Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Controls over Credit Card Use

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess whether select Australian Government entities are effectively managing and controlling the use of Commonwealth credit and other transaction cards for official purposes in accordance with legislative and policy requirements.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. This audit examined the credit card policies and procedures, training activities, and monitoring and control arrangements of the Australian Public Service Commission, the Fair Work Ombudsman and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

2. For the purposes of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, Commonwealth credit cards include charge cards (such as Diners cards and American Express cards), vendor cards (such as fuel cards and Cabcharge FASTCARDs) and credit vouchers (such as Cabcharge eTickets).

Conclusion

3. All three entities examined had developed and implemented controls to support the appropriate issue, use and cancellation of credit cards. The controls were documented and disseminated through a combination of policies, procedures and administrative actions. Card issue and return was effectively controlled, although there were minor procedural deficiencies in the issuing of cards in the Australian Public Service Commission and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. Controls on individual purchases were operating effectively, with prompt acquittal and review in the Fair Work Ombudsman and Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

4. Policies on Australian Government fleet fuel cards were not adequate in the Australian Public Service Commission or the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. The three entities examined had adequate guidance in place for the issue, use and acquittal of Cabcharge eTickets. The reconciliation process for one of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s Cabcharge eTicket accounts was not adequately monitored.

Supporting findings

Use of travel and purchasing cards

5. Each of the entities had established an effective framework and guidance on the issue, use and cancellation of credit cards. There was also a designated credit card administrator/s within each entity’s Finance unit who undertook the central administration, including issuing and cancelling cards, and maintaining a register of credit cards. Guidance was based on a hierarchy linking the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 to Accountable Authority Instructions, detailed procedural rules, and credit card agreement and acknowledgement forms.

6. Each of the entities had effectively controlled the issue and return of credit cards. The ANAO assessed the controls in place by undertaking a detailed examination of a sample of 98 credit cards issued across the three entities. All of the cards assessed had been issued to officials identified as having a business need. The ANAO identified some instances in the Australian Public Service Commission where: credit card limit details recorded on the credit card register were incorrect; there was no record of approval for officials issued with credit cards; and cardholders had made transactions prior to signing the cardholder acknowledgement form. The ANAO identified seven instances (12 per cent of the sample tested) in the Department of Immigration and Border Protection where cards had been issued and there was no record of a signed cardholder agreement and acknowledgement form.

7. Each of the entities used online workflows which required pre-approval for travel and purchasing. The majority (94 per cent or more) of transactions tested had been appropriately authorised, were supported by evidence of acquittal (such as a receipt or tax invoice) and had been verified and approved consistent with entity requirements. Goods and services purchased were reasonable in light of the entities’ business needs and credit card policies.

8. The Australian Public Service Commission and Fair Work Ombudsman had identified risks from the use of credit cards and documented relevant controls in their fraud control plans. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection had documented relevant controls in its Financial Management Guidance on the use of credit cards. All entities had effective arrangements for the monitoring of controls. Each entity had completed at least one internal audit on the use of credit cards during 2014–15 and compiled regular management reports on the use of credit cards.

Fuel cards

9. The Australian Public Service Commission and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection did not have policies, guidance or procedures in place for the use of Australian Government fleet vehicle fuel cards. The Australian Public Service Commission also did not undertake monitoring of its fuel card use. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s Accountable Authority Instructions refer officials to its Financial Management Guidelines for the key requirements relating to Commonwealth credit cards. This guideline explicitly states it does not apply to fuel cards and that officials must comply with the department’s Fleet Vehicle Instructions when issuing or using fuel cards. The department’s fuel card policy and procedural documents covering Australian Government fleet vehicle fuel card use were under development as at April 2016. The Fair Work Ombudsman had adequate policies, procedural documentation and systems to support the management and monitoring of Australian Government fleet vehicle fuel card use.

Cabcharge eTickets

10. The three entities examined had adequate guidance in place for the issue, use and acquittal of Cabcharge eTickets. While the Fair Work Ombudsman’s Accountable Authority Instructions established appropriate arrangements for the use of Cabcharge eTickets, the entity’s procedural guidance did not reflect the current electronic operating environment. The monthly eTicket reconciliation process for one of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s Cabcharge eTicket accounts was not adequately monitored and was not reviewed for overall Cabcharge billing accuracy prior to payment.

Recommendation

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 3.8 |

That the Australian Public Service Commission includes guidance around fuel cards in the entity’s Procedural Directions; and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection implement policy and procedural guidance for the use of all fuel cards issued to the department. Australian Public Service Commission’s response: Agreed. Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s response: Agreed. |

Summary of entities’ responses

Australian Public Service Commission

The APSC agrees with the findings of the audit report and accepts Recommendation No.1, that guidance around fuel cards is included in the Commission’s Procedural Directions. I would note that the Commission has one Statutory Office Holder as the sole user of the Executive Vehicle Scheme, and the sole user of fuel cards associated with this finding.

Fair Work Ombudsman

With respect to the commentary concerning the Fair Work Ombudsman, we acknowledge the issues raised and will tighten controls over the relevant areas, including updating guidance to reflect the electronic operating environment for Cabcharge eTickets, expand policies to specify time limits for the acquittal of non−travel credit cards and make it clear that splitting of transactions is not permitted, review the continued need for individuals to be issued with cards and update exit documentation. We will also reinforce the importance for drivers of fleet cars to provide accurate odometer readings when using fuel cards.

The report is useful in that it provides the Fair Work Ombudsman with information on where controls over credit card use are working satisfactorily as well as examples of a small number of areas where strengthening current processes and guidance will reduce risks associated with the potential inappropriate use of cards.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection

The Department recognises and appreciates the efforts of the Australian National Audit Office staff who conducted the audit. There was a significant Machinery of Government change with the integration of Australian Customs and Border Protection Service and the Department on 1 July 2015 to form a new organisation. This audit provided timely assurance over credit card control and use within the Department.

