Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Australian Public Service Commission’s Administration of Integrity Functions

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- All members of the Australian Public Service (APS) are subject to integrity and ethical obligations established by the Parliament through legislation.

- This audit provides independent assurance and reporting to Parliament on the Australian Public Service Commission’s (APSC’s) administration of statutory functions relating to upholding high standards of integrity and ethical conduct in the APS.

- The audit review period was July 2022 to December 2023.

Key facts

- The Australian Public Service Commissioner and APS employees assisting the Commissioner together constitute a Statutory Agency under the Public Service Act 1999, known as the APSC.

- The Parliament has provided that one of the three broad functions of the Commissioner under the Public Service Act 1999 is ‘to uphold high standards of integrity and conduct in the APS’.

What did we find?

- The APSC was partly effective in its administration of statutory functions relating to upholding high standards of integrity and ethical conduct in the APS during the audit review period. The APSC’s approach was largely activity-driven and it did not have relevant strategies, linked to measurable outcomes, to guide its efforts. As a consequence, the APSC could not demonstrate or provide assurance on whether its activities relating to integrity functions were well directed or fully effective. In the context of an operating environment focused on perceived shortcomings in APS integrity, the APSC was in the process of developing a more strategic approach.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made four recommendations to the APSC relating to strategy development, evaluation and record keeping.

- The APSC agreed to all four recommendations.

177442

APS headcount at 31 December 2023.

38

suspected Code of Conduct breaches by SES in 2022 and 2023, as reported to the APSC.

684

enquiries received by the APSC’s Ethics Advisory Service from July 2022 to December 2023.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Public Service (APS) is established by the Public Service Act 1999 (PS Act). It is one part of the wider Commonwealth public sector and consists of agency heads and APS employees engaged under the PS Act.1 The APS operates largely under principles-based frameworks, including that established by the PS Act, which impose high expectations regarding integrity.

2. Members of the APS are subject to integrity obligations specified in the PS Act, including the APS Values2 and APS Code of Conduct.3 At 5 April 2024 the PS Act specified five APS Values — committed to service, ethical, respectful, accountable and impartial.4 The APS Code of Conduct has 13 requirements relating to: behaving honestly and with integrity in connection with APS employment; acting with care and diligence; treating people with respect and courtesy; complying with all applicable Australian laws; complying with any lawful and reasonable direction; maintaining confidentiality; avoiding conflicts of interest and disclosing material personal interests; proper use of resources; not providing false or misleading information; not misusing power or authority; upholding the APS values; upholding the integrity and good reputation of the agency and the APS; and upholding the good reputation of Australia when overseas.

3. Under the PS Act, further integrity obligations apply to agency heads5 and members of the Senior Executive Service (SES)6, which comprise the senior cadre of the APS.

4. The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) establishes the overarching governance, performance and accountability framework for resource use and management within the Commonwealth public sector as a whole, including all members of the APS. It is a principles-based framework that imposes high expectations on the sector, including ‘high standards of governance, performance and accountability’.7

5. The PGPA Act contains ‘general duties of officials’ applying to both the accountable authority of the PGPA entity8 and entity officials. The general duties relate to: acting with care and diligence; acting honestly, in good faith and for a proper purpose; not misusing one’s position; the proper use of information; and disclosing interests.9 Taken together, the general duties establish an overarching framework for integrity, probity and ethical behaviour applying to the accountable authorities and officials of all PGPA Act entities, including all members of the APS.

6. There are also ‘general duties of accountable authorities’ applying to the accountable authority of a PGPA entity. These include the duty to govern the entity in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources for which the accountable authority is responsible.10

7. The office of Australian Public Service Commissioner (Commissioner) is established under the PS Act.11 The Commissioner’s functions are set out in section 41 of the PS Act and include the following functions considered in this audit.

- To uphold high standards of integrity and conduct in the APS.12

- To promote the APS Values, the APS Employment Principles and the Code of Conduct.13

- To evaluate the extent to which Agencies incorporate and uphold the APS Values and the APS Employment Principles.14

- To partner with Secretaries in the stewardship of the APS.15

- To provide advice and assistance to Agencies on public service matters.16

- To evaluate the adequacy of systems and procedures in Agencies for ensuring compliance with the Code of Conduct.17

8. The Commissioner and APS employees assisting the Commissioner together constitute a statutory agency under the PS Act, known as the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC).18 In 2022–23 the departmental expenses of the APSC were $80.8 million.19 At 30 June 2023, the APSC had 373 employees.20

9. Within the Commonwealth public sector, which includes the APS, there is both collective and individual responsibility for maintaining integrity, probity and ethical conduct — shared by framework policy owners, the heads of public sector organisations, and their personnel.

10. Framework policy owners establish the rules of operation in key areas and then largely rely on the accountable authorities of PGPA Act entities and the agency heads of APS agencies to be responsible for culture and compliance within public sector organisations. In that respect the frameworks are devolved and largely self-regulating. Under the principles-based approach, mandatory rules are largely set to control actions where risks are deemed highest. Key policy owners include the Department of Finance for the PGPA Act framework and the APSC for the PS Act integrity framework.21

11. The role of policy owners in maintaining a culture of integrity in the sector, including respect for the rule of law, has been a focus of recent reviews, initiatives and investigations relating to the APS and its performance. These have included the following.22

- The 2019 Independent review of the APS (Thodey review) and 2022 government APS reform agenda intended to build on the Thodey review.

- The 2023 Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme (Royal Commission), government response to the Royal Commission recommendations, and 16 Code of Conduct processes resulting from the Royal Commission.

- The 2023 APS Integrity Action Plan intended to address the 2022 government APS reform agenda and 2023 Royal Commission findings.

- The 2023 Code of Conduct inquiry and termination of a departmental secretary.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

12. The Australian Parliament has provided, in the PS Act, that all members of the APS are subject to the integrity, probity and ethical obligations specified in the Act. The Parliament has also provided that one of the three broad functions of the Commissioner under the Act is ‘to uphold high standards of integrity and conduct in the APS’.23 The function of upholding APS integrity standards occurs in a changing and often dynamic operating environment, which in recent years has featured the following.

- Reviews, initiatives and investigations, which have often focused on perceived shortcomings in upholding APS integrity, probity and ethics, including at the highest levels of APS leadership and the Secretaries Board.

- Australian Government statements that the Royal Commission Robodebt Scheme identified ‘serious failings within the Australian Public Service’.24 The APSC has stated that ‘Rebuilding trust in the APS is a priority’25 and that this process includes ‘reinforcing a culture with integrity at its core’.26

- Leadership change at the top of the APS, with 69 per cent turnover of departmental secretaries between July 2022 and December 2023.27

