Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Compliance with Foreign Investment Obligations for Residential Real Estate

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO) and Treasury’s management of compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Government’s policy for foreign investment in residential property is to channel foreign investment into new dwellings to support additional jobs in the construction industry as well as economic growth.1 Foreign investment applications are considered in light of that policy and the overarching principle that the proposed investment should increase Australia’s housing stock.

2. Foreign investors are required to receive approval before acquiring an interest in residential real estate. Taking an interest in residential real estate prior to receiving approval is a breach of the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975. Australia attracts a large volume of foreign investment applications for residential real estate, with 40 149 applications in 2015–16, and approvals that year totalling $72.4 billion in proposed investments.

3. In the 2015–16 Budget, the Government announced a package of measures aimed at strengthening Australia’s foreign investment framework. The package was introduced in response to a:

- Senate committee inquiry report in 2013, Foreign Investment and the National Interest, which included 29 recommendations; and

- House of Representatives committee 2014 Report on Foreign Investment in Residential Real Estate, which included 12 recommendations.

4. Subsequent to the two reports, responsibility for residential real estate under the foreign investment framework was transferred from the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), including the collection of fees, upfront screening, compliance and enforcement. Further, the ATO was responsible for establishing a register of foreign investment in agricultural land and residential real estate.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) selected foreign investment in residential real estate for audit because of the extent of parliamentary and public interest in the issue, including concerns that foreign investors were not complying with foreign investment obligations and purchasing properties they were not entitled to own. The audit would also indicate the impact on compliance with foreign investment in residential real estate arising from the change in administrative arrangements.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s and Treasury’s management of compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate.

7. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted three high level criteria:

- compliance and enforcement strategies and detection arrangements were in place to support compliance activities;

- activities were undertaken to promote voluntary compliance and effectively address identified instances of potential non-compliance; and

- the effectiveness of compliance arrangements was monitored and reported.

Conclusion

8. The ATO’s management of compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate is becoming effective as it progressively implements more sophisticated approaches to encourage compliance and detect and address non-compliance.

9. The ATO has developed processes for compiling a land register of residential real estate but faces considerable challenges in populating the register with reliable data in coming years, which it needs to overcome in order to be effective.

10. The ATO has assessed and addressed compliance risks in relation to foreign investment obligations for residential real estate but has not yet compiled and implemented a compliance and enforcement strategy. To promote voluntary compliance with those obligations, the ATO has developed a series of communication strategies. The strategies, which have largely been implemented, incorporate a multi-platform communication approach targeting key audiences with priority messages.

11. The ATO has undertaken a significant amount of work to develop processes and systems to support the detection and investigation of non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate. There are a number of minor enhancements the ATO could make to improve its largely effective investigation processes, with more substantial work required in its development of processes to actively detect non-compliance.

12. Monitoring and reporting on compliance activities for foreign investment in residential real estate has been expanded with the transfer of responsibilities from Treasury to the ATO. Many indicators have been developed to measure the success of compliance activities and external reporting established for compliance investigations, outcomes and penalties. The monitoring and reporting arrangements are largely effective, and could be strengthened by more broad coverage of effectiveness—of the ATO in managing the overall compliance risk and Treasury in meeting the policy intent for foreign investment in residential real estate.

Supporting findings

National residential land register

13. The ATO has been compiling a land register of residential real estate by tracking settlements that have occurred since 1 July 2016, and intends to populate the register by December 2018 and report thereafter. The register will use property data from state and territory land titles offices that contains foreign investment identifiers such as foreign investment application number and passport number. In light of the time required for the states and territories to pass legislation to enable the provision of property transaction data with foreign investment identifiers, the ATO has developed interim arrangements to populate the register using data obtained through self-registration processes by foreign investors who have purchased residential real estate.

14. The ANAO’s analysis identified serious deficiencies in populating the register with reliable data. There is likely under-reporting of self-registrations2, over-reporting of foreign identity information in state property data3 and low levels of matching between datasets for foreign investment applications, self-registrations of foreign investment in residential property and state property data.4 Consequently, the ATO will need to undertake extensive manual verification processes in coming years to enable the register to provide accurate information about the nature and extent of foreign investment in residential real estate and produce reliable intelligence for compliance purposes.

Compliance strategies and voluntary compliance

15. The ATO does not have a compliance and enforcement strategy but has a reasonable basis for developing such a strategy, as it has undertaken a risk assessment of foreign investment in residential real estate and identified corresponding risk treatments. In preparing a compliance and enforcement strategy, the ATO should analyse compliance outcomes to inform targeted compliance approaches, address weaknesses in existing controls and incorporate measures of control effectiveness.

16. The ATO’s information about foreign investment in residential real estate is comprehensive and readily accessible to foreign investors, stakeholders and the general public through the websites of the ATO and the Foreign Investment Review Board, which include information products in one language other than English (Chinese). There is also a residential foreign investment real estate help line and email inbox, avenues for community and stakeholder engagement, and use of social media. Activities are managed through an up-to-date communication strategy. There would be benefit in the ATO undertaking a broad evaluation of the residential foreign investment communication program to inform future communication strategies.

Detection and investigation

17. The ATO has partially effective processes to detect non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate. It detected some 4300 cases of potential non-compliance from mid-2015 when it gained responsibility for compliance through January 2018, mainly from community or self referrals or through approval processes for foreign investors. While the ATO has established a data matching program to actively detect non-compliance, as at April 2018 the program had not addressed all identified key compliance risks and more work was required to mature its processes for actively detecting non-compliance.

18. The ATO has developed and implemented a largely effective program to address identified cases of potential non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate in a limited timeframe. Since gaining compliance responsibilities from Treasury in May 2015 through January 2018, the ATO completed 3940 investigations that identified 1158 breaches and resulted in 1067 financial penalties totalling some $5.5 million, and the disposal of 231 foreign-owned properties valued at $284.9 million.5 The key challenge for the ATO going forward will be addressing the more serious instances of non-compliance with the foreign investment framework; namely, demonstrating wilful non-compliance with obligations and applying criminal and civil penalties. There is also scope for the ATO to improve processes for escalating cases for investigation.

Monitoring and reporting

19. The ATO has over 20 indicators of success for its compliance activities for foreign investment in residential real estate, which it has measured for inclusion in a variety of internal communication and compliance processes. However, the ATO has not yet used the results to broadly assess its effectiveness in managing the overall compliance risk that ‘failure of foreign persons to comply with residential real estate foreign investment rules will undermine the integrity of the foreign investment framework and community confidence’. Similarly, Treasury has not measured effectiveness in achieving the stated policy intent of encouraging foreign investment in new residential dwellings.

20. The ATO and Treasury have largely effective arrangements in place to report on compliance activities for foreign investment in residential real estate, which could be strengthened by more broadly reporting on the effectiveness of those activities. The ATO has extensive internal reporting on compliance activities for foreign investment in residential real estate and shares this information with Treasury. Consequently, the extent of coverage in the Foreign Investment Review Board’s annual reports and Regulator Performance Framework reports has expanded since 2014–15, and includes information on compliance investigations, outcomes and penalties imposed.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.13

The Australian Taxation Office compiles and implements a residential foreign investment compliance and enforcement strategy, which draws on existing risk assessment and treatment documentation and information about the results of prior compliance activities.