The Department agrees with the recommendation contained in the report and will finalise and issue its vehicle policy and procedural guidelines. The policy and procedural guidelines will include procedures regarding the use of fuel cards for leased and owned vehicles.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Credit cards offer a transparent, flexible and efficient way for Australian Government officials to obtain cash, goods or services to meet business needs. The misuse of credit cards can expose an entity to risks such as waste and fraud. Instances of misuse and weaknesses in relevant entity controls attract considerable parliamentary and public interest, and cause reputational damage to affected entities and the Australian Government.

1.2 Credit cards include charge cards (such as Diners cards and American Express cards), vendor cards (such as fuel cards and Cabcharge FASTCARDs) and credit vouchers (such as Cabcharge eTickets). All of these cards are a form of Commonwealth credit card for the purposes of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).

Australian Government framework for using credit cards

1.3 The Commonwealth Resource Management Framework (CRMF) governs how the Commonwealth public sector uses and manages public resources. The PGPA Act sets out the main principles and requirements of the CRMF and applies to all Commonwealth entities and Commonwealth companies. In July 2014, the Department of Finance issued model Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs) that contain the core topics that are applicable to the majority of officials in most non-corporate Commonwealth entities. The core model AAIs in relation to Australian Government credit cards are:

- only the person issued with a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, or someone specifically authorised by that person, may use that credit card, credit card number or credit voucher;

- you may only use a Commonwealth credit card or card number to obtain cash, goods or services for the Commonwealth entity;

- you cannot use a Commonwealth credit card or card number for solely private expenditure;

- in deciding whether to use a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, you must consider whether it would be the most cost effective payment option in the circumstances;

- before using a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher, you must ensure that the requirements in AAI—Approval and Commitment of Relevant Money, have been met before entering into the arrangement;

- you must ensure that your use of a Commonwealth credit card or credit voucher is consistent with any approval given, including conditions of the approval; and

- you must ensure that any Commonwealth credit cards and credit vouchers issued to you are stored safely and securely.

1.4 The PGPA Act also states that officials of a Commonwealth entity do not include consultants or independent contractors unless that person is prescribed by an Act or the rules to be an official of the entity. This broadly restricts access to Commonwealth credit cards to employees of the entity.

1.5 The use of credit cards and credit vouchers places responsibility on the cardholder to meet appropriate standards of accountability and transparency in purchasing and paying for goods and services. A key element of an effective control framework is that entities have policies and practices which support the approval, and timely acquittal and review of credit card and credit voucher expenditure.

Whole of Australian Government procurement

1.6 Whole of Australian Government (WoAG) coordinated procurement has been established by the Department of Finance (Finance) and is mandatory for all non-corporate Commonwealth entities subject to the PGPA Act. Relevant to this audit are the WoAG Travel Arrangements (the Arrangements) and the Australian Government fleet motor vehicle leasing and fleet management contract in which the controls framework for travel, purchasing and fuel cards operate.

1.7 The Arrangements encompass: domestic and international air services; travel management services; accommodation program management services; travel and card related services and car rental services. Under the Arrangements it is mandatory for entities to make payment for flights, domestic accommodation and car rental through a Diners Club account. The payments can be made using either a Corporate Travel Service Account (Virtual card) or Diners Club card-in-hand. Entities can also, at their discretion, make use of a ‘companion’ MasterCard (available through the Diners Club arrangement) for the payment of meals, incidentals and general purchasing.

1.8 The WoAG contract with SG Fleet Australia Pty Ltd (SG Fleet) commenced in December 2012. This contract includes the provision of a fuel management service covering the purchase of fuel for each Australian Government fleet vehicle (fleet vehicle) over the term of the contract. In accordance with this service, SG Fleet must maximise the number of outlets from which fuel can be purchased. To facilitate this, each fleet vehicle is generally issued with three fuel cards for use at different fuel retailers. These fuel cards are considered credit cards under the PGPA Act.

Cabcharge eTickets

1.9 Cabcharge eTickets are a single use credit voucher used to purchase taxi services. Generally, officials of Commonwealth entities use a Commonwealth Diners travel card or purchasing card, in accordance with entity policies, as the preferred method to pay for taxi services required for official purposes. Cabcharge eTickets (formerly known as Cabcharge taxi eTickets) are primarily used by officials when they do not have a Commonwealth credit card.

Figure 1.1: Examples of a Cabcharge eTicket

Source: http://www.cabcharge.com.au/products/.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.10 The objective of the audit was to assess whether select Australian Government entities are effectively managing and controlling the use of Commonwealth credit and other transaction cards for official purposes in accordance with legislative and policy requirements.

1.11 To form a conclusion against this audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- entities had effective arrangements in place to control the issue and return of Commonwealth travel and purchasing cards;

- controls over purchases on travel and purchasing cards were sound and operating effectively; and

- entities effectively issued, used, managed and monitored Australian Government fleet fuel cards and Cabcharge eTickets.

Scope

1.12 The scope of the audit included the credit card controls in three entities: the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC), the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP).

1.13 The audit focused on the arrangements for the issue, use, management and monitoring of Commonwealth travel and purchasing cards, Australian Government fleet vehicle fuel cards and Cabcharge eTickets. The ANAO obtained data between 1 July 2014 and 31 December 2015 for the three designated entities. The audit also considered management arrangements for each designated entity’s use of fuel cards and eTickets, and analysed SG Fleet’s FleetIntelligence database reporting and Cabcharge billing data.

