Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of Travel Entitlements Provided to Parliamentarians

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of Finance’s administration of travel entitlements provided to Parliamentarians.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Commonwealth Parliament comprises the Senate, which has 76 members (12 for each State and two for each of the Territories), and the House of Representatives, which has 150 members.1 In addition to the remuneration provided as a consequence of being a member of the Parliament, Parliamentarians are provided with a range of support services and allowances to assist them in effectively carrying out their duties. These are generally referred to as ‘entitlements’ and include office accommodation and facilities, staff support, travel, and various other resources to assist Parliamentarians service and inform their constituents.

2. While responsibility for the administration and delivery of Parliamentarians’ entitlements is spread across a range of Commonwealth departments, the Department of Finance (Finance) has by far the most significant role. This is particularly the case in relation to the administration of non-remuneration entitlements, including travel.

3. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has previously examined some or all aspects of the administration of Parliamentarians’ entitlements on a number of occasions. This has included conducting three performance audits since 2000, comprising:

- Audit Report No.5 2001-02, Parliamentarians’ Entitlements 1999-2000, tabled in August 2001 (referred to in this audit report as the 2001–02 audit report);

- Audit Report No.15 2003–04, Administration of Staff employed under the Members of Parliament (Staff) Act 1984, tabled in December 2003 (referred to in this audit report as the 2003–04 audit report); and

- Audit Report No.3 2009–10, Administration of Parliamentarians’ Entitlements by the Department of Finance and Deregulation, tabled in September 2009 (referred to in this audit report as the 2009–10 audit report).

4. A common theme arising from the previous ANAO audits was that the existing entitlements framework is difficult to understand and manage for both Parliamentarians and Finance. This situation arises as a result of the:

- complex (and often overlapping and ambiguous) array of legislation, determinations, rules, guidelines and conventions under which various entitlements are provided; and

- absence of an articulation or shared understanding of the scope of the key terms that largely govern whether a particular transaction will be considered to be within entitlement (such as ‘parliamentary business’, ‘electorate business’ and, for office-holders, ‘official business’).

5. The 2009–10 audit report noted that a positive outcome of that audit was that the then Special Minister of State (SMOS) had informed ANAO that the then Government agreed that immediate attention was warranted in clarifying the entitlements framework and providing greater transparency. In addition to changes that were to be made to certain existing entitlements, the then Government had also agreed to the conduct of a ‘root and branch’ review of the entitlements framework.

6. In that context, as was the case with previous audits, the 2009–10 audit report made a range of recommendations relating to improving the transparency and accountability of entitlements administration. This included recommending that, in progressing the government decision to undertake a review of the framework, Finance examine options that would:

- provide a principles-based legislative basis that authorises the provision of specified entitlements for defined purposes and in accordance with eligibility criteria; and

- enable accountability processes (such as usage certifications by Parliamentarians) to be mandated.

7. In agreeing with that recommendation, Finance advised that: ‘These options have been included in the terms of reference for the review of the entitlements framework’.

Review of Parliamentary Entitlements

8. The ‘root and branch review of Parliamentarians’ entitlements was publically announced by the then SMOS on 8 September 2009. The review committee comprised: Ms Barbara Belcher AM (Chair), former First Assistant Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; Mr John Conde AO, President of the Remuneration Tribunal; Ms Jan Mason, then Deputy Secretary of the Department of Finance; and Professor Allan Fels AO, former Australian Competition and Consumer Commissioner and then Dean of the Australia and New Zealand School of Government.

9. In its report, the Committee for the Review of Parliamentary Entitlements (CROPE) noted that its work represented the first comprehensive review of federal parliamentary entitlements in over 35 years. The terms of reference that guided the review comprised a mix of high level strategic issues (including recommending options for legislative framework reform) and detailed specific references. A public call for submissions was made on 3 October 2009, and the Committee chair also wrote to all then current Parliamentarians; affected former Parliamentarians, Prime Ministers and Governors-General; state jurisdictions; and selected academics and Commonwealth agency heads inviting their views. Public hearings were not held, but the chair and other members of the Committee spoke to a number of those who had made submissions and other interested parties. The Committee also examined how selected similar jurisdictions regulate parliamentary entitlements.

10. The Committee’s report setting out 39 recommendations was provided to the then Government on 9 April 2010. Reflecting the review’s terms of reference, those recommendations addressed a range of matters including proposals for broad legislative reform; enhancing administrative arrangements in relation to existing accountability mechanisms; and recommendations directed at abolishing, reforming or establishing a range of specific entitlements under the existing framework. Four of the report’s recommendations related to parliamentary remuneration and associated consequential effects. Five recommendations proposed significant legislative and administrative reform in order to establish a consistent, simple and transparent framework for funding Parliamentarians’ non-remuneration business expenses (or ‘tools of trade’—currently known as entitlements). In March 2011, the then Government announced that it had agreed with the first of the CROPE report recommendations which related to restoring the power of the Remuneration Tribunal to determine parliamentary base salary, with relevant amendments to the Remuneration Tribunal Act 1973 required to implement that measure being subsequently enacted. The remaining CROPE report recommendations were referred by the then Government to the Remuneration Tribunal to consider and make recommendations.

11. A December 2011 report by the Tribunal setting out the outcome of its subsequent work value assessment in relation to parliamentary remuneration also supported the CROPE report’s conclusions in relation to the inadequacies of the existing framework in terms of providing a clear and transparent view of what Parliamentarians are entitled to be provided with in order to undertake their duties and how they use those non-remuneration entitlements. Significantly, the Tribunal recommended legislative reforms consistent with those set out in the CROPE report.

12. Following the deliberations to date of the previous and current governments and the Remuneration Tribunal, as at April 2015 action had been taken in respect to all or part of 17 of the 39 recommendations made in the April 2010 CROPE report.2 This includes some recommendations that have been actioned by either the Tribunal or government through means that took a different form to those proposed by the CROPE report, or in respect to which the Tribunal’s December 2011 report identified the basis on which it had decided to reject recommendations relating to the proposed folding in of certain existing entitlements into base salary.

13. However, to date, there has been no formal government response to the recommendations of the CROPE report, or subsequent Remuneration Tribunal report, in relation to fundamental reform of the legislative and administrative framework underpinning the provision of Parliamentarians’ ‘tools of trade’.

Review of Finance’s administration of entitlements

14. In 2010, Finance commissioned a review of its administration of Parliamentarians’ entitlements by Ms Helen Williams AO, former Secretary of the Department of Human Services (referred to as the Williams Review). Under its terms of reference, given the recommendations of the April 2010 CROPE report were yet to be considered by government, the Williams review examined Finance’s administration of entitlements as provided under the existing framework. The review’s report provided to Finance in January 2011, made eight multi-faceted recommendations. As at 28 February 2013, Finance had reported that all 47 elements of those recommendations had been implemented.

Measures announced by SMOS in November 2013

15. On 9 November 2013, the current SMOS announced a number of measures directed at strengthening the rules governing Parliamentarians’ business expenses.3 That announcement followed a period in the latter half of 2013 that involved significant media scrutiny of the use of travel entitlements by a number of Parliamentarians. Reflecting that context, the measures announced by the Minister primarily related to travel entitlements, as provided under the existing framework. In particular, the SMOS announced the introduction from 1 January 2014 of:

- an amended declaration to be made by a Senator or Member when submitting travel claims;

- a 25 per cent loading to be paid where a Parliamentarian made a subsequent adjustment to travel claims, other than where the adjustment was the result of an error made by Finance. There would be a grace period of 28 days after making a travel claim in which Parliamentarians could make adjustments without penalty; and

- mandatory training for Parliamentarians and their offices if more than one incorrect claim was lodged within a financial year.

