Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

ANZAC Class Frigates — Sustainment

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The audit objective was to examine whether the Department of Defence has effective and efficient sustainment arrangements for the Royal Australian Navy’s fleet of eight ANZAC class frigates.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Royal Australian Navy (Navy) operates eight ANZAC class frigates. The frigates were commissioned between 1996 and 2006, and form part of Navy’s core surface warship capability. The ANZAC class is used to: conduct surveillance and patrols; protect shipping and strategic areas; provide naval gunfire in support of the Army; and undertake disaster relief and search and rescue activities.

2. The ANZAC class is half way through its original service life-of-type. The first frigate was expected to be withdrawn from service during 2024–25 and the last during 2032–33. In June 2018, the Australian Government announced that Hunter class frigates (under the SEA 5000 program) would replace the ANZAC class of ships, with the first Hunter class frigate scheduled to enter service in the late 2020s.1 To accommodate the design, build and introduction into service of the Hunter class frigates, the ANZAC class’ original withdrawal dates have been extended, with the first frigate to now be withdrawn in 2029–30 and the last in 2042–43.

3. The Department of Defence’s (Defence) Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group is responsible for the sustainment of the ANZAC class. Navy has advised the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group of its requirements and budget for the sustainment of the ANZAC frigates in a Materiel Sustainment Agreement. The budget for the sustainment of the eight ANZAC class frigates for 2018–19 is $374.0 million — 15 per cent of Navy’s overall sustainment budget of $2,422.4 million for that year. The approved budget to sustain the ANZAC class from 2018–19 to 2026–27 is $3.4 billion.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. Defence’s sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates was selected for audit due to its cost and the importance of this capability until the Hunter class frigates enter into service. In addition, parliamentary committees have, over several years, stated their interest in Defence’s reporting of its sustainment performance and, in particular, obtaining greater insight into that performance.2

5. This audit is the fourth in a series of performance audits of Defence’s management of materiel sustainment:

- Auditor-General Report No.44 2017–18 Defence’s Management of Sustainment Products — Health Materiel and Combat Rations;

- Auditor-General Report No.2 2017–18 Defence’s Management of Materiel Sustainment; and

- Auditor-General Report No.30 2014–15 Materiel Sustainment Agreements.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit objective was to examine whether the Department of Defence has effective and efficient sustainment arrangements for the Royal Australian Navy’s fleet of eight ANZAC class frigates.

7. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence has a fit-for-purpose sustainment framework between Navy and the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.

- Defence has an appropriate framework to monitor and report on the effectiveness and efficiency of operating the ANZAC fleet.

- Defence effectively administers the ANZAC sustainment strategic partnership to achieve specified availability and performance outcomes.

Conclusion

8. While the ANZAC class frigates are meeting Navy’s current capability requirements and continue to be deployed on operations in Australian, Middle Eastern and Asia-Pacific waters, Defence has been aware since at least 2012 that sustainment arrangements have not kept pace with higher than expected operational usage. Further, Defence cannot demonstrate the efficiency or outcomes of its sustainment arrangements, as the necessary performance information has not been captured. Defence will need to address relevant shortcomings in its sustainment arrangements to meet the requirement that the ANZAC class remain in service for an extra 10 years to 2043, pending the entry into service of the replacement Hunter class.

9. The effectiveness of Defence’s framework for sustaining the ANZAC class frigates has been reduced because the sustainment plans and budget outlined in the ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule in Navy’s Materiel Sustainment Agreement do not align with the frigates’ higher than expected operational use. Defence has been aware of this misalignment since at least 2012.

10. Defence’s advice to the government to extend the ANZAC class’ life-of-type to 2043 was not based on a transition plan or informed by an analysis of the frigates’ physical capacity to deliver the required capability until then. Navy will need to address potential risks, relating to the frigates’ material condition, to maintain seaworthiness and capability.

11. Defence has established a performance framework for the ANZAC class frigates’ sustainment, with performance measures included in the Materiel Sustainment Agreement and reports provided to senior Defence leaders. While the performance measures adopted by Defence are relevant, the performance framework is not fully effective because the performance measures are:

- only partially reliable — as targets and/or plans regularly change; and

- not complete — as the measures do not address sustainment outcomes and efficiency.

In 2017–18 most of the Key Performance Indicators reported against were consistently not met.

12. The transparency of external reporting on the ANZAC frigates’ sustainment expenditure is reduced as it does not include Defence staffing costs or operational sustainment expenditure.

13. Defence entered into a sole sourced alliance contract with its existing industry partners, without a competitive process.

14. It is too early to assess the effectiveness of Defence’s administration of the new contracting arrangements, known as the Warship Asset Management Agreement, which took full effect in January 2018 after an 18-month transition period. Defence’s regular internal performance reporting and monitoring does not capture the performance of the Agreement.

Supporting findings

Sustainment framework

15. The ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule in Navy’s Materiel Sustainment Agreement established with the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group is not fit-for-purpose. Navy has not updated the document to reflect the current governance arrangements and sustainment needs. The current sustainment plan and available budget do not accurately reflect the operational use of the frigates, which is higher than planned.

16. The misalignment between operational use and sustainment funding, combined with difficulties in securing necessary parts (in part, a result of obsolescence), has caused Defence to defer maintenance activities and transfer items of equipment between frigates.

17. Defence has identified the effects of the current misalignment between sustainment planning, funding and actual operational use. The ANZAC class has experienced degradation of the ships’ hulls and sub-systems, with successive reviews and performance information highlighting the link between lack of conformance to operating intent/requirement, reduced platform life and reduced sustainment efficiency.

18. In June 2018, Defence advised the Government of its intention to extend the planned withdrawal from service of the ANZAC class to 2043, indicating that a transition plan was due for completion in late 2019. The advice did not address the misalignment or assess the ANZAC class’ physical capacity to deliver the required capability until 2043. Defence is preparing a transition plan, which is due to be completed in late 2019, to guide the transition from the ANZAC class to the replacement Hunter class.

Performance monitoring and reporting

19. The performance measures adopted for the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates are relevant but only partly reliable, as targets and/or plans regularly change. Further, the performance measures are not complete, as they do not address sustainment outcomes or efficiency.

20. Defence has established arrangements to monitor and report on the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates, with senior Defence leaders made aware of the sustainment risks and issues experienced by the ANZAC class. The performance reporting indicates that there was underperformance for most of the Key Performance Indicators for the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates during 2017–18. External reporting on the ANZAC class frigates’ sustainment expenditure would be more transparent if it included Defence staffing costs and operational sustainment expenditure.

Administration of the sustainment strategic partnership

21. Defence entered into a sole sourced alliance contract (the Warship Asset Management Agreement) with its existing industry partners, under an exemption from the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

22. In the absence of a competitive process, Defence determined that value-for-money had been achieved after considering cost, the expertise of the industry partners, and their previous experience in sustaining the ANZAC class.

23. It is too early to assess the effectiveness of the contracting arrangements for ANZAC class sustainment, which took full effect in January 2018 after an 18-month transition period. The strategic partnership arrangement is expected to: drive efficiency; transfer risk to industry; reduce Defence’s cost of ownership; simplify contract administration; and reduce contract disputes. However, the arrangements may reduce Defence’s leverage over industry participants.

24. Defence entered into the new sustainment contract without seeking endorsement from the Defence Investment Committee or the Minister for Finance, on the assumption that ANZAC class sustainment had been approved at the time of the ships’ acquisition in the 1980s or possibly when they were introduced into service in the 1990s. Defence should have sought advice from central agencies on the most appropriate handling of this matter, given the high value of this procurement and the uncertainty over past approvals.

25. Defence’s regular internal performance reporting and monitoring does not capture the performance of the Warship Asset Management Agreement. The current misalignment of performance measures in the Warship Asset Management Agreement with the framework set out in the ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule of the Materiel Sustainment Agreement may result in a lack of clarity around the achievement of outcomes.

26. Defence’s initial assessment of the performance of the Warship Asset Management Agreement indicates that all measures had been met or exceeded as at late 2017. Defence plans to evaluate the value-for-money of its contracting arrangements in 2020.

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.25

Defence update the ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule of the Navy Materiel Sustainment Agreement to align sustainment plans for the ANZAC class frigates with their operational use and material condition.

Department of Defence response: Agree.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.48

In the context of developing its transition plan for the ANZAC class life-of-type extension, Defence review the capital and sustainment funding required to maintain the ANZAC class frigate capability until 2043, and advise the Government of the funding required to meet the Government’s capability requirements for the class or the capability trade-offs to be made.

