Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Capability Development Reform

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Defence’s implementation of reforms to capability development since the introduction of the two-pass process for government approval of capability projects and government’s acceptance of the reforms recommended by the Mortimer Review. The scope of this audit included the requirements phase and, to a limited extent, the acquisition phase of major capability development projects, focusing upon changes flowing from the major reforms.

Summary

Introduction

1. To protect and advance Australia’s strategic interests, Defence prepares for and conducts naval, military and air operations and other tasks as directed by the government of the day.1 Developing and maintaining the capability to carry out these operations and tasks is a central and ongoing responsibility for Defence. The implications for Defence of the Government’s strategic requirements, articulated in a Defence White Paper, are analysed and, among other things, lead to a series of projects to be programmed through the capability development process.2 Capability development generally results in the acquisition of new or upgraded capital equipment, and Defence must ensure that the equipment and all the other prerequisites to a functional capability are available to the Services for operational use when needed.3

2. Capability systems are generally expensive and require upgrade or replacement over time to allow the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to maintain and improve its capability while keeping pace with changes in the threat environment. Defence defines its capability needs in the light of the strategic thinking set out in the latest Defence White Paper. The Australian Government released the Defence White Paper 2013 on 3 May 2013.4 An earlier announcement had indicated that the Government expects to upgrade or replace up to 85 per cent of the ADF’s equipment over the next 15 years at a cost to the Commonwealth of up to $150 billion over the next decade alone.5 The Defence Portfolio Budget Statements 2013–14 outline planned Defence Capability Plan (DCP) expenditure of $8310 million for that year and over the Forward Estimates.

3. Generally, there are long lead times involved in delivering Defence capability, and many years may elapse from the point where a capability gap is identified to the delivery of a new or upgraded system into regular service. When projects are delayed, run into difficulties or, as sometimes happens, fail altogether, the consequences are serious: these include the likelihood of a gap in ADF capability developing or persisting, and a poor return on a generally substantial public investment.

4. Concerns over Defence’s ability to deliver capabilities on time and on budget to specified technical requirements has caused successive governments and ministers to initiate reviews of the organisation’s management of capability development. One of the most substantial reforms arising from these reviews has been two-pass government approval for major capability development projects, originally introduced as a result of the Defence Governance, Acquisition and Support Review in 2000. Two-pass approval was intended to give government greater control over capability development.

5. The Defence Procurement Review, chaired by Mr Malcolm Kinnaird AO (the ‘Kinnaird Review’), followed in 2003. This review recommended strengthening the two-pass process and led to the creation of the Capability Development Group (CDG) in Defence to give focus to and improve capability definition and assessment. Also as a result of the Kinnaird Review, the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) was given greater independence within the department to manage acquisition projects. Later reviews, such as the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review, chaired by Mr David Mortimer AO (the ‘Mortimer Review’) and completed in 2008, extended the thinking of Kinnaird and sought to strengthen the framework established after 2003. This framework—the two-pass system—remains in place and forms the backbone of capability development and materiel acquisition within Defence.

Parliamentary and ANAO coverage

6. Capability development is central to Defence’s ongoing capacity to achieve the outcomes required of it by government—that is, to protect and advance Australia’s strategic interests by providing military forces and supporting those forces in the defence of Australia and its strategic interests.6 Accordingly, it is unsurprising that there has been considerable attention to these issues by parliamentary committees.7 The ANAO’s program of work in the Defence portfolio over the past decade has also provided substantial coverage in this area. A particular focus has been Defence’s processes for the identification, acquisition and introduction into service of the often high-value materiel required to generate capability. In this context, Audit Report No.48, 2008–09, Planning and Approval of Defence Major Capital Equipment Projects, tabled in June 2009, examined Defence’s execution of the two-pass system in the years following the then Government’s acceptance of the majority of the Kinnaird Review’s recommendations. The ANAO’s coverage, including more recent work, has included:

- ANAO’s annual review of the DMO Major Projects Report, which, for 2011–12, reviewed 29 of the most significant major projects currently being managed by the DMO8;

- Audit Report No.52, 2011–12, Gate Reviews for Defence Capital Acquisition Projects, tabled in June 2012, which examined DMO’s Gate Review process conducted at key points in a project’s life, including before submission to government for first and second-pass approval9; and

- various performance audits of individual capability development projects and broader topics, such as Audit Report No.57, 2010–11, Acceptance into Service of Naval Capability, which considered the experience of 20 major projects in delivering capability into service with the Royal Australian Navy (Navy) and the impediments to this.10

7. This audit has been a further contribution to fulfilling the undertaking to the JCPAA in 2006 that the ANAO examine post-Kinnaird activities in Defence and DMO to examine reform progress. There was also an intention in the government response to Mortimer that the ANAO be invited to audit the progress of reform. With the two-pass system having been in place for more than a decade, and substantial time having elapsed since the Kinnaird and Mortimer Reviews reported, this is a broadly-based audit of Defence’s progress in achieving capability development reform.

