Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Army’s Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness and value for money of Defence’s acquisition of light protected vehicles, under Defence project Land 121 Phase 4.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light project aims to provide the Australian Defence Force with highly mobile field vehicles that are protected from ballistic and blast threats. The Department of Defence (Defence) commenced the acquisition process in 2006, and in 2008 adopted a strategy to procure the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV) being developed by the United States. The vehicle ultimately selected in 2015 was the Australian-developed Hawkei vehicle designed by Thales Australia (Thales).

2. In October 2015, Defence entered into a contract with Thales to acquire and support 1100 Hawkei vehicles and 1058 trailers. Total budget and related funding for the Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light capability, as estimated by the ANAO, is $2.2 billion.1 Defence has expended $463.1 million of project funds to 30 June 2018, as well as $293.9 million on related costs. The first Low-Rate Initial Production vehicles were scheduled for delivery in February 2018.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. This project was selected for audit because of the materiality of the procurement, the adoption of a sole-source procurement strategy, the time taken to select a vehicle, and the risk involved in manufacturing a relatively small run of vehicles when the United States was beginning a similar but much larger program.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness and value for money of Defence’s acquisition of light protected vehicles, under Defence project Land 121 Phase 4. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence conducted an effective procurement process that achieved value for money.

- Defence has established effective project governance and contracting arrangements.

Audit methodology

5. The audit method involved:

- fieldwork at Defence’s Land Systems Division in Melbourne, Defence’s vehicle testing facility at Monegeetta (Victoria), Defence’s explosives testing facility at Graytown (Victoria), the Thales facility in Bendigo (Victoria) and the Thales computing laboratory in Rydalmere (New South Wales);

- analysis of information from Defence systems covering the period 2006–18; and

- interviews with Defence project personnel and contractors.

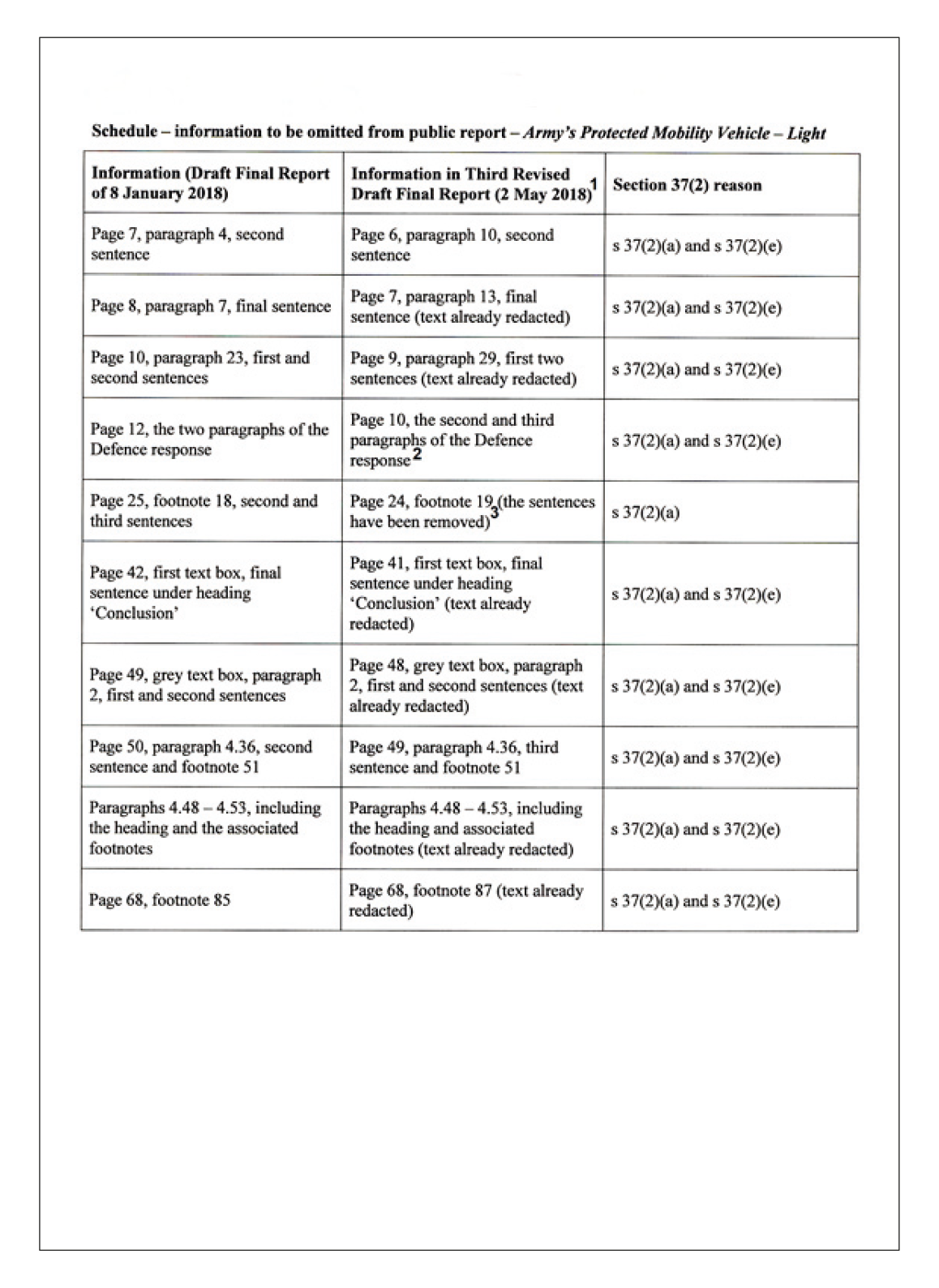

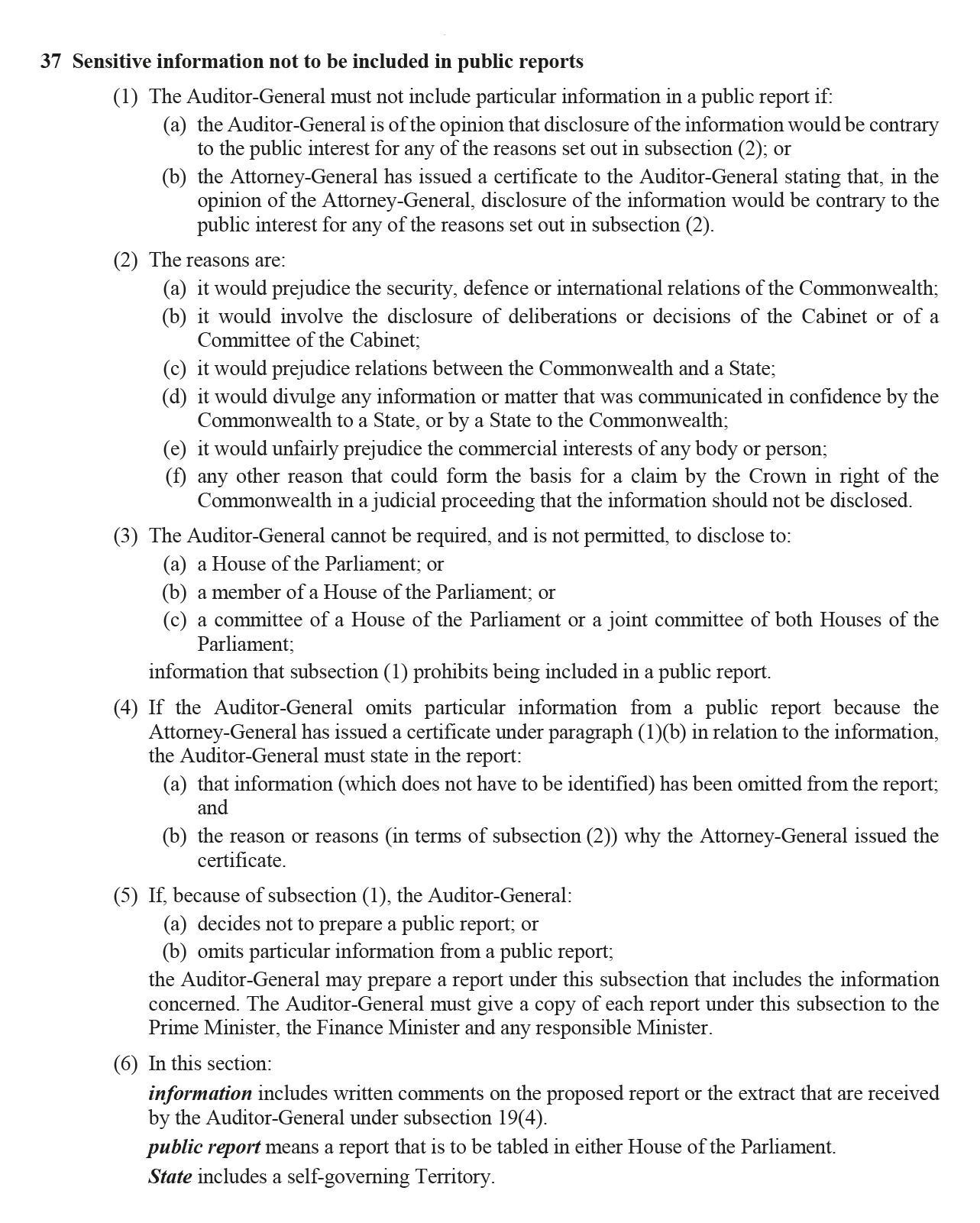

Attorney-General’s certificate

6. Information has been omitted from this performance audit report following a decision by the Attorney-General, under paragraph 37(1)(b) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act), that in his opinion the disclosure of certain information would be contrary to the public interest for one or both of the reasons set out in paragraphs 37(2)(a) and 37(2)(e) of the Act. The Attorney-General issued a certificate to this effect on 28 June 2018. The Auditor-General received the certificate on 29 June 2018. A copy of the Attorney-General’s certificate is included as Appendix 5 to this audit report. The specific information required to be omitted by the certificate has been omitted. Where information has been omitted from this report on this basis, that omission is signalled by a grey redaction square together with the words ‘Omitted—certificate’ and the relevant ground under subsection 37(2).

