Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Australian Taxation Office’s Management and Oversight of Fraud Control Arrangements for the Goods and Services Tax

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Effective fraud control arrangements are integral to protect the integrity of the tax system, maintain public confidence and prevent a culture of non-compliance.

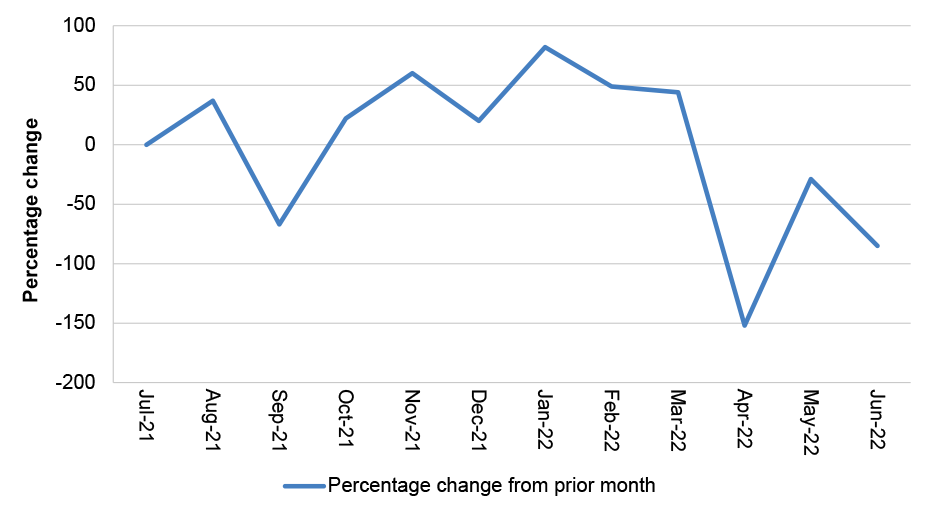

- During 2021–22 the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) identified a significant increase in attempts to obtain false Goods and Services Tax (GST) refunds. This audit will provide assurance to Parliament over the ATO’s management and oversight of fraud control arrangements for the administration of GST.

Key facts

- GST collected by the ATO has increased from $48.4 billion in 2012–13 to $81.4 billion in 2022–23.

- The ATO processed 11.2 million Business Activity Statements in 2022–23.

What did we find?

- The ATO’s management and oversight of fraud control arrangements for the GST is partly effective.

- The ATO has implemented partly effective strategies to prevent GST fraud, but the framework for assessing and managing GST fraud risk is not fit for purpose.

- The ATO has implemented largely effective strategies to detect and deal with GST fraud but does not have a strategy to deal with large-scale fraud events.

- The ATO’s oversight, monitoring and reporting of GST fraud is partly effective, as roles and responsibilities are not clear.

What did we recommend?

- There were five recommendations to the ATO aimed at strengthening assurance and improving responses to fraud events.

- The ATO agreed to all five recommendations.

$2.0bn

estimated Operation Protego GST fraud (April 2022 to 30 June 2023).

>57,000

estimated Operation Protego participants in GST fraud (April 2022 to 30 June 2023).

4,745

tip-offs related to GST fraud (2019–20 to 2022–23).

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) administers the Goods and Services Tax (GST), and in 2022–23 collected $81.4 billion of GST and raised an additional $6.1 billion in GST liabilities.

2. All Commonwealth entities are required to have fraud control arrangements in place to ensure proper use of public resources, minimise losses and maintain public confidence.1 GST fraud can undermine the integrity of the tax system, reduce the revenue available for the Commonwealth to make GST payments to the states and territories and penalise taxpayers who do the right thing. Preventing and detecting GST fraud may contribute to the ATO’s purpose of ‘fostering willing participation in the taxation and superannuation system’.2

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. All Commonwealth entities are required to have fraud control arrangements in place in accordance with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework. Preventing and detecting GST fraud is integral for minimising loss of GST revenue available for the Commonwealth to make payments to the states and territories and maintaining public confidence in the tax system to support voluntary compliance.

4. This audit provides assurance to the Parliament that the ATO has effective management and oversight of fraud control arrangements for the administration of GST to protect the integrity of the tax system.

Audit objective and criteria

5. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s management and oversight of fraud control arrangements for the Goods and Services Tax.

6. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted:

- Has the ATO implemented effective strategies to prevent GST fraud?

- Has the ATO effectively implemented strategies to detect and respond to GST fraud?

- Has the ATO implemented effective arrangements to oversee, monitor and report on fraud control arrangements for the administration of GST?

Conclusion

7. The ATO’s management and oversight of fraud control arrangements for the GST is partly effective. The lack of clarity for roles and responsibilities, inadequate implementation of assurance requirements, and absence of a holistic and contemporary view of GST fraud risks undermines the effectiveness of efforts to prevent, detect and respond to fraud events in a timely manner and minimise fraud losses.

8. The ATO has implemented partly effective strategies to prevent GST fraud. The ATO has established an enterprise framework for fraud, but it is not fit for purpose and is not operating as intended. The ATO assesses fraud risks and produces an annual fraud and corruption control plan. It is not evident how the ATO’s 2023 Fraud Control and Corruption Plan deals with identified external fraud risks as required under paragraph 10(b) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule. The ATO has implemented mandatory training which includes fraud awareness content and monitors compliance with its requirement for ATO employees and contracted individuals to complete the mandatory training. The ATO raises awareness of GST fraud among external stakeholders through publishing information on its website and social media accounts.

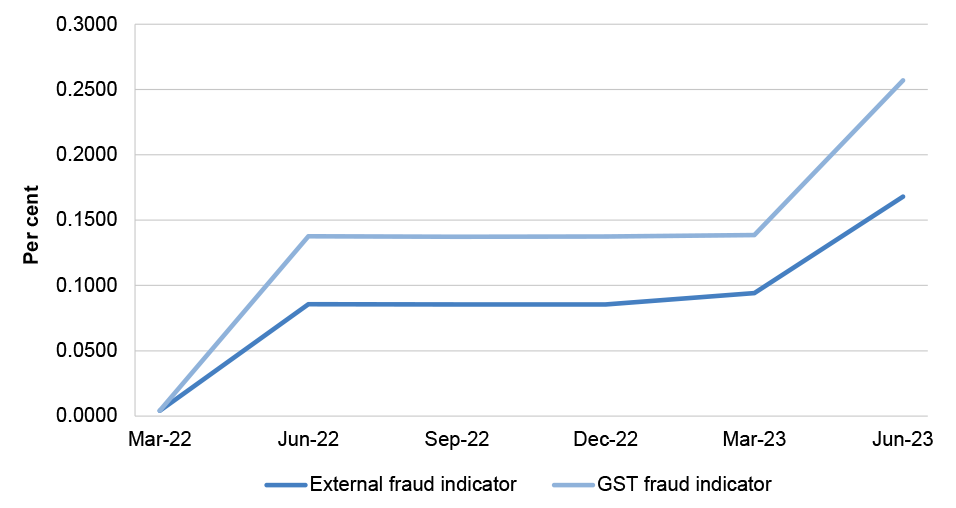

9. The ATO’s processes to detect and deal with suspected GST fraud are largely effective. The ATO has implemented effective processes to confidentially report allegations of suspected fraud. The ATO has procedures to assess and refer ‘tip offs’ of external fraud to the relevant business line for further action, and to assess and investigate allegations of suspected internal fraud. The ATO has methods to detect potential GST fraud. The ATO has processes for investigating suspected fraud and taking action but does not have a procedure to respond to a large-scale fraud event.

10. The ATO has partly effective governance arrangements for GST fraud control. There is a lack of clarity regarding ownership of GST risks and artefacts to support risk assessment, monitoring and treatment are incomplete or in draft. The ATO provide reports to its Audit and Risk Committee through the ATO’s conformance reporting process and dashboard. The benchmark used in the dashboard reporting is not fit for purpose as it is a measure of fraud and error for government payments. In contrast, the ATO’s fraud indicators reported in the dashboard are the proportion of tax lodgments that are referred for investigation.

