Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Annual Compliance Arrangements with Large Corporate Taxpayers

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

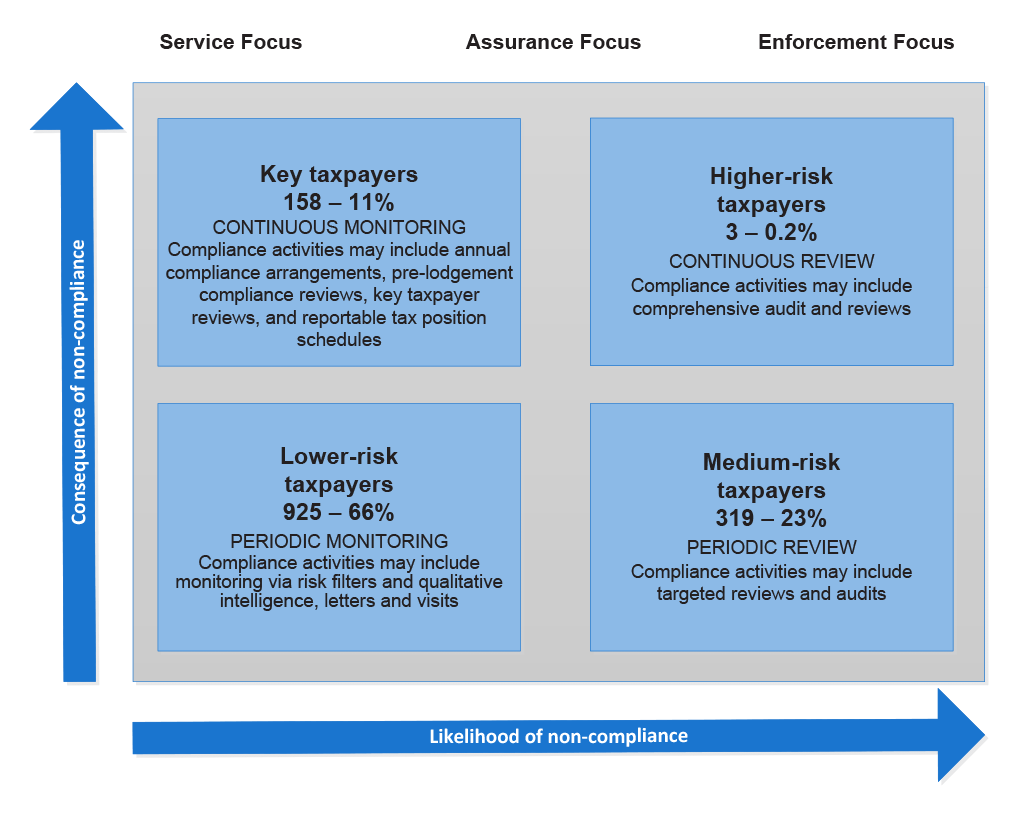

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s administration of annual compliance arrangements with large corporate taxpayers.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is responsible for administering Australia’s taxation and superannuation systems. It seeks to build confidence in its administration by helping people understand their rights and obligations, improving ease of compliance and access to benefits, and managing non-compliance with the law. The ATO’s administration covers a broad range of taxpayers, including individuals, small businesses and large corporate taxpayers.1

2. Of the $311.5 billion in net tax collected in 2012–13, the ATO advised that large corporate taxpayers contributed around $155.5 billion (49.9 per cent).2 In this light, the tax behaviour of these entities is integral to the health of Australia’s tax system, with potential consequences for the total revenue collected should they fail to meet their tax obligations.

3. The ATO’s compliance model provides the framework for assessing the risks of taxpayer non-compliance and developing responses according to the nature and level of identified risk, the causes of non-compliance and the level of cooperation of the taxpayers. For large corporate taxpayers, the ATO also aims to differentiate its compliance approach and level of engagement according to categories of risk—higher risk, key taxpayers, medium risk and lower risk assessed through its Risk Differentiation Framework.3 Particular focus is given to the larger entities within this group as they present a higher risk to overall taxation revenue through non-compliance.4

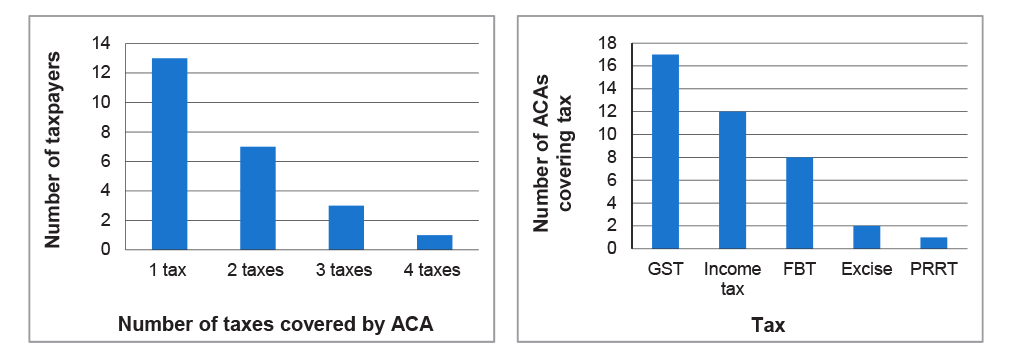

4. While continuing its program of retrospective risk reviews, audits and other compliance activities5, the ATO has increased efforts in recent years to build cooperative relationships with large corporate taxpayers, particularly those rated as ‘key’. These relationships aim to support full and open disclosure of contestable tax positions, and the identification and mitigation of tax risks in ‘real time’. This approach reflects the ATO view that most large corporate taxpayers are willing to comply, but that ongoing monitoring will assist it to clarify contestable positions in real time. It also aligns with the ATO’s 2020 vision.6

5. To support cooperative relationships, the ATO has developed a number of compliance initiatives that aim to build enhanced positive relationships and compliance outcomes with large corporate taxpayers. The ATO considers Annual Compliance Arrangements (ACAs) to be the centrepiece of these efforts.7 ACAs are directed at key large corporate taxpayers, and offer potential benefits, such as greater practical certainty about their tax positions, concessional treatment for penalties and interest, and higher levels of accessibility to the ATO. In return, these taxpayers are required to have good governance arrangements and disclose tax risks in real time. In this way, ACAs, which are voluntary, are intended to offer a ‘no surprises’ approach, with potential benefits for both the ATO and the taxpayer.

6. Cooperative compliance approaches have been adopted by many countries. In July 2013, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported on its assessment of 24 countries, including Australia, and noted the collaborative relationships being developed between large corporate taxpayers and revenue agencies.8 The OECD considers that cooperative compliance arrangements can assist revenue agencies to improve compliance by large corporate taxpayers. In this regard, it highlights the importance of transparency, disclosure and good governance systems on the part of both parties to reduce uncertainties over entities’ tax positions. The OECD also considers that cooperative compliance can help to restore trust and confidence in the relationship between business and tax administrations.9 While recognising concerns about the compatibility of this approach with equality before the law, the OECD concluded that cooperative compliance is entirely consistent with modern compliance risk management principles.

Administration of ACAs

7. ACAs were introduced by the ATO in 2008, and as at July 2014, there were 24 ACAs in place. Of these: 18 were with large companies, five with state government departments, and one with an Australian government entity.

8. Over time, the ATO has revised the basis for selecting taxpayers to enter into an ACA. Initially these arrangements were to be limited to the 50 largest entities, based solely on turnover. Now, as previously noted, only large entities assessed as ‘key taxpayers’ are considered potentially suitable for an ACA. The ATO informs large corporate taxpayers of its overall assessment of their relative risk of non-compliance, including if they are rated as potentially suitable for an ACA. It is open to these taxpayers to initiate discussions with the ATO to enter an ACA.

9. Taxpayers can negotiate an ACA for a single tax or for any combination of up to five separate taxes.10 As at June 2014, 13 ACAs were in place for a single tax and 11 were for two or more taxes. Most ACAs relate to goods and services tax (17 arrangements), with 12 for income tax, eight for fringe benefits tax, two for excise, and one for petroleum resource rent tax.

