Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Case Management by the Office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- CDPP prosecutes diverse Commonwealth law offences, from tax and social security fraud to organised crime and terrorism.

- Lengthy legal processes adversely affect witnesses and victims and undermine public confidence in the justice system.

- Efficient and effective Commonwealth prosecution activities increase the likelihood of deterring potential offences against Commonwealth law and regulations.

- How decisions to prosecute are made influences the efficiency of Commonwealth prosecutions.

Key facts

- In 2018–19, 46 Commonwealth and 16 state and territory agencies referred 2,579 briefs of evidence about alleged crimes to CDPP.

- 49% of referrals required CDPP to assess the brief of evidence and determine whether charges should be laid. Referred crimes have become more complex.

- CDPP is required to prosecute if there is a reasonable prospect of conviction and it is in the public interest: 82% of assessed matters proceeded to prosecution in 2018–19.

What did we find?

- Based on the available data, the efficiency of CDPP’s brief assessment is declining, The increasing average cost of outputs, flowing from a reduction in referrals, has not been fully offset by improvements in quality and timeliness.

- Appropriate governance structures, systems and processes are in place, but there are inefficiencies in brief assessment workflow.

- The timeliness of brief assessment has improved, but the average number of referrals processed has decreased and the average cost per referral processed has increased.

- Efficiency data is not sufficiently measured, monitored and publicly reported to inform continuous improvement.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made four recommendations to CDPP. They relate to management reporting; cost monitoring; timeliness targets; and performance reporting.

- The CDPP agreed with the recommendations.

28%

Decrease in investigative agency referrals over 5 years

78 days

Average time to assess a brief, within a benchmark of 90 days

1,263

Total number of brief assessments completed in 2018–19

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) was established on 5 March 1984 by the Director of Public Prosecutions Act 1983. The CDPP provides a prosecution service for alleged offences against the laws of the Commonwealth. Crimes prosecuted range from tax and social security fraud to money laundering, organised crime, terrorism and espionage. Evidence of an alleged crime is compiled in a brief of evidence and referred to the CDPP by investigative agencies. In 2018–19, 46 Commonwealth and 16 state and territory agencies referred briefs to the CDPP.

2. The day-to-day work of the CDPP includes providing pre-brief advice to agencies, assessing the briefs that they provide, and prosecuting offences in state and territory courts.

3. Of the 2,579 referrals made to the CDPP in 2018–19, 49 per cent were ‘brief assessment’ referrals. In a brief assessment referral, the CDPP reviews the evidence provided by the investigative agency and determines whether charges should be laid. An additional 29 per cent were ‘arrest’ referrals. An arrest referral occurs when an investigative agency with arrest powers — for example, the Australian Federal Police — has already charged the defendant. The balance of referrals includes requests for pre-brief advice, breaches, extradition matters, matters referred post-committal and some appeals. Upon receipt, referrals are classified by the CDPP as complexity one to four, with four representing the most complex matters.

4. The Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth is the overarching policy guiding the CDPP’s prosecution service, including the decision to proceed with a prosecution in ‘brief assessment’ matters or to maintain the charges in ‘arrest’ matters. Once a prima facie case has been established, a decision needs to be made by the CDPP as to whether there is a reasonable prospect of conviction. Evidence must be admissible, substantial and reliable. Prosecutors must also consider whether a prosecution would be in the public interest. Of 1,263 brief assessment referrals finalised by the CDPP in 2018–19, a decision to proceed with a prosecution occurred in 82 per cent of referrals.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The efficiency of the criminal justice system is a matter of public interest. Lengthy court processes can adversely affect witnesses and victims, along with other participants in prosecutions. Efficient and effective Commonwealth prosecution activities increase the likelihood of deterring potential offences against Commonwealth law and regulations, support Commonwealth regulators in enforcing compliance and are essential in maintaining respect for Commonwealth law. How prosecution services are organised; how the decision to prosecute is made; the nature of the relationship between prosecutors and investigative agencies; and the way prosecutors operate within the court system, influence overall efficiency.

6. Undertaking an audit of the case management efficiency of the CDPP also addresses Parliamentary interest. The topic was included in the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit’s list of audit priorities for 2018–19, with a request that the audit include prosecutions by the CDPP of corporate crimes, with a specific focus on matters referred to the CDPP by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The audit objective is to examine the efficiency of the CDPP’s case management. The audit is focused on the pre-brief and brief assessment phases of the CDPP’s work and examines the extent to which the CDPP uses its resources efficiently in evaluating referred matters.

8. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Does the CDPP have arrangements to support the efficient assessment of referred briefs?

- Does existing performance data indicate that the CDPP assesses briefs efficiently?

- Is the CDPP effectively monitoring and reporting on its case management performance?

Conclusion

9. Based on the available data, the efficiency of the CDPP’s brief assessment is declining. The increasing average cost of outputs, flowing from a reduction in referrals, has not been fully offset by improvements in quality and timeliness.

10. The CDPP has established key elements to support the efficient assessment of briefs. Governance structures are appropriate and investigative agency engagement largely supports the objective of improving brief quality. Case management systems and digital processes are developing and operational guidelines are extensive. While the average timeframe for the completion of assessments is 78 days, which is consistent with the CDPP’s target, there are inefficiencies in the administration of key activities within the assessment workflow. Management reporting does not provide sufficient visibility over key drivers in efficient brief assessment practice.

11. Analysis of available efficiency-related performance data indicates that, in the period 2014–15 to 2018–19, the CDPP’s average number of brief assessment referrals processed per prosecutor decreased. The average cost per output (brief assessment and other types of referrals) increased. However, the average time taken to assess briefs markedly improved over the same period, and on average investigative agencies are more satisfied.

12. The CDPP is partly effective in monitoring and reporting on case management performance. Most of the requisite data is collected, but key efficiency drivers and the average cost of outputs are not sufficiently monitored. An 85 per cent within 90 days brief assessment service standard is embedded in practice and monitored, but the target does not drive timeliness across the full spectrum of brief complexity. The annual performance reporting framework provides a partial representation of how well the CDPP is achieving its purpose.

Supporting findings

Arrangements to support the efficient assessment of briefs

13. The CDPP has an appropriate governance structure. Governance frameworks include clear accountabilities, processes for oversight, delegated decision-making and systems for risk management. For 2019–20, the CDPP established budgets at the practice group level for key expense items.

14. The CDPP’s processes for engagement with investigative agencies largely support the efficient assessment of briefs upon referral. Agency engagement is a core focus of strategic planning and case management practice, and systems and tools have been developed for this purpose. Stakeholder satisfaction with CDPP engagement is improving, on average. In practice, the nature and extent of liaison activities vary between investigative agencies and there is no overarching engagement strategy.

15. The CDPP has systems which can support the efficient assessment of briefs. Case management systems are developing and embed decision-making workflows. Digital practices and associated systems have been established to encourage the submission of e-briefs, which facilitate efficient case management and evidence analysis. A management reporting system enables analysis of brief assessment volumes and statistics.

16. The CDPP’s operational policies and procedures are designed to support the efficient assessment of briefs. The CDPP has a large volume of operational guidelines and policies to support brief assessments and prosecutions. The CDPP is rationalising and digitising these materials, and some are embedded in the case management system, caseHQ.

17. The CDPP’s operational practices partly support the efficient assessment of briefs. The average timeframe for the completion of assessments is 78 days. Although this is consistent with the CDPP’s target of 85 per cent completed within 90 days, there are inefficiencies in relation to the assignment of briefs to branches and work groups; lack of initial triage for early identification of critical deficiencies in evidence that may prevent or delay a timely assessment; inconsistent follow-up with investigative agencies after the issuing of requisitions for additional evidence; and inconsistent records management practices. Management reporting does not allow supervisors to fully monitor and act on deficiencies in brief assessment practice in order to ensure efficiency in these areas.