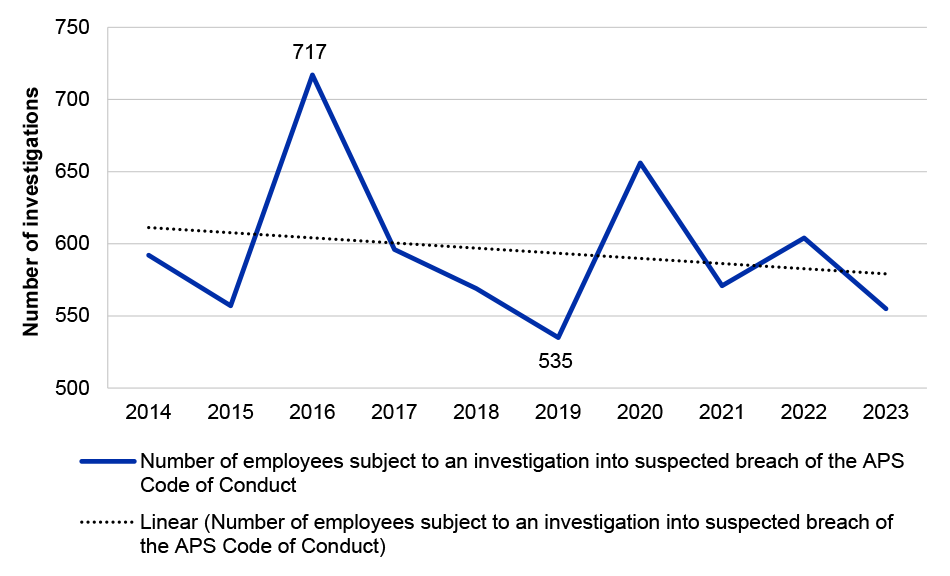

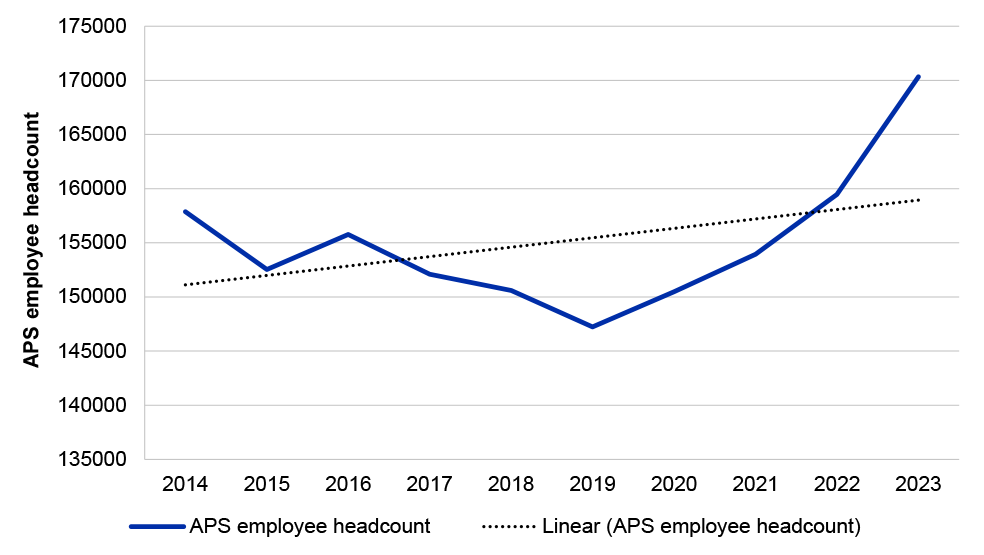

- Growth in APS employment. The APSC reported in March 2024 that at 31 December 2023 the APS headcount was 177,442, a 9.9 per cent increase since December 2022.28

- Establishment of the National Anti-Corruption Commission to: detect, investigate and report on serious or systemic corruption in the Commonwealth public sector; and educate the sector and the public about corruption risks and prevention.29

13. There is ongoing parliamentary interest in APS integrity, probity and ethics, including by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA), which in June 2023 adopted an inquiry into probity and ethics in the Australian public sector. This audit provides independent assurance and reporting to the Parliament on the APSC’s administration of statutory functions relating to upholding high standards of integrity and ethical conduct in the APS.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

14. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the APSC’s administration of statutory functions relating to upholding high standards of integrity and ethical conduct in the APS.

15. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Has the APSC effectively promoted the APS Values and Code of Conduct?

- Has the APSC effectively monitored and evaluated agencies’ implementation of the APS Values and Code of Conduct?

- Has the APSC effectively contributed to stewardship of the APS?

16. The ANAO reviewed the APSC’s administration for the period July 2022 to December 2023.

Conclusion

17. The APSC was partly effective in its administration of statutory functions relating to upholding high standards of integrity and ethical conduct in the APS during the audit review period (July 2022 to December 2023). The APSC’s approach was largely activity-driven and it did not have relevant strategies, linked to measurable outcomes, to guide its efforts. As a consequence, the APSC could not demonstrate or provide assurance on whether its activities relating to integrity functions were well directed or fully effective. In the context of an operating environment focused on perceived shortcomings in APS integrity, the APSC was in the process of developing a more strategic approach.

18. The APSC was partly effective in promoting the APS Values and Code of Conduct and in providing advice and assistance to APS agencies on public service matters. The APSC did not have a strategy, linked to outcomes which can be measured, for promoting the APS Values and Code of Conduct and its approach to this function was largely activity-driven. While the APSC communicated integrity and ethical requirements and expectations through a variety of activities, including training and guidance, they were not guided by a risk-based strategy. APSC guidance was revised or new guidance issued, to manage identified risks and issues, without reference to a forward engagement strategy. The APSC had limited arrangements in place to provide assurance to the Commissioner and Parliament that it had effectively promoted the APS Values and Code of Conduct.

19. The APSC did not have a sound basis for monitoring and evaluating the extent to which agencies incorporate and uphold the APS Values, or the adequacy of systems and procedures in agencies to ensure compliance with the Code of Conduct. There was no mechanism to provide assurance or insight to the Commissioner or the Parliament on agencies’ implementation of the APS Values and Code of Conduct.

20. The APSC did not have a documented strategy or plan to support the Commissioner’s functions relating to stewardship and partnering with secretaries or agency heads. The APSC did not clearly articulate the stewardship concept appearing since 2013 in the PS Act and did not measure its effectiveness in administering the stewardship function. The APSC’s approach to the stewardship function was largely activity-driven, and it contributed to or led a range of APS improvement initiatives, including with the Secretaries Board.

Supporting findings

Promote, advise and assist

21. The APSC did not have a strategy, linked to outcomes which, can be measured, for promoting the APS Values and Code of Conduct during the audit review period and its approach to this function was largely activity-driven. The APSC had two strategies with components relating to the promotion of integrity, ethics and the APS Values and Code of Conduct — an APS Workforce Strategy and APS Academy Engagement and Communication strategy. These two strategies, when read together, do not equate to a strategy for promoting the APS Values and Code of Conduct.

22. The APSC provided or administered guidance, support and training/event offerings intended to promote the APS Values and Code of Conduct. While the APSC communicated integrity and ethical requirements and expectations through these activities, they were not guided by a risk-based strategy.

23. The APSC had limited arrangements in place to provide assurance to the Commissioner and Parliament that it had effectively promoted the APS Values and Code of Conduct. Data collection and feedback received on APSC training and guidance did not link to a structured approach to assessing whether the APSC’s activities to ‘promote’ were achieving their intended purpose. There was no record of the APSC’s most senior internal committees — the Executive Board and Executive Committee — discussing issues relating to the APS Values during the audit review period. Issues relating to the APS Code of Conduct were discussed at 13 per cent of Executive Board meetings and five per cent of Executive Committee meetings. More generally, there were deficiencies in the APSC’s record keeping arrangements for its governance committees.

24. The enterprise-level risks documented in the APSC’s enterprise risk register did not directly relate to the APSC’s delivery of its statutory functions relating to the APS Values, Code of Conduct or integrity. This was in the context of an operating environment which featured ongoing scrutiny of perceived shortcomings in upholding APS integrity, including at the highest levels of APS leadership. (See paragraphs 2.4 to 2.96)

25. The ANAO reviewed six APSC mechanisms in operation during the audit review period to provide advice and assistance to APS agencies on public service matters: the Integrity Agencies Group (IAG); the Ethics Advisory Service (EAS); Ethics Contact Officer network (ECOnet); Cross-agency Code of Conduct Practitioners’ Forum (conduct forum); APS Agency Survey (agency survey); and consultation and advice on suspected breaches of the APS Code of Conduct.

26. The IAG offers opportunities for information-sharing amongst participants. The EAS received 684 enquiries during the audit review period. The APSC is not able to demonstrate what advice or assistance it provided on public service matters to the agencies represented at meetings of ECOnet or the conduct forum.

27. The APSC used the 2021 agency survey results to develop its Integrity Metrics Resource, which was released in 2022. If used by agencies, it provides a basis to focus their efforts to lift integrity measurement, monitoring and reporting.

28. During the audit review period, APSC guidance was revised or new guidance issued, to manage identified risks and issues, without reference to a forward engagement strategy. The APSC issued timely guidance and advice for APS agency heads in 2023, relating to the management of Code of Conduct reviews following the report of the Royal Commission Robodebt Scheme. (See paragraphs 2.97 to 2.147)

Evaluate

29. The APSC did not have fit-for-purpose arrangements to evaluate the extent to which agencies incorporate and uphold the APS Values, or a documented strategy linked to outcomes which could be measured.