Common themes in Defence reviews

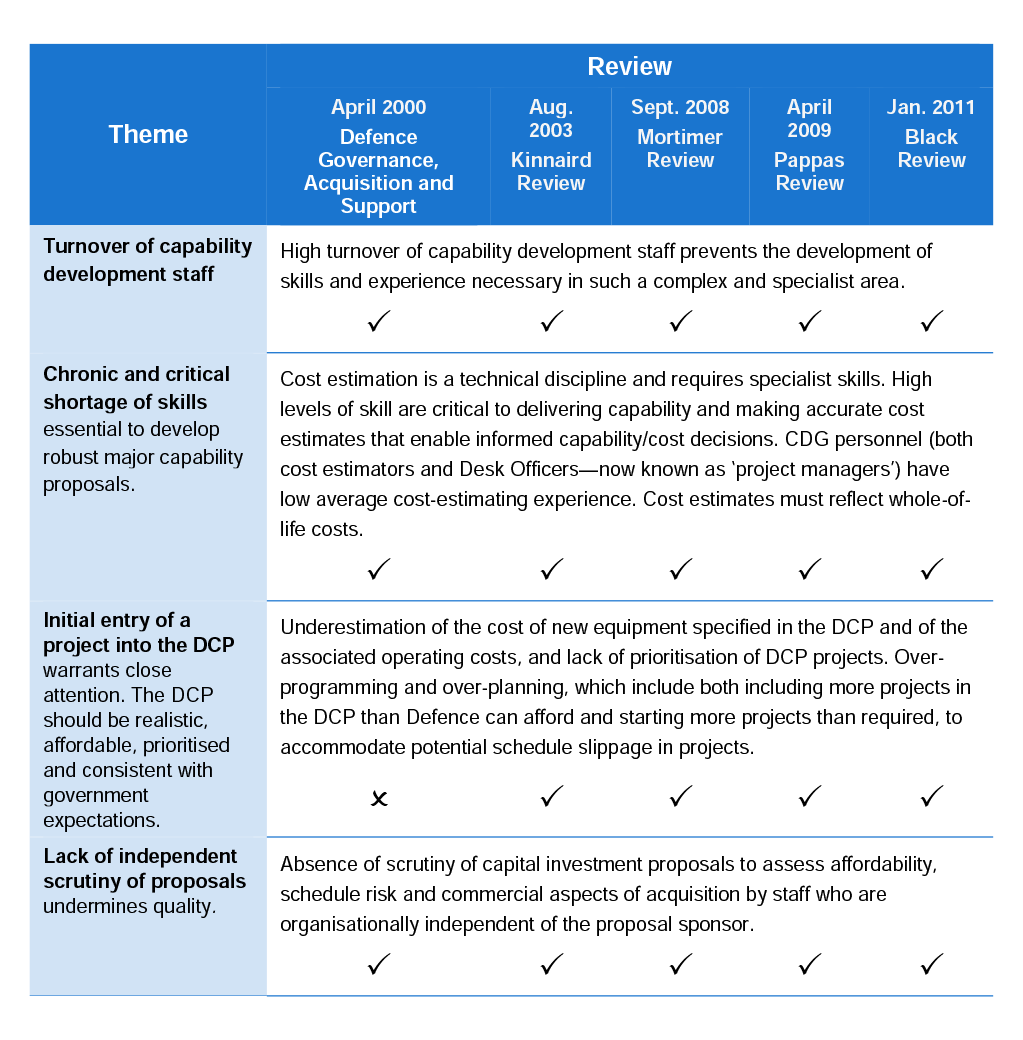

8. Many of the major reviews conducted in Defence over the last decade, including both the Kinnaird and Mortimer Reviews, recommended reforms to the two-pass system or related capability development issues. Accordingly, to inform this audit, the ANAO undertook the preliminary step of analysing the findings of major reviews since 2000. This analysis identified five reviews since the introduction of the two-pass system which were most relevant to capability development reform, and showed that these reviews included common, and often consistent, themes.11 These reviews and themes are in Table S.1.12

Table S.1: Recurring themes in reviews of capability development in Defence

Ticks indicate whether an issue was raised in a review. This table also appears in Chapter 2 (Table 2.1) including additional notes and references to the chapters of this report which consider each of these themes.

Source: ANAO analysis

9. Most of the reviews acknowledged that Defence can demonstrate incremental improvements in some areas of capability development but finds it harder to demonstrate lasting change.13 Defence, similarly, has acknowledged that capability development reform remains an ongoing challenge. In May 2011, the then Secretary of the department observed that:

We have struggled to match our capability aspirations with our capacity to deliver. There are numerous reasons for this, but broadly they fall into three categories. First, we need to identify problems in the development and acquisition of major capabilities earlier ... Second, Defence has expressed difficulty in attracting and retaining an appropriate number of skilled staff to progress our projects ... Third, major Defence projects are technically complex, and some have taken more time than was originally anticipated in order to mitigate technical risks ahead of government consideration.14

10. High-level concern over capability development has continued to the present. In mid-August 2013 the outgoing Minister for Defence formally advised the then Prime Minister, through correspondence, of two significant capability projects which he considered to be case studies ‘for any additional reforms necessary to address systematic deficiencies in procurement and capability projects.’

Audit objectives and scope

11. The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Defence’s implementation of reforms to capability development since the introduction of the two-pass process for government approval of capability projects15 and government’s acceptance of the reforms recommended by the Mortimer Review.16 The scope of this audit included the requirements phase and, to a limited extent, the acquisition phase of major capability development projects, focusing upon changes flowing from the major reforms.17

12. The audit assessed Defence’s progress in four critical areas that encompass the recurring reform themes in Table S.1, and associated review recommendations, namely:

- reforming capability development—organisation and process;

- improving advice to government when seeking approval;

- improving accountability and advice during project implementation; and

- reporting on progress with reform.

13. The audit has not attempted to evaluate the anticipated or actual outcomes, including project outcomes, resulting from implementation of those recommendations made by the various reviews and agreed by successive Australian Governments.

14. Defence was provided with an opportunity to review and comment on a draft audit report in June 2013 and the proposed audit report in August 2013. Defence also provided comments on ANAO issues papers circulated in November 2012. These consultative processes gave Defence ongoing opportunities to provide the ANAO with up-to-date evidence of improvement made by recent initiatives such as its Capability Development Improvement Program, which commenced during the audit.

Overall conclusion

15. Over more than a decade, successive governments have invested substantial effort in reviewing capability development in Defence, with a view to improving the organisation’s effectiveness and efficiency in realising capability for the ADF. For its part, Defence has also put substantial effort into supporting these reviews and organising to give effect to the reform proposals accepted by government. While individual reviews have been initiated by particular circumstances, there has been a common underlying desire to see Defence projects soundly specified, and delivered within scope, on time and within the approved budget, despite their inherent complexity. As the 2011 Black Review observed, capability development is a process which ‘has a profound effect on Defence as a whole, and is where much policy and organisational risk concentrates.’18 Further, the need to manage Defence capability development effectively and efficiently is accentuated in a period of fiscal constraint.

16. Given that such projects are generally technically advanced, frequently incorporate new technology and are interdependent with other projects, it should not be surprising if contingencies sometimes arise that place at risk the achievement of the original expectations. It is generally during the acquisition phase of a capability development project that these issues manifest, including the effect of any shortcomings in Defence’s execution of the requirements phase.

17. The ANAO’s work with the DMO on the annual Major Projects Report focuses on capability projects that have received second-pass approval by government and moved into the acquisition phase managed by DMO. A consistent theme in the ANAO’s findings from this work is that maintaining Major Projects on schedule is the most significant challenge for DMO and its industry contractors. Accumulated schedule delay can result in additional cost and the risk of a gap in ADF capability.

18. The ANAO’s analysis in the Major Project Reports over the last five years, along with the findings of a range of ANAO performance audits of individual major projects and related topics, indicate that the underlying causes of schedule delay in the acquisition phase can very often relate to weaknesses or deficiencies in the requirements phase of the capability development lifecycle, such as where:

- the capability solution approved by government has not been adequately investigated in terms of its technical maturity (including the threshold issue of whether an option is truly off-the-shelf or developmental in some respect)19;

- the capability requirements are inadequately specified, and the procedures to verify and validate compliance with them are not adequately defined and agreed20; or

- significant risks have not been adequately identified and appropriate mitigation treatments developed and implemented.21

19. Accordingly, during this audit, which generally focuses on the requirements phase managed by Defence’s Capability Development Group (CDG), the ANAO sought to identify the progress made by Defence in implementing recommendations for reform agreed by government over the past decade to improve Defence’s capability development performance.

20. The following discussion of the audit findings is structured around the four critical areas of capability development reform identified in paragraph 12: reforming capability development—organisation and process; improving advice to government when seeking approval; improving accountability and advice during project implementation; and reporting on progress with reform. The ANAO’s overall summary conclusion then follows.

Reforming capability development—organisation and process

21. As noted in paragraph five, two-pass approval forms the backbone of the current capability development and materiel acquisition process within Defence. An important element in implementing the two-pass approval process has been the establishment of CDG, whose work largely supports that process. The audit considered both organisational and process elements of CDG’s operation.

Further organisational reform required

22. The establishment of CDG in 2004, following the Kinnaird Review, created an opportunity for the critical work of capability definition and development to be focused in a single area of Defence. One of Kinnaird’s objectives was met in the creation of the position of Chief of Capability Development Group (CCDG) in a timely manner, within some months of the original recommendation.22 However, terms of appointment and the duration of occupancy of the CCDG position have both fallen short of the minimum tenure of five years envisaged by the Kinnaird Review and agreed to by the then Government.23 Accordingly, the stable long-term leadership, through CCDG, that Kinnaird considered essential to achieving better capability development outcomes, has not eventuated.