7. The Attorney-General’s requirement under the certificate, that the Auditor-General omit part of his audit conclusion relating to the effectiveness and value for money of this acquisition, has resulted in a disclaimer of opinion, set out in paragraph 10.

8. Under subsection 37(3) the Act, the Auditor-General cannot be required and is not permitted to disclose information omitted under subsection 37(1) to a House of the Parliament, a member of a House of the Parliament, or any committee of the Parliament. The Act further provides that if the Auditor-General omits information because of subsection 37(1) from a public report, the Auditor-General may prepare a report under paragraph 37(5)(b) that includes the information concerned, and must give it to the Prime Minister, the Minister for Finance and any responsible Minister.2 The Auditor-General provided a confidential report to the Prime Minister, Minister for Finance and the Public Service, the Minister for Defence and the Minister for Defence Industry on 6 September 2018.

9. Defence’s procurement of Hawkei vehicles has continued during the Attorney-General’s considerations regarding a certificate, and the ANAO’s performance audit engagement has also continued in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards. This report has been updated to reflect material events in the procurement until July 2018.

Disclaimer of Conclusion

10. Because of the significance of the matter described in the Basis for Disclaimer of Conclusion section of my report, I have not been able to prepare a report that expresses a clear conclusion on the audit objective in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards. Accordingly, I am unable to express a conclusion on whether the Department of Defence’s acquisition of light protected vehicles under Defence project Land 121 Phase 4 was effective and achieved value for money.

Basis for Disclaimer of Conclusion

- On 29 June 2018 I received correspondence from the Attorney-General which constituted his certificate under paragraph 37(1)(b) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act). The Attorney-General advised that in his opinion disclosure of certain information in my proposed performance audit report would be contrary to the public interest for one or both of the following reasons set out in subsection 37(2) of the Act:

- it would prejudice the security, defence or international relations of the Commonwealth;

- it would unfairly prejudice the commercial interests of any body or person.

- Under paragraph 37(1)(b) of the Act, I am thereby prevented from including particular information in this report. The information to be omitted included part of my overall conclusion in respect of the objective of the audit.

- The overall conclusion included in my proposed performance audit report stated:

Defence has invested significant effort into developing a capable light protected vehicle, including through an extensive test and evaluation program, and is procuring a design (Hawkei) that meets the majority of the requirements. Omitted—certificate—s 37(2)(a)and s 37(2)(e); see paragraph 6. Defence has established appropriate arrangements for project governance, but has accepted additional risk by entering Low-Rate Initial Production while reliability issues are still being remediated.

- The conclusion that I included in my proposed performance audit report was formed on the basis of sufficient appropriate audit evidence. The ANAO Auditing Standards require my audit report to contain a clear expression of the conclusion against the objectives of the audit. If I were to include the conclusion from the proposed performance audit report after omission of the information required by the certificate, I would not be expressing such a conclusion, and therefore it would not be in compliance with the ANAO Auditing Standards.

- As the certificate amounts to a limitation on the scope of my audit, because I am unable to table a report in the Parliament that contains a clear expression of my conclusion against the audit objective, there are two options available to me under the ANAO Auditing Standards: to withdraw from, or reduce the scope of, my audit; or publish a report including a Disclaimer of Conclusion. I decided to publish a report containing a Disclaimer of Conclusion because it is in the public interest for me to present information to the Parliament, in accordance with the Act and the ANAO Auditing Standards, to the largest extent possible in the circumstances.

Key findings

11. Defence developed six fundamental requirements for the Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light by 2009, and these have remained relatively stable. The Hawkei is a developmental vehicle, and Defence has conducted a large amount of test and evaluation covering its technical performance and useability.

12. At First Pass in 2008, a financial partnership with the United States in its JLTV Program was adopted as the primary acquisition strategy, at a cost of $43 million. In 2009, Defence sought approval to commence a parallel investment in Australian-based options that it had previously decided to be high-risk and high-cost. At Interim Pass in December 2011, Defence recommended and received approval for further development of the Thales Hawkei, because Defence considered it had the best prospect of meeting future needs, despite assessing it as the least developed Australian option. At the same time, Australia’s financial partnership in the JLTV Program was discontinued amidst uncertainty as to the program’s future, but it was retained as a possible alternative option for Second Pass. Within days of the Interim Pass decision, the United States decided to continue the JLTV Program. Defence did not reconsider its Interim Pass recommendations in the light of this significant change. The 2011 decision to discontinue Australian financial participation in the JLTV Program eroded Defence’s ability to benchmark its procurement of the Hawkei against a comparable vehicle. In the absence of reliable benchmark information, there was a reduction in Defence’s ability to evaluate whether procurement of the Hawkei clearly represented value for money.

13. Defence did not provide robust benchmarking of the Hawkei and Joint Light Tactical Vehicle options to the Government at Second Pass, to inform the Government’s decision in the context of a sole-source procurement. At Second Pass, Defence advised the Government that the Hawkei would be approximately 23 per cent more expensive to acquire than the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle but would also be more capable. Without robust benchmarking of cost and capability, Defence was also unable to apply competitive pressure in its negotiations with Thales. Defence did not inform the Minister appropriately when material circumstances changed immediately after Second Pass and before contract signature. Omitted—certificate—s 37(2)(a)and s 37(2)(e); see paragraph 6.

14. Defence has established appropriate oversight arrangements for the project. However, Defence postponed the May 2017 Gate Review, with the result that the project passed the major milestone of entry into Low-Rate Initial Production without the scrutiny offered by these reviews. Test and evaluation activity remains ongoing, as Defence entered Low-Rate Initial Production without retiring risk to the extent that it had planned. Defence has amended its contract with Thales to manage the related delays and cost increases. The project remains within the government-approved and contracted budget and scope, but reliability issues have led to schedule delays.

Supporting findings

Initial requirements and testing

15. Defence recognised early that its initial required number of vehicles (Basis of Provisioning) was unaffordable within the budget that it had been allocated, and its advice to Government consistently made this point. In 2008, Defence advised the Government that it required 1300 protected vehicles and associated trailers. In 2015, the acquisition contract provided for 900 fully protected and 200 baseline (less protected) vehicles and 1058 trailers.

16. Defence did not complete a fully developed Function and Performance Specification until July 2010, after the Request for Proposal for an Australian-manufactured option was released in June 2009. The six fundamental requirements (survivability, mobility, payload, advanced communications, useability and sustainability) have remained relatively stable during the remainder of the project, and the detailed requirements underpinning them have been refined through developmental test and evaluation. Some requirements, such as weight and reliability, have been amended in the course of development. Defence decided in 2017 to remove the exportable power requirement, which had a contracted value of $30 million. As at July 2018, Defence was considering the return of funds from Thales following removal of that requirement.

17. Readiness for an advanced communications and control system is one of the six fundamental requirements. Defence did not have a detailed specification for this aspect of the vehicle until September 2014, and two rounds of requirements definition were conducted in 2016.

18. To manage the risk of this developmental project, Defence conducted a two-stage test and evaluation program of the Land 121 Phase 4 vehicle options between 2011 and 2013, including: user tests; landmine blasts; side blasts; ballistics testing; and air transportability testing. This program has contributed to Defence procuring a design (Hawkei) that meets the majority of its requirements.

19. By late 2013, the Hawkei design still represented a high risk. Defence amended some requirements as a result of the findings of the test and evaluation program, and conducted an additional Risk Reduction Activity during 2014, reducing the design risk to medium. Defence did not expect to achieve a stable design before signing the acquisition contract in late 2015.

The procurement process (First Pass and development contracts)

20. At First Pass in 2008, Defence adopted what it considered the least risky option of partnership in the United States JLTV Program, at a cost of $43 million, while also retaining the option of a military-off-the-shelf option. After extensive industry lobbying, Defence sought approval to commence a parallel investment in Australian-based options that it had previously decided to be high-risk and high-cost and had not presented for government consideration at First Pass.

21. Between July and November 2011, Defence received strong indications and advice from the United States Government that the JLTV Program was likely to experience lengthy delays, and possibly be cancelled. In November 2011, the Defence Minister directed that no further Australian investment in the program be made without his approval.

22. At Interim Pass in December 2011, Defence recommended, and received approval for, the Thales Hawkei as the primary Australian acquisition option following the Stage 1 test and evaluation process conducted during 2010–11. Defence considered that this design had the best prospect of meeting future needs, although it was the least developed Australian vehicle design. Defence noted that all three Australian options it had tested exceeded the project’s budget. Defence did not make the Government aware of the results of an economic study it commissioned that found there would be limited regional economic benefits from, and a substantial premium paid for, the Hawkei build.

23. Defence records indicate that a significant driver of the Hawkei project schedule was the retention of production capacity at Bendigo after Bushmaster production ceased in late 2016. Defence recommended further production of Bushmasters at Bendigo to keep the facility in operation pending possible Hawkei approval. This was funded at a cost of $221.3 million, representing more than a ten per cent increase to Defence’s expenditure related to acquiring the Hawkei capability. This expenditure was not taken into account in assessing the overall cost and value for money of the Hawkei project at Second Pass.

24. Defence did not reconsider its Interim Pass recommendations after new and potentially material information became available regarding the JLTV Program soon after Interim Pass governmental approval, and did not seek ministerial approval to continue Australian participation in the JLTV Program. The decision not to seek ministerial approval to continue in the JLTV Program reduced Defence’s ability to benchmark its procurement of the Hawkei and apply competitive pressure, and together with the decision not to factor-in related expenditure, reduced Defence’s ability to evaluate whether procurement of the Hawkei clearly represented value for money.

