Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Australian Defence Force's Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Replacement (Land 121 Phase 3B)

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s management of the acquisition of medium and heavy vehicles, associated modules and trailers for the Australian Defence Force.

Summary

Introduction

1. Project Overlander Land 121 is a multi-phased project to provide the Australian Defence Force (ADF) with new field vehicles and trailers to enhance ground mobility. Phase 3B1 of the project is to acquire medium and heavy trucks, modules and trailers, at a budgeted cost of $3.386 billion. The vehicles are a core element of ADF capability, and essential for the conduct of operations. They will be used for the movement of Army troops, assets and supplies in combat theatres, humanitarian operations, natural disaster relief, general peacetime operations and training.

2. Land 121 Phase 3 received government first-pass2 approval in June 2004. At the time, the Department of Defence (Defence) considered that the medium and heavy vehicle acquisition was a relatively low risk military off-the-shelf (MOTS) procurement. Defence originally released a Request for Tender (RFT) for the medium and heavy vehicle segment in December 2005, but decided to retender in December 2008, due to concerns over the selected vehicles. Key milestones for the acquisition included:

- in August 2007, Defence received government second-pass approval to enter negotiations with Stewart and Stevenson3 as the supplier for the Phase 3B vehicles and modules, and with Haulmark Trailers for the Phase 3B trailers;

- in August 2008, Defence withdrew from negotiations with Stewart and Stevenson, citing technical and probity issues, and a tender resubmission process was initiated;

- in April 2011, Defence endorsed Rheinmetall MAN Military Vehicles–Australia (RMMV-A) as the preferred supplier for the vehicles and modules, and Haulmark Trailers was confirmed as the preferred supplier for the provision of trailers; and

- in July 2013, Land 121 Phase 3B received a revised government second-pass approval and Defence entered into contracts with RMMV-A and Haulmark Trailers.

3. Defence is acquiring 2536 medium and heavy trucks, and 2999 modules, from RMMV-A; and 1582 trailers from Haulmark Trailers.4 The capability will comprise a variety of vehicles including semi-trailers, recovery trucks, hook lift trucks and flatbeds in both protected and unprotected configurations. Figure S.1 shows the RMMV-A heavy Integrated Load Handling System vehicle, which is replacing the Mack series of vehicles currently in-service.

Figure S.1: RMMV-A heavy Integrated Load Handling System vehicle

Source: Department of Defence.

4. The Chief of Army is the Capability Manager5 for the medium and heavy vehicle fleet, and Defence’s Capability Development Group developed the capability proposals for the acquisition of the new fleet. The Defence Materiel Organisation’s (DMO’s) Land Systems Division has managed the medium and heavy vehicle fleet procurement processes, and has been responsible for the ongoing acquisition and the sustainment of the fleet.6

Audit objective and scope

5. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s management of the acquisition of medium and heavy vehicles, associated modules and trailers for the Australian Defence Force. The audit focused on the acquisition of the medium and heavy vehicle fleet from first-pass approval in 2004 through to early 2015.

6. The high-level criteria developed to assist in evaluating Defence’s performance were:

- requirements definition, acquisition strategies and plans, and capability development processes met Defence policy and procedures;

- procurement processes complied with the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) and Regulations7, and other relevant Commonwealth and Defence procurement requirements; and

- the acquisition has progressed to the expectations of the Commonwealth in terms of cost, schedule and delivery of required capability.

Overall conclusion

7. Defence’s Project Land 121 Phase 3B is to acquire 2536 medium and heavy trucks, 2999 modules and 1582 trailers for the ADF, at a cost of some $3.4 billion. The new medium and heavy vehicle and trailer fleet will replace the ADF’s aged in-service fleet, which includes certain vehicles acquired in the early 1980s. The vehicle and trailer fleet supports a wide range of ADF operations, and Defence aims to enhance ground mobility through the acquisition of modern vehicles and trailers. Defence contracted with Rheinmetall MAN Military Vehicles-Australia (RMMV-A) and Haulmark Trailers (Australia) to supply the vehicles, modules and trailers in July 2013—over nine years after first-pass approval8 was granted in 2004. As part of the acquisition process, Defence conducted an initial tender process in 2005–07 and a tender resubmission process in 2008–11.

8. Defence’s initial tender process to acquire a replacement medium and heavy vehicle fleet was flawed, resulting in a failed tender and a second approach to market, which contributed to long delays in the acquisition of a modern medium and heavy vehicle capability for the ADF. Defence conducted a more effective tender resubmission process from 2008, but the process was protracted and Defence did not enter into contracts to supply the replacement fleet until July 2013. The aborted initial tender process and the time taken to finalise the tender resubmission process have delayed the scheduled achievement of Final Operational Capability by seven years to 2023. In the intervening period, Defence will continue to rely on an aged fleet of medium and heavy vehicles that is increasingly costly to operate, maintain and repair.

9. Defence originally considered that the medium and heavy vehicle acquisition was a relatively low risk military off-the-shelf procurement. The difficulties subsequently experienced by Defence in acquiring a new medium and heavy vehicle fleet can mostly be attributed to shortcomings in its initial tender process between 2005 and 2007. Defence did not conduct any preliminary test and evaluation of vehicles before recommending a single supplier to the then Government. In selecting a preferred supplier, Defence also did not have sufficient regard to all relevant costs and benefits identified in its tender evaluation process, so as to adhere to the Government’s core principle of value for money.9 Defence’s 2007 Source Evaluation Report initially ranked a proposal from Stewart and Stevenson last of five tenders on the basis of value-for-money, but elevated the proposal to the position of preferred tender because it was the most affordable—notwithstanding Defence’s assessment of significant vehicle deficiencies against its specific requirements, and the identification of many acquisition risks in the course of the tender process.10

10. Further, Defence did not advise Ministers of the significant capability and technical risks it had identified, before recommending a single supplier. Defence confirmed the previously identified shortcomings through test and evaluation after the acquisition entered an Offer Definition and Refinement Process, and the preferred supplier’s vehicles were tested. Defence subsequently cancelled contract negotiations with the preferred supplier.

11. In December 2008, Defence again approached the market and implemented a more robust tender process, drawing on key lessons learned from the initial tender process. Defence conducted preliminary test and evaluation of vehicles supplied by five companies, before shortlisting three suppliers and asking them to submit tenders. In April 2011, Defence selected RMMV-A as its preferred vehicle supplier on the basis of value-for-money. However, the protracted Offer Definition and Refinement Process with RMMV-A required escalation to senior leaders and, as a consequence, Defence was not in a position to approach the then Government for second-pass approval11 until July 2013.

12. In addition to shortcomings in the initial tender process, Defence has not applied a rigorous approach to capability definition throughout the acquisition of the medium and heavy vehicle fleet. Defence did not complete or update its mandated Capability Definition Documents for the initial and revised government second-pass approvals in 2007 and 2013, or when negotiating and entering into contractual arrangements. Defence also developed a variety of non-standard documents to compensate for the absence of updated Capability Definition Documents; an approach which unnecessarily added to procurement risk.12 In addition, Defence applied different methodologies over time to determine the acquisition’s Basis of Provisioning, a process intended to measure the number of each vehicle type required by Army to meet its capability objectives. Further, Defence’s Basis of Provisioning for the medium and heavy vehicle fleet has been amended on many occasions during the acquisition process to reflect the number of vehicles Defence could afford, rather than the number of vehicles it required to deliver the defined capability—a pragmatic approach which did not align with the key purpose of the Basis of Provisioning process. In the light of this experience, Defence should review its 1999 Instruction to provide contemporary guidance on the Basis of Provisioning for the acquisition of specialist military equipment for the ADF.

13. Defence advised the ANAO that as at March 2015, total expenditure on the medium and heavy vehicle fleet acquisition was $112 million, with most expenditure to be incurred from mid-2016 when truck production commences.13 Defence further advised that there was sufficient budget remaining for the project to complete against its agreed scope, and the project had not applied any contingency funding to date. Under applicable budgeting arrangements, Defence is able to use approved funding later in the project, if it is not spent at the time initially anticipated due to project delays.

14. Defence remains confident that it will meet the acquisition’s current critical milestones, the first being the commencement of Introduction Into Service Training in September 2016. Key issues that have affected the project since contract signature include: delays experienced by RMMV-A in engaging sub-contractors to develop modules; and a range of systems integration issues. The ANAO has previously observed that cost and schedule risks tend to rise when acquisition programs approach the complex stage of systems integration14, and Defence will need to maintain a focus on managing the remaining integration issues. Defence has worked with RMMV-A to manage the vehicle production schedule and production of the initial test vehicles commenced in April 2015.

15. The overall project delay of seven years has obliged Defence to continue to operate its in-service fleet of vehicles, delivered between 1982 and 2003. The current fleet is becoming increasingly unreliable and costly to maintain, and Defence has sought to achieve savings by disposing of uneconomical vehicles. While Defence currently expects to deliver the project within budget, the audit illustrates the impact of protracted procurement and approval processes on both Defence and industry suppliers.15

16. Against a background of other major Land Systems acquisitions approaching key milestones16, this audit underlines the benefits of early test and evaluation of prospective vehicles, which strengthen Defence’s ability to identify and mitigate risks, and provide informed advice for decision-making on a preferred supplier. Further, having commenced a tender process, Defence needs to keep in view the Government’s core rule of achieving value-for-money, which continues to require consideration of relevant financial and non-financial costs and benefits of each proposal.17

17. The ANAO has made one recommendation focusing on the development of contemporary guidance on the Basis of Provisioning for the acquisition of Australian Defence Force specialist equipment, to provide greater certainty to Defence’s assessments and advice on the type and quantity of materiel required to deliver a defined capability. Defence agreed to the recommendation.

