Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

The Award of Funding under the Safer Streets Programme

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the award of funding under the first round of the Safer Streets programme.

Summary

Introduction

1. Prior to the September 2013 Federal election, the Coalition released its Plan for Safer Streets policy. In announcing the policy in October 20121, the then Leader of the Opposition noted that the Safer Streets programme would:

- provide grants to ‘ensure needed local infrastructure such as better lighting, CCTV [closed circuit television] and mobile CCTV can be rolled out in crime hotspots’;

- address crime and anti-social behaviour by helping local communities to implement cost-effective measures;

- be funded from a pool of $50 million to ‘help deliver effective solutions’, and

- redirect funds confiscated under proceeds of crime legislation.2

2. The Safer Streets programme was also included within the Coalition’s Policy to Tackle Crime that was released in August 2013, during the 2013 Federal election campaign. While various Coalition members made specific commitments in the lead up to the election to fund equipment in their electorates, the overarching Coalition policy, as reflected in the Opposition Leader’s announcement, also noted that ‘solutions will inevitably involve the police, community groups, local government, business and residents working together to present clear, well-thought through local strategies’. Neither the original October 2012 announcement nor the 2013 election policy document foreshadowed that some of the $50 million in programme funding would be quarantined for individual projects announced by candidates.

3. Following the election, in the context of the 2014–15 Budget, the Government decided to provide $50 million from the Confiscated Assets Account3 to implement the commitment to establish the Safer Streets programme. Specifically, the Safer Streets programme was to deliver effective solutions which target local crime hot spots and anti-social behaviour through grants focused on retail, entertainment and commercial precincts. The decision further outlined that the first funding round for the programme was to involve the delivery of specific election commitment projects for the installation of CCTV in over 150 communities across 64 electorates.4

4. A key obligation under the grants administration framework is for all grant programmes, including those that fund election commitments, to have guidelines in place.5 Subsequent to the election, programme guidelines were developed by the Attorney-General’s Department (the department). The guidelines were approved by the Minister for Justice (the Minister) in early May 2014. The guidelines provide for multiple funding rounds, with the first being a closed and non-competitive process aimed at delivering election commitments made by Coalition candidates ‘prior to October 2013’.6 In this regard, the guidelines set out that $19.3 million would be allocated in the first funding round7 for projects relating to 150 separate locations (that is, specific election commitment projects). The guidelines also identified various eligibility requirements, including:

- eligible organisations were those identified before October 2013 to deliver specific commitments;

- organisations must be invited by the department to submit an application;

- grant applicants ‘must provide evidence to demonstrate the need for improved security due to crime and anti-social behaviour affecting local communities’; and

- the project/s must be consistent with the programme’s key objectives and principles, namely to:

- ensure that local infrastructure could be rolled out in crime ‘hot spots’ to prevent, deter and detect crime; and

- enhance community safety, particularly around retail, entertainment and commercial precincts, leading to a reduction in the fear of crime in the Australian community and greater community resilience and well-being.

5. The grants administration framework also requires that ministers not make grant funding decisions without receiving written advice from officials on ‘the merits of the proposed grant or grants relative to the grant guidelines and the key consideration of achieving value with relevant money’.8 Consistent with the grants administration framework and the stated policy intent of funding proposed projects that would deliver ‘clear, well-thought through’ crime solutions, the programme guidelines included the (weighted) selection criteria outlined in Table S1. The department was responsible for obtaining applications and assessing them against the eligibility and selection criteria, and then providing funding recommendations to the Minister.

Table S.1: Selection criteria for the Safer Streets programme

|

Criterion |

Weighting (%) |

Selection criteria |

|

1 |

25 |

Demonstrated need for, and the potential impact of, the proposed project. |

|

2 |

25 |

Consistency with proven good practice in crime prevention, including demonstrating the link between the project’s key interventions and the likely community safety and crime prevention benefits of the project and the enduring value to the community. |

|

3 |

20 |

Financial information including quotations, cost estimates and budgets and the overall value for money of the project. |

|

4 |

10 |

Organisational ability to collect data to measure the impact and success of the project and the range of data to be collected. |

|

5 |

10 |

Organisational capacity of the applicant organisation (including the financial viability of the organisation, demonstrated capacity to successfully manage the project and demonstrated capacity to administer grant funds). |

|

6 |

10 |

Organisational ability to manage risks associated with the proposed activity. |

Source: Safer Streets programme guidelines, April 2014.

6. Under the first funding round, as at 8 May 2015, $19.0 million in programme funding had been approved in respect of 85 applications, involving 146 projects. This included funding of $250 000 for one application that was approved by the Minister in December 2013, prior to the programme guidelines being developed.9 Thereafter, invitations to other organisations to submit an application commenced in mid-May 2014, following the approval of the programme guidelines. Between June 2014 and January 2015, a total of $18.7 million was approved by the Minister in respect to a further 84 applications involving 145 projects. Also between June 2014 and January 2015:

- three organisations declined the invitation to apply for funding. Two new applicants were invited to apply for some of this funding (the $150 000 originally committed to one organisation), with one being approved for funding and an assessment for the other yet to be finalised. A decision on the remaining funding, which was originally allocated to two of the three organisations that declined funding, had yet to be made by the Minister;

- one application was assessed and not recommended for funding by the department. The department advised ANAO that it discussed the application with the Minister’s office and explained that, although it had recommended against funding, upon ‘closer review the department considered that the applicant may have misunderstood the process and as such did not correctly complete the application’. The department provided the organisation with the opportunity to revise and resubmit its application10; and

- funding agreements were yet to be signed in respect of four applications approved for funding.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

7. In July 2014, the Hon. David Feeney MP, the Shadow Minister for Justice, requested an ANAO audit of the Safer Streets programme. In respect to the first funding round that was focused on Coalition election commitments, Mr Feeney raised a number of concerns about the establishment of the programme and selection of projects, eligibility for organisations to apply for funding and political neutrality in the selection process. After undertaking preliminary inquiries of the department in relation to the matters raised, the Auditor-General decided to undertake a performance audit of the Safer Streets programme.

8. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the award of funding under the first round of the Safer Streets programme.

9. The audit examined the key elements of the first funding round. This included the design of the programme and the assessment and decision-making processes in respect to the 85 applications that had been received, assessed and approved for funding.11 The audit scope also included the announcement of funding decisions and the negotiation and signing of grant agreements.

10. The audit criteria reflected relevant policy and legislative requirements for the expenditure of public money and the grants administration framework, including the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (which from 1 July 2014 were replaced by the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines). In this respect, and as previously outlined by ANAO12, the grants administration framework was developed based on a recognition that the statutory obligations applying to the approval of spending proposals derived from election commitments are no different from those attached to the approval of any other spending proposal.13 In this context, in deciding upon the requirements of the grants administration framework, government accepted recommendations that:

- guidelines be developed for all grant programmes, including those established to fund election commitments; and

- Ministers receive and consider agency advice on the merits of proposed grants (as assessed against the relevant programme guidelines) before taking any decisions on the award of individual grants, and this requirement should apply to all grant spending proposals, including those designed to satisfy commitments made in the context of election campaigns.

11. The audit criteria also drew upon ANAO’s administration of grants Better Practice Guide (the June 2010 version of this Guide was available at the time the Safer Streets programme was implemented, and was replaced in December 2013 with an updated Guide).

Overall conclusion

12. The $50 million Safer Streets programme was established to fund the installation of closed circuit television (CCTV) cameras and other security related infrastructure in crime ‘hot spots’ to prevent, deter and detect crime. The first round quarantined $19.3 million of programme funding to deliver on commitments made by the Coalition in relation to the 2013 Federal election. As at 8 May 2015, $19.0 million in programme funding had been approved in respect to 85 applications, which involved 146 projects. Most commonly, the funded projects involved the installation of CCTV cameras and/or street lighting.