Department of Defence response: Agree.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.10

Defence review the key performance measures for the ANZAC class frigates’ sustainment to ensure they are reliable and complete.

Department of Defence response: Agree with qualification.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 4.21

To align with the strategic planning approach outlined in the Defence Integrated Investment Program, Defence develop guidance in the Capability Life Cycle Manual on when a proposal to establish or amend a sustainment program should be provided to the Defence Investment Committee and the Minister for Finance for consideration.

Department of Defence response: Agree with qualifications.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.33

Defence refine its performance reporting and management arrangements for the ANZAC class frigates by aligning Key Performance Indicators in the Warship Asset Management Agreement and those in the ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule of the Navy Materiel Sustainment Agreement.

Department of Defence response: Agree.

Summary of the Department of Defence’s response

27. The proposed audit report was provided to the Department of Defence, which provided a summary response that is set out below. The letter of response is reproduced at Appendix 1.

Defence welcomes the ANAO Audit Report into the ANZAC Class Frigates - Sustainment and agrees with the recommendations. Recommendations three and four have been agreed with qualifications.3

Defence would like to highlight the reliable performance and operational effectiveness of the ANZAC Class Frigates, and their ability to consistently achieve whole of government requirements during the previous two decades. Throughout the life of the ANZAC Class Frigates, Defence has effectively managed upgrades and subsequent sustainment of these warships in order to achieve the strategic requirements that have evolved since the introduction of the capability.

Defence is confident the assurance provided through this Seaworthiness regime affirms the warships are operational, seaworthy and capable of performing all assigned tasks. Furthermore, Defence is continually assessing options to optimise sustainment funding for the ANZAC Class Frigates to ensure operational availability and effectiveness continues to be met.

The Warship Asset Management Agreement (WAMA) has seen the implementation of greater cost oversight and improved performance based measures that encourage collaborative behaviours and a solutions focus within the industry partners. In line with the First Principles Review, the WAMA seeks to support long term relationships with industry that will underpin the sovereign capabilities essential to deliver continuous shipbuilding and sustainment.

Defence is actively planning and making preparations for the transition from the ANZAC Class Frigates to the Hunter Class Frigates to ensure effective operational coverage in a complex and ever changing strategic environment.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

28. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

Program implementation

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Royal Australian Navy (Navy) consists of around 46 commissioned vessels and over 14,000 personnel. Navy’s core surface warship capability includes eight ANZAC class frigates (FFH — frigate helicopter) which were commissioned between 1996 and 2006.4 The frigates were based on the German Meko 200 design and were built by Tenix Defence (now BAE Systems) at the Williamstown shipyard in Melbourne.5

Figure 1.1: HMAS Stuart (FFH-153), Navy ANZAC class frigate

Source: Navy.

1.2 The ANZAC class is a long-range frigate and is used to: conduct surveillance and patrols; protect shipping and strategic areas; provide naval gunfire in support of the Army; and undertake disaster relief and search and rescue activities. Since their introduction into service, each frigate has undertaken multiple deployments, including to South East Asia, the Middle East and the Pacific. Appendix 2 outlines key deployments and dates for each of the eight frigates.

1.3 The ANZAC class is half way through its original service life-of-type. The first frigate was expected to be withdrawn from service during 2024–25, with the last frigate to be withdrawn during 2032–33. In June 2018, the Australian Government announced that the Hunter class frigates (under the SEA 5000 program) would replace the ANZAC class of ships, with the first Hunter class frigate to enter service in the late 2020s.6 To accommodate the design, build and introduction into service of the replacement Hunter class frigates, the ANZAC class’ original withdrawal dates have been extended, with the first frigate to now be withdrawn in 2029–30 and the last frigate in 2042–43.

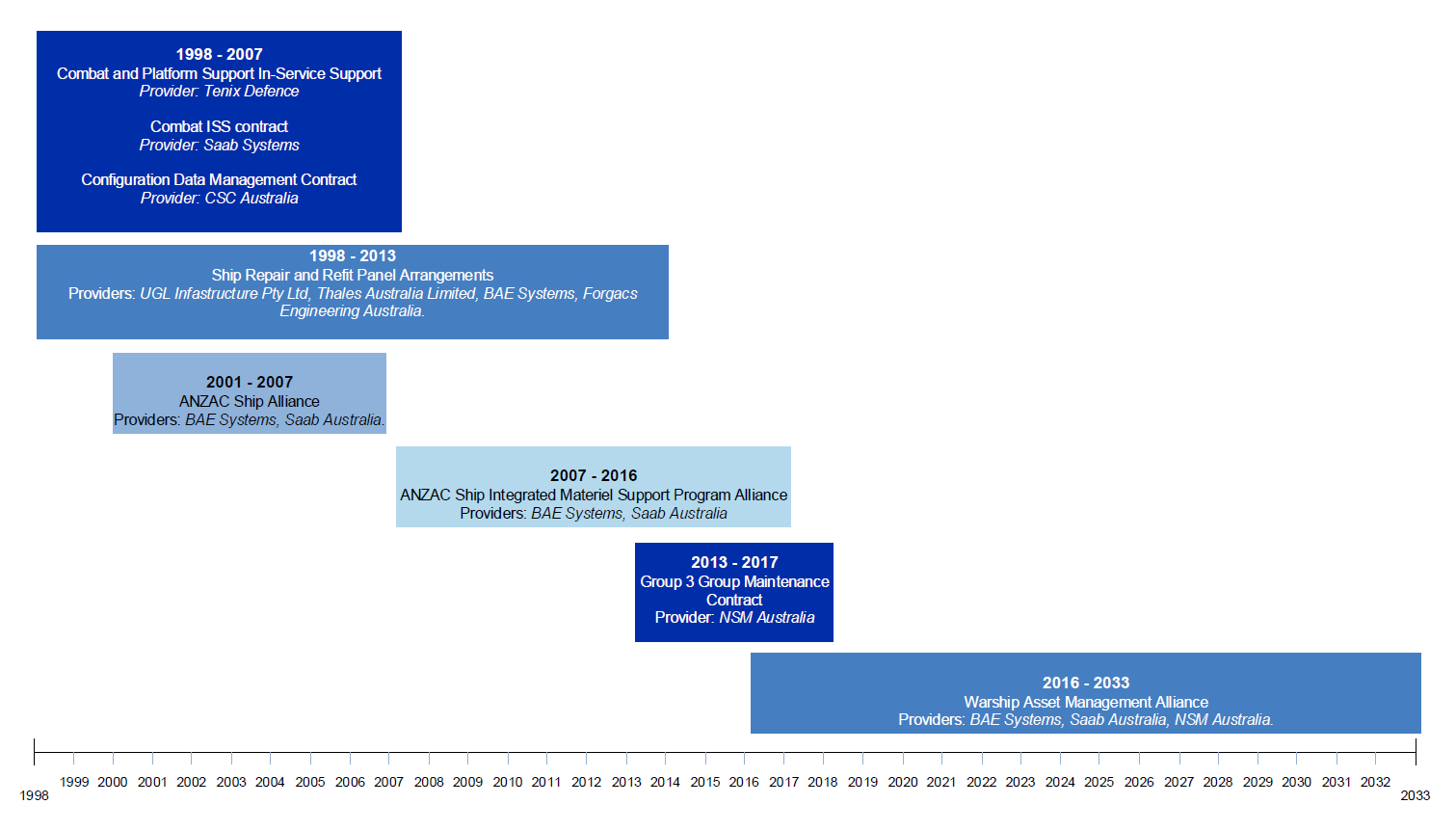

Sustainment arrangements for the ANZAC class frigates

1.4 The ANZAC frigates are a ‘Top 30’ sustainment product for the Department of Defence (Defence).7 In 2017–18, Navy spent $341 million on the sustainment of the ANZAC class, second only to the annual sustainment costs of the Collins class submarines at $622 million. The budget for the sustainment of the eight ANZAC class frigates for 2018–19 is $374 million — 15 per cent of Navy’s overall sustainment budget of $2,422 million for that year.8

1.5 Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) is responsible for the sustainment of the ANZAC class.9 Navy has advised CASG of its requirements and budget for the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates in a Materiel Sustainment Agreement.10 The agreement also sets out the performance information Navy requires to obtain assurance that the ANZAC class frigates are being sustained to meet Navy’s planned operational use of the ships.11