Audit methodology

1.14 The audit included an examination of the entity’s credit card policies and procedures, training activities, and monitoring and control arrangements. The examination was undertaken by reviewing documentation, interviewing entity officials and undertaking audit testing. The audit examined the controls for the issue, use and cancellation of travel and purchasing cards. The assessment included a detailed examination of the application of controls by each entity for a non-statistical sample of cards. Each of the samples selected were based on the potential risks for misuse. The audit examined in detail the procedural requirements of each entity, as well as legislative and government policy requirements. Acquittal testing focused on timeliness, documentation held, review processes and the accuracy of the data compared to the documentation (for example, whether the amount on a receipt or invoice matched the amount charged). Additional credit card statistics for each of the entities is provided in Table 1.1.1

Table 1.1: Credit card statistics by entity

|

|

APSC |

FWO |

DIBP(a) |

|

Travel and Purchasing cards |

|||

|

Number of cards on issue |

139 |

558 |

3811 |

|

Number of credit card transactions in 2014–15 |

4226 |

28 209 |

127 254 |

|

Expenditure in 2014–15 |

$987 767 |

$4 112 977 |

$41 642 484 |

|

Fuel Cards |

|||

|

Expenditure in 2014–15 |

$707(b) |

$22 258 |

$544 763 |

|

Cabcharge eTickets |

|||

|

Number of Cabcharge accounts |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

Number of trips |

565 |

163 |

7828 |

|

Expenditure in 2014–15(c)(d) |

$20 775 |

$8 084 |

$349 948 |

Note a: DIBP includes the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service and the Department of Immigration.

Note b: The APSC’s fleet vehicle lease commenced on 5 January 2015.

Note c: Total expenditure includes: the fare including GST plus the Cabcharge service fee.

Note d: Cabcharge eTicket expenditure has been calculated by Cabcharge billing periods. Expenditure has been rounded to the nearest dollar.

Source: ANAO analysis of each entity’s financial transaction data, SG Fleet reporting data and Cabcharge transaction data.

1.15 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards, at a cost of approximately $539 087.

2. Use of travel and purchasing cards

Areas examined

This chapter examines the entities’ arrangements to control the issue and return of Commonwealth travel and purchasing cards, and the controls over purchases on travel and purchasing cards.

Conclusion

All three entities had developed and implemented controls to support the appropriate issue, use and cancellation of credit cards. The controls were documented and disseminated through a combination of policies, procedures and administrative actions. Card issue and return was effectively controlled, although there were procedural deficiencies in the issuing of cards in the Australian Public Service Commission and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. Controls on individual purchases were operating effectively, with prompt acquittal and review in the Fair Work Ombudsman and Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

Areas for improvement

During the course of the audit, the ANAO made a number of suggestions for minor procedural improvements for each entity in the management of controls over credit card use. Each of the entities had implemented the suggestions before this report was prepared.

2.1 Each entity used electronic systems to facilitate credit card administration, including for monthly creTdit card statement reconciliations and review. Table 2.1 outlines the type of credit cards issued to the officials of each entity and the purchases that can be made with the different credit cards.

Table 2.1: Type of travel and purchasing cards and their use by entity

|

Entity |

MasterCard |

Diners card |

|

Australian Public Service Commission |

Travel, taxi fares and goods and services. |

Travel, taxi fares and goods and services. |

|

Fair Work Ombudsman |

Goods and services. |

Travel, taxi fares. |

|

Department of Immigration and Border Protection |

Goods and services. |

Travel, taxi fares. |

Note: Travel includes domestic and international airfares, accommodation and car hire.

Source: ANAO analysis of entity data.

Did the entities have effective frameworks and guidance regarding the issue, use and cancellation of credit cards?

Each of the entities had established an effective framework and guidance on the issue, use and cancellation of credit cards. There was also a designated credit card administrator/s within each entity’s Finance unit who undertook the central administration, including issuing and cancelling cards, and maintaining a register of credit cards. Guidance was based on a hierarchy linking the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 to Accountable Authority Instructions, detailed procedural rules, and credit card agreement and acknowledgement forms.

2.2 The primary documents for establishing and communicating the proper management and use of credit cards in each of the entities was the Accountable Authority Instructions (AAIs), procedural guidance, forms for the receipt of the card, and the exit process from the entity. This information was available to officials on each entity’s intranet.

2.3 Cardholders for all entities were required to sign a form acknowledging their responsibilities before receiving a credit card, and return their credit card on leaving the entity. Training was also available for officials in all three entities. A summary of controls provided by entity guidance and other relevant plans is provided in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Credit card instructions and guidance

|

|

APSC |

FWO |

DIBP |

|

Responsibility for issuing and setting credit card limits |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Secure storage of credit card |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Documentation and acquittal requirements for transactions |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Independent review of cardholder transactions and acquittal |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Time limit for acquittal |

Yes |

Travel only |

Yes |

|

Not splitting transactions to circumvent financial delegations |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Return of card |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Review of continued need for card |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Periodic review of credit card usage |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: ANAO analysis of entity credit card instructions and guidance.

2.4 During the course of the audit, the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) updated its credit card manual with specified time limits for credit card acquittal, introduced a process for six monthly reviews of inactive cards and an electronic exit form.

2.5 There was scope for the FairWork Ombudsman (FWO) to strengthen the controls over credit card use and return by:

- specifying in guidance material the time limit for the acquittal of non-travel credit card purchases and that the splitting of transactions to keep within financial limits is not permitted;

- regularly reviewing an individual’s continued need for credit cards; and

- expanding the entity exit checklist to include signing and dating the return of the credit card, checking outstanding transactions and their documentation, and cancelling the card.

Did the entities effectively control the issue and return of credit cards?

Each of the entities had effectively controlled the issue and return of credit cards. The ANAO assessed the controls in place by undertaking a detailed examination of a sample of 98 credit cards issued across the three entities. All of the cards assessed had been issued to officials identified as having a business need. The ANAO identified some instances in the Australian Public Service Commission where: officials and credit card limit details recorded on the credit card register were incorrect; there was no record of approval for officials issued with credit cards; and cardholders had made transactions prior to signing the cardholder acknowledgement form. The ANAO identified seven instances (12 per cent of the sample tested) in the Department of Immigration and Border Protection where cards had been issued and there was no record of a signed cardholder agreement and acknowledgement form.

Issuing credit cards

2.6 The AAIs and procedural guidance of the entities established appropriate arrangements for the issue of credit cards in each entity. The policies and guidance covered such matters as: limiting the issue of credit cards to those officials with a business need; setting a credit limit appropriate to the business need; appropriate approval of the card issue; obtaining appropriate agreement and acknowledgement from the cardholder that they understand and will abide by the entity’s requirements; the responsibilities of cardholders; and the need to maintain records of credit card applications, cardholder agreement and acknowledgement forms and the issue of credit cards.