13. The design of the first funding round of the Safer Streets programme recognised that the use of public money to fulfil election commitments may only occur in accordance with the financial framework that governs the expenditure of funds from the Consolidated Revenue Fund. In this respect, the effective implementation of commitments made in the context of an election campaign is reliant on both the:

- development of an administrative approach that ensures both decision-makers and potential grant recipients are made aware of the need for projects proposed for funding to satisfy appropriate minimum standards (including the requirement that the use of public resources be efficient, effective, economical and ethical); and

- implementation by the responsible agency of a consistent and comprehensive process of inquiry and assessment in relation to each project being considered for funding, in order to appropriately inform the decision-maker.14

14. In the main, the programme guidelines provided a reasonable basis for the implementation of the first funding round. This included specifying eligibility criteria and other eligibility requirements that were consistent with the programme objectives, and setting out six selection criteria that were appropriate for the first round. However, there were a number of significant shortcomings in the Attorney-General’s Department’s implementation of processes for eligibility checking, application assessment and the subsequent provision of funding recommendations to the Minister for Justice.

15. The administration of the merit assessment process is an aspect that was handled particularly poorly by the department. Under the grants administration framework, selection criteria are applied to assess all eligible, compliant applications in order to determine their merits against the operational objectives of the granting activity. As the first Safer Streets programme funding round operated through a closed, non-competitive process, candidate proposals were not required to be ranked according to which of them had demonstrated the greatest merit. Rather, the task for the Attorney-General’s Department was to be satisfied that only those eligible proposals that met the six criteria to a satisfactory level were recommended for funding. In terms of the published criteria, this necessarily required that:

- there was a demonstrated need for the project (for example, from available crime statistics);

- the proposal would have an impact on crime and that this impact could be measured;

- the costs of the equipment proposed to be installed with grant funding were reasonable; and

- the project could be delivered by the organisation.

16. However, it was common for the department to complete its assessment of applications without fully addressing each criterion, and without having obtained sufficient information from the applicant. Instead of pursuing the information that applicants had not provided or assessing the application as not satisfactorily meeting the relevant criterion, the department made generous assumptions about the quality of many of the proposals that had been submitted for assessment. This included making assumptions that: projects were located in crime ‘hot spots’ or that there was otherwise a need for the project; the project would result in reduced levels of crime without this being evident from the application; or that a grant would provide a value-for-money return to the Commonwealth notwithstanding (for example) that the department was unaware of the number of CCTV cameras that would be installed for the amount of grant funding sought.

17. The department’s approach allowed it to score applicants highly enough to support recommendations to the Minister for Justice that he award funding to all but one of the applications that were assessed.15 In addition, to the limited extent that the department’s assessments highlighted key risks and weaknesses in applications, these were not adequately reflected in the advice provided to the Minister for Justice. Specifically, the advice did not provide adequate commentary about any identified weaknesses in applications, and the limitations on the department’s assessment work. There is an expectation that advice from officials addresses the extent to which proposed grants have satisfactorily met each of the selection criteria, given the strong linkages between those criteria and programme objectives. The grants administration framework then incorporates a process to accommodate any situations where a Minister decides to approve funding for applications that the relevant department has recommended be rejected.

18. Against this background, the department’s assessment of applications and approach to advising the Minister were not sound having regard to the policy design for the Safer Streets programme, the requirements of the grants administration framework and, recognised better practice. There were also shortcomings in the terms of the funding agreements that have been signed by the department in relation to the approved projects. Of particular note is that it has been common for agreements to not adequately set out what the proposed project would deliver and where.16 This situation makes it difficult for the department to adequately oversight the delivery of the funded projects, or to assess whether those projects have been successful in preventing, detecting and deterring crime in crime ‘hot spots’.

19. The administrative shortcomings evident in the department’s approach do not reflect the benefits of the substantial work that has been undertaken by successive governments since 2007 to develop and improve the grants administration framework. Under this framework, a broad range of material was available to inform the design and implementation of grant programmes such as the Safer Streets programme, including: the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (now the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines) and associated guidance issued by the Department of Finance; the ANAO’s grants administration Better Practice Guide and various performance audit reports of individual grant programmes; and Parliamentary Committee reports (particularly those produced by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit). In this context, the ANAO has made five recommendations to the department that relate to the:

- development of procedural and related documentation that will lead to the adoption of sound administrative practices when implementing grant programmes;

- implementation of eligibility checking processes that are well informed and address all relevant requirements;

- adoption of assessment practices that clearly and consistently address the extent to which candidates for funding can be considered to have satisfactorily met the programme selection criteria;

- provision of sound advice to decision-makers as to the merits of candidates for funding under grant programmes; and

- department ensuring that the terms of funding agreements signed with successful applicants clearly identify the specific deliverables for which grant funding was awarded.

Key findings by chapter

Programme Design and Access (Chapter 2)

20. The grants administration framework was developed based on the recognition that a clear set of programme guidelines is essential for efficient, effective and consistent grants administration. In this context, the guidelines established for programmes that fund election commitments provide the vehicle for informing project proponents:

- that funding can only be approved where the project is an efficient and effective use of public money, and of the criteria that will be considered in undertaking this assessment; and

- where funding is approved, of the obligations that proponents will be expected to satisfy.17

21. Guidelines were developed for the Safer Streets programme, and approved by the responsible Minister. In the main, the programme guidelines provided a reasonable basis for the implementation of the first funding round. Nevertheless, there were aspects of the structure of the guidelines that could have been improved. For example, the guidelines were not well structured in that eligibility requirements were not grouped together (an approach that did not assist in ensuring applicants were aware of all mandatory requirements, or in ensuring that all such requirements were consistently applied in the assessment of applications).

22. In addition, although the guidelines provided a reasonable basis for the implementation of the first funding round, the finalised guidelines were less robust than those initially drafted by the department.18 In this respect, following a request by the Minister’s office to simplify the guidelines, the department proposed various amendments. Of note was that a number of key statements were removed from the proposed programme guidelines, including statements that projects:

- must have clear benefits for the broad community and well-defined and achievable objectives;

- would not be eligible for funding if they did not meet the selection criteria; and

- must demonstrate need through high crime rates in the area where they were to be delivered, as evidenced by law enforcement or Australian Bureau of Statistics data.

23. The department did not provide advice to the Minister’s office on the adverse impact the changes to the programme guidelines would have on delivery of the programme, particularly in assessing the merits of applications, or the outcomes that could be expected from the award of funding. In this context, the grants administration framework and the lessons from various ANAO audit reports indicate that the more clarity that can be conveyed in the programme guidelines, which align to the programme objectives, and which are addressed by applications, the more likely it is that funded projects will further the programme’s aims. While there is always a balance to be struck, the guidelines initially drafted by the department were more consistent with the announced policy parameters for the programme and the grants administration framework. In circumstances where suggested variations would have an adverse effect on the department’s responsibilities and programme outcomes, this should be raised with the Minister.

24. Another requirement of the grants administration framework is that agencies should develop internal policies, procedures and operational guidance to support the implementation of the programme. However, the department gave insufficient attention to developing such arrangements. In particular, implementation risks (such as maintaining probity, consistency in assessment, meeting programme objectives and supporting future evaluation of outcomes) should have been mitigated through relevant planning documents, guidance material for staff undertaking grants administration tasks (such as assessing applications) and more active management oversight. In this regard, it is now recognised as sound practice for the departmental documentation that supports the delivery of a grants programme to include:

- application and assessment forms that address all of the requirements set out in the programme guidelines;

- a documented implementation plan or assessment methodology, so as to support the consistent application of programme guidelines (particularly where a range of staff assess applications, as was the case with the Safer Streets programme); and

- an evaluation strategy19, developed during the design phase of the granting activity, that is consistent with the outcomes orientation principle included in the grants administration framework.