Supporting findings

Goods and Services Tax fraud prevention

11. The ATO has established an enterprise framework for fraud, but it is not fit for purpose and is not operating as intended. The ATO has established an external fraud risk owner and an internal fraud risk owner. The Commissioner of Taxation has issued two Chief Executive Instructions (CEIs) setting out the requirements for managing fraud — one for external fraud and one for internal fraud. The CEIs do not reflect the roles and responsibilities in place in the ATO’s current structure. The ATO is in the process of clarifying roles and responsibilities for managing fraud risk and making the relevant changes to its CEIs. The ATO’s conformance reporting process for external fraud is not fit for purpose. The ATO Audit and Risk Committee relies on this information to provide assurance to the Commissioner of Taxation as the ATO’s accountable authority. The ATO advised the ANAO in June 2023 that it is planning to redesign the external fraud conformance process to support the revised roles and responsibilities framework. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.20).

12. The ATO assesses fraud risks and produces an annual fraud and corruption control plan. It is not evident how the ATO’s 2023 Fraud Control and Corruption Plan deals with identified external fraud risks (including GST fraud risks) as required under paragraph 10(b) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule, or whether the ATO’s controls and strategies for external fraud are commensurate with assessed fraud risks as suggested in the fraud guidance. The ATO has completed internal fraud and corruption risk assessments, largely within the two-year timeframe suggested in the Commonwealth fraud guidance. The ATO has not completed external fraud risk assessments within the two-year timeframe required by its external fraud governance framework. No ATO business line has completed a business line level fraud risk assessment relevant to GST fraud since 2020. As of June 2023, the ATO was working towards clarifying the roles and responsibilities for assessing and managing GST fraud risks. (See paragraphs 2.21 to 2.53).

13. The ATO has documented a clear and widely available definition of what constitutes fraud in its Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023. The ATO’s external and internal fraud CEIs require ATO employees and contracted individuals to complete ‘mandatory training’, which includes three courses with fraud awareness content. The ATO monitors compliance with its requirement that staff complete mandatory training and reports completion rates for these three courses to the ATO Audit and Risk Committee. (See paragraphs 2.54 to 2.63).

14. The ATO has established external communications products that raise GST fraud awareness among external stakeholders. Information from these products is contained on the ATO’s website and social media posts. (See paragraphs 2.64 to 2.68).

Goods and Services Tax fraud detection, investigation and response

15. The ATO has processes for ATO officials and members of the public to confidentially report allegations of suspected GST fraud. The ATO has documented instructions and procedures for ATO officials to assess reports of suspected external fraud (including suspected GST fraud) and to refer these reports to the relevant business line for further investigation. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.9).

16. The ATO has largely appropriate methods to detect potential GST fraud. The ATO’s measures of effectiveness for GST fraud detection have improved over time. Registers of controls used to detect potential GST fraud are dispersed across ATO business lines and the ATO does not maintain a centralised register. The dispersed nature of GST controls means the ATO relies on internal committee discussions to draw together a ‘whole of GST product’ perspective on the effectiveness of these methods, rather than on collated or aggregated data. The Contemporising GST Risk Models (CGRM) project involves a redesign of existing risk models to detect Business Activity Statement refunds that are incorrect, based on a risk likelihood score. The CGRM project ran 12 months behind schedule, with models being deployed over time from May 2021 to January 2022. The ATO is assessing the effectiveness of two risk models deployed under the CGRM project (the identity crime and the incorrect reporting models) through a random audit program. This project is running eight months behind schedule. The ATO utilises other methods to detect potential GST fraud including data matching, referrals from financial institutions and using justified trust to assure GST compliance of large businesses. (See paragraphs 3.10 to 3.33).

17. The ATO has largely appropriate processes in place for investigating suspected fraud and taking appropriate action. The ATO has documented procedures in place to investigate suspected internal fraud and external fraud and is in the process of updating documents to meet the Australian Government Investigations Standard 2022 requirements. The proportion of Integrated Compliance cases and audits resulting in a GST adjustment was 32.4 per cent of cases and 81.9 per cent of audits completed in 2022–23. The ATO did not have a procedure to respond to a large-scale external fraud event such as the GST fraud event that led to the ATO’s ‘Operation Protego’ response from April 2022 to October 2023. The ATO publicly reports the results of tax crime prosecutions, including prosecutions for GST fraud, on the ATO website. (See paragraphs 3.34 to 3.50).

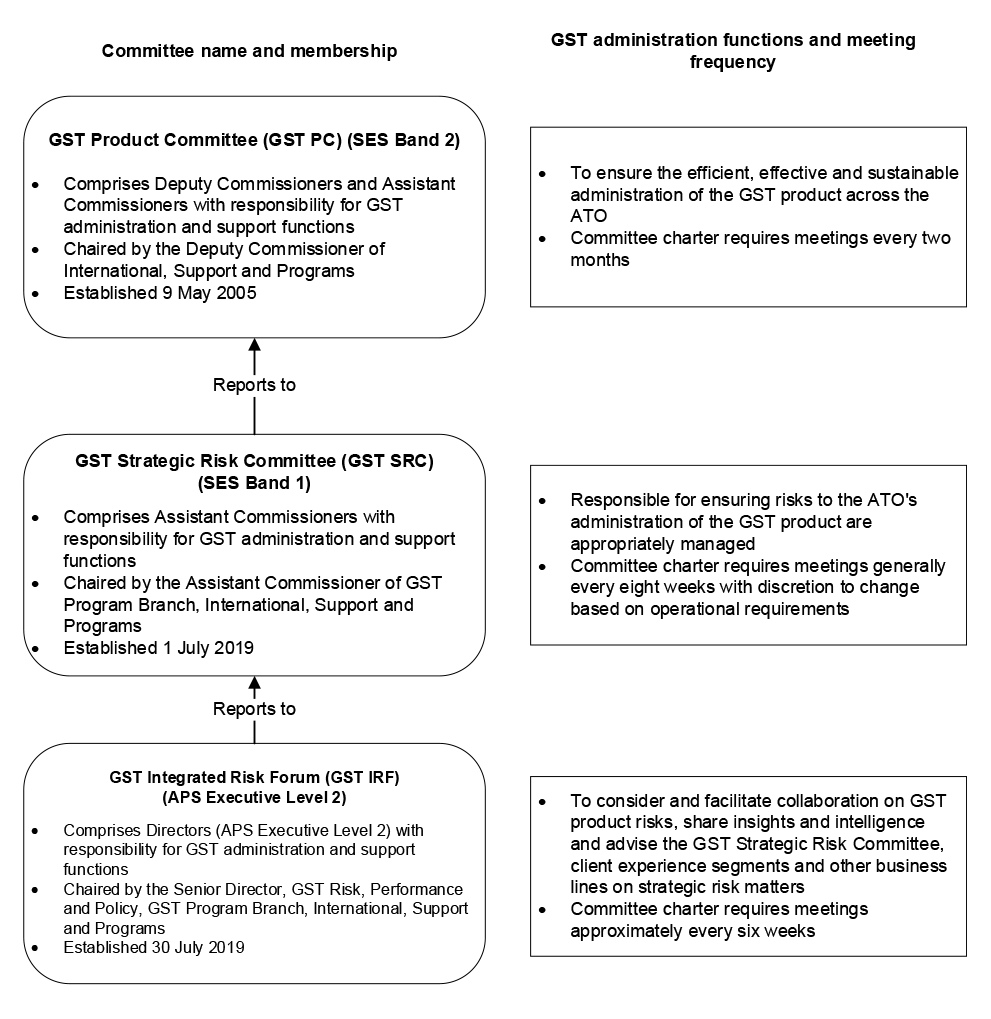

Oversight, monitoring and reporting

18. The ATO’s governance and reporting arrangements for GST fraud control are partly effective. The ATO has identified there is a lack of clarity regarding accountability for GST fraud control and after two years of committee discussions this issue remains unresolved. Interim arrangements establishing a GST Fraud Advisor were endorsed by the GST Product Committee (an ATO SES Band 2 committee with responsibility for GST administration within the ATO) in September 2023, with a risk assessment on fraud in the GST system along with a deep dive on fraud in the GST system to be completed in early 2024. The ATO provides reports to its Audit and Risk Committee through the ATO’s conformance reporting process and dashboard. The benchmark used in the dashboard reporting is not fit for purpose as it is a measure of fraud and error for government payments. In contrast, the ATO’s fraud indicators reported in the dashboard are the proportion of tax lodgments that are referred for investigation. (See paragraphs 4.2 to 4.35).

19. The ATO has met the external reporting requirements of the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework by providing the required Information to the Australian Institute of Criminology in the form required by the specified deadline. (See paragraphs 4.36 to 4.39).