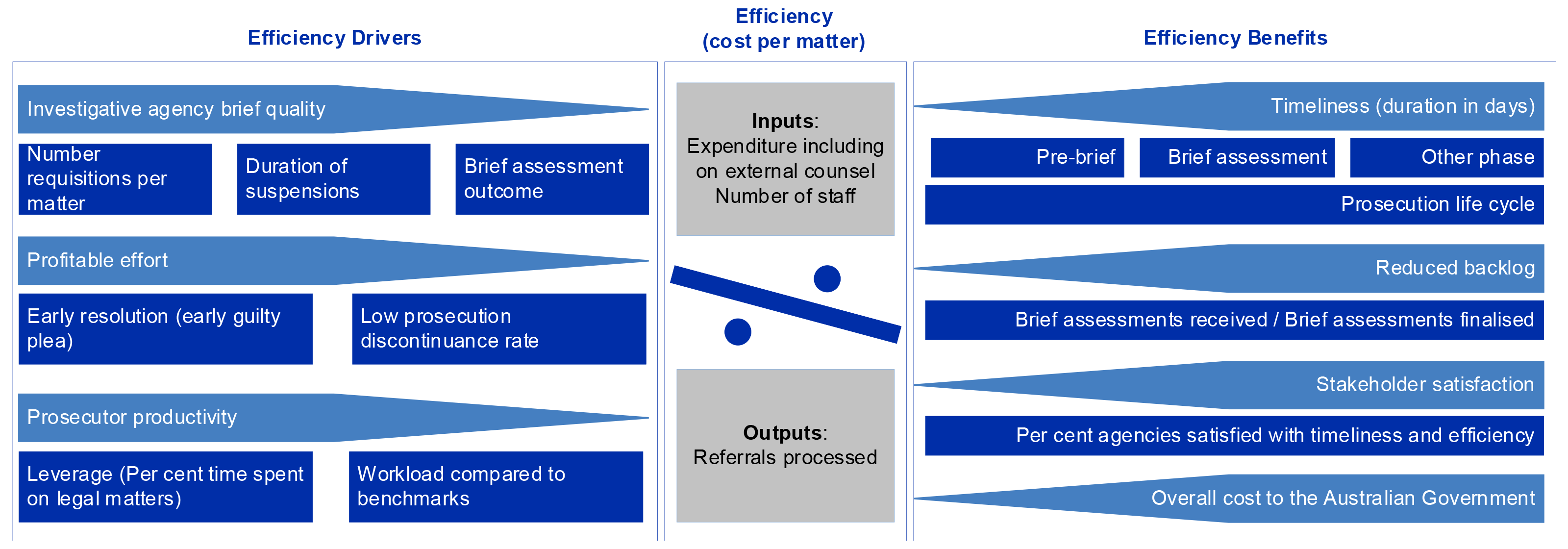

Performance analysis of brief assessment efficiency

18. Analysis of available performance data indicates that the average cost of a brief assessment has increased, noting that timeliness and stakeholder satisfaction have improved. The volume of brief assessments and other referrals processed by the CDPP decreased in the five years to 2018–19 due to a decline in referrals. Annual agency level expenses are unchanged. The average complexity of matters referred to the CDPP has increased, however, after weighting for complexity there is a decline in the average number of brief assessments referred per prosecutor employed. In the same five-year period, there were efforts to reduce backlog and timeliness in brief assessment improved. Investigative agency feedback reflects higher satisfaction levels.

Performance monitoring and reporting

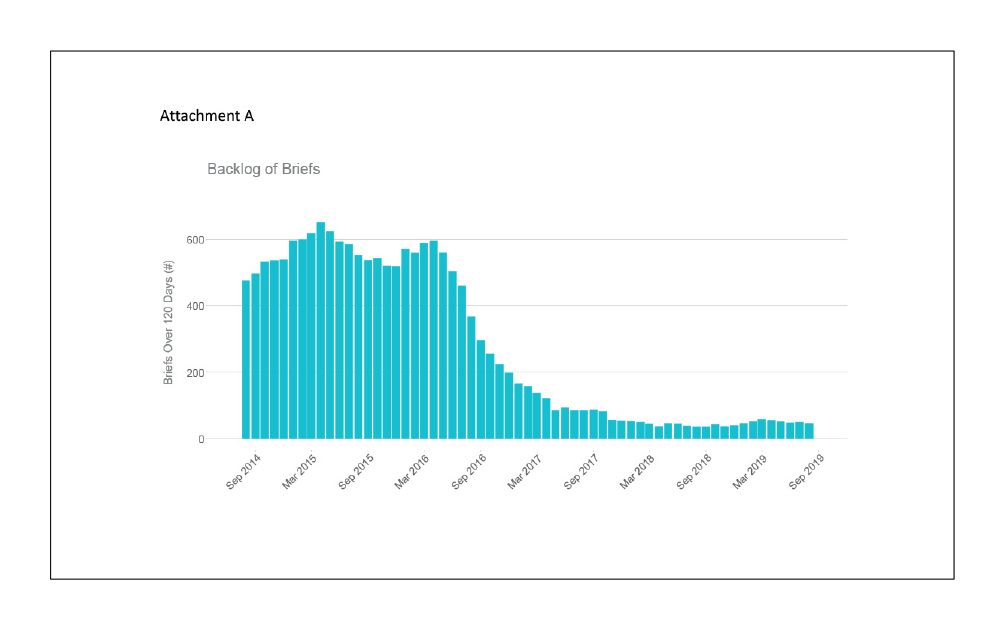

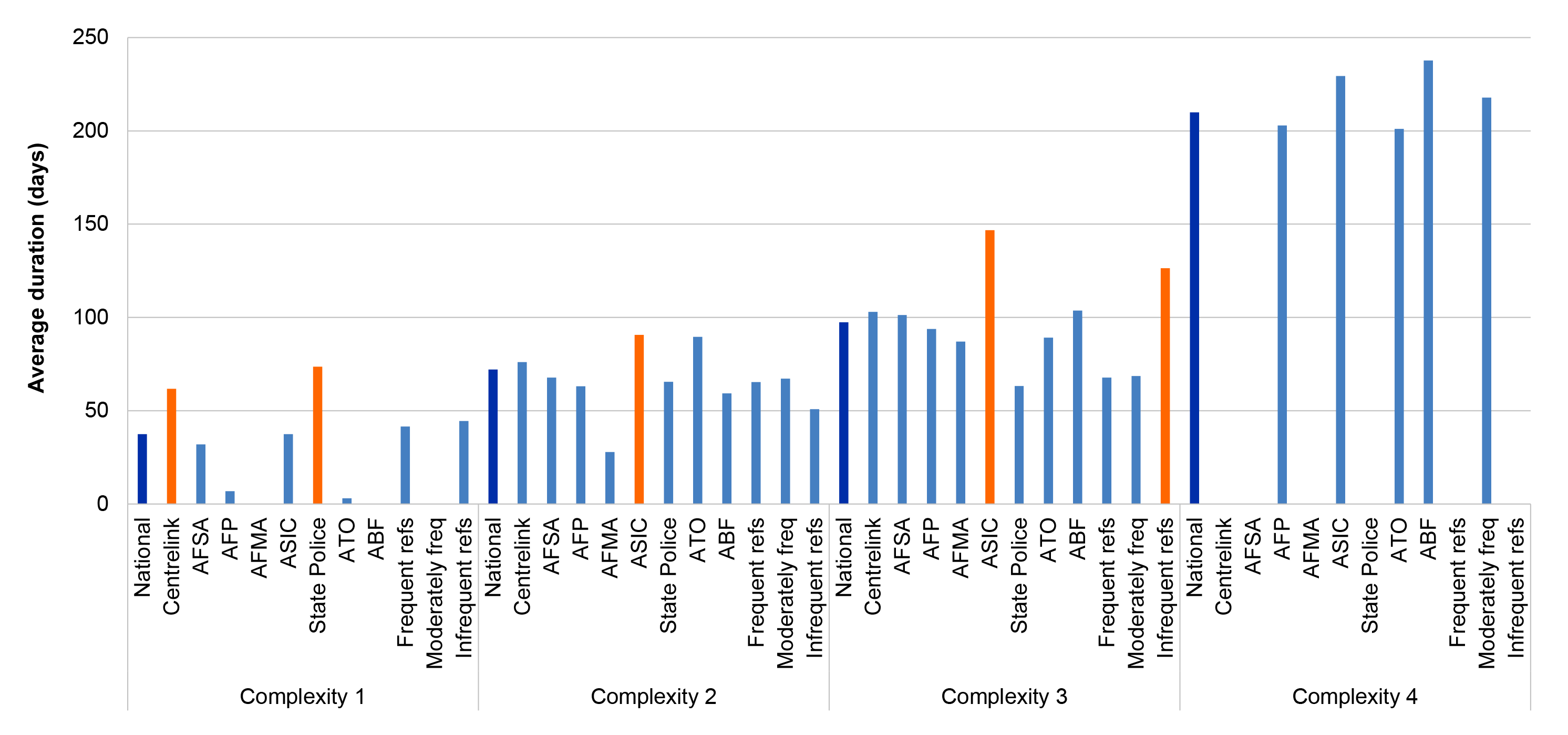

19. The CDPP routinely collects some efficiency data, but can improve its monitoring and use of this information in order to drive improvement. Data on efficiency drivers, such as brief quality and assessment outcomes, is collected but not monitored. A funding model could calculate average costs, but such analysis is not done. Efficiency benefits such as brief assessment timeliness, backlog and stakeholder satisfaction are monitored. The 85 per cent within 90 days brief assessment service standard is embedded in brief assessment practice and has effectively driven behaviour for complexity two and three matters, however the usefulness of the service standard is reduced by its inappropriateness for complexity one and four matters, lack of awareness among investigative agencies, and lack of diagnosis of delay.

20. The performance framework established by the CDPP is partly effective. The three annual performance measures are relevant, but there are weaknesses in reliability. The measures provide a partly complete representation of the extent to which the CDPP is achieving its purpose as there are no qualitative, long-term or efficiency measures.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.79

The CDPP revise management dashboard reporting to ensure that supervisors can readily access key efficiency-related information, including case officer activities during triage and suspension periods, actions taken to encourage early resolution, and time recording compliance.

Office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 4.20

The CDPP establish a process to utilise existing data to monitor case management efficiency in terms of the average cost involved in processing referrals, including in conducting brief assessments and prosecutions.