25. The absence of sound arrangements to guide and support the implementation of the Safer Streets programme contributed to significant shortcomings in the assessment of the applications that were received.

Identifying Candidate Proposals and Assessing their Eligibility (Chapter 3)

26. The programme guidelines established that the first funding round would be undertaken as a closed non-competitive process, limited to delivering election commitments. In this regard, only organisations and projects identified prior to October 2013 were eligible. A list of organisations and projects that were to be invited to apply for funding was developed by the incoming government and provided to the department. The list was then adjusted, consistent with advice from the Minister’s office, over various iterations, and was not verified by the department. In this respect, several projects were announced but no organisation was invited to apply for Safer Streets programme funding for those projects. In addition, another seven projects were included in the list although no public announcement of an election commitment had been made.

27. The department assessed each application it received as being eligible, notwithstanding the information available to the department not supporting such an assessment for a considerable proportion of the applications received. To appropriately assess eligibility, two key areas in which the department needed to source information were that, firstly, applicants provided evidence to demonstrate the need for the project, and that, secondly, projects were the subject of an announcement before or during the 2013 federal election to deliver specific commitments. However, a significant proportion of applicants did not provide evidence to demonstrate need, and the department was only able to identify 30 announcements (such as media releases, media reports and internet-based material), issued prior to October 2013, which evidenced commitments made to fund projects included on the list of Safer Streets programme funding candidates. The ANAO analysed the eligibility of applications, based on the programme requirements as stated in the guidelines, identifying that 56 applications (66 per cent of applications received) did not meet these requirements.20

28. More broadly, the department’s eligibility checking process was poorly designed and implemented. Of note was that departmental assessments of eligibility were undertaken in the context of insufficient information having been requested in the application form and a checklist that did not prompt consideration of all eligibility requirements specified in the programme guidelines. In this latter respect, in addition to specific sections identifying eligibility and threshold criteria, statements were included in other sections of the programme guidelines that also represented mandatory requirements to be satisfied in order to receive funding.21 This approach, as has previously been observed by the ANAO including in the grants administration Better Practice Guide, does not assist in ensuring applicants are aware of all mandatory requirements, or in ensuring that all such requirements are consistently applied in the assessment of applications.

Assessment of Applications (Chapter 4)

29. A key obligation under the grants administration framework is that Ministers do not make decisions on the awarding of grants without first receiving written advice from officials on the merits of the proposed grant or group of grants. There are companion obligations on officials as to the content of their advice to Ministers.22 Those obligations include that the advice address the merits of the proposed grant or grants relative to the grant guidelines, as well as the key consideration of achieving value with money.

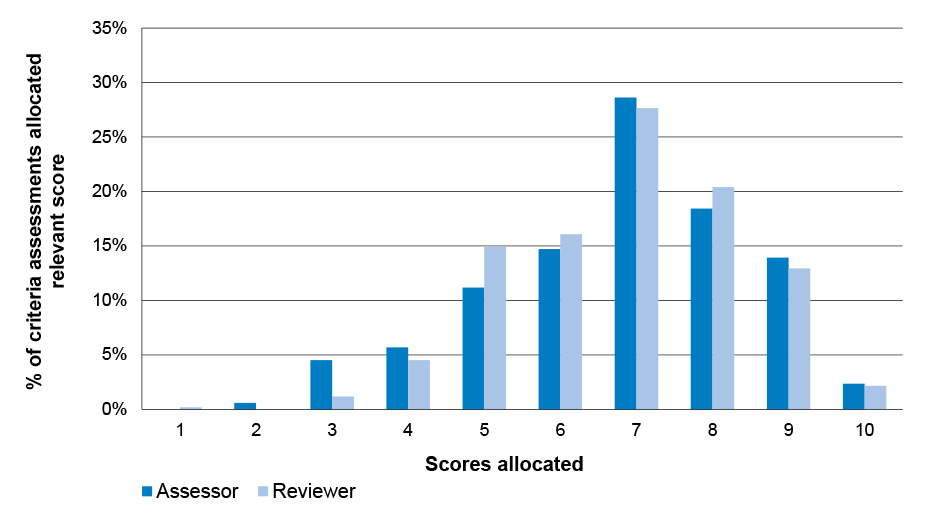

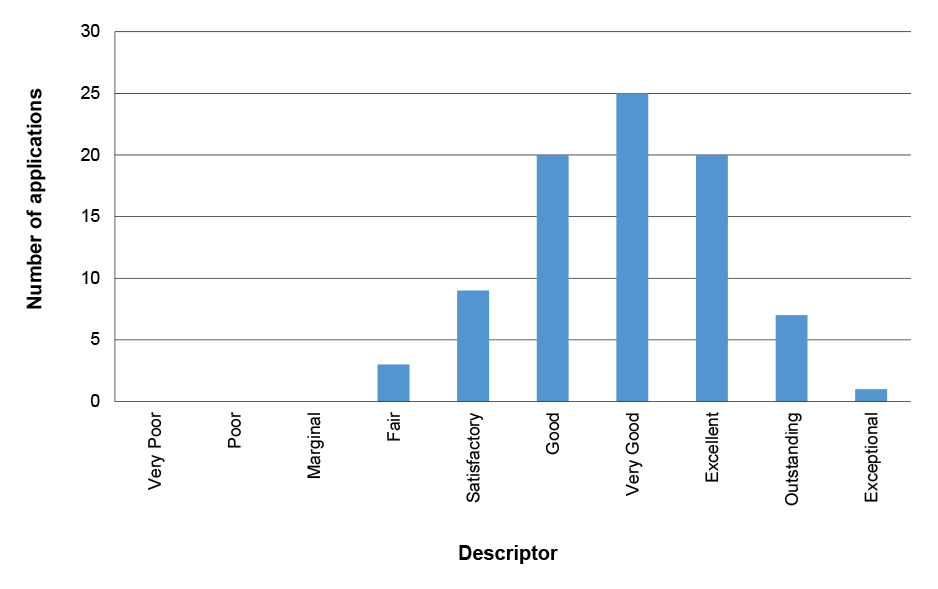

30. The results of the department’s assessment indicated to the Minister that the applications received were predominantly of ‘Good’ or better quality. Specifically, no applications were categorised as ‘Very Poor’, ‘Poor’ or ‘Marginal’, with the significant majority (85.9 per cent) of applications categorised as ‘Good’, ‘Very Good’, ‘Excellent’, ‘Outstanding’ or ‘Exceptional’.23