The procurement process (sole-source tender and Second Pass acquisition decision)

25. Defence decided to release a sole-source Request for Tender for the Hawkei in 2014. In this context, Defence usefully sought benchmarking analysis from a consultancy in 2014. The benchmarking analysis had to rely on 2011 open-source information for the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle for both price and capability (as Defence was no longer a partner in the JLTV Program). The analysis also compared the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle’s 2011 compliance with requirements with the Hawkei’s expected 2023 compliance with requirements.

26. Defence’s assumptions as to government support for ongoing vehicle production at Thales’ Bendigo facility and workforce continuity at the facility led Defence to maintain its schedule to Second Pass, rather than seeking consideration of a delay to obtain reliable benchmarking data.

27. Although the Government decided in 2011 that the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle would be the alternative option to the Hawkei, Defence’s comparison of this vehicle with the Hawkei at Second Pass in August 2015 was not based on up-to-date information. As discussed above, Defence’s consultancy advice provided to the Government at Second Pass—that the Hawkei would be 23 per cent more expensive to acquire than the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle, but would be a more capable vehicle—relied on 2011 open-source data for the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle for both price and capability.

28. Defence did not advise the Minister of the full implications of new and potentially material information—which included cost information—when the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle manufacturer was selected by the United States one week after Second Pass. Defence did not subsequently use the information available after the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle announcement to strengthen its negotiating position. Defence records indicate that Thales refused to negotiate anything of significance after it knew that the Australian Government had approved the acquisition of Hawkei vehicles. Defence advised the Minister that negotiations had been successfully concluded. The final negotiation report, completed one day after this advice to the Minister, drew to Defence’s attention significant shortcomings in the negotiation strategy and outcomes.

29. Omitted—certificate—s 37(2)(a)and s 37(2)(e); see paragraph 6. Defence advised the ANAO in December 2017 that a number of non-financial benefits of the Hawkei capability contributed to the overall value-for-money proposition of the Hawkei, including: the leading-edge protected vehicle and the Integral Computing System; the ability to adapt the capability to meet emerging threats; and the Commonwealth’s Intellectual Property rights and potential royalties. These issues were mentioned in the 2015 Second Pass advice to Government, which supported the Hawkei acquisition and outlined the 23 per cent price difference of the Hawkei over the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle.

Governance and contracting arrangements

30. Defence has established appropriate oversight arrangements for the project. Senior leadership is updated on a monthly basis about key project issues. Regular contract progress meetings are held between senior project staff from Defence and Thales. The minutes of the meetings show a detailed presentation of information from Thales, ranging across the breadth of the project, and probing questioning from Defence that shows active management.

31. The 2016 Gate Review of the project raised concerns about the major challenges facing the project office and the risk of major failure by the contractor. The Gate Review scheduled for May 2017 was postponed until October 2017. This decision meant that the project passed the major milestone of entry into Low-Rate Initial Production without the scrutiny offered by these reviews.

32. Defence has generally effective contracting arrangements, but the contractual off-ramps did not represent a practicable risk mitigation strategy, because Defence has not maintained the market knowledge required to inform an exit strategy. Relevant market knowledge would enable capability and value-for-money comparisons to be made of the Hawkei and comparable vehicles.

33. The project has conducted a series of reliability trials, and the test and evaluation period has been extended as part of this process. Defence approved entry into Low-Rate Initial Production in September 2017 while reliability issues were still being remediated through a Reliability Remediation Plan and a Reliability Demonstration Test. In compensation, Thales provided a one-year extension of the vehicle warranty and a $3 million discount on materials costs. Defence advised the ANAO in December 2017 that the core Integral Computing System—inclusive of all hardware, operating software, and the Battle Management System—is included on Low-Rate Initial Production vehicles (currently being produced). The project remains within the government-approved and contracted budget and scope, but reliability issues have led to schedule delays.

Responses to the audit

34. The proposed public and confidential reports were provided to the Department of Defence (Defence). Extracts from the proposed public report were provided to Thales Australia Limited (Thales) and to Elbit Systems of Australia (Elbit).

35. Formal responses were received from Defence, Thales and Elbit. The summary responses from Defence and Thales are provided below. The full responses from Defence, Thales and Elbit are provided at Appendices 1, 2 and 3.

Department of Defence

The Department notes the ANAO’s findings regarding the acquisition of the Hawkei – Protected Mobility Vehicle – Light and appreciates the work undertaken by the ANAO to consider Defence’s feedback in preparing the Final Report. The identified Key Learnings are acknowledged and will support Defence’s approach to capability acquisition.

The Hawkei provides Australia with a domestically developed and sovereign capability that can be modified to meet emerging threats and protect Australian Defence Force personnel.

Defence is also confident that the Hawkei has the potential to be modified to meet the requirements of our security partners and provide these nations with a highly effective capability.

Thales Australia

Thales Australia welcomes the engagement with industry in the preparation of this report, resulting in the exclusion from publication of sensitive information that could have endangered soldiers’ lives or unfairly prejudiced commercial interests.

By adopting the Australian designed and developed Hawkei the Australian Army has maintained a critical sovereign capability in protected vehicle design, engineering and manufacture in Australia. It is a capability advantage developed in the Bushmaster program that has been proven to save lives. This decision has delivered the world’s best vehicle of its type, developed and manufactured in Australia, and supporting more than 400 Australian jobs directly in the assembly and manufacturing supply chain.

ANAO comment on Thales Australia’s summary response

36. The treatment of sensitive information arises regularly in the context of Defence auditing. The ANAO has long-established processes for working with Defence to manage potential risks relating to the disclosure of sensitive information. These processes include the provision of consultation drafts to Defence, an exit interview, regular officer-level interactions, and seeking formal advice from Defence. In this audit, Defence and the ANAO worked together through an iterative process to identify and manage potential risks.

Key learnings for all Australian Government entities

The ANAO has not made recommendations in this audit report, but rather has focused on the key learnings flowing from the audit for Defence and other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Land 121 is a multi-phase project to provide the Australian Defence Force with new field vehicles, modules and trailers. In 2006, the Department of Defence (Defence) began the process of acquiring a fleet of light Protected Mobility Vehicles3 under Phase 4 of this wider replacement project (for the phases of project Land 121, see Appendix 4).

1.2 Defence’s decision to acquire a fleet of protected vehicles was the result of lessons learned from Australian Defence Force operations since 1998. Unprotected vehicles were vulnerable to ballistic and blast threats prevalent in likely areas of operation. Defence recognised that these vulnerabilities were a constraint on the Australian Defence Force’s ability to conduct operations.

1.3 Defence’s initial procurement strategy, approved by the Government in October 2008, was to participate in the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV) Program being developed by the United States Department of Defense, while retaining the option to procure a military-off-the-shelf vehicle if the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle proved unsuitable.4 Australia joined the Technology Development phase of the JLTV Program in January 2009.

1.4 In December 2008, Defence received an unsolicited proposal from Thales Australia (Thales) for development of an Australian light Protected Mobility Vehicle (now known as the Hawkei). Defence then sought government approval for a ‘Manufactured and Supported in Australia’ option, which was approved in June 2009. Six options—three from the United States and three Australian-made options—underwent test and evaluation between July 2010 and June 2011, and in December 2011, Defence advised the Government to further develop the Thales Hawkei vehicle, and to retain the United States program as a backup.

1.5 Hawkei prototypes were tested extensively between 2012 and 2014 to ensure that the design was compliant with key capability requirements. In June 2014, Defence released a sole-source Request for Tender to Thales for the Hawkei.

1.6 In August 2015, Defence advised the Government that the Hawkei was its preferred option. In October 2015, Defence entered into a contract with Thales to acquire and support 1100 Hawkei vehicles and 1058 companion trailers. In the April 2018 Defence Industrial Capability Plan, the Hawkei was listed as an example of a Sovereign Industrial Capability Priority in the category of ‘Land combat vehicle and technology upgrade’. The Plan defines Sovereign Industrial Capability Priorities as: operationally critical to the Defence mission; priorities within the Integrated Investment Program over the next three to five years; or needing more dedicated monitoring, management and support due to their industrial complexity, Government priority or requirements across multiple capability programs. Total estimated funding for the Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light capability is approximately $2237.1 million, as shown in Table 1.1, which includes project Land 121 Phase 4 budgeted funds as well as related costs.5 Defence has expended $463.1 million of project Land 121 Phase 4 funds to 30 June 2018, as well as $293.9 million on related costs.

1.7 In August 2017, Defence approved Thales’ entry into Low-Rate Initial Production, which is currently scheduled to deliver 100 Hawkei vehicles by January 2019.6