Office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 4.36

The CDPP establish appropriate timeliness targets for each brief complexity category, formally communicate these to investigative agencies, and detail the results and methodology in the annual report.

Office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 4.56

The CDPP improve the reliability and completeness of performance criteria presented in its corporate plan and annual performance statements by establishing:

- a process to provide assurance that prosecutors are adhering to the Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth when assessing briefs and conducting prosecutions;

- a consistent, robust and transparent methodology for the surveying of investigative agency satisfaction; and

- a case management efficiency criterion in the annual performance statement.

Office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

21. The Office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecution’s summary response to the report is provided below, and its full response is at Appendix 1.

The CDPP is proud of the work undertaken by its staff in the last 5 years in delivering a timely and high quality prosecution service to the Australian community in a rapidly evolving law enforcement and national security landscape.

The CDPP welcomes and agrees with the ANAO’s recommendations but does not agree with its finding and conclusion that the efficiency of the CDPP’s brief assessment referral practice is declining. The Report’s conclusion is based on the CDPP receiving fewer brief assessment referrals than 5 years ago, the CDPP’s expenses remaining at a similar level and with similar numbers of prosecutors employed. The Report fails to sufficiently recognise qualitative and quantitative improvements in the CDPP’s brief assessment practice. Additionally, the ANAO’s analysis does not take into account the number of people actually working on brief assessments, instead using our total workforce numbers for their efficiency calculations. The Report also fails to sufficiently recognise the broader imperatives driving the CDPP’s current operations. The CDPP submits that the Report’s analysis on this aspect is overly simplistic and regrettably, ultimately unhelpful.

The CDPP responds to the work that is referred to it by 68 federal, state and territory investigative agencies. In the last 5 years the law enforcement world has changed markedly, and the CDPP has changed with it. We are seeing a trend away from large numbers of straightforward brief assessment cases being referred and prosecuted in the lower courts. As recognised by the ANAO, we now have a practice with an increase in more complex serious criminal cases. This counter trend is driving an increase in requests for pre-brief advice, more arrest based referrals and more cases being dealt with on indictment in the higher courts.

We have two main responses to the ANAO Report. Firstly, efficiency has improved in CDPP’s brief assessment practice. A comparison of actual prosecutor time spent on brief assessment referrals converted to FTE, indicates a drop in FTE of approximately 30% from 2014-15. A significant backlog of overdue files has been eliminated in that period. The average number of hours expended on assessing briefs of the same complexity has declined or stayed the same. And, the average time taken from receipt of the case to finalising the assessment has halved from 151 days to 78 days, even though these assessments are becoming more complex. Partner agency satisfaction, unsurprisingly, is at a very impressive 87%.

Secondly, with less time needed for brief assessment work, which is only a part of the work of prosecutors, prosecutors and other staff are reallocating effort to where it is needed – an expanding pre-brief advice service, an expanding Witness Assistance Service for our most vulnerable witnesses (often children in child exploitation cases), navigating the complexities of litigating multi-defendant white collar, terrorism and organised crime cases or cases with national security sensitivities, undertaking significant digital transformation and business improvement work and agency training, liaison and law reform. The modern law enforcement landscape has thrown up new priorities, challenges and costs of business for the CDPP, which are not sufficiently recognised, as they were largely outside the scope of the audit.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages that have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Performance and impact management

Program implementation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) was established on 5 March 1984 by the Director of Public Prosecutions Act 1983 (DPP Act). It is one of 16 entities that sit within the Attorney-General’s portfolio. The CDPP is a non-corporate Commonwealth entity under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.

1.2 The purpose of the CDPP is ‘To prosecute crimes against Commonwealth law through an independent prosecution service that is responsive to the priorities of our law enforcement and regulatory partners, and that effectively contributes to the safety of the Australian community and the maintenance of the rule of law.’1

The CDPP’s work

1.3 The CDPP prosecutes alleged offences against the laws of the Commonwealth2 on behalf of the community rather than individual victims.3

1.4 Evidence of an alleged Commonwealth crime is compiled in a brief of evidence and referred to the CDPP by investigative agencies. In 2018–19, 46 Commonwealth and 16 state and territory agencies referred briefs to the CDPP. Appendix 2 shows the investigative agencies that referred brief assessment matters to the CDPP from 2014–15 to 2018–19.

1.5 The work of the CDPP includes three core phases.

- Pre-brief advice — prior to receiving a brief of evidence from an investigative agency, the CDPP can offer advice to agencies about choice of charges, the elements of offences, impediments to proving the offence, witnesses, lines of enquiry and public interest considerations.

- Brief assessment — the CDPP assesses the briefs of evidence that investigative agencies refer and decides whether to prosecute. If the investigative agency has already laid charges prior to referring the brief to the CDPP (an arrest referral), the CDPP will consider whether the charge should be maintained. Otherwise, the CDPP conducts an assessment of the brief to determine whether charges should be laid (a brief assessment referral).

- Prosecution — charges are laid by the investigative agency following arrest, or following brief assessment by the CDPP. The CDPP is responsible for carrying out prosecutions of indictable4 and summary offences. The CDPP will prosecute the matter in the relevant state and territory local, district or supreme court, according to that court’s procedures and conventions. The process can include hearings, trials, committals, sentencing and appeals. Once a prosecution has started, the investigator becomes known as the informant.

1.6 In addition to these activities, the CDPP provides input into wider Australian Government law reform activities and participates in Royal Commissions.

1.7 Figure 1.1 shows the prosecution process for brief assessment referrals, which begins with the referral of a brief of evidence to the CDPP by an investigative agency, and ends with the matter being heard or tried and sentenced, if a decision to proceed with a prosecution is made.

Figure 1.1: The prosecution process for brief assessment referrals

Source: ANAO analysis of information from the CDPP’s Steps in the Criminal Prosecution Process.

1.8 The four initial steps outlined at the top of Figure 1.1 form the pre-brief and brief assessment processes, which are the primary focus of this audit.

1.9 On average, the life cycle5 of all matters completed in 2018–19 was 579 calendar days.6 This includes an average of 116 days spent in the brief assessment phase7, 245 days spent in the court phase (summary hearings, committal hearing, trial and sentencing) and 167 days spent in other phases (appeal or breach).8

1.10 Time spent on pre-brief and brief assessment activities represented 16 per cent of total hours worked by CDPP prosecutors on referrals in 2018–19.9

1.11 Table 1.1 summarises the CDPP’s reported outputs over the period 2014–15 to 2018–19.

Table 1.1: Outputs — Referrals processed, matters dealt with, and prosecutions resulting in a finding of guilt, 2014–15 to 2018–19

|

Year |

Referrals processeda |

Matters before the court |

Defendants dealt with summarily |

Defendants dealt with on indictment |

Cases finalised/ dealt withb |

Prosecutions resulting in a finding of guilt |

|

2014–15 |

3,600 |

4,909 |

1,967 |

737 |

2,704 |

2,156 |

|

2015–16 |

3,252 |

5,011 |

2,302 |

727 |

3,029 |

2,403 |

|

2016–17 |

3,147 |

5,015 |

2,249 |

755 |

3,004 |

2,249 |

|

2017–18 |

2,700 |

4,667 |

1,929 |

788 |

2,721 |

2,187 |

|

2018–19 |

2,579 |

3,961 |

1,315 |

786 |

2,101 |

1,691 |

Note a: Includes arrest, pre-brief, brief assessment and other types of referrals. Processing is defined as a referral being recorded on the CDPP’s case management system.

Note b: The number of cases dealt with is derived from the number of summary, trial and sentence matters closed during the reporting period.

Source: ANAO analysis of information from the CDPP’s annual reports 2014–15 to 2018–19.

1.12 Table 1.1 shows that, in 2018–19, the CDPP reported processing 2,579 referrals, dealing with 3,961 matters before the court, finalising 2,101 cases and obtaining 1,691 convictions. Of the 2,579 referrals processed in 2018–19, 29 per cent were arrest referrals, 49 per cent were brief assessment referrals and 22 per cent were other types of referrals.10

Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth

1.13 The Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth (Prosecution Policy) is the overarching policy guiding the CDPP’s prosecution service, including whether to proceed with a prosecution. The Prosecution Policy is developed and periodically revised by the CDPP, and tabled in Parliament by the Attorney-General. It was first tabled in 1986, and most recently revised and tabled in August 2019. It has two main purposes.

The first is to promote consistency in the making of the various decisions which arise in the institution and conduct of prosecutions. The second is to inform the public of the principles upon which the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions performs its statutory functions.11

1.14 The Prosecution Policy provides tests for the decision to prosecute (refer box). While the basis upon which the decision to prosecute is made must be consistent with the Prosecution Policy, the decision is not ‘a mathematical formula.’ General principles are to be tailored to individual cases.

|

Case study 1. Prosecution tests |

|

Reasonable prospect of conviction test: Once a prima facie case has been established, a decision needs to be made as to whether there is a reasonable prospect of conviction. If an acquittal is more likely than not, the prosecution should not proceed. Evidence must be admissible, substantial and reliable. Prosecutors are told to evaluate a number of factors when making an assessment under this test, including the quality of witnesses, admissibility of evidence such as confessions, and possible lines of defence. Public interest test: Prosecutors must consider whether a prosecution would be in the public interest. They are required to evaluate a number of factors when making an assessment under this test. These include the seriousness of the offence, the need for deterrence, mitigating or aggravating circumstances, the vulnerability of the alleged offender, community perceptions and sentencing options. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth.