30. The APSC collected information from several mechanisms and activities to inform its understanding of issues and developments in the APS and which may influence its thinking, actions and priorities. It has not leveraged the data and insights gained from its various activities to evaluate the extent to which agencies incorporate and uphold the APS Values. This does not provide the Commissioner or Parliament with broader insight or assurance on the extent to which agencies uphold the APS Values.

31. A capability review conducted in 2023 assessed the APSC as having a maturity rating of ‘developing’ in respect to ‘Review and evaluation’. The APSC advised the ANAO in November 2023 that it has begun work to systematise its use of data to observe patterns or areas of concern for agencies. (See paragraphs 3.43 to 3.44)

32. The APSC did not have fit-for-purpose arrangements to evaluate the adequacy of systems and procedures in agencies for ensuring compliance with the Code of Conduct, or a documented strategy linked to outcomes which could be measured.

33. There was no mechanism to provide assurance or insight to the Commissioner or Parliament on the adequacy of systems and procedures in agencies for ensuring compliance with the Code of Conduct. (See paragraphs 3.45 to 3.48)

Stewardship

34. The APSC did not have a documented strategy or plan to support the Commissioner’s functions relating to stewardship and partnering with secretaries or agency heads — including where the Commissioner is independently performing functions under the PS Act — or to measure its effectiveness in administering the Commissioner’s stewardship function.

35. The APSC’s approach to the stewardship function was largely activity-driven, and included: participation in sector-wide boards and committees with integrity-related roles or functions, such as the Secretaries Board; briefing and induction activity for new secretaries and other agency heads; engaging with APS agency heads on SES Code of Conduct matters; providing advice and guidance on integrity issues; and involvement in SES recruitment and talent management activities.

36. The APSC has undertaken planning relating to the addition of ‘stewardship’ as a sixth APS Value in the PS Act. The Public Service Amendment Bill 2023 received royal assent on 11 June 2024 and is now known as the Public Service Amendment Act 2024. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.34)

Recommendations

37. This report makes four recommendations to the Australian Public Service Commission.

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.30

The Australian Public Service Commission develop a strategy to document and guide its objectives, key activities, relationships with key stakeholders, and desired outcomes relating to the statutory function to ‘promote’ the APS Values and Code of Conduct set out in paragraph 41(2)(e) of the Public Service Act 1999.

Australian Public Service Commission response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.80

The Australian Public Service Commission develop and implement an evaluation strategy for its integrity training to determine if its suite of integrity training is achieving the intended outcomes.

Australian Public Service Commission response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.86

The Australian Public Service Commission should review record keeping arrangements for its governance committees.

Australian Public Service Commission response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.40

The Australian Public Service Commission develop an evaluation strategy and review its current evaluation methodology to improve the level of assurance provided to the Commissioner and Parliament on whether agencies incorporate and uphold the APS Values, and the adequacy of agencies’ systems and procedures for ensuring compliance with the APS Code of Conduct.

Australian Public Service Commission response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

38. The proposed final performance audit report was provided to the APSC. The summary response from the APSC is provided below and the full response is at Appendix 1. Improvements observed by the ANAO during the audit are at Appendix 2.

Australian Public Service Commission

The Commission welcomes the observations of the ANAO in this report, and agrees with the four recommendations and intent of the opportunities for improvement. These recommendations are timely given our ongoing program of work to strengthen the articulation of our purpose, key activities, priorities and performance measures. In addition, actions to address these recommendations will dovetail with work arising from our Capability Review to enhance strategies and tools for data and stakeholder engagement, as well as corporate systems for governance, risk, information management and assurance.

In our stewardship role, we will partner with the Attorney General’s Department to develop an enduring APS Integrity Strategy to articulate a clear narrative for integrity activities and reforms, and to clearly identify the role and actions all agencies and public servants are required to embrace to demonstrate excellence in integrity. In parallel, the Commission will bring together its broad suite of integrity initiatives into an overarching integrity strategy, supporting impact and outcome-focussed evaluation to strengthen assurance over the performance of our legislated functions.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

39. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Records management

1. Background

Introduction

Australian Public Service

1.1 The Australian Public Service (APS) is established by the Public Service Act 1999 (PS Act).30 It consists of agency heads and APS employees engaged under the PS Act.31

1.2 The APS is one part of the wider Commonwealth public sector. At 30 June 2023 the APS employee headcount was 170,33232 across 104 entities.33 At 1 March 2024 there were 191 Commonwealth entities and companies.34 Many of these organisations do not engage staff under the PS Act and a number can engage officials under their enabling legislation as well as the PS Act.35

Public Service Act 1999

1.3 The APS operates largely under principles-based frameworks, including that established by the PS Act. While principles-based, the PS Act framework imposes high expectations. The ‘main objects’ of the PS Act are:

(a) to establish an apolitical public service that is efficient and effective in serving the Government, the Parliament and the Australian public; and

(b) to provide a legal framework for the effective and fair employment, management and leadership of APS employees; and

(c) to define the powers, functions and responsibilities of Agency Heads, the Australian Public Service Commissioner and the Merit Protection Commissioner; and

(d) to establish rights and obligations of APS employees.36

APS integrity obligations

Public Service Act

1.4 Members of the APS are subject to integrity obligations specified in the PS Act, including the APS Values37 and APS Code of Conduct.38

1.5 At 19 February 2024 the PS Act specified five APS Values — committed to service, ethical, respectful, accountable and impartial.39 The explanatory memorandum for the Public Service Bill 1999 stated that:

The Values are designed to … provide the philosophical underpinning for the APS … reflect public expectations of the relationship between public servants and the Government, the Parliament and the Australian community … articulate the culture and operating ethos of the APS … and support and inform the Commissioner’s Directions to be issued under the authority of the Bill.40

1.6 The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC, discussed further at paragraphs 1.21 to 1.22) states that:

The APS Values articulate the parliament’s expectations of public servants in terms of performance and standards of behaviour. The principles of good public administration are embodied in the APS Values.41

1.7 The APS Code of Conduct has 13 requirements, relating to: behaving honestly and with integrity in connection with APS employment; acting with care and diligence; treating people with respect and courtesy; complying with all applicable Australian laws; complying with any lawful and reasonable direction; maintaining confidentiality; avoiding conflicts of interest and disclosing material personal interests; proper use of resources; not providing false or misleading information; not misusing power or authority; upholding the APS values; upholding the integrity and good reputation of the agency and the APS; and upholding the good reputation of Australia when overseas.

1.8 The PS Act refers to the Code of Conduct as rules.42 The explanatory memorandum for the Public Service Bill 1999 stated that:

The Bill will include a statutory Code of Conduct … This will ensure that the Code is legally enforceable and will strengthen its role as a public statement of the standards of behaviour and conduct that are expected of those who work in core public employment.43

1.9 Under the PS Act, further integrity obligations apply to agency heads and members of the Senior Executive Service (SES), which comprise the senior cadre of the APS.44 These include the declaration of interests and the declaration of gifts, benefits and hospitality.

1.10 Box 1 sets out integrity obligations in the PS Act.

|

Box 1: Integrity obligations — Public Service Act 1999 |

|

APS Values (section 10) Committed to service

Ethical

Respectful

Accountable

Impartial

APS Code of Conduct (section 13)

Breaches of the Code of Conduct (section 15)

Senior Executive Service (SES)

Agency Heads

Secretaries

Heads of Executive Agencies

|

Note a: Subsection 14(2) provides that statutory office holders are bound by the Code of Conduct, subject to any regulations made under subsection 14(2A). The regulations may make provision in relation to the extent to which statutory office holders are bound by the Code of Conduct.

Commonwealth finance law

1.11 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) establishes the overarching governance, performance and accountability framework for resource use and management within the Commonwealth public sector as a whole. It is a principles-based framework that imposes high expectations on the sector, including ‘high standards of governance, performance and accountability’.45 It is part of the Commonwealth finance law.46

1.12 The interaction between the PS Act and Commonwealth finance law is recognised in section 32 of the PGPA Act, which provides that the finance law is an Australian law for the purposes of subsection 13(4) of the PS Act.47 If the PS Act applies to an official of a PGPA entity, the official will be required under subsection 13(4) of the PS Act to comply with applicable Australian laws, which include the finance law. This means that if the official contravenes the finance law, sanctions may be imposed on the official under section 15 of the PS Act.48

1.13 The PGPA Act contains ‘general duties of officials’ applying to both the accountable authority of the PGPA entity49 and entity officials, which are relevant to integrity, probity and ethics. The general duties relate to: acting with care and diligence; acting honestly, in good faith and for a proper purpose; not misusing one’s position; the proper use of information; and disclosing interests.50 Taken together, the general duties establish an overarching framework for integrity, probity and ethical behaviour applying to the accountable authorities and officials of all PGPA Act entities.