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.19

The Australian Taxation Office, as a matter of priority, should finalise its work on:

- clarifying and documenting the roles and responsibilities for fraud prevention, detection, and treatment;

- redesigning the external fraud conformance process to support the revised roles and responsibilities; and

- making the necessary changes to the external fraud and internal fraud Chief Executive Instructions.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.36

The Australian Taxation Office should conduct and document assessments of its GST fraud risks regularly and ensure that it has a contemporary and holistic view of its GST fraud risks.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.51

The Australian Taxation Office ensures that its fraud control and corruption plans are based on identified fraud risks that are documented in risk assessments.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.48

The ATO should develop and implement a response for large-scale fraud events that do not meet the criteria specified in the extant Integrity Incident Response Framework. The response should encompass:

- the ability to monitor early warning signals from the disparate fraud detection methods across ATO business lines, including ‘tip-offs’ received by the ATO Tax Integrity Centre;

- identification of escalation triggers and the pathways that will be followed to develop an ATO response;

- a clear allocation of decision-making authority and accountability for initiating and finalising a rapid response;

- a prioritisation approach for action, emphasising the prevention and containment of revenue leakage;

- actions to recover losses; and

- criteria to evaluate the success of the framework’s use to contain fraud events, and the ability to adjust the framework in response to evaluation findings.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.32

The Australian Taxation Office should:

- consider an alternative benchmark for ATO fraud indicators; and

- remove references to the ‘AGD fraud benchmark’.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed

Summary of entity response

The ATO welcomes the ANAO’s audit into its fraud control arrangements for the administration of the GST. Fraudsters’ tactics continuously develop, and the environment is rapidly evolving. The ATO, like other tax administrations and organisations around the world, continues to face increasing fraud attacks, often seeking to subvert the improved client experiences offered through digitalisation.

Protecting the ATO’s systems and the broader tax ecosystem from fraud is a constant fight, and one that the ATO takes extremely seriously. The ATO’s internal and external intelligence sources, risk models and pre-issue integrity activities identified a significant increase in attempts to obtain false GST refunds from December 2021. We responded to the threat and publicly announced Operation Protego in May 2022. The operation successfully contained this fraud and significantly strengthened a range of system controls.

In July 2023, we established the Fraud and Criminal Behaviours business line to focus on further protecting the system and clients against fraud and have since implemented a range of additional fraud defences.

We will continue to implement and build on the recommendations identified by the ANAO, which we consider will support the already improved management and assurance of fraud control arrangements for the GST.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

20. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) administers the Goods and Services Tax (GST). In accordance with paragraph 25 of the Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations (IGAFFR), the Commonwealth makes GST payments equivalent to the revenue received from the GST to the states and territories for any purpose, with the states and territories reimbursing the Commonwealth for the ATO’s cost of administering the GST.3 The accountability and performance arrangements between the ATO and the Council on Federal Financial Relations as required under the IGAFFR have been established under the GST Administration Performance Agreement.4 The framework enabling the ATO to administer the GST is detailed in Appendix 3.

1.2 In 2022–23 the ATO collected $81.4 billion of GST and raised an additional $6.1 billion in GST liabilities.5 The ATO’s cost of administering the GST for 2022–23 was $653.3 million.

1.3 The Australian Government defines fraud as:

Dishonestly obtaining a benefit or causing a loss by deception or other means.6

1.4 Fraud against the Commonwealth can be committed by officials or contractors (internal fraud) or by external parties such as clients, service providers, other members of the public or organised criminal groups (external fraud). All Commonwealth entities are required to have fraud control arrangements in place to ensure proper use of public resources, minimise losses and maintain public confidence.7

1.5 GST fraud can undermine the integrity of the tax system, reduce the revenue available for the Commonwealth to make GST payments to the states and territories and penalise taxpayers who do the right thing. Preventing and detecting GST fraud may contribute to the ATO’s purpose of ‘fostering willing participation in the taxation and superannuation system’.8

Key Commonwealth requirements on fraud control

1.6 The requirements for Australian Government entities to have fraud control arrangements in place are contained in the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework (the Framework), developed under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).9

1.7 The Framework comprises three tiered documents, section 10 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (the fraud rule10), the Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy (the fraud policy) and Resource Management Guide No. 201, Preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud (the fraud guidance), with different requirements for corporate and non-corporate Commonwealth entities.11 The Attorney-General’s Department is responsible for the Framework. On 1 February 2024 the Australian Government released the new Commonwealth Fraud Corruption and Control Framework which will come into effect on 1 July 2024.

1.8 The ATO is a non-corporate Commonwealth entity, and therefore must comply with the fraud rule and fraud policy. The Australian Government considers the fraud guidance as better practice, and entities are expected to follow the guidance where appropriate.12

1.9 Estimates of fraud losses against the Australian Government are based on responses by Commonwealth entities to the Australian Institute of Criminology’s (AIC) annual online questionnaire. The AIC estimates show the total amount lost to internal fraud has risen from $907,657 in 2016–17 to $3.4 million in 2020–21. The ATO reported to the AIC that the total amount lost to internal fraud each year from 2016–17 to 2021–22 is not able to be quantified. The AIC estimates show the total amount lost to external fraud against the Commonwealth for completed investigations has also risen from $91.9 million in 2016–17 to $198.4 million in 2021–22. For the ATO, the estimated total amount lost to external fraud for completed investigations has increased from $4.7 million in 2016–17 to $173.0 million in 2021–22 (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Total estimated amount lost to external fraud against the Australian Government and the ATO, completed investigations, 2016–17 to 2021–22

Source: Australian Institute of Criminology annual fraud census reports to Government, 2016–17 to 2021–22 and ANAO analysis of ATO documentation.

The Goods and Services Tax

1.10 The GST came into effect in Australia on 1 July 2000, and is an indirect broad-based consumption tax of 10 per cent, levied on most goods and services in Australia.13 The A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999 provides the administration framework for GST law.

1.11 The total net GST collected by the ATO has increased from $48.4 billion in 2012–13 to $81.4 billion in 2022–23, and the cost to administer the GST has decreased from $705.3 million in 2012–13 to $653.3 million in 2022–23. The ATO’s cost to administer the GST as a proportion of total net GST collected has decreased from 1.46 per cent in 2012–13 to 0.80 per cent in 2022–23 (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: The ATO’s cost to administer the GST as a proportion of total net GST collected, 2012–13 to 2022–23

Note: Net GST is gross GST payable, excluding input tax credits and including deferred GST payments on imports and GST collections by the Department of Home Affairs. Input tax credits are credits for any GST included in the price paid for goods and services a business or organisation registered for GST buys for their business. Deferred GST payments on imports is GST payable on taxable imports that can be paid via a monthly business activity statement rather than to the Department of Home Affairs at the time of importation.

Source: Australian Taxation Office, Taxation Statistics, GST Table 1 [Internet], available from https://data.gov.au/data/dataset/taxation-statistics-2019-20 [accessed 15 May 2023]. Data for 2021–22 sourced from the Australian Taxation Office Annual Report 2021–22, ATO, 2022, Table 3.1 and the Australian Taxation Office, GST administration annual performance report 2021–22, ATO, 2023. Data for 2022–23 sourced from the Australian Taxation Office, Annual Report 2022–23, ATO, 2023, Table 4.1 and ANAO analysis of ATO documentation.

1.12 Information about the ATO’s administration of the GST is at Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Information about the ATO’s administration of GST 2022–23

|

Element |

Contextual information |

|

Number of staff allocated to the administration of GST |

2,144.8 Full Time Equivalent (FTE), of which 1,229.1 FTE were forecast to undertake GST compliance (client engagement and compliance intelligence, and risk management activities). |

|

Total actual cost to administer the GST |

$653.3 million |

|

Geographical location of staff |

Staff are based across Australia, with Client Engagement Group staff predominately located in: Brisbane Central Business District (CBD); Dandenong Victoria; Perth; Sydney CBD; Canberra and Adelaide. |

Source: ANAO from ATO documentation.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.13 All Commonwealth entities are required to have fraud control arrangements in place in accordance with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework. Preventing and detecting GST fraud is integral for minimising loss of GST revenue available for the Commonwealth to make payments to the states and territories and maintaining public confidence in the tax system to support voluntary compliance.

1.14 This audit provides assurance to the Parliament that the ATO has effective management and oversight of fraud control arrangements for the administration of GST to protect the integrity of the tax system.