1.15 Of 1,263 brief assessment referrals finalised by the CDPP in 2018–19, a decision to proceed with a prosecution occurred in 82 per cent of referrals.12

Organisational structure

1.16 The accountable authority for the CDPP is the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (Director). The Commonwealth Solicitor for Public Prosecutions supports the Director to fulfil her statutory responsibilities and oversees legal practice operations, including preparation and management of cases. The Executive Leadership Group (ELG) is the key advisory group to the Director. The ELG and other key governance groups are examined in detail at paragraphs 2.4 and 2.5.

1.17 The national legal practice is composed of six legal practice groups that are organised around crime types (refer Appendix 3).

1.18 The CDPP’s jurisdiction comprises Australia, its external territories and the Australian Antarctic Territory. The CDPP has offices in Canberra, Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth, Adelaide, Hobart, Darwin, Cairns and Townsville. It prosecutes crimes against Commonwealth laws in the state and territory courts and in the Federal Court of Australia.

Resourcing

1.19 Table 1.2 summarises the CDPP’s resourcing, staffing levels and expenses over the five years to 2018–19.

Table 1.2: Inputs — Funding and staffing, 2014–15 to 2018–19

|

Year |

Appropriationsa ($‘000) |

Revenue from rendering of servicesb ($’000) |

Average staffing levelc |

Prosecution legal costsd ($‘000) |

Total expensese ($‘000) |

|

2014–15 |

79,076 |

5,299 |

396 |

14,852 |

87,099 |

|

2015–16 |

78,299 |

8,284 |

365 |

11,625 |

85,480 |

|

2016–17 |

77,283 |

8,510 |

411 |

12,047 |

85,560 |

|

2017–18 |

77,405 |

7,317 |

379 |

13,196 |

87,647 |

|

2018–19 |

76,482 |

9,692 |

371 |

16,773 |

93,128 |

Note a: Departmental appropriations for the year (adjusted for any formal additions and reductions) recognised as revenue from Government when the CDPP gains control of the appropriation, as per the CDPP annual report Statement of Comprehensive Income.

Note b: Revenue from rendering of services to other Commonwealth agencies under ‘tied funding’ arrangements (refer paragraph 2.14), as per the CDPP annual report Statement of Comprehensive Income.

Note c: Average staffing level as per CDPP annual reports.

Note d: Prosecution legal costs, including external counsel, as per the CDPP annual report Statement of Comprehensive Income supporting note 4B.

Note e: Total expenses, as per the CDPP annual report Statement of Comprehensive Income. Includes legal costs.

Source: ANAO analysis of CDPP information.

1.20 Table 1.2 shows that, in 2018–19, the CDPP received $76.5 million in direct appropriation funding from the Australian Government and $9.7 million from other sources. The CDPP’s Average Staffing Level in 2018–19 was 371. The CDPP expended $93.1 million, including $16.8 million on prosecution legal expenses, which include external counsel costs ($13.2 million).13

Legislative framework and ministerial oversight

1.21 The DPP Act sets out the functions and powers of the Director. The Director delegates functions and powers to CDPP staff.

1.22 The DPP Act provides for separation of the investigative and prosecutorial functions in the Commonwealth criminal justice system. The CDPP has no investigative powers and is detached from the operational activities and decisions of investigative agencies. Prosecution decisions about matters referred to the CDPP for assessment are made independently of the investigative agency.

1.23 The Attorney-General, as First Law Officer, is responsible for the Commonwealth criminal justice system and is accountable to Parliament for decisions made in the prosecution process. Under the DPP Act, the CDPP operates independently of the Attorney-General, subject to any guidelines or directions which may be given by the Attorney-General.14 The CDPP provides updates and briefings to the Attorney-General and Attorney-General’s Department on an as-needed basis. The CDPP outlines its relationship with the Attorney-General on its website.

Operational context

1.24 The efficiency of the CDPP’s operations is, to some extent, dependent on the actions and behaviours of investigative agencies and state and territory courts, as well as of defendants and their representatives. The CDPP has no control over the number of briefs it receives. There is evidence that court systems have been slow to adopt digital technologies and are still heavily paper-based.15 The number and location of court sittings as determined by listing practices, affect the process. Defendants can choose if and when to plead guilty.

1.25 The CDPP can influence some of these circumstances. For example, it can sometimes predict and plan for an upsurge in briefs; as in response to the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry. Its liaison, training and pre-brief work with investigative agencies is aimed at improving the quality of briefs. Prosecution practices, such as timely serving of the statement of facts, or early briefing of senior prosecutors with the authority to negotiate, can encourage early guilty pleas.

1.26 Trying and sentencing complex indictable matters will generally be more time-consuming. The CDPP’s summary convictions, as a proportion of total convictions, decreased from 89 per cent in 2008–09 to 62 per cent in 2018–19, reflecting a general increase in the complexity of cases.

1.27 Both in Australia and overseas, a number of trends have been identified as placing pressure on the speed and efficiency of prosecution services.

- Prosecution services are noting the impact of technological advances in evidence.16 This evidence can be vast and time-consuming to process, assess and present in court.17

- Criminal justice systems are placing increased emphasis on victims’ rights. Victim Impact Statements, referrals to witness assistance services, pre-trial evidence and applications18 and other specialist attention by prosecutors increases the complexity of prosecutions.19

- An increasing proportion of prosecutions involve vulnerable witnesses, such as in domestic and family violence, online child sex offences and human trafficking.20

- Some crime types (including child abuse matters, labour exploitation matters, tobacco importations, fraud, and terrorism) are becoming more complex as criminals adjust their activities in response to law enforcement techniques.21

- New offences have been created and law enforcement priorities can change.22

1.28 There has been less analysis undertaken in relation to any factors facilitating improved speed and efficiency of prosecution services.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.29 The efficiency of the criminal justice system is a matter of public interest. Lengthy court processes can adversely affect witnesses and victims, along with other participants in prosecutions. Efficient and effective Commonwealth prosecution activities increase the likelihood of deterring potential offences against Commonwealth law and regulations, support Commonwealth regulators in enforcing compliance and are essential in maintaining respect for Commonwealth law. How prosecution services are organised; how the decision to prosecute is made; the nature of the relationship between prosecutors and investigative agencies; and the way prosecutors operate within the court system, influence overall efficiency.

1.30 Undertaking an audit of the case management efficiency of the CDPP also addresses Parliamentary interest. The topic was included in the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit’s list of audit priorities for 2018–19, with a request that the audit include prosecutions by the CDPP of corporate crimes, with a specific focus on matters referred to the CDPP by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.31 The audit objective is to examine the efficiency of the CDPP’s case management. The audit examines the extent to which the CDPP uses its resources efficiently in evaluating referred matters.23 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Does the CDPP have arrangements to support the efficient assessment of referred briefs?

- Does existing performance data indicate that the CDPP assesses briefs efficiently?

- Is the CDPP effectively monitoring and reporting on its case management performance?

1.32 This audit is focused on the pre-brief and brief assessment phases of the CDPP’s work (as outlined in red in Figure 1.1).

Audit methodology

1.33 This audit applied ANAO’s methodology for auditing efficiency. Efficiency is defined as ‘the performance principle relating to the minimisation of inputs employed to deliver the intended outputs in terms of quality, quantity and timing.’24

1.34 The methodology included identifying relevant inputs and outputs and appropriate performance measures; drawing on data; identifying suitable comparators to benchmark against; and identifying key operational processes that are used to transform inputs into outputs.

1.35 Specific audit procedures undertaken included review of documentation and systems relevant to the CDPP’s case management; analysis of data extracted from the CDPP’s case management systems; and interviews of CDPP staff and investigative agencies.

1.36 ANAO’s findings and conclusions are based in part on available data within CDPP’s case management systems. The quality and availability of this performance data influences both the kinds of analyses that can be conducted and the conclusions that can be drawn.

1.37 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $519,200.

1.38 The audit team was Christine Chalmers, Judy Jensen, Zoe Pilipczyk, Danielle Page, and Paul Bryant.

2. Arrangements to support the efficient assessment of briefs

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Office of the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) has arrangements to support the efficient assessment of referred briefs. This includes an examination of whether the CDPP has appropriate governance arrangements; processes for engaging with investigative agencies; systems; and operational policies, procedures and practices.

Conclusion

The CDPP has established key elements to support the efficient assessment of briefs. Governance structures are appropriate and investigative agency engagement largely supports the objective of improving brief quality. Case management systems and digital processes are developing and operational guidelines are extensive. While the average timeframe for the completion of assessments is 78 days, which is consistent with the CDPP’s target, there are inefficiencies in the administration of key activities within the assessment workflow. Management reporting does not provide sufficient visibility over key drivers in efficient brief assessment practice.