Key findings by chapter

Defining Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Capability Requirements (Chapter 2)

18. The primary Defence Capability Definition Documents are: Operational Concept Documents18, Function and Performance Specifications19, and Test Concept Documents.20 These documents form part of the second-pass capability proposal to government; and provide the basis for testing and evaluating whether a delivered capability meets operational requirements. In consequence, the documents need to accurately reflect the user’s expectations of the system.21 As the largest Land Systems acquisition in decades and a core element of the ADF’s land and peacetime operations capability, the acquisition of a new medium and heavy vehicle fleet required a capability definition process that reflected its importance and cost.

19. Defence developed Capability Definition Documents during the initial stages of the medium and heavy vehicle fleet acquisition process between 2004 and 2007, but did not complete or update them for the purpose of supporting government second-pass approval processes in 2007 and 2013, or when negotiating and entering into contracts in 2013. Defence instead developed a set of non-standard documents to inform contracts, design review processes and test and evaluation, contrary to Defence policy.22 In May 2014, a DMO Gate Review Board23 observed that Defence’s approach to developing Capability Development Documents for Land 121 Phase 3B could lead to risks down the track, particularly as staff rotate through the areas of Defence responsible for the acquisition. Defence’s approach in this instance has also contributed to uncertainty for industry contractors in developing solutions, particularly for elements of the design that remain subject to change, and in relation to systems integration.

20. The Basis of Provisioning is a process for determining and recording the quantity of an asset that Army is required to hold in order to support preparedness and mobilisation objectives.24 Adjustments to the Basis of Provisioning would normally be made to reflect a change in the capability requirements of Army, or a change in the capability characteristics of an asset. The difference between the number of assets listed in the Basis of Provisioning required to meet Army’s capability requirements, and Army’s actual number of assets, is the capability gap. In this respect, the Basis of Provisioning is expected to be an ‘objective’ measure of capability requirements, rather than a statement of the assets which can be acquired within an available budget.

21. While some adjustment can be expected as a result of tender and contract negotiation activities, the Basis of Provisioning for Land 121 Phase 3B has undergone numerous changes since 2004: in terms of the number and type of vehicles required; vehicle characteristics such as blast and ballistic protection; and module and trailer requirements. Defence applied different methodologies over time to develop the Basis of Provisioning, and more fundamentally, made significant adjustments to required vehicle numbers and types based on the availability of project funding—a pragmatic approach which did not align with the key purpose of the Basis of Provisioning process. Defence needs to maintain a clear view of any gap between the capability it requires to support preparedness and mobilisation objectives, and the affordable capability. However, the current Defence Instruction (Army) on the Basis of Provisioning for Army capabilities was issued in 1999 and has not been updated. To provide greater certainty in the development of relevant Defence assessments and advice, Defence should develop contemporary guidance on how to calculate and maintain the Basis of Provisioning for specialist military equipment.

Initial Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Tender Process (Chapter 3)

22. Defence released a Request for Tender (RFT) for the medium and heavy vehicle segment of Land 121 Phase 3 in December 2005.25 Five vehicle suppliers responded to the RFT. However, Defence’s Acquisition Strategy did not allow for any practical preliminary testing and evaluation of the vehicles proposed by the tenderers. Instead, Defence’s assessment of the vehicles was limited to reviewing specifications provided by the tenderers.

23. Defence’s August 2007 Source Evaluation Report initially ranked the tender response from Stewart and Stevenson last of the five tenders on the basis of value-for-money, and noted that the proposal exposed the Commonwealth to very high risk, including schedule risk, cost risk, quality and performance risk. Despite this assessment, Defence elevated the Stewart and Stevenson proposal to the position of preferred tenderer on the basis that it was the most affordable. Defence’s decision exposed the Commonwealth to the potential acquisition of a fleet of vehicles assessed as failing to meet both key capability and technical requirements, introducing significant risk to the acquisition process. Defence also did not have sufficient regard to the 2005 Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines, then in operation, which established value-for-money as the core principle underpinning Australian Government procurement and made clear that this principle required an analysis of all relevant costs and benefits of each proposal, in addition to financial cost.

24. Defence’s Acquisition Strategy was to provide the then Government with a shortlist of two preferred suppliers for second-pass approval, and to subsequently conduct an Offer Definition and Refinement Process (ODRP) to determine the most suitable supplier. However, at the second-pass approval stage in August 2007, Defence diverted from its Acquisition Strategy and recommended that only one medium and heavy vehicle supplier (Stewart and Stevenson) proceed to the ODRP.26 This revised approach was adopted notwithstanding that Defence had not at that stage conducted any preliminary on or off-road vehicle testing.27 Further, Defence did not advise the Government about the assessed risks, mentioned above in paragraph 23, relating to the preferred proposal.

25. As the acquisition entered the ODRP phase, Defence identified two key issues which eventually led to: the cancellation of negotiations with Stewart and Stevenson; and a tender resubmission process for the medium and heavy vehicle fleet. The first issue related to whether Stewart and Stevenson would be able to satisfy government requirements for a mixed fleet of military off-the-shelf (MOTS) and commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) vehicles. While Defence had expected the then Government to approve procurement of a MOTS fleet, the Government decided in August 2007 to procure a mixture of MOTS and COTS vehicles, necessitating a change in the Basis of Provisioning.28 This meant that the information on the required number and type of vehicles, provided to suppliers when the tender was released in December 2005, was no longer current. Concerns subsequently emerged within Defence that Stewart and Stevenson may not be able to satisfy the new requirements of the Basis of Provisioning because the company did not make MOTS prime mover variants, now under consideration. A second key issue related to deficiencies in the detailed vehicle specifications provided by Stewart and Stevenson in November 2007, as compared to data provided for the tender evaluation process.29,30

26. In February 2008, DMO proceeded to demonstration and compliance testing of the Stewart and Stevenson MOTS vehicles. The testing confirmed significant deficiencies in the vehicle’s capability against Defence requirements, and inconsistencies between the test vehicle dimensions and specifications, compared to those originally documented in the tender response. After seeking advice from the Defence probity adviser, Defence cancelled negotiations with Stewart and Stevenson in May 2008.

Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Tender Resubmission (Chapter 4)

27. After withdrawing from negotiations with Stewart and Stevenson in May 2008, Defence obtained government approval in July 2008 to return to the market for revised offers for the medium and heavy vehicle fleet. Defence recognised the shortcomings in its first (2005–2007) tender process, and decided to conduct preliminary testing of vehicles, before inviting a shortlist of suppliers to submit tenders.

28. The first stage of the tender resubmission process involved comparative evaluation testing of prospective vehicles by the Australian Defence Test and Evaluation Office (ADTEO) in 2009.31 The preliminary testing included a technical evaluation against requirements, driver training and on/off-road testing. The ADTEO testing eliminated vehicles from the tender resubmission process that did not meet Defence’s capability needs, including those proposed by Stewart and Stevenson. Vehicles submitted by RMMV-A, Mercedes-Benz and Thales proceeded to the second stage of the process.

29. In May 2010, Defence released an RFT to the shortlisted vehicle suppliers. Each of the firms provided a response by the due date in August 2010, and Defence evaluated the responses to determine the most competitive tender representing the best value-for-money. RMMV-A was ranked first or second against all of the selection criteria, including capability, support and schedule, and overall risk. Selecting RMMV-A also offered the Commonwealth the highest number of vehicles and modules within budget constraints. Defence’s Source Evaluation Report concluded that RMMV-A was Defence’s preferred capability solution.

30. Defence received interim-pass approval32 from the then Government in December 2011 to commence an Offer Definition and Refinement Process (ODRP) with RMMV-A. As part of the ODRP, Defence was expected to address several compliance issues arising from RMMV-A’s tender before obtaining second-pass approval. Overall, the quality of Defence’s advice to Ministers at interim-pass was an improvement on the advice provided for the initial second-pass process in 2007. Defence provided a more thorough justification for the selection of its preferred tenderer, RMMV-A, and provided comparative information relating the RMMV-A proposal to those received from the other two tenderers. Further, Defence’s advice to Ministers was more soundly based, due largely to the vehicle testing undertaken by ADTEO during 2009.

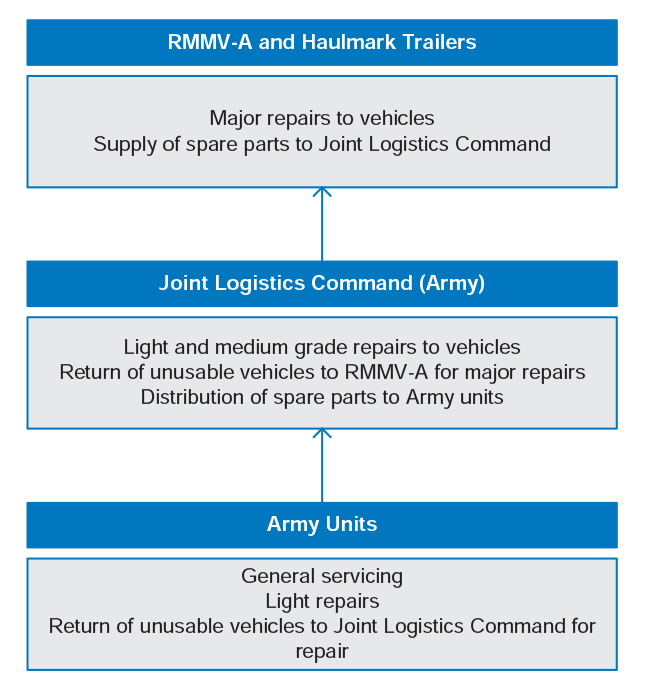

31. The ODRP discussions with RMMV-A became protracted during 2012, and culminated in a February 2013 meeting between the CEOs of DMO and RMMV-A’s parent company33 to address outstanding issues. The negotiations between Defence and RMMV-A concluded in March 2013, some 14 months after the commencement of the ODRP. Defence subsequently received second-pass approval from Ministers in July 2013 to acquire the medium and heavy vehicles from RMMV-A, and Haulmark Trailers was again confirmed as the trailer supplier. Defence signed contracts with RMMV-A and Haulmark Trailers in July 2013, and entered into a strategic agreement with the two suppliers for the possible further delivery of vehicles and trailers under Phase 5B of LAND 121—however, no guarantees relating to the supply of vehicles and trailers under Phase 5B were provided to the suppliers under this agreement.