16. Amendments to the Parliamentary Entitlements Act 1990 (PE Act) to implement the proposed 25 per cent penalty loading and other associated measures were incorporated in the Parliamentary Entitlements Legislation Amendment Bill 2014 introduced into the Parliament in October 2014, and which was still before the Parliament as of April 2015. Other announced measures are being implemented through administrative processes, or have been implemented via amended Tribunal Determinations.

17. In addition, the 2015–16 Budget delivered on 12 May 2015 included further proposals for amendment to existing travel provisions, as provided under current legislation and Remuneration Tribunal Determinations, together with simplification of budget arrangements for supporting Parliamentarians’ electorate office requirements and the implementation of a Parliamentarians’ injury compensation scheme.

Audit objectives and scope

18. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of Finance’s administration of travel entitlements provided to Parliamentarians.

19. The audit examined the administration of travel entitlements generally, with a focus on two entitlements (travelling allowance and charter transport) over the period January 2012 to December 2013. It assessed the effectiveness of the administrative arrangements and controls that are in place, including Parliamentarians’ certification of the use of entitlements and arrangements to respond to any issues that arise in respect to entitlements use. More broadly, having regard for the various reviews and reforms announced or undertaken since the 2009–10 audit report was completed, the audit also examined whether the current entitlements framework, and its administration, assists Parliamentarians to adhere to any conditions and limitations on the travel entitlements provided to them.

20. The audit scope did not include travel entitlements provided to persons employed under the Members of Parliament (Staff) Act 1984 (MoP(S) Act). It also did not examine the administration of travel entitlements provided through other agencies, such as transport entitlements provided to Ministers by their home department or the special purpose aircraft flights administered by the Department of Defence.

Audit criteria

21. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the entitlements framework is clearly articulated and supports the transparent, accountable and effective provision of travel entitlements to Parliamentarians;

- travelling allowance payments made by Finance are within the entitlements of the relevant Parliamentarian; and

- charter travel payments made by Finance are within the entitlements of the relevant Parliamentarian, and are utilised in a manner that provides value for money.

Overall conclusion

22. The conduct of an independent ‘root and branch’ review of Parliamentarians’ entitlements following the completion of ANAO’s 2009–10 audit report gave some cause for optimism that improvements would be made to the entitlements framework and its administration. However, fundamental weaknesses in the framework remain. Principally, this is because independent recommendations for substantive legislative and administrative reform developed to simplify current arrangements and safeguard the interests of the Commonwealth and Parliamentarians, or alternative measures to address recognised fundamental issues with the framework, have not been actioned. As a result, the framework under which Parliamentarians’ non-remuneration entitlements are provided has continued to be complex and opaque, with travel entitlements recognised as representing one of the areas most affected by those factors.

23. It is unsurprising, therefore, that this audit again highlighted the resulting challenges for: Parliamentarians in effectively accessing entitlements; the Department of Finance (Finance) in terms of efficient and effective administration; and all parties in promoting transparency and accountability for the public expenditure involved. In particular, there continue to be adverse implications for the ability of Parliamentarians and their offices to understand and comply with the intended purposes of, and any conditions or limitations on, individual entitlements, with associated implications for the capacity to provide reliable certifications in relation to that entitlements use. The certification processes also do not encourage reasonable disclosure of the purposes of travel for which public moneys have been applied, noting that:

- in providing transaction-based certifications (which are only required for certain travel entitlements), Parliamentarians rarely chose to provide information that gave any additional insight into the particular purpose of individual instances of travel beyond that broadly indicated by the generic travelling allowance or charter transport entitlement being accessed. In the case of travelling allowance, for example, this is notwithstanding that the relevant form provides the capacity to provide additional details. Under the existing framework, the provision of such information is not a requirement; and

- the periodic global certification of all entitlement usage in a given six month period remains a voluntary process with variable levels of adherence by Parliamentarians, and in respect to which some Parliamentarians take a more cautious approach in relation to the nature of certification provided.

24. It is recognised that Parliamentarians have very demanding roles, of which travel is an essential part. This includes for routine purposes which are fully recognised as part of the entitlements framework, including attending Parliamentary proceedings; servicing the needs of the constituents the Parliamentarian represents; and undertaking other aspects of the work of a Senator or Member and, as relevant, office-holder. In that context, however, it has often been the case that it is only when information regarding the specific nature of the activities that particular entitlements usage was associated with is highlighted through other sources, including the media, that closer consideration is able to be applied as to whether undertaking those activities represented an eligible or appropriate use of entitlements. In that respect, although it does not accurately reflect the actual processes that are employed, there have been no changes made to the published administrative protocol for handling allegations of entitlements misuse by a Senator or Member in the nearly 17 years since that document was introduced. Nor has there been any improvement to address its evident shortcomings as an effective accountability mechanism, other than the recent partial implementation of a CROPE report administrative recommendation directed at addressing the inability to compel Parliamentarians to respond to inquiries made under the Protocol.4

25. For its part, Finance has provided advice and assistance to successive governments, with the aim of seeking to address various shortcomings in the entitlements framework. In response to the findings and recommendations of earlier ANAO audits and other reviews, the department has also made some important improvements to its administration of Parliamentarians’ travel entitlements. This has included enhanced pre-payment monitoring to identify claims that may have been made under an entitlement not available to the relevant Senator or Member or which would exceed applicable caps or limits, and implementation of a more comprehensive and risk-based post-payment checking and audit function. However, the scope for further improvements in the department’s entitlements administration remains constrained by the deficiencies in the framework itself.

26. In this context, it is relevant to note that a recent judgment issued by the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory included consideration of the application, and associated ambiguity, of the term ‘parliamentary business’ as currently identified in relevant heads of authority for the use of entitlements at public expense.5 The specific circumstances of that particular case are appropriately a matter for the courts. More broadly, however, the Court’s published consideration and conclusions highlighted that, under the existing framework, it is very difficult for the standards of accountability supported by objective and independent assurance generally expected to apply to the expenditure of public money to be effectively applied in relation to entitlements expenditure by Parliamentarians.

27. To support and reinforce actions already taken by Finance to improve its administration of Parliamentarians’ entitlements under current arrangements, ANAO has made two recommendations. The first relates to further improving transparency and accountability in reporting on the periodic certification by Parliamentarians of entitlements use. The second seeks to further improve the department’s approach to post-payment audit and checking of the use of travel entitlements.

28. As noted at paragraphs 4 to 7, previous ANAO audit reports highlighted the need for fundamental review of the entitlements framework and made associated recommendations. In that respect, recommendations of the April 2010 report of the independent ‘root and branch’ review (and subsequently supported by the Remuneration Tribunal), setting out a reform pathway for establishing a consistent, simple and transparent framework for providing Parliamentarians with the ‘tools of trade’ required to undertake their respective duties, remain relevant. No government decisions not to implement those recommendations had been recorded in the five years since the CROPE report was finalised. Nor had any alternative proposals been adopted to address the fundamental issues associated with the current framework. In that context, ANAO has not made any further recommendations concerning the entitlements framework.