23. While, inevitably, there will be circumstances which mean that a five‑year term cannot always be maintained, the message from the Kinnaird Review, accepted by government, was that this goal was a key factor in driving improvements in Defence capability development. In relation to CCDG appointments, in July 2013, Defence advised the ANAO that its approach had been ‘to place the officer on a three-year contract, consistent with other three-star officers and provide the option to extend the officer.’ Defence further advised the ANAO, in September 2013, that it was ‘comfortable that CCDG’s tenure is consistent with the Government’s specific announcement in 2003 and its ongoing expectations on this matter’, referring to the media release by the then Minister for Defence announcing the appointment of the first CCDG for an initial three years.24

24. While Defence has interpreted the Minister’s media release as endorsing its decision to appoint the CCDG for three years, this is not consistent with the then Government’s earlier agreement to the minimum five-year tenure as recommended by Kinnaird. That minimum had a clear purpose of providing a ‘single point of accountability ... to provide better integration of the capability definition and assessment process’ in an environment where projects may take many years to progress.25

25. In the same vein, capability development project manager positions, predominantly filled by ADF members, have been subject to continuing high turnover. Both operational demands for many of the same staff, and career management considerations for the individual ADF members, have resulted in the high turnover and, hence, short average duration in these positions within CDG. Although this has been pointed out regularly as a serious issue by reviews over the decade, the ANAO’s survey of CDG staff, discussed below, indicates that the problem remains.26

26. There have been efforts to extend the duration of capability project manager postings in CDG, but this remains work-in-progress. The high turnover detracts from the development of the experience and skills needed in the capability project manager positions. Earnest attempts have been made to provide necessary training to these staff but, as the 2009 Pappas Review pointed out, this can, at best, only partially address the risks flowing from lack of opportunity to develop expertise.27

27. The ANAO’s April 2012 survey of CDG staff, which represents the most recent available information on these matters, identified that there is both a marked variation in the degree of preparatory training undertaken by prospective capability project managers across the various Services28 and in the take-up by individuals of available courses once they are employed in CDG.29 There is also tension between improving staff skills and achieving longer tenure in CDG, on the one hand, and the military posting system and related career interests on the other; with the latter generally prevailing.

28. Sustained senior management attention will be required to develop and effectively implement approaches to improve the CDG workforce’s capacity to successfully carry out its role in the longer term. Defence has advised30 that its Capability Development Improvement Program (CDIP), which commenced shortly before the ANAO survey, is informing the development of reform initiatives ‘to deal with the same issues raised in the survey’. This could involve considering whether alternative strategies might better achieve the goal of an improved definition and assessment function as envisaged by Kinnaird. Alternative approaches that could be assessed include the potential to use a professional group of specialists, who are not serving members of the military (and therefore not subject to regular reassignment), to fill more enduring project manager roles within CDG; and/or the creation, supported by senior management advocacy, of a capability development career stream that would highlight the importance of capability development work and increase its attractions as a career option for both ADF and civilian staff. Any adjustments to the current model would need to ensure that military expertise appropriately informs the capability definition and development process.

Continuing requirement for improved effectiveness of the capability development process

29. Capability development is inherently complex, and the process has been incrementally amended many times over the past decade to improve outcomes. The process is set down in the Defence Capability Development Handbook (DCDH), which Defence sees as an essential foundation for a consistent, rational process of capability development and, consequently, devotes considerable effort to maintaining.31

30. Effective recordkeeping is a necessary element of sound public administration.32 Audit Report No.48, 2008–09, Planning and Approval of Defence Major Capital Equipment Projects found that, notwithstanding the requirements of Defence’s own guidance, CDG could not provide essential capability development documentation for projects examined in the audit.33 There has been a noteworthy improvement in this aspect of CDG’s performance, with this audit identifying that Defence now generally produces and retains for each project the full capability development documentation suite required. While improving its compliance with the extant guidance on the capability development process and improving this aspect of its recordkeeping, Defence has identified duplication in the document suite and opportunities for simplification. CDG is now progressing this matter under its program of continuous improvement, the Capability Development Improvement Program (CDIP), begun in early 2012.34

31. Successive reviews have emphasised the importance of Defence ensuring that committees operate effectively, and that accountability in capability development is made clear.35 In this context, and following the release of the Black Review in January 2011, Defence had been considering a proposal to undertake a business process review of CDG to identify improvement opportunities. Originally, the review was to have been led by the Strategic Reform and Governance Executive (SRGE)36, but it has now been folded into CDG’s internally-led CDIP process. To derive the expected benefits from this business process review, it will be important that its conduct is accorded appropriate priority, and that the perspectives of stakeholders external to CDG are taken into account by the review.

32. Notwithstanding the ongoing efforts to refine the capability development process, it is also clear that further opportunities for improved effectiveness remain, as the committees, procedures and processes involved in capability development have continued to attract criticism, including from those whose work flows through the system. This has been identified in past reviews and in responses to the ANAO’s April 2012 survey of CDG staff conducted as part of this audit. CDG is giving attention to these issues under its CDIP program. Sustained effort, including senior management attention, will be required to embed improvements to the capability development process—such as improved committee arrangements and performance, and streamlined processes and documentation.

Slow progress in strengthening the DCP entry process for projects

33. One of the primary purposes of the two-pass system was to give government better and earlier control over Defence capability development and the major projects that emerge from that process. Because of the way in which two-pass approval has been implemented, a third preliminary approval step has been introduced. This step, which was set out in the revised Cabinet rules proposed to and agreed by the then Government in response to the 2003 Kinnaird Review, required government approval of a capability need (and inclusion of a project in the DCP) to occur as a pre-condition to entering the two-pass process.37

34. Major reviews from the Kinnaird Review forward have consistently emphasised the need for more robust analysis taking place before projects are entered into the DCP, not least because a project attracts authority and momentum when it appears in the DCP, as it has been publicly identified as a Defence capability development priority. 38 Entry into the DCP of a project for which limited analysis has been undertaken is attended by risk, which may be increasingly difficult to avoid as a project progresses. Two Mortimer recommendations intended to address this risk were agreed by government. They were a recommendation to strengthen the DCP entry process, and a recommendation for the preparation, before a project’s entry into the DCP, of a capability submission addressing the capability required, along with initial data relating to cost, schedule and risk.39,40 Reported progress in achieving these reforms has been slow, with Defence advising that its Capability Development and Materiel Reform Committee had closed the two Mortimer recommendations by outcome in August 2013, during the audit.

35. In the longer term, personnel and operating costs generally exceed the initial equipment acquisition costs, and it will remain difficult to attain adequate assurance of DCP affordability as envisaged by Mortimer41 until these can be more reliably estimated and taken into account. Defence’s December 2011 DCP Review found that the then proposed DCP 2013–22 was under-programmed (that is, it was forecast to require no more than the expected funding) over the decade. However, it also stated that more work was required on personnel and operating costs. This work has not yet been done, and this remains a constraint on the assurance that can be provided by Defence on the affordability of the DCP.

Improving advice to government when seeking approval42

36. Successive reviews have emphasised the criticality of Defence providing sound advice to government, as part of the two-pass process, to give ‘confidence that financially and technically robust decisions are being made’.43 The audit considered Defence’s performance in relation to assessing technical risk; preparing whole-of-life cost estimates44; obtaining external verification of cost estimates; including off-the-shelf options in advice to government; and providing CEO DMO independent advice to government.

Improved technical risk assessment approach has been implemented

37. An area where there has been some improvement since the ANAO’s Audit Report No.48, 2008–09, Planning and Approval of Defence Major Capital Equipment Projects was tabled in June 2009 relates to the rigour with which Defence approaches the assessment of technical risk during the two-pass process. The 2009 Pappas Review identified technical risk as the largest source of post-second-pass schedule slippage for post-Kinnaird projects, and also observed that schedule slippage causes cost escalation.