Areas for improvement

ANAO made one recommendation in relation to supervisor visibility of brief assessment efficiency drivers.

Suggestions for improvement included developing an overarching engagement strategy; accepting arrest referrals via the Digital Referrals Gateway; and providing prompt acknowledgements to investigative agencies.

2.1 In order to examine this criteria, the audit investigated:

- governance arrangements — including frameworks and policies, risk management processes and financial management processes, which are the key structures supporting the CDPP’s case management;

- policies and practice in relation to stakeholder engagement — focusing on engagement frameworks, policies and practices for investigative agencies, which are a key influence on CDPP brief assessment efficiency;

- IT systems — including the CDPP’s core case management system, caseHQ; its brief submission channel, the Digital Referrals Gateway; litigation databases to support evidence analysis; and practices with respect to digital capability. These systems and practices are major levers for achieving greater case management efficiency; and

- case management operational guidelines and practice — the way in which prosecutors and administrators use systems, and interpret and comply with policy, will affect case management efficiency.

Does the CDPP have appropriate governance arrangements to support its case management process?

The CDPP has an appropriate governance structure. Governance frameworks include clear accountabilities, processes for oversight, delegated decision-making and systems for risk management. For 2019–20, the CDPP established budgets at the practice group level for key expense items.

Governance framework and policies

2.2 The CDPP’s approach to governance is articulated in a Governance Policy and Framework. The Framework identifies the Director of Public Prosecutions Act 1983 and the Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth (Prosecution Policy) as fundamental to the prosecution process. Roles and accountabilities are detailed in a Governance Accountability Matrix.

2.3 Following a strategic review in 2013, in June 2014 the CDPP was restructured into specialist legal practice groups supported by a Corporate Services Group (refer Appendix 3). The new structure represented a shift away from a regionally based legal practice to a national practice segmented by crime type.

2.4 The Executive Leadership Group (ELG) comprises the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (Director) as chair, the Commonwealth Solicitor for Public Prosecutions (CSPP), the Chief Corporate Officer, and five deputy directors who lead the specialist legal practice groups. The ELG’s role is to provide advice regarding strategic direction, oversee the business, identify and manage strategic and operational risks, and manage budget and resources. The ELG meets monthly.

2.5 A Project Board meets monthly to provide oversight of projects and reports to the ELG quarterly. Other steering and operational committees are established as required. The supporting committees function in an advisory role to the Director.

2.6 The CSPP’s role includes improving the efficiency and effectiveness of legal practice operations and is supported by a Legal Business Improvement (LBI) branch. LBI’s activities are aimed at enabling, supporting and modernising the legal practice. A National Business Improvement (NBI) practice group has also been established with the aim of fostering innovation and business improvements across the legal practice, particularly regarding digital capability.

2.7 In most instances, decision-making processes are devolved to the deputy directors, branch heads or prosecution team leaders. Some decisions remain with the Director under statute or under a Decision-Making Matrix (DMM) that was developed to identify and guide the appropriate decision-maker (refer paragraph 2.54); for example, decisions in relation to appeals are made by the Director.

2.8 The Corporate Services Group has responsibility for monitoring and reporting on governance across the CDPP.

2.9 Each practice group develops an annual action plan structured according to the CDPP’s strategic themes of: ‘providing an efficient and effective prosecution service delivery’, ‘engaging with partner agencies and stakeholders’, and ‘investing in our people.’

Risk management

2.10 The CDPP has a Risk Management Framework (Risk Framework) and Policy to assist the Director to meet the requirements of subsection 16(a) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy. The Director is ultimately accountable for the management of risk.

2.11 The CDPP articulates its risk posture in its Risk Appetite and Tolerance Statement, last reviewed in June 2019, and embeds risk management practices through its practice group action plans. A Risk Management Process Guideline assists staff to assess and manage risk.

2.12 A Strategic Risk Register and Management Plan, and a Corporate Services Risk Register are maintained. The registers cover risk identification, analysis, planning and monthly progress updates. The register includes efficiency-related risks associated with funding, change management, IT strategy and liaison with investigative agencies. For each of the strategic risks identified, there is a control owner who has responsibility for developed treatments to manage the risk.The ELG and Audit Committee have a standing agenda item to review the risk registers.

2.13 Internal audit ties its activities to strategic risks. Internal audit performed a review of CDPP’s Risk Framework in February 2019. The audit concluded that CDPP’s suite of risk management guidance material is appropriate in the circumstances and aligned to the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy and other better practice guidance, but that the CDPP should ensure that guidance materials reflect actual practice, refresh its strategic risks and make functionality improvements to the risk register template. Throughout 2018–19, the ELG conducted risk workshops to identify and refine strategic risks.

Financial management

2.14 The CDPP’s operations are primarily funded through parliamentary appropriations, but the CDPP also receives revenue through transfers of appropriations from other entities to cover the cost of prosecutions for offences under specific legislation. These activities are governed by six memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with Commonwealth investigative agencies25, including four signed in 2018 and 2019. In 2018–19, revenue recognised under these ‘tied funding’ arrangements was $9.2 million. Tied funding increased from four per cent of all funding in 2014–15 to 11 per cent in 2018–19.

2.15 The Strategic Risk Register states that the CDPP’s highest priority risk is ‘Inadequate core funding’, specifically:

Significant reliance on funding based on terminating and ‘tied’ budget measures leads to funding uncertainty, ‘fiscal cliffs’ and seesawing in recruitment, ultimately impacting prosecution outcomes.

2.16 This risk has an ‘Extreme’ rating, based on a ‘Severe’ impact and ‘Possible’ likelihood. Treatment measures focused on contributing to investigative agency new policy proposals with the aim of obtaining related funding, reducing the level of cross-subsidisation of this work, and ‘improvements to budgeting and forecasting, leading to improved long term decision-making.’

2.17 The CDPP’s budget is managed centrally by its Corporate Services Group. Between 2014–15, when the national practice model was established, and 2018–19, budgets were allocated at the national level only. As a result, the CDPP were unable to track costs at the legal practice group level or below. In 2018–19, practice group budgets for a range of key expense items, such as employee, legal and travel, were proposed, ‘with the aim of improving financial management and decision-making, leading to more informed financial strategies and priority setting.’ In 2019–20, budget management will be undertaken for four business areas — executive, legal practice, corporate, and administrative support. This will improve the CDPP’s ability to analyse costs.

Do the CDPP’s processes for engagement with investigative agencies support the efficient assessment of briefs upon referral?

The CDPP’s processes for engagement with investigative agencies largely support the efficient assessment of briefs upon referral. Agency engagement is a core focus of strategic planning and case management practice, and systems and tools have been developed for this purpose. Stakeholder satisfaction with CDPP engagement is improving, on average. In practice, the nature and extent of liaison activities vary between investigative agencies and there is no overarching engagement strategy.

Engagement strategy

2.18 The National Legal Direction26 (NLD) ‘Prosecution services for partner agencies’ outlines the CDPP’s stakeholder relationship activities. This document notes that ‘Strong relationships between the CDPP and investigative agencies is fundamental to the efficient and effective delivery of prosecution services to agencies and the Australian community.’

2.19 The NLD is supported by a communications strategy; one of three pillars of which is ‘advise to support.’ The CDPP’s Corporate Plan 2019–2023 names ‘effectively engage with partner agencies and stakeholders’ as the second of three strategic themes.

2.20 A key objective of the legal practice group model was to match the way in which investigative agencies were organising themselves and their work, potentially leading to greater ‘responsiveness’ from the CDPP in brief assessment and advice. Objectives included greater consistency of services across regions; services and products being generated out of a practice group and used nationally; and national liaison meetings with investigative agencies.

Engagement policies, procedures and resources

2.21 Policies and resources that are used to engage with investigative agencies comprise:

- Brief specific activities — pre-brief advice; templates; Partner Agency Portal (Partner Portal); and

- Ongoing liaison structures and processes — MOUs; liaison activities; an investigative agency satisfaction survey and a feedback loop.

Brief specific activities

Pre-brief advice

2.22 The rationale for pre-brief advice is to improve the quality of briefs prepared by investigative agencies and, more generally, to improve the prosecution process. Pre-brief services involve liaison with investigative agencies to inform investigators’ operational decision-making and evidence gathering, prior to the brief being provided to the CDPP for assessment. Pre-brief advice also aims to improve the operational efficiency of investigative agencies.

Templates

2.23 A number of templates with the intention of streamlining brief assessment processes have been developed for use by the CDPP and investigative agencies. The CDPP has also worked with a number of agencies to develop tailored electronic brief (e-brief) templates.

Partner Agency Portal

2.24 An online Partner Portal has been established to give investigative agencies access to various information and resources27, including the Digital Referrals Gateway, which has been established for the submission of e-briefs (refer paragraph 2.43). The CDPP has advised ANAO that there are 719 active28 Partner Portal users from 62 different Commonwealth and state and territory agencies. In 2018, according to a survey of investigative agency representatives conducted by the CDPP, 42 per cent used the Partner Portal, and almost half agreed ‘strongly’ that ‘the information provided through the Partner Portal is of high value to, and used by, my agency.’

