Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Child Support Collection Arrangements between the Australian Taxation Office and the Department of Human Services

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the child support collection arrangements between the Department of Human Services (DHS) and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Child Support Scheme is governed by the Child Support (Registration and Collection) Act 1988 and the Child Support (Assessment) Act 1989, and administered through the Department of Human Services (DHS). The scheme requires parents who do not have primary care of their children to make financial contributions to their children’s upbringing. In 2015–16, a total of $3.5 billion was transferred in child support payments, supporting approximately 1.2 million children.1

2. Parents in the Child Support Scheme undertake an initial child support payment assessment, followed by periodic reassessments. Child support payment assessments are made using a formula that takes into account a range of factors including: each parent’s income; the percentage of care each parent provides; and the cost of raising children.2 Following an assessment, DHS determines a child support liability for the paying parent.

3. DHS has arrangements in place with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) to help facilitate accurate assessment of Child Support Scheme parents’ income, as well as the collection of child support debts. To support the accurate assessment of child support parents’ incomes and child support payments, the ATO takes actions to promote the timely lodgment of tax returns by child support customers.3 To support the collection of child support debts, the ATO intercepts tax refunds of parents owing child support amounts, and exchanges income information with DHS. These arrangements are governed under a Head Agreement4, and subsidiary service agreements for the Lodgment Enforcement Program5 and the Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs.6

4. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the child support collection arrangements between the Department of Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following criteria:

- arrangements are in place between DHS and the ATO in support of accurate and timely child support payments;

- DHS and the ATO fulfil their agreed responsibilities in support of accurate and timely child support payments; and

- DHS and the ATO measure the performance of their cooperative child support collection activities and transparently report on outcomes.

Conclusion

5. Child support collection arrangements between the Department of Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office are based on well-established administrative processes in each agency, but there is scope to improve important aspects of these arrangements.

6. The administrative framework in place to support the implementation of the child support collection arrangements between DHS and the ATO is sound. Agreements outline the roles and responsibilities of each agency, which have been fulfilled in almost all instances. While funding amounts specified in the previous Lodgment Enforcement Agreements were based on historical costs, it was unclear how the lodgment targets had been set. There is also some scope to improve supporting administrative arrangements, including shared risk management practices and referrals of child support customers suspected of fraud and tax evasion.

7. The vast majority of tax refunds are intercepted under the Tax Refund Intercept Program. Under the Lodgment Enforcement Program, DHS and the ATO can improve the prioritisation and targeting of customers by better considering other child support compliance risks. DHS can also improve its monitoring of the application of income information received from the ATO to inform program design.

8. DHS and the ATO have effective processes in place to manage complaints associated with the Lodgment Enforcement Program. Assurance reviews for some key program processes and program improvement mechanisms are not in place to support the cooperative child support programs.

9. The performance measures applied by DHS and the ATO for the cooperative child support programs do not accurately reflect the effectiveness of the programs. In accordance with the requirements under the Lodgment Enforcement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreements, there is transparent periodic inter-agency and internal reporting of the results. However, DHS’ and the ATO’s public reporting does not include Lodgment Enforcement Program results.

Supporting findings

Program administration

10. The Lodgment Enforcement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreements support the administration of the cooperative child support programs. The agreements clearly specify the objectives and articulate the roles and responsibilities that have been fulfilled in almost all instances by DHS and the ATO.

11. The current Lodgment Enforcement Agreement was the first not to specify a lodgment target and funding amount. The basis for the target in the initial agreement and revisions in subsequent agreements is unclear. Funding under the previous agreements was based on an estimate of staff costs at the time of the initial agreement, which was not reviewed or adjusted in subsequent agreements. The key terms of the Tax Refund Intercept Agreement, including the nature and extent of data exchange, were determined on a sound basis.

12. Arrangements outlined in the Lodgment Enforcement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreements support the accurate, complete and timely transfer of data between DHS and the ATO. There is scope to improve ad hoc customer referral processes between DHS and the ATO for investigation purposes.

13. The Lodgment Enforcement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreements do not specify risk management obligations between DHS and the ATO. However, DHS and the ATO advised that the proposed new agreements for the Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs will include risk management provisions. DHS and the ATO need to strengthen risk management practices for their collaborative child support collection arrangements, in particular the management of shared risks.

Program implementation

14. The selection of customers for compliance activities under the Lodgment Enforcement Program can be better targeted by considering risks such as compliance history, lifestyle factors, employment type and industry. DHS and the ATO do not strategically employ broader compliance activities to target customers subject to the Lodgment Enforcement Program. Further, the level of program activity undertaken by the ATO has declined markedly with the cessation of DHS funding in 2015–16, and more than half of the program results are of limited benefit to DHS.

15. The Tax Refund Intercept Program maximises child support collections as virtually all available refunds are intercepted. However, there are opportunities to increase child support collections under the Lodgment Enforcement Program by the ATO achieving a higher proportion of meaningful outcomes, such as tax return lodgments and default assessments. To inform program design, DHS should analyse the extent to which ATO-assessed taxable incomes are applied to child support payment assessments.

Complaint, assurance and improvement mechanisms

16. DHS and the ATO receive a small number of complaints in relation to the Tax Refund Intercept Program. Most complaints are not upheld and are effectively managed within prescribed timeframes. Complaints are not systematically reviewed to improve the cooperative child support programs.

17. DHS and the ATO do not have effective procedures in place at some key program points to assure the accuracy of data exchange and child support debt collection activities. In particular, DHS and the ATO do not explicitly or routinely test the accuracy of: customers’ reported incomes; amounts intercepted from tax refunds; or customers’ exclusion from the Lodgment Enforcement Program.

18. Some of the potential program improvements identified by DHS and the ATO have been implemented, while others have not. Program outcomes could be improved by applying continuous improvement mechanisms, for example one that categorises proposed changes according to potential impact, to assist DHS and the ATO to prioritise and implement identified program enhancements.

Performance measurement and reporting

19. There are shortcomings in the measures used by DHS and the ATO to monitor the performance of the cooperative child support programs. Both agencies use the number of income tax period finalisations as the performance measure for the Lodgment Enforcement Program. However, finalisations do not measure the objective of the program which is to achieve more accurate child support payment assessments and to maximise debt collection opportunities. Performance of the Tax Refund Intercept Program is measured by the number and value of tax refunds intercepted, and could be strengthened by implementing measures for the effectiveness of the program’s administration. DHS does not monitor the impact of the Information Exchange Program.

20. DHS and the ATO have fulfilled their periodic inter-agency and internal reporting obligations as required under the respective agreements. With respect to external reporting, DHS has reported on program outcomes in its annual reports, however, in 2015–16 no performance information in relation to the Lodgment Enforcement Program was publicly reported.

Recommendations

Recommendation No. 1

Paragraph 2.40

The Department of Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office implement arrangements to manage shared risks in administering the Lodgment Enforcement, Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

Australian Taxation Office’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation No. 2

Paragraph 3.14

The Department of Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office:

- prioritise customers under the Lodgment Enforcement Program according to the most relevant child support compliance risk factors; and

- strategically employ broader compliance activities to target child support customers.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

Australian Taxation Office’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation No. 3

Paragraph 3.39

To inform program design, the Department of Human Services examines the application of income information received from the Australian Taxation Office to child support payment assessments, to gauge the extent to which the information is being applied and reasons for it not being applied.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

Recommendation No. 4

Paragraph 4.22

The Department of Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office:

- identify and implement assurance mechanisms at key points of the Lodgment Enforcement, Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs to support the accuracy of child support payment assessments and the timely collection of child support; and

- establish a continuous improvement mechanism that assists with prioritising and implementing identified program improvements.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

Australian Taxation Office’s response: Agreed.