Australian Taxation Office’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 4.13

The Australian Taxation Office prioritises developing and finalising data matching rules to address key compliance risks to foreign investment in residential real estate.

Australian Taxation Office’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

21. A summary of entity responses is shown below, with full responses at Appendix 1.

Australian Taxation Office

The ATO appreciates the ANAO’s efforts to undertake this audit and to provide the feedback and suggestions contained within this report. The ATO considers this report to be supportive of our overall approach to managing the administration of the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 and the Government’s foreign investment policy for the foreign investor segment. The review recognises the efforts the ATO has made in a relatively short period of time to establish a new program of work for administering foreign investment obligations in respect of residential real estate.

In finding the ATO’s program to address identified non-compliance as largely effective, the review has identified a number of areas that the ATO could focus on to further enhance its effectiveness, particularly with regards to detection of non-compliance. The review also acknowledges the processes that the ATO has implemented to overcome some of the challenges that it faces in compiling a land register of residential real estate.

The ATO agrees with the two recommendations contained in the report.

Department of the Treasury

The Treasury welcomes the overall conclusions and findings of the audit.

While the report does not contain any recommendations for the Treasury, we will consider the key learnings within the report in the context of the Treasury’s role in relation to administering the foreign investment framework, including our overarching policy responsibilities.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key learnings identified in this audit report that may be considered by other government entities when implementing a compliance function.

Performance and impact measurement

Governance

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Australian Government’s policy is to welcome foreign investment, noting that foreign investment ‘has helped build Australia’s economy and will enhance the wellbeing of Australians by supporting economic growth and innovation into the future.’6 Foreign investment proposals are subject to the foreign investment framework and reviewed by the Australian Government on a case-by-case basis. The intention of the framework is to maximise investment flows, while protecting Australia’s national interests. Factors that can be considered when assessing the impact of foreign investment on national interests include national security, the effect on competition, Australian tax revenues, resource use and stock production.

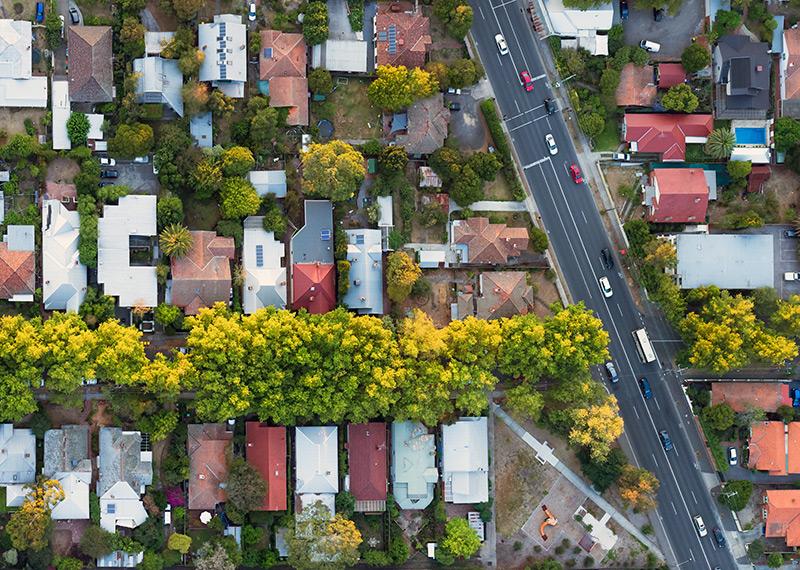

1.2 Foreign investment occurs across a range of markets, including business and land acquisitions (agricultural, mining and commercial), and residential real estate. Figure 1.1 illustrates the total value of foreign investment approvals ($247.9 billion) by sector in 2015–16.

Figure 1.1: Value of foreign investment approvals by sector, 2015–16 ($ billion)

Source: ANAO analysis of Foreign Investment Review Board information.

The foreign investment framework

1.3 Australia’s foreign investment framework primarily consists of the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 and Australia’s Foreign Investment Policy, which guide the Australian Government’s decision making process when considering foreign investment proposals.

1.4 The Department of the Treasury (Treasury) is responsible for the foreign investment framework and the Treasurer reviews foreign investment proposals on a case-by-case basis to ensure they are not contrary to Australia’s national interest. The Treasurer can make an order to prohibit a proposed foreign investment that is contrary to the national interest, or impose conditions on an investment on national interest grounds.7

1.5 Prior to 2015, Treasury was also responsible for compliance activities and assessing foreign investment applications. In the 2015–16 Budget, the Government announced a package of measures aimed at strengthening Australia’s foreign investment framework. The package was introduced in response to a Senate committee inquiry report in 2013, Foreign Investment and the National Interest, which included 29 recommendations.

1.6 Additionally, the House of Representatives committee Report on Foreign Investment in Residential Real Estate in 2014 included 12 recommendations. In response to the second recommendation8 of the 2014 report, Treasury delegated responsibility for residential real estate under the foreign investment framework to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), including the collection of fees, assessing applications, compliance and enforcement. Treasury retained responsibility for commercial real estate matters and other framework-wide administrative functions, such as external reporting.

1.7 The current foreign investment regime came into effect on 1 December 2015 and introduced the following features:

- stricter and more flexible penalties;

- an application fee regime;

- tighter rules relating to certain sectors (such as agriculture and critical infrastructure);

- an exemption certificate scheme for certain investments;

- a more stringent approach to foreign government investors; and

- creation of a register of foreign held interests in agricultural land and water.

1.8 Additionally, a register for foreign residential investment was established on 1 July 2016 and is expected to provide annual statistical reporting. Unlike the register for foreign investment in water and agriculture, there is no legislative requirement for the residential property register.

1.9 These changes to the foreign investment regime represented a new function within the ATO that required appropriate systems and processes to be put in place. The ATO received $47 million to implement its residential real estate program over four years from 2015–16. In 2015–16, the ATO’s total operating costs for the program were $9.2 million.9

Residential real estate

1.10 The foreign investment framework aims to channel foreign investment into new dwellings.10 The Foreign Investment Review Board states that this can create additional jobs in the construction industry, help support economic growth, and increase government revenues in the form of stamp duties and other taxes.11 The Australian Government’s Foreign Investment Policy states that foreign investment enhances the wellbeing of Australians by increasing production, employment and income.12

1.11 The number of applications for foreign investment in Australian real estate has been increasing over recent years, as outlined in Figure 1.2. The total value of foreign investment approvals for residential real estate in 2015–16 was $72.4 billion (as shown in Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.2: Number of applications for foreign investment in residential and commercial real estate

Source: ANAO analysis of Foreign Investment Review Board information.

1.12 Foreign investors are required to gain approval prior to acquiring an interest in Australian real estate13, and applications are considered in light of the overarching principle that the proposed investment should increase Australia’s housing stock by creating at least one new additional dwelling.14 The ATO has administered a new application fee for residential property from 1 December 2015.