38. Following a subsequent review by the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO), a new process was introduced in 2010 to identify technical risk earlier in the requirements phase of the Capability Development Lifecycle. This process results in the development of the Technical Risk Certification for a DCP project, which is the Chief Defence Scientist’s position on the technical risk included in the project. The methodology for assessing technical risk and developing the Technical Risk Certification for capability development proposals has matured and is being performed according to a documented process. It has been consistently presented in relevant submissions to government examined by the ANAO, to provide advice on the technical risk level associated with capability options proposed for consideration. In this context, the ANAO considers that Defence has satisfactorily addressed the broad intent of the ANAO’s earlier recommendation that Defence refine its methodology for technical risk assessment, and ensure that acquisition submissions do not proceed without a clear statement of technical risk.45

39. While Defence has put in place an improved approach to assess technical risk and provide that assessment to government, Defence’s documented processes are not reflected in the requirements in the Cabinet Manual.46 There would be benefit in updating the Manual to reflect the practice that has now been in place for several years. Although Defence is not the ‘owner’ of the Cabinet Manual and cannot directly change it, as the owner of the two-pass approval process, with responsibility for developing and maintaining that process, Defence has a responsibility to follow up the June 2010 recommendation of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA)47 and work effectively with the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) to pursue amendments to the Manual ‘to accurately reflect Defence’s more specific risk measurement process’.

40. To improve the clarity of advice to government, there would be benefit in Defence providing to decision-makers an explanation of technical risk analysis and its interpretation in relevant documents. There would also be benefit in reviewing a selection of capability development projects at project closure to contribute to Defence’s understanding of the usefulness and accuracy of the technical risk assessments it provides to decision-makers.

Capability whole-of-life cost estimation in advice to government could be made clearer

41. Defence has had a documented policy for whole-of-life (or lifecycle) costing for major capital acquisitions since at least the early 1990s. When a new or upgraded capability is being considered by government in an acquisition proposal, whole-of-life costs represent the total public investment Defence is seeking over the life of the capability. It is, however, inherently difficult to forecast whole-of-life costs accurately, especially over several decades, and decision-makers need to accept the uncertainties in these estimates.48 Nonetheless, recognising the benefits for informed decision-making, successive reviews (including Kinnaird, Mortimer and Pappas) and audits have stressed the importance of Defence making clear to government its estimates of whole-of-life costs for capability proposals.

42. The Kinnaird Review, in particular, concluded that ‘understanding the whole-of-life costs associated with particular platforms is a vital component of managing capability and must be considered throughout all phases of the life cycle of capabilities.’49 Such an understanding underpins Defence’s ability to communicate effectively with government on the costs of maintaining existing capability. The Kinnaird Review also concluded that:

Until Defence financial systems are based on full cost attribution of individual capabilities, Defence and government will not have reasonable visibility of the costs of acquiring and sustaining capabilities. Nor will they be in a sound position to make resourcing decisions on the basis of capability consequences.50

43. Defence is now not pursuing its earlier intention to achieve full cost attribution of individual capabilities through its financial systems, because of the department’s assessment that the cost and complexity of the task outweigh the expected benefits. Nevertheless, this should not inhibit the pursuit of further improvement to support Defence’s capacity to make reasonable estimates of whole-of-life costs for individual capabilities to inform decision-making and the achievement of value for money.

44. Generally, the Defence submissions to government examined in this audit focused upon acquisition costs and the estimated Net Personnel and Operating Costs (NPOC) of using the capability over its expected life.51 NPOC is derived from the difference between the estimated personnel and operating costs of the proposed option (‘future POC’) and the costs for the existing capability (‘current POC’). NPOC therefore represents an estimate of the additional funds that Defence calculates it requires. NPOC and whole-of-life costs give different perspectives, and both are valuable to fully appreciate the financial implications of a proposal. The clarity of all capability development submissions, and the implications of the decisions sought from ministers, could be improved by:

- the use of consistent terminology in all acquisition submissions; and

- more prominence being given to a clear statement of the estimated whole-of-life costs of options in each submission.

Process established for Finance to verify Defence’s cost estimates for capability development projects

45. Having cost estimates externally reviewed has long been recognised as a basic characteristic of preparing credible estimates.52 An expectation of the Kinnaird Review was that, as part of the strengthened two-pass approval process to be developed in accordance with the review’s recommendation, the Department of Finance (Finance) should be involved much earlier and continuously throughout the two-pass approval process and provide external verification of cost estimates.53

46. In its March 2004 response to the Kinnaird Review, the Government agreed that Defence and Finance would develop working arrangements to ensure that Defence would provide Finance with adequate, timely information that the latter would need as part of a thorough approach to verifying Defence’s cost estimates. However, the ANAO’s 2008–09 audit on planning and approval of Defence major capital equipment projects found that no agreed documented approach was in place to facilitate Finance’s early and ongoing engagement to verify cost estimates for capability development proposals.

47. Testimony provided by Defence in October 2009 to the JCPAA’s inquiry into Audit Report No.48, 2008–09 advised that agreement had been reached at a senior level between the two agencies on such an approach and that, in any subsequent ANAO audit, Defence would ‘be able to provide the evidence that agreement had been reached on the new process’.54 Notwithstanding this assurance to the JCPAA, when asked to do so during this audit, neither Defence nor Finance could find any record setting out such an agreement.

48. In October 2011, Finance issued Estimates Memorandum 2011/36, which outlines a process for costing new Defence major capability development projects. Finance subsequently informed the ANAO that, as a result, it generally received submissions from Defence with better notice and greater opportunity to verify costing estimates.

49. In September 2013, following consultation on an update to the Estimates Memorandum, Finance and Defence indicated that the memorandum had been revised and extended, in support of Defence’s development of cost estimates and their verification by Finance.

Routine inclusion of adequate advice on off-the-shelf options in submissions to government yet to be achieved for all projects

50. The merits of acquiring off-the-shelf (OTS) versus Australian-designed or adapted defence equipment have long been discussed, and examination of this issue formed an explicit part of the Kinnaird Review’s terms of reference. Under the strengthened two-pass system proposed by Kinnaird, the review’s expectation was that ‘at least one off-the-shelf option must be included in each proposal to government at first pass. Moreover, any option that proposed the ‘Australianisation’ of a capability would need to fully outline the rationale and associated costs and risks.’55 The intention was to provide government with capacity to weigh the relevant costs, benefits and risks and decide which option or options to pursue.56

51. The Mortimer Review’s terms of reference also required it to consider ‘the potential advantages and disadvantages of greater utilisation of [MOTS] and [COTS] purchases’.57 The Mortimer Review found limited progress with the Kinnaird proposal about OTS options. Mortimer further found: ‘experience shows that setting requirements beyond that of off-the-shelf equipment generates disproportionately large increases to the cost, schedule and risk of projects.’58 Mortimer concluded that Defence should increase its use of OTS equipment to reduce project cost and mitigate the risk of schedule delay and cost increases. The Mortimer Review then made a recommendation (2.3) which it recognised as being stronger than that made by Kinnaird:

Any decisions to move beyond the requirements of an off-the-shelf solution must be based on a rigorous cost-benefit analysis of the additional capability sought against the cost and risk of doing so. This analysis must be clearly communicated to government so that it is informed for decision-making purposes.59

52. With no benchmark from the early 2000s for comparison, it is difficult to assess the progress Defence has made over the decade in implementing the 2003 Kinnaird and stronger 2008 Mortimer recommendations relating to including OTS equipment acquisition options in proposals to government. In February 2010, Defence’s Mortimer Review Implementation Governance Committee (MRIGC) assessed that implementation of Recommendation 2.3 was complete in ‘process’ terms, because the Interim Defence Capability Development Handbook had, since November 2009, described the process to put forward an OTS option. However, the MRIGC papers show that, in ‘outcome’ terms, the status at that point remained ‘still to be tested.’60

53. Subsequently, in a media release on 6 May 2011, Ministers identified ‘benchmarking all acquisition proposals against off-the-shelf options where available’ as one of the Kinnaird/Mortimer reforms which had not yet been fully implemented and whose implementation should be accelerated.61 Later in 2011 Defence engaged a consultant to review a sample of submissions to assess progress against Mortimer’s specific (and stronger) recommendation (2.3). The results of that review, completed on 15 November 2011, are equivocal, and show that Defence has more progress to make to institutionalise the arrangements recommended by Kinnaird and Mortimer and agreed by government.