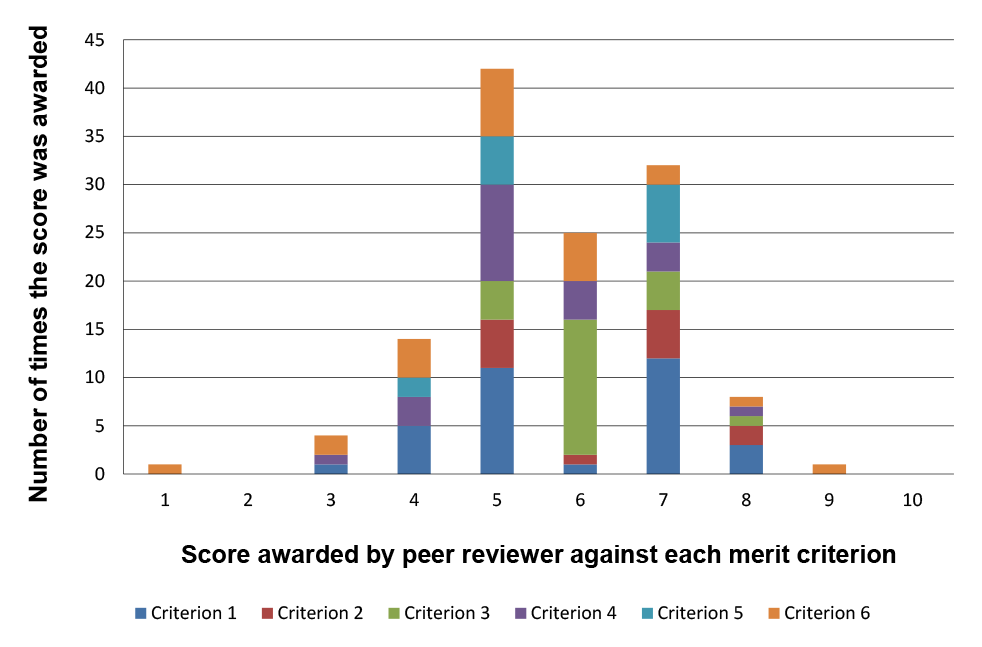

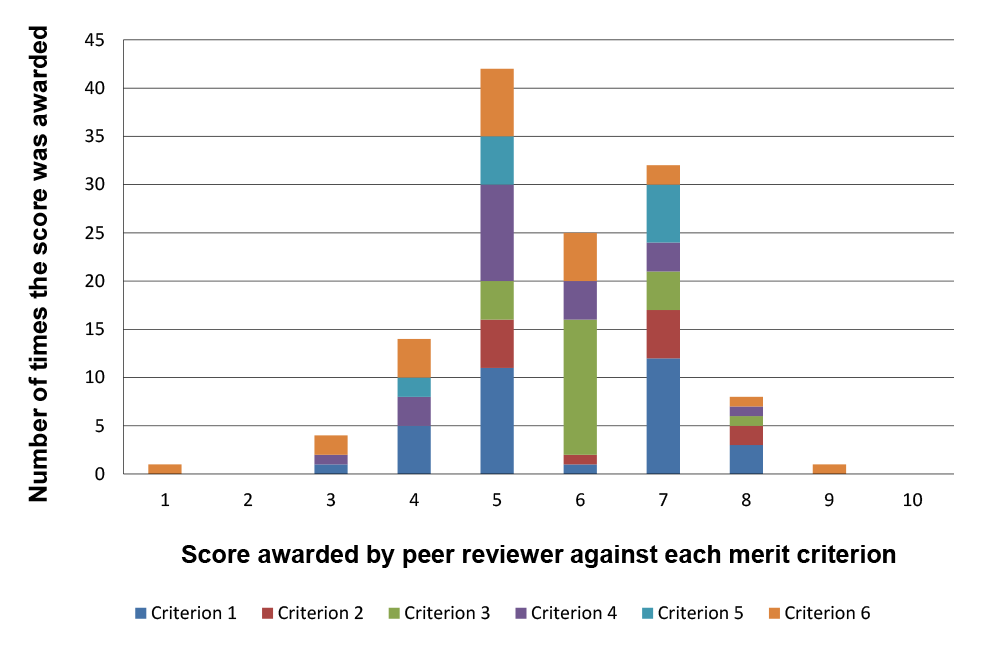

31. However, the department’s assessment approach was poorly designed and implemented such that the assessment ratings advised to the Minister overstated the extent to which applications had demonstrably met the published criteria. In this respect, and as illustrated by Figure S2, it was common for the department to assign criteria scores of five out of 10 or more to applications notwithstanding that the assessment records had outlined that insufficient information had been obtained to properly inform the department’s work. In these circumstances, assessors often recorded that they had made assumptions about the application, rather than pursuing (or further pursuing) the information that applicants had not provided so as to make an objective assessment against the relevant criterion, or assessing the application as not satisfactorily meeting the relevant criterion.

Figure S.1: Scoring of applications where the department’s assessment recorded that insufficient information had been submitted

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

32. Another significant shortcoming involved the recorded assessments not fully addressing the published criteria, including key aspects of various criteria.24 Shortcomings in this respect were particularly noteworthy in relation to the two highest weighted criteria (see Table S1).

33. For example, it was common for the department’s assessments in terms of the first criterion to inadequately address whether the applicant had provided evidence to support the need for the project, or the quality of any supporting evidence that was provided. In particular, while there was no prescribed manner in which need was to be demonstrated, there were 65 applications (76 per cent of applications assessed) that did not include official crime statistics to demonstrate the need for the project.25 This was notwithstanding the programme guidelines stating that applicants ‘must provide evidence to demonstrate the need for improved security due to crime and anti-social behaviour affecting local communities, in particular local retail, entertainment and commercial precincts’. Similarly, in 47 instances (55 per cent of applications assessed), the applicant did not provide evidence of, or demonstrate, how the proposal met the requirement under the second criterion that the project be consistent with good practice in crime prevention.

34. The approach taken to the other four criteria were also lacking in important respects including:

- 28 applications did not include a quotation26 for the crime prevention solution (such as a quoted price for the CCTV cameras to be installed) but each was, nevertheless, scored by the department to be ‘Satisfactory’ or better against the third criterion relating to financial information for the project. In this context, an assessment approach that addresses the quantum of goods/services to be received for the amount of grant funding requested has been applied across many grant programmes, in various entities, to inform an assessment as to whether the award of grant funding would be a cost-effective use of public funds; and

- in relation to the fourth criterion, to measure the impact and success of the project, it was common that the recorded assessment did not outline the data to be collected by the applicant and/or a description of how the applicant intended to measure the impact and success of the project.

Advice to the Minister and Negotiation of Funding Agreements (Chapter 5)

35. ANAO has recently observed27 that, while decisions on policy are a matter for government, departments are expected to provide frank, comprehensive and timely advice to Ministers on policy design and implementation risks as part of the policy development process. Similarly, in the context of the obligation that Minister’s only award grant funding after receiving written advice from officials on the merits of proposed grants relative to the programme guidelines, it is important that Ministers receive candid advice as to how each proposed grant has been assessed to have performed against the eligibility and selection criteria included in the guidelines.

36. Against this background, there is a risk that early announcements by Ministers and/or other Parliamentarians about whether project proposals will receive funding has the potential to influence, or be seen to influence, the assessment work and subsequent advice as to whether funding should be approved. In this context, in relation to the Safer Streets programme:

- prior to any departmental assessment and advice about applications, almost 56 per cent of all applications received by the department under the programme were the subject of a public announcement after the election, but prior to applications being received and assessed, indicating that the project would be funded; and

- the advice provided by the department to the Minister recommended that the Minister approve 84 of the 85 applications that had been received and assessed. The Minister approved the 84 recommended applications. For the one application in respect to which the department recommended that funding not be approved, following a request from the Minister’s office for more details about the reasons for not recommending the project, the department afforded the applicant an opportunity to provide further information to strengthen its application28 with a revised application received in March 2015 (in respect to which the department had not completed its assessment by 8 May 2015).

37. The information the department provided to the Minister to support its recommendations about whether funding should be approved included the overall assessment rating and some brief comments on the application. The Minister was not provided with other relevant assessment information such as how each application had performed against each of the six selection criteria.29 The advice also did not outline the key risks and weaknesses that departmental assessments had identified with many of the applications (including where insufficient information had been provided such that the departmental assessment was based on assessors making assumptions about the project – see paragraph 31 and Figure S2).

38. With some delays, 75 funding agreements have been signed.30 In a number of important respects, the funding agreements will not allow the department to adequately oversight the delivery of funded projects, and assess whether those projects have been successful in preventing, detecting and deterring crime. Shortcomings include not adequately setting out what the proposed project would deliver and where.31

Summary of entity response

39. The proposed audit report was provided to the Attorney-General’s Department and the Minister for Justice. The department provided formal comments on the proposed report and these are summarised below, with the full response included at Appendix 1:

The Attorney-General’s Department designs and administers a wide range of grants programmes aligned with portfolio responsibilities ranging across law and justice, national security, emergency management and the Arts sectors. Grants vary widely in size and scope and a variety of funding approaches are employed according to suitability and the application of the proportionality principles outlined in the Commonwealth Grant Rules and Guidelines, July 2014.