Applications and approvals

1.13 Foreign investors can apply to purchase specific residential properties, or can apply for an exemption certificate to allow them to purchase a certain class of property in a specified state or territory. The type of approval required is determined by the type of residential property. Approvals also contain conditions that must be satisfied, such as time periods in which actions must be taken. In addition to approval conditions, an annual vacancy charge for dwellings that are not rented out or occupied for more than six months per year applies from May 2017, with the first 12 month period to end May 2018.

1.14 The approval process and corresponding conditions for foreign investors in residential real estate are outlined in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: Types of residential real estate available to purchase by foreign persons and associated approvals

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

Compliance and penalties

1.15 The ATO is responsible for detecting and investigating non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate. Non-complaint behaviour can include purchasing property without approval and not complying with approval conditions. While the ATO promotes voluntary compliance with foreign investment obligations, a number of intelligence channels are in place to assist it to detect non-compliance, including community referrals and referrals from other government departments. The ATO has also established a data matching program using data from other government departments and private sector entities to detect non-compliance.

1.16 Non-compliance with residential real estate obligations may result in the application of retrospective fees, penalties and infringement notices. The Treasurer can also require foreign investors to dispose of their interest in residential real estate in cases of non-compliance, by issuing a disposal order. As part of the reforms to the foreign investment framework, civil penalties were introduced and existing criminal penalties were strengthened.

Audit approach

1.17 The ANAO selected foreign investment in residential real estate for audit because of the extent of parliamentary and public interest in the issue, including concerns that foreign investors were not complying with foreign investment obligations and purchasing properties they were not entitled to own. The audit would also indicate the impact on compliance with foreign investment in residential real estate arising from the change in administrative arrangements.

1.18 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s and Treasury’s management of compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate.

1.19 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted three high-level criteria:

- compliance and enforcement strategies and detection arrangements were in place to support compliance activities;

- activities were undertaken to promote voluntary compliance and effectively address identified instances of potential non-compliance; and

- the effectiveness of compliance arrangements was monitored and reported.

1.20 The audit did not examine the:

- implementation of legislative changes to the foreign investment framework in 2015;

- assessment of applications;

- implementation of the annual vacancy charge; and

- responsibility of Treasury to administer the foreign investment framework in relation to business, agricultural land and commercial land proposals.

Audit methodology

1.21 The audit methodology included reviewing internal ATO guidance, reporting, communication and evaluation plans, and interviewing key ATO and Treasury staff and stakeholders. The ANAO undertook data analysis of the application and self-registration data sets as well as state and territories land titles data. The ANAO did not receive any contributions from the public through its website in relation to this audit.

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $380 000.

1.23 Team members for this audit were Kylie Jackson, Renee Hall, Sonya Carter, Dung Chu, Fei Gao, Haydn Thurlow and Andrew Morris.

2. National residential land register

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the effectiveness of the ATO’s processes for compiling a national residential land register.

Conclusion

The ATO has developed processes for compiling a land register of residential real estate but faces considerable challenges in populating the register with reliable data in coming years, which it needs to overcome in order to be effective.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made two suggestions aimed at the ATO taking steps to ensure the accuracy of foreign identifier data in state and territory real property transfers reports (paragraphs 2.15 and 2.25), and increase the number of registrations of foreign purchasers of residential real estate to support completeness of the register in the near term (paragraph 2.20).

Is the ATO effectively compiling a land register of residential real estate?

The ATO has been compiling a land register of residential real estate by tracking settlements that have occurred since 1 July 2016, and intends to populate the register by December 2018 and report thereafter. The register will use property data from state and territory land titles offices that contains foreign investment identifiers such as foreign investment application number and passport number. In light of the time taken by the states and territories to pass legislation to enable the provision of property transaction data with foreign investment identifiers, the ATO has developed interim arrangements to populate the register using data obtained through self-registration processes by foreign investors who have purchased residential real estate.

The ANAO’s analysis identified serious deficiencies in populating the register with reliable data. There is likely under-reporting of self-registrations, over-reporting of foreign identity in state property data and low levels of matching between datasets for foreign investment applications, self-registrations of foreign investment in residential property and state property data. Consequently, the ATO will need to undertake extensive manual verification processes in coming years to enable the register to provide accurate information about the nature and extent of foreign investment in residential real estate and produce reliable intelligence for compliance purposes.

Background

2.1 As noted in Chapter 1, the Government agreed to a recommendation from a 2014 House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics report that the ATO would establish a foreign ownership register, drawing from state and territory land title data collection processes.15

2.2 A key finding from the report was that there was no accurate or timely data that tracked foreign investment in residential real estate. Recommendation 8 was that the Government, in conjunction with the states and territories, establish a national register of land title transfers that records the citizenship and residency status of all purchasers of Australian real estate.16

2.3 The Government indicated that working with data from the states and territories would avoid duplication and reduce regulatory costs for purchasers of property. The Government’s response outlined that the intent of the register would be to provide essential information to better understand foreign investment trends and to aid in the detection of non-compliance with the foreign investment rules.

2.4 The national land register of foreign ownership consists of three components—agricultural land, water access entitlements and residential real estate. The registration of agricultural land and water access entitlements is required under legislation.17 To meet this requirement, the ATO established an online self-registration channel and completed a stocktake of foreign-owned agricultural property.18

2.5 There is no legislation underpinning the development of the residential land register. The ATO leveraged off the agricultural self-registration channel to require foreign investors to also register residential real estate acquisitions from 1 July 2016.

2.6 There will be no stocktake of foreign-owned residential real estate for the register. The volume of historical real property transactions was considered too time consuming and costly to capture.19 As indicated in paragraph 2.3, the intent was to rely on data from the states and territories, which is provided to the ATO for various purposes (including capital gains tax) to compile the residential land register. However, the states and territories were not collecting information necessary to develop the register, such as purchasers’ nationality and other foreign identifiers. Instead, a requirement for foreign investors to register details of a successful acquisition 30 days after settlement was introduced for approvals after 1 July 2016. This requirement was enforceable as a formal condition of approval for approvals after 1 July 2017.

Third-party data sharing arrangements

2.7 In 2013–14, the Australian Government announced a measure for the ATO to expand third-party data matching and reporting arrangements, which was deferred for one year in the 2014–15 Budget.20 The measure was intended to introduce a legislated reporting regime for the provision of real property data from the states and territories to replace the ‘inadequate approach’ of acquiring data using the ATO’s general powers of acquisition.21 Accordingly, there was a need to amend taxation legislation to provide the basis for the legislated reporting regime.

2.8 The measure was also expected to improve the integrity, and increase the quantity, of data reported by the states and territories to the ATO. The extended information reporting requirements were intended to: expand the data matching capability with third-party reporter information; improve integrity of the foreign resident capital gains tax regime; improve compliance for capital gains tax, goods and services tax and other taxable events; and support data sharing between government entities.