Acquisition Status and Sustainment (Chapter 5)

32. After finalising contracts with RMMV-A and Haulmark Trailers in July 2013, Defence and the two suppliers agreed on design review processes. By April 2015, Defence had conducted Preliminary Design Reviews for most of the vehicle and module variants, and two of the ten trailer variants. The design reviews considered two key acquisition risks: the interoperability of the vehicles, modules and trailers; and the integration of Command, Control, Communications, Computer and Intelligence (C4I) systems into the vehicles.34 Defence is responsible for ensuring the medium and heavy vehicles and trailers are interoperable with each other, and has established an Integrated Control Working Group to identify the information required by contractors for this purpose. RMMV-A has engaged a contractor to help resolve anticipated electromagnetic interference when the C4I systems are integrated with the medium and heavy vehicles.

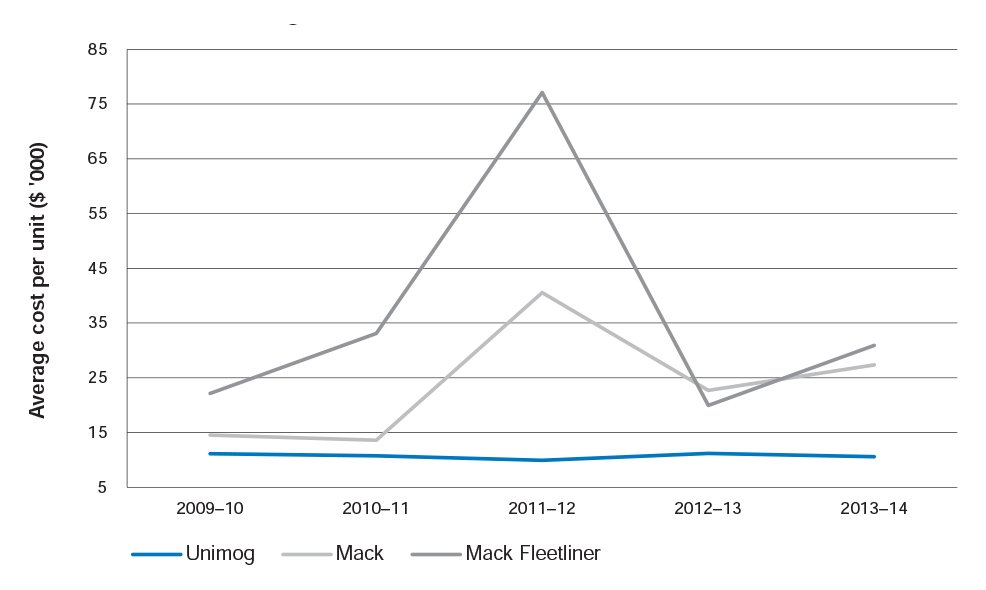

33. There has been an overall project delay of seven years. When Ministers first provided second-pass approval for the earlier acquisition proposal in 2007, the replacement medium and heavy fleet was scheduled to achieve Final Operational Capability in 2016. The aborted initial tender process and the need for a tender resubmission process have delayed the scheduled achievement of Final Operational Capability to 2023. The delays in the medium and heavy fleet acquisition have placed considerable pressure on the existing Unimog and Mack vehicle fleet, which has now well exceeded its life-of-type and is increasingly difficult and costly to maintain. Defence has reduced the overall size of the in-service fleet since 2010, by disposing of vehicles which were uneconomical to maintain; a process with attributed savings of $9.837 million since 2011–12. Despite removing uneconomical vehicles, the average sustainment cost per vehicle for the Mack fleet has increased by some 80 per cent between 2009–10 and 2013–14, reflecting the advanced age of the fleet and difficulty in acquiring spare parts. In 2013–14, the average cost of sustaining Unimog vehicles was $10 652; and $27 899 for Mack vehicles.35 Defence informed Ministers in July 2013 that the Mack fleet will have difficulty supporting some of Defence’s operational requirements from 2016, underlining the importance of delivering the new fleet as scheduled.

Summary of entities’ responses

34. The Department of Defence’s summary response is provided below. The trailer supplier, Haulmark Trailers (Australia) and the unsuccessful 2007 tenderer, BAE Systems Australia, also provided summary responses. RMMV-A elected not to provide a formal response for publication. Appendix One contains the full responses to the audit report.

Department of Defence

Defence welcomes the ANAO audit report on the Australian Defence Force’s Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Replacement (Land 121 Phase 3B). This report highlights the importance of acquiring the medium and heavy trucks, modules and trailers to replace the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) aging in-service fleet which is approaching life-of-type.

The report accurately highlights the challenges that Defence faced during the initial tender process in 2005-2007, which resulted in delays to the acquisition of a replacement capability. Defence acknowledged the issues and concerns around technical and probity issues, and subsequently in 2008-2013, conducted a more effective tender resubmission process.

More recently, Defence has ensured that operational concepts were clearly defined and communicated. Whilst there may be elements of the design which the contractors have yet to finalise, Defence is working with these contractors to deliver the capability to meet ADF requirements.

Whilst Defence agrees with the intent of the one recommendation, we reinforce that value for money is a key consideration during every tender process. Defence will review its policy on Basis of Provisioning to ensure it is current and applicable in the acquisition of specialist military equipment. The residual issues that ANAO have identified will be addressed when the capability development acquisition life cycle is redesigned as part of the First Principles Review implementation.

BAE Systems Australia (Stewart and Stevenson)

Stewart and Stevenson offered essentially its [United States of America] military of-the-shelf Family of Medium Tactical Vehicles (FMTV) models, unmodified in order to keep costs low. The FMTV vehicles are well characterised, and whose performance has been well documented and well known by the [United States of America] Army in its acquisition of over 70 000 FTMV vehicles before and since Project Overlander.

The [2005 Request for Tender] included a bespoke vehicle specification written by DMO which incorporated extensive use of Australian standards. The RFT specification required COTS/MOTS vehicles previously developed to international standards to have their manufacturer’s product specifications analysed for compliance to unique Australian standards.

Haulmark Trailers (Australia)

After reviewing the audit report excerpts, Haulmark Trailers (Australia) Pty Ltd has generally found them to be a fair and reasonable depiction of events over the period covered by the audit.

Haulmark also wishes to acknowledge that we were only provided with excerpts of the report that related to us and as such we could not comment on the report holistically.

Recommendation

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.32 |

To provide greater certainty in the development of relevant assessments and advice, the ANAO recommends that Defence develop contemporary guidance on the Basis of Provisioning for the acquisition of specialist military equipment for the Australian Defence Force. Defence response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter introduces Project Overlander Land 121 Phase 3B, which is acquiring medium and heavy field vehicles, modules and trailers for the Australian Defence Force. It also outlines the audit approach.

Project Overlander

1.1 Project Overlander Land 121 is a multi-phased project to provide the Australian Defence Force (ADF) with new field vehicles and trailers to enhance ground mobility. Phase 3B36 of the project is to acquire medium and heavy trucks, modules37 and trailers, at a budgeted cost of $3.386 billion. The vehicles are a core element of ADF capability, and essential for the conduct of operations. They will be used for the movement of Army troops, assets and supplies in combat theatres, humanitarian operations, natural disaster relief, general peacetime operations and training.

1.2 The Department of Defence (Defence) is acquiring 2536 medium and heavy trucks, and 2999 modules, from RMMV-A; and 1582 trailers from Haulmark Trailers.38 The capability will comprise a variety of vehicles including semi-trailers, recovery trucks, hook lift trucks and flatbeds in both protected and unprotected configurations. Figure 1.1 shows the RMMV-A medium weight truck being acquired under Land 121 Phase 3B.

1.3 The new medium and heavy vehicles will replace vehicles such as the Mercedes-Benz Unimog (Figure 1.2), Mack, and S-Liner trucks. The in-service vehicles and trailers were delivered to the ADF between 1967 and 2003, and their nominal life-of-type39 ended between 1982 and 2013. The fleet has experienced heavy operational use since 1999, and has been increasingly costly to maintain, repair and operate. The fleet also lacks protection and safety features common to contemporary military field vehicles.

Figure 1.1: Rheinmetall MAN medium weight truck

Source: Department of Defence.

Figure 1.2: Mercedes-Benz Unimog medium weight truck

Source: Department of Defence.

1.4 The major differences in vehicle capability between the in-service and replacement fleet are summarised in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Capability differences between the in-service and new vehicles

|

Legacy medium and heavy trucks |

New medium and heavy trucks |

|

Maximum payload of 4–10 tonnes |

Maximum payload of 5–16 tonnes |

|

No Integrated Load Handling System (ILHS) |

ILHS on most heavy vehicles |

|

No ballistic/blast protection |

All models will have ballistic/blast protected variants |

|

No C4IA systems |

All vehicles will be fitted for C4I systems |

|

No/limited weapons systems |

Some vehicles may be fitted for integrated weapons systems |

Source: Department of Defence documents.

Note A: Command, Control, Communications, Computer and Intelligence (C4I) systems are a key component to enable Network Centric Warfare.