29. The 2015–16 Budget delivered on 12 May 2015 set out proposals for simplifying arrangements under which Parliamentarians will be able to access funding to operate their respective electorate offices. The Government also proposed to pursue amendment to certain aspects of the existing travel entitlements, including through the introduction of an additional generic eligibility test allowing travel to also be undertaken for ‘business as an elected representative’. The Budget proposals in themselves do not address the need for the more extensive reform that has been highlighted by earlier independent reviews. In the absence of such reform, Parliamentarians’ entitlements will continue to be provided through a patchwork framework that has been the subject of only limited enhancements. As a consequence, there will continue to be:

- a lack of transparency as to the particular purposes for which entitlements have been accessed, which can be expected to give rise to continued concerns that the framework is providing greater latitude to Parliamentarians in their use of public money than might be expected in the public interest; and

- a heightened risk of Parliamentarians being criticised for the judgements they individually make in relation to whether a particular use of publically funded resources was within the terms of the relevant entitlement and represented an efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of public resources.

30. It is well within the capacity of government and the Parliament to agree on a clearer and more contemporary framework for administering parliamentary travel and other entitlements, and further consideration of such an approach is encouraged.

Key findings by chapter

Entitlements Framework (Chapter 2)

31. Successive ANAO audit reports have highlighted the inadequacy of the existing legislative and administrative framework for the provision of services, facilities and other allowances (known as ‘entitlements’) to Parliamentarians in order to enable them to undertake their respective duties. In particular, the current framework does not provide appropriate certainty in terms of the nature and extent of each entitlement and, therefore, whether it has been accessed on each occasion for eligible purposes and within other applicable limits or specifications. Both the ANAO’s 2001–02 and 2009–10 audit reports concluded that fundamental reform of the overall framework was needed, so as to provide appropriate clarity about the purposes for which entitlements are provided; any limits on their use; and to allow for a stronger accountability regime over expenditure.

32. In response to the 2009–10 audit report, the then Government commissioned a ‘root and branch’ review of the entitlements framework to be undertaken by an independent committee, the Committee for the Review of Parliamentary Entitlements (CROPE—also known as the Belcher Review). The terms of reference for that review comprised a mix of high level strategic issues and detailed specific references.

33. The April 2010 CROPE report reached similar conclusions to those set out in earlier ANAO audit reports in regard to the inadequacy of the existing framework supporting the provision of Parliamentarians’ entitlements. The report made a number of recommendations directed at separating determination of the personal remuneration to be paid to Parliamentarians from the expenditure that relates to providing parliamentary ‘tools of trade’ (which incorporates most expenditure currently referred to as ‘entitlements’, including travel). In relation to remuneration, the report recommended that the Remuneration Tribunal independently establish the base salary that is to be provided to Senators and Members based on a work value assessment, together with the additional salary that should be provided to Shadow Ministers.

34. The CROPE report also recommended establishing a new approach to delivering the ‘tools of trade’ stream to provide a robust foundation upon which to administer and use the entitlements covered by the scheme. Specifically, the Committee recommended that the Government enact a single piece of legislation to provide a consistent, simple and transparent framework for the provision and regulation of Parliamentarians’ tools of trade at public expense. That legislation, to be administered by the SMOS, would replace the existing plethora of legislation, determinations, other instruments, executive decisions and conventions that currently govern the entitlements available to Parliamentarians.

35. Under the proposed reforms, the Remuneration Tribunal would no longer have a role in determining non-remuneration entitlements, thereby removing the existing duality (and associated complexities) under which responsibility for determining the tools of ‘the parliamentary trade’ is shared between the Tribunal and the SMOS (through regulations made under the PE Act).6 Instead, the non-remuneration facilities, services and allowances available to Parliamentarians at public expense would be established by the SMOS through regulations made under the new single piece of legislation. Such regulations would be disallowable by the Parliament.

36. The CROPE report proposed that this new approach to delivering tools of trade would also involve clearer powers of delegation (which would be used in accordance with the objectives of the primary legislation) and subordinate legislation that groups like entitlements together, with consistent meanings and operational rules. In addition, the Committee recommended that, in determining the tools of trade to be provided under the new legislation, the SMOS receive advice from an independent advisory committee and publish both the committee’s advice and the government response.

37. The CROPE report’s conclusions and recommendations in regard to both the need for, and recommended approach to, reforming the legislative and administrative framework underpinning the provision of Parliamentarians’ remuneration and other entitlements were supported by the subsequent independent report of a January 2011 review of Finance’s administration of entitlements and the Remuneration Tribunal’s initial review of Parliamentarians’ remuneration concluded in December 2011.

38. In that regard, the Williams review commented that a concern expressed by Parliamentarians had been that both written and oral advice on entitlements from the department could lack clarity or be inconsistent. However, the report also noted the difficulties that arose in providing definitive advice in the context of an entitlements framework ‘that is based on three terms (parliamentary, electorate and official business) that are not easily defined but are used as eligibility criteria for over 50 entitlements’.

39. The Tribunal’s 2011 report recommended that government streamline the existing entitlements framework to reflect a firm delineation between remuneration (to be provided under the Remuneration Tribunal Act 1973 (Remuneration Tribunal Act)) and business expenses (to be provided under a single Act, being the PE Act or a successor), and an improved interface between the administrators of the two Acts so that the two legislative instruments operate singularly and separately with no overlap.

40. The CROPE recommendation relating to the independent determination of parliamentary base salary has been implemented, with an increased base salary being set by the Tribunal from 2012 based on the findings of a work value assessment. Some other recommendations of the CROPE report relating to amendments to certain specific entitlements provided under the existing framework have also received consideration and, in some cases, been implemented.

41. The 2015–16 Budget delivered on 12 May 2015 included proposals for further amendment to existing travel entitlements, including incorporating travel on ‘business as an elected representative’ as an additional generic eligible purpose of travel at public expense7; better aligning travel provisions with the purpose of travel, including streamlining of existing travelling allowance provisions; and providing a mechanism by which a Parliamentarian would be able to certify usage of travel services that is not within standard entitlement parameters, but which the Parliamentarian considers to provide greater value for money. Given the Remuneration Tribunal’s role in independently determining Parliamentarians’ travel entitlements, implementation of those proposals will require consultation with, and the agreement of, the Tribunal. The Budget measure also proposed the simplification of a range of existing entitlements relating to Parliamentarians’ electorate office costs through the formation of two broad entitlement budgets that are intended to provide greater efficiency and flexibility for Parliamentarians; and the introduction of a Parliamentarians’ injury compensation scheme. Both of those latter measures reflected, in full or in part, recommendations of the CROPE report and Remuneration Tribunal. In May 2015, Finance advised ANAO that implementation strategies for the proposals set out in the Budget measure were under consideration.

42. However, as at May 2015, there had been no progress in implementing the April 2010 CROPE recommendations for legislative reform to underpin the provision of non-remuneration entitlements, or adopting alternative proposals to address the fundamental issues associated with the current framework. In addition, the CROPE report’s suggestion that the scope of eligible entitlements use be clarified by government identifying, through the use of broad categories, those activities that would and would not be publicly funded has also not been implemented. The resulting ongoing challenges for maintaining transparent and accountable use of the public money involved, and for Parliamentarians in effectively accessing their entitlements, were reflected in the outcome of ANAO’s examination in this performance audit of the administration of travel entitlements.8 This situation was also reflected in advice provided by Finance to the SMOS in November 2013 being that the existing system is expensive to administer ‘… whilst at the same time failing to provide a fundamental safeguard that payments are only made in accordance with the entitlements’.