1.14 There are also ‘general duties of accountable authorities’ applying to the accountable authority of a PGPA entity. These include the duty to govern the entity in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources for which the accountable authority is responsible.51 Proper means efficient, effective, economical and ethical use or management of public resources.52 The accountable authority is authorised to issue Accountable Authority Instructions, which can impose obligations additional to the minimum standards established under the PGPA Act and PGPA Rule.

1.15 In addition, activity-specific frameworks will often contain ethical requirements focused on the activity they regulate. These include the frameworks for: grants administration; government procurement; government advertising; protective security; appearing before parliament; the caretaker period; liaising with lobbyists; conducting investigations; legal work; risk management; and fraud control. Members of the APS must comply with all applicable obligations established by these frameworks.53

Non-APS personnel

1.16 The integrity obligations applying to contractors are managed in different ways, at an agency level, as there is no whole-of-workforce framework or approach applying across the APS. At 19 February 2024 this was the case notwithstanding the fact that a large number of contractors were doing work in and as part of the operations of APS agencies, alongside APS employees, as part of a mixed workforce.54

Australian Public Service Commissioner

1.17 The office of Australian Public Service Commissioner (Commissioner) is established under the PS Act.55

1.18 Box 2 sets out the Commissioner’s functions set out in the PS Act. The functions underlined in Box 2 are the main focus of this audit.56

1.19 The Commissioner is also the Deputy Chair of the Secretaries Board established by the PS Act.57 The PS Act sets out the board’s membership58 and functions.59 The board also appears in other sections of the PS Act (see footnote 31).

|

Box 2: Australian Public Service Commissioner’s functions — section 41 Public Service Act 1999 |

|

Commissioner’s functions (section 41)

|

Note a: ANAO comment:

● paragraph 57(1)(c) provides that the roles of the Secretary of a Department include ‘leader, providing stewardship within the Department and, in partnership with the Secretaries Board, across the APS’; and

● paragraph 64(3)(a) provides that one of the functions of the Secretaries Board is ‘to take responsibility for the stewardship of the APS and for developing and implementing strategies to improve the APS’.

Commissioner’s Directions

1.20 The Commissioner may issue written directions in relation to any of the APS Values for the purpose of: ensuring that the APS incorporates and upholds them; and determining (where necessary) their scope or application.60 The Australian Public Service Commissioner’s Directions 2022, which commenced on 1 February 2022,61 include directions relating to the APS Values and Integrity of the APS. Box 3 sets out those parts of the directions.

|

Box 3: Australian Public Service Commissioner’s Directions 2022 |

|

Part 2 – APS Values Overview of this part (section 11)

APS to incorporate and uphold APS Values (section 12)

Ethical (section 14)

Accountable (section 16)

Impartial (section 17)

Part 3 – Integrity of the APS

|

Australian Public Service Commission

1.21 The Commissioner and APS employees assisting the Commissioner62 together constitute a statutory agency under the PS Act, known as the Australian Public Service Commission (APSC).63 In 2022–23 the departmental expenses of the APSC were $80.8 million.64 At 30 June 2023, the APSC had 373 employees.65

1.22 Box 4 sets out the APSC’s purpose as expressed in its recent corporate plans.

|

Box 4: Australian Public Service Commission corporate plans — purpose statement |

|

Corporate plan 2022–26 (signed 26 August 2022)

Corporate plan 2023–27 (signed August 2023)

|

Note a: Australian Public Service Commission, Corporate plan 2022–26, 26 August 2022, p. 1, available from https://previewapi.transparency.gov.au/delivery/assets/80a82ed1-3e33-027b-b7e0-6493f97f18f8/6676cc37-836a-4422-a155-dce226debe05/apcs_corporate_plan_2022-26.pdf [accessed 28 November 2023].

Note b: Australian Public Service Commission, Corporate Plan 2023–27, August 2023, p. 1, available from https://www.apsc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-08/23552%20APSC%20-%20Corporate%20Plan%202023-27_Web.pdf [accessed 28 November 2023].

1.23 The APSC is part of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Portfolio.66 The PS Act provides for certain powers to be exercised by the Prime Minister, Public Service Minister or agency minister (responsible ministers). Section 78 of the PS Act provides for the delegation of ministerial powers and those of the Commissioner. At November 2023, the responsible ministers were the Prime Minister, Minister for the Public Service, and Assistant Minister for the Public Service.

2023 APSC capability review

1.24 The 2023 capability review of the APSC67, the first in a planned program of reviews of APS agencies, considered that the APSC’s ‘most important focus areas’ included: leading on integrity for the APS by focusing resources to assert itself as a leader on integrity; providing clear, authoritative guidance to agencies, with a stronger position stance; and building whole-of-service capability.68

Integrity resources

1.25 The APSC provides a variety of information and resources on integrity, including through its website.69

1.26 An APSC fact sheet on ‘Defining integrity’ states the following.

What do we mean when referring to integrity?

Integrity in the APS is the pursuit of high standards of professionalism—both in what we do and in how we do it. It is the foundation of trust on which public service effectiveness is built. Integrity is the craft of bringing ethics and values to life through our work and our behaviour, and earning the trust of the public in our ability to deliver the best outcomes for Australia.

Integrity covers several different and overlapping aspects that relate to our conduct, how we work individually and as a collective, and includes:

- compliance with legislative frameworks, policies and practices, including those set by APS agencies – compliance ensures standards for integrity are being met

- a values-based approach that promotes ethical decision-making and reflection in how we undertake work as APS employees

- institutional integrity, where organisational systems, policies and practices are purposeful, legitimate and trustworthy

- pro-integrity culture, in which there is a positive, conscious effort to make integrity a central consideration of all activities.70 [emphasis in original]

1.27 The APSC also provides the following short definition of integrity in its fact sheet on ‘Defining integrity’.

From a public service context, integrity is:

the pursuit of high standards of APS professionalism, which in turn means doing the right thing at the right time to deliver the best outcomes for Australia sought by the government of the day.71 [emphasis in original]

Roles and responsibilities

1.28 Within the Commonwealth public sector, which includes the APS, there is both collective and individual responsibility for maintaining integrity, probity and ethical conduct — shared by framework policy owners, the heads of public sector organisations, and their personnel. The approach taken to compliance by each of these actors is fundamental to integrity outcomes in the public sector context, as ‘compliance ensures standards for integrity are met’.72

1.29 In the APS State of the Service Report 2022–23, the Commissioner stated that:

The Australian Public Service, through its 104 agencies, and more than 170,000 staff, undertakes diverse work which affects all Australians.

The foundation for this, and the requirements of our jobs – what we do, and how we do it – is set out in law, especially the Public Service Act and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act. As public servants, we serve the Government, the Parliament and the Australian people. The way we do this must be in keeping with the APS Values and the APS Code of Conduct.73

1.30 In the APS State of the Service Report 2021–22, the APSC stated that:

The bedrock of the APS is its culture – a culture built upon impartiality, commitment to service, accountability, respect, and the highest standards of ethical behaviour.74

1.31 In the Commonwealth public sector, framework policy owners establish the rules of operation in key areas and then largely rely on the accountable authorities of PGPA Act entities and the agency heads of APS agencies to be responsible for culture and compliance within public sector organisations. In that respect the frameworks are devolved and largely self-regulating. Under the principles-based approach, mandatory rules are largely set to control actions where risks are deemed highest. Key policy owners include the Department of Finance for the PGPA Act framework and the APSC for the PS Act integrity framework. The PS Act also identifies: a ‘stewardship’ function for the Secretaries Board established under the Act; a ‘stewardship’ role for secretaries; and that a function of the Commissioner is ‘to partner with Secretaries in the stewardship of the APS’.75

1.32 The role of policy owners in maintaining a culture of integrity in the sector, including respect for the rule of law, has been a focus of recent reviews, initiatives and investigations relating to the APS and its performance. These are discussed in the next section.