The Department recognises the importance of continuous improvement in its processes to maintain and improve performance and compliance in the delivery of programmes.

A principles-based ‘Grants Management, Guidance and Procedures Manual’ was developed and released by the Department in 2010.

In 2014 the Department worked to improve this by examining, among other things, the grants templates available for use by Departmental staff undertaking grants work. That review led to the launch on 16 July 2014 (which was after the Safer Streets programme had commenced) of an AGD grants administration ‘tool kit’ including a Guide to Grant Administration, help cards and a suite of documents and templates. The documents cover all stages of the grant administration cycle and are based on the requirements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and whole-of-government best practice. These are available to all Departmental staff through a centrally located database. Staff working in grant administration line areas have been requested to use the standard documents and templates to ensure the Department undertakes grants functions in a consistent manner, and in compliance with all legislative and whole-of-government requirements.

The Department has recently developed and delivered a ‘Grant Application and Assessment’ training module that specifically addresses the recommendations of the ANAO report including all footnoted references from the ANAO Better Practice Guide, Implementing Better Practice Grants Administration, December 2013. That training and the Department’s grant intranet site both highlight the contents of the Department of Finance’s Resource Management Guide No. 412, July 2014, which provides both a ‘Better practice checklist for grant guidelines’ and a ‘Checklist for officials briefing ministers on proposed grants’.

The Department has also recently developed and commenced delivery of an additional training module aimed at assisting staff involved in assessing grants to understand balance sheets and financial data, which can be relevant to both assessing applications and evaluating delivery.

The Department will consider the findings of ANAO’s audit of round one of the Safer Streets Programme in future funding rounds delivered under this Programme.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.54 |

To underpin efficient, effective, economical and ethical grants administration across all granting activity it administers, ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department:

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Noted |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 3.55 |

To promote robust eligibility checking processes for all granting activities it administers, including those used to fund election commitments, ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department:

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 4.56 |

To promote the robust assessment of applications to all grant programmes it administers, including those that are used as a funding source for election commitments, ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department:

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 4 Paragraph 5.66 |

To ensure Ministers are provided with sound advice as to the merits of candidates for funding under all grant programmes it administers, including those used to fund election commitments, ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department clearly outline in briefing material:

Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed Continued on next page |

|

Recommendation No. 5 Paragraph 5.70 |

To promote the achievement of granting activity objectives, ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department ensure that the terms of funding agreements signed with successful applicants clearly identify the specific deliverables for which grant funding was awarded. Attorney-General’s Department’s response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the Safer Streets programme and sets out the audit objective, scope and criteria.

Background

1.1 Prior to the September 2013 Federal election, the Coalition announced that, if it was elected, it would implement its Plan for Safer Streets policy. In announcing the policy in October 201232, the then Leader of the Opposition noted that the Safer Streets programme would:

- provide grants to ‘ensure needed local infrastructure such as better lighting, CCTV [closed circuit television] and mobile CCTV can be rolled out in crime hotspots’;

- address crime and anti-social behaviour by helping local communities to implement cost-effective measures;

- be funded from a pool of $50 million to ‘help deliver effective solutions’, and

- redirect funds confiscated under proceeds of crime legislation.

1.2 The Safer Streets programme was also included within the Coalition’s Policy to Tackle Crime that was released in August 2013, during the 2013 Federal election campaign. While various Coalition members made specific commitments in the lead up to the election to fund equipment in their electorates, the overarching Coalition policy, as reflected in the Opposition Leader’s announcement, also noted that ‘solutions will inevitably involve the police, community groups, local government, business and residents working together to present clear, well-thought through local strategies’.

1.3 Following the election, in the context of the 2014-15 Budget, the Government decided to provide $50 million from the Confiscated Assets Account33 to implement the commitment to establish the Safer Streets programme. Specifically, the Safer Streets programme was to deliver effective solutions which target local crime hot spots and anti-social behaviour through a grants programme focused on local retail, entertainment and commercial precincts. The first funding round for the programme was to involve the delivery of specific election commitment projects for the installation of CCTV in over 150 communities across 64 electorates.

Safer Streets programme

1.4 The Safer Streets programme reflected the Coalition Government’s commitment to provide crime prevention funding to communities around Australia. In particular, the policy objectives established by the Government in the period following the election included to:

Deliver effective solutions to local crime hot spots and anti-social behaviour through a grants Programme focused on local retail, entertainment and commercial precincts … The Safer Streets Programme will fund security-related infrastructure grants to support installation of fixed and mobile CCTV systems and lighting to tackle crime and ensure safety in identified hot spots. Funding will also be available for community safety initiatives that address anti-social and unlawful behaviour, supported by chambers of commerce, local councils and police, with a particular emphasis on local retail, entertainment and commercial precincts.

1.5 The Government’s approach to identifying initial funding recipients was also set at this time. It was not intended to be a competitive selection process open to all applicants. Rather:

The Programme will deliver specific election commitments for the installation of closed-circuit television (CCTV) in communities in 64 electorates.

1.6 In this context, the commitments to be funded were to be those made by the Coalition prior to and during the 2013 Federal election campaign, with identified organisations to be invited to submit applications for funding. As outlined in a briefing to the Minister for Justice relating to the implementation of the Safer Streets programme, commitments were made to approximately 150 projects/locations34 in 64 electorates across Australia to receive funding of $19.7 million, with projects to be undertaken between 1 July 2014 and 30 June 2017. The remaining funding of $28.8 million was to be made available for projects that were similar to, or an extension of election commitments, and for projects addressing anti-social behaviour, with the implementation arrangements to be settled at a future time.35

1.7 The Attorney-General’s Department was responsible for the establishment; design; implementation; and monitoring and reporting of the performance of the Safer Streets programme. In respect to its role, the department advised ANAO in March 2015 that:

The Safer Streets Programme was established to deliver a set of commitments made by the Coalition prior to the 2013 election. While the Department was responsible for the administration of the programme, it was not responsible for the identification, value or purpose of commitments made by the Coalition.

Implementation of the first funding round

1.8 Safer Streets programme guidelines were approved by the Minister for Justice on 2 May 2014. They outlined:

- a closed process for invited applicants to apply for grant funding;

- priority funding for improved lighting and CCTV projects as well as the purposes for which project funding would not be provided;

- various eligibility and selection criteria to be used in assessing applications along with the weightings to be applied; and

- the assessment process.

1.9 The department, in consultation with the Minister’s office, was responsible for contacting the identified organisations and inviting them to submit an application for funding under the programme, setting out how they would implement the commitment made by the Government during the 2013 election campaign.36 Invitations to applicants commenced in mid-May 2014 and applications were to be submitted via the online forms provided on the department’s website by 2:00 PM (Australian Eastern Standard Time (AEST)) on Thursday 12 June 2014. Accordingly, the implementation approach for the programme included a four week application period, followed by a three week period to assess applications, with funding recommendations provided to the Minister at the end of June 2014, and projects commencing in July 2014. In ANAO’s experience, this timetable was likely to prove challenging to meet, and ran the risk of putting pressure on the quality of any assessment of the applications when they were received.37

1.10 A total of 58 applications for funding were received by the department by the closing time of 2:00 PM (AEST) on 12 June 2014.38 The department continued to receive applications until November 2014. All applications received, including the 27 received after the closing time and date, were assessed by the department.39

1.11 As at 8 May 2015, $19.0 million had been approved to fund 73 applicants (146 separate projects) under Round One of the Safer Streets programme. This included decisions made by the Minister for Justice in:

- December 2013, prior to the commencement of the funding round, to approve funding of $250 000 for a project involving the Gold Coast City Council;40

- June 2014, to approve $350 000 in funding for a project to be undertaken by Campbelltown City Council;

- July 2014, to approve funding of $17 458 741 for 75 applications, comprising 136 separate projects (to be delivered by 63 applicants);

- October 2014, to approve funding of $753 454 for six additional projects (to be delivered by six applicants); and

- January 2015, to approve funding of $155 000 for two additional projects (to be delivered by two applicants).