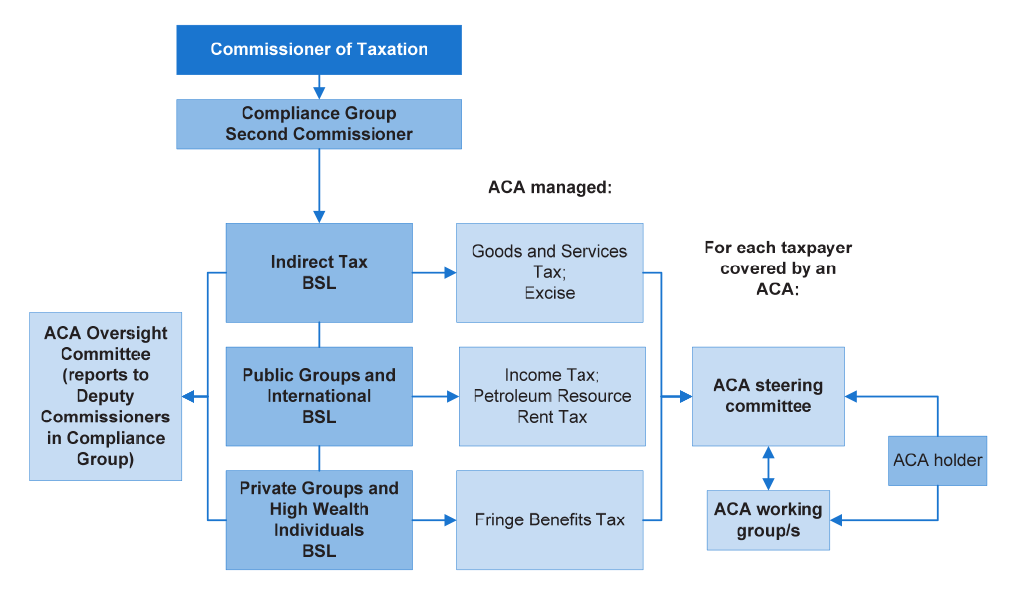

10. As ACAs cover different taxes, the ATO administers them through its various business and service lines in the Compliance Group. High-level oversight is provided through the ACA Oversight Committee, which includes senior executive staff from the business and service lines administering ACAs, reporting directly to the respective Deputy Commissioners in the Compliance Group.

11. The ATO has adopted the following three-phase process for entering into and administering ACAs:

- entry into the ACA—where the taxpayer’s governance arrangements are confirmed and a terms of arrangement document developed that sets out how the ACA will work;

- administration throughout the year—where the taxpayer continuously discloses material tax risks and the ATO reviews these disclosures; and

- closure at the end of the financial year—where the ATO and the taxpayer jointly review the taxpayer’s tax return. The ATO provides sign-off for low risk tax issues and develops mitigation strategies to address higher risk issues. The renewal of the ACA is also covered during this stage.

12. If the taxpayer voluntarily enters into an ACA, the ATO has agreed not to apply alternative compliance approaches, such as:

- pre-lodgment compliance reviews—used to identify and assess large corporate taxpayers’ income tax risks in the pre and post-lodgment periods;

- reportable tax position schedules—many large corporate taxpayers are required to disclose their more contestable and material income tax positions; and

- key taxpayer reviews—piloted in 2013–14 for the goods and services tax (GST) and excise, and implementation will be considered during the development of the 2014–15 Compliance Plan.

Reviews of ACAs

13. In the last two years, ACAs have been the subject of a review by the Inspector-General of Taxation11 and four ATO internal reviews12. The most recent internal review, at draft report stage in September 2014, considered the findings and recommendations of the previous reviews, which had highlighted scope to improve technical and strategic aspects of ACAs, particularly those covering income tax and goods and services tax (GST). The draft report noted ‘several operational and strategic concerns with the way ACAs are being applied as a real-time compliance product’, particularly their relatively high cost in the start-up years.13

Audit objective and criteria

14. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s administration of annual compliance arrangements with large corporate taxpayers.

15. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the governance arrangements for ACAs are well planned and effective;

- there are sound processes for identifying entities to enter into an ACA;

- results achieved to date reflect initial expectations of ACAs; and

- individual ACAs are effectively administered, in accordance with internal policies and procedures, to achieve intended benefits.

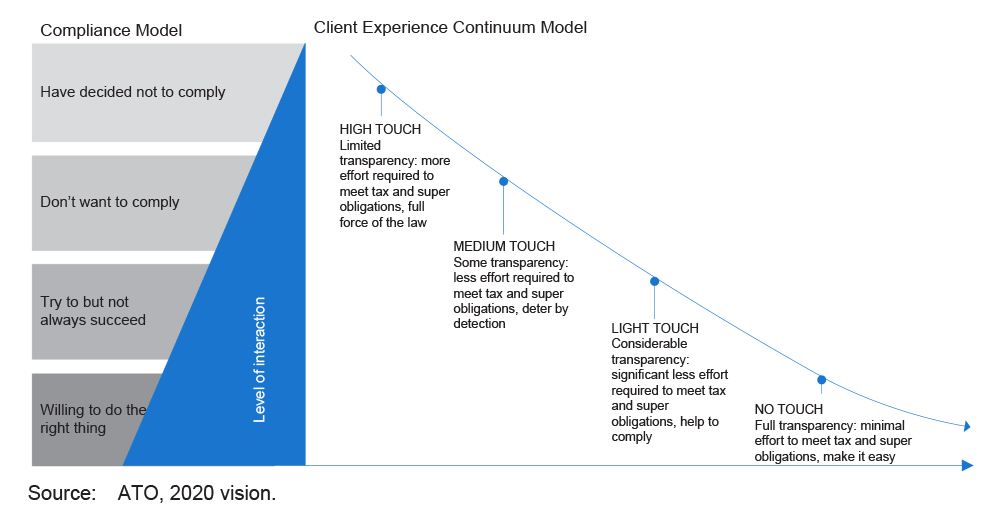

Overall conclusion

16. ACAs were introduced in 2008 in response to feedback from large corporate taxpayers that they were looking for a ‘no surprises’ approach in relation to their tax positions. Built on the premise that taxpayers would have sound tax governance arrangements and provide full and true disclosure, ACAs aim to provide taxpayers with greater practical certainty of their tax positions. The ATO sees ACAs as the premium cooperative compliance arrangement for large corporate taxpayers. As such, they are closely aligned with the ATO’s 2020 vision, which embraces real-time engagement and disclosure as well as a lighter touch for compliant taxpayers.

17. The effective administration of ACAs relies on judgements by the ATO as to the soundness of the governance arrangements put in place by large corporate taxpayers, the reliability of the information they disclose on significant matters affecting their taxation liability, and the review of this information by the ATO on an annual basis. While not without risks to both parties, this approach is consistent with contemporary international practice of building cooperative relationships with those larger corporate taxpayers considered willing to meet their tax obligations and unlikely to be involved in aggressive tax planning practices. ACAs have also delivered benefits to participating taxpayers. These taxpayers advised the ANAO that the arrangements have provided greater certainty for more straightforward taxation matters and improved the ATO’s responsiveness to their concerns.14

18. Notwithstanding the positive experiences of participating taxpayers, take-up of ACAs has been low. In 2013–14 only 24 of the 158 potentially suitable key taxpayers (15 per cent) had an ACA, and six of these taxpayers would not be categorised as ‘key’ under the current risk assessment arrangements.15 As such, ACAs have not been the centrepiece of cooperative collaboration with large corporate taxpayers as envisaged when introduced, but do provide an alternative approach for large corporate taxpayers to engage with the ATO on potentially contentious tax matters. Most large corporate taxpayers are aware of ACAs as a result of the ATO’s promotional efforts but prefer to be subject to alternate compliance activities, such as pre-lodgment compliance reviews, instead of voluntarily entering into an ACA.16

19. Taxpayers have advised the ANAO and the ATO that the main reason for not entering into an ACA was the relatively high cost of meeting the requirements of the ACA, particularly at the entry phase. They perceived other compliance activities to have similar benefits but lower administrative demands.17 Although the ATO has not quantified the cost of participating in or administering an ACA, it recognises these concerns, and is looking to better tailor the intensity of its compliance activity to the assessed risk, as envisaged in its 2020 vision.18

20. ACAs currently provide a differentiated means by which the ATO can engage with large corporate taxpayers. If ACAs are to be positioned to maximise the participation of suitable large corporate taxpayers, it will be important for the ATO to reassess the extent of differentiation, taking into account the costs and benefits to taxpayers and itself. In this regard, the ATO will also have to decide whether ACAs are to be positioned more as part of the spectrum of compliance approaches going forward rather than as the centrepiece of cooperative collaboration as initially envisaged.

21. In administering existing ACAs, shortcomings in recordkeeping and oversight have meant that the ATO could not readily demonstrate: the extent and outcomes of its efforts to gain assurance over taxpayers’ governance arrangements; the number, nature and treatment of disclosures; or success in encouraging higher levels of compliance on the part of those large corporate taxpayers with an ACA. Accordingly, the ATO has not administered ACAs as effectively as it could have, particularly when these arrangements were viewed as a flagship measure that provided a new and innovative way of engaging with large corporate taxpayers.

