with illegal foreign fishing boats, developed by the then Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (September 2011); and

- guidelines developed by the Department of Home Affairs (Maritime Border Command) describing the procedures to be followed when participating in operations leading to the apprehension of PNG nationals for illegal fishing in the Protected Zone (June 2018).

2.40 While a range of business rules exist, some of them were developed a number of years ago (in one instance, 2004), and it is difficult to establish whether the documents are up-to-date, due to the absence of a version history and date of next review. For example, a number of changes to the consultative structure of the PZJA have occurred since Fisheries Management Paper No. 1, which plays a key role in the administration of the Torres Strait fisheries, was endorsed in 2008. The Standing Committee, which has been presiding over and providing recommendations to the PZJA since 2010, is not included in prescribed arrangements set out in Fisheries Management Paper No 1. A revised Paper was developed by AFMA in 2015, but was not endorsed by the PZJA (See also paragraph 3.64).

2.41 AFMA should review its guidance documents to verify that they are up-to-date, and include the document version history and date of next review.

2.42 The large body of documents that supports the regulation of fisheries, in particular fisheries management instruments and notices, also guides the work of entities involved in Torres Strait fisheries, including fishers. Over the years, a large number of these documents have been issued, with, in most cases, the most recent revoking a previous one. The PZJA website includes a list of the notices and instruments, however the list available as at March 2019 had not been updated since October 2013, and included legislative instruments that are no longer current.25

2.43 AFMA, as the Commonwealth entity responsible for the day-to-day administration of the PZJA, should ensure that the list of the current fisheries management notices and instruments effective in Torres Strait on the PZJA website is up-to-date. Recommendation no.4 in Chapter 3 recommends that the information on the PZJA’s website is kept current. Up-to-date information would assist stakeholders, such as fishers and communities, to operate more effectively in Torres Strait.

3. Governance structures and joint activities

Areas examined

This chapter examines the governance structures and joint activities used to support cross-entity coordination and whether these structures and activities are effective in facilitating the administration of the Torres Strait Treaty (the Treaty), the monitoring of cross-border movements, and management of biosecurity and fisheries.

Conclusion

The governance structures and joint activities are largely effective to support cross-entity coordination. However, key policy decisions made by the Torres Strait Joint Advisory Council (JAC) are not adequately documented, and the risks associated with the impacts of a changing strategic and operational environment on the Treaty operation have not been analysed. The Protected Zone Joint Authority (PZJA) annual reports and website are not up-to-date.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at: documenting key JAC decisions; analysing risks to the operation of the Treaty relating to the changing strategic and operational environment; and ensuring that the PZJA’s annual reports and website are up-to-date.

Do governance structures support the operation of the Treaty and the coordination of activities?

The governance structures provide an effective framework to support the operation of the Treaty, but could be improved by the establishment of a central register to record key decisions reached by the JAC. Also, issues relating to the changing strategic and operational environment represent a risk to the enduring operation of the Treaty.

3.1 The Treaty establishes the governance structures supporting the implementation of the Protected Zone provisions (see Box 2).

|

Box 2: Torres Strait Treaty’s governance provisions for the Protected Zone |

|

Articles describing the governance structure to facilitate the implementation of the Treaty provisions relating to the Protected Zone include:

|

Note a: DFAT advised that the PNG Treaty Liaison Officer position has been vacant since 2016.

3.2 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), as the entity responsible for the administration of the Treaty, coordinates the governance structure supporting the Treaty’s operation. The Australian Treaty Liaison Officer, a DFAT officer, is supported by an office manager and is in regular communication with all entities to facilitate the implementation of the Treaty provisions.

3.3 The JAC is the central consultative body overseeing the implementation of the Treaty provisions and comprises representatives from Australian and PNG Government, Queensland Government and PNG Western Province Administration, and traditional inhabitants from Torres Strait and PNG treaty village communities. It is supported by four bilateral (PNG and Australia) advisory committees:

- the Traditional Inhabitants Meeting;

- the Fisheries Bilateral Meeting;

- the Environmental Management Committee; and

- the Health Issues Committee.