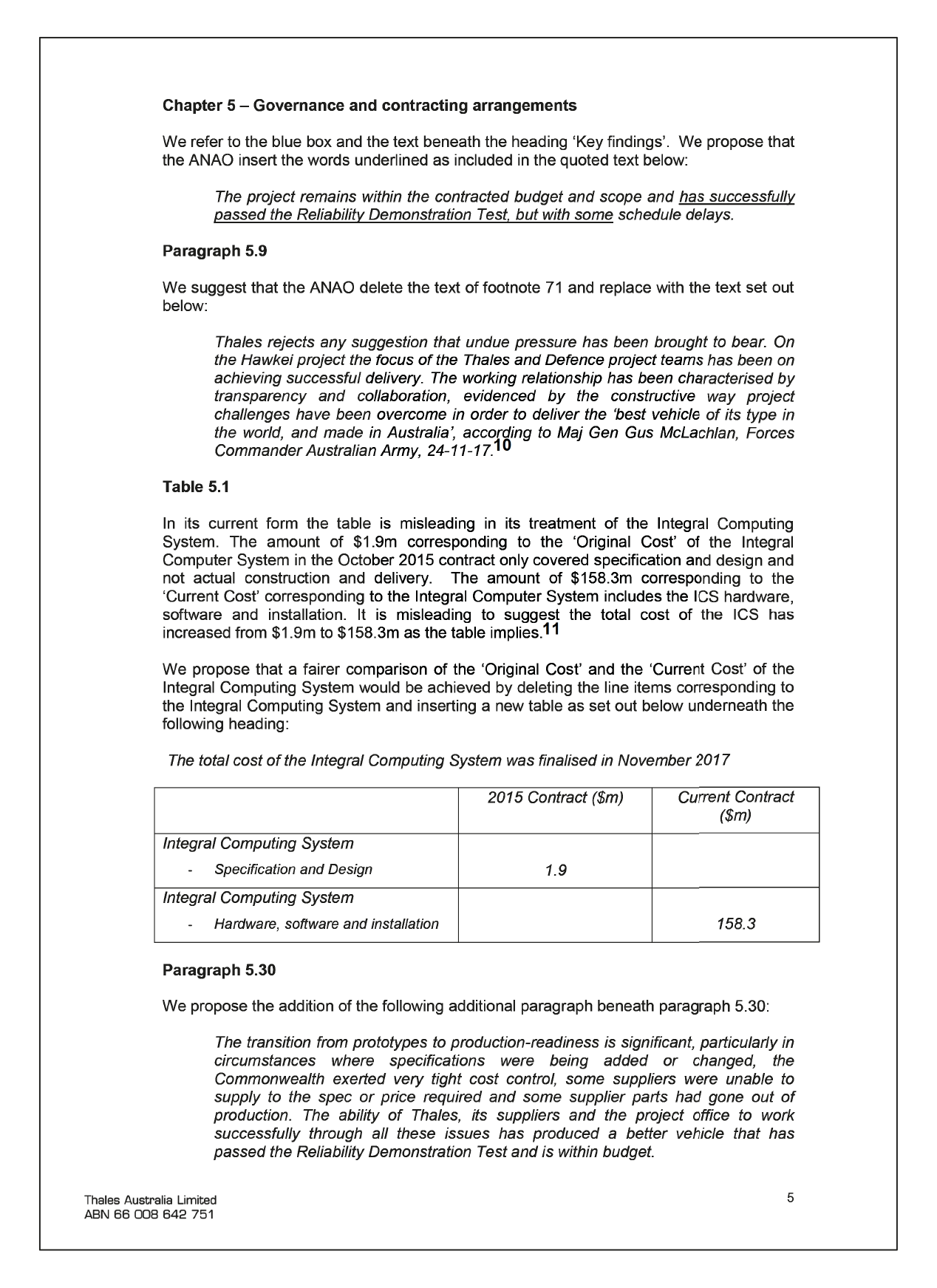

Table 1.1: Defence funding approvals (direct and related) for the Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light capability

|

Project Land 121 Phase 4 approvals |

$m |

|

First Pass |

5.7 |

|

Manufactured and Supported in Australia Stage 1 |

31.5 |

|

Manufactured and Supported in Australia Stage 2 |

48.4 |

|

Second Pass—Acquisition Contract |

1328.5 |

|

Second Pass—Support Contract and other costs |

529.1 |

|

Land 121 Phase 4 approvals subtotal |

1943.2 |

|

Related costs |

|

|

Joint Light Tactical Vehicle Partner Nation, 2009 |

43.0 |

|

Purchase of additional Bushmasters to keep Bendigo facility in operation pending possible Hawkei approval, 2012 |

221.3 |

|

Defence project office |

29.6 |

|

Related costs subtotal |

293.9 |

|

Total capability approvals |

2237.1 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

1.8 Figure 1.1 outlines the Government approval stages for project Land 121 Phase 4.

Figure 1.1: Government approval stages for project Land 121 Phase 4

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

1.9 Figure 1.2 shows the major decision points and contracts for this project.

Figure 1.2: Timeline of project Land 121 Phase 4, Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light

Source: ANAO.

Audit approach

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.10 This project was selected for audit because of the materiality of the procurement, the adoption of a sole-source procurement strategy, the time taken to select a vehicle, and the risk involved in manufacturing a relatively small run of vehicles when the United States was beginning a similar but much larger program.

Audit objective and criteria

1.11 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness and value for money of Defence’s acquisition of light protected vehicles, under Defence project Land 121 Phase 4. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence conducted an effective procurement process that achieved value for money.

- Defence has established effective project governance and contracting arrangements.

1.12 In particular, the audit examined the quality of:

- Defence’s risk analysis of different options; and

- Defence’s advice to government on value for money.

Audit methodology

1.13 The audit method involved:

- fieldwork at Defence’s Land Systems Division in Melbourne, Defence’s vehicle testing facility at Monegeetta (Victoria), Defence’s explosives testing facility at Graytown (Victoria), the Thales facility in Bendigo (Victoria) and the Thales computing laboratory in Rydalmere (New South Wales);

- analysis of information from Defence systems covering the period 2006–18; and

- interviews with Defence project personnel and contractors.

1.14 This audit is the second in a series which has reviewed key phases of Land 121. Auditor-General Report No. 52 2014–15 reviewed the Australian Defence Force’s Medium and Heavy Vehicle Fleet Replacement (Land 121 Phase 3B).

1.15 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $870 000.7

1.16 Team members for this audit were Dr Patrick O’Neill, Dr Jordan Bastoni, Sophie Gan, Zak Brighton-Knight and David Brunoro.

2. Initial requirements and testing

Areas examined

This chapter examines how Defence determined the number of vehicles required, defined the project requirements, and conducted test and evaluation activities under two successive development contracts.

Key findings

Defence developed six fundamental requirements for the Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light by 2009, and these have remained relatively stable. The Hawkei is a developmental vehicle, and Defence has conducted a large amount of test and evaluation covering its technical performance and useability.

Did Defence conduct an effective requirements definition process?

Defence recognised early that its initial required number of vehicles (Basis of Provisioning) was unaffordable within the budget that it had been allocated, and its advice to Government consistently made this point. In 2008, Defence advised the Government that it required 1300 protected vehicles and associated trailers. In 2015, the acquisition contract provided for 900 fully protected and 200 baseline (less protected) vehicles and 1058 trailers.

Defence did not complete a fully developed Function and Performance Specification until July 2010, after the Request for Proposal for an Australian-manufactured option was released in June 2009. The six fundamental requirements (survivability, mobility, payload, advanced communications, useability and sustainability) have remained relatively stable during the remainder of the project, and the detailed requirements underpinning them have been refined through developmental test and evaluation. Some requirements, such as weight and reliability, have been amended in the course of development. Defence decided in 2017 to remove the exportable power requirement, which had a contracted value of $30 million. As at July 2018, Defence was considering the return of funds from Thales following removal of that requirement.

Readiness for an advanced communications and control system is one of the six fundamental requirements. Defence did not have a detailed specification for this aspect of the vehicle until September 2014, and two rounds of requirements definition were conducted in 2016.

Vehicle numbers and budget

2.1 Defence based its initial calculations of the required numbers of Protected Mobility Vehicles — Light on strategic guidance from the Government as to Australian Defence Force readiness. In terms of process, Army used its 1999 Basis of Provisioning policy to calculate how many assets it needed. The calculation included unit entitlements, operating stocks and reserve stocks, which inform acquisition cost estimates.

2.2 In August 2007, the Government considered a Defence submission on the larger Land 121 project to replace Army’s field vehicles and trailers. Defence advised the Government that it needed some 7100 vehicles in all, with 66 per cent to be protected vehicles. Defence further advised that purchasing fewer protected vehicles, and some modified commercial-off-the-shelf vehicles, would reduce acquisition costs while allowing Defence to meet its capability requirements with acceptable risk to personnel and at a restricted scale of operations. The Government accepted this advice, opting for some 40 per cent of the field vehicles and trailers fleet to be protected, including 1243 light vehicles, with a budget provision of $1.2 billion. The Government agreed that an additional phase within Land 121, Phase 5, would deliver modified commercial-off-the-shelf vehicles to meet the remainder of the capability required under the overarching Land 121 project.

2.3 At First Pass8 in October 2008, Defence advised the Government that current strategic guidance could be met with 1300 light protected vehicles.

2.4 In February 2010, when Defence assessed the Request for Proposal for a ‘Manufactured and Supported in Australia’ option9, the Basis of Provisioning was 1300 vehicles and 1300 trailers. However, the cost of the three technically acceptable proposals for a ‘Manufactured and Supported in Australia’ option under consideration by Defence was found to exceed Defence’s budget provision for the project.

2.5 At Interim Pass, in December 2011, due to affordability issues with the larger Land 121 project, Defence sought and received Government approval for the purchase of 894 light protected vehicles, with the balance to be made up of 407 unprotected vehicles—a total of 1301 vehicles. In order to maximise the number of protected vehicles it could afford, Defence postponed any further purchase of unprotected G-Wagons.10

2.6 The sole-source Request for Tender that was released to Thales on 13 June 2014 called for the provision of 1301 vehicles, 1288 trailers and supporting services. The Thales response, in September 2014, was unaffordable under Defence’s existing provision for the project. In January 2015, Army revised its threshold numbers to 900 fully fitted vehicles, and baseline vehicles11 to as close to 1301 as funds would allow.

2.7 At Second Pass, in August 2015, Defence advised the Government that its minimum Basis of Provisioning was no fewer than 900 vehicles (with add-on armour), 200 baseline vehicles (that can be fitted with add-on armour), and trailers. The Government approved entry into negotiations with Thales as the provider.

2.8 After Second Pass, Defence negotiated with Thales to bring the Basis of Provisioning closer to the targeted number. Contract negotiations concluded on 24 September 2015, with Defence achieving the Second Pass targets.

The six fundamental requirements for the Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light

2.9 Defence began this project in 2006–07 with a broad interest in: increased mobility; survivability; sustainability; and, in selected systems, lethality.