Previous scrutiny

1.15 Auditor-General Report No. 55 of 2002–03 Goods and Services Tax Fraud Prevention and Control observed that the ATO had systems and processes in place to prevent, detect, investigate and report GST fraud, with these activities undertaken and implemented across business lines. It made eight recommendations aimed at improving these systems and processes to strengthen its GST fraud control framework.14

1.16 The ATO agreed to all of the recommendations. Noting the significant timeframe (20 years) since this previous audit, along with subsequent changes to the Commonwealth fraud control requirements, this audit has not examined if the ATO implemented these recommendations. However, during the conduct of this audit, areas of the ATO’s GST fraud control framework identified as requiring strengthening were considered.

1.17 In 2018 the Inspector-General of Taxation undertook a review into the ATO’s fraud control management at the request of the Senate Economics References Committee, following events including those relating to Operation Elbrus and allegations of tax fraud. The review did not find evidence of systemic internal fraud or corruption and found that the ATO in general had sound systems in place to manage internal fraud, however there were areas requiring improvement. The Inspector-General of Taxation also made recommendations to improve processes aimed at the prevention of external fraud.15

1.18 In accordance with audit arrangements specified in the GST Administration Performance Agreement, the ANAO conducts an annual special purpose audit of GST costs and the systems of control of GST costs. Under Schedule C of the Agreement, the ANAO is required to provide all reports emanating from the special purpose audit directly to the ATO. The audit finding for the year ended 2023 was that ‘the ATO has suitably designed controls relating to the monitoring and reviewing of GST administration costs, as specified in Schedule B of the GST Administration Performance Agreement’.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s management and oversight of fraud control arrangements for the Goods and Services Tax.

1.20 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following criteria were adopted:

- Has the ATO implemented effective strategies to prevent GST fraud?

- Has the ATO effectively implemented strategies to detect and respond to GST fraud?

- Has the ATO implemented effective arrangements to oversee, monitor and report on fraud control arrangements for the administration of GST?

1.21 The audit focused on the ATO’s effectiveness of fraud control arrangements. The audit did not examine the effectiveness of the:

- ATO’s management and oversight for the risk of corruption;

- ATO’s management and oversight of conflict-of-interest arrangements; and

- the management and oversight of fraud control arrangements for the administration of GST by the Department of Home Affairs.

Audit methodology

1.22 The audit methodology involved:

- reviewing ATO records, including fraud risk assessments, fraud control plans, ATO committee papers and minutes, ATO reporting and internal briefings;

- reviewing the ATO’s procedures against the fraud guidance;

- meetings with ATO staff;

- analysis of relevant data provided by the ATO; and

- walkthroughs of ATO systems, including the Contemporising GST Risk Models project at the ATO office in Brisbane.

1.23 The audit was open to contributions from the public along with state and territory Treasury departments, as official members of the GST Administration Sub-Committee. The ANAO received and considered two submissions from the public and input from one state/territory.

1.24 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $519,371.

1.25 The team members for this audit were Ailsa McPherson, Kim Murray, Kayla Hurley, Hazel Ferguson, Dale Todd, Afreen Shaik and David Tellis.

2. Goods and Services Tax fraud prevention

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has implemented effective strategies to prevent Goods and Services Tax (GST) fraud.

Conclusion

The ATO has implemented partly effective strategies to prevent GST fraud.

The ATO has established an enterprise framework for fraud, but it is not fit for purpose and is not operating as intended.

The ATO assesses fraud risks and produces an annual fraud and corruption control plan. It is not evident how the ATO’s 2023 Fraud Control and Corruption Plan deals with identified external fraud risks as required under paragraph 10(b) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule.

The ATO has implemented mandatory training which includes fraud awareness content and monitors compliance with its requirement for ATO employees and contracted individuals to complete the mandatory training. The ATO raises awareness of GST fraud among external stakeholders through publishing information on its website and social media accounts.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at improving the ATO’s arrangements for assessing and managing its GST fraud risks.

The ANAO also suggested changes to the ATO’s mandatory training material.

2.1 Section 10 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) requires the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity to take all reasonable measures to prevent fraud relating to the entity, including by conducting fraud risk assessments regularly, developing and implementing a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks, and ensuring that officials of the entity are made aware of what constitutes fraud.16

2.2 Leading practice in fraud risk assessment requires accountable fraud risk owners to monitor and report on fraud risks and to ensure controls are developed and implemented in a timely manner, including controls that are the responsibility of other officials in different business areas.17 To assist entities prevent fraud, the fraud guidance encourages entities to provide information to external parties about their rights and obligations with regards to fraud.18

Has the ATO established a fit for purpose framework for GST fraud risk?

The ATO has established an enterprise framework for fraud, but it is not fit for purpose and is not operating as intended.

The ATO has established an external fraud risk owner and an internal fraud risk owner.

The Commissioner of Taxation has issued two Chief Executive Instructions (CEIs) setting out the requirements for managing fraud — one for external fraud and one for internal fraud. The CEIs do not reflect the roles and responsibilities in place in the ATO’s current structure. The ATO is in the process of clarifying roles and responsibilities for managing fraud risk and making the relevant changes to its CEIs.

The ATO’s conformance reporting process for external fraud is not fit for purpose. The ATO Audit and Risk Committee relies on this information to provide assurance to the Commissioner of Taxation as the ATO’s accountable authority. The ATO advised the ANAO in June 2023 that it is planning to redesign the external fraud conformance process to support the revised roles and responsibilities framework.

ATO fraud risk owners

2.3 The ATO does not have a single GST fraud risk owner and relies on each of its business lines to identify, assess and manage GST fraud risks within its area of responsibility. At the enterprise level, the ATO considers GST fraud risks as part of its external and internal fraud risk arrangements.

2.4 The ATO’s Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023 identifies the Deputy Commissioner (Senior Executive Service (SES) Band 2) of Integrated Compliance as the risk owner for the ATO’s external fraud risk and the Assistant Commissioner (SES Band 1) of Fraud Prevention and Internal Investigations as the risk owner for the ATO’s internal fraud risk. ATO fraud control and corruption plans have consistently identified these two positions as the risk owners of external fraud and internal fraud since 2019–20. In mid-2023, as part of a restructure of its business lines, the Deputy Commissioner of Integrated Compliance was appointed the Deputy Commissioner of Fraud and Criminal Behaviours and retained responsibility as the risk owner for the ATO’s external fraud risk.19

2.5 Under the ATO’s Risk Management Framework, as set out in the accountable authority’s Chief Executive Instruction (CEI)20 on risk management, ATO risk owners:

- are personally accountable for identified risks;

- are responsible for providing direction on relevant risk management activities within their area of responsibility and across business lines where appropriate; and

- oversee the status of risks, controls, and treatment strategies.

ATO Chief Executive Instructions on fraud

2.6 The Commissioner of Taxation, as the ATO’s accountable authority, has issued two CEIs that set out the requirements for all ATO employees and contracted individuals (subject to the terms of the individual’s contract) for preventing, detecting, and dealing with fraud.21 The CEIs also identify roles within the ATO that have specific responsibilities for assessing fraud risk and managing fraud in the ATO. One CEI covers external fraud (fraud committed by those outside of the ATO) and the other covers internal fraud (fraud committed by ATO employees or contracted individuals).

2.7 The ATO’s external fraud CEI requires ‘Senior Responsible Officers’ (senior responsible officers) to ‘actively manage external fraud by conducting and reviewing risk assessments regularly to ensure appropriate external fraud risk tolerances, treatments and controls are in place and documented for their program’. The ATO advised the ANAO in July 2023 that the CEI refers to a position title that does not exist within the ATO but the function is generally carried out by Executive Level or SES personnel responsible for managing a program of work.

2.8 The external fraud CEI further requires ‘National Program Managers’ to ‘manage external fraud risk within their business line’ and ‘provide assurance on the management of external fraud risk within their business line to the external fraud risk owner via the external fraud conformance process’ (discussed in paragraphs 2.11 to 2.17). The ATO advised the ANAO in July 2023 that the term ‘National Program Manager’ (national program manager) is no longer used in the ATO but had been used to describe those members of the SES that are responsible for large programs of work and collectively it refers to the Deputy Commissioner (SES Band 2) positions within the ATO.