22. Issues surrounding the design and administration of ACAs have been raised in recent internal and external reviews, in line with the findings of this audit. It is apparent the ATO needs to act on these findings to improve the effectiveness of ACAs if they are to achieve the benefits envisaged when the arrangements were introduced in 2008.

23. Further, the ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at improving the design of ACAs, and the ATO’s recording of taxpayers’ disclosures of contentious tax positions and how they were dealt with through ACA processes.

Key findings by chapter

Management Arrangements (Chapter 2)

24. The ATO has created a matrix structure to manage tax compliance, based on the type of tax and the market segment. Consequently, ACAs are administered across different business and service lines, drawing on the knowledge and expertise of the staff in these areas. This approach supports the administration of individual ACAs, but has generated inconsistency in the negotiation, operation and sign-off of the arrangements.19 While the ATO has taken some steps to improve the administration of ACAs, such as the establishment of the ACA Oversight Committee in June 201220, a lack of coordination, intelligence and information exchange across business and service lines was apparent. There has also been considerable slippage in the Committee progressing key elements of its work program, including refining policies, reviewing processes and developing supporting procedures for administering ACAs. These shortcomings belie ACAs being administered as the ATO’s premium cooperative compliance arrangement.

25. The level of internal and external reporting is proportionate to the scale of ACA activity. However, the ATO has been slow to evaluate the approach to determine if it is achieving the benefits envisaged. The first effectiveness evaluation report is due to be completed late in 2014, although this evaluation project has been ongoing for almost two years. Interim findings from this evaluation, and previous ATO reviews indicate that ACAs have improved relationships with large corporate taxpayers and, in doing so, have potentially supported compliant behaviour. While the interim findings drew on the views of taxpayers and ATO officers about the costs of ACAs, it has not quantified the costs of administering ACAs, the benefits or the impacts on revenue.

Positioning of ACAs within the ATO’s Compliance Framework (Chapter 3)

26. ACAs are intended to be at the centre of the ATO’s efforts to develop cooperative compliance relationships with large corporate taxpayers. The ATO initially offered ACAs to the top 50 corporate taxpayers by turnover, and extended this to the top 100 taxpayers when take up numbers were low. In 2011–12, following the introduction of the Risk Differentiation Framework as the ATO’s risk modelling tool, the ATO wrote to 35 of the 133 large corporate taxpayers then rated as ‘key’, specifically inviting them to enter into an ACA.

27. The ATO has also promoted ACAs publicly through: various industry groups; ATO contacts; community and stakeholder forums; and regular ATO publications. Despite these efforts, only 24 of the 158 potentially suitable key taxpayers (15 per cent) had entered into an ACA by July 2014.21 The low level of participation has been raised in a number of recent reviews, and the ATO is consequently considering options for improving take-up. Of prime importance is the need to clarify the purpose of ACAs22 and to develop a strategy for positioning these arrangements within the compliance framework for large corporate taxpayers.

28. There is scope for the ATO to better differentiate the operation and administrative requirements of ACAs from other compliance activities, and better align the benefits and costs across the range of compliance activities for large corporate taxpayers. In this way, the requirements for administering and participating in an ACA would be proportional to the level of risk associated with the specific taxpayer and support the effective use of resources by the ATO and taxpayers.

29. Developing a comprehensive compliance strategy for large corporate taxpayers that clearly distinguishes ACAs from other compliance activities would enable the ATO to more actively market ACAs.

Administration of ACAs (Chapter 4)

30. An ACA is the basis for the relationship between the ATO and the ACA holder. As such, the activities undertaken and the terms of the ACA are intended to be flexible and able to be tailored to the individual circumstances of the ACA holder and the complexity of the tax issues. Nonetheless, there is a need for the ATO to closely monitor differences across ACAs, especially in the terms established during the negotiation phase. The ANAO’s review of all 24 ACAs in place as at July 2014 identified variability across ACAs and that the reasons for this variability were not always clear. Although the ACA Oversight Committee now reviews the terms of each new or renewed ACA, there is scope for greater consistency and improved monitoring and management of ACAs.

31. ACA guidance requires that an ACA taxpayer: has sound governance and tax risk management arrangements; and works with the ATO in an open and collaborative way, including through disclosure and ongoing dialogue about material tax risk.23 In assessing taxpayers’ governance and tax risk management arrangements, the ATO has differing approaches for the main tax types. The ATO advised that, given GST is a transaction based tax, having effective systems in place is more important for GST compliance than for income tax and fringe benefits tax (FBT) compliance, where compliance issues are usually the result of differing interpretations of the law by the taxpayer and the ATO. As such, the ATO is more reliant on the governance and systems of GST taxpayers and validates the governance and tax risk management arrangements of GST ACA holders annually. In contrast, it will accept written assurance from income tax and FBT ACA taxpayers as confirmation of sound governance and tax risk management. The ATO views these assurances as indications of whether significant tax issues are being considered and approved at appropriate levels in the organisation, and subject to proper review. Nevertheless, the ATO has not always followed this approach24, and there is scope for the ACA Oversight Committee to more closely monitor and better align the administration of individual ACAs across business and service lines.

32. During the course of the year, many taxpayers have disclosed tax risks. The ATO advised of 41 income tax disclosures in 2013‒14 involving transactions valued at approximately $13.7 billion. However, it was not possible for the ANAO to readily confirm these transactions from the ATO’s records, or to ascertain the ATO’s response to the disclosures in many instances. Nevertheless, it was evident that ACA taxpayers have frequently used the ATO’s interpretative assistance area to resolve areas of contention—the ATO advising that 167 private rulings25 were sought by these taxpayers over the past three years. The extent of these disclosures and rulings indicates that ACAs have been useful in identifying and treating tax risks for participating taxpayers, albeit not always in ‘real time’ as ruling processes can be lengthy.

33. The ACA annual review is the opportunity for the ATO and the ACA taxpayer to discuss major transactions and business events from the year, with a view to signing off those considered to be low risk by the ATO and developing mitigation strategies for those considered to be high risk. ANAO analysis of the annual review showed some variability across teams and business and service lines. For example, although all reviews considered risks, the three income tax review reports were most effective in considering the broader operation of the ACA. These reviews considered: interactions with the taxpayer; and other ATO activities such as compliance activity and private binding rulings. In two cases the steering committee responsible for the individual ACA did not meet to sign off the review year, only meeting if there was a dispute between the ATO and the taxpayer. In addition, the membership of the working group and the steering committee for one ACA taxpayer was the same, which essentially meant that the steering committee was endorsing its own work.

34. As indicated above, the ATO does not retain information related to disclosures in a consistent manner. Key ACA documents (including disclosures) are not consistently managed in accordance with the ATO’s policy, and stored on the enterprise wide case management system. Rather, these documents can be in a variety of locations, making it difficult in some instances to view a full history of the ACA with the taxpayer. For three taxpayers, the ATO was not able to locate all documents relating to their ACAs.

35. An analysis of the time taken to complete the various stages of the ACA process also shows that the ATO is often not meeting its own timeliness targets. There would be benefits in including ACA cases in the ATO’s enterprise wide quality assurance process or alternatively undertaking quality assurance at the business and service line level.

Summary of entity response

36. The ATO provided the following summary comments to the audit report.

The ATO welcomes the opportunity to comment on the ANAO report. The ATO accepts both recommendations and notes suggestions that have been made in the report where the ATO can further improve its administration of the Annual Compliance Arrangement (ACA) product.

It is noted that the ANAO acknowledges that an approach through Annual Compliance Arrangements or their equivalent is consistent with international practices of building cooperative relationships with larger corporate taxpayers.

It is pleasing that the report recognises that ACAs are well placed to be at the forefront of such a strategy as a complementary part of the ATO reinvention program.

Annual Compliance Arrangements were introduced in 2008 and there have been ongoing adjustments and evolution to ensure it is ‘fit for purpose’. There has been regular feedback from large corporates as to the utility of these arrangements, which we have sought to respond to appropriately. However, we also acknowledge that it is time to refresh our approach to ACAs and, as identified in your report, we are in the final stages of an internal review of the ACA strategy. While we are yet to finalise our taxpayer consultation on the outcomes of this review, we envisage a renewed Annual Compliance Arrangement offer.