1.12 As at 8 May 2015, three invited organisations (Glen Eira City Council, Mitchell Shire Council and Macedon Ranges Shire Council) had declined funding and one application (Greater Toukley Vision) was not recommended for funding. In January 2015, the Minister approved a project to be delivered by the Bentleigh Traders Association to replace (in part) the project that was to be delivered by Glen Eira City Council.41 In addition, the department has advised that Greater Toukley Vision submitted another revised application for funding on 17 March 2015.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

1.13 In July 2014, the Auditor-General received a request from the Hon. David Feeney MP, the Shadow Minister for Justice, to undertake an audit of the Safer Streets programme. In respect to the first funding round that was focused on Coalition election commitments, Mr Feeney raised a number of concerns about the establishment of the programme and selection of projects, eligibility for organisations to apply for funding and political neutrality in the selection process. Similar concerns were subsequently reported in the media. After undertaking preliminary inquiries in relation to the matters raised, the Auditor-General decided to undertake a performance audit of the Safer Streets programme.

1.14 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the award of funding under the first round of the Safer Streets programme.

Audit criteria

1.15 The audit criteria reflected relevant policy and legislative requirements for the expenditure of public money and the grants administration framework, including the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs, which from 1 July 2014 were replaced by the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines, CGRGs). In this respect, and as previously outlined by ANAO42, the grants administration framework was developed based on a recognition that the statutory obligations applying to the approval of spending proposals derived from election commitments are no different from those attached to the approval of any other spending proposal.43 In this context, in deciding upon the requirements of the grants administration framework, government accepted recommendations that:

- guidelines be developed for all grant programmes, including those established to fund election commitments; and

- Ministers receive and consider agency advice on the merits of proposed grants (as assessed against the relevant programme guidelines) before taking any decisions on the award of individual grants, and this requirement should apply to all grant spending proposals including those designed to satisfy commitments made in the context of election campaigns.

1.16 The audit criteria also drew upon ANAO’s administration of grants Better Practice Guide (the June 2010 version of this Guide was available at the time the Safer Streets programme was implemented, and was replaced in December 2013 with an updated Guide).

1.17 More specifically, to form a conclusion against the audit objective, ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the robustness of the processes by which projects were identified for funding consideration;

- the effectiveness of the merit assessment process undertaken by the Attorney-General’s Department to satisfy itself that applicants meet the Safer Streets programme’s eligibility requirements and criteria;

- the quality of the advice provided by the department to the Minister and funding decisions as to whether projects:

- met the identified programme objective, priorities, and criteria; and

- represented value with public money; and

- the distribution of funding (including in electorate terms44) and the development of effective funding agreements with project proponents, that will allow the department to adequately oversight the delivery of funded projects and assess whether those projects have been successful in preventing, detecting and deterring crime.

Audit scope and methodology

1.18 The audit examined the key elements of the first funding round of the Safer Streets programme that opened for applications in May 2014, with funding decisions made in June 2014, July 2014, October 2014 and, January 2015. The audit scope also included the announcement of funding decisions and the negotiation and signing of grant agreements.

1.19 The audit examined departmental records on the design, implementation and administration of the programme, including applications and assessment records for all applications received.45 To inform the audit, ANAO also reviewed the assessment approach developed and applications received for the former Government’s National Crime Prevention Fund (NCPF), for which a competitive funding round had been undertaken.46

1.20 In addition, ANAO interviewed relevant departmental staff and examined email records for relevant staff from the Attorney-General’s Department and from the office of the Minister for Justice.

1.21 The audit has referenced the grants framework that was in place at the time that the programme operated. Initially (for example, in respect to the development of the programme guidelines), this involved the Finance Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act), Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997 (FMA Regulations) and the CGGs. The financial framework changed in July 2014, prior to the approval of the first tranche of successful applications. Specifically, implementation of the grants-related elements of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) took effect from 1 July 2014. In this respect, similar arrangements exist under the current framework (PGPA Act and the CGRGs).

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to ANAO of $517 000.

Report structure

1.23 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Structure of the report

|

Chapter title |

Chapter overview |

|

2. Programme Design and Access |

Examines the design of the programme including the funding arrangements, and the development of documentation for the delivery of the programme. |

|

3. Identifying Candidate Proposals and Assessing Eligibility |

Examines the identification and confirmation of the population of the election commitments allocated for delivery under the Safer Streets programme. It also examines the department’s assessment of the eligibility of those proposals considered for programme funding. |

|

4. Assessment of Applications |

Analyses the department’s approach to assessing applications against the selection criteria as outlined in the programme guidelines. |

|

5. Advice to the Minister and Negotiation of Funding Agreements |

Examines the quality of the advice provided to the Minister for Justice as to which applications should be approved for funding, as well as the development and negotiation of funding agreements with successful applicants. |

2. Programme Design and Access

This chapter examines the design of the programme including the funding arrangements, and the development of documentation for the delivery of the programme.

Introduction

2.1 As is common during election campaigns, Ministers and other government and non-government candidates make various announcements that represent undertakings to provide certain funding, services or facilities in the event the relevant party is elected or re-elected.47 The importance to governments of delivering upon their election commitments is recognised. At the same time, the use of public money to fulfil such commitments may only occur in accordance with the financial framework that governs the expenditure of funds. Accordingly, ANAO examined the extent to which the department designed an appropriate framework for administering the programme through the:

- programme access arrangements;

- programme guidelines; and

- key programme documentation.

Programme access arrangements

2.2 For grant programmes, a key element of the financial framework at the time the programme was being designed was provided by the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs).48 The CGGs did not differentiate between grants based on election commitments and other grant proposals, instead providing a principles-based framework for developing and administering granting activities.

2.3 The CGGs advised that competitive, merit-based selection processes should be used to allocate grants (unless otherwise agreed by a Minister, Chief Executive or delegate). Further, where a method other than a competitive merit-based selection process was planned to be used, agency staff should document why this approach would be used.49 A similar obligation has been retained in the CGRGs, with paragraph 11.5 stating:

Competitive, merit-based selection processes can achieve better outcomes and value with relevant money. Competitive, merit based selection processes should be used to allocate grants50, unless specifically agreed otherwise by a Minister, accountable authority or delegate. Where a method, other than a competitive merit-based selection process is planned to be used, officials should document why this approach will be used.

2.4 In its 29 April 2014 briefing to the Minister for Justice, the department outlined its proposed approach to implementing the first round of the Safer Streets programme through a non-competitive selection process. The advice noted that the programme would be implemented in line with CGG requirements, but did not specifically advise the Minister on the need to document the reasons for the implementation of the non-competitive selection process. The department did not otherwise document the reason for employing a non-competitive process.

Programme guidelines

2.5 A key obligation under both the CGGs and CGRGs is for all grant programmes to have guidelines in place.51 Programme guidelines play a central role in the conduct of effective, efficient and accountable grants administration, by articulating the policy intent of a programme and the supporting administrative arrangements for making funding decisions.52 Reflecting their importance, the programme guidelines represent one of the policy requirements that proposed grants must be consistent with in order to be recommended for funding.53

2.6 In April 2014, the department provided a briefing to the Minister to advise him of the approach and timetable for implementation of the Safer Streets programme. As part of this briefing, the department attached a near-final draft version of the proposed programme guidelines. The department also sought input on the programme guidelines and risk assessment from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) and the Department of Finance (Finance), as required by the CGGs. There was no other external stakeholder consultation on the development of the guidelines.