2.7 The ANAO assessed the credit controls in place by undertaking a detailed examination of a sample of 98 credit cards issued across the three entities to determine whether they were processed in accordance with entity requirements. The results from the ANAO’s testing are outlined in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Issuing credit cards: results from ANAO testing

|

Entity |

Number of cards tested |

Processed in accordance with entity requirements? |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

No |

|

Australian Public Service Commission |

20 |

65% |

35% |

|

Fair Work Ombudsman |

20 |

100% |

- |

|

Department of Immigration and Border Protection |

58 |

88% |

12% |

Source: ANAO analysis of entity credit card data, instructions and guidance.

Australian Public Service Commission

2.8 The ANAO assessed a sample of 20 credit cards issued in 2014–15 and found that 13 cards (65 per cent) complied with all the entity requirements. Of the remaining seven cards, the ANAO identified2:

- seven instances where credit card limit details recorded on the credit card register were higher than the information recorded by the card provider;

- three instances where there was no record of approval for officials issued with credit cards; and

- a single instance where a cardholder had made transactions prior to signing the cardholder acknowledgement form.

2.9 During the course of fieldwork, the APSC had rectified the issues with the recording of credit card limits with the card provider. All limits recorded on the credit card register were consistent with the credit card vendor information.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection

2.10 The ANAO assessed a sample of 58 cards and found that 88 per cent (51 cards) were issued in accordance with entity requirements. For the remaining 12 per cent (seven cards) there was either no record of a signed, or electronic, acceptance of the cardholder agreement form. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) informed the ANAO that during a Credit Card Governance Framework Improvement Project in early 2015, weaknesses were identified and some officials had been issued cards before agreements were signed. This process changed in 2015 and cards cannot be issued before an agreement form is signed.

Return and cancellation of cards

2.11 All three entities provided guidance on cancelling credit cards. In particular, the agreement and acknowledgement form signed by the cardholder typically specified that the card was to be returned on resignation or on transfer or promotion where the card was no longer required. Additionally, the APSC and FWO included on their employee separation certificates a requirement for card holders to return credit cards on departure from the entity.

2.12 The ANAO examined records related to all cards cancelled in 2014–15 for DIBP (1269 cards) and a selection of cards cancelled in that year for the APSC (10 credit cards) and FWO (20 credit cards). Audit testing in the APSC and FWO found that cancellation processes had been completed properly and no transactions had been entered into after the cards were cancelled. For DIBP, the ANAO identified 517 transactions across 36 credit card accounts that had occurred after an employee had been terminated. These transactions occurred during the cardholder’s employment and there had been a delay from the merchant in charging to the credit card.

Were purchases and transactions effectively controlled?

Each of the entities used online workflows which required pre-approval for travel and purchasing. The majority (94 per cent or more) of transactions tested had been appropriately authorised, were supported by evidence of acquittal (such as a receipt or tax invoice) and had been verified and approved consistent with entity requirements. Goods and services purchased were reasonable in light of the entities’ business needs and credit card policies.

2.13 The ANAO tested compliance against the entities’ requirements for timely acquittal and retention of documentation supporting credit card use by selecting:

- a random sample of monthly credit card statements and the associated transactions in each of the entities, to provide an understanding of how well credit card controls were operating; and

- samples of transactions for which there was a potentially higher risk of misuse or reduced effectiveness of controls, for example, transactions with high expenditure for an item.

2.14 The ANAO assessed compliance against each of the entities’ requirements for timely acquittal and retention of documentation supporting credit card transactions. Entity controls were applied by officials for the authorisation of credit card expenditure and maintaining appropriate supporting documentation. Entity control within the APSC could be strengthened by officials completing the acquittal and review of credit card expenditure within required timeframes. The overall results from the ANAO’s transactions testing for each entity are included in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Entity results from audit transaction testing

|

Entity |

Number of transactions tested |

Compliant with entity requirements |

|

Australian Public Service Commission |

211 |

94% |

|

Fair Work Ombudsman |

618 |

99.5% |

|

Department of Immigration and Border Protection |

1133 |

96% |

Source: ANAO analysis of entity data.

Transactions within monthly credit limits

2.15 Each of the entities had established limits for their cardholders. DIBP had both individual transaction and monthly limits on credit card expenditure, while APSC and FWO only had monthly limits. The monthly limit typically ranged from $2000 to $20 000, although some officials have monthly limits up to $55 000. The ANAO did not identify any instances where transaction or monthly credit limits were exceeded.

Australian Public Service Commission

2.16 The AAI’s and procedural guidance do not set limits for credit cards, however, the APSC intranet advised officials that the credit limits were ‘usually $2000 or $5000’. In practice, credit limits ranged from $2000 to $50 000. In some instances the credit limit was included in the credit card approval documentation3; others had no supporting documentation to identify why officials had a particular credit limit.

2.17 All transactions tested were within transaction and monthly credit limits. Many of the cardholders had credit limits much higher than their financial delegation. The ANAO identified five instances where officials had expended in one transaction an amount above their financial delegation, but within their credit card limit. It is not clear from the cardholder agreement and acknowledgement form and the financial delegations if this was acceptable and within the APSC credit card control framework.

2.18 During the course of the audit, in April 2016, the APSC implemented a standardised credit limit supported by business rules for the application of different limits. The APSC also advised that the entity was revising the financial delegations in light of changes driven by the Whole of Australian Government Travel Arrangements.

Regular review of inactive cards

2.19 The APSC credit card manual requires the credit card administrators and supervisors of cardholders to regularly review that cardholders have a continuing need for the credit card and the limit remains appropriate. As highlighted in paragraph 2.5, there was scope for FWO to improve its controls by regularly reviewing an individual’s continued need for credit cards. DIBP annually reviews credit card usage to detect cardholders who: have never used their credit cards; or have not used it for 12 months or more. Cardholders identified as meeting one or both of these criteria are notified via email and must justify a business need to retain the credit card to prevent it from being cancelled. DIBP advised in January 2016 that this was most recently completed in April/May 2015 and resulted in over 500 credit cards being cancelled.