As part of this Annual Compliance Arrangement re-design work, the ATO will be further considering the broader compliance framework for large entities across all taxes to ensure a consistent and graduated compliance response to the tax risks profiles of all large business taxpayers. This should maximise taxpayers’ ability to voluntarily address tax risks as they are identified, as well as provide an appropriate and proportionate enforcement response, if voluntary compliance cannot be achieved.

In following through on this design work, the ATO will ensure that the new and revised approaches are appropriately supported with staff training and internal and external guidance materials where required. We will also ensure that, for reporting and record keeping purposes, success factors, outputs and outcomes are clearly articulated to our staff to allow much more effective measurement and evaluation in the future

We acknowledge that the report identifies that there has been a low number of Annual Compliance Arrangements relative to the number of large corporates that may be suitable for such arrangements. However, the ATO believes that the number of ACAs currently being managed reflects the voluntary nature of the ACA arrangements and large corporates can choose to enter or not enter into such arrangements. As indicated in the report from interviews conducted by the ANAO, large corporates make their own assessment of the benefits and costs that they see in entering into such an arrangement.

While noting the need for a clearer expression as to the level of desirable take-up in the total number of Annual Compliance Arrangements, we believe the total number of taxpayers likely to meet our criteria is far less than the 158 key taxpayers. A realistic figure may well be in the range of 35-50 of these key taxpayers but we will further consider this approach as we implement the recommendations of the report.

We have benefited enormously from taxpayers’ participation in the ACA program. We have applied some of the experiences from the ACA program to other large business compliance approaches – for example pre-lodgment compliance reviews, risk workshops and key taxpayer reviews. It has also helped us improve our understanding of large business governance and tax risk management approaches. This understanding is helping us now to develop our work on compliance self-assurance models and pilots such as the external compliance assurance process.

With respect to resourcing of the ACAs, because of the size and influence of the large corporates who are in ACAs, there will always be costs associated with our compliance approaches, regardless of whether or not they are participating in the ACA program. We will work on improving how we identify the net costs or benefits of an ACA as part of our future program, in line with comments made in this report.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 3.39 |

To better tailor ACAs to taxpayers’ assessed compliance risks, the ANAO recommends that the ATO reassesses: the design of these arrangements within the compliance framework for large corporate taxpayers; the level of compliance assurance required to provide benefits for both parties; and the administrative processes. ATO response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.42 |

To support ongoing assessment of the effectiveness of ACAs to identify and mitigate tax risks in real time, the ANAO recommends that the ATO enhance its record keeping of taxpayers’ disclosures of contentious tax positions, and the strategies developed to deal with these disclosures. ATO response: Agreed. |

1. Background and Context

This chapter provides background information on the Australian Taxation Office’s annual compliance arrangements with large corporate taxpayers. It also outlines the audit approach, including the objective, criteria, scope and methodology.

Introduction

1.1 The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) is responsible for administering Australia’s taxation and superannuation systems. It seeks to build confidence in its administration by helping people understand their rights and obligations, improving ease of compliance and access to benefits, and managing non-compliance with the law. The ATO’s administration covers a broad range of taxpayers, including individuals, small businesses and large corporate taxpayers.26

1.2 Of the $311.5 billion in net tax collected in 2012–13, the ATO advised that large corporate taxpayers contributed around $155.5 billion (49.9 per cent). The tax behaviour of these entities is integral to the health of Australia’s tax system, with potential consequences for the total revenue collected should they fail to meet their tax obligations.

1.3 The ATO’s compliance model provides the framework for assessing taxpayers risk of non-compliance and developing responses according to the nature and level of identified risk, the causes of non-compliance and the level of cooperation of the taxpayers. For large corporate taxpayers, the ATO also aims to differentiate its compliance approach and level of engagement according to categories of risk—higher risk, key taxpayers, medium risk and lower risk assessed through its Risk Differentiation Framework.27 Particular focus is given to the larger entities within this group as any non-compliance will potentially have higher consequences for revenue. In 2013–14, of the 1100 entities in the ATO’s ‘large market’, 158 were categorised as ‘key’ as they were assessed as having a low likelihood of not meeting their tax obligations, but the amount of their tax liability means that any incorrect payment could have serious consequences for overall tax revenue. Because the significant majority of the ‘large market’ segment were rated as lower or medium risk (89 per cent in 2013–14) and three taxpayers were categorised as high risk, they were not eligible to be offered an annual compliance arrangement (ACA) on the criteria determined by the ATO.

1.4 While continuing to undertake a program of retrospective risk reviews, audits and other compliance activities across the risk categories28, in recent years the ATO has increased efforts to build cooperative relationships with large corporate taxpayers, particularly those rated as ‘key’. These relationships aim to support full and open disclosure of contestable tax positions, and the identification and mitigation of tax risks in ‘real time’. This approach reflects the ATO view that most large corporate taxpayers are willing to comply, but that ongoing monitoring will assist in clarifying contestable positions29 in real time.30 To this end, the ATO’s interpretative assistance activities are also important, in particular private binding rulings that clarify the ATO’s view of contestable positions.31

1.5 Within the context of the ATO seeking to develop increased cooperative compliance relationships with the larger corporate taxpayers, key developments have been the:

- introduction of forward compliance arrangements (FCAs) in 2005. FCAs were voluntary arrangements between the ATO and large corporate taxpayers that established how they would work together, with the aim of providing greater certainty for these taxpayers on their tax matters and reducing the need for costly audits. FCAs marked a new cooperative approach with the ATO;

- launch of ACAs in May 2008. Similar in purpose to FCAs and still a voluntary arrangement, ACAs are intended to provide more practical certainty for large corporate taxpayers by enabling the review and management of tax risks in real time, but with less administrative demands; and

- development and staged implementation of the Risk Differentiation Framework commencing in 2008–09, for assessing the compliance risks associated with those taxpayers with extensive tax obligations, including high wealth individuals and large corporate taxpayers.

Annual compliance arrangements

1.6 ACAs are voluntary arrangements that the ATO negotiates with large corporate taxpayers to define and govern the compliance relationship. Initially established for three years, ACAs can be extended by agreement between the parties. The potential benefits to the taxpayer and to the ATO of entering into an ACA are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Potential benefits of entering into an ACA

|

Taxpayer |

ATO |

|

|

Source: ATO.

1.7 The criteria for selecting large corporate taxpayers to enter into an ACA have changed since they were established in 2008. Initially, the option of entering into an ACA was limited to the 50 largest entities, based on the value of their annual turnover. Taxpayers that had an FCA in place were given the option of rolling the arrangement into an ACA when the FCA expired. Commencing in 2011–12, only those large entities assessed through the Risk Differentiation Framework as key taxpayers are considered potentially suitable for an ACA. The ATO informs large corporate taxpayers of its overall assessment of their relative risk of non-compliance, including if they are rated as potentially suitable for an ACA. It is open to these taxpayers to initiate discussions with the ATO to enter an ACA.

1.8 ACAs are built around the ATO’s assessment that particular taxpayers have sound governance processes to support meeting their tax obligations, and a commitment to ongoing disclosure of tax matters as they arise. While not overriding the application of tax laws and policies, ACAs provide greater practical certainty for taxpayers in relation to their tax positions as the ATO will consider tax risks in real time. In this way, ACAs are intended to offer a ‘no surprises’ approach, with potential benefits to both the ATO and the taxpayer.

1.9 Five types of taxes may be covered by an ACA: income tax, GST, excise, petroleum resource rent tax (PRRT), and fringe benefits tax (FBT).32 A taxpayer may negotiate an ACA for a single tax or for any combination of these taxes. An ACA for multiple taxes will include a separate schedule for each tax, which is negotiated and managed individually.

1.10 As at July 2014, the ATO had ACAs with 24 entities: 18 large companies33, five state government departments, and one Australian Government entity. Of the ACAs established since 2008, all but one is ongoing.34 The total number of large corporate taxpayers with an ACA from 2008–09 to 2013–14 is shown in Table 1.2. The total number of taxpayers with an ACA in any year reflects only a small proportion of those that are assessed by the ATO as potentially suitable for an ACA. Table 1.2 also shows the number of taxpayers assessed as potentially suitable for an ACA following the introduction of the Risk Differentiation Framework.

Table 1.2: Number of taxpayers with an ACA and those assessed as potentially suitable for an ACA for the period, 2008–09 to 2013–14

|

Year |

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

Taxpayers with an ACA |

3 |

8 |

17 |

18 |

20 |

24 |

|

Taxpayers assessed as potentially suitable for an ACA |

50 |

100 |

100 |

135 |

163 |

158 |

Source: ATO.