1.5 Land 121 Phase 340 received government first-pass41 approval in June 2004. At the time, the Department of Defence (Defence) considered that the medium and heavy vehicle acquisition was a relatively low risk military off-the-shelf (MOTS) procurement. Defence originally released a Request for Tender (RFT) for the medium and heavy vehicle segment in December 2005, but decided to retender due to concerns over the selected vehicles. The history of the project is summarised in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Timeline for Land 121 Phase 3B

|

Year |

Month |

Activity |

|

2004 |

June |

Government first-pass approval. |

|

2005 |

December |

Defence released a Request for Tender (RFT) for the medium and heavy vehicle segment. |

|

2007 |

August |

Defence endorsed Stewart and StevensonA as the preferred supplier for the Phase 3B vehicles and modules, and Haulmark Trailers for the Phase 3B trailers. |

|

Government second-pass approval. |

||

|

2008 |

July |

The then Minister for Defence agreed to seek revised offers for the medium and heavy vehicle fleet. |

|

August |

Defence withdrew from negotiations with Stewart and Stevenson, citing technical and probity issues, and a two-stage tender resubmission process was initiated. |

|

|

December |

Stage 1 of the tender resubmission process was approved. The Conditions of Tender were amended and vehicle Comparative Evaluation Testing commenced to inform the down-selection of tenderers to proceed to Stage 2. |

|

|

2010 |

February |

The then Minister for Defence announced a down-selection of tenderers to proceed to Stage 2 of the tender resubmission process. |

|

May |

Stage 2 of the tender resubmission process commenced with the issue of an amended RFT to the down-selected tenderers (Mercedes-Benz, RMMV-A and Thales Australia). |

|

|

2011 |

April |

Defence endorsed RMMV-A as the preferred supplier for the vehicles and modules, and Haulmark Trailers was confirmed as the preferred supplier for the provision of trailers. |

|

December |

Government interim-passB approval. |

|

|

2012 |

June |

Defence and the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) signed the Materiel Acquisition Agreement for Land 121 Phase 3B. |

|

2013 |

July |

Revised second-pass approval from government. |

|

Defence signed a contract with RMMV-A for the provision of Phase 3B vehicles and modules, and a contract with Haulmark Trailers for the Phase 3B trailer component. |

||

|

2014 |

January–December |

Preliminary and Critical Design Reviews were held for some vehicles, modules and trailers. |

|

2015 |

February–May |

Further Critical Design Reviews for vehicles and modules. Acceptance, Verification and Validation activities for some trailers commenced at Monegeetta, Victoria.C |

Source: ANAO based on Department of Defence documents.

Note A: Stewart and Stevenson was acquired by BAE Systems on 31 July 2007.

Note B: More complex projects with high degrees of cost and/or capability risk or requiring significant financial commitment may return for interim-pass decisions between first and second-pass. This process enables the Government to make incremental decisions at key project milestones and for Defence to obtain direction from the Government.

Note C: Verification is a process for proving that the product design satisfies its immediate requirements. Validation involves ensuring that the implementation of the product aligns with the intended purpose.

1.6 When the then Government gave the initial second-pass approval in 2007, the replacement medium and heavy vehicle fleet was scheduled to achieve Final Operational Capability in 2016. However, by the time the project received a revised second-pass approval in 2013, Final Operational Capability was scheduled for 2023, some seven years later.42

Roles and responsibilities

1.7 The following areas of Defence have had responsibility for the medium and heavy vehicle and trailer fleet acquisition:

- Chief of Army is the Capability Manager for the vehicle and trailer fleet.43 Capability Managers are responsible for raising, training and sustaining capabilities agreed by the Government, through the coordination of the Fundamental Inputs to Capability.44

- DMO’s Land Systems Division has had responsibility for the acquisition and sustainment of in-service vehicle and trailer fleet.45

- Capability Development Group (CDG) developed the capability proposals for the acquisition of the vehicle and trailer fleet, taking into account strategic priorities, funding guidance, legislation and policy. CDG’s Australian Defence Test and Evaluation Organisation (ADTEO) conducted preliminary Test and Evaluation of vehicles, and is also supporting the conduct of Operational Test and Evaluation on behalf of Chief of Army to inform declaration of Operational Capability.

Previous reviews of the medium and heavy vehicle acquisition

1.8 The ANAO Major Projects Report has reviewed the status of the medium and heavy vehicle acquisition annually since 2009–10. In these reports, DMO has identified that the major risks and issues for the acquisition include:

- vehicle protection requirement changes resulting from operational lessons;

- the affordability of the capability within a capped budget process;

- the need to acquire and integrate a range of developmental modules;

- axle weight limits imposed by state and territory authorities, which have the potential to restrict how vehicles will be operated on public roads;

- overall vehicle weights of three vehicle/trailer combinations exceeding legislative limits when fully laden;

- changes to system specifications which may lead to contract change proposals;

- coordinating the efforts of two separate prime contractors (that is, for the vehicles and trailers) to deliver a complete mission system; and

- the integration of new command, control, communications, computer and intelligence (C4I) systems into the vehicles and modules.46

Commonwealth Procurement Framework

1.9 Until 30 June 2012, the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines (CPGs), issued by the Finance Minister under the Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997, established the core procurement policy framework and outlined the Government’s expectations for departments and agencies in relation to procurement. The CPGs formed part of the wider financial management framework established by the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) and focused on achieving value for money through the efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of public resources, and ensuring accountability and transparency in government procurement activities.

1.10 The 2005 CPGs were applicable47 in August 2007 at second-pass approval for the medium and heavy vehicle fleet acquisition, and the 2008 CPGs were applicable in December 2011 for the interim-pass approval following the tender resubmission process. Both the 2005 and 2008 CPGs provided that:

Value for money is the core principle underpinning Australian Government procurement. In a procurement process this principle requires a comparative analysis of all relevant costs and benefits of each proposal throughout the whole procurement cycle (whole-of-life costing).48

Mandatory Procurement Procedures (MPP)

1.11 Division 2 of the 2005 and 2008 CPGs referred to Mandatory Procurement Procedures (MPPs) which applied to procurements known as ‘covered procurements’. Division 2 also described the procurement methods available in government procurement and when to use those methods:

- Open Tendering—involved publishing an RFT and receiving all submissions delivered by the deadline;

- Select Tendering—involved issuing an invitation to tender to those potential suppliers selected from an existing multi-use list; a list of suppliers that responded to a request for expressions of interest; or suppliers that complied with an essential legal requirement or licensing arrangement; and

- Direct Sourcing—where an agency may invite potential suppliers of its choice to make submissions. Generally, direct sourcing was only allowed under specific circumstances or where it was the only practical alternative available to the agency.

Defence and DMO specific exemptions

1.12 While the MPPs were designed to encourage competition and, therefore, enhance value for money outcomes, Paragraph 2.7 of the 2008 CPGs49 provided a general exemption clause:

Nothing in any part of these CPGs prevents an agency from applying measures determined by their Chief Executive to be necessary: for the maintenance or restoration of international peace and security; to protect human health; for the protection of essential security interests; or to protect national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value. Applying such measures does not diminish the responsibility of Chief Executives under section 44 of the FMA Act to promote the efficient, effective and ethical use of Commonwealth resources.50

1.13 This exemption was, and continues to be used51 by Defence in the procurement of the majority of its military specific equipment, including the vehicles, modules and trailers to be acquired under Land 121 Phase 3B.

About the audit

1.14 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s management of the acquisition of medium and heavy vehicles, associated modules and trailers for the Australian Defence Force.

1.15 The high-level criteria developed to assist in evaluating Defence’s performance were:

- requirements definition, acquisition strategies and plans, and capability development processes met Defence policy and procedures;

- procurement processes complied with the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) and Regulations52, and other relevant Commonwealth and Defence procurement requirements; and

- the acquisition has progressed to the expectations of the Commonwealth in terms of cost, schedule and delivery of required capability.

1.16 The audit focused on the acquisition of the medium and heavy vehicle fleet from prior to government first-pass approval in 2004 through to early 2015. The ANAO examined Defence’s requirements definition; planning and budgeting; procurement processes including industry solicitation; advice to government; project management; and project performance in terms of cost, schedule and capability.

1.17 The ANAO examined a broad range of documentation pertaining to the medium and heavy vehicle acquisition, including planning documents, tender documents, contracts, ministerial advice, and acquisition progress reports. The ANAO also held discussions with the two major contractors involved in the acquisition: RMMV-A and Haulmark Trailers.

1.18 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at an approximate cost to the ANAO of $543 720.

Report structure

1.19 The remainder of the report is structured as follows:

Table 1.3: Chapter structure of the report

|

2. Defining Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Capability Requirements |

|

Examines the capability definition processes undertaken by Defence for the acquisition of the medium and heavy vehicle fleet. |

|

3. Initial Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Tender Process |

|

Examines the initial medium and heavy vehicle fleet tender process conducted between 2005 and 2007, including industry solicitation, the tender evaluation and advice to government. |

|

4. Medium and Heavy Vehicle fleet Tender Resubmission |

|

Examines the medium and heavy vehicle fleet tender resubmission process conducted in 2008, including industry solicitation, the tender evaluation and advice to government. |

|

5. Acquisition Status and Sustainment |

|

Examines the status of the medium and heavy vehicle fleet acquisition. It also examines the availability and sustainment of the in-service medium and heavy vehicle fleet. |

2. Defining Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Capability Requirements

This chapter examines the capability definition processes undertaken by Defence for the acquisition of the medium and heavy vehicle fleet.

Introduction

2.1 Defence’s acquisition of a new medium and heavy vehicle and trailer fleet commenced as early as 2001 and was ongoing in mid-2015. During this period, there has been significant reform in Defence’s approach to capability development. The implementation of defined systems engineering processes has been central to the reform process, involving capability requirements definition, system design reviews, progressive test and evaluation, and verification of compliance with specified requirements.