2.10 By April 2009, Defence had settled on a balance of six fundamental requirements for its new capability, summarised in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: The fundamental requirements for the Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light, 2009

|

Fundamental requirement |

Examples |

| 1. Survivability |

Able to withstand:

Fitted with a remote weapon system |

| 2. Mobility |

On-road and off-road manoeuvrability Deployable by sea, rail, and C-130 Hercules aircraft Deployable by CH-47 Chinook helicoptera |

| 3. Payload-carrying capacity |

Different variants to carry between 1000–2000 kilograms |

| 4. Command, control, communications, computers and intelligence (C4I) readiness |

Built-in computer hardware A screen for each crew member Exportable power supplyb |

| 5. Useability |

Noise and vibration management Climate control Legal and safety compliance |

| 6. Sustainability |

Reliable Maintainable Durable Technical manuals |

Note a: The requirement for airlift underslung beneath a helicopter was originally (2007) to apply to selected vehicles only, but by 2009 was extended to all vehicles. This requirement is discussed further at paragraphs 2.36 and 2.38–2.40.

Note b: The removal of the requirement for exportable power in 2017 is discussed in paragraph 2.16.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence 2009 Key Requirements Matrix.

2.11 Defence records indicate that, after the Minister’s March 2009 announcement that a Request for Proposal for an Australian option would be released the following month (see paragraph 3.13), there was an ‘accelerated timeline to develop specifications’ for the Request for Proposal that was issued in June 2009. This accelerated timeline precluded the thorough development of an Operational Concept Document and Function and Performance Specification ‘in the format that would normally be expected’ at this stage of capability development, that is: a measure of operational needs and measures of effectiveness; and the functions, characteristics, performance and interfaces required, respectively. Instead of a fully developed Function and Performance Specification, Defence developed a six-page Key Requirements Matrix that it incorporated into the June 2009 Request for Proposal.12 Defence recognised at the time that this did not represent a rigorous analysis of the capability required.

2.12 Defence approved a more developed Function and Performance Specification in July 2010, when it also signed development contracts with the three contractors that had passed the Request for Proposal stage. This specification contained 180 requirements.

2.13 Since the Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light is a developmental project, Defence had anticipated that over time it would increase its understanding of the requirements and refine them. After a first period of test and evaluation of prototypes in 2010–11, Defence made major revisions to the requirements in December 2011.13 Defence also amended some requirements in May 2014 after the end of a further period of testing. The amended requirements included those relating to weight and reliability.

2.14 Readiness for an advanced communications and control system is one of the six fundamental requirements. In early 2014, Defence decided that the final delivery of the Integral Computing System would not occur until Final Operational Capability (2023). In August 2018 Defence advised the ANAO that the Integral Computing System is a developmental capability. Defence did not have a detailed specification for this aspect of the vehicle until September 2014, seven years after project activities commenced. Defence advised the ANAO that it underwent two rounds of requirements definition with Thales in 2016, prior to locking down the Integral Computing System specification.

2.15 The test and evaluation activities that led to the 2011 and 2014 revisions are discussed in the next section.

2.16 In March 2017, Defence decided to remove the requirement for exportable power, which had been contracted at a cost of $30 million.14 Thales offered to return $13 million, later revised to $16 million, on the basis that it manages its supply chain holistically and was forecasting cost over-runs of $32 million on other supply-chain costs for Hawkei. In April 2018, as a result of the failure to reach a mutually beneficial solution, Defence sought advice from Thales about the potential impact of reinstating the requirement. Thales responded that this would take nearly two years, with risks of design change, significant earthing requirements, and retrofit or rework. In June 2018, Defence conducted a financial investigation, which found that:

- Thales had spent $520 000 to date on the requirement;

- supply chain cost over-runs of $32 million claimed by Thales were valid; but

- the amount of contingency used by Thales for these over-runs could not be clarified.

2.17 A contract change to remove the exportable power requirement and return some funds to Defence was under consideration as at July 2018. Another Defence project15 is examining an ADF-wide solution for power generation in the field. In August 2018 Defence advised the ANAO that:

There is also no direct correlation between the contracted value of Exportable Power and the financial return to Defence following the removal of that requirement. A Financial Investigative Services review confirmed that Thales manages its supply chain holistically, and the removal of the Exportable Power requirement at the contracted price created a net over-run across the remaining work packages.

Did Defence conduct an effective test and evaluation program to inform the Government’s decision to acquire the Hawkei?

To manage the risk of this developmental project, Defence conducted a two-stage test and evaluation program of the Land 121 Phase 4 vehicle options between 2011 and 2013, including: user tests; landmine blasts; side blasts; ballistics testing; and air transportability testing. This program has contributed to Defence procuring a design (Hawkei) that meets the majority of its requirements.

By late 2013, the Hawkei design still represented a high risk. Defence amended some requirements as a result of the findings of the test and evaluation program, and conducted an additional Risk Reduction Activity during 2014, reducing the design risk to medium. Defence did not expect to achieve a stable design before signing the acquisition contract in late 2015.

2.18 In 2015, the ANAO discussed the value of test and evaluation in the Defence acquisition process:

T&E (Test and Evaluation) is a key component of systems engineering and its primary function is to provide feedback to engineers, program managers and capability managers on whether a product or system is achieving its design goals in terms of cost, schedule, function, performance and sustainment. It also enables capability acquisition and sustainment organisations to account for their financial expenditure in terms of the delivery of products or systems that are safe to use, fit for purpose and that meet the requirements approved by government.16

2.19 The ANAO has also previously noted the importance of early test and evaluation in strengthening Defence’s ability to identify and mitigate risks and provide informed advice for decision-making on a preferred supplier.17

2.20 Defence’s 2007 test and evaluation policy stipulated that key milestones for major capital equipment acquisitions required:

some form of Verification and/or Validation through T&E results to ensure that the risk is contained within acceptable boundaries, and that the intended system meets safety standards and end-user requirements.

2.21 Defence’s test and evaluation of Land 121 Phase 4 has sought to validate that the vehicle platform can provide ‘the best possible balance of six fundamental requirements’ (as listed in Table 2.1). Test and evaluation occurred in two stages. The first stage, from 2010–11, involved initial testing of the United States Joint Light Tactical Vehicle options and Australian prototypes from three different companies. The second stage, from 2012–13, involved dedicated testing of Thales’ Hawkei vehicle.

Development test and evaluation, 2010–11

Reliability testing of Joint Light Tactical Vehicle prototypes, 2010

2.22 As discussed in paragraph 1.3, Defence participated in the Technology Development phase of the United States JLTV Program. Initial Australian testing of prototypes of the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle commenced in 2010. The aim of this testing was to inform the Government’s consideration of the suitability of the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle prototypes for Australian needs. From August to December 2010, five prototypes and two trailers from two American manufacturers were tested at Defence’s facility at Monegeetta, Victoria, achieving a total test distance of 14 691 kilometres. This trial cost $1.7 million. For Defence, two key outcomes from this trial were: the demonstrated ability to conduct testing for the United States program in Australia; and the contribution to the development of the United States requirements set. Reliability later became a key focus of planned future Hawkei testing.

2.23 The Joint Light Tactical Vehicle reliability trial was suspended in December 2010, pending Defence’s development of plans for concurrent trials of United States and Australian-made vehicles.

User testing of American and Australian prototypes, 2011

2.24 During the first half of 2011, the Australian Defence Test & Evaluation Office conducted user testing on 13 prototype vehicles from six manufacturers: the three participants in the JLTV Program (BAE Systems, General Tactical Vehicles and Lockheed Martin), as well as three of the 12 responses to the Request for Proposal for a Manufactured and Supported in Australia option (Force Protection Europe, General Dynamics Land Systems–Australia and Thales Australia).18 This trial cost $1.8 million.

2.25 The user testing found that:

The PMV-L [Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light] prototypes offer significant capability enhancements on the LR110 [Land Rover] fleet which currently fill the role in the training environment, and are a lighter and more deployable protected vehicle for high threat operations compared to the Bushmaster; which is the current operational capability.

2.26 The user testing resulted in specific recommendations, including:

- a clearer articulation of the need for this class of protected vehicles; and

- review of the helicopter lift requirement so as not to impose limitations on the entire fleet.19

Survivability testing of American and Australian prototypes, 2011

2.27 The next set of test and evaluation activities assessed the level of protection offered to vehicle occupants. The trials were conducted in April–June 2011. Three United States vehicles and three Australian-option vehicles underwent various trials.

2.28 As a result of test and evaluation in 2010–11, Defence refined 17 of the 180 requirements for the capability, and added 26 requirements. This six-month process was completed in December 2011, just before Interim Pass consideration of the project by the Government.

2.29 By June 2011, the participants in the Manufactured and Supported in Australia option had achieved the following compliance with the requirements:

- Company A: 54 per cent, but critically deficient in payload.

- Company B: 67 per cent, but critically deficient in survivability.

- Thales: 34 per cent.

Development test and evaluation, 2012–14

2.30 The Test Concept Document developed by Defence in November 2011 for the Interim Pass decision envisaged:

- two years of Development Test and Evaluation (2012–13);

- one year of Acceptance Test and Evaluation (2015); and

- several months of Operational Test and Evaluation (2017).

2.31 The Development Test and Evaluation would include Reliability, Availability and Maintainability (RAM) assessments, user trials and survivability trials.20

Reliability testing, 2013

2.32 During 2013, under contract to Defence, Thales conducted studies to predict the reliability of the Hawkei.21 Reliability is a key aspect of the overarching Sustainability requirement. In November 2013, Thales reported that the Hawkei should meet Defence’s targeted Mean Time Between Failures of 1000 kilometres, but was unlikely to meet the required Mean Time Between Critical Failures of 10 000 kilometres.22 Thales recommended 5000 kilometres as a more achievable figure for the latter target.23

User testing, 2012–13

2.33 From October 2012 to August 2013, the then Defence Materiel Organisation and the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO) assessed the ergonomic and Human–Machine Interface characteristics of the Hawkei. This included DSTO re-evaluation of Hawkei-specific trial data from 2011. The DSTO made a number of recommendations relating to seat design and adjustment, seat restraints, design of primary and secondary controls, and the integration of the body combat armour with the vehicles.