43. A further consequence of the absence of progress in implementing substantive framework reform is that the use of entitlements continues to be subject to certain ‘conventions’. These particularly relate to the use of entitlements (including travel entitlements) in the context of election campaigns. The continued application of such conventions, which have no legal standing, is problematic in terms of both:

- clearly establishing whether entitlements have been accessed only for the purposes for which they have been provided under the relevant head of authority and do not provide an inappropriate benefit of incumbency; and

- ensuring that administrative arrangements do not seek to inhibit access to entitlements in a manner that is contrary to the terms of the relevant head of authority.

Confirming the Eligibility of Use of Entitlements (Chapter 3)

44. The certification by Parliamentarians that they have appropriately accessed goods, services and allowances provided at public expense is a key element of the entitlements accountability framework. Reliance is placed upon those certifications as the primary mechanism for ensuring that all entitlements are only accessed in accordance with the terms set out in the relevant head of authority (and, therefore, within entitlement). This is particularly the case in relation to the purpose for which an entitlement has been accessed. Certifications are sought on a periodic basis and, for certain entitlements, on a transactional basis.

45. In respect to travel entitlements, Parliamentarians are required to certify the eligibility and compliance of each transaction under their respective travelling allowance and charter transport entitlements. This is done through the Senator or Member signing a travel declaration (for travelling allowance claims) or charter certification (with separate forms applying to different charter transport entitlements). Finance also undertakes a number of pre-payment checks which go to aspects of eligibility under the relevant entitlement that are capable of objective confirmation. The department’s administration of those aspects of Parliamentarian’s travel entitlements has improved considerably over practices observed in previous audit reports, and was reasonably effective having regard for the inherent risk of error arising from the manual processing involved.

46. Various aspects of the transactional certification process undertaken in the period examined by this audit indicated weaknesses in the robustness and reliability of that process. ANAO noted instances in which charter certification forms provided by Parliamentarians did not accurately identify all travel taken using the chartered transport and/or the details set out on the form did not match those identified on the relevant charter company invoice. In some cases, in accordance with documented procedures, Finance had sought clarification or an amended certification form from the relevant Parliamentarian’s office. However, in other cases, the department did not seek to clarify the matter or obtain an accurate certification of the relevant charter transport use. In that context, there would be benefit in Finance applying an increased focus as to whether the certifications received from Parliamentarians are performing their intended assurance role. This includes applying appropriate scrutiny to associated invoices and other documentation in order to identify potential anomalies requiring clarification.

47. In relation to travelling allowance, there were a number of circumstances in which, as part of the pre-payment checks undertaken, Finance was able to identify that a Parliamentarian had submitted a travel declaration that incorrectly certified that he or she had fulfilled all the requirements of the nominated Remuneration Tribunal Determination clause (entitlement). In other cases, the department required further information before it could process a claim under the relevant clause. It was not uncommon for these processes to result in claims being amended or replaced such that the claim was then made under a different clause, including in some cases to reflect a different purpose of travel. On occasion, the claim was withdrawn. This situation serves to highlight the complex nature of the existing entitlements framework and both the resulting difficulties Senators and Members (and their offices) experience at times in providing reliably completed travel declarations and associated certifications; and increased exposure to the potential for ineligible claims to be submitted.

48. However, clarifying exchanges of that nature do not occur where there is no readily identifiable anomaly between: the relevant Parliamentarian’s electorate and other offices held; the entitlement being certified to; the location of the overnight stay or travel undertaken (as relevant); and/or the information set out on the travel declaration or charter certification form. In those circumstances, reliance is placed upon the certification provided by the Parliamentarian by way of signing the relevant form as to the compliance of the claim with the entitlement being accessed, including that the travel was for eligible purposes.

49. In providing such certifications, and notwithstanding that the form provides the capacity for greater details to be submitted, Parliamentarians rarely provided information that gave any additional insight into the purpose of individual instances of travel beyond that indicated by the generic travelling allowance entitlement being accessed, or the type of charter certification form provided. For example, in most cases examined, the field on the travel declaration form for describing the meeting attended or other reason for the claim was either completed with generic references9 that simply mirrored the broad eligible purpose of travel set out in the Determination for the travelling allowance entitlement being accessed, or was left blank.

50. In relation to charter transport entitlements, there were instances in the transactions examined in which the purpose of travel certified to in relation to a particular use of charter transport was potentially inconsistent with the purpose of travel that had been separately certified to by the relevant Parliamentarian when claiming travelling allowance for overnight stays associated with the same journey. There were also instances in which the travel details identified on a travel declaration submitted for a particular journey were inconsistent with those identified on a charter certification form separately submitted in respect to the same journey.

51. Significant elements of the travel and other entitlements available to Parliamentarians are not subject to a transaction-based certification process. In relation to travel entitlements, this includes, for example, all travel on domestic scheduled aircraft and other services where no associated travelling allowance is being claimed, and car costs (such as COMCAR and self-drive hire vehicles not engaged under a charter transport entitlement). Travel declarations are not required to be submitted in relation to such travel. Rather, certification as to the compliant use of those entitlements is sought through a request made to current and former Parliamentarians to provide periodic general certifications in relation to their use of all entitlements. As from November 2011, certification was changed from the previous monthly process to align with the publication on the Finance website of six monthly entitlements expenditure reports for each relevant current and former Parliamentarian.10 The certification requested is general in its terms and includes no specific reference to particular entitlements or instances of entitlements use. Rather, it involves each individual being asked to certify (for entitlements administered by Finance) that his or her use of each entitlement during the specified period was in accordance with the provisions legislated for each respective entitlement.

52. This process involves an administrative request, with Parliamentarians being under no obligation to provide the certification. Response rates under the previous monthly certification process had been an ongoing issue, with some Parliamentarians declining to provide the requested certification. In this context, also from November 2011, Finance has published details of whether each relevant individual has provided the requested certification in respect to a given six month period.11 That measure partially implemented one of the administrative recommendations of the April 2010 CROPE report directed at enhancing accountability and providing an incentive for current and former Parliamentarians to provide the requested periodic certifications.

53. Consistent with the outcomes achieved under previous approaches, it continues to be the case that in no reporting period to date has there been full compliance with the provision of relevant six monthly certifications of entitlements use, including by sitting Parliamentarians. Over the seven certification periods to 30 June 2014, Finance has reported on the provision or otherwise of certifications of the use of entitlements as a sitting Senator or Member in respect to 320 individuals. Of those, as at 11 May 2015 around two-thirds (210, 66 per cent) were disclosed as having provided the requested certification on all relevant occasions. The remaining third were disclosed as having failed to provide a certification in respect of one or more relevant periods. As at May 2015, three individuals (two current Parliamentarians and one former Member who left the Parliament at the September 2013 election) had not provided a certification in relation to their use of entitlements as a sitting Senator or Member in respect to any of the periods for which six monthly certification details had been published since November 2011. It also continues to be the case that some Parliamentarians qualify the certification provided.