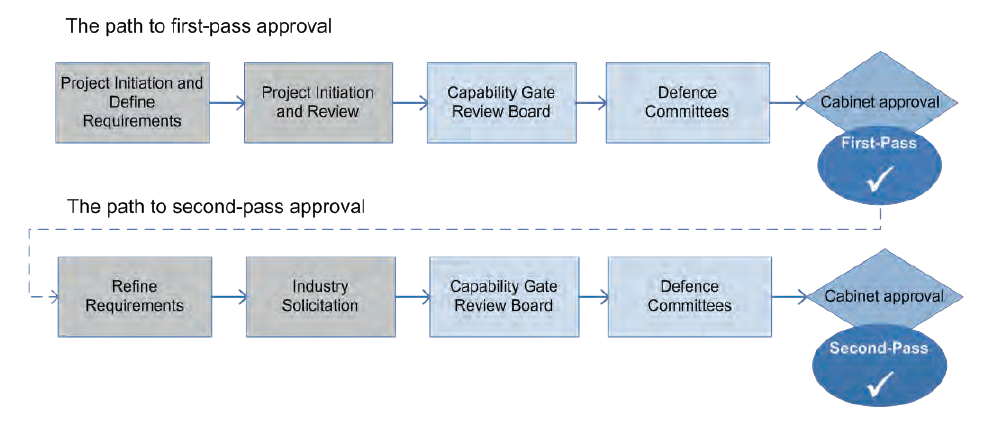

2.2 Capability definition processes operate within the two-pass approval framework for major Defence acquisition projects (illustrated in Figure 2.1). The primary objective of two-pass approval is to give the Australian Government visibility of, and control over, capability development with sufficient information, and in good time, so that it can make informed and deliberate decisions on each project.53 At the first-pass stage, the Government is provided with potential options to address a capability gap and approval is sought to develop specific options. The second-pass stage is intended to provide Ministers with the necessary information to select both an acquisition and a through-life support option.

Figure 2.1: Two-pass approval process

Source: ANAO based on Department of Defence guidance.

2.3 Defence acquisitions subject to the two-pass approval process have been examined in several ANAO audits and other external reviews.54 A common theme of these audits and reviews has been that inadequate capability requirements definition can have significant consequences in terms of project cost, schedule, and delivery of the intended capability.

2.4 In this chapter, the ANAO examines:

- the composition of the ADF’s in-service medium and heavy vehicle and trailer fleet;

- the development of Capability Definition Documents for the medium and heavy vehicle and trailer fleet acquisition;

- the vehicle and trailer capability proposed by Defence; and

- the calculation of the number and type of vehicles, modules and trailers required by Defence, referred to as the Basis of Provisioning.

In-service medium and heavy vehicle fleet

2.5 The medium and heavy vehicle and trailer fleet is the backbone of the ADF’s land warfighting support, sustainment, deployment and redeployment structure. The fleet is used to transport personnel, combat supplies, materiel and replacement combat systems, and to evacuate casualties. The vehicles also serve as platforms and prime movers for weapon systems and Command, Control, Communications, Computer and Intelligence (C4I) systems.

2.6 At first-pass approval in June 2004, the in-service fleet consisted of vehicles from seven manufacturers, and included 78 vehicle variants and 27 trailer variants. Defence advised the then Government that the fleet’s diversity imposed a major support burden, and resulted in complex training requirements and associated costs. Defence also advised the Government that the in-service fleet was costly to maintain, difficult to repair and operate, and presented safety risks due to the age of the vehicles. Table 2.1 lists the delivery dates for vehicles and trailers in the in-service fleet, and their nominal life-of-type.55

Table 2.1: In-service medium and heavy vehicle fleet

|

Vehicle type |

Delivery date |

Nominal life-of-type |

|

Mack R series 6x6 |

1982–1986 |

1997–2001 |

|

Mercedes-Benz Unimog |

1982–1991 |

1997–2006 |

|

International S-Line |

1987–1989 |

1997–1999 |

|

Mack CH Fleetliner |

1999–2000 |

2009–2010 |

|

Scania P114 CB |

2002–2003 |

2012–2013 |

|

Medium Trailer |

1967–1989 |

1982–2004 |

|

Heavy Trailer |

1968–1988 |

1998–2008 |

Source: Department of Defence.

2.7 The medium and heavy vehicles and trailers have experienced heavy operational use since 1999, and delays in replacing the fleet have led to increasing maintenance costs.56

Capability definition process

Key documents

2.8 Since 2002, Defence has provided guidance on capability requirements definition through a number of handbooks and manuals, with new measures added over time to strengthen the process. Defence guidance has been reinforced by a series of Defence Instructions, which include formal requirements applying to Defence personnel involved in ADF capability development. Under the capability definition framework, the primary ADF Capability Definition Documents are:

- Operational Concept Documents, which are intended to inform system acquirers and developers of the ADF’s operational requirements;

- Function and Performance Specifications, which define ADF requirements of the system in terms of system functions, and how well those functions are to be performed57; and

- Test Concept Documents, which provide an outline of the test strategy to be used to verify and validate that the design and operational requirements of the capability have been complied with.58

2.9 These documents are developed during a project’s requirements definition phase by Capability Development Group (CDG)59, and form part of the supporting documentation for the second-pass capability proposal to Ministers. The documents need to accurately reflect the user’s expectations of the system. Requests for Tenders containing deficient Capability Definition Documents will most likely result in tender evaluation teams evaluating tenders against incomplete specifications, which heightens the risk that the major system being acquired and its associated support system will not meet ADF requirements. The Capability Definition Documents are also the key documents used to measure the effectiveness of the capability at the test and evaluation stage of a procurement.

2.10 Typically, the successful contractor will develop System Specifications that describe how their particular system design will implement the functional requirements in the Function and Performance Specifications.60,61 These System Specifications are then reviewed and signed-off by Defence, and become part of the contract.62

Development of Capability Definition Documents

2.11 Defence began development of the Capability Definition Documents for the medium and heavy vehicle and trailer fleet acquisition as early as 2001. However, development of the Operational Concept Document stopped in 2005, following its release as part of the 2005 Request for Tender (RFT) process. It was not updated for the initial government second-pass approval in 2007, and despite plans to update it in 2008, it was still not updated by the time of the revised second-pass approval process in 2013.63 Instead, the Operational Concept Document from 2005 was inserted into the contracts with the successful vehicle and trailer tenderers in 2013, for reference only, despite containing operational needs that had not been updated since 2005.

2.12 In May 2015 RMMV-A informed the ANAO that:

The lack of an endorsed up-to-date [operational concepts] means that civilian or military staff, without recent operational experience, are unable or unwilling to make informed trade-off decisions during the design process where there is conflict between one or more requirements of specifications causing one requirement to take priority over others. Furthermore, it allows Military User representatives to [indicate] a particular requirement as being out-of-date on the basis of recent operational experience. This led to unnecessary time and cost and a failure to optimise Mission System performance in support of the underlying Doctrinal requirement. …

The lack of [operational concepts] means that it is not clear how the vehicle/module, known as the mission systems, will actually be used … The technical risks of integrating such systems has therefore increased.

2.13 The Function and Performance Specifications for the new medium and heavy vehicle fleet were completed in December 2003, and the Function and Performance Specifications for the vehicle and trailer support contracts were completed in October 2005. The Test Concept Document for the medium and heavy vehicle fleet was completed in February 2007. However, the Function and Performance Specifications and the Test Concept Document have not been updated since they were completed, contrary to the mandatory requirements of Defence’s capability development framework. Further, there have been significant changes in Defence’s capability requirements since the Capability Definition Documents were last updated. For example, Defence now requires many additional protected vehicles.

2.14 Defence also developed System Specifications for each vehicle and module, and released these as part of the December 2005 RFT. However, the development of System Specifications is normally undertaken by the successful tenderer once a contract has been signed, based on the Capability Definition Documents completed by Defence. Defence subsequently updated the System Specifications in 2013, and used them—in place of the out-of-date Operational Concept Document and Function and Performance Specifications—in the contracts with the vehicle and trailer suppliers.

2.15 In the absence of updated Capability Definition Documents, Army developed a two-page vehicle key requirements matrix, which provided a high-level overview of the complex System Specifications. The key requirements matrix was referenced in the 2013 contract with RMMV-A. While the matrix was a useful overview document, it was an inadequate substitute for complete and up-to-date Capability Definition Documents.64 In May 2014, a DMO Gate Review Board65 observed that Defence’s approach to developing Capability Development Documents for Land 121 Phase 3B could lead to risks down the track, particularly as staff rotate through the areas of Defence responsible for the acquisition.