2.7 The department’s assessment of the granting activities and proposed guidelines resulted in a risk rating of ‘low’ being agreed with PM&C and Finance. The programme guidelines were approved by the Minister on this basis.54 The ‘low’ rating was based on controls and mitigation strategies that the department indicated would be implemented. Table 2.1 outlines the risks and control/mitigation strategies on which the ‘low’ risk rating was based.

Table 2.1: Identified risks and mitigation strategies

|

Risk |

Control/Mitigation Strategy |

|

Programme seen as a wasteful use of resources |

Applicants are required to demonstrate that their project meets the requirements of the programme guidelines so that is it clear that funded projects are responding to the need identified by the Government. |

|

Grants awarded to ineligible applicants |

Programme guidelines clearly set out eligibility criteria; online application is designed to require applicants to demonstrate their eligibility and provide supporting documentation; eligibility of applicants is confirmed before applications are accepted for assessment and validated during the assessment process. |

|

Grants awarded for projects or activities that are inconsistent with the objectives of the programme |

Programme guidelines clearly state the purpose of the programme and define eligible project features; assessment criteria are drawn from these requirements; application assessments are reviewed by more experienced staff to ensure equity and consistency; limit funding recommendations to only high quality projects; retain surplus funds for allocation during later funding rounds. |

|

Applicants treated inequitably in the appraisal and awarding of grants |

All application assessments are reviewed by senior/more experienced staff to ensure equity and consistency in assessment; comparative review of assessments is undertaken to ensure consistency and equity. |

Source: Departmental risk assessment.

2.8 As is discussed further in Chapter 4, many of these mitigation strategies identified by the department were not implemented and the alternate approaches taken by the department to the assessment of applications against the eligibility and assessment criteria led to the risks in each of the four identified categories being realised.

2.9 Prior to seeking formal approval for the programme guidelines from the Minister for Justice on 2 May 2014 and following a request by the Minister’s office to simplify the guidelines, the department proposed a range of changes. These changes included removing key statements that would have assisted the department to effectively consider and make appropriate recommendations on the individual and relative merits of funding applicants. There was no reason recorded for these changes or of advice being provided to the Minister on how the changes would impact on the programme. Table 2.2 outlines the key statements removed from the proposed programme guidelines.

Table 2.2: Key statements removed from the proposed guidelines

|

Section |

Statements removed from the proposed programme guidelines |

|

Section 2—Programme objectives and key principles |

Removal of the statement that projects must have:

|

|

Section 3—Eligibility |

Removal of the statement that grant applicants provide evidence to demonstrate the need for improved security due to high levels of crime and anti-social behaviour; and Restricting eligibility to those organisations previously identified and invited to be eligible under Round One. [ANAO emphasis] |

|

Section 3.2—Projects not eligible for funding |

Removal of the statement that projects will not be eligible where they do not meet the selection criteria and do not reflect evidence based good practice. |

|

Section 5—Application and assessment process |

Removal of the statement that project proposals will be assessed by the department to determine the need for the project.1 |

|

Section 6—Selection criteria |

Removal of the statement that the project demonstrate need through demonstrated high crime rates, as evidenced by law enforcement or Australian Bureau of Statistics data, in the area where the project is to be delivered. |

|

Section 8—Managing the project |

Removal of the statement that the grant recipient must provide a statistical comparison of outcome/crime rates in the project delivery location pre and post project. |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

Note 1: Note that under section 3—Eligibility—’grant applicants must provide evidence to demonstrate the need’. [ANAO emphasis]

2.10 In relation to Table 2.2, for example:

- section 3.2 of the proposed guidelines had included a clear statement that projects would not be eligible if they did not meet the selection criteria. Retaining such a statement would have emphasised to applicants the importance of the selection criteria (see Table 2.6), as well as encouraging the department to have established minimum scores against each of the selection criterion and to have adopted a sound approach to conducting assessments. As outlined in Chapter 4, minimum scores were not set, some applications were recommended for funding notwithstanding that they had scored less than five out of 10 against one or more criteria, and the department’s assessment methodology did not include addressing each element of each selection criterion or obtaining sufficient information to assess applications against the criteria;

- removing the statement in section 5 of the proposed guidelines could have encouraged applicants to rely upon the status of their project as an election commitment as likely to lead to funding being forthcoming, irrespective as to whether they had provided information to the department for it to assess against the programme guidelines. In this respect, the department recorded in its assessment of 55 applications (65 per cent) that the applicant provided limited or no information against one or more of the selection criteria; and

- the requirement that had been included at section 6 of the proposed guidelines (that the project demonstrate need through ‘high’ crime rates, in the area where the project is to be delivered) was consistent with the policy announcements for the programme that funding would be targeted at crime ‘hot spots’ based on evidence. Retained in the guidelines was a lower standard approach55, which related to applicants providing ‘evidence’:

- of a need for the project, but without the guidelines emphasising that this evidence needed to be credible (such as being from law enforcement or statistical agencies). In this context, some applications made no reference to any evidence supporting the need for the project, with the departmental assessment instead referring to letters of support for the application as being indicative of there being a project need. Overall, 76 per cent of applications assessed did not provide official crime statistics to demonstrate the need for the project; and

- that was not specific to the area where the project was to be delivered. In this respect, for one quarter of those applications where statistics were provided to support the need for the project, those statistics were not specific to the area nominated in the application.

2.11 In addition, on 30 April 2014, prior to the Minister’s approval of the guidelines (on 2 May 2014), the department received a request from the Minister’s office that the ‘election commitment list be removed from the programme guidelines’. The list was still being finalised in early May 2014, with one project added and several changes to the identity of applicants being made prior to invitation letters being sent out on 15 May 2014. Removing the list provided flexibility, which allowed projects to be substituted where organisations identified prior to October 2013 declined the invitation to apply for funding. To support a transparent application process, it was important for the department to maintain an agreed list that appropriately reflected the election commitments.56

Content of the programme guidelines

2.12 The guidelines for Round One of the Safer Streets programme identified the purpose of the programme; the objectives/priorities; eligibility requirements; assessment criteria and associated weightings; assessment and approval processes; programme timeframes; and complaints handling. However, the guidelines did not address or provide clarity on:

- roles and responsibilities, management and oversight of the programme within the department;

- processes for considering and approving project scope changes or variations to projects;

- eligibility relating to project management and contingency costs as part of the applicant’s overall project budget;

- eligibility of projects that were not providing CCTV or lighting (or infrastructure relating to these activities), such as incentive schemes, graffiti trucks, surf safety measures and emergency beacons; and

- how, in practice, the applications would be assessed. For example, the guidelines only provided a general statement that project proposals would be assessed by the department to: determine the value for money, including efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of public money; the crime prevention benefits and the capacity of the organisation to manage the project and grant funds.57

Assessment criteria

2.13 As noted in ANAO’s Better Practice Guide on grants administration, and reflected in the CGGs, it is important that programme guidelines identify those threshold requirements that must be satisfied for an application to be considered for funding. Well-constructed threshold or eligibility criteria are straightforward, easily understood and effectively communicated to potential applicants, and the relevant programme’s published guidelines should clearly state that applications that do not satisfy all eligibility criteria will not be considered.58

2.14 Section 3 of the Safer Streets programme guidelines outlined the target group for funding as being ‘organisations that were identified before October 201359 to deliver specific commitments’. The guidelines further outlined that:

- identified organisations would be invited by the Attorney-General’s Department to submit an application for funding in May 2014; and

- grant applicants must provide evidence to demonstrate need for improved security due to crime and anti-social behaviour affecting local communities, in particular local retail, entertainment and commercial precincts.60 [ANAO emphasis]

2.15 Section 6 of the guidelines also outlined that the assessment of projects would be based on the eligibility criteria identified in Table 2.3. It was further stated in section 6 that applications that ‘do not pass the eligibility criteria will not be assessed any further’.