2.9 The revised data collection and reporting arrangements expanded the data provided by the states and territories to include information about the foreign identity of property purchasers and vendors, and was therefore expected to also support the compilation of the residential land register. The states and territories agreed to revise their respective legislation as they were otherwise unable to collect the additional data provided for under the new reporting arrangements, such as property vendor identity data or foreign entity data.22

2.10 While the Commonwealth legislative changes to support the revised reporting arrangements were implemented by 1 July 2016, most states and territories had not passed associated legislative changes by that time. Consequently, the revised reporting arrangements were not implemented from 1 July 2016, with the exception of New South Wales that was able to revise its legislation in time. Table 2.1 outlines the timing of the legislative changes and the number of real property transfer reports received by the ATO since 1 July 2016.

Table 2.1: Status of states and territories land holdings data sharing arrangements

|

Jurisdiction |

Date legislation passed allowing collection and reporting of foreign identity data |

First quarterly collection of foreign identity data |

Number of quarterly reports received by March 2018 |

|

New South Wales |

28 June 2016 |

1 July 2016 |

6 quarters reported |

|

Tasmania |

8 May 2017 |

1 July 2017 |

2 quarters reported |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

9 June 2017 |

1 July 2017 |

2 quarters reported |

|

Victoria |

22 June 2017 |

1 July 2017 |

2 quarters reported |

|

Queensland |

30 June 2017 |

1 Sept 2017 |

2 quarters reported |

|

Western Australia |

Legislation not passed |

|

1 quarter reported with some voluntarily provided foreign identity data |

|

South Australia |

Legislation not passed |

|

1 quarter reported with some voluntarily provided foreign identity data |

|

Northern Territory |

23 June 2017a |

|

Nil |

Note a: The legislation passed in the Northern Territory enables collection and reporting of all information not previously collected, except for the foreign identity data.

Note b: All jurisdictions except Northern Territory commenced property data reporting from 1 July 2016 using the legislated Real Property Transfers Report. Only New South Wales reported foreign identity data during 2016–17.

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.11 As illustrated in Table 2.1, as at February 2018 all states and the Australian Capital Territory were in a position to provide the expanded real property transfers reports.23 Real property transfers reports include the following information:

- property details, including land title information, property address and other descriptors;

- transactional information, including transfer price, contract date and settlement date;

- identity data of the purchaser/transferee and vendor/transferor, including:

- name, address and date of birth for individuals;

- name, address and Australian Business Number for non-individuals; and

- foreign identity details.24

2.12 Real property transfers reports include mandatory, optional and conditional fields. Optional fields must be completed by the intermediary25/reporting party if the data is available, and conditional fields become mandatory when the condition is met.

Accuracy of foreign identifier data in real property transfers reports

2.13 As shown in Table 2.2, foreign identifier information in the real property transfers reports are all optional fields.26 This may result in lower completion of fields27, but needs to be balanced with the time and cost involved across all property purchases in completing property transfer reports. Table 2.2 also shows the number of foreign identifier fields that had been completed in the New South Wales (NSW) property data from 1 July 2016 to 30 September 2017. NSW was the only jurisdiction that had collected foreign identifier data for that period.

Table 2.2: Reporting fields in New South Wales property data for foreign investment

|

Reporting data field |

Reporting requirement |

Number of completed fields in NSW property data |

|

Application number |

Optional |

888 |

|

Overseas entity registration number |

Optional |

74 |

|

Overseas entity identifier |

Optional |

547 |

|

Nationality or citizenship |

Optional |

29 183a |

|

Passport number |

Optional |

16 455a |

|

Visa number |

Optional |

9 220a |

Note a: There can be multiple owners for each property transaction, and permanent residents (exempt from gaining foreign investment approval) may declare nationality other than Australian, as well as provide passport and visa details.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO data.

2.14 The ANAO’s analysis identified 23 431 properties in the NSW data with at least one potential foreign identifier. This number is almost twice as high as the number of foreign investors who applied for residential real estate in NSW from 1 July 2015 to 13 December 2017 (12 278 as shown in Figure 2.2). The difference may reflect reporting of information in the foreign identifier fields by non-foreign investors (particularly for the nationality or citizenship and passport number fields). It may also reflect instances where foreign investors had purchased residential real estate without applying to do so.

2.15 The ANAO suggests that the ATO closely examines the accuracy of foreign identifier data in state and territory real property transfers reports and takes steps to make it more immediately useable for the purposes of the register of residential real estate. This may require substantial liaison with state and territory land titles offices to improve the accuracy of the foreign identifier data, including to ensure that it only includes foreign investors, and increased communication with intermediaries.

Self-registration of foreign ownership of residential real estate

2.16 The ATO advised that it had been relying on the information collected through the self-registration process as an interim measure until the states and territories were able to collect and report the complete new property data including foreign identifiers. The ATO further advised that the foreign identifier in the data from the states and territories is intended to match an existing FIRB application and should streamline the process of compiling the register.

2.17 Foreign investors submit information regarding their acquisitions through an online form on the ATO’s website. The online registration form was originally developed to register information on agricultural land holdings and the ATO designed the form to also collect residential real estate registrations from 1 July 2016.

2.18 The registration form provided on the ATO website has a range of information fields relating to: application information; contact details; ownership interest details; and land details. Of the 81 fields presented online, 36 were mandatory and 25 were conditional fields.

Extent of self-registration

2.19 The ANAO examined the extent of self-registration by comparing the number of self-registrations from 1 July 2016 to 17 December 2017 with the number of approvals for foreign investments in residential real estate from 1 July 2015 to 13 December 2017, shown in Table 2.3. The ANAO acknowledges uncertainty in this calculation relating to the selection of different time periods for approvals data (1 July 2015 to 13 December 2017) compared to self-registration data (1 July 2016 to 17 December 2017)28, and because application approvals represent proposed investment and not all foreign investment approvals result in a purchase.

Table 2.3: Proportion of the ATO’s self-registrations of approvals for foreign investments in residential real estate

|

Type of foreign investor |

Number of application approvalsa |

Number of self-registrationsb |

Percentage of self-registrations of application approvals |

|

Individual |

35 966 |

2 549 |

7.1 |

|

Company |

848 |

76 |

9.0 |

|

Trustee |

330 |

28 |

8.5 |

|

Total |

37 144 |

2 653 |

7.1 |

Note a: From 1 July 2015 to 13 December 2017.

Note b: From 1 July 2016 to 17 December 2017.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO data.

2.20 As shown in Table 2.3, self-registrations represented 7.1 per cent of all approvals over the period. While it is not known how many approvals have resulted in a purchase, and therefore what percentage would represent full registration, the 7.1 per cent recorded provides some basis for considering there may be significant non-registration by foreign investors in residential real estate.29 Accordingly, there would be merit in the ATO assessing the potential extent of non-registration and taking steps to improve the level of registration through education and other means (which could include simplifying the registration form to reduce a potential deterrent to self-registration).

2.21 The ATO advised in May 2018 that it had implemented strategies to increase the rate of self-registration, including through email prompter campaigns and visits to intermediaries. The ATO also advised that to mitigate risks to the integrity of the land register from under self-registration, it had conducted a comprehensive manual data matching exercise to identify property transfers that relate to a foreign investment approval.