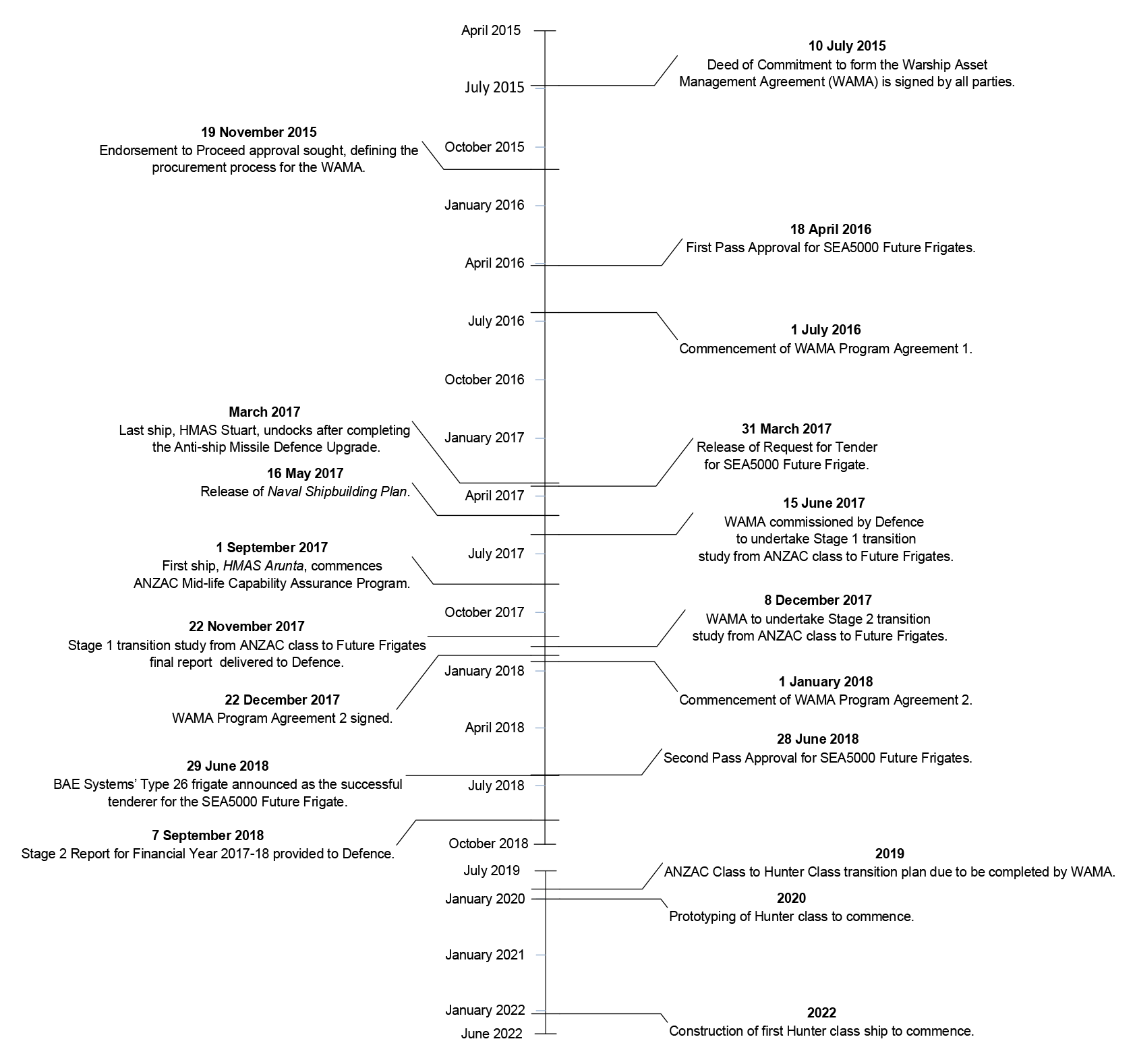

1.6 Within CASG, the ANZAC Systems Program Office has been established to sustain the ANZAC class frigates, including the integration of any changes from Navy capital projects (such as system upgrades) into the ANZAC class frigates. Since the ANZAC class was introduced into service, the ANZAC Systems Program Office has largely outsourced the sustainment of the class to industry.12 In July 2016, Defence contracted BAE Systems Australia, Saab Australia and Naval Ship Management (Australia) to sustain the frigates through the ‘Warship Asset Management Agreement’. Figure 1.2 outlines Defence’s current sustainment arrangements for the ANZAC class frigates.

1.7 As well as routine maintenance activities during deployment, the ANZAC class frigates’ sustainment has included deep-cycle maintenance activities such as:

- upgrading the Anti-Ship Missile Defence systems, including replacement of the mast and radar. The first ship was upgraded in 2010, with the trials completed by mid-2011. The upgrade of the remaining ships occurred between 2012 and 2017; and

- the ANZAC Mid-life Capability Assurance Program. The program began in September 2017 and the final ship is scheduled to be upgraded by 2023. The upgrade is to address obsolescence and incorporate projects SEA 1408 Phase 2 Torpedo Self Defence, SEA1442 Phase 4 Maritime Communications Modernisation, and SEA 1448 Phase 4B Air Search Radar Replacement into the frigates. Figure 1.3 shows HMAS Arunta (FFH-151) undergoing maintenance under the ANZAC Mid-life Capability Assurance Program at the Henderson shipyard in July 2018. A hole has been cut in the port side of the hull to allow for the removal and re-installation of parts and sub-systems.

1.8 Scheduled deep-cycle maintenance programs contribute to the maintenance of and capability and provide an opportunity to assess the material state of the ANZAC class frigates’ hull and sub-systems.

Figure 1.2: Defence sustainment arrangements for the ANZAC class frigatesa

Note a: Several other areas within Defence also contribute to the delivery of ANZAC sustainment, including cross platform products. Additionally, the ANZAC Systems Program Office has several minor supplier contracts with industry.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

Figure 1.3: Access point on the port side of HMAS Arunta’s (FFH-151) hull during maintenance at Henderson shipyard in July 2018.

Source: ANAO site visit to Henderson shipyard — July 2018.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.9 Defence’s sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates was selected for audit due to its cost (as discussed in paragraph 1.4), and the importance of this capability until the Hunter class frigates enter into service. In addition, parliamentary committees have, over several years, stated their interest in Defence’s reporting of its sustainment performance and, in particular, obtaining greater insight into that performance.13

1.10 This audit is the fourth in a series of performance audits of Defence’s management of materiel sustainment:

- Auditor-General Report No.44 2017–18 Defence’s Management of Sustainment Products—Health Materiel and Combat Rations;

- Auditor-General Report No.2 2017–18 Defence’s Management of Materiel Sustainment; and

- Auditor-General Report No.30 2014–15 Materiel Sustainment Agreements.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.11 The audit objective was to examine whether Defence has effective and efficient sustainment arrangements for the Royal Australian Navy’s fleet of eight ANZAC class frigates.

1.12 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence has a fit-for-purpose sustainment framework between Navy and the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.

- Defence has an appropriate framework to monitor and report on the effectiveness and efficiency of operating the ANZAC fleet.

- Defence effectively administers the ANZAC sustainment strategic partnership to achieve specified availability and performance outcomes.

Audit methodology

1.13 This audit focussed on sustainment governance, contract management and performance management arrangements for the ANZAC class frigates. In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- reviewed relevant Defence files and documentation;

- collected and analysed data relating to the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates; and

- interviewed key personnel from Defence and industry, and visited sustainment operations in Western Australia in July 2018.

1.14 The audit examined the current Warship Asset Management Agreement (effective 1 July 2016). The audit did not examine the prior contracts for sustainment services.

1.15 As discussed in paragraph 1.7, the ANZAC class frigates were upgraded as part of the Anti-Ship Missile Defence Project, intended to improve the class’s anti-ship self-defence capability (known as SEA1448 Phase 2A and Phase 2B, with further phases scheduled). This project was not examined as part of the audit.14

1.16 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $451,000. The team members for this audit were Alex Wilkinson, Megan Beven, Zak Brighton-Knight and Sally Ramsey.

2. Sustainment framework

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Defence’s (Defence) framework for sustaining the ANZAC frigates is fit-for-purpose. It considers the Materiel Sustainment Agreement between the Royal Australian Navy (Navy) and the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group; and the alignment between sustainment planning, budget, the operational use of the ships, and their physical condition.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of Defence’s framework for sustaining the ANZAC class frigates has been reduced because the sustainment plans and budget outlined in the ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule in Navy’s Materiel Sustainment Agreement do not align with the frigates’ higher than expected operational use. Defence has been aware of this misalignment since at least 2012.