2.9 The ATO’s internal fraud CEI does not mention senior responsible officers and does not identify who is responsible for conducting and reviewing internal fraud risk assessments. The ATO advised the ANAO in October 2023 that the ATO’s Assistant Commissioner of Fraud Prevention and Internal Investigations, in their capacity as the risk owner for the ATO’s internal fraud risk (see paragraph 2.4) is responsible for conducting and reviewing internal fraud risk assessments regularly. Similar to the external fraud CEI, the internal fraud CEI assigns responsibility for managing internal fraud and corruption risks within business lines to national program managers. National program managers are also required to ‘actively support’ internal fraud risk assessment activity within their business line. As noted in paragraph 2.8, the term national program manager is an outdated term for what are now Deputy Commissioner (SES Band 2) positions within the ATO.

2.10 The ATO is reviewing the roles and responsibilities including those of senior responsible officers and what were formerly known as national program managers. The CEIs will then be updated accordingly. In November 2023, the ATO updated its internal fraud CEI. The updated CEI refers to Deputy Commissioners instead of national program managers. In July 2023, the ATO advised the ANAO that the changes to the external fraud CEI would occur in three phases with phase one (‘minor changes’) being a revised CEI issued ‘within the next few months’, phase 2 changes by June 2024 and phase three post July 2024. The phase two changes include clarifying the roles and responsibilities of senior responsible officers which ATO documents state ‘will involve identifying and confirming SROs [senior responsible officers] with existing responsibilities for key controls and treatments.’ Phase three changes are undefined but the ATO advised the ANAO in July 2023 that they are in ‘recognition that a further revision may be required’.

The ATO’s external fraud conformance process

2.11 The ATO’s external fraud conformance reporting processes is the basis for the ATO’s external fraud risk owner’s reporting to the ATO Audit and Risk Committee (ARC) on the effectiveness of the ATO’s management of its external fraud risks.22 It is the mechanism for providing the risk owner with an ATO wide view of the entity’s external fraud risk, the administration of which is dispersed throughout various ATO business lines.

2.12 Each quarter, the ATO’s Integrated Compliance business line requests selected ATO business lines to complete a conformance questionnaire to self-assess whether the business line has conformed with the ATO’s obligations for managing external fraud, including the requirements of the external fraud CEI, during the relevant quarter. The ATO does not have a systematic process for selecting business lines each quarter to ensure timely and regular coverage of all ATO business lines, but informed the ANAO in August 2023 it is developing one. The ATO described its process of selecting business lines to the ANAO as follows:

The Fraud and Criminal Behaviours (FCB) conformance team maintains a list of previous conformance reviews for the prior three years and selects business lines for each quarter based on an area’s external fraud risk exposure and period of time since the last conformance review. To improve selection decisions, the FCB conformance team are in the process of preparing a forward plan for the 2023–24 year.

2.13 The business lines’ self-assessments then form the basis for quarterly reports of the ATO’s conformance with its external fraud obligations to the external fraud risk owner which in turn underpins the risk owner’s reporting to the ARC.

2.14 The ANAO examined the ATO’s external fraud conformance reporting records for the quarters from June 2021 to June 2023 inclusive (nine quarters). Quarterly conformance reporting during this period was incomplete, not timely, and did not provide adequate assurance of the ATO’s compliance with its external fraud obligations.

- The quarterly statements of conformance to the external fraud risk owner are based on completed questionnaires requested from a selection of ATO business lines for that quarter. Coverage of the ATO’s business lines during the June 2021 to June 2023 period examined by the ANAO was limited to a total of ten23 of the ATO’s business lines, the number of which has changed from 24 in late 2022/early 2023, to 32 as at mid-2023.

- The highest coverage of the ATO’s business lines in the nine reporting quarters from June 2021 to June 2023 (inclusive) was in the June 2021 and September 2021 quarters where three of the ATO’s 24 business lines were selected for review in each quarter.

- The ATO does not have a systematic process for selecting business lines each quarter to ensure timely and regular coverage of all ATO business lines.

- The statement of conformance for the March 2022, June 2022 and March 2023 quarters do not identify which business lines responded to the questionnaire.

2.15 The ATO further advised the ANAO in July 2023 that each business line is examined, approximately, on an annual basis. However, the ATO’s records of the quarterly external fraud conformance reporting processes shows that the ATO has not:

- examined each business line annually during the nine reporting periods reviewed as part of this audit (June 2021 to June 2023 quarters);

- examined every business line in the two year period reviewed as part of this audit (June 2021 to June 2023); and

- examined any business line more than once during this time (June 2021 to June 2023), with one exception (the individuals and intermediaries business line).

2.16 An example of the realisation of the risk associated with the external fraud conformance process being incomplete and not timely occurred in June 2023 when the ATO’s Small Business line reported in its quarterly self-assessment questionnaire that it had not documented an assessment of its external fraud risks, including GST fraud risks, since April 2019. The ARC was advised of this non-conformance with the ATO’s obligations at its 31 August 2023 meeting. The ATO’s Small Business line has further advised the ARC that it intends to complete a fraud risk assessment by December 2023, advising the ‘consequence of not addressing this matter in a timely manner may bring adverse findings and criticism from targeted internal or external reviews’.

2.17 In its March 2023 and June 2023 quarter conformance reports, the ATO assessed the conformance of its senior responsible officers with the external fraud CEI as ‘partially effective’, concluding that:

Whilst accountability of external fraud rests with [Deputy Commissioner] DC Fraud and Criminal Behaviours, and is partially effective, reviews have revealed the role of Senior Responsible Officers across ATO business areas in fraud prevention, detection and treatment in context of their business areas are not clear and could lead to gaps in actively managing external fraud (top down and bottom up).

In response, the ATO is developing a new Governance framework including clarifying external fraud roles and responsibilities. This Governance framework is being considered for endorsement at senior levels as part of internal conversations on how external fraud is better managed across the ATO (particularly as a shared risk).

The External Fraud Roles and Responsibilities Framework will be agnostic of tax product and client experience.

The External Fraud conformance process will be redesigned to support the revised roles and responsibilities framework.

The ATO’s internal fraud conformance process

2.18 The ATO’s internal fraud risk owner (Assistant Commissioner (SES Band 1) of Fraud Prevention and Internal Investigations) reports the level of conformance with the ATO’s obligations for managing internal fraud to the ARC quarterly. In October 2023, the ATO advised the ANAO that the quarterly conformance process for internal fraud changed to an annual process from February 2023 consistent with the ATO’s requirement for annual conformance reporting where the risk consequence in the conformance report is assessed as ‘major’ and its likelihood ‘rare’.

Recommendation no.1

2.19 The Australian Taxation Office, as a matter of priority, should finalise its work on:

- clarifying and documenting the roles and responsibilities for fraud prevention, detection, and treatment;

- redesigning the external fraud conformance process to support the revised roles and responsibilities; and

- making the necessary changes to the external fraud and internal fraud Chief Executive Instructions.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

2.20 The ATO agrees to prioritise and finalise work on roles and responsibilities for fraud prevention, detection and treatment and reflect this in a redesign of the external fraud conformance process and Chief Executive Instructions for external and internal fraud.

Has the ATO assessed GST fraud risks and established and implemented an appropriate fraud control plan?

The ATO assesses fraud risks and produces an annual fraud and corruption control plan.

It is not evident how the ATO’s 2023 Fraud Control and Corruption Plan deals with identified external fraud risks (including GST fraud risks) as required under paragraph 10(b) of the Public Government, Performance and Accountability Rule, or whether the ATO’s controls and strategies for external fraud are commensurate with assessed fraud risks as suggested in the fraud guidance.

The ATO has completed internal fraud and corruption risk assessments, largely within the two-year timeframe suggested in the Commonwealth fraud guidance. The ATO has not completed external fraud risk assessments within the two-year timeframe required by its external fraud governance framework. No ATO business line has completed a business line level fraud risk assessment relevant to GST fraud since 2020. As of June 2023, the ATO was working towards clarifying the roles and responsibilities for assessing and managing GST fraud risks.

ATO GST fraud risk assessments

2.21 Part five of the fraud guidance encourages entities to conduct fraud risk assessments at least every two years and further suggests that ‘entities responsible for activities with high fraud risk may wish to assess fraud risk more frequently’.24 The Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre’s Fraud Risk Assessment Leading Practice Guide states ‘risk assessments provide assurance that public funds are being managed in an accountable manner and that the potential harms of fraud are being actively mitigated’.25

2.22 The GST is administered by ATO business lines that are structured around taxpayer types.26 The ATO does not develop GST specific fraud risk assessments. Each of its business lines is required to identify, assess and manage GST fraud risks within its area of responsibility. At the enterprise level, the ATO considers GST fraud risks as part of its external and internal fraud risk assessments. The ATO’s framework for assessing and managing external and internal fraud risk is examined in paragraphs 2.3 to 2.20.