The required capability

2.16 The Capability Definition Documents prepared between 2003 and 2007, though significantly out-of-date and not actually in use by Defence, provide the only formal guidance on the capability required across the medium and heavy vehicle fleet, including associated trailers for each type of vehicle variant

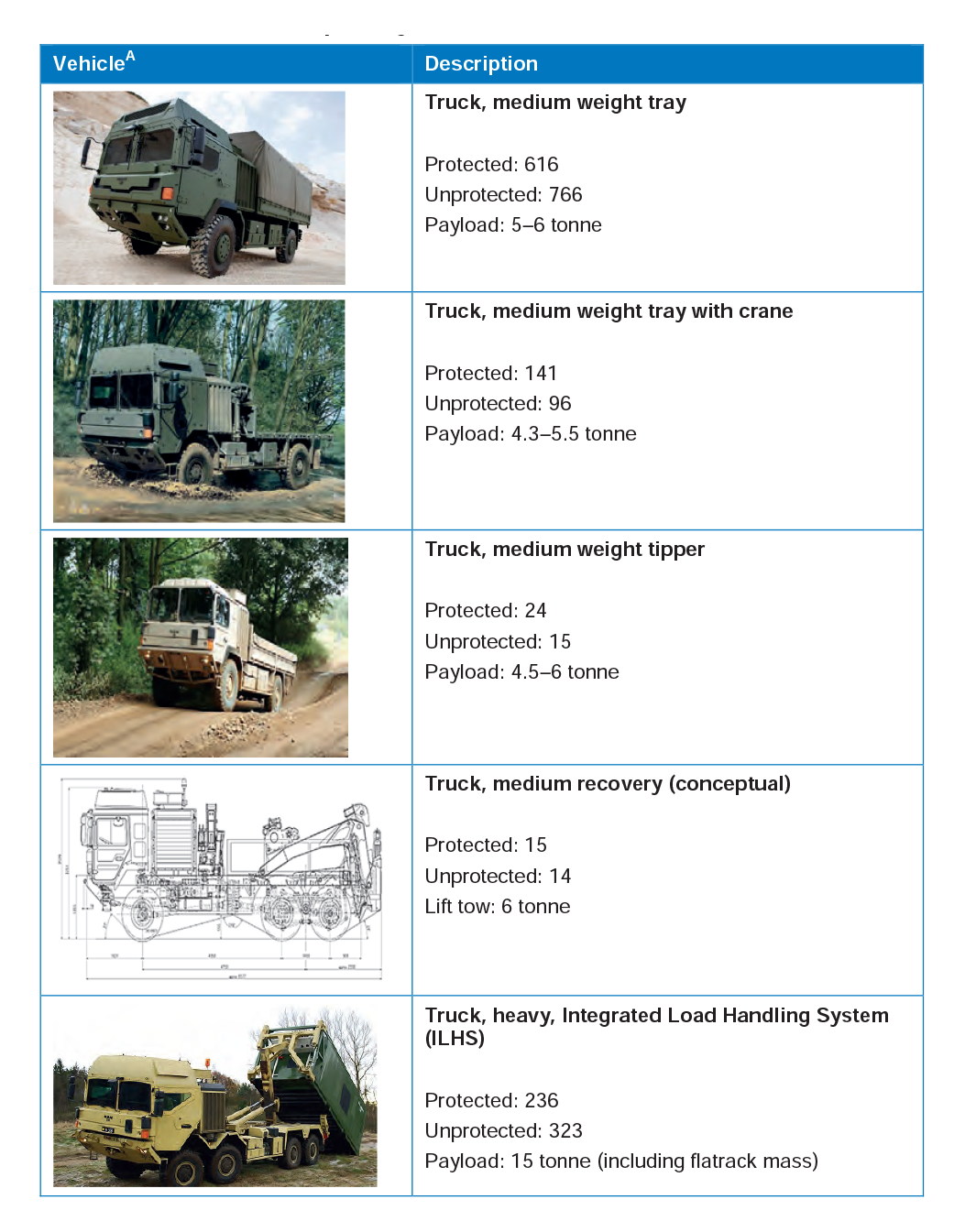

2.17 The Function and Performance Specifications established the formal requirement for eight vehicle variants. Table 2.2 illustrates the vehicle variants, and the current required numbers as specified in the latest Basis of Provisioning.66

Table 2.2: Required variants and quantities—medium and heavy vehicle capability

Source: Department of Defence.

Note A: The vehicles pictured in the table are the Rheinmetall MAN variants proposed as part of the successful 2010 tender bid.

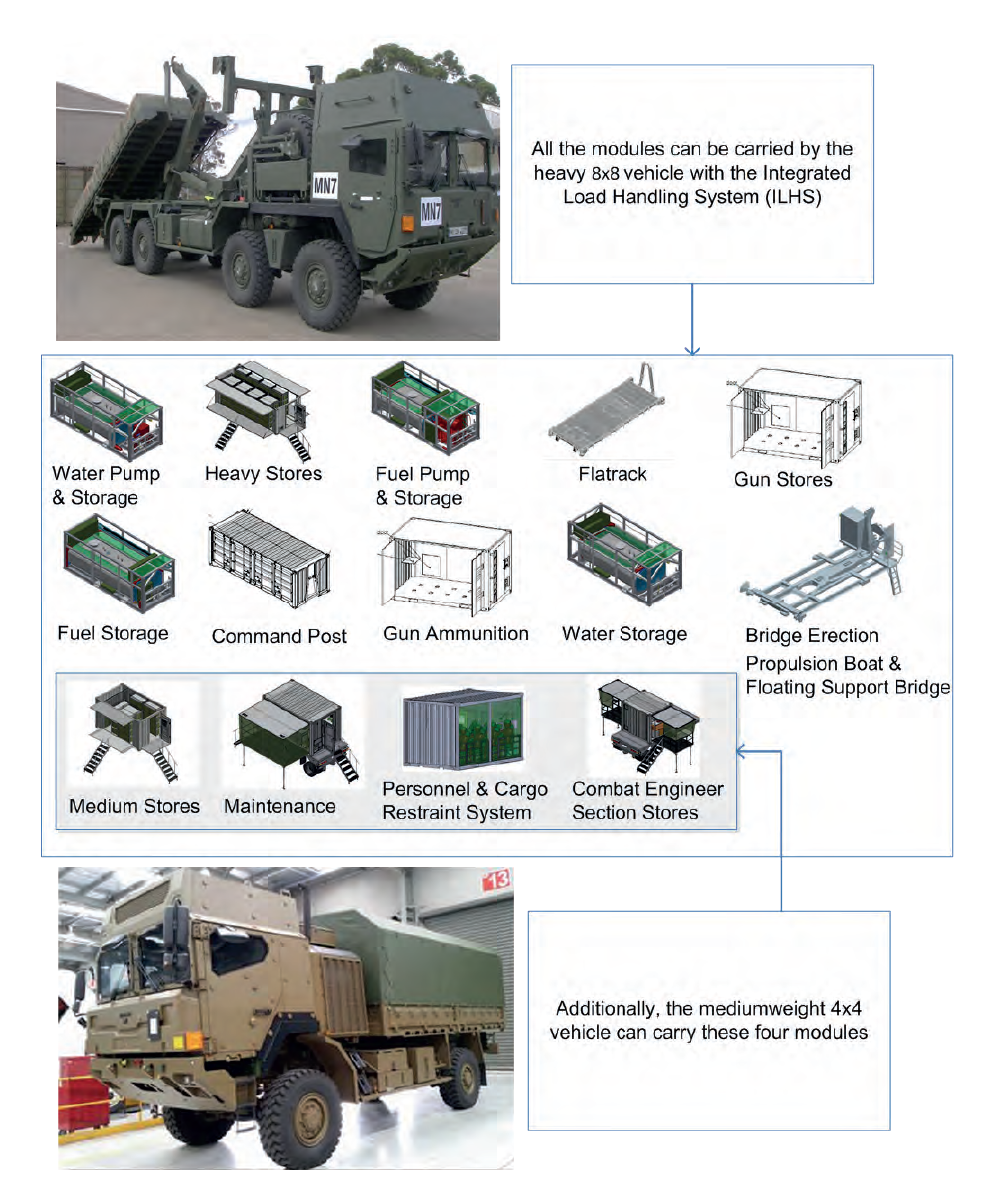

2.18 Significant capabilities to be incorporated into the new fleet of medium and heavy vehicles include the use of modules, Integrated Load Handling Systems (ILHS) and standardised load packaging.

Modular material handling

2.19 Defence’s in-service medium and heavy vehicle fleet comprises dedicated variants with the functional element, such as a stores or maintenance structure, permanently fixed to the basic vehicle. This limits the potential to fully utilise the vehicle and the availability of the supported function, and requires holding additional dedicated variants in repair and replacement pools.

2.20 The new capability will introduce modularisation into the medium and heavy vehicle fleet. Modularisation allows the interchange of modules, containers and flat racks with different functions onto the same basic vehicle chassis. Figure 2.2 shows how a basic vehicle can be used for different purposes by installing different modules or containers on the back. This approach increases the operational flexibility provided to a commander—for example, if a vehicle becomes inoperable, the module or container can be transferred to a serviceable vehicle.

Figure 2.2: Use of modules on medium and heavy base vehicles

Source: Department of Defence.

Integrated Load Handling System

2.21 The current fleet requires load handling equipment and operators to be present at all points of the distribution chain to load and unload the trucks. The new capability will include vehicles with an ILHS incorporated onto the chassis of the vehicle. This increases the operational flexibility of the distribution network, as the vehicles can deliver supplies without additional load handling equipment and operators. Figure 2.3 shows a vehicle fitted with an ILHS self-loading a container.

Figure 2.3: Integrated Load Handling System

Source: Department of Defence.

Standardised load packaging

2.22 The Defence supply chain makes use of vehicles, aircraft and ships to transport supplies. If each transporting element uses a different-sized pallet or container, time is wasted in repackaging supplies when they are moved from one type of transport to another. The supply chain is streamlined by using a uniform packaging standard. The medium and heavy vehicle fleet will use modular load packaging, consistent with the rest of the Defence supply chain, including:

- small load units: this is a box pallet that will fit within larger containers;

- twenty-foot equivalent units: these are International Standards Organization (ISO) containers and platforms that can be divided into three groups:

- ISO containers;

- equivalent units; and

- Bulk Liquid Modules;

- flat racks: these can carry an ISO container, packaged items or oversized items. A narrower, shorter flat rack can fit inside an ISO container.