54. Given the entitlements, including travel, provided to Parliamentarians are funded through the use of public money, it is not unreasonable to expect Senators and Members to certify as to their compliance in the use of those funds with the eligibility and other requirements set out in the relevant head of authority, or to explicitly state the basis on which he or she does not feel able to provide such a certification. Similarly, any qualification to the certification should be rare and, where it does occur, transparent to the broader community. In that context, the efficacy of the existing certification disclosure process as a transparent accountability mechanism would be enhanced by the department also disclosing:

- the terms of the certification each individual has chosen to provide; and

- in respect to each individual listed as not having provided a relevant certification, any reason that may have been given for not signing the certification or, as relevant, that no reason has been provided; and/or that no response to the certification request had been received from the relevant individual.

Key Accountability Mechanisms (Chapter 4)

55. ANAO’s 2009–10 audit report observed that shortcomings in the entitlements framework had not assisted Finance in its role, and that the department had also adopted a relatively gentle approach to entitlements administration. In that context, in July 2009, the then Government agreed to the establishment of an enhanced audit and checking function within Finance, at a cost of $3.5 million over four years. That function consists of a rolling internal audit review program conducted through Finance’s internal audit provider; and a post-payment checking program undertaken within the areas responsible for entitlements management and processing. In a significant improvement over the department’s previous approach to post-payment oversight of entitlements, both aspects have been based upon an evolving risk assessment framework. The function is also overseen by an internal governance committee.

56. The various travel entitlements accessed by a Parliamentarian in undertaking a particular trip are generally processed separately and at different times. This is due to both the manner in which the relevant documentation is provided to the department by Parliamentarians and travel service providers, and Finance’s internal processes.12 As a consequence of this ‘silo’ approach, there is a risk of the department’s oversight of entitlements use not identifying potential inconsistencies between the various purpose-based travel entitlements accessed by a Parliamentarian in the course of a particular journey. A number of such potential inconsistencies were identified in ANAO’s examination of a sample of transactions.13 In that context, there would be merit in Finance supplementing its existing post-payment audit and checking program to incorporate data analysis and other risk-based tests that reconcile the various entitlements accessed in connection with a single journey to assist the department in identifying potential anomalies for further examination or clarification. Tests of that nature would build on the work already undertaken in relation to identifying concurrent use of mutually exclusive car transport entitlements and in relation to the risks associated with travel taken without associated travelling allowance claims.

57. As mentioned in paragraph 51, details of entitlements expenditure incurred by current and former Parliamentarians are now published in six monthly reports. That measure implemented a July 2009 decision by the then Government to expand the then existing six monthly travel expenditure reports to encompass all entitlements administered by Finance. The publication of expanded expenditure details has provided the capacity for enhanced public scrutiny of the entitlements use of individual Parliamentarians. In that respect, the April 2010 CROPE report recommended additional measures to further enhance the public disclosure of entitlements expenditure, but none of those recommendations had been implemented as at April 2015. A November 2013 departmental proposal to the SMOS that there would be merit in providing more timely, and potentially more detailed, public reporting on entitlements expenditure has also not been actioned.

58. In June 1998, the then SMOS approved a document titled Protocol followed when an Allegation is Received of Alleged Misuse of Entitlement by a Member or Senator (the Protocol). The Protocol document was tabled in the Parliament in 2000. Aspects of the department’s administration of the Protocol have improved compared to the practices observed in the 2009–10 audit report. However, it has been long recognised that the document itself would benefit from amendment to both:

- ensure its terms transparently reflect actual practice in dealing with allegations of entitlements misuse, which is not currently the case; and

- enhance its efficacy as an accountability governance document.

59. In this respect, in the period examined by ANAO as part of this current audit, a number of amendment proposals were put to successive Special Ministers of State by the department. The content and operation of the Protocol was also the subject of CROPE report recommendations. However, the Protocol document has not been amended in the nearly 17 years since it was first issued.

60. As noted, legislation amending the PE Act to implement a measure announced by the SMOS in November 2013 relating to imposing a 25 per cent penalty on adjustments to certain travel benefits (including voluntary repayments) was before the Parliament as at April 2015.14 The legislation also proposes to establish a legal right of recovery where a Parliamentarian has been paid a benefit in excess of the relevant entitlement. However, the amending Bill does not seek to provide a legislative head of authority for handling allegations of entitlements misuse. Nor does it alter the reliance under the existing framework on key eligibility terms that are open to interpretation. Accordingly, under existing arrangements, it will continue to be the case that Finance will be largely reliant upon current and former Parliamentarians self-assessing whether it would be appropriate to make a voluntary repayment where there is an allegation of misuse of entitlements.

61. A further measure announced in November 2013 (partially implementing a CROPE report recommendation) was that the SMOS may table in the Parliament the name of any Senator or Member who fails to substantially comply within a reasonable time with a request for further information as part of a departmental inquiry. The published Protocol has similarly not been amended to reflect that process. Nor had administrative procedures for its implementation been agreed by the SMOS as at 30 April 2015.

62. As noted at paragraph 15, the SMOS also announced that, to improve the system’s integrity, from 1 January 2014 the Government would:

- strengthen the declaration a Parliamentarian is required to make when submitting a travel claim, which would involve declaring that the relevant travel had been undertaken ‘in my capacity as an elected representative’; and

- require Parliamentarians that made an adjustment to any travel claims made after 1 January 2014 to pay a loading of 25 per cent, in addition to the full amount of the adjustment, subject to specified caveats.

63. Legal advice subsequently provided to Finance highlighted concerns in relation to the terms of the revised declaration. These included that it did not reflect the eligibility terms used in the relevant heads of authority; introduced a term (elected representative) that is not a relevant test for determining eligibility under the expressed terms of any of the travel entitlements; and that it may be counterproductive to attempts to tighten travel entitlement provisions. Amendments to the declaration proposed in the legal advice were not implemented, with the announced declaration being added in March 2014 to the travel declaration and private vehicle allowance claim forms required to be submitted by Parliamentarians.15

64. Further, as noted, legislation to authorise the imposition of a penalty loading on certain repayments was still before the Parliament as at April 2015. Consequently, for at least 12 months, Parliamentarians have been required to make a declaration when submitting travelling allowance and private vehicle allowance claims that:

- is not a relevant test of eligibility for accessing the entitlement16; and

- includes an acknowledgement of the potential imposition of a financial loading on any subsequent repayments that had no legal effect and for which there was no legal authority.17

65. In light of the already complex entitlements framework, that situation is not helpful in terms of assisting Parliamentarians in accessing their respective entitlements in an effective manner. It also serves to highlight the difficulties that arise in attempting to implement specific measures directed at strengthening the integrity of entitlements administration in the context of an underlying entitlements framework that is in recognised need of fundamental reform.

66. As noted18, the 2015–16 Budget delivered on 12 May 2015 included proposals for amendment to certain travel entitlements. This included that the Remuneration Tribunal would be asked to consider:

- extending Parliamentarians’ domestic travel entitlements to provide for travel on ‘business as an elected representative’, in addition to the existing entitlements to travel on ‘parliamentary’, ‘electorate’ and ‘official’ business;

- aligning the myriad of travelling allowance provisions with domestic travel provisions, including travel on ‘business as an elected representative’; and

- providing a mechanism for Parliamentarians to undertake domestic travel which is not within standard entitlement parameters, but which the Parliamentarian considers to deliver greater value for money. It is proposed that this mechanism would rely upon a certification provided by the Parliamentarian.