54. On 28 November 2011, Ministers issued a media release that reported the status of this reform as ‘Implemented—all future projects seeking second‑pass approval that are not off-the-shelf will include a rigorous cost-benefit analysis against an off-the-shelf option.’ Subsequently, Defence recorded Mortimer Recommendation 2.3 as implemented by ‘outcome’ as well as by ‘process’.

55. Nevertheless, if the desired effect of this reform is to be delivered, in terms of better advice to inform capability decisions by government, Defence will need to improve on previous performance and ensure routine compliance with the requirement for all projects seeking approval of a capability option that is not OTS to include in the submission to government a rigorous cost‑benefit analysis against an OTS option.62

Since 2011 a mechanism has been in place for the CEO DMO to provide independent advice to government as envisaged by Kinnaird

56. The Kinnaird Review envisaged independent advice flowing to government from the CEO DMO, who would ‘report to government on detailed issues including tendering and contractual matters related to acquiring and supporting equipment.’63 However, this was in the context of DMO becoming a separate executive agency within the Defence portfolio, a Kinnaird recommendation not agreed by government.

57. The Mortimer Review also proposed that DMO become an executive agency, and recommended that the Chief Executive Officer of DMO should provide independent advice to government on the cost, schedule, risk and commercial aspects of all major capital equipment acquisitions.64

58. The Government did not agree to the proposal to make DMO an executive agency, separate from the Department of Defence.65 However, it agreed that the CEO DMO ‘must be in a position to provide advice to Government on the cost, schedule, risk and commercial aspects of all major capital equipment acquisitions.’66

59. The Minister reaffirmed in 2011 the original view put by Mortimer in 2008, that the view of the CEO DMO is valued as an independent opinion that ministers wish to hear in the context of considering capability development submissions. It took two years and an explicit ministerial request in 2011 for this decision finally to be implemented.

Improving accountability and advice during project implementation

60. A recurring theme in Defence reviews over the decade has been a need to improve accountability for capability development and material acquisition outcomes, including related advice to government during project implementation. The response to this set of issues has included the introduction of a range of new mechanisms, both to add clarity to the parameters of projects and to provide a basis for later reconciliation. The audit considered Joint Project Directives, an initiative originating in the Government’s response to the Mortimer Review; Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs) between DMO and Defence, which function like a ‘contract’ for the purchase of equipment; project closure, which has been a source of difficulty for some years; and capability manager reporting, the origins of which lie in a Kinnaird Review recommendation that has yet to come to fruition.

Introduction of Joint Project Directives slower than expected, and individual JPDs taking longer to conclude than envisaged

61. Defence defines Joint Project Directives (JPDs) as:

A project-specific directive issued by the Secretary, Department of Defence and the Chief of the Defence Force to the nominated [Capability Manager], assigning overall responsibility, authority and accountability for realisation of the capability system to an in-service state.67

62. The objective and potential benefits of introducing JPDs for each of Defence’s major capability development proposals are clear. A written, practical statement setting out the relevant components of the decision the Government has authorised, and the contribution required of each part of the organisation in order to deliver the approved capability, should help each Defence Group remain on track and promote their respective accountabilities, in terms of scope, schedule and cost. It can also provide a sound basis for seeking a change where contingencies arise. Ministers have accepted that introducing JPDs has been a substantial reform. They have regularly and publicly reported on progress with their introduction, and represented JPDs as inhibiting any tendency for Defence to vary authorising decisions.

63. Despite continuing strong expectations from ministers and senior levels of the organisation, Defence has not introduced JPDs in the way that was expected. Contrary to the intention expressed in the 20-point government response to the Mortimer Review:

- JPDs have not been issued immediately after government approval; and

- JPDs cannot have been the basis of all other project documentation, because, generally, corresponding MAAs have been signed first.

64. Defence took over two years to begin to produce the first JPDs notwithstanding that a prime function of a JPD is to clearly express, in a working form, the essence of a government decision and assign responsibilities to Defence Groups. This delay occurred even though JPDs were a Defence initiative in response to the Mortimer Review. The senior committee responsible for implementing JPDs regarded the task as ‘completed’ in early 2010, when Defence had decided on processes but had not, at that time, produced a single JPD.68 Only after ministerial intervention in May 2011 did Defence finalise any JPDs.

65. JPDs are intended to reflect government decisions. If JPDs are to be an effective instrument assigning responsibility and accountability for all the elements of a capability development project, they need to be put in place promptly.69 However, with one exception, Defence had finalised MAAs without a signed JPD, notwithstanding the intention that JPDs should inform MAAs. This practice suggests that, at a working level, Defence did not perceive JPD production as essential, or a prerequisite, to the progress of a capability development project. In this circumstance, where JPDs are regularly finalised after the MAAs they are intended to inform, care will be required to ensure that JPDs properly reflect the relevant government decision, and that MAAs are appropriately aligned with the relevant JPD.

Further work is required to improve accountability

66. In seeking to improve accountability and ensure clarity of purpose across a large organisation, Defence has developed an elaborate system of documents. However, the practical implementation of that system has introduced a risk of misalignment, and substantial effort is required to ensure consistency of these documents with the original project approvals.

67. DMO undertook an Acquisition Baseline Review project between December 2010 and mid-2012 to verify that MAAs were consistent with project authorisation decisions. This was a worthwhile project that revealed a number of occasions where Defence had not advised government in a timely way of difficulties arising in major projects. More recent evidence also shows a lack of timely advice to government about difficulties affecting several individual major projects, including lengthy delays in advising the Minister. These delays extended for several years in some cases. In two particular cases, the Minister stated70 that the projects illustrated the adverse effects of poor project management and the importance of full and ongoing implementation of reforms introduced by the then Government:

These reforms include increased personal and institutional accountability in the delivery of major acquisition projects, earlier identification of projects which have exceeded agreed project performance thresholds, more timely advice to Government, and the need to obtain approval from the initial decision-maker for changes to the Project’s scope, schedule or cost.71

68. The new and recently-announced regime of reporting on variations from original project approvals should help improve accountability, as would a reconciliation of the equipment ultimately delivered against the authorising decision or decisions.

Need for better arrangements to track capability development projects over their lifecycle and close completed projects

69. CDG did not generally follow its own procedure to formally close capability development projects over the period between 2006 and 2011, when it had the responsibility to do so.72,73 Given that business case closure has not generally been carried out, it is not clear how CDG tracks capability development projects, particularly once they have been included in the DCP. During the audit, Defence informed the ANAO that CDG had developed and fielded a ‘Capability Development Management and Reporting Tool’ (CDMRT) to track a project from its DCP entry through to second‑pass approval.

70. Certain reforms undertaken by Defence in recent years show that the organisation recognises that capability development projects require active coordination and project management throughout their life and across the whole of Defence. However, there is no whole-of-Defence system that provides a means of easily tracking and reporting on the status of all capability development projects from conception to completion. As noted in an earlier ANAO performance audit, Defence has long sought to put in place seamless management of ADF capability from requirements definition through to withdrawal from service.74 One of the challenges to overcome is the natural tendency for each Defence Group (such as CDG, DMO, the three Services and Defence Support Group) to focus largely on its own responsibilities. However, these challenges remain to be addressed if a whole-of-Defence view is to be achieved throughout each project’s lifecycle.