Recommendation No. 5

Paragraph 5.8

The Department of Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office improve performance measures under the Lodgment Enforcement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreements to demonstrate the effectiveness of child support collection activities.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

Australian Taxation Office’s response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

21. The Department of Human Services’ and the Australian Taxation Office’s summary responses to the report are provided below, with the full responses at Appendix 1.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (the department) welcomes this report, and considers that implementation of its recommendations will enhance child support collection arrangements between the department and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

The department notes the ANAO has concluded that child support collection arrangements between the department and the ATO are based on well-established administrative processes in each agency. In particular, the report notes that:

- 99.96 per cent of all available Tax Refund Intercepts were successfully intercepted during 2015–16;

- both agencies have effective processes in place to manage the very small number of complaints received in regard to the cooperative collection arrangement, with only 10.3 per cent being upheld and over 90 per cent effectively managed within the prescribed 10 working day timeframe; and

- the arrangements outlined in the agreements support the accurate, complete and timely transfer of data between the two agencies.

The department agrees with all five recommendations made by the ANAO.

Australian Taxation Office

The ATO welcomes the ANAO’s review and is committed to continuing to work closely with DHS to ensure that separated parents are assessed to financially support their children according to their taxable income.

The ANAO’s review recognises the lengthy partnership between the ATO and DHS, and that both agencies have a strong relationship and generally effective processes.

However, in finding the ATO’s involvement in the mutual programs mainly effective, the review identified four opportunities for change and improvement by the ATO.

The ATO agrees with these recommendations without reservation as they largely embody ongoing performance improvement, strengthened governance and improved client outcomes.

1. Background

Child support in Australia

1.1 The Child Support Scheme was introduced in 1988 to address the inadequacy of existing court-ordered child maintenance and payment collection arrangements.7 The scheme requires parents who do not have primary care of their children to make financial contributions to their children’s upbringing.

1.2 The Child Support Scheme is governed by the Child Support (Registration and Collection) Act 1988 and the Child Support (Assessment) Act 1989, and administered through the Department of Human Services (DHS). In 2015–16 there was a total of $3.5 billion transferred in child support payments, supporting approximately 1.2 million children.8

1.3 Either parent may elect to enter into a formal child support arrangement with DHS. Parents in the Child Support Scheme undertake an initial child support payment assessment, followed by periodic reassessments. Child support payment assessments are made using a formula that takes into account a range of factors including: each parent’s income; the percentage of care each parent provides; and the cost of raising children.9 Following a payment assessment, DHS determines a child support liability for the paying parent.

1.4 Child support payments can be transferred between parents under private arrangements, or payments can be facilitated by DHS. Under private arrangements, known as Private Collect, parents transfer child support payments directly without the assistance of DHS. Private Collect represented 52.6 per cent of child support cases in 2015–16, and DHS assumes a 100 per cent collection rate for these customers. Under a Child Support Collect arrangement, DHS collects and transfers child support payments on behalf of the non-paying parent (payee). In 2015–16, DHS collected and transferred $1.5 billion under Child Support Collect arrangements that covered 1.4 million parents.10

1.5 Parents who fail to meet their child support obligations under Child Support Collect arrangements accrue a child support debt.11 As of June 2016, 23.7 per cent of all active payers had an outstanding child support debt, and total outstanding child support debt was $1.5 billion.12 DHS employs a range of compliance actions to recover this debt, including income garnishee, prosecution, litigation, departure prohibition orders and collection arrangements with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

Arrangements between the Department of Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office

1.6 DHS has arrangements in place with the ATO to help facilitate accurate assessment of Child Support Scheme parents’ incomes, as well as the collection of child support debts. To support accurate assessment of child support parents’ incomes, and child support payments, the ATO takes actions to promote the timely lodgment of tax returns by child support customers and exchanges income information with DHS.13 To support the collection of child support debts, the ATO intercepts tax refunds of parents owing child support amounts.

1.7 Current arrangements between both agencies are governed under a Head Agreement14, and subsidiary service agreements for the Lodgment Enforcement Program, the Tax Refund Intercept Program and the Information Exchange Program.

Lodgment Enforcement Program

1.8 The child support formula relies on customers’ ATO-assessed taxable incomes to calculate child support payment assessments. This requires timely and accurate lodgment of income tax returns from child support customers. In instances where child support customers do not lodge income tax returns, DHS is able to use income estimates or previous assessed taxable income information subject to appropriate indexation to derive a child support payment assessment.15

1.9 Under the child support legislation16, child support payment assessments must be based on an ATO assessed taxable income17, therefore all child support customers are required to lodge a tax return.18 To this end, the Commissioner of Taxation publishes a legislative instrument each year specifying the requirement for child support customers to lodge a tax return. However, in this instrument, the Commissioner exempts those customers who have received certain welfare benefits totalling less than an annual threshold amount.19 This exemption results in a legislative misalignment where customers who are required to lodge for child support purposes are not required to lodge for taxation purposes.

1.10 In order to obtain tax return lodgment from child support customers, in 2006 DHS entered into an agreement with the ATO to enforce the timely lodgment of tax returns by child support customers. The ATO was provided annual funding by DHS of $6.9 million exclusive of goods and services tax (GST) for the Lodgment Enforcement Program up to 2014–15 when a Government decision discontinued funding arrangements.20

1.11 Under the Lodgment Enforcement Program, DHS sends a prioritised list of child support customers to the ATO for lodgment enforcement activity.21 The ATO refines the customer list referred by DHS22 and employs measures to obtain lodgment from prioritised child support customers including written correspondence, telephony work, penalties, prosecution and default assessments.23

Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs

1.12 The Tax Refund Intercept Program is an arrangement between DHS and the ATO that allows DHS to garnishee potential tax refunds of customers with child support debts. Under the arrangement, DHS provides the ATO with a list of child support customers and requests the ATO to notify DHS when these customers lodge income tax returns or have potential tax refunds available.

1.13 If a child support debtor lodges a tax return and is eligible for a tax refund, DHS may request the ATO to withhold and transfer that refund to DHS so that it can offset that customer’s child support debt. In instances where a potential refund exceeds the amount a customer owes, DHS will request only the outstanding debt amount from that customer’s refund.24

1.14 Under the Information Exchange Program, the ATO advises DHS of any new income information for the customer, allowing DHS to update its income data used for child support payment assessments. Beyond this information exchange, the Tax Refund Intercept Agreement has measures in place to allow DHS officers to access ATO customer information on an as-needs basis for the purposes of accurate and timely child support payments.

Programs’ impact

1.15 These programs25 support the operation of the Child Support Scheme by helping to ensure that child support payment assessments are calculated using accurate income information and contributing to the collection of child support payments. The value of child support debt collected through the Lodgment Enforcement and Tax Refund Intercept Programs in 2015–16 was $114.6 million or 7.6 per cent of the total value of outstanding child support debt in 2015–16 ($1.5 billion). As illustrated in Table 1.1, the amount of child support debt collected under the Lodgment Enforcement Program declined in the last three years.