Ongoing liaison structures and processes

Memoranda of Understanding

2.25 Relationships between the CDPP and some agencies are formalised through an MOU. Clarity around practices through MOUs — for example, authority for some agencies to conduct some summary prosecutions themselves — is aimed at minimising duplication of effort and wasted resources.

2.26 The CDPP signed MOUs with 21 agencies between 1992 and 2019, including with some of its largest referrers (refer Appendix 4). However, most investigative agencies do not have an MOU with the CDPP. Only the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) MOU (signed in February 2017) makes reference to specific brief assessment timeliness targets. Some recent MOUs for tied funding — for example, the MOU signed with the Department of Home Affairs in May 2019 — make no provision for timeliness.

Liaison activities

2.27 Investigative agency liaison activities are strongly emphasised by the CDPP. Potential liaison activities are set out in an NLD ‘Prosecution services for partner agencies’, and training activities are also outlined in an NLD. Practice group leaders must report to the ELG about their liaison activities each quarter. MOUs with some investigative agencies set out the parameters for liaison. In 2018–19 and 2019–20 practice group action plans, several groups list ‘targeted training’ with investigative agencies as a key action.

2.28 In practice, arrangements for, and frequency of, liaison differ across practice groups and agencies. Liaison meeting minutes suggest that relatively few liaison meetings are held with the state and territory police, despite police being one of the largest referrers overall. State and territory police referrals are dispersed across different police stations and investigative areas; this complicates liaison due to multiple liaison contact points.

Investigative agency satisfaction survey

2.29 Since 2016, a biennial investigative agency satisfaction survey has measured satisfaction with the CDPP. One rating question is used as a performance criterion in the CDPP’s annual performance reporting (refer paragraph 4.41). Free text questions give surveyed investigative agencies the opportunity to provide qualitative feedback. The next survey is due in 2020.

2.30 Results from 2016 and 2018 satisfaction surveys indicate that the vast majority of respondents were satisfied (83 per cent in 2016, 87 per cent in 2018) with their level of engagement with the CDPP. Between 2016 and 2018, there was a large increase in respondents ‘strongly agreeing’ that the CDPP has an effective working relationship with agencies (refer Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Agreement that the CDPP ‘has an effective working relationship with my agency through liaison arrangements’ by investigative agency

Note: AFSA refers to Australian Financial Security Authority. AFP refers to Australian Federal Police. ASIC refers to Australian Securities and Investments Commission. State Police refers to state and territory police. ABF refers to Australian Border Force. Only respondent samples of at least n=5 are shown; 2016 AFSA results are not shown due to insufficient sample size. In 2016, zero per cent of ASIC and State Police respondents strongly agreed.

Source: ANAO analysis of 2016 and 2018 investigative agency satisfaction surveys.

Feedback loop

2.31 Feedback to agencies is obtained through prosecution reports, post-trial reports, and case reviews for some significant matters. Some agencies have indicated dissatisfaction with the timeliness of reports.

2.32 Ad hoc initiatives may be developed with agencies that are specifically aimed at increasing efficiency, such as engagement frameworks29 or ad hoc reports. There are two engagement frameworks in place, with ATO and Comcare. Ad hoc reports are designed to keep agencies informed of on hand matters, but reporting practice varies across agencies. Several major referring agencies have a centralised email drop-box arrangement with the CDPP for ‘lessons learnt.’ There is evidence that drop-boxes are being used inconsistently.

2.33 The reasons for the CDPP’s differing approaches to the establishment of MOUs, composition of MOUs and conduct of liaison activities are unclear. The CDPP should establish an overarching engagement strategy.

Do the CDPP’s systems support the efficient assessment of briefs?

The CDPP has systems which can support the efficient assessment of briefs. Case management systems are developing and embed decision-making workflows. Digital practices and associated systems have been established to encourage the submission of e-briefs, which facilitate efficient case management and evidence analysis. A management reporting system enables analysis of brief assessment volumes and statistics.

2.34 The systems that support the CDPP’s assessment of briefs are divided into two categories.

- Case management and monitoring systems — case management systems (caseHQ and its precursor system, the Case Recording Information Management System (CRIMS)); the Effort Allocation Tool (EAT) utilised for time recording; SharePoint30 utilised for records management; and the PowerBI31 system used to monitor case management.

- Digital practices and associated systems — the Digital Referrals Gateway used for investigative agencies to refer e-briefs; litigation databases used by prosecutors to support evidence analysis; and digital education and training processes.

Case management and monitoring systems

2.35 The CDPP launched caseHQ on 29 August 2018, replacing CRIMS, which was deemed no longer fit-for-purpose. caseHQ introduced functionality that improves case management and monitoring processes, including workflow, records management, performance monitoring and governance.

2.36 Many case management workflow and decision tasks are embedded into caseHQ. ‘Workflow tasks’ guide case officers through the brief assessment and prosecution process. ‘Decision tasks’ are directed to senior prosecutors to review and approve recommendations made by case officers.

2.37 The system provides a history of actions taken and documents created for a matter. This has improved internal transparency. caseHQ has the functionality to manage requisitions32 and investigative agency communications but it is not used in this way currently.

2.38 Mandatory Prosecution Policy Declarations (PPDs) — which aim to provide assurance that the prosecution team have complied with the Prosecution Policy — are automatically added to the decision-maker’s workflow. The completion of a PPD in caseHQ is required to progress the matter to the next phase in the prosecution process (refer paragraph 4.45).

2.39 Time spent on specific referrals is recorded as a percentage of a standard working day (seven hours, 21 minutes).33 EAT — a time recording system in place since 2012 — is now integrated with caseHQ for data entry, improving time recording functionality. caseHQ links all matters that CDPP officers have worked on to EAT.34 However, caseHQ is not directly or indirectly linked with the CDPP’s financial management system, TechnologyOne.35 This makes it difficult to attribute costs to specific referrals, impeding cost analysis.

2.40 Since the introduction of caseHQ, the CDPP has used SharePoint (a document management system integrated with caseHQ) as its electronic records management system. caseHQ and SharePoint provide national access to files and document version control.

2.41 PowerBI is used to visualise case management data and has partially replaced SQL-generated reports. PowerBI has the functionality to improve the CDPP’s case management oversight by providing current information in a user-friendly format. This is examined in more detail at paragraph 2.78.

Digital practices and associated systems

Digital Referrals Gateway

2.42 An investigative agency brief to the CDPP is composed of two parts: covering36 and evidentiary material. Working with hard copy evidentiary material requires the CDPP to undertake manual processes. Efficiencies are realised when both covering and evidentiary material are submitted to the CDPP electronically.37 e-briefs allow the CDPP to use litigation support software to index, sort and analyse evidence.

2.43 The Digital Referrals Gateway (Gateway) was established in 2017–18 for investigative agencies to securely submit and update e-briefs. The Gateway improves efficiency by pre-populating some covering material, and allows for monitoring and faster allocation of briefs received. An automated notification of receipt is sent to the investigative agency. The Gateway is not integrated with caseHQ, which would add further efficiencies, but there are plans to integrate in the future.

2.44 e-brief Referral Guidelines issued to investigative agencies state that ‘all briefs referred to the CDPP should be in electronic format as an e-brief.’ For some agencies (for example, the ATO), the use of e-briefs is mandatory under service level agreements. However, there is mixed uptake of the Gateway across investigative agencies. The CDPP was unable to provide accurate data on the volume of briefs submitted on paper, as an e-brief via the Gateway or in other electronic form, but has stated that AFP, ABF, state and territory police, and ATO did not use the Gateway in 2018–19, and that less than 20 per cent of ASIC briefs were submitted via the Gateway.

2.45 Several factors contribute to non-use of the Gateway.

- Arrest referrals comprise almost one third of referrals handled by the CDPP; however, the Gateway is not used for arrest referrals. The CDPP indicates that this is because there is typically no brief produced on the day of arrest and arrest matters can involve a large volume of evidentiary material, for which the Gateway is not suitable.

- The Gateway only accepts evidence briefs up to one gigabyte (GB) in size. Most ASIC, AFP, ABF and state and territory police briefs exceed this size. The CDPP states that it plans to increase the upload capacity to four GB in order to increase usage of the Gateway.

2.46 The CDPP should expand the Gateway to arrest matters given there is a strong efficiency rationale for submitting both covering and evidentiary material for all matters via the Gateway.

Digital litigation systems

2.47 The CDPP utilises a suite of internally developed litigation databases to assist with the analysis of large volumes of evidentiary material. Since 2016, the CDPP has made these databases available to prosecutors for higher complexity briefs.

2.48 In 2018–19, CDPP prosecutors used litigation databases for 36 matters.38 In 26 of these matters, the prosecution team ceased using the database, indicating it was not fit-for-purpose. It is noted that current databases rely on evidence being indexed in an Excel spreadsheet, and that the CDPP uses three types of MS Access databases, which requires staff to understand which option is appropriate for their matter.

2.49 To address some of these issues, the CDPP has commenced procuring a cloud-based digital litigation system that is specifically designed to index and visualise legal evidence and will not require the same level of configuration as previous litigation databases.