71. Acquisition project closure has also been an enduring problem in DMO. Experienced DMO officers have put the view that projects have often remained open for many years after delivery of the relevant capability. In July 2009, the then CEO DMO identified this issue as a concern, and various estimates showed that DMO could expect to close about 50 major projects and recover residual funds held against projects in the order of $400 million to $800 million. Despite the CEO DMO’s concern, and personal instructions for action in 200975, attempts to address this issue failed to gain traction until renewed impetus was provided in 2011 by the requirement to transition all open projects to a new MAA that included the Capability Manager as a signatory.76 DMO identified 57 major projects as being ready for closure rather than requiring transition to new MAAs. DMO’s intention had been to close them by December 2011, but the deadline was extended in some cases.

Capability Manager reporting to government recommended by Kinnaird not in place nearly 10 years later

72. The Kinnaird Review first recommended in August 2003 that Capability Managers should have the authority and responsibility to report to government on the development of defence capability at all stages of the capability cycle. This would help to ensure that Defence, and ultimately, government, could be confident that they both receive an accurate and comprehensive report on all aspects of capability development at each stage in that cycle. Recommendation 4 of the Kinnaird Review also stated that, to undertake this role, Capability Managers should have access to all information necessary to enable them to fully inform government on all aspects of capability.

73. Five years later (August 2008), Defence agreed with the JCPAA finding that progress on this recommendation remained deficient and should be attended to as a matter of priority. That was about the time Mortimer reported and added further weight to the proposal. Several years later still, Defence is still ‘at the initial step’ of Capability Manager reporting. Action so far has taken nearly ten years since Kinnaird, but has not resulted in the envisaged reporting taking place.

Reporting on progress with reform

74. There is a clear need for Defence, both internally and when reporting externally on the reform process, to focus on goals and substantive outcomes rather than on process. In this context, the internal report on the Strategic Reform Program Mortimer Stream, provided to Defence senior management in May 2012, stated:

The key risk to the success of the reforms remains the capacity and commitment of Defence personnel to implement the reforms. There is a perception by some senior Defence officials that the Mortimer reforms have been largely implemented, but the current [statistics are] that nine (9) recommendations by process and 26 recommendations by outcome remain open.77

75. The issue arising from this assessment is that, while there is value (as pointed out by both the JCPAA and Mortimer) in distinguishing between putting a process in place and achieving the intended outcome, a focus on process may assume excessive importance, displace attention from the intended goal, and create an exaggerated sense of progress among senior management. Specific examples identified by this audit include the introduction of Joint Project Directives (Chapter 11) and the inclusion of OTS equipment options in proposals put to government (Chapter 9). In a similar vein, ANAO Audit Report No.25, 2012–13, Defence’s Implementation of Audit Recommendations, observed that internal processes such as monitoring and reporting are a necessary but not sufficient condition for achieving timely and adequate implementation of recommendations.78

76. While Defence’s system for implementing audit recommendations exhibits many positive elements, such as having a clear process for assigning responsibility, and systematic monitoring and reporting on progress by Defence internal audit, there is no similar centralised long-term mechanism for managing the implementation of the recommendations of the various high-profile reviews of Defence. Further, Defence’s current approach has been to report to ministers and senior managers on the implementation of reform recommendations against ‘process’—whether action is underway—as well as outcome—whether the reform objective is being achieved. This approach to reporting can create an impression of momentum and achievement that may not always be warranted if the establishment of process is emphasised more than the delivery of outcomes.

77. The ANAO considers that there would be benefit in Defence implementing systems to centrally monitor progress over time and report on the implementation of review recommendations/reforms, consistent with Defence’s approach to the monitoring and reporting of the implementation of audit recommendations, including those related to the reform of capability development.

Overall summary conclusion

78. As highlighted above, Defence capability development and acquisition have been the subject of over a decade of reviews, with the Kinnaird and Mortimer Reviews providing the backbone for reform. These two reviews alone generated several dozen major recommendations. As noted in paragraph 12, the audit assessed Defence’s progress in four critical areas that encompass the recurring reform themes in Table S.1: the reform of capability development—organisation and process; improving advice to government when seeking approval; improving accountability and advice during project implementation; and, as an essential concomitant, reporting on progress with reform.

79. The outcomes sought by these reforms are that government is provided with the range and quality of information required to allow informed cost/capability trade-off decisions to be made when selecting capability development options, and that Defence is effectively positioned by this information to deliver the selected capability for the expected cost, in accordance with the estimated schedule and to the capability standard approved by government. While acknowledging the challenges, the process of developing appropriate advice and recommendations for government must involve Defence achieving an adequate understanding of the risks, to inform adequate costing and the development of robust schedule estimates for the delivery of the desired capability.

80. Overall, the audit shows that, notwithstanding government expectations, the work required to progress the reform of capability development in Defence has often taken much longer than might be expected, and has delivered mixed results. As a number of reviews have highlighted, the internal mechanisms adopted by Defence, including many of its committees, have a propensity to focus on processes rather than substantive results. In particular, there is a risk that once a process has been put in place, the issue is considered to have been addressed, with insufficient attention given to following up on whether the desired outcome is actually and satisfactorily being achieved.

81. While examining progress with reform, the audit has also identified instances of Defence not reporting to government on significant difficulties affecting individual major projects until long after those difficulties have been apparent within Defence. This is obviously an issue that requires attention by Defence management.

82. In addition to the inherent challenge of reform faced by the Defence Organisation, in the past decade Defence has had to progress this significant body of work, relating to capability development reform, in the challenging context of a high operational tempo, a tightening fiscal environment, and a high rate of turnover at the highest levels of decision-making. In the past 14 years, for example, before the change of government in September 2013, there had been seven Ministers for Defence and six Defence secretaries, with an average tenure of 2 years and 2.2 years respectively.79,80

83. In the circumstances, sustained senior management attention is particularly important to maintain the direction and momentum of reform by ensuring that, through the development and implementation of effective accountability arrangements, the required priority is accorded by all levels in Defence to following through on the effective and timely implementation of improved processes and approaches. Senior management involvement is also a necessary precondition for the development and implementation of effective approaches to improve the CDG workforce’s capacity to carry out its role, including through the review of current arrangements and the consideration of possible alternative approaches to ensuring the availability of critical skills and experience.

84. As noted in paragraph 15, successive governments have invested substantial effort into the various reviews of the past decade, as has Defence in the resulting reform agenda. While there have been improvements, such as the appointment of CCDG and the introduction of DSTO technical risk assessments, substantial work remains to be done to move many important reforms from the stage of directing that a new process be undertaken to achieving the substantive outcomes sought from the relevant reform recommendations.

85. To this end, the ANAO considers that Defence should give priority to:

- improving the quality and timeliness of advice to government, through management reinforcement of expectations at all levels in Defence;

- embedding the reforms aimed at improving accountability for capability development outcomes, in particular relevant reforms to the Defence committee system and the other accountability reforms flowing from the Black Review;

- developing, or otherwise securing access to, the full set of skills and experience required to support the effective development of capability proposals;

- ensuring systematic approaches are in place to enable Defence to achieve cost attribution of individual capabilities, so as to provide government with a better understanding of whole-of-life cost estimates for proposals for new or upgraded capabilities, and to enable government and decision-makers to make informed cost/capability trade-offs in the context of managing budget constraints81; and

- implementing robust systems to centrally monitor and report on the implementation of review recommendations/reforms, consistent with Defence’s approach to the monitoring and reporting of the implementation of audit recommendations, while also recognising the long timeframes sometimes required for effective reform. The development of appropriate systems would also enhance accountability by providing a sound basis on which to report to ministers and the Parliament.