Compiling the national residential land register

2.22 As illustrated in Figure 2.1, to compile the residential land register the ATO matches state and territory land titles data to foreign investment application data, and manually verifies the information submitted through the self-registration process with:

- application data sets to confirm compliance with approval conditions; and

- states and territories data to confirm the residential real estate purchase details.30

Figure 2.1: Residential land information compiled for the national land register

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.23 Of the 2653 self-registrations shown in Table 2.3, 2128 registrations (80.2 per cent) exactly matched the FIRB numbers in the application data, and 525 (19.8 per cent) did not have matched FIRB numbers.31 However, the extent of non-exact matches also highlights the need for considerable effort by the ATO to cleanse the data in compiling the register in coming years.

2.24 The ANAO extended the matching of FIRB numbers for self-registrations, foreign investment applications and NSW real property data only.32 This matching aimed to identify the number of foreign investors with approval who subsequently purchased a dwelling and also self-registered. The matching identified a small number and percentage of application numbers consistent across the three data sets, as illustrated in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Data matching of potential foreign investor properties

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

2.25 This analysis identified serious deficiencies in populating the register with reliable data, and further emphasises the importance of the ATO taking steps to improve the accuracy of data in real property transfers reports33, and also in self-registrations.

2.26 The ANAO also matched information other than the application number between the FIRB application data and NSW real property data. As shown in Table 2.4, the ANAO developed degrees of confidence by matching the following information:

- name of purchaser;

- passport number;

- address of purchaser; and

- address of property purchased.

2.27 Table 2.4 indicates that the number of high and medium confidence matches for NSW (51 and 122 or 113 respectively) represented a small proportion of the number of self registrations and applications (504 and 12 278 respectively from Figure 2.2), and there was considerable variation in the three types of low confidence matches for NSW.

Table 2.4: Potential matches of data from foreign investment applications with NSW real property data

|

Data matches |

Details |

NSW |

|

High confidence matches |

First name, middle name, family name, passport number, address of purchase and address of purchaser |

51 |

|

Medium confidence matches |

First name, middle name, family name, passport number and address of purchase |

122 |

|

First name, middle name, family name, address of purchase and address of purchaser |

113 |

|

|

Low confidence matches |

First name, middle name, family name and address of purchase |

339 |

|

First name, middle name, family name and address of purchaser |

747 |

|

|

First name, middle name, family name and passport number |

1 237 |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

2.28 In the context of the large number of properties purchased between 1 July 2016 and 30 September 2017 (427 946 properties for NSW), the ANAO’s testing revealed considerable levels of non-matches that will require manual verification by the ATO.

2.29 The ATO intended to provide an interim report on the register of foreign investment in residential real estate to Treasury in March 2018, however the report is yet to be prepared. The ATO aims to populate the register by December 2018 and prepare yearly reporting on the register once the states’ and territories’ information is standardised from 2019 onwards.34

3. Compliance strategies and voluntary compliance

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the ATO’s compliance strategies and voluntary compliance activities aimed at addressing non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate.

Conclusion

The ATO has assessed and addressed compliance risks in relation to foreign investment obligations for residential real estate but has not yet compiled and implemented a compliance and enforcement strategy. To promote voluntary compliance with those obligations, the ATO has developed a series of communication strategies. The strategies, which have largely been implemented, incorporate a multi-platform communication approach targeting key audiences with priority messages.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at the ATO developing a compliance and enforcement strategy in relation to residential foreign investment obligations (paragraph 3.13).

The ANAO made seven suggestions aimed at: improving the ATO’s assessment of risk control effectiveness (paragraph 3.3); improving the alignment between risk documentation and communication plans (paragraph 3.18); publishing residential foreign investment information in additional foreign languages (paragraph 3.21); improving the usability, and clarifying the status, of guidance notes (paragraphs 3.24 and 3.25); considering additional prompter campaigns (paragraph 3.29); including targets and qualitative indicators in future communication strategy evaluation plans (paragraph 3.38); and undertaking a formal evaluation of the entire foreign investment communication program (paragraph 3.41).

Does the ATO have an effective compliance and enforcement strategy in place?

The ATO does not have a compliance and enforcement strategy but has a reasonable basis for developing such a strategy, as it has undertaken a risk assessment of foreign investment in residential real estate and identified corresponding risk treatments. In preparing a compliance and enforcement strategy, the ATO should analyse compliance outcomes to inform targeted compliance approaches, address weaknesses in existing controls and incorporate measures of control effectiveness.

3.1 The ATO does not have a compliance and enforcement strategy but has a documented risk assessment for foreign investment in residential real estate and a corresponding risk treatment plan (both completed in December 2016).

Risk assessment of foreign investment in residential real estate

3.2 The ATO’s risk assessment of foreign investment in residential real estate outlines risk drivers35, as well as cultural influences and individuals’ psychological traits. It also identifies potential risk participants and the non-compliance risks associated with those participants, as outlined in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Potential non-compliance risks and participants for foreign investment in residential real estate

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO’s risk assessment of foreign investment in residential real estate.

3.3 The risk assessment also outlines the controls in place to prevent, detect and mitigate risks associated with foreign investment in residential real estate. The assessment was of the expected effectiveness of those controls, as there was lack of evidence to determine actual effectiveness. On this basis, the ATO identified and assessed ten controls as being effective or partially effective, as shown in Table 3.1. No controls were assessed as being ineffective.36 Going forward, the ATO’s risk assessments should incorporate an assessment of the demonstrated effectiveness of controls, and in doing so could include some of the measures outlined in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: The ATO’s assessment of risk controls for foreign investment in residential real estate, and rating of effectiveness

|

Control |

Control type and ATO assessment |

Reason for the ATO’s assessment |

The ANAO’s suggestions of measures that could inform the ATO’s assessment of the effectiveness of controls |

|

Foreign investment real estate helpline |

Preventative Partially effective |

Help line does not accommodate international time differences and does not offer immediate translation services |

|

|

Foreign investment self-disclosure |

Preventative Effective |

Amnesty period was available for self-disclosure from May to November 2015a |

|

|

Education and information |

Preventative Effective |

Activities undertaken to educate and inform stakeholders |

|

|

New penalty regime |

Preventative Effective |

New civil and increased criminal penalties should deter non-compliance |

|

|

Third party involvement in property transactions |

Preventative Partially effective |

Third parties provide control as most intermediaries will require evidence of approval from investors |

|

|

Legislative changes |

Preventative/ Mitigative Effective |

Changes to the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 and the introduction of the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Fees Imposition Act 2015 |

|

|

Reduced application processing times |

Preventative/ Mitigative Effective |

Investors will be unable to avoid foreign investment obligations due to time constraints in purchasing a property |

|

|

Community referral line |

Detective Effective |

Members of the public can report suspected non-compliance through the line that is easy to access and use |

|

|

Case selection (methods developed) |

Detective Partially effective |

Data matching is used to detect non-compliant behaviour |

|

|

Compliance activity |

Detective Effective |

Twenty-one per cent non-compliance rate confirmed among investigated cases (including residential, commercial and agriculture) |

|

Note a: The amnesty period included reduced penalties for foreign investors who voluntarily disclosed breaches of the foreign investment framework. The amnesty period was from 2 May 2015 to 30 November 2015 and had concluded prior to the dates of the risk assessment and risk treatment plan (December 2016).