3.4 Each of these committees includes stakeholders from relevant Australian and PNG government entities. For the Australian side, DFAT coordinates the Torres Strait Inter-departmental Meeting, which aims to progress the action items arising from the JAC and the four advisory committees. The Inter-departmental Meeting includes representatives from the Australian, Queensland and local governments.

3.5 The JAC reports to the Foreign Ministers of Australia and PNG (Australia-PNG Ministerial Forum) through the Senior Officials Meeting, co-chaired by the relevant DFAT Deputy Secretary and PNG counterpart, and also provides input to the Bilateral Security Dialogue, co-chaired by the DFAT Secretary and PNG counterpart. The Senior Officials Meeting includes representatives from a range of Australian and PNG Governments’ law enforcement, immigration, customs, biosecurity and health entities. The Bilateral Security Dialogue comprises representatives from Australian and PNG Governments’ law enforcement and defence entities.

3.6 Additionally, DFAT coordinates two cycles of annual visits aimed at raising awareness of the Treaty provisions and at discussing relevant issues encountered by traditional inhabitants. These visits are known as Treaty Awareness Visits (when conducted in PNG); and Community Liaison Visits (when conducted in Australia). A range of Australian and PNG government entities participate in these visits, representing traditional inhabitants, immigration, law enforcement, environment, biosecurity, health and fisheries entities (see photograph at Figure 3.2).

3.7 Figure 3.1 provides a schematic overview of the Treaty governance structure.

Figure 3.1: Torres Strait Treaty governance structure

Source: ANAO.

3.8 ANAO’s review of the minutes and supporting papers available for the Treaty meetings for the period July 2014–June 2018 demonstrate that, overall:

- the meetings were conducted on a regular basis and according to schedule;

- attendance was sufficient to represent the key parties involved;

- documentation (minutes, supporting papers, agendas) was fit-for-purpose; and

- actions arising were recorded and followed up.

3.9 The JAC and bi-lateral advisory meetings involved a large number of participants from PNG and Australia (between 30 and 50) and were normally scheduled consecutively over one or more days to optimise participation and minimise expense. Many participants attended several meetings, which contributed to the sharing of information on matters that have relevance across more than one area (such as fisheries and environmental matters). Actions arising were generally recorded and tracked, in some cases using a traffic light system. Given the large number of parties involved, the complexity of some of the issues and the bilateral nature of the meetings, issues were often discussed and progressed across several meeting cycles.

Figure 3.2: DFAT-led Treaty Awareness Visit to one of the PNG Treaty Villages

Source: ANAO

3.10 An important function of the JAC, as prescribed by the Treaty, is to seek solutions to issues arising at the local level from the operation of the Treaty. JAC decisions have important implications for all parties involved in the operation of the Treaty provisions. For example, in 2003 the JAC endorsed a recommendation from the Traditional Inhabitants Meeting to allow a female spouse who was not born in a Treaty village but resided permanently in one of the Treaty villages through marriage to a male from that village, to be included in the free movement provisions of the Treaty. The reverse however (a male spouse who was not born in a Treaty village but resided permanently in one of the Treaty villages through marriage to a female from that village) was not agreed by the Traditional Inhabitants Meeting nor the JAC.

3.11 These decisions, which in effect become policy, are documented in the proceedings of the JAC, but are not recorded in a separate location accessible to all the entities who may need them. This means that, in time, these decisions can be hard to locate and parties are not always clear about which specific situations have been agreed to. For example, some PNG nationals living in Daru, the capital of Western Province (see map at Figure 1.2), have been allowed to travel in the Protected Zone because they used to live in the Treaty villages. However, Daru is not one of the 13 villages covered by the Treaty provisions. DFAT was not able to confirm how this decision was made and where it is recorded. A decisions register would increase the clarity and certainty of policy decisions made by the JAC about the operationalisation of the Treaty.