2.23 In November 2020, the Assistant Commissioner of the GST Program established the GST Program Risk Assurance project to increase and maintain confidence that compliance risks to the GST system are being managed efficiently and effectively. In a presentation to the May 2021 meeting of the GST Integrated Risk Forum27 the project team (comprising ATO officials at the EL2, EL1 and APS 6 levels) reported a ‘lack of evidence of current key risk artefacts28 required to demonstrate that GST compliance risks are being managed efficiently and effectively across the ATO’. Further, the ATO’s Chief Internal Auditor’s report of their review of Operation Protego29 (April 2023) states that the ATO’s analysis and assessment of its GST fraud risks is ‘not holistic or based on robust evidence’. As of June 2023, the ATO was working towards clarifying the roles and responsibilities for assessing and managing GST fraud risks. This work was ongoing as of 2 November 2023.

ATO business line risk assessments relevant to GST fraud risk

2.24 Between 2017 and 2020 three ATO business lines responsible for managing the ATO’s engagement with different groups of taxpayers (Small Business, Privately Owned and Wealthy Groups, and Public and Multinational Businesses30) documented a total of eight risk assessments incorporating GST fraud risks relevant to their business line, three of which are marked as drafts. Of the remaining five, four contain no indication that they were approved, and one states that it was ‘endorsed/approved with qualification’ by the Risk Manager (the qualification is not specified). The authority and utility of these risk assessments is unclear given they are either in draft form or not approved by the risk owners.

2.25 No ATO business line has completed a business line level fraud risk assessment relevant to GST fraud since 2020. ATO documents indicate that the ATO is planning to complete three separate risk assessments to assess and determine the risk ratings and tolerances associated with GST refund integrity, Small Business GST, and GST registration. As of October 2023, the ATO had started work on the risk assessment for GST refund integrity — defined by the ATO as ‘incorrect GST refunds occurring because of failure to correctly report GST due to errors, deliberate misreporting of GST on sales or purchases, and/or incorrect GST registrations by those not entitled to be registered’.

ATO external fraud risk assessments

2.26 At the enterprise level, the ATO considers the risk of GST fraud perpetrated by individuals outside of the ATO as part of its external fraud risk assessments.31 The ATO’s External Fraud Governance Framework requires external fraud risk assessments to be completed every two years.

2.27 Since 2017, the ATO has finalised three external fraud risk assessments — in November 2018, in May 2021, and in October 202332 (see Table 2.1). Neither of the two most recent risk assessments were completed within the two year timeframe required by the ATO’s External Fraud Governance Framework. Table 2.1 sets out the ATO’s assessment of its external fraud risk as documented in its primary risk assessment artefacts since 2017.

Table 2.1: ATO’s assessment of its external fraud risk since 2017

|

External fraud risk assessment |

Risk tolerance levela |

Risk ratingb |

Assessment of controls |

Likelihood of risk occurring |

Consequence of risk occurring |

|

2023 External Fraud Risk Assessment and Treatment Plan (finalised October 2023) |

High |

Severe (risk rating is ‘above’ tolerance) |

Partially effective |

Even chance |

Extreme |

|

2020 (finalised May 2021) |

Low |

Low (risk rating is within tolerance)c |

Partially effective |

Rare |

Medium |

|

External Fraud Risk Review as at December 2019 (finalised March 2020) |

The risk review did not change any ratings and kept the risk level at ‘severe’. The document states that that ‘in order to ensure our risk position is current given the rapidly changing environment undertake a program to review the risk on a monthly basis for the remainder of this year commencing 30 May 2020’. The ATO advised the ANAO it did not proceed with this plan due to other priorities (supporting the administration of the COVID-19 stimulus program). |

||||

|

2018 (finalised November 2018) |

Significant |

Severe (risk rating is out of tolerance) |

Partially effective |

Almost certain |

Very high |

Note a: Risk tolerance levels operationalise an entity’s risk appetite by specifying the levels of risk taking that are acceptable. Source: Commonwealth Risk Management Policy, last updated 29 November 2022, available from https://www.finance.gov.au/government/comcover/risk-services/management/commonwealth-risk-management-policy. The ATO’s Risk Tolerance Guide states that risk tolerance is ‘the level of risk which is acceptable and where no further treatment action is required. In most cases, a risk that is not within tolerance must undergo further treatment action or a decision to accept the risk level would be documented’. Within the ATO, Risk Owners are responsible for setting the risk tolerance for the risk they own.

Note b: The ATO’s risk matrix comprises six risk levels — low, moderate, significant, high, severe, and catastrophic (see Appendix 4).

Note c: ATO documents indicate that it has been unable to locate ‘detailed written explanation for the change in risk level’ from ‘severe’ in the 2018 risk assessment to ‘low’ in the 2020 risk assessment.

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documents.

The 2020 external fraud risk assessment (ATO’s extant fraud risk assessment until October 2023)

2.28 The ATO’s 2020 external fraud risk assessment was approved by the Deputy Commissioner of Integrated Compliance in May 2021 and was extant until October 2023. The ATO described its method for compiling its 2020 external fraud risk assessment as follows:

The 2020 Risk Assessment commenced in November 2020. The control framework was considered through a series of workshops with key stakeholders and the assessment of key programs including the Integrated Compliance managed, high-risk population programs following the ATO Enterprise Risk Management Framework and the AGD [Attorney-General’s Department] Control Assessment Guidelines. The final control and risk assessments were agreed to with the participants from key programs across the Compliance Engagement Group. These products were aggregated into the final assessment.

The assessment was approved 26 May 2021.

2.29 In this assessment, the ATO assigned an overall risk rating of ‘low’ to its external fraud risk and assessed the risk as being within tolerance. In consequence, the risk assessment states that the management responsibility for the risk of external fraud was assigned to the APS Executive Level 2, in accordance with the ATO’s scale of management actions.

2.30 As Table 2.1 shows, the ATO’s assessment of its risk of external fraud changed from ‘severe’ in 2018 to ‘low’ in 2020, and is rated as ‘severe’ in the ATO’s 2023 external fraud risk assessment. ATO documents state that the ATO has been unable to locate any ‘detailed written explanation for the change in risk level’ between the 2018 and 2020 external fraud risk assessments. The ATO described its rationale for this downgrading of its external fraud risk rating to the ANAO as follows:

The 2020 assessment (formally endorsed in 2021…) focussed on the effectiveness of the ATO’s existing controls. It also recognised the approach taken in the ATO’s rapid implementation of the economic stimulus measures to ensure the controls were as robust as could be and resulting occurrence of little fraud and immaterial revenue loss in relation to the total payments made. The likelihood of the controls failing was assessed as rare, supported with system-based analysis demonstrating the level of robustness of the holistic approach the ATO takes. The consequence should the controls fail was assessed as medium, resulting in the risk being assessed as within tolerance at low.

The data in 2020 did not indicate systemic fraud and the environment at the time had not changed.

2.31 The 2020 external fraud risk assessment also includes the ATO’s assessment of the effectiveness of its controls33 on 13 external fraud risks, which the ATO has assessed as being ‘generally reliable’ and ‘partially effective’ overall. The 2020 external fraud risk assessment also lists 13 preventative, detective and correction controls that require improvement to raise the effectiveness of the ATO’s control assessment above ‘partially effective’. The controls are not attributed in the document to the 13 external fraud risks. The ATO’s external fraud risk assessment is not underpinned by a documented record (such as a risk register) of specific risks and corresponding controls for each of the broad 13 external fraud risks identified in the risk assessment document.

The 2023 external fraud risk assessment

2.32 In May 2023, the ATO’s Integrity Steering Committee34 considered an overview of the ATO’s draft 2023 external fraud risk assessment and endorsed the proposed risk rating of ‘severe’ with the risk rating being ‘out of tolerance’. An action item from that meeting was for the ATO to finalise the 2023 external fraud risk assessment by 30 June 2023 for consideration by the committee at its next meeting on 1 August 2023. The ATO Integrity Steering Committee endorsed the 2023 External Fraud Risk Assessment and Treatment Plan, dated 28 September 2023 on 5 October 2023.