Source: ATO risk assessment of foreign investment in residential real estate and ANAO analysis.

3.4 The ATO’s December 2016 risk assessment for foreign investment in residential real estate also identified four future controls, as shown in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: Future controls for foreign investment in residential real estate, and status as at January 2018

|

Future control |

Type of control |

Description of control |

ATO’s assessment of the status of controls as at January 2018 |

|

Case selection methods (under development) |

Detective |

Additional data matching rules (as outlined in Chapter 4) were being developed to identify different types of non-compliance for example, property purchases prior to approval. |

Six data matching rules have been implemented; two are under development; and two are yet to be developed.a |

|

Data systems, storage and collection |

Mitigative |

Recreating Treasury’s historical database.b Profiling land owners. |

Implemented. |

|

Registration of foreign persons leaving Australia |

Detective |

Identifying temporary residents using Department of Home Affairs and residential investment register data. |

Implemented. |

|

Compliance work focusing on structures |

Detective |

Dedicating an ATO officer to examine structures implemented to avoid Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 obligations. |

Implemented. |

Note a: Other information provided by the ATO indicated that of the 32 data matching rules, as at March 2018: 15 had been developed; eight were under development; six had not yet been started; two were considered redundant; and one remained under consideration (see Chapter 4).

Note b: The ATO advised that the database combines the foreign investment approvals completed by Treasury with the foreign investment approvals completed by the ATO.

Source: ATO risk assessment of foreign investment in residential real estate.

3.5 Overall, the ATO’s risk assessment was that the preventative controls were partially effective, while detective and mitigative controls were effective. The risk assessment noted a gap in the coverage of mitigative controls to be addressed by the implementation of the future controls (which have subsequently largely been implemented).

3.6 The ANAO considers that the ATO had overstated the effectiveness of the detective and mitigative controls as: detection activities had not addressed risks posed by intermediaries; and the ATO’s data matching program was at an early stage in addressing key compliance risks (as discussed in Chapter 4).

3.7 Strengthening the ATO’s risk assessment processes to be informed by evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of controls will provide greater confidence in the accuracy of assessments as well as assist to identify controls that need to be improved or introduced. The ATO advised the ANAO that while the assessment of effectiveness of controls was initially necessarily prospective in nature, subsequent risk assessments will incorporate evidence of the effectiveness of controls where practical.

Risk treatment plan

3.8 The risk treatment plan identifies treatments to address the non-compliance risks for foreign investment in residential real estate that were identified in the risk assessment, as illustrated in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: High-level treatments to address compliance risks for foreign investment in residential real estate

Note: NDEC is New Dwelling Exemption Certificate.

Source: ATO risk treatment plan for foreign investment in residential real estate.

3.9 Some of these high-level treatments are supported by lower-level treatments. For example, improving the knowledge of investors and intermediaries is supported by targeting specific audiences through relevant communication channels. For 11 of the 14 lower-level treatments, responsibility is assigned to ATO officers for implementation in a project plan attached to the treatment plan.37 As at April 2018, all treatments were being implemented, and had ‘ongoing’ listed as their due date.

Compliance and enforcement strategy

3.10 While the ATO has not compiled a compliance and enforcement strategy, the risk assessment and treatment plan provide a reasonable basis for developing one. The ATO advised the ANAO that it intends to update its risk assessment and treatment plans on an annual basis. Leveraging off this process, the ATO could prepare a compliance and enforcement strategy that reflects current compliance risks and intelligence, for example:

- analysing compliance outcomes to inform targeted compliance approaches including geographic areas to target or particular types of foreign investment (refer Chapter 4); and

- identifying key compliance messages to be communicated, such as legislative changes.

3.11 Developing a compliance and enforcement strategy that clearly links types of non-compliant behaviour with penalties and the ATO’s detection and investigation activities would assist the ATO to prioritise its activities to encourage compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate.

3.12 The ATO could also consider how to use elements of the strategy in activities to educate stakeholders of their obligations and the penalties for non-compliance. There is limited publicly available information about the ATO’s residential foreign investment compliance and enforcement approach, and where information is available, it is disseminated in some of the 50 guidance notes published on the Foreign Investment Review Board’s website.38 Thirty-seven of these guidance notes are relevant to residential foreign investment, of which:

- thirty indicate that penalties may apply to breaches of Australia’s foreign investment framework;

- one contains information in relation to an ATO investigation activity39;

- eleven provide examples of non-compliant behaviour and the relevant penalties; and

- ten provide examples of non-compliant behaviour but do not identify the relevant penalties.

Recommendation no.1

3.13 The Australian Taxation Office compiles and implements a residential foreign investment compliance and enforcement strategy, which draws on existing risk assessment and treatment documentation and information about the results of prior compliance activities.

Australian Taxation Office’s response: Agreed.

3.14 In addition to processes already underway to review existing risk assessment and treatment documentation for foreign investment in residential real estate, the ATO will compile a single compliance and enforcement document. In doing so, the ATO will look to draw from existing strategy and reporting documentation.

Are voluntary compliance activities effective and well-targeted?

The ATO’s information about foreign investment in residential real estate is comprehensive and readily accessible to foreign investors, stakeholders and the general public through the websites of the ATO and the Foreign Investment Review Board, which include information products in one language other than English (Chinese). There is also a residential foreign investment real estate help line and email inbox, avenues for community and stakeholder engagement, and use of social media. Activities are managed through an up-to-date communication strategy. There would be benefit in the ATO undertaking a broad evaluation of the residential foreign investment communication program to inform future communication strategies.

Communication strategies

3.15 The ATO developed a communication strategy in relation to foreign investment in September 2015 for the 2015–16 year, and has prepared a revised strategy for each subsequent financial year. The strategies cover foreign investment in both agriculture and residential real estate. The strategies outline communication approaches to target foreign investors and intermediaries through various channels, including social media, face-to-face educational opportunities, specialist channels to reach diverse audiences, and a foreign investment specific help line and email inbox.40 Key messages are revised to reflect communication priorities such as changes to legislation and foreign investors’ obligations.41

3.16 The ATO’s foreign investment communication strategies have matured over time, as demonstrated by the inclusion of improved implementation plans with status sections for recording progress, and evaluation plans that identify communication objectives (see paragraph 3.40). Over time, the number of communication activities has decreased, with 58 activities in the period July 2015 to July 2016, 13 activities in the period July 2016 to July 2017 and one activity from July 2017 to January 2018.

3.17 The 2017–18 communication strategy outlines a new program of communication activities, including articles and public relations activities, and social media posts, which focus on renewed messaging about the water register and the introduction of the vacancy charge. In its 2018–19 communication strategy, the ATO could consider increasing the number of communication activities (subject to the evaluation suggested in paragraph 3.41), as well as placing a greater emphasis on messages in relation to foreign investment obligations for residential real estate, including the residential land register42 to assist in improving data quality.