86. In developing recommendations during this audit, the ANAO has taken into account the findings and recommendations of the range of reviews that have considered capability development in Defence over the last decade or so. Accordingly, the intention of the seven recommendations the ANAO has included in this report is to assist Defence in progressing those matters that should be given priority in pursuit of the reform outcomes.

87. In presenting these views, the ANAO is conscious that, for the reforms to succeed and be embedded, there are both process and people issues for Defence to manage. It is challenging but important work that will contribute to better Defence capability development outcomes for the nation.

Agency responses

88. Defence’s covering letter in response to the proposed audit report is reproduced at Appendix 1. Defence’s response to the proposed audit report is set out below:

Defence acknowledges the considerable efforts expended by ANAO in conducting this audit since its commencement in August 2011, and notes that it represents the most extensive external review to date of capability and procurement reforms.

Defence has made significant and demonstrable improvements in project outcomes achieved since Performance Audit Report No.48 2008–09 Planning and Approval of Defence Major Capital Equipment Projects. This has been achieved through adopting recommendations of successive external reviews and internally developed reform initiatives.

Defence has agreed to six Audit recommendations, agreeing to the seventh recommendation to the extent that it can be implemented in accord with the requirements of securely managing sensitive information.

Defence also recognised the need for many of these reforms and the following initiatives are already underway:

- Strengthening the rigour of project entry into the Defence Capability Plan.

- Strengthening the links between capability development and strategic guidance.

- Introducing revised capability development committee governance procedures at key points of the capability life cycle.

- Provision of earlier and more detailed analysis of project technical risk.

- Improvements to Capability Manager reporting on key capabilities.

- Considering the formation of a dedicated career stream for capability development/acquisition.

- Optimising the utilisation of the Capability and Technology Management College.

- Identifying the pre-requisite skills and expertise required for Capability Development Group (CDG) project managers.

With respect to the ratio of APS and ADF positions within CDG, Defence will review the apportionment of ADF to APS (currently 1.1: 1), although continued downsizing of Defence APS could make this difficult.

89. Extracts from the proposed audit report were provided to the Department of Finance (Chapters 7 and 8) and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (Chapter 6) for any comments they wished to make. The Department of Finance’s formal response is included at Appendix 1. The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet chose not to provide any comments.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 (paragraph 3.88) |

To improve the skills and experience available during capability development, the ANAO recommends that Defence reconsider its staffing model for CDG project manager positions. This could include: (i) considering whether the required military subject matter expertise can be adequately provided to capability development projects other than through having Service personnel in these positions; and (ii) considering the formation of a dedicated ADF career stream for capability development. Defence’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.2 (paragraph 5.65) |

To improve the rigour of its assessment of capability development proposals before it recommends to the Government that they be included in the Defence Capability Plan, the ANAO recommends that Defence: (i) review its current processes against the recommendations made by the Kinnaird Review, and the strengthened DCP entry process subsequently recommended by the Mortimer Review and agreed by the Government in 2003 and 2009 respectively; (ii) undertake sufficient preliminary work on each proposal to inform a rigorous assessment (akin to a Gate Review) of the viability of the capability proposal and the likely reliability of the estimates of cost, schedule and risk; and (iii) ensure that, subsequent to DCP entry, the scope of projects and estimations of cost, risk, and schedule continue to be reviewed and assessed as the project is further defined and developed for project initiation; and Government approval sought for any changes to the scope of the project, should it be required. Defence’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.3 (paragraph 6.39) |

To contribute to its understanding of the accuracy of its technical risk assessment process, the ANAO recommends that Defence conduct a review of the technical risk assessment advice it has provided to government for selected capability development projects in the light of subsequent experience in progressing those projects. Defence’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.4 (paragraph 13.46) |

To improve the transparency of its management of acquisition projects, the ANAO recommends that DMO supplement the acquisition project information on its website with acquisition project schedule data for all key milestones from contract signature to Materiel Acquisition Agreement closure, together with any approved variations and summary reasons for those variations. Defence’s response: Partially Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.5 (paragraph 13.47) |

To improve accountability for the management of its major projects, the ANAO recommends that Defence, through its Capability Managers, report each year all major projects closed during the year, including a reconciliation of the capability delivered against the most recent approval decision. Defence’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.6 (paragraph 13.48) |

To progress Defence’s longstanding objective of seamless management of ADF capability throughout its lifecycle, the ANAO recommends that Defence consider the costs and benefits of introducing a system to allow Capability Managers to track and report on the progress of capability development projects from DCP entry through to project closure, with reports available, as required, to all Groups across Defence. Defence’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No.7 (paragraph 15.54) |

To improve reporting and accountability for the achievement of expected outcomes from major reviews, the ANAO recommends that Defence implement systems to centrally monitor progress over time on the implementation of recommendations/reforms stemming from these reviews. Defence’s response: Agreed |

Footnotes

[1] The Defence portfolio comprises component organisations that together are responsible for the defence of Australia and its national interests. In practice, these are broadly regarded as one organisation known as ‘Defence’ (or the ‘Australian Defence Organisation’). The three most significant bodies are:

- the Department of Defence, headed by the Secretary;

- the Australian Defence Force (ADF), comprising the three Services, Navy, Army and Air Force, commanded by the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF); and

- the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO), a prescribed agency within the Department of Defence, headed by the Chief Executive Officer, DMO (CEO DMO).

(Australian Government, Portfolio Budget Statements 2013–14, Defence Portfolio, p. 2.)

[2] Defence uses the term ‘capability development’ to mean the definition of requirements for future capability, principally during the requirements phase of its Capability Systems Life Cycle (CSLC) for major capital equipment. The CSLC comprises: the needs phase; the requirements phase; the acquisition phase; the in-service phase; and the disposal phase. Generally, Strategy Group has the lead responsibility for the needs phase; Capability Development Group for the requirements phase;DMO for the acquisition phase; Capability Managers for the in-service phase; and DMO for the disposal phase.

[3] In addition to the acquisition and support of new or upgraded platforms or systems under Major Capital Equipment Projects for which DMO is primarily responsible, delivering new or upgraded capability to the ADF requires a number of other fundamental inputs to capability (FIC), namely: personnel (Capability Manager responsibility); organisation (Capability Manager responsibility); collective training (shared responsibility between the Capability Manager and the Chief of Joint Operations Command); facilities and training areas (Defence Support and Reform Group responsible for facilities and DMO for equipment and systems); and command and management. (Capability Managers are responsible for regulations and service-specific command and management, while DMO is responsible for the system acquisition and logistics management aspects of the command and management FIC).

[4] See http://www.defence.gov.au/whitepaper2013/, accessed 26 July 2013.

[5] Minister for Defence Materiel, the Hon. Jason Clare MP, Defence Skills Plan to Meet the Challenges Ahead, Media Release, 5 December 2011.

[6] Department of Defence, Annual Report 2011–12, p. 23.

[7] In particular, the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) and the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee have each undertaken significant inquiries in this field. See JCPAA Report 411, Inquiry into financial reporting and equipment acquisition at the Department of Defence and the Defence Materiel Organisation (August 2008) and the preliminary (December 2011) and final (August 2012) reports of the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee’s inquiry, Procurement procedures for Defence capital projects.

[8] The objective of the Major Projects Report is to provide:

- comprehensive information on the status of selected Major Projects, as reflected in the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by the DMO, and the Statement by the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the DMO (in Part 3 of the report);

- the Auditor-General’s formal conclusion on the ANAO’s review of the preparation of the PDSSs by the DMO in accordance with guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA (also in Part 3 of the report);

- ANAO analysis of the three key elements of the PDSSs—cost, schedule and capability, in particular, longitudinal analysis across these elements of projects over time (in Part 1 of the report); and

- further insights and context by the DMO on issues highlighted during the year (contained in Part 2 of the report—although not included within the scope of the review by the ANAO).