1.11 Of those taxpayers with an ACA as at June 2014, 13 were for a single tax while 11 were for two or more taxes. Most of the ACAs in place relate to GST (17 arrangements), with 12 for income tax, eight for FBT, two for excise, and one for PRRT. The number of taxpayers that have entered into ACAs, the number of taxes each covers and type of tax are set out in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Taxpayers with an ACA, by number of taxes covered and type of tax

Source: ANAO analysis.

1.12 The ATO considers ACAs to be ‘the centrepiece of our efforts to build enhanced positive relations with large business’.35 Voluntarily entering into an ACA will preclude the taxpayer from being subject to the following alternative compliance approaches:

- pre-lodgment compliance reviews—used to identify and assess large corporate taxpayers’ income tax risks in the pre and post-lodgment periods;

- reportable tax position schedules—many large corporate taxpayers are required to disclose their more contestable and material income tax positions; and

- key taxpayer reviews—piloted in 2013–14 for GST and excise, and implementation will be considered during the development of the 2014–15 Compliance Plan.

1.13 The ATO also has ongoing engagement with industry to further develop approaches to addressing tax risks that support its direction for managing tax compliance, as set out in the ATO’s 2020 vision.36 The 2020 vision embraces the concept of real-time engagement, with approaches tailored to the level of risk associated with different taxpayers and the effective allocation of the ATO’s resources. On this basis, the level of effort required by a taxpayer to meet their taxation and superannuation obligations would reflect their willingness to comply, as set out in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 Client experience continuum model

Source: ATO, 2020 vision.

ATO arrangements for administering ACAs

1.14 The ATO’s administration of Australia’s taxation and superannuation systems are centred around three groups37 and the business and service lines (BSLs) within these groups. ACAs are administered in the Compliance Group, by the BSL responsible for the category of tax involved.

1.15 The ATO has developed a three-phase process for administering ACAs, which involves:

- entry into the ACA—where the taxpayer’s governance arrangements are considered and a terms of arrangement document developed that sets out how the ACA will work;

- administration throughout the year—where the taxpayer can disclose material tax risks and the ATO will review these disclosures; and

- closure at the end of the financial year—where the ATO and taxpayer jointly review the taxpayer’s tax return. The ATO provides sign-off for low risk issues and develops mitigation strategies for higher risk issues.38 The renewal of the ACA is also covered during this stage.

1.16 Negotiating and managing ACAs is the responsibility of operational staff within the relevant BSL. The document setting out the agreed terms of the ACA (including the governance arrangements, duration, commitments, disclosures, records, issues registers and dispute resolution mechanisms), is usually signed by the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner) and the entity’s Chief Executive Officer or Chief Financial Officer. Some ACAs establish a steering committee for each tax type (10 cases), while most establish one steering committee to oversee all taxes covered by the ACA (14 cases). There is also a working party for each ACA, comprising senior representatives from the ATO and the taxpayer.

1.17 High-level management is provided through the ATO’s ACA Oversight Committee, which includes senior executive staff from the BSLs administering ACAs, reporting directly to the respective Deputy Commissioners in the Compliance Group.

Reviews of annual compliance arrangements

Internal ATO reviews and consultations

1.18 Commencing in late 2012, ACAs have been the subject of four ATO internal reviews, commissioned by the Public Groups and International (PG&I) and Indirect Tax (ITX) business lines, as well as consultation with key stakeholders. The reviews and consultations are the:

- Review of Annual Compliance Arrangements, completed in November 2012;

- PG&I ACA Community Involvement Workshop, conducted in February 2014;

- Annual Compliance Arrangements Strategy Review (GST), commissioned in January 2014; and

- Annual Compliance Arrangements (ACA) Review, commissioned in January 2014 and at draft report stage as at September 2014.

1.19 The PG&I business line’s Review of Annual Compliance Arrangements, November 2012, identified a significant degree of inconsistency in the way that income tax ACAs are managed, including:

- the way the ACA concept was communicated to the taxpayers and the teams;

- uncertainty in the interpretation of clauses within the ACAs;

- an absence of meaningful guidelines; and

- an absence of active leadership from a central authority that could directly engage with the teams on issues ranging from the drafting of the arrangements to the management of the ACA.

1.20 The PG&I ACA Community Involvement Workshop conducted in February 2014 assessed six income tax ACA cases and also reviewed and augmented the outcomes from the November 2012 review. The report presented 22 recommendations covering four areas of concern: entry and exits into an ACA; staffing and support; policy and process; and the quality framework.

1.21 The ACA Strategy Review (GST) undertaken by the ITX business line in April 2014 examined the strategic positioning of ACAs. The key finding was that the administration of ACAs does not align with the ATO 2020 vision of a lighter touch for those entities with a strong record of disclosure and compliance.

1.22 The Annual Compliance Arrangements (ACA) Review considered the findings and recommendations of the previous reviews and examined ACAs with regard to, among other things, the direction of the ATO’s approach to compliance, and the interaction with the compliance arrangements introduced after ACAs were established. The September 2014 draft review report noted that the other internal reviews have revealed ‘several operational and strategic concerns with the way ACA’s are being applied as a real-time compliance product’, particularly their relatively high cost in the start-up years.39 The findings of these reviews are discussed throughout this report.

External review of ACAs

1.23 In August 2012 the Inspector-General of Taxation published the Review into Improving the Self-Assessment System which referenced ACAs.40 The Inspector-General’s concerns and observations included:

- ACAs are costly and require substantial additional work. These costs can be disproportionate where taxpayers have adequate governance systems in place, and explain the low take up of ACAs;

- refinements could be made to ACA processes to make it less resource intensive and the benefits more accessible, with a view to widening the availability of the process to other taxpayers; and

- taxpayers confirmed benefits in terms of having improved access to ATO staff and obtaining administrative certainty, but these benefits related mainly to uncontroversial issues. Further, where signoffs were qualified with ‘no further action at this time’, this did not give sufficient certainty as the ATO could re-examine the issues at a later time.

1.24 The report made the following two recommendations in relation to the administration of ACAs:

- to make ACAs more widely available to taxpayers through the ATO publicly communicating the expected administrative demands of entering into and maintaining an ACA as well as the expected benefits; and

- to appropriately address the expected increase in ATO workload41 with respect to ACAs and reduce timeframes and compliance costs associated with ACAs by considering overseas models.

The ATO agreed to these recommendations.

International experience

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

1.25 In July 2013, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) examined the relationship between large corporate taxpayers and revenue bodies and published its report, Co-operative Compliance: a Framework―From Enhanced Relationship to Co-operative Compliance. The report listed 24 countries42, including Australia, as having collaborative and trust-based relationships between large corporate taxpayers and revenue bodies.43

1.26 The report noted that cooperative compliance arrangements can assist revenue agencies to improve compliance by large corporate taxpayers. In this regard, the OECD highlights the importance of transparency, disclosure and good governance systems on the part of both parties to reduce uncertainties over entities’ tax positions. The OECD also considers that cooperative compliance can help to restore trust and confidence in the relationship between business and tax administrations.44 While recognising concerns about compatibility of the approach with equality before the law, the OECD concluded that cooperative compliance is entirely consistent with modern compliance risk management principles.

1.27 Jurisdictions, including the United Kingdom and Ireland, that carried out a qualitative evaluation of their cooperative compliance programs indicated the following main benefits:

- no surprises on either side;

- a better and real-time information position;

- greater certainty in relation to forecasting tax yield and accurate and timely tax returns and payments;

- faster resolution of issues from committed parties; and

- enhanced and more open relationship between the revenue body and the taxpayer.45

1.28 The most common benefits to the taxpayer were cited as improved compliance, lower compliance costs and greater certainty. The report included a recommendation that measures of effectiveness need to be refined and integrated into the assessment of the overall compliance strategy.46 Of particular relevance to the ATO’s administration of ACAs was that similar initiatives were being implemented in the United States of America and the Netherlands.

1.29 More broadly, the OECD reported that cooperative compliance arrangements can assist revenue agencies to improve compliance by large corporate taxpayers. In this regard, it highlights the importance of transparency, disclosure and good governance systems on the part of both parties to reduce uncertainties over entities’ tax positions.

United States of America

1.30 The United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS) developed the Compliance Assurance Process (CAP) in 2005. The CAP was developed to avoid years of uncertainty about a large corporation’s actual tax liability: IRS audits of the tax returns lodged by large corporations were taking, on average, four years to complete. With the CAP, the IRS and taxpayers agree on how to report tax issues before their return is filed. Compliant and cooperative taxpayers can receive a streamlined IRS review of their tax return through its ‘Compliance Maintenance’ process.