2.20 The APSC provides all Executive Level and Senior Executive Service officials with a credit card. Lower level officials are only issued a credit card if there is an identified business need and appropriate approvals have been obtained. There would be value in the APSC reviewing if these officials continue to have a business need for the credit card and that the credit card limits remain appropriate. The majority of DIBP and FWO cards that had not been used were Diners related travel only credit cards.

2.21 A summary of the results of ANAO testing of inactive cards is outlined in Table 2.5

Table 2.5: Active and inactive travel and purchasing cards

|

Entity |

Number of cardholders |

Active |

Inactive |

|

Australian Public Service Commission |

189 |

75% |

25% |

|

Fair Work Ombudsman |

640 |

90% |

10% |

|

Department of Immigration and Border Protection |

3811 |

92% |

8% |

Source: ANAO analysis of entity travel and purchasing card data.

Did the entities adequately identify risks and have monitoring and reporting arrangements in place to provide assurance over credit cards?

The Australian Public Service Commission and Fair Work Ombudsman had identified risks from the use of credit cards and documented relevant controls in their fraud control plans. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection had documented relevant controls in its Financial Management Guidance on the use of credit cards. All entities had effective arrangements in place for the monitoring of controls. Each entity had completed at least one internal audit on the use of credit cards during 2014–15 and compiled regular management reports on the use of credit cards.

Risk assessments and Fraud Control Plans

2.22 The APSC Fraud Control Plan from 1 July 2013–30 June 2015 sets out the fraud control framework with which the Commission seeks to prepare, prevent, detect and respond to fraud. The APSC identified ‘Use of Government credit cards’ as one of 10 core areas of risk for fraud, with a risk level of moderate to low. The APSC last conducted a fraud risk assessment in 2012–13, which reviewed the control environment under the previous Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997. The APSC advised the ANAO that an updated Fraud Risk Assessment for 2015–16 was being prepared.

2.23 The FWO Fraud Control Plan 2014–16 provides a formal framework for managing and monitoring fraud risks and sets out the identified fraud risks, prevention, detection, and response initiatives adopted by the entity to control fraud. FWO identified two fraud risks in relation to the use of credit cards, both rated as moderate:

Officials travelling in groups arrange to withdraw funds for themselves and travelling partners, allowing individuals to fraudulently receive more than one travel allowance; and

Inappropriate use of credit cards for minor procurements (<$10,000).

2.24 The FWO Fraud Control Plan also documents the current control environment, and additional fraud control strategies. In May 2016, during the course of the audit, FWO finalised its 2016–18 Fraud Control Plan to reflect the introduction of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).

2.25 The DIBP Fraud Control and Anti-Corruption Plan 2015–17 outlines the strategy of DIBP (including the Australian Border Force) in respect of managing fraud and corruption. While the Plan does not make specific reference to the use of Australian Government credit cards, eight core domains of fraud and corruption risk are identified, one of which included:

Finance – fraudulent or corrupt misdirection of funds, creation of financial benefit or loss, manipulation of revenue.

2.26 Additionally, DIBP’s Financial Management Directive on the use of Credit Cards details the control environment and states that:

The use of the Commonwealth Credit Card and taxi e-Tickets can expose the department to risks of inappropriate or unauthorised expenditure. In order to minimise these risks, a number of requirements have been specified which officials must observe.

Periodic reviews and internal audit

2.27 All entities used an automated system in the management of credit cards, produced regular management reports and had undertaken at least one internal audit which reviewed credit card usage in 2014–15. The management reports and internal audits provided additional assurance to each of the entities that controls were operating effectively.

2.28 Management reports were provided regularly to the entities Chief Financial Officer including monthly non-compliance reports and acquittal status reports. Each of the entities also conducted periodic reviews of specific areas such as checks for potential non-compliance with travel and procurement rules and transactions over a set high value. DIBP also conducted monthly quality assurance activities to identify instances of non-compliance. Elements that are checked as part of monthly quality assurance activities include: personal expenditure on credit cards, unverified or unreviewed statements, and transactions marked as disputed by the cardholder. The activities included reviews over the population of the credit card transactions as well as targeted reviews of specific areas of higher risk.

2.29 The APSC and FWO had conducted internal audits that reviewed financial controls and substantive testing of transactions to identify the level of non-compliance with internal policy and legislative requirements. Both entities had acted on the findings and recommendations of the audit and implemented changes to processes as a result.

2.30 Prior to the integration, the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS) built an analytical tool to enable the Internal Audit area to monitor credit card transactions. The ACBPS had completed an internal audit in June 2015 comparing the results of four audits undertaken for the period February 2013 to February 2015. The internal audit also identified that the results from the regular monitoring and internal audits had led to changes in officials’ behaviour such as reduced levels of non-compliance for split transactions and retention of invoices.

3. Other credit cards and credit vouchers

Areas examined

This chapter examines the issue, management and monitoring of other credit cards and credit vouchers including Australian Government fleet vehicle fuel cards and Cabcharge eTickets held by the Australian Public Service Commission, the Fair Work Ombudsman, and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

Conclusion

Controls over Australian Government fleet fuel cards were not adequate in the Australian Public Service Commission or the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. The Australian Public Service Commission did not have a policy or procedural guidance in place for the use of fuel cards. The Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s fleet policy and procedural guidance remain under development and the draft policy and procedural guidance did not cover the use of fuel cards for the entity’s asset (owned) vehicles. The Fair Work Ombudsman had adequate controls in place covering the use, management and monitoring of its fleet fuel cards.

The three entities examined had adequate guidance in place for the issue, use and acquittal of Cabcharge eTickets. The reconciliation process for one of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s Cabcharge eTicket accounts was not adequately monitored.

Areas for improvement

There is one recommendation for the Australian Public Service Commission and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection. That the:

- Australian Public Service Commission include procedural guidance around fuel cards in the entity’s Procedural Directions; and

- Department of Immigration and Border Protection finalise and issue its vehicle policy and vehicle procedural guidelines ensuring that all fuel cards issued to the department are referenced.