2.33 As Table 2.1 shows the ATO’s assessment of its risk of external fraud changed from ‘low’ in 2020 to ‘severe’ in 2023 and that the ATO considers this to be ‘above tolerance’. In consequence, the risk assessment states the required risk manager level for the ATO’s external fraud risk is SES Band 3. In its 2023 external fraud risk assessment document the ATO has:

- identified 10 external fraud sub-risks (these are different risks to the 13 risks listed in the 2020 external fraud risk assessment);

- assessed its controls35 against the 10 sub-risks as being ‘partially effective’ overall;

- identified the requirements of section 10 of the PGPA Rule as further controls and assessed these controls as ‘partially effective’;

- determined that risk treatment is required to bring the external fraud risk within tolerance;

- determined that the required risk treatment is to add or modify controls (to reduce the likelihood or consequence of the risks) and bring the external fraud risk within tolerance; and

- stated that the risk treatment plan is ‘pending’.

2.34 In June 2023, the ATO requested ministerial approval to seek additional funding for its counter fraud activities to bring its fraud risk back into tolerance. The ATO advised the Minister for Financial Services that this was the first time this risk has been out of tolerance. Table 2.1 shows the ATO had assessed the fraud risk as being out of tolerance from 2018 until it reassessed the risk in 2020 as being within tolerance.

ATO’s internal fraud and corruption risk assessments

2.35 At the enterprise level, the ATO considers the risk of GST fraud perpetrated by individuals inside of the ATO as part of its broader internal fraud and corruption risk assessments.36 Since 2017, the ATO has completed five enterprise-wide internal fraud and corruption risk assessments, largely within the two-year timeframe suggested in the Commonwealth fraud guidance. Table 2.2 sets out the ATO’s assessment of its internal fraud risk as documented in its primary risk assessment artefacts since 2017.

Table 2.2: ATO internal fraud and corruption risk assessment ratings since 2017

|

Internal fraud and corruption risk assessment |

Risk tolerance levela |

Risk ratingb |

Assessment of controls |

Likelihood of risk occurring |

Consequence of risk occurring |

|

2023 (finalised Jun 2023) |

Significant |

Significant (risk rating level is within tolerance) |

Effective |

Even chance |

Major |

|

2021 (finalised Mar 2021) |

Significant |

Significant (risk rating level is within tolerance) |

Effective |

Even chance |

Medium |

|

2020 (specific to COVID-19) (finalised July 2020) |

Significant |

Significant (risk rating level is within tolerance) |

Partially effective |

Even chance |

Medium |

|

2019 (finalised Aug 2019) |

Significant |

Significant (risk rating level is within tolerance) |

Effective |

Even chance |

Medium |

|

2018 (finalised Nov 2018) |

Significant |

Significant (risk rating level is within tolerance) |

Effective |

Even chance |

Medium |

Note a: Risk tolerance levels operationalise an entity’s risk appetite by specifying the levels of risk taking that are acceptable. Source: Commonwealth Risk Management Policy, last updated 29 November 2022, available from https://www.finance.gov.au/government/comcover/risk-services/management/commonwealth-risk-management-policy. The ATO’s Risk Tolerance Guide states that risk tolerance is ‘the level of risk which is acceptable and where no further treatment action is required. In most cases, a risk that is not within tolerance must undergo further treatment action or a decision to accept the risk level would be documented.’ Within the ATO, Risk Owners are responsible for setting the risk tolerance for the risk they own.

Note b: The ATO’s risk matrix comprises six risk levels — low, moderate, significant, high, severe, and catastrophic (see Appendix 4).

Source: ANAO analysis from ATO documents.

Recommendation no.2

2.36 The Australian Taxation Office should conduct and document assessments of its GST fraud risks regularly and ensure that it has a contemporary and holistic view of its GST fraud risks.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

2.37 The ATO agrees to regularly conduct and document assessments of GST fraud risks and ensure it has a contemporary and holistic view of GST fraud risks.

Fraud Control and Corruption Plan 2023

2.38 Each year in the ATO’s annual report from 2017–18 (the timeframe covered in the scope of this performance audit), the Commissioner of Taxation, as the accountable authority for the ATO, certifies that the ATO has prepared fraud risk assessments and fraud control plans as required by section 10 of the PGPA Rule. The ATO has developed an enterprise-wide fraud and corruption control plan for each financial year from 2017–18.

2.39 The ANAO examined the ATO’s Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023 (the current plan at the time of this performance audit) to determine the extent to which the plan meets the requirements of paragraph 10(b) of the PGPA Rule and part six of the fraud guidance with regards to the plan emphasising prevention, being available to all officials, and dealing with identified fraud risks.

2.40 Part six of the fraud guidance states that it is important for fraud control plans to emphasise prevention and encourages entities to make their fraud control plans available and accessible to all officials.37 The ATO’s Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023 is available on the ATO’s external website38 and intranet. The plan identifies prevention as one of three elements of the ATO’s fraud and corruption control framework (prevention, detection, response). The plan also states that the ‘ATO promotes prevention of fraud and corruption risks’, and includes the following statements on the ATO’s view of fraud prevention:

- Prevention strategies are the first line of defence, and these include proactive measures designed to help reduce the risk of fraud and corruption.

- Preventing fraud minimises the need for the ATO to detect and respond to fraud.

2.41 The fraud guidance further suggests seven elements that entities may include in their fraud control plans, none of which are mandatory.39 The ATO’s Fraud Control and Corruption Plan 2023 includes these seven elements.

2.42 Paragraph 10(b) of the PGPA Rule requires the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity to take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and deal with fraud relating to the entity, including by developing and implementing a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks as soon as practicable after conducting a risk assessment.40 Part six of the fraud guidance states that controls and strategies outlined in fraud control plans are ideally commensurate with assessed fraud risks.41

2.43 At the time that the ATO finalised its Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023 in early 202342, the ATO’s most recent external fraud risk assessment was a 2020 external fraud risk assessment that was approved in May 2021.43 The ANAO examined the alignment of the external fraud risks identified in the ATO’s Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023 with those in the ATO’s 2020 external fraud risk assessment.

2.44 The Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023 lists six ‘priority behavioural risks’ for external fraud:

- identity crime enabled fraud;

- refund fraud;

- serious and organised crime in the tax and super systems;

- offshore tax evasion;

- illegal phoenix; and

- black economy.44

2.45 The plan also lists examples of the ATO’s fraud and corruption prevention, detection and response activities. The plan does not attribute these activities to the six behavioural risks. Four of these behavioural risks (identity crime enabled fraud, serious and organised crime, offshore tax evasion, and illegal phoenix) are common to the list of 13 external fraud risks identified in the 2020 external fraud risk assessment (see paragraph 2.31). It is not evident how the plan deals with the ATO’s identified external fraud risks, as required under paragraph 10(b) of the PGPA Rule, or whether the ATO’s controls and strategies for external fraud are commensurate with assessed fraud risks as suggested in the fraud guidance because the identified risks in the two documents cannot be reconciled.

2.46 In June 2023 the ATO informed the ANAO that:

- its publicly available fraud and corruption control plans are framework documents rather than detailed plans as they necessarily only include the ATO’s high level assessment of controls for addressing fraud risks and not the details of specific fraud risks and associated controls;

- the ATO does not prepare a more detailed non-public version of its annual fraud control and corruption plan; and

- each ATO business line maintains its own risk register and risk treatment plans.

2.47 As noted in paragraph 2.23, ATO internal reviews of its management of GST risks have identified gaps in the ATO’s records of current key risk artefacts (including risk assessments and treatment plans) and the ATO’s work on clarifying the roles and responsibilities for assessing and managing GST fraud risks is ongoing.

2.48 The ATO’s Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023 lists three areas of ‘priority internal fraud risk’ as:

- corruption and insider threat;

- working arrangements in a hybrid work environment; and

- spending of public monies.

2.49 As noted in paragraph 2.45, the plan also lists examples of the ATO’s fraud and corruption prevention, detection and response activities. The plan does not attribute these activities to the three areas of ‘priority internal fraud risk’ listed in the plan.

2.50 The ATO’s most recent enterprise-wide internal fraud and corruption risk assessment is dated 30 June 2023. This risk assessment lists five ‘risk drivers’: financial advantage, disclosure of information, poor implementation of a new program, restructure of a process or function, and conflicts of interest. The risk assessment also includes the ATO’s assessment of the effectiveness of 10 controls that the ATO relies on to manage its single identified risk (internal fraud and corruption) and rates all 10 controls as being ‘effective’.

Recommendation no.3

2.51 The Australian Taxation Office ensures that its fraud control and corruption plans are based on identified fraud risks that are documented in risk assessments.