1.31 The United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) assessed the CAP process and in August 2013 released its report Corporate Tax Compliance: IRS Should Determine Whether Its Streamlined Corporate Audit Process is Meeting Its Goals. The report noted that while anecdotal evidence indicated that CAPs may be effective in ensuring compliance, increasing certainty and saving resources, the IRS had not succeeded at assessing whether or not the CAP was achieving its goals. Recommendations made by the GAO included that the IRS: evaluate the process; develop measures and targets for the goals; and consistently capture data to track goal progress.47

Netherlands

1.32 ACAs are similar to the horizontal monitoring approach undertaken by the Dutch Tax Administration. Horizontal monitoring is based on mutual trust, transparency and understanding, with respective roles and responsibilities set out in a mutual agreement.

1.33 In 2011, the Netherlands State Secretary for Finance established an independent Committee to evaluate the horizontal monitoring program to measure the results and success of the program and make recommendations for future development. The Committee released its report Tax Supervision―Made to Measure in June 2012.

1.34 The report confirmed the advantages of greater transparency, speedier certainty and increased mutual understanding for the revenue body. As to whether compliance costs have decreased, the Committee observed satisfaction from taxpayers in the very large business segment, however, there was no empirical data to support this. The Committee recommended that appropriate performance indicators be developed as, on the information available, it could not answer the question of whether horizontal monitoring was effective and efficient.48

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

Objective and criteria

1.35 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s administration of annual compliance arrangements with large corporate taxpayers.

1.36 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the governance arrangements for ACAs are well planned and effective;

- there are sound processes for selecting entities to enter into an ACA;

- results achieved to date reflect initial expectations of ACAs; and

- individual ACAs are effectively administered, in accordance with internal policies and procedures, to achieve intended benefits.

Scope and methodology

1.37 The focus of the audit was on large corporate taxpayers with an ACA in place, and potentially suitable taxpayers that had chosen not to enter into an ACA.

1.38 The audit methodology included consulting with taxpayers and industry groups, interviewing ATO staff and examining relevant documentation and systems. The ATO’s case management system was analysed in relation to each ACA in place.

1.39 The audit has been conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards at a cost of approximately $478 000.

Structure of the report

1.40 Table 1.3 outlines the structure of the report.

Table 1.3: Structure of the report

|

Chapter and title |

Overview of chapter |

|

|

2 |

Management Arrangements |

Examines the ATO’s management arrangements supporting the administration of ACAs. |

|

3 |

Positioning of ACAs within the ATO’s Compliance Framework |

Examines the processes to identify, encourage and select taxpayers suited to entering an ACA, and the positioning of ACAs in the ATO’s compliance framework for large corporate taxpayers. |

|

4 |

Administration of ACAs |

Examines the ATO’s administration of ACAs. |

2. Management Arrangements

This chapter examines the ATO’s management arrangements supporting the administration of ACAs.

Introduction

2.1 The introduction of forward compliance arrangements in 2005, followed by ACAs in 2008, reflects the ATO’s commitment to establishing cooperative relationships with selected large corporate taxpayers, and assisting them to manage their tax risks and tax compliance in real time. While the intent of the arrangements has not changed, aspects of the management and operation of ACAs have been further developed since they were introduced. Organisational restructures have also affected management arrangements, with the ACA Oversight Committee being established in 2012. In addition, there have been changes to internal and external monitoring and reporting arrangements as well as efforts to evaluate the success of ACAs in achieving their expected benefits.

2.2 To assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s management of ACAs, the ANAO examined the:

- management structure supporting ACAs, including the role of the ACA Oversight Committee;

- management information and external reporting of ACAs; and

- evaluation of the effectiveness of ACAs in achieving their expected benefits.

Management structure

2.3 Management of ACAs is largely undertaken by the following BSLs in the ATO’s Compliance Group:

- Indirect Tax (ITX) manages ACAs for GST and excise;

- Public Groups and International (PG&I) manages ACAs for income tax and PRRT; and

- Private Groups and High Wealth Individuals (PGH) manages ACAs for FBT.

2.4 The structure of the Compliance Group, and the management of ACAs by each BSL, is set out in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Structure of the Compliance Group, June 2014

Source: ANAO from ATO documentation.

2.5 From August 2013, the structure of the work managed by the Compliance Group changed from BSL responsibilities largely based on entities’ turnover, to greater alignment with the structures and legal frameworks that exist in the market sectors. The new structure recognises that different entities have different governance and reporting requirements, and that the ATO’s compliance approaches could be better tailored to their specific circumstances.49 To this end, the ATO has created a matrix structure to manage tax compliance, based on the type of tax and the market segment, for example: the ITX BSL manages all entities’ indirect and excise taxes; PG&I BSL manages income tax and PRRT for public groups and internationals; and PGH BSL manages taxes (including income tax) for this market segment and FBT for all segments.

2.6 The restructure has also changed the number of entities managed by the three BSLs. PG&I managed approximately 31 000 entities as at June 2014, including approximately 1100 large businesses that had previously been the sole responsibility of the (then) Large Business and International BSL, the smaller public entities previously managed in the Small and Medium Enterprises BSL and small enterprises in the Micro Enterprises and Individuals BSL. PGH now manages those large private entities previously in the Large Business and International BSL and is responsible for the administration of FBT which previously fell under the Small and Medium Enterprises BSL. The ITX BSL continues to manage all indirect taxes across all taxpayers.

2.7 Irrespective of the new ATO structure, as previously noted ACAs have always been administered by different BSLs depending on the type of tax, particularly income tax, GST and FBT. The ATO has recognised (and the recent internal reviews have reinforced) that administering ACAs across three BSLs has generated inconsistency in the negotiation, operation and sign-off of the arrangements.50 While some steps have been taken to improve the consistency of administration, such as the establishment of the ACA Oversight Committee in June 2012, a lack of coordination across BSLs was still being identified as an issue by the ATO in June 2014.

ACA Oversight Committee

2.8 The ACA Oversight Committee was established following concerns from staff in the three BSLs administering ACAs about the overarching and day-to-day governance and decision-making processes for ACAs across the BSLs. The Committee was established to ensure a robust governance framework and a ‘one ATO approach to ongoing implementation of the ACA product’.51 Membership of the Committee includes senior executive staff from the BSLs managing ACAs, with reporting obligations to the Deputy Commissioners in the Compliance Group.

2.9 The terms of reference for the ACA Oversight Committee are set out in the Committee’s charter, endorsed on 25 October 2012, and include:

- developing a framework for the implementation and governance of ACAs;

- developing policies and supporting procedures to ensure that taxpayers are suitable for entry into an ACA; and

- ensuring that ACAs are an integral part of the compliance strategy for the large market.

2.10 The Committee’s terms of reference required it to focus initially on the 35 taxpayers that had been offered an ACA in 2011–12 to assess the take up rate and appropriate tailoring of ACAs; and to evaluate the effectiveness of ACAs. Essentially, the Committee was to develop a suite of administrative measures for ACAs, including developing a governance framework, strategy and effectiveness measures.

Operation of the ACA Oversight Committee

2.11 The ACA Oversight Committee primarily operates through its monthly meetings. As at 30 June 2014, the Committee had met on 25 occasions. The ANAO reviewed the minutes of the meetings held from June 2012 to May 2014. The minutes reflect discussions on key issues relating to the administration of ACAs, as set out in its charter, and a rolling list of action items. However, the minutes also reveal that several of the key items of work relating to the management of ACAs and the role of the Committee had either been substantially delayed or not been completed. Specifically, the:

- work program for the Committee, originally due by July 2012, was presented to the Committee on 26 June 2014;

- revised large business ACA process map52, originally due by October 2013, had similarly been delayed due to competing work priorities, but discussed at the 29 May 2014 meeting where it was decided it would be held over pending the outcome of further reviews; and

- performance framework and effectiveness measures project for ACAs, commenced in November 2012, and was scheduled for completion in late-2014.

2.12 More generally, the meeting minutes indicate that the Committee was aware of many issues concerning the administration of ACAs but was taking some time to implement remedies, such as developing an overarching strategy for ACAs, and refining policies and supporting procedures for these arrangements.