2.50 To promote uptake amongst prosecutors of current litigation databases, automated emails are sent to case officers responsible for higher complexity matters, advising them of available digital tools and services.

Digital education and training

2.51 The CDPP’s THINK DIGITAL strategy (launched in November 2017) attempts to build digital capability amongst CDPP staff. The CDPP established a Digital Capability Team in September 2018 to promote digital practice. Over sixty internal training sessions were delivered between November 2018 and June 2019, with up to 800 attendances. The CDPP makes written and video training materials available to staff via its intranet.

Are the CDPP’s operational policies and procedures designed to support the efficient assessment of briefs?

The CDPP’s operational policies and procedures are designed to support the efficient assessment of briefs. The CDPP has a large volume of operational guidelines and policies to support brief assessments and prosecutions. The CDPP is rationalising and digitising these materials, and some are embedded in the case management system, caseHQ.

2.52 The CDPP uses the Prosecution Policy; a Decision-Making Matrix; National Legal Directions; Practice Group Instructions; National Offence Guides and a recently approved Practice Management Guide to support the brief assessment and case management process.

Prosecution Policy

2.53 The Prosecution Policy is the overarching policy guiding the CDPP’s prosecution service. All decisions relating to the prosecution of Commonwealth offences must be made with reference to the Prosecution Policy (refer paragraph 1.13). The prosecution tests include decisions which inherently support efficiency objectives in the assessment of briefs — the ‘reasonable prospect of conviction test’ aims to prevent resources being allocated to the pursuit of cases that do not have a reasonable prospect of success. The ‘public interest test’ includes ‘the likely length and expense of a trial’ as one of the decision factors.

Decision-Making Matrix

2.54 The DMM supports case officers in determining the appropriate decision-maker39 for key decisions in the brief assessment and prosecution process. The DMM aims to maximise the efficiency of the brief assessment process by delegating decisions to the lowest possible level within the organisation as has been deemed reasonable for that decision. In August 2018, the DMM was embedded into caseHQ.

National Legal Directions

2.55 NLDs are national policies developed for the legal practice. The CDPP has produced over 35 NLDs since 2014 on topics such as witness policies, forensic procedures, sentencing, parliamentary issues and external counsel. These are available to staff via the CDPP’s intranet. Four NLDs have particular relevance to case management efficiency.

- ‘Complexity ratings’, last updated in March 2019, provides guidance on classifying referrals based on a scale from one to four of complexity (refer Appendix 5). Complexity classification is used for specifying decision-making authority in the DMM, determining the necessary frequency of case review, establishing reasonable prosecutor workload, and generating funding estimates for new policy proposals.

- ‘Timely prosecutions’, published in October 2018, sets out the key activities that facilitate timeliness and identifies the target duration for brief assessment and filing indictments.

- In ‘Early Resolution Scheme’, published in 2016, the CDPP recognises that early resolution of matters (typically through an early guilty plea) is an efficiency gain for the entire justice system by negating the need to go to a contested trial. The NLD lists strategies and specific activities to achieve early resolution. These are also referenced in a new Practice Management Guide. Prosecutors are advised to ‘take active steps to attempt to resolve the matter at every subsequent stage of the prosecution, including right up to the commencement of the summary hearing or trial.’

- A ‘Briefing Counsel Policy’ sets out when, who, the steps involved in and how to brief external counsel, with the aim of maximising value-for-money. A ‘Nomination of Counsel’ system also supports the use of external counsel.

Practice Group Instructions

2.56 Practice Group Instructions (PGIs) are protocols for staff working in a specific practice group. The CDPP has 45 PGIs accessible to staff via the CDPP’s intranet. Some PGIs provide guidance about procedure — for example, filing or evidence-handling. Several PGIs have an implicit or explicit value-for-money or efficiency focus. For the most part, PGIs are concerned with issues of law, such as sentencing and charging. A 617-page Federal Prosecution Manual and a series of Guidelines and Directions Manuals are being phased out and replaced with NLDs and PGIs.

National Offence Guides

2.57 National Offence Guides (NOGs) are used by prosecutors and investigative agencies to settle the elements of an offence and draft charges. NOGs aim to facilitate efficient brief assessment by providing guidance to investigative agencies and CDPP case officers. NOGs are made available to investigative agencies on the Partner Portal. Several investigative agencies responding to the 2018 survey and in interviews conducted by ANAO indicated that NOGs are valued.

Practice Management Guide

2.58 A new Practice Management Guide was approved by the ELG in September 2019. This covers file management, external communications, templates and guides, managing investigative agency relations, early resolution activities, and practice management tools.

Are the CDPP’s operational practices supporting the efficient assessment of briefs?

The CDPP’s operational practices partly support the efficient assessment of briefs. The average timeframe for the completion of assessments is 78 days. Although this is consistent with the CDPP’s target of 85 per cent completed within 90 days, there are inefficiencies in relation to the assignment of briefs to branches and work groups; lack of initial triage for early identification of critical deficiencies in evidence that may prevent or delay a timely assessment; inconsistent follow-up with investigative agencies after the issuing of requisitions for additional evidence; and inconsistent records management practices. Management reporting does not allow supervisors to fully monitor and act on deficiencies in brief assessment practice in order to ensure efficiency in these areas.

2.59 The brief assessment workflow, including timeliness targets, involves four key stages.

- Brief receipt and assignment — once the brief has been referred by the agency, an administrative officer must upload the brief to caseHQ. The officer will then allocate the matter to a branch. The branch head must assign a complexity level and allocate it to a work group. The Prosecution Team Leader (PTL) will then assign the matter to a case officer. The agency will be notified. These activities are to occur within four days of brief receipt.40

- Triage — an initial analysis of the brief is to be done by the case officer with the aim of flagging critical deficiencies in the evidence that may prevent or delay a timely assessment. Should a deficiency be found, the case officer is required to issue a requisition — a request for additional evidence or clarification — to the investigative agency. Triage is to be conducted within 10 days of brief receipt.

- Brief assessment, requisition and recommendation — once the case officer begins the assessment of the brief in full, they may continue to submit requisitions to the agency until the brief of evidence is sufficient to make a recommendation about whether to prosecute. From the moment a requisition is issued until a response is received, the officer should ‘suspend’ the measurement of timelines associated with the matter in caseHQ.41 The case officer’s recommendation about whether to proceed with the prosecution is to be made within 83 days of brief receipt, excluding suspensions.42

- Prosecution Policy Declaration — A PPD should be completed by the decision-maker to indicate that the Prosecution Policy has been complied with. The PPD should be signed within 90 days of receipt of the brief assessment referral, excluding suspensions.

2.60 Figure 2.2 provides an overview of the brief assessment workflow.

Figure 2.2: CDPP brief assessment workflow

Note: Target timeframes shown exclude any periods of suspension.

Source: ANAO analysis of CDPP information.

2.61 To examine brief assessment in practice, the audit conducted an analysis of timeframe data for all 2018–19 completed brief assessments recorded in caseHQ and CRIMS.43 A separate analysis focussed on the population of 2018–19 matters in the upper quintile for duration at each complexity level (henceforth referred to as ‘old matters’)44, and a qualitative analysis was conducted of a sample of old matters.45