Reviews, initiatives and investigations relating to the APS

2019 Independent review of the APS (Thodey review)

1.33 The 2019 Independent review of the APS (Thodey review)76 recommended the reinforcement of APS institutional integrity to sustain the highest standards of ethics and build a pro-integrity culture and practices in the APS (Recommendation 7).77

1.34 The related 2020 Report into consultations regarding APS approaches to ensure institutional integrity (Sedgwick report) set out the findings of consultations by Mr Stephen Sedgwick, a former Public Service Commissioner and Finance secretary, and made recommendations to assist in devising a response to recommendation 7 of the Thodey review.78 Appendix 3 of this audit report outlines details of key recommendations related to the Thodey review and other relevant recommendations made in the other reviews discussed below.

2022 government APS reform agenda

1.35 On 13 October 2022 the Australian Government set out an ‘APS Reform agenda’ that ‘will build on the Thodey Review’.79 The government stated that the agenda had four priority areas. These were an APS that: embodies integrity in everything it does; puts people and business at the centre of policy and services; is a model employer; and has the capability to do its job well.

1.36 The Australian Government indicated that integrity was the first of the four priorities, as follows.

Priority One: An APS that embodies integrity in everything it does

I’ll start with integrity – because the public service is one of the critical pillars of political integrity.

It must be empowered to be honest and truly independent.

To defend legality and due process.

And to deliver advice that the government of the day might not want to hear just as loudly as the advice that we do.

This cannot just be done at a department level, or a secretary level, or even a deputy secretary level.

Every single public servant has a role to play when it comes to making sure that the APS uses its position and influence wisely, and uses that power to do well by others.80

1.37 In May 2023, the government outlined eight outcomes that its agenda was expected to achieve. The outcomes included the following.

Outcome 1: Public sector employees act with and champion integrity

Outcome 2: Public service employees are stewards of the public service81

1.38 As part of its agenda, in June 2023 the government introduced the Public Service Amendment Bill 2023 to Parliament, to amend the PS Act. One change was to add ‘stewardship’ as a sixth APS Value.82 The Bill stated the following.

Stewardship

The APS builds its capability and institutional knowledge, and supports the public interest now and into the future, by understanding the long-term impacts of what it does.

1.39 The explanatory memorandum for the Bill stated that the amendments in the Bill:

support the Government’s APS Reform priority to create an APS that acts with integrity in everything it does. Initiatives in this area will build public trust and strengthen standards of integrity in our federal government. Specifically, the Bill proposes to … include a new APS Value of Stewardship, highlighting the important and enduring role that all public servants play in stewarding the APS, and serving Government, the Parliament, and the Australian public, now and into the future … 83

[it] complements the stewardship duties of Secretaries (subsection 57(c)), Secretaries Board (subsection 64(3)(a)); and the Commissioner (subsection 41(2)(g)), by supporting APS employees to understand their role and individual contributions in stewarding the public service.84

1.40 As discussed in the explanatory memorandum, the term ‘stewardship’ appears in a number of places in the PS Act. It has not previously been defined in the PS Act.

1.41 In a December 2022 address to the APS, the Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) discussed stewardship, stating that ‘Alongside our roles of policy, impartial advice and service delivery, there is another key responsibility for the public service: stewardship.’ The secretary further stated that:

Stewardship is the ability to anticipate, plan, record outcomes, and learn. Stewardship is about now and the endless future, a public service with a shared memory and capacity to act when required.85

1.42 In November 2023 the APSC described the new value, and its implications for APS integrity, as follows.

This proposed new value aligns with the Australian Government’s priority for an APS that embodies integrity in everything it does. It highlights the important and enduring role that all public servants play in stewarding the APS, and serving the Government, Parliament and Australian public. Stewardship underpins the integrity of advice and implementation of Government policies and programs. It also builds trust through the collective harnessing of experience, diversity and resources for the ongoing and sustainable delivery of policies and programs.

Stewardship captures the notion of responsibility for how an institution performs now and into the future. It is central to a trusted, professional and high-performing public service. It means taking steps today to ensure the APS is equipped to address tomorrow’s challenges and continues to support the Australian Government and the Parliament and meet the interests of the Australian community.86

1.43 The Public Service Amendment Bill 2023 received royal assent on 11 June 2024 and is now known as the Public Service Amendment Act 2024. The Minister for the Public Service provided a progress report on implementation of the government’s APS reform agenda in an ‘Annual statement on APS Reform’ on 2 November 2023.87

2023 Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme

1.44 The July 2023 Report of the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme (Royal Commission) reviewed a Department of Human Services scheme which was found not to comply with the Social Security Act 1991.88

1.45 The Royal Commission included a chapter on ‘Improving the Australian Public Service’ (Chapter 23). The chapter included commentary on the application of the APS Values (parts one and four), recent APS reviews (part two), APS structural arrangements (part three), the obligations of APS senior executives and agency heads (part five), and record-keeping failures (part seven).89

1.46 The Royal Commission made 57 recommendations90, including the following recommendations directly affecting the APSC.

Recommendation 23.2: Obligations of public servants

The APSC should, as recommended by the Thodey Review, deliver whole-of-service induction on essential knowledge required for public servants.

Recommendation 23.7: Agency heads being held to account

The Public Service Act should be amended to make it clear that the Australian Public Service Commissioner can inquire into the conduct of former Agency Heads. Also, the Public Service Act should be amended to allow for a disciplinary declaration to be made against former APS employees and former Agency Heads.

Recommendation 23.8: Documenting decisions and discussions

The Australian Public Service Commission should develop standards for documenting important decisions and discussions, and the delivery of training on those standards.91

1.47 The Royal Commissioner’s letter of transmittal to the Governor-General also advised that:

I have provided to you an additional chapter of the report which has not been included in the bound report and is sealed. It recommends the referral of individuals for civil action or criminal prosecution. I recommend that this additional chapter remain sealed and not be tabled with the rest of the report so as not to prejudice the conduct of any future civil action or criminal prosecution.

I am also submitting relevant parts of the additional chapter of the report to heads of various Commonwealth agencies; the Australian Public Service Commissioner, the National Anti-Corruption Commissioner, the President of the Law Society of the Australian Captial [sic] Territory and the Australian Federal Police.92

1.48 In the preface to the report, the Royal Commissioner stated the following.

It is remarkable how little interest there seems to have been in ensuring the Scheme’s legality, how rushed its implementation was, how little thought was given to how it would affect welfare recipients and the lengths to which public servants were prepared to go to oblige ministers on a quest for savings. Truly dismaying was the revelation of dishonesty and collusion to prevent the Scheme’s lack of legal foundation coming to light. Equally disheartening was the ineffectiveness of what one might consider institutional checks and balances – the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Office, the Office of Legal Services Coordination, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner and the Administrative Appeals Tribunal – in presenting any hindrance to the Scheme’s continuance.

The report makes a number of recommendations. Some are directed at strengthening the public service more broadly, some to improving the processes of the Department of Social Services and Services Australia. Others are concerned with reinforcing the capability of oversight agencies. A sealed chapter contains referrals of information concerning some persons for further investigation by other bodies. That in part is intended as a means of holding individuals to account, in order to reinforce the importance of public service officers’ acting with integrity.

But as to how effective any recommended change can be, I want to make two points. First, whether a public service can be developed with sufficient robustness to ensure that something of the like of the Robodebt Scheme could not occur again will depend on the will of the government of the day, because culture is set from the top down.93

1.49 On 10 July 2023, the Secretary of PM&C and the Commissioner released a joint message to the APS on the Royal Commission, advising the following.

- A taskforce led by PM&C, the Attorney-General’s Department, and the APSC would be established to support Ministers in preparing the Australian Government’s response to the Royal Commission recommendations.

- Separate to this, the APSC would oversee a process to determine if public servants with adverse findings had breached the APS Code of Conduct. This process would be established under the Commissioner’s powers in the PS Act and would be ‘designed to be fair, independent, and consistent.’