67. The Budget measure proposed that the realignment of travel provisions with the purpose of travel will provide greater clarity in assessing travel entitlements. In that respect, the application of key eligibility terms for accessing entitlements has proven problematic over a considerable period of time in terms of achieving appropriate transparency and accountability in entitlements use. In that context, those recognised challenges would need to be addressed in implementing the proposed introduction of an additional term for describing eligible purposes for which travel may be taken at public expense.

Summary of entity responses

68. The proposed report was provided to Finance and the Special Minister of State. An extract of the proposed report was provided to the Remuneration Tribunal. Formal comments on the proposed report were provided by Finance and the Remuneration Tribunal, and are included in full at Appendix 1. A summary of Finance’s comments is also included below.

Department of Finance’s response

The Department of Finance notes and welcomes the ANAO’s findings that the department has made ongoing and important improvements to its administration of parliamentarians’ travel entitlements. These improvements have been designed to both assist our clients in accessing their entitlements and provide transparency for government in the management of parliamentary entitlements.

Whilst the department necessarily relies on the certification of Senators and Members in accessing their travel entitlements ANAO has noted the department’s audit and checking process provides improved assurance in regard to the public outlays to these entitlements.

Finance notes that there are several case studies provided in the report where inconsistency of process is highlighted. Given the length of time since these transactions were undertaken (pre 2014), Finance has undertaken a sample review to ensure that such inconsistencies have been removed from current transaction processes.

The department remains committed to continually improving our administrative processes and procedures within the Parliamentary Entitlements Framework.

Recommendations

Set out below are ANAO’s recommendations directed at improving administration of entitlements within the existing framework, and Finance’s abbreviated responses. More detailed responses are shown in the body of the report immediately after each recommendation. Although it is recognised as being deficient in many respects, ANAO has not made any recommendations in this audit report concerning the entitlements framework. This is because recommendations for substantive reform that were set out in the April 2010 report of an independent committee commissioned to undertake a ‘root and branch’ review of the entitlements framework in response to ANAO’s 2009–10 audit report (and subsequently supported by a 2011 report of the Remuneration Tribunal) have yet to be actioned, but remain relevant. Nor have any alternative proposals been adopted to address the fundamental issues associated with the current framework.

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 3.146 |

To enhance the efficacy of the certification disclosure process as a transparent accountability mechanism, ANAO recommends that the Department of Finance improve its procedures for disclosing details of six monthly entitlements use certifications provided by current and former Parliamentarians such that:

Department of Finance response: Agreed in principle. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.40 |

To assist it to better understand the way in which Parliamentarians use their travel entitlements, as well as to identify inconsistencies or anomalies that might merit further examination or clarification, ANAO recommends that the Department of Finance supplement its existing post-payment audit and checking function processes to include risk-based processes for reconciling the various entitlements accessed by Parliamentarians in connection with undertaking a single journey. Department of Finance response: Agreed in principle. |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the Parliamentary entitlements framework and its recent history, and describes the audit approach and scope.

Background

1.1 The Commonwealth Parliament comprises the Senate, which has 76 members (12 for each State and two for each of the Territories), and the House of Representatives, which has 150 members.19 To assist them in effectively carrying out their duties, Parliamentarians are provided with a range of support services, generally referred to as ‘entitlements’. This includes office accommodation and facilities, staff support, travel and various other allowances to assist Parliamentarians service and inform their constituents.

1.2 While responsibility for the administration and delivery of Parliamentarians’ entitlements is spread across a range of Commonwealth agencies, the Department of Finance (Finance) has by far the most significant role. This is particularly the case in relation to the administration of non-remuneration entitlements, including travel.20 The provision of Parliamentarians’ entitlements is administered by Finance as part of its Outcome 3. The department’s 2014–15 Portfolio Budget Statements reported estimated actual expenses of some $523 million for that outcome and described the related programme objective as follows:

This programme contributes to the outcome through providing the entitlements—and advice on these entitlements—of Ministers, Office-holders, Senators, Members and certain former Parliamentarians and their respective staff (employed under the Members of Parliament (Staff) Act 1984 (MoP(S)Act)). Under this programme support services provided by Finance include:

- electorate and ministerial support costs; car-with-driver and associated ground transport services;

- luggage service for guests of the Australian Government; and

- the Political Exchange Programme.

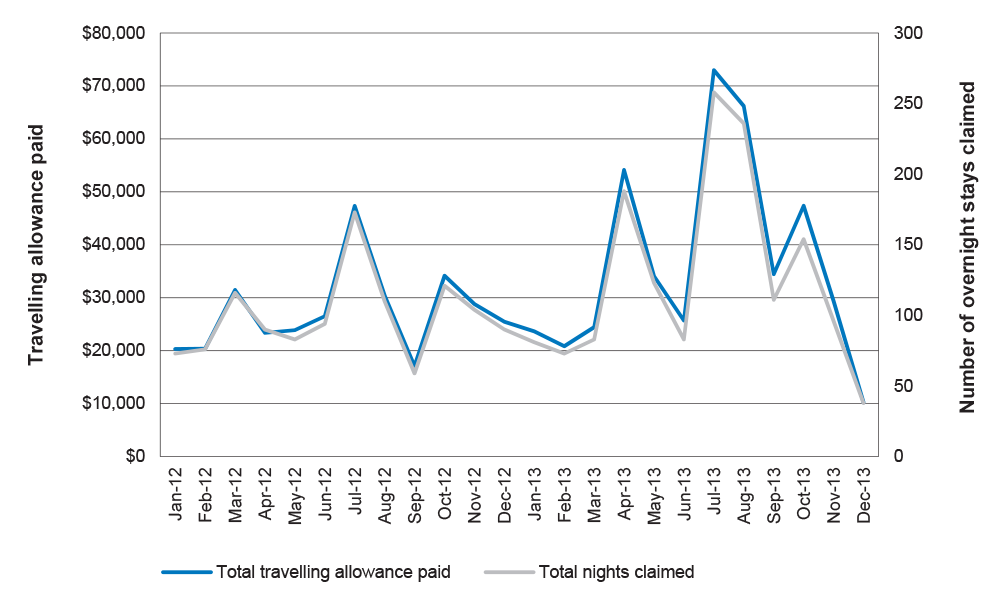

1.3 In aggregate, the various travel entitlements comprise a significant proportion of the cost of all entitlements provided to Parliamentarians. Specifically, excluding staff related costs, the six monthly expenditure reports published by Finance reported payments totalling $209.8 million as being made between January 2012 and December 2013 in relation to entitlements costs incurred by sitting Parliamentarians. Of that, nearly one third ($64.5 million or 30.7 per cent) related to costs associated with travel for Parliamentarians.21 This included travelling allowance payments over that period totalling $11.53 million and charter transport costs totalling $2.97 million.

Previous ANAO audits

1.4 The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has previously examined some or all aspects of the administration of Parliamentarians’ entitlements on five occasions. This has included conducting three performance audits since 200022, comprising:

- Audit Report No.5 2001-02, Parliamentarians’ Entitlements 1999-2000, tabled in August 2001 (referred to in this audit report as the 2001–02 audit report);

- Audit Report No.15 2003–04, Administration of Staff employed under the Members of Parliament (Staff) Act 1984, tabled in December 2003 (referred to in this audit report as the 2003–04 audit report); and

- Audit Report No.3 2009–10, Administration of Parliamentarians’ Entitlements by the Department of Finance and Deregulation, tabled in September 2009 (referred to in this audit report as the 2009–10 audit report).