Table 1.1: Lodgment Enforcement, Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs’ results

|

|

Lodgment Enforcement Program |

Tax Refund Intercept Program |

Information Exchange Program |

||

|

Financial year |

No. of finalisationsa |

Amount of debt collected |

No. of refunds intercepted |

Amount of debt collected |

No. of incomes exchanged |

|

2013–14 |

177 034 |

$33.9 m |

87 845 |

$96.5 m |

1 224 098 |

|

2014–15 |

236 436 |

$27.4 m |

83 830 |

$94.1 m |

1 247 255 |

|

2015–16 |

130 248 |

$16.9 m |

85 302 |

$97.6 m |

1 224 213 |

Note a: The ATO defines a ‘finalisation’ for an income tax period as one of the following: a lodgment received; a ‘return not necessary’ determination26; a ‘further returns not necessary’ determination27; or a default assessment issued.

Source: ANAO analysis of DHS and ATO information.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.16 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the child support collection arrangements between the Department of Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office.

1.17 To form a conclusion on the audit objective the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- arrangements are in place between DHS and the ATO in support of accurate and timely child support payments;

- DHS and the ATO fulfil their agreed responsibilities in support of accurate and timely child support payments; and

- DHS and the ATO measure the performance of their cooperative child support collection activities and transparently report on outcomes.

1.18 The audit addressed a recommendation arising from the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs’ inquiry report, From Conflict to Cooperation: Inquiry into the Child Support Program (2015). The Committee recommended the ANAO conduct a performance audit of the Lodgment Enforcement Program.

1.19 The audit also examined cooperation between DHS and the ATO for child support collection activities including tax refund intercepts and information exchange. The audit did not examine broader child support payment assessment and compliance strategies.

Audit methodology

1.20 The major audit tasks included:

- reviewing relevant DHS and ATO documentation, procedures and reporting;

- analysing data including information held by DHS and the ATO, and data exchanged between the two agencies;

- interviewing relevant agency staff and child support stakeholders; and

- reviewing citizen contributions received through the ANAO’s website.28

1.21 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $445 000.

1.22 The team members for this audit were Kylie Jackson, Esther Barnes, Haydn Thurlow and Andrew Morris.

2. Program administration

Areas examined

This chapter examines the administration and risk management arrangements that DHS and the ATO have in place for the cooperative child support programs.

Conclusion

The administrative framework in place to support the implementation of the child support collection arrangements between DHS and the ATO is sound. Agreements outline the roles and responsibilities of each agency, which have been fulfilled in almost all instances. While funding amounts specified in the previous Lodgment Enforcement Agreements were based on historical costs, it was unclear how the lodgment targets had been set. There is also some scope to improve supporting administrative arrangements, including shared risk management practices and referrals of child support customers suspected of fraud and tax evasion.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at improving the risk management arrangements for the cooperative child support programs (paragraph 2.40).

The ANAO also made two suggestions aimed at: reviewing the finalisation target set for the Lodgment Enforcement Program (paragraph 2.13) and improving responses to referrals of customers suspected of fraud and tax evasion (paragraph 2.25 to 2.27).

Are agreements in place to support the administration of the cooperative child support programs?

The Lodgment Enforcement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreements support the administration of the cooperative child support programs. The agreements clearly specify the objectives and articulate the roles and responsibilities that have been fulfilled in almost all instances by DHS and the ATO.

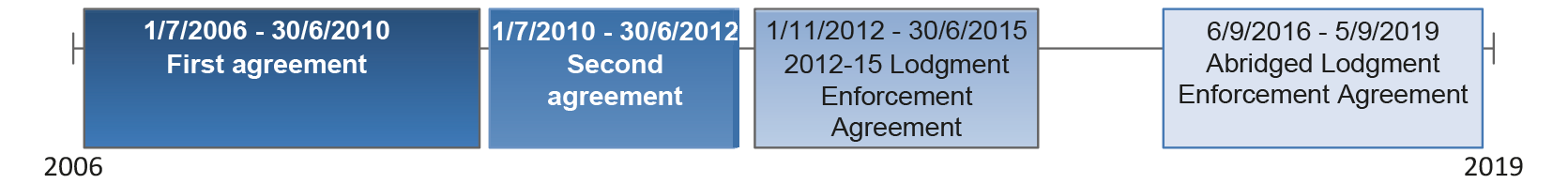

2.1 DHS and the ATO entered into an agreement in July 2006 to expand the Lodgment Enforcement Program.29 The Lodgment Enforcement Agreement has been renewed three times since 2006, as illustrated in Figure 2.1. This audit focused on the lodgment enforcement arrangements pertaining to the previous agreement (2012–15 Lodgment Enforcement Agreement) and the current abridged agreement (the Abridged Lodgment Enforcement Agreement).30

Figure 2.1: Timeline of Lodgment Enforcement Agreements

Note: The second agreement expired on 30 June 2011 but was further extended until 30 June 2012. The 2012–15 Lodgment Enforcement Agreement expired on 30 June 2014 but was extended until 30 June 2015.

Source: ANAO analysis of the Lodgment Enforcement Agreements.

2.2 The tax refund intercept and information exchange arrangements are outlined in the Subsidiary Arrangement—Tax Garnishee Arrangements and Access to ATO Information agreement (the Tax Refund Intercept Agreement) which DHS and the ATO entered into in November 2011. At the time of the ANAO’s audit fieldwork, DHS and the ATO were in the process of negotiating new agreements for the tax refund intercept and information exchange arrangements.31

Objectives

2.3 The Lodgment Enforcement Agreement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreement clearly specify the objectives of the child support collection arrangements between DHS and the ATO. Figure 2.2 illustrates the objectives of the arrangements under the two agreements.

Figure 2.2: Objectives of the Lodgment Enforcement Agreement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreement

Source: Lodgment Enforcement Agreement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreement.

Roles and responsibilities

2.4 The 2012–15 and Abridged Lodgment Enforcement Agreements clearly articulate the roles and responsibilities of DHS and the ATO. Table 2.1 illustrates that DHS and the ATO have fulfilled their agreed roles and responsibilities under the agreements.

Table 2.1: Fulfilment of roles and responsibilities for Lodgment Enforcement Agreements

|

Roles and responsibilities |

DHS |

ATO |

|

2012–15 Lodgment Enforcement Agreement |

||

|

Provision of all documentation, guidelines, rules, prescribed forms and scripts necessary for the ATO to perform the services. |

✔ |

Not applicable |

|

Provision of all information and data necessary for the ATO to perform the services, in the format reasonably requested by the ATO. |

✔ |

Not applicable |

|

Prompt provision of policy advice, legal advice or guidance following a request from DHS. |

Not applicable |

✔ |

|

Development of instruments or delegated legislation required for the implementation or performance of the program. |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Obtaining all Financial Management Act approvals, authorisations and drawing rights, and any other financial delegations and requirements, which either agency is required to obtain in order to perform the services. |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Abridged Lodgment Enforcement Agreement |

||

|

Provision of data within the agreed timeframes and request for updated data within a reasonable timeframe in the method specified. |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Assessment of the suitability of the information exchange and immediate notification to the other party if the data is no longer suitable or required. |

✔ |

✔ |

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2012–15 and Abridged Lodgment Enforcement Agreements.

2.5 While the Tax Refund Intercept Agreement does not have a clause that explicitly specifies the roles and responsibilities of DHS and the ATO, the agreement does indicate each agency’s roles and responsibilities. The ANAO extracted the key roles and responsibilities under the agreement and analysed whether they have been fulfilled, as illustrated in Table 2.2. The only responsibility that had not been met was DHS’ assessment of the suitability of ATO information provided for the purposes of carrying out the Child Support Registrar’s functions. In this regard, DHS had considered the adequacy of some information exchanged under the Lodgment Enforcement Program, but had not considered the relevance of information provided on a weekly basis by the ATO in 19 large, separate files. While DHS advised the ANAO that it used information held within these files for compliance activities, it could not advise which information it used.