- The APSC had engaged Mr Stephen Sedgwick AO to exercise these powers as an Independent Reviewer. Mr Sedgwick would make inquiries and determinations about whether an individual referred for inquiry had breached the APS Code of Conduct.94

Code of Conduct processes

1.50 On 3 August 2023 the APSC provided additional information on the Code of Conduct processes, including the appointment of a supplementary reviewer and a sanctions adviser.95 The APSC also stated that:

The Royal Commission only referred individuals to the Australian Public Service Commissioner in the sealed section of its report who, if found to have breached the Code of Conduct, could be subject to a sanction. This means that only current APS employees who may be subject to sanctions were proposed for a possible Code of Conduct investigation by the APSC.

To ensure equitable treatment of current APS employees, former APS employees and former APS Agency Heads, further consideration was given to whether additional referrals to the centralised code of conduct mechanism, was warranted with respect to:

- former APS employees, by Agency Heads, in consultation with the Code of Conduct Taskforce in the APSC;

- current APS employees mentioned in the open version of the Royal Commission report but not referred in the sealed section, by Agency Heads, in consultation with the Code of Conduct Taskforce in the APSC; and

- former Agency Heads, with the Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet advising the Minister for the Public Service to make referrals under section 41(2)(k) of the Public Service Act 1999 to the Australian Public Service Commissioner.

The [APS] Commissioner has now received 16 referrals to the APSC’s centralised code of conduct mechanism, consisting of:

- current APS employees named in the sealed section of the Royal Commission’s report

- former APS employees referred by their most recent Agency Head, and

- former Agency Heads referred by the Minister following advice from the Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

1.51 The APSC provided a further update on 8 February 2024, as follows96:

Since the last update on 3 August 2023, the Code of Conduct Taskforce in the APSC has continued inquiries into all 16 referred matters.

To date:

- 15 investigations have proceeded to the issuing of notices outlining the grounds and categories for potential breach of the APS Code of Conduct.

- Of the 15 investigations, 4 individuals have been issued a preliminary determination that they have breached one or more elements of the APS Code of Conduct; 11 investigations remain current.

- One investigation has concluded as the individual’s actions did not meet the threshold to issue a notice of suspected breach.

Final determinations and, if appropriate, decisions about sanctions will be communicated to individuals once preliminary determinations are finalised. The timeframe for the conclusion of inquiries depends on various factors, including the complexity of each matter, the number of submissions and any extensions that may be requested by respondents.

The 16 matters are complex, with a significant volume of evidence. Sufficient time is required to allow the Independent Reviewers, Mr Stephen Sedgwick AO and Ms Penny Shakespeare, to conduct the inquiries in a manner that is robust and affords respondents appropriate procedural fairness.

Government response to Royal Commission recommendations

1.52 The Australian Government tabled its response to the Royal Commission’s recommendations on 13 November 2023.97 In respect to the APS, the ministerial foreword to the response stated that:

the Royal Commission found serious failings within the Australian Public Service and with the institutional checks and balances that should have put a stop to the Robodebt Scheme long before the Federal Court found it unlawful.98

1.53 The response also stated that ‘The Commission produced 56 valuable recommendations, which are principally directed at strengthening the Australian Public Service and capability of oversight agencies.’99

1.54 The government announced that it had accepted or accepted in principle the 56 recommendations made by the Royal Commission.100 The government accepted the three recommendations directly affecting the APSC, as discussed in paragraph 1.46.101

2023 APS integrity action plan

1.55 The APS Secretaries Board published an APS Integrity Action Plan102 and Integrity Good Practice Guide103 on 17 November 2023.

1.56 These documents were accompanied by ‘A message to all APS staff on APS integrity’ by the Secretary of PM&C and the Commissioner104 which stated the following.

Integrity is deeply important to our work in the public service. It underpins the trust of the Australian public, who rely on us to serve their interests and deliver the best outcomes for Australia.

The Secretaries Board is committed to promoting a pro-integrity culture where all staff feel confident to contribute ideas, provide frank and independent advice and report mistakes. In this spirit, Secretaries Board set up the APS Integrity Taskforce.

The Taskforce was asked to take a ‘bird’s-eye’ view of the APS integrity landscape, to identify gaps and look for opportunities to learn from and build upon the important work already progressing across the service. The work of the Taskforce complements the Integrity pillar of the government’s APS Reform agenda and the establishment of the National Anti-Corruption Commission. It is particularly pertinent in the context of the release of the Government’s Response to the Robodebt Royal Commission this week.

We encourage all staff to reflect on how integrity shapes our work for the Australian public. The ‘Integrity Good Practice Guide’ includes a range of practical examples of how you can contribute to a pro-integrity culture.

1.57 In an opening chapter on ‘The opportunity and why it matters’ in the APS Integrity Action Plan, the APS Integrity Taskforce (taskforce) stated that:

The integrity of the public service is one of the key drivers of public trust in government institutions. Recent lessons in public administration offer us a crucial opportunity for reflection, learning and action on integrity across the Australian Public Service (APS). We should grab it with both hands.

If failures in public administration do occur, we need to be willing to learn from these mistakes. Otherwise we risk eroding trust, which can undermine the APS as an effective democratic institution.

Integrity is a broad concept. At its heart it is concerned with individual and institutional trustworthiness, and demands high standards of ethical behaviour and respect for the law. The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) defines integrity as “doing the right thing at the right time” to “deliver the best outcomes for Australia sought by the government of the day”. In practice it means our behaviour matches the APS Values and we are accountable when it does not. At the systems level, integrity also refers to being ‘whole and undivided’, which means the APS needs to adopt a more strategic and coordinated approach to integrity across the service.105

1.58 The taskforce indicated that it had been asked to examine ‘culture’, ‘systems’ and ‘accountability’, and considered that:

The three action areas are interdependent, and all are necessary to be a public service with integrity at its heart. While the Taskforce has made recommendations on all three areas, there is a particular emphasis on the unique role of APS leadership as cultural architects for integrity. Our capability uplift recommendations therefore largely focus on SES. Integrity requires action at all levels, but without the right tone and demonstration from the top there will be no lasting impact.106

1.59 Box 5 sets out other themes highlighted by the taskforce in the opening chapter.

|

Box 5: Opening chapter of the 2023 APS Integrity Action Plan — ‘The opportunity and why it matters’a |

|

Compliance with frameworks (page 3)

Cultures of fear and silence (page 3)

Ministers and their advisers (page 3)

Delivery at all costs (page 4)

Legality (page 4)

|

Note a: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, APS Integrity Taskforce, Louder Than Words: An APS Integrity Action Plan, November 2023, pp. 2–5.

1.60 The taskforce indicated that it had sought to avoid duplication and used its recommendations ‘to identify gaps or strengthen and uplift existing work or good practices’.107 It made 15 recommendations and stated that five related to ‘culture’, five to ‘systems’ and five to ‘accountability’.108 The majority of the recommendations focused on improving the APS’ understanding and or application of existing professional, legal and performance expectations under the PS Act framework.

1.61 The taskforce’s Integrity Good Practice Guide stated that:

There is currently a high volume of activity across the Commonwealth to strengthen integrity systems and culture’ and indicated that it ‘presents initiatives that can be readily implemented across the integrity “lifecycle” of an entity, from strategy through to implementation, monitoring and evaluation.109

1.62 The document included sections on: implementing an integrity strategy; integrity champions and leadership; an integrated approach to integrity; a baseline of integrity knowledge; integrity rewards and recognition; integrity conversations and regular communications; integrity and ethics advice; integrity reporting channels; integrity evaluation and oversight; integrity data; and a finance integrity metrics register. the taskforce further stated that: ‘The emphasis is on integrity culture rather than pure compliance with integrity obligations.’110

2023 code of conduct inquiry and termination — Secretary Pezzullo

1.63 On 26 September 2023 the APSC announced111 that the Commissioner had received a referral from the Minister for Home Affairs ‘after concerns were raised about Secretary of the Department of Home Affairs, Mr Michael Pezzullo AO’. The APSC stated that Mr Pezzullo had stood aside as secretary and that the Commissioner had appointed a former APS Commissioner (Ms Lynelle Briggs AO) to lead an inquiry into alleged breaches of the APS Code of Conduct.