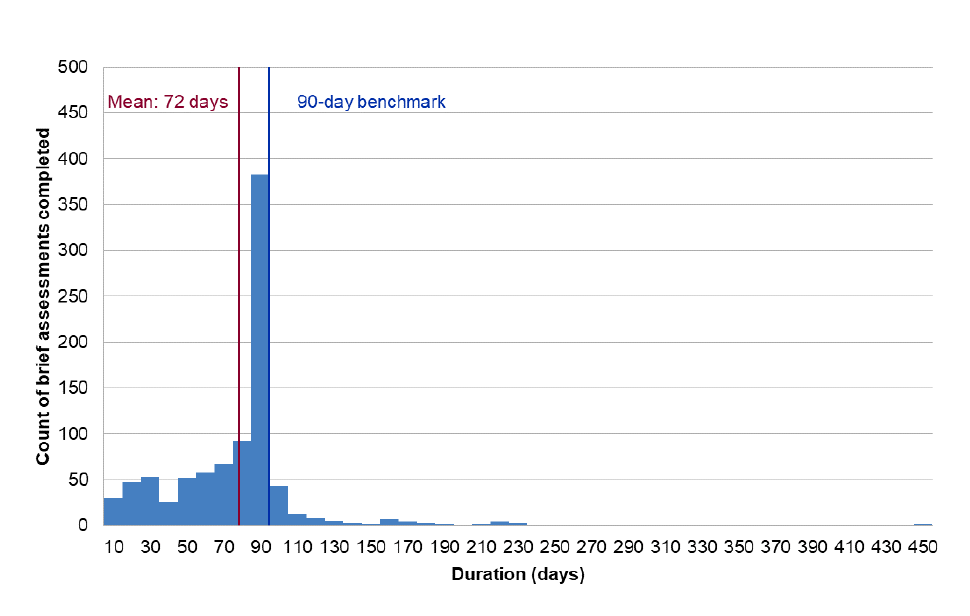

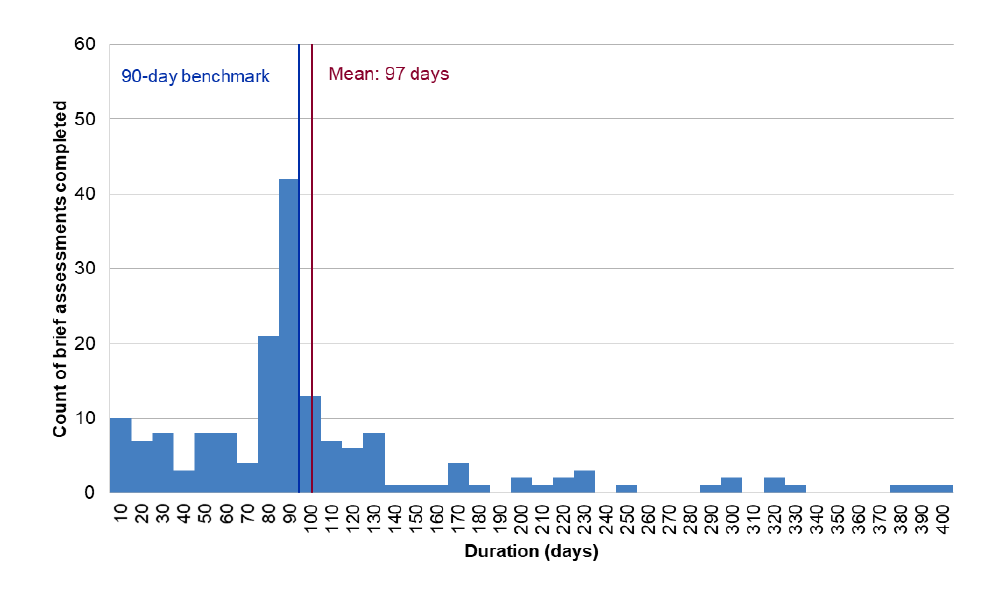

2.62 Figure 2.3 shows the distribution of brief assessment duration in days in 2018–19.

Figure 2.3: Distribution of brief assessment matter duration, 2018–19

Note: Includes brief assessment matters completed in 2018–19.

Source: ANAO analysis of caseHQ and CRIMS data.

2.63 While 85 per cent of brief assessments were finalised within 90 days (consistent with the CDPP’s target), Figure 2.3 indicates that the average timeframe required was 78 days, with 36 per cent completed within 80 to 90 days. Once commenced, the average time recorded to complete a brief assessment in 2018–19 was 27 hours.46

2.64 Table 2.1 shows timeliness results for each of the workflow steps described earlier in Figure 2.2.

Table 2.1: Timeliness of brief assessment workflow steps, 2018–19

|

|

|

All matters |

Old matters |

||

|

Activitya |

Target |

Completed within target (%) |

Average duration |

Completed within target (%) |

Average duration |

|

Allocated to branch |

24 hours |

100 |

<1 day |

100 |

<1 day |

|

Assigned complexity |

2 days |

71 |

4 days |

67 |

6 days |

|

Allocated to work group |

2 days |

69 |

3 days |

58 |

4 days |

|

Case officer assigned |

3 days |

58 |

6 days |

52 |

8 days |

|

Agency notified |

4 days |

59b |

11 days |

48 |

11 days |

|

Triage durationc |

10 days |

32 |

32 days |

28 |

47 days |

|

First requisition issuedd |

N/A |

N/A |

60 days |

N/A |

78 days |

|

Suspension duratione |

N/A |

N/A |

80 days |

N/A |

91 days |

Note a: All analyses, except suspension duration, on caseHQ matters completed in 2018–19.

Note b: Includes only those matters with a completed agency notification in caseHQ.

Note c: The number of days between the start and end of triage, as recorded in caseHQ. Includes only those matters with a reported triage completion date.

Note d: Duration shown is the elapsed time in days between receipt of the brief assessment referral and issuing of the first requisition (request for clarification or additional evidence) to the investigative agency for caseHQ matters.

Note e: Duration shown is the elapsed time between the start and end of a suspension after a requisition is issued. Includes only caseHQ and CRIMS matters where a requisition was issued.

Source: ANAO analysis of caseHQ and CRIMS data.

2.65 Table 2.1 shows that delays occur at early steps in the workflow process — brief assignment, triage and requisitions — although overall duration is within the benchmark of 90 days.

Brief receipt and assignment

2.66 The workflow requires that branch allocation be completed within 24 hours, work group allocation and complexity assignment occur within two days, a case officer be assigned within three days and agency notification be completed within four days of a brief being received.

- Branch allocation — analysis of all caseHQ brief assessment referrals completed in 2018–19 shows that allocation to a branch by an administrative officer almost always occurs within 24 hours of receipt of the brief.

- Assigning complexity — average duration for complexity classification was four days for caseHQ brief assessment referrals completed in 2018–19 (six days among old matters).

- Allocating work group — 69 per cent of completed caseHQ matters were allocated to a work group within two days. On average, this occurs three days after receipt of the brief (four days for old matters). These delays were most significant for ASIC.

- Assigning a case officer — 58 per cent of caseHQ brief assessment referrals completed in 2018–19 were assigned a case officer within three days, with the average timeframe being six days. Delays in allocating a case officer were greater for old matters (eight days).

- Agency notification — for caseHQ matters, the agency notification date was recorded 63 per cent of the time. For matters where the date was recorded, the average length of time between matter receipt and acknowledgement to the agency was 11 days and old matters had a similar delay. Qualitative analysis of old matters showed inconsistent practices with respect to agency notification.

2.67 The CDPP should ensure that when investigative agencies submit a brief, this is acknowledged in writing within a reasonable timeframe, and that acknowledgements include information about the assigned case officer and the 85 per cent within 90 days service standard.

Triage

2.68 According to the workflow, triage should be completed within 10 days of referral.

- Approximately 80 per cent of caseHQ matters completed in 2018–19 had a triage completion date recorded. Where a date was entered, the average duration between receipt of the brief and completion of first triage was 32 days for all completed caseHQ matters, and 47 days for old matters.

- Qualitative analysis of old matters found limited evidence that case officers were using the triage stage to get verbal briefings from investigative agencies. In a June 2019 ELG communication to staff, workshopping was recommended at the triage stage; however there was no evidence that this is occurring.

Brief assessment, requisition and recommendation

2.69 On average, brief assessment matters were completed within 78 days; 128 days for old matters. Although the benchmark was met, there were lengthy intervals before the first requisition was issued, especially in old matters, and personnel changes often occurred late in the workflow.

Requisitions and suspensions

2.70 A requisition was issued in 48 per cent of all caseHQ and CRIMS matters completed in 2018–19, and in 53 per cent of old matters.47

2.71 The average length of time between brief receipt and the issuance of a requisition for 2018–19 caseHQ matters (where a requisition was issued) was 60 days, and among old matters was 78 days. The average time for the first requisition to be issued in ASIC matters was 10248 days.

2.72 When requisitions are sent, case officers are authorised to ‘stop the clock’ and suspend the matter. Analysis indicates that the length of a suspension impacts duration, even after excluding the period of suspension itself. This suggests that the longer the period of suspension, the less timely the brief assessment. The average duration of combined suspensions for 2018–19 completed caseHQ and CRIMS brief assessment matters was 80 days (91 days for old matters).49

2.73 During suspension periods, case officers are expected to follow up with agencies, however there is no incentive for case officers to speed up agency response, and no method of assuring that follow-up occurs. Qualitative analysis of old matters suggested inconsistent investigative agency follow-up.

Transfer and reallocation

2.74 Thirty eight per cent of completed 2018–19 caseHQ brief assessment matters (52 per cent of old matters) had a change in case officer. A change in case officer was associated with a longer duration (70 days on average, compared to 59 days where the case officer remained the same). The CDPP has put in place several strategies to help mitigate disruption caused by case officer change, including litigation plans and team-based working. Transferring matters between offices and officers is considered by the CDPP to be an important strategy in minimising backlog. There was evidence of this occurring in qualitative analysis of old matters, but sometimes not until the 90-day deadline was approaching or had passed.

Information management and monitoring

2.75 Analysis identified general observations in relation to information management, record keeping and workflow monitoring.

2.76 When briefs are reallocated, inefficiencies can occur when new case officers need to familiarise themselves with the brief of evidence, and can be exacerbated where there is poor record keeping by the original officer. Upon the introduction of caseHQ, case officers were instructed to maintain electronic documents in SharePoint rather than on disparate hard drives on the CDPP network. Hard copy documentation is now discouraged, except where required by the courts. The ANAO’s qualitative analysis of old matters found inconsistencies across matters and case officers in record keeping, including requests for and responses to requisitions. Further, when correspondence was filed, it was sometimes done so months after the communication occurred.

2.77 Lack of file notes about reasons for delay was evident in qualitative analysis of old matters. In September 2019, the ELG approved a new Practice Management Guide that states the importance of maintaining accurate records of significant internal and external communications.