Table 2.2: Fulfilment of key roles and responsibilities for Tax Refund Intercept Agreement

|

Roles and responsibilities |

DHS |

ATO |

|

DHS requests and the ATO provides requested information about a taxpayer via the appropriate identified channels pursuant to relevant provisions under the child support legislations and tax law. |

✔ |

✔ |

|

DHS assesses the suitability of ATO information provided for the purposes of carrying out the Child Support Registrar’s functions. |

✘ |

Not applicable |

|

The ATO advises DHS of the potential refund available under the tax garnishee arrangements. DHS responds with a specified amount to be paid in satisfaction of debt. The ATO deducts the right amount of refund following internal and other offsetting, advises DHS of the amount deducted and arranges for payment of that amount to DHS. |

✔ |

✔ |

|

DHS and the ATO is responsible for developing procedures relating to the tax refund intercept and information exchange arrangements, making those procedures available to staff, providing adequate training to staff, and providing the procedures to each other on request. |

✔ |

✔ |

Source: ANAO analysis of the Tax Refund Intercept Agreement.

Resources

2.6 One of the guiding principles of the 2012–15 Lodgment Enforcement Agreement was that DHS and the ATO allocate sufficient resources to meet the objectives of the program within the allocated annual funding.

2.7 DHS advised the ANAO that it has dedicated a consistent proportion of officers’ time to support the program, including an Executive Level 1, Executive Level 2, Senior Executive Service Band 1 and Australian Public Service Level 6. DHS further advised the ANAO that the Lodgment Enforcement Program outcomes can require manual intervention by DHS staff but was unable to advise of the level of effort associated with completing these tasks.32 To improve program efficiency and outcomes, there is opportunity for DHS to review resourcing in relation to the customer prioritisation process and compliance action under the Lodgment Enforcement Program, as discussed in Chapter 3.

2.8 Under the 2012–15 Lodgment Enforcement Agreement, the ATO was funded for 69 full-time equivalent officers. From 2012–13 to 2014–15, the number of ATO officers dedicated to the Lodgment Enforcement Program fluctuated between 43 and 75 full-time equivalent officers (refer Table 2.4).

Was there a sound basis for determining the key terms of the agreements?

The current Lodgment Enforcement Agreement was the first not to specify a lodgment target and funding amount. The basis for the target in the initial agreement and revisions in subsequent agreements is unclear. Funding under the previous agreements was based on an estimate of staff costs at the time of the initial agreement, which was not reviewed or adjusted in subsequent agreements. The key terms of the Tax Refund Intercept Agreement, including the nature and extent of data exchange, were determined on a sound basis.

Lodgment Enforcement Agreement

Target

2.9 The 2012–15 Lodgment Enforcement Agreement indicated a target of 105 000 finalisations of income tax periods for the ATO. This target was higher than targets in preceding agreements, as illustrated in Table 2.3. The ATO defines a ‘finalisation’ for an income tax period as one of the following: a lodgment received; a ‘return not necessary’ determination33; a ‘further returns not necessary’ determination34; or a default assessment issued.

Table 2.3: Targets for Lodgment Enforcement Agreements

|

Lodgment Enforcement Agreement |

Target (per annum) |

|

First agreement (1 July 2006–30 June 2010) |

29 297 finalised casesa |

|

Second agreement (1 July 2010–30 June 2011) |

70 000 finalisations of income tax periods |

|

Extension of second agreement (1 July 2011–30 June 2012) |

101 000 finalisations of income tax periods |

|

2012–15 agreement (1 November 2012–30 June 2015) |

105 000 finalisations of income tax periods |

Note a: A finalised case occurred where the customer: lodged outstanding tax returns; or was assessed as not being required to lodge a tax return.35 All subsequent Lodgment Enforcement Agreements redefined targets as ‘finalisations of income tax periods’.

Source: Lodgment Enforcement Agreements and internal documents of DHS and the ATO.

2.10 The basis for determining the targets for the Lodgment Enforcement Program is unclear. The ATO advised that it could not locate documents detailing considerations in relation to the setting of targets. However, the ATO advised that the increases in targets were likely to be the result of it consistently exceeding the performance target each year. The ATO further advised that there was probably a reasonable assumption that as the ATO’s processes became more efficient, the target would increase while DHS’ payment remained unchanged.

2.11 There is no target set under the Abridged Lodgment Enforcement Agreement as the program funding ceased from 2015–16. Nonetheless, the ATO remains committed to achieving 105 000 income tax period finalisations per annum from 2015–16.

2.12 The ATO advised that as part of its new prioritisation approach from 2016–17 it has set a target of 1000 default assessments for the first time.36 In addition, the ATO has stated that of the 105 000 finalisations, it will aim to achieve 30 000 lodgment finalisations from taxpayers in cash economy industries or taxpayers who are employees in the Pay-As-You-Go income tax withholding system. The ATO advised that these targets have been established with consideration to its workload capacity.

2.13 The ANAO suggests that DHS and the ATO review the finalisation target set for the Lodgment Enforcement Program to ensure that there is a clear basis for the target determination, and that the target drives the achievement of intended program objectives.

Funding

2.14 As part of the Australian Government’s response to the recommendations of the Ministerial Taskforce on Child Support in 2005, funding was provided in the May 2006 Budget for DHS to implement expanded compliance arrangements for the Child Support Scheme reforms.37 The Australian Government provided $162.2 million to DHS over four years to improve compliance for the Child Support Scheme. Consequently, DHS worked collaboratively with the ATO to expand the Lodgment Enforcement Program.38

2.15 The Lodgment Enforcement Agreements from 2006–07 to 2014–15 specified the payment of an annual service fee from DHS to the ATO subject to satisfactory performance of services. The ATO advised that the funding amount was determined based on its 2005 estimate of costs to undertake the expanded Lodgment Enforcement Program of between $6.7 million and $6.9 million per annum for the four-year period from 2006–07 to 2009–10.39 DHS and the ATO continued to apply the initial 2005 cost estimate as the basis for the funding amount under the subsequent two Lodgment Enforcement Agreements, where the funding remained constant at $6.9 million (exclusive of GST). The Australian Government announced in the May 2015 Budget that the payment to the ATO for the Lodgment Enforcement Program would cease from 1 July 2015 as a measure to achieve ongoing efficiencies within DHS.40 Therefore, there is no service fee for the provision of services under the new Abridged Lodgment Enforcement Agreement. The ATO advised that there was, however, a government expectation that DHS and the ATO would continue to work together to achieve whole-of-government outcomes.

2.16 As illustrated in Table 2.4, the ATO reduced the number of resources allocated to the Lodgment Enforcement Program with the cessation of DHS funding in 2015–16. Nevertheless, the ATO has indicated its intention to retain the target of 105 000 finalisations under the Lodgment Enforcement Program.