Defence’s advice to the government to extend the ANZAC class’ life-of-type to 2043 was not based on transition plan or informed by an analysis of the frigates’ physical capacity to deliver the required capability until then. Navy will need to address potential risks, relating to the frigates’ material condition, to maintain seaworthiness and capability.

Areas for improvement

This chapter includes two recommendations intended to improve the sustainment framework by: aligning sustainment plans with the operational use and material condition of the ANZAC class frigates; and reviewing the capital and sustainment funding required to extend the life of the ANZAC class frigate capability until the anticipated withdrawal of the final frigate in 2043.

In addition, consideration should be given to reviewing and updating the documentation underpinning the framework, in particular the Standard Procedure document for Materiel Sustainment Agreements and the Navy Heads of Agreement.

Has Navy established a fit-for-purpose Materiel Sustainment Agreement for managing the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates?

The ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule in Navy’s Materiel Sustainment Agreement established with the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group is not fit-for-purpose. Navy has not updated the document to reflect the current governance arrangements and sustainment needs. The current sustainment plan and available budget do not accurately reflect the operational use of the frigates, which is higher than planned.

The misalignment between operational use and sustainment funding, combined with difficulties in securing necessary parts (in part, a result of obsolescence), has caused Defence to defer maintenance activities and transfer items of equipment between frigates.

2.1 Since 2005, the Department of Defence (Defence) has used Materiel Sustainment Agreements to formalise the relationship between the Services (Australian Army, Royal Australian Navy and Royal Australian Air Force) and Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG).15 As of October 2018, Defence had eight active Materiel Sustainment Agreements. The Royal Australian Navy’s (Navy) agreement had 34 Product Delivery Schedules attached.16 One of these Product Delivery Schedules sets out Navy’s requirements for the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates.

2.2 Defence’s overarching policy on Materiel Sustainment Agreements is set out in the Standard Procedure on Materiel Sustainment Agreements.17 The procedure provides direction on tasks and activities associated with the management of Materiel Sustainment Agreements. First introduced in 2012, the Standard Procedure document had an agreed review period of 12 months. However, as at October 2018, the procedure had not been reviewed. The procedure does not, for example, reflect the organisational governance changes made by Defence following the 2015 Creating One Defence First Principles Review. There would be merit in undertaking the planned review of the Standard Procedure document.

The Heads of Agreement

2.3 The sustainment business model outlined by Navy in its Materiel Sustainment Agreement Heads of Agreement seeks three outputs from CASG:

- materiel availability: the provision of the product for Navy use, at its agreed specification and configuration baseline, and in accordance with seaworthiness and airworthiness requirements.18 Materiel availability addresses the immediate issue of preventative and corrective maintenance that delivers quality Materiel Ready Days19 or their equivalent;

- materiel confidence: contribute to seaworthiness and airworthiness through actions to ensure that the products will remain available at their agreed performance specification through the life of the product; and

- sustainment efficiency: use of the funds available (expenditure against plan to the allocated budget) and the actions to improve cost-effective use of those funds.

2.4 The Navy Heads of Agreement was updated annually until 2012. Since then it has been updated once, in early 2015, to ‘incorporate lessons learned from experience with post-Rizzo [Materiel Sustainment Arrangement] management arrangements.’20 Defence should consider updating the Navy Heads of Agreement to reflect the current departmental structure.

Product Delivery Schedule

2.5 The Product Delivery Schedule (which is attached to the Materiel Sustainment Agreement) identifies: the outputs expected from CASG in terms of the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates; Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators; risks that have the potential to limit the successful achievement of Navy’s three required outputs; and the key requirements and responsibilities of Navy and CASG. For example, CASG is required to deliver:

the cost effective, sustainable and safe:

- maintenance of the product, including sub systems and support systems, through life to the configuration standard and system specifications;

- provision of spares and support to support operations;

- integration of new capabilities and implementation of obsolescence remediation as approved and funded; and

- identification of obsolescence and initiatives to reduce costs over the life of the platform.21

2.6 Delivery of the ANZAC class frigates’ sustainment against the schedule is to be monitored and reported on monthly to an Operational Sustainment Management Meeting through Defence’s Sustainment Performance Management System. Performance measurement and reporting is discussed in Chapter 3 of this Report.

Funding for sustainment activities

2.7 Sustainment funding consists of baseline funding allocated from Defence’s Capability Sustainment Program and operational funding allocated for the additional cost of major Defence operations.22 The approved baseline funding in the ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule does not include the cost of sustainment activities that Navy’s Fleet Support Unit is to deliver as part of the Warship Asset Management Agreement (the WAMA or the Alliance).23

2.8 The Product Delivery Schedule sets out the whole-of-life costing to 2027–28 for the sustainment of the ANZAC class as $3.61 billion. Approved baseline funding set out in the schedule comprises sustainment funding of $3.40 billion until 2027–28 with $374.37 million allocated for 2018–19. The schedule indicates a funding shortfall of $212.92 million for the period to 2027–28.24 Figure 2.1 outlines the estimated required baseline funding, Navy approved baseline funding and cumulative shortfall for ANZAC class sustainment.

Figure 2.1: Estimated required baseline funding, Navy approved baseline funding and cumulative shortfall for ANZAC class sustainment, as at July 2018a

Note a: The ANZAC Mid-life Capability Assurance Program concludes in 2022–23.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

2.9 Defence has identified a need to review these funding arrangements. In the March 2016 fleet screenings25 for ANZAC class sustainment, the Capability Manager for the Surface Combatant group concluded that:

- Without an increase to CN02 [ANZAC class sustainment] funding allocation, the ANZAC class capability will suffer a degradation in system and platform reliability and availability that will impact the lethality at the unit level and inhibit the ability of the FFH [ANZAC class frigate] to meet the requirements of the Navy Warfighting Strategy 2018 through to PWD [planned withdrawal date].

- The significant funding shortfalls across the CN02 [ANZAC class sustainment] PDS [Product Delivery Schedule] across the DMFP [Defence Management and Financial Plan] for sustainment of the ANZAC Class at the current expected level of capability. This under-funding extends to PWD [planned withdrawal date].

- The MEDIUM level of confidence in the sustainment and EC [engineering change] over the forward estimates.

- There is a significant backlog of EC [engineering change] installations as a result of deferrals and prioritisation which now require execution due to sustainment or obsolescence issues reaching critical thresholds. The majority of the ECP [engineering change program] is within the unfunded component of the CN02 [ANZAC class sustainment] budget.

2.10 Subsequent fleet screenings in November 2017 and March 2018 reiterated these conclusions. In July 2018, the life-of-type for the ANZAC class was extended to 2043, over 10 years longer than the original planned withdrawal date (see Figure 2.2 at paragraph 2.41). The planned withdrawal date referred to in the 2016 and 2018 fleet screenings was prior to the extension of life-of-type of the ANZAC class to accommodate the development and build of the replacement Hunter class frigates. In light of the extension, there would be merit in reviewing the ANZAC class sustainment funding estimates. The 2011 Rizzo review, for example, highlighted the need for Defence to consider the increased maintenance costs of a platform towards the end of its life-of-type.26

Operating requirements

2.11 The Product Delivery Schedule records Navy’s materiel requirements including the Product Operating Profile and the Product Activity Plan. The Product Operating Profile describes the employment profiles and Navy’s planned rate of usage, providing the context in which the frigates are used. The Product Activity Plan provides a schedule of monthly Materiel Ready Days27 for each ship for the duration of the Product Schedule, and the maintenance periods necessary to deliver the requirements of the Product Delivery Schedule.28

2.12 The Operating Profile informs CASG’s sustainment planning and the development of costings against the Product Operating Profile. Since June 2012, each financial year’s Product Delivery Schedule for the ANZAC class frigates (the latest update being issued in July 2018) has stated that the Product Operating Profile:

has deviated from the initial functional specification described during the ANZAC Ship Project acquisition phase. As a result the current sustainment plans and budget for the Product does not accurately reflect the current state of operational use.

2.13 The misalignment between operational use and sustainment planning and funding, combined with difficulties in securing necessary parts (in part, a result of obsolescence) has caused Defence to defer maintenance activities and transfer items of equipment between frigates.

Deferral of External Maintenance Period tasks

2.14 In 2015, Navy delayed expenditure on three ANZAC class frigates’ sustainment to address funding pressures. HMAS ANZAC (FFH-150) had $600,000 of maintenance tasks deferred, and HMAS Perth (FFH-157) and HMAS Ballarat (FFH-155) each had $3 million of maintenance tasks deferred. Navy was aware that delaying expenditure on maintenance tasks would ‘result in deferred maintenance creating a large body of outstanding work and associated cost and risk to seaworthiness’.29

2.15 In July 2017, Defence internal reporting identified that:

Maintenance deferrals have at times been conducted without appropriate assessment and approvals. Individually these examples are being addressed; however the sporadic non-compliance with Alliance processes and Defence Policy is considered a risk to seaworthiness for the Class.