The ANAO suggested that:

- the Fair Work Ombudsman updates its guidance on Credit (Cabcharge) Vouchers to reflect the current electronic operating environment (paragraph 3.28).

Did the entities have adequate guidance and systems in place to manage Australian Government fleet fuel cards?

The Australian Public Service Commission and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection did not have policies, guidance and procedures in place for the use of Australian Government fleet vehicle fuel cards. The Australian Public Service Commission also did not undertake monitoring of its fuel card use.

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s Accountable Authority Instructions refer officials to its Financial Management Guidelines for Commonwealth Credit Cards. This guideline explicitly states it does not apply to fuel cards and that officials must comply with the Fleet Vehicle Instructions when issuing or using fuel cards. The department’s fuel card policy and procedural documents covering Australian Government fleet vehicle fuel card use were under development as at April 2016.

The Fair Work Ombudsman had adequate policies, procedural documentation and systems to support the management and monitoring of Australian Government fleet vehicle fuel card use.

3.1 The Australian Government’s fleet management and lease services contract with SG Fleet includes the provision of a Fuel Management Service (as discussed in paragraph 1.8). The fuel cards issued by SG Fleet for each fleet vehicle have several in-built controls. These controls include:

- timely loading of fuel card transaction data into SG Fleet’s FleetIntelligence database;

- the provision of monthly reporting on fuel usage by SG Fleet to entities;

- visibility by the entity of fuel card transaction data on SG Fleet’s FleetIntelligence database;

- implementation of security measures on fuel cards such as Personal Identification Number (PIN) control; and

- limiting fuel purchases to the type of vehicle, and subject to an entity’s policy on the purchase of non-contracted items such as lubricants, auto-care, car wash, minor parts and shop items.

3.2 Entities can also cancel or suspend a fuel card at no charge, by written advice, telephone or other electronic means. Following two business hours from receipt of the participant’s request the entity is no longer responsible for any costs or charges incurred due to the use of the fuel card.

3.3 Under the Whole-of-Australian-Government (WoAG) fleet motor vehicle leasing and fleet management contract, SG Fleet must maximise the number of outlets from which fuel can be purchased. To facilitate this, each fleet vehicle is generally issued with three fuel cards for use at different fuel retailers. These fuel cards are considered credit cards under the PGPA Act.

3.4 Entities are responsible for developing and implementing any additional controls to support the appropriate use of their fleet vehicle fuel cards. This includes guidance and procedures for the use of fuel cards.

3.5 A summary of ANAO findings are outlined in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Fuel Cards: Summary of ANAO findings

|

|

APSC |

FWO |

DIBP |

|

Number of Fleet Vehicles |

1 |

30 |

417 |

|

Number of Fuel Cards |

3 |

90 |

1191 |

|

Expenditure in 2014–15 |

$707 |

$22 258 |

$544 762(a) |

|

Expenditure in 2015–16(a) |

$501 |

$6 586 |

$149 395 (a)(b) |

|

Did the entity have adequate policies and procedures in place? |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Were there adequate systems in place to monitor fuel card use? |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Note a: Expenditure is for the period 1 July 2015 to 30 September 2015.

Note b: Expenditure includes both the Australian Customs and Border Protection and Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s fleet vehicle fuel cards.

Source: ANAO analysis of entity policy and guidance, and FleetIntelligence database reporting.

3.6 The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) did not have policies, guidelines, or procedural documentation in place covering fuel cards and did not monitor their usage. The APSC’s vehicle contract with SG Fleet has been in place since 5 January 2015.

3.7 The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) did not have policies, guidelines, or procedural documentation in place covering the use of fuel cards. The department’s Accountable Authority Instructions refer officials to its Financial Management Guidelines for Commonwealth Credit Cards. These guidelines state officials must comply with the Fleet Vehicle Instructions when issuing or using fuel cards. DIBP provided the ANAO with a draft policy and procedural guidelines on 26 October 2015. As at April 2016 these documents remained under development.

Recommendation No.1

3.8 That the Australian Public Service Commission includes procedural guidance around fuel cards in the entity’s Procedural Directions; and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection implement policy and procedural guidance for the use of all fuel cards issued to the department.

Australian Public Service Commission’s response

3.9 The APSC agrees with the findings of the audit report and accepts Recommendation No. 1, that guidance around fuel cards is included in the Commission’s Procedural Directions.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s response

3.10 Agreed. The Department will implement policy and procedural guidelines for the use of all fuel cards by August 2016.

Fuel card status reports

3.11 The ANAO analysed SG Fleet fuel card status reporting for each entity. In FWO’s fuel card status reporting between July 2014 and December 2015, the ANAO found that nine fuel cards were reported as missing for four vehicles and replaced. In the case of two of the four vehicles, the fuel cards were provided with the wrong vehicle by the dealer and delivered on the same day at different locations. In the other two instances, the fuel cards were identified as missing by the Fair Work Ombudsman’s (FWO) Support Services Officers during monthly vehicle checks. FWO advised the ANAO that after these instances a review of fuel card storage was undertaken and that losses have since been minimised.

3.12 As at 20 November 2015, DIBP had 417 fleet vehicles and 1191 fuel cards issued to active lease fleet vehicles. SG Fleet fuel card status reporting showed that the department had an additional 45 fuel cards with an ‘active’ status for vehicles that had not been assigned to a vehicle registration number as these vehicles were on order. When the vehicles are registered with the local road authorities, the cards are activated and assigned to the vehicle registration number.

3.13 DIBP’s fuel card status reporting between 1 July 2014 and 20 November 2015 identified DIBP had four fleet vehicles with four active fuel cards each—in each case two fuel cards were for the same retailer. DIBP advised the ANAO that the cancellation of replacement cards was not actioned by SG Fleet. This report also showed that 51 of DIBP’s 417 fleet vehicles (12 per cent) have had a fuel card replaced after being identified as missing. To ensure timely identification of lost fuel cards and to minimise losses, controls over fuel cards could be strengthened through the inclusion in the guidelines of a requirement to regularly sight fuel cards.