Table 2.4: ATO staffing and costs for the Lodgment Enforcement Program

|

Financial year |

Full-time equivalent officers |

Cost |

||||

|

|

Funded |

Actual |

Difference |

Funded |

Actual |

Difference |

|

2012–13 |

69 |

65 |

-4 |

$6 875 000 |

$7 347 342 |

+$472 342 |

|

2013–14 |

69 |

43 |

-26 |

$6 875 000 |

$5 619 108 |

-$1 255 892 |

|

2014–15 |

69 |

75 |

+6 |

$6 875 000 |

$8 249 605 |

+$1 374 605 |

|

2015–16 |

0 |

30 |

+30 |

$0 |

$2 846 831a |

+$2 846 831 |

Note a: One reason for the lower cost in 2015–16 was the lesser number of lodgment activities compared to previous years. As shown in Table 5.1, the ATO completed 130 248 finalisations in 2015–16 compared to 236 436 the previous year.

Source: ATO information.

2.17 There is little correlation between the number of ATO staff and the results achieved under the program. In 2013–14, the ATO incurred the least cost for the program due to reduced staffing levels and achieved the greatest results in terms of the number of default assessments completed and amount of child support debt collected (refer Table 5.1). The ATO advised that the reduction in staff was due to the reallocation of staff to under-resourced teams.

Tax Refund Intercept Agreement

2.18 The key terms of the Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Agreement form the basis for the programs’ operations. The agreement clearly outlines the:

- nature and extent of data exchange between DHS and the ATO;

- legislative basis for the ATO’s provision of taxpayer information to DHS41;

- process for accessing and providing ATO information, including the methods for transferring the information; and

- process for transferring child support debt collected from tax refunds to DHS.

2.19 The Tax Refund Intercept Agreement does not specify a target as all eligible refunds should be actioned under the agreement. As specified in the agreement, there is no service fee payable by DHS to the ATO for the provision of taxpayers’ information or the transfer of child support debt collected through tax refund intercepts.

Do arrangements support the accurate, complete and timely transfer of data between DHS and the ATO?

Arrangements outlined in the Lodgment Enforcement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreements support the accurate, complete and timely transfer of data between DHS and the ATO. There is scope to improve ad hoc customer referral processes between DHS and the ATO for investigation purposes.

Child support population

2.20 Mutual customers of the Child Support Program and the ATO are designated as ‘clients of interest’. As at December 2016, there were approximately three million clients of interest. DHS applies an indicator to each client of interest that instructs the ATO to provide that customer’s income information and/or potential tax refund information to DHS as it becomes available.42 While DHS requires the most current income information for all child support customers, refund information is ordinarily sought in instances where a child support customer has a child support debt, has had unreliable incomes, or is a Child Support Collect payer. The three client of interest indicators are outlined in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5: Client of interest indicator definitions as at December 2016

|

Client of interest indicator |

Definition |

No. of customers |

|

COI-0 |

DHS does not require income or refund informationa |

1 224 118b |

|

COI-1 |

DHS requires both income and refund information |

906 765 |

|

COI-2 |

DHS requires income information only |

841 802 |

Note a: COI-0 represents customers who are a third party, or customers that have: no debt; no unreliable income; no case with a status of either active, ended with arrears or ended with liability due; and had no account activity for at least one year.

Note b: DHS advised that of the 1 224 118 customers with a COI-0 indicator: 1 209 839 had closed cases; 1262 had active cases; and the remainder were withdrawn, ineligible, cancelled or in the process of registration.

Source: DHS and ATO information.

2.21 DHS and the ATO undertake a reconciliation process to confirm that they share the same population of child support customers.43 Prior to 2012, this reconciliation process was automatic. DHS advised that with the introduction of the real-time data exchange process, it was more cost-effective to change the automatic reconciliation process to a manual one. DHS further advised that while automation could be re-established, it has not yet attempted to cost or develop a new automated process. DHS advised that the manual reconciliation process is undertaken approximately twice per year.

2.22 Discrepancies between the populations represent customers who have the incorrect client of interest indicator applied to them. Customer discrepancies can result in customers having an incorrect indicator and this can mean that income or refund information is not sent to DHS from the ATO. The number of client of interest discrepancies identified through the reconciliation process is illustrated in Table 2.6.

Table 2.6: Discrepancies identified in client of interest reconciliation

|

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

9826 |

5182 |

617 |

Note: DHS attributes the fall in discrepancies to data cleansing activities and addressing duplicate Tax File Numbers in the child support system.

Source: DHS information.

Lodgment Enforcement Program

2.23 Data transfer requirements under the Lodgment Enforcement Program mainly relate to the exchange of information in relation to the program and program reporting.

2.24 Potential improvements to the information exchanged in relation to the prioritisation and targeting of customers were discussed at the monthly operational meetings (refer Chapter 4), such as identifying those customers who have been referred by DHS on multiple occasions and prioritising customers according to risk factors other than the number of years without lodgment and debt amount, but these improvements were not implemented.

2.25 The 2012–15 Lodgment Enforcement Agreement required that the ATO provide DHS with a process for DHS to make ad hoc customer referrals to the ATO. The process for the ad hoc referral of customer information is unclear however, and DHS officers are referring child support customers suspected of fraud and tax evasion to three different ATO email addresses. There would be merit in consolidating and prioritising these customers for investigation as child support customers represent one-quarter of DHS customers referred for investigation of tax evasion to ATO business lines, as illustrated in Table 2.7.44

Table 2.7: Customers suspected of tax evasion who have been referred to business lines within the ATO

|

Financial year |

Total no. of DHS customers referred to business lines |

No. of child support customers referred to business lines |

Child support customers as a proportion of total |

|

2015–16 |

37 188 |

9463 |

25.4% |

Note: The ATO received 45 010 DHS customer referrals in 2015–16. Of the remaining 7822 referrals, 2362 were duplicate referrals and 5460 were determined not to be tax evasion.

Source: DHS information.

2.26 There is scope for DHS and the ATO to better utilise referral information, including by:

- improving customer profiling and targeting under the Lodgment Enforcement Program; and

- using it to confirm the accuracy of ‘return not necessary’ assessments. This was discussed at an operational meeting but was never implemented.

2.27 Only some of the ATO’s business lines routinely investigate these referrals. Due to the volume of referrals (approximately 750 per month) received by business lines such as Cash Economy and Individuals, they are used for planning purposes rather than subject to individual investigation. The ATO could consider a risk-based approach to investigating referrals.

Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs

2.28 The key information exchange arrangements as outlined in the Tax Refund Intercept Agreement are the basis for the program’s operations.

2.29 Virtually all available tax refunds are intercepted under the Tax Refund Intercept Program. DHS has 25 business days to respond to the ATO’s notification of a customer refund.45 As illustrated in Table 2.8, there have been only a small number of instances where DHS did not respond to the ATO within the required 25 business day timeframe, which may have resulted in child support debt not being collected.

Table 2.8: Number of tax refunds not intercepted because DHS did not respond within the required 25 business day timeframe

|

Refunds |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

Number of refunds not intercepted because DHS did not respond within 25 business day timeframe |

7 |

3 |

21 |

17 |

|

Amount available from refunds |

$27 685 |

$10 936 |

$38 817 |

$42 414 |

|

Amount available from refunds as proportion of total amount of child support collected through the Tax Refund Intercept Program |

0.03% |

0.01% |

0.04% |

0.04% |

|

Average amount available per refund not intercepted |

$3955 |

$3645 |

$1848 |

$2494 |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

Direct access arrangements

2.30 DHS officers are provided with direct access to the ATO’s information technology systems under the Tax Refund Intercept Agreement. However, within the agreement, it is recognised that this is the least preferred method for providing DHS with access to ATO information and that a new information exchange approach would be implemented when possible. To manage the direct access arrangement, information security measures were outlined in the agreement including: regularly reviewing the access requirements of DHS officers; and logging and reviewing access to ATO information technology systems by DHS officers.46

2.31 A 2015 ATO internal audit found that key risks associated with the direct access arrangements were not being effectively managed. In particular, the audit found that there was limited monitoring of DHS officers access to ATO systems and that while access audit logs were being produced, there was no evidence that the ATO or DHS reviewed these logs. Consequently, the audit report noted that there was a risk that DHS staff were inappropriately accessing ATO information. The audit made three recommendations and all three have been implemented.47

2.32 DHS advised that it commenced a proactive detection program in 2014–15 after the ATO’s access logs were improved to include more relevant information. The detection program involves analysing the Tax File Numbers associated with the ATO customer records accessed by DHS officers to identify if they belong to individuals known to the officer or high profile individuals. Since the program commenced in 2014–15, DHS identified 30 possible incidents of inappropriate access. Two of these incidents were referred for investigation; of which one was found to be not substantiated and the second was confirmed as unauthorised access.