[9] Gate Reviews are an internal DMO assurance process involving a periodic, critical assessment of a project by a DMO-appointed Gate Review Assurance Board, comprising senior DMO management and up to two external members.

[10] In Audit Report No.57, 2010–11, the ANAO made eight recommendations designed to improve Defence’s management of the acquisition and transition into service of Navy capability, including reducing delays in achieving operational release of such capability.

[11] During the audit, it became apparent that the reforms recommended by fresh reviews often emphasise, refine or give more impetus to existing initiatives recommended by earlier reviews. Implementation of a reform may remain incomplete when a further recommendation is made.

[12] The result of the ANAO’s examination of the findings of these reviews is in Chapter 2. The reviews referred to are: (i) Department of Defence, Report on Defence Governance, Acquisition and Support (prepared by KPMG), April 2000; (ii) Defence Procurement Review (Malcolm Kinnaird AO, chairman), August 2003—‘the Kinnaird Review’; (iii) Department of Defence, Going to the Next Level: the Report of the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review (David Mortimer AO, chairman), September 2008—‘the Mortimer Review’; (iv) Department of Defence, 2008 Audit of the Defence Budget (George Pappas, consultant), April 2009—‘the Pappas Review’; and (v) Department of Defence, Review of the Defence Accountability Framework (Associate Professor Rufus Black), January 2011—‘the Black Review.’

[13] See, for example, the discussion of the Black Review at paragraph 2.40 of this audit.

[14] Hansard, Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee, Estimates, 30 May 2011, pp. 12–13.

[15] This occurred in 2000.

[16] In 2008. While not intended as a comprehensive audit of Defence’s implementation of the Mortimer Review, this audit does address Defence’s progress in implementing the major recommendations of that Review agreed by government and which relate to capability development, as well as additional undertakings made in the 20-point plan announced in the government response.

[17] During the audit, its scope was formally broadened, primarily to make it clear that the focus was on the implementation of the reforms associated with the two-pass process for capability development, rather than having a narrower, compliance focus on the documentation produced during the two-pass process. Defence was advised of the change in audit scope in November 2012.

[18]Review of the Defence Accountability Framework (the ‘Black Review’), January 2011, p. 92.

[19] See, for example, Audit Report No.26, 2012–13, Remediation of the Lightweight Torpedo Replacement Project and Audit Report No.37, 2009–10, Lightweight Torpedo Replacement Project; Appendix 4 to Audit Report No.52, 2011–12, Gate Reviews for Defence Capital Acquisition Projects (Case Study 2—LAND 112 Phase 4 – ASLAV enhancement; and Case Study 3—AIR 9000 Phase 2, 4, 6 – MRH-90 helicopter).

[20] See, for example, Audit Report No.57, 2010–11, Acceptance into Service of Navy Capability, p. 21, which found that ‘significant deficiencies which adversely affect the projects subject to this audit included: ... the process of gaining agreement on requirements and on the procedures for verifying and validating that equipment fully meets contractual requirements was not adopted as standard practice by DMO and Navy.’

[21] See, for example, Audit Report No.41, 2009–10, The Super Seasprite, Audit Report No.26, 2012–13, Remediation of the Lightweight Torpedo Replacement Project, and Audit Report No.37, 2009–10, Lightweight Torpedo Replacement Project.

[22] Recommendation 2 of the Kinnaird Review (completed in August 2003) was that: a three-star officer, military or civilian, should be responsible and accountable for managing capability definition and assessment; and this appointment should be on a full-time basis, with a defined tenure (minimum five years) to ensure a coherent, cohesive, holistic and disciplined approach. The Government agreed to this recommendation in September 2003. Defence created the position of CCDG in December 2003.

[23] The mean completed tenure of the first three occupants was about two years and seven months. One occupant resigned after 13 months.

[24] In announcing CDG’s formation, Senator Hill, as Minister for Defence, stated on 22 December 2003 that: ‘The new group will be headed by the current Land Commander Australia, Major General David Hurley, who will be promoted to Lieutenant General. His appointment is for an initial three years.’

[25] Kinnaird Review, p. iv.

[26] As part of audit, the ANAO conducted an anonymous survey of CDG staff. The survey was directed at Capability Systems Division (CSD), a major component of CDG, where the relevant staff are located organisationally. All CSD staff were included. The response rate was 80 per cent. Responses indicated that average durations were short both in terms of an individual’s time in each posting to CDG and in terms of their aggregate experience in CDG. The full survey results are in Appendix 2.

[27] Pappas Review, p. 52. An example of an attempt to provide the necessary training is CDG seeking help from commercial organisations to transfer key skills to CDG staff (see paragraph 3.77).

[28] The majority (71 per cent) of Army capability project managers reported having attended the 12-month capability and technology management program (delivered by Defence’s Capability and Technology Management College) before joining CDG, whereas only a small proportion of Navy (14.3 per cent) and fewer still of Air Force (7.1 per cent) reported having done so.

[29] At the time of the ANAO’s survey of CDG staff, most project managers reported having attended three core courses: Introduction to Capability Development, CDG Induction Training and Cost Estimation. Those courses aside, only the course Operational Concept Document had been attended by more than half (53 per cent) and the remaining 13 CDG courses had been attended by only a minority of CDG project managers. A key reason advanced in survey responses for lack of attendance at courses was workload. See the section commencing at paragraph 3.40 and, in particular, Figure 3.5.

[30] In its detailed response to this audit report.

[31] The DCDH has taken various forms since the inception of the two-pass system in 2000. It has been, over this period, a guide, a handbook and a manual. Its development since 2000 is set out in Table 4.1.

[32] See ANAO Better Practice Guide, Implementation of Programme and Policy Initiatives, 2006, p. 58.

[33] It was unclear whether this was due to the material not having been prepared or an inability to retrieve it.

[34] During the audit, CDG also addressed some shortcomings the ANAO had identified in relation to obtaining, and maintaining records of, the endorsement and clearance by senior committees of the essential documents produced in the capability development process.

[35] The December 2011 DCP Review identified that key committee meetings were often information-sharing activities rather than decision-making forums. In 2011, a P3M3 assessment of CDG made a more detailed assessment of the capability development committees. That assessment found strengths in the governance structure but also catalogued many weaknesses, almost wholly associated with the committees. See the section in Chapter 4 commencing at paragraph 4.25.

[36] That is, by a part of the Defence organisation external to CDG, which would have provided the proposed review process with some measure of independence.

[37] Separate from the inclusion of a project in the DCP, Defence can propose—or government can direct—that a new policy proposal (NPP) be raised. An NPP can also result in a project being considered by government for a first or second-pass approval.

[38] See, for example, the foreword to the Defence 2012 Public DCP, in which (p. i) the Minister for Defence describes the purpose of the DCP as ‘to provide industry with guidance regarding Defence’s capability development priorities’. Further, the Minister explained that the DCP contains ‘those priority projects planned for either first or second pass approval over the four year Forward Estimates period.’

[39] Defence’s Mortimer Review Implementation Governance Committee (MRIGC) identified the desired outcome for Recommendation 2.4 was to ‘ensure that sufficient information (cost, schedule and risk estimates) is provided to the Government to allow it to determine whether a project enters the DCP’.

[40] The performance of a Gate Review, or similar process, at this point could provide assurance that an appropriate degree of scrutiny had taken place before entry of a project into the DCP is proposed to government for approval. This was recommended by the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee in its 2012 report. The Government response to that report did not agree with this recommendation, stating that ‘at that point there is often little for [DMO] to review’. (Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee, Procurement procedures for Defence capital projects, Final Report, August 2012, Recommendation 5, paragraph 10.77, p. 163.)