1.64 On 27 November 2023 the APSC further announced112 that the referral from the Minister for Home Affairs had been received on 24 September 2023 and that the subsequent inquiry had:

determined that Mr Pezzullo breached the Australian Public Service Code of Conduct on at least 14 occasions in relation to 5 overarching allegations, those allegations being that Mr Pezzullo:

- used his duty, power, status or authority to seek to gain a benefit or advantage for himself,

- engaged in gossip and disrespectful critique of Ministers and public servants,

- failed to maintain confidentiality of sensitive government information,

- failed to act apolitically in his employment,

- failed to disclose a conflict of interest

By way of sanction, Ms Briggs recommended that Mr Pezzullo’s appointment as a Secretary be terminated pursuant to section 59 of the Public Service Act.

1.65 On 27 November 2023 the Prime Minister announced113 that Mr Pezzullo’s appointment as Secretary of the Department of Home Affairs had been terminated and that:

This action was based on a recommendation to me by the Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and the Australian Public Service Commissioner, following an independent inquiry by Lynelle Briggs. That inquiry found breaches of the Australian Public Service Code of Conduct by Mr Pezzullo. Mr Pezzullo fully cooperated with the inquiry.

1.66 The appointment of a new Secretary of the Department of Home Affairs was announced on 28 November 2023 and the appointment commenced on that day.114

1.67 Mr Pezzullo was appointed as a secretary in October 2014 and was a member of the Secretaries Board discussed in paragraph 1.72. The board was established following amendments to the PS Act which took effect in 2013 and has had an APS ‘stewardship’ function since its creation.

State of the Service Report 2022–23

1.68 Subsection 44(1) of the PS Act states that the Commissioner must give a report to the agency minister, for presentation to the Parliament, on the state of the APS during the past year. Subsection 44(3) requires the report to be laid before each House of Parliament by 30 November 2023.

1.69 The Commissioner provided the State of the Service Report 2022–23 to the Assistant Minister for the Public Service on 6 November 2023115 and the report was presented for tabling in the Parliament on 29 November 2023.116 This was the 26th such report.

1.70 In the report, the APSC observed that:

Building community trust in the Australian Public Service is a priority, and there is a renewed focus on strengthening leadership and integrity across the service. Recommendations arising from the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme have been agreed, or agreed in principle, by the Australian Government. Code of Conduct matters raised by the Royal Commission are being assessed. The APS Integrity Taskforce has worked to identify system-wide improvements to support a pro-integrity culture at all levels.117

1.71 The report included commentary on recent criticisms of APS integrity, rebuilding trust, and strengthening leadership and integrity (see Box 6).

|

Box 6: State of the Service Report 2022–23 |

|

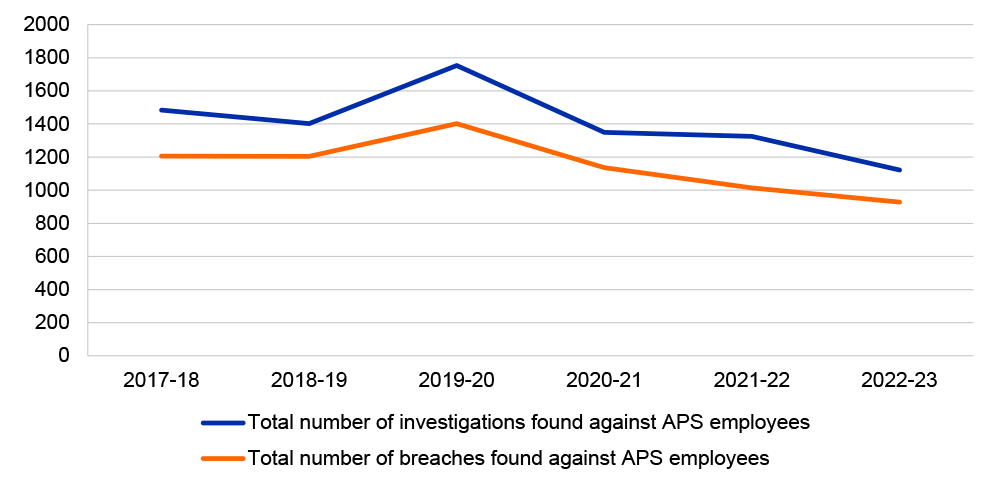

A message from the APS Commissioner (page 9) The Australian Public Service, through its 104 agencies, and more than 170,000 staff, undertakes diverse work which affects all Australians. The foundation for this, and the requirements of our jobs – what we do, and how we do it – is set out in law, especially the Public Service Act and the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act. As public servants, we serve the Government, the Parliament and the Australian people. The way we do this must be in keeping with the APS Values and the APS Code of Conduct. This report covers inquiries and other key issues for the APS over the past year, and how we are responding to them. Whether it is agencies considering the findings of major reviews like the Robodebt Royal Commission, or an individual employee reflecting on a wrong call, what matters is that the APS is a workplace where people can provide frank, evidence-based advice, and change course when needed. Operating context (page 17) It [the Australian Government] has announced a plan to build a stronger Australian Public Service through public sector reform. APS Reform is a service-wide undertaking to strengthen and empower the public service and increase trust and confidence in Australia’s public sector institutions. Frank, honest and evidence-based advice (page 76) Leaders in the Australian Public Service have a responsibility to serve the Government, the Parliament and the Australian public. They do so by providing advice that is relevant and comprehensive, is not affected by fear of consequences, and does not withhold important facts or bad news. These responsibilities are made clear in the Australian Public Service Commissioner’s Directions 2022. Recent public, critical examinations of the APS have found that these principles have not always been upheld. The Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme highlights failures in providing frank, evidence-based advice and implementing programs in accordance with the law. Rebuilding trust in the APS is a priority. It includes reinforcing a culture with integrity at its core. It includes creating an environment in which leaders and employees are robust in the way they formulate advice to Government, and authentic in how they put it forward. Rebuilding trust also means that public servants should have front of mind their responsibility to achieve the best results for the Australian community and the Government, as made clear in the APS Value – Committed to service. There is a strong and renewed focus on strengthening leadership and integrity across the APS. Identifying and developing leadership talent (page 82) Strong public sector leadership that has integrity, can navigate complexity and draw on diversity of opinion is critical to deliver the Australian Government’s reform agenda. It is also critical to strengthen the APS as an institution. This is particularly important as the APS responds to the findings of the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme. The APS will need to learn from the findings and systematically focus on identifying leaders capable of delivering for Government, with the right behaviours and approaches for the future, while developing leadership capability at all levels. Integrity (page 85) The work of the Australian Public Service affects all members of the Australian community. The APS can improve and maintain the trust of the community by acting with integrity and being accountable in the way it implements Australian Government policies and programs. The APS is expected to lead the way on respectful and ethical workplaces. Ethics Advisory Service (page 93) The APSC’s Ethics Advisory Service provides information, policy advice and guidance to APS employees at all levels on the application of the APS Values and the Code of Conduct to promote ethical decision-making across the public service. In 2022–23, the Ethics Advisory Service received 400 enquiries – 137 from individual APS employees, and 139 from agency human resources areas and managers. The remaining 124 enquiries were from former employees, were anonymous, or out of scope. Code of Conduct (page 172) In the 2023 Australian Public Service Agency Survey, agencies reported that 555 employees were the subject of an investigation into a suspected breach of the APS Code of Conduct that was finalised in 2022–23. Table A2.1 [of the report] presents the number of APS employees investigated by agencies for suspected breaches of individual elements of the APS Code of Conduct and the number of breach findings in 2022–23. One employee can be investigated for multiple elements of the Code of Conduct of the Public Service Act 1999. |

Secretaries Board

1.72 As outlined in Table A4.1 of the State of the Service Report 2022–23, the Commissioner is the Deputy Chair of the Secretaries Board. Appendix 4 of the State of the Service Report 2022–23 reported on the board and its subcommittees. The report stated that:

Established under the Public Service Act 1999, the Secretaries Board is responsible for stewardship of the Australian Public Service, including:

- identifying strategic priorities and issues that affect the APS

- developing and implementing strategies to improve the APS

- drawing together advice from senior leaders in government, business and the community.

The Secretaries Board achieves this while working collaboratively and modelling leadership behaviours.118

1.73 The State of the Service Report 2022–23 reproduced a ‘Secretaries Charter of Leadership Behaviours’ (charter) that was released in August 2022.119 The charter stated the following about its purpose.