2.16 In November 2018, Defence advised the ANAO that ‘all deferred maintenance is subject to individual risk assessments as documented within the ships’ respective Moratorium Letter’. Defence further advised in February 2019 that:

Ship maintenance performance is continuously reviewed jointly by CASG and Navy. Whole of fleet risk is continually assessed, managed and assured under the Navy Seaworthiness regime which considers and addresses individual Class Materiel Mission Risk assessments.

Transfer of items and equipment between frigates

2.17 In 2015, Navy identified that increased use of the frigates had depleted maintenance stocks and the transfer (cannibalisation) of parts from one frigate to service another had increased. In October 2016, the Deputy Chief of Navy was advised by Director General Major Surface Ships and Capability Manager Surface Combatant Group that:

To maintain the current required level of capability for the FFH [Anzac class frigates], it is necessary to transfer items and equipment between platforms. The main reasons for this requirement are: Item is obsolete and no longer available; or Item is not available off the shelf and Procurement lead-time does not meet operational requirement.

2.18 In August 2017, Defence internal analysis identified that for the financial year 2016–17 there had been:

… a decreasing trend for cannibalisations. This is not represented well by the rolling average performance target. A strong correlation exists between peaks in cannibalisation and ships leaving extended maintenance availabilities. The cessation of inventory transfers is resulting in a stabilisation of cannibalisation numbers around the lower level presented here for the past four months… Further improvement will result from continuation of the management plan developed in support of replacing all items cannibalised from HMAS Perth, and analysis to identify causal factors and prevent recurrences.

2.19 In November 2018, Defence advised the ANAO that:

During the Anti-Ship Missile Defence (ASMD) upgrade the number of cannibalisations was large, however it has decreased across the class since the completion of the upgrade program in mid 2017.

… the rate of Cannibalisations has decreased from a monthly average of 17.33 in October 2016 to a monthly average of 3…

2.20 Defence internal reporting in June 2017 identified that the spike in cannibalisations during the Anti-Ship Missile Upgrade program was caused by each successive ship entering the program being ‘used as the next ‘equipment donor’, which represented a risk of cannibalisations increasing towards completion of the program’.

2.21 Table 2.1 shows the reported instances of cannibalisations from 2015–16 to 2017–18.

Table 2.1: Reported instances of cannibalisations, 2015–16 to 2017–18a

|

Financial year |

Number of cannibalisations |

|

2015–16 |

123 |

|

2016–17 |

125 |

|

2017–18b |

67 |

Note a: The ANAO notes that the last ships completed the Anti-Ship Missile Defence Project in 2017.

Note b: HMAS Perth (FFH-157) was in lay-up during 2017–18.

Source: ANAO analysis of monthly reported instances of Sustainment Performance Reporting System results for Key Health Indicator ‘cannibalisation’.

2.22 Box 1 discusses the reasons for cannibalisation in the Defence context and the findings from the United Kingdom National Audit Office’s audit of cannibalisation of naval platforms within the Royal Navy.

|

Box 1: Cannibalisation of naval platforms |

|

The United Kingdom’s National Audit Office undertook an audit of cannibalisation of ships within the Royal Navy. The audit was produced ‘against a background of wider concerns about the affordability of the [Ministry of Defence’s] equipment and support plans, and consideration of the forthcoming changes to how the [Royal] Navy will operate as a myriad of new vessels are brought into service’. The National Audit Office observed that cannibalisation can be an effective way to manage operational and maintenance priorities; however, it can also ‘lead to increased costs and disruption, divert resources from other activities and create additional technical and financial risks.’ The Royal Australian Navy’s Materiel Sustainment Agreement Performance Framework notes that ‘cannibalisation reflects an inability of the supply chain to support requirements’ though ‘is not an indicator of supply chain performance alone as the requirement may be the result of induced failure from a number of domains.’ Defence documentation indicates cannibalisation occurs, for example, when there is: a shortage of available parts or extensive lead times; uncodified items (and not supported by the supply chain); no serviceable stock, with some items unable to be repaired due to funding constraints or repaired by required delivery date; obsolescent parts; and an operational need. The National Audit Office found that:

|

2.23 Navy’s experience from the ANZAC class Anti-Ship Missile Defence upgrade indicated that the cannibalisation of equipment costs up to three times more than undertaking a standard repair methodology such as sourcing a replacement from a supplier or repairing the part.

2.24 The effective sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates until 2043 requires alignment between sustainment plans outlined in the Product Delivery Schedule and the ships’ operational usage and material condition. Defence has been aware, since at least 2012, that the ANZAC class frigates’ sustainment arrangements are not aligned with the ships’ requirements. Defence should update the ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule to help address this misalignment.

Recommendation no.1

2.25 Defence update the ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule of the Navy Materiel Sustainment Agreement to align sustainment plans for the ANZAC class frigates with their operational use and material condition.

Department of Defence’s response: Agree.

Has Defence assessed the effect of the misalignment of the sustainment plans and budget with the ANZAC class frigates’ operational use?

Defence has identified the effects of the current misalignment between sustainment planning, funding and actual operational use. The ANZAC class has experienced degradation of the ships’ hulls and sub-systems, with successive reviews and performance information highlighting the link between lack of conformance to operating intent/requirement, reduced platform life and reduced sustainment efficiency.

In June 2018, Defence advised the Government of its intention to extend the planned withdrawal from service of the ANZAC class to 2043, indicating that a transition plan was due for completion in late 2019. The advice did not address the misalignment or assess the ANZAC class’ physical capacity to deliver the required capability until 2043. Defence is preparing a transition plan, which is due to be completed in late 2019, to guide the transition from the ANZAC class to the replacement Hunter class.

Assessment of condition

2.26 A 2015 Gate Review31 of the ANZAC sustainment operation identified a range of challenges for future support of the ANZACs, including the state of the ships and related assurance processes:

Future support to ANZAC faces a number of challenges, in particular apparently unconstrained budget growth. This budget growth is, at least in part, due to uncertainty regarding the actual materiel state of the ships, concerns with corporate supporting systems that may compromise the assurance of their technical integrity, ongoing upgrade programmes and planned changes to the current operating model.

2.27 Defence is currently determining the state of its ANZAC class frigates through a program of mid-life upgrades to the class. An internal Defence study into the ANZAC class in late 2017 observed that:

Unfortunately, accurate records have not been maintained as to the long-term usage of individual equipment items over the life of each ship nor the stresses to which the hull and other systems have been subjected.32

2.28 Defence records indicate that it was aware prior to the mid-life upgrade that the frigates’ hulls and sub-systems had degraded. For example:

The degraded material state of the vessels has been exposed through the ASMD [Anti-Ship Missile Defence] refit and upgrade. This is particularly evident in the poor condition of the hull and the high growth in corrective maintenance across platform systems and has resulted in a significant maintenance cost increase.33

2.29 Defence identified that the following ‘causal factors’ had contributed to the condition of the ANZAC class ships:

- an inadequate initial sustainment model;

- operating beyond the original Statement of Operating Intent;

- changes to the expected capability;

- additional cost of operating as a ‘parent navy’ for the ANZAC class;34 and

- an increase in required sustainment.

An inadequate initial sustainment model

2.30 In 2015 Defence observed that:

At procurement, the ANZAC Class sustainment model delivered at IIS [introduction into service] has proven to be inadequate to fund the capability and therefore the FFHs [ANZAC class frigates] have been underfunded since IIS [introduction into service]. Navy is continuing to manage the latent symptoms of the behaviours around associated sustainment and capability decisions made over the last 20 years of the life of the ANZAC Class. These are the same behaviours which were highlighted in the Rizzo Review.