3.14 DIBP advised the ANAO that 20 of its 61 domestic asset (owned) vehicles also had SG Fleet issued fuel cards. The department advised it had central oversight of the SG Fleet fuel cards which were issued to 20 of the owned vehicles as they were recorded on the SG Fleet FleetIntelligence database. The department further advised that local management arrangements existed for the purchase of fuel and monitoring the use of the remaining owned vehicles.

3.15 The department’s draft fleet vehicle policy and guidance documents did not cover fuel card use for asset vehicles. DIBP advised the ANAO that fleet vehicle policy and guidance including fuel cards would also apply to asset vehicles. The ANAO found no reference to asset vehicle fuel cards in the draft fleet vehicle policy or guidance. As fuel cards are considered credit cards under the PGPA Act, all fuel cards provided for use by DIBP officials should be covered in its policy and guidance.

Invalid odometer reading reports

3.16 There are two risks associated with supplying invalid odometer readings: it may conceal some misuse or fraud; and it detracts from the capacity of both SG Fleet and the entity to effectively manage its fleet, which may have safety implications for drivers, passengers and other road users.

3.17 The ANAO analysed FWO’s SG Fleet invalid odometer reading reports for the 24 months to 7 December 2015. This reporting showed that 20 of FWO’s fleet vehicles recorded 49 instances of invalid odometer readings during the period. The number ‘777’ was used instead of the correct odometer reading in 10 instances (20 per cent). Three of the 20 vehicles each recorded between six and eight instances of invalid odometer readings. FWO advised the ANAO that invalid odometer readings are mainly the result of officials not remembering the odometer reading at the retailer pay point and information had been added to the car user folder, which highlights the requirement to present the correct odometer reading to the retailer console operator. FWO also advised the ANAO that when Support Services Officers are aware that incorrect odometer readings are provided, generally a phone call is made to the relevant officials to remind them of their responsibilities.

3.18 DIBP had 753 instances of invalid odometer readings against 242 of the department’s4 fleet vehicles in 2014–15 and 462 instances of invalid odometer against 232 of its fleet vehicles in 2015–16. Of these instances:

- 161 invalid odometer readings were recorded as ‘777’ or ‘7 777’ in 2014–15; and

- 95 invalid odometer readings were recorded as ‘777’ or ‘7 777’ in 2015–16.

3.19 DIBP advised the ANAO that ‘777’ is the default number recorded when the odometer reading is by-passed with no number being entered at the point of sale—generally as a result of drivers not being aware of their responsibilities. DIBP advised the ANAO that this has been addressed through monthly monitoring where the covering email describes the different fuel supplier reporting methods.

Excessive overfill reports

3.20 Excessive overfill reports record the number and volume of fuel overfills—where the fuel obtained and paid for exceeds the recorded capacity of the fuel tank.

3.21 The ANAO found that FWO had no excessive fuel overfill exception reports5 recorded over the period July 2014 to 7 December 2015. Three of DIBP’s fleet vehicles were identified as having had excessive fuel overfills over a 36 month period. One of these was an error in fuel tank size recorded by SG Fleet and resolved. DIBP advised the ANAO that at the time of the overfill the department and SG Fleet responded with a ‘watch and act’ if the overfill occurred again—this would rule out operator error. The department also advised that it would undertake further investigation if repeat overfills are identified involving the same vehicle or driver and that discussions with SG Fleet will occur to incorporate real time reporting if overfills are recorded in the future.

Did the entities have adequate guidance in place to manage Cabcharge eTickets?

The three entities examined had adequate guidance in place for the issue, use and acquittal of Cabcharge eTickets.

While the Fair Work Ombudsman’s Accountable Authority Instructions established appropriate arrangements for the use of Cabcharge eTickets, the entity’s procedural guidance did not reflect the current electronic operating environment.

The monthly eTicket reconciliation process for one of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection’s Cabcharge eTicket accounts was not adequately monitored and was not reviewed for overall Cabcharge billing accuracy prior to payment.

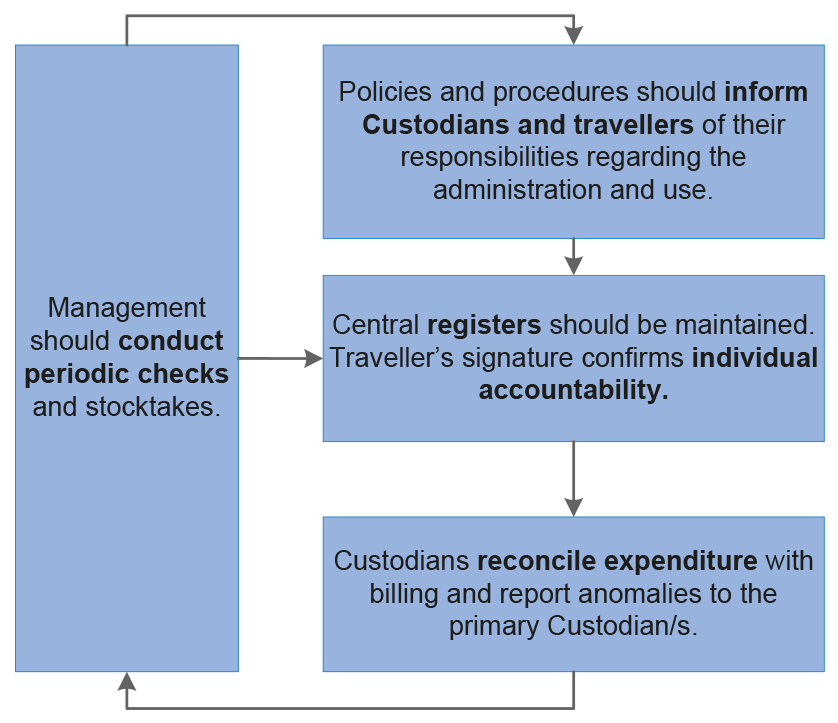

3.22 Entities are responsible for developing and implementing controls to support the proper use of credit cards and credit vouchers. This includes advising officials of their responsibilities in relation to the use of credit cards and credit vouchers. Figure 3.1 outlines the process for managing Cabcharge eTickets.