The Charter of Leadership Behaviours sets out the behaviours that we, as Secretaries, expect of ourselves and our SES, and want to see in leaders at all levels of the APS.

The Charter focuses on behaviours that support modern systems leadership within the construct of the APS Values and Code of Conduct.

We encourage all APS leaders to consider how you can live up to these behaviours, where relevant to your role.120

1.74 The charter stated that the expected leadership behaviours were: ‘be Dynamic’, ‘be Respectful’, ‘have Integrity’, ‘Value others’, and ‘Empower people’ (‘DRIVE’). In respect to integrity, the charter stated the following.

have Integrity

Be open, honest and accountable

Take responsibility for what happens around you

Have courage to call out unacceptable behaviour121 [emphasis in original]

1.75 The State of the Service Report 2021–22 had also included a leadership capabilities model. That report stated that:

The APSC has strengthened the capability of public servants to model, champion and advance institutional integrity through a new leadership capabilities model, endorsed by the Secretaries Talent Council and Deputy Secretaries Talent Council: VICEED.122

1.76 The State of the Service Report 2021–22 stated that the ‘VICEED Leadership Capabilities Model’ had six leadership capabilities: ‘Visionary’, ‘Influential’, ‘Collaborative’, ‘Delivers’, ‘Enabling’ and ‘Entrepreneurial’ (‘VICEED’). The model also included the statement that a leader ‘Models, champions and advances institutional integrity’.123 The State of the Service Report 2021–22 was released in November 2022. In addition to setting out ‘VICEED’, it included a section on the charter (‘DRIVE’) released in August 2022.124 The report did not explain the relationship between ‘VICEED’ and ‘DRIVE’.

1.77 Appendix 4 of the State of the Service Report 2022–23 reported that during the reporting period (1 July 2022 to 30 June 2023) there had been a change of personnel for seven of the 18 positions125 on the Secretaries Board.126 This represents 39 per cent turnover on the Secretaries Board. ANAO analysis indicates the following.

- From 1 July 2022 to 31 December 2023, there had been a change of personnel for 12 of the 18 positions on the Secretaries Board (67 per cent turnover).127

- From 1 July 2022 to 31 December 2023, for the 16 Australian Government departments, 11 of the 16 secretary positions had a change of personnel (69 per cent turnover).128

Integrity maturity guidance

1.78 In April 2022 the APSC released a non-mandatory Integrity Metrics Resource directed to APS agencies. It was intended to assist agencies to measure, monitor and report on their integrity performance. The resource was intended to support agencies to understand their current integrity measurement capability and make informed decisions on where to focus future effort to lift integrity measurement, monitoring and reporting. The APSC stated that it was considered good practice for agencies to undertake this activity at regular intervals.129

1.79 In December 2022 the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI) released a Commonwealth Integrity Maturity Framework to support the design, implementation and review of the effectiveness of integrity frameworks in Commonwealth entities.130 The framework was launched in anticipation of the National Anti-Corruption Commission’s (NACC) establishment and was subsequently placed on the NACC website.131 ACLEI was subsumed by the NACC from 1 July 2023. The NACC has stated that the project has drawn from the APSC’s Integrity Metrics Maturity Model. Entities decide how to use the integrity maturity resources.

1.80 The November 2023 APS Integrity Action Plan stated that:

Integrity maturity self-assessments not only embed a culture of continuous improvement but also start an important cultural conversation about what integrity means to each agency and its staff.132

1.81 The APS Integrity Action Plan also stated that secretaries would ‘upscale integrity maturity across the Commonwealth’ by: undertaking an agency self-assessment against the Commonwealth Integrity Maturity Framework and reporting back to the Secretaries Board by September 2024 on plans to upscale their agency’s integrity maturity; support agency heads within their portfolios to do the same; and circulating the Integrity Good Practice Guide released with the APS Integrity Action Plan.133

National Anti-Corruption Commission

1.82 The NACC commenced on 1 July 2023. It is established under the National Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2022 to investigate allegations of serious or systemic corrupt conduct within the Commonwealth public sector, including conduct that occurred before it was established.134 The NACC reports publicly on the number of referrals it has received and the number of investigations it has opened.135

1.83 The NACC also has a mandate to educate the public service and the public about corruption risks and prevention.136 As discussed in paragraph 1.79, the NACC has adopted the Commonwealth Integrity Maturity Framework as part of its work in this regard.

Parliamentary inquiries and previous audits

1.84 On 27 June 2023, the Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) adopted an inquiry into probity and ethics in the Australian Public Sector, ‘with a view to examining whether there are systemic factors contributing to poor ethical behaviour in government agencies, and identifying opportunities to strengthen government integrity and accountability’.137 The JCPAA indicated that the inquiry would have particular regard to any matters contained in or connected to five Auditor-General reports.138 The inquiry followed recent JCPAA inquiries that had reviewed entities’ grants administration and procurement, including issues relating to probity, compliance with whole-of-government frameworks, and the role of framework owners.139 As part of its grants and procurement inquiries, the JCPAA considered findings in relevant ANAO performance audit reports, and ANAO submissions to the committee.

1.85 The ANAO’s submission to the JCPAA inquiry into probity and ethics identified performance audits which had made findings relating to probity, ethics and integrity. It also included commentary on areas where audit evidence indicated that the public sector regularly falls short of expectations set out in its regulatory frameworks. These areas are procurement, grants administration, record keeping, performance measurement and reporting, and accountability for performance.140

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.86 The Australian Parliament has provided, in the PS Act, that all members of the APS are subject to the integrity, probity and ethical obligations specified in the Act. The Parliament has also provided that one of the three broad functions of the Commissioner under the Act is ‘to uphold high standards of integrity and conduct in the APS’.141 The function of upholding APS integrity standards occurs in a changing and often dynamic operating environment, which in recent years has featured the following.

- Reviews, initiatives and investigations which have often focused on perceived shortcomings in upholding APS integrity, probity and ethics, including at the highest levels of APS leadership and the Secretaries Board.

- Australian Government statements that the Royal Commission Robodebt Scheme identified ‘serious failings within the Australian Public Service’.142 The APSC has stated that ‘Rebuilding trust in the APS is a priority’143 and that this process includes ‘reinforcing a culture with integrity at its core’.144

- Leadership change at the top of the APS, with 69 per cent turnover of departmental secretaries between July 2022 and December 2023.145

- Growth in APS employment. The APSC reported in March 2024 that at 31 December 2023 the APS headcount was 177,442, a 9.9 per cent increase since December 2022.146

- Establishment of the National Anti-Corruption Commission to: detect, investigate and report on serious or systemic corruption in the Commonwealth public sector; and educate the sector and the public about corruption risks and prevention.147

1.87 There is ongoing parliamentary interest in APS integrity, probity and ethics, including by the JCPAA, which in June 2023 adopted an Inquiry into probity and ethics in the Australian Public Sector. This audit provides independent assurance and reporting to the Parliament on the APSC’s administration of statutory functions relating to upholding high standards of integrity and ethical conduct in the APS.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.88 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the APSC’s administration of statutory functions relating to upholding high standards of integrity and ethical conduct in the APS.

1.89 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Has the APSC effectively promoted the APS Values and Code of Conduct?

- Has the APSC effectively monitored and evaluated agencies’ implementation of the APS Values and Code of Conduct?

- Has the APSC effectively contributed to stewardship of the APS?

1.90 The ANAO reviewed the APSC’s administration for the period July 2022 to December 2023.

Audit methodology

1.91 The audit procedures included: reviewing APSC records; and meetings with the Commissioner, APSC officials and relevant non-APSC officials.

1.92 The ANAO’s review focused on the following functions of the Commissioner set out in the PS Act.

- Promote the APS values — pursuant to paragraph 41(2)(e).

- Promote the APS Code of Conduct — pursuant to paragraph 41(2)(e).

- Provide advice and assistance to APS agencies on public service matters — pursuant to paragraph 41(2)(h).

- Evaluate the extent to which agencies incorporate and uphold the APS values — pursuant to paragraph 41(2)(f).

- Evaluate the adequacy of systems and procedures in agencies for ensuring compliance with the Code of Conduct — pursuant to paragraph 41(2)(l).