2.13 While some common aspects of ACAs have been developed through the Committee, in practice BSLs have established their own arrangements for managing ACAs. At a high level, the processes for negotiating an ACA are similar in each BSL (for example, the terms and conditions of the arrangements, and governance assurance letters), but key components of the ACAs differ between the BSLs and often between teams within a BSL. As discussed in Chapter 4, differences include the management of issues registers, end of year reviews, and sign-off of the annual tax return. The arrangements are designed to allow a degree of flexibility to accommodate the different payment schedules and complexities associated with the various taxes subject to an ACA. However, the terms of reference for the Committee acknowledge the benefits of more consistency in processes and improved knowledge and information exchange across BSLs.53

Resourcing arrangements for administering ACAs

2.14 The ATO has not sought additional funding through the budget processes to support the introduction and ongoing management of ACAs, and no staff are allocated solely to their administration. Rather, ACAs are supported as part of the work of staff in the ATO’s compliance teams.

2.15 As at 30 May 2014, data provided by the ATO indicated that 26.5 full time equivalent staff (FTE) were working on the administration of ACAs: 18 FTE for income tax, six for GST and excise, two for PRRT and 0.5 for FBT.

2.16 The ATO’s expectation that there would be a reduction over time in the resources necessary to manage ACAs has generally not materialised. Rather, there has been a fairly constant and relatively high workload associated with the annual sign-off process, and when renewing arrangements. For example, a compliance team managing an ACA advised the ANAO it had become a de facto lead relationship manager for the ATO in dealing with the company, which can be time consuming.54

Training and guidance

2.17 The ATO provides guidance material on its intranet on the use of the case management system55 for managing ACAs. Each BSL has different products in the case management system for their respective ACAs and the training provided to staff across the BSLs has been variable over the years. ATO officials advised that during the ACA pilot stage, the PG&I BSL developed a one-day training package for staff, as well as an information kit for visits by SES officers to the top 100 companies. The ATO advised that for the Client Relationship Managers56 in the ITX BSL, a three-day training course is available which includes information on ACAs. For PRRT, documents were produced outlining the broad context of where the ACAs fit into the business, guiding principles, deliverables and interactions with the taxpayer.

2.18 Nearly half the compliance officers interviewed57 during the audit advised that they had not received specific ACA training. Rather it has been a matter of learning on the job with the help of the instruction material on the intranet and advice from the ACA Oversight Committee Secretariat as required.

2.19 While representatives of large corporate taxpayers interviewed by the ANAO were generally satisfied with the level of service provided by ATO staff managing their ACA, several cited issues when there had been a change of manager. Over time, professional relationships had been established and matured.

2.20 Recent internal reviews conducted by the ATO have identified the need for improved guidelines to help ensure administrative practices for ACAs are applied consistently across BSLs.58 These practices include negotiating ACAs, dealing with legacy issues such as GST implications of multi-party transactions, providing appropriate (not excessive) levels of administrative support, interpreting core ACA terms, examining disclosures and conducting the annual sign-off.

2.21 There would be benefit in the ACA Oversight Committee reviewing the current training and guidance material to ensure there is appropriate support for compliance officers managing ACAs, particularly in light of the move from the traditional audits and reviews to a more cooperative compliance approach.

Management and external reporting of ACAs

2.22 Each of the three BSLs produces its own management report on ACAs, which are primarily included in consolidated reports of compliance performance with respect to the taxes managed by the BSL. The key management reports focus on deliverables (outputs) or progress in addressing particular issues or administrative challenges, as shown in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: ACA management reports, by business and service line

|

Type of report |

Frequency |

|

Public Groups and International (income tax) |

|

|

Report on income tax liabilities that are covered by an ACA |

Monthly |

|

Consolidated results set out the value of income tax compliance results for the year to date for taxpayers with an ACA |

Monthly |

|

Consolidated data on the value of transactions disclosed under an ACA and the value of unresolved risk |

Monthly |

|

PRRT work report prepared for the PRRT Assistant Commissioner |

Monthly |

|

Indirect Tax (GST and excise) |

|

|

Compliance performance report prepared for the Deputy Commissioner |

Monthly |

|

GST report that is also sent to the states and territories |

Quarterly |

|

Significant issues report to the Deputy Commissioner |

Monthly |

|

Items of note (dot points) across the large market to the Assistant Commissioner |

Fortnightly |

|

Private Groups and High Wealth individuals (FBT) |

|

|

Compliance team keeps Assistant Commissioner abreast of workload |

Ongoing |

Source: ATO.

2.23 These reports generally provide the senior executives in the respective BSLs with a regular update of the main contentious tax issues surrounding the administration of ACAs, an overview of the revenue associated with such issues and an update on the value of assessments amended through ACA processes. For example, in PG&I, the Deputy Commissioner was informed of the share of the large market covered by ACAs (around 28 per cent of assets as at 30 June 2014), the value of risks under review and the tax amount involved ($1 878 million and $512 million respectively in 2013–14) and the value of tax adjustments (around $82 million made in 2013–14).

2.24 The ACA Oversight Committee is also informed about operational matters (such as those ACAs being negotiated or renewed) and key issues and tax risks being addressed. However, it is not regularly informed of the broader outputs or outcomes of ACAs in achieving envisaged benefits.59 To improve reporting to the Committee and senior ATO executives about key issues and outputs, an ACA register is being developed by the Committee secretariat. The register is designed to be provided to the Committee on a monthly basis including key facts for each ACA such as key dates, tax coverage, and emerging issues.

2.25 External reporting of ACAs has been through the Commissioner of Taxation annual reports 2008–09 to 2011–12. Information about the number of ACAs and value of tax assured by these arrangements was reported. For example, in 2011–12 it was reported that there were ‘18 annual compliance arrangements (ACAs) in place with large businesses, covering income tax, GST, excise and fringe benefits tax with $260 billion in GST and $100 billion in income covered by ACAs’. No information in relation to ACAs was provided in the 2012–13 annual report.

2.26 Overall, management reporting provides BSL executives with useful and timely information about the key issues and outputs associated with ACAs, and external reporting is appropriate to the scale of ACAs. However, there has been only limited progress to date in measuring the effectiveness of ACAs, as discussed below.

Evaluating the effectiveness of ACAs

2.27 The ACA Oversight Committee initiated work in 2012 to evaluate the effectiveness of ACAs in meeting their objectives.60 After more than two years, this evaluation is scheduled for consideration in late-2014. While it had been intended to include income tax, GST, excise and PRRT, the evaluation has subsequently been undertaken for income tax ACAs only.

2.28 The ATO has also conducted a series of reviews into ACAs and associated compliance approaches for large corporate taxpayers, as noted in Chapter 1. These reviews have collected information largely from ATO compliance officers and executives about their experiences and perceptions of the benefits and effectiveness of ACAs.61 As part of the ACA review, in June 2014 the ATO surveyed suitable companies that had not entered into ACAs to ascertain the main reasons for them not participating. These various sources of information have provided a qualitative overview of the effectiveness of key aspects of ACAs, which the ATO has considered in the ACA review, and are discussed in paragraphs 2.32 to 2.38.

2.29 The ATO advised that it faces challenges in evaluating ACAs, such as measuring the additional revenue from, or improved compliance by, large corporate taxpayers as a result of ACAs, or concepts such as certainty and improved cost effectiveness.62 However, quantitative data is available to support analysis of changes in the tax paid by and compliance performance of taxpayers before and after entering into an ACA, and a range of qualitative information is also available. To provide a defensible opinion about the effectiveness of ACAs, the ATO could apply the principles and guidelines for conducting evaluations set out in its compliance effectiveness methodology.63 Conducting such an evaluation that includes all relevant taxes may also help to determine the continuing relevance and positioning of ACAs.

ATO evaluation of effectiveness

2.30 In anticipation of the ATO’s evaluation of ACA effectiveness being completed in late-2014, Table 2.2 outlines the interim evaluation findings as at August 2014.