3.18 The communication strategies generally address compliance risks identified in the ATO’s foreign investment in residential real estate risk assessment and treatment plan (see paragraphs 3.2 to 3.11). As illustrated in Table 3.3, some areas of misalignment that the ATO could consider addressing include identifying the: ATO and Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) websites in the risk assessment or treatment plans; and key agent program43 in the communication strategy.

Table 3.3: Identification of communication activities in the ATO’s foreign investment in residential real estate risk assessment and risk treatment plans

|

|

Risk assessment – controls |

Risk treatment plan – treatments |

|

In communication strategies |

|

|

|

Social media |

Yes |

No |

|

ATO webpages |

No |

Noa |

|

Foreign Investment Review Board website |

No |

No |

|

Foreign Investment Review Board helpline |

Yes |

No |

|

Foreign Investment Review Board mailbox |

No |

Yes |

|

Foreign Investment Reforms Working Group |

Nob |

Yes |

|

Established ATO channels (business bulletins, tax professional newsroom and small business newsroom) |

No |

Yes |

|

Face-to-face educational activities (including seminars and information booths) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Media articles and public relations |

No |

Yes |

|

Communication via community/specific audience channels (e.g. Chinese community TV and Multicultural NSW mailing list) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Prompter campaigns |

No |

Yes |

|

Not in communication strategies |

|

|

|

Key agent program |

Yes |

Yes |

Note a: Activity mentioned as a data source, not a treatment.

Note b: Activity mentioned in the risk event, not as a control.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO communication strategies, risk assessment and treatment plans for foreign investment in residential real estate.

3.19 The activities outlined in the 2015–16 and 2016–17 communication strategies have been implemented, except for the prompter campaigns that were partly implemented (see paragraphs 3.28 to 3.29). The 2017–18 communication strategy was being implemented at the time of audit fieldwork.

Online guidance

The ATO’s website

3.20 The ATO’s website has webpages to inform foreign investors of their obligations under the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975, including a page specifically relating to residential foreign investment.44 These pages include information on foreign investors’ obligations before and after investment as well as in relation to breaches and changes of circumstances.

3.21 The ATO’s webpages in relation to foreign investors are readily accessible, and though containing limited detail, link to the more comprehensive information available on the Foreign Investment Review Board’s website. The ATO’s website also includes links to fact sheets in traditional and simplified Chinese (as investors from Chinese speaking countries comprise 65 per cent of residential foreign investment applications and 54 per cent of breaches). There is an opportunity to publish material in other languages for the benefit of investors who reflect a significant proportion of the foreign investment application population. For example, as at January 2018, six per cent of breaches were committed by Malaysian investors and three per cent of breaches were committed by Indonesian investors.

3.22 The ATO’s website also includes webpages dedicated to legislative, corporate and administrative tax news. These webpages were used to distribute information during 2015 and early 2016 on the foreign investment obligations, and are primarily aimed at educating intermediaries.45 The ATO has not used these webpages to distribute foreign investment information since early 2016. The ATO should consider using these webpages to disseminate new information such as changes to legislation, particularly as they focus on targeting intermediaries and are the primary way of addressing the risk of intermediaries assisting in breaches according to the ATO’s risk treatment plan for foreign investment in residential real estate.

Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) website hosted by Treasury

3.23 Most information about residential foreign investment obligations is available on the Foreign Investment Review Board website.46 The guidance notes available on the website provide a significant amount of information on a range of topics relevant to residential and other areas of foreign investment. For example, the guidance notes include information on the legislative obligations of foreign investors, application fees, penalties, definitions and exemptions.47

3.24 Treasury is responsible for drafting guidance notes and since May 2015 the number of notes increased from five to over 50. The guidance notes are accessible and consistent. However, they would benefit from embedded hyperlinks to allow readers to quickly access other relevant documents and guidance notes, and it would be worthwhile for Treasury to consider either having an interactive flow chart for investors to determine what rules apply to them, or otherwise clustering the guidance notes into categories (for example, buying an established dwelling) to improve access to related information.

3.25 While guidance notes define how the legislation will work in most circumstances, the ATO and Treasury are not bound by them. There is a risk that the intended audience (both foreign investors and ATO staff) will perceive these as strict representations of the law. The ATO and Treasury should consider whether the status of these notes solely as guidance should be made clearer.

Social media and other campaigns

Social media

3.26 As illustrated in Figure 3.3, the ATO has used social media platforms to communicate key messages relating to foreign investment obligations, including for residential real estate. The messages included the introduction of new obligations, fees and penalties for foreign investors in residential real estate. From July 2015 to July 2016, the ATO made 16 tweets, 15 LinkedIn notifications, three Facebook posts and a YouTube video relating to foreign investment obligations. The ATO estimated that collectively these 35 posts reached more than 170 000 people.

Figure 3.3: Content of the ATO’s foreign investment-related social media posts

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documentation.

3.27 Since July 2016, the ATO has made no social media posts in relation to residential foreign investment obligations. The ATO advised that it would consider reinvigorating its social media presence in relation to foreign investment obligations for residential real estate.

Prompter campaigns

3.28 The ATO identified three types of prompter campaigns48 in its risk treatment plan for foreign investment in residential real estate, and had commenced two of those by April 2018:

- notifying foreign investors who owned vacant properties of their obligations; and

- targeting investors who had acquired a property prior to seeking approval, requiring them to provide evidence to the contrary otherwise an infringement notice would be issued. A pilot conducted in early 2016 resulted in a 50 per cent infringement rate.49

3.29 As prompter campaigns can be an effective method of encouraging voluntary compliance, the ATO should continue to consider this approach to address other compliance risks, such as the use of properties subject to redevelopment conditions.

Community and stakeholder engagement

Activities

3.30 Since July 2015, the ATO has conducted engagement activities to communicate to foreign investors their foreign investment compliance obligations.

3.31 The ATO conducted an Understanding your Australian Taxation Obligations and Foreign Investment in Australia program between October 2015 and June 2016. The program was co-designed with industry representatives, and aimed to present information to taxpayers and professionals to assist them to comply with their foreign investment and tax obligations.50 It included nine community engagement events, in English and Chinese, which reached 1750 people.

3.32 The ATO also conducted a range of education sessions, seminars, presentations and webinars primarily aimed at intermediaries from 2015 to 2017. Audiences for these activities included solicitors, real estate agents and other government entities. Topics covered in these sessions included application fees, the land register and the ATO’s compliance function.51 The ATO also set up information booths at events such as the Australian Business Forum.

Foreign Investment Reforms Working Group

3.33 The Foreign Investment Reforms Working Group was formed in July 2015 to develop and maintain ongoing relationships between relevant business and industry representatives and the ATO.52 Currently the group meets quarterly, having met monthly from July 2015 to mid-2016. The working group was initially scheduled to cease in November 2016 but was extended at the request of the participants. The minutes of the working group are published on the ATO’s website.