Do the agreements specify risk management obligations?

The Lodgment Enforcement and Tax Refund Intercept Agreements do not specify risk management obligations between DHS and the ATO. However, DHS and the ATO advised that the proposed new agreements for the Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs will include risk management provisions. DHS and the ATO need to strengthen risk management practices for their collaborative child support collection arrangements, in particular the management of shared risks.

Lodgment Enforcement Agreements

2.33 The 2012–15 Lodgment Enforcement Agreement included a requirement for DHS and the ATO to apply and comply with the Australian and New Zealand risk management standard AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009—Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines. The Abridged Lodgment Enforcement Agreement does not specify risk management requirements for DHS and the ATO.

2.34 DHS has a risk management plan for the collection of child support debt. The Collection of Child Support Debt Risk Management Plan document, drafted in May 2016, outlined DHS’ approach to identifying, assessing and managing the risks relevant to the collection of child support debts. However, the risk management plan did not include accountabilities or responsibilities for managing risks associated with the Lodgment Enforcement Program between DHS and the ATO.

2.35 The ATO has risk assessment documents and risk treatment plans for risks associated with non-lodgment of tax returns. The ATO has not developed any specific risk management documentation to support the lodgment enforcement arrangements with DHS.48

Tax Refund Intercept Agreement

2.36 The Tax Refund Intercept Agreement does not stipulate risk management requirements for DHS and the ATO. However, DHS advised that risk management provisions are being drafted in the proposed new agreements.

2.37 DHS develops annual risk management plans for the Child Support Program. The plans outlined the approach for the management of risks associated with all systems that interface with the child support system, including the ATO system that supports the tax refund intercept and information exchange arrangements.49 However, these risk management plans did not include collaborative approaches for DHS and the ATO to manage risks associated with the Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs. DHS intends to develop a risk management plan relevant to the tax refund intercept and information exchange arrangements with the ATO in early 2017.

2.38 The ATO conducted a risk assessment for the direct access to ATO systems by DHS staff for child support program purposes in June 2015. The ATO subsequently included DHS’ direct access to the ATO systems as one of its broader enterprise risks in its ATO Open Risk Register. The ATO recognised that the DHS direct access risk is an externally-shared risk and a mitigation plan has been put in place. The ATO advised that it is also working to develop an operational level procedure to provide a more detailed agreement between itself and DHS on steps to take in managing risks/incidents in relation to system failure or information transmission.

2.39 In summary, DHS and the ATO have not assessed the shared risks under the Lodgment Enforcement, Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs. One of the elements of the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy is the requirement for Commonwealth entities to implement arrangements to understand and contribute to the management of shared risks.50 There would be merit in DHS and the ATO strengthening the management of shared risks associated with their collaborative child support collection arrangements.

Recommendation No.1

2.40 The Department of Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office implement arrangements to manage shared risks in administering the Lodgment Enforcement, Tax Refund Intercept and Information Exchange Programs.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

2.41 The department notes the ANAO acknowledges that the department has existing risk management plans which may not necessarily be captured in shared documentation, however roles and responsibilities are clearly documented and risks are acknowledged and managed on a regular basis. The department has commenced work with the ATO to develop shared risk management arrangements to support the identification, mitigation, monitoring and reporting of shared risks.

Australian Taxation Office’s response: Agreed.

2.42 The ATO continues to work with DHS to develop and implement a shared risk framework, which will detail the actions to be taken including the responsibilities and accountabilities for risk management.

3. Program implementation

Areas examined

This chapter examines the two agencies’ implementation of the cooperative child support programs, particularly in targeting compliance activities under the Lodgment Enforcement Program, and conducting compliance activities under all programs to help maximise child support collection.

Conclusion

The vast majority of tax refunds are intercepted under the Tax Refund Intercept Program. Under the Lodgment Enforcement Program, DHS and the ATO can improve the prioritisation and targeting of customers by better considering other child support compliance risks. DHS can also improve its monitoring of the application of income information received from the ATO to inform program design.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at: improving the prioritisation and targeting of customers under the Lodgment Enforcement Program (paragraph 3.14); and monitoring the application of income information to child support payment assessments (paragraph 3.39).

Are activities effectively targeted under the Lodgment Enforcement Program?

The selection of customers for compliance activities under the Lodgment Enforcement Program can be better targeted by considering risks such as compliance history, lifestyle factors, employment type and industry. DHS and the ATO do not strategically employ broader compliance activities to target customers subject to the Lodgment Enforcement Program. Further, the level of program activity undertaken by the ATO has declined markedly with the cessation of DHS funding in 2015–16, and more than half of the program results are of limited benefit to DHS.

Prioritising customers for action

3.1 The 2012–15 and Abridged Lodgment Enforcement Agreements specify that DHS will supply a prioritised population of customers to the ATO for lodgment enforcement action.51 DHS has referred approximately 440 000 customers each year to the ATO under the Lodgment Enforcement Program.

3.2 Table 3.1 outlines the number of customers by population category referred from DHS to the ATO from 2013–14 to 2016–17.

Table 3.1: Customers referred from DHS to the ATO, 2013–14 to 2016–17

|

Category |

Description of category |

No. of customers referred to the ATO |

|||

|

|

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

|

|

1a |

Debt >$100 000 with multiple income tax periods overdue |

16 893a |

69 |

55 |

160 |

|

1b |

Debt >$50 000 and <=$100 000 with multiple income tax periods overdue |

774 |

530 |

553 |

|

|

1c |

Debt >$20 000 and <=$50 000 with multiple income tax periods overdue |

5998 |

4136 |

4148 |

|

|

1d |

Debt >$10 000 with multiple income tax periods overdue |

9177 |

6749 |

6437 |

|

|

2 |

Debt >=$1,000 and <=$10,000 with multiple income tax periods overdue |

28 037 |

23 784 |

18 688 |

17 415 |

|

3 |

Debt >=$1,000 with a single income tax period overdue |

14 856 |

16 211 |

29 704 |

25 489 |

|

4a |

Debt >=$1 and <$1,000 with multiple income tax periods overdue |

251 816b |

238 810b |

22 382 |

21 467 |

|

4b |

Debt =$0 with multiple income tax periods overdue |

209 601 |

198 307 |

||

|

5 |

Debt <$1,000 with a single income tax period overdue |

136 397 |

140 612 |

180 322 |

166 715 |

|

Total |

447 999 |

435 435 |

472 167 |

440 691 |

|

Note a: Categories 1a to 1d were not in place in 2013–14.