Recommendation no.2

3.12 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade establish and maintain a central register of policy decisions made by the Torres Strait Joint Advisory Council and ensure that the register is accessible to stakeholders, including Australian Government entities, operating in Torres Strait.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

3.13 DFAT has created a central register to capture key policy decisions made by the Joint Advisory Council. The register is held on the DFAT electronic filing system and will be available to stakeholders on request. In addition, DFAT is currently consulting with stakeholders including, Australian Government entities, traditional inhabitants and Papua New Guinea, to consider the publication of the Joint Advisory Council Meeting Summary Outcomes on the DFAT website. This would allow key policy decisions to be publically accessible and in a suitable format. DFAT is proposing to publish the outcomes following the last Joint Advisory Council meeting, conducted in March 2019.

3.14 The JAC meeting papers examined by the ANAO demonstrate that a number of issues have been regularly raised by JAC members over the years. These issues include:

- the impact of climate change on the islands of the Protected Zone and PNG Treaty villages, and the growing problem of drinking water availability;

- the changes in PNG demographics, including the increasing population in the PNG Treaty villages26, and the ensuing pressure on the Torres Strait Islands communities who receive their visits; and

- the difficulty of identifying which traditional inhabitants are covered by the Treaty provisions, given the increasing population in PNG Treaty villages and the ageing of the people who are able to identify them (Border Monitoring Officers, Australian Councillors and PNG village chairpersons).

3.15 DFAT, in the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper27, reaffirmed its commitment to preserving the integrity of the Treaty as a foundation to the border arrangements between Australia and PNG. To support this commitment, DFAT should conduct an analysis of the impact that the issues associated with the changing strategic and operational environment are having, or will have, on the Treaty and its enduring implementation.

Recommendation no.3

3.16 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade conduct an analysis of the risks associated with the impacts of a changing strategic and operational environment on the enduring implementation of the Torres Strait Treaty.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

3.17 DFAT is currently developing a framework for such an analysis. We are in discussions with stakeholders, including working with relevant areas of DFAT, other Australian Government entities, traditional inhabitants and academic experts as to how to best resource and fund this analysis, to meet the intent of the recommendation.

Do governance structures and joint activities support the control of cross-border movements?

Effective governance structures and joint activities support the control of cross-border movements and related law enforcement activities.

3.18 The key entities involved in law enforcement in Torres Strait are the Australian Border Force (ABF), Australian Federal Police (AFP) and Queensland Police Service. The ABF is responsible for the control of cross-border movements in Torres Strait and for law enforcement activities associated with these movements.28 The AFP’s role in Torres Strait is focused on the delivery of intelligence functions.29 The three entities recognise the importance of cooperation and partnership to address law enforcement issues in Torres Strait and participate in a range of governance groups that aim to support the prioritisation, coordination and management of joint agencies operations.

3.19 Figure 3.3 provides an overview of the governance arrangements and joint activities supporting the control of cross-border movements.

Figure 3.3: Governance structures and joint activities supporting the control of cross-border movements

Source: ANAO.

3.20 For Torres Strait, the ABF-led Regional Queensland Joint Intelligence Group and Regional Queensland Joint Operations Group aim to share information on key vulnerabilities and threats to cross-border movements and law enforcement and to conduct operations to address these vulnerabilities and threats. The groups are scheduled to meet every two months in locations alternating between Cairns, Mount Isa, Townsville and Thursday Island.

3.21 The ABF-led Joint Inter-Agency Planning Group, which has operated since early 2018, meets monthly and aims to ensure that stakeholders in Torres Strait have an opportunity to provide input into the surveillance priorities of the Australian Defence Force Regional Force Surveillance Group’s patrols.30 Entities invited to participate in the Joint Inter-Agency Planning Group include the ADF, AFP, Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA), Queensland Police Service and DFAT.

3.22 The ABF also organises bilateral Joint Cross-border Patrols between three to six times a year. These are described as collaborative intelligence collection activities between Australia and PNG border authorities. The Patrols are conducted under the terms of a memorandum of understanding between Australia and PNG31 and aim to gather information of interest to the participating entities, undertake measures that assist prevention and investigation of offences as well as raise awareness of each entity’s functions. The Patrols, which include participation from the AFP, Queensland Police Service, the PNG Immigration and Citizenship Authority, the PNG Customs Service and the Royal PNG Constabulary, take place over three to eight days during which a range of Treaty villages in PNG and Australian islands in the Protected Zone are visited.