2.31 Box 2 summarises the key findings of the 2011 Rizzo Review into ship support and management practices.

|

Box 2: Summary of the findings made in the Rizzo Review regarding the Kanimbla class landing platform amphibious ships |

|

HMAS Kanimbla (L-51) and HMAS Manoora (L-52) were Navy’s Kanimbla class landing platform amphibious ships. The class was subject to high operational tempo and deferred maintenance. These issues, as well as the age of the ships, contributed to the Kanimbla class: accumulating large quantities of corrosion; faults with the deck crane and alarm system; the need to overhaul propulsion machinery, power generators, and air conditioning; and an outdated communication suite. These issues resulted in the Kanimbla class being unable to assist in the aftermath of Cyclone Yasi in 2011 and being decommissioned early due to it being not cost-effective to repair the ships. This diminished Navy’s amphibious and transport capabilities and led to the purchase of interim ships to cover the capability gap. In response to the issues identified in the Kanimbla class ships’ sustainment, the Australian Government commissioned the Plan to Reform Support Ship and Management Practices, commonly referred to as the ‘Rizzo Review’, completed in July 2011. The review made 24 recommendations aimed at improving Navy’s sustainment operations and capability lifecycle management. Importantly the review found: For many years, preventative and corrective maintenance has not been carried out because of the higher priority afforded to operational demands over maintenance requirements. The risks involved in deferring maintenance are not fully appreciated by non-engineering officers in Navy… Failure occurred as a result of Navy systems that are inadequate and under-resourced and cultural difficulties that compromised standards and placed an overwhelming focus on achieving the operational program.35 |

Operating beyond the original Statement of Operating Intent

2.32 The way Defence has operated the ANZAC class frigates since acquisition has increased the usage of systems and equipment beyond the original design intent, accelerating the ageing of the ships systems and increasing early obsolescence. Defence’s monthly internal reporting between 2015–16 and 2017–18 reported performance against the ‘conformance to operating intent’ Key Performance Indicator as ‘red’ for 26 of the 36 months due to operation of the platform outside:

- the operating environment defined in the Statement of Operating intent (for example, outside the design specification for ambient sea water temperatures);

- the operating profile (for example, operating speed) defined in the Statement of Operating intent; and/or

- number of permitted sea days over a two year period.

2.33 The operation of the frigates was considered to be outside the operating intent or design due to:

- a 20 per cent increase in crew size from 157 to 192 and an increased endurance from 30 to 36 days, which had increased the workload on systems including sewage treatment, water generation, refrigeration, power generation and air conditioning;

- an increase in operational tempo from 125 to 150 days per annum, which had increased the running hours of systems;

- variance in operation from the baseline design — the Meko 200 baseline design for the frigates was based on operations in a cool climate and deep water, whereas the ANZAC class frigates have operated for extended periods in warm areas in coastal and archipelagic regions (see Appendix 2); and

- a 50 per cent increase in required power due to modifications made to the ship since introduction into service and major system upgrades.

2.34 Navy internal guidance on the development of performance measures in July 2016 stated that ‘there is a proven link between lack of conformance to operating intent/requirement and reduced platform life/reduced sustainment efficiency’.

Changes to the expected capability

2.35 In November 2015, the Deputy Chief of Navy was advised that:

…additional equipment fits [to the ANZAC class frigates] were not installed under a fully developed engineering change.

2.36 For example, installation of additional systems, such as the anti-ship missile defence system, have increased the frigates’ displacement from 3600 tonnes to 3900 tonnes. As a result, the frigates’ propulsion diesel engines have operated at full power for much longer than originally intended. These additions and operational changes have also increased the cost of ownership. In November 2018, Defence advised the ANAO that:

Additional equipment fitted to the ANZAC class frigates after their introduction into service has realised the designed capability and incorporated additional contemporary capability to ensure the lethality of the ANZAC Class. Having followed a fully developed engineering change process (for example, installation of additional systems, such as the anti-ship missile defence system) the through life margins of the platform have been consumed at a faster rate than anticipated when originally placed into service in 1996. This has resulted in a margin recovery program that has increased the frigates’ displacement from 3600 tonnes to 3900 tonnes. As a result, the frigates’ propulsion diesel engines are required to provide higher power and increased fuel consumption to achieve a given speed, and that the maximum speed has been marginally reduced. These additions and operational changes have consequently increased the cost of ownership.

Additional cost of operating as a ‘parent navy’ for the ANZAC class

2.37 The unique Australian modifications made to the frigates, in particular the addition of the Anti-Ship Missile Defence System and the Australian combat system, have distanced the class from its original design:

There are additional costs associated with Australia being a Parent Navy of the ANZAC Class, particularly associated with design and installation of engineering change (non-recurring engineering costs), either due to obsolescence or a change to the Functional Baseline. As a Parent Navy for the FFH [ANZAC class] platform design there is not the ability to leverage design, test and trial and market buying power to the same extent afforded to a non-Parent Navy platform such as has been the experience with the USN [United States Navy] Adelaide class FFG [Guided Missile Frigate] and RN [Royal Navy] Leander class DE [Destroyer Escort].36

An increase in required sustainment

2.38 To meet the recommendations of the Rizzo Review, there has been an increase in the number of maintenance tasks compared to the pre-Rizzo period. The 2015 advice to Deputy Chief of Navy reported that:

The number of URDEFs [Urgent Defects] have increased with an increase of 130 URDEFs from FY 13/14 to FY 14/15. There has been an increasing trend primarily on Priority 2 URDEFs with 525 raised in 2013, 669 raised in 2014 and 723 already raised in 2015 (to date 26 Oct 15).

2.39 Table 2.2 shows the reported Priority 1 and 2 Materiel Deficiency Reports from 2015–16 to 2017–18.37

Table 2.2: Reported Priority 1 and 2 Materiel Deficiency Reports, 2015–16 to 2017–18a,b

|

Financial year |

Priority 1 Materiel Deficiency Report |

Priority 2 Materiel Deficiency Reportb |

|||

|

|

Reports raised |

Open at end of periodc |

Reports closed |

Reports raised |

Open at end of periodc

|

|

2015–16 |

43 |

7 |

28 |

623 |

887

|

|

2016–17 |

39 |

6 |

16 |

708 |

1115

|

|

2017–18 |

23 |

2 |

22 |

603 |

810

|

Note a: The data set does not include those Materiel Deficiency Reports which have either been up- or down-graded.

Note b: Materiel Deficiency Reports were not raised for HMAS Perth (FFH-157) as it was placed into lay-up in 2017–18. This contributed to the reduction in reports raised in 2017–18.

Note c: ‘Reports closed’ for Priority 2 Materiel Deficiency Reports are not reported.

Note d: ‘Open at end of period’ are those materiel deficiency reports open at the end of relevant reporting month.

Source: ANAO analysis of monthly reported Sustainment Performance Reporting System results for Key Health Indicator ‘priority 1 materiel deficiency reports raised’ and ‘open priority 2 materiel deficiency reports’.

Extension of the life-of-type

2.40 The original planned withdrawal date was 2033 for the last ANZAC frigate. In June 2018, the Government was advised of Defence’s intention to extend the life-of-type of the ANZAC class, with the final ship to decommission in 2043 (as shown in Figure 2.2). Extending the life-of-type of the ANZAC class is intended to accommodate the design, build and introduction into service of Navy’s new Hunter class frigates under the Government’s 2017 Naval Shipbuilding Plan. Under the Plan, nine Hunter class ships will be built in Australia, with the first-of-class expected to enter service in 2027.38

Figure 2.2: Extension of the ANZAC class frigates’ life-of-type

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

2.41 The extension of the life-of-type of the ANZAC class frigates presents three significant risks for maintaining a surface ship capability during the transition from the ANZAC to Hunter class:

- Maintaining the material state of the ANZAC class frigates’ hulls and sub-systems — which have been assessed to be in a degraded state (see paragraph 2.28).

- Managing obsolescence within the ANZAC class — to maintain a contemporary level of capability and avoid a capability gap during the transition from the ANZAC class frigates to the Hunter class frigates. Further upgrades will be challenging as the ANZAC class is already considered to be at its design boundaries in terms of displacement and power generation (see paragraph 2.33).

- As the class continues to age, the cost of sustainment and obsolescence management can be expected to increase (as noted in the 2011 Rizzo Review).

2.42 Defence’s June 2018 advice to the Government of its intention to extend the life-of-type of the ANZAC class, to accommodate the selection of the Hunter class as Navy’s new frigate, did not include an analysis of the ANZAC class’ physical capacity to deliver the required capability until 2043. This approach does not align with the need to undertake strategic planning across programs of work as envisaged by the 2016 Defence Integrated Investment Program:

Both Defence and Australian industry will have a heavy workload to deliver, upgrade and sustain Australia’s future maritime force. A challenge will be to successfully manage the transition between the existing and new submarine, frigate and patrol boat fleets, in particular ensuring the continued availability of required capabilities to meet the Government’s tasking. Strategic planning across programs of work over several decades, as opposed to the past project-by-project approach, will be essential in meeting this challenge.39

2.43 Defence is undertaking a transition study for the ANZAC class frigates addressing the life-of-type extension, which is due to be completed in late 2019. Defence has commissioned the WAMA to undertake the transition study.