1.5 The most recent of those audit reports focussed primarily on the use of the printing entitlement, but also examined the overarching entitlements framework. The audit found that the framework remained little changed from that which had applied at the time of the 2001–02 audit, some eight years earlier.

1.6 A common theme arising from the findings and recommendations of the previous ANAO audits was that the existing entitlements framework is difficult to understand and manage for both Parliamentarians and Finance. This situation arises as a result of the:

- complex (and often overlapping and ambiguous) array of legislation, determinations, rules, guidelines and conventions under which various entitlements are provided; and

- absence of an articulation or shared understanding of the scope of the key terms that largely govern whether a particular transaction will be considered to be within entitlement (such as ‘parliamentary business’, ‘electorate business’ and, for office-holders, ‘official business’).

1.7 The 2009–10 audit report noted that a positive outcome of that audit was that the then Special Minister of State (SMOS) had informed ANAO that the then Government agreed that immediate attention was warranted in clarifying the entitlements framework and providing greater transparency. In addition to specified changes that were to be made to the entitlements relating to printing, communications, newspapers and periodicals and office requisites and stationery, the then Government had also agreed to the conduct of a ‘root and branch’ review of the entitlements framework.

1.8 In that context, as was the case with previous audits, the 2009–10 audit report made a range of recommendations relating to improving the transparency and accountability of entitlements administration. This included recommending that, in progressing the government decision to undertake a review of the entitlements framework, Finance examine options that would:

- provide a principles-based legislative basis that authorises the provision of specified entitlements for defined purposes and in accordance with eligibility criteria; and

- enable accountability processes (such as usage certifications by Parliamentarians) to be mandated.

1.9 In agreeing with that recommendation, Finance advised that: ‘These options have been included in the terms of reference for the review of the entitlements framework’.

Entitlements reviews since 2009–10 audit report

Review of Parliamentary Entitlements

1.10 The ‘root and branch’ review was publically announced by the then SMOS on 8 September 2009, coinciding with the tabling of the 2009–10 audit report. The Committee for the Review of Parliamentary Entitlements (CROPE—also known as the Belcher Review) comprised: Ms Barbara Belcher AM (Chair), former First Assistant Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; Mr John Conde AO, President of the Remuneration Tribunal; Ms Jan Mason, then Deputy Secretary of the Department of Finance; and Professor Allan Fels AO, former Australian Competition and Consumer Commissioner and then Dean of the Australia and New Zealand School of Government. The review’s terms of reference are set out in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Terms of Reference: Review of Parliamentary Entitlements

|

Provide advice and recommendations to Government addressing issues such as:

In formulating advice and recommendations, the review should have regard to:

|

Source: Review of Parliamentary Entitlements, Committee Report, April 2010, p. 22.

1.11 The April 2010 CROPE report noted that the Committee’s work had represented the first comprehensive review of federal parliamentary entitlements in over 35 years, with the terms of reference that guided its work comprising a mix of high level strategic issues and detailed specific references. A public call for submissions to the review was made on 3 October 2009, and the Committee chair also wrote to all then current Parliamentarians, affected former Parliamentarians, former Prime Ministers, former Governors-General, state jurisdictions and selected academics and Commonwealth agency heads inviting their views. Public hearings were not held, but the chair and other members of the Committee spoke to a number of those who had made submissions and other interested parties. The Committee received 39 written submissions, of which 29 were subsequently published on the Finance website. During the course of its deliberations, the Committee also examined how selected similar jurisdictions regulate parliamentary entitlements. The Committee’s report was provided to Government on 9 April 2010.

Review of Finance’s administration of entitlements

1.12 In 2010, Finance commissioned a review of its administration of Parliamentarians’ entitlements. That review’s terms of reference stated that:

The Department has sought the assistance of an independent reviewer with senior level experience in the Australian Public Service to examine the way Finance administers the parliamentary entitlements framework to see if there are improvements that could be made to the way it does business and the way it interacts with parliamentary clients…Given that the parliamentary entitlements framework has recently been reviewed by an independent committee (Chaired by Ms Barbara Belcher AM) and its recommendations are yet to be considered by the Government, this review will focus on options to improve the administration of the parliamentary entitlements framework, rather than examining the framework itself.

1.13 The review was undertaken by Ms Helen Williams AO, former Secretary of the Department of Human Services (referred to as the Williams Review). The report provided to Finance in January 201123 made eight multi-faceted recommendations in relation to:

- possible alternative service delivery models, including the transfer of responsibilities in relation to certain entitlements between Finance and other agencies;

- the provision to Parliamentarians of written guidance on entitlements;

- processes for communication and provision of advice to Parliamentarians and their staff;

- improving access to entitlements, both to facilitate usage and provide administrative efficiencies;

- improving the monthly management reports provided to Parliamentarians, and transferring the post-payment entitlements certification process from the monthly reports to align with the six-monthly publication of entitlements expenditure reports;

- revising the procedures for processing certain types of claims in order to balance facilitation and control;

- prioritising necessary processing system upgrades; and

- other process improvements.

1.14 Finance has published an implementation plan in relation to the Williams Review recommendations. As at 28 February 2013, Finance had reported that all of the 47 elements of the eight recommendations had been completed. Finance’s implementation of those recommendations was examined by ANAO as relevant to the scope of this audit.

Measures announced by SMOS in November 2013

1.15 On 9 November 2013, the current SMOS announced a number of measures directed at strengthening the rules governing Parliamentarians’ business expenses. In announcing the measures, the SMOS stated that:

The system of funding the work costs of parliamentarians in carrying out their responsibilities must work in a way that ensures senators and members are accessible to their electors while ensuring taxpayers’ money is well spent and maintaining public confidence in the system.

For this reason, the Government will act to strengthen a range of measures governing the funding of parliamentarians’ work costs.24

1.16 The SMOS’ announcement followed a period in the latter half of 2013 that involved significant media scrutiny of the use of travel entitlements by a number of Parliamentarians. Reflecting that context, the measures announced by the Minister primarily related to travel entitlements. In particular, the SMOS announced the introduction from 1 January 2014 of:

- an amended declaration to be made by a Senator or Member when submitting travel claims;

- a 25 per cent loading to be paid where a Parliamentarian made a subsequent adjustment to travel claims25, other than where the adjustment was the result of an error made by Finance. The SMOS further announced that there would be a grace period of 28 days after making a travel claim in which Parliamentarians could make adjustments without penalty; and

- mandatory training for Parliamentarians and their offices if more than one incorrect claim is lodged within a financial year.

1.17 Implementation of the proposed 25 per cent loading on post-payment adjustments, and further associated amendments of the Parliamentary Entitlements Act 1990 (PE Act) proposed by Finance to enhance the capacity to recover payments made beyond entitlement, are incorporated in the Parliamentary Entitlements Legislation Amendment Bill 2014 that was introduced into the Parliament in October 2014. The Bill was still before the Parliament as of April 2015. Other measures are being implemented through administrative processes, or have been implemented via amended Tribunal Determinations.