Residential foreign investment real estate help line and email inbox

3.34 The residential foreign investment real estate help line is a dedicated phone service for foreign investors, intermediaries and the general public to enquire about matters related to foreign investment in residential real estate. The help line is available from 8am to 6pm Monday to Friday, and there is also a residential foreign investment enquiries email address available to the public to submit queries.

3.35 Usage data from the phone service and email inbox are reported in monthly project status reports.53 The ATO received approximately 400 calls per week in June 2017 and approximately 30 call centre escalations per week.54 Email enquiries totalled around 80 per week for the period. Response timeframes are in place; however, adherence to these is not regularly monitored and reported.55

Measuring the effectiveness of communication activities

3.36 The communication strategies outline an approach for measuring the effectiveness of communication activities, including reporting on letters sent, articles published, media articles generated, web analytics, webinar or roadshow feedback.

3.37 As illustrated in Table 3.4, the ATO’s approach to measuring the effectiveness of communication activities has matured. The ATO’s approach outlined in its 2017–18 plan includes communication objectives, deliverables and metrics. However, the metrics could be improved as they do not:

- identify targets or benchmarks to measure against; or

- specify qualitative indicators of success, such as whether foreign investors know where to go for assistance, and intermediaries are engaged and well-informed regarding residential real estate ownership for foreign investors.

3.38 In future communication plans, the ATO could include targets and benchmarks to measure improvement, and identify qualitative indicators that reflect the underlying intent of the communication activity.

Table 3.4: Evaluation objectives and data sources of communication activities

|

Year |

Objectives |

Data sources/communication metric |

|

2015 |

Not identified |

Reporting on the number of letters sent Publishing of articles Number of media enquiries Number of media articles generated Web analytics (such as page views and page hits) Responses/registrations by entities to direct mail-out Number of reduced penalty period disclosures, registrations on the land registrations Feedback from the Foreign Investment Reforms Working Group Stakeholder community engagement undertaken Reviewing and analysing call centre statistics |

|

2016 |

Not identified |

General reporting as outlined in the Marketing and Communication metrics data guide. Coverage and reach only Measure news and social media coverage and impact, including coverage, reach and sentiment |

|

2017 |

Support the ongoing uptake of registrations to the water register of foreign ownership |

Visitors to ato.gov.au Media monitoring Visitors to Tax professionals newsroom article Social media Publication of articles through PR approach Webinar/Roadshow anecdotal feedback (if any) Media monitoring - internal |

|

Support the introduction of new measures arising from the 2017 Federal Budget (vacancy charge) |

||

|

Refresh awareness of the overarching Foreign Investment Program, including agricultural and residential land, applications etc |

||

|

Ensure effective ongoing communications with foreign investors and their representatives so they are aware of the laws and their obligations. |

||

|

Internal communication activities to ensure ATO staff are aware of the Foreign Investment Program, the laws and what they mean for clients, and any impacts on their work |

||

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documentation.

3.39 The ATO has prepared communication reports on a monthly basis since August 2016.56 These reports include the results of those data sources outlined in Table 3.4 that have been undertaken.

3.40 The ATO evaluated one component of the communications approach in the form of a closure report for the Understanding your Australian Taxation Obligations and Foreign Investment in Australia sessions (see paragraph 3.31). The evaluation outlined effectiveness measures and identified information sources to inform measures.57 In addition, the ATO mapped the behavioural impact of communication messages.

3.41 The ATO would benefit from undertaking a broader evaluation of the residential foreign investment communication program. In particular, it could assess the comparative effectiveness of activities including measuring the behavioural impact of messages. Such an assessment would enable a more informed approach for future communication strategies.

4. Detection and investigation

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the effectiveness of the ATO’s detection and investigation activities aimed at addressing non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate.

Conclusion

The ATO has undertaken a significant amount of work to develop processes and systems to support the detection and investigation of non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate. There are a number of minor enhancements the ATO could make to improve its largely effective investigation processes, with more substantial work required in its development of processes to actively detect non-compliance.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at the ATO developing and finalising data matching rules that address key compliance risks (paragraph 4.13). The ANAO also made five suggestions aimed at the ATO: aligning its case prioritisation framework with investigation outcomes (paragraph 4.21); introducing greater scrutiny of timeliness for compliance teams (paragraph 4.42); improving guidance available to assist compliance teams (paragraphs 4.36 and 4.44); recording recipients on the information gathering notice register (paragraph 4.47); and implementing an additional mechanism to review compliance team decisions (paragraph 4.49).

Are effective processes in place to detect non-compliance?

The ATO has partially effective processes to detect non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate. It detected some 4300 cases of potential non-compliance from mid-2015 when it gained responsibility for compliance through January 2018, mainly from community or self-referrals or through approval processes for foreign investors. While the ATO has established a data matching program to actively detect non-compliance, as at April 2018 the program had not addressed all identified key compliance risks and more work was required to mature its processes for actively detecting non-compliance.

Information sources used to detect potential non-compliance

4.1 The ATO receives information relating to potential non-compliance through a number of sources, as shown in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1: Information sources for detecting non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate

|

Source of information |

Description of source |

|

Self-disclosure |

People who notify the ATO that they have breached the foreign investment framework. Notifications can be made through a form available on the Foreign Investment Review Board’s websitea or emailed directly to the ATO. |

|

Community referral |

The public can report suspected breaches of the foreign investment framework through a form available on the Foreign Investment Review Board’s website.b |

|

Other referral |

Referrals from internal and external sources such as other ATO business lines, the media and local, state and Australian Government departments. |

|

Screening infringement |

Foreign investors identified through the foreign investment application process who indicate they have entered into unconditional contracts to purchase a dwelling prior to seeking approval. |

|

Breach monitoring |

The ATO’s monitoring of people that have been provided the opportunity to remediate a breach of foreign investment obligations. |

|

Data matching |

The ATO’s data matching program, which uses data from other Australian Government entities, state government entities and the private sector. |

Note a: Foreign Investment Review Board, Self-disclosure form – residential real estate [Internet], Foreign Investment Review Board, 2018, available from <http://compliance.firb.gov.au/self-disclosure/> [accessed 28 February 2018].

Note b: Foreign Investment Review Board, Reporting a breach of the foreign investment rules [Internet], Foreign Investment Review Board, 2018, available from<https://compliance.firb.gov.au/compliance-reporting/> [accessed 28 February 2018].

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

4.2 From May 2015 through January 2018, the ATO reported receiving 4258 cases of potential non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate, as indicated in Table 4.2. Of these, 3940 had been investigated and closed, with 318 cases remaining open and being investigated as at 31 January 2018.

Table 4.2: Number of total cases of potential non-compliance with foreign investment obligations for residential real estate per investor, by source of information, May 2015 through January 2018

|

Source of information |

New cases received |

Closed cases |

Cases remaining open |

|

Self-disclosure |

590 |

550 |

40 |

|

Community referral |

1586 |

1557 |

29 |

|

Other referral |

229 |

215 |

14 |

|

Screening infringement |

1007 |

874 |

133 |

|

Breach monitoring |

120 |

102 |

18 |

|

Data matching |

726 |

642 |

84 |

|

Total |

4258 |

3940 |

318 |

Source: ATO information.