Note b: Category 4 was not split into two components prior to 2015–16.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

3.3 As illustrated in Table 3.1, DHS prioritises customers according to the value of their outstanding debt and number of years without lodgment; categories 1a and 1b represent the highest priority while category 5 is of lowest priority. DHS does not prioritise customers according to broader risk factors such as compliance history, lifestyle factors, employment type and industry. While DHS indicated in its Compliance Program 2013–2015 that it would increase its focus on parents who avoid their child support responsibilities through the cash economy or deliberate misrepresentation of their income, there is no such prioritisation of customers for the Lodgment Enforcement Program.52

3.4 DHS is notified on a weekly basis by the ATO of customers who have been assessed as not being required to lodge tax returns. However, as DHS requires an ATO-assessed taxable income for these customers, it does not exclude them from the population referred to the ATO. These customers represent the majority of customers subsequently removed as part of the ATO’s review of the population.53 As illustrated in Table 3.2, the number of customers removed from the population by the ATO has been steadily increasing.

Table 3.2: Customers removed by the ATO from the population referred by DHS

|

Financial year |

Number of customers removed from the population |

Number of customers remaining in the refined population |

Removed customers as a proportion of the total number referred |

|

2013–14 |

112 519 |

335 480 |

25.1% |

|

2014–15 |

132 415 |

303 010 |

30.4% |

|

2015–16 |

170 508 |

301 659 |

36.1% |

|

2016–17 |

173 281 |

267 308 |

39.3% |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

3.5 The ATO advised the ANAO that following its initial refinement, it targets customers according to DHS’ priorities. However, the ANAO found that not all customers from DHS’ higher priority categories are contacted. The ATO advised that additional customers may be removed from the refined population by applying the exclusions used in its initial review (see footnote 53). The ATO did not provide evidence to confirm that this was the approach it applied. The ANAO identified a number of information sources that referred to the ATO’s application of the risk to revenue approach to the population. However, the ATO advised that it did not apply this model.54

3.6 There is some misalignment between customers who represent a risk to the ATO and those who are a risk to DHS. For example, customers with Pay-As-You-Go income tax withholding arrangements are generally a low revenue and compliance risk for the ATO as their income tax has already been collected. However, for DHS these customers are a priority if they have not lodged a tax return for a number of years and/or have a child support debt.

3.7 For the 2016–17 population, the ATO analysed the population according to employment type and industry to better categorise customers in line with its current compliance risks.55 From this activity, the ATO identified a population that is categorised as joint DHS and ATO priority customers, including customers with high risk to revenue scores regardless of DHS priority category.56

Targeting customers

3.8 Customers targeted under the Lodgment Enforcement Program are sent letters from the ATO. Letters are sent to those customers within the refined populations of DHS’ higher priority categories followed by customers in lower priority categories (as set out in Table 3.1 and Table 3.2). Those customers in higher priority groups who do not lodge tax returns following the ATO’s lodgment enforcement mail out subsequently receive up to three telephone calls. The ATO may also initiate ‘other actions’ against these customers, including field investigations and risk reviews.57

3.9 The ATO does not target every customer in the refined population. The number of customers contacted is dependent on the ATO’s priorities and capacity. As illustrated in Table 3.3, the proportion of the target population to be actioned by the ATO reduced to 32.0 per cent in 2015–16 with the cessation of funding from DHS. With a reasonably small proportion of the target population being actioned by the ATO, effective targeting is required to ensure meaningful program results, for example, lodgment of income tax returns.

Table 3.3: Lodgment Enforcement Program actions

|

Financial year |

No. of individuals targeted |

No. of individuals as a proportion of refined population |

No. of letters sent |

No. of phone calls |

No. of other actions initiated |

No. of prosecution cases initiated |

|

2013–14 |

191 229 |

57.0% |

341 711 |

34 922 |

6108 |

377 |

|

2014–15 |

223 962 |

73.9% |

563 137 |

40 314 |

6097 |

1553 |

|

2015–16 |

96 429 |

32.0% |

220 575 |

5416 |

2731 |

574 |

Note: The number of lodgments is reported in Table 5.1.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

3.10 Customers in the higher priority groups who are repeatedly contacted by the ATO without achieving lodgment outcomes may be escalated for prosecution action or a default assessment (refer paragraphs 3.21 to 3.23). Prosecutions for non-lodgment can result in convictions and fines but may not result in the lodgment of tax returns. This is illustrated by a comparison of the number of prosecutions undertaken (Table 3.3) with the number of customers subject to prosecution who subsequently lodged tax returns (Table 3.4).58.

Table 3.4: Number of customers subject to prosecution for non-lodgment who subsequently lodged tax returns

|

Financial year |

Number of customers who lodged tax returns |

Number of tax returns lodged |

|

2013–14 |

123 |

783 |

|

2014–15 |

509 |

2570 |

|

2015–16 |

163 |

900 |

Source: ATO information.

3.11 As illustrated in Table 3.5, few child support customers are charged penalties by the ATO. Financially penalising customers for non-lodgment of tax returns could act as a disincentive for non-lodgment to those customers who have been penalised as well as the broader child support population if it was effectively communicated as part of an awareness campaign.

Table 3.5: Number of non-lodging child support customers who were charged penalties

|

Financial year |

No. of individuals penalised |

Proportion of customers targeteda |

Total penalties charged |

|

2013–14 |

1248 |

0.7% |

$838 980 |

|

2014–15 |

933 |

0.4% |

$646 940 |

|

2015–16 |

901 |

0.9% |

$707 730 |

Note a: This is as a proportion of individuals targeted under the Lodgement Enforcement Program (refer Table 3.3).

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

3.12 Child support customers are not strategically targeted in the ATO’s broader compliance work despite the potential dual incentive for them to minimise their income to avoid paying tax as well as child support. The Cash Economy business line applies case selection rules to identify taxpayers for compliance action. Despite 10 per cent of taxpayers identified by the Cash Economy risk model having a child support indicator, it is assigned a very low risk score compared with other risk indicators within the model.59 The Individuals business line does not have a child support risk indicator in any of the risk models applied to identify taxpayers to target with compliance action. The Lodgment Enforcement Program also does not refer customers to other relevant business lines for consideration and action as part of their compliance activity.

3.13 In summary, the Lodgment Enforcement Program does not effectively target the breadth of compliance risks associated with the child support customers who do not lodge their income tax returns, for example, customers with an extensive history of non-compliance or who may be operating in the cash economy. There is an opportunity for DHS and the ATO to: better prioritise customers according to compliance risks; develop strategies to target different customer groups, including those with serious non-compliance backgrounds or who would not normally be subject to ATO compliance activity; and better target customers with compliance actions, including the strategic use of broader compliance mechanisms.

Recommendation No.2

3.14 The Department of Human Services and the Australian Taxation Office:

- prioritise customers under the Lodgment Enforcement Program according to the most relevant child support compliance risk factors; and

- strategically employ broader compliance activities to target child support customers.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

3.15 The department notes the ANAO acknowledges that the department does prioritise customers under the Lodgment Enforcement Program according to the relevant child support compliance risk factors such as the value of the outstanding debt and number of years without lodgment. Nonetheless, the department will commence discussions with the ATO to identify if further prioritisation can be applied to better maximise program outcomes.

Australian Taxation Office’s response: Agreed.

3.16 The ATO will continue to work with DHS to ensure prioritisation of taxpayers according to relevant risk factors. Additionally, the ATO will consider the introduction of additional compliance activities to better target child support customers currently outside the ATO’s treatment framework.

Do compliance activities maximise child support collection opportunities?