Basis of Provisioning

2.23 Establishing a Defence capability requires clear engineering requirements, as discussed, and defining the numbers of assets required to meet objectives. This is achieved through the Basis of Provisioning process. The Army defines the Basis of Provisioning as:

… a determination of the quantity of an asset that the Army is required to hold in order to support preparedness and mobilisation objectives. A [Basis of Provisioning] takes into consideration unit entitlements, operating stocks required to support the [in-service] fleet, reserve stocks and attrition stocks.67

2.24 The current medium and heavy vehicle and trailer fleet was delivered to the ADF between 1967 and 2003, following many separate procurement processes. Land 121 Phase 3B is replacing all of the in-service vehicles through a single procurement, and calculating the Basis of Provisioning has been a much more involved process for Phase 3B than for the previous acquisitions.

2.25 An initial Basis of Provisioning for Land 121 was developed in 2004. Army units were asked to: identify medium and heavy vehicle task requirements; review medium and heavy vehicle role summaries, capacity and capability; review a draft Basis of Provisioning by comparing current medium and heavy vehicle tasks with future operations; and identify shortfalls in the draft Basis of Provisioning.

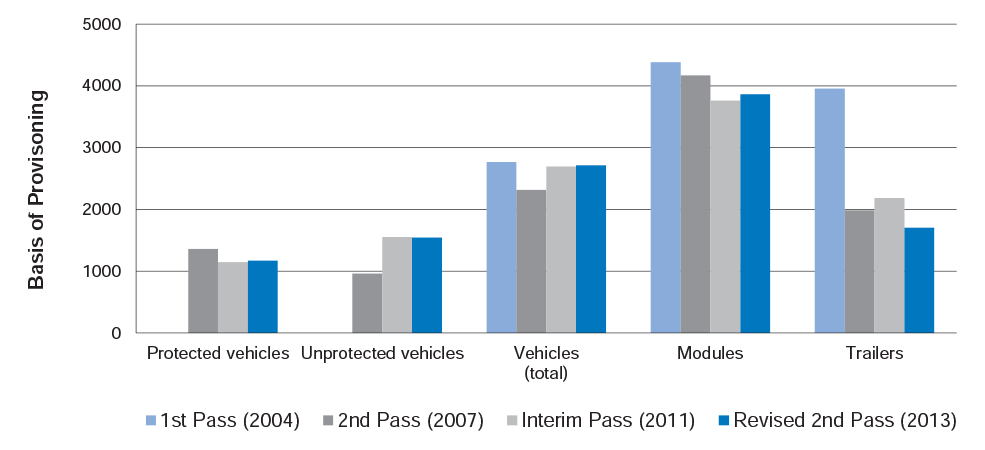

2.26 Since its initial development in 2004, the Basis of Provisioning has undergone numerous changes in terms of the number and type of vehicles required; vehicle characteristics such as blast and ballistic protection; and module and trailer requirements. Defence also applied different methodologies over time to develop the Basis of Provisioning. Figure 2.4 illustrates overall changes in the Basis of Provisioning for the medium and heavy vehicles, at key decision points since 2004. Numerous changes were also made in respect to the number of vehicles within each class.

Figure 2.4: Changes to the Basis of Provisioning

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by the Department of Defence.

2.27 In 2007, just prior to initial second-pass approval, the Defence Science and Technology Organisation published the results of its analysis of the Basis of Provisioning for Land 121, which indicated that:

… given the lack of important input data, such as quantifiable government guidance on the size of vehicle fleets for strategic response options, the process of estimating [the field vehicle and trailer] Basis of Provisioning is inherently inaccurate. This study indicates that even the best analysis is only likely to provide Basis of Provisioning estimates of around ten per cent accuracy.

2.28 While some level of inaccuracy in the Basis of Provisioning can be expected, as can some degree of adjustment over time, Defence also made significant adjustments to required vehicle numbers and types based on the availability of project funding. While this was a pragmatic approach, it did not align with the key purpose of the Basis of Provisioning process, which is expected to be an ‘objective’ measure of capability requirements, rather than a statement of the assets which can be acquired within an available budget.

2.29 ANAO Audit Report No.41 1998–99, General Service Vehicle Fleet, also found that Defence’s medium and heavy recovery vehicle procurement Basis of Provisioning had been influenced by the availability of funds:

… the ANAO examined the calculation of Basis of Provisioning for a current acquisition project (medium recovery vehicles) and found that the Basis of Provisioning had been adjusted having regard to the availability of funds. In the longer term this will result in an understatement of the requirement to support the Army in the event of a military contingency. The ANAO considers the Basis of Provisioning calculation should reflect an accurate assessment of the level of stocks required by Army to fulfil its preparedness objectives, even if insufficient funds are available to procure the full requirement.

2.30 Defence informed the ANAO in April 2015 that:

[Basis of Provisioning] was not based on affordability. However, the supplied fleet following consideration was based on affordability. The [Basis of Provisioning] was then adjusted.

2.31 Defence needs to maintain a clear view of any gap between the capability it requires to support preparedness and mobilisation objectives, and the affordable capability. This enables Defence to advise government about any potential gap between the required and affordable capability. However, the current Defence Instruction (Army) on the Basis of Provisioning for Army capabilities was issued in 1999 and has not been updated. To provide greater certainty in the development of relevant Defence assessments and advice, Defence should develop contemporary guidance on how to calculate and maintain the Basis of Provisioning for specialist military equipment.

Recommendation No.1

2.32 To provide greater certainty in the development of relevant assessments and advice, the ANAO recommends that Defence develop contemporary guidance on the Basis of Provisioning for the acquisition of specialist military equipment for the Australian Defence Force.

Defence’s response:

2.33 Agreed. Whilst Defence agrees with the intent of the one recommendation, we reinforce that value for money is a key consideration during every tender process. Defence will review its policy on Basis of Provisioning to ensure it is current and applicable in the acquisition of specialist military equipment.

Conclusion

2.34 Defence developed Capability Definition Documents during the initial stages of the medium and heavy vehicle fleet acquisition process between 2004 and 2007, but did not complete or update them for the purpose of supporting government second-pass approval processes in 2007 and 2013, or when negotiating and entering into contracts in 2013. Defence instead developed a set of non-standard documents to inform contracts, design review processes and test and evaluation, contrary to Defence policy.68 In May 2014, a DMO Gate Review Board observed that Defence’s approach to developing Capability Development Documents for Land 121 Phase 3B could lead to risks down the track, particularly as staff rotate through the areas of Defence responsible for the acquisition. Defence’s approach in this instance has also contributed to uncertainty for industry contractors in developing solutions, particularly for elements of the design that remain subject to change, and in relation to systems integration.

2.35 The Basis of Provisioning is a process for determining and recording the quantity of an asset that Army is required to hold in order to support preparedness and mobilisation objectives. Adjustments to the Basis of Provisioning would normally be made to reflect a change in the capability requirements of Army, or a change in the capability characteristics of an asset. The difference between the number of assets listed in the Basis of Provisioning required to meet Army’s capability requirements, and Army’s actual number of assets, is the capability gap. In this respect, the Basis of Provisioning is expected to be an ‘objective’ measure of capability requirements, rather than a statement of the assets which can be acquired within an available budget.

2.36 While some adjustment can be expected over time, the Basis of Provisioning for Land 121 Phase 3B has undergone numerous changes since 2004: in terms of the number and type of vehicles required; vehicle characteristics such as blast and ballistic protection; and module and trailer requirements. Defence applied different methodologies over time to develop the Basis of Provisioning, and more fundamentally, made significant adjustments to required vehicle numbers and types based on the availability of project funding—a pragmatic approach which did not align with the key purpose of the Basis of Provisioning process. Defence needs to maintain a clear view of any gap between the capability it requires to support preparedness and mobilisation objectives, and the affordable capability. However, the current Defence Instruction (Army) on the Basis of Provisioning for Army capabilities was issued in 1999 and has not been updated. To provide greater certainty in the development of relevant Defence assessments and advice, Defence should develop contemporary guidance on how to calculate and maintain the Basis of Provisioning for specialist military equipment.

3. Initial Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Tender Process

This chapter examines the initial medium and heavy vehicle fleet tender process conducted between 2005 and 2007, including industry solicitation, the tender evaluation and advice to government.

Introduction

3.1 Defence issued an Invitation to Register Interest (ITRI) for the supply of a replacement medium and heavy vehicle and trailer fleet in August 2003.69 The ITRI noted that the funding provision for the fleet in the Defence Capability Plan70 was sufficient to replace the in-service fleet, provided that a mix of military off-the-shelf (MOTS) and commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) vehicles was procured. In November 2003, Defence shortlisted nine respondents to the ITRI as possible suppliers of the medium and heavy vehicles.

3.2 The Defence Capability Committee met in December 2003 to consider the way ahead for the medium and heavy vehicle fleet acquisition, and decided that the cost information obtained through the ITRI was not of sufficient quality to proceed to the first and second-pass approval stages. The Committee instead agreed to seek first-pass approval from Ministers to release a Request for Tender (RFT), limited to the nine shortlisted suppliers, prior to seeking second-pass approval.71

3.3 On 16 June 2004, the then Government granted first-pass approval for Land 121 Phase 3, including the acquisition of the new medium and heavy vehicle and trailer fleet. Defence was directed to develop, release and evaluate an RFT for the fleet and examine the appropriate combination of MOTS and COTS vehicles. At this time, Defence anticipated that MOTS vehicles would be more rugged, durable and a better capability fit, and COTS vehicles would be adequate in some circumstances and cheaper to acquire.

3.4 At first-pass, the Government decided that Land 121 Phase 3 would be a cost-capped project. Ministers approved up to $3.4 billion for acquisition of both the light/lightweight and medium and heavy vehicle segments, with trade-offs to be made between individual vehicle features and vehicle numbers to stay within budget. The Government also noted its expectation that trucks would be sourced from overseas suppliers, and modules and trailers would be sourced from Australian companies.