Table 2.2: ATO evaluation of ACA effectiveness, interim findings as at August 2014

|

Evaluation criteria |

Interim finding |

|

Assure appropriate revenue is collected |

Based on data collected to date, it appears an appropriate amount of revenue is being collected from ACA taxpayers. |

|

Influence compliance behaviour |

Some compliance teams felt that any material change in compliance behaviour may be due to prior compliance activity. Only one team reported the taxpayer had changed their original position on tax treatment. Other reported behaviour changes were:

|

|

Improve cost effectiveness for the ATO |

Mapping compliance FTE usage shows an increased use of resources before entry into an ACA with some tapering off. This is supported by views from ACA teams and senior executive service officers that setting up the ACA agreement is difficult, time consuming and resource intensive for the ATO. |

|

Improve ATO understanding of taxpayer’s business and its environment |

Although ACA teams and SES officers consider they have an improved understanding of the individual ACA taxpayer’s business, there is inconsistent reporting of intelligence. This suggests the ATO is not consistently sharing this knowledge to better understand, detect or deal with similar risks that might exist in the wider industry. |

|

Supply intelligence |

Other than procedures for the case management system, there is no consistency in the way the teams gather, share and deal with intelligence. There is ad hoc sharing of information and limited use of the corporate intelligence recording system ATOintelligence Discover. Intelligence gathering, dissemination and reporting needs improvement. |

|

Improve risk management in cooperation with taxpayer |

At the taxpayer level, sound risk management principles appear to be generally adopted, however only half the teams reported communicating directly with operational risk managers. This may be due to most of the potential risks identified being rated as low. |

|

Improve cost effectiveness for the taxpayer |

There is no evidence to support the proposition that ACAs are more cost effective for taxpayers. There was general acknowledgment that costs increased at the establishment phase, which for some taxpayers may be offset by indirect savings such as lower costs for seeking external tax advice. Non-ACA taxpayers reported costs to be a barrier. Other data suggests that ACA taxpayers perceive additional benefits that may outweigh any additional costs. |

|

Provide the taxpayer with greater certainty |

The number of rulings for ACA taxpayers increased generally and this was confirmed by teams and SES officers through interviews. However, there are concerns by ACA taxpayers that the ATO sign-off for ACAs may not be legally binding. Taxpayers were also concerned the sign-off is for one year and not the life of a transaction. |

|

Improve stakeholders’ perceptions that ACA is working as intended |

Internal ATO stakeholders considered ACA taxpayers are generally positive about ACAs. Views of taxpayers who have not entered into an ACA indicate that, from their perspective, the costs may outweigh the benefits. |

Source: ATO.

2.31 Overall, the interim findings are that ACAs are generally working as intended although the overall benefits to be gained through entering into an ACA are not to the extent expected for taxpayers or the ATO. In particular, while ACA taxpayers are generally positive about ACAs, there is no evidence that the agreements have improved cost effectiveness for these taxpayers, while greater certainty is often being sought though private rulings.64 From the ATOs perspective, ACA taxpayers are considered to be paying appropriate amounts of tax, but the ATO is not effectively using the intelligence gathered from administering these arrangements to strengthen compliance approaches more generally, and administration costs are relatively high particularly at start up. These interim evaluation findings are broadly confirmed by analysis conducted for this audit or from broader ATO reviews.

ANAO stakeholder interviews and broader ATO reviews

2.32 The ANAO conducted interviews with 25 entities that had an existing ACA or had previously held an ACA. Thirty entities that had not entered into an ACA despite being offered one in 2011–12 were also contacted and 12 entities provided feedback to the ANAO. The feedback from these interviews, together with findings from the ATO reviews, address the effectiveness of key elements of the administration of ACAs as outlined below.

Benefits from entering an ACA

2.33 In general, entities were satisfied with their ACAs. For them it is a relationship management arrangement that results in a higher level of service from the ATO. Many entities considered that having an ACA made the relationship less adversarial, increased the level of trust, and avoided the more onerous audits and reviews. There was also greater certainty about tax positions, some improved responsiveness of the ATO to resolving their issues, and benefits from threshold extensions and interest and penalty concessions.65

Reasons for not entering an ACA

2.34 The extent of effort required at start-up and ongoing administrative demands were the main barriers to entering into an ACA. Many entities were also satisfied with their relationship with the ATO and did not see any additional benefit from having an ACA.

Cost effectiveness for taxpayers and the ATO

2.35 As previously noted, the costs of entering into an ACA were considered high relative to other compliance arrangements, particularly on initial entry and if any legacy issues were outstanding.66 Some ACA holders had achieved savings due to their ability to obtain ‘free’ advice from the ATO in relation to the treatment of certain tax risks rather than having to pay external advisors. There was also general agreement of speedier resolution of issues, unless they were more complex, in which case extended periods were still required for resolution.

2.36 ATO reviews have found that ACAs generally require additional ATO resources compared with other compliance arrangements for large entities.67 This is partly due to the need to provide sign-off within five months of lodgment of their annual tax return, something not required as part of, for example, the pre-lodgment compliance review process. These reviews have indicated that ACAs are often not cost-effective for the ATO, as the costs of administering an ACA can outweigh any benefits from improved real-time disclosures by compliant taxpayers.

Providing greater certainty for taxpayers

2.37 Although most ACA holders interviewed considered that an ACA increased the certainty of sign-offs, which effectively close off any further ATO reviews for all relevant tax returns and activity statements, some doubt remained as the annual sign-off was not legally binding and instead based on good faith. There was concern that the ATO may still reverse its position, although no matters had been re-opened to date.68 The other main issue raised was that the annual sign-off is qualified (that is, it only applies to a certain year under certain conditions). Taxpayers’ expectations are that, if the ATO changes its view, that it will be prospective rather than retrospective. As outlined in the Inspector-General of Taxation’s Review into Improving the Self Assessment System69, administrative certainty relates to uncontroversial issues—an ACA does not give certainty for controversial issues, and taxpayers generally rely on rulings processes.70

Assuring revenue collection and improving compliance

2.38 ATO internal reviews found little evidence to demonstrate that ACAs had increased compliance and revenues collected. The ATO advised the total values cooperatively assured during 2013–14 include GST throughput of over $31 billion, total sales and purchases of $523 billion, $4.3 billion in excise revenue and $10.9 billion in income tax revenue. Nevertheless, some ATO officials and entities that have entered into an ACA indicated that compliance may be higher under an ACA, particularly as many ACA holders tend to over-disclose to ensure all matters have been considered by the ATO when sign-off is granted.

Conclusion

2.39 The ATO has a framework for administering ACAs, based around the compliance teams in the three responsible BSLs with oversight from a coordinating committee. While the ACA Oversight Committee has discharged many of its responsibilities, it has been slow to progress initiatives designed to strengthen the ATO’s administration of ACAs and to provide consistency in practices across BSLs. There would be benefit in the Committee reviewing the training and guidance material provided to officers managing ACAs in light of feedback from recent reviews about the core ACA terms, the operation of the ACA and its interaction with other ATO compliance arrangements.

2.40 Management reporting provides BSL executives with useful and timely information about the key issues and outputs associated with ACAs, and external reporting is appropriate to the scale of ACAs. However, ACAs were introduced six years ago, and the ATO has not yet systematically evaluated their effectiveness in providing the benefits envisaged. It is intended that an internal evaluation, due to be completed in late-2014, will report on the level of effectiveness of income tax ACAs. However, the evaluation needs to be broadened to include the other taxes as was originally envisaged.

2.41 Indications from ATO reviews, and ANAO consultation with ATO officials and stakeholders for this audit, are that ACAs have delivered benefits to participating taxpayers through higher levels of service and increased certainty of tax positions for more straightforward matters. However, although the actual costs of administering ACAs are not known, ATO and ACA holders consider administrative demands to have been relatively high.

3. Positioning of ACAs within the ATO’s Compliance Framework

This chapter examines the processes to identify, encourage and select taxpayers suited to entering an ACA, and the positioning of ACAs in the ATO’s compliance framework for large corporate taxpayers.

Introduction

3.1 Based on Australia’s tax system of self-assessment and voluntary compliance, the ATO’s approach to working with large corporate taxpayers is guided by the principles in the Taxpayers’ Charter71 and the compliance model. The model provides the framework for assessing the risks of taxpayer non-compliance and developing responses according to the nature and level of identified risk, the causes of non-compliance and the level of cooperation of the taxpayers.72 Consistent with this model, there are a number of elements to the ATO’s compliance framework for large corporate taxpayers. As outlined in Chapter 1, these include: standard audit and risk reviews73; pre-lodgment compliance reviews; reportable tax position schedules; key taxpayer reviews and ACAs.

3.2 The ATO has consistently described ACAs as ‘the centrepiece of our efforts to build enhanced positive relations with large business’.74 As such, it is considered to be the premium real-time compliance arrangement within the ATO’s cooperative compliance model—where self-assessment and cooperative compliance is seen as the cornerstone of the Australian tax system.75

3.3 As previously discussed, ACAs are voluntary arrangements that offer large corporate taxpayers potential benefits, such as greater practical certainty of their tax positions, concessional treatment for penalties and interest, and higher levels of accessibility to the ATO. In return, these taxpayers are required to have good governance and risk management processes as assessed by the ATO and to disclose tax risks in real time. Despite the recognised benefits, only 24 taxpayers had an ACA in place as at July 2014.

3.4 To assess the ATO’s processes for selecting taxpayers for an ACA, and the role of ACAs in the ATO’s compliance framework for large corporate taxpayers, the ANAO examined the:

- current approaches to identifying taxpayers for an ACA;