2.34 In September 2013, Defence conducted eight days of operationally focused user trials at Townsville and Cowley Beach (Queensland). These locations represented more realistic operating conditions than Defence’s vehicle test facility at Monegeetta (Victoria), but Defence’s test agency judged that this was still short of the ideal hot–wet tropical test conditions typical of Australia and South East Asia.

2.35 After the trial, the Australian Defence Test & Evaluation Office reported that:

The Hawkei demonstrated that it is relatively easy to drive, comfortable, capable and highly mobile. Despite being a prototype, the vehicle demonstrated reasonable reliability, good handling and was generally well designed.

2.36 The report identified four main issues with the Hawkei, concluding that:

The most significant issue revealed by DT 903 [the trial] was the significant design compromise required to meet the CH47 EL [Chinook external airlift] requirement. This requirement places great constraints on the design and therefore the effectiveness of the vehicle. This requirement may also drive the through-life cost of ownership and these costs need to be carefully estimated and accepted.

2.37 In relation to the capability requirement for the Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light, the report suggested that Defence should carefully examine whether the Hawkei constituted a general-purpose Land Rover replacement or a specialist airlift Protected Mobility Vehicle–Light. In the latter case, consideration was suggested of a mixed fleet of Hawkei and next-generation Bushmaster, or two variants of Hawkei (a lightweight airlift version and a heavier general-service version). The report made 130 specific recommendations to improve the design and operation of the Hawkei.

Helicopter airlift test was postponed in 2013

2.38 Defence originally planned to trial the external airlift of a Hawkei by a Chinook helicopter during 2012–13, having identified airlift as a high priority for testing. A preliminary study of the Hawkei’s suitability for airlift in September 2012 found that the Hawkei had not been designed in accordance with the relevant airlift standard, and indicated that further development work would be required.

2.39 Early in 2013, Defence removed airlift from the scope of the current trial, because of extensive tasking of the Air Movements Training and Development Unit (the unit had a five-year backlog) and a lack of civilian contractors with appropriate engineering experience within Australia. Defence’s main test agency pointed out that significant planning shortcuts during 2012 had led to a lack of consultation with test agencies.

2.40 In lieu of an airlift trial using a helicopter, Air Force’s airlift test unit conducted a proof-of-design activity in May 2013, lifting three different Hawkei vehicles and the trailer with a crane. Air Force concluded that there was a low risk that production vehicles would be deemed unsuitable for airlift. Helicopter airlift was successfully tested in June 2017.

Survivability testing, 2013

2.41 The DSTO conducted two additional landmine tests on the Hawkei in August–September 2013.

2.42 In July–August 2013, the DSTO also assessed the Hawkei for protection against ammunition and fragmentation threats. The DSTO was confident that some identified deficiencies could be rectified by minor integration effort in future design evolutions.

Defence amended some requirements as a result of the 2012–13 testing, and further development and testing was undertaken before Second Pass

2.43 Due to the project’s internal budget, the overall aim of the test and evaluation program during 2012–13 was to develop the Hawkei to meet 71.3 per cent of the threshold requirements and 27.9 per cent of the objective requirements.24 In its assessment of Thales’ performance during this stage, Defence found that Thales had achieved 54 per cent of the total requirements (Table 2.2) including ‘most of the key requirements’ bar one.

Table 2.2: Achievement of design requirements for the Hawkei by end of 2013

|

Requirement rating |

Number of requirements |

Achieved by end of 2013 |

Percentage achieved |

|

Threshold (minimum) |

425 |

292 |

68.7 |

|

Objective (preferred) |

208 |

53 |

25.5 |

|

Total |

633 |

345 |

54.5 |

Source: Adapted from Defence, Contract Performance Assessment Report, March 2014.

Evaluation of results and additional Risk Reduction Activity

2.44 In December 2013 Defence contracted Thales to conduct a nine-month Risk Reduction Activity, at a cost of $11.4 million, mostly funded through the use of $10.9 million of the project’s contingency funding.25 Defence recognised at this time that it was unlikely that the project could achieve full development of the remaining 30 per cent of threshold requirements within the available budget and schedule.

2.45 In early 2014 Defence amended the requirements for the Hawkei in a number of areas as a result of the 2012–13 testing, notably:

- the maximum weight for helicopter airlift was raised from 7000 to 7600 kilograms26;

- the crew requirement for the Reconnaissance vehicle was reduced from five to four, to allow room for equipment and a gunner’s platform;

- the reliability requirement (Mean Time Between Critical Failures) was reduced—from 10 000 kilometres at a 90 per cent lower confidence level to 6000 kilometres at an 80 per cent lower confidence level—so as to make it ‘more achievable and testable’; and

- delivery of the Integral Computing System would be completed by Final Operational Capability (2023).27

2.46 The Defence Materiel Organisation rated the Hawkei’s survivability and reliability as medium technical risks, and rated the design maturity as a high schedule risk. Defence paid Thales $7.3 million in capability incentive payments for the 2012–13 development activities, while withholding $336 000.

2.47 In April 2014, the Defence Science and Technology Organisation provided a Technical Risk Assessment of the Hawkei, finding that a stable design had not yet been achieved. The overall technical risk was assessed as high, and a number of specific areas were assessed as continuing to be high-risk.

2.48 In August 2014, during the Risk Reduction Activity, the DSTO conducted a further landmine test on a reworked Hawkei Utility. The vehicle passed the test.

2.49 In November 2014, the DSTO provided a second Technical Risk Assessment of the viability of the Hawkei project, based on the requirements as revised earlier in the year and the results of the Risk Reduction Activity. The DSTO found that the overall technical risk for the Hawkei was now medium, with a stable design expected to be achieved in another design iteration after Second Pass. The DSTO noted that:

- a detailed reliability test program had been developed;

- a blast retest had been successful; and

- Defence had decided that delivery of the Integral Computing System would be completed by Final Operational Capability (2023).

2.50 At the end of the Risk Reduction Activity, in November 2014, Defence found that Thales had achieved 62 per cent of the total requirements, as shown in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Achievement of design requirements for the Hawkei by end of 2014

|

Requirement rating |

Number of requirements |

Achieved by end of 2014 |

Percentage achieved |

|

Threshold (minimum) |

425 |

329 |

77.6 |

|

Objective (preferred) |

208 |

64 |

30.8 |

|

Total |

633 |

393 |

62.1 |

Source: Adapted from Defence, Contract Performance Assessment Report, November 2014.

2.51 Defence paid Thales $1.6 million in capability incentive payments, while withholding $131 000 because Thales did not achieve four of 52 requirements. By the end of 2014, Thales had been paid $58.5 million for development of the Hawkei design.28 As a result, the Commonwealth has Intellectual Property ownership rights in the vehicle and will receive a royalty payment from any export sales. Thales advised the ANAO that it contributed $34.5 million in self-funded Research and Development on the Hawkei project and a further $21.4 million to prepare production facilities and systems at its Bendigo facility for Hawkei production.

2.52 In November 2014, Thales had indicated to Defence its willingness to commit funding for further development to meet the reliability requirements. Defence advised the ANAO that Thales conducted a $16 million Hawkei Pilot Readiness Program during 2015. One key planned outcome was improved vehicle reliability, for which Thales budgeted $505 000. Thales conducted some further predictive analysis of reliability (see paragraph 2.32), and later included the costs of this development work in its acquisition contract pricing as reimbursement for costs incurred.

2.53 In September 2015, just after Second Pass, Defence conducted a further technical review of the Hawkei, focusing on the reliability of 13 subsystems. Defence had identified that Thales was modifying or replacing several subsystems that had previously passed test and evaluation, and that this might impact the known reliability proven in earlier test activities.29 The review concluded that several subsystems had not been verified under trial on current Hawkei platforms, but that the design of these subsystems was considered mature. Overall, the review rated reliability as a medium risk.

2.54 Defence conducted further test and evaluation activities after signing the acquisition contract for the Hawkei in October 2015. These activities were ongoing as at July 2018.

3. The procurement process (First Pass and development contracts)

Areas examined

This chapter examines Australia’s participation in the United States JLTV Program, development of a Manufactured and Supported in Australia option, and Defence’s advice to the Government at First Pass and Interim Pass.

Key findings

At First Pass in 2008, a financial partnership with the United States in its JLTV Program was adopted as the primary acquisition strategy, at a cost of $43 million. In 2009, Defence sought approval to commence a parallel investment in Australian-based options that it had previously decided to be high-risk and high-cost. At Interim Pass in December 2011, Defence recommended and received approval for further development of the Thales Hawkei, because Defence considered it had the best prospect of meeting future needs, despite assessing it as the least developed Australian option. At the same time, Australia’s financial partnership in the JLTV Program was discontinued amidst uncertainty as to the program’s future, but it was retained as a possible alternative option for Second Pass. Within days of the Interim Pass decision, the United States decided to continue the JLTV Program. Defence did not reconsider its Interim Pass recommendations in the light of this significant change. The 2011 decision to discontinue Australian financial participation in the JLTV Program eroded Defence’s ability to benchmark its procurement of the Hawkei against a comparable vehicle. In the absence of reliable benchmark information, there was a reduction in Defence’s ability to evaluate whether procurement of the Hawkei clearly represented value for money.

3.1 The previous chapter focused on test and evaluation activities up to 2014. This chapter considers Defence procurement processes during the same developmental stages:

- First Pass to Interim Pass (2008–11); and

- Interim Pass to Risk Reduction Activity (2011–14).

Did Defence conduct effective procurement processes during the development stages up to Interim Pass (2008–11)?

At First Pass in 2008, Defence adopted what it considered the least risky option of partnership in the United States JLTV Program, at a cost of $43 million, while also retaining the option of a military-off-the-shelf option. After extensive industry lobbying, Defence sought approval to commence a parallel investment in Australian-based options that it had previously decided to be high-risk and high-cost and had not presented for government consideration at First Pass.