Table 2.3: Eligibility criteria

|

Weighting |

Eligibility criteria |

|

Pass/Fail |

Eligibility of the applicant organisation—as identified prior to October 2013. |

|

Pass/Fail |

Eligibility of the proposed project—its consistency with the programme’s key objectives and principles. |

Source: Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, section 298 Programmes of Expenditure, Safer Streets programme 2014–15 to 2016–17, Guidelines for Funding Round One, p. 7.

2.16 Although the programme guidelines included specific sections identifying eligibility and threshold criteria, additional statements were included in other sections of the guidelines that also represented mandatory requirements in order to receive funding. This involved the use of expressions such as ‘must’, ‘must not’, ‘will’, and ‘will not’. Table 2.4 identifies various sections of the programme guidelines that include eligibility requirements for applicants to meet, and which the department did not assess as eligibility criteria.

Table 2.4: Additional requirements outlined in the programme guidelines

|

Section |

Requirement |

Application Form addressed the requirement |

Assessment Form addressed the requirement |

|

2 |

projects must address the priorities of the programme; and |

Y |

N |

|

establish performance measures to assess the impact of the project. |

Y |

Y |

|

|

3 |

funding will not be provided for any development costs associated with an application (for example, preparation of applications, the cost of a survey to establish the need for a project, and costs of obtaining permits and approvals to facilitate implementation). |

N |

Y |

|

4.2 |

applicants must: establish that communities identified in their application are at risk of vandalism and property crime and have special security needs and/or that members of the community face harassment and risks to their personal safety. |

N |

Y |

|

applicants must demonstrate how the proposed project would address the identified risks and security needs. |

N |

Y |

|

|

applicants must demonstrate that they possess the capacity to cover any ongoing costs associated with the security infrastructure being applied for (as funding under the programme is non-recurrent). |

N |

Y |

|

|

applicants must demonstrate that the project represents good value for money. |

Y |

Y |

|

|

5 |

all completed applications must be lodged through the department’s online application process; and incomplete applications will not be assessed.1 |

N |

N |

|

7 |

applications must be: submitted on the official forms provided on the website; received in full; and lodged via the electronic lodgement facility on or before the closing date. |

partial |

N |

Source: Safer Streets programme 2014–15 to 2016–17, Guidelines for Funding Round One, April 2014.

Note: The assessment form required that applicants submit the application in full on the closing date but did not specify that the official form was to be used. [ANAO emphasis]

Note 1: This statement that incomplete applications will not be assessed contradicts a later reference on page 7 of the Safer Streets programme guidelines that states that ‘late or incomplete applications may not be considered’. [ANAO emphasis]

2.17 It is important that programme guidelines clearly identify eligibility requirements, such that applicants can easily comprehend and address those requirements. In this context, the department’s approach of spreading eligibility statements between sections 3 and 6 and outside of the explicitly identified eligibility criteria did not assist in ensuring applicants were aware of all mandatory requirements, or that all such requirements were consistently addressed in the assessment of applications.61

2.18 The design of an application form should be tailored to assist applicants to provide information in respect of all selection criteria and eligibility requirements identified in the programme guidelines. In this regard, the application form developed by the department did not require applicants to provide all mandatory information for the application to be considered complete. Specifically, as identified in Table 2.4, the application form did not provide the applicant the opportunity to provide information against four of the additional eligibility requirements. This is reflected by the fact that only one application provided all of the required documents as listed in the guidelines.62

2.19 Further, in respect to funding eligibility, section 3.2 of the programme guidelines outlined those projects that would be ineligible for funding. In particular, only those organisations identified prior to October 2013 to deliver specific election commitments, and invited by the department to submit an application for funding, were eligible to apply for funding under the first funding round. It was also a condition that grant funding under Round One was provided through a targeted round; limited to the amount of funding already committed by the Australian Government; that the funding be non-recurrent; and that it be conditional on projects being completed by 30 June 2017.63

Suitability of the application form

2.20 The design of application forms for grant programmes should re-enforce the assessment process by seeking sufficient information to allow for a proper assessment of the merits of grant proposals, including by specifically asking applicants to address the requirements set out in the programme guidelines, particularly the key elements of the assessment criteria. Although the Safer Streets programme guidelines included specific information requirements, as shown in Table 2.5 the application and assessment forms were not developed in such a way that these requirements would be met by the applicant or fully assessed by the department.

Table 2.5: Information required by the guidelines—advice to the Minister

|

Required information: |

Application Form addressed the requirement |

Assessment Form addressed the requirement |

|

Details and credentials of the organisation (to demonstrate the capacity of the organisation to successfully manage a crime prevention project and administer crime prevention grant funds). |

Y |

Y |

|

Details of the project. |

Y |

Y |

|

The need for the project and its intended long-term crime prevention benefits. |

Y |

Y |

|

Financial information including quotations, cost estimates and budgets (to determine value for money). |

Y |

Y |

|

Project timeframes (including identification of key milestones and the proportion of project funding for each milestone). |

Y |

N |

|

Project delivery information including project and business plans. |

N |

N |

|

Statutory and other approvals required if relevant to the project (for example, planning approvals or permits). |

Y |

N |

|

A project evaluation framework, including appropriate performance measures to assess the impact of the project. |

N1 |

N |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental information.

Note 1: The application form contained an ‘Evaluation’ section that included two high level questions requiring the applicant to discuss key performance indicators and how the success of the activity would be evaluated. This section did not, however, require the applicant to provide evidence of an evaluation framework.

2.21 Further, the application form contained vague guidance in relation to the provision of supporting information. For example, the application form did not clearly convey to applicants the importance of providing up to date and activity-specific quotations or that the provision of quotations was required under the programme guidelines. Instead, the end of the application form stated ‘please ensure [ANAO emphasis] you attach the below documents to support your application’, accompanied by a checklist of documents, including: evidence of insurance; a copy of the organisation’s incorporation certificate or legal documentation; quotations for capital expenditure; and evidence of not-for-profit status. In this respect, the application form did not make clear that quotations would be a key consideration in the assessment process, as was indicated by the assessment criteria and the programme guidelines more generally.

Safer Streets selection criteria

2.22 As outlined in the programme guidelines, the objective of the Safer Streets programme was to ‘improve community safety and security, both in real terms and in perceptions of community safety, and reduce street crime and violence’. In this context, the assessment of eligible projects was to be based on the selection criteria and weightings of assessment scores outlined below in Table 2.6. The six selection criteria were appropriate for the first round of the Safer Streets programme.

Table 2.6: Selection criteria for the Safer Streets programme

|

Criterion |

Weighting (%) |

Selection criteria |

|

1 |

25 |

Demonstrated need for, and the potential impact of, the proposed project. |

|

2 |

25 |

Consistency with proven good practice in crime prevention, including demonstrating the link between the project’s key interventions and the likely community safety and crime prevention benefits of the project and the enduring value to the community. |

|

3 |

20 |

Financial information including quotations, cost estimates and budgets and the overall value for money of the project. |

|

4 |

10 |

Organisational ability to collect data to measure the impact and success of the project and the range of data to be collected. |

|

5 |

10 |

Organisational capacity of the applicant organisation (including the financial viability of the organisation, demonstrated capacity to successfully manage the project and demonstrated capacity to administer grant funds). |

|

6 |

10 |

Organisational ability to manage risks associated with the proposed activity. |

Source: Safer Streets programme guidelines, April 2014.