2.44 Undertaking the transition study after the decision to extend has been made is not without risk. For example, in October 2018, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute released a report on the capability transition from the Collins class submarines to the future submarine fleet which points to risks involved in transitioning from one complex platform to another:

Governments generally expect there to be no decline in capability throughout transition, but that might not be easy. The outgoing platform is nearing, or often past, the end of its design life and, due to obsolescence, might not be able to deliver the quality or quantity of capability required (which is why it’s being replaced) … The incoming platform isn’t a sure bet in terms of capability either. The schedule for its entry into service, particularly for a complex, developmental platform, might not be reliable. This is even more probable many years ahead of its actual entry, when some key transition decisions may need to be made (such as the basing location, the ramp-down schedule for the old platform, and workforce development). Also, teething troubles may limit the level of capability it can provide for some time, requiring the old platform to stay in service even longer than originally planned. Moreover, if the new platform is a fundamental step change in capability, or has a significantly different operating model, a whole raft of new enablers (such as new infrastructure, information systems, and training and maintenance facilities) may need to be in place before it provides its full capability, finally allowing the old platform to retire.40

2.45 The extension of the life-of-type of the ANZAC class frigates will require ongoing investment by Defence to maintain the class’s capability and to address: the latent effects of what Defence acknowledges to be an under-funded and under-resourced sustainment function; and the effects of operating the ships outside their Statement of Operating Intent. The success of the Government’s Naval Shipbuilding Plan also relies on Defence’s ability to maintain the ANZAC class capability to accommodate the design, build and introduction into service of the Hunter class frigates.

2.46 Auditor-General Report No. 39 2017–18 Naval Construction Programs—Mobilisation, included the following recommendation:

That Defence, in line with a 2015 undertaking to the Government, determine the affordability of its 2017 Naval Shipbuilding Plan and related programs and advise the Government of the additional funding required to deliver these programs, or the Australian Defence Force capability trade-offs that may need to be considered.

2.47 Defence disagreed with this recommendation.41 The recommendation was made in the context of an evolving naval shipbuilding policy and investment landscape which had moved on from the 2016 Defence Integrated Investment Program’s cost assumptions. Continuing changes in the Defence policy landscape, such as the decision to extend the ANZAC class life-of-type, indicate that there would be benefit in reviewing the cost assumptions for ANZAC class sustainment.

Recommendation no.2

2.48 In the context of developing its transition plan for the ANZAC class life-of-type extension, Defence review the capital and sustainment funding required to maintain the ANZAC class frigate capability until 2043, and advise the Government of the funding required to meet the Government’s capability requirements for the class or the capability trade-offs to be made.

Department of Defence’s response: Agree.

3. Performance monitoring and reporting

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Defence (Defence) has established an appropriate framework to monitor and report on the effectiveness and efficiency of operating the ANZAC frigates, in particular, whether relevant, reliable and complete performance measures had been developed and fit-for-purpose performance monitoring and reporting arrangements have been implemented.

Conclusion

Defence has established a performance framework for the ANZAC class frigates’ sustainment, with performance measures included in the Materiel Sustainment Agreement and reports provided to senior Defence leaders. While the performance measures adopted by Defence are relevant, the performance framework is not fully effective because the performance measures are:

- only partially reliable — as targets and/or plans regularly change; and

- not complete — as the measures do not address sustainment outcomes and efficiency.

In 2017–18 most of the Key Performance Indicators reported against were consistently not met.

The transparency of external reporting on the ANZAC frigates’ sustainment expenditure does not include Defence staffing costs or operational sustainment expenditure.

Areas for improvement

This chapter includes one recommendation aimed at improving the reliability and completeness of performance information for ANZAC class frigates sustainment.

Has Defence developed relevant, reliable, and complete performance measures for the sustainment of its ANZAC class frigates?

The performance measures adopted for the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates are relevant but only partly reliable, as targets and/or plans regularly change. Further, the performance measures are not complete, as they do not address sustainment outcomes or efficiency.

3.1 The performance monitoring and reporting arrangements agreed by the Royal Australian Navy (Navy) and the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) for the ANZAC class are set out in the ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule of the Navy Materiel Sustainment Agreement. Consistent with Navy’s Materiel Sustainment Agreement Performance Framework (see Appendix 3), the 2018–19 Product Delivery Schedule required reporting and monitoring against four Key Performance Indicators, 14 Key Health Indicators and one Strategic Sustainment Analytic, as outlined in Table 3.1.42 For a description of the performance measures, see Appendix 3.

Table 3.1: Performance measures for the ANZAC frigates, 2018–19

|

Performance measure |

|

Key Performance Indicators |

|

Monthly Materiel Ready Daysa achievement |

|

External maintenanceb period milestone achievement |

|

Price reliability — year to date price achievementc |

|

Conformance to operating intent |

|

Key Health Indicators |

|

Systems Program Office staffing levels |

|

Capability Manager Representative staffing levels |

|

Priority 1 materiel deficiency reports raisedd |

|

Open Priority 2 materiel deficiency reportsd |

|

External maintenance period cost growth |

|

Organic level maintenancee backlog |

|

External maintenance backlog |

|

External maintenance period effectiveness |

|

Demand satisfaction rate |

|

External maintenance period demand satisfaction rate |

|

NAVALLOWf configuration effectiveness |

|

Cannibalisationg events |

|

Open variations |

|

Open permanent engineering change proposals |

|

Strategic sustainment analytic indicator |

|

CASG cost per Materiel Ready Dayh |

Note a: A Materiel Ready Day is any programmed day where a platform is not in an external maintenance period, undergoing defect repair, in extended readiness, or subject to an urgent defect that because of its nature prevents the ship from achieving its current tasking.

Note b: External maintenance is maintenance normally performed in port, by industry.

Note c: Reporting for this Key Performance Indicator is required individually against the following price segments:

Year to Date Product Price Achievement — Baseline;

Year to Date Product Price Achievement — Operations;

Year to Date Product Price Forecast — Baseline; and

Year to Date Product Price Forecast — Operations.

Note d: Navy assigns priorities to defects as follows:

Priority 1 — Safe: a safety related defect, condition or deficiency including information, data or documentation, that precludes: the ship remaining at sea or sailing.

Priority 1 — Operations: a defect, condition or deficiency, including information, data or documentation that prevents the ship or establishment from completing a specified or implied task.

Priority 2: a defect or condition that significantly limits seaworthiness, personnel safety or operational capability, but does not preclude scheduled operational activities; or that significantly increase the probability of not being able to complete any potential tasking; and requires rectification at the next suitable opportunity in the existing program.

Priority 3: a defect or condition that does not warrant classification as a priority one or two because an alternative engineering solution or significant redundancy exists. The defect places a significant burden on ship’s staff.

Note e: Organic level maintenance is maintenance normally performed on-board by Navy personnel.

Note f: NAVALLOW (Navy Allowance) is the Navy logistic system which records shipboard materiel support for installed and portable equipment fitted to Navy ships and establishments.

Note g: Cannibalisation is the process of removing a working part from one piece of equipment, such as a ship or submarine, to put it into another that is in greater operational need.

Note h: Calculated as the combined monthly product price baseline and operations actuals and the monthly Materiel Ready Days achieved. To derive the value for the current reporting period, the monthly cost per Materiel Ready Day is calculated for the current and previous 11 reporting periods, and then averaged.

Source: Department of Defence.

Changes to performance measures

3.2 In 2016, Navy and CASG conducted a joint review of Navy’s performance framework to validate that the design and practical application of the framework was consistent with the endorsed approach and to identify opportunities for improvement. Notably, two Key Performance Indicators were removed from the framework as part of the review:

- ‘Cost per materiel-ready day achieved’ — removed on the basis that the measure required the Systems Program Office to enter four separate data elements and ‘stakeholder compliance’ was reportedly low.43 This indicator became a Strategic Sustainment Analytic.

- ‘Priority one materiel deficiency reports raised’ — removed on the basis that it duplicated data already reported for one Key Health Indicator (‘priority one materiel deficiency reports open’). The existing Key Health Indicator was renamed and restructured to ‘priority one materiel deficiency reports raised’ Key Health Indicator.

3.3 In mid-2017, a further Key Health Indicator ‘funding adequacy over Defence Management and Financial Plan’ was suspended. Whilst the Key Health Indicator is no longer reported against, it remains in the ANZAC class Product Delivery Schedule for 2018–19. In November 2018, the Department of Defence (Defence) advised that the metric had been suspended due to issues obtaining data.