Between July and November 2011, Defence received strong indications and advice from the United States Government that the JLTV Program was likely to experience lengthy delays, and possibly be cancelled. In November 2011, the Defence Minister directed that no further Australian investment in the program be made without his approval.

First Pass decision: Australia participates in a United States development program

3.2 During 2007–08, Defence considered four options for filling its capability shortfall:

- Option 1: a military-off-the-shelf vehicle;

- Option 2: a next-generation (developmental) vehicle;

- Option 3: the United States Joint Light Tactical Vehicle through a Foreign Military Sales agreement; or

- Option 4: the United States Joint Light Tactical Vehicle by becoming a partner nation.30

3.3 Defence estimated that a military-off-the-shelf vehicle or the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle would cost some $1.2 billion to $1.3 billion, while a developmental option would cost some $1.9 billion. Defence considered that the previous tender process for Land 121 Phase 3 had confirmed that there were no Australian military-off-the-shelf manufacturers of the capability sought, and that the focus of Australian industry involvement would be in through-life support.

3.4 Defence decided to present Options 1 and 4 to the Government. This recommendation accorded with the findings of reviews that had suggested a reduced proportion of unique Australian solutions for Defence projects.31

3.5 At First Pass in October 2008, Defence advised the Government that its preferred option was participation in the JLTV Program, which was seeking to acquire vehicles closely aligning with Defence’s requirements. Defence expected that Australian specifications (such as right-hand drive) could be included in the design and that it could achieve timely access to the production schedule and an exemption from Foreign Military Sales fees. This was also expected to help reduce sustainment costs.

3.6 The Government noted Defence’s advice that:

- committing funding upfront minimised project risk, in keeping with the Defence Procurement Review 2003 (Kinnaird Review);

- the high production numbers of Joint Light Tactical Vehicles would reduce Australia’s costs through economies of scale; and

- Australia would gain invaluable knowledge and expertise during the JLTV Program’s Technology Development phase.

3.7 In respect to a potential Australian-led developmental solution, which was considered but not presented to Government, Defence advised the Government that the cost involved in pursuing a unique design was around 50 per cent more than Options 1 and 4. An Australian developmental program would also take at least six years and present significant schedule and technical risks.

3.8 On 1 October 2008, the Government gave First Pass approval for Australia’s participation in the Technology Development phase of the JLTV Program. The Government decided that, once it became clear whether the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle would be cost-effective, Defence should return for Interim Pass government approval in early 2010, and then either continue to participate in the JLTV Program, or release a market solicitation for a current-generation (military-off-the-shelf) vehicle.

3.9 Australia became a participant in the JLTV Program in January 2009, at a cost of A$43 million. The United States committed up to A$286 million to the program’s development.32 Defence records indicate that Australia’s involvement in the program directly influenced the United States to incorporate many requirements considered important to Australia.

Parallel Australian development

3.10 Defence records indicate that Thales conducted ‘extensive lobbying’ between late 2008 and early 2009, submitting an unsolicited proposal to the Victorian and Australian Governments for an Australian developmental option.33 On 26 November 2008, the Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Procurement wrote to Defence asking if Defence had considered issuing a Request for Information to Australian companies capable of producing a light protected vehicle.

3.11 Defence estimated the acquisition costs for an Australian developmental option as $2 billion, around $700 million more than the two options presented at First Pass. In-service costs for the developmental option were expected to be 20 per cent to 100 per cent greater than a military-off-the-shelf capability or the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle.

3.12 Defence sought the Government’s approval for a Request for Proposal for an Australian developmental option. When approving the issue of a Request for Proposal in February 2009, the Minister for Defence noted that Defence’s advice went against advice from previous reviews into Defence procurement:

Reluctantly agreed. This flies in the face of Pappas/Mortimer. What expectation will it raise? It also appears counter-intuitive, given we would be more reliant on the contingency provision if we go down a development path.

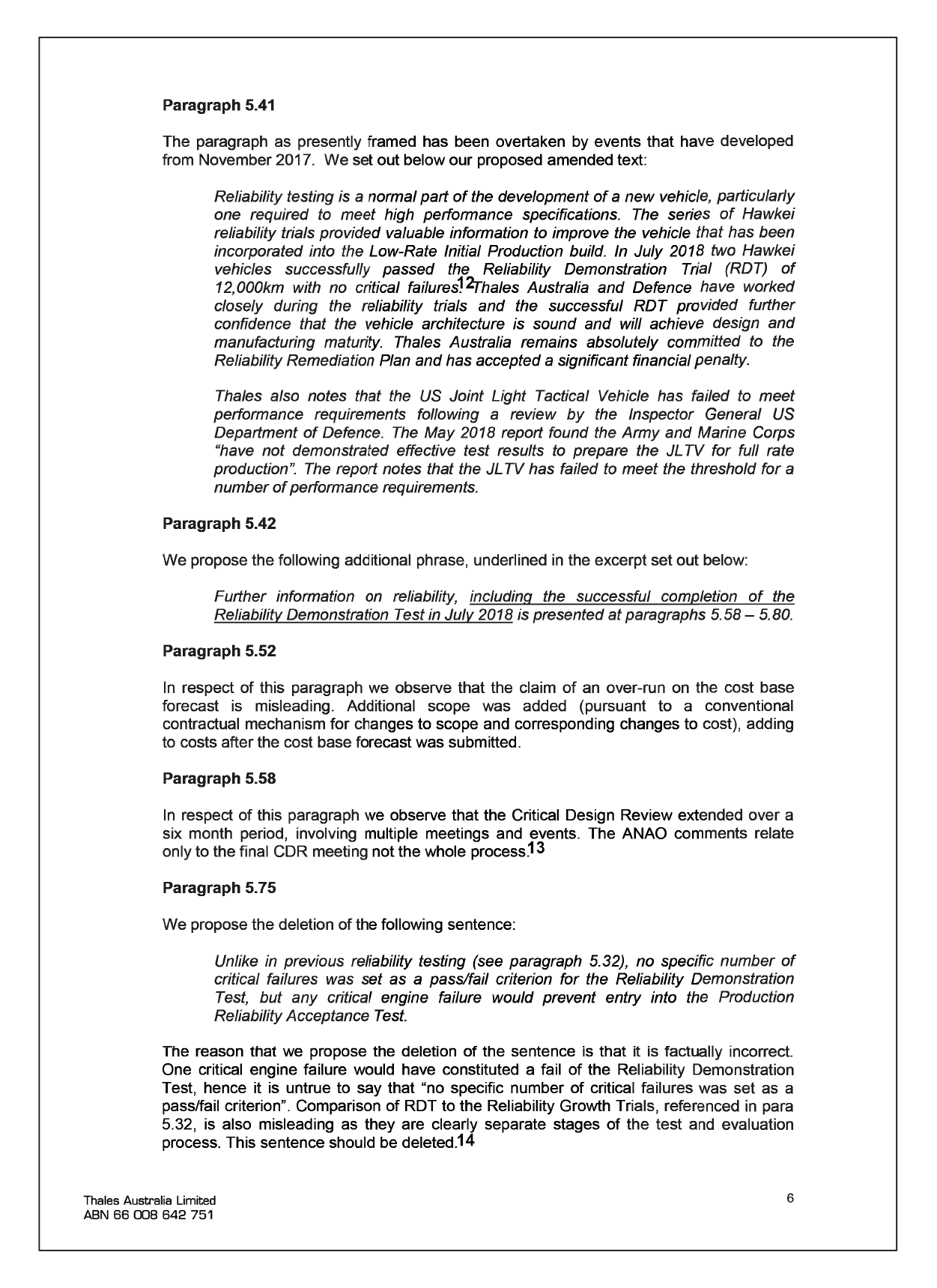

Figure 3.1: The Oshkosh L-ATV, selected as the United States Joint Light Tactical Vehicle in August 2015

Source: Oshkosh Defence. Wikipedia Free License CC by-SA 4.0.