3.5 In this chapter, the ANAO examines:

- Defence’s Land 121 Phase 3 Acquisition Strategy, developed after release of the RFT;

- tender responses and Defence’s tender evaluation;

- second-pass approval of Land 121 Phase 3 in 2007; and

- Defence’s Offer Definition and Refinement Process (ODRP) for the medium and heavy vehicle segment.

Acquisition strategy

3.6 Defence released RFTs for Land 121 Phase 3 in December 200572, with responses required by 21 June 2006. Defence also finalised its Land 121 Phase 3 Acquisition Strategy in June 2006. The Strategy recommended a single prime contractor for the supply of the medium and heavy trucks to realise savings in acquisition and sustainment, through reduced project office costs, reduced contract management overheads and simplified logistics support to operations.73 The Acquisition Strategy noted that a complete MOTS fleet would not be affordable.

3.7 The Acquisition Strategy outlined Defence’s plan for second-pass approval. Under the plan, Defence was to provide the Government with a shortlist of two suppliers for each vehicle segment, as well as the Phase 3 trailers. Following government approval, the selected tenderers would then take part in an ODRP, involving a comparison of the two top-rated tenderers to establish the most suitable capability solution. The Acquisition Strategy differed from standard practice in that second-pass approval normally involves government selecting a preferred capability solution following an ODRP.

3.8 Under the Acquisition Strategy, preliminary testing and evaluation of vehicles would only occur during the ODRP, after two options were selected by the Government at second-pass. This approach introduced risk, in that Defence’s recommendation on the two preferred options would not be informed by any preliminary vehicle testing.74 Defence relied instead on the integrity of the data provided by the vehicle suppliers in response to the RFT. The risks inherent in this approach would materialise during the ODRP.75

Evaluation of tender responses

3.9 As indicated, responses to the medium and heavy vehicle segment RFT were required by 21 June 2006. Of the nine vehicle suppliers invited to tender, five provided responses. Table 3.1 lists the suppliers.

Table 3.1: Responses to the initial medium and heavy vehicle tender

|

Tenderer |

Proposed primary module provider |

|

Mercedes-Benz Australia/Pacific (formerly DaimlerChrysler Australia/Pacific) which offered its S2000 and Actros family of vehicles |

Royal Wolf |

|

MAN Nutzfahrzeuge of Germany, which offered its own vehicles |

Royal Wolf |

|

Stewart and StevensonA which offered its family of medium tactical vehicles |

Royal Wolf |

|

Mack Trucks, which offered its Renault family of vehicles |

G.H. Varley |

|

Thales (formerly ADI) which offered vehicles from Oshkosh Trucks of Wisconsin USA |

G.H. Varley |

Source: Defence tender documentation.

Note A: Stewart and Stevenson was acquired by BAE Systems on 31 July 2007.

3.10 The tender responses indicated that the cost of MOTS vehicles and modules would be some 20 and 50 per cent higher, respectively, than anticipated in June 2004, when the Government provided first-pass approval. It became clear during the evaluation that balancing the capability requirements and cost restrictions would be a significant challenge for Defence.

3.11 Defence’s Tender Evaluation Plan was endorsed by DMO’s Head Capability Systems on the closing date for tender responses, 21 June 2006. The Tender Evaluation Plan included the following evaluation criteria:

- the tenderer’s ability to meet the Commonwealth’s capability and support requirements;

- the price, affordability and value-for-money of the tenderer’s capability solution, and the proposed through-life support;

- the level of risk attached to the proposed capability solution and its ability to satisfy Australian Industry Capability Outcomes;

- the ability of the tenderer to commit to a long-term strategic relationship, and the availability of intellectual property to the Commonwealth; and

- the tenderer’s compliance with the conditions of tender and the draft conditions of contract.

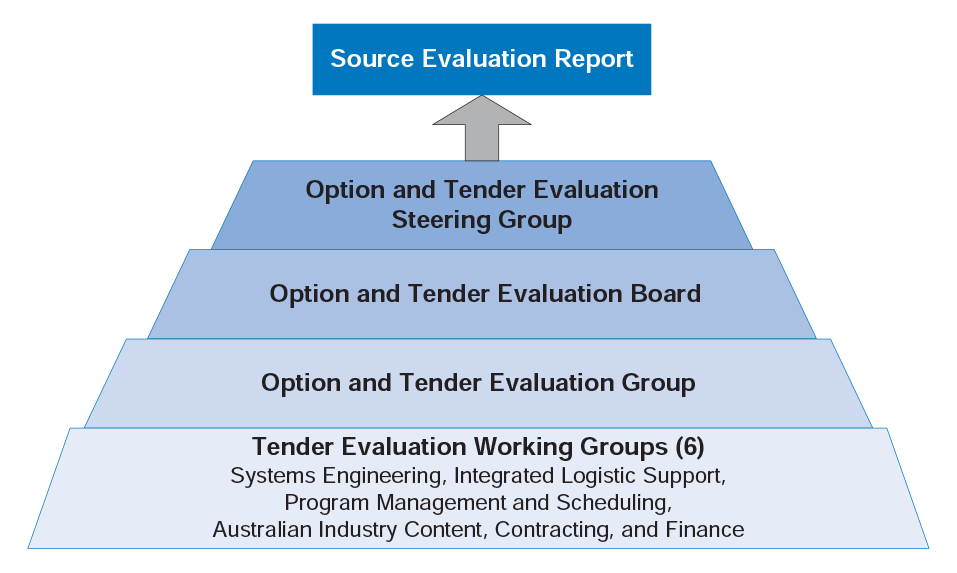

3.12 The tender evaluation was undertaken by six Tender Evaluation Working Groups (TEWGs), and subject to three levels of review (Figure 3.1). Each TEWG examined a specific aspect of the proposals—such as systems engineering or contracting—and prepared a report which was incorporated into the overarching Source Evaluation Report.

Figure 3.1: Tender evaluation management structure

Source: Defence, Source Evaluation Report for Land 121 Phase 3, August 2007.

3.13 The TEWGs’ findings in relation to the successful 2007 tenderer, Stewart and Stevenson, are summarised in the following paragraphs.

Systems engineering

3.14 The overall assessment of the Systems Engineering TEWG of the Stewart and Stevenson proposal against Defence’s requirements was ‘marginal’ with a risk level of ‘high’. Based on Defence’s vehicle requirements, the TEWG rated the Stewart and Stevenson vehicles, and the armoured protection offered for the vehicles, as ‘Deficient—Critical’. While the TEWG noted several vehicle strengths, including load capacity, reliability, use of automatic transmissions and anti-lock braking systems, the proposed vehicles were also assessed as not meeting Defence requirements. For instance:

- the medium-weight vehicles, and medium and heavy recovery vehicles did not comply with Australian road regulations;

- the medium-weight vehicles did not have specified roll-over protection, and both the medium and heavy vehicles did not comply with the static rollover requirement;

- when fully laden, the medium vehicles were unable to tow a fully laden trailer;

- the recovery vehicles could not tow a significant proportion of the required loads, and the medium recovery vehicle had deficiencies in its recovery apparatus; and

- the prime movers were COTS, and lacked specific military features, including adequate armoured protection.

3.15 Further, the Source Evaluation Report noted that:

Although the [Stewart and Stevenson] trucks are based on [in-service] vehicles, most will be significantly modified or used outside their proven capabilities—many payloads claimed in the offer are significantly higher than those of the [in-service] variants—creating schedule and capability risks.

3.16 The Systems Engineering TEWG was not able to assess the module capability proposed by Stewart and Stevenson, as the modules were conceptual at the time of tender—that is, they did not yet exist. The Stewart and Stevenson proposal was ranked fourth out of five by the Systems Engineering TEWG.

Other TEWG assessments

3.17 Five other TEWGs evaluated aspects of the proposals. The TEWGs identified a number of further issues and risks relating to the Stewart and Stevenson proposal. Table 3.2 summarises the findings of the TEWGs on the proposal’s ability to meet Defence’s specific requirements, and the proposal’s ranking against the other four proposals.

Table 3.2: Ranking of Stewart and Stevenson proposal

|

Subject matter |

Ranking |

Issues identified |

|

Integrated logistics support |

3rd |

The overall assessment was ‘strong’ with a risk level of ‘extreme’. The main strength was Stewart and Stevenson’s background in Defence procurement. However, Stewart and Stevenson also had limited capacity to provide through-life support services in Australia, and would need to engage subcontractors. |

|

Program management and scheduling |

3rd |

The overall assessment was ‘fair’ with a risk level of ‘extreme’. The key strengths of the Stewart and Stevenson proposal were its well-structured schedule, and its experience in providing capability solutions and contract support. However, significant risks were identified in relation to the proposal’s optimistic timeframes, and the compression of critical activities increased schedule risk. |

|

Australian industry content |

5th |

The overall assessment was ‘fair’ with a risk level of ‘high’. There were no strengths identified for the Stewart and Stevenson proposal. The issues identified included a lack of detail on Australian industry involvement and the role of foreign suppliers. The TEWG also noted that the local workforce may lack the necessary skills to implement the contract. |

|

Contracting |

5th |

The overall assessment was ‘unsatisfactory’ with a risk level of ‘high’. The TEWG noted in relation to the Stewart and Stevenson proposal:

|

|

Finance |

1st |

The overall assessment was ‘strong’ with a risk level of ‘medium’. Stewart and Stevenson provided the cheapest proposed capability solution. The main issue identified in the response was a lack of detail regarding training costs. |

Source: Defence, Source Evaluation Report for Land 121 Phase 3, August 2007.

3.18 In summary, the TEWGs ranked the Stewart and Stevenson proposal: fifth on two criteria; fourth on one criterion; third on two criteria; and first on one criterion.

Establishing value-for-money