Australian Taxation Office response: Agreed.

2.52 The ATO agrees to ensure fraud control and corruption plans are based on identified fraud risks documented in risk assessments.

Changes to the ATO’s GST risk assessment strategies after the 2022 GST fraud events

2.53 Part five of the fraud guidance states that ‘it is important for risk assessment strategies to be reviewed and refined on an ongoing basis in light of experience with continuing or emerging fraud vulnerabilities’.45 In 2023 the ATO initiated activities intended to address the shortcomings in its GST fraud risk management that the Operation Protego GST fraud event46 exposed. These include the following.

- The ATO has added ‘registration’ and ‘external fraud’ as new enterprise risks47 in its corporate plan for 2023–24.

- In April 2023, the ATO’s Chief Internal Auditor completed an audit insights paper which includes observations and suggestions that the paper states are considered ‘critical to embedding GST fraud risk management as an enduring capability’.48 The ATO Audit and Risk Committee considered the paper at its June 2023 meeting. The minutes from that meeting state that the committee observed the ‘ambiguity around accountability for each of the suggestions’.

Has the ATO implemented appropriate fraud awareness and training for officials to prevent and detect GST fraud?

The ATO has documented a clear and widely available definition of what constitutes fraud in its Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023. The ATO’s external and internal fraud CEIs require ATO employees and contracted individuals to complete ‘mandatory training’, which includes three courses with fraud awareness content. The ATO monitors compliance with its requirement that staff complete mandatory training and reports completion rates for these three courses to the ATO Audit and Risk Committee.

The ATO’s definition of GST fraud

2.54 To assist with raising awareness of what constitutes fraud, part seven of the fraud guidance encourages entities to have a widely distributed fraud strategy statement. Guidance published by the Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre within the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) explains that a fraud strategy statement helps people understand what fraud is, an entity’s views about fraud, and what staff and contractors should do if they suspect fraud.49 The guidance states that the fraud strategy statement can be part of an entity’s fraud control plan.

2.55 The ATO’s Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023 quotes the definition of fraud from the Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy. The plan provides further guidance on the nature of fraud and includes examples of what internal and external fraud might look like in the context of the ATO’s activities, including an example of GST fraud. The plan is publicly available on the ATO’s external website.

Fraud awareness training in the ATO

2.56 Part seven of the fraud guidance encourages entities to have all officials take into account the need to prevent and detect fraud as part of their normal responsibilities. The guidance suggests entities establish fraud awareness and integrity training in all induction programs and a rolling program of regular fraud awareness and prevention training for all officials.50

Mandatory training

2.57 The ATO’s Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023 identifies mandatory online51 training for ATO staff as one element of the ATO’s fraud and corruption prevention activity. The ATO’s external and internal fraud CEIs require ATO employees and contracted individuals to complete ‘mandatory training’, which includes three courses first introduced during the June 2020 quarter52 that include content covering fraud awareness, ethics, privacy and the APS Code of Conduct, as suggested by the fraud guidance.

- ‘Working in the ATO’ (mandatory for all new staff).

- ‘Safe, secure and inclusive’ (mandatory for all new staff and as an annual refresher).

- ‘Managing safety and integrity’ (which is mandatory for all new managers53 and all existing managers as an annual refresher).54

2.58 The ANAO found that that the ‘Managing safety and integrity’ course:

- does not refer to the current version of the ATO’s external fraud CEI; and

- includes a scenario titled ‘reporting external fraud’ that is about document security when working from home and not about reporting external fraud.

2.59 The ATO advised the ANAO that certain cohorts of ATO staff are not granted access to ATO systems as their work requirements do not include the requirement for ATO system access to complete work tasks (for example some contractors or labour hire personnel). These cohorts of ATO staff are required to complete the ‘Working in the ATO’ course through a commercially available mobile application (EdApp) which can be downloaded to an individual’s personal device.

2.60 The ANAO reviewed the ‘Working in the ATO’ training available through EdApp and found that the fraud awareness content is materially the same as the ATO’s intranet based version of this ATO training. The ANAO found that the EdApp training refers the trainee to documents that the trainee cannot access without access to ATO systems (for example, the ATO external fraud CEI). If the information in such documents is important, then the content should be available to the trainee within EdApp, or through alternative means.

|

Opportunity for improvement |

|

2.61 The Australian Taxation Office could improve the utility of its training material by:

|

Monitoring completion of mandatory training

2.62 The ATO monitors compliance with its requirement that staff complete mandatory training and issues reminder emails to staff and their manager if training is not completed within the expected timeframes. Where staff have not completed the required mandatory training, the ATO may remove an individual’s access to some systems.

2.63 ATO managers are responsible for ensuring that their team members are up to date with their mandatory training. Completion rates for mandatory training courses are reported to the ATO Audit and Risk Committee quarterly. In November 2023 the ATO reported completion rates of 90 per cent or more for each of the three mandatory training courses as at September 2023.

Has the ATO appropriately raised GST fraud awareness among external stakeholders?

The ATO has established external communications products that raise GST fraud awareness among external stakeholders. Information from these products is contained on the ATO’s website and social media posts.

2.64 The ATO’s Fraud and Corruption Control Plan 2023 identifies the ATO’s external communications program as one of its fraud and corruption prevention activities.

2.65 The ATO has a ‘the-fight-against-tax-crime’ website which includes:

- an explanation of what tax crime is and what the ATO is doing to prevent and respond to tax crime;

- a statement that the ATO takes all forms of tax crime seriously and will take firm action, including seizing the profits, of those participating in tax crime;

- warnings about becoming involved in tax fraud (including GST fraud);

- ATO media releases about GST fraud cases and prosecutions; and

- outcomes of successful prosecutions for tax crime, including case studies of prosecutions for GST fraud.

2.66 The ATO provides information for businesses about what they need to do to meet their Business Activity Statement obligations on the ATO website and social media posts.

2.67 The ATO also posts information on social media (on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn) and conducts advertising campaigns (on social media and internet search engines) with warnings about GST fraud and the risks and consequences of becoming involved in GST fraud. The ATO uses emails and its website to communicate with applicants for new Australian Business Numbers (ABN) to inform them about eligibility for an ABN and warning against becoming involved in GST fraud.

2.68 The ATO raises awareness of GST fraud among tax agents through, for example:

3. Goods and Services Tax fraud detection, investigation and response

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has effectively implemented processes to detect and deal with suspected Goods and Services Tax (GST) fraud.

Conclusion

The ATO’s processes to detect and deal with suspected GST fraud are largely effective.

The ATO has implemented effective processes to confidentially report allegations of suspected fraud. The ATO has procedures to assess and refer ‘tip offs’ of external fraud to the relevant business line for further action, and to assess and investigate allegations of suspected internal fraud.

The ATO has methods to detect potential GST fraud.

The ATO has processes for investigating suspected fraud and taking action but does not have a procedure to respond to a large-scale fraud event.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at expanding the ATO’s integrity incident response framework to include large-scale fraud events.

3.1 Section 10 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) requires the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity to take all reasonable measures to detect and deal with fraud.58 In order to detect and then investigate and respond to fraud, entities must take active steps to find fraud when it occurs.

Does the ATO have appropriate processes for suspected GST fraud to be confidentially reported?

The ATO has processes for ATO officials and members of the public to confidentially report allegations of suspected GST fraud. The ATO has documented instructions and procedures for ATO officials to assess reports of suspected external fraud (including suspected GST fraud) and to refer these reports to the relevant business line for further investigation.

ATO processes for reporting suspected external fraud (including GST fraud)

3.2 Paragraph 10(d) of the PGPA Rule requires entities to have ‘a process for officials of the entity and other persons to report suspected fraud confidentially’.59 The fraud guidance notes that reporting suspected fraud is a common means of detection, and therefore it is important for entities to appropriately publicise fraud reporting mechanisms. Under the fraud guidance entities should encourage and support reporting of suspected fraud through proper channels, and this can include measures to protect those making such reports from adverse consequences.60

3.3 The ATO has channels for suspected fraud to be reported by the general public.61 These channels are advertised on the ATO’s website, including:

- tip-off hotline;

- tip-off form (the ATO tip-off form is also accessible through the ATO mobile app); and

- postal address.

3.4 From 1 July 2019, amendments to the Taxation Administration Act 1953 created a whistleblower protection regime for the protection of individuals who report breaches of the tax laws or misconduct. The ATO advertises these arrangements on the ATO website.62