1.18 The SMOS’ announcement further stated that, as part of this process, the Government had considered the recommendations of the April 2010 CROPE report ‘that were not adopted by the former Government’.26

May 2015 Budget measure

1.19 The 2015–16 Budget delivered on 12 May 2015 included further proposals for amendment to existing travel provisions, as provided under current legislation and Remuneration Tribunal Determinations. Given the Remuneration Tribunal’s responsibilities, implementation of those aspects of the proposals that relate to entitlements that are independently determined by the Tribunal will require consultation with, and the agreement of, the Tribunal. Other aspects of the proposals may require amendments to the PE Act. The relevant measure also proposed amendments to the budget arrangements relating to the operation of a number of aspects of Parliamentarians’ electorate offices, and the introduction of a Parliamentarians’ injury compensation scheme. Finance advised ANAO that implementation strategies for the proposed measures were under consideration as at May 2015.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

Audit objective

1.20 The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of Finance’s administration of travel entitlements provided to Parliamentarians.

1.21 This audit examined the administration of travel entitlements generally, with a focus on two entitlements (travelling allowance and charter transport) over the period January 2012 to December 2013. It assessed the effectiveness of the administrative arrangements and controls that are in place, including Parliamentarians’ certification of the use of entitlements and arrangements to respond to any issues that arise in respect to entitlements use. More broadly, having regard for the various reviews and reforms announced or undertaken since the 2009–10 audit report was completed, the audit also examined whether the current entitlements framework, and its administration, assists Parliamentarians to adhere to any conditions and limitations on the travel entitlements provided to them.

1.22 The audit scope did not include travel entitlements provided to persons employed under the Members of Parliament (Staff) Act 1984 (MoP(S) Act). It also did not examine the administration of travel entitlements provided through other agencies, such as transport entitlements provided to Ministers by their home department or the special purpose aircraft flights administered by the Department of Defence.

Criteria and methodology

1.23 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the entitlements framework is clearly articulated and supports the transparent, accountable and effective provision of travel entitlements to Parliamentarians;

- travelling allowance payments made by Finance are within the entitlements of the relevant Parliamentarian; and

- charter travel payments made by Finance are within the entitlements of the relevant Parliamentarian, and are utilised in a manner that provides value for money.

1.24 The methodology adopted for this audit included:

- examining documentation relating to implementation of recommendations of the 2010 CROPE report and 2011 Williams Review, and relevant measures announced by the SMOS in November 2013;

- examining Finance’s operating procedures and guidelines and other documentation in relation to the administration of travel entitlements, including through the Entitlements Management System (EMS) used to process entitlements payments, and the register used to record calls, contact and queries raised between Finance and each Parliamentarian or their offices in relation to entitlements;

- analytical review of travelling allowance and charter travel payments made in relation to Parliamentarians in the period examined;

- analysing a sample of travelling allowance and charter travel transactions for demonstrated compliance with the relevant head of authority. This included examining: the claim and supporting documentation submitted by the Parliamentarian; processing of the claim by Finance (including pre-payment checks); records of associated use of other travel entitlements; and relevant publically available information. Individual claims were selected for detailed examination on both a random basis and based on the outcome of relevant analytical review;

- examining the post-payment audit and checking function within Finance, particularly as it related to travel entitlements;

- analysis of the periodic certifications provided by Parliamentarians in relation to their use of entitlements; and

- examining documentation relating to the administration of the ‘Protocol followed when an Allegation is Received of Alleged Misuse of Entitlement by a Member or Senator’ (the Protocol).

1.25 The audit was conducted under section 18 of the Auditor-General Act 1997. The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $887 000.

Report structure

1.26 The audit findings are reported in the following chapters.

Table 1.1: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

2. Entitlements Framework |

This chapter examines the progress made in implementing the recommendations of the April 2010 report of the ‘root and branch’ review of parliamentary entitlements, with a particular focus on the recommendations relating to reform of the legislative and administrative framework underpinning the provision of non-remuneration entitlements (including travel). |

|

3. Confirming the Eligibility of Use of Travel Entitlements |

This chapter examines the processes by which assurance is obtained by Finance that travel entitlements are only accessed within the terms of the relevant heads of authority, including for eligible purposes. |

|

4. Key Accountability Mechanisms |

This chapter examines key mechanisms used to provide accountability and transparency in relation to the entitlements expenditure incurred by Parliamentarians. |

2. Entitlements Framework

This chapter examines the progress made in implementing the recommendations of the April 2010 report of the ‘root and branch’ review of parliamentary entitlements, with a particular focus on the recommendations relating to reform of the legislative and administrative framework underpinning the provision of non-remuneration entitlements (including travel).

Introduction

2.1 The entitlements of Senators and Members, their families and staff to travel at Australian Government expense, and for the receipt of related allowances, are set out in a complex series of authorising instruments. For example, there are 13 Acts identified by Finance in its Senators and Members Entitlements Handbook as bearing on the provision of entitlements to current and former Senators and Members. The major ones comprise:

- the Parliamentary Allowances Act 1952 (Parliamentary Allowances Act) and the PE Act, both administered by Finance; and

- determinations made by the Remuneration Tribunal (the Tribunal) under the Remuneration Tribunal Act 1973 (Remuneration Tribunal Act).

2.2 Implementation of the provisions of those Acts and Determinations also involves a series of subsidiary instruments, guidelines and conventions. Within that framework, all Parliamentarians are provided with a broad entitlement to unlimited domestic travel by scheduled services when travelling for parliamentary or electorate business or other specified purposes. There is also a broad entitlement to car transport when travelling on parliamentary business, subject to certain parameters. However, the specific travel-related entitlements of each serving Parliamentarian are derived from a complicated series of additional entitlements which vary depending upon:

- whether the Parliamentarian is a Senator or a Member of the House of Representatives;

- the nature of the relevant State or electoral division the Parliamentarian represents (in terms of both overall size and geographic make-up); and

- the nature of any additional Parliamentary, Executive or Opposition office held by the Parliamentarian at a given point of time.

2.3 The framework supporting the provision of a range of facilities, services and allowances to Parliamentarians in the conduct of their respective duties (commonly referred to as entitlements) has been the subject of considerable criticism and comment over a number of years. This has included through previous ANAO performance audits which have consistently recommended that the existing framework be reviewed with a view to providing a more robust and accountable footing for accessing of entitlements by Parliamentarians, and the capacity for the associated expenditure of public money to be appropriately overseen and administered.

2.4 As noted at paragraph 1.7, in response to the most recent of those previous audit reports, the then Government agreed to a ‘root and branch’ review of the entitlements framework by an independent committee. The CROPE report was provided to the then Government in April 2010, and tabled in the Parliament by the then SMOS in March 2011.

2.5 ANAO examined the progress made to date in implementing the recommendations of the April 2010 CROPE report, particularly in relation to reform of the legislative and administrative framework underpinning the provision of non-remuneration entitlements.

Recommendations of the Committee for the Review of Parliamentary Entitlements

2.6 The CROPE terms of reference asked the Committee to examine matters ranging from the development of a new simplified framework, including consideration of the legislative basis underpinning the provision of entitlements, to a range of specific individual entitlements as provided under the existing framework (see Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1). In that context, nearly a third (11) of the 39 recommendations set out in the CROPE report related to reforming the legislative and structural framework underpinning the establishment and provision of parliamentary entitlements. This included four recommendations relating to establishing parliamentary remuneration and associated consequential effects; and two recommendations for creating a legislative head of authority for the provision of benefits to former Prime Ministers and former Governors-General. The remaining five recommendations in this group set out proposals for significant legislative and administrative reform in order to establish a consistent, simple and transparent framework for funding Parliamentarians’ non-remuneration business expenses—currently known as entitlements.