Figure 3.1: Cabcharge eTicket process

Source: ANAO analysis of entity procedures.

3.23 The three entities examined had a total of five Cabcharge accounts. These entities undertook a total of 10 434 taxi trips using Cabcharge eTickets as recorded between 1 July 2014 and 31 December 2015, with a total expenditure of $467 772.

3.24 A summary of ANAO findings are outlined in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: Cabcharge: Summary of ANAO findings

|

|

APSC |

FWO |

DIBP |

|

Number of accounts |

1 |

1 |

3 |

|

Number of eTickets used in 2014–15 |

565 |

163 |

7828 |

|

Expenditure 2014–15 |

$20 775 |

$8 084 |

$349 948 |

|

Was there adequate guidance in place for the issue, use and acquittal of Cabcharge eTickets? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Were there adequate systems in place to monitor Cabcharge eTicket use? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: ANAO analysis of entity policy and guidance and Cabcharge billing data.

3.25 The AAIs and procedural guidance of the three entities established arrangements for the issue and use of Cabcharge eTickets. The policies and guidance covered, to various degrees: administration; limiting the issue of eTickets to officials with a business need; approval of the business need; the responsibilities of the eTicket holder; and the need to maintain records of the stock held, the issue and use of eTickets.

3.26 The preferred method for officials of all three entities to pay for taxi and car hire services is a Commonwealth Credit Card. Cabcharge eTickets are available on request for those without a Commonwealth Credit Card with a legitimate business need. In addition, DIBP’s guidelines specify a single journey limit of $200 for those issued with an eTicket.

Australian Public Service Commission

3.27 The ANAO analysed the APSC’s Cabcharge billing data for 1 July 2014 to 31 December 2015. The ANAO’s analysis included a review of transactions outside of standard business hours (excluding transactions that appeared to be for travel to and from airports) and any other patterns in eTicket use. The APSC used 565 eTickets in 2014–15 at a total cost of $20 775. The ANAO identified nine Cabcharge transactions which were outside of standard business hours or showed a pattern in usage. The APSC advised the ANAO that the nine transactions were issued and used in accordance with a legitimate business need.

Fair Work Ombudsman

3.28 The terminology and the practical application of FWO’s credit (Cabcharge) voucher guidance were outdated. The ANAO suggests that FWO’s guidance be updated to reflect the use of electronic eTickets.

3.29 FWO used 163 eTickets in 2014–15 at a total cost of $8 084. The ANAO analysed transactions outside of standard business hours (excluding transactions that appeared to be for travel to and from airports) and any other patterns in eTicket use. The ANAO identified 10 Cabcharge transactions in the full data set which were outside of standard business hours or showed an unexplained pattern in usage. FWO advised the ANAO that the 10 transactions were issued and used in accordance with a legitimate business need.

Department of Immigration and Border Protection

3.30 The ANAO analysed DIBP’s Cabcharge billing data for 1 July 2014 to 31 December 2015. The ANAO’s analysis included a review of transactions outside of standard business hours (excluding transactions that specifically indicated travel to and from airports), trips over the value of $200 (in accordance with DIBP policy) and any other patterns in eTicket use. DIBP used 7828 eTickets in 2014–15 at a total cost of $349 948. ANAO analysis identified 282 Cabcharge transactions which were used outside of standard business hours.6

3.31 The department advised the ANAO that eTickets were issued by local managers in accordance with operational requirements. For the issue and use of Cabcharge eTickets, DIBP further advised the ANAO that departmental managers and employees were guided by the department’s Chief Executive Instructions and later the Accountable Authority Instructions (under the PGPA Act).

3.32 The ANAO’s analysis also identified that the department’s former Australian Customs and Border Protection Cabcharge (ACBPS) account had one eTicket used twice in 2015; and three transactions over the $200 DIBP eTicket policy limit per trip. DIBP advised the ANAO that during the course of the audit the duplicate eTicket usage and one of the transactions over $200 were referred to Cabcharge for investigation and these matters were resolved. The other two Cabcharge eTicket transactions in breach of the department’s $200 trip limit policy were approved in accordance with entity requirements.

3.33 The anomalies outlined in paragraph 3.32 highlighted a gap in the controls framework for the former ACBPS Cabcharge eTicket account which was not adequately monitored against the department’s travel policy and was not reviewed for overall Cabcharge billing accuracy prior to automatic electronic payment.

3.34 During the course of the audit DIBP advised the ANAO that the electronic management system used to manage the former ACBPS Cabcharge account was in the planning phase of being decommissioned. DIBP further advised the ANAO that once the system is decommissioned, officials who would have been eligible to access Cabcharge eTickets will be required to pay for taxi services using a corporate credit card or on a reimbursement basis.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Entity responses

Appendix 2: Department of Immigration and Border Protection: Machinery of Government changes: September 2013 to July 2015.

Following the Administrative Arrangements Order of 18 September 2013, the Department of Immigration and Citizenship was renamed the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS) became a DIBP portfolio agency.

Further changes to the portfolio were announced on 9 May 2014. These changes resulted in the consolidation of the department and the ACBPS into a single department—DIBP from 1 July 2015. Within the department, a new single operational border organisation—the Australian Border Force—was established to draw together the border operations, investigations, compliance, detention and enforcement functions of the two existing agencies.

Footnotes

1 The Australian Customs and Border Protection Service integrated with the Department of Immigration and Border Protection on 1 July 2015 (see Appendix 2). Prior to this date they were separate entities with their own policies and procedures and financial systems. The ANAO tested against the policies and procedures that were relevant at the time of the expenditure.

2 For three cards more than one issue was identified.

3 For example, approval for a credit card included the reasons for a specific credit limit.

4 DIBP figures incorporate separate reporting provided for ACBPS and DIBP fleet vehicles in 2014–15.

5 Fuel overfill reports list instances where the number of litres purchased exceeds the vehicles tank size.

6 Of these transactions, 172 were from DIBP’s former ACBPS Cabcharge account.