The Tax Refund Intercept Program maximises child support collections as virtually all available refunds are intercepted. However, there are opportunities to increase child support collections under the Lodgment Enforcement Program by the ATO achieving a higher proportion of meaningful outcomes, such as tax return lodgments and default assessments. To inform program design, DHS should analyse the extent to which ATO-assessed taxable incomes are applied to child support payment assessments.

Lodgment Enforcement Program

3.17 Assessments that customers are not required to lodge tax returns are of limited benefit to DHS and yet they represent more than half of the Lodgment Enforcement Program outcomes. Further, default assessments result in income determinations that can be applied to child support payment assessments, however, the ATO undertakes relatively few default assessments for child support customers.

Return not necessary

3.18 As discussed in paragraphs 1.8, 1.9 and 4.15, for child support purposes, all customers are required to lodge a tax return. However, for taxation purposes, some child support customers are exempt from lodging tax returns. Since 2013–14, over 90 per cent of the customers removed from the referred population by the ATO as part of its review process were assessed as not being required to lodge tax returns (refer Table 3.2). From 2013–14 to 2015–16, approximately 55 per cent of the reported program outcomes were assessments that customers were not required to lodge tax returns (refer Table 5.1). These assessments were based on customers notifying the ATO that they were not required to lodge tax returns and automatic assessments generated by the ATO’s data matching with other government agencies.60

3.19 Most customers are assessed as not being required to lodge tax returns because their only source of income is welfare payments that total below the relevant income threshold. As illustrated in Table 3.6, since 2013–14 over 8000 customers within categories 1a to 1d, who have debts over $10 000 and have not lodged tax returns for multiple income tax periods (Table 3.1), have been assessed as not being required to lodge income tax returns either for a relevant income year or in the future. DHS does not specifically target these customers through its compliance program. Given the size of some customers’ debts, there would be merit in DHS applying a risk-based approach to considering these customers for compliance action.

Table 3.6: Return not necessary and further return not necessary outcomes

|

Category |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|||

|

|

RNNa |

FRNNb |

RNNa |

FRNNb |

RNNa |

FRNNb |

|

1a |

3087 |

24 |

22 |

1 |

15 |

0 |

|

1b |

119 |

2 |

60 |

0 |

||

|

1c |

1068 |

7 |

480 |

2 |

||

|

1d |

2289 |

10 |

933 |

10 |

||

|

2 |

6557 |

108 |

6280 |

30 |

2148 |

16 |

|

3 |

2192 |

46 |

2145 |

22 |

3185 |

28 |

|

4a |

11 542 |

348 |

7700 |

90 |

3535 |

37 |

|

4b |

54 901 |

2522 |

77 653 |

966 |

39 809 |

353 |

|

5 |

13 433 |

716 |

27 708 |

389 |

20 817 |

232 |

|

Total |

91 712 |

3764 |

124 984 |

1517 |

70 982 |

678 |

Note a: RNN stands for ‘return not necessary’. Refer paragraph 3.19.

Note b: FRNN stands for ‘further return not necessary’. Refer to paragraph 3.20.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

3.20 Customers may be assessed as ‘further return not necessary’ for a number of reasons, including that they are moving overseas, are in receipt of an age or disability pension, or their business has ceased trading. This assessment means that the ATO does not expect these customers to lodge tax returns in the future. As at 19 December 2016, the ATO provided advice to DHS that 120 115 child support customers had ‘further return not necessary’ indicators on their records. Of these customers: 7619 had outstanding tax returns; 4147 had debts; and 2050 had outstanding tax returns and debts.61 DHS advised that these customers may be subject to its business-as-usual compliance arrangements and are not specifically targeted for compliance action. As these customers would not be subject to the ATO’s Lodgment Enforcement or Tax Refund Intercept Programs, DHS could consider specifically targeting these customers with alternate compliance approaches.62

Default assessments

3.21 The ATO can issue a default assessment of taxable income when customers have outstanding tax returns. This assessment is based on information available to the ATO, including in relation to employment, bank accounts and investments. DHS can apply the default assessment income amounts to new child support obligations for customers.

3.22 The default assessment amount should better reflect the customer’s capacity to pay child support as it is based on their current financial position. Default assessments can act as an incentive for customers to lodge tax returns, for example, where they do not consider the default assessment amount accurately represents their circumstances.

3.23 Default assessments may result in increased child support collections where a customer’s previous child support obligation was based on an income amount—either an estimate or an outdated taxable income—that was lower than the default assessment amount. The issuance of default assessments has been declining since 2013–14 (refer Chapter 5), due to the reverse workflow associated with the assessments and the planned implementation of an accelerated default assessment pilot that was never introduced.63

3.24 Recognising the wider benefits to government of accurate child support payment assessments, including minimising child support and Family Tax Benefit debts, in 2016–17 the ATO set a target to complete 1000 default assessments—approximately one-fifth of the number completed in 2013–14.64

Tax Refund Intercept Program

3.25 The Tax Refund Intercept Program contributes the highest amount of child support debt collected among the collaborative programs undertaken by DHS and the ATO, and data examined by the ANAO indicates extremely high levels of intercepts by the ATO. In some circumstances, the amount of child support debt available for collection is limited by the application of a debt hierarchy and financial hardship provisions.

Proportion of tax refunds intercepted

3.26 The ANAO’s data analysis identified a small number of possible instances where the ATO did not intercept a tax refund despite being advised by DHS to do so, as illustrated in Table 3.7.65 The ATO advised that while these may be missed opportunities, there are other explanations for why an intercept may not have been undertaken, including that between the time when the ATO notified DHS of the tax refund and DHS responded, further events associated with the customer’s account reduce the available tax refund to nil.66 The ATO has subsequently reviewed a sample of potential missed tax refund intercepts identified in the ANAO’s analysis. Of the 47 cases reviewed, the ATO advised that in: 35 cases the amount requested by DHS was not intercepted for a valid reason; eight cases there was no obvious reason for the intercept not being undertaken; and four cases the refund was correctly intercepted but the data provided to the ANAO did not reflect this.

Table 3.7: Possible missed tax refund intercept opportunities

|

Intercepts |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

No. of customers who had less intercepted than requested by DHS |

146 |

150 |

12 |

8 |

|

No. of customers who had nothing intercepted |

795 |

684 |

46 |

26 |

|

Amount of child support debt not collected |

$303 985 |

$411 296 |

$62 411 |

$60 485 |

|

Amount of child support debt not collected as a proportion of total amount collected through the Tax Refund Intercept Program |

0.30% |

0.40% |

0.10% |

0.10% |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

3.27 The ANAO’s analysis also identified a small number of instances where tax refunds were intercepted without DHS’ confirmation, as illustrated in Table 3.8. The ATO has subsequently reviewed a sample of 77 of the tax refunds intercepted without DHS confirmation and advised that: 46 cases had a valid reason for the interception; four cases had no obvious reason for the interception; and 27 cases were appropriately intercepted but the information provided to the ANAO did not reflect this.

Table 3.8: Number of tax refunds intercepted without DHS confirmation

|

Tax refunds |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

Number of refunds intercepted without DHS confirmation |

586 |

192 |

4 |

47 |

|

Amount of child support debt collected |

$640 982 |

$204 420 |

$4672 |

$337 038 |

|

Amount of child support debt collected as a proportion of total amount collected through the Tax Refund Intercept Program |

0.7% |

0.2% |

0.0% |

0.3% |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO information.

Hierarchy of debts