Assessment of performance measures

3.4 Auditor-General Report No.30 2014–15 Materiel Sustainment Agreements assessed Navy’s performance monitoring and reporting arrangements, including for the ANZAC class frigates:

Overall, Navy’s KPIs/KHIs [Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators] are appropriately designed and measurable. The KPIs provide balanced and usable coverage of Navy’s sustainment products in terms of availability, cost, schedule, and materiel deficiencies.

While Navy’s performance measures are a step forward, there remain areas for improvement. None of Navy’s KPIs address outcomes, which is one of the four types of measures included in the DMO’s [now CASG] guidance. Measures such as Materiel Ready Days Achievement identify availability of platforms, but they do not indicate whether platforms were available when needed for operations. Further, some of the measures are not necessarily free from bias — that is, allowing for clear interpretation of results.44

3.5 Whilst there have been several changes to performance measures since 2015 (as outlined in paragraphs 3.2 to 3.3), the findings of this audit are consistent with the ANAO’s previous audit findings. The 2018–19 Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators for the ANZAC frigates were assessed as relevant, partly reliable, and not complete (in terms of the program). Table 3.2 summarises the ANAO’s assessment of the Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators for the ANZAC frigates. The strategic sustainment analytic indicator is not included in Table 3.2 as it does not have an established target or require formal review and signoff.

Table 3.2: Assessment of 2018–19 Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators for the ANZAC frigates

|

Characteristica |

Assessment |

|

Relevant |

Relevant. Each of the measures is designed to measure relevant outcomes for the sustainment of the ANZAC frigates. |

|

Reliable |

Partly reliable. Some of the measures are not necessarily free from bias with:

Targets set in this way may potentially mask deterioration and/or improvements in performance and not allow for clear interpretation of results. |

|

Complete |

Not complete because:

|

Note a: These characteristics are based on the criteria developed to evaluate the appropriateness of an entity’s Key Performance Indicators contained in Auditor-General Report No.33 2017–18 Implementation of the Annual Performance Statement Requirements 2016–17.

Note b: The short-term rolling average is an average of the last three monthly outcomes, exclusive of null values.The nine Key Health Indicators are: priority 1 materiel deficiency reports raised; open priority 2 materiel deficiency reports; organic level maintenance backlog; external maintenance backlog; external maintenance period effectiveness demand satisfaction rate; external maintenance period demand satisfaction rate; cannibalisation events; open variations; and open permanent engineering change proposals.

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.6 As noted in Table 3.2, the key performance measures are only partly reliable as some of the measures are not free from bias (that is, the interpretation of results is not clear):

- The majority of Key Health Indicators listed in Table 3.1 (see paragraph 3.1) report against the short-term rolling average and not a fixed target. The short-term rolling average is based on the results of the last three months and can change. Regular changes in the short-term rolling average can mask longer-term changes in performance, as targets are adjusted up or down in line with changes in performance over time. For example, there were instances where similar performance outcomes received different traffic-light ratings and different performance outcomes received similar traffic-light ratings.

- The Key Performance Indicators for ‘monthly Materiel Ready Days achievement’ and ‘price reliability—year to date price achievement’ are expressed in percentage terms against a plan or target, and changes in plans or targets may mask deteriorating performance. In 2017–18 there were multiple changes to the baseline and operational expenditure estimates.

3.7 As noted in Table 3.2, Navy’s Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators do not address sustainment outcomes. Whilst the performance measure such as Materiel Ready Days achievement identifies the availability of the platforms, it does not indicate whether platforms were able to meet operational requirements.

3.8 As noted in Table 3.2, Navy’s Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators do not address sustainment efficiency. The ‘CASG cost per Materiel Ready Day’ strategic sustainment analytic is described by Defence as a ‘broad measure of relative cost efficiency associated with the delivery of Materiel Ready Days’.45 However, the measure: has no set target and is not benchmarked, limiting the consistent measurement, assessment and interpretation of results; and does not require formal review or signoff, limiting management oversight of performance. The ANAO has previously observed that this key performance measure is not useful in determining the total cost of the capability to Defence.46

3.9 The Key Performance Indicators identified in the Materiel Sustainment Agreements (listed in Table 3.1), are not aligned with the performance indicators included in the Warship Asset Management Agreement. This is discussed further in Chapter 4.47

Recommendation no.3

3.10 Defence review the key performance measures for the ANZAC class frigates’ sustainment to ensure they are reliable and complete.

Department of Defence’s response: Agree with qualification.

3.11 This will require consultation across Defence to review extant reporting metrics; as these are currently standardised across multiple warship classes.

Has Defence established fit-for-purpose performance monitoring and reporting arrangements?

Defence has established arrangements to monitor and report on the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates, with senior Defence leaders made aware of the sustainment risks and issues experienced by the ANZAC class. The performance reporting indicates that there was underperformance for most of the Key Performance Indicators for the sustainment of the ANZAC class frigates during 2017–18. External reporting on the ANZAC class frigates’ sustainment expenditure would be more transparent if it included Defence staffing costs and operational sustainment expenditure.

Internal reporting

Sustainment Performance Management System

3.12 The Product Delivery Schedule requires performance reporting for the ANZAC class to occur via the Sustainment Performance Management System (SPMS). SPMS is Defence’s primary sustainment reporting and performance management system.48 SPMS can include Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators (as defined by the Services), and also strategic sustainment analytics used for cross-platform performance analysis.49 The performance outcomes in SPMS are reviewed and signed off monthly by representatives from both Navy and CASG. Subsequently, performance outcomes reported in SPMS for Navy Product Delivery Schedules are included in a monthly brief from CASG to the Deputy Chief of Navy, and used to inform the Quarterly Performance Report to senior stakeholders including the Defence Minister (see paragraph 3.22).

3.13 Performance reporting against targets is supported by commentary and review from representatives of CASG and the Capability Managers. The commentary includes relevant discussion on current issues, remediation, future risks, and areas requiring further attention. For example, Defence internal reporting captured the implications of placing HMAS Perth in extended lay-up50 (as shown in Figure 3.1), including reduced workforce pressures on the rest of the ANZAC class frigates and impacts on Surface Combatant availability. Defence advised the Minister for Defence of the decision to place HMAS Perth (FFH-157) in lay-up in December 2017.

Figure 3.1: HMAS Perth (FFH-157) in lay-up at the Henderson shipyard — July 2018

Source: ANAO site visit to Henderson shipyard — July 2018.

3.14 The unplanned, extended lay-up of HMAS Perth places further pressure on the other ANZAC class frigates and potentially adds to the cycle of operating the class outside of its Statement of Operating intent to meet capability and availability requirements.

3.15 As at 2 October 2018, three of Navy’s eight ANZAC class frigates were in dry-dock at the Henderson shipyard — HMAS ANZAC (FFH-150) and HMAS Arunta (FFH-151) were in deep-cycle maintenance and HMAS Perth (FFH-157) was in lay-up. Figure 3.2 shows the ANZAC class frigates’ Materiel Ready Days targets for 2018–19.

Figure 3.2: ANZAC class frigates’ target Materiel Ready Days 2018–19

Note a: A Materiel Ready Day is any programmed day where a platform is not in an external maintenance period, undergoing defect repair, in extended readiness, or subject to an urgent defect that because of its nature prevents the ship from achieving its current tasking.

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence documentation.

Reporting on sustainment for the ANZAC class frigates for 2017–18

3.16 Table 3.3 provides a summary of reported performance for Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators, as recorded in the Sustainment Performance Management System for 2017–18. The strategic sustainment analytic indicator is not included in Table 3.3 as it does not have an established target or require formal review and signoff.

Table 3.3: Performance against Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators as recorded in the Sustainment Performance Management System 2017–18a

|

Performance measure |

2017 |

2018 |

||||||||||

|

J |

A |

S |

O |

N |

D |

J |

F |

M |

A |

M |

J |

|

|

Key Performance Indicators |

||||||||||||

|

Monthly Materiel Ready Days achievement |

◆ |

◆ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

◆ |

◆ |

▲ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

|

External Maintenance Period Milestone Achievement |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

◆ |

■ |

◆ |

|

Conformance to operating intent |

◆ |

– |

◆ |

◆ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Year to date price achievement — baseline |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

▲ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆ |

▲ |

▲ |

■ |

◆ |

◆ |

|

Year to date price achievement — operations |

◆ |

◆ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Year end product price forecast — baseline |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

◆ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

◆ |

|

Year end product price forecast — operations |

◆ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

▲ |

■ |

◆ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Key Health Indicators |