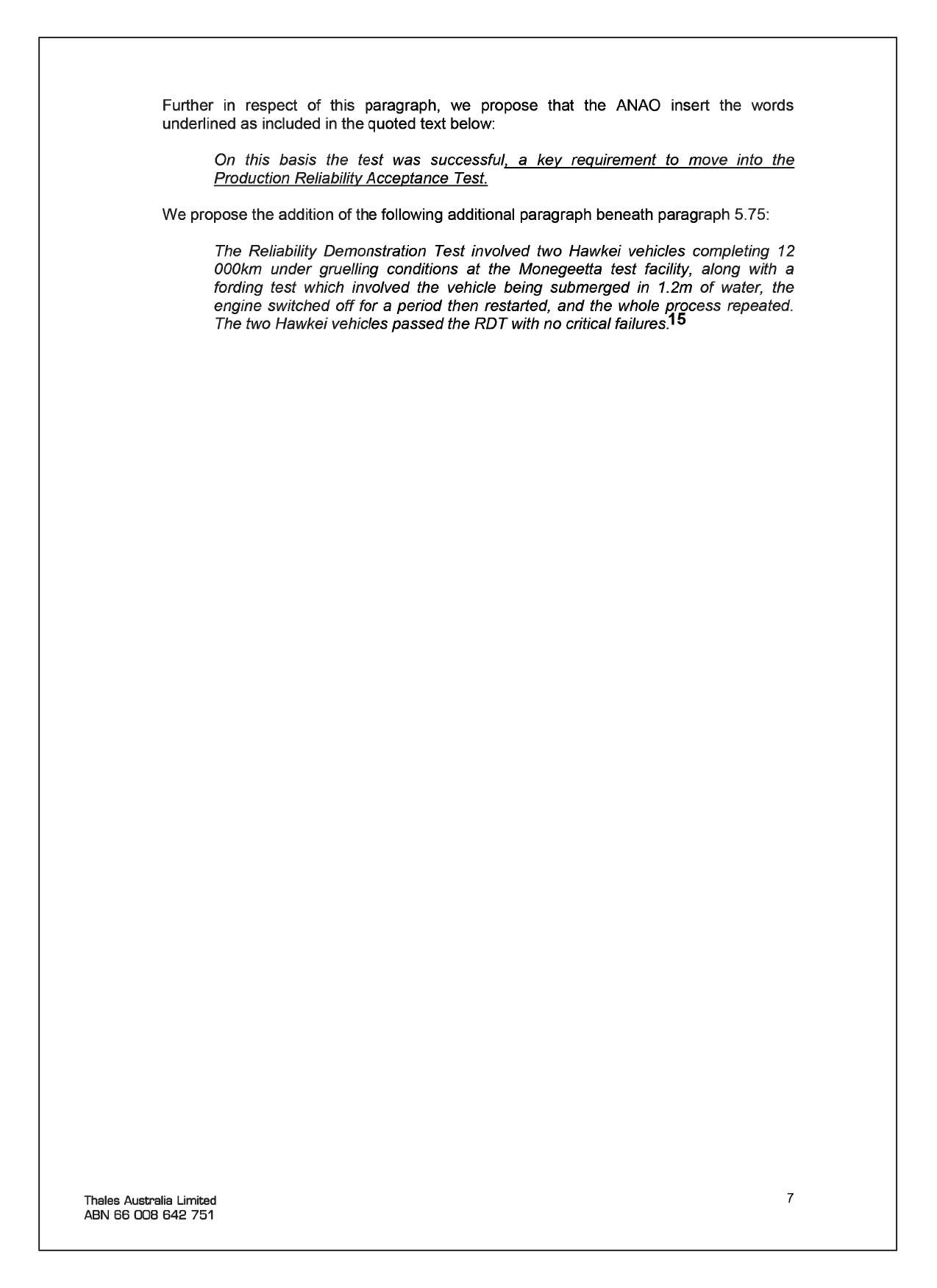

Figure 3.2: The Thales Australia Hawkei, selected as the Australian Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light in August 2015

Note: Like the Oshkosh vehicle shown above, the Hawkei has a Remote Weapon Station capability, but purchase of these systems is not part of the vehicle acquisition.

Source: Defence.

3.13 On 18 March 2009, the Defence Minister announced that the Defence Materiel Organisation intended to release a Request for Proposal for an Australian option the following month. On 2 April 2009, the Minister sought prime ministerial approval for a Request for Proposal for a vehicle ‘Manufactured and Supported in Australia’. The Prime Minister approved the request in June 2009, with a number of caveats, noting that the Minister for Finance had advised that any such proposal was likely to adversely impact the project’s cost, technical and schedule risks, but that the Request for Proposal had already been publicly announced by the Defence Minister. The Prime Minister capped expenditure on the Request for Proposal at $0.5 million, and asked the Minister for Defence and the Minister for Finance to jointly assess the industry responses.34

Defence’s assessment of the Request for Proposal responses

3.14 From September 2009 to February 2010, Defence evaluated the industry responses to its Request for Proposal.35 Of the three proposals evaluated, Defence assessed two proposals as technically strong and offering no significant technical risks, while it assessed the Thales proposal as technically strong but high-risk, because of the developmental nature of the vehicle and non-compliance with protection requirements.

3.15 When value-for-money considerations were applied, Defence ranked the Thales proposal equal second, on the basis that:

[Company A] offer a MOTS [military-off-the-shelf] based solution with low technical, schedule and cost risk compared with Thales’ solution offering a fully developmental proposal with associated high levels of technical, schedule and cost risk.

Without the level of detail an RFT [Request for Tender] solicitation would provide, the evaluation team has no option but to rank these two proposals as equal VFM responses.

3.16 Defence advanced all three contenders to the next stage of development.

3.17 Defence did not carry out the Prime Minister’s June 2009 request that the Minister for Defence and the Minister for Finance should jointly assess the Request for Proposal (see paragraph 3.13).

3.18 In a further letter to the Minister for Defence in May 2010, the Prime Minister noted:

I am advised there is little evidence to suggest that the MSA [Manufactured and Supported in Australia] proposals are likely to represent better value for money, a higher level of capability or a lower risk profile than is offered by the JLTV program.

The JLTV program has had the benefit of 5 years and around $300 million invested in prototype development. In contrast, Thales as the only Australian-designed MSA option, assures Defence that it can produce a prototype in 9 months (having requested $33 million for six vehicles), although Defence intends to provide it with only $9 million. On this basis it is difficult to see that there can be a legitimate competition between these two options.

3.19 Notwithstanding these concerns, the Prime Minister authorised expenditure of $30 million for prototyping activities for the Manufactured and Supported in Australia option.

The first development contracts: Defence ranked Thales third at the technical level, but first in terms of value for money

3.20 In July 2010, Defence signed Manufactured and Supported in Australia development contracts, to a value of $9.9 million each, with three companies, as shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Participants in Manufactured and Supported in Australia Stage 1

|

Company |

Proposed manufacturing location |

|

Force Protection Europe |

Mawson Lakes, South Australia |

|

General Dynamics Land Systems–Australia |

Adelaide, South Australia |

|

Thales Australia |

Bendigo, Victoria |

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

3.21 Each company delivered two prototypes on 23 February 2011, and testing concluded on 29 June 2011.36 At the technical level, Defence ranked Thales third, because ‘overall the Thales solution did not comply with the majority of the Commonwealth specification and the supporting documentation provided was significantly deficient’. The company’s ‘immature design and development program’ therefore presented high cost, schedule and technical risk, while the ‘substandard quality of their technical documents’ left Defence with low confidence in Thales’ ability to comply with the requirements. Defence had ‘no certainty’ that the final Thales product would fully meet its requirements, and added that:

if the Commonwealth considers avoiding high risks to cost, schedule and capability, then it is not recommended to proceed with the Thales solution.

3.22 For the other companies assessed, one had a critical deficiency in respect of payload, and the other in respect of landmine protection, and Defence considered that each would require significant engineering development.

3.23 Defence ranked Thales first in terms of value for money, based on Thales having:

a reasonable prospect for further development and a likelihood to result in Value for Money consistent with Commonwealth purchasing policies and the Evaluation Criteria.

3.24 Defence judged that Thales’ significant deficiencies and the risk in its ability to successfully manage and deliver quality project and technical documentation could be managed effectively by strong Commonwealth guidance and management.

3.25 Defence noted that all three vehicles in the Manufactured and Supported in Australia process were unaffordable under the existing budget provision, but considered that the development of more accurate and comprehensive pricing, combined with capability trade-offs and potential Basis of Provisioning reductions, might make the overall proposal affordable.

Joint Light Tactical Vehicle Program uncertainty during 2011

3.26 The United States JLTV Program was scheduled to progress to the Engineering and Manufacturing Development phase in September 2011. In the lead-up to this phase, Australia considered whether to continue as a partner in the United States program.

3.27 In June 2011, Defence considered that there was a compelling case for Australia to continue its partnership status in the United States program, because it offered significant schedule, capability and cost advantages—including that it was considered the lowest technical risk and most affordable of all the options for a Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light.

3.28 From July to November 2011, there were strong indications and advice from the United States Department of Defense that the JLTV Program was likely to be significantly delayed or cancelled.37 The program’s uncertain status caused Defence to refrain from seeking Australian Government approval to commit to the next phase of development. In November 2011, the Australian Minister for Defence directed Defence to make no further financial commitment to the JLTV Program without his express approval.

Did Defence conduct effective procurement processes from the lead-up to Interim Pass until Second Pass (2011–14)?

At Interim Pass in December 2011, Defence recommended, and received approval for, the Thales Hawkei as the primary Australian acquisition option following the Stage 1 test and evaluation process conducted during 2010–11. Defence considered that this design had the best prospect of meeting future needs, although it was the least developed Australian vehicle design. Defence noted that all three Australian options it had tested exceeded the project’s budget. Defence did not make the Government aware of the results of an economic study it commissioned that found there would be limited regional economic benefits from, and a substantial premium paid for, the Hawkei build.

Defence records indicate that a significant driver of the Hawkei project schedule was the retention of production capacity at Bendigo after Bushmaster production ceased in late 2016. Defence recommended further production of Bushmasters at Bendigo to keep the facility in operation pending possible Hawkei approval. This was funded at a cost of $221.3 million, representing more than a ten per cent increase to Defence’s expenditure related to acquiring the Hawkei capability. This expenditure was not taken into account in assessing the overall cost and value for money of the Hawkei project at Second Pass.

Defence did not reconsider its Interim Pass recommendations after new and potentially material information became available regarding the JLTV Program soon after Interim Pass governmental approval, and did not seek ministerial approval to continue Australian participation in the JLTV Program. The decision not to seek ministerial approval to continue in the JLTV Program reduced Defence’s ability to benchmark its procurement of the Hawkei and apply competitive pressure, and together with the decision not to factor-in related expenditure, reduced Defence’s ability to evaluate whether procurement of the Hawkei clearly represented value for money.

3.29 Defence developed three business case options to inform Defence considerations prior to Interim Pass. These business cases considered:

- Hawkei alone, $54 million: Defence observed that this option would ‘eliminate the unnecessary development, support and expense of other options’. Key disadvantages were the risks to cost, schedule and capability from a developmental vehicle; and the lack of competitive tension.

- Hawkei and another Australian contender, $74 million: Defence noted that this option was affordable and maintained competitive pressure.38

- Joint Light Tactical Vehicle, $71 million (in addition to Hawkei): Partner status would give Australia the ability to influence requirements, receive right-hand-drive prototypes and integrate Australian computer and communications systems, and would make this acquisition $65.1 million less expensive than through a Foreign Military Sales case.

3.30 Defence adopted the Hawkei option as its preference, observing that:

The existence of competitive tension, although beneficial, means that a full partnership with each Participant is not possible which may result in a reduced ability by the project office to resolve technical design issues.